1. Introduction

Non-Catching type Gauges (NCGs), including disdrometers, are increasingly used to measure the microphysical properties of rainfall. Optical transmission disdrometers detect the size and fall velocity of each individual raindrop in flight by measuring the obstruction to a generated light beam, therefore providing the drop size distribution (DSD) of the observed rain event. This non-contact measurement technique is also particularly promising for various applications where integral rainfall variables, such as rainfall intensity (RI), radar reflectivity (Z) and kinetic energy (KE), are obtained by processing the raw measurements.

In addition to instrumental bias, which can be quantified through accurate laboratory calibration [

1], disdrometers are susceptible to environmental sources of measurement bias. These are due to environmental conditions at the measurement site and include, for example, the impact of sunlight, lighting, wind, and atmospheric pollution. The present work focuses on the impact of wind, recognised as the primary environmental factor inducing bias in rainfall measurements [

2].

Indeed, the instrument body behaves like a bluff-body obstacle to the wind, generating strong velocity gradients and flow deformation near its sensing area (i.e., the laser beam in the case of optical transmission disdrometers). Such aerodynamic disturbance affects raindrop trajectories, which may be diverted from or towards the instrument’s sensing area depending on their size and fall velocity. This phenomenon is well documented in the literature for both catching gauges (CGs), which are traditionally used for measuring rainfall and snowfall, and NCGs, though less frequently quantified for disdrometers [

3].

One example is the work of Capozzi et al. [

4], in which the wind-induced bias in rainfall measurements taken by the Laser Precipitation Monitor (LPM) [

5]— an optical transmission disdrometer manufactured by Thies Clima, Adolf Thies GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen, Germany —was estimated in situ by comparing it with a collocated tipping-bucket rain gauge. Evidence of artefacts in the measured DSD was observed in data from a stationary Parsivel optical transmission disdrometer [

6] (manufactured by OTT Hydromet GmbH, Kempten, Germany) when compared with data from an identical instrument with an automatic variable orientation and tilting mount that was used to continuously align it with the wind direction [

7]. Similar discrepancies were noted in measurements from the Thies LPM, even at limited wind speed. Upton and Brawn [

8] installed two such instruments with two different orientations (rotated by 90°) and reported differences of up to 20% in the total number of detected raindrops.

Wind-induced biases were also reported for the Two-Dimensional Video Disdrometer (2DVD)—manufactured by Joanneum Research, Graz, Austria — by Greenberg [

9], who noted an underestimation of precipitation when part of the instrument’s sensing area received no precipitation under specific wind conditions. Further studies conducted by Testik and Pei [

10] on an improved version of the 2DVD showed that the effect of wind on precipitation is still present, affecting not only the measured amount and intensity, but also the DSD.

Methods to quantify the wind-induced bias in rainfall measurements include field comparisons against reference shielded gauges (see, e.g., [

11]), wind tunnel (WT) experiments (see, e.g., [

12] and the references therein) and numerical simulations (see, e.g., [

13]). The main obstacle to quantifying the wind-induced bias of NCGs is their complex, usually non-radially symmetric geometry. Their aerodynamic behaviour depends heavily on the wind direction, which significantly increases the time and effort needed to evaluate the bias using field campaigns and WT experiments.

Instead, numerical simulation allows many different configurations to be easily investigated in terms of wind speed and direction, instrument geometry, and precipitation type (see, for example [

4]), at an acceptable cost in terms of computational resources. Nešpor et al. [

14] were the first to use a numerical approach to investigate the wind-induced bias for NCGs, applying it to the study of the 2DVD. However, the outer shape of the instrument considered in that study is now obsolete and differs significantly from the current version.

In their recent work, Chinchella et al. [

3,

15] quantified the wind-induced bias numerically for two widely adopted NCGs: the WXT520 (manufactured by Vaisala, Helsinki, Finland) electroacoustic precipitation sensor [

16] and the Thies LPM. Various combinations of wind speed and direction were studied for both instruments, showing that liquid precipitation could be overestimated by up to 400% (WXT520) or not measured at all (Thies LPM). However, variability in instrument geometry and the measuring principles adopted makes it impossible to use a common adjustment function.

