Multi-Step Apparent Temperature Prediction in Broiler Houses Using a Hybrid SE-TCN–Transformer Model with Kalman Filtering

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

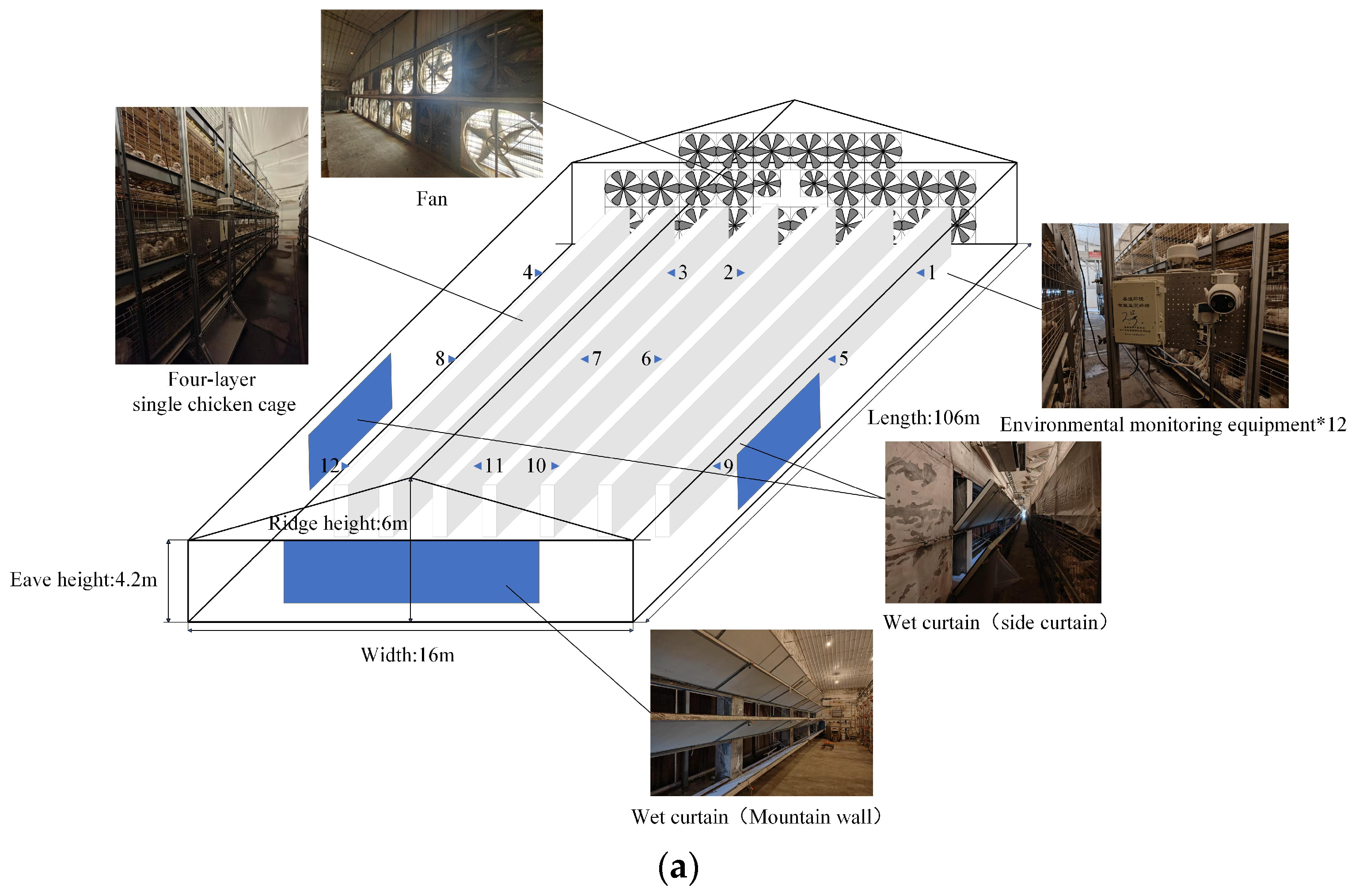

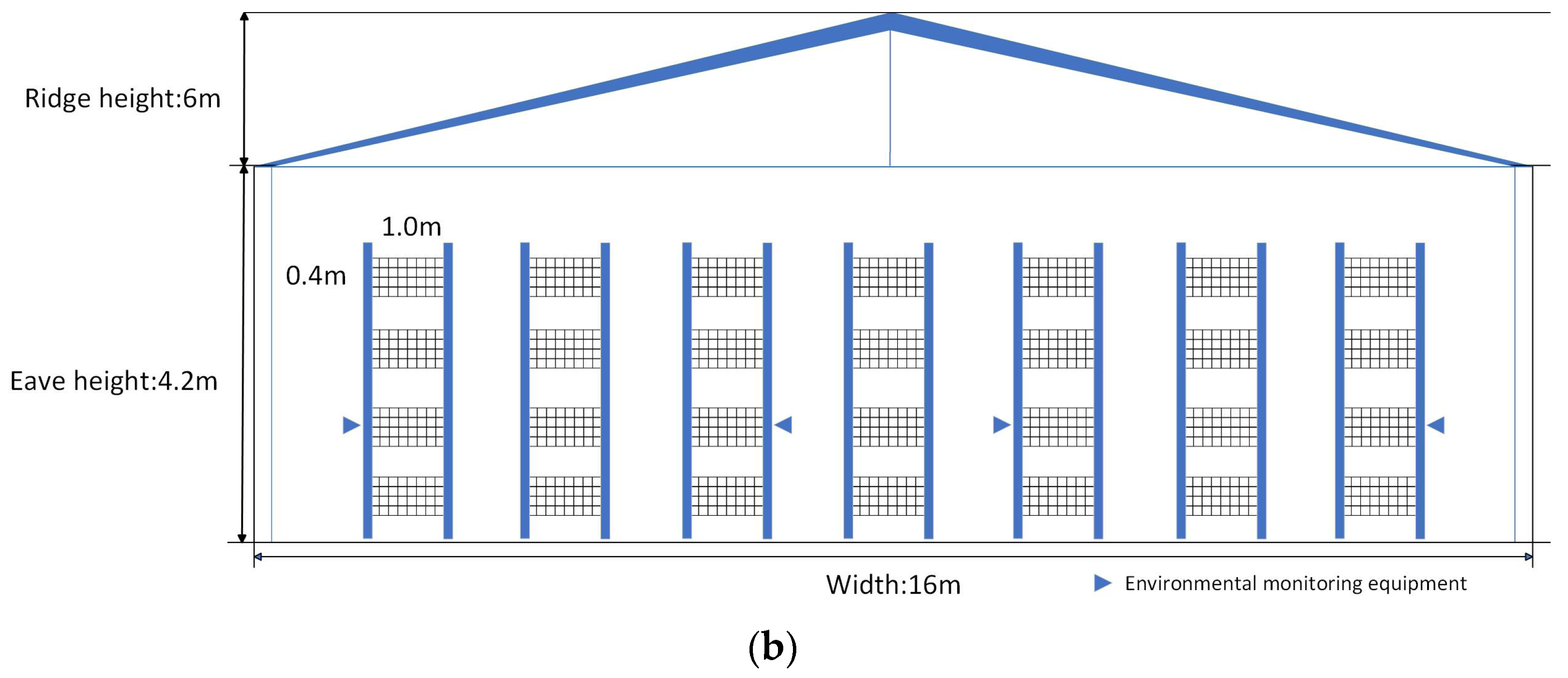

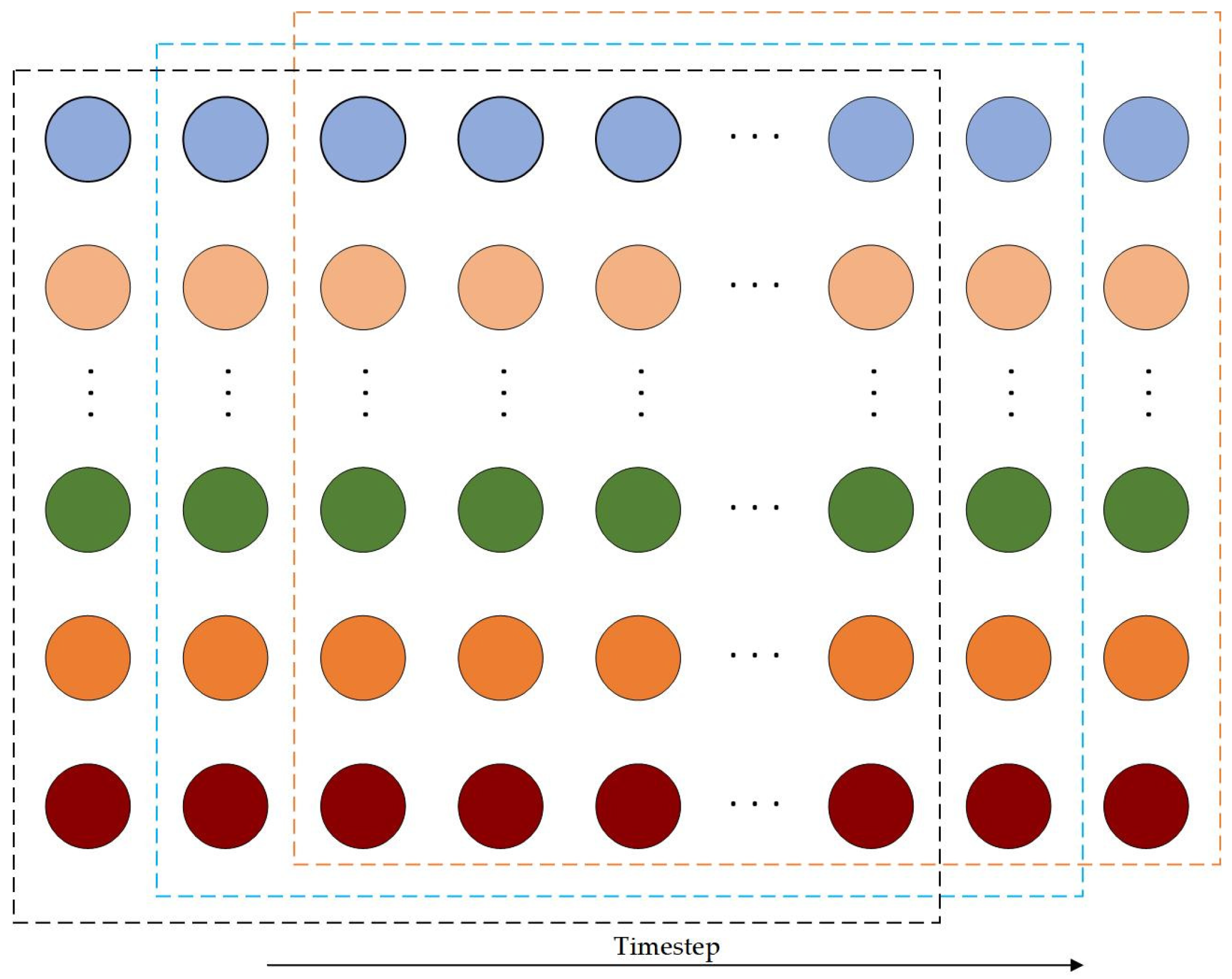

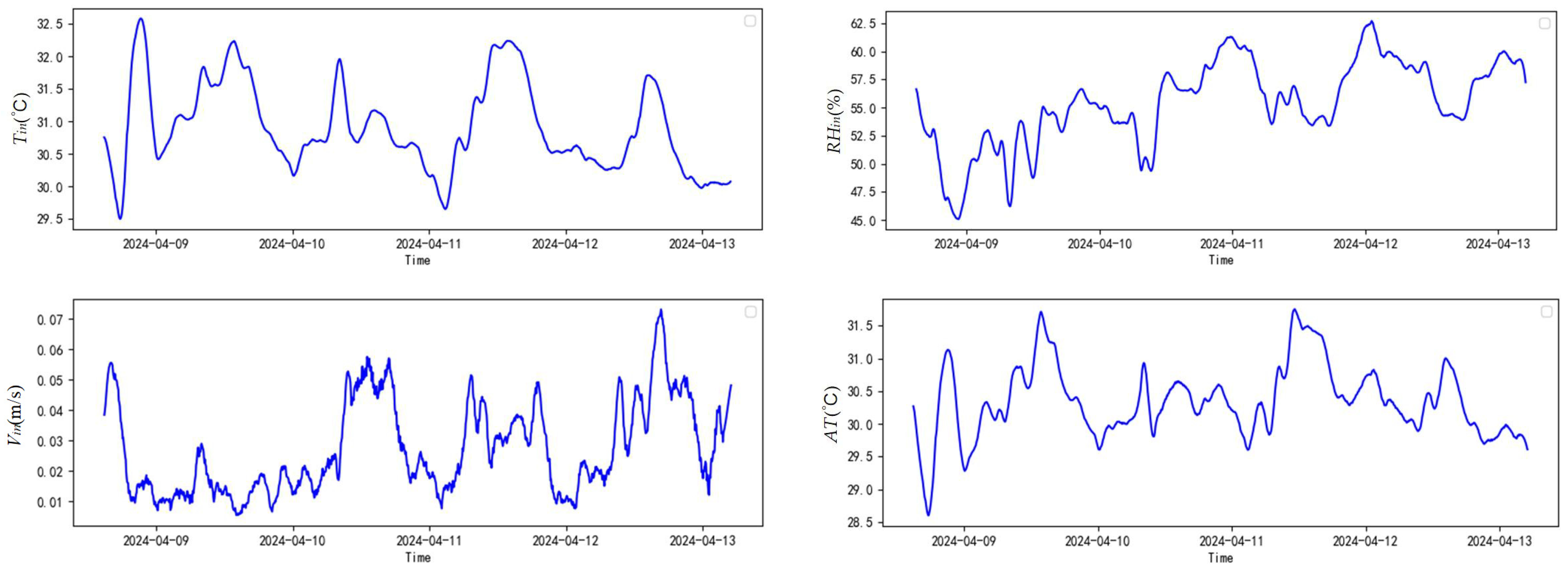

2.1. Data Collection and Preprocessing

- i.

- Data from all 12 indoor monitoring devices were aggregated by calculating their arithmetic mean. This provided a representative overall value for the entire facility, used to analyze real-time conditions and cyclic variations.

- ii.

- To maintain data continuity and accuracy, missing and abnormal values were imputed based on the local linear trend within the dataset, avoiding erroneous interpolation over extended time periods.

- iii.

- In order to evaluate the thermal environment of the henhouse, the apparent temperature (AT) was calculated based on the processed data. The apparent temperature formula is shown in Equation (1).where T is the indoor temperature (°C), V is the indoor wind speed (m/s), RH is the indoor relative humidity (%), RHtarget is the target humidity (%), Kv is the wind chill coefficient, and Kh is the wet-heat coefficient. Age-dependent coefficients are used in the apparent temperature (AT) formula to account for the varying thermal sensitivity of broilers at different growth stages. Younger chicks are more susceptible to heat or cold stress due to their underdeveloped thermoregulatory systems, while older birds have greater tolerance to environmental fluctuations. By adjusting the wind chill coefficient (Kv) and wet-heat coefficient (Kh) according to age, the