Self-Powered Flexible Sensors: Recent Advances, Technological Breakthroughs, and Application Prospects

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Core Technology Pathways and Material Innovations for Self-Powered Sensors

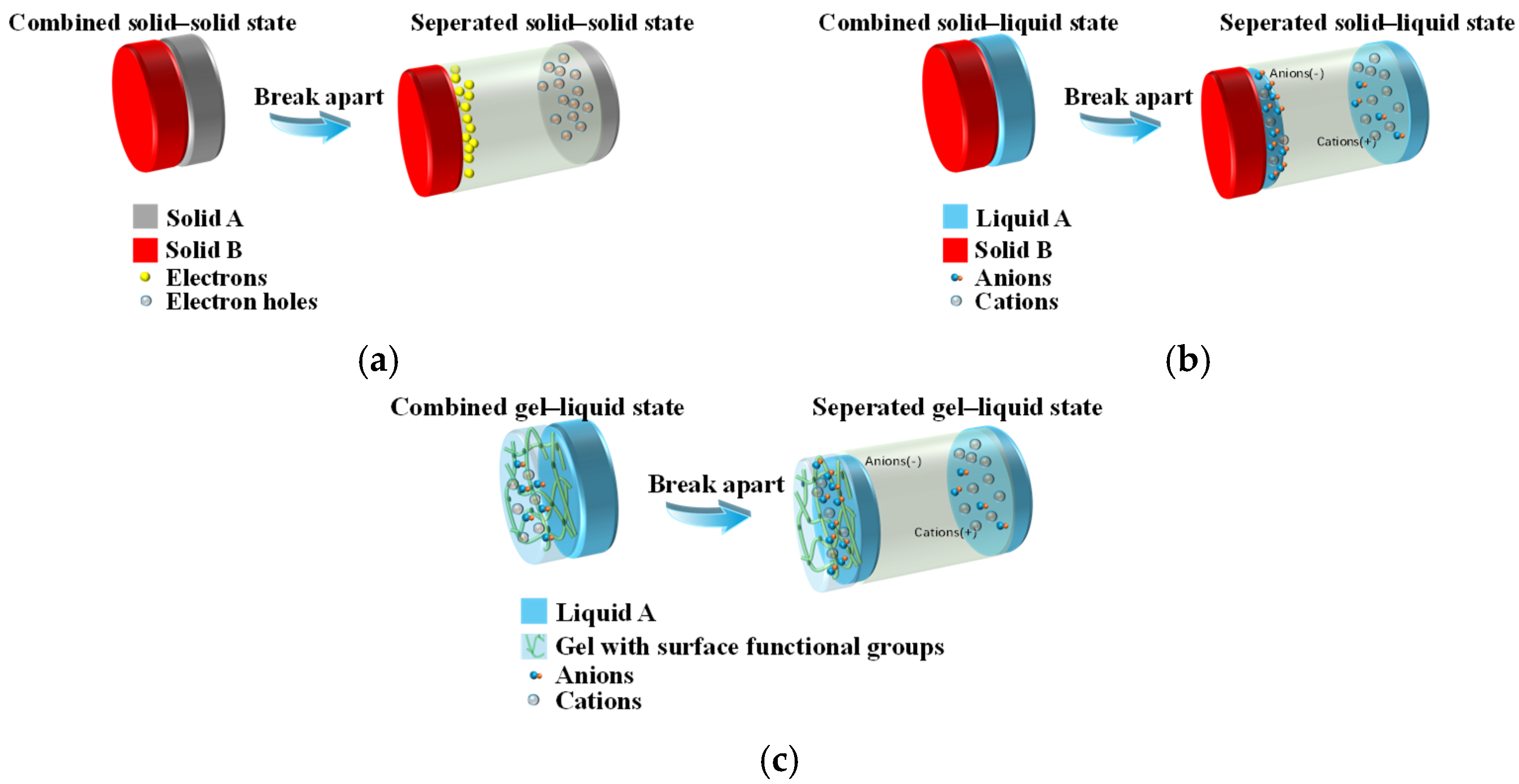

2.1. Triboelectric Nanogenerator-Based Sensor

- (1)

- Solid–solid contact separation-type TENG sensor

- (2)

- TENG sensor of the solid–liquid contact separation type

- (3)

