Multi-IRS-Assisted mmWave UAV-BS Network for Coverage Extension

Abstract

1. Introduction

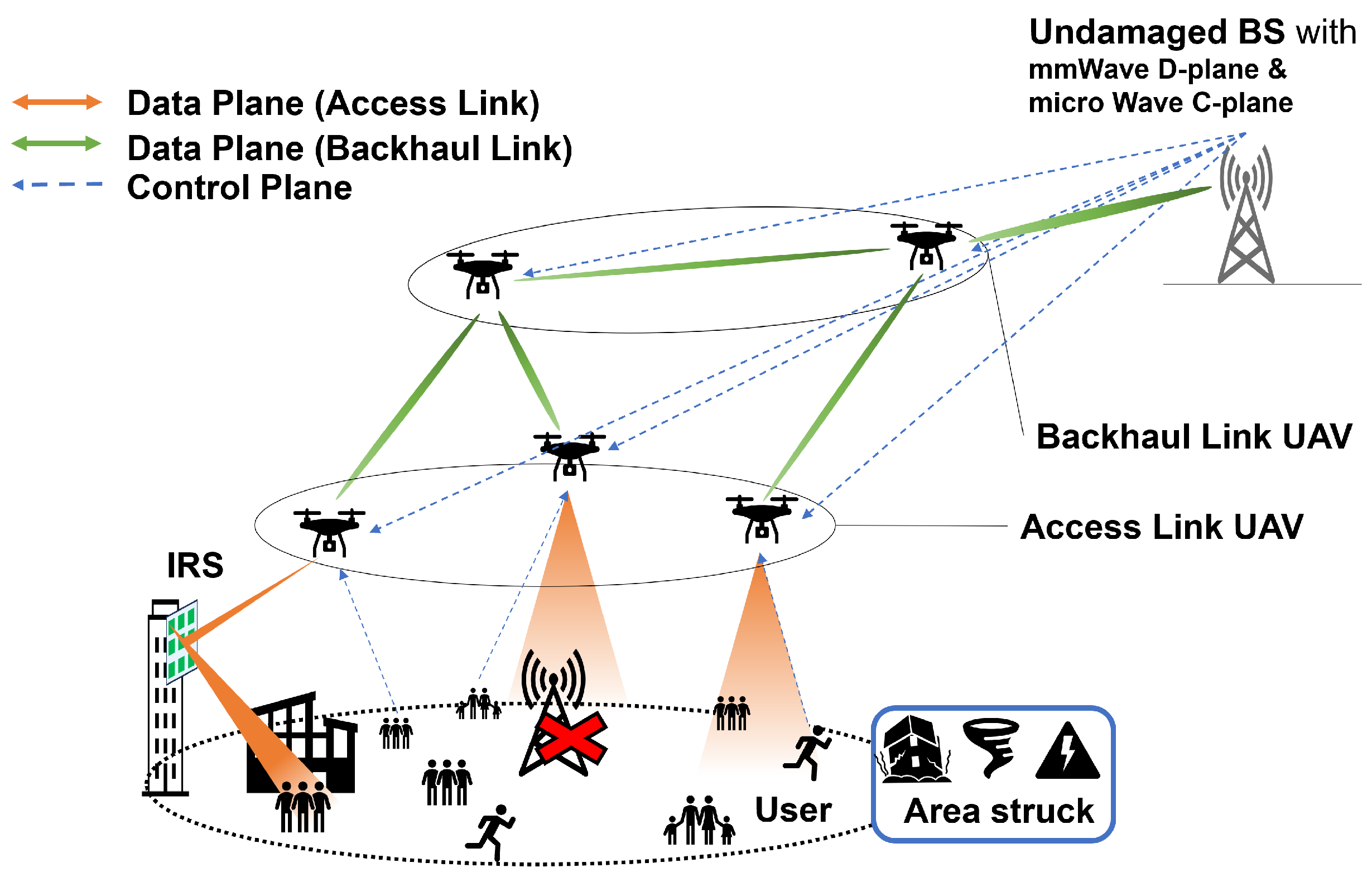

- We propose a system model for multi-IRS-assisted UAV-BS networks to extend the coverage of mmWave communications.

