Comparative Analysis of the Spatiotemporal Evolution Patterns of Acoustic Emission Source Localization Under True Triaxial Loading and Loading-Unloading Conditions in Sandstone

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. True Triaxial Unloading AE Monitoring Experiment

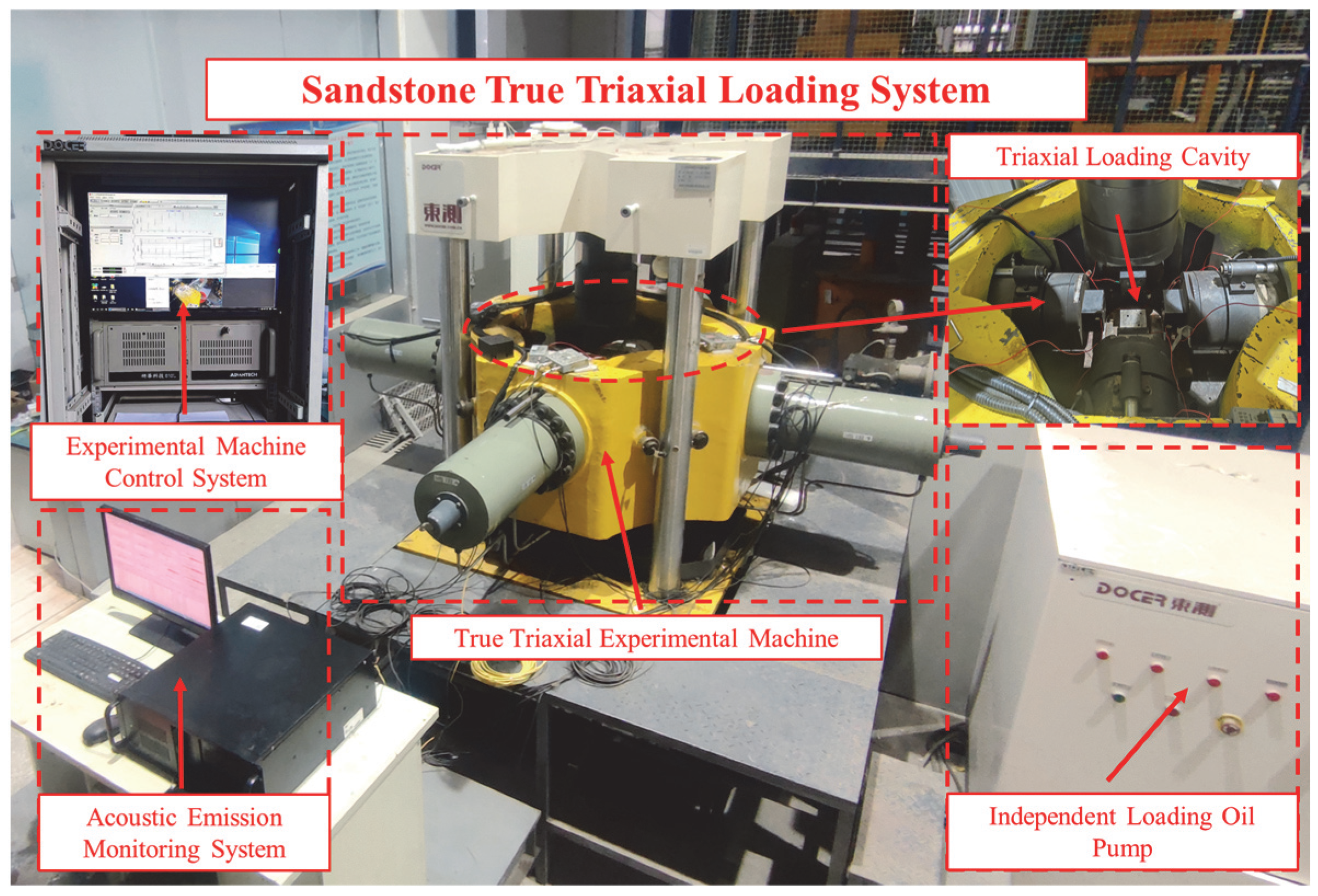

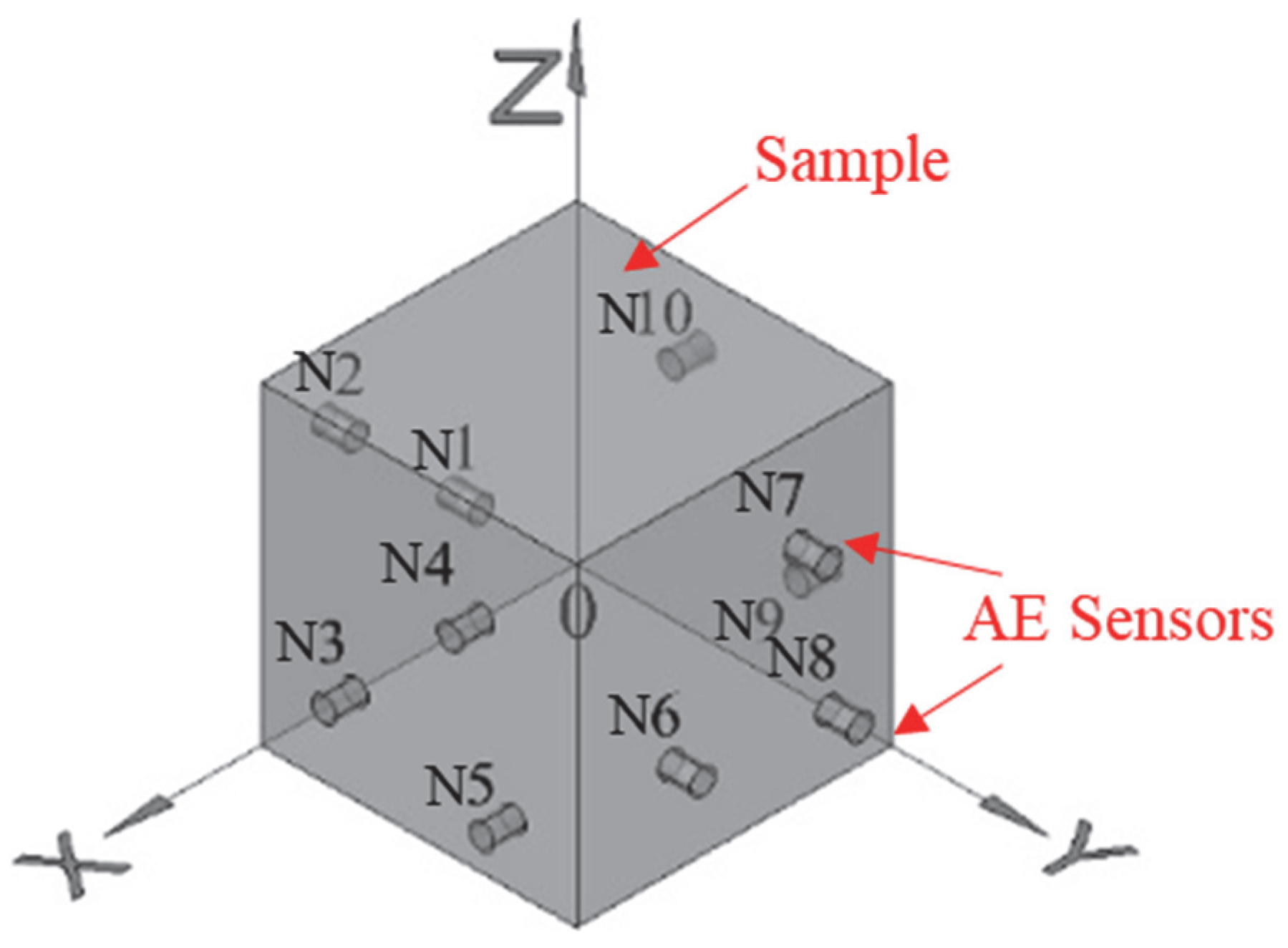

2.1. Experimental Equipment

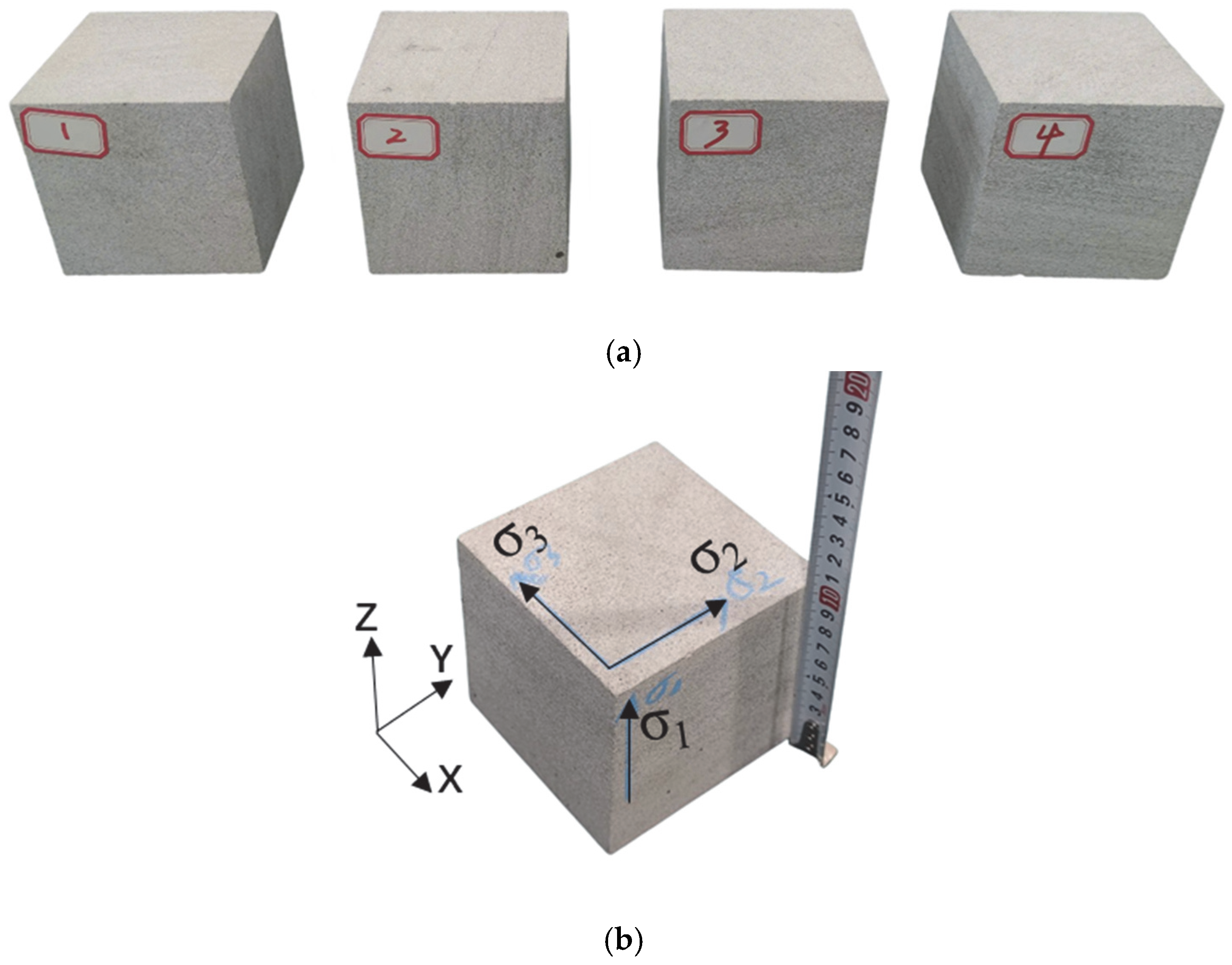

