MCS Assisted Accurate Perception Framework for Urban POI Classification

Highlights

- Proposes a hybrid MCS perception framework (MCS-APF) that integrates participatory and opportunistic sensing to achieve high-quality, low-cost urban POI data collection.

- Introduces an improved DBSCAN-H clustering algorithm using Haversine distance for accurate geographic POI clustering, enhancing intra-cluster compactness and inter-cluster separation.

- Enables more efficient and accurate urban POI classification, supporting better decision-making in urban planning and sustainable development.

- Provides a scalable and cost-effective solution for large-scale urban sensing applications, with potential extensions to other spatial data analysis domains.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- In the participatory perception mode, a high-quality worker recruitment algorithm based on a genetic algorithm named WR-GA is designed to recruit high-quality workers to perform perception tasks, collect high-quality POI data, and ensure high accuracy.

- An improved DBSCAN algorithm named DBSCAN-H is designed to represent the actual distance between position sample points through Haversine distance to ensure the accuracy of clustering results.

2. Related Works

2.1. POI Perception

2.2. Mobile Crowd Sensing

2.3. Clustering Algorithm

3. System Model

3.1. Stakeholders and Role Definition

3.2. Overall Workflow of MCS-APF

3.3. Urban POI Perception Based on Mobile Sensing Data

4. Methods of MCS-APF

4.1. WR-GA Based on POI Quality

- Calculate the fitness of each individual in the group and the fitness of the i-th individual is recorded as

- Calculate the probability of the i-th individual being inherited by the next generation.

- Calculate the cumulative probability of the i-th individual.

4.2. Urban POI Perception Algorithm Based on DBSCAN Clustering

- Neighborhood: Given any sample point , the area within the radius of is called the neighborhood of the sample point . is called the neighborhood radius.

- Core point: If the neighborhood of a given sample point contains at least sample points, then point is called a core point. is called the minimum number of points in the cluster.

- Density direct access: For sample set D. If a sample point is in the neighborhood of , and is the core point, then the sample points to are said to be a direct about the density of and .

- Density reachable: For a sample set D, given a series of sample points , , . If the sample point is directly accessible from density, then sample point a to sample point b is density reachable concerning and

- Density connection: There is a point o in the sample set D, if the sample point is density reachable to point and point , then and are density connected.

| Algorithm 1. POI Perception Based on DBSCAN-H |

| Input: Collection of sample points . Output: Clustering result . 1: = 0//Initialize the number of clusters to 0 2: Compute the k-distance for each sample point to obtain the neighborhood radius . 3: Calculate the average expectation of the number of sample points within all neighborhood radii to obtain the minimum number of points in the cluster, . 4: for each unvisited point in the sample set do 5: Mark p as visited 6: Compute the number of sample points N within the neighborhood radius of point 7: if < then 8: Mark as a noise point 9: else 10: Create a new cluster 11: Add to cluster 12: for each unvisited sample point within do 13: Mark as visited 14: Compute within of point 15: if > then 16: 17: end if 18: if does not belong to any other cluster then 19: Add to cluster 20: end if 21: end for 22: end if 23: end for 24: return C |

5. Experiments and Results

5.1. WR-GA Experimental Result and Analysis

5.1.1. Experimental Parameter Setup

5.1.2. Baseline Algorithm

- (a)

- Quality Greedy Recruitment Algorithm (Q-Greedy). The processing of this algorithm is to recruit workers who can provide maximum data quality until the budget of the sensing platform is exhausted.

- (b)

- Quantitative Greedy Recruitment Algorithm (N-Greedy). The algorithm proceeds to recruit the workers that require the least amount of compensation until the perceived platform budget is depleted.

- (c)

- Traditional Recruitment Algorithm (Traditional). This algorithm uses a traditional algorithm with criteria for recruiting workers until the budget is exhausted, given a certain budget for the perceptual platform.