- TENG sensor based on gel

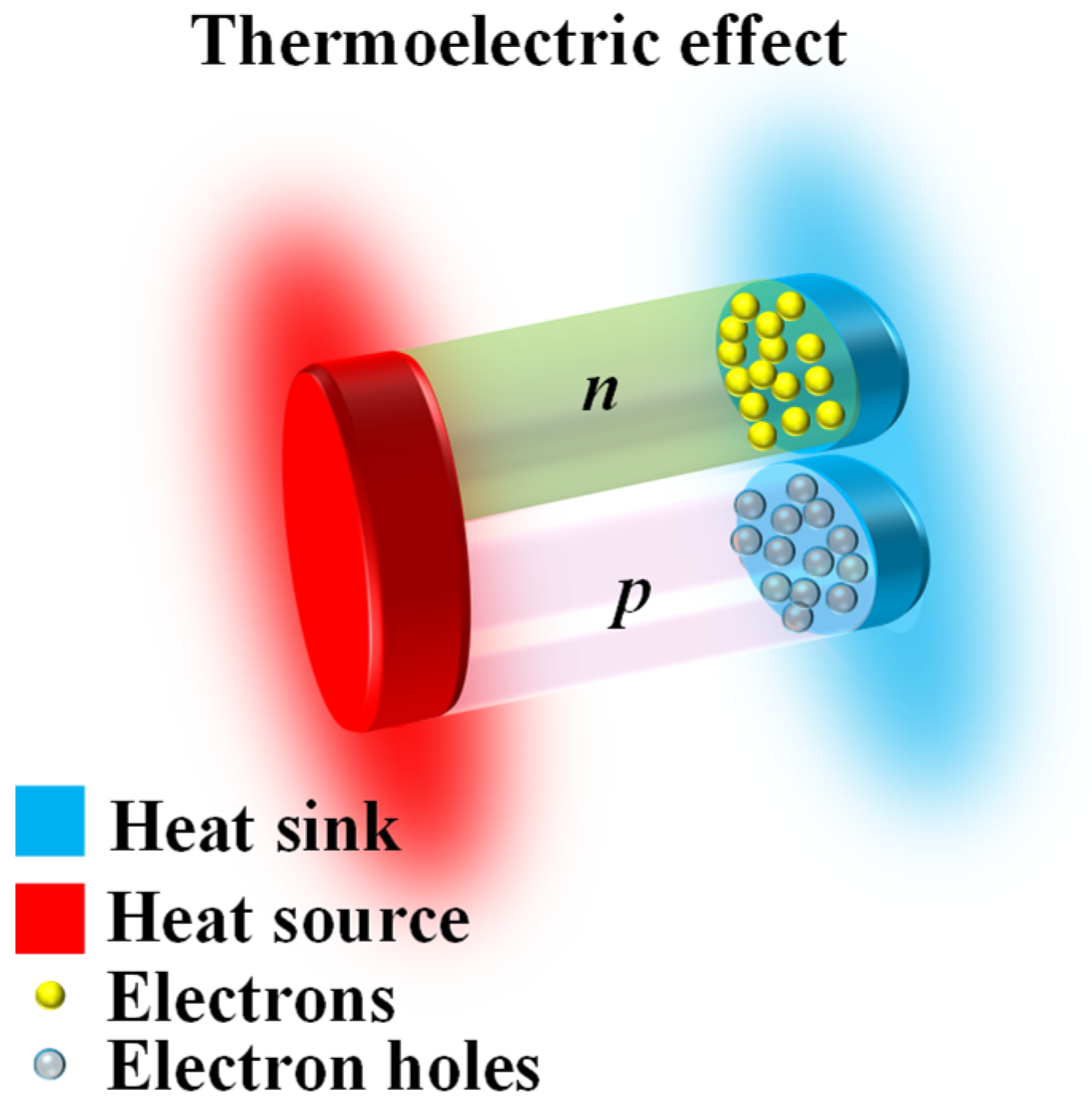

2.2. Thermoelectric-Based Sensor

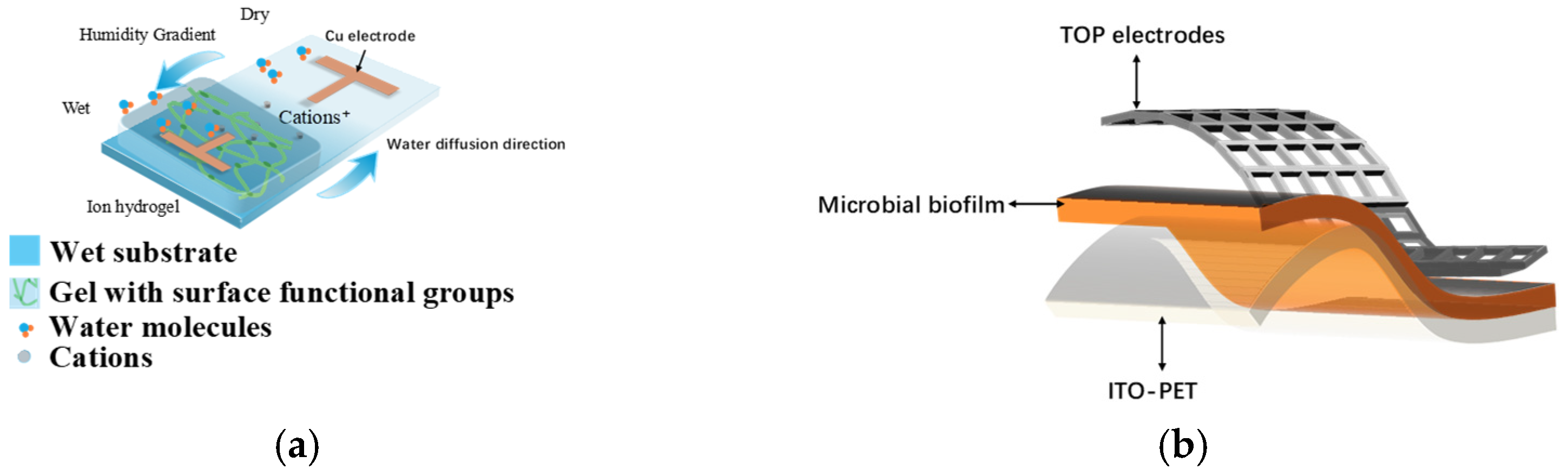

2.3. Hydrovoltaic Effect-Based Sensor

- (1)

- The Ion Migration Effect Driven by Humidity Gradient

- (2)

- Solid–liquid interface charge separation effect

- (3)

- Ion gradient pressure sensor

- (4)