2.2. Sample Preparation

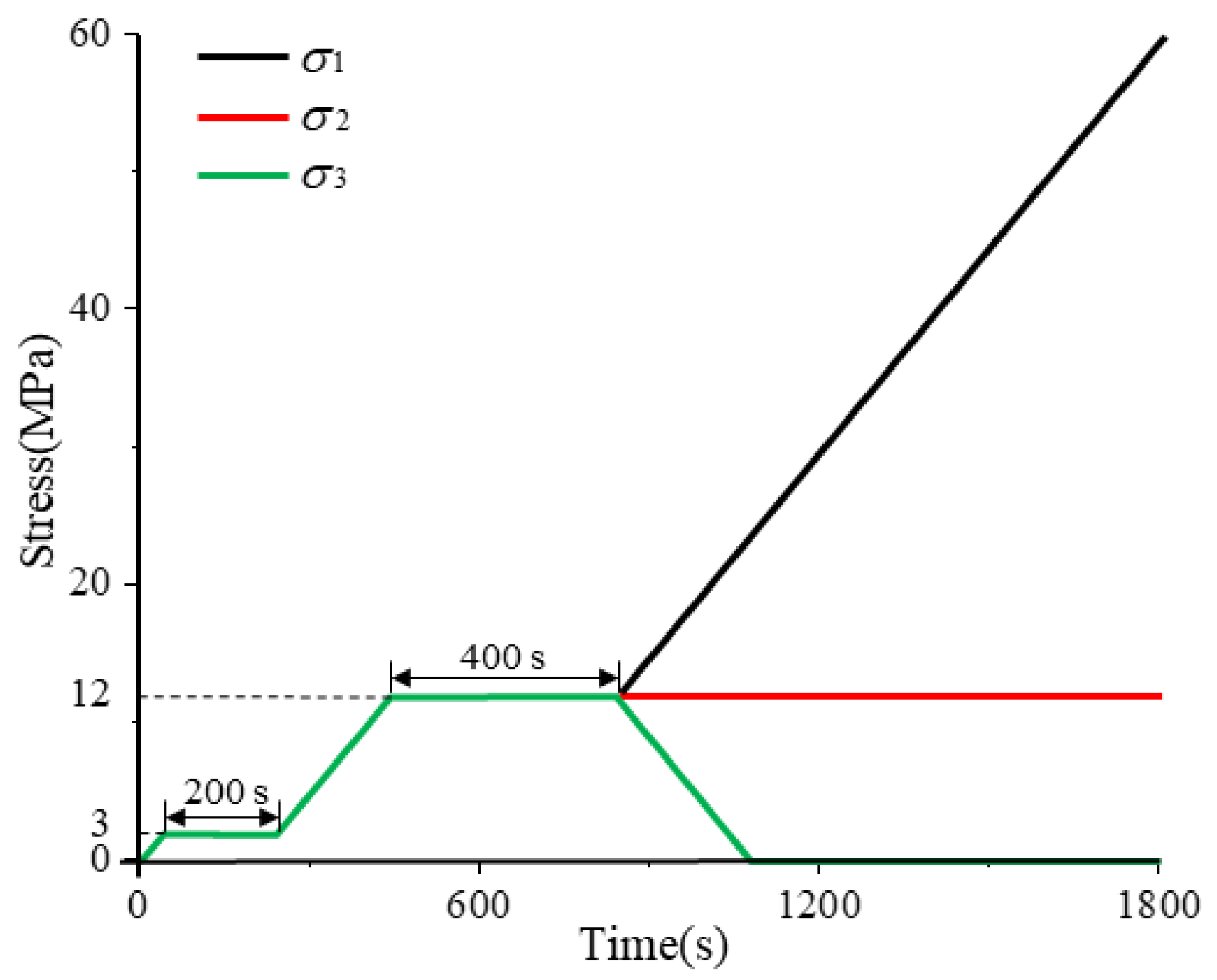

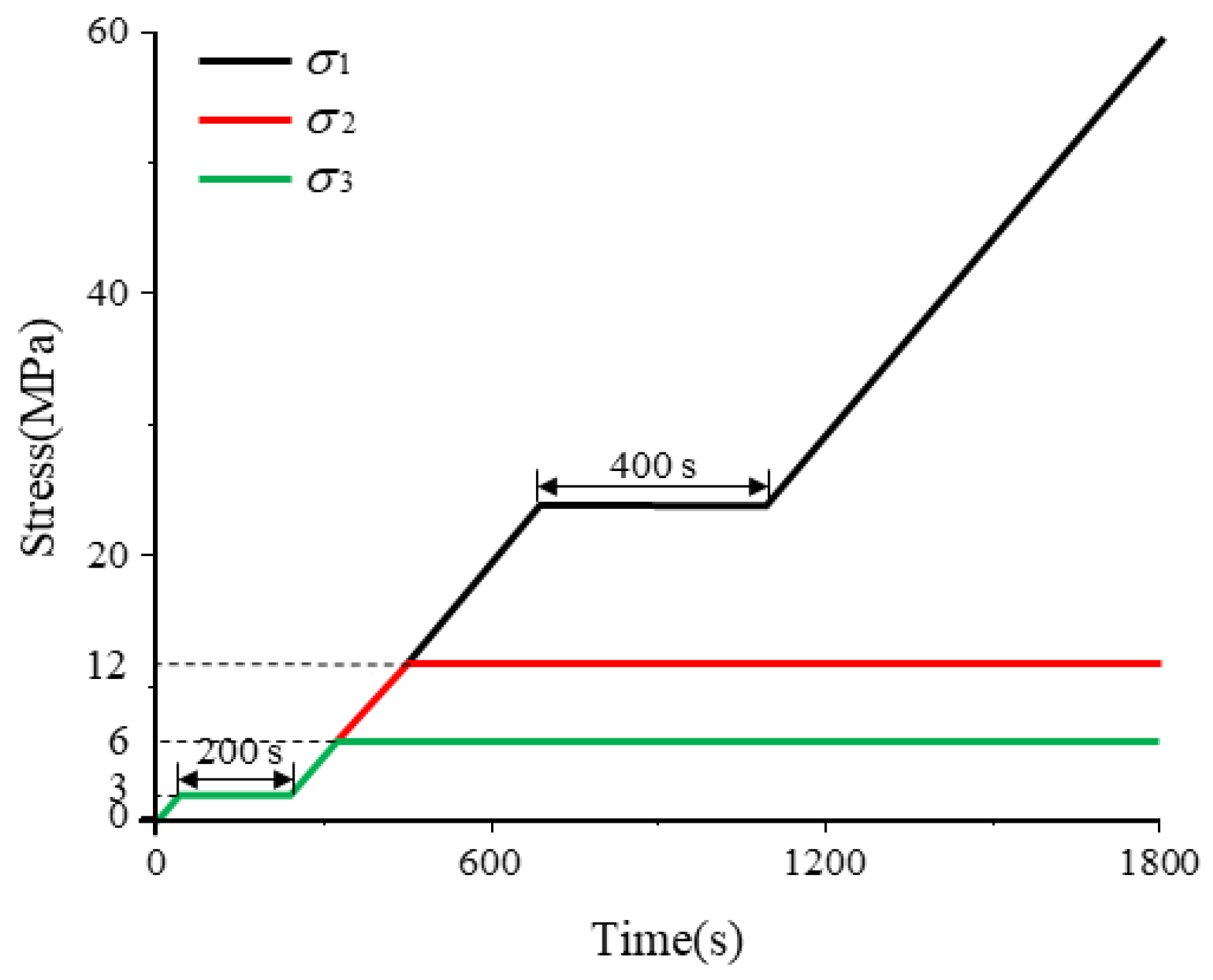

2.3. Experimental Scheme

3. Analysis of Experimental Results

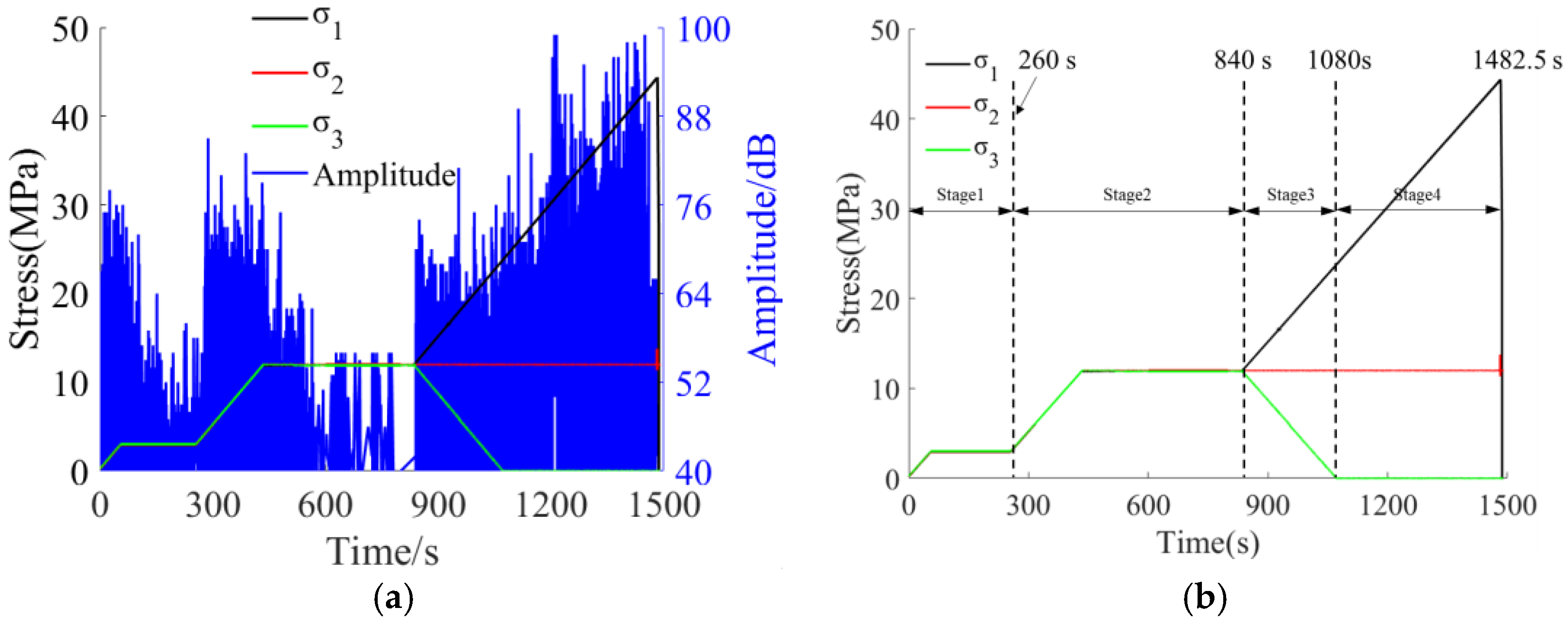

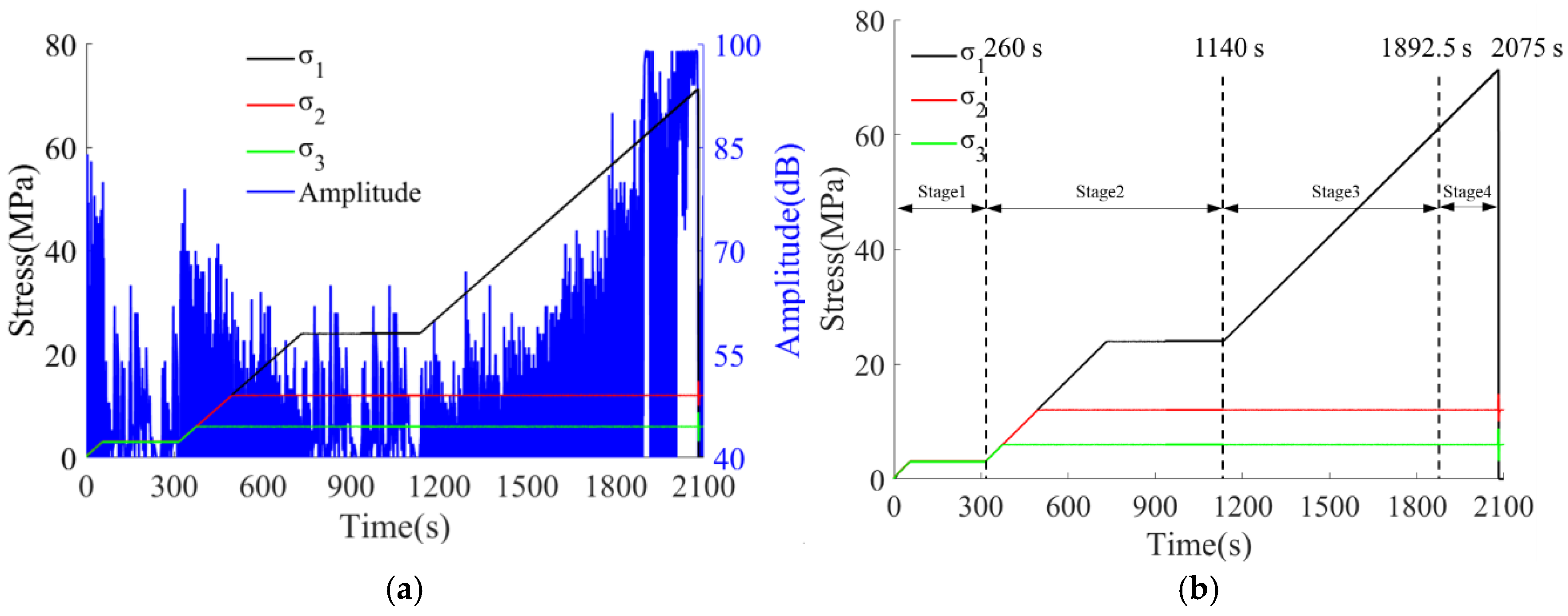

