3.4.1. 1D-Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)

The design of CNN involves convolutional computation and a deep structure, inspired by the biological receptive field mechanism [

38,

39].

- 1.

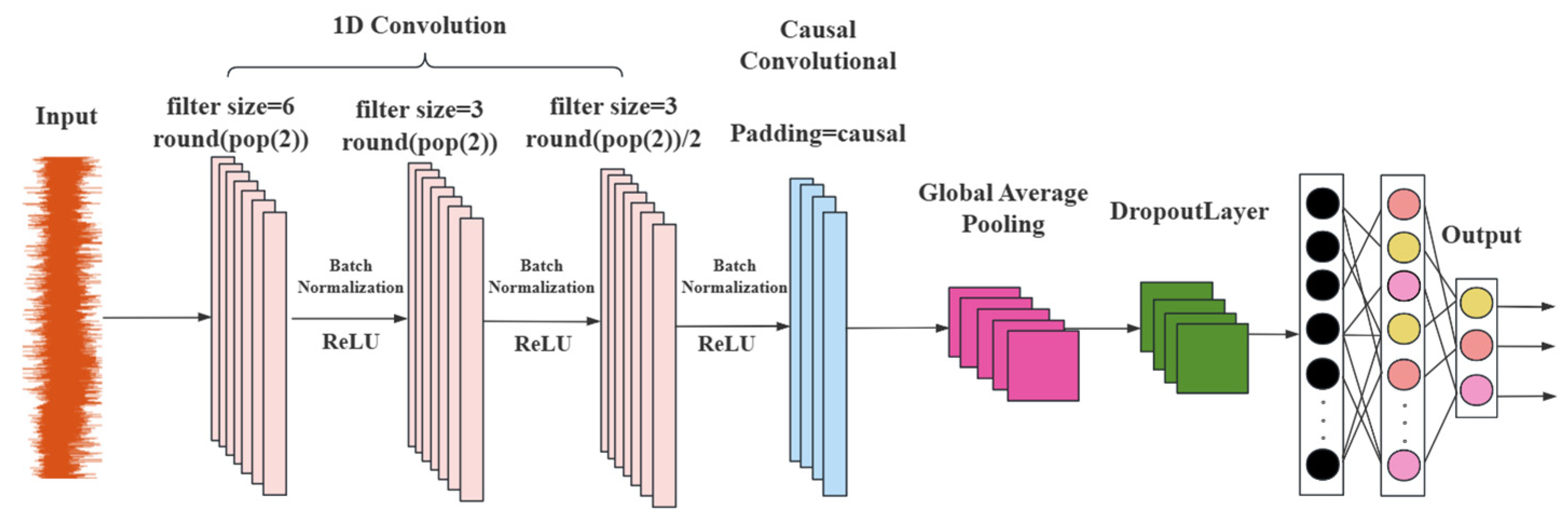

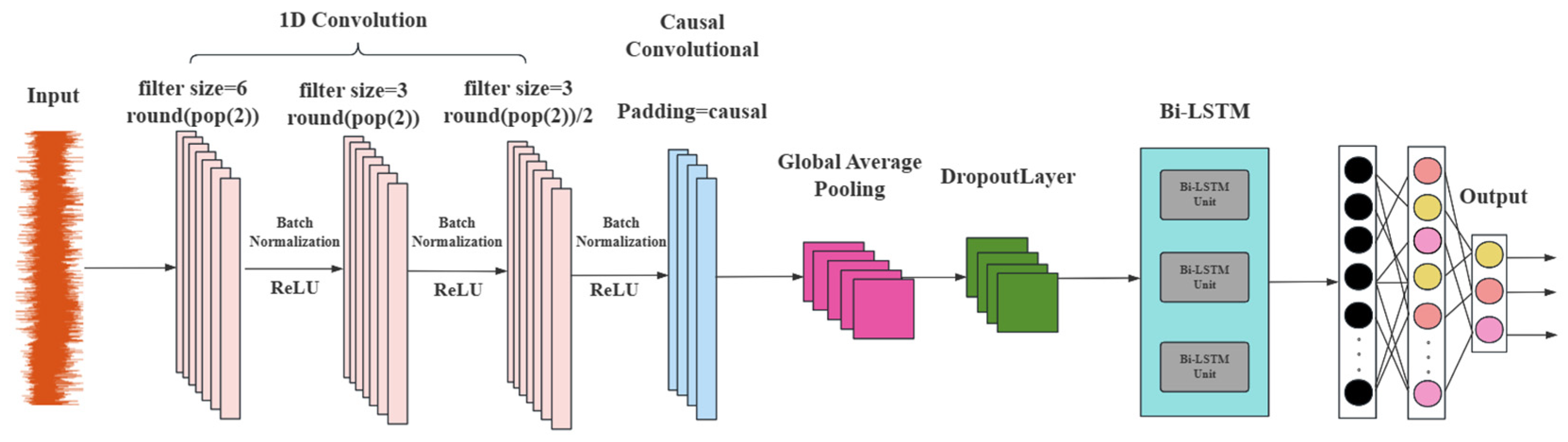

Multi-Layer One-Dimensional Convolution

The leakage data of pipeline acoustic signals mainly consists of time series data [

33]. Time series typically possess characteristics such as temporal dependence, orderliness, coexistence of local and global features, noise sensitivity, high volume, and dynamic variation. Compared to traditional two-dimensional convolution, it is more suitable for processing one-dimensional sequence data and can fully utilize the temporal information of the sequence data. Therefore, we adopt a one-dimensional convolution layer and slide the convolution kernel along the time axis to extract the local features of the leakage signal.