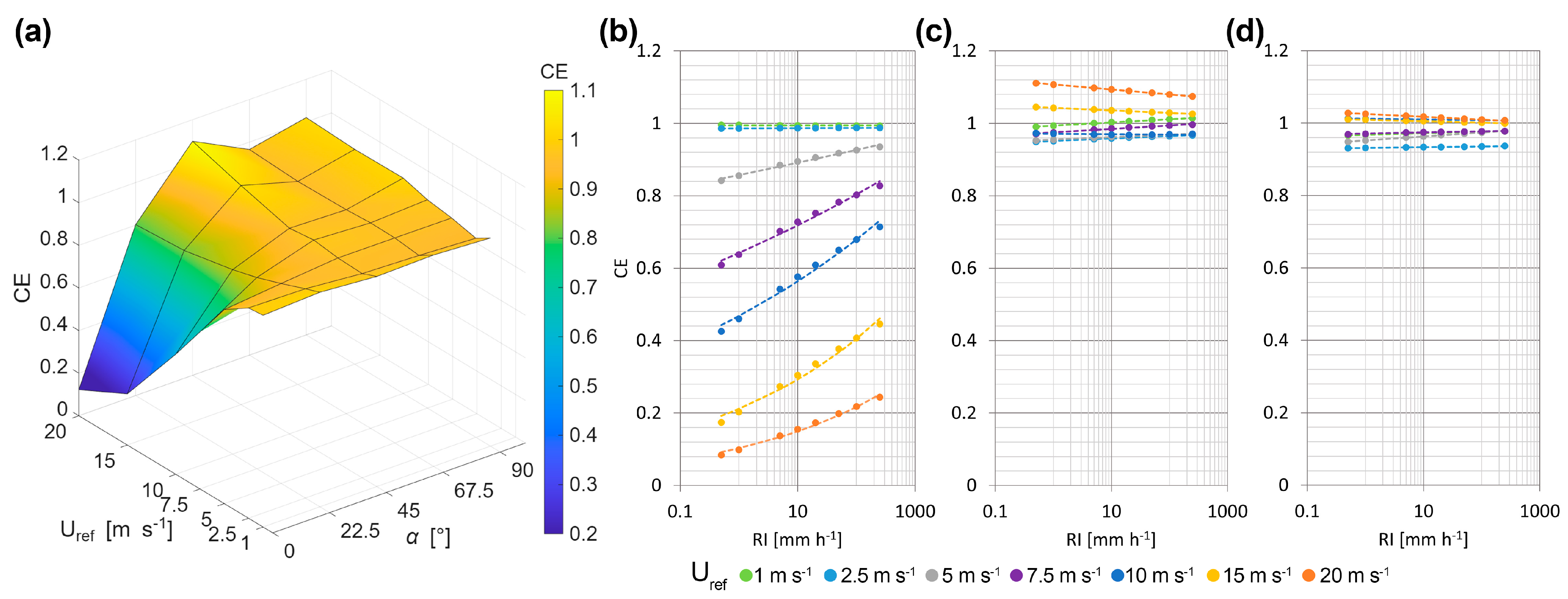

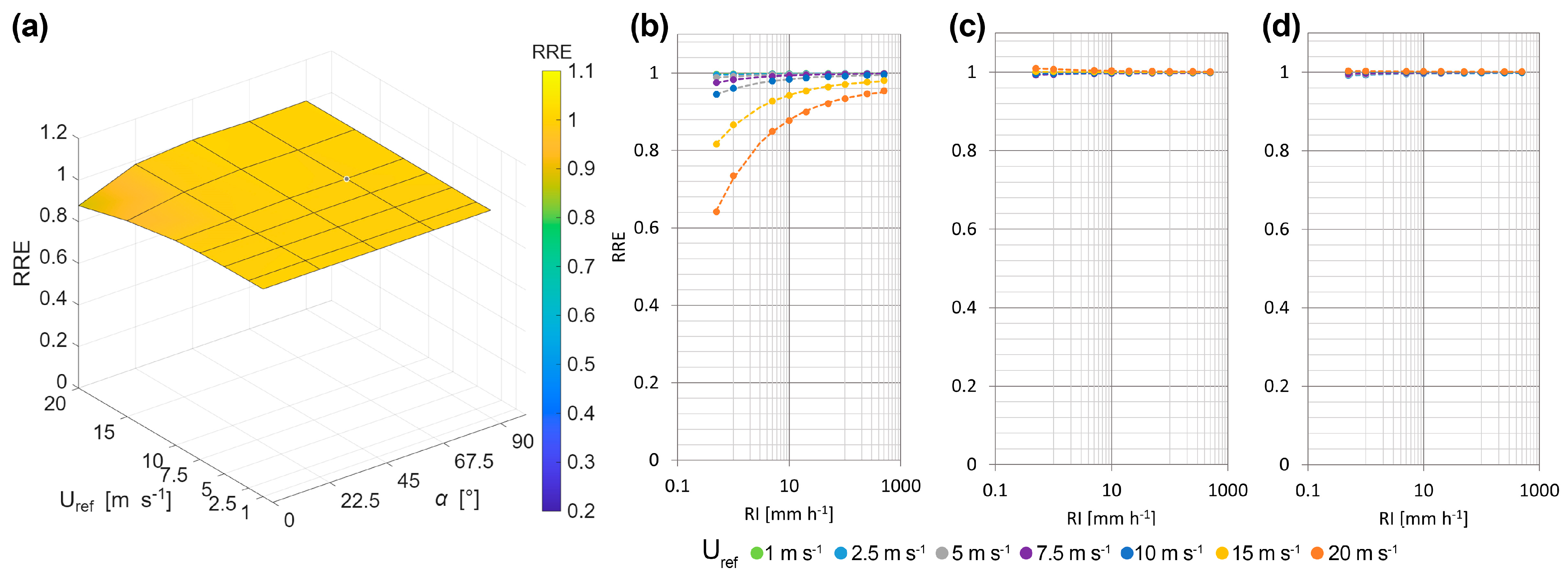

In this study, we use numerical simulations to quantify the wind-induced bias of rainfall measurements for the widely used OTT Parsivel2 optical transmission disdrometer and develop adjustment curves for use in practical applications. Catch ratios, which are a site-independent measure of instrument performance in windy conditions, are obtained as a function of raindrop size, wind speed, and direction. After assuming a sample DSD function and the relationship between its parameters and rainfall intensity, the wind-induced bias is quantified for relevant integral variables, such as RI and Z, and adjustment curves are provided.

The organisation of the paper is as follows:

Section 2 describes the simulation framework, numerical setup and assumptions, while

Section 3 reports the results in terms of the aerodynamic behaviour of the instrument and the impact on the fall trajectories of raindrops of different sizes.

Section 4 discusses and quantifies the resulting wind-induced bias by calculating the catch ratios and their dependence on raindrop and wind characteristics. The bias on integral variables derived from raw measurements is also quantified in

Section 4 and conclusions are drawn in

Section 5.

2. Methodology

A two-step procedure was employed to evaluate the wind-induced bias for the OTT Parsivel2 in case of rainfall measurements. First, the velocity field around the instrument was obtained from Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulations involving different wind speeds and directions. Second, the effect of the resulting aerodynamic disturbances on raindrops was evaluated using a Lagrangian Particle Tracking (LPT) model. The instrument’s performance in windy conditions was evaluated by analysing the computed raindrop trajectories and how they interacted with the instrument body and sensing area.

2.1. The OTT Parsivel2 Disdrometer

The Present Weather Sensor (PWS), manufactured by OTT HydroMet GmbH, Kempten, Germany and named Parsivel