3.1. Time Domain Response Results of AE

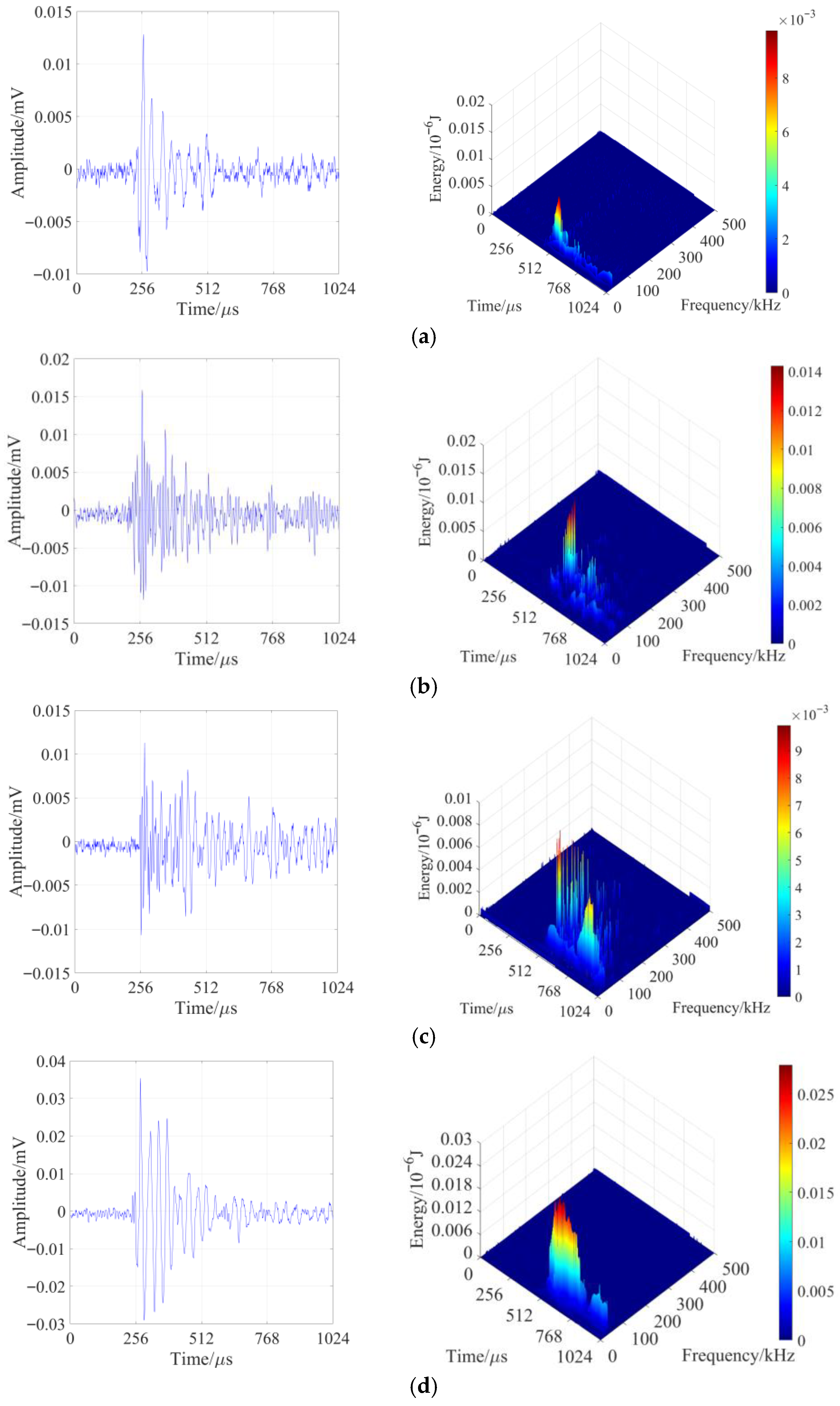

3.2. Time-Frequency Analysis of Typical Waveforms in the Loading-Unloading Process Based on Hilbert–Huang Transform (HHT)

