Semi-Supervised Seven-Segment LED Display Recognition with an Integrated Data-Acquisition Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

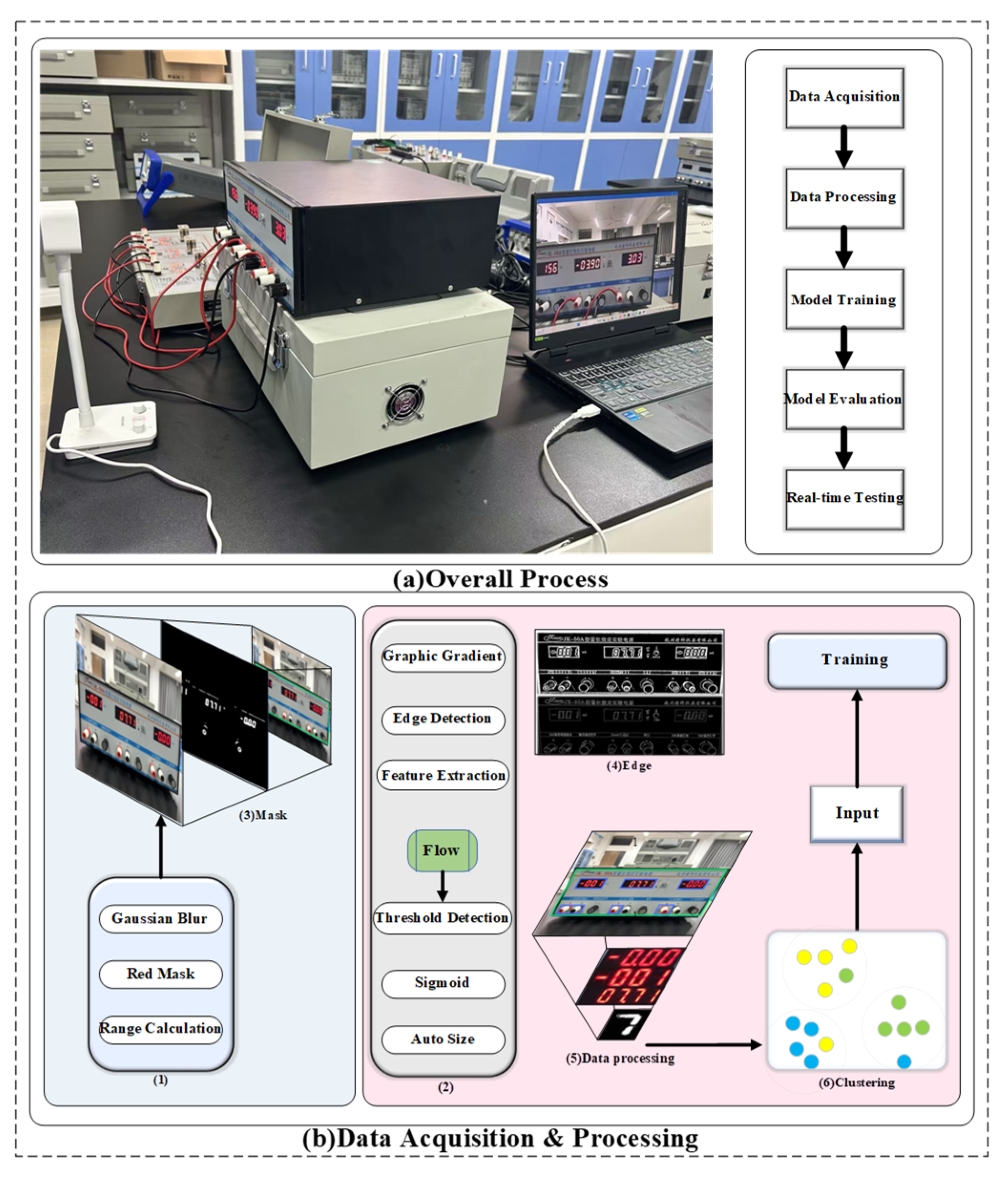

2. Materials and Methods