AT calculation more accurately reflects the perceived thermal comfort of the flock, allowing for more precise environmental management and ventilation control. This approach, based on empirical studies, balances physiological relevance with practical feasibility in commercial poultry production. In this study, the wind chill coefficient and wet-heat coefficient were segmented by age, as shown in Table 2.

- iv.

- To remove scale differences among multiple environmental features and accelerate model convergence, Min-Max-Scaler was applied to normalize all parameters, ensuring data values lie within a consistent range. The normalization formula is shown in Equation (2).where denotes the normalized value, is the original data, and and represent the minimum and maximum values of the original environmental data, respectively.

- v.

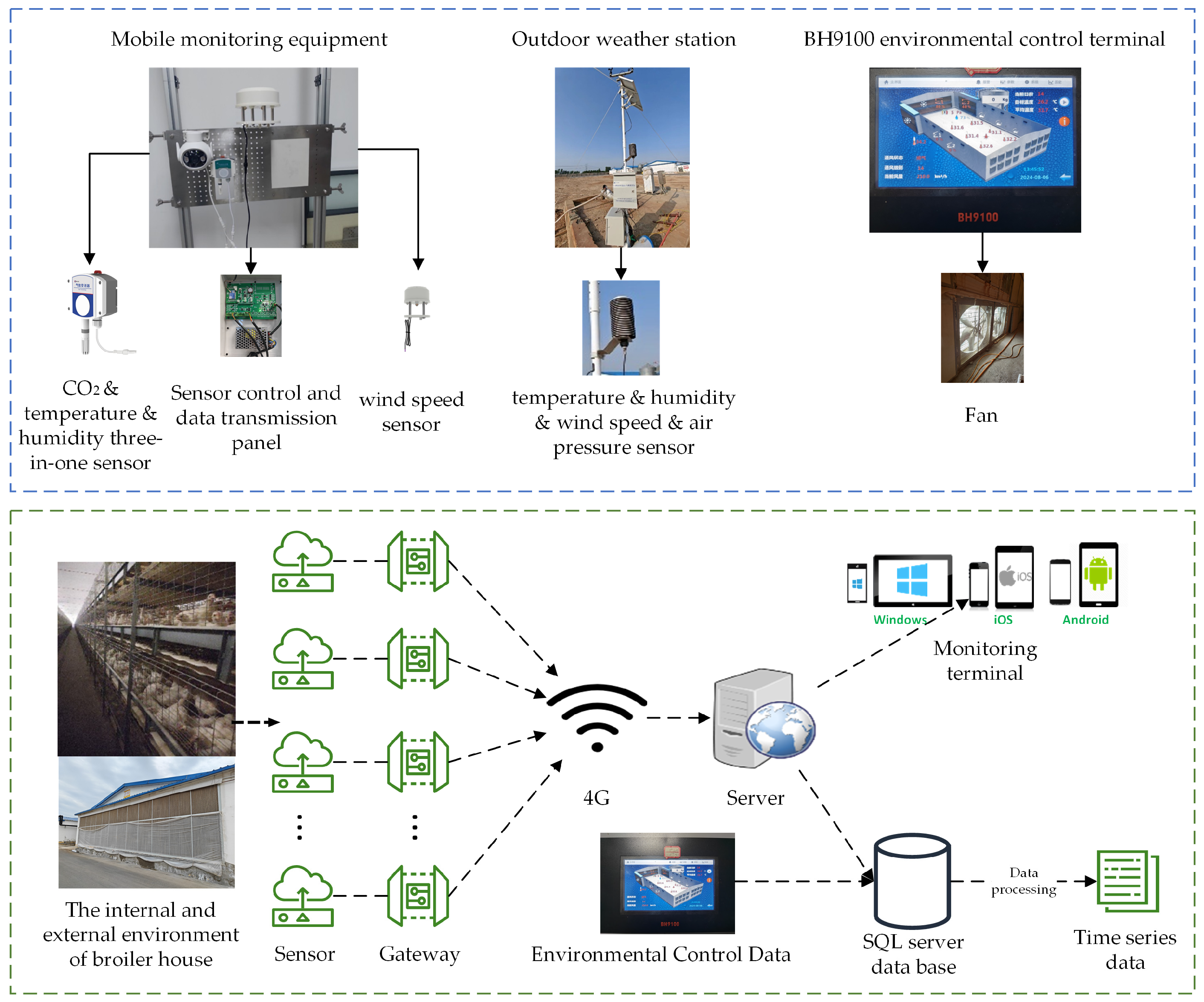

- A sliding window strategy was employed to segment the normalized time series into fixed-length input sequences and their corresponding future outputs, as illustrated in Figure 3. Each input window spanned 180 min, encompassing 36 time steps (5 min per time step), which captures short-term dynamic variations in the broiler house environment. The windows slid along the time series with a step size of one time step (5 min), generating overlapping sequences to increase the number of training samples without losing information. This approach ensures that the model can learn fine-grained temporal dependencies and repetitive patterns in the data, while minimizing the loss of transient or abrupt changes in the environment, thereby enhancing robustness and predictive performance in multi-step forecasting tasks.