- Ion gradient strain sensor

2.4. Piezoelectric-Based Sensor

2.5. Battery-Integrated Sensor

2.6. Photovoltaic-Based Sensors

2.7. Compatibility Relationship Between Materials and Sensor Types

3. Characteristics and Performance Evaluation of Self-Powered Sensors

3.1. Sensitivity and Detection Range

3.2. Stability in Cycles

3.3. Self-Powered Modes and Efficiency

4. Typical Application Scenarios of Self-Powered Sensors

4.1. Wearable Medical and Health Monitoring

4.2. Intelligent Robots and Human–Machine Interaction

4.3. Safety and Environmental Monitoring

4.4. Biomedical and Implantable Uses

5. Present Challenges and Future Prospects for Self-Powered Sensors

5.1. Present Challenges

5.2. Future Prospects

5.3. A Map of Research Achievements in Recent Years

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, S.; Jayaraman, A.; Rogers, J.A. Skin sensors are the future of health care. Nature 2019, 571, 319–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Feng, B.; Huo, J.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, W.; Peng, J.; Li, Z.; Du, C.; Wang, W. Artificial intelligence meets flexible sensors: Emerging smart flexible sensing systems driven by machine learning and artificial synapses. Nano-Micro Lett. 2023, 16, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Zhou, Q.; Bi, Y.; Cao, S.; Xia, X.; Yang, A.; Li, S.; Xiao, X. Research progress of flexible capacitive pressure sensor for sensitivity enhancement approaches. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2021, 321, 112425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wan, Z.; Zou, T.; Shen, Z.; Li, M.; Wang, C.; Xiao, X. Artificial intelligence enabled self-powered wireless sensing for smart industry. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 492, 152417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Ghannam, R.; Htet, K.O.; Liu, Y.; Law, M.-K.; Roy, V.A.L.; Michel, B.; Imran, M.A.; Heidari, H. Self-Powered implantable medical devices: Photovoltaic energy harvesting review. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2020, 9, 2000779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parrilla, M.; De Wael, K. Wearable self-powered electrochemical devices for continuous health management. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2107042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotovtsev, P.M.; Parunova, Y.M.; Antipova, C.G.; Badranova, G.U.; Grigoriev, T.E.; Boljshin, D.S.; Vishnevskaya, M.V.; Konov, E.A.; Lukanina, K.I.; Chvalun, S.N.; et al. Self-powered implantable biosensors: A review of recent advancements and future perspectives. In Macro, Micro, and Nano-Biosensors: Potential Applications and Possible Limitations; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 399–410. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatta, T.; Faruk, O.; Islam, M.R.; Kim, H.S.; Rana, S.S.; Pradhan, G.B.; Deo, A.; Kwon, D.-S.; Yoo, I.; Park, J.Y. Polymeric multilayered planar spring-based hybrid nanogenerator integrated with a self-powered vibration sensor for automotive vehicles IoT applications. Nano Energy 2024, 127, 109793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, X.; Hou, N.; Huang, S.; Yuan, T.; Wang, H.; Zhang, A.; Li, L.; Zhang, W. Ultra-thin self-powered sensor integration system with multiple charging modes in smart home applications. Mater. Today Nano 2023, 23, 100358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Sun, H.; Chu, Z.; Zhao, J.; Yang, Z.; Liu, S.; Wen, J.; Qin, Y. Self-powered and self-calibrated sensing system for real-time environmental monitoring. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadw3745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Market Research Future, Self Powered Sensor Market 2025, MRFR/SEM/35926-HCR. Available online: https://www.marketresearchfuture.com/reports/self-powered-sensor-market-37881#author (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Xiang, P.; Ma, L.; Li, M.; Liu, F.; Chen, X.; Huang, Z.; Xiao, X. Self-powered flexible wireless sensing for smart fishery. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 520, 165836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, S.; Spíchal, L.; Zbořil, R. Flying seed-inspired sensors for remote environmental monitoring on Earth and beyond. Trends Biotechnol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T. An Ultra-Low Power Communication Protocol for a Self-Powered Wireless Sensor Based Animal Monitoring System. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, NE, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ntawuzumunsi, E.; Kumaran, S.; Sibomana, L. Self-powered smart beehive monitoring and control system. Sensors 2021, 21, 3522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Guo, X.; Liu, W.; Lee, C. Recent progress in the energy harvesting technology—From self-powered sensors to self-sustained IoT, and new applications. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Wang, Y.; Tang, G.; Ru, J.; Zhu, Z.; Li, B.; Guo, C.; Li, L.; Zhu, D. Ionic flexible sensors: Mechanisms, materials, structures, and applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2110417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Li, X.; Shi, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, W.; He, L.; Liu, R. Recent Developments for Flexible Pressure Sensors: A Review. Micromachines 2018, 9, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Shen, M.; Cui, X.; Shao, Y.; Li, L.; Zhang, Y. Triboelectric Nanogenerator Based Self-powered Sensor for Artificial Intelligence. Nano Energy 2021, 84, 105887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.C.; Dai, Z.; Ma, H.; Zheng, J.; Leng, J.; Xie, C.; Yuan, Y.; Yang, W.; Yalikun, Y.; Song, X.; et al. Self-powered and speed-adjustable sensor for abyssal ocean current measurements based on triboelectric nanogenerators. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Lin, L.; Zhang, Y.; Jing, Q.; Hou, T.C.; Wang, Z.L. Self-powered magnetic sensor based on a triboelectric nanogenerator. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 10378–10383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowell, J.; Rose-Innes, A.C. Contact electrification. Adv. Phys. 1980, 29, 947–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Gao, Y.; Qiao, W.; Zhou, L.; He, L.; Ye, C.; Wang, J. Field emission effect in triboelectric nanogenerators. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Mei, Z.; Wang, T.; Huo, W.; Cui, S.; Liang, H.; Du, X. Flexible transparent high-voltage diodes for energy management in wearable electronics. Nano Energy 2017, 40, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.G.; Kim, D.W.; Tcho, I.W.; Kim, J.K.; Kim, M.S.; Choi, Y.K. Triboelectric nanogenerator: Structure, mechanism, and applications. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 258–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Qin, Y.; Xu, C.; Wei, Y.; Yang, R.; Wang, Z.L. Self-powered nanowire devices. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2010, 5, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, H.; Tian, J.; Sun, G.; Zou, Y.; Liu, Z.; Li, H.; Zhao, L.; Shi, B.; Fan, Y.; Fan, Y.; et al. Self-powered pulse sensor for antidiastole of cardiovascular disease. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1703456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, C.; Sun, P.; Sima, W.; Fang, Z.; Yuan, T.; Yang, M.; Liu, Q.; Wang, H.; Tang, W.; Xu, J.; et al. Bioinspired lotus leaf microstructure self-healing flexible sensor: Toward dynamic physiological signal monitoring and three-dimensional stress field decoupling. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 522, 167049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Meng, L.; Shi, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, J.; Sun, Q.; Liu, X.; Chen, J.; Liu, S. Morphological engineering of sensing materials for flexible pressure sensors and artificial intelligence applications. Nano-Micro Lett. 2022, 14, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, P.; Sahay, K.; Verma, A.; Maurya, D.K.; Yadav, B.C. Applications of multifunctional triboelectric nanogenerator (TENG) devices: Materials and prospects. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2023, 7, 3796–3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, H.; Zeng, Y.; Huang, X.; Wang, N.; Cao, X.; Wang, Z.L. From triboelectric nanogenerator to multifunctional triboelectric sensors: A chemical perspective toward the interface optimization and device integration. Small 2022, 18, 2107222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, X.; Zhu, L.; Wang, Y.C.; Li, J.; Nie, J.; Wang, Z.L. A flexible multifunctional triboelectric nanogenerator based on MXene/PVA hydrogel. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2104928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.C.; Hsiao, Y.C.; Wu, H.M.; Wang, Z. Waterproof fabric-based multifunctional triboelectric nanogenerator for universally harvesting energy from raindrops, wind, and human motions and as self-powered sensors. Adv. Sci. 2019, 6, 1801883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Lei, R.; Cao, J.; Chen, S.; Zhong, Y.; Song, J.; Jin, Z.; Cheng, G.; Ding, J. High-Sensitivity Flexible Self-Powered Pressure Sensor Based on Solid–Liquid Triboelectrification. ACS Sens. 2025, 10, 2347–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Guo, L.; Ding, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, C.; Che, L. Self-Powered Intelligent Water Droplet Monitoring Sensor Based on Solid–Liquid Triboelectric Nanogenerator. Sensors 2024, 24, 1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, K.; Chen, Z.; Yu, J.; Zeng, H.; Wu, J.; Wu, Z.; Jia, Q.; Li, P.; Fu, Y.; Chang, H.; et al. Ultra-sensitive, deformable, and transparent triboelectric tactile sensor based on micro-pyramid patterned ionic hydrogel for interactive human–machine interfaces. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2104168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Yang, X.; Wang, B.; Liu, J.; Yin, B.; Sang, W.; Leng, J.; Wen, Y.; Li, H.; Shen, X. Tough and Conductive Hydrogels Fabricated via Dehydration and Solvent Displacement as Flexible Strain Sensors and Self-Powered Devices. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2024, 6, 15269–15280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Duan, Z.; Wu, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Zhang, M.; Tai, H. Ion gradient induced self-powered flexible pressure sensor. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 490, 151660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Liao, X.; Guo, X.; Cai, C.; Liu, Y.; Chi, M.; Du, G.; Wei, Z.; Meng, X.; Nie, S. Gel-based triboelectric nanogenerators for flexible sensing: Principles, properties, and applications. Nano-Micro Lett. 2024, 16, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Luo, Y.; Deng, H.; Shi, S.; Tian, S.; Wu, H.; Tang, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, X.; Zha, J.; et al. Advanced dielectric materials for triboelectric nanogenerators: Principles, methods, and applications. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2314380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Guo, P.; Liu, X.; Chen, M.; Li, J.; Hu, Z.; Li, G.; Chang, Q.; Shi, K.; Wang, X.; et al. Fully polymeric conductive hydrogels with low hysteresis and high toughness as multi-responsive and self-powered wearable sensors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2316346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Larionova, T.; Kobykhno, I.; Klinkov, V.; Shalnova, S.; Tolochko, O. Graphene-Doped Thermoplastic Polyurethane Nanocomposite Film-Based Triboelectric Nanogenerator for Self-Powered Sport Sensor. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Bao, G.; Xie, S.; Chen, X. A paradigm-shift self-powered optical sensing system enabled by the rotation driven instantaneous discharging triboelectric nanogenerator (RDID-TENG). Nano Energy 2023, 115, 108732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Yu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Long, L.; Tan, H.; Li, N.; Xu, L.; Xu, J. Highly sensitive strain sensor and self-powered triboelectric nanogenerator using a fully physical crosslinked double-network conductive hydrogel. Nano Energy 2022, 104, 107955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Ren, J.; Ding, W.; Liu, M.; Pan, G.; Wu, C. Research on Vibration Accumulation Self-Powered Downhole Sensor Based on Triboelectric Nanogenerators. Micromachines 2024, 15, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Wang, Z.; Xu, L.; Wang, A.C.; Han, K.; Jiang, T.; Lai, Q.; Bai, Y.; Tang, W.; Fan, F.R.; et al. Flexible and durable wood-based triboelectric nanogenerators for self-powered sensing in athletic big data analytics. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, K.; Takahashi, S.; Harii, K.; Ieda, J.; Koshibae, W.; Ando, K.; Maekawa, S.; Saitoh, E. Observation of the spin Seebeck effect. Nature 2008, 455, 778–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, R.; Tang, F.; Zhang, N.; Wang, X. Flexible, high-power density, wearable thermoelectric nanogenerator and self-powered temperature sensor. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 38616–38624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Hao, Y.; He, M.; Qin, X.; Wang, L.; Yu, J. Stretchable thermoelectric-based self-powered dual-parameter sensors with decoupled temperature and strain sensing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 60498–60507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xue, W.; Dai, Y.; Li, B.; Chen, Y.; Liao, B.; Zeng, W.; Tao, X.; Zhang, M. High ionic thermopower in flexible composite hydrogel for wearable self-powered sensor. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2022, 230, 109771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; Yin, J.; Xu, Y.; Fei, W.; Xue, M.; Guo, W. Emerging hydrovoltaic technology. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2018, 13, 1109–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, J.; Zhou, J.; Fang, S.; Guo, W. Hydrovoltaic energy on the way. Joule 2020, 4, 1852–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Luo, Y.; Ji, H.; Wang, S.; Huang, B.; Zhu, X.; Wang, L. Insight into Hydrovoltaic Technology: From Mechanism to Applications. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2025, 9, 2400805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, S.; Jin, Y.; Lichtfouse, E.; Zhou, X. Hydrovoltaic technologies for self-powered sensing and pollutant removal in water and wastewater: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2025, 23, 961–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odoi-Yorke, F.; Agyekum, E.; Tarawneh, B.; Rashid, F.; Nyarkoh, R.; Mensah, E.; Kumar, P. Hydrovoltaic energy harvesting: A systematic review and bibliometric analysis of technological innovations, research trends, and future prospects. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2025, 27, 101126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Ye, J.; Gao, J.; Chen, M.; Zhou, S. Harnessing microbes to pioneer environmental biophotoelectrochemistry. Trends Biotechnol. 2024, 42, 1677–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, Z.; Dai, M.; Liu, X.; Wang, H.; Tan, S.C. Leaf-based energy harvesting and storage utilizing hygroscopic iron hydrogel for continuous power generation. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 5267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malvankar, N.S.; Vargas, M.; Nevin, K.P.; Franks, A.E.; Leang, C.; Kim, B.-C.; Inoue, K.; Mester, T.; Covalla, S.F.; Johnson, J.P.; et al. Tunable metallic-like conductivity in microbial nanowire networks. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2011, 6, 573–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevin, K.P.; Kim, B.-C.; Glaven, R.H.; Johnson, J.P.; Woodard, T.L.; Methé, B.A.; DiDonato, R.J.; Covalla, S.F.; Franks, A.E.; Liu, A.; et al. Anode biofilm transcriptomics reveals outer surface components essential for high density current production in Geobacter sulfurreducens fuel cells. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e5628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanni, P.S.; Schrott, G.D.; Robuschi, L.; Busalmen, J.P. Charge accumulation and electron transfer kinetics in Geobacter sulfurreducens biofilms. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 6188–6195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Chen, J.; Huang, H.; Liu, W.; Ye, Y.; Cheng, S. The effect of biofilm thickness on electrochemical activity of Geobacter sulfurreducens. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 16523–16528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, M.; Malvankar, N.S.; Tremblay, P.L.; Leang, C.; Smith, J.A.; Patel, P.; Snoeyenbos-West, O.; Nevin, K.P.; Lovley, D.R. Aromatic amino acids required for pili conductivity and long-range extracellular electron transport in Geobacter sulfurreducens. MBio 2013, 4, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Hong, M.; Wang, Z.; Lin, X.; Wang, W.; Zheng, W.; Zhou, S. Microbial biofilm-based hydrovoltaic pressure sensor with ultrahigh sensitivity for self-powered flexible electronics. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2025, 275, 117220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malvankar, N.S.; Lovley, D.R. Microbial nanowires: A new paradigm for biological electron transfer and bioelectronics. ChemSusChem 2012, 5, 1039–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, N.; Xu, G.; Chang, G.; Wu, Y. From Lab to Life: Self-Powered Sweat Sensors and Their Future in Personal Health Monitoring. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, 2409178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Jiang, S.; Zhao, D.; Diao, Y.; Liu, X.; Chen, J.; Liu, J.; Yang, H. Ionic organohydrogel with long-term environmental stability and multifunctionality based on PAM and sodium alginate. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 485, 149810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Liu, N.; Jia, P.; Ren, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Lu, W.; Yao, Q.; Deng, M.; Gao, Y. MXene-enhanced environmentally stable organohydrogel ionic diode toward harvesting ultralow-frequency mechanical energy and moisture energy. SusMat 2023, 3, 859–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Jia, P.; Ren, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Lu, W.; Yao, Q.; Deng, M.; Zhou, X.; Gao, Y.; Liu, N. Recent advances in self-powered sensors based on ionic hydrogels. Research 2025, 8, 0571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Cong, H.; Jiang, G.; Liang, X.; Liu, L.; He, H. A review on PVDF nanofibers in textiles for flexible piezoelectric sensors. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2023, 6, 1522–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Xian, S.; Zhang, Z.; Hou, X.; He, J.; Mu, J.; Geng, W.; Qiao, X.; Zhang, L.; Chou, X. Synergistic piezoelectricity enhanced BaTiO3/polyacrylonitrile elastomer-based highly sensitive pressure sensor for intelligent sensing and posture recognition applications. Nano Res. 2023, 16, 5490–5502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Shao, H.; Liu, Y.; Tang, C.; Zhao, X.; Ke, K.; Bao, R.; Yang, M.; Yang, W. Boosting piezoelectric response of PVDF-TrFE via MXene for self-powered linear pressure sensor. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2021, 202, 108600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, C.; Shi, S.; Si, Y.; Fei, B.; Huang, H.; Hu, J. Recent progress of wearable piezoelectric pressure sensors based on nanofibers, yarns, and their fabrics via electrospinning. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2023, 8, 2201161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Hou, R.; Jiang, F. Recent progress in piezoelectric thin films as self-powered devices: Material and application. Front. Mater. 