1. Introduction

Continental surface water bodies, such as rivers, lakes, reservoirs, and streams, are essential sources of potable water and support multiple uses, including recreation, industry, agriculture, energy generation, transportation, and fishing [

1,

2]. They also play a fundamental role in maintaining biodiversity and regulating hydrological flow [

3]. Therefore, continuous monitoring of water quantity and quality is crucial for understanding natural and anthropogenic processes that influence aquatic systems and for supporting conservation actions [

4].

Conventional monitoring of water quality, based on discrete point sampling, presents important limitations, especially during extreme events. Low sampling frequency and the limited spatial distribution of monitoring stations hinder the detection of spatiotemporal variability in water quality, particularly along lake and reservoir margins or following intense rainfall [

5,

6]. In such situations, continuous and spatially detailed monitoring becomes essential to complement traditional approaches and to more accurately assess the impacts of events such as dam failures and heavy precipitation.

Remote sensing techniques have emerged as effective alternatives for the continuous monitoring of optically active water quality parameters because of their broad spatial coverage, adequate temporal resolution, and favorable cost–benefit ratio. These techniques have been widely applied to estimate chlorophyll-a (Chla), turbidity (T), colored dissolved organic matter (CDOM), total suspended solids (TSS), and Secchi disk depth (SDD) [

7,

8,

9,

10].

In contrast, relatively few studies have focused on predicting non-optically active parameters such as phosphorus (P), nitrogen (N), chemical oxygen demand (COD), dis-solved oxygen (DO), and iron (Fe) [

11,

12]. These parameters exhibit weak or no relation-ships with spectral bands, which limits their direct detection by orbital sensors [

13,

14,

15]. Consequently, their prediction relies on indirect approaches that explore correlations with optically active parameters, environmental variables, and machine-learning algorithms [

12,

16,

17].

Machine-learning algorithms have become increasingly prominent in water-quality modeling due to their ability to represent highly nonlinear relationships among environmental variables [

18]. These methods have been applied across a variety of monitoring contexts, often outperforming traditional approaches for several water-quality parameters [

19,

20]. Recent studies, for example, demonstrate that backpropagation neural networks can accurately estimate indicators such as chemical oxygen demand (COD), permanganate index, total nitrogen (TN), and total phosphorus (TP) [

21,

22]. In addition to neural networks, techniques such as decision trees, support vector machines, random forests, and other supervised learning algorithms have shown broad applicability in aquatic systems [

12,

17,

23,

24].

These methodological limitations are compounded by constraints inherent to current orbital platforms such as Landsat, MODIS, and Sentinel-2 (S2), which have moderate-to-low spatial resolutions ranging from 10 to 1000 m. Furthermore, the temporal resolutions of Landsat and S2A/2B satellites are considered moderate—16 and 10 days, respectively [

25,

26]. As a result, their application for remote detection of water quality in small reservoirs, embayments of large reservoirs, and narrow rivers—where higher-frequency imagery is needed—is limited [

27,

28].

To overcome such limitations, Planet has deployed a large number of nanosatellites known as Doves. These Doves form a CubeSat 3U (10 × 10 × 30 cm) constellation capable of daily revisit to the same target on Earth′s surface. Since 2016, these satellites have provided imagery with 3.7 m spatial resolution and four spectral bands (B1—Blue: 420–530 nm; B2—Green: 500–590 nm; B3—Red: 610–700 nm; and B4—near-infrared [NIR]: 780–860 nm) [

29]. They weigh approximately 4 kg, enabling much faster production and launch compared with traditional satellites. They also do not require a dedicated launch vehicle, as they can be delivered to orbit as secondary payloads [

30].

Recognizing these methodological gaps in the literature, this study offers an innovative contribution by integrating the prediction of optically active and inactive water-quality parameters in both lotic and lentic environments, an aspect that remains underexplored, particularly in highly variable contexts such as post-disaster conditions. This approach is strengthened by the inclusion of systematic comparisons among different orbital products, including Sentinel-2, PlanetScope, and radiometrically normalized PlanetScope, which enables the assessment of model predictive performance and the relevance of the specific characteristics of each orbital dataset. Accordingly, the objective of this study is to propose a methodology for predicting optically active and inactive water-quality parameters in lotic and lentic environments using remote-sensing data and machine-learning techniques.

