From Light to Energy: Machine Learning Algorithms for Position and Energy Deposition Estimation in Scintillator–SiPM Detectors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

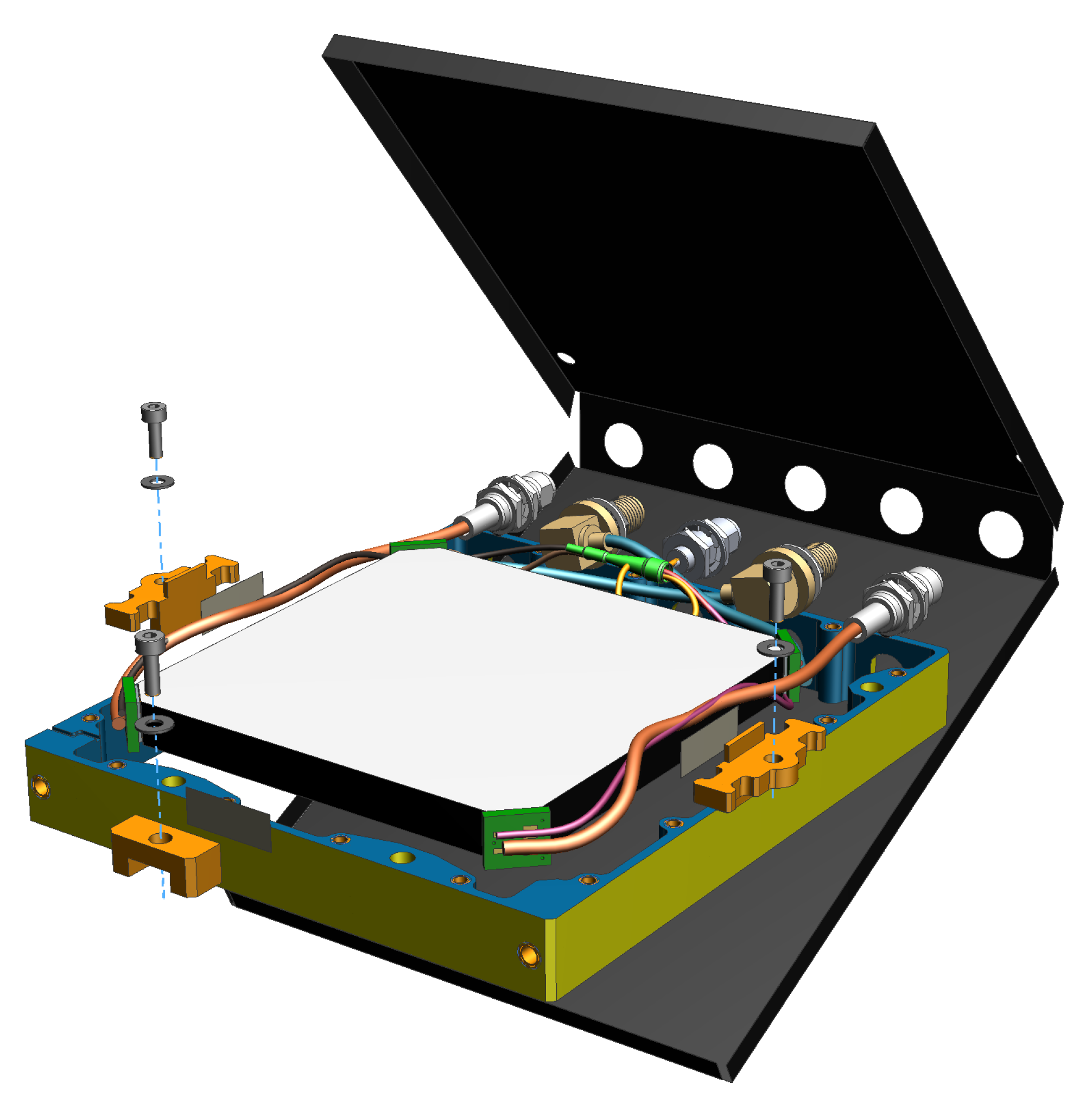

2.1. Scintillator–SiPM Particle Detector (SSPD)

2.1.1. Geometry and Materials

2.1.2. Operating Principle

2.1.3. Simulation

- Muon dataset: simulated 4 GeV muons with randomized incidence positions and angles.

- Oxygen dataset: simulated 18 GeV oxygen ions with randomized incidence positions and angles.

