2.2. Equations Governing the Flight Dynamics

To formulate the flight dynamics model, three reference frames are introduced for projecting forces and moments: the North–East–Down (NED) frame and the body-fixed frame.

The NED frame, denoted by the subscript e, is an Earth-fixed coordinate system in which the axis points toward geographic north, the axis is perpendicular to the Earth’s surface and directed downward (nadir), and the axis completes a right-handed, clockwise triad.

The body-fixed frame, denoted by the subscript b, is attached to the vehicle itself. The axis points forward along the longitudinal symmetry plane, is perpendicular to and directed downward within the same plane, and completes a right-handed coordinate system. The origin of this frame coincides with the vehicle’s center of gravity, and the entire triad is rigidly attached to the roll-decoupled control assembly.

The following section presents the governing equations of flight dynamics. Assuming the vehicle behaves as a rigid body, its motion is described by the classical Newton–Euler formulation. These six coupled differential equations describe both translational and rotational motion of the center of gravity as a function of the total external forces and moments acting on the body. The resultant aerodynamic, thrust, and gravitational contributions are expressed in Equations (

1) and (

2).

where:

is the lift force,

the drag force,

the thrust,

the Magnus force,

the pitch damping contribution,

the gravitational force, and

the Coriolis term.

Similarly, denotes the pitch damping moment, the overturning moment, the Magnus moment, and the spin damping moment.

The total external force vector and moment vector summarize all aerodynamic, gravitational, and inertial effects acting on the vehicle at each instant of flight. These terms are projected into the selected reference frame for integration within the full Newton–Euler dynamic model.

The external forces expressed in the Earth frame are nonlinear functions of the vehicle’s motion variables—such as aerodynamic velocity, total angle of attack, and Mach number—as well as of the aerodynamic coefficients and atmospheric properties. Due to the strong nonlinear coupling between these quantities, the explicit analytical formulation is omitted here; instead, their functional dependencies are presented. Additional mathematical details can be found in [

32].

The lift force in the Earth frame is defined in Equation (

3) as a nonlinear function of the angle of attack

, velocity vector

, and Mach number

M:

The drag force, shown in Equation (

4), depends primarily on

, Mach number, and air density:

The pitch damping contribution, given in Equation (

5), is influenced by angular momentum and moment of inertia:

The Magnus force, presented in Equation (

6), depends on spin rate and cross-coupling effects:

The thrust contribution is modeled in Equation (

7), as a function of the thrust direction vector

:

The gravitational force is represented by Equation (

8), which depends on the gravitational acceleration vector

and the vehicle mass

m:

Finally, Equation (

9) expresses the Coriolis contribution, which arises from the Earth’s angular velocity

and the relative motion of the vehicle:

Here,

and

denote the linear and cubic lift coefficients, respectively, while

represents the total angle of attack. The coefficients

and

correspond to the drag model (linear and quadratic terms). The vector

is the angular momentum expressed in the Earth frame, and

,

are the principal moments of inertia in the body frame.

is the pitch damping coefficient, and

the Magnus force coefficient. The vector

represents the vehicle pointing direction,

the gravity vector in the Earth frame,

the Earth’s rotation vector, and

the velocity of the vehicle in the same frame. Finally,

S denotes the reference aerodynamic surface and

the local air density.

Similarly, the aerodynamic and inertial moments acting on the vehicle in the Earth frame are given by the following expressions. These include the contributions of overturning, pitch damping, Magnus, and spin damping effects, all of which depend nonlinearly on the vehicle’s dynamic state, aerodynamic parameters, and flow conditions.

The pitch damping moment, defined in Equation (

10), depends on the vehicle’s angular motion and the coefficient

:

The overturning moment is described in Equation (

11), where

and

represent the linear and cubic coefficients:

The Magnus moment, expressed in Equation (

12), accounts for rotational flow coupling:

The spin damping moment, shown in Equation (

13), represents the stabilizing torque due to roll damping:

Here,

denotes the pitch damping moment coefficient, while

and

are the linear and cubic overturning moment coefficients, respectively. The coefficient

corresponds to the Magnus moment contribution, and

represents the spin damping moment coefficient. The variables

and

describe the position and velocity vectors in the Earth frame,

is the angular momentum,

M the Mach number,

the air density, and

S the vehicle’s reference surface. The principal moments of inertia

and

are included to account for the coupling between translational and rotational dynamics in the roll-decoupled configuration.