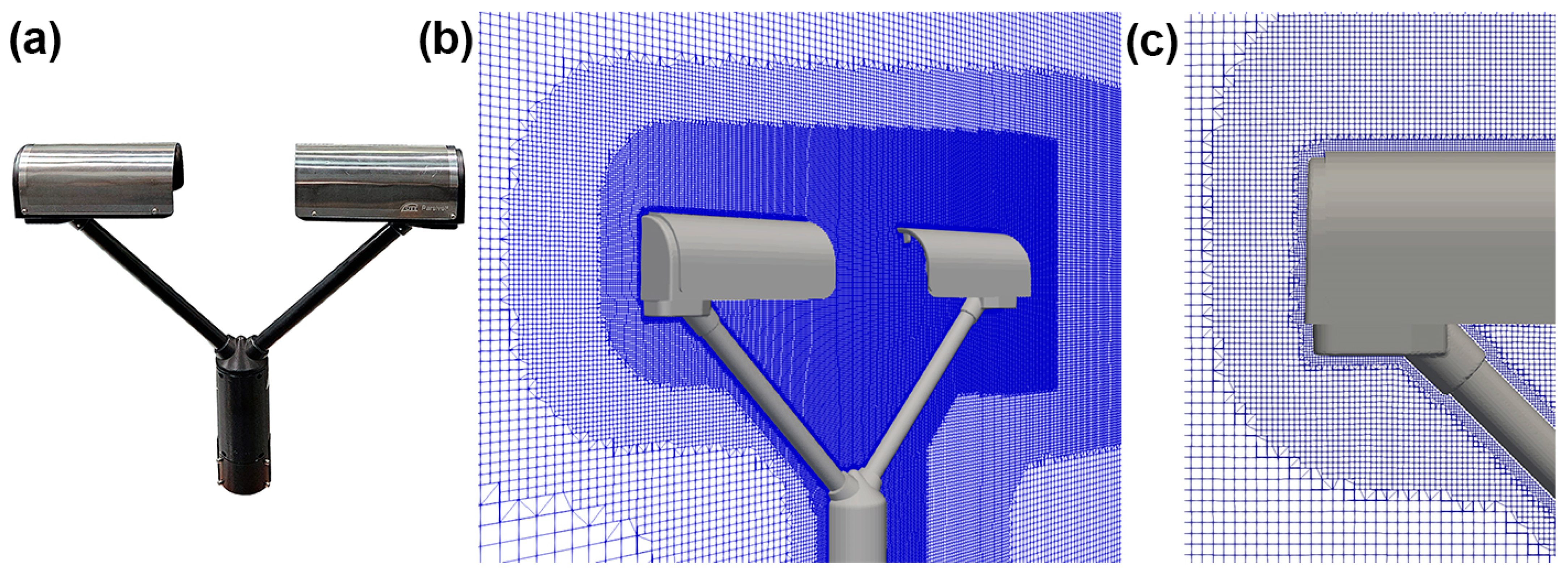

2 (an acronym for ‘Particle Size and Velocity’), is equipped with horizontally aligned laser emitter and receiver heads connected to the instrument’s main body by supporting arms (see

Figure 1a). A laser diode is used to produce a thin light beam that is 30 mm wide and approximately 180 mm long, considering the part of the beam that is exposed to undisturbed (vertical) precipitation. The power of the laser beam is converted into an electrical signal by a photodiode in the receiver head. This signal is reduced by any hydrometeor or other opaque object crossing the beam and casting a shadow on the receiver. The light blockage—and therefore the signal reduction—is proportional to the size of the falling hydrometeor.

The fall velocity is obtained from the duration of the beam blockage (extinction). The combination of hydrometeor size and fall velocity, together with the measurement of local temperature, also makes it possible to identify the type of precipitation (e.g., drizzle, rain, snow, soft hail, hail and mixed) and to exclude objects other than hydrometeors that may cross the laser beam, such as insects, since the size-velocity relationship would not be consistent with that expected for hydrometeors (e.g., provided by Gunn and Kinzer [

17]).

The instrument reports the diameter of raindrops in 32 classes, ranging from 0.2 to 8 mm (extended to 25 mm for solid hydrometeors). The fall velocity is also reported in 32 classes, spanning a range of 0.2 to 20 m s−1. The precipitation type is categorized in 8 classes, from drizzle to hail. The size and fall velocity distribution over the class binning, aggregated at 1 min resolution, is also used to calculate the intensity and amount of precipitation, visibility, the kinetic energy of precipitation and radar reflectivity.

The OTT Parsivel2 has a non-radially symmetric geometry that is significantly more complex than the cylindrical or semi-cylindrical shape of traditional catching-type rain gauges. Furthermore, the two heads containing the laser emitter and receiver are quite bulky and obstruct the wind significantly. This also implies that the wind-induced disturbance depends strongly on the wind direction.

The instrument’s operating manual acknowledges this fact and recommends aligning the laser beam perpendicular to the prevailing wind direction at the installation site. It also notes that glare and intense sunlight may impact the measurements. The same operating manual states that the accuracy of rainfall intensity measurements is ±5%, whereas this degrades to ±20% in the event of solid precipitation [

6].

2.2. Fluid Dynamics Simulation Setup

The simulations were based on the numerical model of the instrument geometry, which was provided by the manufacturer. The Unsteady Reynolds Averaged Navier–Stokes (URANS) equations around the instrument body were solved numerically using the open-source OpenFOAM C++ library [

18]. Simulations were run under the hypothesis of stationary turbulence characteristics until the steady state was reached. Assumptions about the physical properties of air are as follows: incompressible fluid, density of 1.2 kg m

−3 and kinematic viscosity equal to 1.5 × 10

−5 m

2 s

−1, with a free-stream turbulence intensity of 1%.