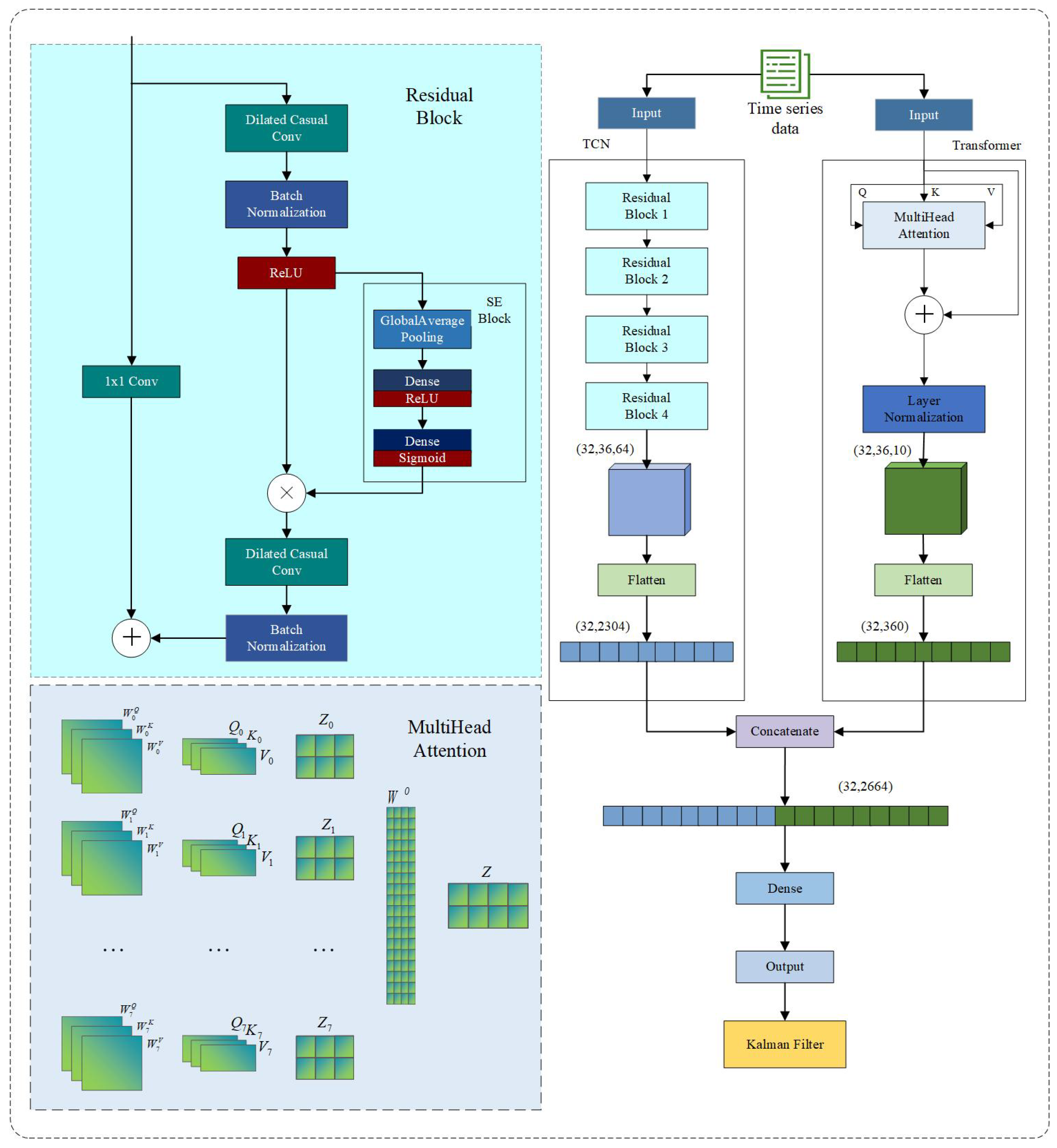

2.2. Model Structure

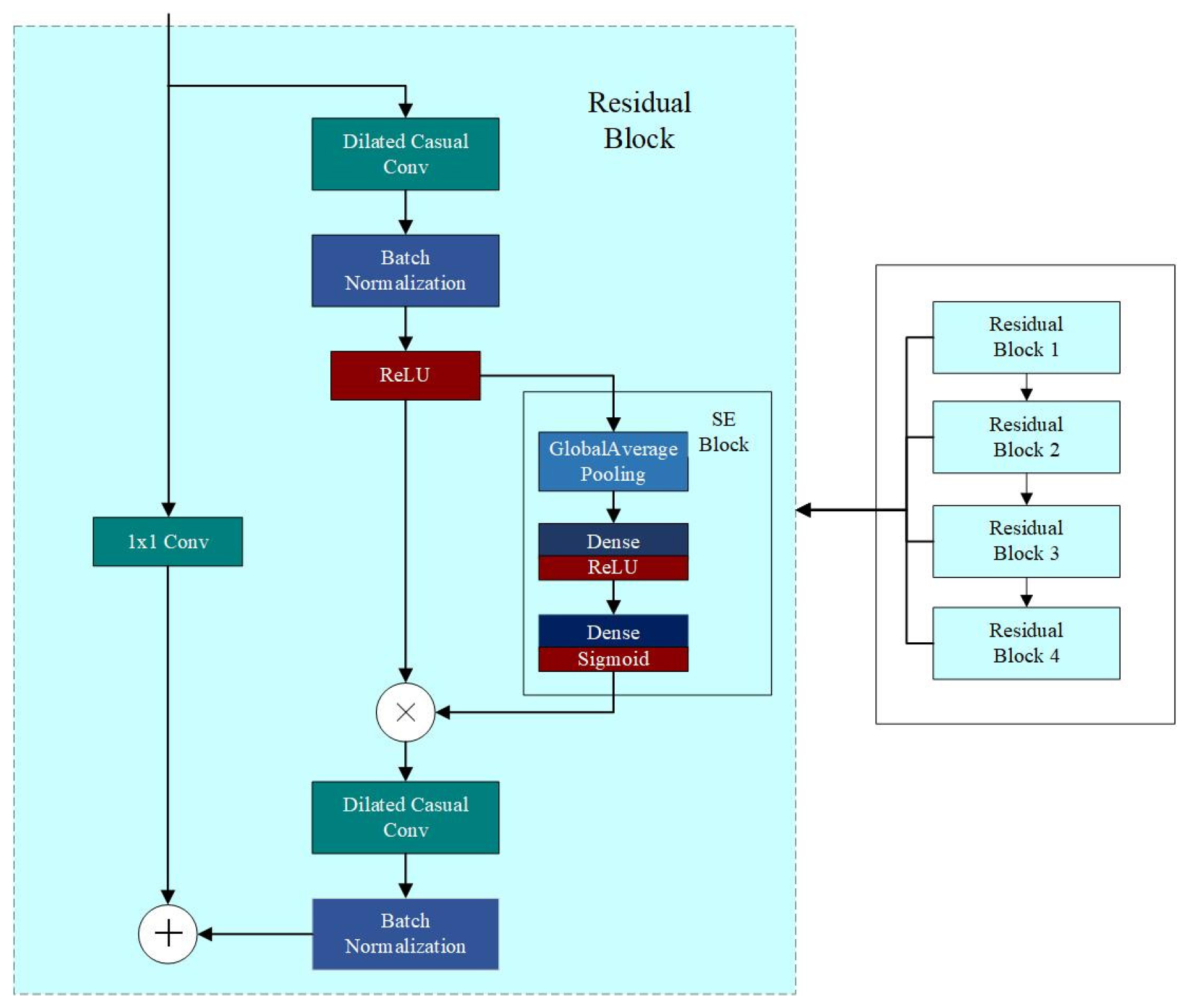

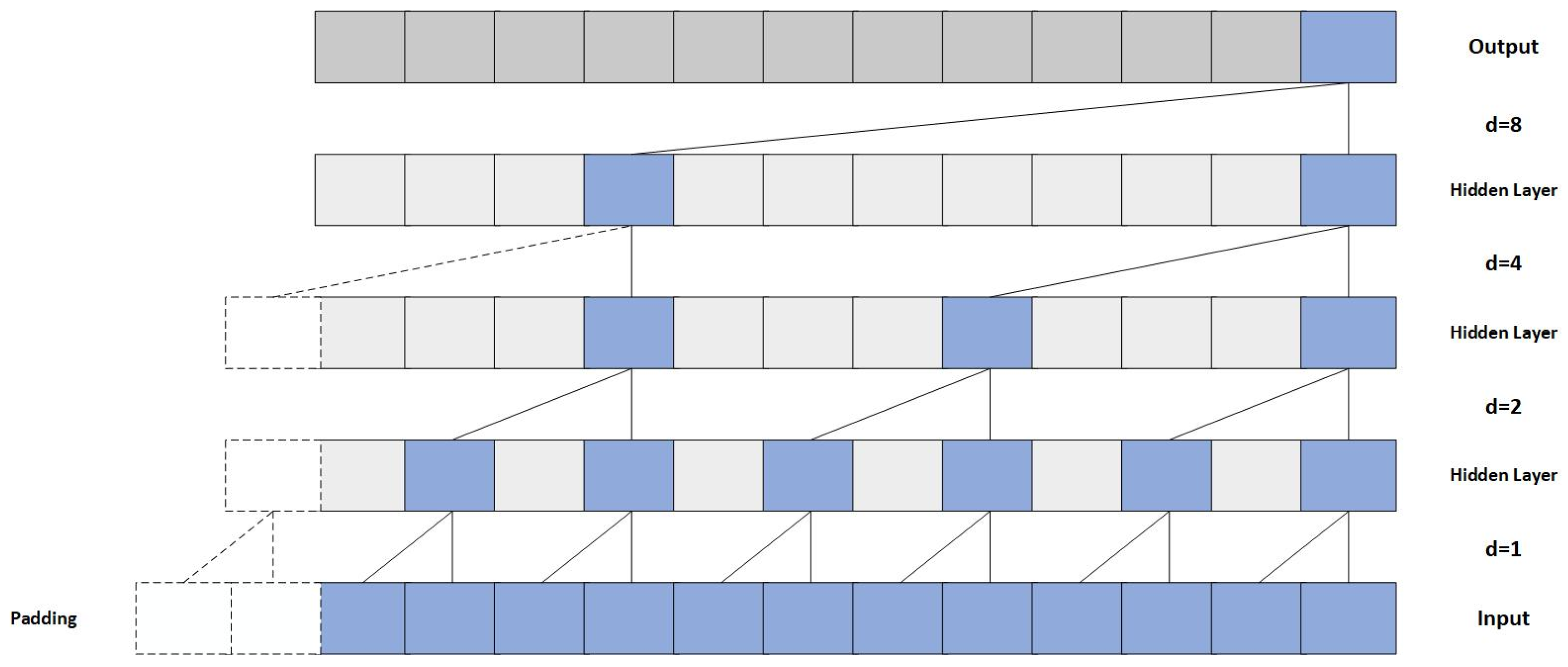

2.2.1. Temporal Convolutional Network (TCN)

