Abstract

(1) Objective: to analyze current active noninvasive measurement systems of the thoracic range of movements of the spine. (2) Methods: A systematic review and meta-analysis were performed that included observational or clinical trial studies published in English or Spanish, whose subjects were healthy human males or females ≥18 years of age with reported measurements of thoracic range of motion measured with an active system in either flexion, extension, lateral bending, or axial rotation. All studies that passed the screening had a low risk of bias and good methodological results, according to the PEDro and MINORS scales. The mean values and 95% confidence interval of the reported measures were calculated for different types of device groups. To calculate the differences between the type of device measures, studies were pooled for different types of device groups using Review Manager software. (3) Results: 48 studies were included in the review; all had scores higher than 7.5 over 10 on the PEDro and MINORs methodological rating scales, collecting a total of 2365 healthy subjects, 1053 males and 1312 females; they were 39.24 ± 20.64 years old and had 24.44 ± 3.81 kg/m2 body mass indexes on average. We summarized and analyzed a total of 11,892 measurements: 1298 of flexoextension, 1394 of flexion, 1021 of extension, 491 of side-to-side lateral flexion, 637 of right lateral flexion, 607 of left lateral flexion, 2170 of side-to-side rotation, 2152 of right rotation and 2122 of left rotation. (4) Conclusions: All collected and analyzed measurements of physiological movements of the dorsal spine had very disparate results from each other, the cause of the reason for such analysis is that the measurement protocols of the different types of measurement tools used in these measurements are different and cause measurement biases. To solve this, it is proposed to establish a standardized measurement protocol for all tools.

Keywords:

range of motion; movement; mobility; range of movement; thoracic; spine; system; device; tool 1. Introduction

Over the years, different types of spinal column tools have been appearing; some are directed to the cervical spine, others to the lumbar spine, and many others to the dorsal spine. These tools are essential for the assessment of the column, serve as a method of evaluating joint mobility [1], assess the existence of pain on movement [2,3], and prevent vertebral pathologies [4,5,6]. They are also essential for the research that has been carried out through the years on new spinal treatment methods.

The physiological movements of the dorsal spine have been measured for more than 40 years, leading to the emergence of a multitude of tools and different performance protocols from the first studies with goniometers and inclinometers [7] to the latest with applications for cell phones [8]; within this large section, the tools can measure one or more of the different planes of motion that the dorsal spine has, which are the sagittal plane (flexion and extension), the coronal plane (right tilt and left tilt) and the transverse plane (right rotation and left rotation).

Within the wide variety of tools, a distinction can be made between different types depending on how they obtain the degrees of measurement. The first tools to emerge were mechanical devices [8,9,10]. They are those tools not provided with electricity that work by transmitting the movement of the subject, measuring the degrees of mobility directly. These devices include, for example, the Goniometer and the Inclinometer. The rest of the tools were emerging with the industrial evolution and the improvement of the present resources, as was the case of the electromechanical devices [11,12,13] that are simply mechanical tools equipped with better and more innovative electronic equipment to improve the sensitivity, specificity, and comfort of the professional by increasing the complexity of the tool and providing it with a receiver responsible for transmitting the movement of the subject to be processed by a computer. These tools are the Electro-Goniometer, the Digital Inclinometer, and the Spinal Mouse. On the other hand, another way of assessing dorsal physiological movements through the study of images emerged; these tools were called three-dimensional optical motion analysis devices [13,14]. They consist of a photo or video camera and an image analysis processor studying either the image of the initial position and the image of the final position or the elapsed movement, in other words, these tools analyze three-dimensional images. As new methods of reception and transmission of dorsal physiological movements emerged, new tools appeared, such as accelerometer tracking device [15] (XSENS TMX or the 3A Sensor String), ultrasound tracking device [16] (CMS 20 ZEBRIS), and electromagnetic tracking device [17] (Fastrak), these tools obtain the degrees of movement of the subject with a specialized sensor. Finally, the last type of tools were adapted to our daily life, with phones used for the measurement of dorsal ranges; these tools are mobile phone applications [8,11], as is the case of the Clinometer App. The classification of all the tools analyzed in this study can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

Classification of the tools analyzed.

In addition to the different types of tools present, it is also important to know the different measurement positions that are present within the protocols of each tool, which are seated, standing, gentleman position, and Mahometan position.

Throughout the years that these tools have been emerging, there has been no consensus, in fact, each tool has its initial position, its final position, its placement of the device, its different indications, its measurement time, in short, each tool has its protocol of action. It is interesting to see how these factors can affect the measurements of the different movements of the dorsal column; therefore, we aimed to analyze current active noninvasive measurement systems of the thoracic range of movements of the spine.

2. Methods

The systematic review realized in this study is in accordance with the PRISMA statement extension for systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analysis: PRISMA-NMA statement (2015) [18] and with The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews [19]. This study followed PROSPERO [20] regulations and guidelines and is registered under ID CRD42021231380.

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

The following inclusion criteria were used: (1)measurements were performed on asymptomatic subjects without a current or previous history of spinal disorders or low back pain, (2) subjects were male or female humans ≥18 years old, (3) reported thoracic RoM measurements, (4) measured an active RoM either in flexion, extension, lateral bending, or axial rotation, (5) referenced initial position measurement, (6) published observational or clinical trial studies and (7) studies in English or Spanish.

On the other side, the studies with the following standards were excluded: (1) if the studies were Review, Meta-analysis, Case reports, Systematic review, book or letter, (2) any cadaveric or impact studies, (3) if subjects had any pathology or surgery of the spine, cancer, aorta’s pathology, rheumatic diseases, or scoliosis, (4) if the measurements were made with ionizing devices or with tools that there were no records of their use in the last 20 years, (5) studies of the respiratory movements and (6) studies of the thoracic spine movement while walking or running.

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

The search began on Monday 11 January 2021 and finished on Friday 17 February 2021. Search criteria with MESH terms, including Thoracic, tool, device, system, measure, rotation, bending, extension, flexion, motion, mobility, kinematic, movement and range of motion, were used with logical operators (AND, OR) to search the electronic databases of (1) PubMed (National Library of Medicine and National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA), (2) Cochrane (Clarivate analytics, USA), (3) EMBASE (Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, NLD) and (4) Web of Science (Clarivate analytics, USA). The full search string that was used is in Appendix A.

2.3. Selection Process

All the selection process was made by one of the authors (P.E.-G.). In the initial search, it was utilized an automatic tool of the databases to remove all the Review, Meta-analysis, Case reports, Systematic review, book, or letter study types. After that, studies passed the initial screening by titles, screening by abstract, and concluded with a full-text screening following the inclusion and exclusion criteria mentioned above.

2.4. Data Collection Process and Variables

The data were managed in the Microsoft Excel® software, where the extraction data including the year of publication, number of subjects, sex, body height, weight, body mass index, name device, type of measuring device, software device, measurement posture, and the right and left thoracic RoM of flexion, extension, lateral bending or axial rotation measured, were tabulated. We recruited all of these measures of each device.

2.5. Study Risk of Bias Assessment

Initially, two authors (P.E.-G. and E.A.S.-R.) collected the papers included in the review and studied the methodological quality and risk of bias of the articles using the PEDro scale for experimental studies and MINORS scale for observational studies.

The PEDro scale is based on the Delphi list developed by Verhagen and collaborators at the Department of Epidemiology, Maastricht University [21]. For the most part, the list is based on expert consensus and not on empirical data. The purpose of the PEDro scale is to help users of the PEDro databases to quickly identify which of the randomized clinical trials may have sufficient internal validity (criteria 2–9) and sufficient statistical information to make their results interpretable (criteria 10–11). An additional criterion (criterion 1) relates to external validity, but this criterion will not be used for the calculation of the PEDro scale score.