A structured mesh with variable refinement was used to discretise a simulation domain of 4 m (length) by 2.4 m (width) by 2 m (height) surrounding the instrument geometry, an example of which is shown in

Figure 1b. The wind direction is along the longitudinal axis (X), with an upward pointing vertical axis (Z) and a transversal axis (Y) that is perpendicular to both X and Z.

Five different meshes were created by rotating the instrument inside the domain to simulate various wind directions from α = 0° to α = 90°, in increments of 22.5°. Here, α is the angle between the wind direction and the instrument’s main symmetry axis. In the configuration at α = 0° the X axis is parallel to the main symmetry axis of the instrument, therefore the wind first impacts one of the two heads, whereas in the configuration at α = 90°, the wind impacts the side of the instrument perpendicular to the laser beam. The origin of the reference system is in the centre of the instrument’s sensing area (the laser beam). The mesh has a variable cells size with a maximum of 0.05 m and a minimum of 0.75 mm near the instrument (see

Figure 1c). This allows reproducing the fine details of the instrument body and correctly model the turbulence generated by flow interaction with solid surfaces.

Seven wind speed values (Uref) of 1, 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10, 15 and 20 m s−1 were simulated for each direction.

Preliminary simulations were run to assess the quality of the mesh resolution, using the calculated ratio (R

L) of the integral length scale of turbulence to the grid length scale. For URANS simulations, an R

L value of at least 5 is required to ensure that the larger eddies, which account for 80% of the turbulence kinetic energy, are discretised by at least 5 cells [

19]. We adopted the

k-

ω Shear Stress Transport (SST) model for turbulence, where

k is the turbulent kinetic energy and

ω the specific turbulent dissipation rate, therefore the integral length scale (L

0) is obtained from Equation (1), while R

L is obtained from Equation (2).

where the coefficient

is equal to 0.09 and

Vc is the volume of the cell.

