Physical Length and Weight Reduction of Humanoid In-Robot Network with Zonal Architecture

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background and Related Works

2.1. Development Status in the Humanoid Robot Field

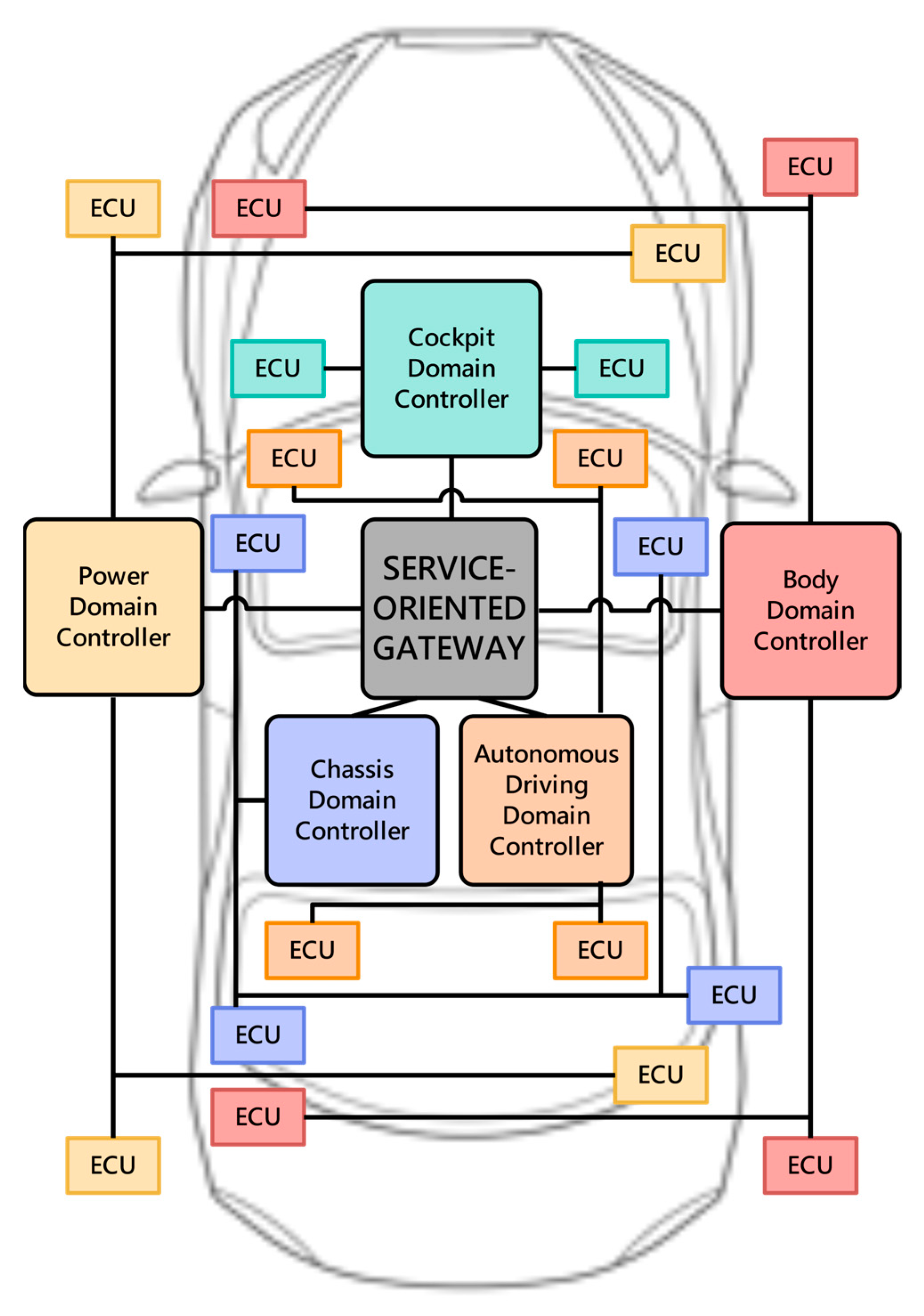

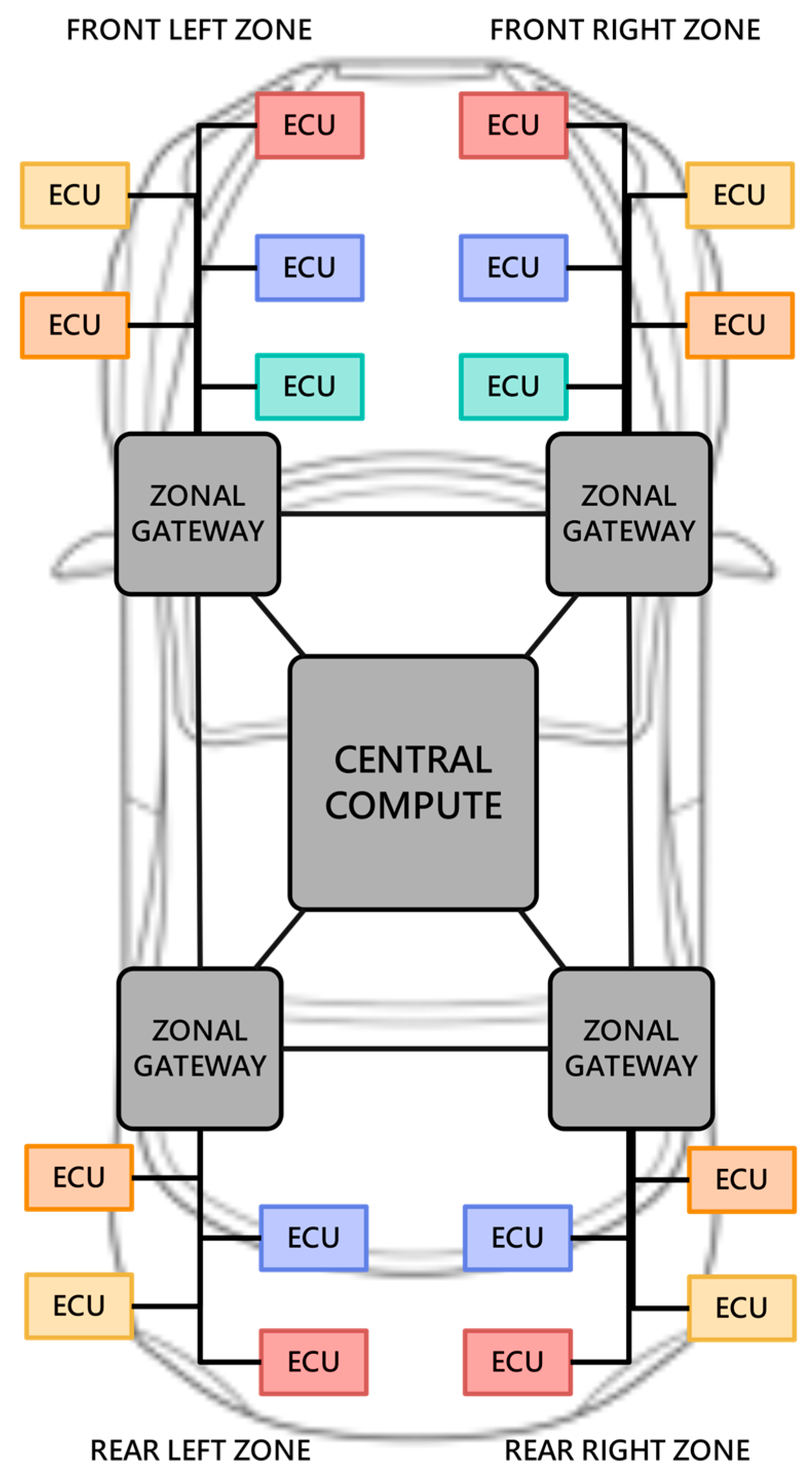

2.2. Comparison of Domain IVN Architecture and Zonal IVN Architecture

2.2.1. Domain IVN Architecture

2.2.2. Zonal IVN Architecture

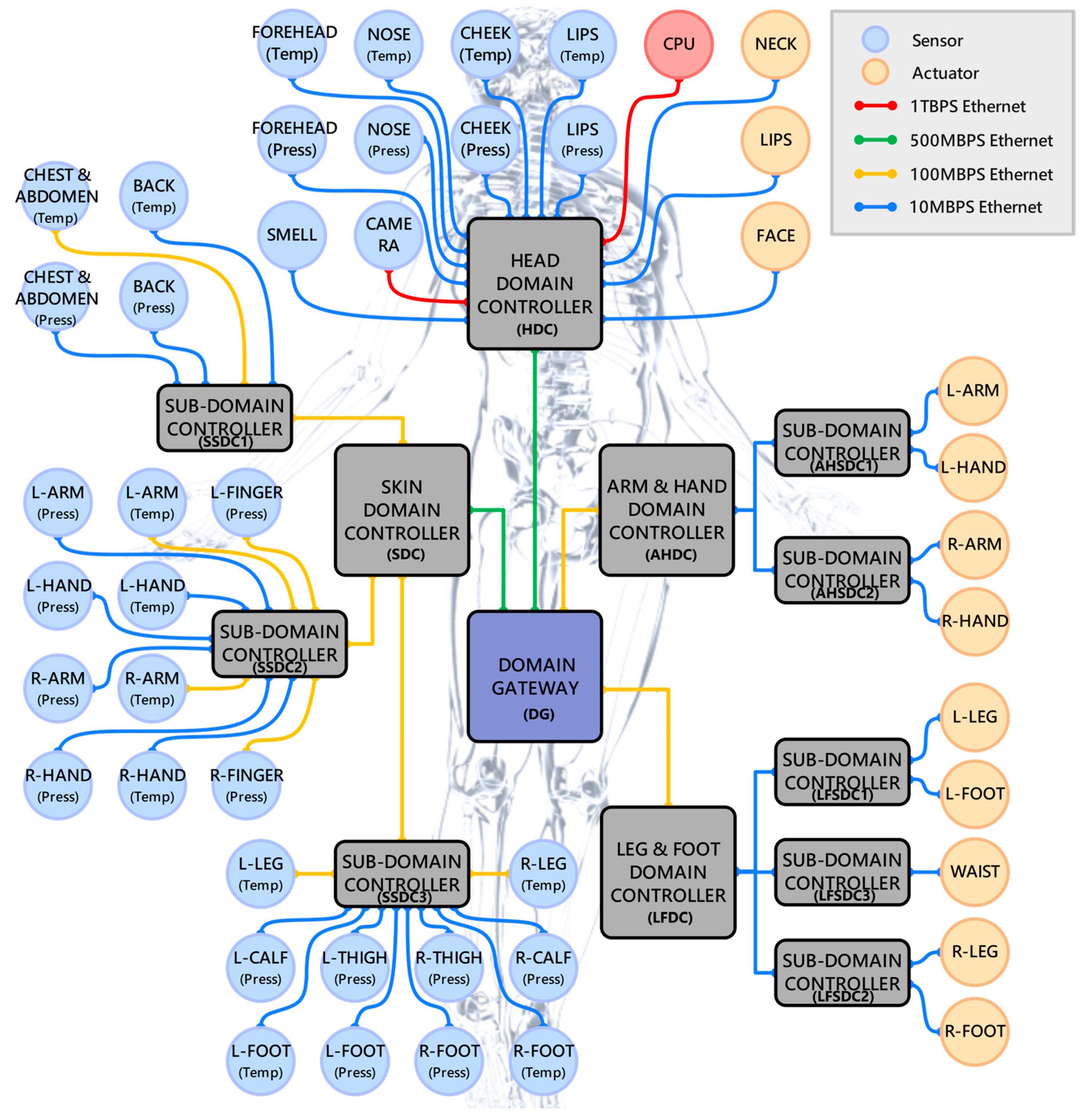

3. Comparison of Domain and Zonal IRN Architecture for Humanoid Robots

3.1. Domain IRN Architecture

3.2. Zonal IRN Architecture

4. Wiring Harness Comparison of Domain and Zonal IRN Architecture

4.1. Data Transmission Link Parameter of Domain IRN Architecture

4.2. Data Transmission Link Parameter of the Zonal IRN Architecture

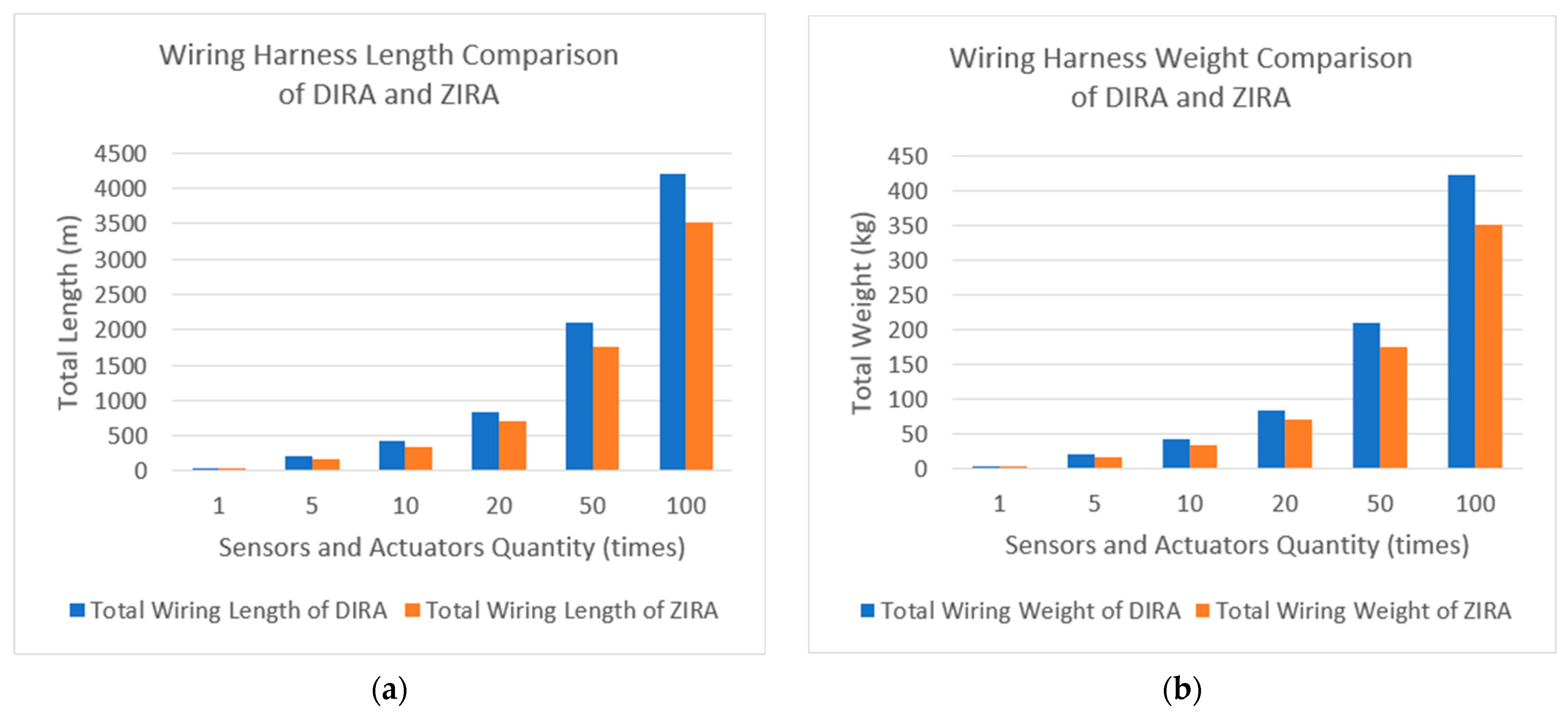