3. Results and Discussion

Table 5 presents the descriptive statistics of the water quality parameters used in this study, revealing large gaps between minimum and maximum values—i.e., a wide range in the observed measurements. In addition, the parameter means are generally closer to the minima, indicating right-skewed distributions with long upper tails. Such skewness is common in environmental datasets, where measurements cluster at low to moderate levels but rare extreme events stretch the upper tail [

105].

Figure 3 ranks the most important covariates for the models used to predict water quality parameters across the three datasets (S2, PS, and normalized PS). Covariate-selection procedures substantially reduced the number of predictors, from an initial 151 to ten variables per model—an adequate and parsimonious set for modeling. These findings agree with Muñoz-Romero et al. [

70] and Stevens et al. [

76], who showed that reducing model complexity lowers computational costs and improves robustness and predictive performance.

Except for the NIR bands (B8 for S2 and B4 for PS), indices and band ratios dominate as the most important covariates compared with individual bands. This corroborates Sestini [

107] and Lillesand, Kiefer, and Chipman [

108], who showed that combining spectral bands via indices and ratios enhances discrimination of subtle spectral differences among targets, whereas individual bands tend to capture only more evident variations—making ratio-based indices more effective for identifying specific spectral features of natural objects or phenomena.

The NIR bands (B8 in Sentinel-2 and B4 in PlanetScope) stand out as the most influential predictors. This result is expected, since NIR reflectance responds strongly to increases in suspended particles, directly influencing the prediction of turbidity, TSS, and other optically active parameters. Even for optically inactive parameters, the NIR band provides indirect information because many chemical components are correlated with sedimentary and hydrodynamic processes, particularly in a post-disaster context where sediment mobilization is intensified.

Spectral indices and band ratios such as GLI, Iron, and NDTI also exhibit high importance. Their superior performance stems from their ability to highlight subtle variations in the water′s spectral response while reducing interference associated with illumination, solar geometry, and atmospheric variability. The Iron index, in particular, consistently appears among the most relevant predictors, reflecting the presence of mineral-rich particulate material that characterizes much of the sediment dynamics in the basin after the disaster. These indices provide a more stable and discriminative spectral signal than individual bands, contributing strongly to the prediction of optically active parameters and, indirectly, to optically inactive ones.

Precipitation-derived variables from the CHIRPS product also appear consistently among the ten most important predictors across all sensors. This behavior reflects the direct relationship between accumulated rainfall, increased surface runoff, sediment transport, and nutrient loading. Precipitation further exerts strong influence on sediment resuspension, especially in lotic environments, altering the optical properties of the water column and, consequently, the spectral response captured by the sensors. In reservoirs, these effects are more attenuated due to longer residence times and lower hydrodynamic energy, which explains the differences observed in model performance between lotic and lentic systems.

In addition to these direct effects on optically active parameters, precipitation also contributes to the prediction of optically inactive parameters through indirect relationships. Rainfall events intensify hydrological processes that mobilize organic matter, nutrients, and sediments, thereby altering optical variables such as turbidity, TSS, and indices sensitive to particulate material. Although these inactive parameters do not exhibit distinct spectral signatures, their variations are associated with these processes, enabling machine-learning models to estimate them indirectly.

Table 6 reports, for MSI/S2 data, the performance metrics for the machine-learning models used to predict water quality parameters in the Paraopeba River Basin.

The results demonstrate the superior robustness of tree-based algorithms, particularly RF and Cubist, when compared with KKNN and SVM-RBF. RF achieved the highest performance for five of the eight parameters, while Cubist ranked within the top two for six parameters. Both models produced the lowest prediction errors (RMSE and MAE) and the highest R

2 and CCC values, reinforcing the ability of tree-based methods to represent nonlinear relationships and capture multiscale interactions among environmental and hydrological covariates [

81]. These findings align with previous studies that emphasize the adaptability of ensemble-based approaches under conditions of high optical and hydrological heterogeneity [

104,

109,

110].

At the parameter level, Turbidity and TSS exhibited the strongest generalization capacity, with CCC values close to 0.82 and 0.72 and R2 values ranging from 0.75 to 0.59, accompanied by low RMSE and MAE. Both variables are optically active and strongly governed by suspended-sediment dynamics, which enhances their detectability across multisensor imagery. In contrast, Fe, P, DO, COD, and N showed limited predictive performance (CCC ≈ 0.44–0.31; R2 ≈ 0.27–0.15), reflecting their weak or indirect spectral signatures and their sensitivity to short-term hydrological fluctuations. For Chla, all algorithms performed poorly; even the best model (SVM-RBF; CCC = 0.12; R2 = 0.05) produced a test-set RMSE higher than the null model.