5.1.3. Evaluation of Indicators

- (a)

- Sum of Perceived Data Quality. The sum of perceived data quality values represents the total quality of data that the platform can submit from several recruited workers. This metric can be calculated by,

- (b)

- Average perceived data quality. The average perceived data quality refers to the sum of the quality of the data that can be submitted by several workers after they have been recruited by the perception platform, divided by the number of workers

5.1.4. Analysis of the Results of WR-GA

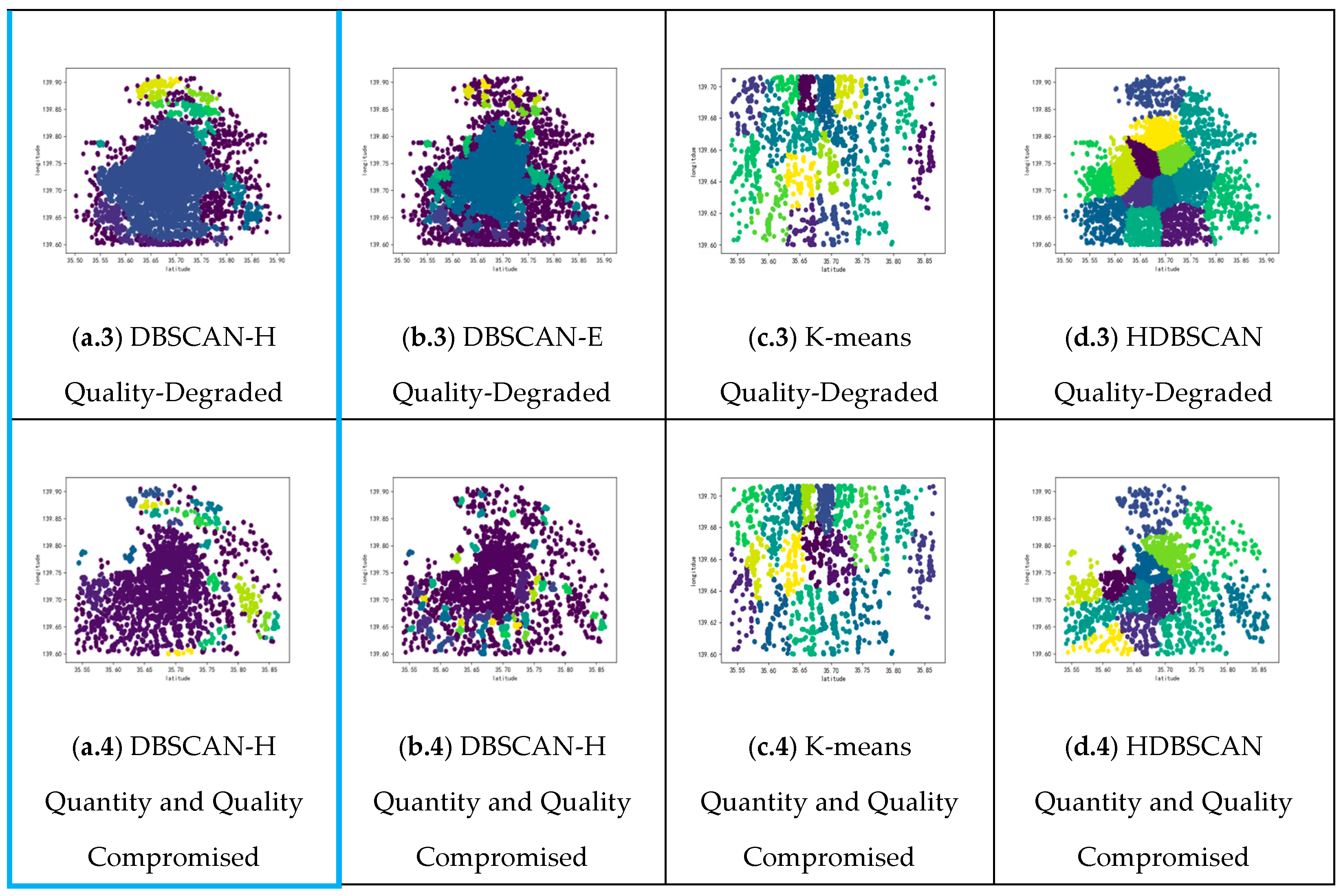

5.2. DBSCAN-H Experimental Result and Analysis

5.2.1. Parameter Setup

5.2.2. Baseline Algorithms

- Traditional DBSCAN algorithm [29] (DBSCAN-E): This algorithm aims to analyze the business structure characteristics of a city by using the DBCAN algorithm on its restaurant and shopping POI data. The algorithm identifies domain moves and cluster minima in the following manner:where represents the average sum of distances between nearby POIs surrounding the ith central point, k indicates the count of neighboring POIs nearest to the central point, and n stands for the total POI count. Once the parameter is determined, the minimum number of points required for clustering is calculated as the expected value of the number of points within the domain radius of each point.where is the number of sample points in the domain of sample points.

- K-means clustering algorithm [27]: K-means clustering is an unsupervised learning and partitioning algorithm used for clustering. It involves dividing a collection of samples into k subsets, which in turn constitute k classes. This study uses the K-means algorithm to perform cluster analysis of POI data associated with metro stations for fine-grained categorization of the stations.

- HDBSCAN algorithm [26]: As an advanced density-based algorithm, HDBSCAN is known for its ability to find clusters of varying densities without requiring the parameter. We used the hdbscan Python library with its default parameters, setting min-cluster-size to 15 to ensure a fair comparison with the parameter used in DBSCAN-based methods.

5.2.3. Evaluation of Indicators

