Research on Design, Calibration and Real-Time Image Expansion Technology of Unmanned System Variable-Scale Panoramic Vision System

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. Panoramic Imaging Model

2.1.1. Pinhole Imaging Model

2.1.2. Unified Imaging Model of Homograph Matrix Central Catadioptric Sphere

2.1.3. Pixel Ray Model

2.1.4. Radial Distortion Model

2.1.5. Fisheye Camera Model

2.1.6. Taylor Series Model

2.1.7. Mei Camera Model

2.1.8. Other Camera Models

2.2. Panoramic Systems Calibration

2.2.1. Calibration Based on Point Projection

2.2.2. Calibration Based on Single Image Line Projection

2.2.3. Object Calibration Based on 2D Calibration

2.2.4. Object Calibration Based on 3D Calibration

2.2.5. Self-Calibration

2.2.6. Other

2.3. Distortion Correction of Panoramic Image

2.3.1. Image Distortion Correction Based on Polynomial Functions

2.3.2. Image Distortion Correction Based on Non-Polynomial Functions

2.4. Panoramic Image Expansion

2.4.1. Cylinder Expansion Algorithm

2.4.2. Perspective Expansion Algorithms

2.4.3. Approximate Expansion Algorithms of Concentric Rings

2.4.4. Optical Path Tracking Coordinate Mapping Expansion Algorithms

2.4.5. Look-Up Table Algorithm

- Research on improving the resolution of catadioptric panoramic vision systems. In order to take into account the high resolution and large field of view, whether the camera can only face one side of the reflector through the off-axis of the camera, which reduces the field of view, but improves the resolution, and then cooperates with the local movement of the optical systems to achieve fast conversion between large field of view and high resolution.

- Research on distortion correction and real-time expansion algorithm of catadioptric panoramic vision systems. At present, the related research of single-view catadioptric panoramic vision systems mainly focuses on imaging model and systems calibration. This is only a prerequisite to solve the problem of panoramic vision. In the end, it is hoped to use the advantages of single-view catadioptric panoramic vision systems to solve typical vision problems. Thus, panoramic expansion and image distortion correction have become the main issues that need to be studied in depth in panoramic vision technology.

- Only by lengthening the baseline length can the system obtain high-precision depth information, and lengthening the baseline will inevitably increase the volume of the panoramic vision systems, which goes against the trend of systems miniaturization.

- The image resolution of catadioptric panoramic vision systems is unevenly distributed, the pixels near the center of the circle are more concentrated, the resolution is higher, the pixels near the edge are less, and the resolution is lower. The obstacles in the environment are in the catadioptric binocular stereo panoramic vision. In panoramic vision system, obstacles occupy different pixel values in two panoramic vision systems, which leads to stereo matching error.

