Comparison of Benchtop and Portable Near-Infrared Instruments to Predict the Type of Microplastic Added to High-Moisture Food Samples

Abstract

1. Introduction

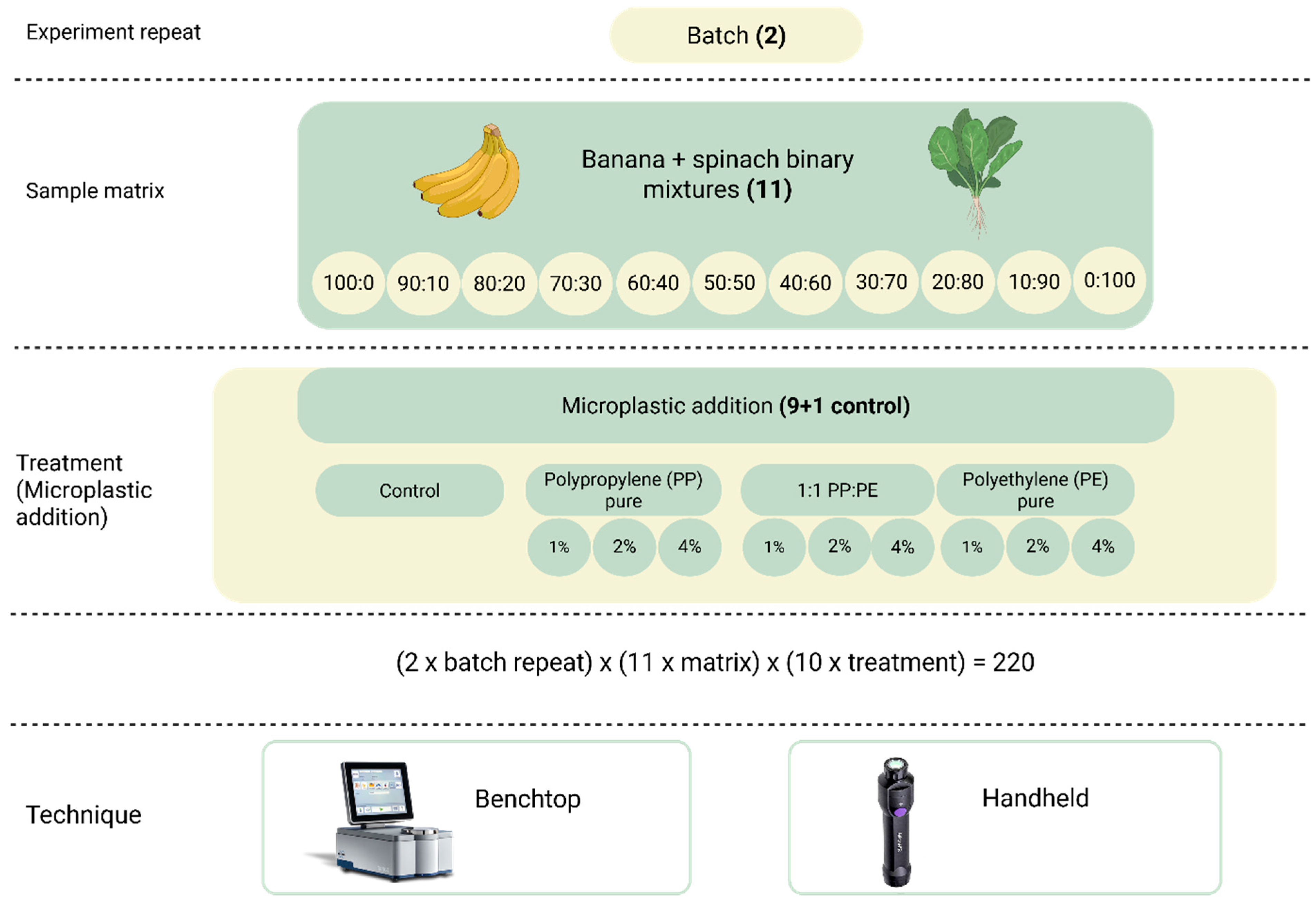

2. Materials and Methods

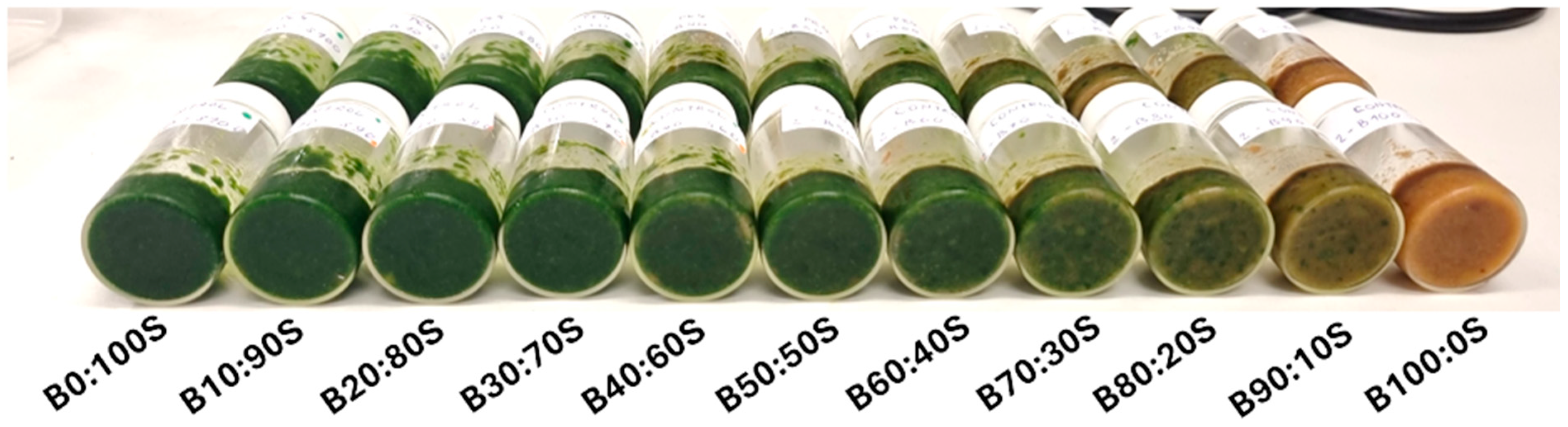

2.1. Sample Preparation

2.2. Grinding and Preparation of Microplastics

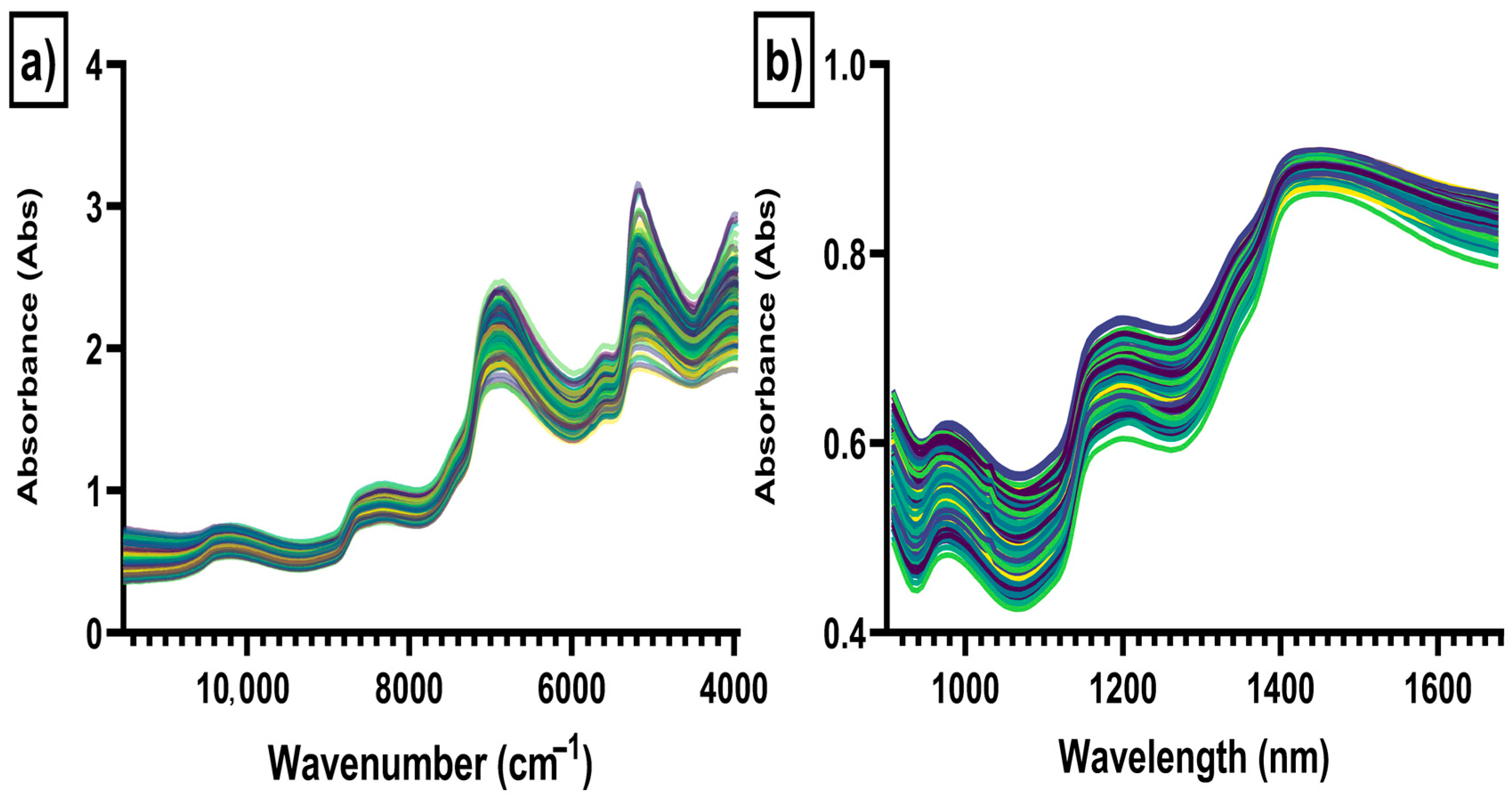

2.3. Near-Infrared Spectra Data Collection

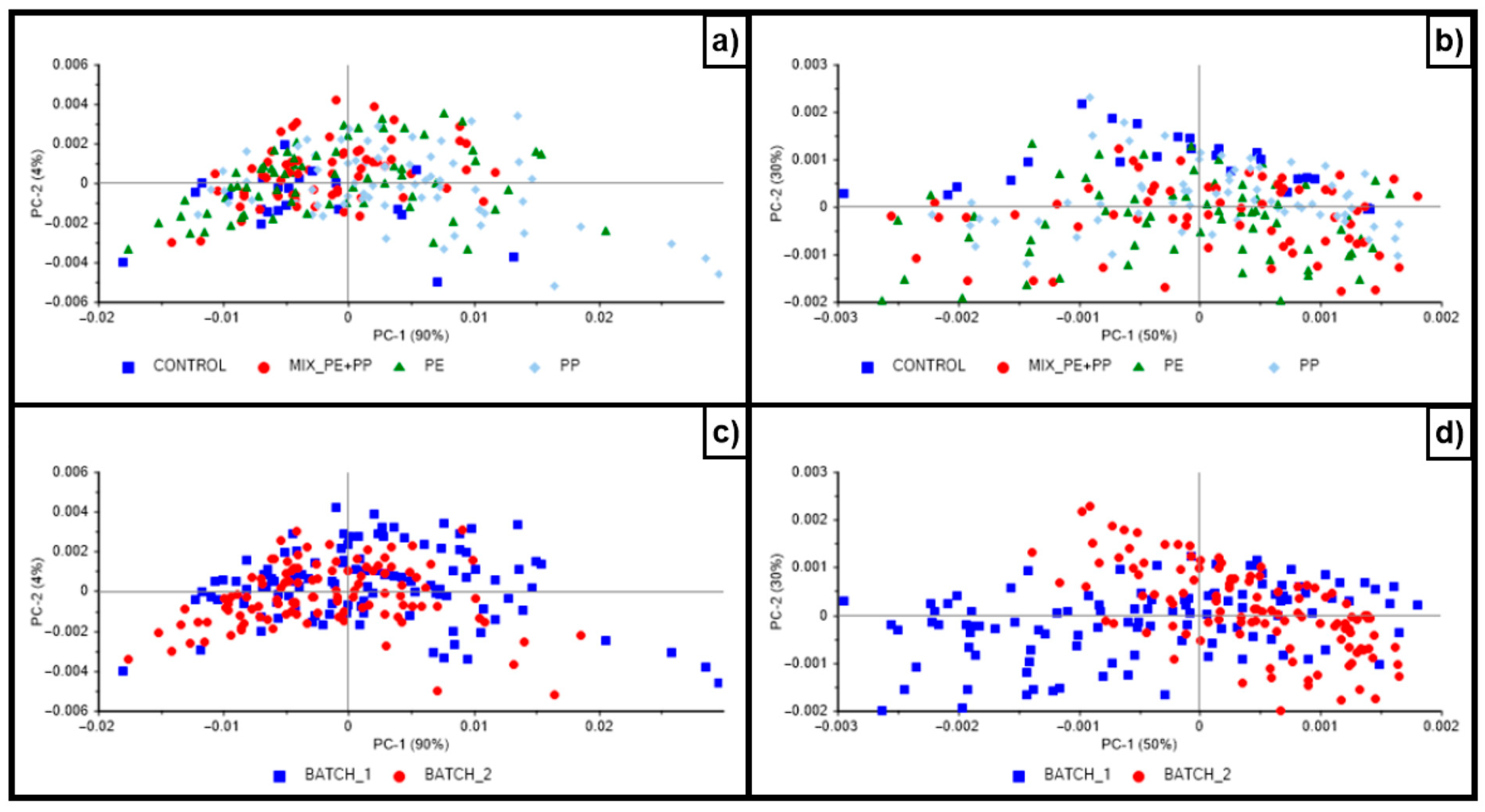

2.4. Data Analysis

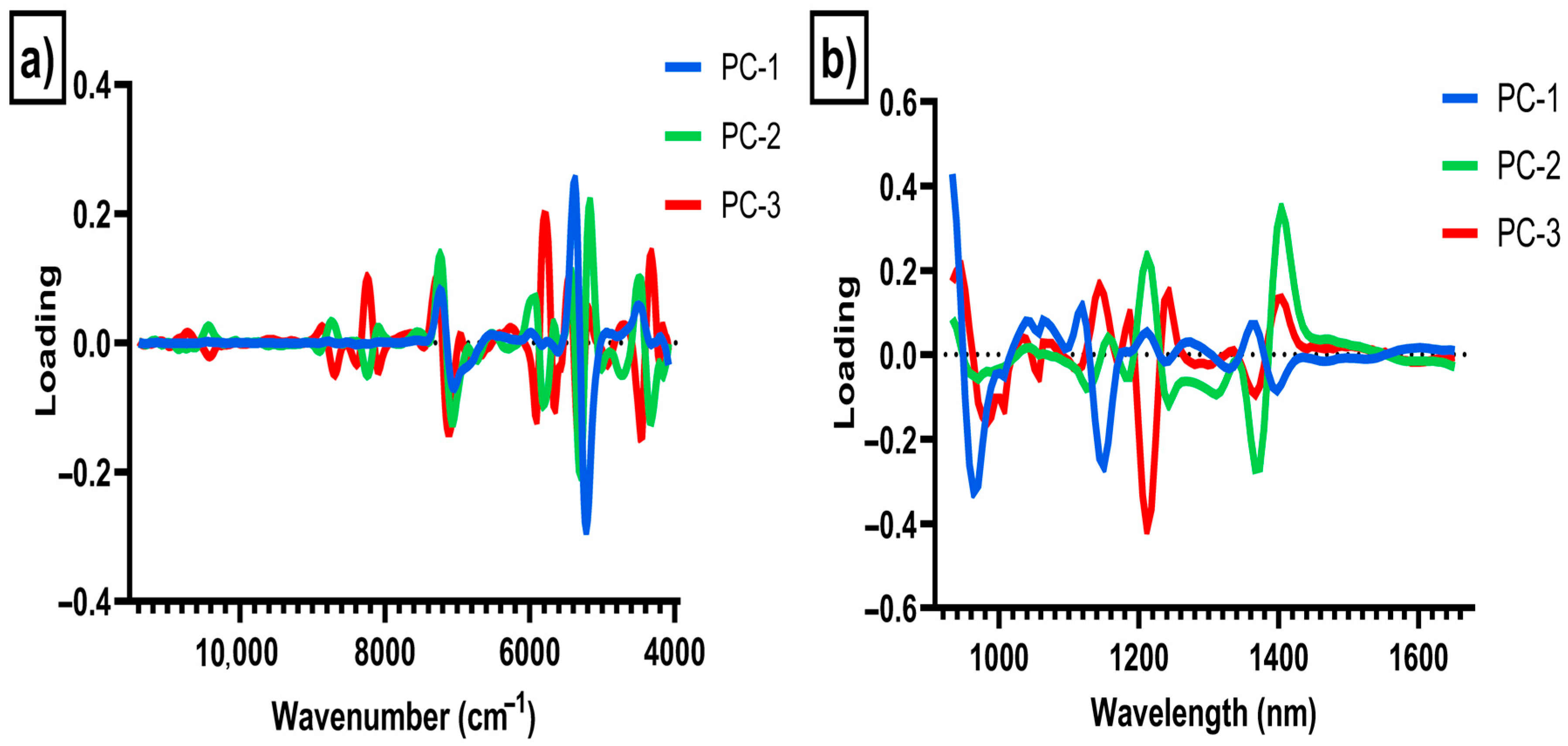

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fung, F.; Wang, H.S.; Menon, S. Food safety in the 21st century. Biomed. J. 2018, 41, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, K.; Pérez Villarreal, B.; Barranco, A.; Belc, N.; Björnsdóttir, B.; Fusco, V.; Rainieri, S. An introduction to current food safety needs. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 84, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziani, K.; Ioniță-Mîndrican, C.-B.; Mititelu, M.; Neacșu, S.M.; Negrei, C.; Moroșan, E.; Drăgănescu, D.; Preda, A.-T. Microplastics: A real global threat for environment and food safety: A state-of-the-art review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelis, J.L.D.; Schacht, V.J.; Dawson, A.L.; Bose, U.; Tsagkaris, A.S.; Dvorakova, D.; Beale, D.J.; Can, A.; Elliott, C.T.; Thomas, K.V.; et al. The measurement of food safety and security risks associated with micro- and nanoplastic pollution. Trac. Trends Anal. Chem. 2023, 161, 116993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Armendáriz, C.; Alejandro-Vega, S.; Paz-Montelongo, S.; Gutiérrez-Fernández, Á.J.; Carrascosa-Iruzubieta, C.J.; Hardisson-de la Torre, A. Microplastics as emerging food contaminants: A challenge for food safety. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainieri, S.; Barranco, A. Microplastics, a food safety issue? Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 84, 55–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.; Love, D.C.; Rochman, C.M.; Neff, R.A. Microplastics in seafood and the implications for human health. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2018, 5, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toner, K.; Midway, S.R. Historic fish samples from the Southeast USA lack microplastics. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 776, 145923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Shi, H.; Li, L.; Li, J.; Jabeen, K.; Kolandhasamy, P. Microplastic pollution in table salts from China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 13622–13627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çıtar Dazıroğlu, M.E.; Bilici, S. The hidden threat to food safety and human health: Microplastics. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 21913–21935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadac-Czapska, K.; Knez, E.; Grembecka, M. Food and human safety: The impact of microplastics. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nut. 2022, 64, 3502–3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rillig, M.C. Microplastic in terrestrial ecosystems and the soil? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 6453–6454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP. Marine Plastic Debris and Microplastics: Global Lessons and Research to Inspire Action and Guide Policy Change; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod, M.; Arp, H.P.H.; Tekman, M.B.; Jahnke, A. The global threat from plastic pollution. Science 2021, 373, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najahi, H.; Banni, M.; Nakad, M.; Abboud, R.; Assaf, J.C.; Operato, L.; Hamd, W. Plastic pollution in food packaging systems: Impact on human health, socioeconomic considerations and regulatory framework. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2025, 18, 100667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S.; Levermore, J.; Ishikawa, Y. Application of infrared and near infrared micro spectroscopy to microplastic human exposure measurements. Appl. Spectrosc. 