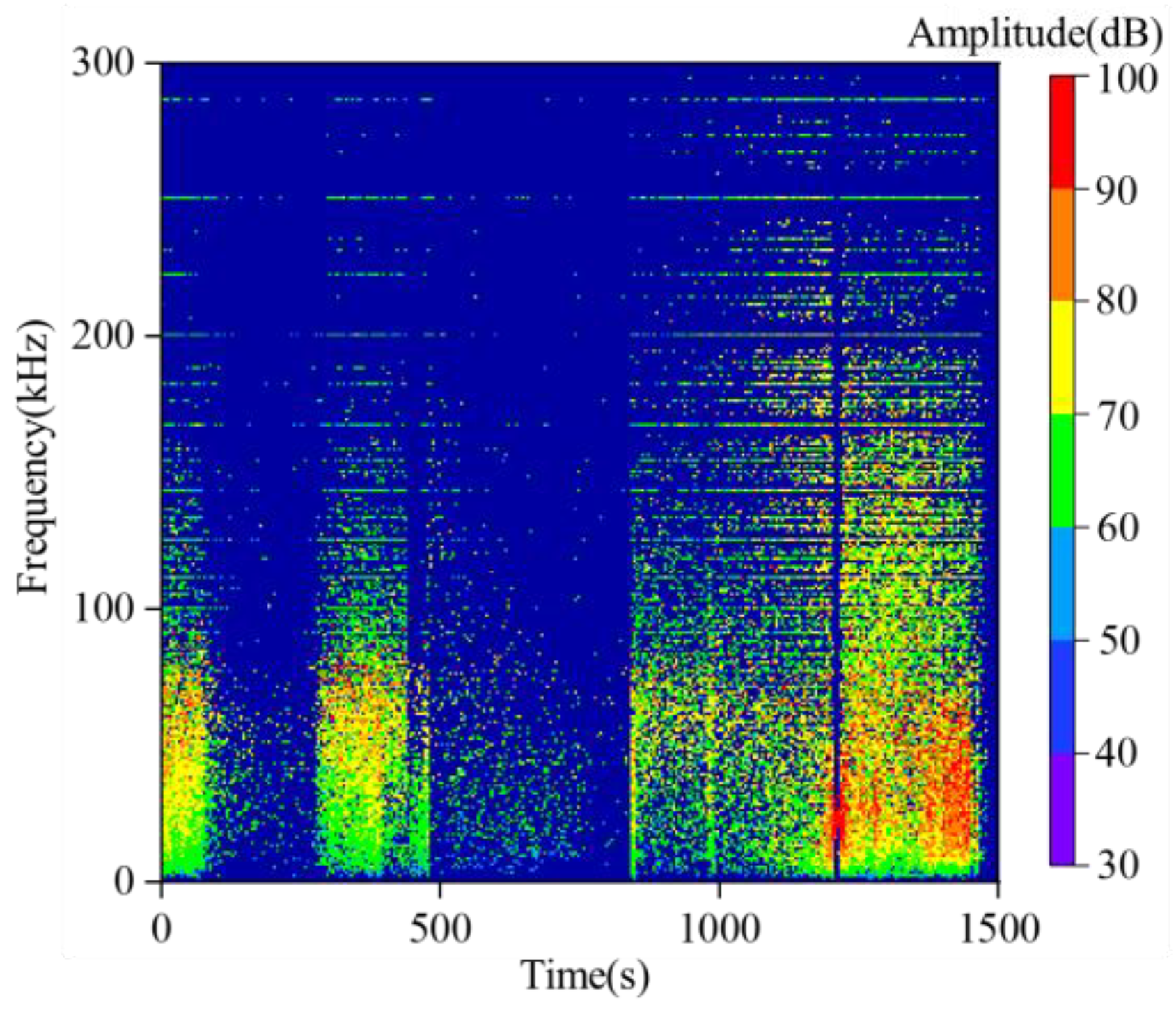

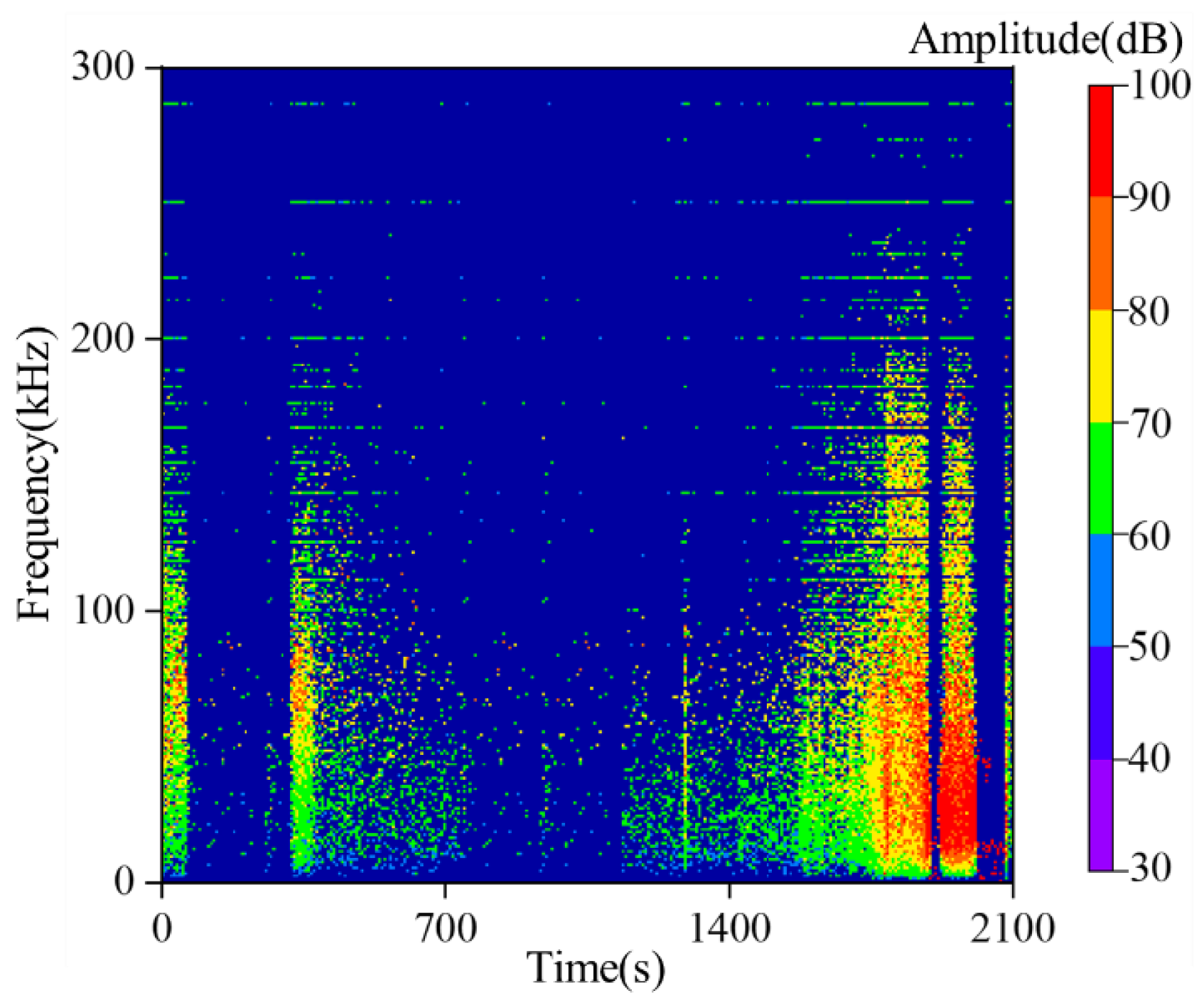

3.3. Results of Time-Frequency-Amplitude Response Throughout the Entire Experimental Process

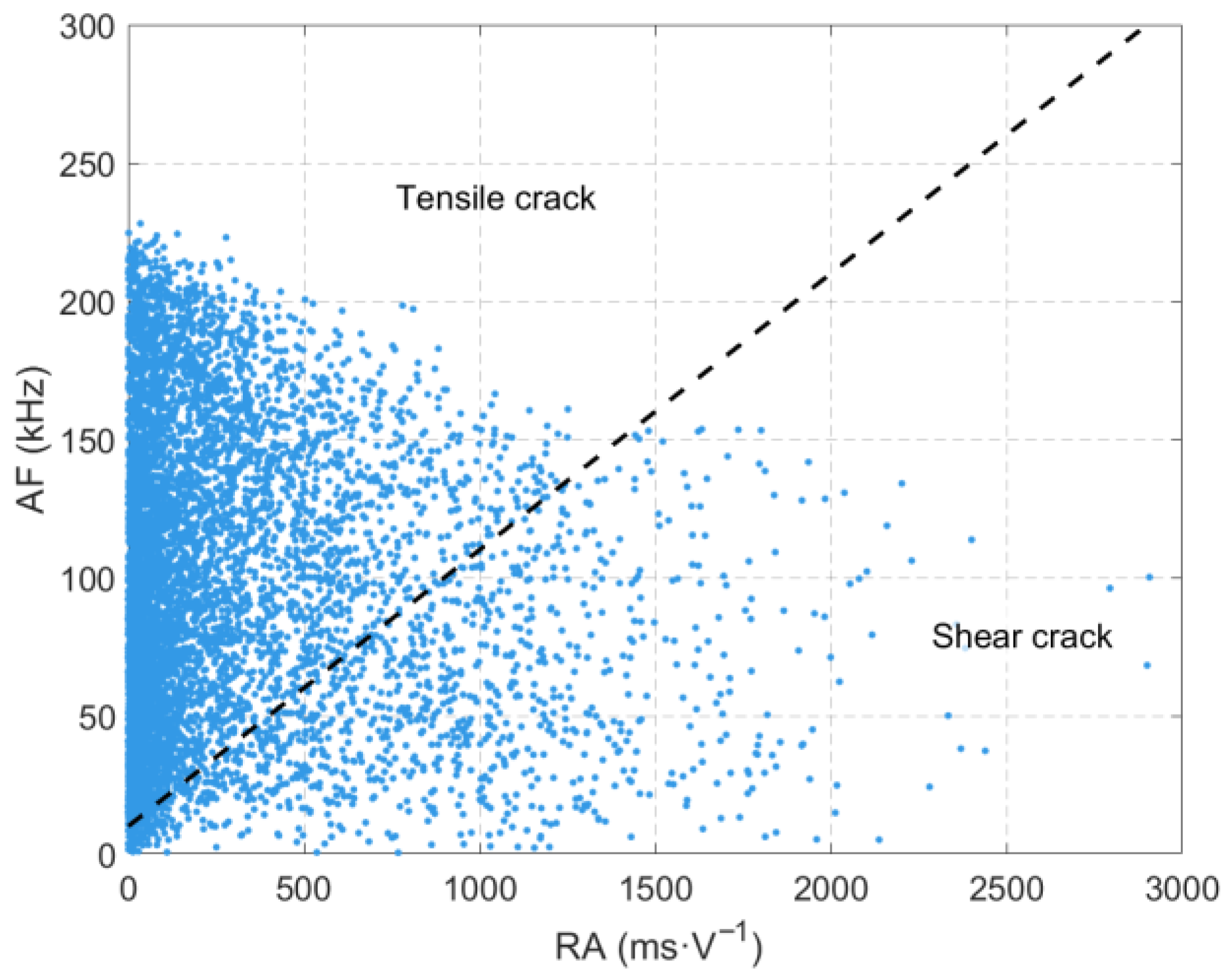

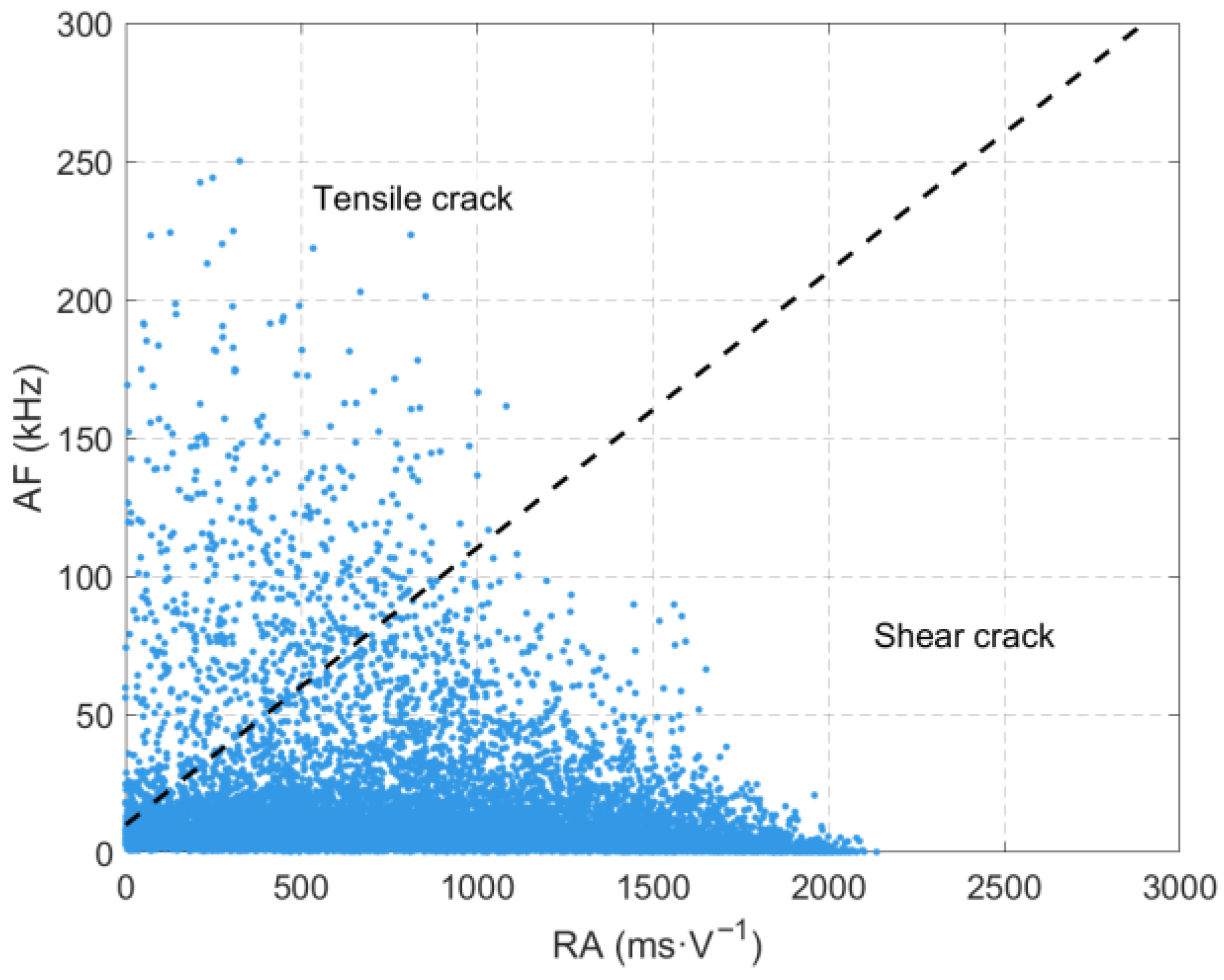

3.4. Analysis of RA-AF Values Throughout the Entire Experimental Process

4. Characteristics of the Spatiotemporal Evolution of AE Source Localization

4.1. Localization Accuracy Calibration

4.2. Analysis of Sandstone Failure Characteristics and Location Results

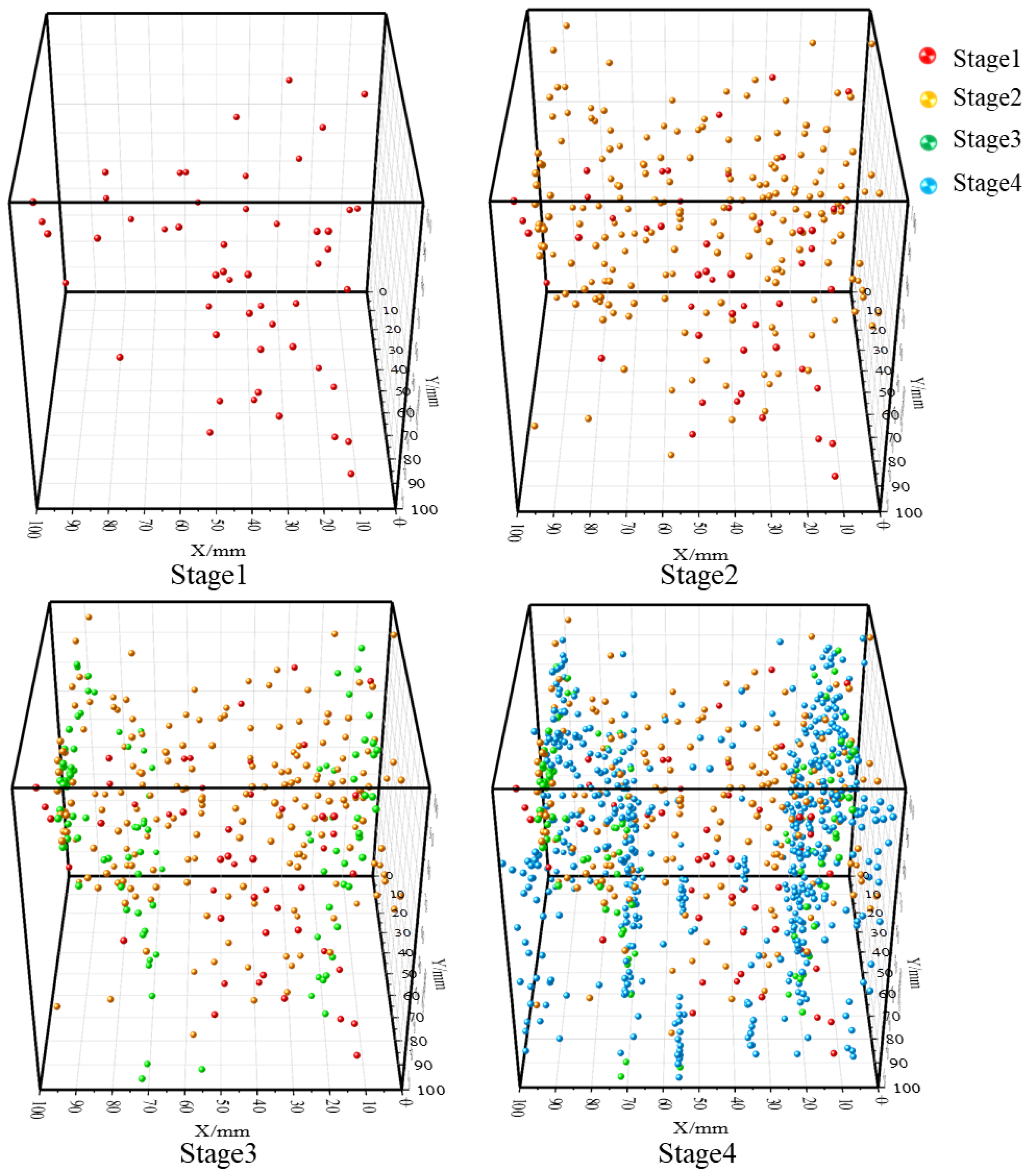

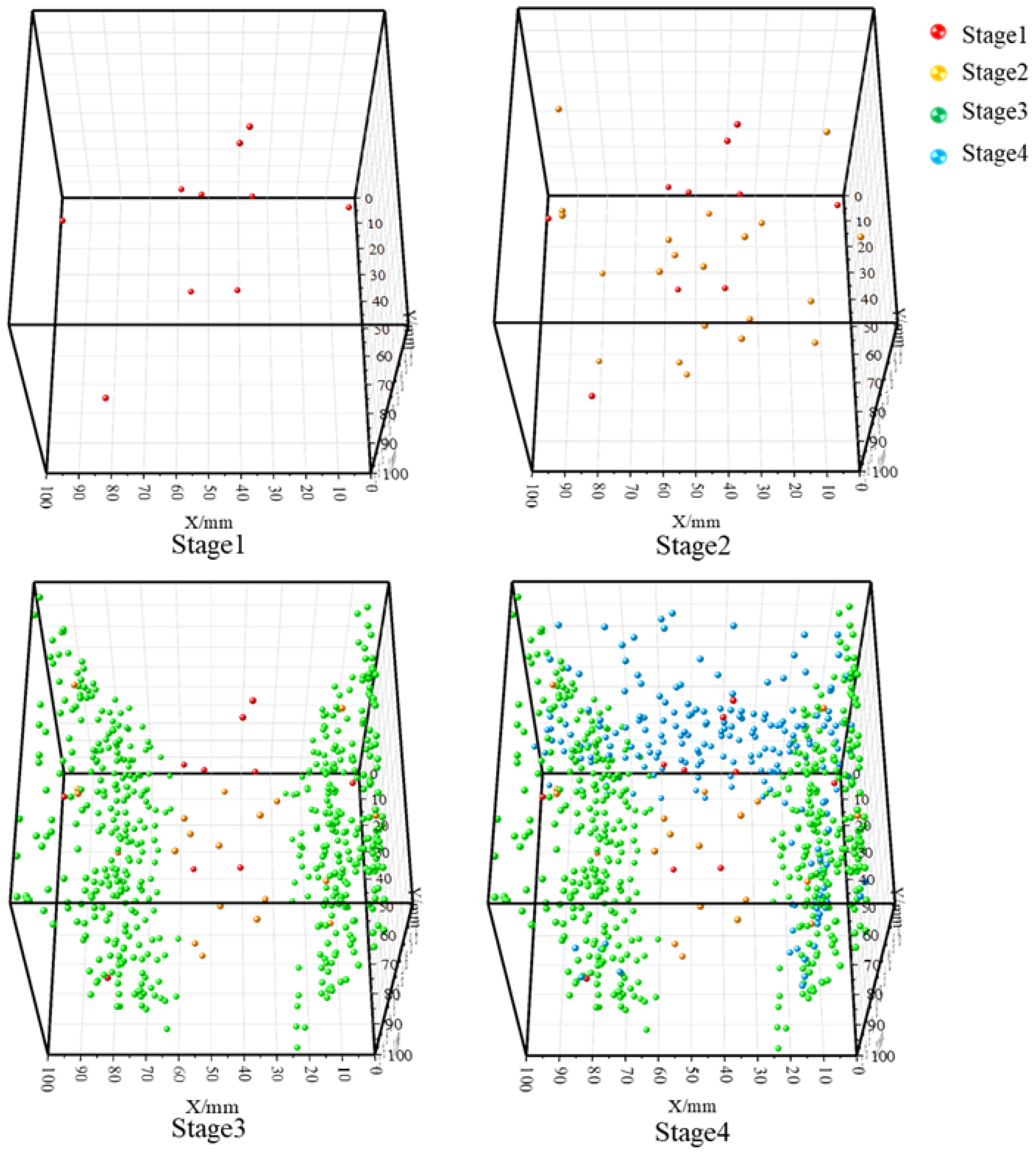

4.3. Characteristics of Spatial and Temporal Distribution in Each Stage of Positioning

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Both the true triaxial loading and loading-unloading failure processes of sandstone exhibit four-stage evolutionary characteristics, with significantly differentiated temporal variation laws of acoustic emission (AE) signals corresponding to each stage. During the preloading stage, the rock mass is compacted, resulting in active AE signals with high amplitudes. In the formal loading stage, signals tend to be sparse and low-amplitude. In the failure stage, both the number and amplitude of signals increase significantly. Among these stages, the increase in cumulative AE energy and counts during the failure stage under the loading-unloading path is far greater than that in the preloading and formal loading stages, and the unloading process can induce rock mass fracture in advance and enhance the AE response. In contrast, under the pure loading path, the signal increase in the first two stages is minimal, while it rises significantly in the failure stage.