These results are consistent with the well-known physical–optical limitations of these parameters. DO, Nitrogen, and COD are not optically active and therefore do not exhibit direct spectral signatures detectable by orbital sensors. Their estimation relies on indirect relationships with covariates, which naturally limits model accuracy [

67]. In the case of Chla, although characteristic absorption bands exist, its detection in rivers is strongly hindered by low pigment concentrations, high turbidity, and spectral overlap with TSS and CDOM [

111,

112,

113]. These conditions are particularly relevant in the study area, where turbidity remains elevated due to the Brumadinho dam failure, reducing the effective optical depth and weakening the Chla signal.

Overall, there was no evidence of overfitting, as training and test results were concordant. Except for Chla, all parameters showed gains over the null model in RMSE and MAE: RMSE improvements ranged from 47.38% (T) to 6.75% (N); MAE improvements ranged from 61.12% (T) to 7.85% (N). For Chla, no advantage over the null model was observed for RMSE; however, MAE improved by 8.21%.

Table 7 reports, for PS data, the performance metrics for the machine-learning models used to predict water quality parameters in the Paraopeba River Basin.

Table 7 indicates a clear dominance of tree-based models, with Cubist and RF consistently ranking among the top two performers for all eight parameters derived from PS data. For Turbidity, TSS, Fe, and P, CCC values ranged from 0.878 to 0.513 and R

2 values from 0.796 to 0.337, accompanied by low RMSE and MAE. The close agreement between CCC and R

2 further reinforces the internal consistency and robustness of the modeling framework [

36].

The comparison of RMSE and MAE across training and test sets shows only minor discrepancies, suggesting a low risk of overfitting. As reported in

Table 7, RMSE values improved by 52.65 percent to 11.82 percent relative to the null model, while MAE improved by 66.04 percent to 13.82 percent. Similar to the MSI/S2 results, Chla was the only parameter for which the model did not outperform the null model, yielding an RMSE 9.85 percent below the mean and a marginal MAE improvement of 7.28 percent. This reinforces the known difficulty of retrieving Chla from PS imagery in highly turbid and optically complex environments.

Table 8 reports, for normalized PS data, the performance metrics used to evaluate the machine-learning models applied to predicting water quality parameters in the Paraopeba River Basin. For all evaluated parameters, RF and Cubist were among the two best models; only for Fe, P, and Chla did these algorithms perform worse than SVM-RBF and KKNN.

Analyzing model performance by parameter, the models for turbidity, TSS, Fe, P, and DO showed good generalization, with CCC values between 0.918 and 0.553. Corresponding R2 values ranged from 0.848 to 0.39. The strong agreement between these two indices is an important indicator of the robustness of the applied methodology.

When analyzing the RMSE and MAE indices, the results show low values and good agreement among the data. Examining the percentage gain of the developed models relative to the NULL RMSE and NULL MAE values, all evaluated parameters demonstrated real improvements, with gains ranging from 59.95% to 13.98% for RMSE. For MAE, the models showed an advantage between 68.77% and 15.04%.

Overall, with the exception of the Chla models derived from S2 and PS datasets, all developed models (

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8) achieved MAE and RMSE values lower than those of the null model, which constitutes the minimum statistical benchmark for acceptable predictive skill [

69,

85]. This systematic reduction in error metrics indicates that the proposed modeling framework provides a demonstrably superior predictive capability compared with the use of simple mean-based estimates.

The Chla parameter presented the lowest CCC and R

2 values, indicating significant difficulty for the algorithms to generalize across the three analyzed datasets. From an optical perspective, Chla is often affected by the presence of other Optically Active Components (OACs), such as TSS and colored dissolved organic matter (CDOM) [

111,

112,

113]. In this context, it is noteworthy that the study area was impacted by a mining tailings dam failure, which led to high TSS levels in the datasets used for modeling. This significantly contributed to the poor performance of the machine learning models in predicting the Chla parameter.

Additionally, the characteristics of the predominant soils in the region, classified by Embrapa [

114], as Red Latosols, Red-Yellow Latosols, Haplic Cambisols, and Humic Cambisols, directly influence water color and, consequently, its spectral response.

Table 9 presents the performance statistics of the best-performing machine learning models for each evaluated parameter under the three distinct approaches.

