A Semantic-Associated Factor Graph Model for LiDAR-Assisted Indoor Multipath Localization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. LiDAR-Based Semantic Perception

2.2. Multipath Processing for Localization and Navigation

2.3. Multipath Estimation Based on Object Tracking

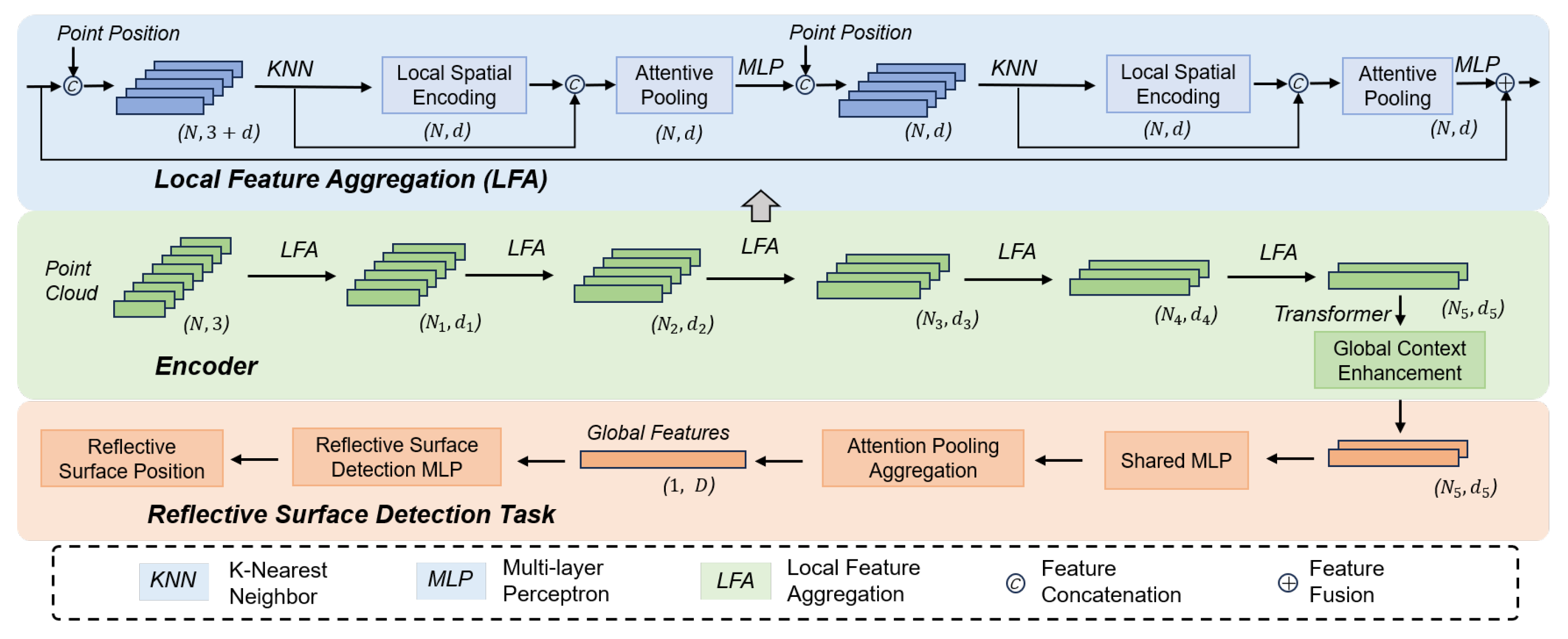

3. LiDAR Point Cloud-Based Reflective Surface Detection Methods

4. Factor Graph-Based Multipath Consistency Checking and Localization Method

4.1. System Model

4.2. Multi-Dimensional Data Association

4.3. Factor Graph-Based Estimation Process

4.3.1. Estimated State

4.3.2. Factor Graph Design

4.4. The Calculation Process of Factor Graph

4.4.1. Temporal State Prediction for Terminal and Reflective Surfaces

4.4.2. State Transition and Update Between Anchors

4.4.3. Message Passing for Signal Measurement and LiDAR Perception Constraints

4.4.4. Data Association

4.4.5. State Update Messages

4.4.6. Final State Estimation

5. Experiments and Results

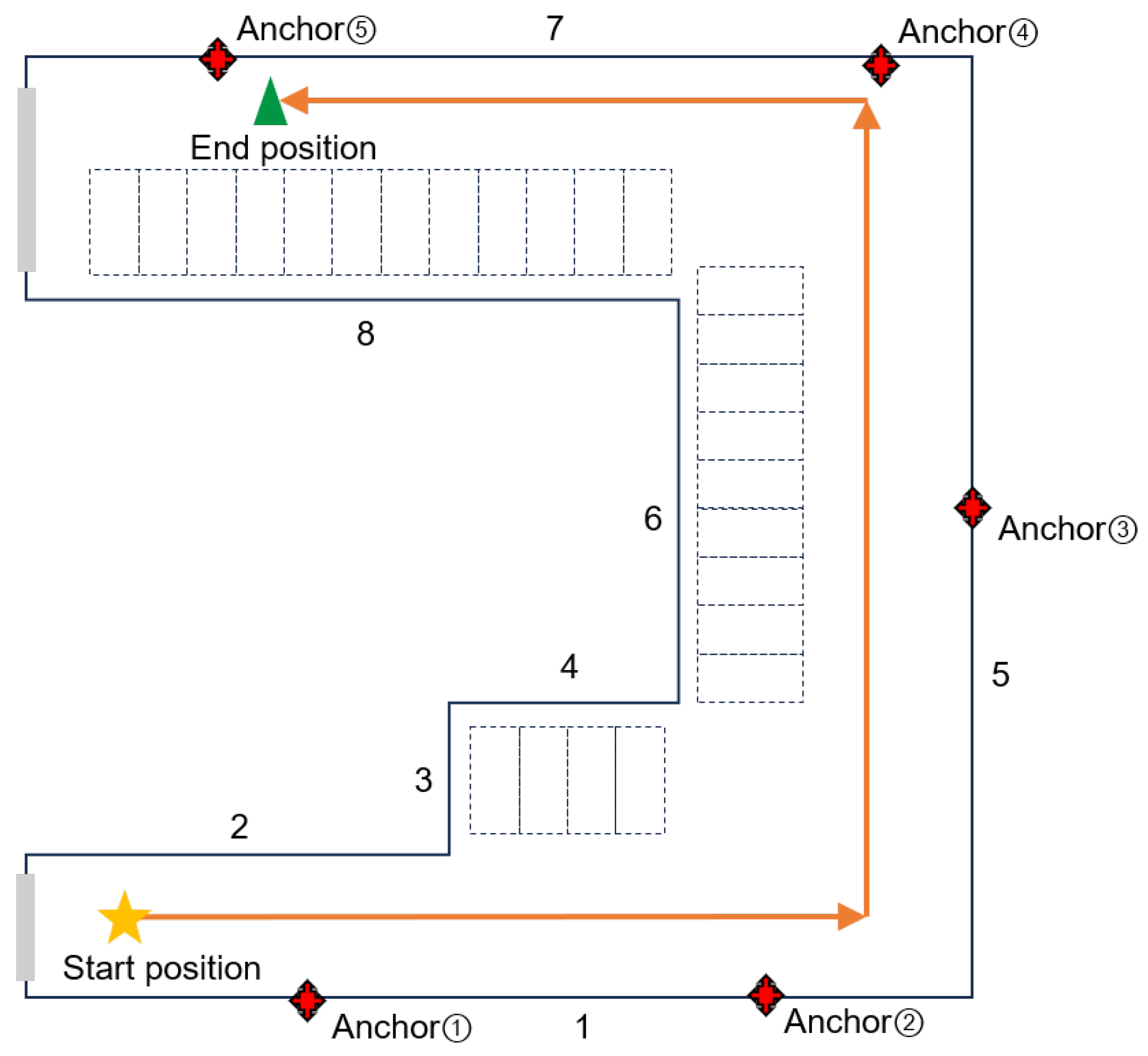

5.1. Experimental Setup

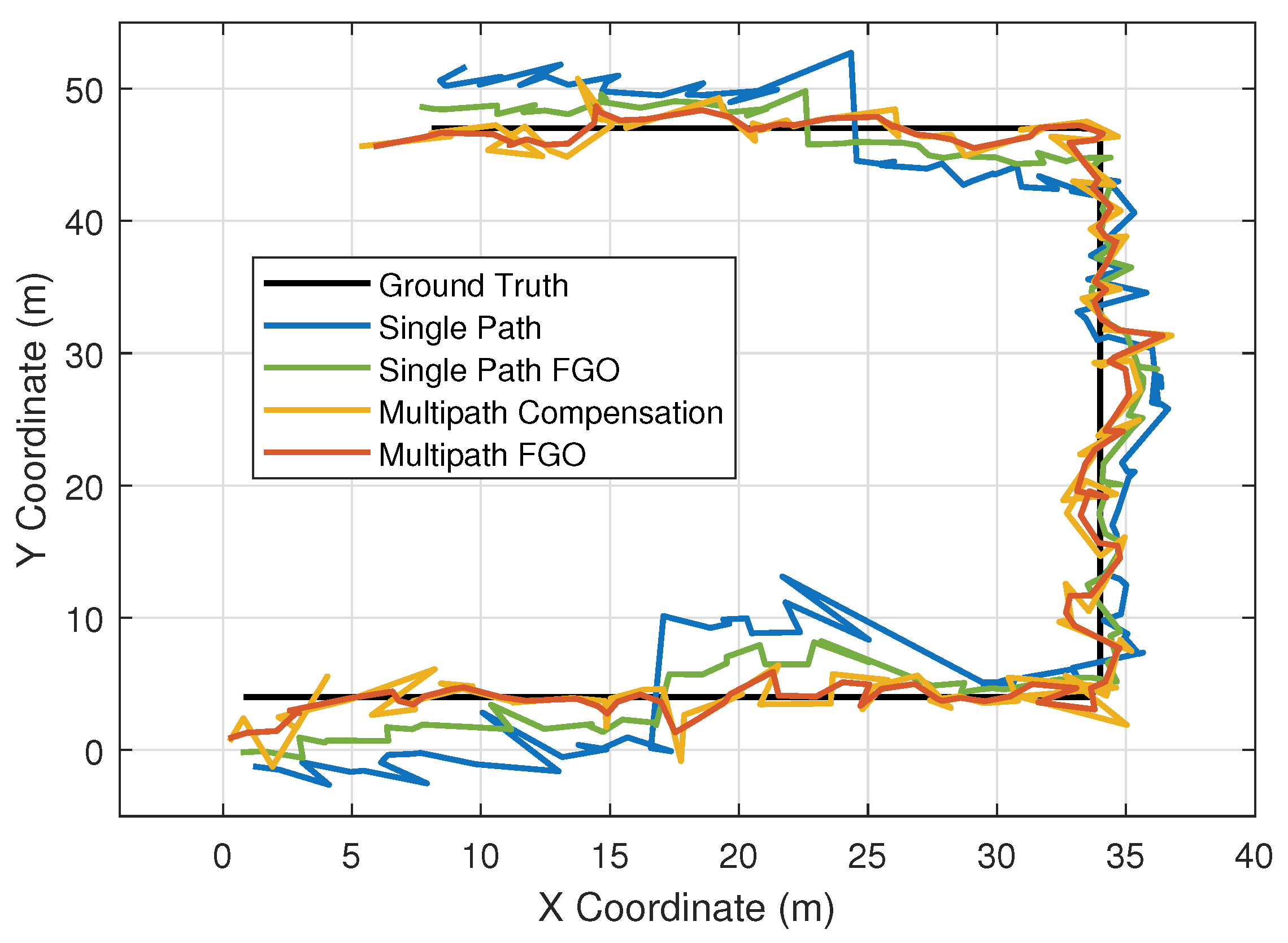

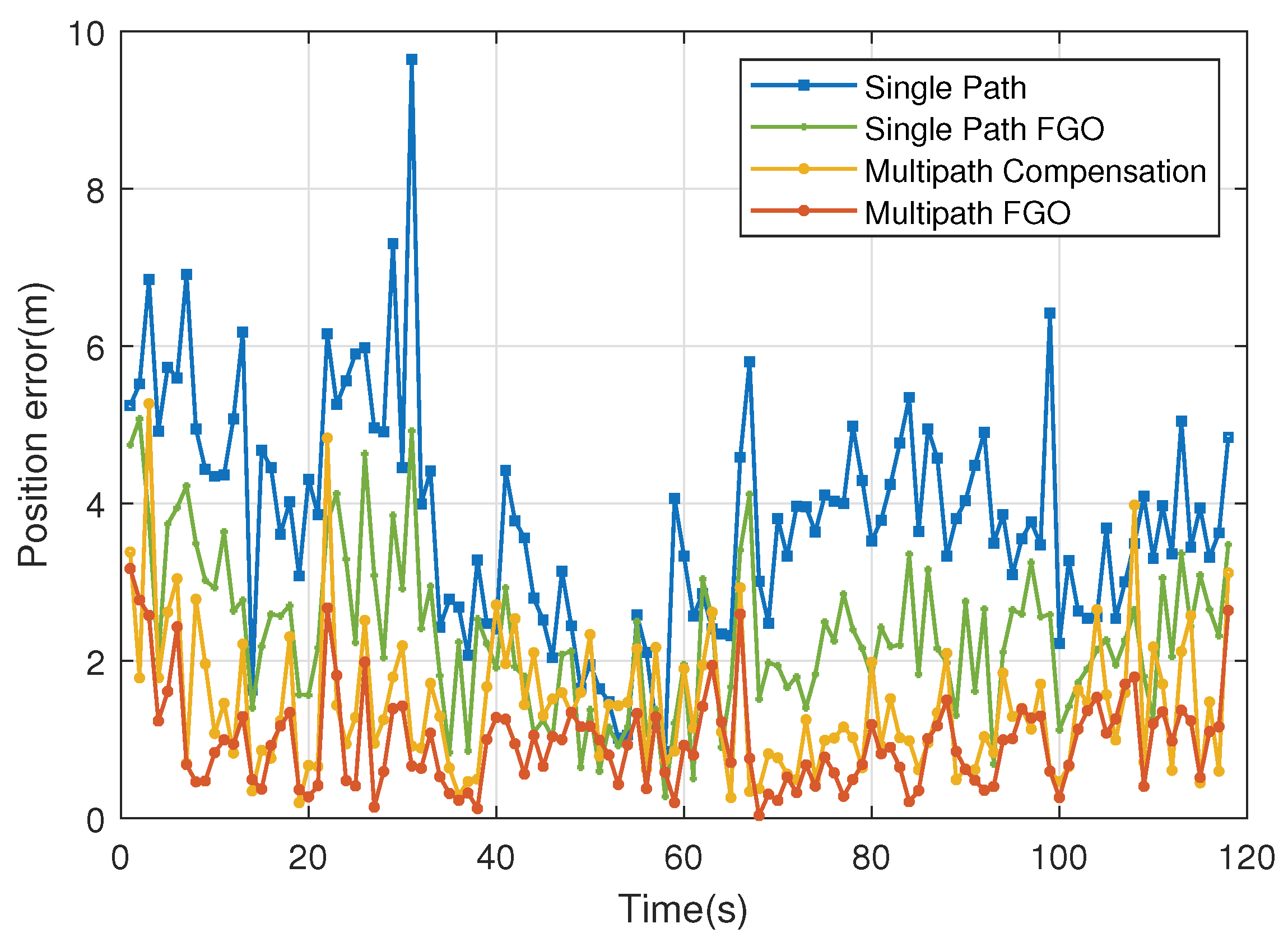

5.2. Terminal Positioning Experiment

5.2.1. Terminal Trajectory and Position Error

5.2.2. Comparison of Multiple Association Processes

5.2.3. Algorithm Speed Test

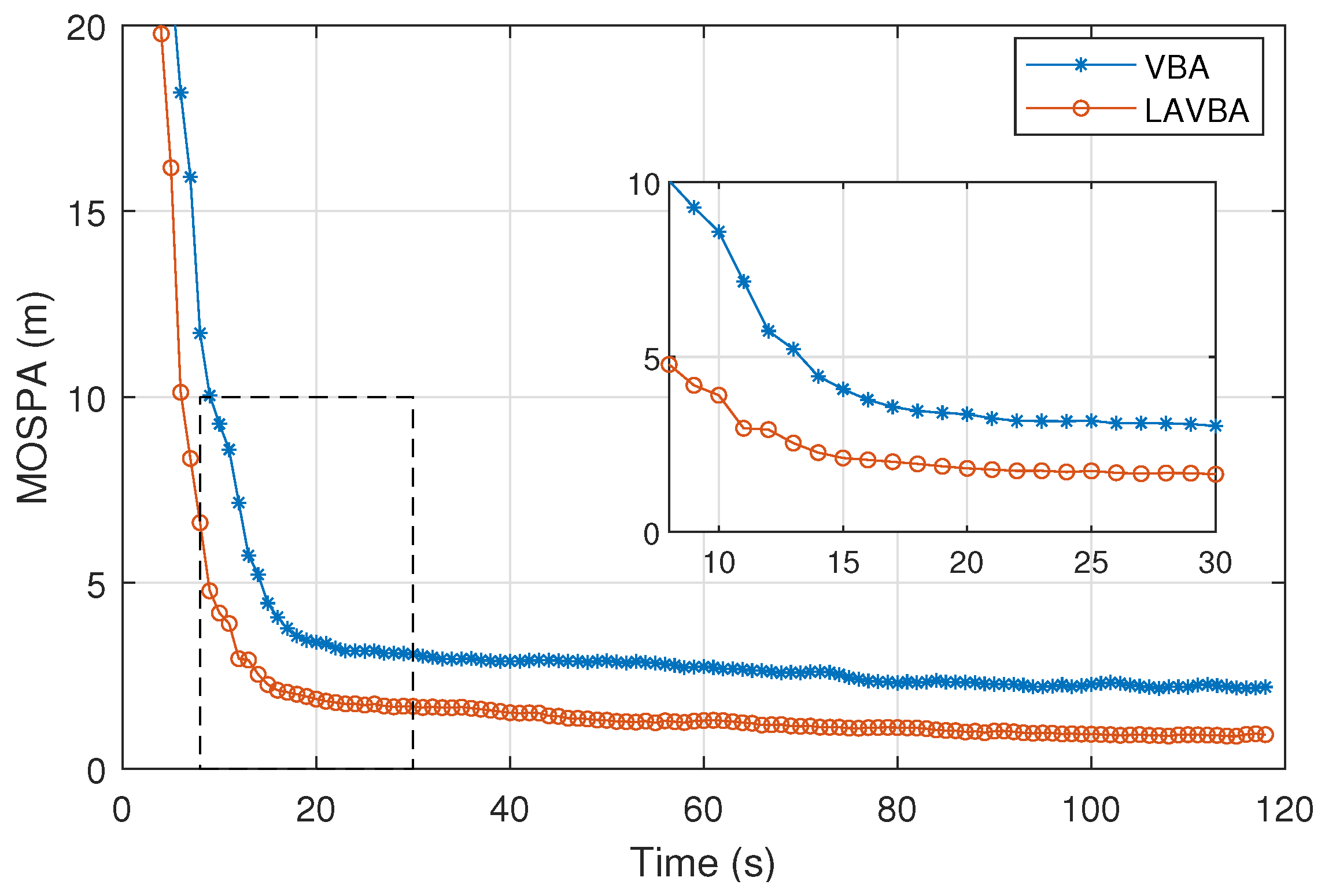

5.3. Multipath Estimation Experiment

5.3.1. Virtual Anchor Position Estimation

5.3.2. Reflective Surface Perception

