Abstract

Self-powered biomedical devices, which are the new vision of Internet Of Things (IOT) healthcare, are facing many technical and application challenges. Many research works have reported biomedical devices and self-powered applications for healthcare, along with various strategies to improve the monitoring time of self-powered devices or to eliminate the dependence on electrochemical batteries. However, none of these works have especially assessed the development and application of healthcare devices in an African context. This article provides a comprehensive review of self-powered devices in the biomedical research field, introduces their applications for healthcare, evaluates their status in Africa by providing a thorough review of existing biomedical device initiatives and available financial and scientific cooperation institutions in Africa for the biomedical research field, and highlights general challenges for implementing self-powered biomedical devices and particular challenges related to developing countries. The future perspectives of the aforementioned research field are provided, as well as an architecture for improving this research field in developing countries.

1. Introduction and Theoretical Background

Energy harvesting (EH) technologies, the future of wearable devices, provide promising solutions to overcome the short lifetimes of wearable devices. In recent decades, modern wearable technologies, including biosensors, wearable fitness trackers (WFTs), smart health watches, wearable electrocardiogram (ECG) monitors, wearable blood pressure monitors, continuous glucose meters, etc., have widely impacted our lifestyle. According to GlobalData [1], the wearable technology market was estimated to be approximately USD 46 billion in 2022 and is forecast to grow to over USD 100 billion by 2027, with a compound annual growth (CAGR) of 17%.

The key factors driving the wearable technology market growth include the increasing popularity of the Internet of Things (IoT) and connected devices, device miniaturization for wearability, increasing demand for wearable devices for monitoring and tracking health vital signs, and rapid advancements in sensor technology.

Self-powered technology means that a device can sustain its own operation by harvesting power from its working environment without an external power supply. Other definitions of self-powered devices from different organizations are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Definitions of self-powered devices.

Given the significant, widespread applications of the aforementioned biomedical devices, many concerns have been raised about the weight and the availability of power sources for wearable devices. In fact, batteries developed for wearable applications have contributed to the achievement of successful deployment in healthcare [3,4]. The implanted devices are meant to continually assess patient health on a predetermined scheme, which constrains the designers of biomedical applications, requiring long-life batteries to be chosen to avoid frequent replacement. In addition, batteries must have a volumetric high energy density to enable the design of miniaturized implants and avoid discomfort and harm to patients [5,6]. In an attempt to overcome the limitations of traditional batteries in wearable applications, there have been undertakings for developing wearable devices with non-exogenous power requirements. Electrochemical cells and various transduction techniques have been introduced as implantable power sources [7,8]. Their short shelf life, the voltage and current instability, and the presence of hydrogen gas limit their application. Devices such as piezoelectric materials have been introduced to continuously recharge the batteries of pacemakers by the direct conversion of heartbeats to electric energy. Even though piezoelectric transduction techniques have contributed to the achievement of effective self-powered pacemakers, they are also an invasive solution. In fact, in comparison with traditional pacemakers, requiring frequent surgery to charge the battery of the device, self-powered pacemakers require surgery after a long period only for replacing the battery of the implanted device [9]. Hanjun Ryu et al., have developed a commercial self-rechargeable cardiac pacemaker system with an implanted inertia-driven triboelectric nanogenerator (I-TENG) based on body motion and gravity, which has the potential to extend the device operating time and reduce risks of regular surgery [10]. Radio imaging has been used for many years to evaluate bone healing after surgery. The side effect of radio imaging is the exposure of patients to radiation, which damages deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) in patient cells and causes cancer in the long run [11,12]. In order to overcome the shortcomings of radio imaging, a reliable solution was introduced by Amir Alavi et al. The research team designed a smart, self-aware implant for tracking spinal fusion for bone healing. The meta-triboelectric material is inserted into inter-vertebral discs, and during bone healing, the load applied on the discs reduces gradually. The applied load on the meta-triboelectric material generates electric energy, which is used to assess bone healing [13].

The research and development of self-powered biomedical devices in Africa is still at its early stage. Further development is provided in Section 3, along with suggestions for improving the research field. However, considerable achievements by African developers for local healthcare have been reported. The CARDIOPAD device developed by Cameroonian Arthur Zang enables the monitoring of heartbeat rates and forwards data to a remote scientist or cardiology hospital for diagnosis [14]. Tiam Kapen P. et al., have reported a multi-function neonatal incubator for low- and middle-income countries [15]. Many other biomedical devices that can be used in Africa healthcare have been developed, such as a blood glucose meter in Africa for Africans [16]; a smart, low-cost, non-invasive blood glucose monitoring device in South Africa [17], a free play fetal heart rate monitor [18], the SINAPI chest drain [19], etc.

The potential energy sources for deployable devices, such as solar energy, chemical energy, electromechanical energy and thermal energy, are under intensive investigation. Electromagnetic energy is derived from the motion of a coil trough a stationary field [20,21], triboelectricity is generated from friction between two different materials [10], and piezoelectric energy results from the deformation of a piezoelectric material [22,23]. The above transducers are capable of converting primary energy sources available in human environments to electric energy. Therefore, triboelectric, electromagnetic and piezoelectric energy is suitable for self-powered biomedical devices due to the possibility to miniaturize their design and achieve a volumetric high energy density.

Given the promising opportunities of bio-mechanical energy harvesting for self-powered devices in global healthcare, the leading questions for this review are:

- ▪

- How can free and available energies in the human environment be turned into a power source for embedded healthcare devices?

- ▪

- What are the challenges and opportunities?

- ▪

- Are African countries ready for facing the challenges, or are there any findings in developing countries in similar topics for local healthcare?

The ideal way to obtain a clear answer to these questions is by providing a thorough review of self-powered biomedical devices developed so far for healthcare, highlighting the challenges and opportunities for their application in an African context and demonstrating some achievements in similar topics in Africa for local healthcare. This will be achieved by following the research string provided in [24], which conforms with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines.

2. Review Methodology

A research framework is provided for designing, conducting and analyzing review articles systematically and rigorously. It is helpful for achieving review consistency.

2.1. Systematic Literature Review (SLR)

The systematic literature review provided in [24] has been shortened into five (05) main steps. Some steps are merged into others to reduce the length of the review.