The MINORS Scale [22,23] (Methodological index for non-randomized studies) is a tool designed to evaluate non-randomized trials and observational studies. This scale includes 8 items for non-randomized studies and 4 more items for comparative studies. Each item is evaluated with a score between 0 (not reported), 1 (reported but incomplete) and 2 (reported and complete). The first 4 items plus the 8th item refer to the methodology and design of the study, whereas items 5, 6, 7 refer to the results obtained. On the other hand, items 9, 10, 11 and 12 are based on additional criteria for comparative studies. The maximum score that can be obtained is 16 for non-randomized studies and 24 for comparative studies.

2.6. Data Synthesis Methods and Meta-Analysis

The mean values and 95% confidence interval (CI) range of Flexo-Extension (rFE), range of Flexion (rF), range of Extension (rE), range of Side to Side Lateral Flexion (rSSLF), range of Right Lateral Flexion (rRLF), range of Left Lateral Flexion (rLLF), range of Side to Side Rotation (rSSR), range of Right Rotation (rRR) and range of Left Rotation (rLR) were calculated for different type of device groups: Mechanical Devices (MD), Electro Mechanical Devices (EMD), 3Dimensional Optical Motion Analysis (3-DOMA), Accel-erometer Tracking Devices (ATD), Ultrasound Tracking Devices (UTD), Electro Magnetic Tracking De-vices (EMGTD) and Mobile Phone Applications (MPA). To calculate the differences between the type of device measures, studies were pooled for different types of device groups using Review Manager software (RevMan, version 5.4. Copenhagen: The Nordic Center, The Cochrane Collaboration, London, UK, 2014). The meta-analysis was performed using the random-effects model to compare the different types of devices measures and for considering heterogeneity among all measures. Statistical heterogeneity was evaluated based on the inconsistency (I2) index that provides an estimated percentage of the total variation across the measures of the studies that were included. The scale of heterogeneity was considered, whereby <25% indicates low, 25–75% medium, and >75% high heterogeneity [24]. Mean pooled differences and 95% CIs in rFE, rF, rE, rSSLF, rRLF, rLLF, rSSR, rRR, and rLR between different types of device measures were presented as statistically significant when p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

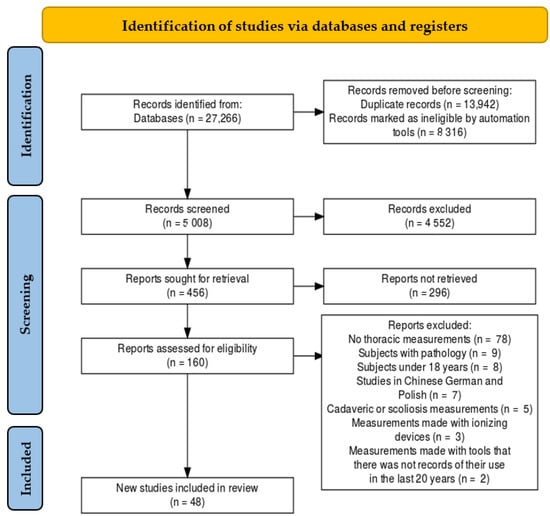

The electronic search saved a total of 27,266 publications in the databases mentioned (Figure 1). Following the selected criteria, title and abstract screening, and the removal of the duplicates in the four databases, 27,106 papers were excluded. The remaining 160 full-text papers were screened for eligibility and 112 were excluded. Among these, 78 had missing thoracic measurements, 9 had subjects with pathology, 8 had subjects aged under 18 years, 7 studies were in Chinese, German, or Polish, 5 papers had cadaveric or scoliosis measurements, 3 publications had measurements made with ionizing devices and 2 studies had measurements made with tools that there were not records of their use in the last 20 years. Finally, 48 studies were included in the review; all had scores higher than 7.5 over 10 on the PEDro and MINORs methodological rating scales (Appendix B and Appendix C). These studies were performed in Europe (17), Oceania (11), Asia (11), and Americas (9). Among these, 48 studies were considered in the meta-analysis.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow diagram.

3.2. Study Characteristics

A synthesis of the objective, methodology, and results of the included studies are presented in Table 2 and their characteristics are presented in Table 3. The total number of healthy participants in these papers was 2365, with 1053 males and 1312 females; the sample size ranged from 12 [25,26] to 120 [27], in the sagittal plane. The total number of healthy measured participants was 1707, the total in the coronal plane was 591, and in the transversal plane, the total number was 888 subjects. The number of healthy female and male subjects are presented in Table 4.

Table 2.

Descriptive analysis of each study.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the included studies.

Table 4.

Number of healthy subjects in function of measurement realized.

A total of seven types of the device were registered: mechanical devices (42 measures), electromechanical devices (34 measures), three-dimensional optical motion analysis (46 measures), accelerometer tracking devices (20 measures), ultrasound tracking devices (20 measures), electromagnetic tracking devices (12 measures) and mobile phone applications (9 measures). All measurements realized according to the different ranges of movement and the device used are present in Table 5. The EMD and the UTD were not used to measure the coronal plane and the MPA were not used to measure the sagittal and coronal plane.

Table 5.

The number of studies according to the different ranges of movement and device used.

Three different types of postures were collected in the measurements: standing (32 measures), sitting (18 measures), and lumbar locked rotation test (10 measures). The devices that made the most measurements while standing (12) were electromechanical devices and three-dimensional optical motion analysis. The device that made the most measurement while sitting and in the lumbar locked rotation test (5) was mechanical devices. All the measurements postures and the devices used are present in Table 6.

Table 6.

Number of studies according to the different measurements postures and devices used.

The demographic data of the selected subjects depending on the type of device used are presented in Table 7 and the demographic data of the selected subjects depending on the type of position measure are presented in Table 8.

Table 7.

Demographic data of the selected subjects depending on the type of device used.

Table 8.

Demographic data of the selected subjects depending on the type of position measure.

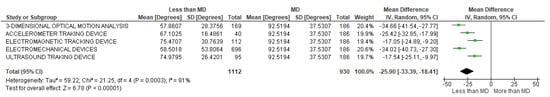

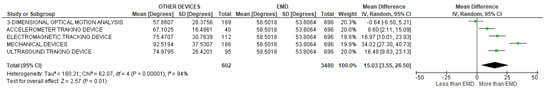

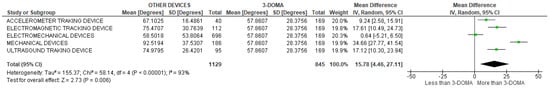

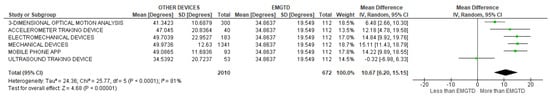

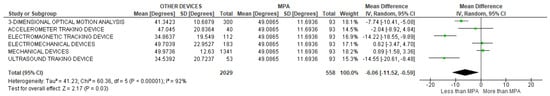

Grouping tools according to the type of device we summarized and analyzed a total of 11,892 measurements. Of these, 3713 were from the sagittal plane: 1298 of flexoextension, 1394 of flexion, 1021 of extension. The differences in flexoextension were those shown in Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7, the differences in flexion were those shown in Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13 and the differences in extension were those shown in Figure 14, Figure 15, Figure 16, Figure 17, Figure 18 and Figure 19.