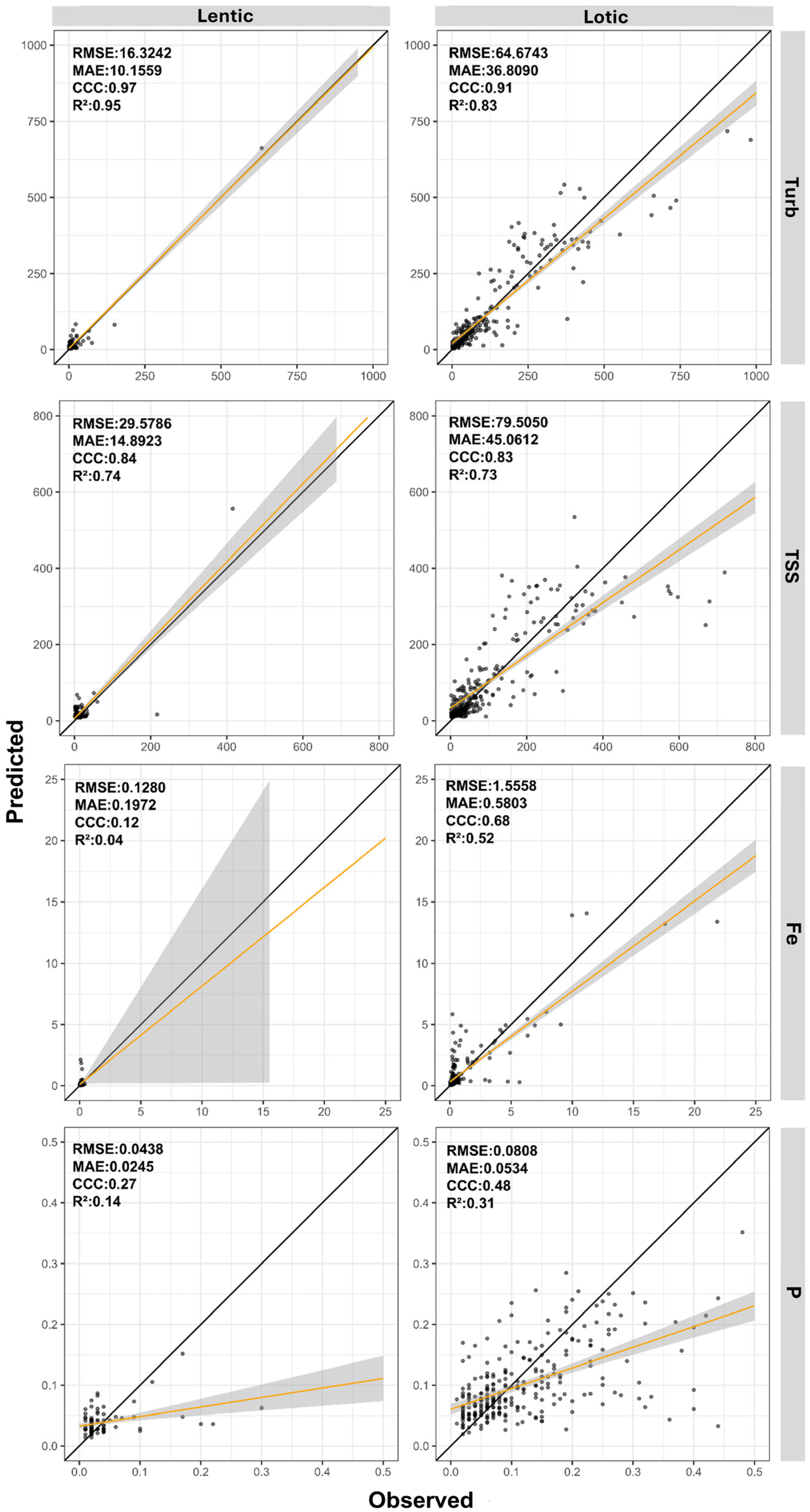

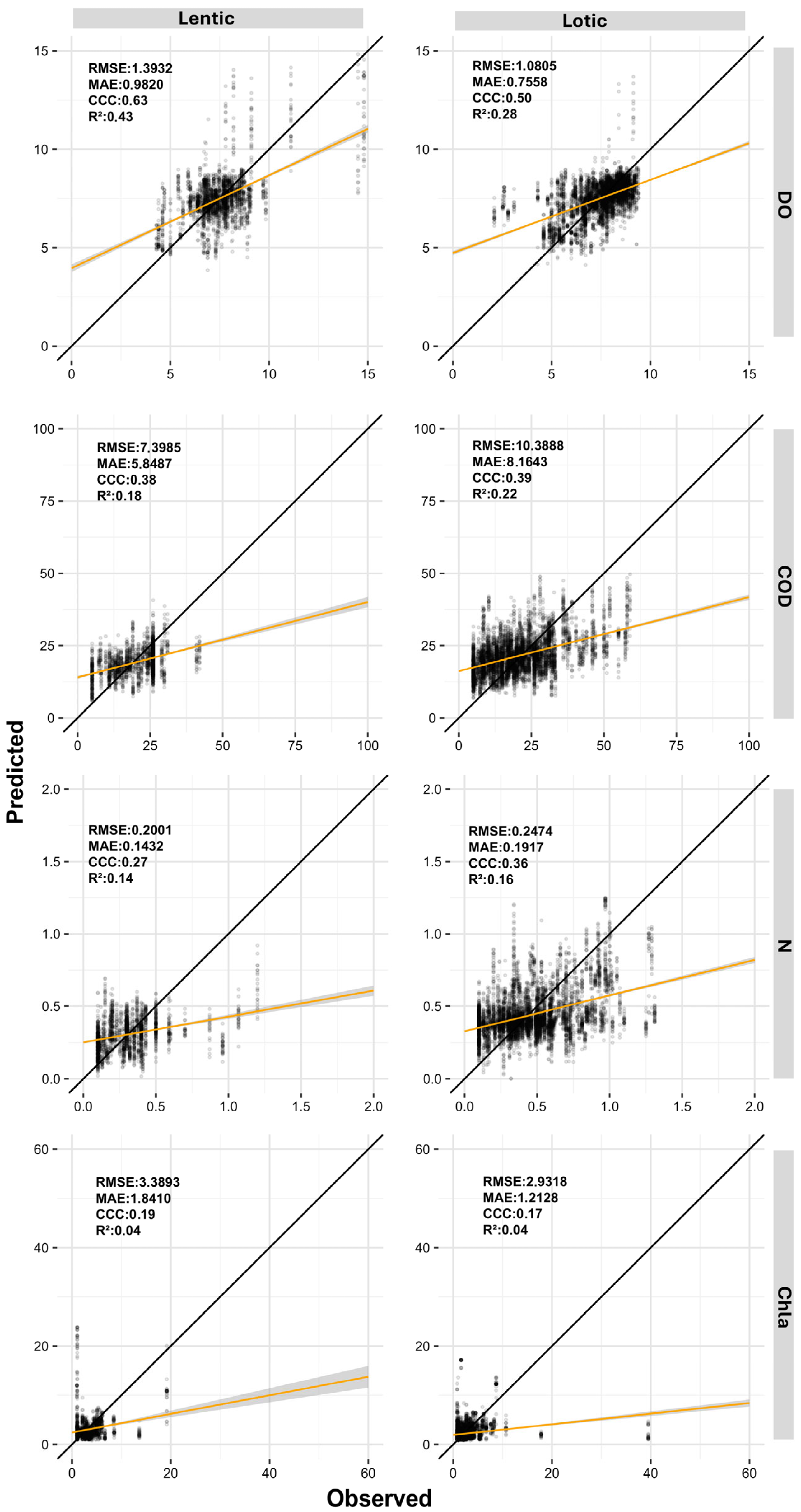

Figure 4 complements this information by displaying scatter plots of predicted versus observed values along a 1:1 line, allowing a visual assessment of prediction accuracy.

When analyzing

Table 9 and

Figure 4, the dataset derived from normalized PS images achieved the best results across all evaluated parameters. Models for turbidity, TSS, Fe, P, and DO presented CCC values between 0.92 and 0.55, while R

2 values ranged from 0.85 to 0.39. The MAE and RMSE values were lower than the thresholds established by the null models. For the parameters COD, N, and Chla, although the results were higher than those obtained with the other two datasets, the CCC values remained below 0.50, varying between 0.45 and 0.26, while R

2 ranged from 0.30 to 0.11.

These patterns and value magnitudes are consistent with the findings of Gao et al., [

115] who predicted non-optically active parameters using S2 data. These results are justified because the predictive capability arises from indirect relationships with optically active constituents and with short-term hydrological dynamics captured by the CHIRPS precipitation covariates. These factors co-vary due to sediment resuspension, nutrient transport, and seasonal changes in streamflow, allowing the models to identify nonlinear environmental patterns.

