A Breathable, Low-Cost, and Highly Stretchable Medical-Textile Strain Sensor for Human Motion and Plant Growth Monitoring

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

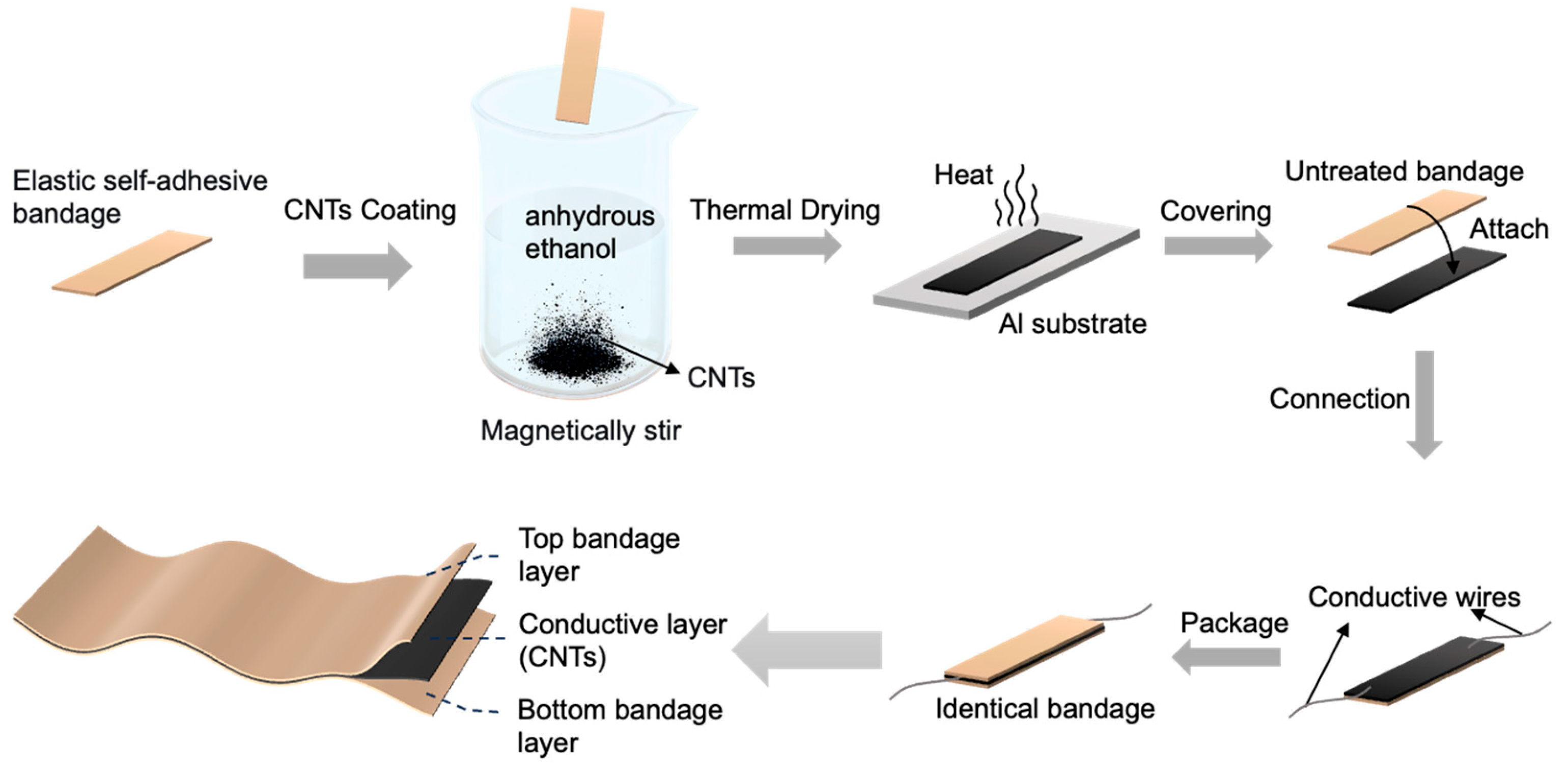

2.2. Fabrication of the Sensor

2.3. Performance Test and Characterization of Sensors

3. Results and Discussion

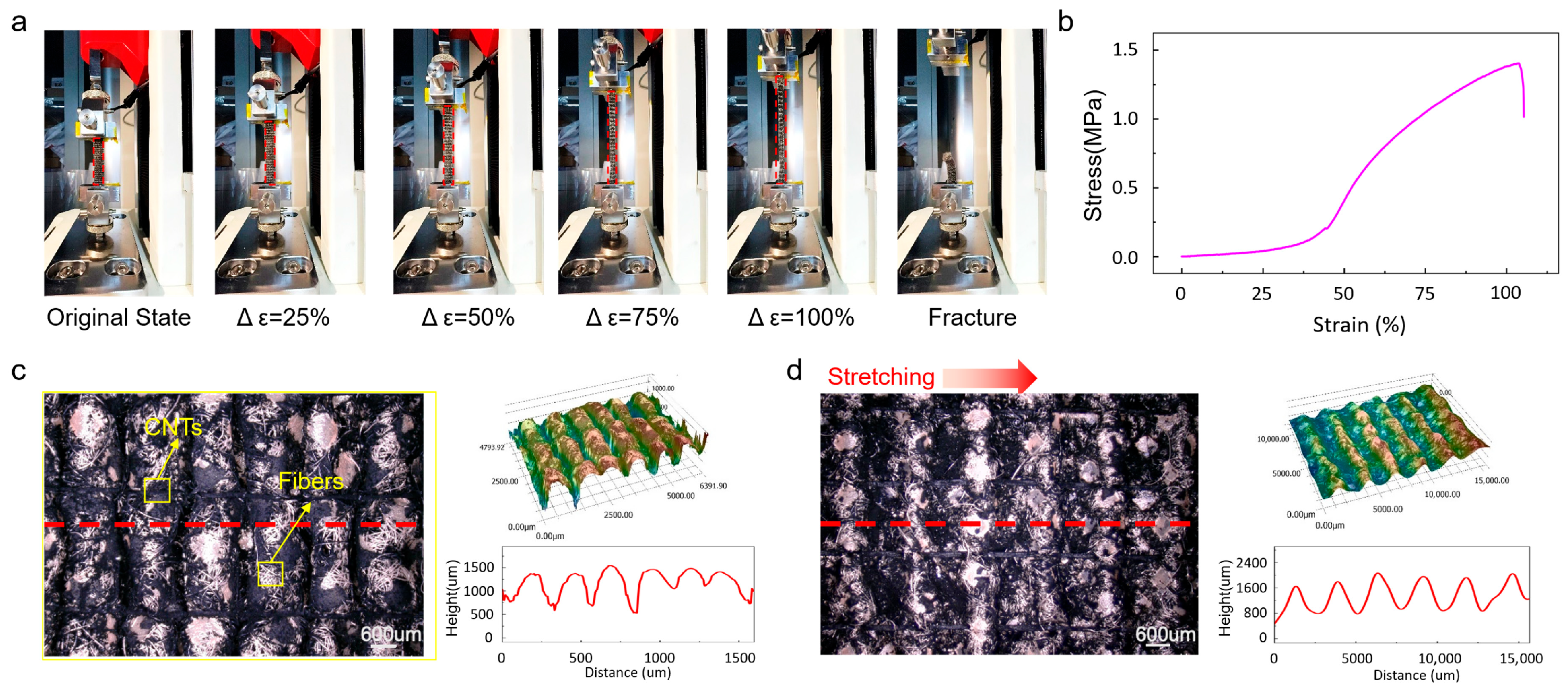

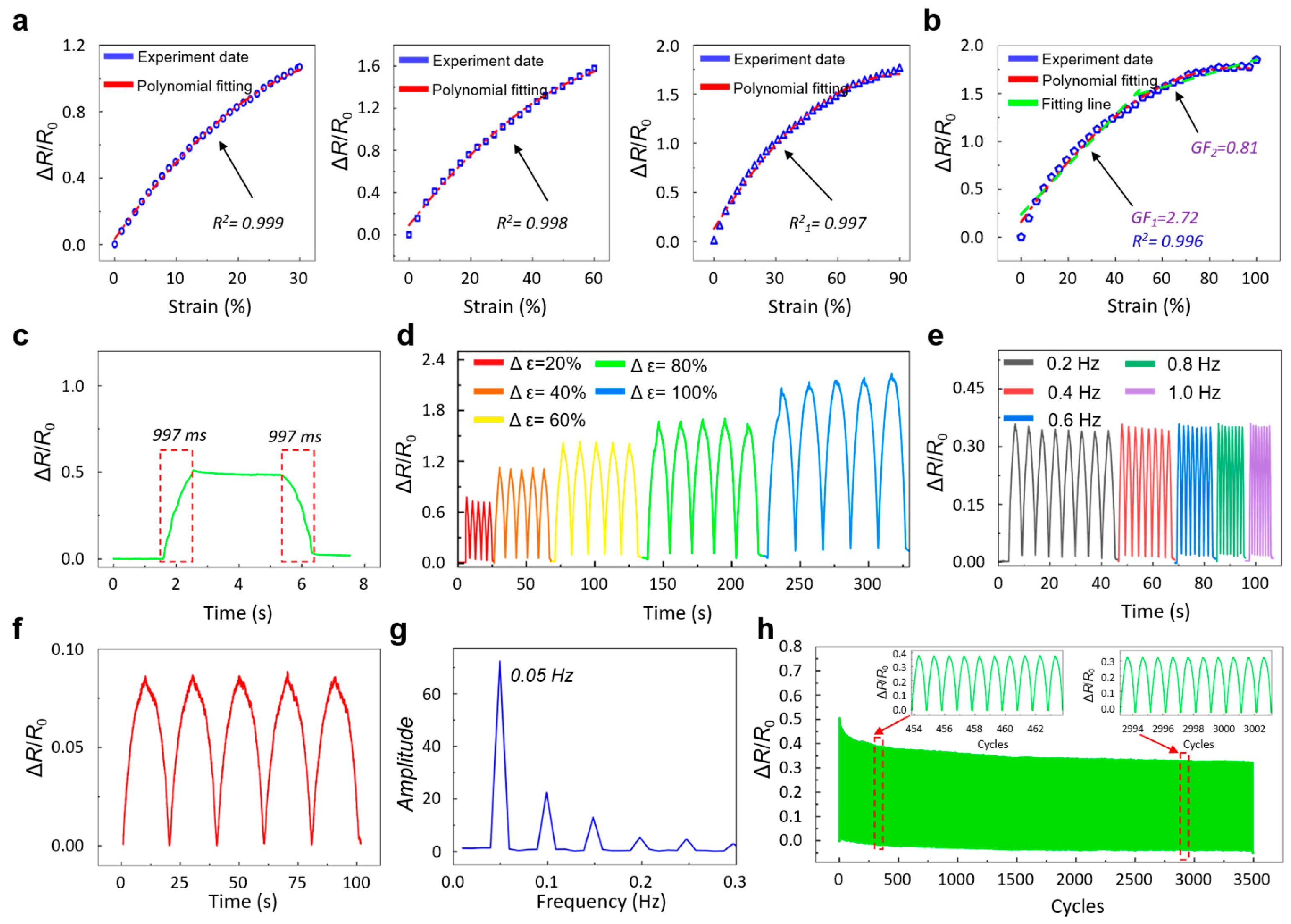

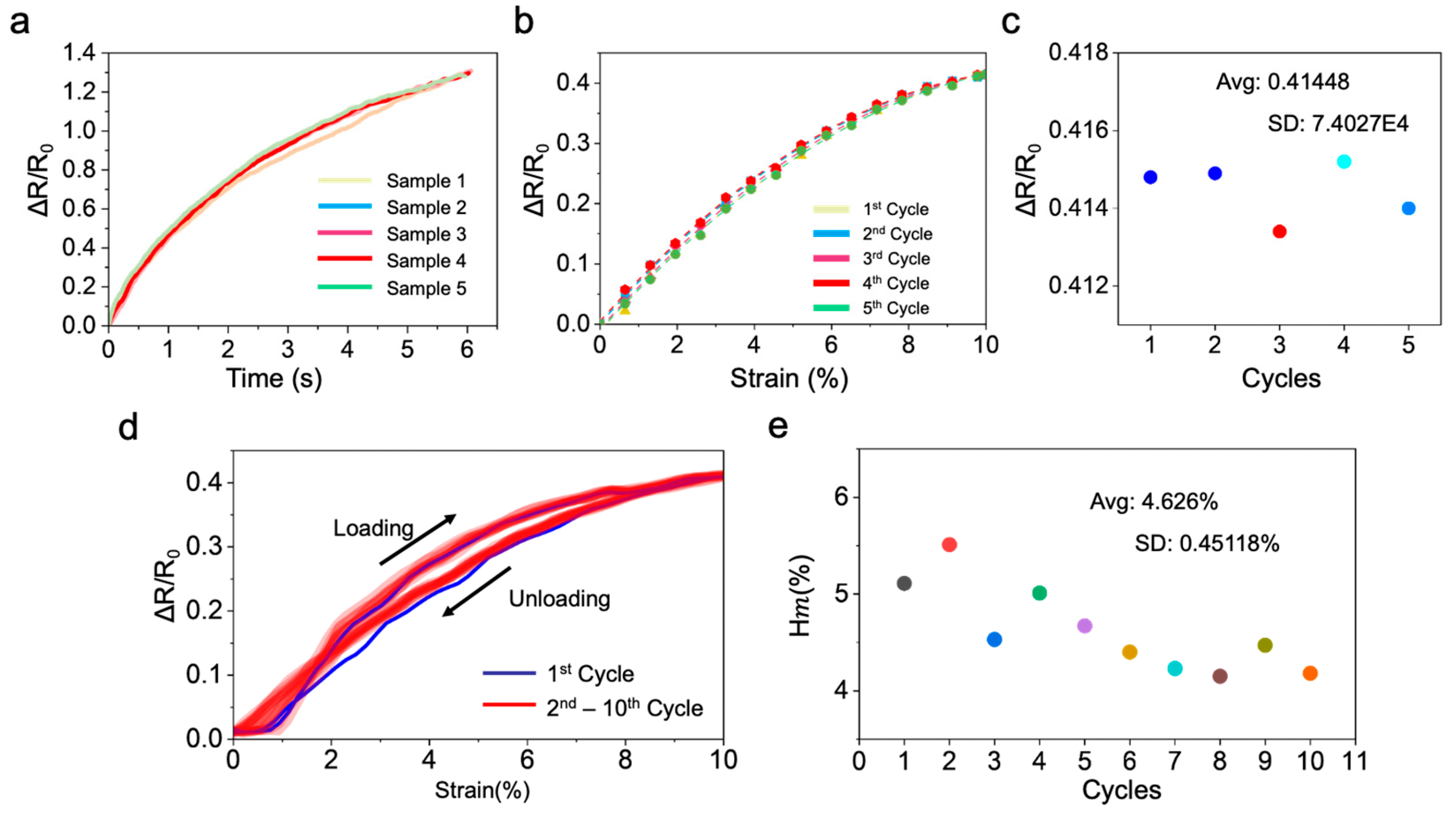

3.1. Electromechanical Response of the Sensor

3.2. Applications of the Sensor in Human Motion Monitoring

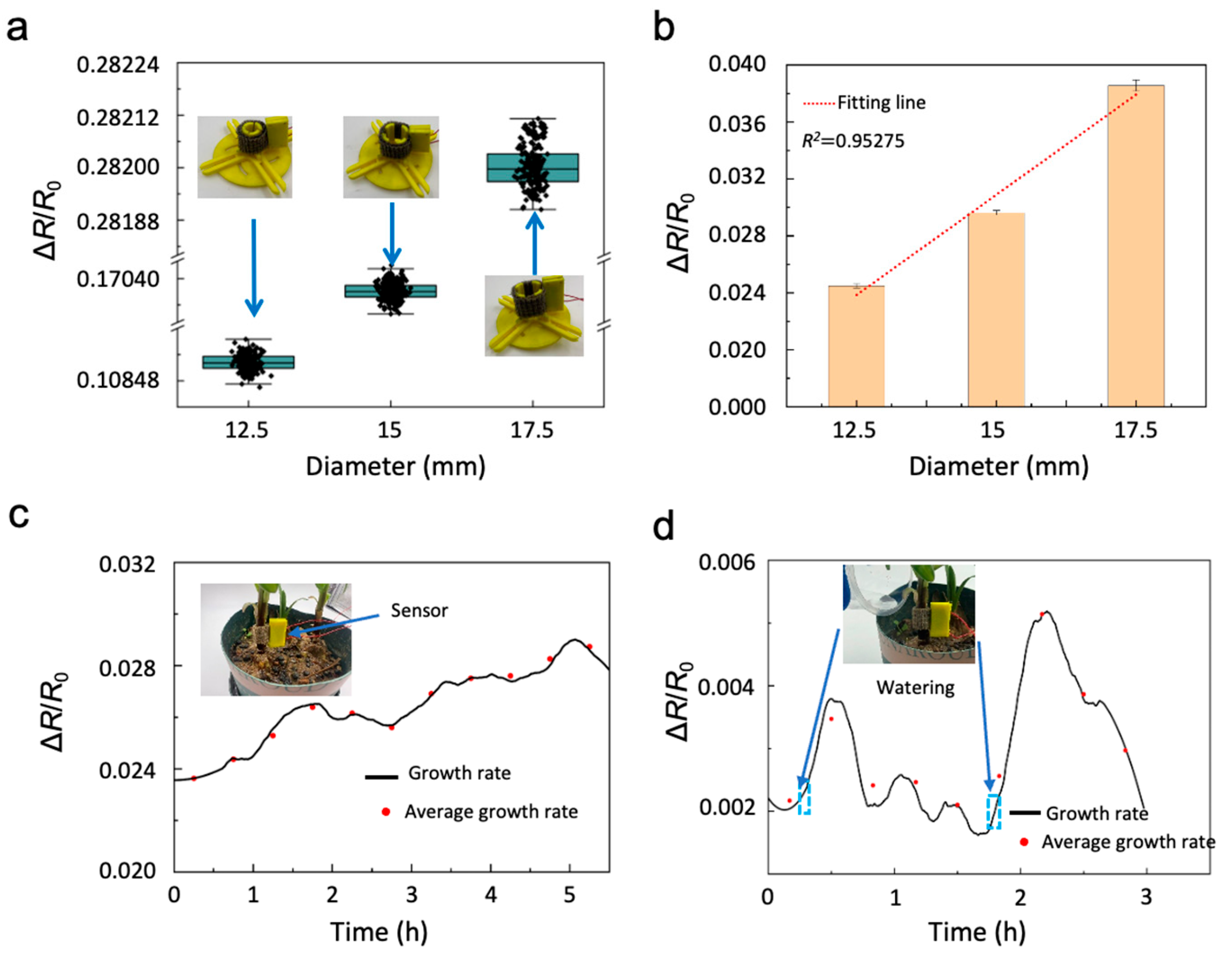

3.3. Applications of the Sensor in Plant Growth Monitoring

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alqaderi, A.I.J.; Ramakrishnan, N. Carbon-Based Flexible Strain Sensors: Recent Advances and Performance Insights in Human Motion Detection. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 513, 162609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Fang, M.; Liu, C.; Min, X. Flexible Strain Sensors Based on MWCNTs/rGO Hybrid Conductive Networks for Human Motion Detection and Thermal Management. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 696, 162949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, J.; Liu, Y. An Integrated Flexible Sensor for Decoupled Omnidirectional Strain and Human Motion Monitoring. Mater. Today Adv. 2025, 28, 100641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Chu, Z.; Fu, L.; Lv, Y.; Liu, X.; Fan, X.; Zhang, W. Thickness-Induced Gradient Micro-Wrinkle PDMS/MXene/rGO Wearable Strain Sensor with High Sensitivity and Stretchability for Human Motion Detection. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 495, 153684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Singh, R.; Das, A.; Bag, S.; Paily, R.P.; Manna, U. Abrasion Tolerant, Non-Stretchable and Super-Water-Repellent Conductive & Ultrasensitive Pattern for Identifying Slow, Fast, Weak and Strong Human Motions under Diverse Conditions. Mater. Horiz. 2021, 8, 2851–2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Yan, T.; Wang, F.; Yang, J.; Wu, J.; Wang, J.; Yue, T.; Li, Z. Rapid Fabrication of Wearable Carbon Nanotube/Graphite Strain Sensor for Real-Time Monitoring of Plant Growth. Carbon 2019, 147, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Cao, J.; Zheng, W.; Zhao, Q.; Chen, W.; Xu, X.; Luo, X.; Liu, Q.; Liu, X.; et al. Low Hysteresis and Fatigue-Resistant Polyvinyl Alcohol/Activated Charcoal Hydrogel Strain Sensor for Long-Term Stable Plant Growth Monitoring. Polymers 2022, 15, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, C.; Cao, L.; Li, M.; Wang, X.; He, Z. Liquid Metal-Based Plant Electronic Tattoos for in-Situ Monitoring of Plant Physiology. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2023, 66, 1617–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Edupulapati, B.; Hagel, J.M.; Kwok, J.J.; Quebedeaux, J.C.; Khasbaatar, A.; Baek, J.M.; Davies, D.W.; Ella Elangovan, K.; Wheeler, R.M.; et al. Highly Stretchable, Robust, and Resilient Wearable Electronics for Remote, Autonomous Plant Growth Monitoring. Device 2024, 2, 100322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Dai, W.; Kong, J.; Wang, G.; Zhou, H.; Yu, S. High-Performance Multifunctional Flexible Strain Sensors Based on Plant Leaf-Inspired Hierarchical Micropore Structures. Langmuir 