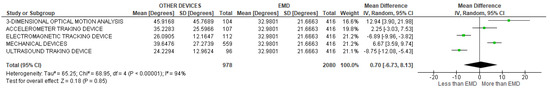

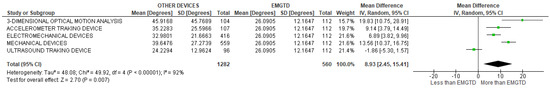

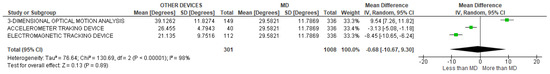

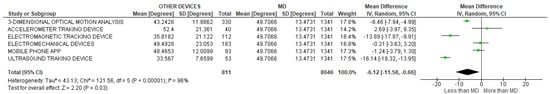

Figure 2.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing measured rFE of all other tool types with mechanical devices.

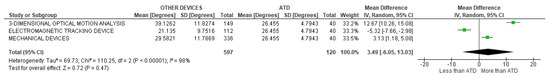

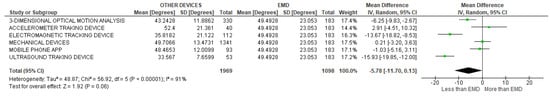

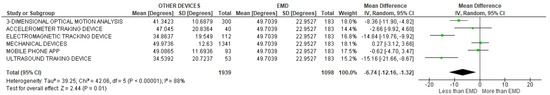

Figure 3.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing measured rFE of all other tool types with electromechanical devices.

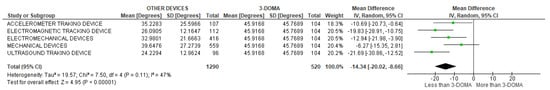

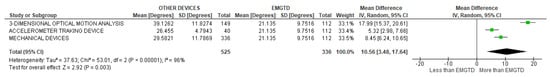

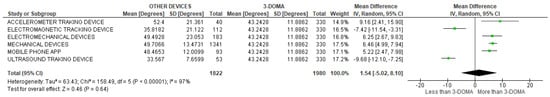

Figure 4.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing measured rFE of all other tool types with three-dimensional optical motion analysis.

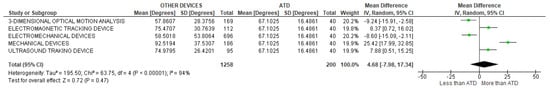

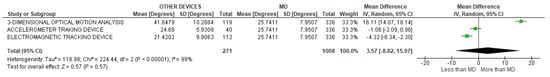

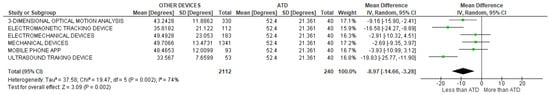

Figure 5.

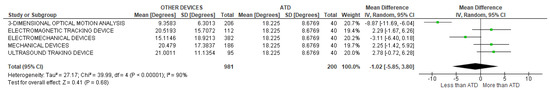

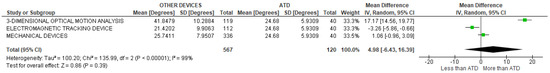

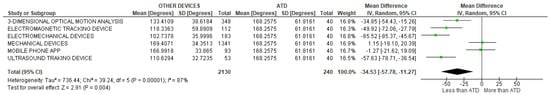

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing measured rFE of all other tool types with accelerometer tracking devices.

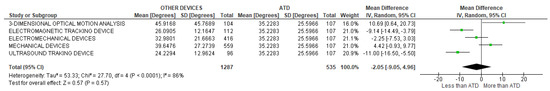

Figure 6.

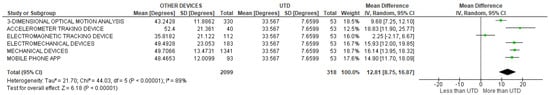

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing measured rFE of all other tool types with ultrasound tracking devices.

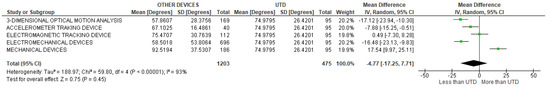

Figure 7.

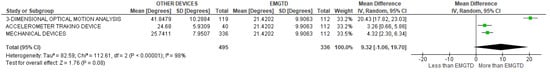

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing measured rFE of all other tool types with electromagnetic tracking devices.

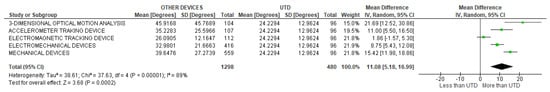

Figure 8.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing measured rF of all other tool types with mechanical devices.

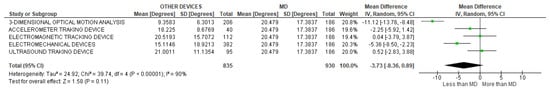

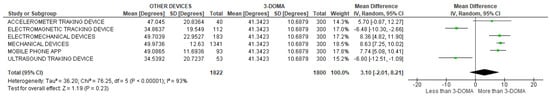

Figure 9.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing measured rF of all other tool types with electromechanical devices.

Figure 10.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing measured rF of all other tool types with three-dimensional optical motion analysis.

Figure 11.

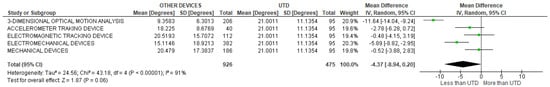

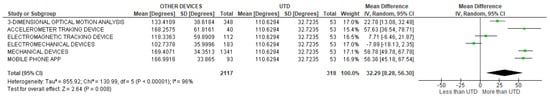

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing measured rF of all other tool types with accelerometer tracking devices.

Figure 12.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing measured rF of all other tool types with ultrasound tracking devices.

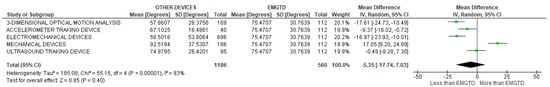

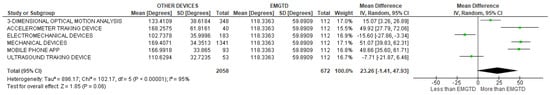

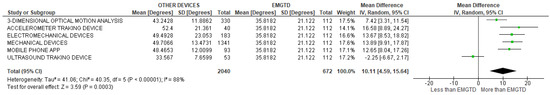

Figure 13.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing measured rF of all other tool types with electromagnetic tracking devices.

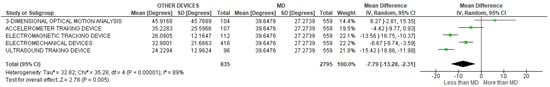

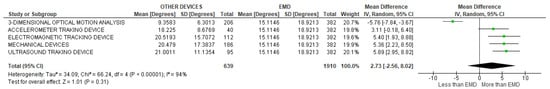

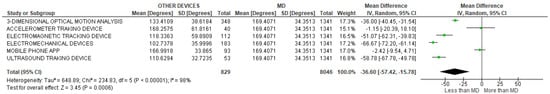

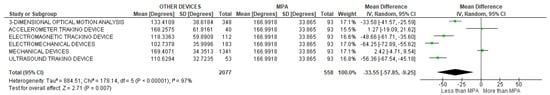

Figure 14.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing measured rE of all other tool types with mechanical devices.

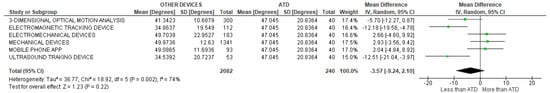

Figure 15.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing measured rE of all other tool types with electromechanical devices.

Figure 16.

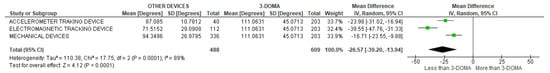

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing measured rE of all other tool types with three-dimensional optical motion analysis.

Figure 17.

