Adaptive Thermal Imaging Signal Analysis for Real-Time Non-Invasive Respiratory Rate Monitoring

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

3. Materials and Methods

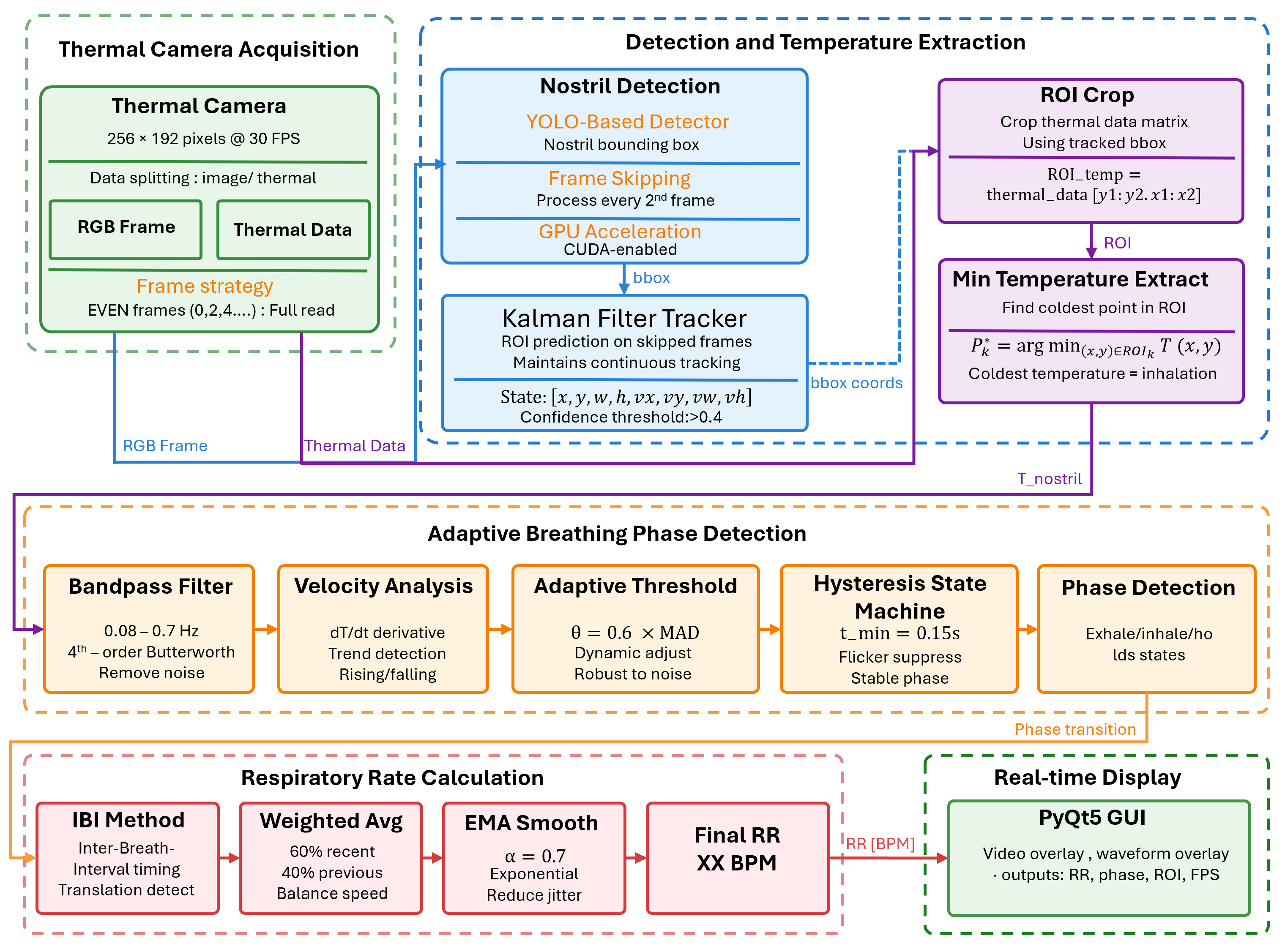

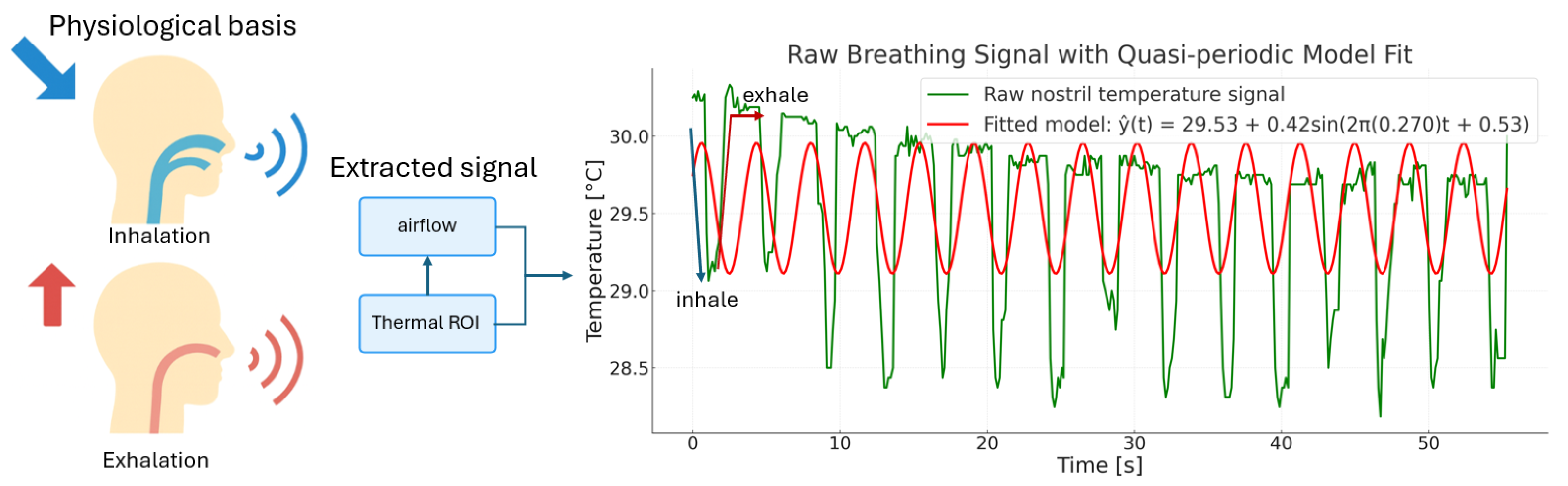

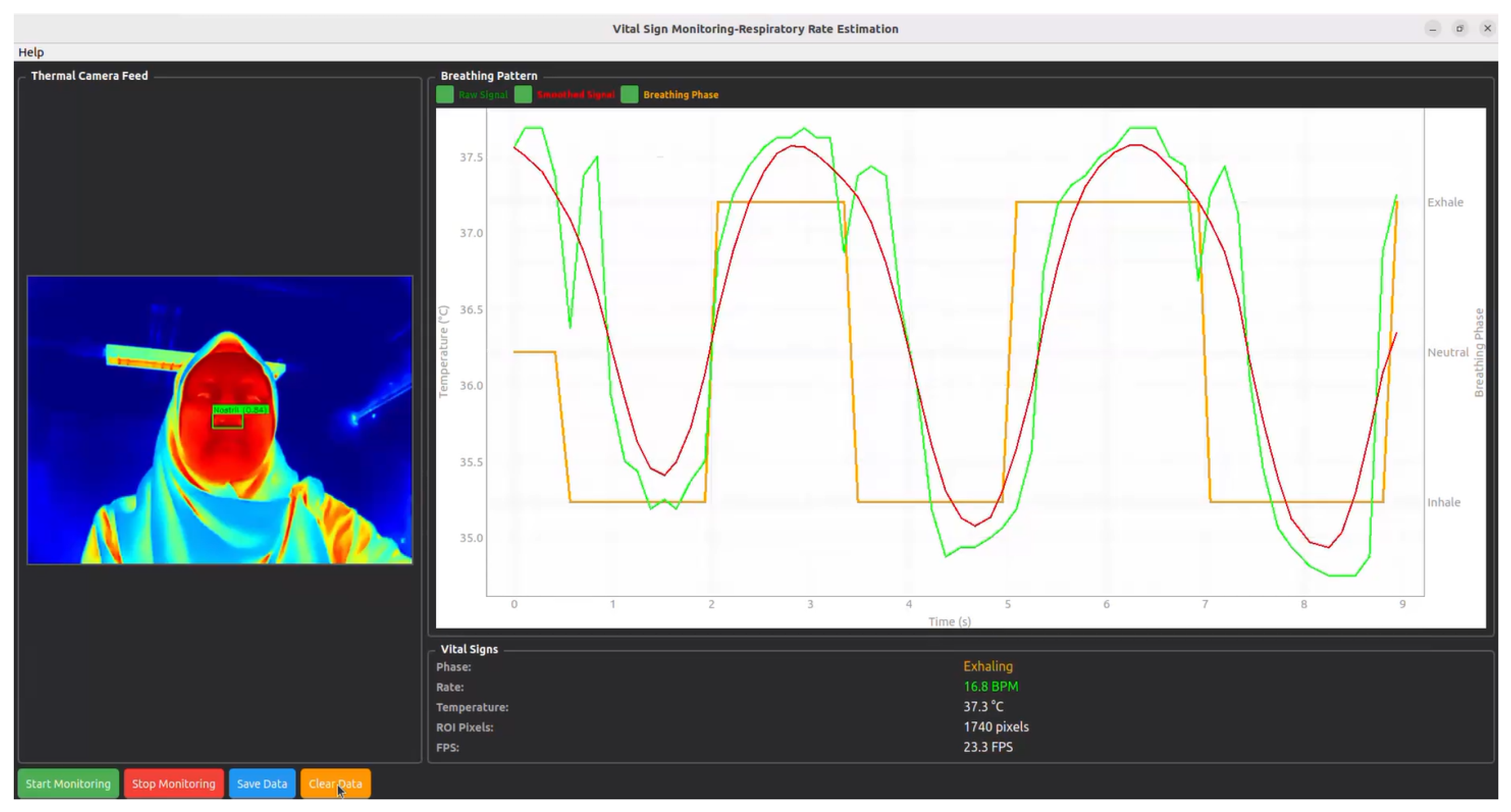

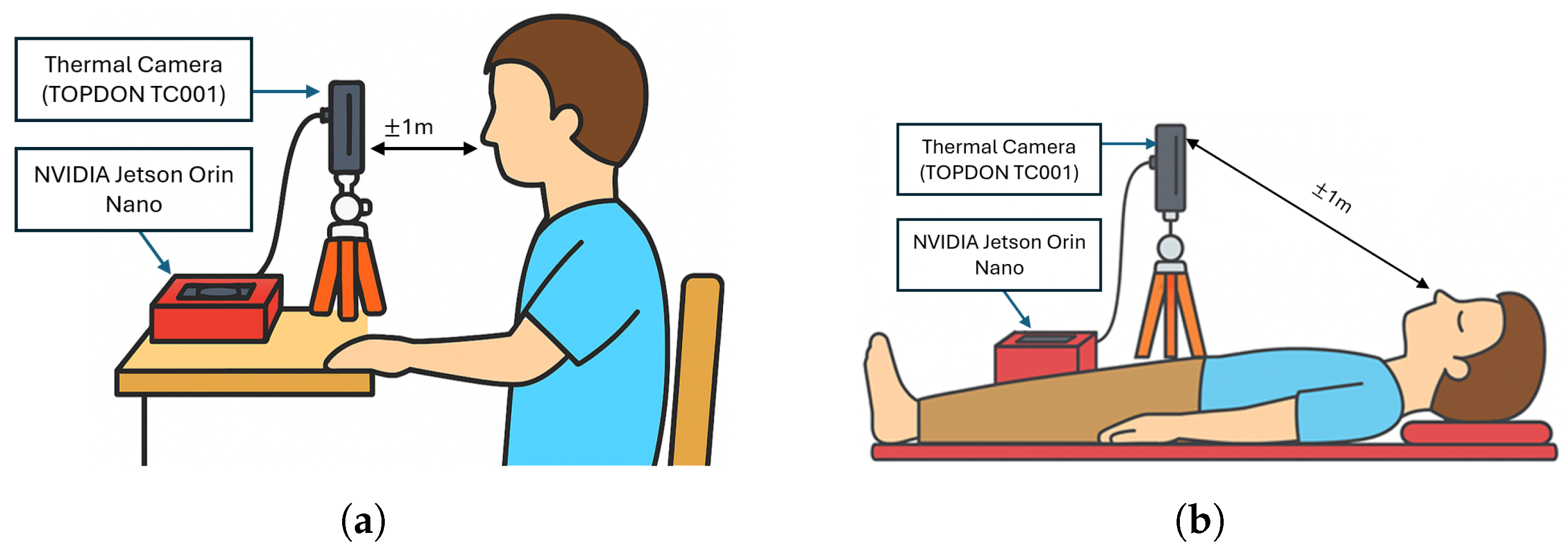

3.1. System Overview

3.2. Thermal Camera Acquisition

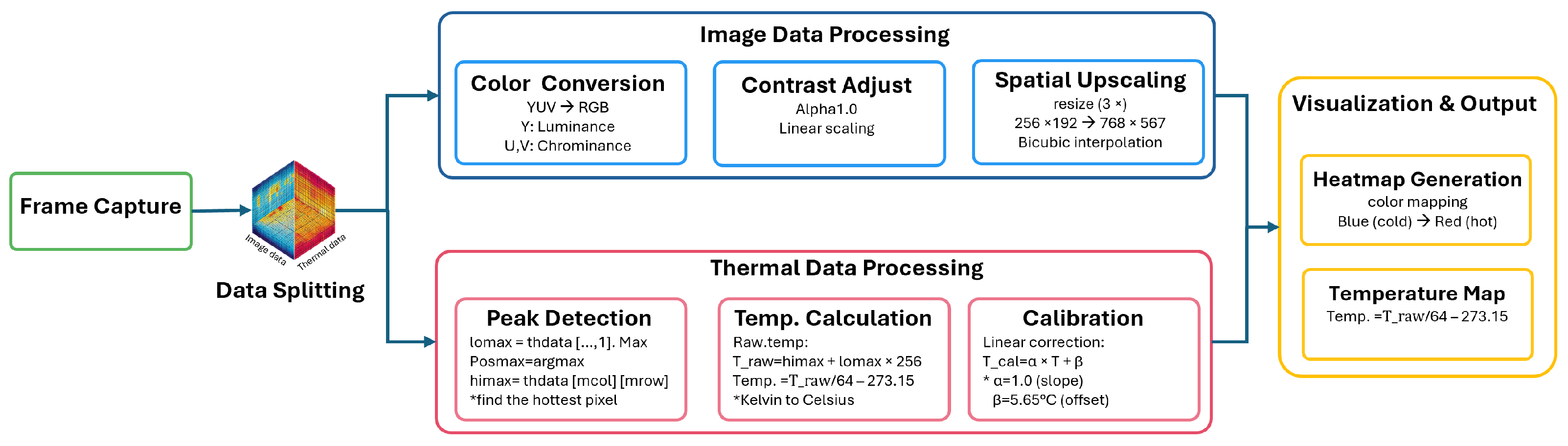

