Influences and Training Strategies for Effective Object Detection in Challenging Environments Using YOLO NAS-L

Abstract

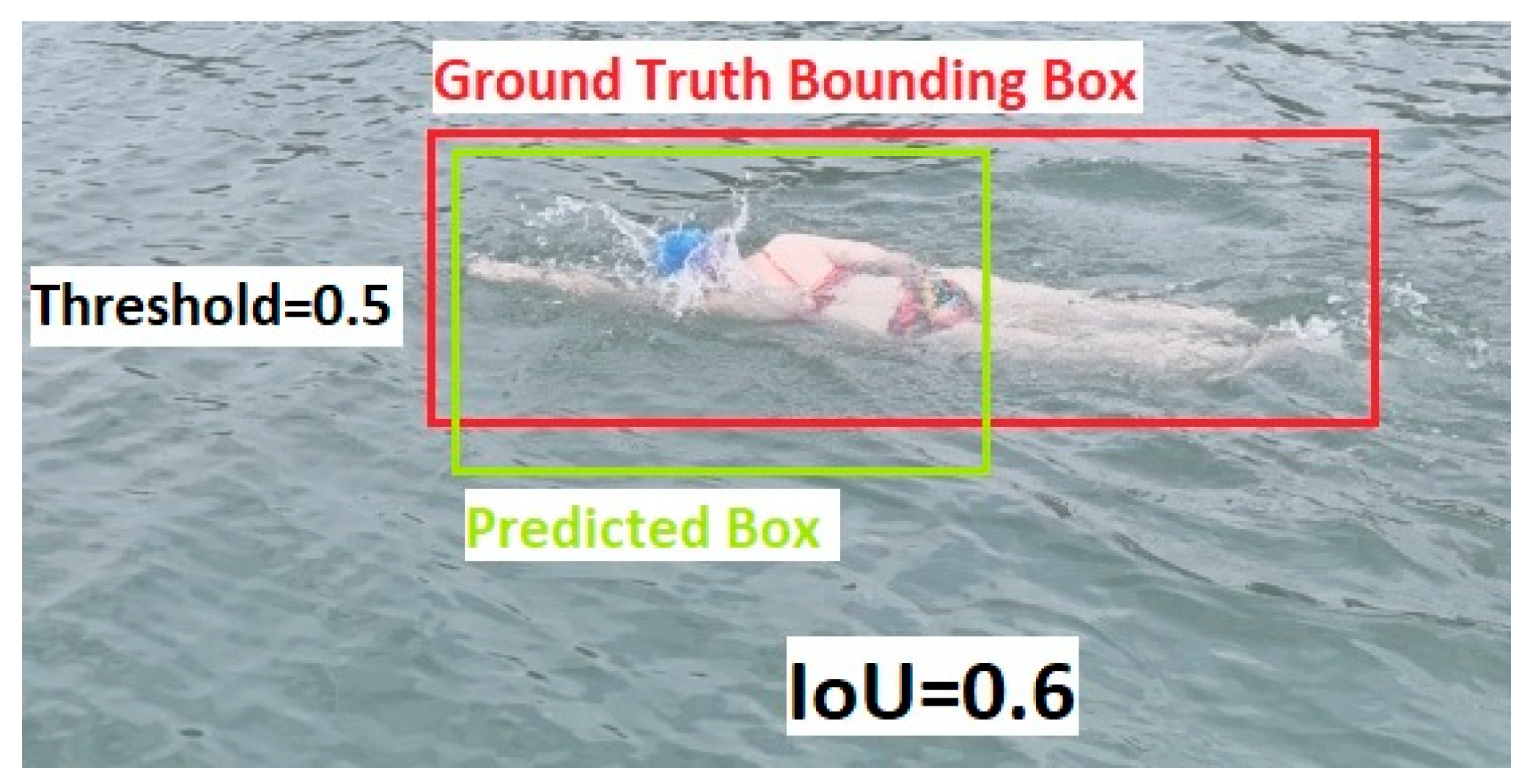

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Batch Size and Batch Accumulation