4.3. Wiring Harness Weight and Length Comparison of DIRA and ZIRA

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kajita, S.; Hirukawa, H.; Harada, K.; Yokoi, K. Introduction to Humanoid Robotics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; Volume 101. [Google Scholar]

- Oztop, E.; Franklin, D.W.; Chaminade, T.; Cheng, G. Human–humanoid interaction: Is a humanoid robot perceived as a human? Int. J. Hum. Robot. 2005, 2, 537–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerpa, O.; Weiss, K.; Worn, H. Development of a flexible tactile sensor system for a humanoid robot. In Proceedings of the 2003 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS 2003)(Cat. No. 03CH37453), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–31 October 2003; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas-Quintero, J.; Rodríguez-Liñán, M. A literature review of sensor heads for humanoid robots. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2021, 143, 103834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Xinjilefu, X.; Atkeson, C.G.; Kim, J. Optimization based controller design and implementation for the atlas robot in the darpa robotics challenge finals. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE-RAS 15th International Conference on Humanoid Robots (Humanoids), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 3–5 November 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 1028–1035. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, G.; Saunders, A.; Playter, R. The petman and atlas robots at boston dynamics. Hum. Robot. A Ref. 2019, 169, 186. [Google Scholar]

- Sowmiya, S.; Ramachandran, M.; Chinnasamy, S.; Prasanth, V.; Sriram, S. A Study on Humanoid Robots and Its Psychological Evaluation. Des. Model. Fabr. Adv. Robot. 2022, 1, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, C.; Park, S. In-Robot Network Architectures for Humanoid Robots With Human Sensor and Motor Functions. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 89325–89335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Park, S. Simulating In-robot Network Architecture For Humanoid Robots. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Symposium on Intelligent Signal Processing and Communication Systems (ISPACS), Hualien City, Taiwan, 16–19 November 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, T.; Cui, C.; Park, S. The In-Robot Network Structure of Humanoid Robot for Burst Traffic Data Situations. In Proceedings of the 2021 7th IEEE International Conference on Network Intelligence and Digital Content (IC-NIDC), Beijing, China, 17–19 November 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 474–478. [Google Scholar]

