1. Introduction

Against the backdrop of continuous breakthroughs in deep space exploration technology, performance requirements for spacecraft in terms of resolution, stability, and pointing accuracy are becoming increasingly stringent [

1,

2,

3]. The impact of disturbances such as vibrations on such spacecraft is particularly significant [

4,

5], such as the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) [

6] and the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) [

7,

8]. Even if only a 1 N microvibration load is applied to the optical payloads of spacecraft, it will cause severe degradation of imaging quality, reaching an unacceptable level. As a unique mechanical phenomenon in the microgravity environment, microvibration has implications far beyond the literal meaning of “low-level disturbance”. This type of vibration spans a wide frequency range, extending from near-static sub-hertz levels up to kilohertz levels, covering the critical operating frequency bands of various sensitive payloads on spacecraft [

9,

10]. Its sources are complex and diverse, such as the pulsed operation of attitude control engines, the high-speed rotation of reaction wheels, the reciprocating motion of refrigeration compressors, and the thermally induced jitter of solar panels [

11,

12,

13]. Due to the obvious differences in vibration characteristics among different vibration sources, during the microvibration suppression process, it is necessary to carry out adaptive suppression designs based on specific vibration source characteristics to effectively reduce the accumulation and amplification effects of vibrations [

14,

15]. Thus, mastering the vibration responses of the vibration sources is particularly important.

As China’s largest and most sophisticated next-generation space-based astronomical telescope, the China Space Station Telescope (CSST) features a 2-m primary mirror aperture [

16,

17,

18], with a survey field of view of 1.1 × 1.0 square degrees and an angular resolution close to that of the HST. The radius encircling 80% energy of the point spread function is required to be no more than 0.15″ [