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sun, Y.; Li, S.; Fu, L.; Yin, L.; Deng, Z. NICL: Non-Line-of-Sight Identification in Global Navigation Satellite Systems With Continual Learning. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2025, 74, 2480–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberto Matera, E.; Ekambi, B.; Chamard, J. A Comparative Analysis of GNSS Multipath Error Characterization Methodologies in an Urban Environment. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Localization and GNSS (ICL-GNSS), Antwerp, Belgium, 25–27 June 2024; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Wang, Y.; Ma, L.; Yang, S.; Feng, Z.; Pan, C.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wu, H.; Zhang, P. 5G PRS-Based Sensing: A Sensing Reference Signal Approach for Joint Sensing and Communication System. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 72, 3250–3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.M.; Law, C.L. GPS and UWB Integration for indoor positioning. In Proceedings of the 2007 6th International Conference on Information, Communications, Signal Processing, Singapore, 10–13 December 2007; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Hu, E.; Yang, S.; Yuen, C. Robust Short-Delay Multipath Estimation in Dynamic Indoor Environments for 5G Positioning. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 27871–27885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, C.X.; Zhou, Z.; Li, Y.; Huang, J.; Xin, L.; Pan, C.; Zheng, D.; Wu, X. Wireless Channel Measurements and Characterization in Industrial IoT Scenarios. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2025, 74, 2292–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Yao, Z.; Lu, M. Extended Double-Delta Correlator Technique for GNSS Multipath Mitigation. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2023, 59, 1758–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.; Liu, B.; Deng, Z. A Tightly Coupled Positioning Method of Ranging Signal and IMU Based on NLOS Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 12th International Conference on Indoor Positioning and Indoor Navigation (IPIN), Beijing, China, 5–7 September 2022; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, T.; Englot, B.; Ratti, C.; Rus, D. LVI-SAM: Tightly-coupled Lidar-Visual-Inertial Odometry via Smoothing and Mapping. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Xi’an, China, 30 May–5 June 2021; pp. 5692–5698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Pan, Y.; Li, C.; Geng, S.; Zhao, H. Are We Hungry for 3D LiDAR Data for Semantic Segmentation? A Survey of Datasets and Methods. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 6063–6081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitinger, E.; Meyer, F.; Hlawatsch, F.; Witrisal, K.; Tufvesson, F.; Win, M.Z. A Belief Propagation Algorithm for Multipath-Based SLAM. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2019, 18, 5613–5629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golovinskiy, A.; Kim, V.G.; Funkhouser, T. Shape-based recognition of 3D point clouds in urban environments. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE 12th International Conference on Computer Vision, Kyoto, Japan, 29 September–2 October 2009; pp. 2154–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackel, T.; Wegner, J.D.; Schindler, K. Fast Semantic Segmentation of 3D Point Clouds with Strongly Varying Density. In Proceedings of the XXIII ISPRS Congress, Commission III, Prague, Czech Republic, 12–19 July 2016; pp. 