We designed two one-dimensional convolutional layers. The first layer uses a convolution kernel with a size of filtersize = 6 and a total of round (pop (2)) convolution kernels. pop (2) mainly refers to the second element in the arrays popmin and popmax of the parameters of PSO, and the number of convolution kernels is determined through the optimization of PSO. The number of convolution kernels in the second layer is halved (filtersize/2), but the kernel size remains the same. This structure can gradually extract the features of the sequence data. The first layer captures low-level local features, and the second layer extracts higher-level features, enabling the network to learn more complex feature representations and improving the model’s ability to distinguish different types of leakage signals. The number of convolution kernels in the third layer is half of that of the second layer (round(pop (2)/4)), and the kernel size is the same as that of the second layer, extracting higher-level features. Additionally, a batch normalization layer and a rectified linear unit (ReLU) activation layer follow each convolutional layer. Batch normalization speeds up the training process and improves the model’s stability, while the ReLU activation function introduces nonlinearity, allowing the network to learn complex feature patterns and effectively enhancing the network performance.

- 2.

Causal Convolution

During the entire convolution process, using causal convolution (Padding = ‘causal’) ensures that the output of each time step only depends on the current and previous time steps, and is not influenced by information from future time steps. This is particularly important for tasks such as water pipeline leakage detection, as in practical application scenarios where future time step information is unavailable, causal convolution can guarantee that the model’s predictions conform to the causal relationship of the actual situation, that is, the collected pipeline leakage signal and the causal relationship between whether there is leakage and various leakage conditions, thereby improving the reliability and effectiveness of the model in water pipeline leakage detection.

- 3.

Global Average Pooling

At the end of the 1D-CNN section, a global average pooling layer (Global Average Pooling 1D Layer) was used to perform global average pooling on the data of each feature channel, compressing each feature channel into a scalar value. This not only reduces the dimensionality of the features, lowers the complexity of the model, but also retains the important information in the feature channels, while avoiding the overfitting problem that may occur when using fully connected layers. This makes the model more concise and efficient, and also provides a more compact feature representation for the subsequent Bi-LSTM layer.

Figure 9 shows the structure diagram of the 1D-CNN model.