2025, 41, 28180–28192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Baek, J.M.; Lau, A.P.; Quebedeaux, J.C.; Leakey, A.D.B.; Diao, Y. Light-Stable, Ultrastretchable Wearable Strain Sensors for Versatile Plant Growth Monitoring. ACS Sens. 2025, 10, 3390–3401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Zhou, J.; Long, X.; Zhuo, F.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Xie, J.; Duan, H.; Fu, Y. Fibrous Mats Based Skin Sensor with Ultra-Sensitivity and Anti-Overshooting Dynamic Stability Enhanced with Artificial Intelligence. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 473, 145054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Liu, W.; Luo, Q.; Lv, Z.; Yao, L.; Wei, F. Erasable and Multifunctional On-Skin Bioelectronics Prepared by Direct Writing. ACS Sens. 2025, 10, 2850–2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Ma, Z.; Hu, Z.; Long, Y.; Wu, F.; Huang, X.; Nisa, F.U.; Liang, H.; Dong, Y.; Wang, J.; et al. Synergistic Enhancement of Hole–Bridge Structure and Molecular-crowding Effect in Multifunctional Eutectic Hydrogel Strain/Pressure Sensor for Personal Rehabilitation Training. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2502844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, M.; Shim, H.J.; Ghaffari, R.; Cho, H.R.; Son, D.; Jung, Y.H.; Soh, M.; Choi, C.; Jung, S.; et al. Stretchable Silicon Nanoribbon Electronics for Skin Prosthesis. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Han, L.; Huang, H.; Xuan, X.; Pan, G.; Wan, L.; Lu, T.; Xu, M.; Pan, L. A Direction-Aware and Ultrafast Self-Healing Dual Network Hydrogel for a Flexible Electronic Skin Strain Sensor. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 26109–26118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgopoulou, A.; Eckey, L.M.; Clemens, F. A Prosthetic Hand with Integrated Sensing Elements for Selective Detection of Mechanical and Thermal Stimuli. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2023, 5, 2300122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Wu, Y.; Ma, S.; Yan, T.; Pan, Z. Flexible Strain Sensor Based on CNT/TPU Composite Nanofiber Yarn for Smart Sports Bandage. Compos. Part B 2022, 232, 109605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Qiu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Rein, M.; Stolyarov, A.; Zhang, J.; Seidel, G.D.; Johnson, B.N.; Wang, A.; Jia, X. Fiber-based Miniature Strain Sensor with Fast Response and Low Hysteresis. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2403918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhang, X. A Focused Review on the Flexible Wearable Sensors for Sports: From Kinematics to Physiologies. Micromachines 2022, 13, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Yang, F.; Wu, M.; Sui, Y.; Guo, D.; Li, M.; Kang, Z.; Sun, J.; Liu, J. A Super-stretchable and Highly Sensitive Carbon Nanotube Capacitive Strain Sensor for Wearable Applications and Soft Robotics. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2022, 7, 2100769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karipoth, P.; Chandler, J.H.; Lee, J.; Taccola, S.; Macdonald, J.; Valdastri, P.; Harris, R.A. Aerosol Jet Printing of Strain Sensors for Soft Robotics. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2024, 26, 2301275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Liao, Z.; Shang, J.; Gan, W.; Kong, X.; Wei, X. A Review on Real-Time Plant Monitoring Sensors for Smart Agriculture. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 523, 168868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, W.; Li, H.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, L.; Xu, J.; Huang, Y.; Lu, B. Ultrasoft, Anti-Dehydrated, and Highly Stretchable Carboxymethylcellulose-Based Organohydrogel Strain Sensors for Non-Invasive Real-Time Plant Growth Monitoring. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 364, 123753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Li, P.; Liu, Z.; Kang, J.; Liu, K.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, C.; Tang, J.; Cheng, J. Highly Stretchable and Reliable Graphene-Based Strain Sensor for Plant Health Monitoring and Deep Learning-Assisted Crop Recognition. Research 2025, 8, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akcan, Ö.G.; Gaber, M.M.; Baran, E.A.; Gökdel, Y.D. Development of a Disposable Silicone–Graphite Composite Strain Sensor for Soft Robotics Applications. Sens. Actuators A 2025, 391, 116527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lin, X.; Yao, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Gong, N. Plant Growth Monitoring, Prediction, and Self-Regulation Utilizing MXene/CNTs/TPU Flexible Strain Sensors Integrated with Deep Learning Algorithms and Soft Actuators. Sci. China Mater. 2025, 68, 3715–3727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, W.; Wan, R.; Yao, M.; Chen, W.; Zhang, L.; Xu, J.; Liu, X.; Lu, B. All 3D-Printed High-Sensitivity Adaptive Hydrogel Strain Sensor for Accurate Plant Growth Monitoring. Soft Sci. 2025, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Liu, S.; Guo, Y.; Yang, L.; Jiang, K. Anisotropic Flexible Pressure/Strain Sensors: Recent Advances, Fabrication Techniques, and Future Prospects. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 504, 158799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.; Wang, Z.; Pan, Z.-J. Flexible Strain Sensors Fabricated Using Carbon-Based Nanomaterials: A Review. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2018, 22, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhuo, F.; Zhou, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Dong, S.; Liu, X.; Elmarakbi, A.; Duan, H.; Fu, Y. Advances in Graphene-Based Flexible and Wearable Strain Sensors. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 464, 142576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, B.; Li, D.; Yuan, J.; Huang, D.; Zhang, C.; Song, W.; Wang, C.; Wang, J.; Liu, L.; et al. Fiber-shaped, Stretchable Strain Sensors with High Linearity by One-step Injection Molding for Structural Health Monitoring. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2500701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Wang, C.; Liu, L.; Liu, Z.; He, J.; Zhang, C.; Duan, J. Bioinspired Stretchable Strain Sensor with High Linearity and Superhydrophobicity for Underwater Applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2413552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, L.; Le, X.; Dong, H.; Xie, J.; Ying, Y.; Ping, J. One-Step and Large-Scale Fabrication of Flexible and Wearable Humidity Sensor Based on Laser-Induced Graphene for Real-Time Tracking of Plant Transpiration at Bio-Interface. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020, 165, 112360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Yan, T.; Ping, J.; Wu, J.; Ying, Y. Rapid Fabrication of Flexible and Stretchable Strain Sensor by Chitosan-based Water Ink for Plants Growth Monitoring. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2017, 2, 1700021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Kim, J.; Kang, J.; Lee, B.; Lee, H.; Park, C.; Yoon, J.; Song, C.; Kim, H.; Yeo, W.-H.; et al. Coatable Strain Sensors for Nonplanar Surfaces. Nanoscale 2024, 16, 14143–14154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Liu, Q.; Li, J.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Cao, M.; Wei, X.; Sun, C.-L.; He, J.; Qu, M. Advances in Rubber-Based Piezoresistive Flexible Strain Sensors. Mater. Today Phys. 2025, 58, 101847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.; Liang, S.; Zou, H.; Wang, X. Structure, Principle and Performance of Flexible Conductive Polymer Strain Sensors: A Review. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2024, 35, 775–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, S.; Ravi Sankar, A. Intrinsically Conducting Polymers in Flexible and Stretchable Resistive Strain Sensors: A Review. J. Mater. Sci. 2022, 57, 13152–13178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsarimanesh, N.; Nag, A.; Sarkar, S.; Sabet, G.S.; Han, T.; Mukhopadhyay, S.C. A Review on Fabrication, Characterization and Implementation of Wearable Strain Sensors. Sens. Actuators A 2020, 315, 112355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Wu, Y.; Tang, J.; Fu, J.