2.1.1. Purpose of the Literature Review

The purpose of this literature review is to highlight the achievements of bio-mechanical energy harvesting for self-powered healthcare devices, outline the current state of progress of some African countries in the aforementioned research field by presenting biomedical research and devices initiatives developed so far for solving local health issues, point out the challenges and opportunities, and provide objective advice to determine the implementation challenges of biomedical research in developing countries.

2.1.2. Protocol and Training

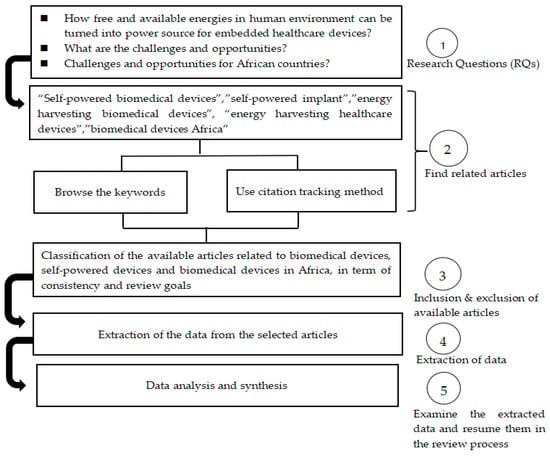

A review protocol is designed in Figure 1 for ensuring the review consistency and answering the research questions (RQs).

Figure 1.

Systematic review protocol followed for answering the research questions (RQs).

2.1.3. Screening of the Existing Literature

The following search strings were defined “self-powered biomedical devices”, “self-powered implant”, “energy-harvesting biomedical devices”, “energy-harvesting healthcare devices”, and “biomedical devices Africa”. Besides the predefined search strings, the pearl growing or citation tracking method was used in order not to rely only on a protocol-driven strategy and miss other important resources.

2.1.4. Extraction and Appraisal of Data Quality

The criteria considered for the selection of studies include:

- ▪

- Articles written in English and published within eight recent years (2015–2023);

- ▪

- Applied research and technology development articles;

- ▪

- Articles related to biomedical energy harvesting and healthcare devices.

Table 2.

Contribution of biomedical energy harvesting TO self-powered healthcare devices.

Table 3.

Comparison of biomedical devices powered by Nanogenerators.

The remaining articles were excluded.

Some important articles might have been excluded because their publication date was out of the selected review range or because their content does not include both aspects of energy harvesting and biomedical devices. In addition, articles including experimental studies were the priority of this review.

2.1.5. Study Synthesis

Following the research questions introduced earlier, and based on the review articles found during systematic research review, it is clear that the contribution of biomedical energy harvesting for self-powered devices is undeniable in human healthcare. Evidence includes invasive self-powered biomedical devices, summarized in Figure 2, and non-invasive self-powered devices, summarized in Figure 3.

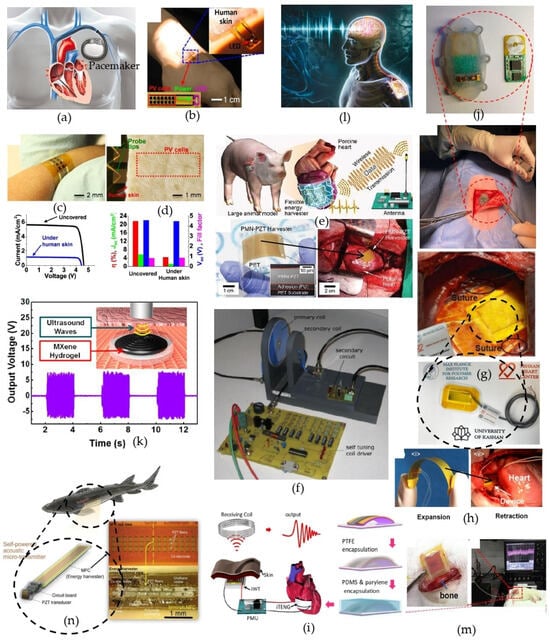

Figure 2.

Illustration of the potential applications of implanted PV devices for powering implantable electronics such as pacemakers (a). The feasibility of the study is shown by lighting LEDs with power from integrated PV devices under human hand dorsum skin (b). Optical image of IPV device bent on a human arm (c), image of fixed human skin covering IPV cells (d) [25]. In vivo self-powered cardiac sensor for estimating blood pressure and velocity of blood flow (e) [26]. Self-tuning inductive powering system for biomedical implants (f) [27]. Self-powered cardiac pacemaker with a piezoelectric polymer nanogenerator implant (g) [28]. Implantable and self-powered blood pressure monitoring based on a piezoelectric thin film (h) [29]. Schematic diagram of a self-powered wireless transmission system based on an implanted triboelectric nanogenerator (iWT: implantable Wireless Transmitter; PMU: Power Management Unit) (i) [30]. A battery-less implantable glucose sensor based on electrical impedance spectroscopy; sensor implantation on the pig for experimentation (j) [31]. Biocompatible battery for medical implant charged via ultrasound (k) [32]. Self-powered deep brain stimulation via a flexible PIMNT energy harvester (l) [33]. Self-powered implantable electrical stimulator for osteoblast proliferation and differentiation (m) [34]. An implantable biomechanical energy harvester for animal monitoring devices (n) [35]. Reproduced with permission from [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35].

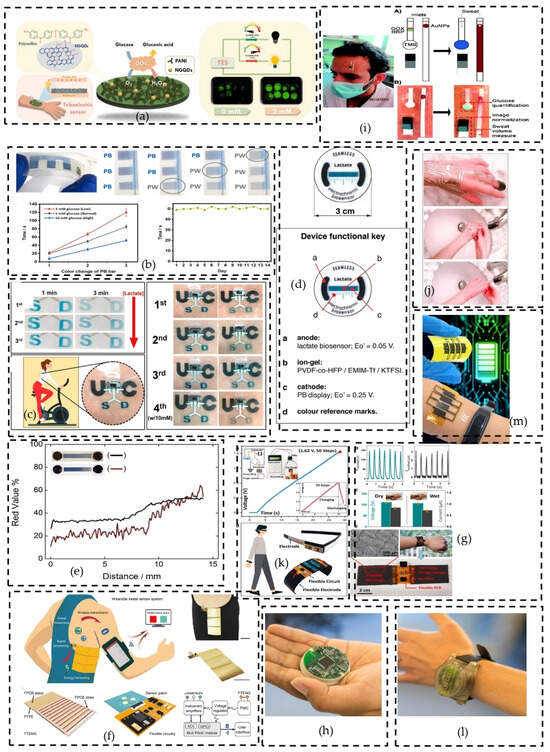

Figure 3.