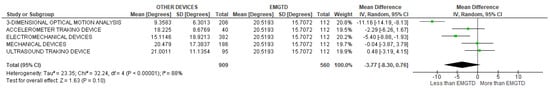

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing measured rE of all other tool types with accelerometer tracking devices.

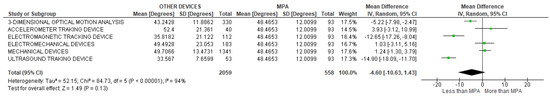

Figure 18.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing measured rE of all other tool types with ultrasound tracking devices.

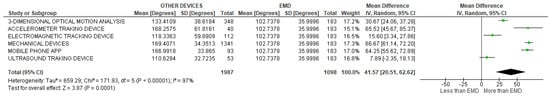

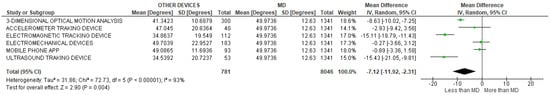

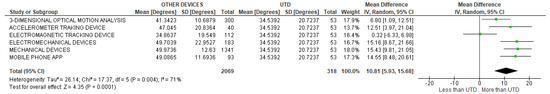

Figure 19.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing measured rE of all other tool types with electromagnetic tracking devices.

Of 11,892 measurements, 1735 were from the coronal plane: 491 of side-to-side lateral flexion, 637 of right lateral flexion, 607 of left lateral flexion. The differences in side-to-side lateral flexion were those shown in Figure 20, Figure 21, Figure 22 and Figure 23, the differences in right lateral flexion were those shown in Figure 24, Figure 25, Figure 26 and Figure 27, and the differences in left lateral flexion were those shown in Figure 28, Figure 29, Figure 30 and Figure 31.

Figure 20.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing rSSLF of all other tool types with mechanical devices.

Figure 21.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing rSSLF of all other tool types with three-dimensional optical motion analysis.

Figure 22.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing rSSLF of all other tool types with accelerometer tracking devices.

Figure 23.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing rSSLF of all other tool types with electromagnetic tracking devices.

Figure 24.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing rRLF of all other tool types with mechanical devices.

Figure 25.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing rRLF of all other tool types with three-dimensional optical motion analysis.

Figure 26.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing rRLF of all other tool types with accelerometer tracking devices.

Figure 27.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing rRLF of all other tool types with electromagnetic tracking devices.

Figure 28.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing rLLF of all other tool types with mechanical devices.

Figure 29.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing rLLF of all other tool types with three-dimensional optical motion analysis.

Figure 30.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing rLLF of all other tool types with accelerometer tracking devices.

Figure 31.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing rLLF of all other tool types with electromagnetic tracking devices.

A total of 6444 measurements were from the transversal plane: 2170 of side to side rotation, 2152 of right rotation and 2122 of left rotation, the differences in side to side rotation were those shown in Figure 32, Figure 33, Figure 34, Figure 35, Figure 36, Figure 37 and Figure 38, the differences in right rotation were those shown in Figure 39, Figure 40, Figure 41, Figure 42, Figure 43, Figure 44 and Figure 45 and the differences in left rotation were those shown in Figure 46, Figure 47, Figure 48, Figure 49, Figure 50, Figure 51 and Figure 52.

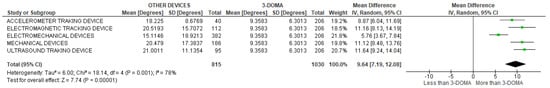

Figure 32.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing rSSR of all other tool types with mechanical devices.

Figure 33.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing rSSR of all other tool types with electromechanical devices.

Figure 34.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing rSSR of all other tool types with three-dimensional optical motion analysis devices.

Figure 35.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing rSSR of all other tool types with accelerometer tracking devices.

Figure 36.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing rSSR of all other tool types with ultrasound tracking devices.

Figure 37.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing rSSR of all other tool types with electromagnetic tracking devices.

Figure 38.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing rSSR of all other tool types with mobile phone applications.

Figure 39.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing rRR of all other tool types with mechanical devices.

Figure 40.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing rRR of all other tool types with electromechanical devices.

Figure 41.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing rRR of all other tool types with three-dimensional optical motion analysis.

Figure 42.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing rRR of all other tool types with accelerometer tracking devices.

Figure 43.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing rRR of all other tool types with ultrasound tracking devices.

Figure 44.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing rRR of all other tool types with electromagnetic tracking devices.

Figure 45.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing rRR of all other tool types with mobile phone applications.

Figure 46.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing rLR of all other tool types with mechanical devices.

Figure 47.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing rLR of all other tool types with electromechanical devices.

Figure 48.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing rLR of all other tool types with three-dimensional optical motion analysis.

Figure 49.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing rLR of all other tool types with accelerometer tracking devices.

Figure 50.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing rLR of all other tool types with ultrasound tracking devices.

Figure 51.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing rLR of all other tool types with electromagnetic tracking devices.

Figure 52.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing rLR of all other tool types with mobile phone applications.

Grouping tools according to the type of position measure we summarized and analyzed a total of 12,092 measurements. Of these, 3713 were from the sagittal plane and 1935 from the coronal plane. The differences in flexoextension, flexion, extension, side to side lateral flexion, right lateral flexion, and left lateral flexion, were those shown in Table 9.

Table 9.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing standing position with sitting position in rFE, rF, rE, rssLF, rRLF and rLLF.

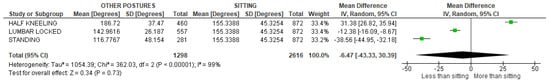

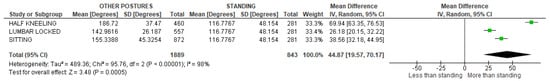

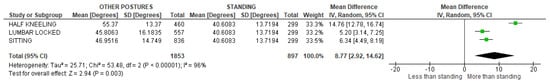

In the transversal plane, we analyze a total of 6444 measurements, the differences in side-to-side rotation were those shown in Figure 53, Figure 54, Figure 55 and Figure 56, the differences in right rotation were those shown in Figure 57, Figure 58, Figure 59 and Figure 60 and the differences in left rotation were those shown in Figure 61, Figure 62, Figure 63 and Figure 64.

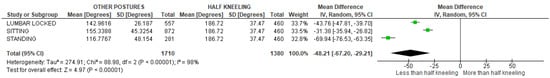

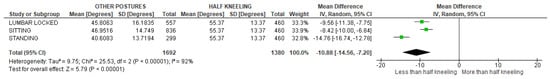

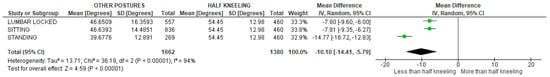

Figure 53.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing the measured rSSR of the other positions with the sitting position.

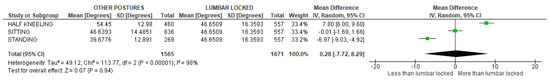

Figure 54.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing the measured rSSR of the other positions with the standing position.

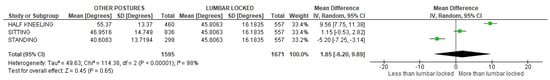

Figure 55.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing the measured rSSR of the other positions with the half kneeling position.

Figure 56.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing the measured rSSR of the other positions with the lumbar locked position.

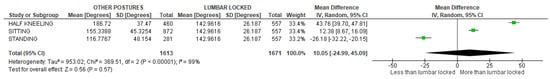

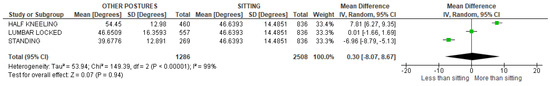

Figure 57.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing the measured rRR of the other positions with the sitting position.