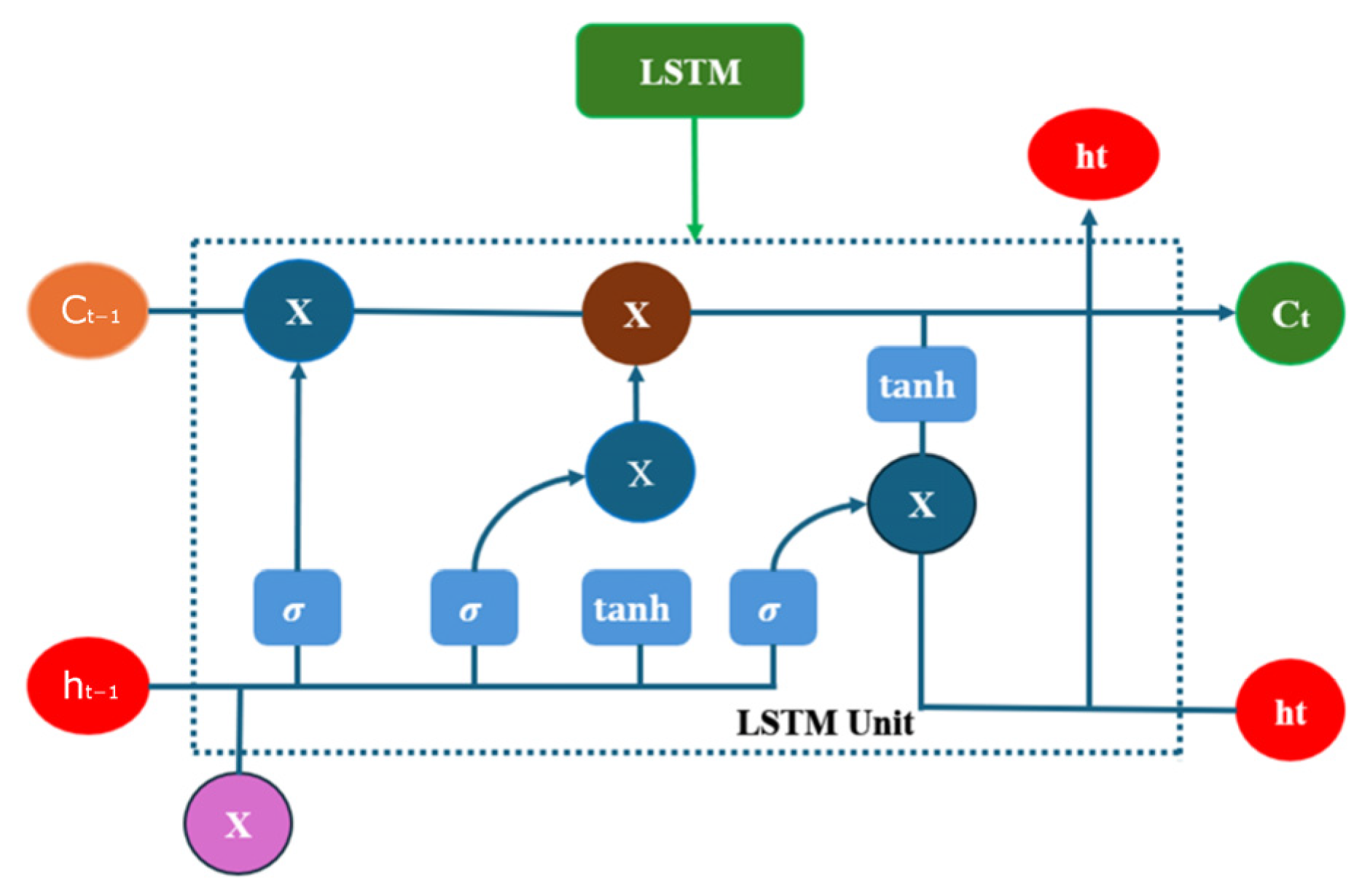

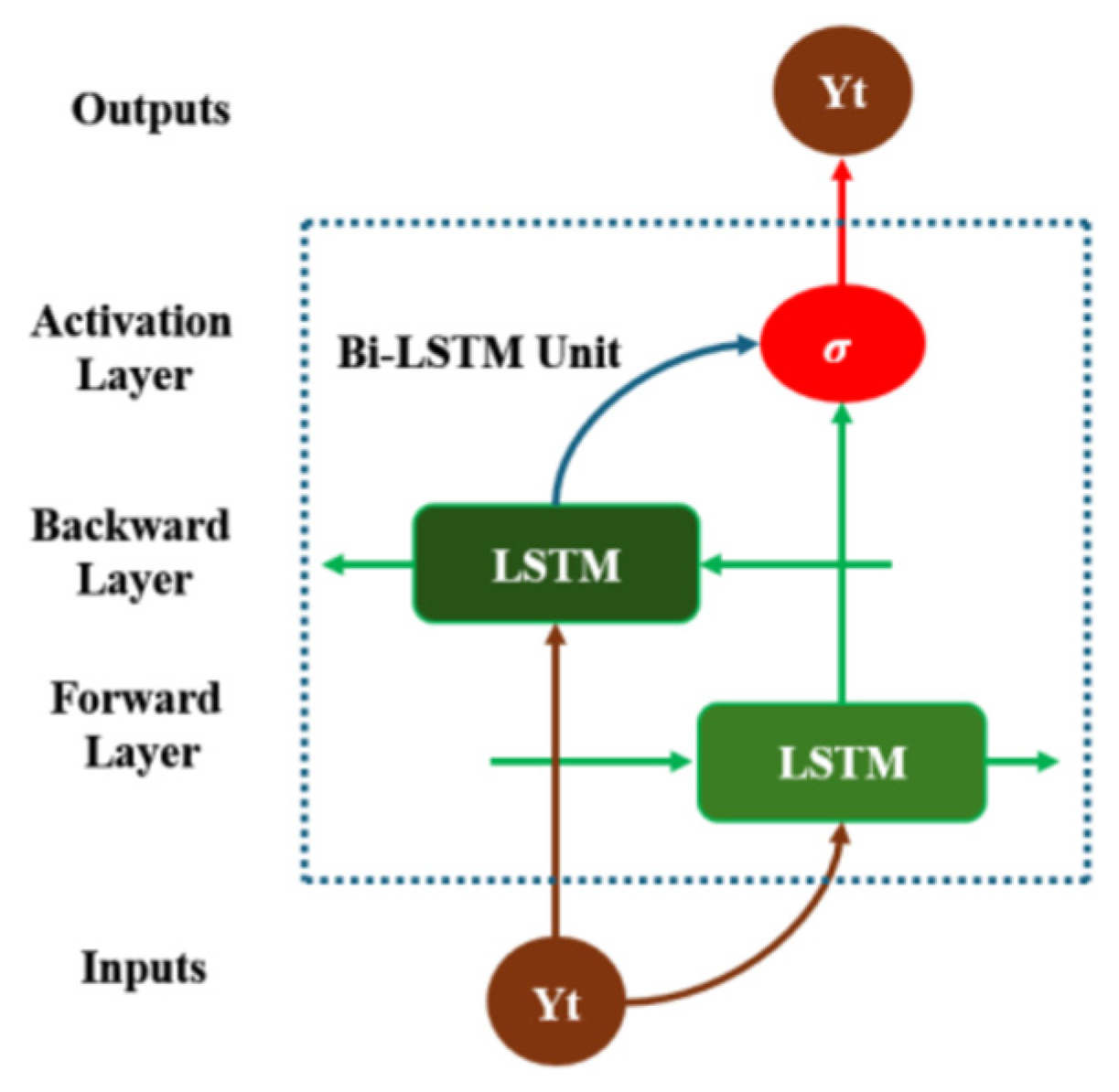

3.4.4. 1D-CNN-Bi-LSTM

Although LSTM has been widely applied in fields such as time series prediction and natural language processing, its application in the specific domain of water pipeline leakage detection is relatively rare [