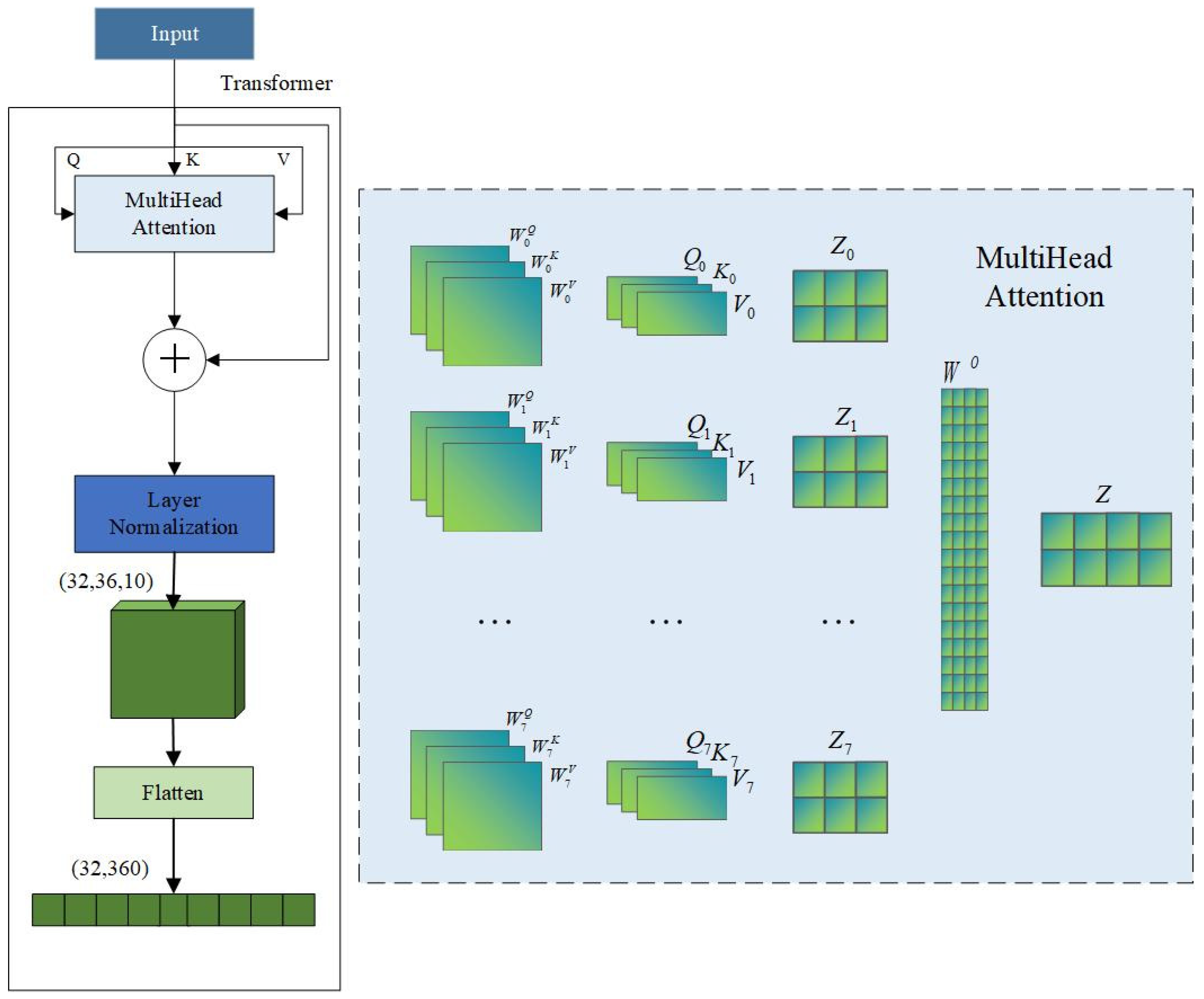

2.2.2. Transformer

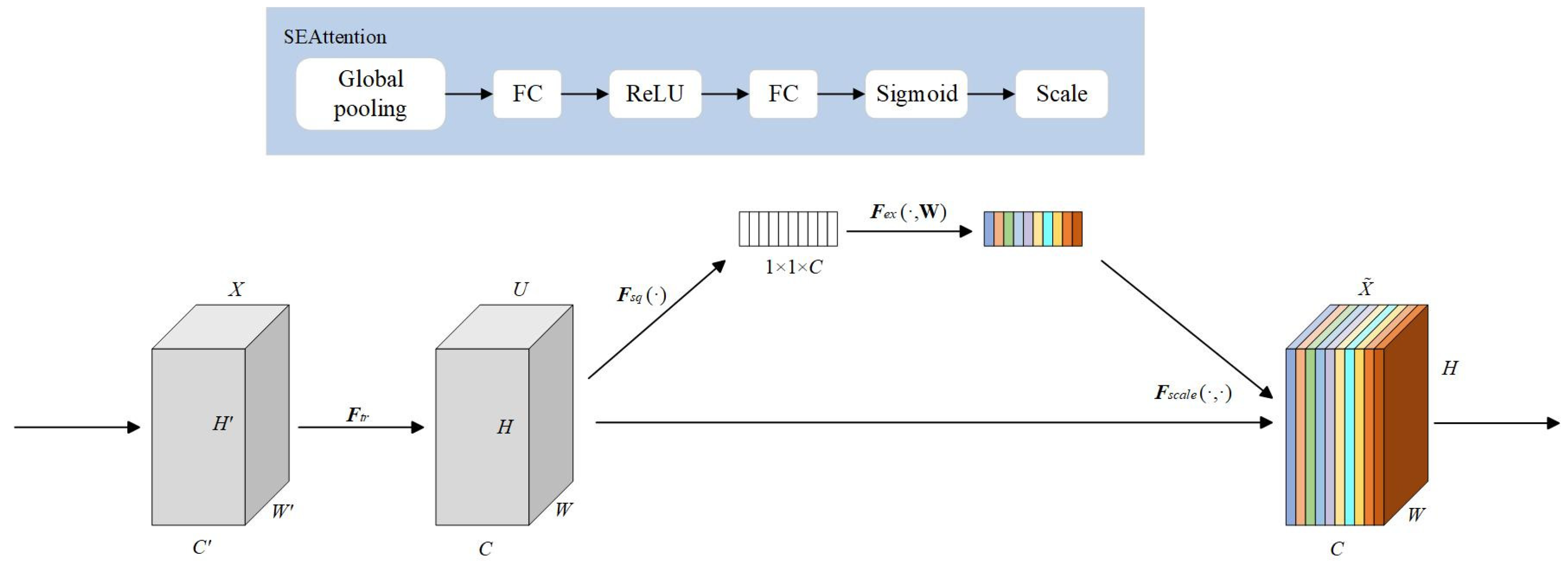

2.2.3. Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE)