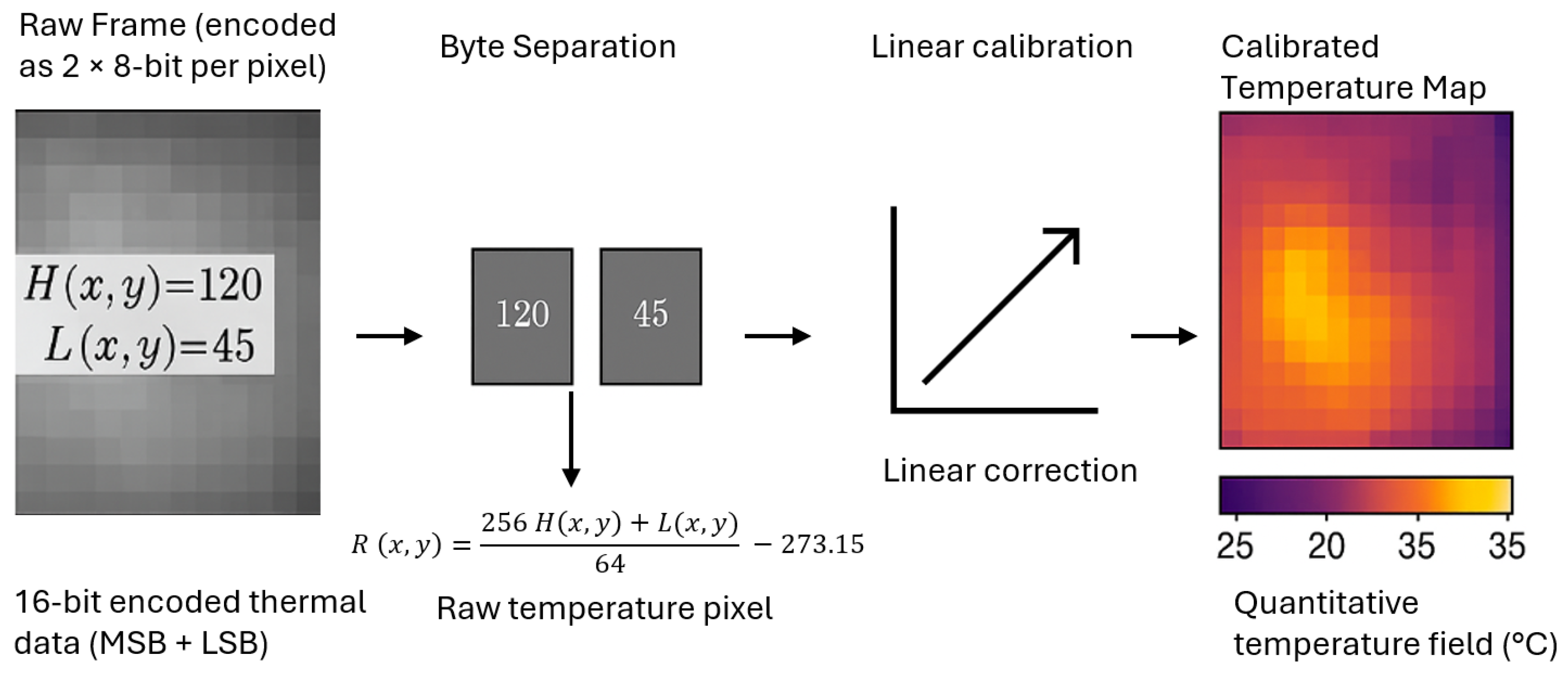

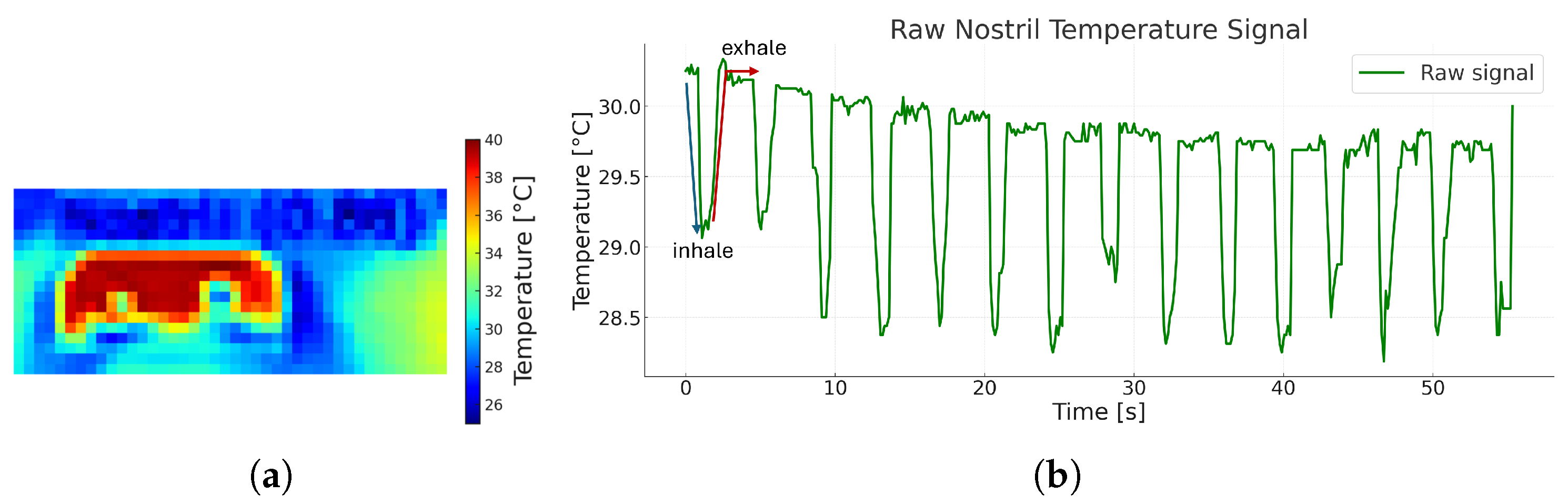

3.2.1. Image Data Processing

3.2.2. Thermal Data Processing

3.3. ROI Localization and Temperature Feature Extraction

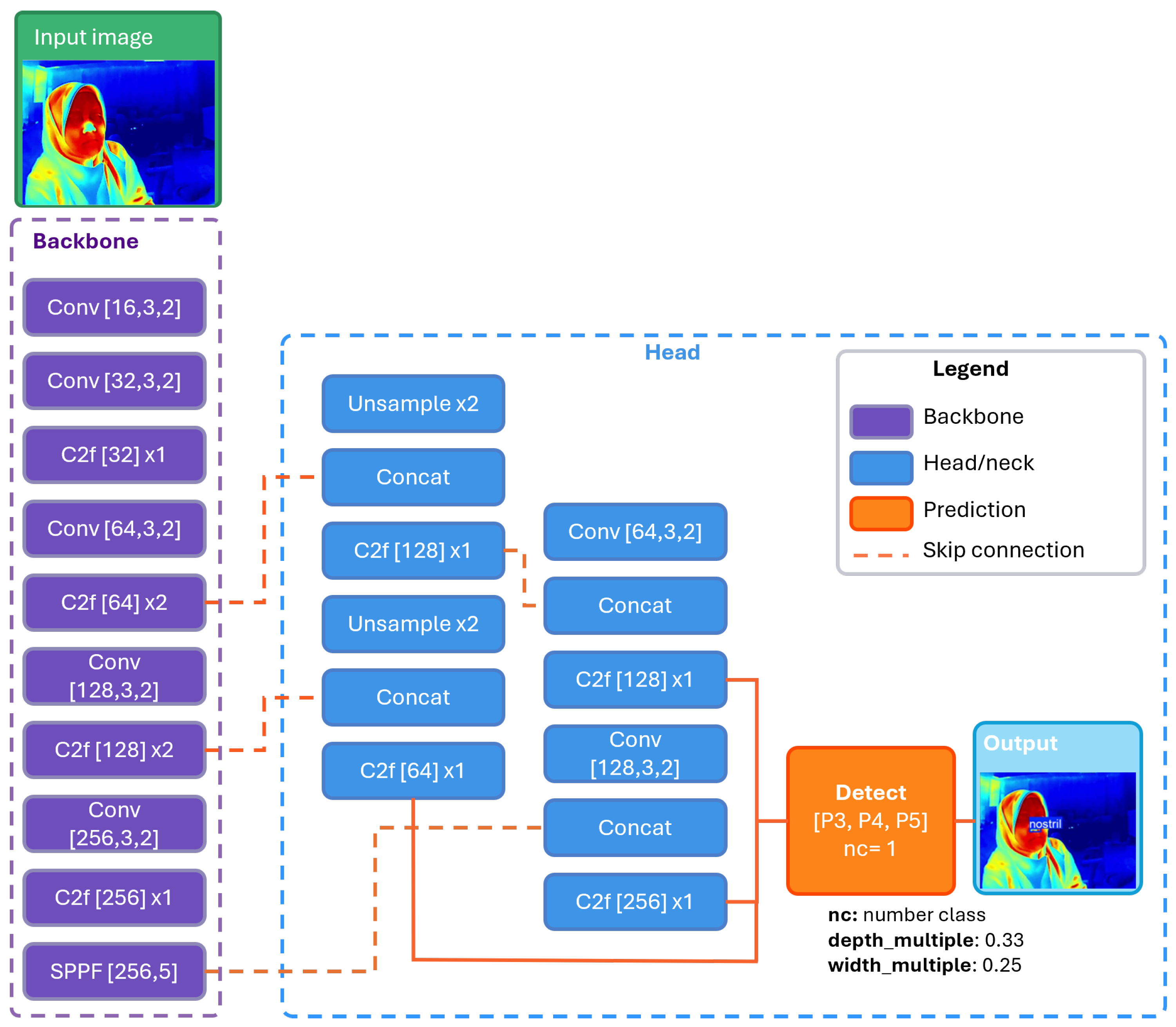

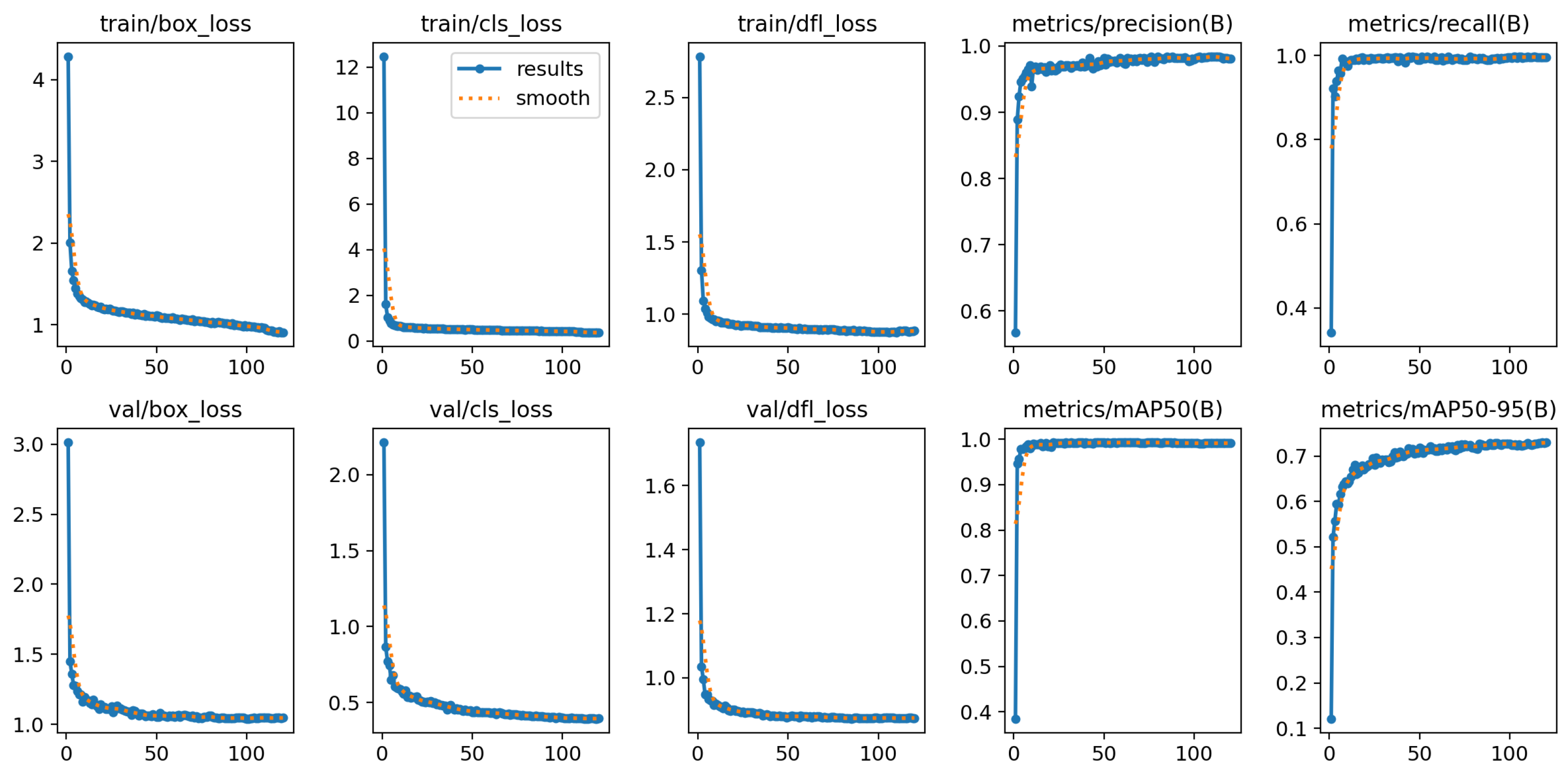

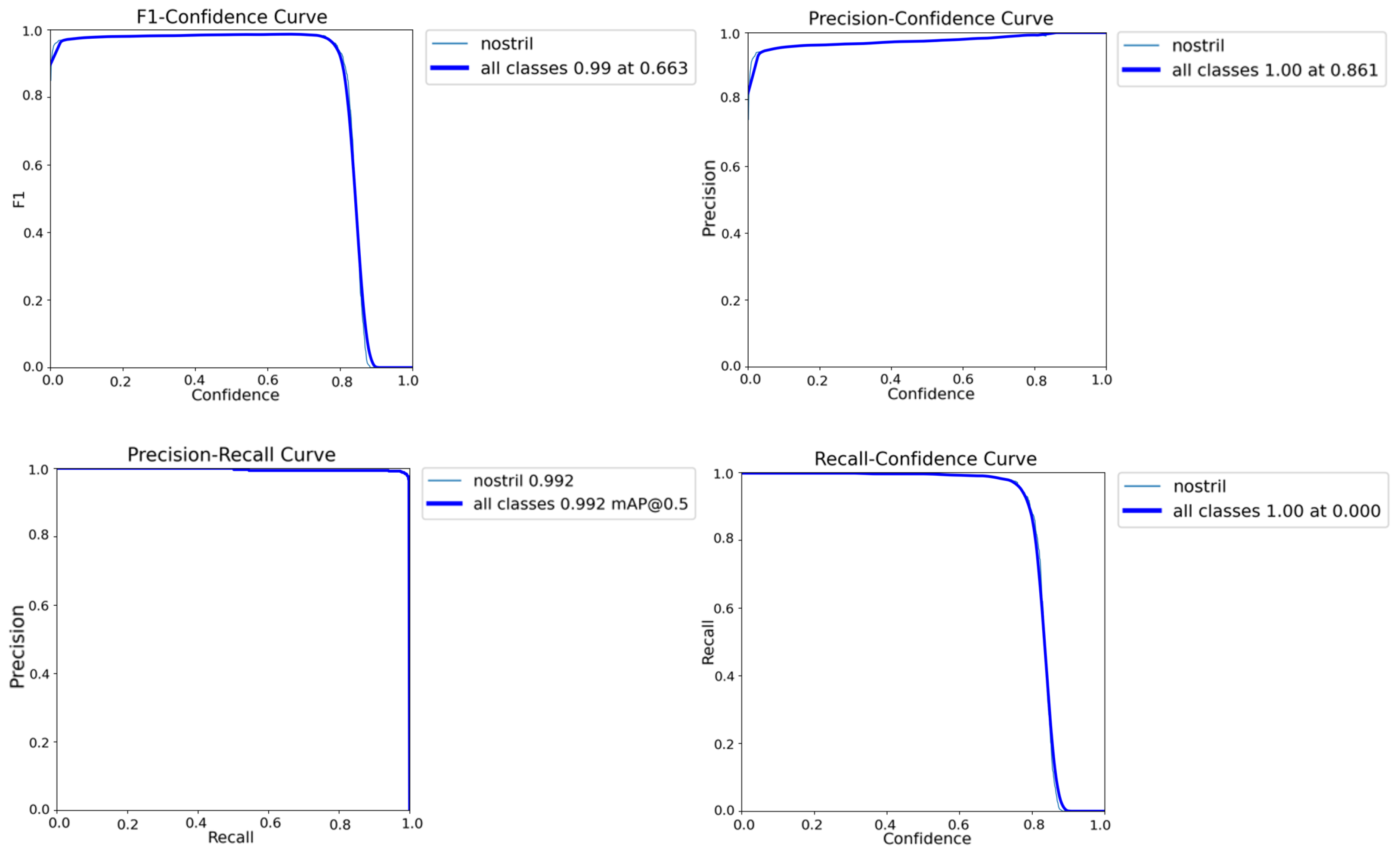

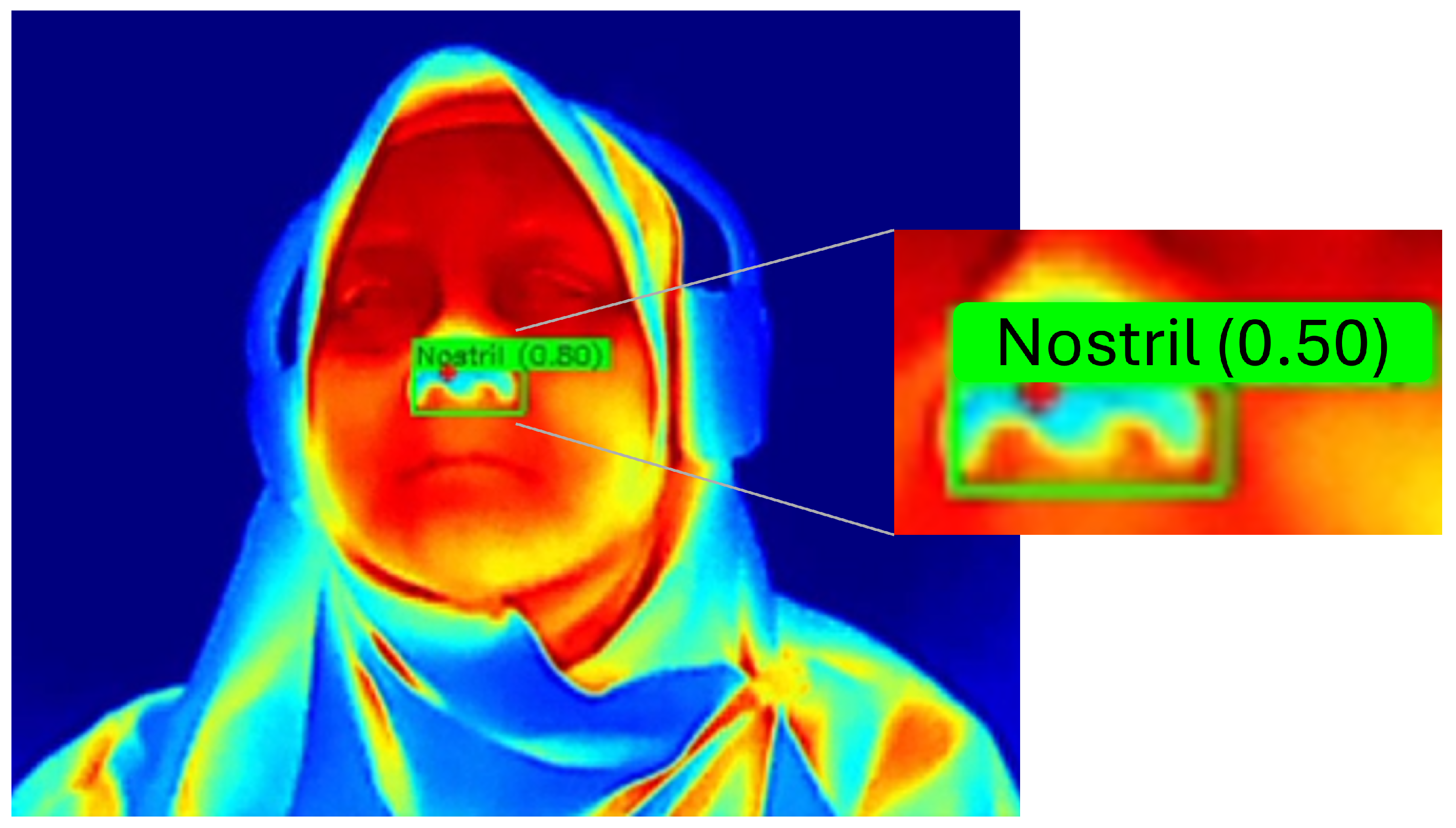

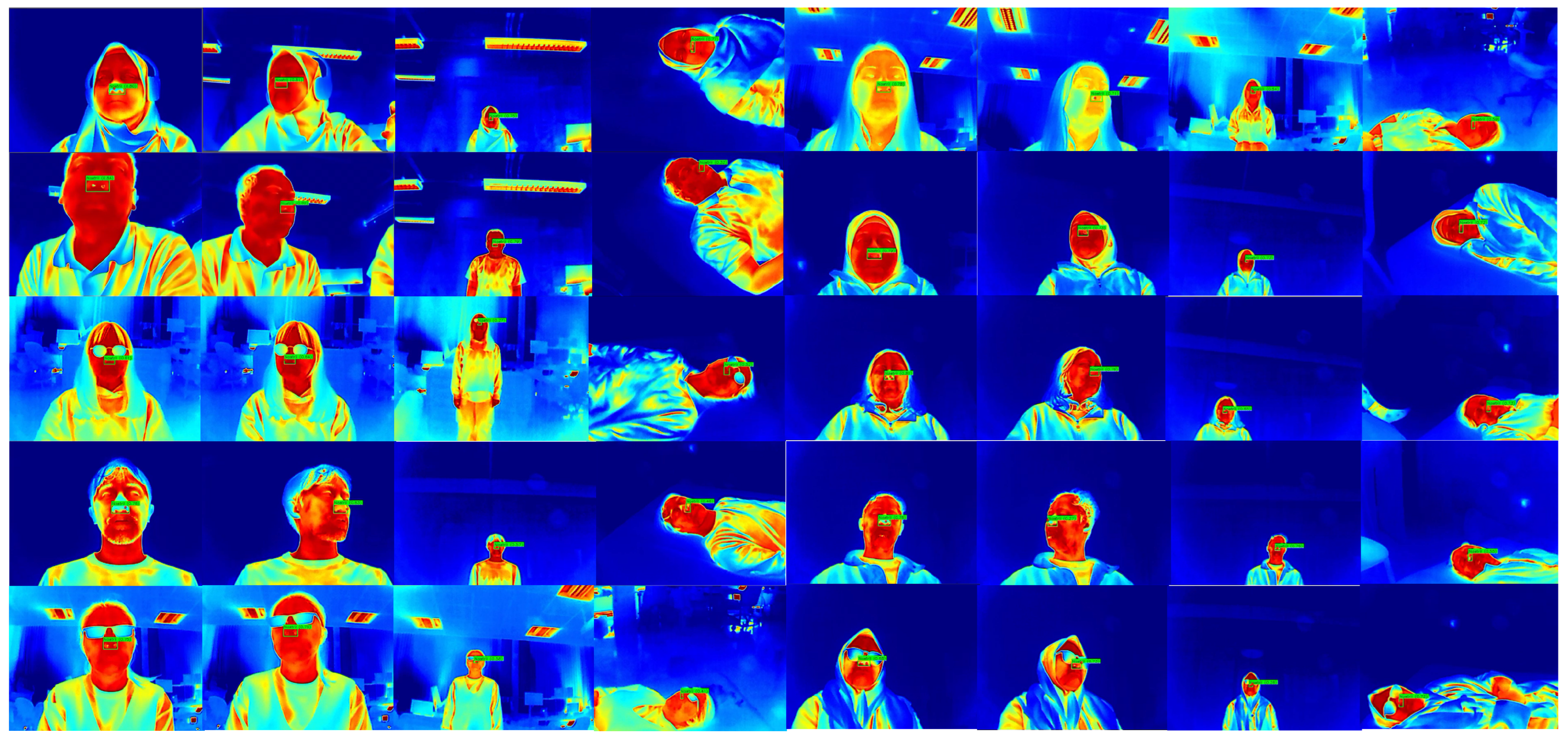