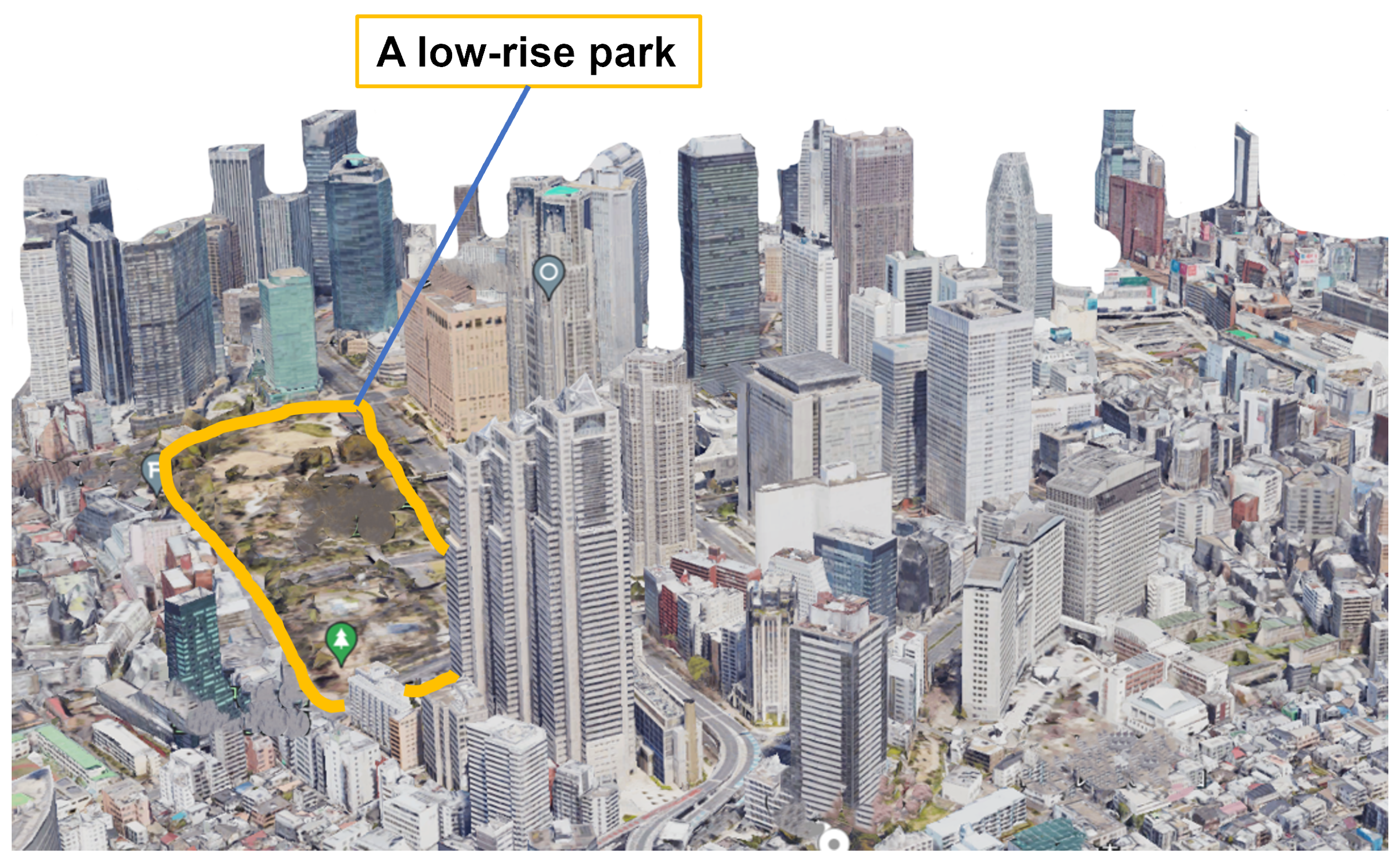

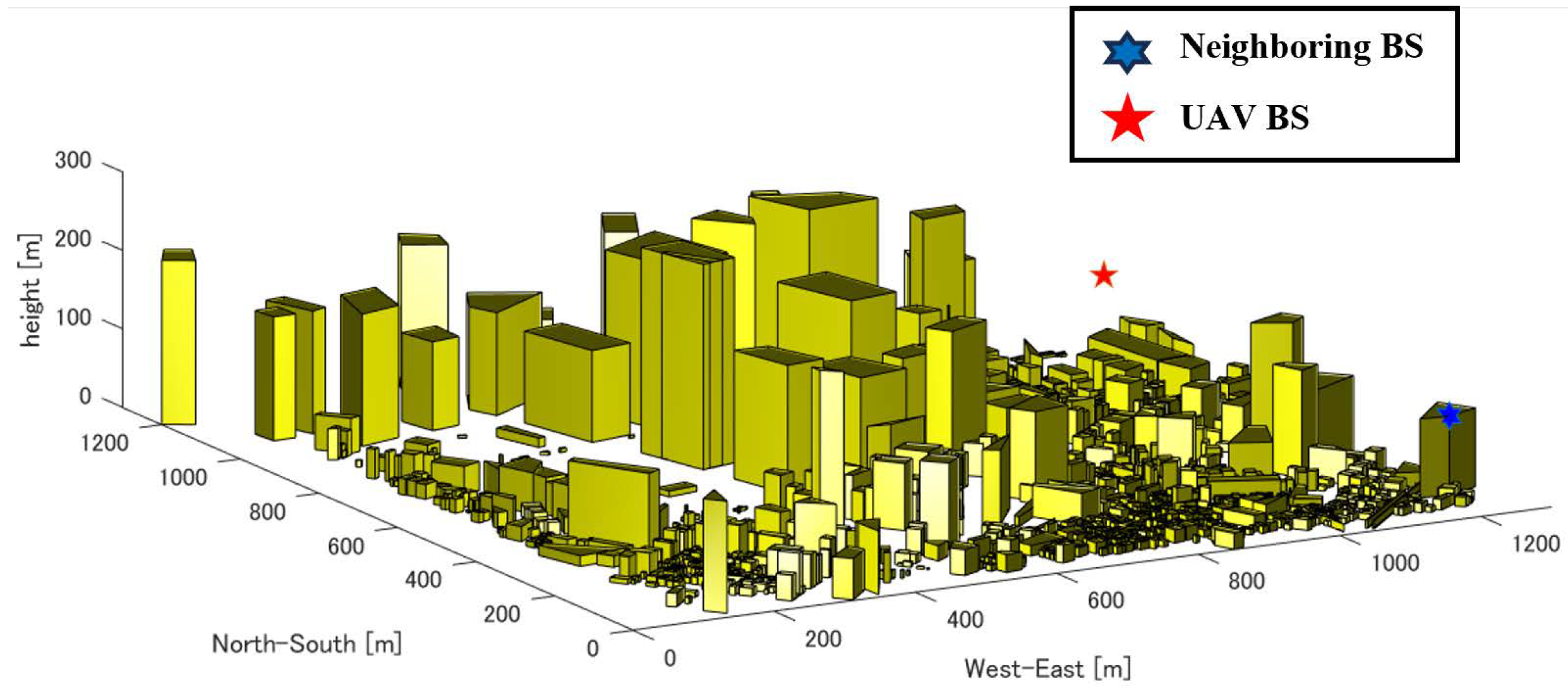