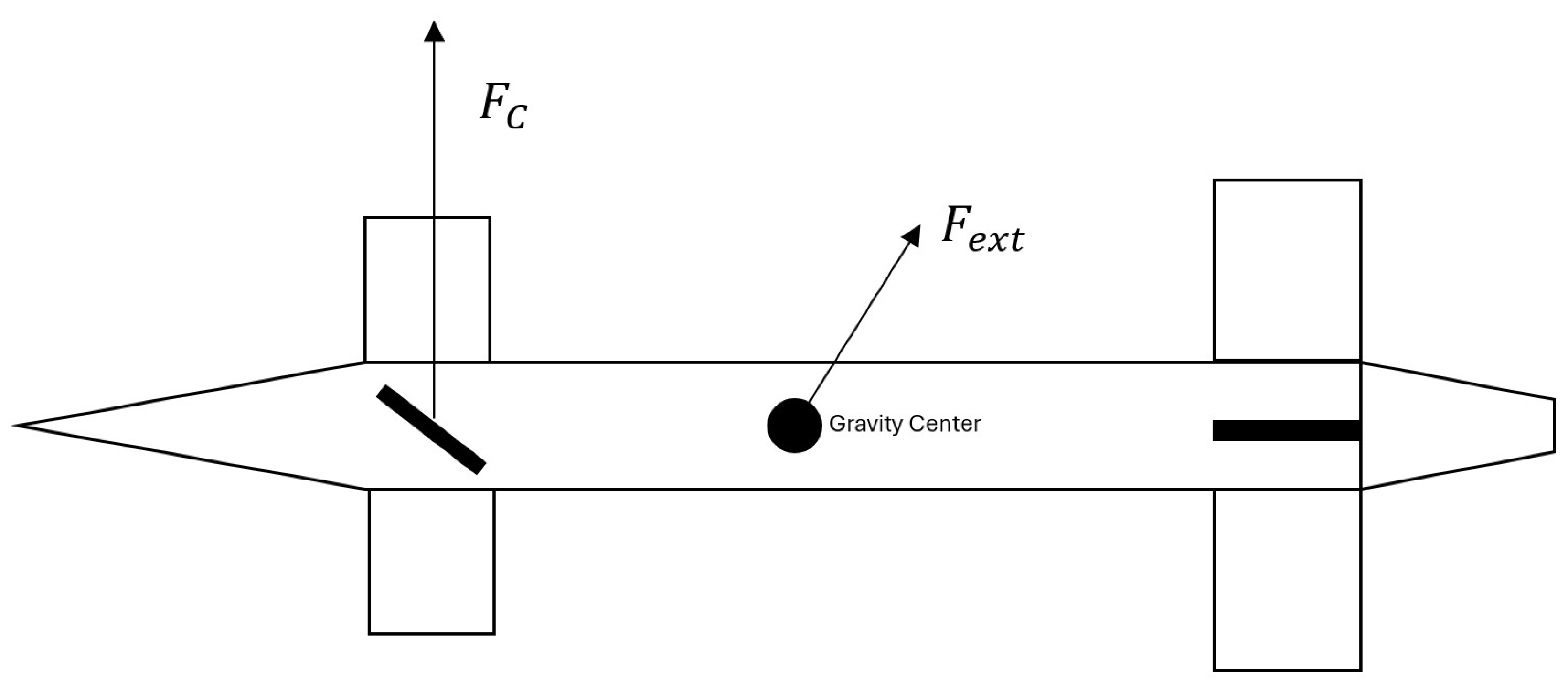

The control forces and moments, generated by the maneuvering system composed of four independently actuated canards, are expressed in Equations (

14) and (

15). These nonlinear relations depend on the aerodynamic flow, canard deflection, and local orientation of each surface.