3.3.1. YOLO-Based Nostril Detection

3.3.2. Kalman Filter Tracking

3.3.3. Temperature Extraction

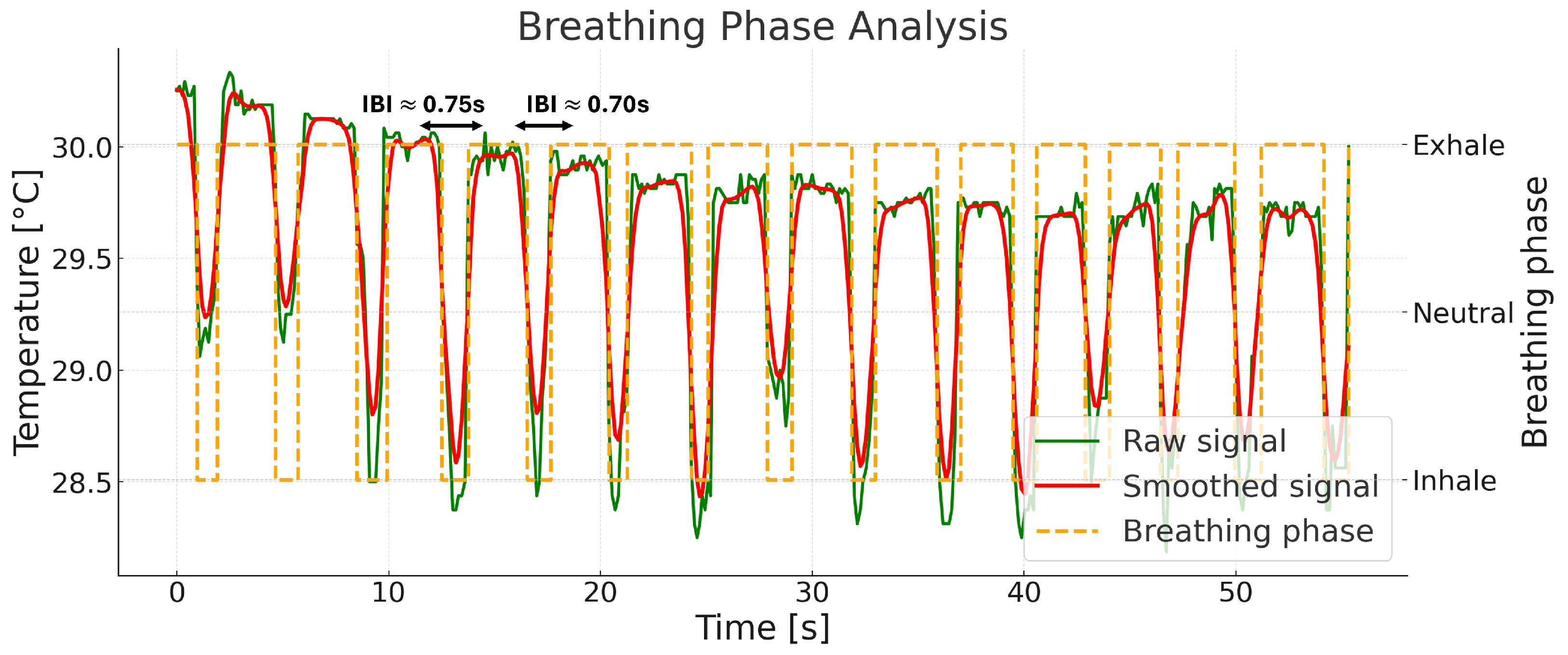

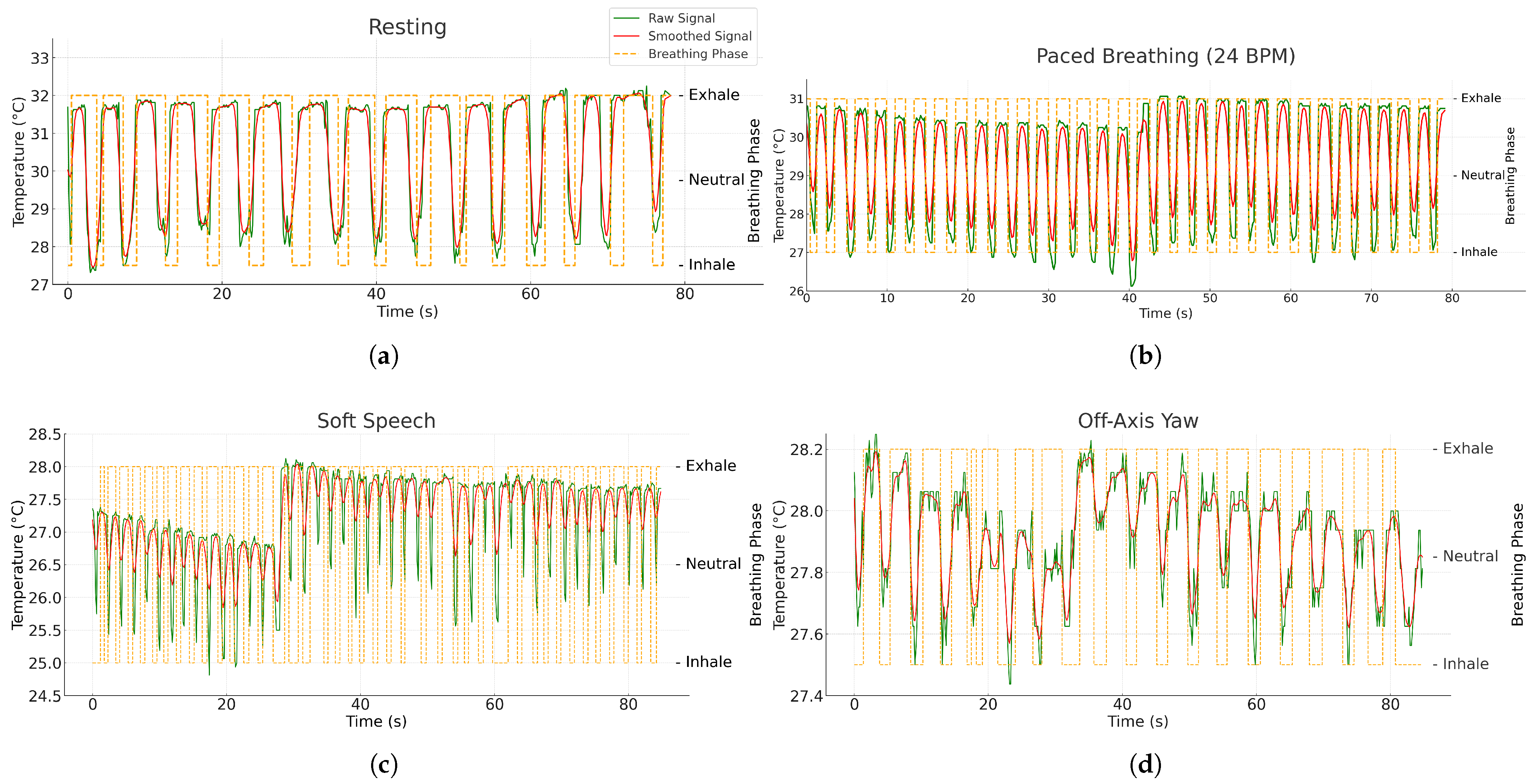

3.4. Adaptive Breathing Phase Detection and Respiratory Rate Calculation

3.4.1. Adaptive Breathing Phase Detection

3.4.2. Respiratory Rate Calculation

4. Experimental Results

4.1. Hardware and Software Configuration

4.2. Respiratory Rate Experimental Procedures