19,

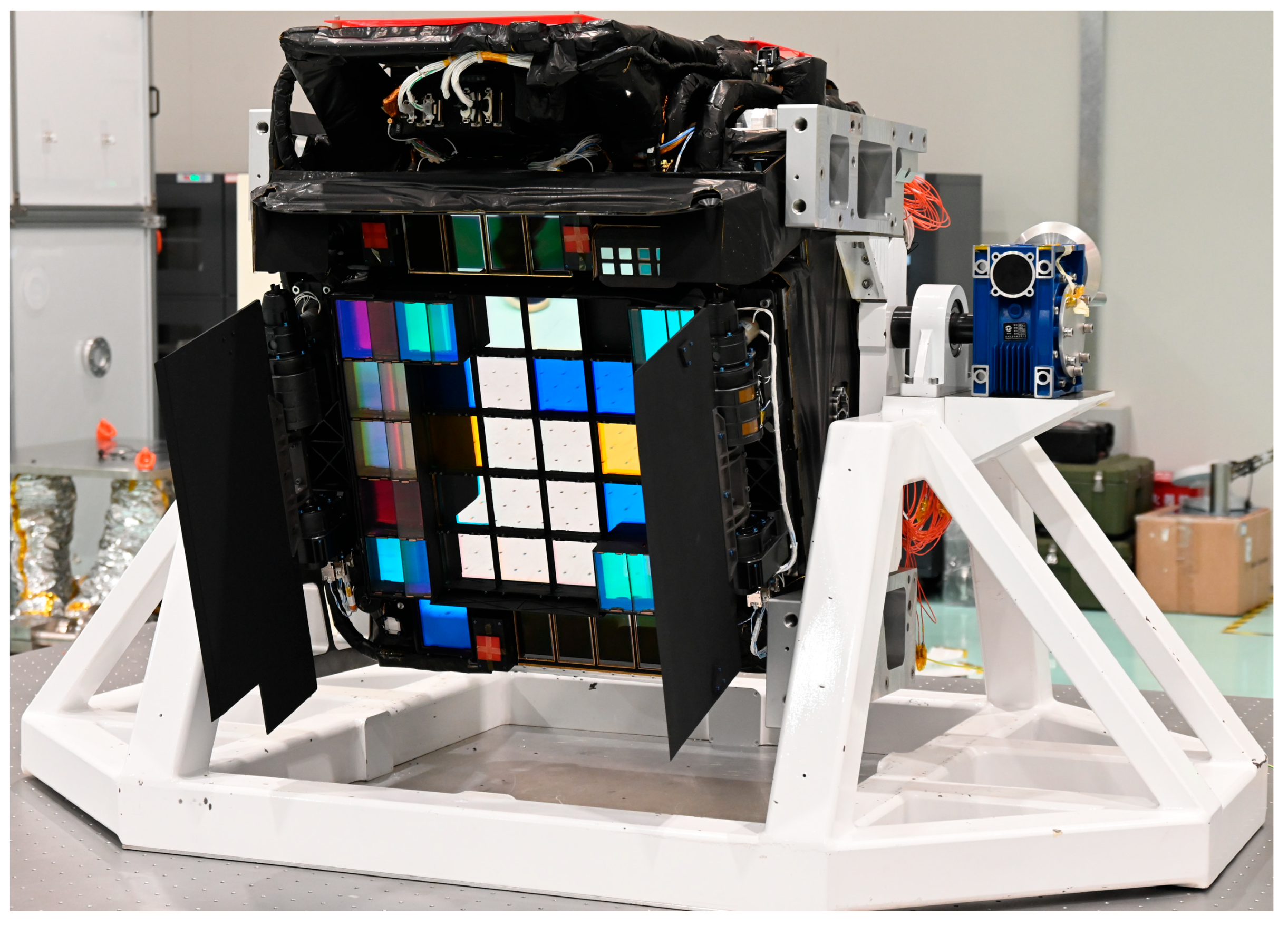

20], including all wavefront errors and dynamical effects (microvibration). The Survey Camera (SC, as shown in

Figure 1), a core observational instrument aboard the CSST [

21], is assigned 70% of the total observational tasks. Its design prioritizes high-resolution, large-scale multiband imaging capabilities, with a primary focal plane size of 500 × 600 mm and equipped with 3.3 billion pixels. The SC is expected to exceed GAIA [

22,

23] and become the space astronomical camera with the highest number of pixels to date. Inside the SC, the Cryocooler Assembly (CCA) serves as an inherent vibration source. This assembly operates continuously during the camera’s imaging process, and its operational vibrations are transmitted to the CSST through paths such as the camera’s support structure and heat pipes, inducing jitter of the telescope’s optical axis [

24]. This results in displacement of the observed target relative to the detector during exposure, thereby significantly degrading the spatial resolution of the images. Therefore, it is particularly critical to gain an in-depth understanding of the microvibration response characteristics of the SC and to conduct adaptive design of the telescope based on its response laws to weaken the transmission and amplification effects of microvibrations.

Currently, the prevalent method for evaluating microvibration responses of space payloads is to conduct microvibration tests on them under blocked or infinite-impedance configurations, where force sensors are used to quantify microvibration responses at the interface [

25]. However, for test objects such as SC, which feature large inertia, high stiffness, and discrete interfaces, it is difficult for the test system to ensure that the test object meets the blocked or infinite-impedance installation conditions. This leads to structural coupling between the two after installation, thereby causing the test results to fail to truly reflect the microvibration response of the test object. The core issue lies in how to extract the true microvibration response of the test object from the microvibration test results when there is a high degree of structural coupling between the test system and the test object.

In the field of coupled microvibration research, reference [

26] characterize the structural coupling effect between the flywheel and the spacecraft mounting surface by introducing a force filter. This force filter mainly consists of three components: first, the spacecraft transfer function obtained through finite element analyses; second, the point dynamic mass at the mounting points of the flywheel assembly tested under static conditions; third, the microvibration response of the flywheel assembly under blocked or infinite-impedance installation conditions. Similar studies have been conducted in references [

27], which incorporate the gyroscopic effect generated during the rotation of the flywheel. It is worth noting that the reverse application of this method can achieve the decoupling of microvibration tests for vibration sources—specifically, starting from the tested microvibration response under the coupled state, it can back-calculate the microvibration response of the vibration source under blocked or infinite-impedance installation conditions. However, this method has certain limitations and is only applicable to scenarios where the stiffness of the test system is significantly higher than that of the test object, and the mounting interface between the two is in a clear and single series connection form.

Another commonly used approach is the substructuring method, which decomposes the global structure into independent substructures and achieves dynamic analysis by satisfying interface compatibility and equilibrium conditions [

28]. Typical implementations such as component mode synthesis rely on clear substructure partitioning and accurate acquisition of interface dynamic parameters. However, for the SC, there are multiple mounting interfaces with large spans between them, resulting in a lack of distinct installation boundaries between the test object and the test system, as well as significant multi-path coupling effects in vibration transmission. These characteristics make the partitioning of substructures and the validation of interface condition assumptions extremely challenging, thus greatly restricting the direct application of the substructuring method.