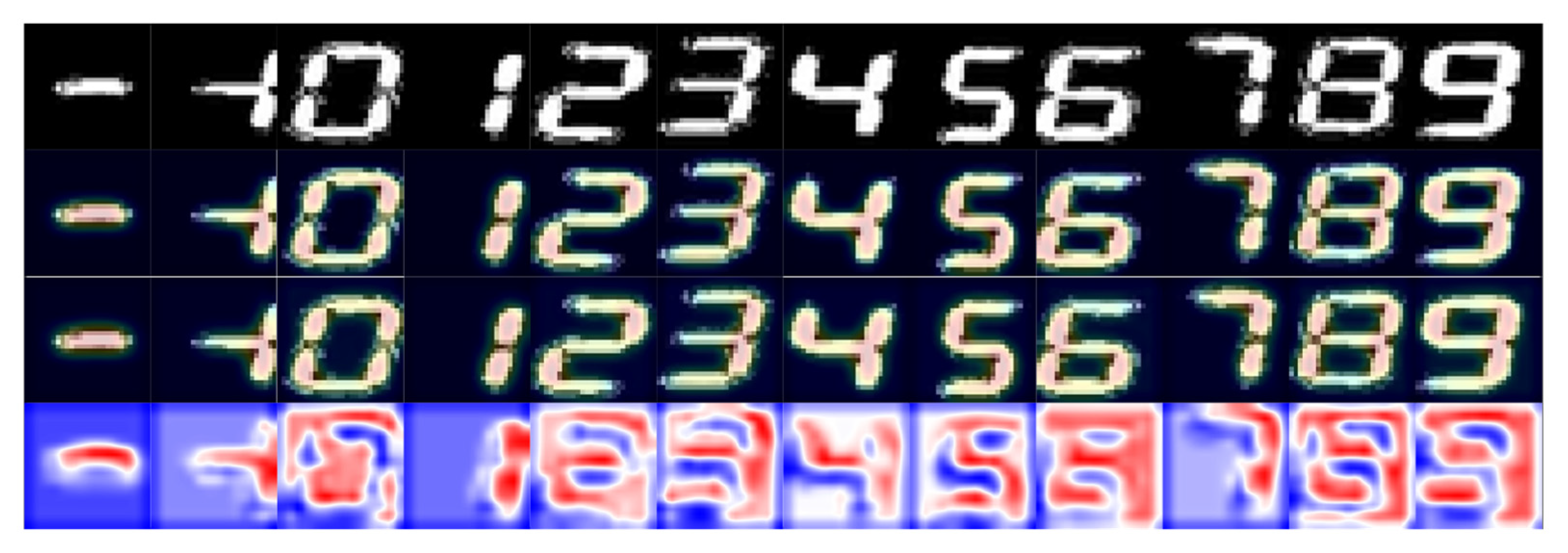

2.1. Image Preprocessing

2.2. Screening Model and Data Generalization

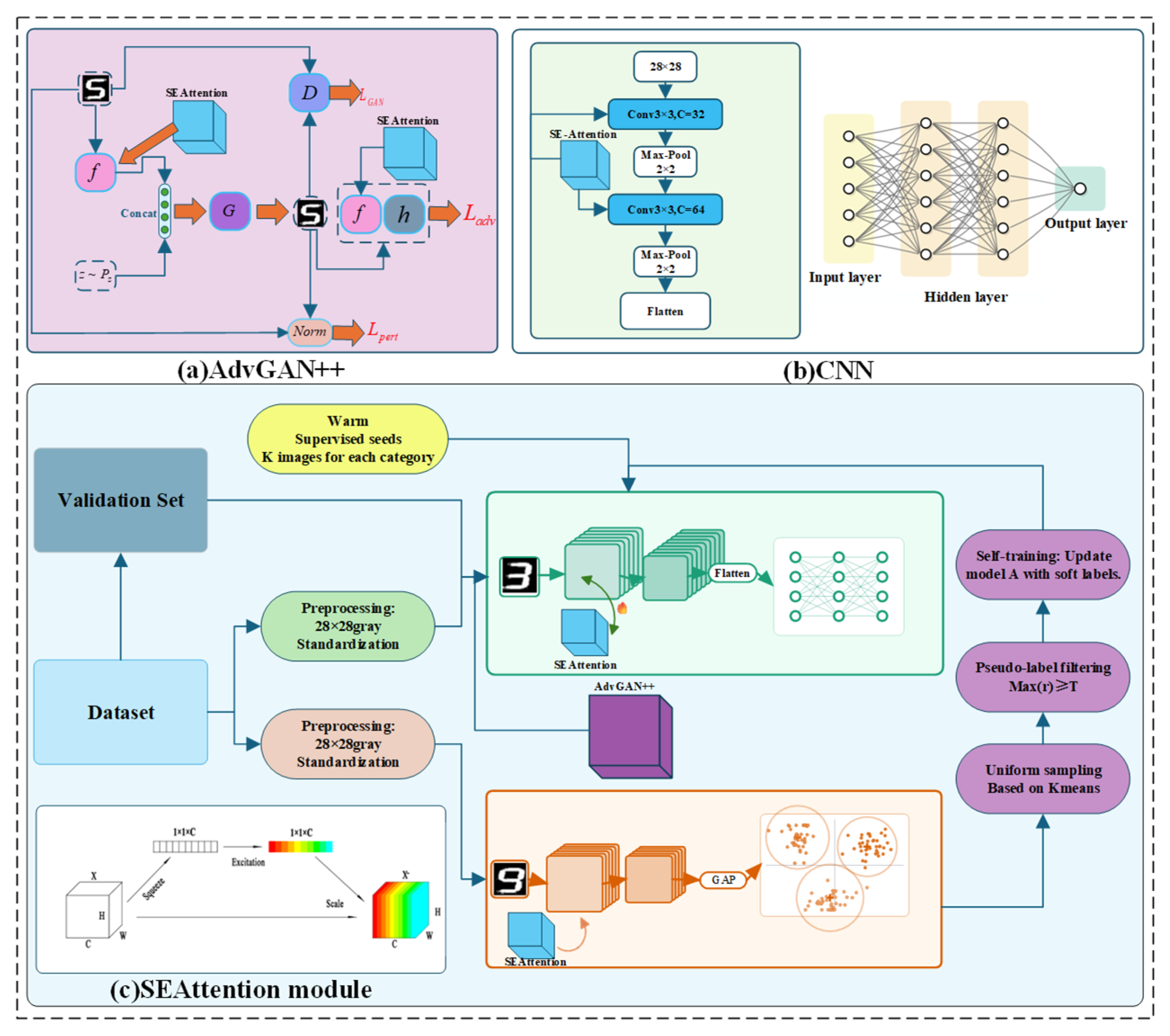

2.3. The Framework of the Semi-Supervised Model