2023, 77, 1105–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Gebremeskal, Y.H.; Maksimova, B.V.; Zun, P.; Eremeeva, N.B. Microplastic contamination and detection in food systems: A review of machine learning, traditional methods, and other relevant factors. Microchem. J. 2025, 218, 115440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werkman, A.; van Doorn, J.; van Ittersum, K.; Kok, A. No waste like home: How the good provider identity drives excessive purchasing and household food waste. J. Environ. Psychol. 2025, 103, 102564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, R.V.; Dhital, S.; Williamson, G.; Barber, E. Nutrient composition, physical characteristics and sensory quality of spinach-enriched wheat bread. Foods 2024, 13, 2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, G.J. A review of root, tuber and banana crops in developing countries: Past, present and future. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 56, 1093–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beć, K.B.; Grabska, J.; Huck, C.W. Miniaturized NIR spectroscopy in food analysis and quality control: Promises, challenges, and perspectives. Foods 2022, 11, 1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés, V.; Blasco, J.; Aleixos, N.; Cubero, S.; Talens, P. Monitoring strategies for quality control of agricultural products using visible and near-infrared spectroscopy: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 85, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biancolillo, A.; Marini, F.; Ruckebusch, C.; Vitale, R. Chemometric strategies for spectroscopy-based food authentication. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buv’e, C.; Saeys, W.; Rasmussen, M.A.; Neckebroeck, B.; Hendrickx, M.; Grauwet, T.; Van Loey, A. Application of multivariate data analysis for food quality investigations: An example-based review. Food Res. Int. 2022, 151, 110878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlebois, S.; Schwab, A.; Henn, R.; Huck, C.W. Food fraud: An exploratory study for measuring consumer perception towards mislabeled food products and influence on self-authentication intentions. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohumi, S.; Lee, S.; Lee, H.; Cho, K.B. A review of vibrational spectroscopic techniques for the detection of food authenticity and adulteration. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 46, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, K.M.; Khakimov, B.; Engelsen, S.B. The use of rapid spectroscopic screening methods to detect adulteration of food raw materials and ingredients. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2016, 10, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoero, G.; Barbera, S.; Kaihara, H.; Mabrouki, S.; Patrucco, S.G.; Abid, K.; Tassone, S. Rapid detection of microplastics in feed using near-infrared spectroscopy. Acta IMEKO 2024, 13, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Lin, H.; Xu, S.; He, L. Recent advances in spectroscopic techniques for the analysis of microplastics in food. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 1410–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Z.; Liu, Y.; Yang, R.; Dong, G.; Lin, X.; Yang, Y.; Yang, F. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of microplastics in chicken meat using near-infrared spectroscopy. Microchem. J. 2025, 210, 112979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, J.; Deng, J.; Ding, Z.; Jiang, H.; Chen, Q. Comparative analysis of characteristic wavelength extraction methods for non-destructive detection of microplastics in wheat using FT-NIR spectroscopy. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2024, 142, 105555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, S.; Cureton, S.; Szuhan, M.; McCarten, J.; Arvanitis, P.; Ascione, M.; Truong, V.K.; Chapman, J.; Cozzolino, D. Microplastic adulteration in homogenized fish and seafood—A mid-infrared and machine learning proof of concept. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectros. 