The results demonstrate the superior performance of the models developed using the PS dataset—both raw and normalized—compared with the S2 data across all analyzed parameters. This advantage arises directly from the characteristics of the PS sensor, such as its high spatial resolution (3.7 m), which enables the detection of finer-scale features, and its daily temporal resolution, which allows for a more accurate characterization of aquatic variability. These findings suggest that PS data offer significant advantages for water quality modeling, especially in complex aquatic systems where spatial and temporal variability is critical.

The MSI/S2 sensor, despite being widely used, has notable limitations in narrow water bodies (< 30 m wide), where its 10 m spatial resolution induces spectral mixing errors. Moreover, its reflectance is highly sensitive to external interferences (riverbed, riparian vegetation, and sediments), as reported by Barbosa et al. [

67], Greb et al. [

116], and Isidro et al. [

117], which reduces its accuracy in more complex aquatic systems.

In summary, when analyzing the characteristics of each sensor across the three evaluated datasets, the results indicate that the models developed using normalized PS data achieved the best performance, surpassing those based on raw PS and MSI/S2 data. This superior performance suggests that normalized PS data are more suitable for predicting water quality parameters, particularly turbidity, TSS, Fe, and P.

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 present the predicted and observed values of turbidity, TSS, Fe, P, DO, COD, N, and Chla parameters modeled using normalized PS data for lentic and lotic environments. Overall, due to environmental characteristics, lentic systems exhibited lower dispersion, with values closely grouped. In contrast, lotic environments displayed greater dispersion across all parameters.

Analyzing the statistical indices reveals that turbidity, TSS, COD, and N showed only minor variations in model performance between lentic and lotic environments. Conversely, Fe, P, DO, and Chla exhibited more pronounced differences between the two environments. In lentic systems, turbidity, TSS, and DO achieved the best performances, with CCC values ranging from 0.97 to 0.72 and R2 values between 0.95 and 0.65. Meanwhile, Fe, P, COD, N, and Chla had CCC values between 0.43 and 0.12 and R2 between 0.28 and 0.04. In lotic environments, turbidity, TSS, and Fe stood out, with CCC values ranging from 0.91 to 0.68 and R2 from 0.83 to 0.52. The parameters DO, P, COD, N, and Chla, however, displayed lower CCC and R2 values, ranging from 0.48 to 0.19 and 0.31 to 0.06, respectively.

The methodology proposed in this study proved robust for assessing water quality using a historical series of PS images. The comparative analysis between PS data and those from well-established constellation such as S2 demonstrated that PS imagery can provide valuable information despite its lower spectral resolution and the inherent radiometric differences among sensors. Although PS presents certain limitations, it shows strong potential for monitoring water-quality parameters in inland waters, particularly when radiometric normalization is applied. Normalization enhances radiometric consistency across different PS sensor generations (Dove Classic, Dove-R, and Super Dove), reducing calibration discrepancies and improving the temporal comparability of images acquired by different satellites. It also mitigates sensor-specific noise, including variations in gain, offset, and illumination, resulting in more stable and reliable spectral indices that are less susceptible to radiometric distortions.

The proposed methodology not only validates the use of PS data to predict water-quality parameters, but also offers relevant contributions to integrating different data sources to improve predictive accuracy. Based on the evidence presented, Planet′s nanosatellites are a promising tool for environmental monitoring, particularly in contexts that demand continuous, large-scale observations, opening new possibilities for water-resource management and for understanding environmental impacts.

It is important to emphasize that, although PS data stand out for their high spatial resolution and frequent temporal coverage, these images are not free, unlike those provided by the MSI/Sentinel-2 sensor. For this reason, the use of PS imagery requires a careful cost–benefit assessment to determine whether the financial investment is compatible with the monitoring objectives. In the context of this study, the use of PS data was made possible through the Planet Education and Research Program, which justified their inclusion in the analysis. However, in professional applications, the acquisition cost must be weighed against the specific requirements of each monitoring project, considering whether the advantages offered by PS outweigh the free alternative provided by S2.

However, MSI/S2 imagery also presents limitations, such as lower spatial resolution compared with PS, which may hinder the detection of small-scale targets or phenomena. In addition, frequent cloud cover and lower temporal revisit in some regions can limit the applicability of S2 data in studies that require both high spatial and temporal resolution.