2.2.4. Kalman Filter

2.3. Model Evaluation

3. Results

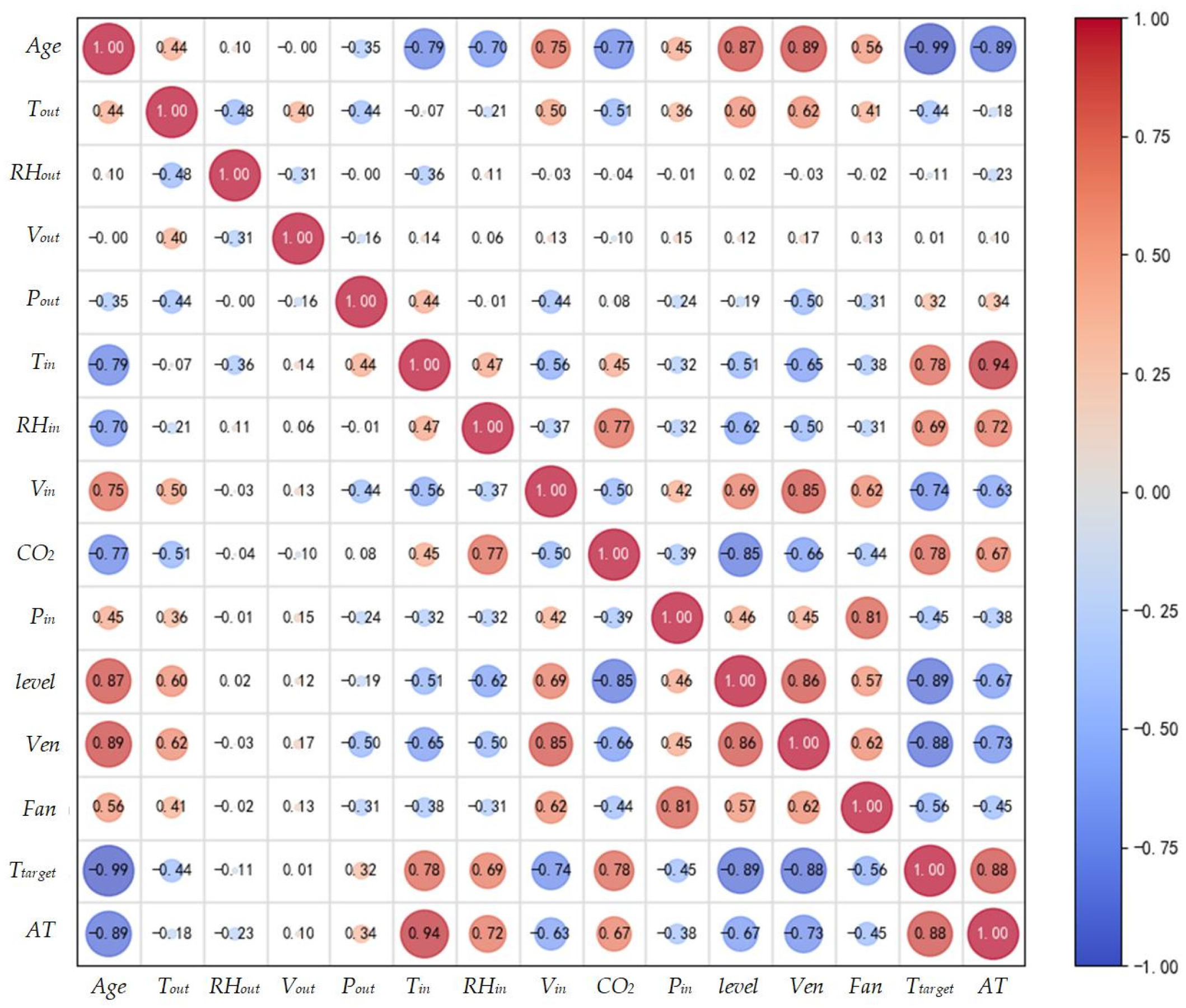

3.1. Correlation Analysis

3.2. Algorithm Parameter Setting

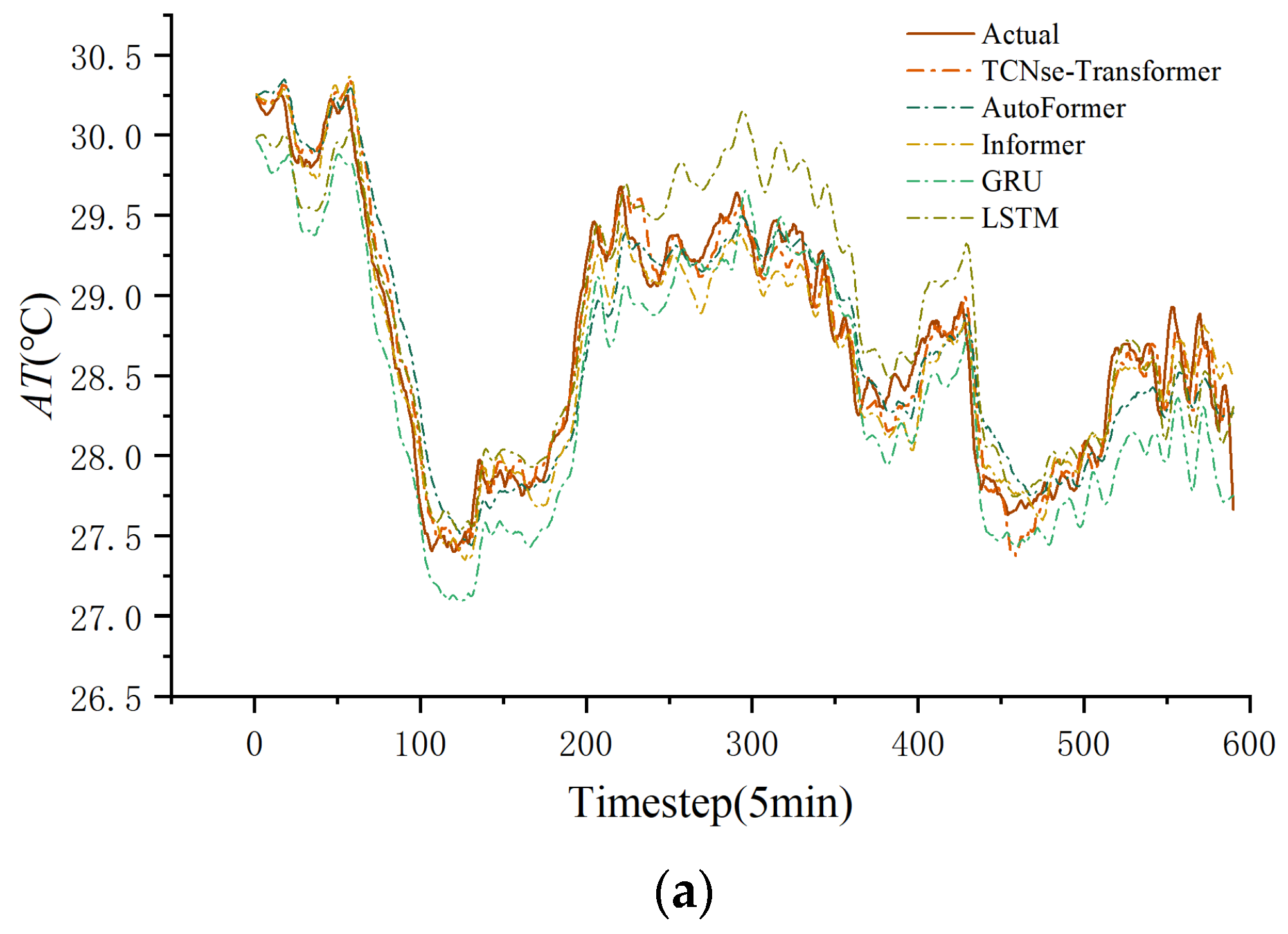

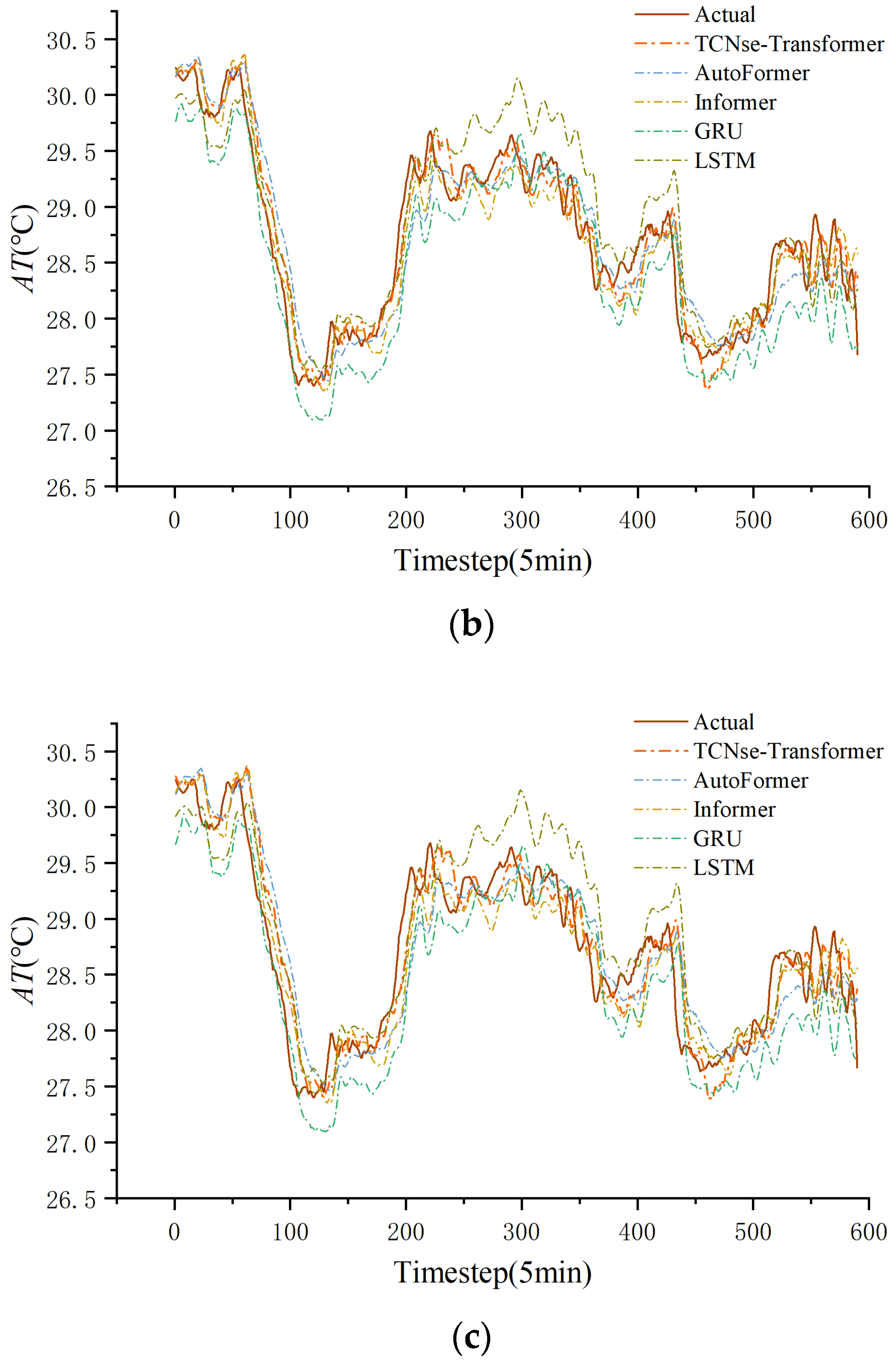

3.3. Comparison of Prediction Performance Among Different Models

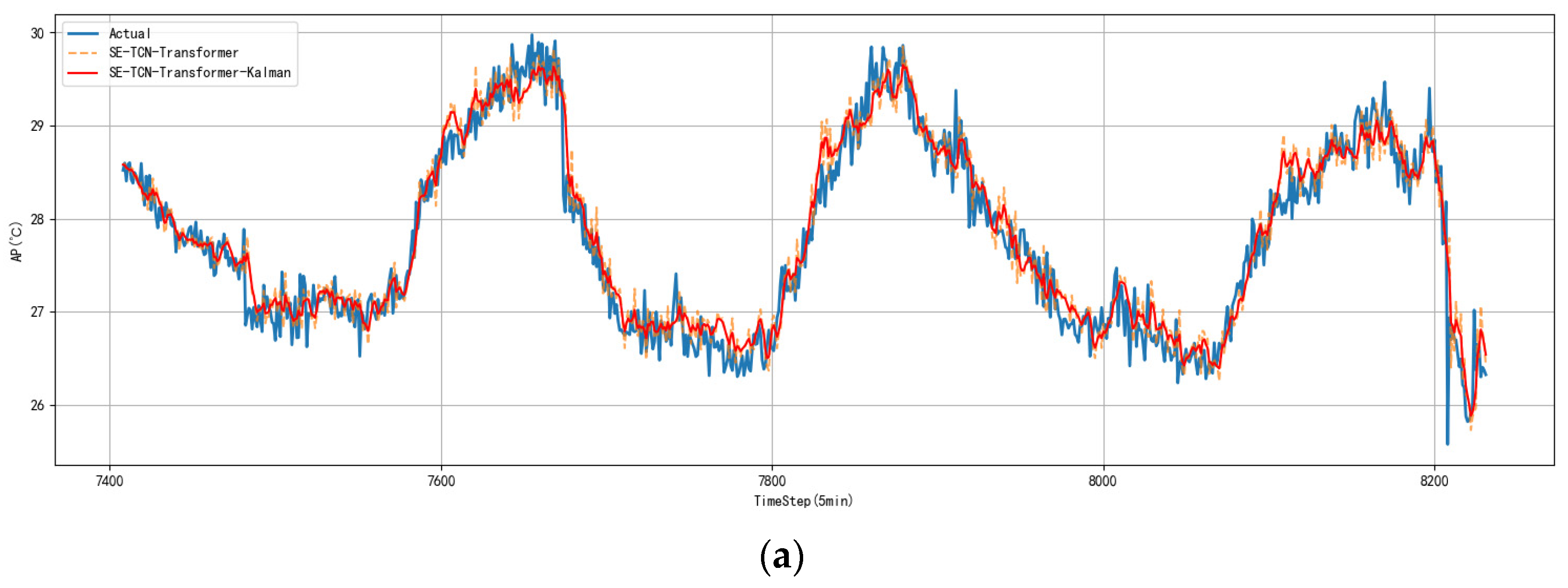

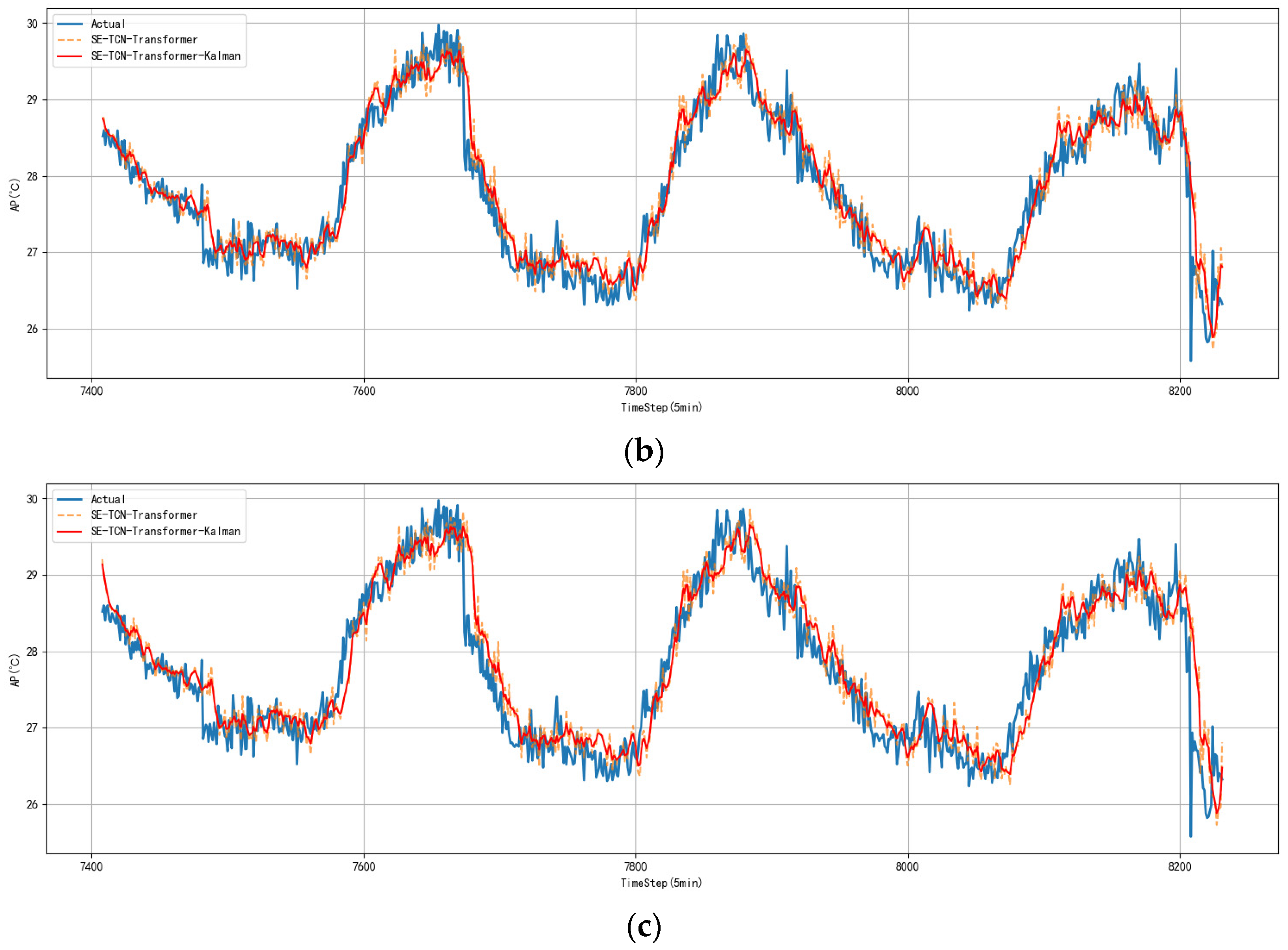

3.4. Ablation Experiment

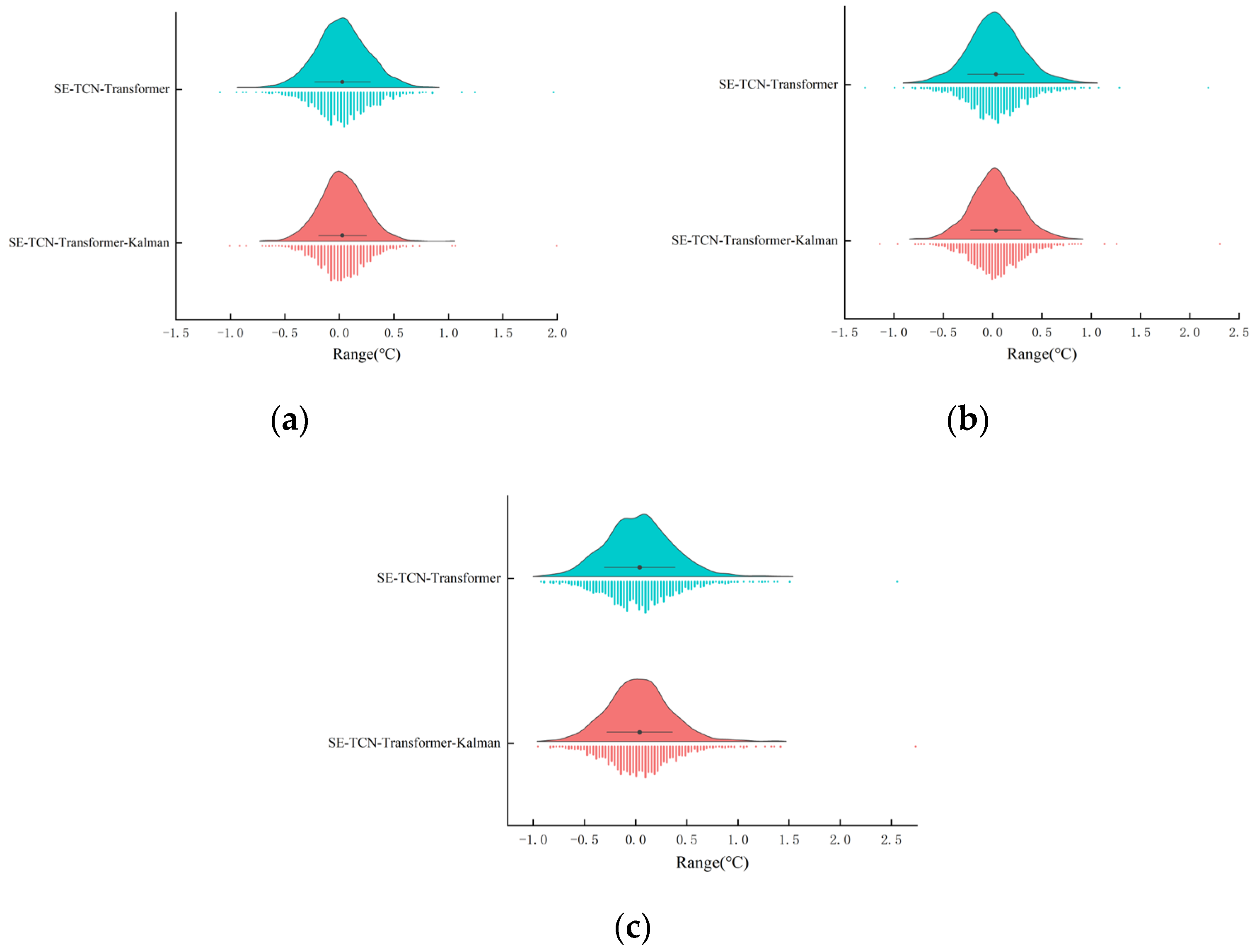

3.5. Model Error Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO (Global Perspective Studies Unit). World Agriculture Towards 2030/2050; Interim Report; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mazunga, F.; Mzikamwi, T.; Mazunga, G.; Mashasha, M.; Mazheke, V. IoT based remote poultry monitoring systems for improving food security and nutrition: Recent trends and issues. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2023, 22, 4–21. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Zhao, X.H.; Yang, L.; Chen, X.Y.; Jiang, R.S.; Jin, S.H.; Geng, Z.Y. Resveratrol alleviates heat stress-induced impairment of intestinal morphology, microflora, and barrier integrity in broilers. Poult. Sci. 2017, 96, 4325–4332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinteiro-Filho, W.M.; Rodrigues, M.V.; Ribeiro, A.; Ferraz-de-Paula, V.; Pinheiro, M.L.; Sá, L.R.M.; Ferreira, A.J.P.; Palermo-Neto, J. Acute heat stress impairs performance parameters and induces mild intestinal enteritis in broiler chickens: Role of acute hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activation. J. Anim. Sci. 2012, 90, 1986–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohail, M.U.; Hume, M.E.; Byrd, J.A.; Nisbet, D.J.; Ijaz, A.; Sohail, A.; Shabbir, M.Z.; Rehman, H. Effect of supplementation of prebiotic mannan-oligosaccharides and probiotic mixture on growth performance of broilers subjected to chronic heat stress. Poult. Sci. 2012, 91, 2235–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, M.; Garcia Neto, M.; Perri, S.; Sandre, D.; Faria, M., Jr.; Oliveira, P.; Pinto, M.; Cassiano, R. Techniques to minimize the effects of acute heat stress or chronic in broilers. Braz. J. Poult. Sci. 2019, 21, eRBCA-2018-0962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, L.F.A.; Espinha, L.P.; de Almeida, E.A.; Lunedo, R.; Furlan, R.L.; Macari, M. How heat stress (continuous or cyclical) interferes with nutrient digestibility, energy and nitrogen balances and performance in broilers. Livest. Sci. 2016, 192, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astill, J.; Dara, R.A.; Fraser, E.D.; Roberts, B.; Sharif, S. Smart poultry management: Smart sensors, big data, and the internet of things. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 170, 105291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Zhang, H.F.; Du, R.; Gu, X.H.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Buyse, J.; Decuypere, E. Thermoregulation responses of broiler chickens to humidity at different ambient temperatures. II. Four weeks of age. Poult. Sci. 2005, 84, 1173–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dozier, W.A., 3rd; Lott, B.D.; Branton, S.L. Growth responses of male broilers subjected to increasing air velocities at high ambient temperatures and a high dew point. Poult. Sci. 2005, 84, 962–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, S.; Cheng, B.; West, D.; Liu, Y.; Qian, Y.; Zou, X.; Classen, J.; Cordova, H.; Oviedo, E.; Wang-Li, L. Impacts of Air Velocity Treatments under Summer Condition: Part I—Heavy Broiler’s Surface Temperature Response. Animals 2022, 12, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, S.T.; da Silva, I.J.O.; Maia, A.S.C.; de Castro, A.C.; Vieira, F.M.C. Mean surface temperature prediction models for broiler chickens—A study of sensible heat flow. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2014, 58, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahav, S. Alleviating heat stress in domestic fowl: Different strategies. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 2009, 65, 719–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.; Xin, H. Acute synergistic effects of air temperature, humidity, and velocity on homeostasis of market-size broilers. Trans. ASAE 2003, 46, 491–497. [Google Scholar]

- García, R.; Aguilar, J.; Toro, M.; Pinto, A.; Rodríguez, P. A systematic literature review on the use of machine learning in precision livestock farming. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 179, 105826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berckmans, D. General introduction to precision livestock farming. Anim. Front. 2017, 7, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Yang, J.; Zhang, H.; Fang, C. Enhanced Methodology and Experimental Research for Caged Chicken Counting Based on YOLOv8. Animals 2025, 15, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trentin, A.; Talamini, D.J.D.; Coldebella, A.; Pedroso, A.C.; Gomes, T.M.A. Technical and economic performance favours fully automated climate control broiler housing. Br. Poult. Sci. 2025, 66, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gautam, K.R.; Zhang, G.; Landwehr, N.; Adolphs, J. Machine learning for improvement of thermal conditions inside a hybrid ventilated animal building. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 187, 106259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Imran, M.; Baig, M.S.; Shah, A.; Ullah, S.S.; Alroobaea, R.; Iqbal, J. Intelligent control shed poultry farm system incorporating with machine learning. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 58168–58180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Li, L.; Jia, Y.; Xie, Z.; Yu, Y.; Huo, L. CFD Investigation on Combined Ventilation System for Multilayer-Caged-Laying Hen Houses. Animals 2024, 14, 2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, M.; Yu, Y.; Jia, Y.; Qian, Z.; Xie, Z. Modeling and Regulation of Dynamic Temperature for Layer Houses Under Combined Positive- and Negative-Pressure Ventilation. Animals 2024, 14, 3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantino, A.; Fabrizio, E.; Ghiggini, A.; Bariani, M. Climate control in broiler houses: A thermal model for the calculation of the energy use and indoor environmental conditions. Energy Build. 2018, 169, 110–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, T.; Sun, D.-W.; Grant, J.; Fallon, R.; Dodd, V. Applications of computational fluid dynamics (CFD) in the modelling and design of ventilation systems in the agricultural industry: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2007, 98, 2386–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjerg, B.; Cascone, G.; Lee, I.-B.; Bartzanas, T.; Norton, T.; Hong, S.-W.; Seo, I.