- (2)

- The frequencies of AE waveforms during sandstone failure are concentrated in the range of 0–0.3 MHz, with dominant frequencies mainly distributed between 0 and 0.2 MHz. Amplitude peaks stably occur in the 0 MHz and 0.1 MHz frequency bands. High-amplitude waveforms correspond to the low-frequency range of 0–0.1 MHz, and their frequencies show a decreasing trend with increasing stress. Two low-frequency and high-amplitude regions are formed under the loading-unloading path, while only one such region appears under the pure loading path. There is no essential difference in the overall frequency distribution between the two paths.

- (3)

- The loading path significantly affects the source mechanism and crack evolution mode of sandstone. Under the loading-unloading path, the loading of the maximum principal stress (σ1) and lateral unloading of the minimum principal stress (σ3) in Stage 3 promote the development of tensile failure cracks in the rock mass. Continuous loading in Stage 4 leads to crack propagation and coalescence, forming a macroscopic fracture surface. In contrast, under the pure loading path, vertical loading in Stage 3 induces the initiation of compression-shear cracks inside the rock mass. After continuous loading, the shear cracks coalesce and extend to the surface in Stage 4.

- (4)

- The AE source location results have a good response relationship with the rock mass fracture process: during the preloading and formal loading stages, rock mass compaction only generates a small number of scattered location points; in the failure stage, a large number of concentrated location points appear, and these points are mostly clustered near fractures and fracture surfaces. This can effectively reflect the initiation, development process of cracks, and the propagation-coalescence characteristics of fracture surfaces.

- (5)

- This study can provide important theoretical support and a scientific basis for microseismic monitoring and early warning of deformation and failure of surrounding rock in deep mine tunnels. For the tunnel excavation stage, the initial triaxial isostatic stress balance of the surrounding rock is disrupted, and it is transformed into a complex stress environment characterized by vertical loading, radial unloading, and constant strike stress through loading-unloading effects. For the post-excavation stage, the stabilized surrounding rock behind the working face is disturbed by subsequent mining activities, forming a complex stress path of vertical secondary loading. A three-dimensional analysis platform integrating time-frequency parameters, location density, and damage evolution is established to automatically identify characteristic patterns such as low-frequency high-amplitude discrete signals and high-frequency dense signals, and realize a graded alarm combined with early warning thresholds. This study provides a theoretical basis for the microseismic monitoring and early warning technology of surrounding rock deformation and failure under the above two scenarios.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MS | Microseismic |