4.3. Nostril Detection Performance

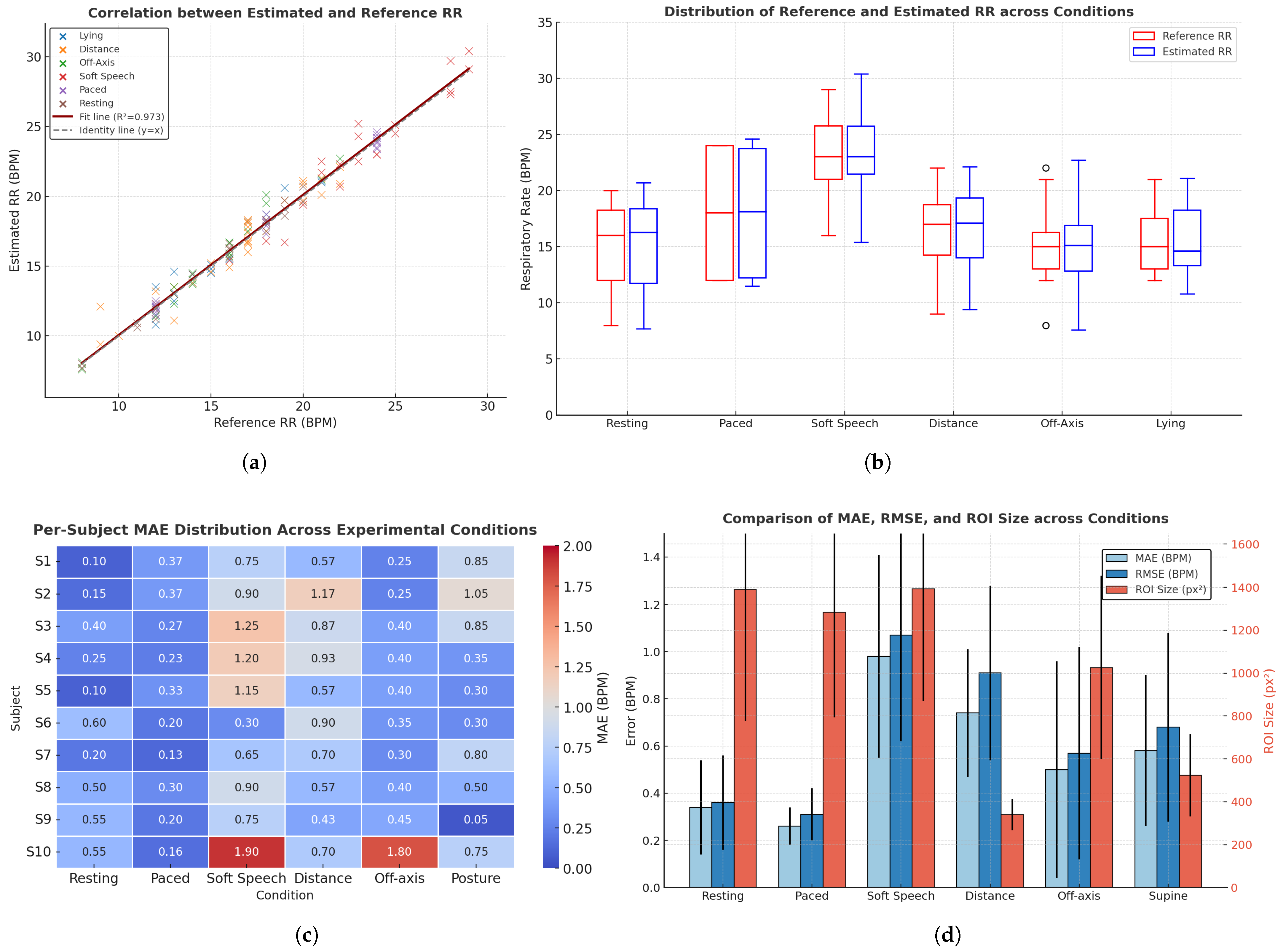

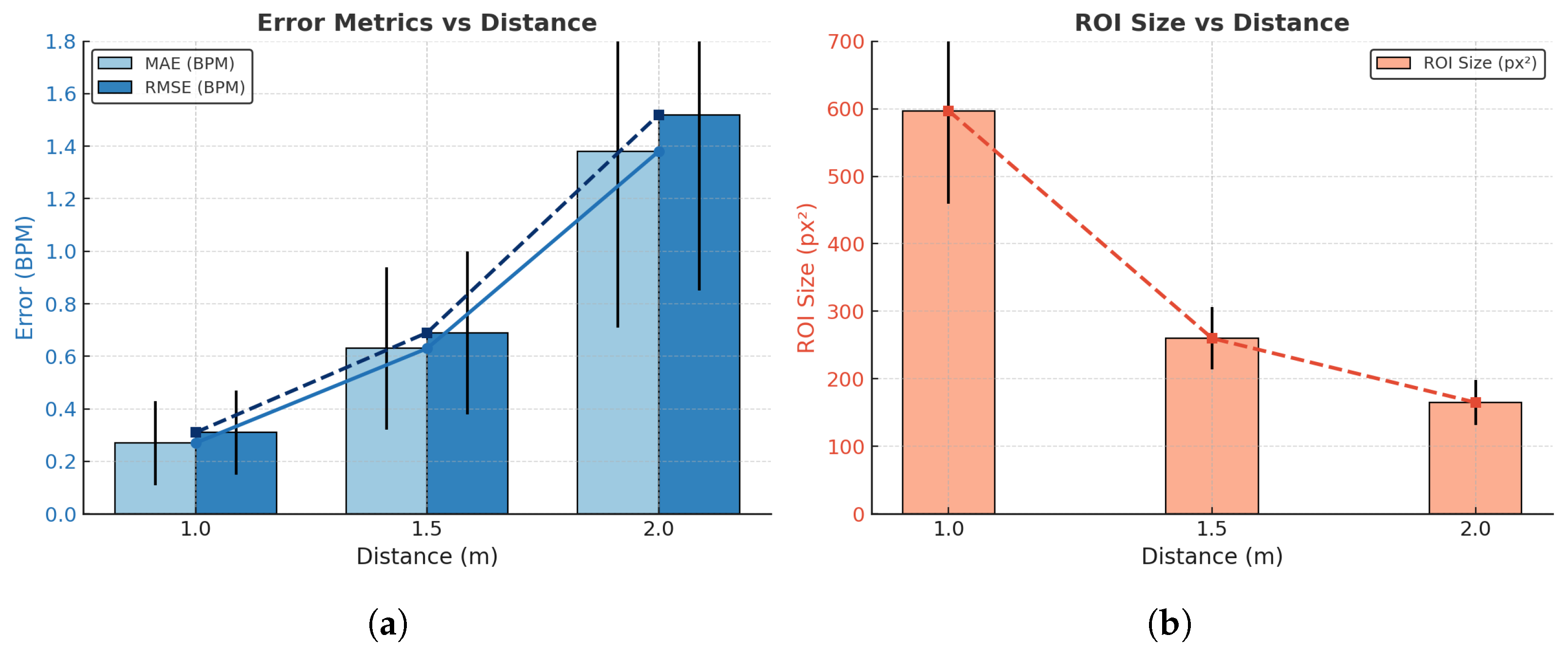

4.4. Respiratory Rate Estimation Accuracy

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| YOLO | You Only Look Once |

| ROI | Region of Interest |

| IIR | Infinite Impulse Response |

| IBI | Inter-Breath Interval |

| Respiratory Rate | |

| 3D-CNNs | Three-Dimensional Convolutional Neural Networks |

| SSD | Single Shot MultiBox Detector |

| YUV | Luminance (Y) and chrominance components (U: blue-difference, V: red-difference) |

| C2f | Cross Stage Partial with 2 convolutions and fusion |

| BPM | Breaths Per Minute |

| GUI | Graphical User Interface |

| GPU | Graphics Processing Unit |

| CPU | Central Processing Unit |

| DFL | Distribution Focal Loss |

| PR | Precision–Recall |

| BiLSTM | Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory |

| CZT | Chirp Z-Transform |

| RQI | Region Quality Index |

| FFT | Fast Fourier Transform |

| AMDF | Average Magnitude Difference Function |

| NICU | Neonatal Intensive Care Unit |

| FPS | Frames Per Second |

| RGB | Red, Green, Blue color space |

| MAD | Median Absolute Deviation |

| EMA | Exponential Moving Average |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| SNR | signal-to-noise ratio |