- Hirai, K.; Hirose, M.; Haikawa, Y.; Takenaka, T. The development of Honda humanoid robot. In Proceedings of the 1998 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (Cat. No. 98CH36146), Leuven, Belgium, 20 May 1998; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1998; pp. 1321–1326. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.; Chaudhary, D.; Gupta, A.D.; Lohani, B.P.; Kushwaha, P.K.; Bibhu, V. Artificial Intelligence, Cognitive Robotics and Nature of Consciousness. In Proceedings of the 2022 3rd International Conference on Intelligent Engineering and Management (ICIEM), London, UK, 27–29 April 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 447–454. [Google Scholar]

- Bandur, V.; Pantelic, V.; Tomashevskiy, T.; Lawford, M. A Safety Architecture for Centralized E/E Architectures. In Proceedings of the 2021 51st Annual IEEE/IFIP International Conference on Dependable Systems and Networks Workshops (DSN-W), Taipei, Taiwan, 21–24 June 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 67–70. [Google Scholar]

- Diewald, S.; Möller, A.; Roalter, L.; Stockinger, T.; Kranz, M. Gameful design in the automotive domain: Review, outlook and challenges. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Automotive User Interfaces and Interactive Vehicular Applications, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 28–30 October 2013; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 262–265. [Google Scholar]

- Frigerio, A.; Vermeulen, B.; Goossens, K.G. Automotive architecture topologies: Analysis for safety-critical autonomous vehicle applications. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 62837–62846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frigerio, A.; Vermeulen, B.; Goossens, K. Component-level ASIL decomposition for automotive architectures. In Proceedings of the 2019 49th Annual IEEE/IFIP International Conference on Dependable Systems and Networks Workshops (DSN-W), Portland, OR, USA, 24–27 June 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 62–69. [Google Scholar]

- Shigemi, S.; Goswami, A.; Vadakkepat, P. ASIMO and humanoid robot research at Honda. Hum. Robot. A Ref. 2018, 1, 55–90. [Google Scholar]

- Sakagami, Y.; Watanabe, R.; Aoyama, C.; Matsunaga, S.; Higaki, N.; Fujimura, K. The intelligent ASIMO: System overview and integration. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Lausanne, Switzerland, 30 September–4 October 2002; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2002; pp. 2478–2483. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, L. Meet the Tokyo robots. Eng. Technol. 2021, 16, 28–31. [Google Scholar]

- Brunner, S.; Roder, J.; Kucera, M.; Waas, T. Automotive E/E-architecture enhancements by usage of ethernet TSN. In Proceedings of the 2017 13th Workshop on Intelligent Solutions in Embedded Systems (WISES), Hamburg, Germany, 12–13 June 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Traub, M.; Maier, A.; Barbehön, K.L. Future automotive architecture and the impact of IT trends. IEEE Softw. 2017, 34, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Park, S. Time-sensitive network (TSN) experiment in sensor-based integrated environment for autonomous driving. Sensors 2019, 19, 1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tippe, L.; Pilgrim, L.; Fröschl, J.; Herzog, H.-G. Modular Simulation of Zonal Architectures and Ring Topologies for Automotive Power Nets. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Vehicle Power and Propulsion Conference (VPPC), Gijon, Spain, 25–28 October 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Kenjić, D.; Antić, M. Connectivity Challenges in Automotive Solutions. IEEE Consum. Electron. Mag. 2022; early access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Park, S. Performance Evaluation of Zone-Based In-Vehicle Network Architecture for Autonomous Vehicles. Sensors 2023, 23, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Pérez, A.; Pérez de Aranda, R.; Prefasi, E.; Dumont, S.; Rosado, J.; Enrique, I.; Pinzón, P.; Ortiz, D. Toward the Multi-Gigabit Ethernet for the Automotive Industry. Fiber Integr. Opt. 2021, 40, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEEE P802. 3cz™/D3.2; Draft Standard for Ethernet Amendment 7: Physical Layer Specifications and Management Parameters for Multi-Gigabit Optical Ethernet Using Graded-Index Glass Optical Fiber for Application in the Automotive Environment. IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022.

- Austermann, C.; Frei, S. Immunity of CAN, CAN FD and Automotive Ethernet 100/1000BASE-T1 to Crosstalk From Power Electronic Systems. IEEE Trans. Electromagn. Compat. 2022, 64, 2283–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austermann, C.; Kleinen, M.; Olbrich, M.; Jeschke, S.; Hangmann, C.; Wüllner, I.; Frei, S. Störfestigkeitsanalyse von 100BASE-T1 und 1000BASE-T1 Automotive Ethernet-Kommunikationssystemen Mittels Direct Power Injection; Apprimus: Aachen, Germany, 2022; pp. 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariño, A.G.; Fons, F.; Arostegui, J.M.M. The future roadmap of in-vehicle network processing: A HW-centric (R-) evolution. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 69223–69249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Park, S. Equivalent Data Information of Sensory and Motor Signals in the Human Body. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 69661–69670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Transmission Path | Traffic Type | Payload Size (Byte) | Ethernet Bandwidth | Average Length (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forehead (Temp) → HDC | Sensor | 232 | 10 Mbps | 0.32 |