3.2. Number of Epochs

3.3. Data Size & Runtime

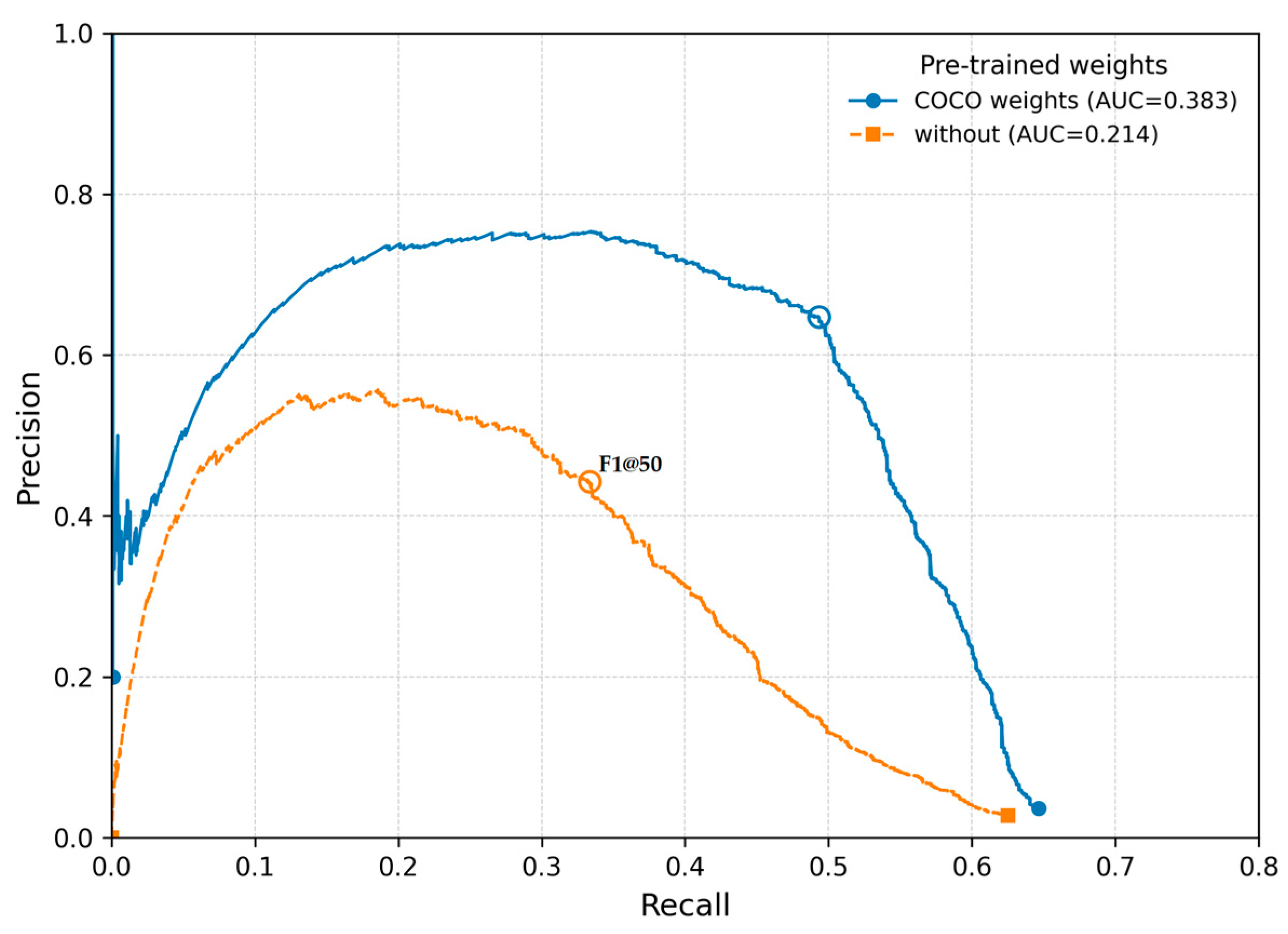

3.4. Pre-Trained Weights

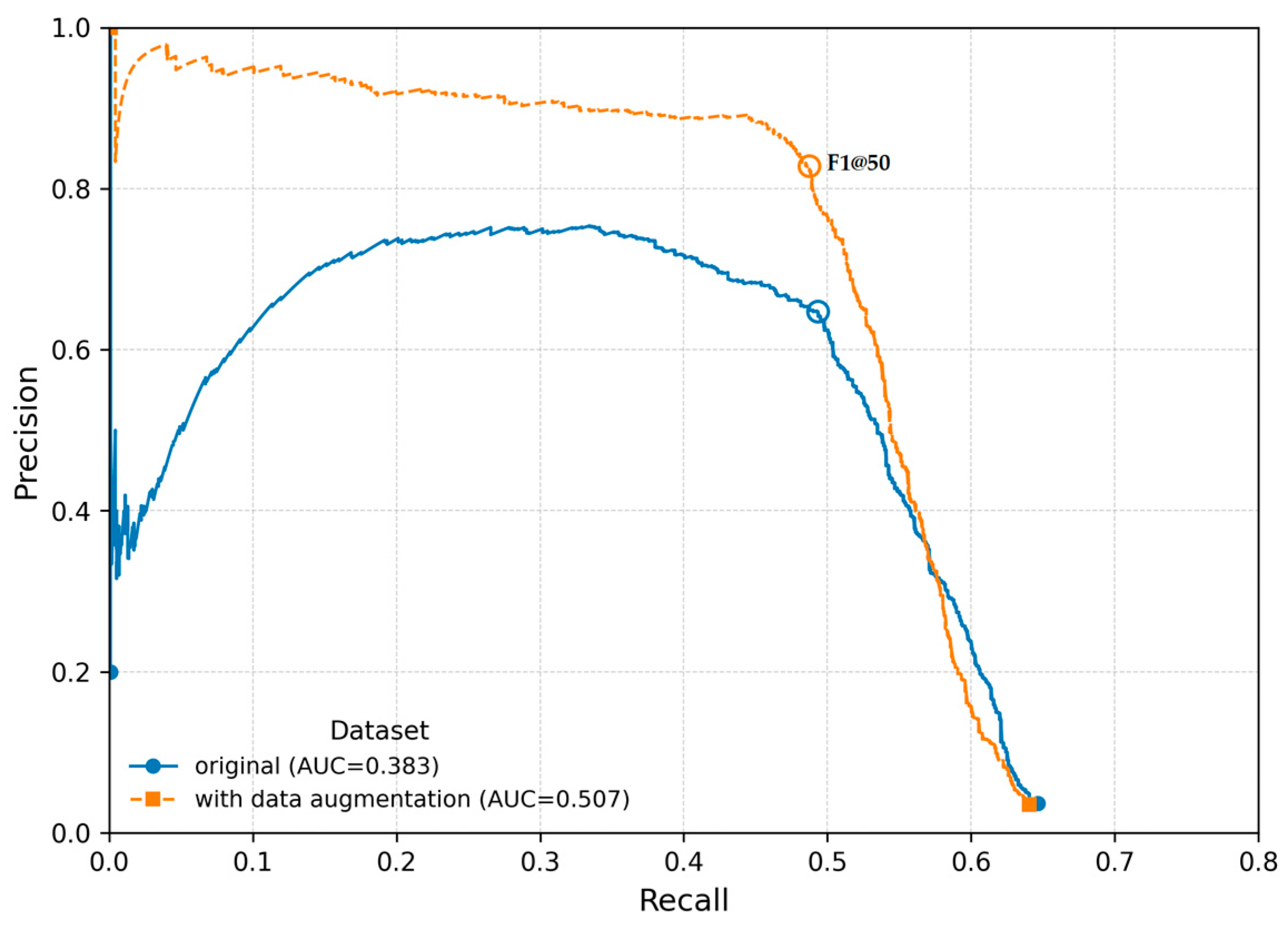

3.5. Data Augmentation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| BA | Batch Accumulation |

| COCO | Microsoft Common Objects |

| CUDA | Compute Unified Device Architecture |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| MANOVA | Multivariate Analyses Of Variance |