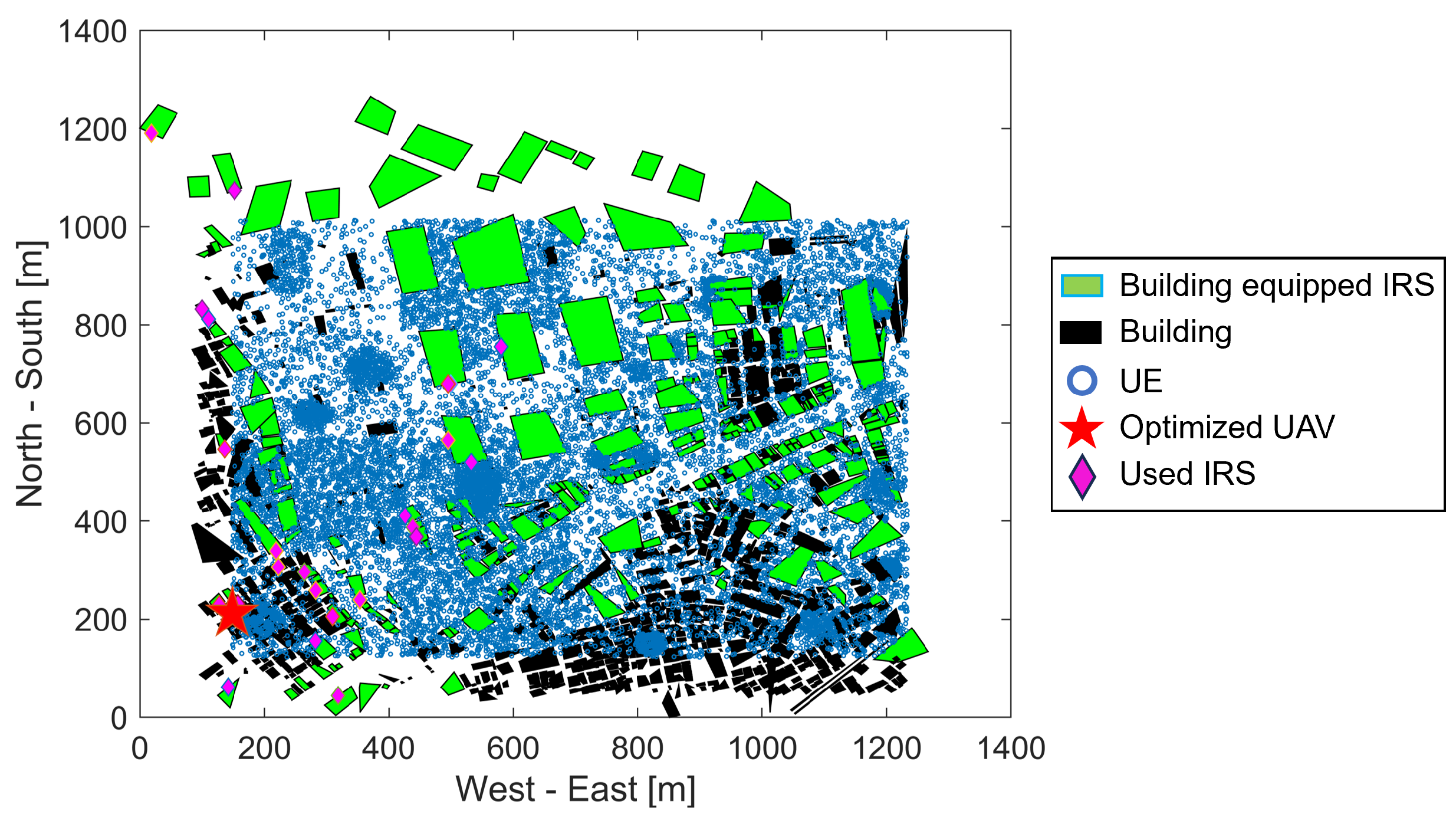

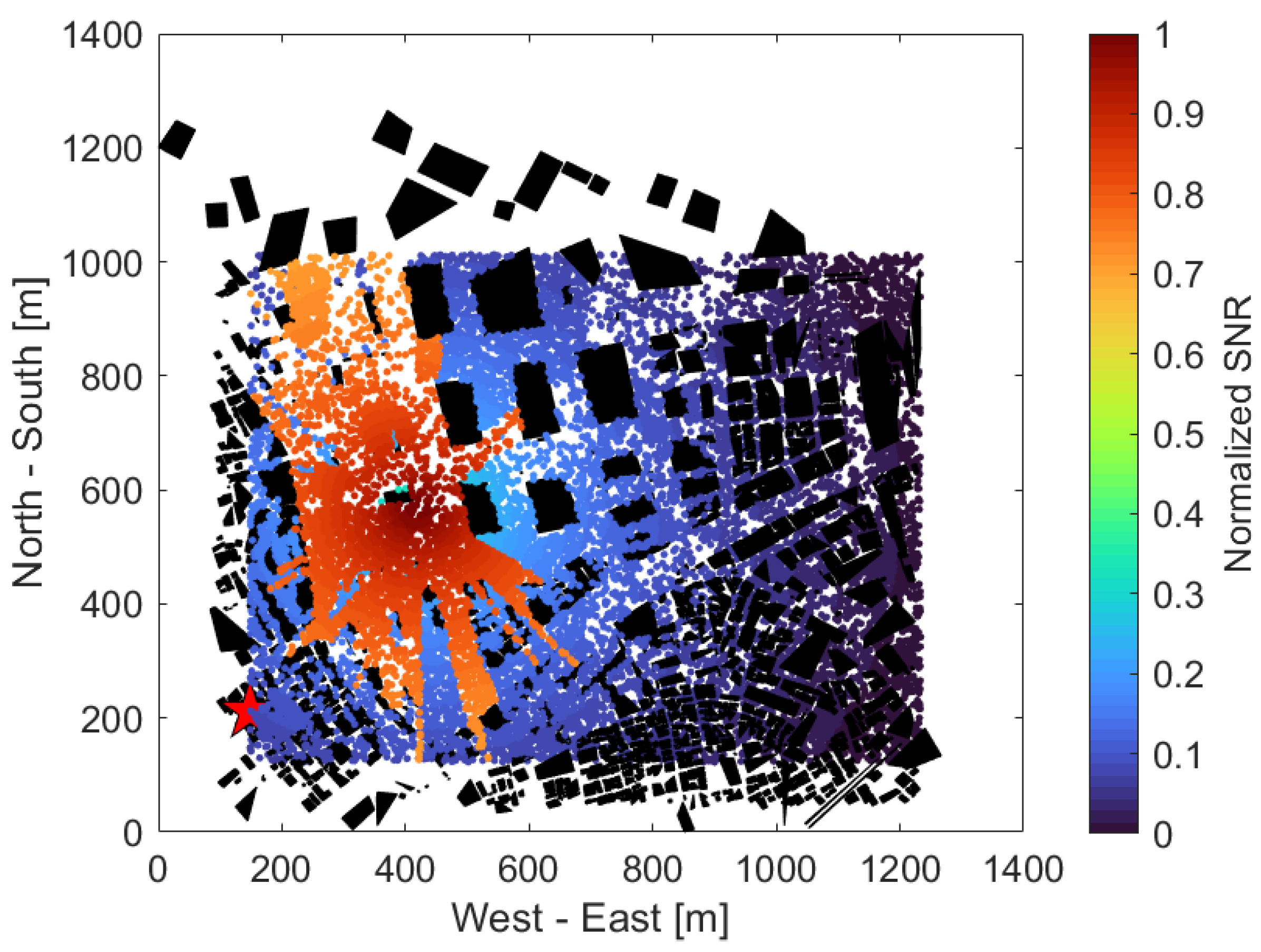