41]. However, by integrating Bi-LSTM with 1D-CNN and introducing it into pipeline leakage detection, a new and effective solution has been provided for this field, which can more accurately identify and classify leakage signals and has practical application value. The Bi-LSTM layer receives the feature sequences extracted and processed by 1D-CNN as input, rather than directly processing the original data of pipeline leakage. Through the deep integration with 1D-CNN, Bi-LSTM can focus more on learning the long-term patterns and dynamic characteristics in the sequence data, improving the model’s ability to model complex sequence data. Finally, the Bi-LSTM layer is followed by a dropout layer (Dropout Layer = 0.4) and a fully connected layer (Fully Connected Layer, Dense = 3). The dropout layer is used to prevent overfitting by randomly discarding a certain proportion of neurons to enhance the model’s generalization ability. The fully connected layer maps the output of the Bi-LSTM layer to the output space of the classification task to improve the model’s performance.

The number of hidden units in the Bi-LSTM layer is dynamically determined by round (pop (3)), and pop (3) mainly refers to the third element in the arrays popmin and popmax of PSO in the following text. The number of hidden units is dynamically adjusted through the optimization of PSO, automatically optimizing the structure of the LSTM layer according to different levels of leakage datasets and improving the model’s performance and generalization ability.

The 1D-CNN-Bi-LSTM model, as shown in

Figure 12, combines the features of both 1D-CNN and Bi-LSTM architectures. Compared with the traditional network (recurrent neural network), Bi-LSTM has higher prediction performance in predicting time series data with long dimensionality and multivariate, it passes the extracted multivariate temporal features through memory gates such as forgetting gates, inputs, and outputs sequentially. Initially, the convolutional layer of 1D-CNN is employed to automatically extract features from the multi-featured variables of the leakage signal of the water supply pipe. Subsequently, the extracted features from the convolutional layer are transformed using the ReLU activation function. The nonlinear transformation of the activation function enhances the network’s ability to extract expressions. Ultimately, the Bi-LSTM transmits the extracted multivariate temporal features through memory gates, including forgetting gates, inputs, and outputs, in a sequential manner to categorize the leakage signals of varying types according to the extracted features.