| mAP | Mean Average Precision |

| MixedLM | Linear Mixed-Effects Model |

| PELT algorithm | Pruned Exact Linear Time (PELT) algorithm |

| YOLO | You Only Look Once |

References

- Zou, Z.; Chen, K.; Shi, Z.; Guo, Y.; Ye, J. Object detection in 20 years: A survey. Proc. IEEE 2023, 111, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Chai, L.; Jin, L.; Yan, J. Hierarchical alignment network for domain adaptive object detection in aerial images. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2024, 208, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, Y.; Li, W.; Han, J.; Zhou, K.; Loy, C.C. Contextual Object Detection with Multimodal Large Language Models. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2024, 133, 825–843. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/2305.18279. [CrossRef]

- OMEGA. World of OMEGA Swimming. 2024. Available online: https://www.omegawatches.com/en-ch/world-of-omega/sport/swimming (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terven, J.; Córdova-Esparza, D.-M.; Romero-González, J.-A. A Comprehensive Review of YOLO Architectures in Computer Vision: From YOLOv1 to YOLOv8 and YOLO-NAS. Mach. Learn. Knowl. Extr. 2023, 5, 1680–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Ergu, D.; Liu, F.; Cai, Y.; Ma, B. A Review of Yolo Algorithm Developments. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2021, 199, 1066–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, H.; Kotlyar, O.; Andreasson, H.; Lilienthal, A.J. Robust Object Detection in Challenging Weather Conditions. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–8 January 2024; pp. 7508–7517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapkota, R.; Qureshi, R.; Flores-Calero, M.; Badgujar, C.; Nepal, U.; Poulose, A.; Zeno, P.; Vaddevolu, U.B.P.; Khan, S.; Shoman, M.; et al. YOLO advances to its genesis: A decadal and comprehensive review of the You Only Look Once (YOLO) series. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ultralytics. YOLO-NAS. Models: Pre-trained Models. 2025. Available online: https://docs.ultralytics.com/models/yolo-nas/#pre-trained-models (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Aftab Hayat, M.; Yang, G.; Iqbal, A.; Saleem, A.; Hussain, A.; Mateen, M. The Swimmers Motion Detection Using Improved VIBE Algorithm. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Robotics and Automation in Industry (ICRAI), Rawalpindi, Pakistan, 21–22 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Callaway, A.J.; Cobb, J.E.; Jones, I. A comparison of video and accelerometer based approaches applied to performance monitoring in swimming. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2009, 4, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.H. A Camera Calibration Algorithm for the Underwater Motion Analysis. In Proceedings of the XVII International Symposium on Biomechanics in Sports, Edith Cowan University, Perth, Australia, 30 June–6 July 1999; pp. 257–260. [Google Scholar]

- Goyal, P.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.; Noordhuis, P.; Wesolowski, L.; Kyrola, A.; Tulloch, A.; Jia, Y.; He, K. Accurate, Large Minibatch SGD: Training ImageNet in 1 Hour. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1706.02677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Xiao, T.; Li, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Jia, K.; Yu, G.; Sun, J. MegDet: A Large Mini-Batch Object Detector. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/1711.0724.

- You, Y.; Li, J.; Reddi, S.; Hseu, J.; Kumar, S.; Bhojanapalli, S.; Song, X.; Demmel, J.; Keutzer, K.; Hsieh, C.-J. Large Batch Optimization for Deep Learning: Training BERT in 76 minutes. arxiv. 2020. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/1904.00962.