Schematic illustration of the potential applications of non-invasive, wearable, self-powered devices. Non-invasive glucose meters (a–e) [36,37,38,39,40]. Wireless, battery-free wearable sweat sensor powered by human motion, along with the schematic illustrating human motion energy harvesting, signal processing, microfluidic-based sweat biosensing, and Bluetooth-based wireless data transmission to a mobile user interface for real-time health status tracking (f) [41]. Wearable applications of body-integrated self-powered systems (BISSs) (g) [42]. Behavioral and environmental sensing and intervention (BESI), which combines environmental sensors placed around the homes of dementia patients for detecting the early stage of agitation (h) [43]. Schematic representation of glucose level detection in human sweet (i) [44]. Wearable circuits sintered at room temperature directly on the skin surface for health monitoring (j) [45]. Diagram of flexible, wearable, self-powered electronics based on a body-integrated self-powered system (BISS) (k) [42]. Technology-Enabled Medical Precision Observation (TEMPO): a wristwatch-sized device that can be worn on various parts of the body for monitoring user’s agitation during motion and detect early cerebral palsy, Parkinson’s disease and multiple sclerosis (l) [43]. The device was developed by the University of Virginia. Stretchable micro-supercapacitors which harvest energy from human breathing and motion for self-powering wearable devices (m) [46]. Reproduced with permission from [36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46].

- ▪

- Invasive self-powered biomedical devices.

Biomedical electronics powered by solar cells were developed by Song K. et al. [25]. Figure 2a–d illustrate the potential applications of implanted PV devices for powering biomedical implants such as pacemakers. A miniaturized implanted photovoltaic cell (IPV) is inserted under small top layer of human skin (0.68 mm thickness) for harvesting electric energy and powering biomedical implants such as pacemakers, etc., which enables avoiding regular surgery for replacing the batteries of biomedical implants powered by traditional batteries.

Various harvesting strategies have been implemented by researchers for self-powered implantable biomedical and tracking devices, including an in vivo self-powered cardiac sensor for estimating blood pressure and the velocity of blood flow [26], a self-tuning inductive powering system [27], a bio-compatible, flexible piezoelectric polymer-based nanogenerator for powering cardiac pacemakers (PNG) [28], and piezoelectric thin film (PETF)-based energy harvesting [29], which harvests energy from the axial stress of artery to measure blood pressure. An in vivo self-powered cardiac sensor was developed for estimating blood pressure and the velocity of blood flow [30]. A battery-less implantable glucose sensor based on electrical impedance spectroscopy was developed for continuous monitoring of blood glucose concentrations [31]. An ultrasound-driven two-dimensional Ti3C2Tx MXene hydrogel generator, which harvests ambient vibrations coupled with triboelectrification, for powering implanted generators was proposed [32]. Self-powered deep brain stimulation via a flexible point energy harvester, which has the potential to generate electricity from cyclic deformations of the heart, lungs, muscles, and joints, was proposed to supply electric energy to a deep brain stimulation system and induce behavioral changes in a living body [33]. A self-powered flexible and implantable electrical stimulator was developed, which consists of a triboelectric nanogenerator (TENG) and a flexible interdigitated electrode for osteoblast proliferation and differentiation [34]. A Macro Fiber Composite (MFC) piezoelectric beam for harvesting bending movement from fishes for powering tracking devices was also developed [35], among others.

- ▪

- Non-invasive self-powered biomedical devices.

Besides implantable devices, non-invasive wearable biomedical energy harvesting systems for biosensors have drawn the attention of many researchers. Some applications include non-invasive wearable self-powered triboelectric sensors (TESs) for simultaneous physiological monitoring developed by Yu-Hsin Chang et al., which enables the assessment of glucose concentrations in human sweat. The triboelectric sensing layer is made of nanocomposite N-doped graphene quantum-dot-decorated polyaniline (NGQDs/PANI)/Glucose oxidase enzine (GOx) for non-invasive monitoring of glucose levels in human sweat, as shown in Figure 3a [36]. An electric voltage is generated due to the coupling effect of enzymatic reaction and triboelectrification. The glucose concentration is proportional to the generated voltage. LEDs are used as an indicator of glucose concentrations. Figure 3b shows a flexible, disposable and self-powered glucose biosensor visible to the naked eye developed by J. Lee et al. [37], in which the theory of enzymatic biofuel cells is adopted for self-power generation. The polarization of the glucose biosensor enables the Prussian blue (PB) bar in Figure 3b to automatically change color, which is used to indicate three levels of glucose, including low, normal and high glucose concentrations, in human sweat. Many other non-invasive self-powered biosensors for glucose level assessments have been developed based on the same principle of enzymatic reactions, such as a resettable sweat-powered wearable electrochromic biosensor (Figure 3c) by M.C. Hartel et al. [38], a self-powered skin-patch electrochromic biosensor (Figure 3d) by S. Santiago-Malagon et al. [39], and fully printed and silicon-free self-powered electrochromic biosensors for naked eye quantification (Figure 3e) developed by M. Aller-Pellitero et al. [40].

Non-invasive glucose detection strategies have shown the efficiency of glucose meters without an external power supply.

- ▪

- Comparison of biomedical devices powered by nanogenerators

A comparison of self-powered biomedical devices is provided in Table 3. Self-powered systems harvesting energy from photovoltaic solar cells can achieve the maximum power density. They are best suited to self-powered non-invasive biomedical applications, since photovoltaic solar cells can be exposed to sunlight. However, for invasive biomedical self-powered applications, triboelectric energy generation enables harvesting the maximum power for the smallest design surface.

3. Challenges, Opportunities, Status and Capability of Self-Powered Biomedical Devices

3.1. Challenges of Self-Powered Biomedical Devices

Challenges for implementing self-powered biomedical devices in an Africa context are categorized into general challenges for self-powered bio-electronics and specific challenges for developing countries.