2021, 260, 119985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Hao, L.; Tian, H.; Liu, J.; Dong, C.; Xue, J. Qualitative discrimination and quantitative prediction of microplastics in ash based on near-infrared spectroscopy. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 469, 133971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Yi, L.; Du, G.; Hu, X.; Huang, Y. Visual characterization of microplastics in corn flour by near field molecular spectral imaging and data mining. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 862, 160714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.-H.; Kim, J.-W.; Pham, T.D.; Tarafdar, A.; Hong, S.; Chun, S.-H.; Lee, S.-H.; Kang, D.-Y.; Kim, J.-Y.; Kim, S.-B.; et al. Microplastics in food: A review on analytical methods and challenges. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savitzky, A.; Golay, M.J.E. Smoothing and differentiation of data by simplified least squares procedures. Anal. Chem. 1964, 36, 1627–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau, S.; Cozzolino, D.; Clark, C.J. Contributions of Fourier-Transform mid infrared (FT-MIR) spectroscopy to the study of fruit and vegetables: A Review. Post. Biol. Technol. 2019, 148, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.; Dardenne, P.; Flinn, P. Tutorial: Items to be include in a report on a near infrared spectroscopy project. J. Near Infrared Spectros. 2017, 25, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workman, J.; Weyer, L. Practical Guide to Interpretive Near-Infrared Spectroscopy; CRC Press Taylor and Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, I.; Sánchez, M.T.; Vega-Castellote, M.; Luqui-Muñoz, N.; Pérez-Marín, D. Routine NIRS analysis methodology to predict quality and safety indexes in spinach plants during their growing season in the field. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol Biomol. Spectros. 