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, R.Q.; Su, H.; Kaichun, M.; Guibas, L.J. PointNet: Deep Learning on Point Sets for 3D Classification and Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Bu, R.; Sun, M.; Wu, W.; Di, X.; Chen, B. PointCNN: Convolution On X -Transformed Points. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 32nd Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS), Montreal, QC, Canada, 2–8 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, B.; Wan, A.; Yue, X.; Keutzer, K. SqueezeSeg: Convolutional Neural Nets with Recurrent CRF for Real-Time Road-Object Segmentation from 3D LiDAR Point Cloud. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Brisbane, Australia, 21–25 May 2018; pp. 1887–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rethage, D.; Wald, J.; Sturm, J.; Navab, N.; Tombari, F. Fully-Convolutional Point Networks for Large-Scale Point Clouds. In Proceedings of the 15th European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Pt. IV, Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 625–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrieu, L.; Simonovsky, M. Large-Scale Point Cloud Semantic Segmentation with Superpoint Graphs. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 4558–4567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodin, G.; Daly, P. GNSS code and carrier tracking in the presence of multipath. Int. J. Satell. Commun. 1997, 15, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, J.P.; Axelrad, P.; Anderson, S. A GNSS Code Multipath Model for Semi-Urban, Aircraft, and Ship Environments. Navigation 2007, 54, 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, V.; Axelrad, P. Advanced multipath modeling and validation for GPS onboard the International Space Station. Navigation 2019, 66, 559–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhoondzadeh-Asl, L.; Noori, N. Modification and Tuning of the Universal Okumura-Hata Model for Radio Wave Propagation Predictions. In Proceedings of the 2007 Asia-Pacific Microwave Conference, Bangkok, Tailand, 11–14 December 2007; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Morton, Y.J. Multipath Estimating Delay Lock Loop for LTE Signal TOA Estimation in Indoor and Urban Environments. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2020, 19, 5518–5530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Morton, Y.J.; Yu, W.; Truong, T.K. GPS L1CA/BDS B1I Multipath Channel Measurements and Modeling for Dynamic Land Vehicle in Shanghai Dense Urban Area. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2020, 69, 14247–14263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wymeersch, H.; Garcia, N.; Kim, H.; Seco-Granados, G.; Kim, S.; Wen, F.; Fröhle, M. 5G mm Wave Downlink Vehicular Positioning. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Global Communications Conference (GLOBECOM), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 9–13 December 2018; pp. 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendrzik, R.; Meyer, F.; Bauch, G.; Win, M.Z. Enabling Situational Awareness in Millimeter Wave Massive MIMO Systems. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 2019, 13, 1196–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentner, C.; Jost, T.; Wang, W.; Zhang, S.; Dammann, A.; Fiebig, U.C. Multipath Assisted Positioning with Simultaneous Localization and Mapping. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2016, 15, 6104–6117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Fan, J.; Zhai, S.; Dai, G. Message Passing Based Wireless Multipath SLAM With Continuous Measurements Correction. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2024, 72, 1691–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Yang, B.; Xie, L.; Rosa, S.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Z.; Trigoni, N.; Markham, A. RandLA-Net: Efficient Semantic Segmentation of Large-Scale Point Clouds. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 11105–11114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitinger, E.; Venus, A.; Teague, B.; Meyer, F. Data Fusion for Multipath-Based SLAM: Combining Information From Multiple Propagation Paths. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2023, 71, 4011–4028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuhmacher, D.; Vo, B.T.; Vo, B.N. A Consistent Metric for Performance Evaluation of Multi-Object Filters. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2008, 56, 3447–3457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Notation | Definition | Notation | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2D position of physical anchor j | 2D position of mobile terminal at time n | ||