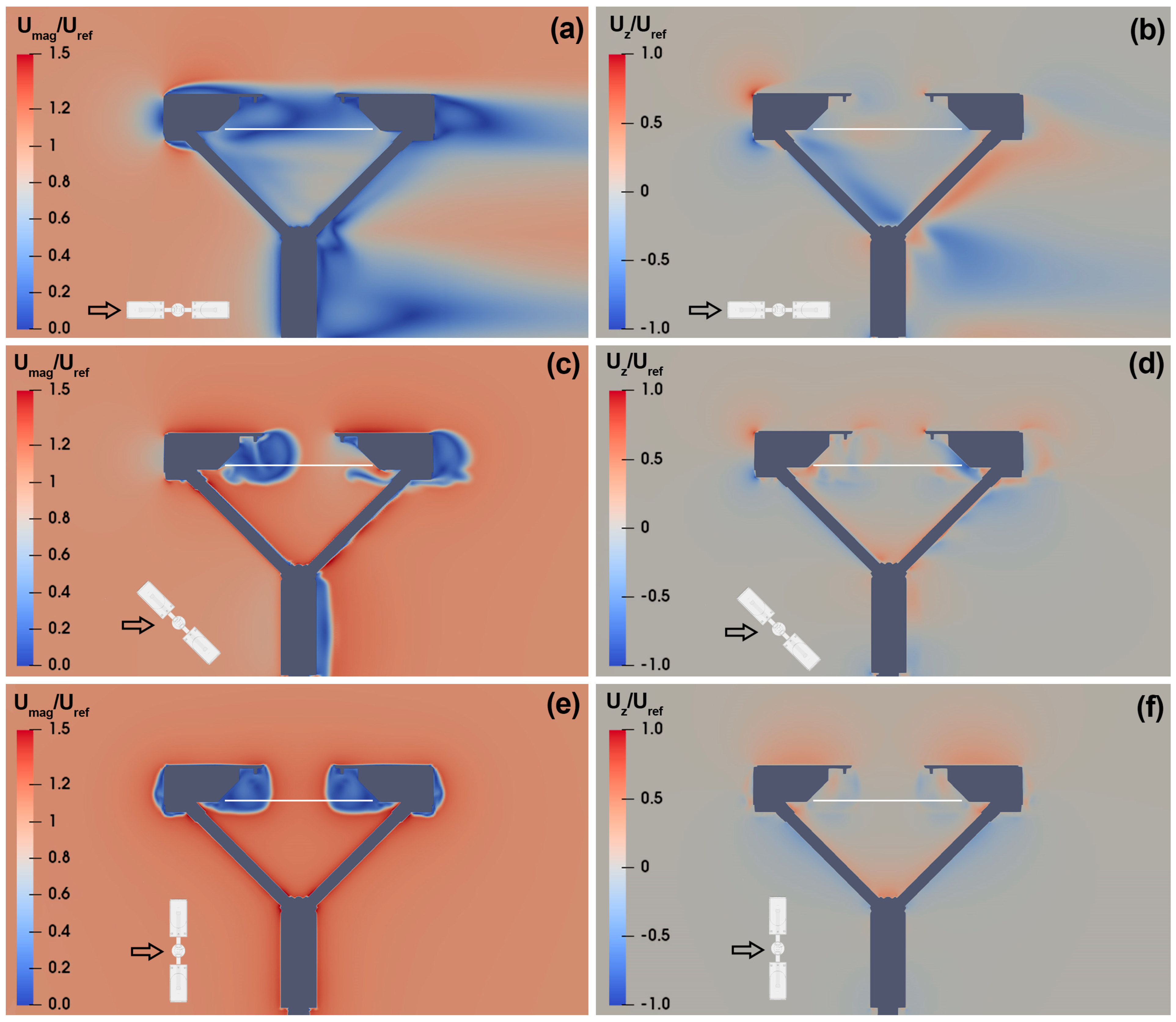

Figure 2a shows the map of R

L values obtained, indicating that the optimality criterion (R

L ≥ 5) is met across most of the domain, except in the vicinity of the instrument’s stagnation point (top left) and in the wake of the supporting arms.

The average value of the dimensionless wall distance (y+) obtained from preliminary simulations indicates, according to wind velocity, whether the mesh cells closest to the instrument surface are positioned in the buffer or the log-law layer. The near wall boundary conditions for k, ω and the turbulent viscosity (ν

t) [

20] were set at all solid surfaces using wall functions, independent of y+.

The non-orthogonality, skewness and aspect ratio (see, e.g., [

21,

22]) of the final meshes, containing between 6 and 8 million cells depending on wind direction, are listed in

Table 1. The numerical simulation setup was validated in previous work for various geometries (see, e.g., [

15]) using wind tunnel experiments. Due to the large meshes required the computational cost of these simulations was about 30,000 core hours.

2.3. Lagrangian Particle Tracking

Since the volume fraction of raindrops in the atmosphere is generally low, even at high rainfall rates [

23], their presence does not affect the airflow around the instrument body. Furthermore, particle-to-particle interactions are very limited close to the ground, where the instruments are positioned. We therefore adopted an uncoupled LPT model, which is computationally inexpensive yet capable of modelling the interaction between the instrument, wind and precipitation.

In the uncoupled model, trajectories are obtained by solving the equation of motion (see, e.g., [

12]), based on a stationary airflow velocity field (i.e., the steady-state solution), and by neglecting particle-to-particle interactions. Assuming a steady state condition for the wind field is also reasonable given typical field conditions. This is because the typical time interval required for a drop to cross the computational domain is between 0.1 and 1 s.

Raindrops are released into the computational domain from a regular grid with a width of 0.15 m and a length of at least 0.45 m, with a regular spacing of 2 mm. In undisturbed conditions, the drop released from the centre of the grid would reach the centre of the instrument laser beam. The grid length is increased for high wind speeds and small raindrop diameters. Depending on the specific combination of drop diameter, wind speed and direction between 60,000 and 400,000 particles were therefore released in the domain. Of these, only about 2.25% to 0.33% are expected to reach the instrument’s sensing area in undisturbed airflow conditions. This ensures that all trajectories that could potentially reach the instrument sensing area are included in the simulation.

Figure 2b shows an example of the release grid for a wind speed of 10 m s

−1 and various drop diameters.

A virtual surface, transparent to the wind but not to trajectories, was also included to model and visualise the instrument laser beam. Drops were then tracked until they impact on the instrument body, the instrument sensing area or exit from the domain boundaries. The simulations were then stopped once all released drops impacted one of the domain boundaries or travelled significantly below the instrument sensing area. In total 11 drop diameters were simulated, equal to 0.25, 0.5, 0.75 and from 1 mm up to 8 mm (with 1 mm increments).