Here,

is the forward-pointing unit vector lying in the vehicle’s plane of symmetry, while

denotes the deflection angle of the

i-th canard. The vector

represents the surface normal to the corresponding canard aerodynamic plane. The term

is the aerodynamic coefficient associated with the normal force on each fin,

S is the vehicle reference area, and

denotes the characteristic surface area of each canard element. The total control force

and moment

are obtained by summing the individual contributions of the four actuators.

As previously stated, a Newton–Euler formulation is adopted to describe the equations of motion of the vehicle. The dynamics are expressed in both the body-fixed frame (denoted as

b) and the flat-Earth frame (denoted as

e). These frames are related through the Euler angles of yaw (

), pitch (

), and roll (

), which define the vehicle’s orientation in space. The complete formulation is presented in Equations (

16) and (

17).

The translational motion of the center of mass, expressed in the body-fixed reference frame, follows Newton’s second law as shown in Equation (

16):

where

represents the linear velocity of the vehicle in body axes,

is the angular velocity vector, and

m is the total mass of the system. The term

accounts for the Coriolis effects arising from the rotation of the body frame.

Similarly, the rotational motion of the vehicle is governed by Euler’s equation, shown in Equation (

17):

where

is the angular momentum vector expressed in body axes, defined as

, with

being the inertia tensor referred to the body frame. The cross product

represents the gyroscopic coupling between roll, pitch, and yaw dynamics.

Equations (

16) and (

17) together constitute the six-degree-of-freedom (6-DoF) Newton–Euler equations of motion. To ensure consistency, all control forces and moments (

,

) as well as external forces and moments (

,

) must be expressed in the body-fixed coordinate system prior to their inclusion in these dynamic equations.

2.3. Attitude Determination Equations

The vehicle’s attitude can be geometrically characterized by identifying two non-collinear direction vectors, denoted here as and , expressed in two distinct reference frames—for example, the conventional Earth-fixed North–East–Down (NED) frame and the body-fixed coordinate system.

These two direction vectors,

and

, span a unique plane in three-dimensional space. The orientation of this plane is determined by its associated normal vector,

, which is computed as the vector cross product of

and

, as defined in Equation (

18).

The transformation between the Earth reference frame and the body-fixed coordinate system can be expressed through a rotation tensor, denoted as

. For convenience and numerical stability, each direction vector

(

) is normalized according to

. The rotation tensor can then be assembled following Equation (

19), where the normalized direction vectors

are arranged as column components.

This approach is fundamental in determining the spatial orientation of flight vehicles, as it allows the precise mapping between the Earth and body axes. By employing a rotation tensor, onboard sensors can be correctly aligned with the vehicle’s reference frame, thereby ensuring accurate measurement interpretation. Such information is essential for the guidance, navigation, and control (GNC) system, allowing the onboard computer to continuously correct deviations and maintain the desired trajectory. Overall, this method provides a reliable and computationally efficient framework for attitude estimation in aerospace systems.

The use of multiple vectors instead of only three provides redundancy and significantly increases the robustness of the attitude estimation. The number of sensors employed in this study to provide the sources for those vectors, was selected based on a trade-off between computational cost and accuracy. Increasing the number of sorces improves the geometric conditioning of the rotation matrix but also increases the system complexity.

Consequently, Equation (

19) can be generalized to accommodate an arbitrary number of direction vectors, as expressed in Equation (

20).

The next subsections outline two complementary methods for deriving the required vector pairs.

2.3.1. Velocity, Line of Sight and Gravity Vector Method

As mentioned earlier, determining the vehicle’s attitude requires identifying at least two distinct vectors expressed in two different reference frames. In this work, the velocity vector and the line-of-sight (LOS) vector are used as the reference pair.

If a GNSS sensor suite is installed on the vehicle, the velocity vector can be directly obtained from GNSS measurements expressed in the Earth-fixed frame (denoted by subscript

e). The velocity components in this frame, namely

,

, and

, define the velocity vector as shown in Equation (

21).

In parallel, the same velocity vector can also be computed in the body-fixed frame from a triad of accelerometers, one mounted along each principal axis. By integrating their measured accelerations over time, the velocity vector in the body frame is obtained as expressed in Equation (

22). In this equation,

,

, and

denote the acceleration components measured along the body axes, and

represents the estimated angular velocity vector, also expressed in body coordinates. It should be noted that, at this stage,

remains unknown; the algorithm used to estimate it will be presented in the following sections.