- Ultralytics. Batch Size. 2025. Available online: https://www.ultralytics.com/glossary/batch-size (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Ultralytics. Model Training with Ultralytics, Y.O.L.O. 2025. Available online: https://docs.ultralytics.com/modes/train (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Beyer, L.; Hénaff, O.J.; Kolesnikov, A.; Zhai, X.; van den Oord, A. Are we done with ImageNet? arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.07159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recht, B.; Roelofs, R.; Schmidt, L.; Shankar, V. Do ImageNet Classifiers Generalize to ImageNet? In Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML 2019), Long Beach, CA, USA, 9–15 June 2019; PMLR 97, pp. 5389–5400. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, P.; Khehra, B.S.; Mavi Er, B.S. Data Augmentation for Object Detection: A Review. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Midwest Symposium on Circuits and Systems (MWSCAS), Lansing, MI, USA, 8–11 August 2021; pp. 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoph, B.; Cubuk, E.D.; Ghiasi, G.; Lin, T.-Y.; Shlens, J.; Le, Q.V. Learning Data Augmentation Strategies for Object Detection. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2020; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 566–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.-L.; Zhang, Z. The YOLO Framework: A Comprehensive Review of Evolution, Applications, and Benchmarks in Object Detection. Computers 2024, 13, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Ma, X.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, Y. COMO: Cross-Mamba Interaction and Offset-Guided Fusion for Multimodal Object Detection. Inf. Fusion 2026, 125, 103414. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/2412.18076. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Jilani, A.K.; Kumar, P.; Nikiforova, A. Improved YOLOv3-tiny Object Detector with Dilated CNN for Drone-Captured Images. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Intelligent Data Science Technologies and Applications (IDSTA), San Antonio, TX, USA, 5–7 September 2022; pp. 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | mAP | Inference Time [ms] |

|---|---|---|

| YOLO NAS-S | 47.5 | 3.21 |

| YOLO NAS-M | 51.55 | 5.85 |

| YOLO NAS-L | 52.22 | 7.87 |

| Predictor | Coefficient (β) | Std. Error | z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.681 | 0.008 | 80.48 | <0.0001 |

| Batch Size (32) | −0.021 | 0.012 | −1.79 | 0.074 |

| Accumulation (2) | 0.001 | 0.012 | 0.12 | 0.902 |

| Accumulation (4) | 0.000 | 0.012 | 0.02 | 0.983 |

| Effective Batch Size (64 = 32 × 2) | −0.004 | 0.017 | −0.21 | 0.832 |

| Effective Batch Size (128 = 32 × 4) | −0.013 | 0.017 | −0.79 | 0.432 |

| Predictor | Coefficient (β) | Std. Error | z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.329 | 0.011 | 30.51 | <0.0001 |

| Batch Size (32) | −0.004 | 0.015 | −0.26 | 0.796 |

| Accumulation (2) | −0.027 | 0.015 | −1.77 | 0.076 |

| Accumulation (4) | −0.058 | 0.015 | −3.78 | <0.001 |

| Effective Batch Size (64 = 32 × 2) | 0.002 | 0.022 | 0.11 | 0.917 |

| Effective Batch Size (128 = 32 × 4) | −0.055 | 0.022 | −2.57 | 0.010 |

| Image Size | Run | Epoch Plateau | Breakpoint (PELT-Algorithm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 416 × 416 px | 1 | 45 | 65 |

| 416 × 416 px | 2 | 37 | 35 |

| 640 × 640 px | 1 | 66 | 50 |

| 640 × 640 px | 2 | 46 | 55 |

| 1024 × 1024 px | 1 | 44 | 50 |

| 1024 × 1024 px | 2 | 56 | 75 |

| Effect | Test | Value | DF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | Wilks Lambda | 0.0007 | 2 |