An in-depth analysis on the use of a LPT model for simulating drop trajectories and an extensive wind tunnel validation is presented in the work of Cauteruccio et al. [

12]. The drag coefficient formulation used in that work is implemented here for various ranges of the particle Reynolds number, as established a priori among those proposed in the literature by Folland [

24] and formulated starting from data published by Beard [

25] and Khvorostyanov and Curry [

26]. Since an uncoupled approach was used, the computational cost for running the LPT model was about 500 core hours.

5. Conclusions

The wind-induced bias in rainfall measurements taken with the OTT Parsivel2 disdrometer is significant and varies greatly depending on the wind speed and direction. Numerical simulations show that the wind significantly impacts raindrop trajectories when it is parallel to the instrument’s laser beam. Conversely, a limited—or, in some cases, negligible—impact is observed when the wind is perpendicular to the instrument. The OTT Parsivel2 also shows significant overestimation of the number of raindrops, which, depending on the wind direction, may decrease with increasing wind speed (α = 0°) or increase in stronger winds (α = 45°).

This behaviour is explained by the complex shape of the instrument’s emitter and receiver heads, which have large lateral protection shields. While this configuration may be effective in shielding the instrument from glare due to the sun or avoiding splashing on the optical components in the absence of wind, the shape of the heads is not optimised for windy conditions. In the case of drops falling at a strong inclination, their trajectories may hit the upstream head without even reaching the instrument’s sensing area, despite not being significantly diverted by the aerodynamic disturbance. In other cases, for α between 22.5° and 67.5°, trajectories may bypass the shield instead and cross the laser beam at positions that would not be reached by vertically falling drops. However, as the instrument’s measuring principle depends only on the blockage produced by the drop and not its longitudinal position along the laser beam, it is assumed that these drops can be sensed correctly by the instrument.

The impact of wind cannot be overlooked, and disdrometer measurements should be accompanied by additional measurements of wind speed and direction. In any case, measurements from the OTT Parsivel2 should be treated with caution and adjusted for wind-induced bias at any site where wind is a common occurrence during rainfall. The CR functions derived in this study can be used to quantify the measurement bias of the DSD and of any integral rainfall variable derived from it. Adjustment of integral variables can be achieved by considering the local DSD and its relationship with rainfall intensity.

Proper installation of the instrument with the laser beam perpendicular to the prevailing wind direction, as well as choosing an installation site that is protected from the wind, may help to mitigate wind-induced bias. Further mitigation of this bias would require considerable modifications to the instrument design or the use of windshields. However, adjustment of the measured data according to the correction function proposed in this work would not be possible in these latter cases, since the aerodynamic disturbance would change drastically.

Note that the measurement accuracy investigated in the present work only refers to the wind-induced bias, while instrumental biases should be considered as well before using the derived data in any research or practical application. Further research is needed to quantify the instrumental bias of disdrometers, which would add to the accuracy assessment for this instrument. At present, only the accuracy declared by the manufacturer is available, in the absence of any agreed and/or standardised methodology for the laboratory calibration of disdrometers.

In the present work a low value of the free-stream turbulence intensity was set (equal to 1%) as representative of a well-designed measurement site. This choice allows us to focus on the effect of the aerodynamic response of the instrument, limiting the overlap of multiple effects induced by the free-stream turbulence and the turbulent structures that develop around the gauge geometry. Nevertheless, in the field the free-stream turbulence intensity can assume higher values due to the specific characteristics of the installation site. For example, direct measurements taken at a field test site in Nafferton, UK, using a 3D sonic anemometer to measure high-frequency wind, allowed the turbulence intensity at a rain gauge collector height to be quantified as between 0.1 and 0.4 at wind speeds below 6 m/s [

32]. For the authors knowledge the role of free-stream turbulence was investigated in the literature for catching gauges only. Therefore, starting from the results of the present paper, the role of free-stream turbulence on disdrometer measurements will be investigated in the future.

In addition, future research will involve validating the numerical results obtained in this study by comparing the adjusted field measurements obtained using the OTT Parsivel2 disdrometer with the measurements obtained using a suitable reference instrument under the influence of natural wind. The choice of the reference instrument will be critical to this exercise, since it will be important to compare not only integral quantities (such as rainfall depth or intensity), but also microphysical features such as drop size and velocity distribution.