2021, 246, 118972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Castellote, M.; Pérez-Marín, D.; Torres, I.; Sánchez, M.T. Online NIRS analysis for the routine assessment of the nitrate content in spinach plants in the processing industry using linear and non-linear methods. LWT 2021, 151, 112192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.F.; Batista, D.B.; Soares, T.F.; Henriques, C.A.; Luna, A.S.; Pinto, L. Uncovering complex adulteration scenarios on unripe banana flour with hierarchical multiclass modelling of NIR data. Food Control 2025, 181, 111748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beć, K.B.; Grabska, J.; Badzoka, J.; Huck, C.W. Spectra–structure correlations in the NIR region of polymers from quantum chemical calculations: The cases of aromatic ring, C=O, C≡N and C–Cl functionalities. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectros. 2021, 262, 120085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, P. Practical aspects of sampling for NIRS analysis. In Handbook of Near-Infrared Analysis, 4th ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, I.; Cowe, I. Sample preparation. In Near-Infrared Spectroscopy in Agriculture; Craig, A., Roberts, J.W., Jr., James, B.R., III, Eds.; American Society of Agronomy: Madison, WI, USA, 2024; Volume 44, pp. 75–112. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Cerezo, A.A.; Berzaghi, P.; Magrin, L. Comparative near Infrared (NIR) spectroscopy calibrations performance of dried and undried forage on dry and wet matter bases. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectros. 2024, 316, 124287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cozzolino, D.; Fassio, A.; Fernández, E.; Restaino, E.; La Manna, A. Measurement of chemical composition in wet whole maize silage by visible and near infrared reflectance spectroscopy. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2026, 129, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | R2 CV | SECV | RPD | LV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benchtop instrument (all samples) | 204 | 0.88 | 0.44 | 3.6 | 7 |