Similarly, the line-of-sight (LOS) vector must be determined in both the Earth-fixed and body-fixed reference frames, denoted as and , respectively. The vector can be readily obtained from GNSS sensor data, as it directly provides the vehicle and target positions in Earth coordinates. However, determining requires the use of the semi-active laser (SAL) seeker, which becomes operational only when the vehicle is sufficiently close to the target. Consequently, during the initial and mid-course flight phases, when the SAL signal is unavailable, an additional reference vector is required to enable continuous and reliable attitude estimation.

The gravity vector constitutes a natural candidate for this purpose. Determining the gravity vector in the Earth-fixed reference frame is straightforward, as it is always aligned with the

axis. Its expression is given in Equation (

23), where

g denotes the gravitational acceleration, assumed constant in this model with a value of

. It should be noted that higher accuracy can be achieved using more refined gravity models, in which

g varies with latitude, longitude, and altitude.

However, the gravity vector expressed in the body-fixed reference frame, , is also required. Although several methods exist to estimate , most are either complex or require additional sensors. For example, one approach involves identifying the constant component of the measured acceleration using a low-pass filter. In this method, the jerk in the body frame is computed as the time derivative of the acceleration; integration of this term yields the non-constant component of the motion, which is then subtracted from the measured acceleration to isolate the gravity component. Nonetheless, this technique becomes invalid when the vehicle undergoes rotational motion.

Another classical method to estimate

relies on the integration of the inertial mechanization equations [

35]. However, such an approach requires gyroscopes to provide angular rate information, contradicting the low-cost, gyro-free philosophy of the proposed system.

Therefore, the cornerstone of the present attitude estimation framework lies in accurately determining the gravity vector in the body-fixed frame using only accelerometer data. The Neural Networw methodology section introduces an estimation method that remains valid for both rotating and non-rotating vehicles while relying exclusively on accelerometers.

2.3.2. Array of GNSS Sensors Methodology

In the context of a vehicle equipped with an array of Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) antennas, the pair of vectors required for attitude determination can be directly obtained from the spatial distribution of GNSS sensors. A minimum of antennas (and up to in the tests conducted in this research) are required to reconstruct the rigid-body attitude.

The eight GNSS antennas are installed along the vehicle body as follows: the reference antenna is located at the center of mass, coinciding with the origin of the body-fixed frame. Two lateral antennas are mounted symmetrically at coordinates [0, 0.1, 0] m and [0, −0.1, 0] m in body axes. Two additional antennas are positioned along the longitudinal direction—one near the nose at [1, 0, 0] m and another near the tail at [−1, 0, 0] m. Finally, three antennas are mounted near the fin roots at [−0.8, 0.1, 0.1] m, [−0.8, −0.1, 0.1] m, and [−0.8, 0, −0.1] m. This geometric configuration provides full spatial coverage for accurate reconstruction of the orientation, while minimizing aerodynamic interference and preserving symmetry about the longitudinal axis.

Each antenna continuously transmits its GNSS position to the onboard computer. Taking one of them (denoted

) as the reference, the vectors connecting it to the remaining antennas are computed as

for

. After normalization, the following set of unit vectors is obtained in both coordinate frames:

2.4. Sensor Models

As outlined in the introduction, the main goal of this research is to streamline onboard navigation architectures by minimizing the reliance on complex and costly instrumentation. In conventional guidance and navigation systems, gyroscopes are typically used to measure angular velocity and orientation. Although these sensors provide accurate short-term attitude information, their performance tends to deteriorate in highly dynamic flight conditions, while maintaining precision under such regimes significantly increases system cost and complexity. To address this limitation, the proposed approach seeks to eliminate the dependency on gyroscopes by leveraging the fusion of Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) measurements, accelerometer data, and photodetector-based line-of-sight information. By integrating these complementary sources, the navigation solution enhances overall accuracy and robustness without the need for high-grade inertial sensors. This section presents the mathematical models used to characterize the behavior of each sensor and their role within the data fusion framework.