Figure 58.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing the measured rRR of the other positions with the standing position.

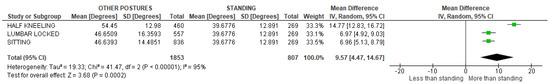

Figure 59.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing the measured rRR of the other positions with the half kneeling position.

Figure 60.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing the measured rRR of the other positions with the lumbar locked position.

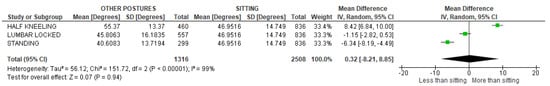

Figure 61.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing the measured rLR of the other positions with the sitting position.

Figure 62.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing the measured rLR of the other positions with the standing position.

Figure 63.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing the measured rLR of the other positions with the half kneeling position.

Figure 64.

Mean, standard deviation, total of measures and 95% confidence interval comparing the measured rLR of the other positions with the lumbar locked position.

4. Discussion

The current study aimed to analyze the different tools used nowadays to measure the physiological movements of the dorsal spine reviewing their different protocols and measurements.

Interpreting the results of the meta-analyses of the measurements based on the type of measurement tool used, the values obtained from the flexo-extensions, the measurement grades of the MDs and ATDs presented significant differences for the rest of the measuring devices used, whereas the measurement grades of the EMDs and 3-DOMA only had significant similar results concerning each other. Similarly, UTD and EMGTD values were only significantly similar to each other. When observing the results obtained in flexion, the MD grades had similar significant results with the values of the 3-DOMA and ATD, the rest of the values were significantly different. The EMD values only had significantly similar results with the ATD, similarly, the UTD and EMGTD values only had significantly similar results with each other. Finalizing the values of the sagittal plane, in the extension values, the MDs measurements had similar significant results with the ATD, UTD, and EMGTD. The results measured with the EMD were only significantly similar to the values of the ATD, whereas the values of the 3-DOMA had significant differences with the rest of the measuring devices used. The ATDs had similar results with the MD, EMD, UTD, and EMGTD, the values obtained with the UTD in addition to having similar significant results with the MD and ATD also had them with the EMGTD measurements. In all the values of the coronal plane movements (side-to-side lateral flexion, right lateral flexion, and left lateral flexion) obtained with the different types of tools, there were significant differences, except with the values obtained in the left lateral flexion with the MD and ATD, which had similar significant results. In the transverse plane, in the values obtained in the side-to-side rotation, the measurements obtained with the MDs had similar significant results with the ATDs and MPAs, on the other hand, the values of the EMDs were significantly similar only to the STDs. The 3-DOMA values were not significantly similar to the rest of the tool types. The ATD had significantly similar results with the MD and MPA, the EMGTD only had significantly similar measurements with the UTD. On the other hand, in the values obtained in the right rotation measurements, the MD had similar significant results with the EMD, ATD, and MPA, and it was reciprocal in the values of the EMD, ATD, and MPA. Similar to the side-to-side rotation measurements, the 3-DOMA values were not significantly similar to the other tool types. The UTD and EMGTD measurements only had significantly similar results with each other. The similarities in the left rotation measurements obtained with the different tool types were similar to those of the right rotation, except that the 3-DOMA values were significantly related to those of the ATDs.

Interpreting the results of the meta-analyses of the measurements based on the type of posture, all movements measured were significantly different, except for right and left rotations measured in the seated and locked lumbar postures, which had similar significant results, this indicates that the positions adopted in the measurements are a key factor that makes the measurements differ from each other even when measuring the same movements.

Another reason that shows that the results were very different from each other is the I2, since all the results were around 75%, which shows that in the comparisons of the different physiological movements of the dorsal spine according to the position and type of tool, the measurements were very irregular from each other, having a large statistical heterogeneity.

Most of the measurements of the different physiological movements of the dorsal spine depending on the type of instrument used, which should give similar results, vary in a high percentage since it has been shown that in a statistically significant way there are considerable differences between many of them, being the measurements very irregular; even higher is the difference depending on the type of position used at the time of measurement. We have been able to verify that there are a large number of tools to measure the physiological movements of the spine, each of these tools has its different protocol and establishes its initial positions that the subjects must have to perform the measurement. Even so, if the tools were as sensitive and specific as possible, there would be no differences between them, what we have been able to verify through this study is that there are, so we should act based on this and think together about possible solutions to this problem.

No tool was found that measures the different planes of movement of the cervical, dorsal and lumbar regions. Of all the tools referenced, only some 3-DOMA [25,26,64,67], two ATD [53,62] and one EMGTD [30,35,48] (the FASTRAK) measured the three planes in the dorsal spine, so the presence of a tool capable of measuring flexion-extensions, lateral inclinations and rotations are not very common either.

The main long-term objective to solve these differences in measurements would be to perform a general protocol to try to eliminate these measurement biases but to do this, it would be important to perform a large-scale experimental study in which the physiological movements of the spine will be measured using the different types of existing tools in the same subjects. In that investigation, we will measure using the performance protocol of each tool, to corroborate the measurement differences that arise in this study and if so, to be able to establish a general protocol in which these measurement differences will be reduced.

If this is achieved, it could even be decisive in the joint assessment of the movement of the thoracic spine with the presence of pain, seeing how this variable can affect mobility, breathing and the different factors involved in the dorsal spine complex in the same way that other studies have assessed whether the presence of pain in the shoulder causes limitations in daily life [69] or whether cervical or lumbar pain can cause restrictions at work [71]. Another very interesting factor to take into account is that if we manage to make the tools as specific and sensitive as possible, they could even serve to prevent some spinal pathologies, such as osteoarthritis, by studying this pathology and checking whether they cause mobility restrictions in the initial phases.

One of the main limitations of this study is that by grouping and extracting data from the different types of tools used in the measurements of physiological movements of the dorsal spine, many studies do not distinguish between men or women, nowadays there is evidence that mobility and physiological ranges are different between male and female [71,72,73], so measurements should be discerned according to the gender of the subject.

5. Conclusions

The data obtained, collected and analyzed from the different physiological movements of the dorsal spine indicate that they are very irregular, depending on the type of tool used, since each of them has its action protocol. One of the most important parts of the performance protocols is the initial measurement positions adopted by the subjects. In this study, it has been shown that although the tools measure the same movement, the position adopted by the subjects ensure that the measurements do not coincide and are different. For this reason, it is important to establish a standardized performance protocol unifying initial measurement positions to try to avoid the risks of measurement bias.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.E.-G.; methodology, P.E.-G.; software, P.E.-G.; validation, P.E.-G., E.A.S.-R. and J.H.V.; formal analysis, P.E.-G.; investigation, P.E.-G.; resources, P.E.-G.; writing—original draft preparation, P.E.-G.; writing—review and editing, P.E.-G.; visualization, P.E.-G., E.A.S.-R. and J.H.V.; supervision, E.A.S.-R. and J.H.V.; project administration, P.E.-G., E.A.S.-R. and J.H.V.; funding acquisition, E.A.S.-R. and J.H.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The publication of this work has been financed by the European University of Madrid C/ Tajo s/n, 28670 Villaviciosa de Odón, Madrid, Spain.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors certify that they have no affiliations with or financial involvement in any organization or entity with a direct financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in the article.