3. Architecture Design and Theoretical Analysis

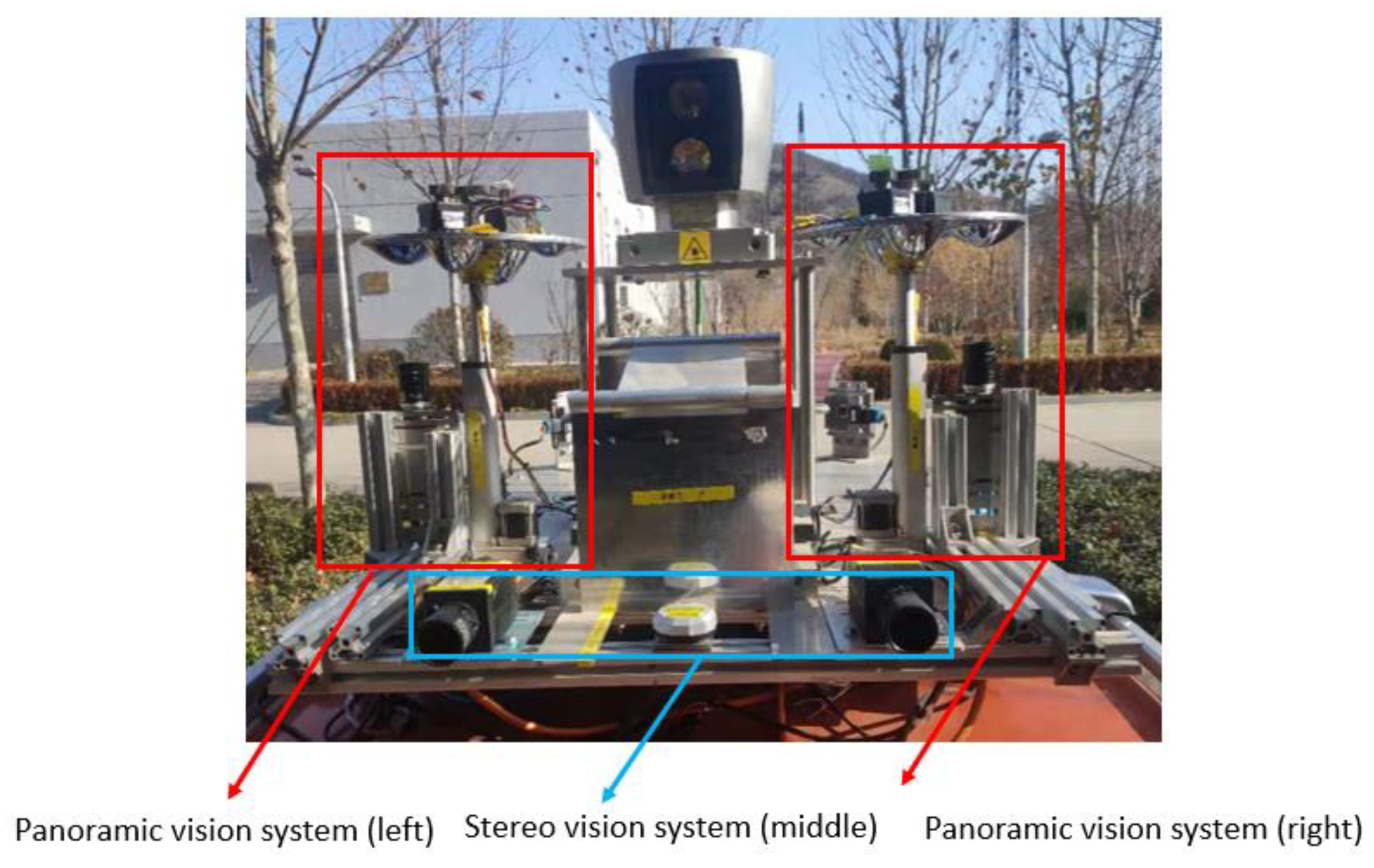