2.2. The Physics-Based Analytic Model

3. Machine Learning Methods

3.1. Gradient Boosted Regression (XGBoost and LightGBM)

- XGBoost is a highly effective tree boosting algorithm [18]. It works by constructing additive ensembles of decision trees using second-order gradient information. It is robust to nonlinear feature interactions and performs well on structured datasets. Since its introduction, XGBoost, due to its scalability and speed, quickly became one of the most popular ML algorithms. In our context, it effectively models the nonlinear relationship between the signals detected by the SiPMs, the particle impinging positions and as a result, LET estimation.

- Designed by Microsoft, LightGBM [19] introduces histogram-based training and leaf-wise tree growth to improve training and prediction efficiency. LightGBM is designed for faster training speeds and higher efficiency, particularly on large datasets, compared to some other gradient boosting frameworks like XGBoost. This is achieved through innovative techniques such as Gradient-based One-Side Sampling (GOSS) and Exclusive Feature Bundling (EFB), which optimize the process of finding optimal split points in decision trees.

3.2. Hybrid Intelligence: A Fusion of Machine Learning and Analytics

3.2.1. Boosting

3.2.2. Probing

4. Training and Hyperparameters

4.1. Inputs and Targets

4.2. XGBoost and LightGBM

4.2.1. Search Space

- maximum tree depth: ;

- number of leaves (LightGBM): ;

- learning rate: ;

- number of boosting rounds: ;

- subsampling ratio: ;

- feature sampling ratio: ;

- minimum child samples (LightGBM): .