2024, 11, 1373040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, R.K.; Dutta, J.; Brahma, S.; Rao, B.; Liu, C.P. Review on ZnO-based piezotronics and piezoelectric nanogenerators: Aspects of piezopotential and screening effect. J. Phys. Mater. 2021, 4, 044011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, J.; Xian, S.; Yu, J.; Li, Z.; Zhao, J.; Zhong, J.; Han, X.; Hou, X.; He, J.; Chou, X. Flexible and wearable BaTiO3/polyacrylonitrile-based piezoelectric sensor for human posture monitoring. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2022, 65, 858–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera, B.; Sarkar, M.D. Piezoelectric effect, piezotronics and piezophototronics: A review. IJIR 2016, 2, 1407–1410. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.; Yuan, P.; Lin, R.; Xue, X.; Chen, M.; Xing, L. A self-powered lactate sensor based on the piezoelectric effect for assessing tumor development. Sensors 2024, 24, 2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Chen, X.; Xin, C.; Zhao, F.; Cheng, S.; Lei, M.; Wang, C.; Zhang, J.; Chen, X.; Tian, H.; et al. High-sensitivity and self-powered flexible pressure sensor based on multi-scale structured piezoelectric composite. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 519, 164787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeralingam, S.; Badhulika, S. Lead-free transparent flexible piezoelectric nanogenerator for self-powered wearable electronic sensors and energy harvesting through rainwater. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2022, 5, 12884–12896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Park, H.; Lee, J.H. Recent structure development of poly (vinylidene fluoride)-based piezoelectric nanogenerator for self-powered sensor. Actuators 2020, 9, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliqué, M.; Simão, C.D.; Murillo, G.; Moya, A. Fully-printed piezoelectric devices for flexible electronics applications. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2021, 6, 2001020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, G.; Wang, B.; Yu, X. Progress and perspectives of self-powered gas sensors. Next Materials 2024, 2, 100092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Zhou, Y.; Hu, J.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, T.; Wang, M. Exploration for a BP-ANN model for gas identification and concentration measurement with an ultrasonically radiated catalytic combustion gas sensor. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2022, 362, 131733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J. Ultrasonic Nano/Microfabrication, Handling, and Driving, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.Y.; Song, C.K.; Lee, G.; Song, W.J.; Park, S. A Comprehensive Review of Battery-Integrated Energy Harvesting Systems. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2024, 9, 2302236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.P.; Liu, K.Y.; Bai, R.N.; Liu, D.Z.; Yu, W.; Meng, C.Z.; Li, G.X.; Guo, S.J. Rechargeable Self-Powered pressure sensor based on Zn-ion battery with high sensitivity and Broad-Range response. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 497, 154812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, P.; Zhang, Q.; Ren, Z.; Yin, J.; Lei, D.; Lu, W.; Yao, Q.; Deng, M.; Gao, Y.; Liu, N. Self-powered flexible battery pressure sensor based on gelatin. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 479, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, T.B.; Guha, A.; Lamoureux, A.; VanRenterghem, G.; Sept, D.; Shtein, M.; Yang, J.; Mayer, M. An electric-eel-inspired soft power source from stacked hydrogels. Nature 2017, 552, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallant, J.R.; Traeger, L.L.; Volkening, J.D.; Moffett, H.; Chen, P.-H.; Novina, C.D.; Phillips, G.N.; Anand, R.; Wells, G.B.; Pinch, M.; et al. Genomic basis for the convergent evolution of electric organs. Science 2014, 344, 1522–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catania, K.C. The astonishing behavior of electric eels. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaels, H.; Rinderle, M.; Freitag, R.; Benesperi, I.; Edvinsson, T.; Socher, R.; Gagliardi, A.; Freitag, M. Dye-sensitized solar cells under ambient light powering machine learning: Towards autonomous smart sensors for the internet of things. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 2895–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zha, J.; Zeng, Z.; Tan, C. Recent advances in wearable self-powered energy systems based on flexible energy storage devices integrated with flexible solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 18887–18905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalla, U.K.; Agarwal, K.L.; Bhati, N. Stand-Alone Solar PV-Fed Reduced Sensor-Based MPPT Controlled Pentamerous Cell Converter for BLDCM-Driven Milling System. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2025, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Yoo, H. Self-powered sensors: New opportunities and challenges from two-dimensional nanomaterials. Molecules 2021, 26, 5056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elizalde, J.; Cruces, C.; Sandoval, M.S.; Eguiluz, X.; Val, I. Self-powered photovoltaic bluetooth® low energy temperature sensor node. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 111305–111314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaels, H.; Rinderle, M.; Benesperi, I.; Freitag, R.; Gagliardi, A.; Freitag, M. Emerging indoor photovoltaics for self-powered and self-aware IoT towards sustainable energy management. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 5350–5360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Han, Z.; Ren, J.; Hou, H.; Pan, D. An overview of flexible sensing nanocomposites. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2024, 7, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Jiang, Z.; Tian, Z.; Wang, H.; Wang, H.; Zi, Y. Self-powered, ultrasensitive, and high-resolution visualized flexible pressure sensor based on color-tunable triboelectrification-induced electroluminescence. Nano Energy 2021, 79, 105431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhu, W.; Deng, Y.; Zhu, P.; Yu, Y.; Hu, S.; Zhang, R. High-sensitivity self-powered temperature/pressure sensor based on flexible Bi-Te thermoelectric film and porous microconed elastomer. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2022, 103, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Mukasa, D.; Zhang, H.; Gao, W. Self-powered wearable biosensors. Acc. Mater. Res. 2021, 2, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monshausen, G.B.; Swanson, S.J.; Gilroy, S. Touch sensing and thigmotropism. Plant Trop. 2008, 5, 91–122. [Google Scholar]