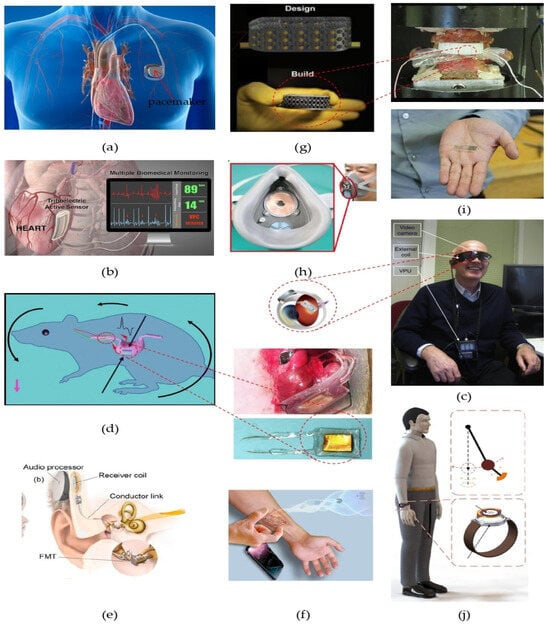

Self-powered healthcare devices face general challenges such as design constraints, the comfort and safety of patients [71]. In fact, self-powered biomedical devices aim to achieve compatibility with living tissues and organs, in vivo stability, design miniaturization and low power consumption. Figure 4 shows several examples of biomedical devices for in vivo and non-invasive healthcare applications to illustrate the complexity of the devices.

Figure 4.

Examples of miniaturized biomedical devices and self-powered implants. Self-rechargeable cardiac pacemaker (a) [72]; troboelectric active sensor (b) [72,73]; retinal prosthesis system, a variable external unit with camera attached to it (c) [74]; self-powered vagus nerve stimulator device for effective weight control (d) [75]; an ultrasonic energy harvester in use in a cochlear hearing aid (e) [76]; energy harvesting from radio waves for powering wearable devices (f) [77]; self-powered metamaterial implant for the detection of bone healing progress (g) [13]; self-powered electrostatic adsorption face mask based on a triboelectric nanogenerator (h) [78]; self-powered implantable device for stimulating fast bone healing, which then disappears without a trace (i); self-powered smart watch and wristband enabled by an embedded generator (j) [79]. Reproduced with permission from [13,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79].

- ▪

- Challenge of miniaturization: The design aims to miniaturize the size and achieve the highest output power performance, which are contradictory;

- ▪

- Flexibility: In vivo self-powered systems need the highest flexibility in order to not harm patients;

- ▪

- Biocompatibility: Biomedical devices must meet the appropriate biological requirements for a biomaterials;

- ▪

- Long-term stability: Biomedical devices must be able to operate for a long period, especially for in vivo applications, in order to avoid regular surgery.

Specific challenges for implementing self-powered devices in developing countries include insufficient digital literacy training, infrastructure, local Artificial Intelligence (AI) talents, data sets and government support.

- ▪

- Insufficient Digital literacy training and infrastructures.

Enduring lessons from the COVID-19 crisis have shown how sustainable development in global healthcare can only be achieved when no one is left behind. They have shown the importance of the availability of digital infrastructures for remote healthcare, efficient management of quarantined patients, etc.

Compared to other continents, digital penetration in Africa is still low in spite of remarkable achievements by young talent [14,15,16,17,18,19,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56] and efforts from governments and non-profit organizations (NPOs).

Barriers for digital literacy growth in Africa include inability to afford training and experimental infrastructure and insufficient information (many IoT developers are unaware of recent trends in biomedical devices and their contribution in healthcare). Political instabilities, which lead to armed conflicts and inaccessibility to education in some countries are also a barrier. Electricity and internet supplies are fragmented in many rural areas in Africa. According to a World Bank report, less than 51% of the rural area population in sub-Sahara Africa had access to electricity in 2021 [80].

- ▪

- Data sets and government support.

Another major issue faced by the development of biomedical devices in Africa is the lack of accessible data to African AI talents and the relevance of the available data to local problems. In fact, machine learning applications, such as voice and pattern recognition, rely on a large amount of data for testing algorithms. Available data are collected from patients with different ethnicities and from different environments. Inappropriate data or their misinterpretation might be harmful, especially when it comes to healthcare applications.

Artificial Intelligence (AI), especially in the biomedical research field, faces the common problem of insufficient support from African governments as well. In the European Union and North America, governments have set rules governing the use and application of Artificial Intelligence for personal and commercial uses. Sub-Saharan African countries have been classified as the worst-performing region in the 2023 Government AI Readiness Index, which emphasizes the serious challenges to AI adoption in Africa.

Despite these barriers, there have been significant improvements in some countries such as Rwanda, Senegal and Benin in setting a new framework for new national AI strategies and announcing these forthcoming strategies. Mauritius remains the only country in the region with an AI strategy over the past 5 years [81].

3.2. Opportunities for African Countries

The World Health Organization (WHO) has reported that cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are the first cause of death globally. Out of 17 million premature deaths (under the age of 70) due to non-communicable diseases in 2015, 82% were from low- and middle-income countries and 37% were caused by CVDs [82]. Sufficient support for new infrastructures, data sets and AI regulations from governments, as mentioned in the previous section, can enable the development of self-powered microelectronic devices relevant to healthcare in an African context for Africans.

Self-powered devices show high potential in energy harvesting, sensing, healthcare and biomedical implants and are becoming a new area of electronics devices in IOT applications. Self-powered devices improve the existing systems by enabling the device to supply its own power from energy available in its working environment. With self-powered biomedical devices, vital sign parameters can be continuously monitored and biomedical implants can be continuously powered, which reduce the risk of regular surgery. Self-powered systems help to achieve remote healthcare without exogenous power requirements. They are a great opportunity for developing countries since there is a big challenge regarding a continuous power supply and a lack of experienced scientists.

Self-powered technology can enable the restoration of a sense of touch to injured or disabled patients (Figure 5a); they are great opportunity for medical care in inaccessible locations, with applications such as intravenous drug delivery by nanobots (Figure 5b), animal tracking devices (Figure 5c), monitoring and detection of early stage of non-communicable diseases such as CADs, diabetes, Alzheimer’s, etc., and continuous monitoring of remote patients living with critical health conditions (Figure 5d).

Figure 5.