4.2.2. Objective Function

4.2.3. Best-Performing Configurations

4.2.4. Hyperparameter Importance

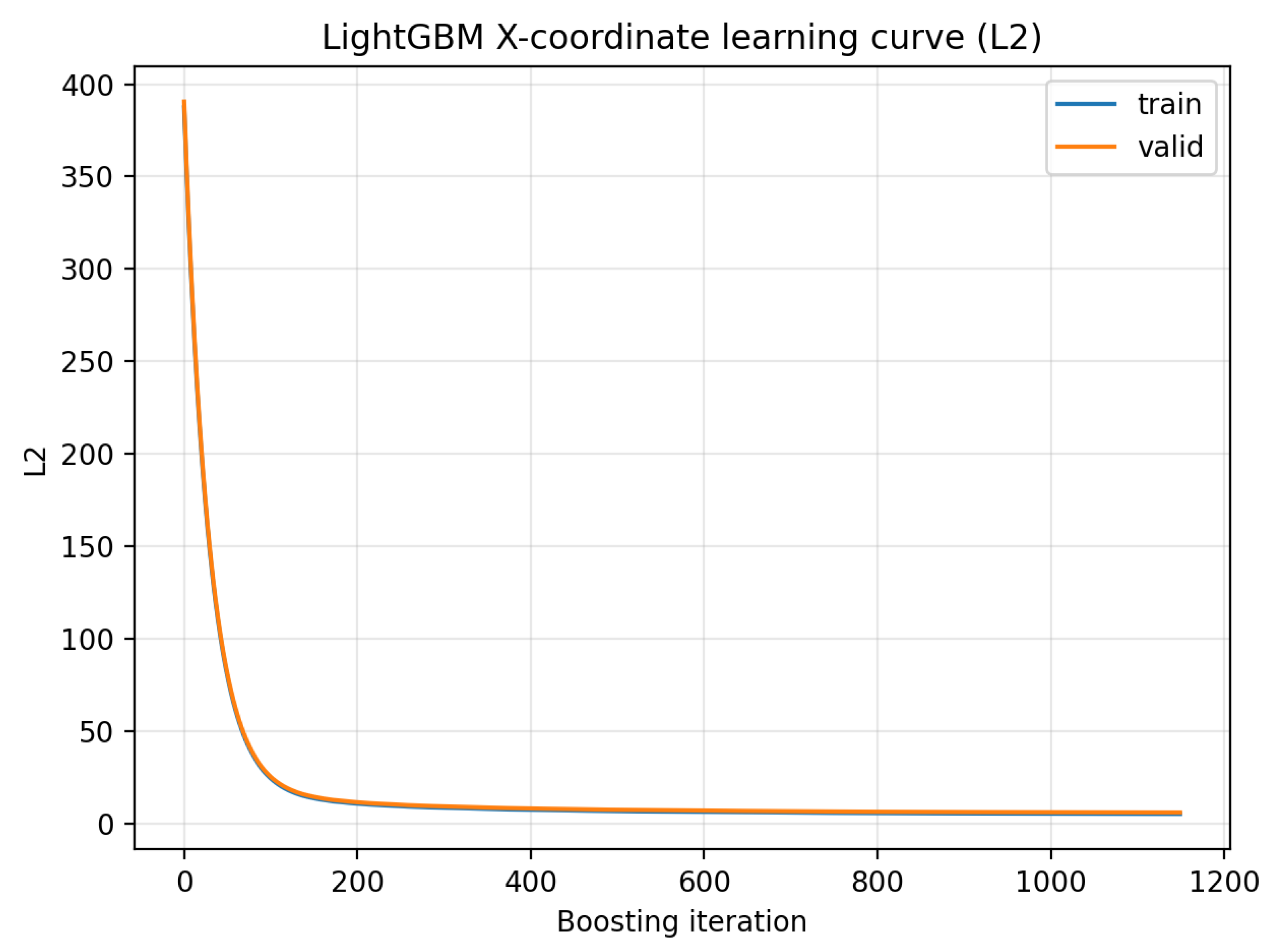

4.3. Convergence Diagnostics

4.4. Hybrid Boosting

4.5. Probing Hybrid

5. Results

5.1. Localization and LET Estimation Accuracy

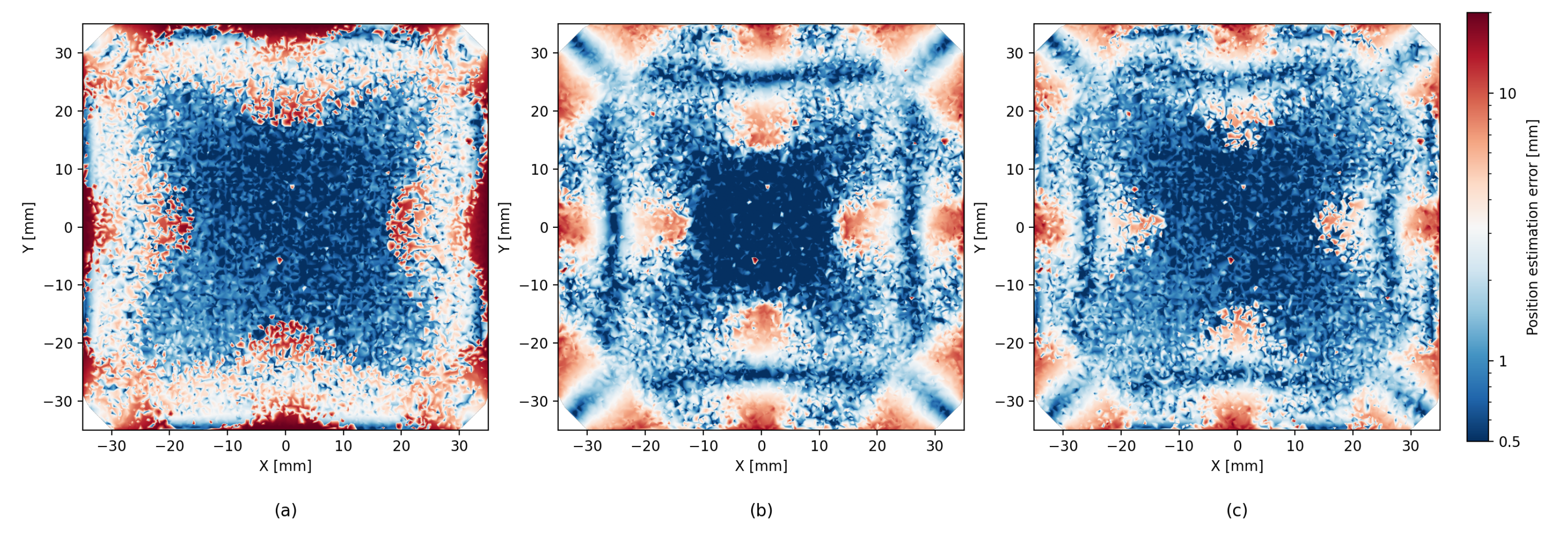

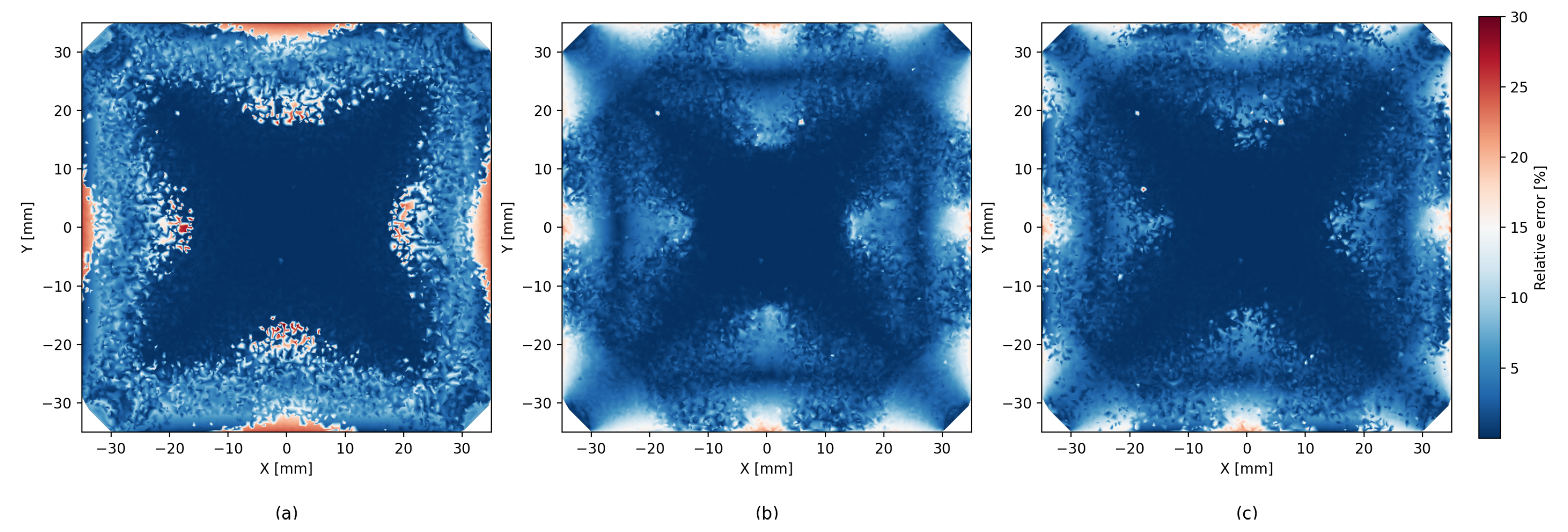

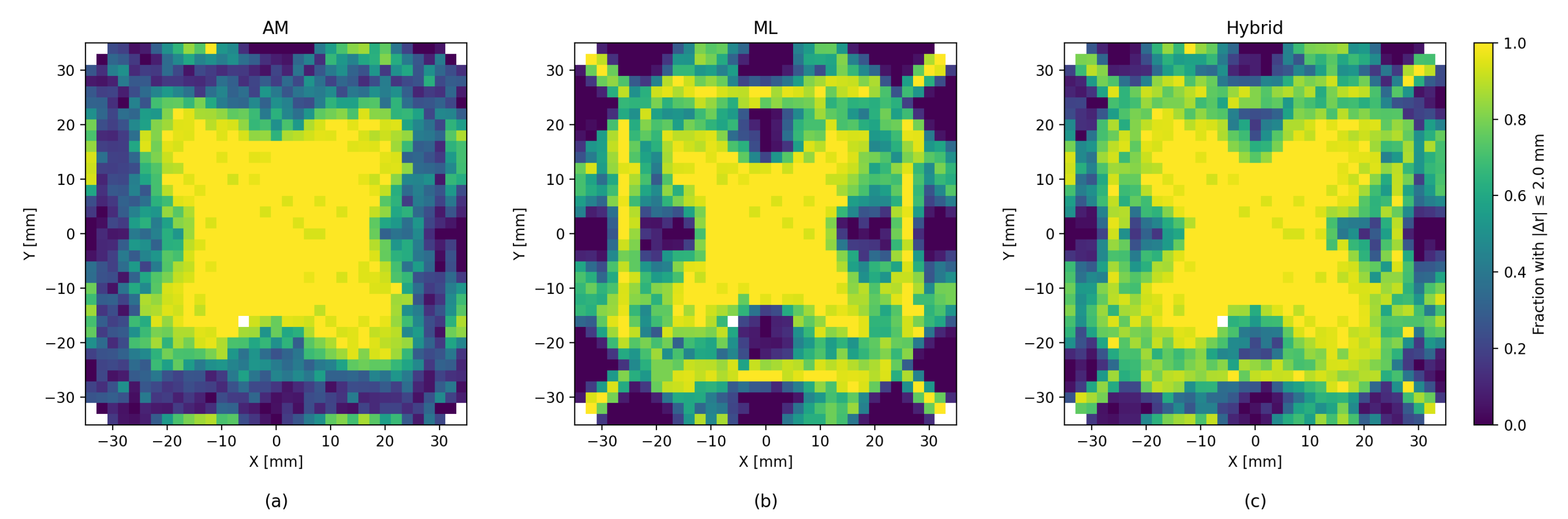

5.2. Error Heatmaps

5.3. Error Distribution

5.4. Statistical Analysis

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Simhony, Y.; Segal, A.; Orlov, Y.; Amrani, O.; Etzion, E. Scintillator-SiPM detector for tracking and energy deposition measurements. Nucl. Instruments Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 2024, 1069, 169955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simhony, Y.; Amrani, O.; Etzion, E. TauSat-3-A 3U CubeSat for investigating variations in solar and galactic cosmic rays. In Proceedings of the 43rd COSPAR Scientific Assembly, Virtual, 28 January–4 February 2021; Volume 43, p. 1520. Available online: https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2021cosp...43E1520S/abstract (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Simhony, Y.; Segal, A.; Orlov, Y.; Bashi, D.; Amrani, O.; Etzion, E. Spaceborne COTS-Capsule hodoscope: Detecting and characterizing particle radiation. Nucl. Instruments Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 2025, 1070, 169996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heredge, J.; Archer, J.; Duffy, A.; Brown, J.; Guatelli, S.; Scutti, F.; Krishnan, S.; Webster, C. Muon event localisation with AI. Nucl. Instruments Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 2021, 1001, 165237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaari, M.; Barron, U.; Domínguez, L.P.; Chen, B.; Barak, L.; Etzion, E.; Giryes, R. Trees vs neural networks for enhancing tau lepton real-time selection in proton-proton collisions. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomadakis, P.; Angelopoulos, A.; Gavalian, G.; Chrisochoides, N. Using machine learning for particle track identification in the CLAS12 detector. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2022, 276, 108360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siviero, F.; Arcidiacono, R.; Cartiglia, N.; Costa, M.; Ferrero, M.; Legger, F.; Mandurrino, M.; Sola, V.; Staiano, A.; Tornago, M. First application of machine learning algorithms to the position reconstruction in Resistive Silicon Detectors. J. Instrum. 2021, 16, P03019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, G.; Yahiaoui, M.B.; Comtat, C.; Jan, S.; Kochebina, O.; Martinez, J.M.; Sergeyeva, V.; Sharyy, V.; Sung, C.H.; Yvon, D. Deep Learning reconstruction with uncertainty estimation for γ photon interaction in fast scintillator detectors. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 131, 107876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, P.; Ajaj, R.; Alpízar-Venegas, M.; Amaudruz, P.A.; Anstey, J.; Araujo, G.; Auty, D.; Baldwin, M.; Batygov, M.; Beltran, B.; et al. Position reconstruction in the DEAP-3600 dark matter search experiment. J. Instrum. 2025, 20, P07012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ticchi, G.; Buonanno, L.; Di Vita, D.; Canclini, F.; Carminati, M.; Camera, F.; Fiorini, C. Embedded artificial intelligence for position sensitivity in thick scintillators. Nucl. Instruments Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 2022, 1041, 