- Braam, J. In touch: Plant responses to mechanical stimuli. New Phytol. 2005, 165, 373–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravi, S.K.; Wu, T.; Udayagiri, V.S.; Vu, X.M.; Wang, Y.; Jones, M.R.; Tan, S.C. Photosynthetic bioelectronic sensors for touch perception, UV-detection, and nanopower generation: Toward self-powered E-skins. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1802290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, M.C.; Brand, A.C. Thigmo responses: The fungal sense of touch. Microbiol. Spectr. 2017, 5, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massa, G.D.; Gilroy, S. Touch modulates gravity sensing to regulate the growth of primary roots of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2003, 33, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Z.; Xu, J.; Bowen, C.R.; Zhou, S. Self-powered and self-sensing devices based on human motion. Joule 2022, 6, 1501–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, Z.; Wan, X.; Xu, J.; Duan, C.; Zheng, T.; Chen, J. Speaking without vocal folds using a machine-learning-assisted wearable sensing-actuation system. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Tat, T.; Yin, J.; Ngo, D.; Zhao, X.; Wan, X.; Chen, J. A textile magnetoelastic patch for self-powered personalized muscle physiotherapy. Matter 2023, 6, 2235–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zhou, Y.; Kwak, W.; Li, A.; Wang, S.; Dallenger, M.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Y.; Lium, A.; Chen, J. A reconfigurable and conformal liquid sensor for ambulatory cardiac monitoring. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, D.-J.; Song, W.-Z.; Li, C.-L.; Chen, T.; Zhang, D.-S.; Zhang, J.; Ramakrishna, S.; Long, Y.-Z. High-voltage direct current triboelectric nanogenerator based on charge pump and air ionization for electrospinning. Nano Energy 2022, 101, 107599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, D.; Fu, X.; Mo, L.; Miao, Q.; Huang, R.; Huang, X.; Guo, W.; Li, Y.; Zheng, Q.; et al. Tactile sensing for soft robotic manipulators in 50 MPa hydrostatic pressure environments. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2023, 5, 2300296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Tian, H.; Wang, Z.; Nie, C.; Zhou, P.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, F.; Wu, Y.; Zheng, H. A novel method reflecting mechanical-electrical conversion process of triboelectric nanogenerators and its application in human-machine interaction. Nano Energy 2025, 133, 110427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waseem, A.; Abdullah, A.; Bagal, I.V.; Ha, J.S.; Lee, J.K.; Ryu, S.W. Self-powered and flexible piezo-sensors based on conductivity-controlled GaN nanowire-arrays for mimicking rapid-and slow-adapting mechanoreceptors. npj Flex. Electron. 2022, 6, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepancikova, R.; Olejnik, R.; Matyas, J.; Masar, M.; Hausnerova, B.; Slobodian, P. Pressure-driven piezoelectric sensors and energy harvesting in biaxially oriented polyethylene terephthalate film. Sensors 2024, 24, 1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.Z.; Gao, F.L.; Liu, J.; Li, Y.; Wan, P.; Yu, Z.Z.; Li, X. Self-powered resilient porous sensors with thermoelectric poly (3, 4-ethylenedioxythiophene): Poly (styrenesulfonate) and carbon nanotubes for sensitive temperature and pressure dual-mode sensing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 43783–43791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, H.; Guo, H.; Huang, L.; Lu, T. Self-Powered Iontronic Capacitive Sensing Unit with High Sensitivity in Charge-Output Mode. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2412377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Jiang, Y.; Ren, T.; Chen, B.; Zhang, R.; Mao, Y. Recent advances in nature inspired triboelectric nanogenerators for self-powered systems. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 2024, 6, 062003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Peng, H.; Rwei, A.Y. Flexible, wearable biosensors for digital health. Med. Nov. Technol. Devices 2022, 14, 100118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Wang, C.; Wang, B.; Wang, B.; Liu, F. Highly sensitive and stable multifunctional self-powered triboelectric sensor utilizing Mo2CTx/PDMS composite film for pressure sensing and non-contact sensing. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duah, J.A.; Lee, K.S.; Kim, B.G. A self-powered wireless temperature sensor platform for foot ulceration monitoring. Sensors 2024, 24, 6567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Pan, Q.; Huang, Z.; Gu, C.; Wang, T.; Xu, J.; Yan, Z.; Zhao, F.; Li, P.; Tu, Y.; et al. Ultrafast response of self-powered humidity sensor of flexible graphene oxide film. Mater. Des. 2023, 226, 111683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, B.; Lu, M.; Wu, T.; Peng, W.; Ko, T.; Hsiao, Y.; Chen, J.; Sun, B.; Liu, R.; Lai, Y. Large-area, untethered, metamorphic, and omnidirectionally stretchable multiplexing self-powered triboelectric skins. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Tang, Q.; Wang, Z.L.; Li, Z. Self-powered cardiovascular electronic devices and systems. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2021, 18, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, G.; Xu, L.; Cheng, X.; Li, Y.; Huang, X.; Guo, W.; Liu, S.; Wang, Z.L.; Wu, H. Bioinspired triboelectric nanogenerators as self-powered electronic skin for robotic tactile sensing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1907312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Xu, X.; Chen, S.; Fang, Y.; Shi, X.; Deng, Y.; Cao, C. Skin-inspired textile-based tactile sensors enable multifunctional sensing of wearables and soft robots. Nano Energy 2022, 96, 107137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Lu, J.; Zheng, M.; Wang, D.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, M. Self-powered bionic antenna based on triboelectric nanogenerator for micro-robotic tactile sensing. Nano Energy 2023, 114, 108644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; He, M.; Djoulde, A.; Wang, Z.; Liu, M. A novel self-powered sensitive porous ZnO NWs/PDMS sponge capacitive pressure sensor. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 2740, 012061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gao, Z.; Wu, W.; Xiong, Y.; Luo, J.; Sun, Q.; Mao, Y.; Wang, Z.L. TENG-Boosted Smart Sports with Energy Autonomy and Digital Intelligence. Nano-Micro Lett. 2025, 17, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, H.; Burgueño, R.; Chakrabartty, S.; Lajnef, N.; Alavi, A.H. A comprehensive review of self-powered sensors in civil infrastructure: State-of-the-art and future research trends. Eng. Struct. 2021, 234, 111963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, D.; Tang, M.; Zhang, H.; Sun, T.; Yang, C.; Mao, R.; Li, K.; Wang, J. Ethylene chlorotrifluoroethylene/hydrogel-based liquid-solid triboelectric nanogenerator driven self-powered MXene-based sensor system for marine environmental monitoring. Nano Energy 2022, 100, 107509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Zhao, X.; Hao, C.; Ma, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhang, A.; Zhang, W.; Li, L.; Zhang, W. Multifunctional PVDF/CeO2@ PDA nanofiber textiles with piezoelectric and piezo-phototronic properties for self-powered piezoelectric sensor and photodetector. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 482, 148950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, G.; Zhao, J.; Shao, Y.; Liu, T.; Luo, B.; Zhang, S.; Chi, M.; Cai, C.; Liu, Z.; Wang, S.; et al. A self-damping triboelectric tactile patch for self-powered wearable electronics. eScience 2025, 5, 100324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, M.; Li, S.; Liang, H.; Bi, P.; Wang, S.; Wang, H.; Gan, L.; Wu, X.; et al. Intelligent perceptual textiles based on ionic-conductive and strong silk fibers. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, A.; Patel, A.B.; Baraniuk, R.G. A deep learning approach to structured signal recovery. In Proceedings of the 2015 53rd Annual Allerton Conference on Communication, Control, and Computing (Allerton), Monticello, IL, USA, 29 September–2 October 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 1336–1343. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, L.; Tang, Z.; Feng, J.; Jiang, Y.; Tang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Xing, X.; Gao, J. A flexible self-powered multimodal sensor with low-coupling temperature, pressure and humidity detecting for physiological monitoring and human-robot collaboration. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 519, 164866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; Lou, Z.; Chen, S.; Shen, G. Flexible and transparent capacitive pressure sensor with patterned microstructured composite rubber dielectric for wearable touch keyboard application. Sci. China Mater. 2018, 61, 1587–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Du, C.; Liang, L.; Chen, G. Cement-Based Thermoelectric Materials, Devices and Applications. Nano-Micro Letters 2026, 18, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parhi, R.; Nowak, R.D. Deep learning meets sparse regularization: A signal processing perspective. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2023, 40, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Sun, M.; Xu, W.; Zhao, X.; Du, T.; Sun, P.; Xu, M. Advances in marine self-powered vibration sensor based on triboelectric nanogenerator. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Q.F.; Sagahyroon, A. RISC-V: A Comprehensive Overview of an Emerging ISA for the AI-IoT Era. In Advances in the Internet of Things; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2025; pp. 244–284. [Google Scholar]