| Forehead (Press) → HDC | Sensor | 14 | 10 Mbps | 0.32 |

| Nose (Temp) → HDC | Sensor | 130 | 10 Mbps | 0.22 |

| Nose (Press) → HDC | Sensor | 30 | 10 Mbps | 0.22 |

| Cheek (Temp) → HDC | Sensor | 31.96 k | 10 Mbps | 0.20 |

| Cheek (Press) → HDC | Sensor | 9.86 k | 10 Mbps | 0.20 |

| Lips (Temp) → HDC | Sensor | 92 | 10 Mbps | 0.18 |

| Lips (Press) → HDC | Sensor | 20 | 10 Mbps | 0.18 |

| Smell → HDC | Sensor | 1000 | 10 Mbps | 0.22 |

| Camera → HDC | Sensor | 3.46 G | 1 Tbps | 0.28 |

| HDC ↔ CPU | Sensor and Control | N/A | 1 Tbps | 0.30 |

| HDC → Neck | Control | 10 | 10 Mbps | 0.07 |

| HDC → Lips | Control | 6 | 10 Mbps | 0.18 |

| HDC → Face | Control | 80 | 10 Mbps | 0.20 |

| Transmission Path | Traffic Type | Payload Size (Byte) | Ethernet Bandwidth | Average Length (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chest and Abdomen (Temp) → SSDC1 | Sensor | 52.99 k | 100 Mbps | 0.20 |

| Chest and Abdomen (Press) → SSDC1 | Sensor | 492 | 10 Mbps | 0.20 |

| Back (Temp) → SSDC1 | Sensor | 33.02 k | 10 Mbps | 0.20 |

| Back (Press) → SSDC1 | Sensor | 2.71 k | 10 Mbps | 0.20 |

| SSDC1 → SDC | Sensor | N/A | 100 Mbps | 0.15 |

| L-Arm (Temp) → SSDC2 | Sensor | 38.4 k | 100 Mbps | 0.47 |

| L-Arm (Press) → SSDC2 | Sensor | 2.54 k | 10 Mbps | 0.47 |

| L-Finger (Press) → SSDC2 | Sensor | 9.60 k | 100 Mbps | 0.55 |

| L-Hand (Temp) → SSDC2 | Sensor | 9.60 k | 10 Mbps | 0.51 |

| L-Hand (Press) → SSDC2 | Sensor | 600 | 10 Mbps | 0.51 |

| R-Arm (Temp) → SSDC2 | Sensor | 38.4 k | 100 Mbps | 0.47 |

| R-Arm (Press) → SSDC2 | Sensor | 2.54 k | 10 Mbps | 0.47 |

| R-Finger (Press) → SSDC2 | Sensor | 9.60 k | 100 Mbps | 0.55 |

| R-Hand (Temp) → SSDC2 | Sensor | 9.60 k | 10 Mbps | 0.51 |

| R-Hand (Press) → SSDC2 | Sensor | 600 | 10 Mbps | 0.51 |

| SSDC2 → SDC | Sensor | N/A | 100 Mbps | 0.20 |

| L-Leg (Temp) → SSDC3 | Sensor | 49.53 k | 100 Mbps | 0.65 |

| L-Calf (Press) → SSDC3 | Sensor | 1.62 k | 10 Mbps | 0.90 |

| L-Thigh (Press) → SSDC3 | Sensor | 2.94 k | 10 Mbps | 0.45 |

| L-Foot (Temp) → SSDC3 | Sensor | 11.90 k | 10 Mbps | 1.15 |

| L-Foot (Press) → SSDC3 | Sensor | 372 | 10 Mbps | 1.15 |

| R-Leg (Temp) → SSDC3 | Sensor | 49.53 k | 100 Mbps | 0.65 |

| R-Calf (Press) → SSDC3 | Sensor | 1.62 k | 10 Mbps | 0.90 |

| R-Thigh (Press) → SSDC3 | Sensor | 2.94 k | 10 Mbps | 0.45 |

| R-Foot (Temp) → SSDC3 | Sensor | 11.90 k | 10 Mbps | 1.15 |

| R-Foot (Press) → SSDC3 | Sensor | 372 | 10 Mbps | 1.15 |

| SSDC3 → SDC | Sensor | N/A | 100 Mbps | 0.30 |

| Transmission Path | Traffic Type | Payload Size (Byte) | Ethernet Bandwidth | Average Length (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AHSDC1 → L-Arm | Control | 12 | 10 Mbps | 0.27 |