| p05 | 5th percentile |

| p95 | 95th percentile |

| MSB | most significant byte |

| LSB | least significant byte |

| Std Dev | Standard deviation |

| COPD | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

References

- Drummond, G.; Fischer, D.; Arvind, D. Current clinical methods of measurement of respiratory rate give imprecise values. ERJ Open Res. 2020, 6, 00023–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, M.J. Breathing pattern analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2005, 18, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashe, W.B.; McNamara, B.D.; Patel, S.M.; Shanno, J.N.; Innis, S.E.; Hochheimer, C.J.; Barros, A.J.; Williams, R.D.; Ratcliffe, S.J.; Moorman, J.; et al. Kinematic signature of high risk labored breathing revealed by novel signal analysis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas, E.; López-Baamonde, M.; Sanahuja, J.; del Rio, E.; Ramis, T.; Recasens, A.; López, A.; Arias, M.; Kampakis, S.; Lauteslager, T.; et al. Early detection of deterioration in COVID-19 patients by continuous ward respiratory rate monitoring: A pilot prospective cohort study. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1243050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, G.; Peelen, R.; Gilissen, V.; Koning, M.; Harten, W.; Doggen, C. Detecting patient deterioration early using continuous heart rate and respiratory rate measurements in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. J. Med. Syst. 2023, 47, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.; Dandu, H.; Parchani, G.; Chokalingam, K.; Kadambi, P.; Mishra, R.; Jahan, A.; Teboul, J.; Latour, J. Early detection of deteriorating patients in general wards through continuous contactless vital signs monitoring. Front. Med. Technol. 2024, 6, 1436034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCartan, T.; Worrall, A.; Conluain, R.; Alaya, F.; Mulvey, C.; MacHale, E.; Brennan, V.; Lombard, L.; Walsh, J.; Murray, M.; et al. The effectiveness of continuous respiratory rate monitoring in predicting hypoxic and pyrexic events: A retrospective cohort study. Physiol. Meas. 2021, 42, 065005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryynänen, O.P.; Kivelä, S.; Honkanen, R.; Laippala, P. Falls and lying helpless in the elderly. Z. Gerontol. 1992, 25, 278–282. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fleming, J.; Brayne, C. Inability to get up after falling, subsequent time on floor, and summoning help: Prospective cohort study in people over 90. BMJ 2008, 337, a2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubitza, J.; Schneider, I.T.; Reuschenbach, B. Concept of the term long lie: A scoping review. Eur. Rev. Aging Phys. Act. 2023, 20, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaroni, C.; Nicolò, A.; Presti, D.; Sacchetti, M.; Silvestri, S.; Schena, E. Contact-Based Methods for Measuring Respiratory Rate. Sensors 2019, 19, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costanzo, I.; Sen, D.; Rhein, L.; Guler, U. Respiratory Monitoring: Current State of the Art and Future Roads. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 15, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Allen, J.; Zheng, D.; Chen, F. Recent development of respiratory rate measurement technologies. Physiol. Meas. 2019, 40, 07TR01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitazkova, D.; Foltan, E.; Kosnacova, H.; Micjan, M.; Donoval, M.; Kuzma, A.; Kopani, M.; Vavrinsky, E. Advances in Respiratory Monitoring: A Comprehensive Review of Wearable and Remote Technologies. Biosensors 2024, 14, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.; Sh; hi, M.M.H.; Li, Y.; Inan, O.T.; Zhang, Y. The Delineation of Fiducial Points for Non-Contact Radar Seismocardiogram Signals Without Concurrent ECG. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2021, 25, 1031–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalaja, A.A.; Kavitha, M. Contactless face video based vital signs detection framework for continuous health monitoring using feature optimization and hybrid neural network. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2024, 121, 1190–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chian, D.-M.; Wen, C.-K.; Wang, C.-J.; Hsu, M.-H.; Wang, F.-K. Vital Signs Identification System With Doppler Radars and Thermal Camera. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2022, 16, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negishi, T.; Abe, S.; Matsui, T.; Liu, H.; Kurosawa, M.; Kirimoto, T.; Sun, G. Contactless Vital Signs Measurement System Using RGB-Thermal Image Sensors and Its Clinical Screening Test on Patients with Seasonal Influenza. Sensors 2020, 20, 2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, F.; Pura, F.; Greco, A.; Piga, D.; Merla, A.; Forgione, M. Contactless Estimation of Respiratory Frequency Using 3D-CNN on Thermal Images. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2025, 29, 7387–7395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Wang, G.; Xie, Y.; Tu, J.; Sun, W.; Kong, X.; Guo, X.; Zhang, D. Separated Respiratory Phases for In Vivo Ultrasonic Thermal Strain Imaging. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2022, 69, 1219–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, R.; van Meulen, F.; Overeem, S.; Zinger, S.; Stuijk, S. Thermal Cameras for Continuous and Contactless Respiration Monitoring. Sensors 2024, 24, 8118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurya, L.; Zwiggelaar, R.; Chawla, D.; Mahapatra, P. Non-contact respiratory rate monitoring using thermal and visible imaging: A pilot study on neonates. J. Clin. Monit. Comput. 2022, 37, 815–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakkaew, P.; Onoye, T. Non-Contact Respiration Monitoring and Body Movements Detection for Sleep Using Thermal Imaging. Sensors 2020, 20, 6307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtado, D.; Abusleme, A.; Chávez, J.A.P. Non-invasive continuous respiratory monitoring using temperature-based sensors. J. Clin. Monit. Comput. 2019, 34, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jisha, S.; Jayanthi, T. Non-Contact methods for assessment of respiratory parameters. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Innovations in Engineering and Technology (ICIET), Muvattupuzha, India, 13–14 July 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozafari, M.; Law, A.J.; Goubran, R.A.; Green, J.R. Respiratory Rate Estimation from Thermal Video Data Using Spatio-Temporal Deep Learning. Sensors 2024, 24, 6386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Oh, K.; Kwon, O.; Kwon, J.; Kim, J.; Yoo, S. Non-Contact Respiration Rate Measurement From Thermal Images Using Multi-Resolution Window and Phase-Sensitive Processing. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 112706–112718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Khan, T.M.; Song, Y.; Meijering, E. Edge deep learning in computer vision and medical diagnostics: A comprehensive survey. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rancea, A.; Anghel, I.; Cioara, T. Edge computing in healthcare: Innovations, opportunities, and challenges. Future Internet 2024, 16, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankaj, A.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, M.; Komaragiri, R. Edge-Based Computation of Super-Resolution Superlet Spectrograms for Real-Time Estimation of Heart Rate Using an IoMT-Based Reference-Signal-Less PPG Sensor. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 8647–8657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.H.; Rajaram, B. Design and Simulation of an Edge Compute Architecture for IoT-Based Clinical Decision Support System. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 45456–45474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanungo, P. Edge computing in healthcare: Real-time patient monitoring systems. World J. Adv. Eng. Technol. Sci. 2025, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalina, L.; Doru, A.; Călin, C. The use of thermographic techniques and analysis of thermal images to monitor the respiratory rate of premature new-borns. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2021, 25, 100926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alva, R.; Talasila, V.; Tv, S.; Umar, S.A.R. Estimation of Respiratory Rate Using Thermography. In Proceedings of the 2024 5th International Conference on Circuits, Control, Communication and Computing (I4C), Bangalore, India, 4–5 October 2024; pp. 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luca, C.; Andritoi, D.; Corciova, C. Monitoring the Respiratory Rate in the Premature Newborn by Analyzing Thermal Images. Nov. Perspect. Eng. Res. 2022, 5, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, S.; Liang, H.-R.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Z. Non-contact measurement of human respiration using an infrared thermal camera and the deep learning method. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2022, 33, 075202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazri, Z.; Zhu, Q.; Chen, M.; Wu, M.; Wang, Q. Detecting Essential Landmarks Directly in Thermal Images for Remote Body Temperature and Respiratory Rate Measurement With a Two-Phase System. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 39080–39094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Zhai, G.; Li, D.; Fan, Y.; Duan, H.; Zhu, W.; Yang, X. Combination of near-infrared and thermal imaging techniques for the remote and simultaneous measurements of breathing and heart rates under sleep situation. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0190466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, N.; Rumiński, J. Respiratory Rate Estimation Based on Detected Mask Area in Thermal Images. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 6042–6051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.; Kwon, O.; Oh, K.; Kim, J.; Yoo, S. Breathing-Associated Facial Region Segmentation for Thermal Camera-Based Indirect Breathing Monitoring. IEEE J. Transl. Eng. Health Med. 2023, 11, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.; Julier, S.; Marquardt, N.; Bianchi-Berthouze, N. Robust tracking of respiratory rate in high-dynamic range scenes using mobile thermal imaging. Biomed. Opt. Express 2017, 8, 4480–4503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.-Y.; Lai, J. HHT-based remote respiratory rate estimation in thermal images. In Proceedings of the 2017 18th IEEE/ACIS International Conference on Software Engineering, Artificial Intelligence, Networking and Parallel/Distributed Computing (SNPD), Kanazawa, Japan, 26–28 June 2017; pp. 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwaśniewska, A.; Szankin, M.; Rumiński, J.; Kaczmarek, M. Evaluating Accuracy of Respiratory Rate Estimation from Super Resolved Thermal Imagery. In Proceedings of the 2019 41st Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Berlin, Germany, 23–27 July 2019; pp. 2744–2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, C.; Innocenti, L.; Schena, E.; Sacchetti, M.; Nicolò, A.; Massaroni, C. A Signal Quality Index for Improving the Estimation of Breath-by-Breath Respiratory Rate During Sport and Exercise. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 31250–31258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabz, M.; MacLean, J.; Martin, A.R.; Rouhani, H. Characterization of Wearable Respiratory Sensors for Breathing Parameter Measurements. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 32283–32290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Liu, R.; Li, J.; Song, R.; Liu, Y.; Chen, X. Motion-Robust Respiratory Rate Estimation From Camera Videos via Fusing Pixel Movement and Pixel Intensity Information. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 4008611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; den Brinker, A.C. Algorithmic insights of camera-based respiratory motion extraction. Physiol. Meas. 2022, 43, 075004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romano, C.; Schena, E.; Silvestri, S.; Massaroni, C. Non-Contact Respiratory Monitoring Using an RGB Camera for Real-World Applications. Sensors 2021, 21, 5126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Wu, F.; Su, H.; Huang, P.; Qixuan, Y. Improvement of SAM2 algorithm based on Kalman filtering for long-term video object segmentation. Sensors 2025, 25, 4199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, I.C.; Magpantay, P.; Rosales, M.D.; Hizon, J.R.E. Review of Kalman filters in multiple object tracking algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Omni-layer Intelligent Systems (COINS), London, UK, 29–31 July 2024; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallioinen, N.; Hill, A.; Christofidis, M.; Horswill, M.; Watson, M. Quantitative systematic review: Sources of inaccuracy in manually measured adult respiratory rate data. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020, 77, 98–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, Y.; Gu, Y.; Nakada, T.; Abe, R.; Nakaguchi, T. Estimation of Respiratory Rate from Thermography Using Respiratory Likelihood Index. Sensors 2021, 21, 4406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.B.; Yu, X.; Goos, T.; Reiss, I.; Orlikowsky, T.; Heimann, K.; Venema, B.; Blazek, V.; Leonhardt, S.; Teichmann, D. Noncontact Monitoring of Respiratory Rate in Newborn Infants Using Thermal Imaging. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 66, 1105–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakai, K.; Kurosawa, M.; Kirimoto, T.; Matsui, T.; Abe, S.; Suzuki, S.; Sun, G. Performance enhancement of thermal image analysis for noncontact cardiopulmonary signal extraction. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2024, 138, 105244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Yang, H.; Shi, J.; Hu, A.; Xu, J.; Zhuge, X.; Miao, J. Noncontact Breathing Pattern Monitoring Using a 120 GHz Dual Radar System with Motion Interference Suppression. Biosensors 2025, 15, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husaini, M.; Kamarudin, L.; Zakaria, A.; Kamarudin, I.K.; Ibrahim, M.; Nishizaki, H.; Toyoura, M.; Mao, X. Non-Contact Breathing Monitoring Using Sleep Breathing Detection Algorithm (SBDA) Based on UWB Radar Sensors. Sensors 2022, 22, 5249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Analia, R.; Forster, A.; Xie, S.-Q.; Zhang, Z. Privacy-Preserving Approach for Early Detection of Long-Lie Incidents: A Pilot Study with Healthy Subjects. Sensors 2025, 25, 3836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| (A) Runtime Breakdown per Component | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component | Mean (ms) | p95 (ms) | Percentage | ||