| Portable instrument (all samples) | 200 | 0.67 | 0.55 | 2.4 | 10 |

| Portable instrument (batch 1) | 160 | 0.84 | 0.40 | 3.3 | 11 |

| Portable instrument (batch 2) | 110 | 0.64 | 0.48 | 2.8 | 7 |

| Short to medium wavelengths | 200 | 0.88 | 0.46 | 3.0 | 6 |

| Long wavelengths | 199 | 0.86 | 0.49 | 2.8 | 5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kolobaric, A.; Alagappan, S.; Čaloudová, J.; Hoffman, L.C.; Chapman, J.; Cozzolino, D. Comparison of Benchtop and Portable Near-Infrared Instruments to Predict the Type of Microplastic Added to High-Moisture Food Samples. Sensors 2026, 26, 210. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010210

Kolobaric A, Alagappan S, Čaloudová J, Hoffman LC, Chapman J, Cozzolino D. Comparison of Benchtop and Portable Near-Infrared Instruments to Predict the Type of Microplastic Added to High-Moisture Food Samples. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):210. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010210

Chicago/Turabian StyleKolobaric, Adam, Shanmugam Alagappan, Jana Čaloudová, Louwrens C. Hoffman, James Chapman, and Daniel Cozzolino. 2026. "Comparison of Benchtop and Portable Near-Infrared Instruments to Predict the Type of Microplastic Added to High-Moisture Food Samples" Sensors 26, no. 1: 210. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010210

APA StyleKolobaric, A., Alagappan, S., Čaloudová, J., Hoffman, L. C., Chapman, J., & Cozzolino, D. (2026). Comparison of Benchtop and Portable Near-Infrared Instruments to Predict the Type of Microplastic Added to High-Moisture Food Samples. Sensors, 26(1), 210. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010210