2.4. CNN-SE Model

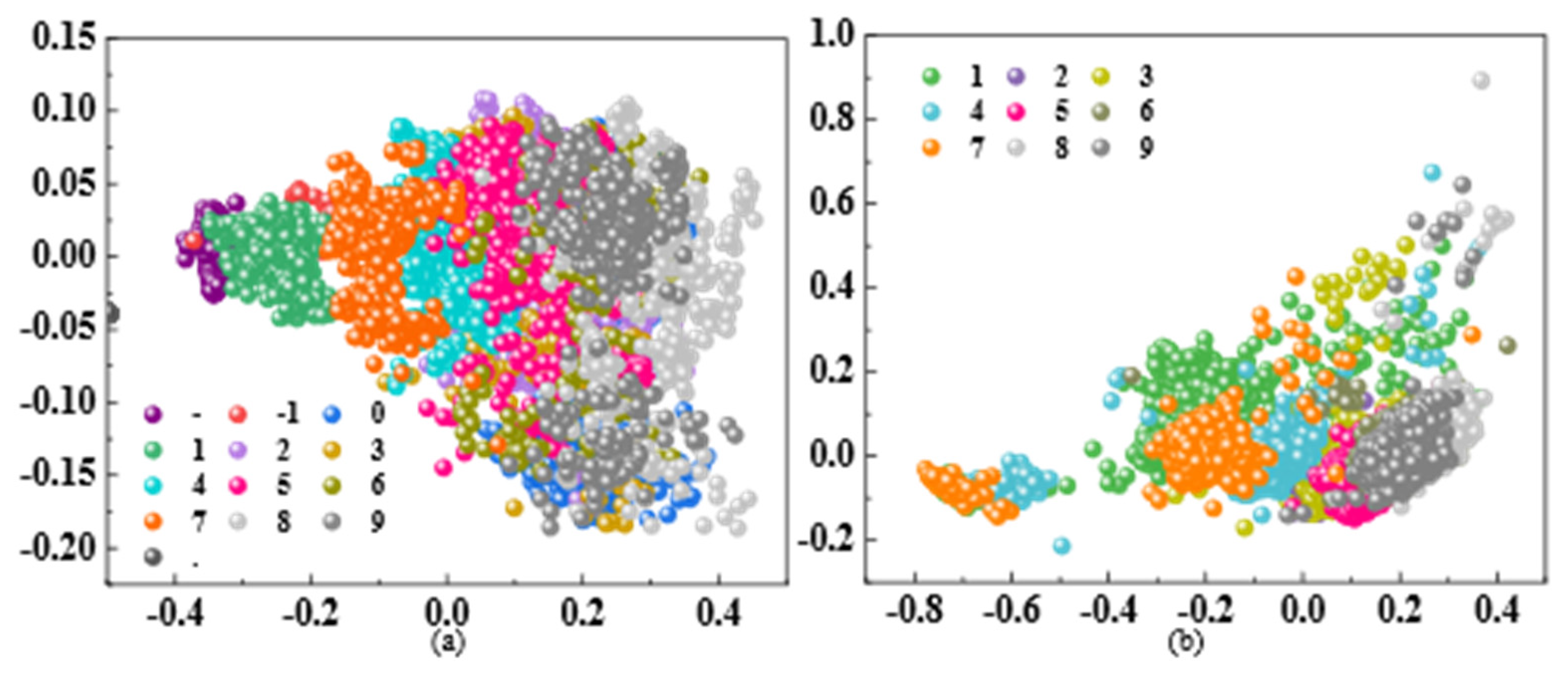

2.5. Clustering Model

2.6. Adversarial Training Module

3. Results

3.1. Datasets

3.2. Implementation Details