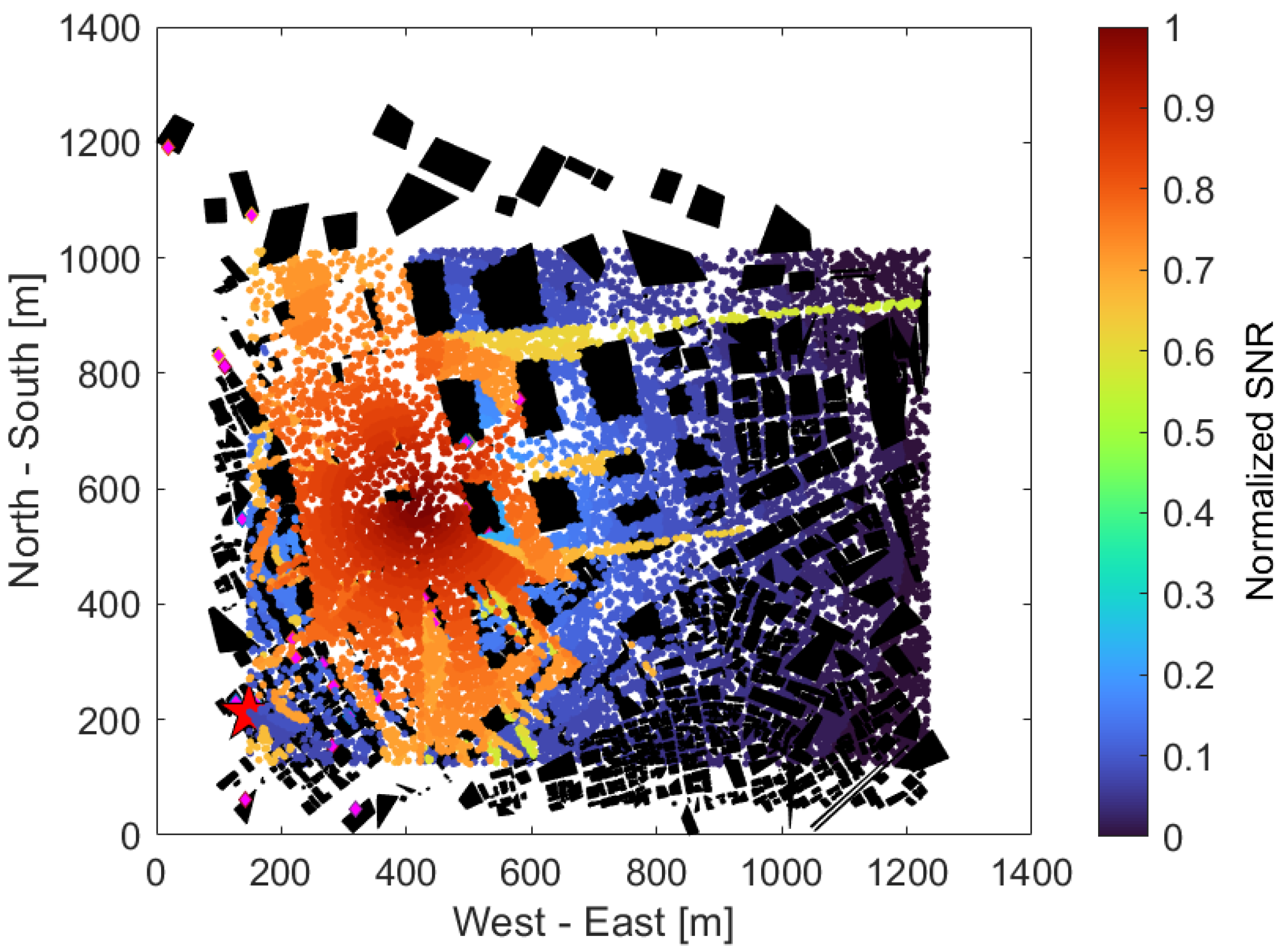

- We construct a three-dimensional environment based on actual field data and evaluate the proposed system through numerical analysis.