- Index: The CH index (Calinski–Harabaz Index) quantifies the closeness of a class by computing the sum of the squares of the distances between each point within the class and its center, as well as the separation of the dataset by computing the sum of the squares of the distances between each class center and the center of the entire dataset. The value of the CH index is then obtained by dividing the separation measure by the closeness measure. A higher CH index indicates that the class is more tightly clustered and less dispersed, resulting in better clustering outcomes. Here is the specific representation of the CH index:where denotes the number of training samples in the dataset, k denotes the number of categories, denotes the covariance matrix between categories, denotes the covariance matrix between sample points within a class, and denotes the trace of a matrix.

- Index: The index (Davies–Bouldin index), also known as the Classification Accuracy Index, is a significant measure utilized for evaluating the capabilities and limitations of clustering algorithms. The Davies–Bouldin index (DBI) is computed by dividing the average sum of the distances between pairs of objects within a cluster by the distance separating the cluster centers, and selecting the maximum value. The smaller the resulting value, the better the clustering performance in terms of the smaller intra-cluster distance and larger inter-cluster distance. The formula for the is as follows:where denotes the average distance of each point in class from the center of mass of that class, and denotes the distance between class and the center of mass of class j.

5.2.4. Analysis of the Results of DBSCAN-H

5.3. MCS-APF Perception Result and Analysis

5.3.1. Parameter Setup

5.3.2. Analysis of the Results of MCS-APF

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, W.; Gao, X.Y.; Li, R.S. Multi-Source POI Data Fusion Based on the Spatial Location Information. Period. Ocean Univ. China 2014, 44, 111–116. [Google Scholar]

- WAZE. WAZE [EB/OL]. Available online: https://www.waze.com/ (accessed on 21 April 2023).

- Ra, M.R.; Liu, B.; La Porta, T.F.; Govindan, R. Medusa: A programming framework for crowd-sensing applications. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Mobile Systems, Applications, and Services, Ambleside, UK, 25–29 June 2012; pp. 337–350. [Google Scholar]

- Das, T.; Mohan, P.; Padmanabhan, V.N.; Ramjee, R.; Sharma, A. PRISM: Platform for remote sensing using smartphones. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Mobile Systems, Applications, and Services, San Francisco, CA, USA, 16–19 June 2010; pp. 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- CrowdOS. CrowdOS [EB/OL]. Available online: https://www.crowdos.cn/ (accessed on 21 April 2023).