167309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonanno, L. Gamma-Ray Spectroscopy and Imaging with SiPMs Readout of Scintillators: Front-End Electronics and Position Sensitivity Algorithms. In Special Topics in Information Technology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, F.; Schug, D.; Hallen, P.; Grahe, J.; Schulz, V. A novel DOI positioning algorithm for monolithic scintillator crystals in PET based on gradient tree boosting. IEEE Trans. Radiat. Plasma Med. Sci. 2018, 3, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, F.; Schug, D.; Hallen, P.; Grahe, J.; Schulz, V. Gradient tree boosting-based positioning method for monolithic scintillator crystals in positron emission tomography. IEEE Trans. Radiat. Plasma Med. Sci. 2018, 2, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González González, B.; Abascal Ruiz, U.; Villa Alfageme, M.; Hurtado Bermúdez, S.J. Accuracy of Machine Learning Algorithms for Hpge Detector Efficiency Determination. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2026, 239, 113328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesilkanat, C.M.; Celik, N.; Celik, A.; Cevik, U. Interpretable machine learning for rapid prediction and calibration of HPGe detector efficiency: A physics-informed approach and online platform. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2025, 334, 7231–7253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didona, D.; Quaglia, F.; Romano, P.; Torre, E. Enhancing performance prediction robustness by combining analytical modeling and machine learning. In Proceedings of the 6th ACM/SPEC International Conference on Performance Engineering, Austin, TX, USA, 31 January–4 February 2015; pp. 145–156. [Google Scholar]