| AHSDC1 → L-Hand | Control | 5 | 10 Mbps | 0.31 |

| AHSDC2 → R-Arm | Control | 12 | 10 Mbps | 0.27 |

| AHSDC2 → R-Hand | Control | 5 | 10 Mbps | 0.31 |

| AHDC → AHSDC1 | Control | N/A | 10 Mbps | 0.20 |

| AHDC → AHSDC2 | Control | N/A | 10 Mbps | 0.20 |

| LFSDC1 → L-Leg | Control | 19 | 10 Mbps | 0.50 |

| LFSDC1 → L-Foot | Control | 6 | 10 Mbps | 1.00 |

| LFSDC2 → R-Leg | Control | 19 | 10 Mbps | 0.50 |

| LFSDC2 → R-Foot | Control | 6 | 10 Mbps | 1.00 |

| LFSDC3 →Waist | Control | 55 | 10 Mbps | 0.20 |

| LFDC → LFSDC1 | Control | N/A | 10 Mbps | 0.15 |

| LFDC → LFSDC2 | Control | N/A | 10 Mbps | 0.15 |

| LFDC → LFSDC3 | Control | N/A | 10 Mbps | 0.20 |

| Transmission Path | Traffic Type | Ethernet Bandwidth | Average Length (m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domain Gateway ↔ HDC | Sensor and Control | 500 Mbps | 0.27 |

| SDC → Domain Gateway | Sensor | 500 Mbps | 0.31 |

| Domain Gateway ↔ AHDC | Control | 100 Mbps | 0.27 |

| Domain Gateway ↔ LFDC | Control | 100 Mbps | 0.31 |

| Transmission Path | Traffic Type | Payload Size (Byte) | Ethernet Bandwidth | Average Length (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forehead (Temp) → HZG | Sensor | 232 | 10 Mbps | 0.32 |

| Forehead (Press) → HZG | Sensor | 14 | 10 Mbps | 0.32 |

| Nose (Temp) → HZG | Sensor | 130 | 10 Mbps | 0.22 |

| Nose (Press) → HZG | Sensor | 30 | 10 Mbps | 0.22 |

| Cheek (Temp) → HZG | Sensor | 31.96 k | 10 Mbps | 0.20 |

| Cheek (Press) → HZG | Sensor | 9.86 k | 10 Mbps | 0.20 |

| Lips (Temp) → HZG | Sensor | 92 | 10 Mbps | 0.18 |

| Lips (Press) → HZG | Sensor | 20 | 10 Mbps | 0.18 |

| Smell → HZG | Sensor | 1000 | 10 Mbps | 0.22 |

| Camera → HZG | Sensor | 3.46 G | 1 Tbps | 0.28 |

| HZG ↔ CPU | Sensor and Control | N/A | 1 Tbps | 0.30 |

| HZG → Neck | Control | 10 | 10 Mbps | 0.07 |

| HZG → Lips | Control | 6 | 10 Mbps | 0.18 |

| HZG → Face | Control | 80 | 10 Mbps | 0.18 |

| Transmission Path | Traffic Type | Payload Size (Byte) | Ethernet Bandwidth | Average Length (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L-Arm (Temp) → LAZG | Sensor | 38.4 k | 100 Mbps | 0.27 |

| L-Arm (Press) → LAZG | Sensor | 2.54 k | 10 Mbps | 0.27 |

| L-Finger (Press) → LAZG | Sensor | 9.60 k | 100 Mbps | 0.35 |

| L-Hand (Temp) → LAZG | Sensor | 9.60 k | 10 Mbps | 0.31 |

| L-Hand (Press) → LAZG | Sensor | 600 | 10 Mbps | 0.31 |

| LAZG → L-Arm | Control | 12 | 10 Mbps | 0.27 |

| LAZG → L-Hand | Control | 5 | 10 Mbps | 0.31 |

| Transmission Path | Traffic Type | Payload Size (Byte) | Ethernet Bandwidth | Average Length (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R-Arm (Temp) → RAZG | Sensor | 38.4 k | 100 Mbps | 0.27 |

| R-Arm (Press) → RAZG | Sensor | 2.54 k | 10 Mbps | 0.27 |

| R-Finger (Press) → RAZG | Sensor | 9.60 k | 100 Mbps | 0.35 |

| R-Hand (Temp) → RAZG | Sensor | 9.60 k | 10 Mbps | 0.31 |

| R-Hand (Press) → RAZG | Sensor | 600 | 10 Mbps | 0.31 |

| RAZG → R-Arm | Control | 12 | 10 Mbps | 0.27 |

| RAZG → R-Hand | Control | 5 | 10 Mbps | 0.31 |

| Transmission Path | Traffic Type | Payload Size (Byte) | Ethernet Bandwidth | Average Length (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chest and Abdomen (Temp) → TZG | Sensor | 52.99 k | 100 Mbps | 0.20 |