In addressing structural coupling issues during spacecraft vibration testing, virtual testing has emerged as a comprehensive framework that models the full interaction between the test facility, specimen, and control system, encompassing nonlinear and transient effects [

29]. This technique has been extensively validated by the European Space Agency (ESA) for complex spacecraft testing scenarios. Notably, ESA developed virtual testing platforms for its QUAD and HYDRA shakers in the late 2010s, successfully applying them to missions such as BepiColombo (a joint ESA/JAXA Mercury exploration mission) and tests with the TEDY mass dummy spacecraft [

30]. The HYDRA 6-axis shaker, capable of simultaneous multi-degree-of-freedom transient testing, was integrated into a virtual model that included MTS control systems and high-fidelity finite element models of test specimens. This integration revealed that structural coupling between the shaker and spacecraft could alter fundamental modal frequencies by over 20% and affect more than 39% of resonance modes, highlighting the criticality of full-system modeling [

30]. Virtual testing not only improved post-test correlation accuracy (with FRAC values increasing by an average of 0.2) but also enabled reliable pre-test prediction of unexpected dynamic behaviors, overcoming the limitations of traditional finite element analysis that neglects facility-induced uncertainties [

30]. Building on the full-system dynamic modeling philosophy of virtual testing, this paper proposes a targeted microvibration testing and decoupling method for large-inertia, high-stiffness payloads with discrete interfaces (e.g., the Survey Camera, SC). It introduces a closed-loop decoupling process consisting of “model establishment—model validation—test system stripping—intrinsic response extraction”, which efficiently separates the intrinsic microvibration characteristics of the test object from the coupling interference of the test system. This thus provides an engineering-feasible solution for microvibration testing of similar large-inertia, high-stiffness payloads with discrete interfaces.

In view of payloads such as the SC, which feature large inertia, high stiffness, as well as multiple and discrete mounting interfaces, this paper proposes a semi-physical simulation method for their microvibration testing and decoupling. In this paper,

Section 2 describes the vibration sources and transmission path of the SC and the composition of Microvibration Testing System.

Section 3 establishes coupled dynamic models for the SC and MVTS and identifies challenges in decoupling due to multiple paths and dynamic mass acquisition.

Section 4 proposes a semi-physical simulation method.

Section 5 describes in detail the testing of the SC and the decoupling process of its microvibration responses.

2. Structural Coupling Between the Survey Camera and Microvibration Testing System

All individual units of the SC are integrated into a support structure fabricated from M55J carbon fiber composite material. This support structure adopts a high-stiffness design, and its fundamental frequency exceeds 100 Hz when fully loaded with fixed mounting interfaces. As the vibration source of the SC, the Cryocooler Assembly (CCA) internally integrates four pulse tube cryocoolers (PTCs), among which three are used to cool the focal plane array to below 185 K, and one is utilized to cool the short-wave infrared detector to below 80 K. Each group of cryocoolers is equipped with a compressor. During the operation of the cryocoolers, the piston inside the compressor reciprocates to drive the working fluid to flow, thereby achieving refrigeration. The operating frequency of the compressor can be adjusted within the range of 75–85 Hz, with additional vibrations occurring at its 2nd and 3rd harmonics. To reduce the vibration of the CCA, vibration isolators are installed between the CCA and the support structure of the SC. After vibration isolation, the natural frequency of the CCA is about 10 Hz. Vibrations generated by the CCA are transmitted to the SC through the vibration isolators and heat pipes, and then transferred from the SC to the CSST via the mounting interfaces. The mounting interfaces of the SC are illustrated in

Figure 2, with four interfaces (A, B, C, and D) distributed in four directions. In the shutter-closed state, the SC has dimensions of 895 mm × 1047 mm × 1047 mm and a launch mass of 450 kg.

Microvibrations transmitted from the SC to the CSST can cause jitter in the optical axis of the telescope. The Fast Steering Mirror (FSM) configured in the optical system of CSST possesses precise image stabilization capabilities, which can effectively compensate for the impact of low-frequency vibrations below 8 Hz on imaging. However, for the typical 75–80 Hz vibrations generated by the cryocooler, the dynamic response capability of the FSM is limited, making it difficult to achieve complete suppression. The residual optical axis jitter after compensation by the FSM will cause the observed target to displace relative to the detector during exposure, thereby significantly reducing the spatial resolution of the image. According to the decomposed requirements of the telescope specifications, within the frequency range of 8–300 Hz, the root mean square (RMS) values of the vibration force and vibration torque transmitted from the SC to the CSST must be controlled to ≤0.4 N and ≤0.1 N·m, respectively.