- Agostinelli, S.; Allison, J.; Amako, K.; Apostolakis, J.; Araujo, H.; Arce, P.; Asai, M.; Axen, D.; Banerjee, S.; Barrand, G.; et al. GEANT4—A simulation toolkit. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 2003, 506, 250–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, G.; Meng, Q.; Finley, T.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Ma, W.; Ye, Q.; Liu, T.Y. Lightgbm: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 52. [Google Scholar]

- Akiba, T.; Sano, S.; Yanase, T.; Ohta, T.; Koyama, M. Optuna: A next-generation hyperparameter optimization framework. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, Anchorage, AK, USA, 4–8 August 2019; pp. 2623–2631. [Google Scholar]

- Gargiulo, R.; Ciccarella, V.; Di Meco, E.; Diociaiuti, E.; Sarra, I. Development of a sub-mm particle tracking detector based on a plastic scintillator with SiPM charge sharing. J. Instrum. 2024, 19, T12006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | Position RMSE [mm] | Mean LET Error | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Area | 50 × 50 | Full Area | 50 × 50 | |

| Analytic (AM) | 6.1 | 5 | ||

| LightGBM | 4.3 | 2 | ||

| XGBoost | 4.2 | 2.05 | ||

| Probing LightGBM | 4.0 | 2 | ||

| Probing XGBoost | 4.0 | 2 | ||

| Method | Position RMSE [mm] | Mean LET Error | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Area | 50 × 50 | Full Area | 50 × 50 | |

| Analytic (AM) | 3.3 | 1.6 | ||

| LightGBM | 2.3 | 0.52 | ||

| XGBoost | 2.3 | 0.53 | ||

| Probing LightGBM | 1.9 | 0.51 | ||

| Probing XGBoost | 2 | 0.51 | ||

| Full Detector Area | ||

|---|---|---|

| Model | Mean Error [mm] | 95% CI [mm] |

| Analytic Model | 3.300 | [3.25, 3.35] |

| ML only | 2.275 | [2.246, 2.303] |

| Hybrid | 1.913 | [1.887, 1.940] |

| Comparison | [mm] | 95% CI [mm] |

| Analytic − ML | 1.025 | [0.98, 1.072] |

| Analytic − Hybrid | 1.387 | [1.345, 1.429] |

| ML − Hybrid | 0.362 | [0.329, 0.378] |

| Central Region | ||

| Model | Mean Error [mm] | 95% CI [mm] |

| Analytic Model | 1.627 | [1.580, 1.673] |

| ML only | 0.501 | [0.493, 0.509] |

| Hybrid | 0.499 | [0.492, 0.507] |

| Comparison | [mm] | 95% CI [mm] |

| Analytic − ML | 1.126 | [1.080, 1.171] |

| ML − Hybrid | 0.002 | not significant |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Simhony, Y.; Segal, A.; Amrani, O.; Etzion, E. From Light to Energy: Machine Learning Algorithms for Position and Energy Deposition Estimation in Scintillator–SiPM Detectors. Sensors 2026, 26, 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010101

Simhony Y, Segal A, Amrani O, Etzion E. From Light to Energy: Machine Learning Algorithms for Position and Energy Deposition Estimation in Scintillator–SiPM Detectors. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):101. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010101

Chicago/Turabian StyleSimhony, Yoav, Alex Segal, Ofer Amrani, and Erez Etzion. 2026. "From Light to Energy: Machine Learning Algorithms for Position and Energy Deposition Estimation in Scintillator–SiPM Detectors" Sensors 26, no. 1: 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010101

APA StyleSimhony, Y., Segal, A., Amrani, O., & Etzion, E. (2026). From Light to Energy: Machine Learning Algorithms for Position and Energy Deposition Estimation in Scintillator–SiPM Detectors. Sensors, 26(1), 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010101