-H.; Banhazi, T.; Liberati, P.; Marucci, A.; et al. Modelling of ammonia emissions from naturally ventilated livestock buildings. Part 3: CFD modelling. Biosyst. Eng. 2013, 116, 259–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selle, M.; Spieß, F.; Visscher, C.; Rautenschlein, S.; Jung, A.; Auerbach, M.; Hartung, J.; Sürie, C.; Distl, O. Real-Time Monitoring of Animals and Environment in Broiler Precision Farming—How Robust Is the Data Quality? Sustainability 2023, 15, 15527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neethirajan, S. The role of sensors, big data and machine learning in modern animal farming. Sens. Bio-Sens. Res. 2020, 29, 100367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, A.A.G.; Nääs, I.d.A.; de Carvalho-Curi, T.M.R.; Abe, J.M.; Lima, N.D.d.S. A Heuristic and data mining model for predicting broiler house environment suitability. Animals 2021, 11, 2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Er, M.; Li, L.; Wen, P.; Jia, Y.; Huo, L. Microclimate environment model construction and control strategy of enclosed laying brooder house. Poult. Sci. 2022, 101, 101843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yang, L.; Xue, H.; Li, L.; Yu, Y. A Machine Learning Model Based on GRU and LSTM to Predict the Environmental Parameters in a Layer House, Taking CO2 Concentration as an Example. Sensors 2023, 24, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, M.R.; Besteiro, R.; Ortega, J.A.; Fernandez, M.D.; Arango, T. Evolution and Neural Network Prediction of CO2 Emissions in Weaned Piglet Farms. Sensors 2022, 22, 2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küçüktopçu, E.; Cemek, B.; Simsek, H. Machine Learning and Wavelet Transform: A Hybrid Approach to Predicting Ammonia Levels in Poultry Farms. Animals 2024, 14, 2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Teng, G.; Zhou, Z. Short-Term Prediction Method for Gas Concentration in Poultry Houses Under Different Feeding Patterns. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Yin, Z.; Lyu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Gao, P. Research on Indoor Environment Prediction of Pig House Based on OTDBO–TCN–GRU Algorithm. Animals 2024, 14, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Kolter, J.Z.; Koltun, V. An empirical evaluation of generic convolutional and recurrent networks for sequence modeling. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.01271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Teng, G. Multistep prediction of temperature and humidity in poultry houses based on the GFF-transformer model. Front. Agric. Sci. Eng. 2025, 12, 803–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Xu, J.; Wang, J.; Long, M. Autoformer: Decomposition transformers with auto-correlation for long-term series forecasting. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 22419–22430. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.; Zhang, S.; Peng, J.; Zhang, S.; Li, J.; Xiong, H.; Zhang, W. Informer: Beyond Efficient Transformer for Long Sequence Time-Series Forecasting. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2021, 35, 11106–11115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zeng, A.; Chen, M.; Xu, Z.; Lai, Q.; Ma, L.; Xu, Q. Scinet: Time series modeling and forecasting with sample convolution and interaction. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 5816–5828. [Google Scholar]