To verify whether the microvibration response of the SC meets the requirements, a microvibration test was conducted. The microvibration test system (MVTS) employed in the test is illustrated in

Figure 3. This system integrates four Kistler 9347C force sensors—IEPE-type triaxial sensors with sensitivities of −8 pC/N (for Fx and Fy directions) and −3 pC/N (for Fz direction)—which are symmetrically mounted between the foundation and the carbon fiber mounting baseplate. The total test force and torque were derived from the measured forces of the four sensors and the distances between them.

The force sensors convert mechanical forces into electrical signals, which are then amplified by a charge amplifier (Kistler 5080A; measuring range: ±2~±2,200,000 pC; measurement uncertainty: 0.3%) and transmitted to a data acquisition computer for processing. The MVTS enables high-precision measurements with a force measuring range of 600 N and a torque measuring range of 12 N·m, achieving a force resolution of 0.005 N and a torque resolution of 0.001 N·m.

The SC is connected to the mounting base plate via a dedicated connecting fixture, as shown in

Figure 4.

The vibration transmission path after the SC is connected to the MVTS is shown in

Figure 5. Due to the SC itself having characteristics of large inertia and high stiffness, and its mechanical mounting interfaces adopting a distributed design, structural coupling is formed between the SC and the MVTS after they are connected. This coupling leads to differences in dynamic characteristics between the SC-MVTS coupled system and the standalone SC, thereby making the tested microvibration response unable to truly reflect the microvibration response of the SC itself.

To verify the differences in dynamic characteristics between the SC itself and the SC-MVTS coupled system, finite element models (FEMs) of both were established, and their respective vibration transmissibility curves were analyzed. In

Figure 6, the blue curve represents the vibration transmissibility curve from the CCA mounting interface to the SC mounting interface (where the four mounting interfaces A, B, C, and D are connected via rigid elements, with the independent point of the rigid elements set at the centroid of the SC). The red curve represents the vibration transmissibility curve from the CCA mounting interface to the force sensor mounting interface of the MVTS. The two curves show significant differences: the stiffness of the coupled system is significantly lower than that of the SC itself, and multiple resonance peaks appear within the excitation frequency range of the CCA, which will lead to an overestimation of the tested microvibration response.

3. Coupled Microvibration Analysis Model

To eliminate the influence of the MVTS on the micro—vibration testing of the SC, a Coupled Microvibration Analysis Model is established to analyze the coupling principle. Under the excitation of the CCA, the microvibration force and torque responses of the SC can be expressed as:

where

is the disturbance force and torque of the CCA, and is a known quantity, and

is the microvibration response of the SC; the resultant force and resultant torque of all interfaces constitute the microvibration force and torque responses of the SC.

is the transfer function of the SC relating

to

. The key to the problem lies in obtaining

. Due to the dispersed interfaces of the SC, the excitation from the CCA will be transmitted to each interface through different paths, making the solution of

challenging.

For a flexible body with a limited volume, discretized into a finite number of degrees of freedom (DOF), and subjected to external forces and torques, the corresponding equation of motion (EOM) is:

In the equation, M is the mass matrix, C is the damping matrix, K is the stiffness matrix, x is the vector of displacements and rotations, and F is the vector of forces and torques.

By performing the Laplace transform on Equation (1) and assuming the initial condition of

x(

t) is zero, we obtain:

which can be written in the following form:

The transfer function matrix

, which links the applied loads

to the accelerations

, is defined as follows:

is a 6 × 6 matrix with all elements dependent on frequency. This matrix stands for the “driving-point” dynamic mass of the flexible body, which characterizes the relationship between the load force applied at this point and the acceleration.

Figure 7 shows the schematic diagram of coupling between the SC and the MVTS. The SC equation of motion (EOM) is obtained as:

where

is linear and angular accelerations at the SC-MVTS mounting interface,

is the reaction forces and torques at the SC-MVTS mounting interface,

is the driving-point dynamic mass of the SC at the SC-MVTS mounting interface. Due to the comparable inertia and stiffness between the SC and the MVTS,

has changed after connection and coupling. Here,

is introduced to correct the transfer functions of the SC, and it is a 6 × 6 matrix related to frequency.

The MVTS’s equation of motion (EOM) is obtained as:

where

is the vibration forces and torques tested by the MVTS after the system is coupled,

is the transfer function of the MVTS relating

to

,

is the transfer function correction matrix of the MVTS.

is the driving-point dynamic mass of the MVTS at the SC-MVTS mounting interface.