2.4.1. GNSS Sensor Modeling

Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) receivers determine position and attitude by measuring the carrier phase offset, denoted as , expressed in units of the carrier wavelength . Under ideal conditions, this observable allows for sub-centimeter accuracy, theoretically reaching approximately 0.003 m. However, such precision requires resolving the integer phase ambiguity N, representing the total number of complete wavelength cycles between a satellite and a receiver antenna. This ambiguity resolution remains one of the key challenges in high-accuracy GNSS-based navigation.

Several sources of error contribute to measurement uncertainty, including the satellite clock bias

, the receiver clock bias

, propagation delays caused by the ionosphere and troposphere,

, and local effects such as thermal noise and multipath interference

. Combining these elements, the pseudo-range observable,

—which represents the apparent distance between satellite

and receiver

—can be expressed as:

where

and

denote the signal reception and transmission times, respectively, and

c is the speed of light. Equation (

24) combines deterministic components (geometric range, clock biases) and stochastic components (multipath, atmospheric delays).

In attitude determination applications, not all error terms can be explicitly estimated.

Nevertheless, since several error sources are common to all receivers, differencing techniques can be applied to mitigate or eliminate their impact. For each satellite

, a line-of-sight (LOS) unit vector from receiver

to the satellite is defined as

. Given that the baseline between receivers is negligible compared to the satellite range, the LOS direction can be considered identical for all receivers and is denoted as

. Consequently, the relative geometry between receivers

and

observing the same satellite can be expressed as

The difference between two pseudo-range measurements from distinct receivers tracking the same satellite, known as the

single difference, is given by (

26):

The differencing operation removes common-mode errors, such as satellite clock bias and atmospheric propagation delay, which are approximately identical across closely spaced receivers.

To further suppress receiver-dependent biases, a

double difference is formed by subtracting the single difference of one satellite,

, from that of another,

. This yields the double-differenced observable

, defined by (

27):

The receiver clock bias term cancels completely in Equation (

27), which significantly improves robustness in the carrier-phase solution. However, multipath-related components,

, cannot be eliminated through differencing since they vary with antenna position and local scattering environment.

As noted by [

29], multipath effects are not well modeled by white noise due to their temporal and spatial correlation. Although multipath has a substantial influence on ground or low-altitude navigation—particularly in environments with reflective surfaces such as airports—its contribution diminishes considerably during cruise flight, where the primary source of reflection is the missile body itself [

36]. This assumption has been adopted in the present work.

Alternative approaches for compensating correlated GNSS errors include the use of deep learning architectures, such as recurrent or long short-term memory (LSTM) networks [

29,

37]. Nevertheless, given that the present study focuses on mid- and high-altitude flight, the simplified differencing model presented in Equation (

27) provides a suitable trade-off between computational efficiency and estimation accuracy for the proposed navigation framework.

As detailed previously, GNSS sensors can provide highly accurate measurements of carrier phase differences, expressed through double-differenced observations. Once the integer carrier ambiguity term,

, is determined—either by estimation or by correction through a trained neural network as introduced in subsequent sections—the double-difference of pseudo-ranges,

, can be computed directly from carrier-phase data, as shown in Equation (

27). Applying this to the previously defined geometric relationship in Equation (

25), the following expression is obtained:

where

is the baseline vector between sensors

and

, and

and

are the unit vectors pointing toward satellites

and

, respectively. This expression links the measured double-difference in carrier phase to the geometric configuration of the GNSS satellite constellation and the sensor array mounted on the vehicle.

Equation (

28) can be reformulated in matrix form to simultaneously account for all available satellites, as shown in Equation (

29). Here,

represents the Moore–Penrose pseudo-inverse of the geometry matrix

H, which allows estimation of the baseline vector in a least-squares sense:

where

is the column vector containing the set of double-differenced pseudo-range measurements with respect to a reference satellite

, as defined in Equation (

30), and

H is the geometry matrix composed of the relative satellite direction cosines, as expressed in Equation (

31):

The vectors

are obtained directly from the GNSS navigation data, representing the direction from the vehicle to each satellite in the Earth-fixed reference frame. Equation (

28) therefore defines an overdetermined system that can be optimally solved through Equation (

29) whenever

is invertible. If this condition is not met, an approximate solution for the baseline vector,

, can be obtained by minimizing the residual norm according to

The recovered baseline vectors among all sensor pairs define the spatial geometry of the GNSS array rigidly attached to the vehicle body. By comparing these vectors expressed in the Earth-fixed frame and in the body-fixed frame, the rotation matrix relating both reference systems can be reconstructed using the same formalism introduced in Equation (

29). This provides an independent and highly accurate estimation of the vehicle’s attitude without relying on gyroscopes or additional attitude sensors.