Future directions of self-powered biomedical devices in Africa: restoring the sense of touch to an injured finger (a) [83], intravenous drug delivery (b) [84], a self-powered GPS tracker for cattle (c) [85], and an e-health watch for temperature and heartbeat rate monitoring (d) [86].

3.3. Status of Self-Powered Biomedical Devices in Africa

Biomedical research has shown its capability for stimulating the development of healthcare and biomedical infrastructures. In this section, we discuss the research status of self-powered devices in an African context and how research funding and scientific cooperation can provide opportunities to pursue this research area with regard to the populations in rural areas and developing countries.

The biomedical research field has reported significant achievements for healthcare devices in low- and middle-income countries, especially in African countries with the development of biomedical devices such as A blood glucose meter in Africa for Africans [16], a low-cost, non-invasive smart glucose monitoring device in South Africa [17], a free play fetal heart rate monitor [18], the SINAPI chest drain [19], a biomedical smart jacket [52], a vital sign monitor for expectant mothers [53], electronically controlled gravity feed infusion [54], the CARDIOPAD device for monitoring heart rate and forwarding data to remote scientist [14], a multi-function neonatal incubator for low- and middle-income countries [15], etc.

However, the research and development of self-powered devices is still at its stage of infancy. The reason behind this is that many funding institutions have restricted their support for solving specific health issues that affect the majority of a local population.

There are many financial institutions such as the African engineering award, the AFD (French Development Agency), the United Nation’s Development Program, the African Development Bank, Team Europe Initiative, etc.

Besides financial institutions, collaborative programs for biomedical research have greatly contributed to this research field, such as the U.S.–South Africa Program for Collaborative Biomedical Research (R01), the World Health Organization’s EU–Africa partnership, etc., to boost biomedical research. However, the biomedical research field in many low-income countries still faces serious challenges such as limited infrastructures and inaccessibility to biomedical research funding. In fact, the available funds for biomedical research aim to support only existing projects.

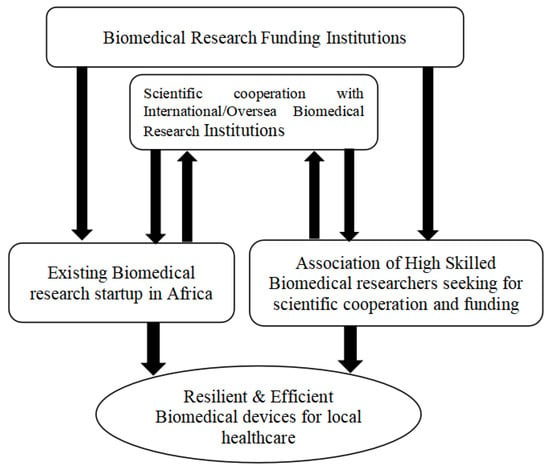

Scientific cooperation in the biomedical research field is restricted to biomedical research startups as well. Many biomedical research projects led by highly skilled researchers often fail due to lack of funding. Extending the research cooperation and funding to highly skilled graduate biomedical engineers who have no sufficient funds for realize their experimental prototype and start up a biomedical engineering company will help to lift the barrier in biomedical engineering research. Figure 6. illustrates the architecture of scientific cooperation and funding in biomedical research suitable for Africa and other middle-income country contexts.

Figure 6.

Architecture of scientific cooperation and funding in biomedical research suitable for low-and middle-income countries.

For this cooperation and funding, both existing biomedical research startups and other highly skilled biomedical researcher groups can benefit from biomedical research funding and scientific cooperation with international research institutions.

4. Conclusions

This is the end of the current review which aimed to introduce the applications of self-powered biomedical devices, assess the status of the biomedical engineering research field in Africa and identify the challenges and opportunities. Many application areas of self-powered biomedical devices have been presented, including self-powered pacemakers, self-powered monitoring devices, non-invasive self-powered glucose meters, etc. The research status of biomedical devices in Africa has also been reported, including the existing achievements for biomedical devices and available scientific cooperation and funding for supporting biomedical research in Africa. However, some challenges to the development of biomedical research in Africa have been highlighted, including insufficient digital literacy training, absence or incompatibility of data for testing biomedical device algorithms, inaccessibility of infrastructures, restricted scientific cooperation and funding, absence of AI regulations, lack of government support and insufficient AI talent. An architecture has been provided for the better management of scientific cooperation and funding for biomedical engineering research suitable in an African context, which can enable the achievement of resilient and efficient biomedical devices for healthcare in Africa.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.N.O. and W.W.; methodology, D.N.O.; software, D.N.O.; validation, C.L. and B.D.; data curation, Z.W.; writing—original draft preparation, D.N.O.; writing—review and editing, W.W.; visualization, D.N.O.; supervision, W.W.; project administration, W.W.; funding acquisition, D.N.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by China Scholarship Council (CSC), grant number: 2019GXZ012914.

Acknowledgments

Djakou Nekui Olivier would like to express his deepest gratitude to Kakong Marie Eleanor and Taffo Nekui Raphael for their understanding and support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Global Data. Fitness Watches May Soon Be Able to Monitor much More Than Weight and Heart Health, as Global Data Identifies 160 Ongoing Clinical Trials for Medical Wearables. Available online: https://www.globaldata.com/media/medical-devices/fitness-watches-may-soon-able-monitor-much-weight-heart-health-globaldata-identifies-160-ongoing-clinical-trials-medical-wearables/ (accessed on 6 July 2023).

- Cambridge University & Press Assessment. Self-Powered. 2023. Available online: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/self-powered (accessed on 8 July 2023).

- Force Technology. ASIC Power Management for Self-Powered IoT Sensors. Available online: https://forcetechnology.com/en/articles/asic-power-management-self-powered-iot-sensors (accessed on 8 July 2023).