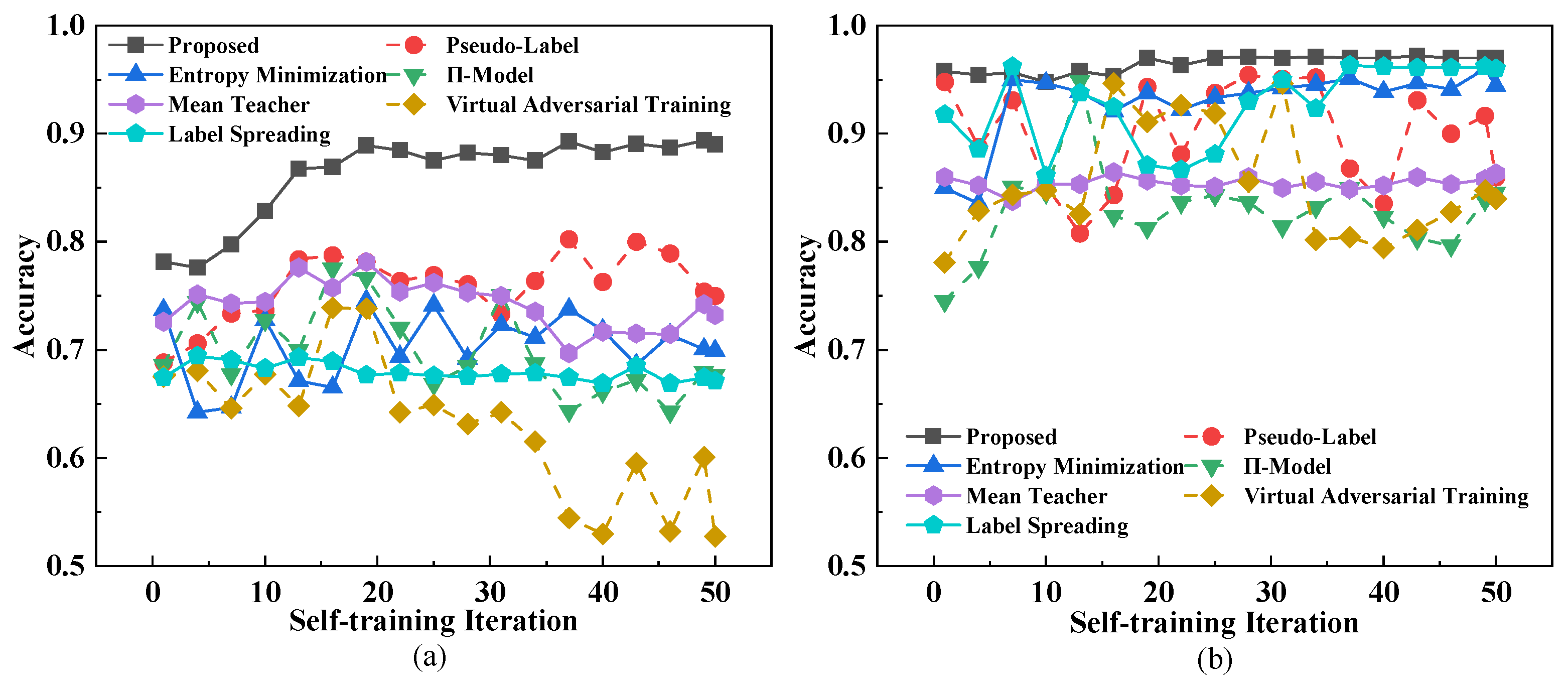

3.3. Comparative Experiment

3.3.1. The Analysis of Accuracy

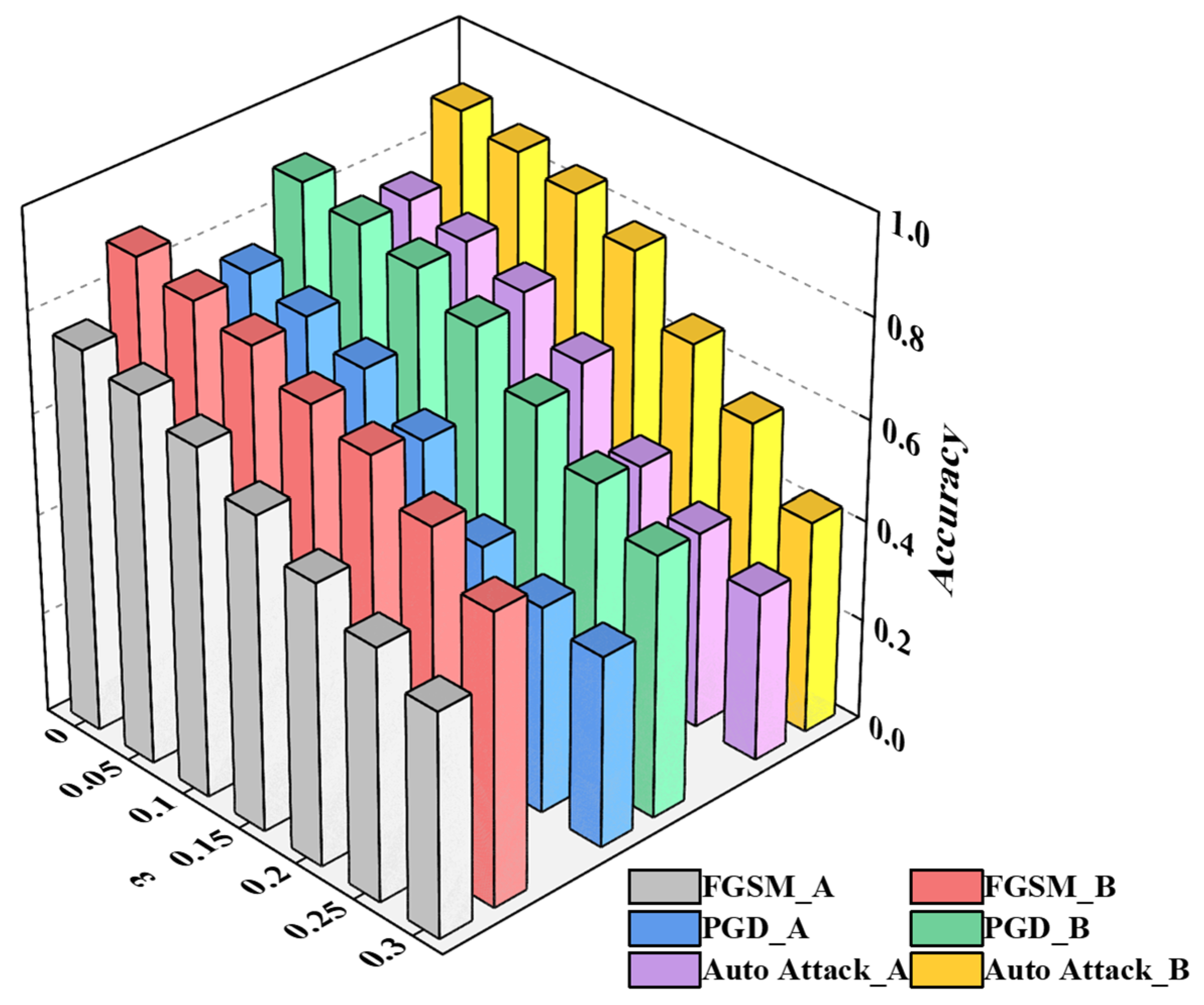

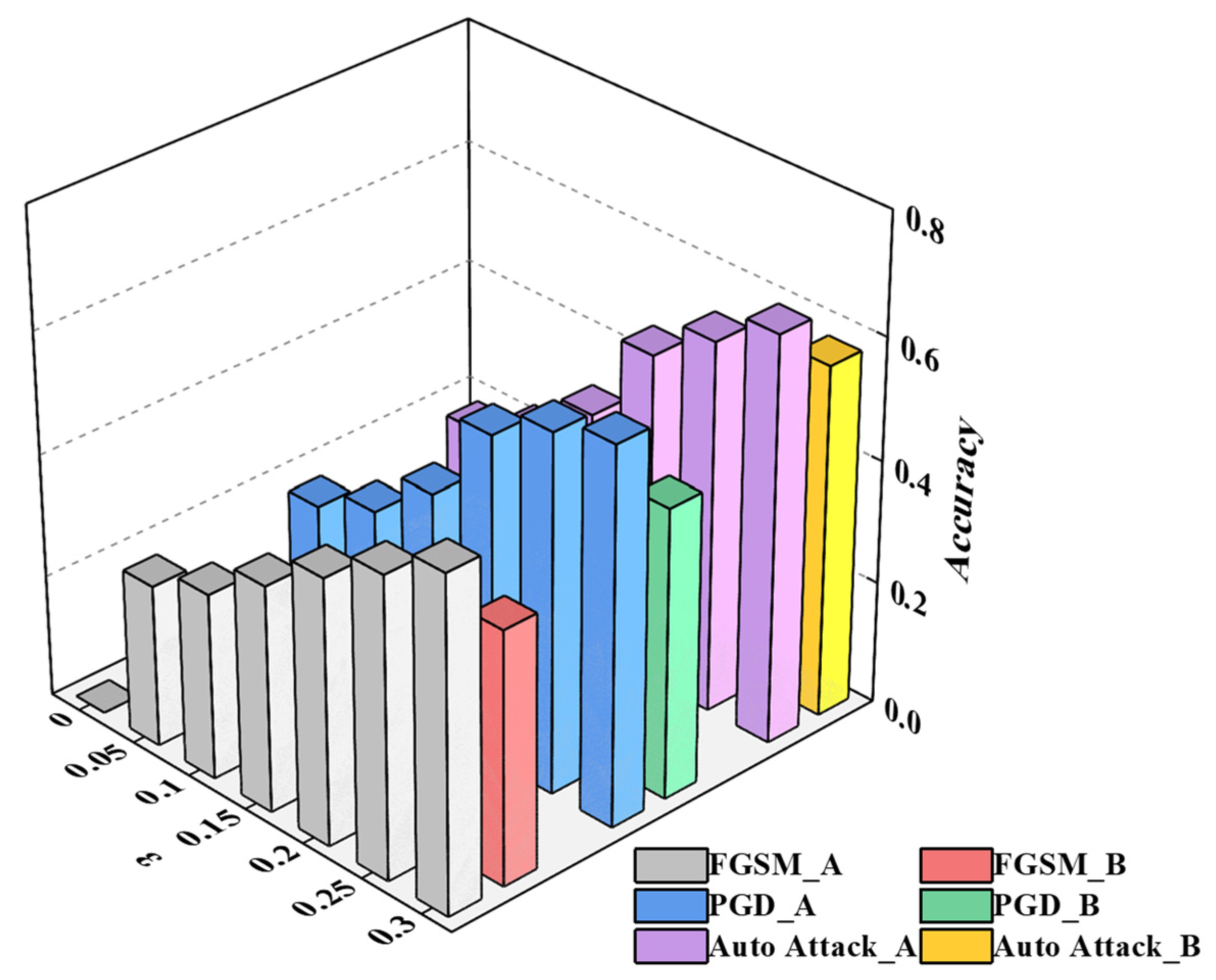

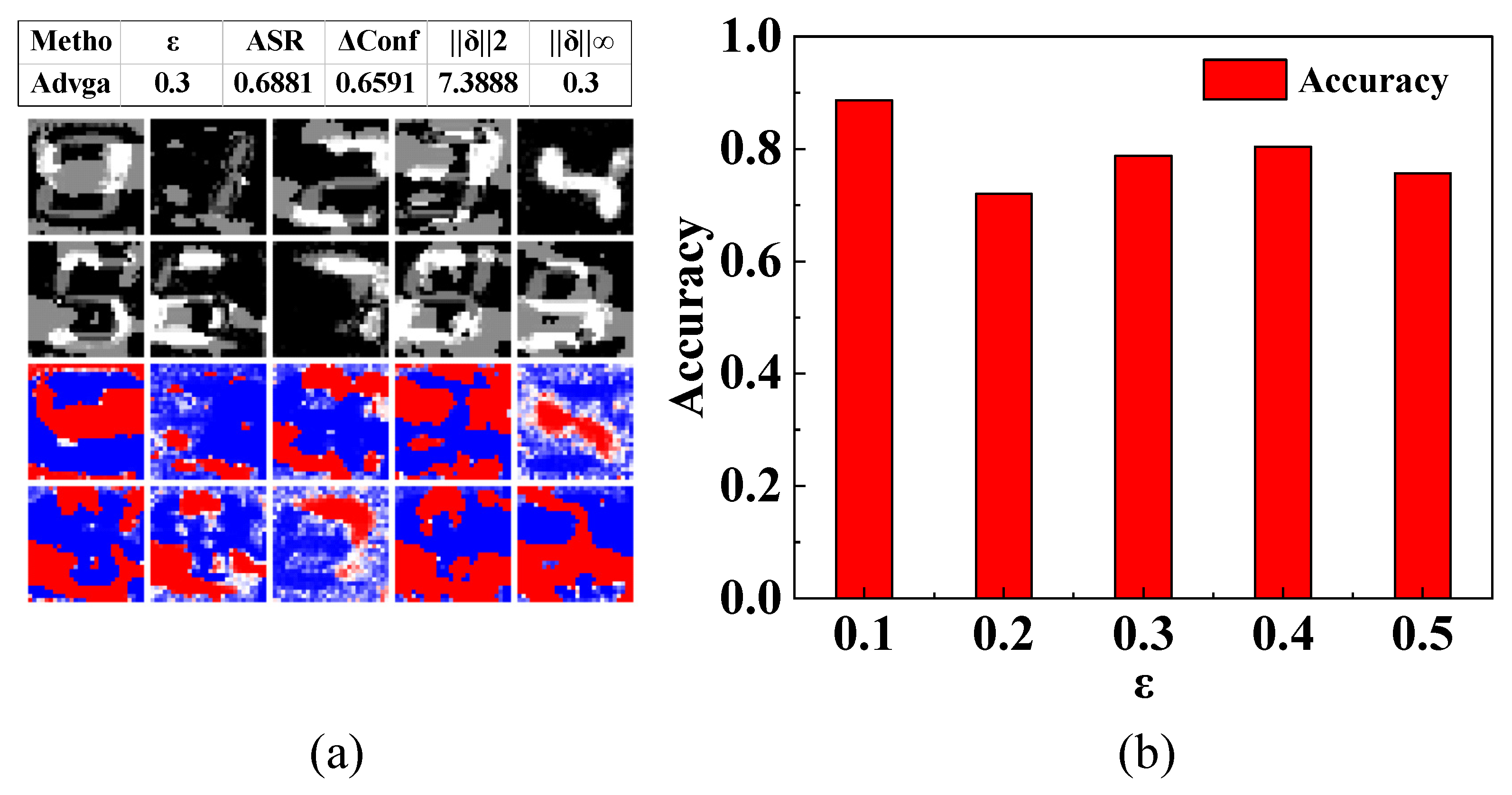