Consequently, the angular restitution approach represents a complementary and self-contained method for attitude determination, valid throughout all flight phases. When fused with accelerometer, GNSS, and semi-active laser (SAL) data, it contributes to a robust hybrid navigation system capable of maintaining accurate attitude and position estimates even under high-dynamic flight conditions.

2.4.2. Accelerometers

An accelerometer measures the specific force acting on the vehicle, that is, the instantaneous rate of change of velocity within the body-fixed reference frame. In this study, each accelerometer is modeled as an ideal sensor affected by a bias and additive white noise process, with a standard deviation of approximately

, which reflects the performance of typical high-grade navigation devices. The sensor model can therefore be represented as

where

denotes the measured acceleration vector in the body frame,

is the true specific acceleration of the vehicle,

represents the accelerometer bias (assumed to vary slowly with time), and

is a zero-mean Gaussian noise vector.

The estimated velocity in body axes is subsequently employed, together with other onboard measurements, to determine the vehicle’s inertial velocity and orientation through sensor fusion. It is important to note that, due to the integration process, even small bias or noise components in acceleration cause cumulative drift in the velocity estimate over time. Such errors must therefore be mitigated through complementary or Kalman-based filtering strategies.

Beyond their role in kinematic state propagation, accelerometer measurements are also used for gravity vector estimation. As detailed in subsequent sections, the magnitude of the measured acceleration is exploited to infer the direction of the local gravity vector once the translational motion component has been removed. Accurate knowledge of the vehicle’s velocity magnitude is essential for this purpose, as it enables separation of inertial and gravitational contributions within the measured acceleration signal.

2.4.3. Semi-Active Laser Kit

Laser-based guidance provides a reliable means of steering a vehicle toward a designated target using the reflection of a laser beam. In this approach, an external laser illuminates the target continuously, and part of the reflected radiation is scattered in multiple directions. When the vehicle enters the region where a portion of this scattered energy reaches its optical seeker, a semi-active laser (SAL) kit detects the direction of the incoming energy and generates control signals to adjust the vehicle trajectory toward the illuminated spot. This optical seeker, therefore, constitutes the primary element of the terminal guidance system.

The SAL kit employs a quadrant photo-detector composed of four independent photodiodes that convert incident light into electrical currents, denoted as

,

,

, and

. The relative distribution of these intensities defines the position of the laser spot centroid on the detector surface. Following the formulation in [

19], the normalized coordinates of the centroid on the sensor plane can be estimated as

The corresponding radial distance from the detector center,

, can then be determined as

Although these computed coordinates are conformally related to the actual centroid position, a correction is required to obtain the true radial displacement,

, on the detector plane. Experimental calibration data provide the nonlinear mapping

, as shown in

Table 3. A cubic spline interpolation is then applied to approximate this relationship as a continuous function.

Once the calibration function

is known, the corrected spot coordinates on the detector plane can be obtained using Equation (

36):

where

is the physical radius of the photo-detector. From these coordinates

, the direction of the line-of-sight (LOS) vector can be reconstructed in the body-fixed coordinate system, considering the geometric offset between the photo-detector and the vehicle’s center of mass.

It is important to note that the SAL seeker provides useful information only during the terminal phase of the flight—when the reflected laser energy is strong enough to be detected. Nevertheless, this phase is also the most critical, as small errors in relative positioning between target and vehicle (on the order of a few meters) can cause significant impact deviations. Consequently, integrating a high-precision terminal guidance device such as a semi-active laser seeker is strongly recommended for this stage of the mission.

The fusion of the SAL sensor data with measurements from GNSS and inertial accelerometers enables an accurate estimation of the line-of-sight vector and overall vehicle attitude. This multisensor hybridization ensures precise trajectory correction during terminal homing, enhancing both hit accuracy and robustness under real flight conditions.