2. Related Work

2.1. IRS Only or Integrated to BS

2.2. IRS on UAV

2.3. IRS Collaborated with UAV-BS

3. Architecture and System Model

3.1. Architecture

3.2. System Model

Path Loss Model and Calculation of UE Received SNR

4. Proposed IRS Selection and Access Link Connection Approach with 3D Simulation Environment

4.1. Access Link Connection

| Algorithm 1 Decision of communication link between UAV and UE |

|

4.2. UAV Position Optimization

5. Simulation Results and Discussion

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| NTN | Nonterrestrial Network |

| mmWave | Millimeter Wave |

| IRS | Intelligent Reflective Surface |

| LoS | Line-of-Sight |

| UE | User Equipment |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| BS | Base Station |

| AF | Amplified-and-Forward |

| DF | Decode-and-Forward |

| SNR | Signal to Noise Ratio |

| NLoS | Non-Line-of-Sight |

| BF | Beamforming |

| TDMA | Time Division Multiaccess |

| EIRP | Equivalent Isotropic Radiation Power |

References

- Jagatheesaperumal, S.K.; Rahouti, M. Building Digital Twins of Cyber Physical Systems with Metaverse for Industry 5.0 and Beyond. IT Prof. 2022, 24, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inokuchi, K.; Nakazato, J.; Tsukada, M.; Esaki, H. Semantic digital twin for interoperability and Comprehensive Management of Data Assets. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Metaverse Computing, Networking and Applications (MetaCom), Kyoto, Japan, 26–28 June 2023; pp. 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DJI Comparison of Consumer Drones. Available online: https://www.dji.com/jp/products/comparison-consumer-drones (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Utsav, A.; Abhishek, A.; Suraj, P.; Badhai, R.K. An IoT Based UAV Network For Military Applications. In Proceedings of the 2021 Sixth International Conference on Wireless Communications, Signal Processing and Networking (WiSPNET), Chennai, India, 25–27 March 2021; pp. 122–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, N.; Wu, S.; Wang, X.; Yin, Z.; Li, C.; Chen, W.; Chen, F. AI for UAV-Assisted IoT Applications: A Comprehensive Review. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 14438–14461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejeb, A.; Abdollahi, A.; Rejeb, K.; Treiblmaier, H. Drones in agriculture: A review and bibliometric analysis. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 198, 107017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paikrao, P.; Routray, S.; Mukherjee, A.; Khan, A.R.; Vohnout, R. Consumer Personalized Gesture Recognition in UAV Based Industry 5.0 Applications. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2023, 69, 842–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azari, M.M.; Solanki, S.; Chatzinotas, S.; Kodheli, O.; Sallouha, H.; Colpaert, A.; Mendoza Montoya, J.F.; Pollin, S.; Haqiqatnejad, A.; Mostaani, A.; et al. Evolution of Non-Terrestrial Networks From 5G to 6G: A Survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2022, 24, 2633–2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, G.K.; Ozasa, M.; Nakazato, J. NFV/SDN as an Enabler for Dynamic Placement Method of mmWave Embedded UAV Access Base Stations. Network 2022, 2, 479–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turgut, E.; Gursoy, M.C. Downlink Analysis in Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) Assisted Cellular Networks with Clustered Users. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 36313–36324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ur Rahman, S.; Kim, G.H.; Cho, Y.Z.; Khan, A. Positioning of UAVs for throughput maximization in software-defined disaster area UAV communication networks. J. Commun. Netw. 2018, 20, 452–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Wang, N.; Mu, X. Iterative UAV Trajectory Optimization for Physical Layer Secure Mobile Relaying. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Cyber-Enabled Distributed Computing and Knowledge Discovery (CyberC), Zhengzhou, China, 18–20 October 2018; pp. 19–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishnoi, V.; Consul, P.; Budhiraja, I.; Gupta, S.; Kumar, N. Deep Reinforcement Learning Based Energy Consumption Minimization for Intelligent Reflecting Surfaces Assisted D2D Users Underlaying UAV Network. In Proceedings of the IEEE INFOCOM 2023—IEEE Conference on Computer Communications Workshops (INFOCOM WKSHPS), Hoboken, NJ, USA, 20–20 May 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, G.K.; Okada, T. Design of Antenna Polarization Plane for Concurrent Uplink/Downlink Drone Networks. Electronics 2023, 12, 3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DOCOMO 6G White Paper. Available online: https://www.docomo.ne.jp/english/corporate/technology/whitepaper_6g/ (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- NTT DOCOMO Technical Journal Vol. 29 No. 2 5G Evolution & Research on Transparent RIS Technology for 6G (July 2021). Available online: https://www.docomo.ne.jp/binary/pdf/corporate/technology/rd/technical_journal/bn/vol29_2/vol29_2_004jp.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Hashida, H.; Kawamoto, Y.; Kato, N. Intelligent Reflecting Surface Placement Optimization in Air-Ground Communication Networks Toward 6G. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 2020, 27, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amri, M.M. Recent Trends in the Reconfigurable Intelligent Surfaces (RIS): Active RIS to Brain-controlled RIS. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Communication, Networks and Satellite (COMNETSAT), Solo, Indonesia, 3–5 November 2022; pp. 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Mu, X.; Hou, T.; Xu, J.; Di Renzo, M.; Al-Dhahir, N. Reconfigurable Intelligent Surfaces: Principles and Opportunities. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials 2021, 23, 1546–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamzadeh, I.; Alexandropoulos, G.C.; Shlezinger, N.; Imani, M.F. A reconfigurable intelligent surface with integrated sensing capability. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1546–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Liu, R.; Li, M.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Q. Joint BS-RIS-User Association and Beamforming Design for RIS-Assisted Cellular Networks. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 72, 6113–6128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TMYTEK Redistribution of Radio Waves by XRifle RIS. Available online: https://www.tmytek.com/jp/solutions/mmW-Coverage (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Rahmatov, N.; Baek, H. RIS-carried UAV communication: Current research, challenges, and future trends. ICT Express 2023, 9, 961–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Nguyen, T.H.; Park, L. Federated Deep Learning for RIS-assisted UAV-enabled Wireless Communications. In Proceedings of the 2022 13th International Conference on Information and Communication Technology Convergence (ICTC), Jeju Island, Republic of Korea, 19–21 October 2022; pp. 831–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Wu, M.; Li, X.; Song, H.; Kumar, N. Deep Reinforcement Learning and NOMA-Based Multi-Objective RIS-Assisted IS-UAV-TNs: Trajectory Optimization and Beamforming Design. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 10197–10210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Ni, W.; Tian, H.; Eldar, Y.C.; Niyato, D. UAV-Mounted Multi-Functional RIS for Combating Eavesdropping in Wireless Networks. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 2023, 12, 1667–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yu, Y.; Li, F.; Durrani, T.S. Throughput Maximization for RIS-UAV Relaying Communications. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 19569–19574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, A.; Agrawal, N.; Singh, K.; Li, C.P.; Mumtaz, S. RIS Selection Scheme for UAV-Based Multi-RIS-Aided Multiuser Downlink Network with Imperfect and Outdated CSI. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2023, 71, 4650–4664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abualhayja’a, M.; Centeno, A.; Mohjazi, L.; Butt, M.M.; Sehier, P.; Imran, M.A. Exploiting Multi-Hop RIS-Assisted UAV Communications: Performance Analysis. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2024, 28, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Meng, F.; Zhang, J.; Hasna, M.O.; Renzo, M.D. On the Performance of RIS-Assisted Dual-Hop UAV Communication Systems. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2020, 69, 10385–10390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hilo, A.; Samir, M.; Elhattab, M.; Assi, C.; Sharafeddine, S. RIS-Assisted UAV for Timely Data Collection in IoT Networks. IEEE Syst. J. 2023, 17, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.K.; Masaracchia, A.; Sharma, V.; Poor, H.V.; Duong, T.Q. RIS-Assisted UAV Communications for IoT with Wireless Power Transfer Using Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 2022, 16, 1086–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; An, K. On the Performance of RIS-Assisted Integrated Satellite-UAV-Terrestrial Networks with Hardware Impairments and Interference. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 2022, 11, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Tang, J.; Wu, Q.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, X.; So, D.K.C.; Wong, K.K. Resource Allocation for Power Minimization in RIS-Assisted Multi-UAV Networks with NOMA. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2023, 71, 6662–6676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Song, Z.; Hou, T.; Yu, W.; Wang, J.; Sun, X. Joint Optimization of Resource Allocation, Phase Shift, and UAV Trajectory for Energy-Efficient RIS-Assisted UAV-Enabled MEC Systems. IEEE Trans. Green Commun. Netw. 2023, 7, 1778–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, A.B.M.; Wan, X.; Elhassan, M.A.M.; Muthanna, M.S.A.; Muthanna, A.; Kumar, N.; Guizani, M. Intelligent and Robust UAV-Aided Multiuser RIS Communication Technique with Jittering UAV and Imperfect Hardware Constraints. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 72, 10737–10753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobile Spatial Statistics. Available online: https://mobaku.jp/ (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Al-Hourani, A.; Kandeepan, S.; Jamalipour, A. Modeling air-to-ground path loss for low altitude platforms in urban environments. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Global Communications Conference, Austin, TX, USA, 8–12 December 2014; pp. 2898–2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rappaport, T.S.; Sun, S.; Mayzus, R.; Zhao, H.; Azar, Y.; Wang, K.; Wong, G.N.; Schulz, J.K.; Samimi, M.; Gutierrez, F. Millimeter Wave Mobile Communications for 5G Cellular: It Will Work! IEEE Access 2013, 1, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasawa, Y. Fundamentals of Wave Propagation for Digital Mobile Communications; Corona Publishing Co., Ltd.: Tokyo, Japan, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- PLATEU. Available online: https://www.mlit.go.jp/plateau/ (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Geraci, G.; Garcia-Rodriguez, A.; Azari, M.M.; Lozano, A.; Mezzavilla, M.; Chatzinotas, S.; Chen, Y.; Rangan, S.; Renzo, M.D. What Will the Future of UAV Cellular Communications Be? A Flight from 5G to 6G. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials 2022, 24, 1304–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 3GPP TS 38.101-2 V15.10.0 (2020-06). Available online: https://www.etsi.org/deliver/etsi_tr/138900_138999/138900/14.02.00_60/tr_138900v140200p.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, Consideration of Frequency Sharing Related to 5G Introduction in 3.7 GHz Band, 4.5 GHz Band, and 28 GHz Band. Available online: https://www.soumu.go.jp/main_content/000527890.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Toshihiro, S.; Gia Khanh, T. Study on the construction of mmWave based IAB-UAV networks. In Proceedings of the Asian Internet Engineering Conference (AINTEC), Hiroshima, Japan, 19–21 December 2022. [Google Scholar]