3.3.2. The Analysis of Robustness

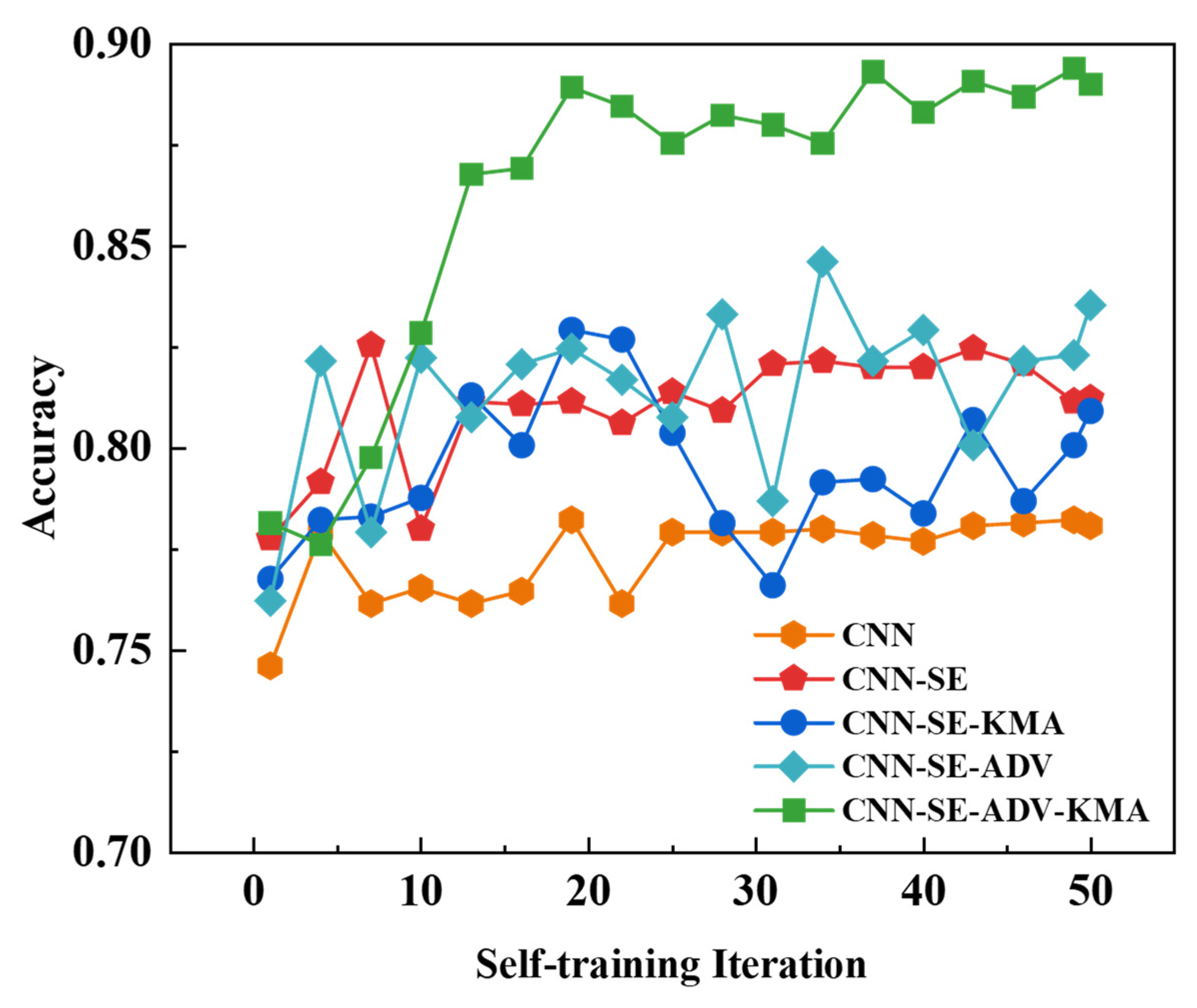

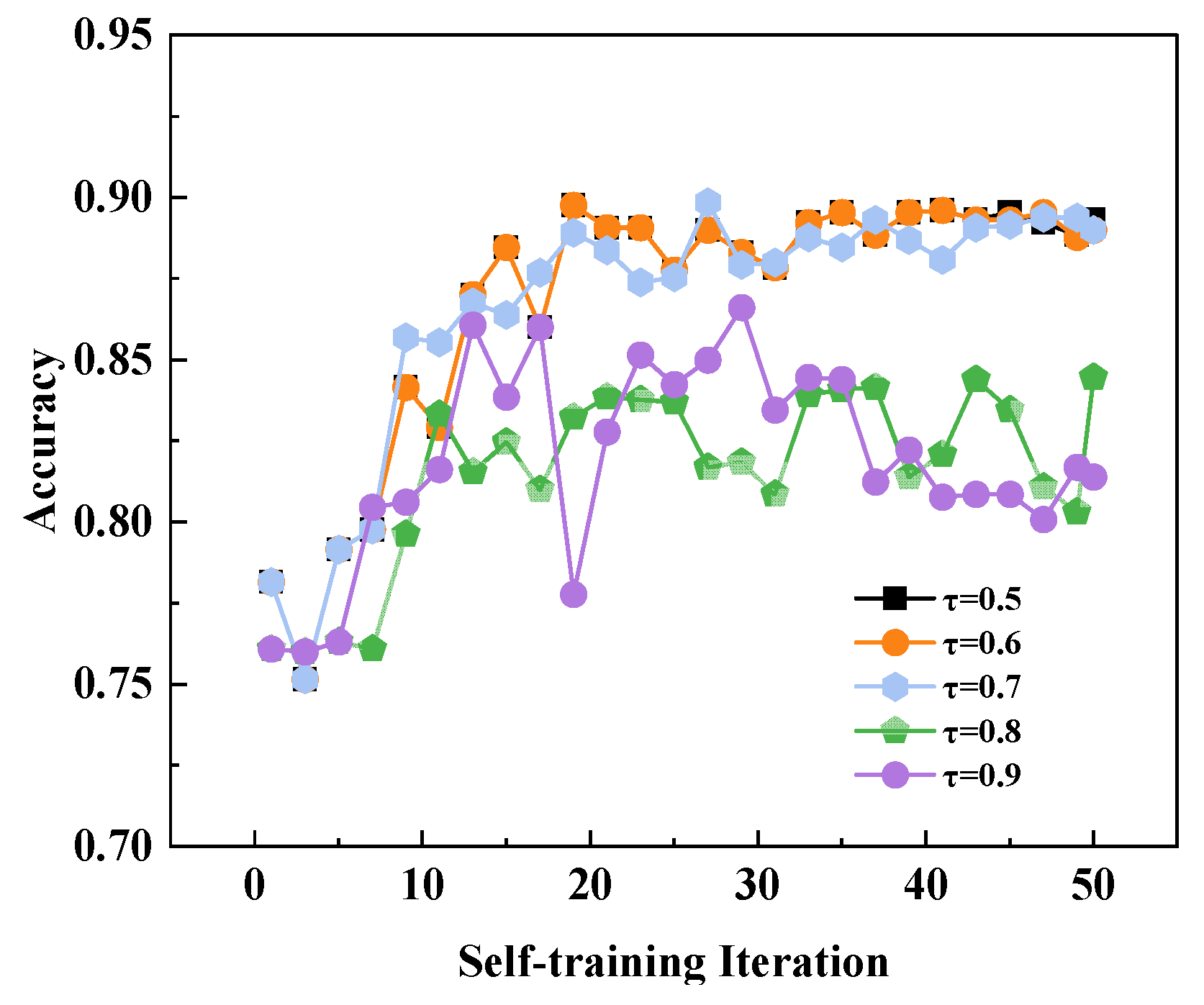

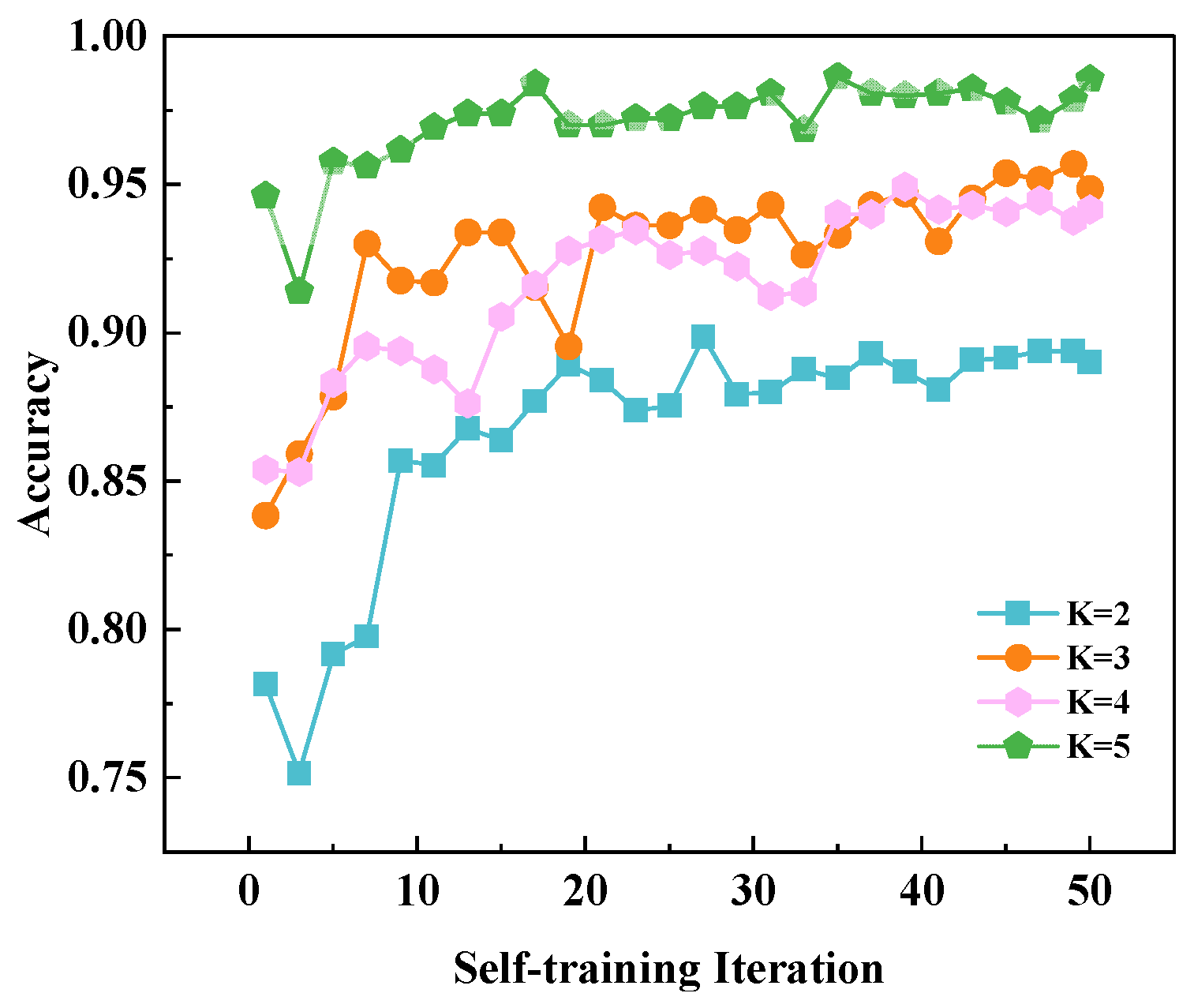

3.4. Ablation Study

3.4.1. The Ablation Analysis of Components

3.4.2. Ablation Analysis on the Upper Limit for Pixel Changes

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SE Block | Squeeze-and-Excitation B Block |