| j | Index of physical anchor (, J is total number of physical anchors) | Virtual anchor position of physical anchor j corresponding to reflective surface s | |

| n | Index of time epoch (, N is total number of epochs) | Position of Virtual Base Anchor (VBA) corresponding to reflective surface s | |

| s | Index of reflective surface/VBA (, S is total number of reflective surfaces) | LiDAR-perceived VBA position of k-th candidate reflective surface | |

| m | Index of multipath component (, is number of multipath components for anchor j at epoch n) | State vector of mobile terminal at epoch n (, is velocity component) | |

| k | Index of LiDAR-detected candidate reflective surface (, is number of candidate surfaces at epoch n) | Binary existence variable of s-th reflective surface at epoch n (0: non-existent; 1: existent) | |

| m-th multipath component measurement of anchor j at epoch n | Retention probability of reflective surface across epochs (decay factor) | ||

| Zero-mean Gaussian measurement noise of | Pruning threshold for VBAs (pruned if retention probability < ) |

| Signal Center Frequency | 3.5 GHz |

| Modulation Method | BPSK |

| Multiple Access Method | CDMA |

| Spreading Code Generation Method | Weil Code Set |

| Pseudo-code Length | 10,230 |

| Pseudo-code Frequency | 10.23 MHz |

| Single Path | Single Path FGO | Multipath Compensation | Multipath FGO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE(m) | 4.07 | 2.51 | 1.68 | 1.14 |

| Mean (m) | 3.81 | 2.31 | 1.43 | 0.97 |

| STD (m) | 1.41 | 0.97 | 0.89 | 0.61 |

| Max (m) | 9.64 | 5.07 | 5.26 | 3.17 |

| Min (m) | 0.84 | 0.27 | 0.19 | 0.03 |

| Single Path | Single Path FGO | Multipath Compensation | Multipath FGO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Single Computation Time (ms) | 1.3 | 10.9 | 8.7 | 45.1 |

| Recognition Precision | Center Point Error (m) | Normal Vector Error (°) | VBA Error (m) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PointCNN [14] | 87.1% | 0.34 | 1.27 | 2.37 |

| PointNet [15] | 83.7% | 0.39 | 1.12 | 2.21 |

| PointNet+CNN | 88.5% | 0.32 | 0.91 | 2.02 |

| Proposed | 91.2% | 0.26 | 0.76 | 1.82 |

| Network Parameters (MB) | Computational Complexity (G FLOPs) | |

|---|---|---|

| PointCNN | 0.6 | 25.3 |

| PointNet | 3.2 | 14.7 |

| PointNet+CNN | 2.6 | 13.4 |

| Proposed | 3.2 | 17.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, B.; Han, K.; Deng, Z.; Guo, G. A Semantic-Associated Factor Graph Model for LiDAR-Assisted Indoor Multipath Localization. Sensors 2026, 26, 346. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010346

Liu B, Han K, Deng Z, Guo G. A Semantic-Associated Factor Graph Model for LiDAR-Assisted Indoor Multipath Localization. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):346. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010346

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Bingxun, Ke Han, Zhongliang Deng, and Gan Guo. 2026. "A Semantic-Associated Factor Graph Model for LiDAR-Assisted Indoor Multipath Localization" Sensors 26, no. 1: 346. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010346

APA StyleLiu, B., Han, K., Deng, Z., & Guo, G. (2026). A Semantic-Associated Factor Graph Model for LiDAR-Assisted Indoor Multipath Localization. Sensors, 26(1), 346. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010346