Appendix A. Search String

“(((((((((((((thoracic) AND (tool)) AND (range of motion)) OR (((thoracic) AND (tool)) AND (movement))) OR (((thoracic) AND (tool)) AND (kinematic))) OR (((thoracic) AND (tool)) AND (mobility))) OR (((thoracic) AND (tool)) AND (motion))) OR (((thoracic) AND (tool)) AND (flexion))) OR (((thoracic) AND (tool)) AND (extension))) OR (((thoracic) AND (tool)) AND (bending))) OR (((thoracic) AND (tool)) AND (rotation))) OR (((((((((((thoracic) AND (device)) AND (range of motion)) OR (((thoracic) AND (device)) AND (movement))) OR (((thoracic) AND (device)) AND (kinematic))) OR (((thoracic) AND (device)) AND (mobility))) OR (((thoracic) AND (device)) AND (motion))) OR (((thoracic) AND (device)) AND (flexion))) OR (((thoracic) AND (device)) AND (extension))) OR (((thoracic) AND (device)) AND (bending))) OR (((thoracic) AND (device)) AND (rotation)))) OR (((((((((((range of motion) AND (thoracic)) AND (system)) OR (((thoracic) AND (system)) AND (movement))) OR (((thoracic) AND (system)) AND (kinematic))) OR (((thoracic) AND (system)) AND (mobility))) OR (((thoracic) AND (system)) AND (motion))) OR (((thoracic) AND (system)) AND (flexion))) OR (((thoracic) AND (system)) AND (extension))) OR (((thoracic) AND (system)) AND (bending))) OR (((thoracic) AND (system)) AND (rotation)))) OR ((((((((((((“Range of Motion, Articular”[Mesh]) AND “Thoracic Vertebrae”[Mesh]) AND “Weights and Measures”[Mesh]) OR (((range of motion) AND (thoracic)) AND (measure))) OR (((movement) AND (thoracic)) AND (measure))) OR (((kinematic) AND (thoracic)) AND (measure))) OR (((mobility) AND (thoracic)) AND (measure))) OR (((motion) AND (thoracic)) AND (measure))) OR (((flexion) AND (thoracic)) AND (measure))) OR (((extension) AND (thoracic)) AND (measure))) OR (((bending) AND (thoracic)) AND (measure))) OR (((rotation) AND (thoracic)) AND (measure)))”.

Appendix B

Table A1.

PEDro Scale.

Table A1.

PEDro Scale.

| Study | Score | Methodological Quality | Number of Items of PEDro Scale | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |||

| Holmström E. et al., 2005 [33] | 8 | Good | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Battaglia G. et al., 2014 [49] | 8 | Good | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Çelenay ŞT. et al., 2015 [51] | 9 | Excellent | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

Appendix C

Table A2.

MINORS scale.

Table A2.

MINORS scale.

| Study | Score | Methodological Quality | Number of Item of MINORS Scale | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |||

| O’Gorman et al., 1987 [27] | 18/24 | Good | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Mellin G. et al., 1991 [28] | 14/16 | Good | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | - | - | - | - |

| Crawford H.J. et al., 1993 [29] | 21/24 | Good | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Willems J.M. et al., 1996 [30] | 15/16 | Excellent | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| Gilleard W. et al., 2002 [25] | 21/24 | Good | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Mannion A.F. et al., 2004 [31] | 14/16 | Good | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | - | - | - | - |

| Post R.B. et al., 2004 [32] | 15/16 | Excellent | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| Edmondston S.J. et al., 2007 [34] | 16/16 | Excellent | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | - | - | - | - |

| Tedereko P. et al., 2007 [26] | 14/16 | Good | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | - | - | - | - |

| Hsu C.J. et al., 2008 [35] | 14/16 | Good | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | - | - | - | - |

| Mika A. et al., 2009 [36] | 23/24 | Excellent | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Kasukawa Y. et al., 2010 [37] | 19/24 | Good | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Theisen C. et al., 2010 [38] | 19/24 | Good | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Heneghan N.R. et al., 2010 [39] | 14/16 | Good | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | - | - | - | - |

| Imagama S. et al., 2011 [40] | 14/16 | Good | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | - | - | - | - |

| Edmondston S.J. et al., 2011 [41] | 14/16 | Good | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | - | - | - | - |

| Edmondston S.J et al., 2012 [42] | 14/16 | Good | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | - | - | - | - |

| Fölsch C. et al., 2012 [43] | 14/16 | Good | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | - | - | - | - |

| Johnson K.D. et al., 2012 [44] | 14/16 | Good | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | - | - | - | - |

| Edmondston S.J. et al., 2012 [45] | 14/16 | Good | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | - | - | - | - |

| Wang H.J. et al., 2012 [46] | 19/24 | Good | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Benjamin-Hidalgo P.E. et al., 2012 [47] | 20/24 | Good | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Tsang S.M. et al., 2013 [48] | 14/16 | Good | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | - | - | - | - |

| Wirth B. et al., 2014 [50] | 22/24 | Excellent | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Talukdar K. et al., 2015 [52] | 14/16 | Good | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | - | - | - | - |

| Alqhtani R.S. et al., 2015 [53] | 14/16 | Good | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | - | - | - | - |

| Hajibozorgi M. et al., 2016 [15] | 14/16 | Good | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | - | - | - | - |

| Schinkel-Ivy A. et al., 2016 [54] | 14/16 | Good | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | - | - | - | - |

| Furness J. et al., 2016 [55] | 20/24 | Good | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Mazzone B. et al., 2016 [56] | 24/24 | Excellent | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Zafereo J. et al., 2016 [57] | 16/16 | Excellent | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | - | - | - | - |

| Morais N. et al., 2016 [58] | 23/24 | Excellent | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Rast F. et al., 2016 [59] | 21/24 | Good | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Ishikawa Y. et al., 2017 [60] | 22/24 | Excellent | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Bucke J. et al., 2017 [11] | 16/16 | Excellent | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | - | - | - | - |

| Roghani T. et al., 2017 [61] | 22/24 | Excellent | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Hwang D. et al., 2017 [8] | 14/16 | Good | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | - | - | - | - |

| Narimani M. et al., 2018 [62] | 14/16 | Good | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | - | - | - | - |

| Heneghan N.R. et al., 2018 [63] | 22/24 | Excellent | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Mousavi S.J. et al., 2018 [64] | 14/16 | Good | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | - | - | - | - |

| Furness J. et al., 2018 [65] | 22/24 | Excellent | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Beaudette S.M. et al., 2019 [66] | 23/24 | Excellent | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Schinkel-Ivy A. et al., 2019 [67] | 15/16 | Excellent | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| Welbeck A.N. Et al., 2019 [68] | 22/24 | Excellent | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Hunter D.J. et al., 2020 [69] | 24/24 | Excellent | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

References

- Kubas, C.; Chen, Y.-W.; Echeverri, S.; McCann, S.L.; Denhoed, M.J.; Walker, C.J.; Kennedy, C.N.; Reid, W.D. Reliability and Validity of Cervical Range of Motion and Muscle Strength Testing. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2017, 31, 1087–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shum, G.L.K.; Crosbie, J.; Lee, R.Y.W. Movement coordination of the lumbar spine and hip during a picking up activity in low back pain subjects. Eur. Spine J. 2006, 16, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, S.; Manni, T.; Bonetti, F.; Villafañe, J.H.; Vanti, C. A literature review of clinical tests for lumbar instability in low back pain: Validity and applicability in clinical practice. Chiropr. Man. Ther. 2015, 23, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bissolotti, L.; Gobbo, M.; Villafañe, J.H.; Negrini, S. Spinopelvic balance: New biomechanical insights with clinical implications for Parkinson’s disease. Eur. Spine J. 2014, 23, 576–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrini, S.; Imperio, G.; Villafañe, J.H.; Negrini, F.; Zaina, F. Systematic reviews of physical and rehabilitation medicine Cochrane contents. Part 1. Disabilities due to spinal disorders and pain syndromes in adults. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2013, 49, 597–610. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, N.; An, H.; Lim, T.; Fujiwara, A.; Jeon, C.; Haughton, V. The relationship between disc degeneration and flexibility of the lumbar spine. Spine J. 2001, 1, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, I.A.; Moll, J.M.; Wright, V. Chest and spinal mobility in physiotherapists: An objective clinical study. Physiotherapy 1974, 60, 37–39. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, D.; Lee, J.H.; Moon, S.; Park, S.W.; Woo, J.; Kim, C. The reliability of the nonradiologic measures of thoracic spine rotation in healthy adults. Phys. Ther. Rehabil. Sci. 2017, 6, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyytiäinen, K.; Salminen, J.; Suvitie, T.; Wickström, G.; Pentti, J. Reproducibility of nine tests to measure spinal mobility and trunk muscle strength. Scand. J. Rehabil. Med. 1991, 23, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, K.D.; Grindstaff, T.L. Thoracic rotation measurement techniques: Clinical commentary. N. Am. J. Sports Phys. Ther. NAJSPT 2010, 5, 252–256. [Google Scholar]