- Owens, B.B.; Salkind, A.J. Key Events in the Evolution of Implantable Pacemaker Batteries. In Batteries for Implantable Biomedical Devices; Owens, B.B., Ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnhart, P.W.; Fischell, R.E.; Lewis, K.B.; Radford, W.E. A fixed-rate rechargeable cardiac pacemaker. Appl. Phys. Lab. Techn. Dig. 1970, 9, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Bock, D.C.; Marschilok, A.C.; Takeuchi, K.J.; Takeuchi, E.S. Batteries used to Power Implantable Biomedical Devices. Electrochim. Acta 2012, 84, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holleck, G.L. Rechargeable Electrochemical Cells as Implantable Power Sources. In Batteries for Implantable Biomedical Devices; Owens, B.B., Ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, R.C.; Mahbub, I. Wearable self-powered biosensors. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2020, 19, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamia, M.A.; Inman, D.J. Powering Pacemakers from Heartbeat Vibrations using Linear and Non-linear Energy Harvesters. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012, 100, 042901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, H.; Park, H.; Kim, M.K.; Kim, B.; Myoung, H.S.; Kim, T.Y.; Yoon, H.-J.; Kwak, S.S.; Kim, J.; Hwang, T.H.; et al. Self-rechargeable cardiac pacemaker system with triboelectric nanogenerators. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, J.S.; Kazam, J.J.; Fufa, D.; Bartolotta, R.J. Radiologic evaluation of fracture healing. Skeletal Radiol. 2019, 48, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havard Health Publishing. Radiation Risk from Medical Imaging. Available online: https://www.health.harvard.edu/cancer/radiation-risk-from-medical-imaging (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Barri, K.; Zhang, Q.; Swink, I.; Aucie, Y.; Holmberg, K.; Sauber, R.; Altman, D.T.; Cheng, B.C.; Wang, Z.L.; Alavi, A.H. Patient-Specific Self-Powered Metamaterial Implants for Detecting Bone Healing Progress. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2203533. [Google Scholar]

- Himore Medical. Cardio Pad Kit. Available online: https://himore-medical.com (accessed on 29 August 2023).

- Pascalin, T.K.; Mohamadou, Y.; Momo, F.; Jauspin, D.K.; Francois de paul, M.K. A multi-function neonatal incubator for low-income countries: Implementation and ab initio social impact. Med. Eng. Phys. 2020, 77, 114–117. [Google Scholar]

- Zubair, A.R.; Adebayo, C.O.; Ebere-Dinnie, E.U.; Coker, A.O. Development of Biomedical Devices in Africa for Africa: A Blood Glucose Meter. Int. J. Electr. Electron. Sci. 2015, 2, 102–108. [Google Scholar]

- Daniyan, I.; Ikuponiyi, S.; Daniyan, L.; Uchegbu, I.D.; Mpofu, K. Development of a Smart Glucose Monitoring Device. Procedia CIRP 2022, 110, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinapi Biomedical. Freeplay Fetal Heart Rate Monitor. Available online: https://designobserver.com/feature/freeplay-fetal-heart-rate-monitor/10927 (accessed on 29 August 2023).

- SINAPI Biomedical/Chest Drainage. Available online: https://sinapibiomedical.com/products/chest-drainage/ (accessed on 29 August 2023).

- Anjum, M.U.; Fida, A.; Ahmad, I.; Iftikhar, A. A broadband electromagnetic type energy harvester for smart sensor devices in biomedical applications. Sens. Actuators A 2018, 277, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niroomand, M.; Foroughi, H.R. A rotary electromagnetic microgenerator for energy harvesting from human motions. J. Appl. Res. Technol. 2016, 14, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faizan, A.A. Piezoelectric energy harvesters for biomedical applications. Nano Energy 2019, 57, 879–902. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.; Zhang, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Wu, H.; Qin, W.; Liao, Y.; Yu, Q.; Cheng, H. Stretchable piezoelectric energy harvesters and self-powered sensors for wearable and implantable devices. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020, 168, 112569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okoli, C. A Guide to Conducting a Standalone Systematic Literature Review. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2015, 37, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Han, J.H.; Yang, H.C.; Nam, K.I.; Lee, J. Generation of electrical power under human skin by subdermal solar cell arrays for implantable bioelectronic devices. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 92, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Shin, H.J.; Lee, H.; Jeong, C.K.; Park, H.; Hwang, G.T.; Lee, H.-Y.; Joe, D.J.; Han, J.H.; Lee, S.H.; et al. In Vivo Sel-powered Wireless Transmission Using Biocompatible Flexible Energy Harvesters. Adv. Funct. Mater 2017, 27, 1700341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carta, R.; Thone, J.; Gosset, G.; Cogels, G.; Flandre, D.; Puers, R. A Self-Tuning Inductive Powering System for Biomedical Implants. Procedia Eng. 2011, 25, 1585–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimi, S.; Golabchi, A.; Nekookar, A.; Rabbani, S.; Amiri, M.H.; Asadi, K.; Abolhasani, M.M. Self-powered cardiac pacemaker by piezoelectric polymer nanogenerator implant. Nano Energy 2021, 83, 105781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Xue, X.; Ma, Y.; Han, M.; Zhang, W.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, H.-X. Implantable and self-powered blood pressure monitoring based on a piezoelectric thinfilm: Simulated, in vitro and in vivo studies. Nano Energy 2016, 22, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Zhang, H.; Shi, B.; Xue, X.; Liu, Z.; Jin, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zou, Y.; Wang, X.; An, Z.; et al. In Vivo Self-powered Cardiac Monitoring via Implantable Triboelectric Nanogenerator. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 6510–6518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ollmar, S.; Schrunder, A.F.; Birgersson, U.; Kristoffersson, T.; Rusu, A.; Thorsson, E.; Hedenqvist, P.; Manell, E.; Rydén, A.; Jensen-Waern, M.; et al. A battery-less implantable glucose sensor based on electrical impedance spectroscopy. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 18122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.H.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Jiang, Q.; Kim, H.; Alkenawi, A.A.; Alshareef, H.N. Ultrasound-Driven Two-Dimentional Ti3C2Tx MXene Hydrogel Generator. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 3199–3207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, G.-T.; Kim, Y.; Lee, J.-H.; Oh, S.; Jeong, C.K.; Park, D.Y.; Ryu, J.; Kwon, H.; Lee, S.-G.; Joung, B.; et al. Self-powered deep brain stimulation via flexible point energy harvester. Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 2677–2684. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, J.; Shi, R.; Liu, Z.; Ouyang, H.; Yu, M.; Zhao, C.; Zou, Y.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z. Self-powered implantable electrical stimulator for osteoblasts’ proliferation and differentiation. Nano Energy 2019, 59, 705–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Lu, J.; Myjak, M.J.; Liss, S.A.; Brown, R.S.; Tian, C.; Deng, Z.D. An Implantable Biomedical Energy Harvester for Animal Monitoring Devices. Nano Energy 2022, 98, 108505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-H.; Chang, C.-C.; Chang, L.-Y.; Wang, P.-C.; Kanokpaka, P.; Yeh, M.-H. Self-powered triboelectric sensor with N-doped graphene quantum dots decorated polyaniline layer for non-invasive glucose monitoring in human sweat. Nano Energy 2023, 112, 108505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Ji, J.; Hyun, K.; Lee, H.; Kwon, Y. Flexible, disposable, and portable self-powered glucose biosensors visible to the naked eye. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2022, 372, 132647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartel, M.C.; Lee, D.; Weiss, P.S.; Wang, J.; Kim, J. Resettable sweat-powered wearable electrochromic biosensor. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2022, 215, 114565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Malag’on, S.; Río-Colín, D.; Azizkhani, H.; Aller-Pellitero, M.; Guirado, G.; Javier del Campo, F. A self-powered skin-patch electrochromic biosensor. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 175, 112879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aller-Pellitero, M.; Santiago-Malagon, S.; Ruiz, J.; Alonso, Y.; Lankard, B.; Hihn, J.-Y.; Guirado, G.; Campo, F.J.D. Fully-printed and silicon free self-powered electrochromic biosensors: Towards naked eye quantification. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2020, 306, 127535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Min, J.; Yu, Y.; Wang, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Gao, W. Wireless battery-free wearable sweat sensor powered by human motion. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaay9842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, B.; Liu, Z.; Zheng, Q.; Meng, J.; Ouyang, H.; Zou, Y.; Jiang, D.; Qu, X.; Yu, M.; Zhao, L.; et al. Body-Integrated Self-Powered System for Wearable and Implantable Applications. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 6017–6024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UVAToday. New Microchip Improves Future of Self-Powered Wearable Technology. Available online: https://news.virginia.edu/content/new-microchip-improves-future-self-powered-wearable-technology (accessed on 5 December 2023).