| Aspect | Ref. | Main Contribution |

|---|---|---|

| IRS only or integrated to BS | [18,19,20] | Introduces what IRS is, its recent trends and future opportunities. |

| [21] | Jointly optimizes BS–RIS–user association and beamforming design for cellular networks. | |

| [16,22] | Product commercialization efforts. Demonstration tests. | |

| IRS on UAV | [23] | Compiles current research, challenges, and future trends on RIS-carried UAVs. |

| [24,25] | Applies deep learning for RIS-assisted UAVs. | |

| [26] | Designs a new multifunctional RIS architecture. | |

| [27] | Jointly optimizes the UAV trajectory, RIS passive beamforming, and source power allocation. | |

| IRS collaborated with UAV-BS | [28] | Proposes RIS selection scheme for UAV-based multi-RIS-aided multiuser. |

| [29,30] | Presents a framework to examine the performance of multihop RIS-assisted UAV communication. | |

| [31,32] | Applies for IoT networks like timely data collection and wireless power transfer. | |

| [33] | Verifies satellite–UAV–terrestrial networks under the consideration of hardware impairments and interference. | |

| [34,35,36] | Jointly optimizes RIS phase shift and UAV position to improve power consumption. |

| Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Carrier Frequency f | 28 GHz |

| Bandwidth | 100 MHz [43] |

| Environment | Dense Urban, 139.6864° E ~139.7004° E, |

| 35.6829° N~35.6943° N, | |

| approx. 1.2 km × 1.2 km | |

| UAV, UE area | 139.688° E~139.7° E, |

| 35.684° N~35.692° N, | |

| approx. 1.1 km × 0.9 km | |

| UE height | 1.2 m |

| IRS height | 30 m |

| Range of incident and reflection angle at IRS | 15~75° (vertically, horizontally) |

| Neiboring BS position | (139.68676° E, 35.69350° N, 209 m) |

| Minimum UAV height | 50 m |

| Maximum UAV height | 70 m |

| The number of UAVs | 1 |

| The number of IRSs M | 1000 (4 × 250) |

| The number of UEs N | 13,349 |

| The number of hotspots | 0~3 |

| The ratio of UEs inside hotspots | 30~70% |

| Hotspots radius | 10~20% of area length |

| EIRP (Trans. power + Antenna gain) | 68 dBm [44] |

| Transmit output power | 45 dBm [44] |

| Tx antenna gain | 23 dBi |

| UE Rx antenna gain | 0 dBi |

| Noise density | −174 dBm/Hz |

| Additional loss by LoS | 3.5 dB [38] |

| Additional loss by NLoS | 47 dB [38] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yamamoto, S.; Nakazato, J.; Tran, G.K. Multi-IRS-Assisted mmWave UAV-BS Network for Coverage Extension. Sensors 2024, 24, 2006. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24062006

Yamamoto S, Nakazato J, Tran GK. Multi-IRS-Assisted mmWave UAV-BS Network for Coverage Extension. Sensors. 2024; 24(6):2006. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24062006

Chicago/Turabian StyleYamamoto, Sota, Jin Nakazato, and Gia Khanh Tran. 2024. "Multi-IRS-Assisted mmWave UAV-BS Network for Coverage Extension" Sensors 24, no. 6: 2006. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24062006

APA StyleYamamoto, S., Nakazato, J., & Tran, G. K. (2024). Multi-IRS-Assisted mmWave UAV-BS Network for Coverage Extension. Sensors, 24(6), 2006. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24062006