- Bucke, J.; Spencer, S.; Fawcett, L.; Sonvico, L.; Rushton, A.; Heneghan, N.R. Validity of the Digital Inclinometer and iPhone When Measuring Thoracic Spine Rotation. J. Athl. Train. 2017, 52, 820–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seichert, N.; Baumann, M.; Senn, E.; Zuckriegl, H. The “back mouse”—An analog-digital measuring device to record the sagittal outline of the back. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Kurortmed. 2008, 4, 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, M.; Smith, A.; Straker, L.; Coleman, J.; O’Sullivan, P. Reliability of sagittal photographic spinal posture assessment in adolescents. Adv. Physiother. 2009, 10, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troke, M.; Moore, A.; Cheek, E. Intra-operator and inter-operator reliability of the OSI CA 6000 Spine Motion Analyzer with a new skin fixation system. Man. Ther. 1996, 1, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajibozorgi, M.; Arjmand, N. Sagittal range of motion of the thoracic spine using inertial tracking device and effect of measurement errors on model predictions. J. Biomech. 2016, 49, 913–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heneghan, N.R.; Hall, A.; Hollands, M.; Balanos, G.M. Stability and intra-tester reliability of an in vivo measurement of thoracic axial rotation using an innovative methodology. Man. Ther. 2009, 14, 452–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearcy, M.; Hindle, R. New method for the non-invasive three-dimensional measurement of human back movement. Clin. Biomech. 1989, 4, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutton, B.; Catalá-López, F.; Moher, D. La extensión de la declaración PRISMA para revisiones sistemáticas que incorporan metaanálisis en red: PRISMA-NMA. Med. Clin. 2016, 147, 262–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews [Internet]. 2018. Available online: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/ (accessed on 18 July 2018).

- Verhagen, A.P.; De Vet, H.C.; De Bie, R.A.; Kessels, A.G.; Boers, M.; Bouter, L.M.; Knipschild, P.G. The Delphi list: A criteria list for quality as-sessment of randomized clinical trials for conducting systematic reviews developed by Delphi consensus. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1998, 51, 1235–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slim, K.; Nini, E.; Forestier, D.; Kwiatkowski, F.; Panis, Y.; Chipponi, J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (MINORS ): Development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J. Surg. 2003, 73, 712–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villafañe, J.; Pedersini, P.; Bertozzi, L.; Drago, L.; Fernandez-Carnero, J.; Bishop, M.; Berjano, P. Exploring the relationship between chronic pain and cortisol levels in subjects with osteoarthritis: Results from a systematic review of the literature. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2020, 28, 572–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.; Thomas, J. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, 2nd ed.; Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M., Welch, V., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gilleard, W.; Crosbie, J.; Smith, R. Effect of pregnancy on trunk range of motion when sitting and standing. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2002, 81, 1011–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tederko, P.; Krasuski, M.; Maciejasz, P. Restrainer of pelvis and lower limbs in thoracic and lumbar range of motion measurement. Ortop. Traumatol. Rehabil. 2007, 9, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- O’Gorman, H.; Jull, G. Thoracic kyphosis and mobility: The effect of age. Physiother. Pract. 1987, 3, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellin, G.; Kiiski, R.; Weckström, A. Effects of Subject Position on Measurements of Flexion, Extension, and Lateral Flexion of the Spine. Spine 1991, 16, 1108–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, H.J.; Jull, G.A. The influence of thoracic posture and movement on range of arm elevation. Physiother. Theory Pract. 1993, 9, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willems, J.; Jull, G.; Ng, J.-F. An in vivo study of the primary and coupled rotations of the thoracic spine. Clin. Biomech. 1996, 11, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannion, A.F.; Knecht, K.; Balaban, G.; Dvorak, J.; Grob, D. A new skin-surface device for measuring the curvature and global and segmental ranges of motion of the spine: Reliability of measurements and comparison with data reviewed from the literature. Eur. Spine J. 2004, 13, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, R.B.; Leferink, V.J.M. Spinal mobility: Sagittal range of motion measured with the Spinal Mouse, a new non-invasive device. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2004, 124, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmström, E.; Ahlborg, B. Morning warming-up exercise—Effects on musculoskeletal fitness in construction workers. Appl. Ergon. 2005, 36, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edmondston, S.J.; Aggerholm, M.; Elfving, S.; Flores, N.; Ng, C.; Smith, R.; Netto, K. Influence of Posture on the Range of Axial Rotation and Coupled Lateral Flexion of the Thoracic Spine. J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 2007, 30, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, C.-J.; Chang, Y.-W.; Chou, W.-Y.; Chiou, C.-P.; Chang, W.-N.; Wong, C.-Y. Measurement of spinal range of motion in healthy individuals using an electromagnetic tracking device. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2008, 8, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mika, A.; Fernhall, B.; Mika, P. Association between moderate physical activity, spinal motion and back muscle strength in postmenopausal women with and without osteoporosis. Disabil. Rehabil. 2009, 31, 734–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasukawa, Y.; Miyakoshi, N.; Hongo, M.; Ishikawa, Y.; Noguchi, H.; Kamo, K.; Sasaki, H.; Murata, K.; Shimada, Y. Relationships between falls, spinal curvature, spinal mobility and back extensor strength in elderly people. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 2009, 28, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theisen, C.; van Wagensveld, A.; Timmesfeld, N.; Efe, T.; Heyse, T.J.; Fuchs-Winkelmann, S.; Schofer, M.D. Co-occurrence of outlet impingement syndrome of the shoulder and restricted range of motion in the thoracic spine—A prospective study with ultrasound-based motion analysis. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2010, 11, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heneghan, N.R.; Balanos, G.M. Soft tissue artefact in the thoracic spine during axial rotation and arm elevation using ultrasound imaging: A descriptive study. Man. Ther. 2010, 15, 599–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imagama, S.; Matsuyama, Y.; Hasegawa, Y.; Sakai, Y.; Ito, Z.; Ishiguro, N.; Hamajima, N. Back muscle strength and spinal mo-bility are predictors of quality of life in middle-aged and elderly males. Eur. Spine J. 2011, 20, 954–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondston, S.; Waller, R.; Vallin, P.; Holthe, A.; Noebauer, A.; King, E. Thoracic Spine Extension Mobility in Young Adults: Influence of Subject Position and Spinal Curvature. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2011, 41, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondston, S.J.; Christensen, M.M.; Keller, S.; Steigen, L.B.; Barclay, L. Functional Radiographic Analysis of Thoracic Spine Extension Motion in Asymptomatic Men. J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 2012, 35, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fölsch, C.; Schlögel, S.; Lakemeier, S.; Wolf, U.; Timmesfeld, N.; Skwara, A. Test-Retest Reliability of 3D Ultrasound Measurements of the Thoracic Spine. PM&R 2012, 4, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.D.; Kim, K.-M.; Yu, B.-K.; Saliba, S.; Grindstaff, T.L. Reliability of Thoracic Spine Rotation Range-of-Motion Measurements in Healthy Adults. J. Athl. Train. 2012, 47, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edmondston, S.; Ferguson, A.; Ippersiel, P.; Ronningen, L.; Sodeland, S.; Barclay, L. Clinical and Radiological Investigation of Thoracic Spine Extension Motion During Bilateral Arm Elevation. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2012, 42, 861–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.J.; Giambini, H.; Zhang, W.J.; Ye, G.H.; Zhao, C.; An, K.N.; Li, Y.K.; Lan, W.R.; Li, J.Y.; Jiang, X.S.; et al. A Modified Sagittal Spine Postural Classifi-cation and Its Relationship to Deformities and Spinal Mobility in a Chinese Osteoporotic Population. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e38560. [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo, B.; Gilliaux, M.; Poncin, W.; Detrembleur, C. Reliability and validity of a kinematic spine model during active trunk movement in healthy subjects and patients with chronic non-specific low back pain. J. Rehabil. Med. 2012, 44, 756–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsang, S.M.H.; Szeto, G.P.Y.; Lee, R.Y.W. Normal kinematics of the neck: The interplay between the cervical and thoracic spines. Man. Ther. 2013, 18, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, G.; Bellafiore, M.; Caramazza, G.; Paoli, A.; Bianco, A.; Palma, A. Changes in spinal range of motion after a flexibility training program in elderly women. Clin. Interv. Aging 2014, 9, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, B.; Amstalden, M.; Perk, M.; Boutellier, U.; Humphreys, B. Respiratory dysfunction in patients with chronic neck pain—Influence of thoracic spine and chest mobility. Man. Ther. 2014, 19, 440–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elenay, Ş.T.; Kaya, D.Ö.; Özüdogbreveru, A. Spinal postural training: Comparison of the postural and mobility effects of electrotherapy, exercise, biofeedback trainer in addition to postural education in university students. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 2015, 28, 135–144. [Google Scholar]