| AdvGAN++ | Adversarial Generative Adversarial Network (Enhanced Version) |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| K-means | K-means Clustering Algorithm |

| ReLU | Rectified Linear Unit |

References

- Nouboukpo, A. Combining Statistical & Deep Learning Models for Semi-Supervised Visual Recognition. Ph.D. Thesis, Université du Québec en Outaouais, Outaouais, QC, Canada, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Zhang, F.L.; Lei, J.; Xiang, W. Deep representation clustering of multitype damage features based on unsupervised generative adversarial network. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 25374–25393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, B.; Gui, J.G.; Jin, Y.Y.; Zhang, C.; Du, B.; Liu, B. Localization and recognition method of digital tubes in digital display instruments under complex environments. J. Mine Autom. 2018, 44, 85–89. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, X.J.; Yao, J.N.; Huang, B.Q.; Yang, S.; Wu, X.L. Detection and recognition of traffic signs under complex illumination conditions. Jisuanji Fuzhu Sheji Yu Tuxingxue Xuebao (J. Comput.-Aided Des. Comput. Graph.) 2023, 35, 293–302. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K.; Ning, X.; Liu, S. Medical image classification based on semi-supervised generative adversarial network and pseudo-labelling. Sensors 2022, 22, 9967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colangelo, M.L. Malware Family Classification with Semi-Supervised Learning (Doctoral Dissertation, Politecnico di Torino). Master’s Thesis, Politecnico di Torino, Piemonte, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Mancini, M.; Zhu, X.; Akata, Z. Semi-supervised and unsupervised deep visual learning: A survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2022, 46, 1327–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.Y.; Yang, X.S.; Zhang, T.Z.; Xu, C.S. Robust visual tracking method based on deep learning. Jisuanji Xuebao (Chin. J. Comput.) 2016, 39, 1419–1434. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Xiang, D. Digital instrument recognition method based on convolutional neural networks. Jixie Sheji Yu Zhizao Gongcheng (Mech. Des. Manuf. Eng.) 2018, 47, 63–66. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, L.; Wang, B. Semi-supervised Triple-GAN with similarity constraint for automatic underground object classification using ground penetrating radar data. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2025, 22, 3506605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, L.; Li, Y.; Liang, G.; Zhang, Y. Pseudo labeling methods for semi-supervised semantic segmentation: A review and future perspectives. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2024, 35, 3054–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadj Daoud, D.; Elouneg, M. Semi-Supervised Automatic Modulation Classification. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Ghardaïa, Ghardaia, Algeria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, B.; Lu, C. Semi-supervised medical image classification combined with unsupervised deep clustering. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Chen, J.; Liu, J.; Gu, Y.; Chen, L. Uncertainty-aware self-training with adversarial data augmentation for semi-supervised medical image segmentation. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 2025, 105, 107561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangla, P.; Jandial, S.; Varshney, S.; Balasubramanian, V.N. AdvGAN++: Harnessing latent layers for adversary generation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27–28 October 2019; pp. 2045–2048. [Google Scholar]

- Kumari, S.; Prabha, C.; Karim, A.; Hassan, M.M.; Azam, S. A comprehensive investigation of anomaly detection methods in deep learning and machine learning: 2019–2023. IET Inf. Secur. 2024, 2024, 8821891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Huang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, G. CycleGAN-based data augmentation for subgrade disease detection in GPR images with YOLOv5. Electronics 2024, 13, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Wu, D.; Shelley, T.; Schubel, P.; Twine, D.; Russell, J.; Zeng, X.; Zhang, J. A comprehensive survey on machine learning driven material defect detection. ACM Comput. Surv. 2025, 57, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yu, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, X.; Duan, J.; Bai, L. AM-CFDN: Semi-supervised anomaly measure-based coal flow foreign object detection network. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybern. 2025, 16, 3019–3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, S.P.; Khandeparkar, K.V.; Agrawal, N. CRUPL: A semi-supervised cyber attack detection with consistency regularization and uncertainty-aware pseudo-labeling in smart grid. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.00358. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, J.; Peng, Y.; Xiao, J. Color-based clustering for text detection and extraction in image. In Proceedings of the 15th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Augsburg, Germany, 24–29 September 2007; pp. 847–850. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Wang, C.; Dai, R. Text detection in images based on color texture features. In International Conference on Intelligent Computing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- Epshtein, B.; Ofek, E.; Wexler, Y. Detecting text in natural scenes with stroke width transform. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–18 June 2010; pp. 2963–2970. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Kasturi, R. Text detection using edge gradient and graph spectrum. In Proceedings of the 2010 20th International Conference on Pattern Recognition, Washington, DC, USA, 23–26 August 2010; pp. 3979–3982. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. Deep Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; Available online: http://www.deeplearningbook.org (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- yhsc0001. (n.d.). LED Seven-Segment Display Dataset [Data Set]. GitHub. Available online: https://github.com/yhsc0001/LEDshumaguanshujuji (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Shan, D.; Cheng, C.; Li, L.; Peng, Z.; He, Q. Semisupervised Fault Diagnosis of Gearbox Using Weighted Graph-Based Label Propagation and Virtual Adversarial Training. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 72, 3503411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z. Exploring the Spectrum of Supervision in Medical Image Analysis: From Fully Supervised to Semi-Supervised and Unsupervised Approaches. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Leicester, Leicester, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Dai, Y.J.; Liu, X.Y. Efficient sedimentary facies recognition using vision transformer and weakly supervised deep multi-view clustering. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 12345–12356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Hai, J.; Qiao, K.; Qi, X.; Li, Y.; Yan, B. Three-dimensional semi-supervised lumbar vertebrae region of interest segmentation based on MAE pre-training. J. X-Ray Sci. Technol. 2025, 33, 270–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, K.; Li, W.; Shao, Y.; Lu, S. Vi2ACT: Video-enhanced cross-modal co-learning with representation conditional discriminator for few-shot human activity recognition. In Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Melbourne, Australia, 28 October–1 November 2024; pp. 1848–1856. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. Visual Learning in Limited-Label Regime. Ph.D. Thesis, Queen Mary University of London, London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Li, J.; Liu, Z.; Tao, S.; Li, M. A comprehensive review of data processing and target recognition methods for ground penetrating radar underground pipeline B-scan data. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serey, J.; Quezada, L.; Alfaro, M.; Fuertes, G.; Vargas, M.; Ternero, R.; Sabattin, J.; Duran, C.; Gutierrez, S. Artificial intelligence methodologies for data management. Symmetry 2021, 13, 2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Wu, Z.; Zhu, J. Clustering-guided contrastive prototype learning: Towards semi-supervised medical image segmentation. Pattern Recognit. 2025, 158, 112321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golkarieh, A.; Razmara, P.; Lagzian, A.; Dolatabadi, A.; Mousavirad, S.J. Semi-supervised GAN with hybrid regularization and evolutionary hyperparameter tuning for accurate melanoma detection. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 31977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enguehard, J.; O’Halloran, P.; Gholipour, A. Semi-supervised learning with deep embedded clustering for image classification and segmentation. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 11093–11104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, K.; Berthelot, D.; Carlini, N.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Raffel, C.A.; Cubuk, E.D.; Kurakin, A.; Li, C.L. FixMatch: Simplifying semi-supervised learning with consistency and confidence. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2020; Volume 33, pp. 596–608. [Google Scholar]