| Sensor Type | Performance Value | Test Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Thermoelectric sensing (Bi2Te3 thin film) | 1. Room temperature conductivity: Bi2Te3 is 5.1 × 104 S m−1. 2. Power factor: Sb2Te3 is twice that of Bi2Te3. | 1. Thermoelectric performance test: Measured by ZEM-3 instrument. 2. Temperature range: within 100 °C 3. Film preparation: sputtering at 350 °C and 2 Pa for 4 h. |

| Thermoelectric sensing (TEG integration) | 1. 0.1 K temperature difference output voltage 0.36 mV. 2. Periodic output of 8.1 mV at 33 °C hot side/31 °C cold side. 3. The temperature measurement deviation of the hot cup is ≤ 1.1%. | 1. Temperature test: industrial refrigeration chiller temperature control, temperature difference 0.1 to 100 K. 2. Pressure coupling test: apply a load of 16 to 5800 Pa to the stepping motor at a frequency of 0.2 to 2 Hz. |

| Sensor Type | Coefficient | Temperature Resolution | Thermal Range | Cyclic Stability | Uncertainty (±) | Source of Literature |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermoelectric sensing (Bi2Te3 thin film) | Bi2Te3: −180 μV/K; Sb2Te3: 240 μV/K | <0.1 K | 0~100 °C | It declined by 3.2% in three months | Seebeck coefficient ±5 μV/K; temperature resolution ± 0.01 K | [110] |

| Thermoelectric sensing (TEG integration) | 3.77 mV/K | <0.1 K | 23.8~35.8 °C | _ | Sensitivity: ±0.05 mV/K; temperature resolution ±0.05 K | [110] |

| Piezoelectric sensing (GaN nanowires) | _ | _ | 25 ± 5 °C | Mechanical cycle > 5000 times | _ | [113] |

| Piezoelectric sensing (BOPET film) | _ | _ | Room temperature to 245 °C | 80 pressure cycle outputs | Output voltage ± 2 V | [114] |

| Sensor Type | Core Materials/Structure | Quantitative Parameters Related to Energy Conversion |

|---|---|---|

| Triboelectric nano- generator (TENG) [33] | WPF-MTENG | Rainfall: maximum power density 0.35–19.53 μW/m2; Wind energy: maximum power density 30 to 70 μW/m2. |

| Hydrovoltaic effect-based sensor [63] | mBio-HPS | Peak power density ≈ 1500 μW/m2 (150 nW/cm2). |

| Battery-integrated sensor [86] | RZIB-FPS | Energy density: 392 µWh/cm2; Power density: 5.4 W/m2 (0.54 mW/cm2). |

| Gel-based TENG (aerogel type) [39] | CCA-TENG | The power density is 1237 mW/m2; After 64,800 cycles, the performance remains at 91.04%. |

| Gel-based TENG (organic hydrogel type) [39] | MX-GO/CNF/ SA/PVA | Energy density: 392 µWh/cm2; Power density: 5.4 W/m2 (0.54 mW/cm2). |

| Gel-based TENG (ionic gel type) [39] | IG 70–10% | The maximum power density is 157.1 mW/m2; The ionic conductivity is 2.18 mS/cm. |

| Mechanism Mode | Materials | Sensing Type | Range | Sensitivity | Response Time | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gel-based TENGs | Hydrogel | TENG | 1.3 Pa~6.83 MPa | 0.59 μA/kPa | 10 ms~112.5 μs | [41] |

| mBio-HPS | G.S | Hydrovoltaic effect-based sensor | 16 Pa~25 kPa | 2241.49 kPa−1 | 112.5 μs | [63] |

| RZIB-FPS | PVA-GO | Battery-integrated sensor | 126–330 kPa | 1.18 mVkPa−1 | 96.0 ms | [86] |

| Temperature/pressure sensor | Bi2Te3 | Thermoelectric-based sensor | ≤100 °C | 3.77 mV·K−1 | 24 ms | [99] |

| Sensor based on piezoelectric | PVDF-TrFE | Piezoelectric pressure sensor | 18~79 N | 1.29 mV/(μm·N) | 16~56 ms | [71] |

| Search Type | Search Method |

|---|---|

| Database | Web of science |

| Theme | Self-powered sensor |

| Number of studies | 1000 |

| Boolean retrieval expression | And |

| Time range (Figure 11) | January 2021–December 2025 |

| Time range (Figure 12) | January 2015–December 2025 |

| Node (Figure 11) | Keywords |

| Node (Figure 12) | Cited References |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, X.; Huang, J.; Jia, X.; Zhu, Y.; Xi, S. Self-Powered Flexible Sensors: Recent Advances, Technological Breakthroughs, and Application Prospects. Sensors 2026, 26, 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010143

Wang X, Huang J, Jia X, Zhu Y, Xi S. Self-Powered Flexible Sensors: Recent Advances, Technological Breakthroughs, and Application Prospects. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):143. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010143

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xu, Jiahao Huang, Xuelei Jia, Yinlong Zhu, and Shuang Xi. 2026. "Self-Powered Flexible Sensors: Recent Advances, Technological Breakthroughs, and Application Prospects" Sensors 26, no. 1: 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010143

APA StyleWang, X., Huang, J., Jia, X., Zhu, Y., & Xi, S. (2026). Self-Powered Flexible Sensors: Recent Advances, Technological Breakthroughs, and Application Prospects. Sensors, 26(1), 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010143