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, J.; Pan, Z.; Yan, T. Digitally Interactive Smart Textiles in Football Prepared by an Outstanding Viscose-Based Flexible Strain Sensor. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 515, 163421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Liu, N.; Yin, J.; Tian, H.; Yang, Y.; Ren, T.-L. Understanding the Origin of Tensile Response in a Graphene Textile Strain Sensor with Negative Differential Resistance. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 14230–14238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, S.; Wang, X.; Chen, X.; He, Z.; Liu, L.; Jiang, X. A Breathable, Low-Cost, and Highly Stretchable Medical-Textile Strain Sensor for Human Motion and Plant Growth Monitoring. Sensors 2026, 26, 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010044

Liu S, Wang X, Chen X, He Z, Liu L, Jiang X. A Breathable, Low-Cost, and Highly Stretchable Medical-Textile Strain Sensor for Human Motion and Plant Growth Monitoring. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):44. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010044

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Shilei, Xin Wang, Xingze Chen, Zhixiang He, Linpeng Liu, and Xiaohu Jiang. 2026. "A Breathable, Low-Cost, and Highly Stretchable Medical-Textile Strain Sensor for Human Motion and Plant Growth Monitoring" Sensors 26, no. 1: 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010044

APA StyleLiu, S., Wang, X., Chen, X., He, Z., Liu, L., & Jiang, X. (2026). A Breathable, Low-Cost, and Highly Stretchable Medical-Textile Strain Sensor for Human Motion and Plant Growth Monitoring. Sensors, 26(1), 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010044