- Vaquer, A.; Barón, E.; de la Rica, R. Detection of low glucose levels in sweat with colorimetric wearable sensors. Analyst 2021, 146, 3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Ji, H.; Huang, H.; Yi, N.; Shi, X.; Xie, S.; Li, Y.; Ye, Z.; Feng, P.; Lin, T.; et al. Wearable Circuits Sintered at 3/4 Room Temperature Directly on the Skin Surface for Health Monitoring. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 45504–45515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Zhixiang, P.; Chunlei, H.; Zhang, B.; Chao, X.; Cheng, H.; Jun, W.; Tang, S. High-energy all-in-one stretchable micro-supercapacitor arrays based on 3D laser-induced graphene foams decorated with mesoporous ZnP nanosheets for self-powered stretchable systems. Nano Energy 2020, 81, 105609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onakpoya, U.U.; Ojo, O.; Eyekpegha, O.J.; Oguns, A.; Akintomide, A.O. Early experience with permanent pacemaker implantation at a tertiary hospital in Nigeria. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2020, 36, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nwafor, C.E. Cardiac Pacemaker Insertion in the South-South Region of Nigeria: Prospects and Challenges. Niger. Health J. 2015, 15, 125–130. [Google Scholar]

- Nakandi, B.T.; Muhimbise, O.; Djuhadi, A.; Mulerwa, M.; McGrath, J.; Makobore, P.N.; Rollins, A.M.; Ssekitoleko, R.T. Experiences of medical device innovators as they navigate the regulatory system in Uganda. Front. Med. Technol. 2023, 5, 1162174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Rigional Office for Africa. MamaOpe Medical. Available online: https//innov.afro.who.int/global-innovation/mamaope-medicals-3891 (accessed on 29 August 2023).

- Wekebere. Pregnacy monitor. Available online: https://wekebere.org (accessed on 29 August 2023).

- Makobore, P.N.; Mulerwa, M. An Electronically Controlled Gravity Feed Infusion Set for Intravenous Fluids. In Biomedical Enginering for Africa; University of Captown Libraries: Cape Town, South Africa, 2019; Chapter 15. [Google Scholar]

- Noubiap, J.J.N.; Jingi, A.M.; Kengne, A.P. Local innovation for improving primary care cardiology in resource-limited African settings: An insight on the Cardio Pad project in Cameroon. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2014, 4, 397–400. [Google Scholar]

- Dzudie, A.; Ouankou, C.N.; Nganhyim, L.; Mouliom, S.; Ba, H.; Kamdem, F.; Ndjebet, J.; Nzali, A.; Tantchou, C.; Nkoke, C.; et al. Long-term prognosis of patients with permanent cardiac pacemaker indication in three referral cardiac centers in Cameroon: Insights from the National pacemaker registryPronostic à long terme des patients avec indication d’un stimulateur cardiaque permanent dans trois centres cardiaques de référence au Cameroun: Aperçu du registre national des stimulateurs cardiaques. Ann. Cardiol. D’angeiologie 2021, 70, 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kuate, G.C.G.; Fotsin, H.B. On the noninear dynamics of a cardiac electrical conduction system model: Theoretical and experimental study. Phys. Scripta 2022, 97, 045205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armand, T.P.T. Developing a Low-Cost IoT-Based Remote Cardiovascular Patient Monitoring System in Cameroon. Healthcare 2023, 11, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quan, T.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.L.; Yang, Y. Hybridized Electromagnetic-Triboelectric Nanogenerator for a Self-Powered Electronic Watch. Am. Chem. Soc. Nano 2015, 9, 12301–12310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, E.; Xie, Z.; Bai, W.; Luan, H.; Ji, B.; Ning, X.; Xia, Y.; Baek, J.W.; Lee, Y.; Yao, K.; et al. Miniaturized electromechanical devices for the characterization of the biomechanics of deep tissue. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 5, 759–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.L.; Yang, Y. Hybridized Electromagnetic-Triboelectric Nanogenerator for Scavenging Biomechanical Energy for Sustainably Powering Wearable Electronics. Am. Chem. Soc. Nano 2015, 9, 3521–3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzina, N.; Zurbuchen, A.; Zumbrunnen, A.; Niederhauser, T.; Reichlin, T.; Burger, J.; Haeberlin, A. A miniaturized endocardial electromagnetic energy harvester for leadless cardiac pacemakers. Plos ONE 2020, 15, e0239667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvarajan, S.; Alluri, N.R.; Chandrasekhar, A.; Kim, S.-J. Unconventional active biosensor made of piezoelectric BaTiO3 nanoparticles for biomolecule detection. Sens. Actuators B 2017, 253, 1180–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; You, Z. A Shoe-Embedded Piezoelectric Energy Harvester for Wearable Sensors. Sensors 2014, 14, 12497–12510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; Qian, X.; Li, N.; Cui, D.; Zhang, H.; Xu, Z. An experimental study on a piezoelectric vibration energy harvester for self-powered cardiac pacemakers. Ann. Transl. Med. 2021, 9, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Han, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, L.; Zhang, C.; Liu, J.; Lu, G.; Yu, H.-D.; Huang, W. Fish Gelatin Based Triboelectric Nanogenerator for Harvesting Biomechanical Energy and Self-Powered Sensing of Human Physiological Signals. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 16442–16450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Yao, S.; Wang, S.; Liu, Z.; Wan, X.; Hu, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Xiong, C.; Li, L. Self-powered energy harvesting and implantable storage system based on hydrogel-enabled all-solid-state supercapacitor and triboelectric nanogenerator. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 463, 142427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, K.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Xu, Z. A triboelectric nanogenerator as self-powered temperature sensor based on PVDF and PTFE. Appl. Phys. A 2018, 124, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, Y.; Moon, S.; Kim, S.; Lee, J. Flexible fabric-based GaAs thin-film solar cell for wearable energy harvesting applications. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2022, 246, 111930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Ghannam, R.; Law, M.-K.; Imran, M.A.; Heidari, H. Photovoltaic power harvesting technologies in biomedical implantable devices considering the optimal location. IEEE J. Electromagn. RF Microw. Med. Biol. 2020, 4, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brogan, Q.; O’Connor, T.; Ha, D.S. Solar and Thermal Energy Harvesting with a Wearable Jacket. IEEE Xplore 2014, 978, 1412–1415. [Google Scholar]