By combining Equations (1) and (6)–(8), the microvibration force and torque responses of the SC are obtained:

Given that the SC and the MVTS do not feature an independent series-mounted interface, with multiple coupling paths involved, the dynamic masses and at the interface are difficult to obtain. Additionally, the transfer function correction matrix and are also difficult to obtain through testing.

4. Principle of Microvibration Decoupling in Semi-Physical Simulation

Analysis of the coupled microvibration model reveals significant difficulties in directly obtaining

through tests and theoretical derivations. To address this issue, a semi-physical simulation method is proposed (schematic diagram shown in

Figure 8), with the specific process as follows:

First, the SC is mounted on the MVTS to construct the SC-MVTS coupled system. Subsequently, modal testing is carried out to identify the inherent vibration characteristics of this coupled system, and meanwhile, transmissibility testing is performed to quantify the vibration transmission laws.

Subsequently, an FEM of the SC-MVTS coupled system is constructed. Based on the test results of modal testing and transmissibility testing, iterative corrections are performed on the model.

Then, to verify the accuracy of the simulation model, microvibration response testing is conducted on the SC-MVTS coupled system. This test can characterize the entire transmission chain from the CCA, through the SC and MVTS, to the force sensors, and is directly related to the force and torque physical quantities of research interest. By comparing the results of the microvibration response testing and simulation analysis, subsequent steps can be carried out only after the two achieve good consistency; otherwise, the model will be further revised.

Once the model is highly consistent with the dynamic characteristics of the actual system, the MVTS is “stripped” from the coupled model, while the FEM of the SC itself is retained. This model fully inherits the corrected dynamic characteristics of the SC, including connection stiffness, damping properties, and modal parameters. Subsequently, the CCA excitation is input into the model, and the micro-vibration response of the SC is calculated independently. This method overcomes the limitations of decoupling analysis on the dynamic behavior of the target object in complex coupled environments, enabling decoupling from “coupled system response” to “intrinsic characteristics of the target object”.

6. Conclusions

For payloads such as the Survey Camera (SC), which feature large inertia, high stiffness, and discrete mounting interfaces, structural coupling tends to occur between the payload and the testing system during microvibration testing, thereby leading to distortions in the test results. Since the vibration transmission in a coupled system is not a simple series superposition, the method of calculating the transfer functions of each link in the transmission path and the coupling correction matrix faces the problem that each component is difficult to obtain, making it hard to achieve microvibration decoupling.

To address this challenge, this paper proposes a semi-physical simulation method to solve the problem of microvibration test decoupling for the SC. Firstly, a coupled system of the Survey Camera-Microvibration Test System (SC-MVTS) is built, and at the same time, the FEM of the SC-MVTS coupled system is constructed. Modal tests and transmissibility tests are conducted on the SC-MVTS coupled system, and the model is iteratively modified based on the test data to make the simulation results as close as possible to the test data, ensuring that the dynamic characteristics of the SC-MVTS coupled system simulation model are consistent with those of the actual system.

Subsequently, the coupled model is validated through microvibration response tests, and the results demonstrate that the simulation results of the modified model are in good agreement with the tested results, and the deviations of the RMS values of the resultant force and torque of the vibration response are within 5%. Then, the MVTS is stripped from the SC-MVTS coupled model to separate the inherent dynamic characteristics of the SC. Based on the excitation of the CCA, the microvibration response of the SC can be calculated, achieving the dynamic decoupling analysis of the complex coupled system. Decoupling analysis indicates that in the frequency range of 8–300 Hz, the RMS values of the microvibration force and torque of the SC are 0.25 N and 0.08 N·m, respectively, meeting the requirements of the SC (≤0.4 N and ≤0.1 N·m).

Future work can be extended in several directions to enhance the practical application and generalization ability of the proposed method. First, the methodology can be adapted to other types of space payloads with diverse structural characteristics (e.g., flexible attachments, multi-source excitation, or irregular interface distributions), expanding its engineering application scope to satellite antennas, precision spectrometers, and other high-precision space instruments. Second, integrating machine learning algorithms (such as neural networks or Gaussian process regression) into the finite element method (FEM) iterative correction process may improve the accuracy and efficiency of the model, especially for complex coupled systems with high-dimensional parameters. Third, formulating a standardized operating procedure for the proposed decoupling method will facilitate its application in industrial testing scenarios, reduce reliance on expert experience, and improve test repeatability. These extensions are expected to provide more comprehensive solutions for the microvibration evaluation and control of high-precision space systems, supporting the development of next-generation deep space exploration missions.