| AE | Acoustic emission |

References

- Yin, D.; Chen, S.; Ge, Y.; Liu, R. Mechanical properties of rock–coal bi-material samples with different lithologies under uniaxial loading. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 10, 322–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Ye, D.; Yang, P.; Wu, C. Study on Impact Tendency of Coal and Rock Mass Based on Different Stress Paths. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2020, 2020, 8883537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Yin, G.; Zhang, D.; Gao, H.; Li, B.; Li, M. True triaxial strength and failure characteristics of cubic coal and sandstone under different loading paths. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2020, 135, 104439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wang, E.; Zhou, R. Real-time measuring and warning of surrounding rock dynamic deformation and failure in deep roadway based on machine vision method. Measurement 2020, 149, 107028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Zhang, D.; Fang, Q.; Dui, G.; Tai, Q.; Sun, F. Analysis of the interaction between tunnel support and surrounding rock considering pre-reinforcement. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2021, 115, 104074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Sun, Q.; Feng, G.; Li, S.; Xiao, Y. In-situ observations of damage-fracture evolution in surrounding rock upon unloading in 2400-m-deep tunnels. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2023, 33, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R. Stability of surrounding rock in broken zone of the tunnel in rich water and mountains. Desalination Water Treat. 2023, 290, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Xia, C.; Xu, C.; Wang, C.; Zhao, H.; Maruvanchery, V.; Li, G. Precursory characteristics of coal-rock failure using acoustic emission and computed tomography under uniaxial monotonic and cyclic compression. Measurement 2025, 247, 116844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Xie, H.; Du, P. Acoustic Emission Characteristics of Coal Failure Under Triaxial Loading and Unloading Disturbance. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2022, 56, 1043–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Y.; Chen, J.; Apel, D.; Shang, X. Real-Time Identification of Rock Failure Stages Using Deep Learning: A Case Study of Acoustic Emission Analysis in Rock Engineering. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2025, 58, 5531–5547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombero, C.; Comina, C.; Vinciguerra, S.; Benson, P. Microseismicity of an Unstable Rock Mass: From Field Monitoring to Laboratory Testing. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2018, 15, 4210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Li, L.; Zhu, W.; Yang, T.; Tang, C.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, Y. Microseismic Investigation of Mining-Induced Brittle Fault Activation in a Chinese Coal Mine. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2019, 123, 104096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Hu, Q.; Yu, M.; Li, X.; Hu, J.; Yang, H. Acoustic Emission Monitoring Technology for Coal and Gas Outburst. Energy Sci. Eng. 2019, 15, 2990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Wang, Q. Rock Dynamics in Deep Mining. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2023, 33, 1065–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Zhou, X.; Xie, H.; Cai, D.; Gu, P. Stress-Induced AE Varying Characteristics in Distinct Lithologies Subjected to Uniaxial Compression. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2023, 286, 109226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Miao, J.; Feng, J. Rock Burst Process of Limestone and its Acoustic Emission Characteristics under True-Triaxial Unloading Conditions. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2010, 47, 286–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, F.; Gao, Z.; Ma, K.; Yang, S. Rockburst probability early warning method based on integrated infrared temperature and acoustic emission parameters. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2025, 189, 106097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, Y.; Wang, E.; Li, Z.; Liu, X.; Huang, T.; Yao, J. Comprehensive Early Warning Method of Microseismic, Acoustic Emission and Electromagnetic Radiation Signals of Rock Burst Based on Deep Learning. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2023, 170, 105519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Gao, C.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, D.; Liu, X.; Liang, X. Rock Burst Initiation and Precursors in a Model Specimen Based on Acoustic Emission and Infrared Monitoring. Arab. J. Geosci. 2022, 15, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.; Xie, H.; Ren, F.; Chang, Y. Rockburst Early-Warning Method Based on Time Series Prediction of Multiple Acoustic Emission Parameters. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2024, 153, 106060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, J. Micro-Crack Mechanism in the Fracture Evolution of Saturated Granite and Enlightenment to the Precursors of Instability. Sensors 2020, 20, 4595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.-C.; Chung, B.; Jung, D. A Proposed Algorithm Based on Variance to Effectively Estimate Crack Source Localization in Solids. Sensors 2024, 24, 6092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhao, C.; Huang, Y.; Lyu, G. Ground Pressure Control Measures and Microseismic Verification During the Recovery Process of Residual Ore Bodies. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, C.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, K.; Dong, L.; Sun, D. Optimization and Numerical Verification of Microseismic Monitoring Sensor Network in Underground Mining: A Case Study. Mathematics 2024, 12, 3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Fang, L.; Huang, B.; Chen, P.; Cai, C.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, Z.; Wen, Y.; Qin, Y. Characteristics of Acoustic Emission Waveforms Induced by Hydraulic Fracturing of Coal under True Triaxial Stress in a Laboratory-Scale Experiment. Minerals 2022, 12, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Tang, C.; Tang, S.; Kuang, L.; Yu, Q.; Kong, D.; Zhu, X. Rockburst Mechanism and Prediction Based on Microseismic Monitoring. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2018, 110, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, N.E.; Shen, Z.; Long, S.R.; Wu, M.C.; Shih, H.H.; Zheng, Q.; Yen, N.-C.; Tung, C.C.; Liu, H.H. The empirical mode decomposition and the Hilbert spectrum for nonlinear and non-stationary time series analysis. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 1998, 454, 903–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, M.E.; Colominas, M.A.; Schlotthauer, G.; Flandrin, P. A complete ensemble empirical mode decomposition with adaptive noise. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Prague, Czech Republic, 22–27 May 2011; pp. 4144–4147. [Google Scholar]

- Li, N.; Sun, W.; Huang, B.; Chen, D.; Zhang, S.; Yan, M. Acoustic Emission Source Location Monitoring of Laboratory-Scale Hydraulic Fracturing of Coal Under True Triaxial Stress. Nat. Resour. Res. 2021, 30, 2297–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoni, J. Fourier analysis and spectral estimation. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2017, 89, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Zhang, T.; Lim, E.; López-Benítez, M.; Ma, F.; Yu, L. A Review of Wavelet Analysis and Its Applications: Challenges and Opportunities. IEEE Access. 2022, 10, 58869–58903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E1106-12R21; Standard Test Method for Primary Calibration of Acoustic Emission Sensor. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

| Sensor Number | Coordinate (mm) | Sensor Number | Coordinate (mm) | Acquisition Parameters Setting | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | Y | Z | X | Y | Z | |||

| N 1 | 30 | 0 | 30 | N 6 | 70 | 100 | 30 | Threshold:40 dB Sampling frequency: 1000 kHz Sampling time: 1024 μs |

| N 2 | 70 | 0 | 70 | N 7 | 30 | 100 | 70 | |

| N 3 | 100 | 30 | 30 | N 8 | 20 | 100 | 20 | |

| N 4 | 100 | 70 | 70 | N 9 | 0 | 70 | 30 | |

| N 5 | 100 | 80 | 20 | N 10 | 0 | 30 | 70 | |

| Rock Type | Uniaxial Compressive Strength (UCS)/MPa | Elastic Modulus/GPa | Tensile Strength /MPa | Poisson’s Ratio /μ | Cohesion C /MPa | Internal Friction Angle/° |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sandstone | 22.687 | 3.099 | 2.751 | 0.157 | 8.063 | 39.83 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, P.; Yu, S.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; Li, N. Comparative Analysis of the Spatiotemporal Evolution Patterns of Acoustic Emission Source Localization Under True Triaxial Loading and Loading-Unloading Conditions in Sandstone. Sensors 2026, 26, 167. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010167

Chen P, Yu S, Wang H, Wang Z, Li N. Comparative Analysis of the Spatiotemporal Evolution Patterns of Acoustic Emission Source Localization Under True Triaxial Loading and Loading-Unloading Conditions in Sandstone. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):167. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010167

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Peng, Shibo Yu, Hui Wang, Zhixiu Wang, and Nan Li. 2026. "Comparative Analysis of the Spatiotemporal Evolution Patterns of Acoustic Emission Source Localization Under True Triaxial Loading and Loading-Unloading Conditions in Sandstone" Sensors 26, no. 1: 167. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010167

APA StyleChen, P., Yu, S., Wang, H., Wang, Z., & Li, N. (2026). Comparative Analysis of the Spatiotemporal Evolution Patterns of Acoustic Emission Source Localization Under True Triaxial Loading and Loading-Unloading Conditions in Sandstone. Sensors, 26(1), 167. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010167