- Kennedy, L.S.; Naaman, M. Generating diverse and representative image search results for landmarks. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on World Wide Web, Beijing, China, 21–25 April 2008; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisilevich, S.; Mansmann, F.; Keim, D. P-DBSCAN: A density based clustering algorithm for exploration and analysis of attractive areas using collections of geotagged photos. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference and Exhibition on Computing for Geospatial Research & Application, Washington, DC, USA, 19–21 April 2010; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2010; p. 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.Y.; Gong, Z.G.; U, L.H. Identifying points of interest by self-tuning clustering. In Proceedings of the 34th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Beijing, China, 24–28 July 2011; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 883–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.Y.; Gong, Z.G.; U, L.H. Identifying Points of Interest Using Heterogeneous Features. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2015, 5, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, K.; Toda, H.; Kurashima, T.; Suhara, Y. Probabilistic identification of visited point-of-interest for personalized automatic check-in. In Proceedings of the 2014 ACM International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–17 September 2014; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 631–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Wang, M.; Hu, Q. A POI data update approach based on Weibo check-in data. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Geoinformatics, Kaifeng, China, 20–22 June 2013; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Duan, Y.; Wang, X.; Huang, Z.; Xie, N.; Shen, H. Hierarchical Multi-Clue Modelling for POI Popularity Prediction with Heterogeneous Tourist Information. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2019, 31, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Zhu, H.; Zhou, B.; Lu, C.; Sun, M.; Ma, X.; Fan, X.; Wang, C.; Chen, L. CrowdPatrol: A Mobile Crowdsensing Framework for Traffic Violation Hotspot Patrolling. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2021, 20, 3858–3871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Liu, C.; Chen, K.; Gui, D.; Du, Q. A tourist attraction recommendation model fusing spatial, temporal, and visual embeddings for flickr-geotagged photos. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, Z.; Chen, X. Quality-aware user recruitment based on federated learning in mobile crowd sensing. Tsinghua Sci. Technol. 2021, 26, 869–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Shi, Z.; Li, M.; Mao, S. MaskPOI: A POI Representation Learning Method Using Graph Mask Modeling. Electronics 2025, 14, 1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Tan, G.; Shi, Z. Recommending Tourism Attractions Based on Segmented User Groups and Time Contexts. Data Anal. Knowl. Discov. 2020, 41, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Wang, F.; Xiong, H.; Chen, C.; Lv, Q.; Qiu, Z. Multi-Task Allocation in Mobile Crowd Sensing with Individual Task Quality Assurance. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2018, 17, 2101–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.; Liu, J.; Liang, Z.; Ding, K. Based on Bid and Data Quality Incentive Mechanisms for Mobile Crowd Sensing Systems. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work in Design, Nanjing, China, 18–20 May 2022; pp. 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Liu, C.H.; Tang, J.; Yang, D.; Hui, P.; Wang, W. Online Quality-Aware Incentive Mechanism for Mobile Crowd Sensing with Extra Bonus. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2019, 18, 2589–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Su, L.; Chen, D.; Guo, H.; Nahrstedt, K.; Xu, J. Thanos: Incentive Mechanism with Quality Awareness for Mobile Crowd Sensing. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2019, 18, 1951–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ma, J.; Jin, Q. MARCS: A Mobile Crowdsensing Framework Based on Data Shapley Value Enabled Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2025, 82, 4431–4449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Song, W. Intelligent Task Allocation for Mobile Crowdsensing With Graph Attention Network and Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2023, 10, 1032–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, H.; Bai, G. Task Partitioning and Scheduling Based on Stochastic Policy Gradient in Mobile Crowdsensing. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 2024, 11, 6580–6591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immanuel, S.D.; Chakraborty, U.K. Genetic algorithm: An approach on optimization. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Communication and Electronics Systems, Coimbatore, India, 17–19 July 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 701–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnes, L.; Healy, J.; Astels, S. hdbscan: Hierarchical density based clustering. J. Open Source Softw. 2017, 2, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A.; Pandey, H.M.; Mehrotra, D. Comparative review of selection techniques in genetic algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Futuristic Trends on Computational Analysis and Knowledge Management, Greater Noida, India, 25–27 February 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 515–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ester, M.; Kriegel, H.P.; Sander, J.; Xu, X. A density-based algorithm for discovering clusters in large spatial databases with noise. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Portland, OR, USA, 2–4 August 1996; AAAI Press: Menlo Park, CA, USA, 1996; pp. 226–231. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, A.; Laio, A. Clustering by fast search and find of density peaks. Science 2014, 344, 1492–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, R.; Zhang, G.; Bie, R.; Dawood, H.; Ahmad, H. Clustering by fast search and find of density peaks via heat diffusion. Neurocomputing 2016, 208, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Ding, S.; Du, M.; Xue, Y. DPCG: An efficient density peaks clustering algorithm based on grid. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybern. 2018, 9, 743–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, X.; Quek, C. VDPC: Variational density peak clustering algorithm. Inf. Sci. 2023, 621, 627–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Du, W.; Xu, X.; Shi, T.; Wang, Y.; Li, C. An improved density peaks clustering algorithm based on natural neighbor with a merging strategy. Inf. Sci. 2023, 624, 252–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Westerholt, R.; Fan, H.; Zipf, A. Assessing spatiotemporal predictability of LBSN: A case study of three Foursquare datasets. GeoInformatica 2018, 22, 541–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Approach Category | Key Focus | Limitations/Identified Gaps | How MCS-APF Addresses the Gap |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Fusion Methods [6,8,9,11,12] | Integrating multi-source data (e.g., photos, check-ins) to improve POI coverage and description. |