| Pillai’s Trace | 0.9993 | 2 | |

| Hotelling-Lawley | 1509.5409 | 2 | |

| Roy’s Greatest Root | 1509.5409 | 2 | |

| Image size | Wilks Lambda | 0.3165 | 2 |

| Pillai’s Trace | 0.6835 | 2 |

| Sum of Squares | df | F | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data Size | 0.000044 | 1 | 0.88898 | 0.44528 |

| Residual | 0.000098 | 2 |

| Sum of Squares | df | F | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data Size | 31,472,100 | 1 | 224.774223 | 0.004419 |

| Residual | 28,003 | 2 |

| Effect | Df | Sum of Squares | F | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dataset size (1.71 GB vs. 10.2 GB) | 1 | 0.2420 | 1731.94 | |

| Metric (mAP@50 vs. F1@50) | 1 | 0.3681 | 2634.36 | |

| Interaction (Dataset × Metric) | 1 | 0.00047 | 3.37 | 0.104 |

| Residual | 8 | 0.00112 | - | - |

| Comparison | Mean Difference | Adjusted p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| F1@50 (1.71 GB)–mAP@50 (1.71 GB) | 0.3378 | <0.001 |

| F1@50 (1.71 GB)–F1@50 (1.71 GB) | 0.2715 | <0.001 |

| F1@50 (1.71 GB)–mAP@50 (10.2 GB) | 0.6343 | <0.001 |

| mAP@50 (1.71 GB)–F1@50 (10.2 GB) | −0.0663 | 0.0006 |

| mAP@50 (1.71 GB)–mAP@50 (10.2 GB) | 0.2966 | <0.001 |

| F1@50 (10.2 GB)–mAP@50 (10.2 GB) | 0.3628 | <0.001 |

| Comparison | Mean Difference | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| COCO–mAP@50 vs. COCO–F1@50 | +0.3378 | [0.3048, 0.3707] | <0.001 |

| COCO–F1@50 vs. without–F1@50 | −0.1718 | [−0.2047, −0.1388] | <0.001 |

| COCO–F1@50 vs. without–mAP@50 | +0.2286 | [0.1956, 0.2616] | <0.001 |

| COCO–mAP@50 vs. without–F1@50 | –0.5095 | [–0.5425, –0.4766] | <0.001 |

| COCO–mAP@50 vs. without–mAP@50 | –0.1092 | [–0.1421, –0.0762] | <0.001 |

| without–F1@50 vs. without–mAP@50 | +0.4004 | [0.3674, 0.4333] | <0.001 |

| Effect | Df | Sum of Squares | F | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weights | 1 | 0.05919 | 372.40 | |

| Metric | 1 | 0.40863 | 2570.83 | |

| Weights × Metric | 1 | 0.00294 | 18.49 | 0.0026 |

| Residual | 8 | 0.00127 | - | - |

| Effect | Df | Sum of Squares | F | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dataset size | 1 | 0.005957 | 25.87 | 0.007050 |

| Metric | 1 | 0.305020 | 1324.65 | |

| Dataset size × Metric | 1 | 0.004905 | 21.30 | 0.009914 |

| Residual | 4 | 0.000921 | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Steindl, G.; Baca, A.; Kornfeind, P. Influences and Training Strategies for Effective Object Detection in Challenging Environments Using YOLO NAS-L. Sensors 2026, 26, 190. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010190

Steindl G, Baca A, Kornfeind P. Influences and Training Strategies for Effective Object Detection in Challenging Environments Using YOLO NAS-L. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):190. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010190

Chicago/Turabian StyleSteindl, Gerald, Arnold Baca, and Philipp Kornfeind. 2026. "Influences and Training Strategies for Effective Object Detection in Challenging Environments Using YOLO NAS-L" Sensors 26, no. 1: 190. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010190

APA StyleSteindl, G., Baca, A., & Kornfeind, P. (2026). Influences and Training Strategies for Effective Object Detection in Challenging Environments Using YOLO NAS-L. Sensors, 26(1), 190. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010190