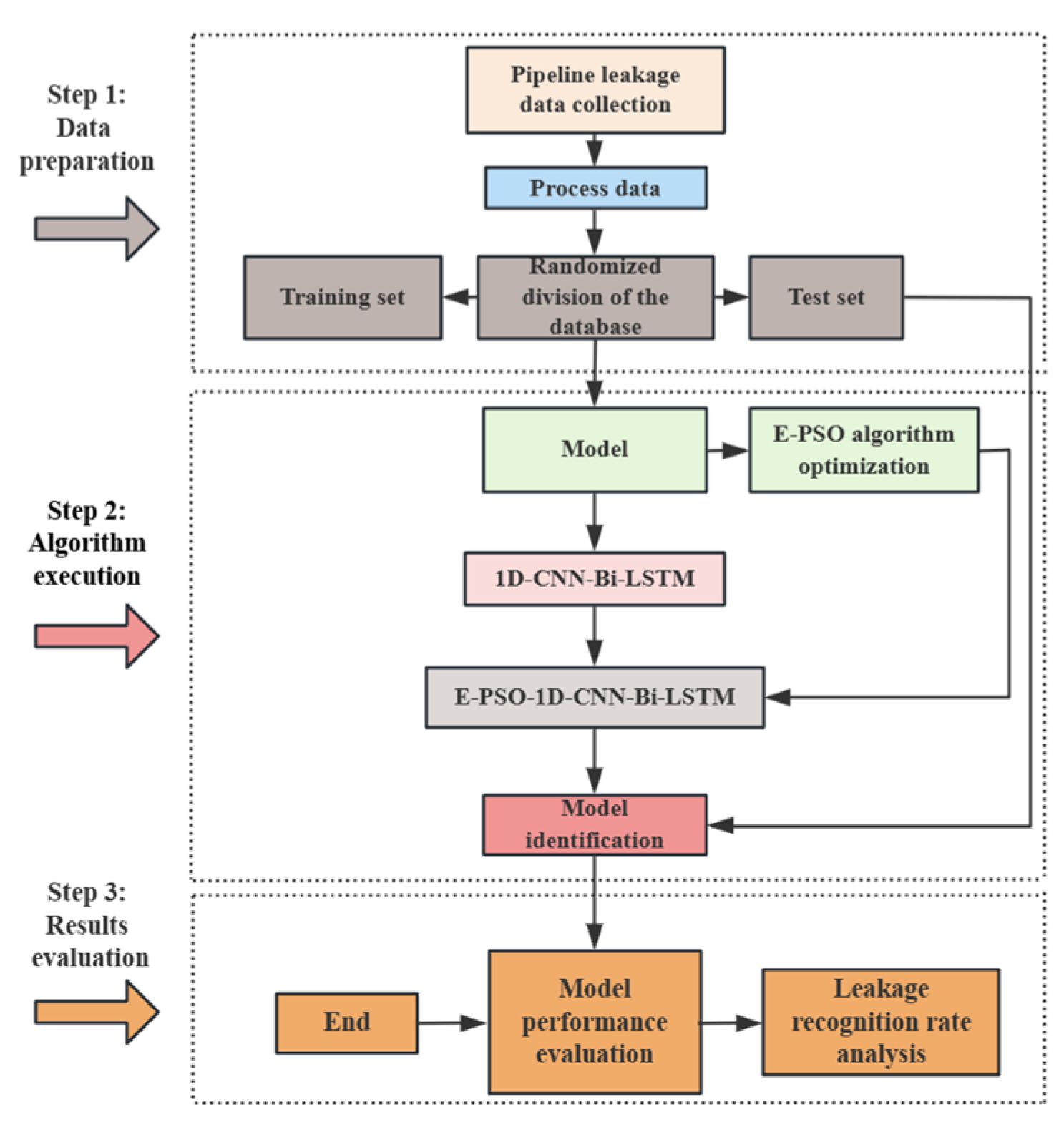

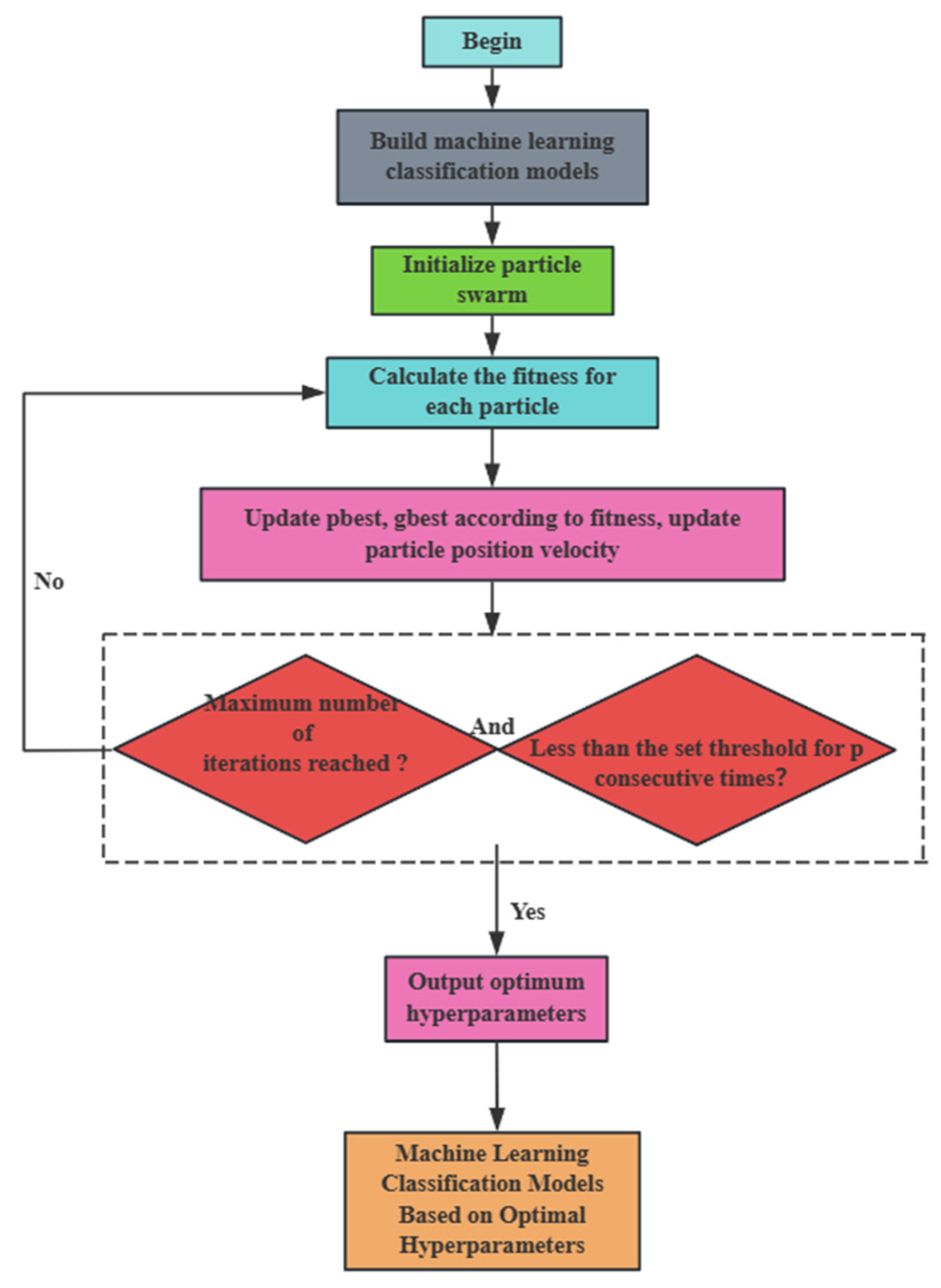

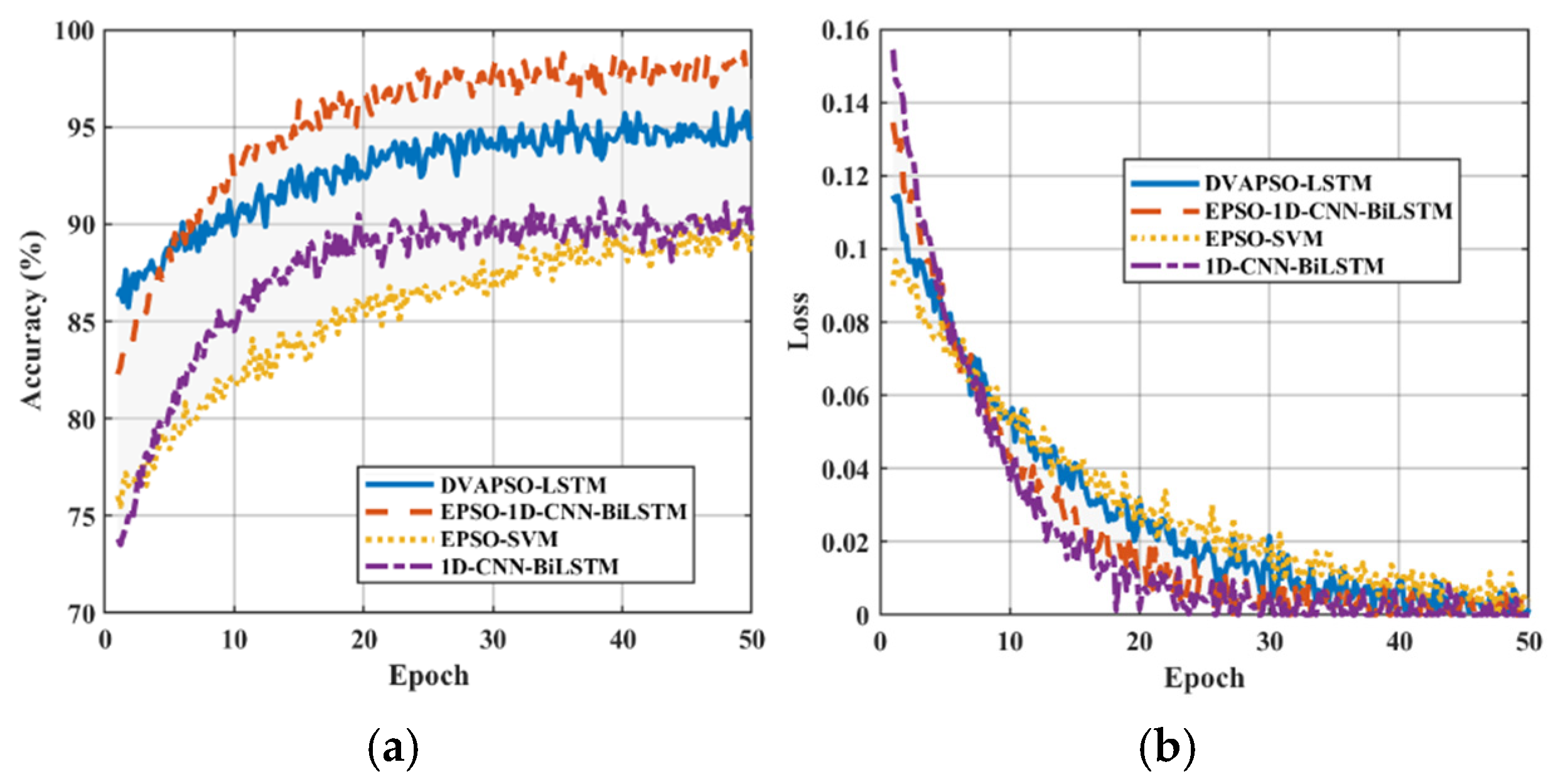

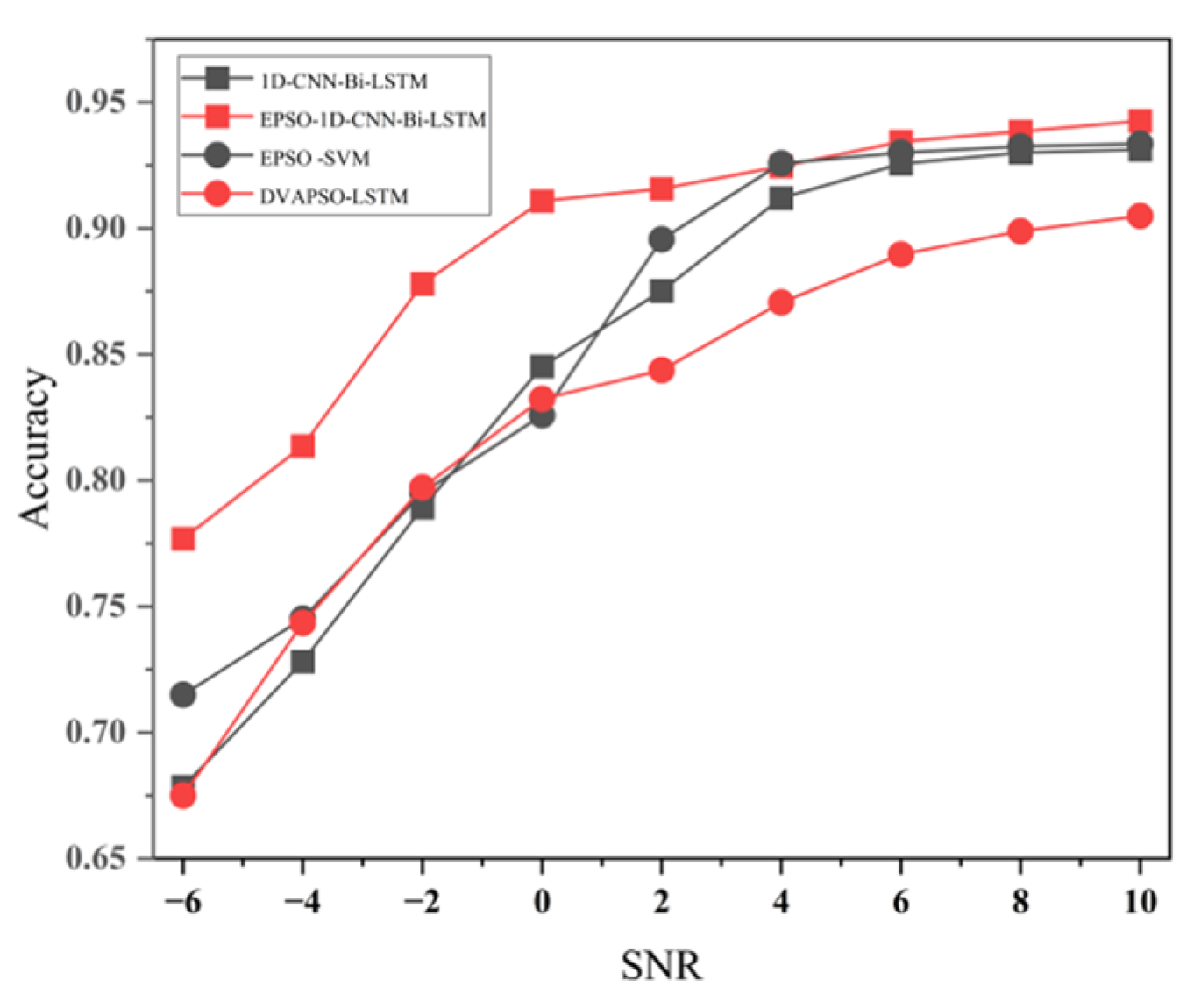

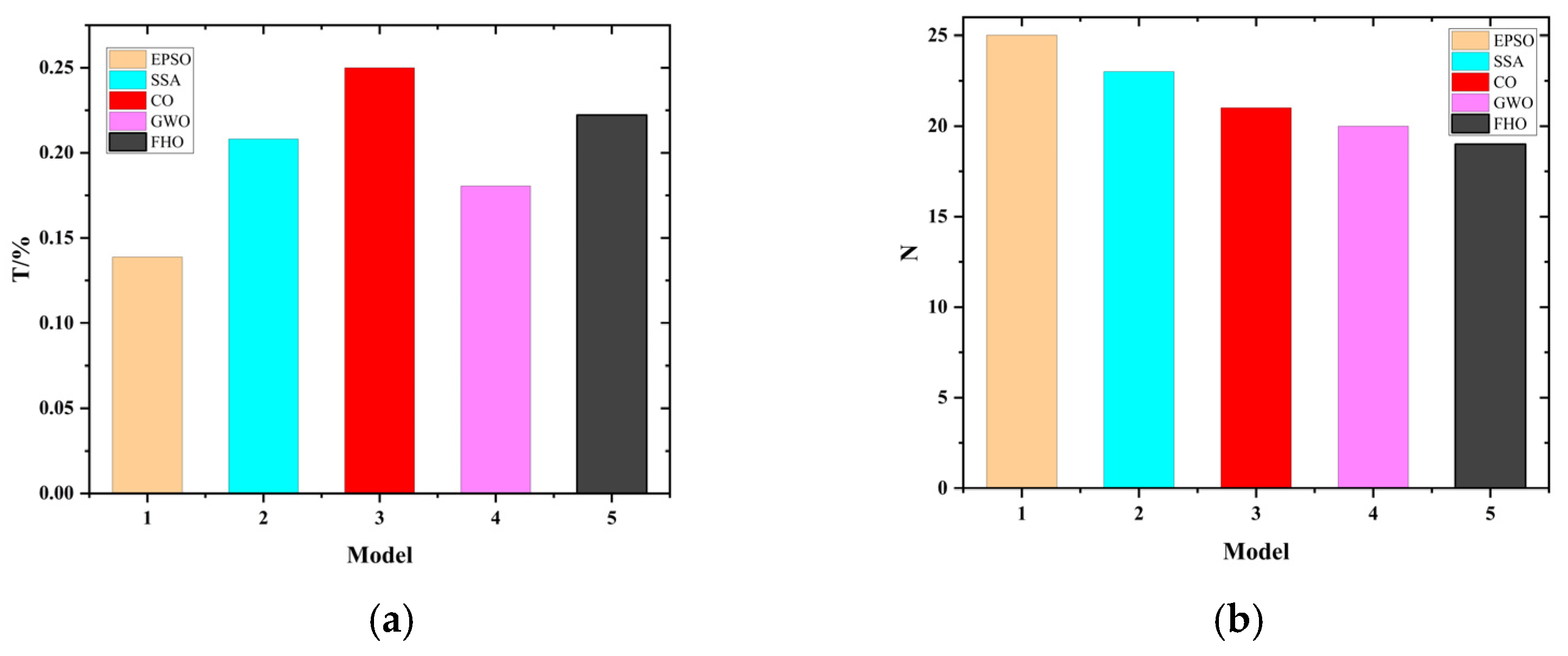

3.4.6. EPSO-1D-CNN-Bi-LSTM

When identifying pipeline leaks, the optimized EPSO-1D-CNN-Bi-LSTM model adopts a continuous iterative process. By establishing 1D-CNN and Bi-LSTM models suitable for pipeline leak detection, and then combining them, the EPSO algorithm is used to dynamically adjust the key parameters in the 1D-CNN-Bi-LSTM model to adapt to different leak datasets in the water supply pipeline. In this model, the prediction performance of different hyperparameter combinations varies. The key hyperparameters for the 1D-CNN-Bi-LSTM model used for pipeline leak classification and identification include learning rate, the number of convolutional kernels, and the number of hidden units (num_hidde_nunits), etc. The key hyperparameters of 1D-CNN-Bi-LSTM are optimized using the EPSO algorithm, which can find the ideal hyperparameter set to enable the model to achieve the highest recognition rate. The detailed process of enhancing the 1D-CNN-Bi-LSTM model using the particle swarm optimization algorithm is as follows:

1. Initialization: The initial solutions are randomly generated as X and V, representing the position and velocity of the birds in the flock, respectively. Each solution is associated with a specific hyperparameter of the model, including but not limited to num_estimators, learning_rate, num_filters, num_hidden_nunits, and so forth.

where

represents the particle count,

,

) indicates the position and velocity of the

ith particle (i.e., a set of hyperparameter values), and D signifies the dimension.

2. Calculate the fitness: This investigation deals with a multi-classification problem, where the fitness function is defined as the model’s accuracy on the validation set.

3. Particle velocity and position update: The formula for the

dth-dimensional velocity update for the

ith particle at each iteration is as follows:

where w is the weight,

is the velocity of particle i in the d-dimension at k iterations,

is the current position of particle i in the d-dimension at k iterations,

is the position (i.e., the coordinates) of the individual extremum of particle i, and

is the position of the global extremum of the entire population, and

,

are random numbers between [0, 1]. D stands for dimension,

,

are acceleration coefficients (learning factors) that represent the weights of the statistical acceleration toward each particle’s push toward the

and

positions, and

is the particle updating its position based on the updated velocity. w_max represents the initial inertia weight, w_min represents the minimum inertia weight, T_max represents the maximum number of iterations, and K represents the current iteration number. These are used to dynamically adjust the inertia weight. Popmax and popmin are, respectively, the lower and upper bounds of the position, ensuring that each dimension x does not exceed the allowable range. The value of the parameter in question determines whether particles will be able to remain in a state of suspension outside of the target region for a period before being pulled back, or whether they will be propelled with great suddenness towards or beyond the target region.

In the case where is equal to zero, the particle is devoid of cognitive capacity and is prone to converging on a local extremum as a result of particle interactions. Conversely, if is equal to zero, there is an absence of social information sharing among particles, and the algorithm turns into a randomized search with multiple starting points; if c1 = c2 = 0, the particles will keep on flying at the current speed until they reach the boundary. Usually c1, c2 is between [0, 4], here c1 = c2 = 2.5 is taken.

4. Update individual optimal position and global optimal position: Evaluate each particle’s current position fitness against its historical best, and update the optimal position if the current one is better, following these specific conditions:

The global optimal position is chosen from the individual best positions of all particles based on the highest fitness:

In this context, i represents the size of the particle swarm.

5. Whether to terminate: That is to say, define the maximum number of cycles or attain a certain level of fitness or other conditions as the criteria for stopping. Upon achieving a satisfactory end, deliver the global optimal position, meaning the best hyperparameter combination; otherwise, revert to step 3 to proceed with the iteration.

In this context, n represents the number of iterations.

6. Moreover, to prevent the algorithm from getting stuck during the search process for an extended period, an early stopping mechanism is introduced under certain circumstances. The improvement of the global optimal fitness during the iterative process is recorded. If the improvement of the global optimal fitness is less than a certain threshold for several consecutive iterations (set as patience times), the early stopping will be triggered.

Among them, F_mink represents the global optimal fitness of the

p-th generation. As illustrated in

Figure 13, the PSO-CNN-LSTM model is depicted as a flowchart. The optimal hyperparameter combination of this machine model is finally obtained after many iterations, after which the hyperparameter combination is utilized for model training and classification processing, and finally, the pipeline leakage and leakage degree are effectively identified.