| Hybrid Sensing & WR-GA: Balances cost and quality by fusing limited high-quality participatory data with large-scale, low-cost opportunistic data. WR-GA ensures quality under a budget. |

| Clustering-Based Techniques [7,13,27,28,29,30,31,32] | Using spatial clustering algorithms (e.g., DBSCAN variants) to identify POIs from geographic data. |

| DBSCAN-H Clustering Algorithm: Employs Haversine distance for accurate geospatial clustering. The framework’s data collection ensures robust input. |

| MCS Frameworks [17,18,19,20,21] | Leveraging mobile users for scalable data collection via task assignments and incentives. |

| WR-GA Algorithm & Hybrid Sensing: Optimizes worker recruitment for data quality within a budget. Integrates both sensing paradigms to maximize coverage and quality. |

| Our Work: MCS-APF | An integrated framework for accurate, cost-effective, and scalable urban POI classification. | Target: To solve the trilemma of achieving High Data Quality, Low Cost, and High Clustering Accuracy simultaneously. | Holistic Solution: Integrates a hybrid sensing strategy, a quality-aware recruitment algorithm (WR-GA), and a spatially accurate clustering algorithm (DBSCAN-H). |

| Parametric | Value |

|---|---|

| Total number of workers N | [50, 100, 150, 200] |

| Total platform budget B | 100 |

| Worker capacity ε | 0–1 |

| Worker credibility R | 0–1 |

| Type of Checked-in Place | Data Volume |

|---|---|

| Catering | 60,650 |

| Medical Category | 5907 |

| Transport Hubs | 25,136 |

| Science and Education | 8420 |

| Shopping mall consumer | 17,215 |

| Office space category | 22,729 |

| Sports and Leisure | 22,362 |

| Others | 65,009 |

| Algorithms | CH | DBI |

|---|---|---|

| DBSCAN-H | 27,768,483.118 | 0.01099 |

| DBSCAN-E | 1,370,026.845 | 0.01941 |

| K-means | 10,099.244 | 0.75512 |

| HDBSCAN | 15,200,000.000 | 0.01500 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Feng, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Guo, D.; Yang, G. MCS Assisted Accurate Perception Framework for Urban POI Classification. Sensors 2025, 25, 7235. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237235

Feng X, Yang Y, Zhang X, Guo D, Yang G. MCS Assisted Accurate Perception Framework for Urban POI Classification. Sensors. 2025; 25(23):7235. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237235

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeng, Xiaorong, Yuchen Yang, Xudong Zhang, Dongsheng Guo, and Guisong Yang. 2025. "MCS Assisted Accurate Perception Framework for Urban POI Classification" Sensors 25, no. 23: 7235. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237235

APA StyleFeng, X., Yang, Y., Zhang, X., Guo, D., & Yang, G. (2025). MCS Assisted Accurate Perception Framework for Urban POI Classification. Sensors, 25(23), 7235. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237235