- Fournel, S.; Rousseau, A.N.; Laberge, B. Rethinking environment control strategy of confined animal housing systems through precision livestock farming. Biosyst. Eng. 2017, 155, 96–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Zhang, K.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, B. Parallel spatio-temporal attention-based TCN for multivariate time series prediction. Neural Comput. Appl. 2023, 35, 13109–13118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing Systems 30 (NIPS 2017), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Li, S.; Gang, S. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Särkkä, S.; Lennart, S. Bayesian Filtering and Smoothing; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023; Volume 17. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, F.; Zhao, X.; Shi, Z.; Li, H.; Zhao, W. Environmental Factor Detection and Analysis Technologies in Livestock and Poultry Houses: A Review. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, S.S.; Iranmanesh, S.H.; Hassani, H. Optimizing Multivariate Time Series Forecasting with Data Augmentation. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2024, 17, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, L.; Liu, Q.; Peng, H.; Wang, J.; Yang, Q. Multivariate time series forecasting method based on nonlinear spiking neural P systems and non-subsampled shearlet transform. Neural Netw. 2022, 152, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Küçüktopcu, E.; Cemek, B.; Simsek, H.; Ni, J.-Q. Computational Fluid Dynamics Modeling of a Broiler House Microclimate in Summer and Winter. Animals 2022, 12, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, L.-Y.; Daniel, K.F.; Lee, S.-Y.; Lee, C.-R.; Park, J.-Y.; Park, J.; Hong, S.-W. CFD Simulation of Dynamic Temperature Variations Induced by Tunnel Ventilation in a Broiler House. Animals 2024, 14, 3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, H. SCINet applied in multi-scale long-sequence power load forecasting. Electronics 2025, 14, 1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, M. Informer-based model for long-term hydrological forecasting of reservoir flood discharge. Water 2024, 16, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, J.; Xu, L.; Zhong, J.; Yuan, P. Research on Autoformer-based electricity load forecasting and analysis. J. East China Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2023, 2023, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sensor Index | Unit | Range | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | °C | −20~+50 °C | ±0.2 °C |

| Humidity | % | 0~100% RH | ±2% RH |

| Wind speed | m/s | 0.1~5 m/s | ±(0.2 m/s ± 0.02 × v) |

| Carbon dioxide | ppm | 300~5000 ppm | ±50 ppm |

| Negative Pressure | Pa | 0~20,000 Pa | ±5 Pa |

| Atmospheric Pressure | Pa | 9000~110,000 Pa | ±100 Pa |

| Correlation Level | Extremely Relevant | Strong Relevant | Medium Relevant | Weak Relevant | Extremely Weak Relevant | Irrelevant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | 0.8 < |r| ≤ 1.0 | 0.6 < |r| ≤ 0.8 | 0.4 < |r| ≤ 0.6 | 0.2 < |r| ≤ 0.4 | 0 < |r| ≤ 0.2 | 0 |

| Parameter | Description | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Age of broiler chickens | Day |

| Indoor temperature | °C | |

| Indoor humidity | % | |

| Indoor wind speed | m/s | |

| CO2 | CO2 concentration in the house | ppm |

| level | Grades of ventilation | level |

| Ven | Ventilation rate | m3/h |

| Fan | Number of fans | - |

| Target temperature | °C | |

| AT | Apparent temperature | °C |

| Time | Parameter | Monitoring Sites | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | ||

| 9 April 2024 14:09 | Tin (°C) | 32.60 | 32.90 | 32.80 | 32.6 | 32.30 | 33.20 | 33.20 | 32.40 | 31.20 | 31.50 | 31.30 | 30.80 |

| RHin (%) | 60.80 | 60.20 | 65.00 | 61.60 | 59.20 | 48.50 | 48.20 | 57.10 | 52.00 | 51.40 | 50.90 | 50.70 | |

| AT (°C) | 32.68 | 32.92 | 33.30 | 32.76 | 32.22 | 32.05 | 32.02 | 32.11 | 30.40 | 30.64 | 30.39 | 29.87 | |

| 10 April 2024 0:39 | Tin (°C) | 29.60 | 29.80 | 29.80 | 29.50 | 30.40 | 31.20 | 31.00 | 30.56 | 30.00 | 30.00 | 30.00 | 29.50 |

| RHin (%) | 63.70 | 63.10 | 65.30 | 62.90 | 53.10 | 48.20 | 47.00 | 52.95 | 50.10 | 47.80 | 47.30 | 48.80 | |

| AT (°C) | 29.32 | 30.11 | 30.33 | 29.79 | 29.71 | 30.02 | 29.05 | 29.86 | 29.01 | 28.78 | 28.73 | 28.38 | |

| 10 April 2024 14:22 | Tin (°C) | 31.70 | 32.20 | 32.20 | 31.70 | 31.20 | 32.00 | 32.00 | 31.64 | 30.00 | 30.20 | 30.10 | 29.50 |

| RHin (%) | 60.20 | 55.70 | 60.20 | 57.30 | 53.50 | 50.80 | 51.30 | 53.03 | 59.00 | 58.30 | 57.40 | 57.20 | |

| AT (°C) | 31.72 | 31.77 | 32.22 | 31.43 | 30.55 | 31.08 | 31.13 | 30.94 | 29.90 | 30.03 | 29.84 | 29.22 | |

| 11 April 2024 0:50 | Tin (°C) | 30.40 | 30.50 | 30.60 | 30.40 | 30.30 | 31.10 | 31.00 | 30.60 | 29.20 | 29.30 | 29.20 | 28.70 |

| RHin (%) | 66.60 | 65.90 | 68.00 | 66.60 | 62.00 | 52.50 | 53.60 | 61.20 | 57.80 | 55.70 | 56.80 | 54.80 | |

| AT (°C) | 31.06 | 31.09 | 31.04 | 31.06 | 30.20 | 30.35 | 30.36 | 30.72 | 28.98 | 28.87 | 28.88 | 28.18 | |

| 11 April 2024 14:06 | Tin (°C) | 32.50 | 33.00 | 33.10 | 32.60 | 32.20 | 32.90 | 33.00 | 32.40 | 31.40 | 31.40 | 31.70 | 31.00 |

| RHin (%) | 60.10 | 54.80 | 51.00 | 51.90 | 52.00 | 49.00 | 49.00 | 51.20 | 58.30 | 58.60 | 54.70 | 56.50 | |

| AT (°C) | 32.31 | 32.18 | 32.20 | 30.79 | 31.40 | 31.80 | 31.90 | 31.52 | 31.23 | 31.26 | 31.17 | 30.65 | |

| Model | Total Number of Parameters | Metric | Prediction Step | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t + 1 (5 min) | t + 3 (15 min) | t + 6 (30 min) | |||

| LSTM | 94,949 | MAE (°C) | 0.312 | 0.331 | 0.360 |

| RMSE (°C) | 0.394 | 0.424 | 0.473 | ||

| R2 | 0.843 | 0.819 | 0.774 | ||

| GRU | 72,869 | MAE (°C) | 0.285 | 0.300 | 0.324 |

| RMSE (°C) | 0.356 | 0.382 | 0.425 | ||

| R2 | 0.872 | 0.853 | 0.818 | ||

| Autoformer | 84,017 | MAE (°C) | 0.250 | 0.281 | 0.326 |

| RMSE (°C) | 0.326 | 0.367 | 0.425 | ||

| R2 | 0.893 | 0.864 | 0.818 | ||

| Informer | 256,133 | MAE (°C) | 0.258 | 0.276 | 0.304 |

| RMSE (°C) | 0.332 | 0.359 | 0.399 | ||

| R2 | 0.889 | 0.870 | 0.839 | ||

| SE-TCN- Transformer | 200,727 | MAE (°C) | 0.195 | 0.218 | 0.265 |

| RMSE (°C) | 0.256 | 0.288 | 0.346 | ||

| R2 | 0.937 | 0.917 | 0.879 | ||

| Model | Metric | Prediction Step | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| t + 1 (5 min) | t + 3 (15 min) | t + 6 (30 min) | ||

| TCN | MAE (°C) | 0.270 | 0.296 | 0.331 |

| RMSE (°C) | 0.353 | 0.385 | 0.437 | |

| R2 | 0.874 | 0.850 | 0.807 | |

| Transformer | MAE (°C) | 0.213 | 0.247 | 0.290 |

| RMSE (°C) | 0.280 | 0.322 | 0.379 | |

| R2 | 0.921 | 0.895 | 0.855 | |

| SE-TCN | MAE (°C) | 0.231 | 0.252 | 0.283 |

| RMSE (°C) | 0.305 | 0.336 | 0.379 | |

| R2 | 0.906 | 0.886 | 0.855 | |

| SE-TCN–Transformer | MAE (°C) | 0.195 | 0.218 | 0.265 |

| RMSE (°C) | 0.256 | 0.288 | 0.346 | |

| R2 | 0.937 | 0.917 | 0.879 | |

| SE-TCN– Transformer–Kalman | MAE (°C) | 0.168 | 0.197 | 0.244 |

| RMSE (°C) | 0.222 | 0.261 | 0.328 | |

| R2 | 0.950 | 0.931 | 0.895 | |

| Error Statistics | SE-TCN–Transformer | SE-TCN–Transformer–Kalman | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t + 1 | t + 3 | t + 6 | t + 1 | t + 3 | t + 6 | |

| Min | −1.080 | −1.286 | −0.924 | −1.009 | −1.131 | −0.955 |

| Q1 | −0.131 | −0.138 | −0.184 | −0.105 | −0.129 | −0.162 |

| Median | 0.023 | 0.028 | 0.035 | 0.022 | 0.024 | 0.027 |

| Q3 | 0.184 | 0.205 | 0.240 | 0.164 | 0.191 | 0.214 |

| Max | 1.963 | 2.199 | 2.548 | 1.985 | 2.300 | 2.722 |

| IQR | 0.315 | 0.343 | 0.424 | 0.269 | 0.320 | 0.377 |

| Outler Count | 30 | 35 | 35 | 25 | 28 | 37 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zheng, P.; Zhang, W.; Gao, B.; Ma, Y.; Chen, C. Multi-Step Apparent Temperature Prediction in Broiler Houses Using a Hybrid SE-TCN–Transformer Model with Kalman Filtering. Sensors 2025, 25, 6124. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25196124

Zheng P, Zhang W, Gao B, Ma Y, Chen C. Multi-Step Apparent Temperature Prediction in Broiler Houses Using a Hybrid SE-TCN–Transformer Model with Kalman Filtering. Sensors. 2025; 25(19):6124. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25196124

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Pengshen, Wanchao Zhang, Bin Gao, Yali Ma, and Changxi Chen. 2025. "Multi-Step Apparent Temperature Prediction in Broiler Houses Using a Hybrid SE-TCN–Transformer Model with Kalman Filtering" Sensors 25, no. 19: 6124. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25196124

APA StyleZheng, P., Zhang, W., Gao, B., Ma, Y., & Chen, C. (2025). Multi-Step Apparent Temperature Prediction in Broiler Houses Using a Hybrid SE-TCN–Transformer Model with Kalman Filtering. Sensors, 25(19), 6124. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25196124