- Bereuter, L.; Williner, S.; Pianezzi, F.; Bissig, B.; Buecheler, S.; Burger, J.; Vogel, R.; Zurbuchen, A.; Haeberlin, A. Energy Harvesting by Subcutaneous Solar Cells: A Long-Term Study on Achievable Energy Output. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 45, 1172–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, M.A.; Abbas, S.M.; Samad, S.A.; Hussain, A. Modulation Techniques for Biomedical Implanted Devices and Their Challenges. Sensors 2012, 12, 297–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of California San Francisco. Pacemaker. Available online: https://www.ucsfhealth.org/treatments/pacemaker (accessed on 5 December 2023).

- Ma, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Liu, Y.; Shi, B.; Xue, X.; Ji, W.; Liu, Z.; Jin, Y.; Zou, Y.; An, Z.; et al. Self-powered, One-Stop, and Multifunctional Implantable Triboelectric Active Sensor for Real-Time Biomedical Monitoring. Nano Lett. 2016, 16, 6042–6051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.H.-L.; da Cruz, L. Retrinal Prothesis System. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2016, 50, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, G.; Kang, L.; Li, J.; Long, Y.; Wei, H.; Ferreira, C.A.; Jeffery, J.J.; Lin, Y.; Cai, W.; Wang, X. Effective weight control via an implanted selfpowered vagus nerve stimulation device. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 5349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latif, R.; Noor, M.M.; Yunas, J.; Hamzah, A.A. Mechanical Energy Sensing and Harvesting in Micromachined Polymer-Based Piezoelectric Transducers for Fully Implanted Hearing Systems: A Review. Polymers 2021, 13, 2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wearable TechnologiesInsights. Harvesting energy from Radio Waves to Power Wearables Devices. Available online: https://cn.bing.com/images/search?view=detailV2&ccid=yPxlk5HU&id=A5FEDCA212F46490AE316A483210ADE4836B3ABA&thid=OIP-C.yPxlk5HUaAa3Atqc8s_aHwHaF9&mediaurl=https%3A%2F%2Fidtxs3.imgix.net%2Fsi%2F40000%2F80%2F5C.png%3Fw%3D800&exph=644&expw=800&q=radio+waves+energy+harvesting.img&simid=607996790824375608&form=IRPRST&ck=CB9D40AD660B3B17773ABF15446562D7&selectedindex=20&itb=0&qpvt=radio+waves+energy+harvesting.img&ajaxhist=0&ajaxserp=0&vt=0&sim=11 (accessed on 5 December 2023).

- Liu, G.; Nie, J.; Han, C.; Jiang, T.; Yang, Z.; Pang, Y.; Xu, L.; Guo, T.; Bu, T.; Zhang, C.; et al. Self powered Electrostatic Adsorption face mask based on a triboelectric nanogenerator. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 7126–7133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, M.; Wang, J.; Liao, W.-H. Self-powered smart watch and wristband enabled by embedded generator. Appl. Energy 2020, 263, 114682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Bank. Access to Electricity (% of Population Sub-Saharan Africa). Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/country/ZG (accessed on 6 December 2023).

- Oxfordinsights. Government AI Readiness Index 2023. Available online: https://oxfordinsights.com/ai-readiness/ (accessed on 6 December 2023).

- World Health Organization. Cardiovascular Deseases/Key Facts. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds) (accessed on 7 December 2023).

- Innovation Toronto. Technology That Restores the Sense of Touch in Nerves as Result of Injury. Available online: http://innovationtoronto.com/2021/07/technology-that-restores-the-sense-of-touch-in-nerves-damaged-as-a-result-of-injury/ (accessed on 7 December 2023).

- Yaabot. Nanorobots: The Future of Medical Innovation. Available online: https://yaabot.com/23051/nanorobots-in-medicine/ (accessed on 7 December 2023).

- Raybaca IOT Technology Co., Ltd. Solar GPS Tracker. Available online: https://rfidlivestocktags.sell.everychina.com/p-108898870-mini-solar-animal-gps-tracker-real-time-animal-tracking-device-for-cattle-horse-camel.html (accessed on 7 December 2023).

- bhphotovideo, Fitbit Sense GPS Smart Watch. Available online: https://www.bhphotovideo.com/c/product/1590668-REG/fitbit_fb512glwt_sense_gps_smartwatch_lunar.html (accessed on 7 December 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).