- Wannachai, A.; Boonyung, W.; Champrasert, P. Real-time seven segment display detection and recognition online system using CNN. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Bio-inspired Information and Communication Technologies, Shanghai, China, 7–8 July 2020; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 52–67. [Google Scholar]

| Class | Local Dataset | Public Dataset | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Train | Test | Val | Total | Train | Test | Val | Total | |

| 1 | 800 | 100 | 100 | 1000 | 2838 | 354 | 354 | 3548 |

| 2 | 800 | 100 | 100 | 1000 | 1598 | 201 | 199 | 1998 |

| 3 | 800 | 100 | 100 | 1000 | 1404 | 176 | 175 | 1755 |

| 4 | 800 | 100 | 100 | 1000 | 1928 | 242 | 241 | 2411 |

| 5 | 800 | 100 | 100 | 1000 | 1396 | 176 | 174 | 1746 |

| 6 | 800 | 100 | 100 | 1000 | 1647 | 207 | 205 | 2059 |

| 7 | 800 | 100 | 100 | 1000 | 1550 | 195 | 193 | 1938 |

| 8 | 800 | 100 | 100 | 1000 | 1448 | 181 | 181 | 1810 |

| 9 | 800 | 100 | 100 | 1000 | 1308 | 165 | 163 | 1636 |

| −1 | 800 | 100 | 100 | 1000 | - | - | - | - |

| - | 800 | 100 | 100 | 1000 | - | - | - | - |

| . | 800 | 100 | 100 | 1000 | - | - | - | - |

| Item | Configuration |

|---|---|

| Operation System | Windows 11 Home |

| CPU | Intel Core i7-12700H (14 cores, 20 threads) |

| GPU | NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3050 Laptop GPU (4 GB) |

| Python | 3.9.23 |

| PyTorch | 2.5.1 |

| ML Libraries | scikit-learn 1.3.0/NumPy 1.24.3 |

| Reproducibility | Random Seed = 42 |

| Cuda sensor pixels | 12.1 1080p |

| Method | Local Dataset | Public Dataset | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test_Acc% | ΔLocal% | Test_Acc% | ΔPublic% | |

| Proposed(ours) | 89.3 ± 0.4 | 13.1 | 98.1 ± 0.2 | 1.3 |

| Pseudo-Label | 76.2 ± 0.8 | 0 | 87.4 ± 0.6 | −9.4 |

| Entropy Minimization | 71.1 ± 1.1 | −5.1 | 96.2 ± 0.5 | −0.6 |

| Π-Model | 68.5 ± 0.9 | −7.7 | 85.3 ± 0.7 | −11.5 |

| Mean Teacher | 73.1 ± 0.7 | −3.1 | 87.0 ± 0.5 | −9.8 |

| Virtual Adversarial Training | 52.4 ± 1.5 | −23.8 | 84.8 ± 0.8 | −12 |

| Label Spreading | 67.3 ± 0.9 | −8.9 | 96.8 ± 0.3 | 0 |

| ε | Clean | AdvGAN++ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FGSM | PGD | Auto-Attack | FGSM | PGD | Auto-Attack | |

| 0 | 76% | 76% | 76% | 89% | 89% | 89% |

| 0.05 | 73% | 73% | 73% | 86% | 86% | 86% |

| 0.1 | 69% | 69% | 69% | 84% | 84% | 84% |

| 0.15 | 63% | 61% | 61% | 79% | 78% | 78% |

| 0.2 | 56% | 47% | 46% | 75% | 69% | 66% |

| 0.25 | 50% | 41% | 39% | 68% | 60% | 56% |

| 0.3 | 45% | 38% | 33% | 58% | 52% | 42% |

| ε | Clean | AdvGAN++ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FGSM | PGD | Auto-Attack | FGSM | PGD | Auto-Attack | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0.05 | 27% | 27% | 27% | 14% | 14% | 14% |

| 0.1 | 31% | 31% | 31% | 16% | 16% | 16% |

| 0.15 | 37% | 39% | 40% | 21% | 22% | 22% |

| 0.2 | 44% | 53% | 54% | 25% | 31% | 34% |

| 0.25 | 50% | 59% | 61% | 32% | 40% | 44% |

| 0.3 | 55% | 62% | 67% | 42% | 48% | 57% |

| Method | Test_Acc | Train_Loss |

|---|---|---|

| CNN | 76% | 0.0126 |

| CNN-SE | 80% | 0.0136 |

| CNN-SE-K-means | 83% | 0.0052 |

| CNN-SE-K-means-AdvGAN++ | 89% | 0.0029 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xiang, X.; Zhu, C.; Ou, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Zheng, S.; Chen, Z. Semi-Supervised Seven-Segment LED Display Recognition with an Integrated Data-Acquisition Framework. Sensors 2026, 26, 265. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010265

Xiang X, Zhu C, Ou Z, Zhang Q, Zheng S, Chen Z. Semi-Supervised Seven-Segment LED Display Recognition with an Integrated Data-Acquisition Framework. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):265. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010265

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiang, Xikai, Chonghua Zhu, Ziyi Ou, Qixuan Zhang, Shihuai Zheng, and Zhen Chen. 2026. "Semi-Supervised Seven-Segment LED Display Recognition with an Integrated Data-Acquisition Framework" Sensors 26, no. 1: 265. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010265

APA StyleXiang, X., Zhu, C., Ou, Z., Zhang, Q., Zheng, S., & Chen, Z. (2026). Semi-Supervised Seven-Segment LED Display Recognition with an Integrated Data-Acquisition Framework. Sensors, 26(1), 265. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010265