- Talukdar, K.; Cronin, J.; Zois, J.; Sharp, A.P. The Role of Rotational Mobility and Power on Throwing Velocity. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2015, 29, 905–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Alqhtani, R.S.; Jones, M.D.; Theobald, P.S.; Williams, J.M. Reliability of an Accelerometer-Based System for Quantify-ing Multiregional Spinal Range of Motion. J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 2015, 38, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schinkel-Ivy, A.; Drake, J.D. Breast size impacts spine motion and postural muscle activation. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 2016, 29, 741–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furness, J.; Climstein, M.; Sheppard, J.M.; Abbott, A.; Hing, W. Clinical methods to quantify trunk mobility in an elite male surfing population. Phys. Ther. Sport 2015, 19, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzone, B.; Wood, R.; Gombatto, S. Spine Kinematics During Prone Extension in People With and Without Low Back Pain and Among Classification-Specific Low Back Pain Subgroups. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2016, 46, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zafereo, J.; Wang-Price, S.; Brown, J.; Carson, E. Reliability and Comparison of Spinal End-Range Motion Assessment Using a Skin-Surface Device in Participants with and without Low Back Pain. J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 2016, 39, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morais, N.; Cruz, J.; Marques, A. Posture and mobility of the upper body quadrant and pulmonary function in COPD: An exploratory study. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2016, 20, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rast, F.M.; Graf, E.; Meichtry, A.; Kool, J.; Bauer, C.M. Between-day reliability of three-dimensional motion analysis of the trunk: A comparison of marker based protocols. J. Biomech. 2016, 49, 807–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, Y.; Miyakoshi, N.; Hongo, M.; Kasukawa, Y.; Kudo, D.; Shimada, Y. Relationships among spinal mobility and sagittal alignment of spine and lower extremity to quality of life and risk of falls. Gait Posture 2017, 53, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roghani, T.; Zavieh, M.K.; Rahimi, A.; Talebian, S.; Manshadi, F.D.; Baghban, A.A.; King, N.; Katzman, W. The Reliability of Standing Sagittal Measurements of Spinal Curvature and Range of Motion in Older Women With and Without Hyperkyphosis Using a Skin-Surface Device. J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 2017, 40, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narimani, M.; Arjmand, N. Three-dimensional primary and coupled range of motions and movement coordination of the pelvis, lumbar and thoracic spine in standing posture using inertial tracking device. J. Biomech. 2018, 69, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heneghan, N.R.; Baker, G.; Thomas, K.; Falla, D.; Rushton, A. What is the effect of prolonged sitting and physical activity on thoracic spine mobility? An observational study of young adults in a UK university setting. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e019371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mousavi, S.J.; Tromp, R.; Swann, M.C.; White, A.P.; Anderson, D.E. Between-session reliability of opto-electronic motion capture in measuring sagittal posture and 3-D ranges of motion of the thoracolumbar spine. J. Biomech. 2018, 79, 248–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furness, J.; Schram, B.; Cox, A.J.; Anderson, S.L.; Keogh, J. Reliability and concurrent validity of the iPhone® Compass application to measure thoracic rotation range of motion (ROM) in healthy participants. PeerJ 2018, 6, e4431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaudette, S.M.; Zwambag, D.P.; Graham, R.B.; Brown, S.H. Discriminating spatiotemporal movement strategies during spine flexion-extension in healthy individuals. Spine J. 2019, 19, 1264–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schinkel-Ivy, A.; Drake, J.D. Interaction Between Thoracic Movement and Lumbar Spine Muscle Activation Patterns in Young Adults Asymptomatic for Low Back Pain: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 2019, 42, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welbeck, A.N.; Amilo, N.R.; Le, D.T.; Killelea, C.M.; Kirsch, A.N.; Zarzour, R.H. Examining the link between thoracic rotation and scapular dyskinesis and shoulder pain amongst college swimmers. Phys. Ther. Sport 2019, 40, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boake, R.B.; Childs, K.T.; Soules, D.T.; Zervos, L.D.; Vincent, I.J.; MacDermid, C.J. Rasch analysis of The Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI) in a postrepair rotator cuff sample. J. Hand Ther. 2021, 34, 612–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasukawa, Y.; Miyakoshi, N.; Hongo, M.; Ishikawa, Y.; Kudo, D.; Suzuki, M.; Mizutani, T.; Kimura, R.; Ono, Y.; Shimada, Y. Age-related changes in muscle strength and spinal kyphosis angles in an elderly Japanese population. Clin. Interv. Aging 2017, 12, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillastrini, P.; de Lima ESá Resende, F.; Banchelli, F.; Burioli, A.; Di Ciaccio, E.; Guccione, A.A.; Villafañe, J.H.; Vanti, C. Effectiveness of Global Postural Re-education in Patients with Chronic Nonspecific Neck Pain: Randomized Controlled Trial. Phys. Ther. 2016, 96, 1408–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asukai, M.; Fujita, T.; Suzuki, D.; Nishida, T.; Ohishi, T.; Matsuyama, Y. Sex-Related Differences in the Developmental Morphology of the Atlas: A Computed Tomography Study. Spine 2018, 43, 699–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degulmadi, D.; Dave, B.R.; Krishnan, A. Age- and sex-related changes in facet orientation and tropism in lower lumbar spine: An MRI study of 600 patients. Eur. Spine J. 2019, 28, 961–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).