| Total Frame Time | 65.20 | 85.30 | 100% | ||

| YOLO Detection | 35.50 | 42.10 | 54.5% | ||

| Thermal Capture | 15.00 | 30.00 | 23.3% | ||

| Graph/GUI Update | 10.80 | 14.20 | 16.6% | ||

| Signal Processing | 3.50 | 3.80 | 5.4% | ||

| Temperature Extraction | 2.80 | 3.50 | 4.3% | ||

| Kalman Tracking | 1.20 | 0.80 | 1.8% | ||

| IBI Calculation | 0.50 | 0.80 | 0.8% | ||

| (B) System Resource Utilization | (C) End-to-End Throughput Statistics | ||||

| Metric | Mean | p05 | p95 | Metric | Value (FPS) |

| CPU Usage | 42.5% | 35.2% | 58.3% | Mean FPS | 22.5 |

| GPU Usage | 68.2% | 67.5% | 80.3% | Min FPS | 18.2 |

| Memory Usage | 850.3 MB | 820.5 MB | 890.2 MB | Max FPS | 28.8 |

| p50 | 24.5 | ||||

| p95 | 24.5 | ||||

| Std Dev | 1.8 | ||||

| Condition Set | Blocks per Subject | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resting (spontaneous) | 60 s | Seated, natural nasal breathing, mouth closed | |

| Paced breathing (metronome) | 60 s | Seated; guided at 12, 18, 24 BPM (randomized order); metronome target logged as auxiliary reference | |

| Robustness (soft speech) | 60 s | Seated; counting aloud to emulate mild articulatory motion | |

| Distance (stood) | 60 s | Spontaneous breathing at 1.0, 1.5, and 2.0 m; camera height/pitch held constant | |

| Off-axis yaw (seated) | 60 s | Spontaneous breathing at yaw; neutral pitch/roll instructed | |

| Posture (supine) | 60 s | Spontaneous breathing in supine facing camera; camera pitched downward |

| Subj. | Resting | Paced | Soft Speech | Distance | Off-Axis | Posture | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAE | RMSE | px2 | MAE | RMSE | px2 | MAE | RMSE | px2 | MAE | RMSE | px2 | MAE | RMSE | px2 | MAE | RMSE | px2 | |

| S1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 2254 | 0.37 | 0.4 | 1847 | 0.75 | 0.99 | 1779 | 0.57 | 0.74 | 364 | 0.25 | 0.35 | 1216 | 0.85 | 1.33 | 808 |

| S2 | 0.15 | 0.21 | 1742 | 0.37 | 0.46 | 2045 | 0.9 | 0.98 | 1888 | 1.17 | 1.81 | 493 | 0.25 | 0.29 | 1420 | 1.05 | 1.18 | 769 |

| S3 | 0.4 | 0.41 | 809 | 0.27 | 0.32 | 785 | 1.25 | 1.57 | 709 | 0.87 | 1.14 | 286 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 831.5 | 0.85 | 0.91 | 544 |

| S4 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 1390 | 0.23 | 0.35 | 1065 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1528 | 0.93 | 1.02 | 367 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 831 | 0.35 | 0.38 | 500 |

| S5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1401 | 0.33 | 0.42 | 1359 | 1.15 | 1.16 | 1984 | 0.57 | 0.70 | 273 | 0.4 | 0.41 | 1164 | 0.3 | 0.36 | 341 |

| S6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 2359 | 0.2 | 0.22 | 1738 | 0.3 | 0.36 | 1705 | 0.90 | 0.95 | 329 | 0.35 | 0.49 | 1897 | 0.3 | 0.31 | 597 |

| S7 | 0.2 | 0.28 | 1102 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 846 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 861 | 0.70 | 0.79 | 261 | 0.3 | 0.42 | 777 | 0.8 | 1.06 | 301 |

| S8 | 0.5 | 0.59 | 713 | 0.3 | 0.34 | 624 | 0.9 | 0.95 | 731 | 0.57 | 0.68 | 360 | 0.4 | 0.41 | 542 | 0.5 | 0.54 | 427 |

| S9 | 0.55 | 0.57 | 1081 | 0.2 | 0.29 | 975 | 0.75 | 0.79 | 1046 | 0.43 | 0.55 | 317 | 0.45 | 0.51 | 935 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 496 |

| S10 | 0.55 | 0.57 | 1055 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 1559 | 1.9 | 1.94 | 1696 | 0.70 | 0.72 | 352 | 1.8 | 1.82 | 644 | 0.75 | 0.87 | 446 |

| Condition | MAE (BPM) | RMSE (BPM) | ROI (px2) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proposed | Peak | FFT | Proposed | Peak | FFT | ||

| Resting (Spontaneous) | 0.34 ± 0.20 | 10.07 ± 5.48 | 1.51 ± 1.30 | 0.36 ± 0.20 | 11.24 ± 5.48 | 2.10 ± 1.30 | 1390 ± 614 |

| Paced Breathing (Metronome) | 0.26 ± 0.08 | 0.93 ± 0.65 | 5.11 ± 5.90 | 0.31 ± 0.11 | 1.12 ± 0.65 | 7.58 ± 5.90 | 1284 ± 491 |

| Robustness (Soft Speech) | 0.98 ± 0.43 | 4.39 ± 2.99 | 3.70 ± 3.92 | 1.07 ± 0.45 | 5.22 ± 2.99 | 5.24 ± 3.92 | 1393 ± 522 |

| Distance (1.0–2.0 m) | 0.74 ± 0.27 | 8.33 ± 5.19 | 5.76 ± 5.77 | 0.91 ± 0.37 | 9.68 ± 5.19 | 7.94 ± 5.78 | 340 ± 206 |

| Off-axis Yaw () | 0.50 ± 0.46 | 10.72 ± 3.80 | 2.31 ± 3.79 | 0.57 ± 0.45 | 11.30 ± 3.80 | 3.78 ± 3.79 | 1026 ± 428 |

| Posture (Supine) | 0.58 ± 0.32 | 6.31 ± 4.04 | 3.47 ± 3.94 | 0.68 ± 0.40 | 7.38 ± 4.04 | 5.10 ± 3.94 | 523 ± 192 |

| Overall | 0.57 ± 0.36 | 6.79 ± 3.86 | 3.64 ± 3.88 | 0.64 ± 0.42 | 7.58 ± 3.86 | 5.48 ± 3.88 | – |

| Distance (m) | MAE (BPM) | RMSE (BPM) | ROI Size (px2) | Observation * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.0 | 0.27 ± 0.16 | 0.31 ± 0.16 | 597 ± 138 | Clear nostril region, distinct thermal contrast |

| 1.5 | 0.63 ± 0.31 | 0.69 ± 0.31 | 260 ± 46 | Reduced contrast, smaller ROI |

| 2.0 | 1.38 ± 0.67 | 1.52 ± 0.67 | 165 ± 33 | Weak contrast, partial pixel loss |

| Study | Subjects & Conditions | Camera Spec & Setup (ROI + Method) | Accuracy (BPM) | Real-Time | Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ours | 10 adults; six 60-s sets (resting, paced 12/18/24 BPM, soft speech, distance 1–2 m, yaw ± 30°, posture supine) | TOPDON TC001 (256 × 192); RO: Ithermal YOLOv8n (even frames, s = 10)+ Kalman tracking on skipped frames; band-pass 0.08–0.7 Hz; adaptive MAD–hysteresis phase detection + IBI validation | MAE (mean ); RMSE (mean ) | Yes | Thermal-based YOLO detector with Kalman tracking; adaptive MAD–hysteresis phase and IBI validation |

| Gioia et al. [19] | 30 adults; 5-min tasks (rest, Stroop, emotion); 9–30 | FLIR T640 (640 × 480); ROI: upper lip/nose (manual); 3D-CNN end-to-end regression | (no MAE/RMSE) | No | Feasibility of end-to-end deep learning directly from thermal video |

| Mozafari et al. [26] | 22 adults; sitting/standing × mask/no-mask, 90 s | FLIR T650sc (640×480); ROI: full face (DeTr); 3D-CNN + BiLSTM with correlation loss | MAE | Yes | Deep learning robust to mask & posture; real-time feasibility focus |

| Maurya et al. [22] | 14 adults (rest, talking, variable); 8 neonates (NICU) | FLIR-E60 (320 × 240) + Logitech C922 RGB (960 × 720); ROI: nose–mouth (from RGB mapped to thermal); Hampel+MA+BP filtering; CZT spectral analysis | Adults: MAE 0.10–1.8; Neonates: MAE ≈ 1.5 | No | Cross-modality ROI mapping; validated adults & neonates |

| Takahashi et al. [52] | 7 adults; paced 15–30 BPM | FLIR Boson 320 (320 × 256); ROI: face subregions (scored by RQI); YOLOv3 + RQI; FFT on best region | MAE 0.66; LoA ± 2 BPM | No | ROI quality index (RQI) for automated subregion selection |

| Pereira et al. [53] | 12 adults (rest, pathological); 8 neonates (NICU) | InfraTec VarioCAM HD (1024 × 768); ROI: full face (multi-grid, black-box); adaptive spectral analysis (autocorr, AMDF, peak detection) | RMSE 0.31 (rest), 3.27 (varied), 4.15 (neonates) | No | First NICU validation; black-box ROI without anatomical landmark |

| Nakai et al. [54] | 11 healthy adults; seated at 1 m distance (lab environment) | FLIR A315 (320 × 240, 60 fps); manually defined nose & shoulder ROIs; dual-signal extraction (thermal variation + shoulder motion); band-pass filtering + autocorrelation/FFT for estimation | vs. belt; MAE ; RMSE | No | Dual-ROI thermal approach combining nasal temperature and shoulder motion |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Analia, R.; Forster, A.; Xie, S.-Q.; Zhang, Z. Adaptive Thermal Imaging Signal Analysis for Real-Time Non-Invasive Respiratory Rate Monitoring. Sensors 2026, 26, 278. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010278

Analia R, Forster A, Xie S-Q, Zhang Z. Adaptive Thermal Imaging Signal Analysis for Real-Time Non-Invasive Respiratory Rate Monitoring. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):278. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010278

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnalia, Riska, Anne Forster, Sheng-Quan Xie, and Zhiqiang Zhang. 2026. "Adaptive Thermal Imaging Signal Analysis for Real-Time Non-Invasive Respiratory Rate Monitoring" Sensors 26, no. 1: 278. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010278

APA StyleAnalia, R., Forster, A., Xie, S.-Q., & Zhang, Z. (2026). Adaptive Thermal Imaging Signal Analysis for Real-Time Non-Invasive Respiratory Rate Monitoring. Sensors, 26(1), 278. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010278