| Chest and Abdomen (Press) → TZG | Sensor | 492 | 10 Mbps | 0.20 |

| Back (Temp) → TZG | Sensor | 33.02 k | 10 Mbps | 0.20 |

| Back (Press) → TZG | Sensor | 2.71 k | 10 Mbps | 0.20 |

| TZG →Waist | Control | 55 | 10 Mbps | 0.20 |

| Transmission Path | Traffic Type | Payload Size (Byte) | Ethernet Bandwidth | Average Length (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L-Leg (Temp) → LLZG | Sensor | 49.53 k | 100 Mbps | 0.50 |

| L-Calf (Press) → LLZG | Sensor | 1.62 k | 10 Mbps | 0.75 |

| L-Thigh (Press) → LLZG | Sensor | 2.94 k | 10 Mbps | 0.30 |

| L-Foot (Temp) → LLZG | Sensor | 11.90 k | 10 Mbps | 1.00 |

| L-Foot (Press) → LLZG | Sensor | 372 | 10 Mbps | 1.00 |

| LLZG → L-Leg | Control | 19 | 10 Mbps | 0.50 |

| LLZG → L-Foot | Control | 6 | 10 Mbps | 1.00 |

| Transmission Path | Traffic Type | Payload Size (Byte) | Ethernet Bandwidth | Average Length (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R-Leg (Temp) → RLZG | Sensor | 49.53 k | 100 Mbps | 0.50 |

| R-Calf (Press) → RLZG | Sensor | 1.62 k | 10 Mbps | 0.75 |

| R-Thigh (Press) → RLZG | Sensor | 2.94 k | 10 Mbps | 0.30 |

| R-Foot (Temp) → RLZG | Sensor | 11.90 k | 10 Mbps | 1.00 |

| R-Foot (Press) → RLZG | Sensor | 372 | 10 Mbps | 1.00 |

| RLZG → R-Leg | Control | 19 | 10 Mbps | 0.50 |

| RLZG → R-Foot | Control | 6 | 10 Mbps | 1.00 |

| Transmission Path | Traffic Type | Ethernet Bandwidth | Average Length (m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Head Zone Gateway ↔ Torso Zone Gateway | Sensor and Control | 100 Mbps | 0.10 |

| Head Zone Gateway ↔ Left Arm Zone Gateway | Sensor and Control | 100 Mbps | 0.36 |

| Head Zone Gateway ↔ Right Arm Zone Gateway | Sensor and Control | 100 Mbps | 0.36 |

| Head Zone Gateway ↔ Left Leg Zone Gateway | Sensor and Control | 100 Mbps | 0.47 |

| Head Zone Gateway ↔ Right Leg Zone Gateway | Sensor and Control | 100 Mbps | 0.47 |

| Sensors and Actuator Quantity | Total Component Number | DIRA Total Length (m) | ZIRA Total Length (m) | DIRA Total Weight (kg) | ZIRA Total Weight (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 time | 92 | 45.65 | 37.66 | 4.56 | 3.76 |

| 5 times | 444 | 214.21 | 178.06 | 21.42 | 17.80 |

| 10 times | 884 | 424.91 | 353.56 | 42.49 | 35.35 |

| 20 times | 1764 | 846.31 | 704.56 | 84.63 | 70.45 |

| 50 times | 4404 | 2110.51 | 1757.56 | 211.05 | 175.75 |

| 100 times | 8804 | 4217.51 | 3512.56 | 421.75 | 351.25 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cui, C.; Park, C.; Park, S. Physical Length and Weight Reduction of Humanoid In-Robot Network with Zonal Architecture. Sensors 2023, 23, 2627. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23052627

Cui C, Park C, Park S. Physical Length and Weight Reduction of Humanoid In-Robot Network with Zonal Architecture. Sensors. 2023; 23(5):2627. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23052627

Chicago/Turabian StyleCui, Chengyu, Chulsun Park, and Sungkwon Park. 2023. "Physical Length and Weight Reduction of Humanoid In-Robot Network with Zonal Architecture" Sensors 23, no. 5: 2627. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23052627

APA StyleCui, C., Park, C., & Park, S. (2023). Physical Length and Weight Reduction of Humanoid In-Robot Network with Zonal Architecture. Sensors, 23(5), 2627. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23052627