3.1. Panoramic Systems Design

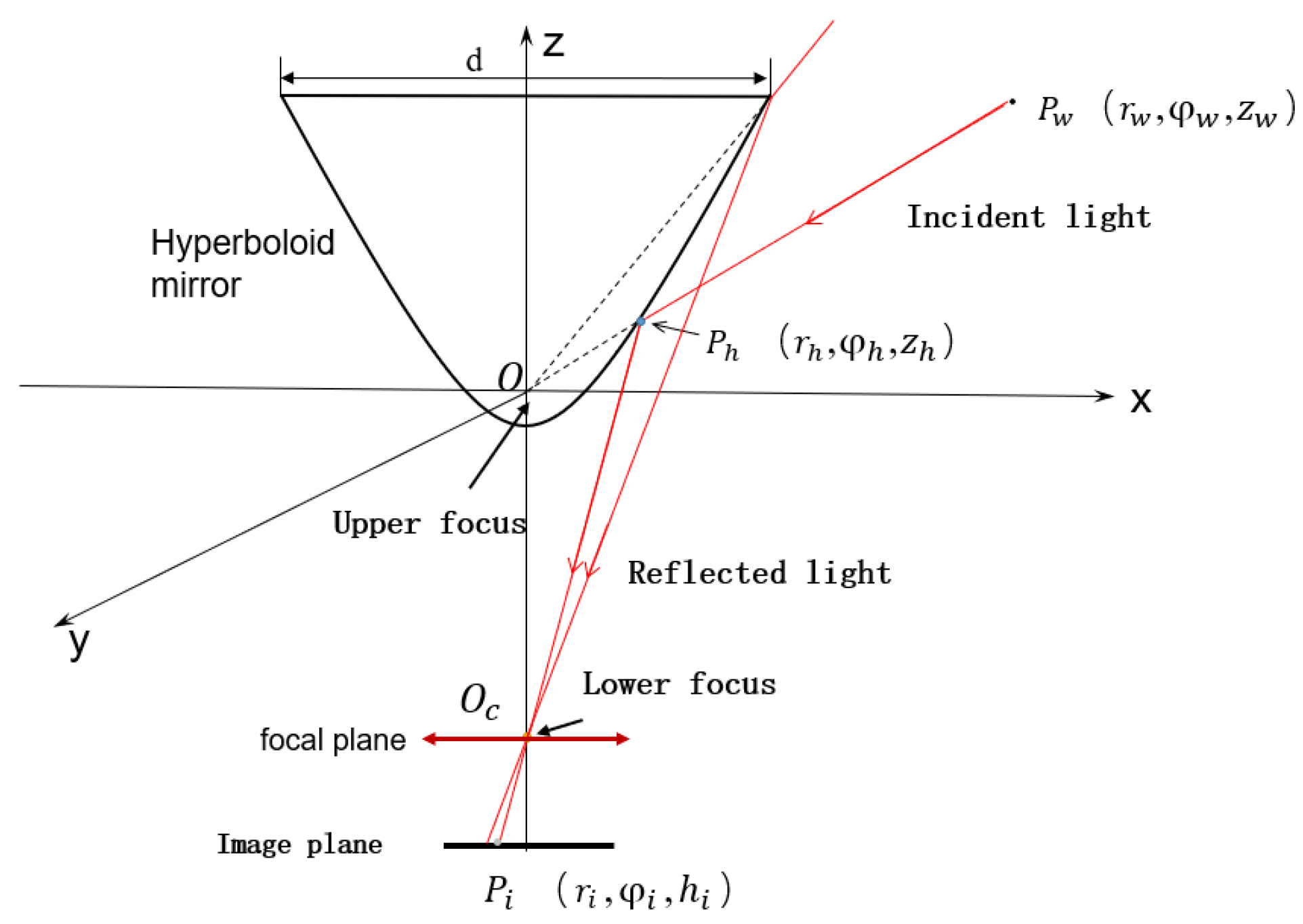

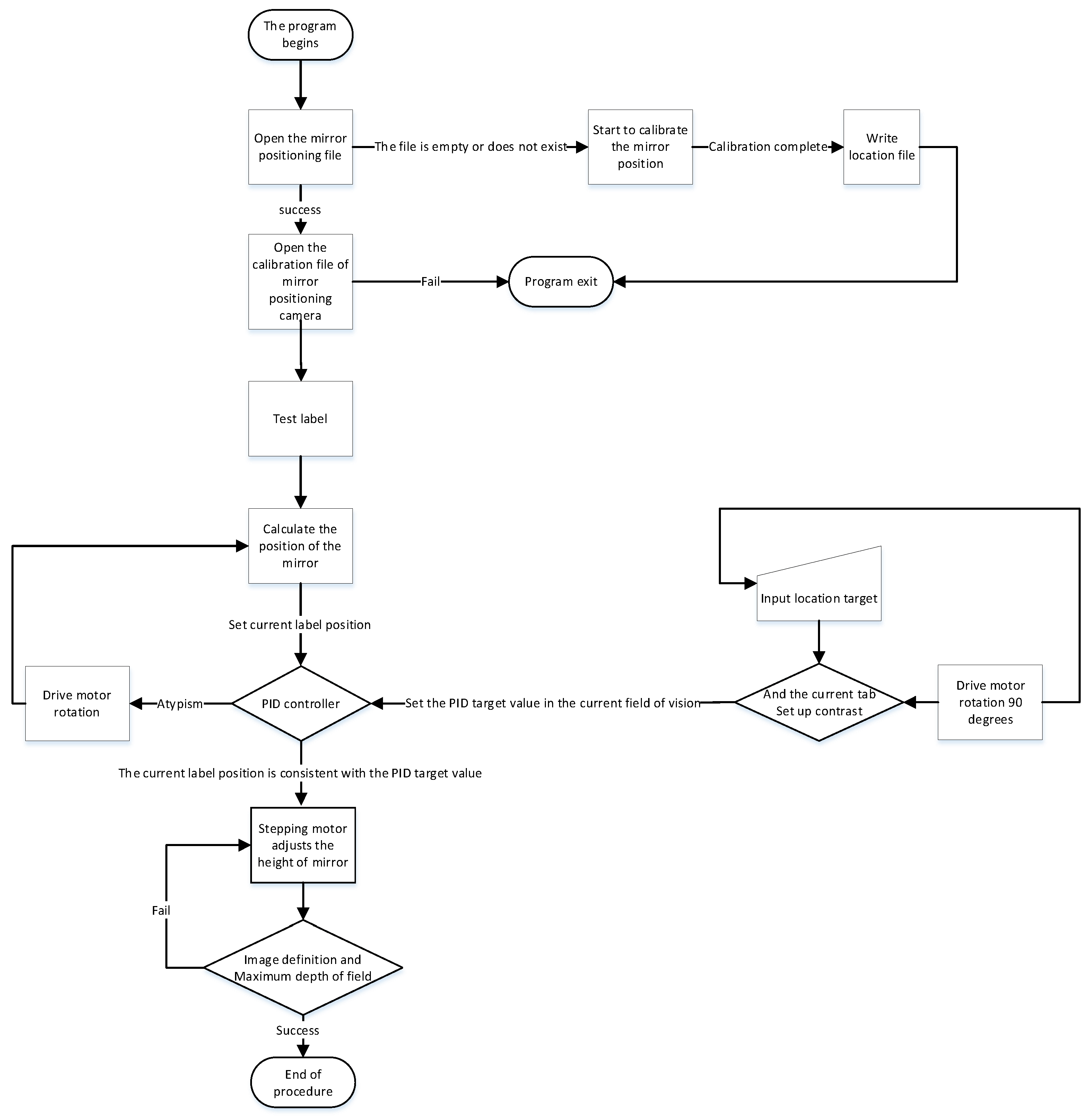

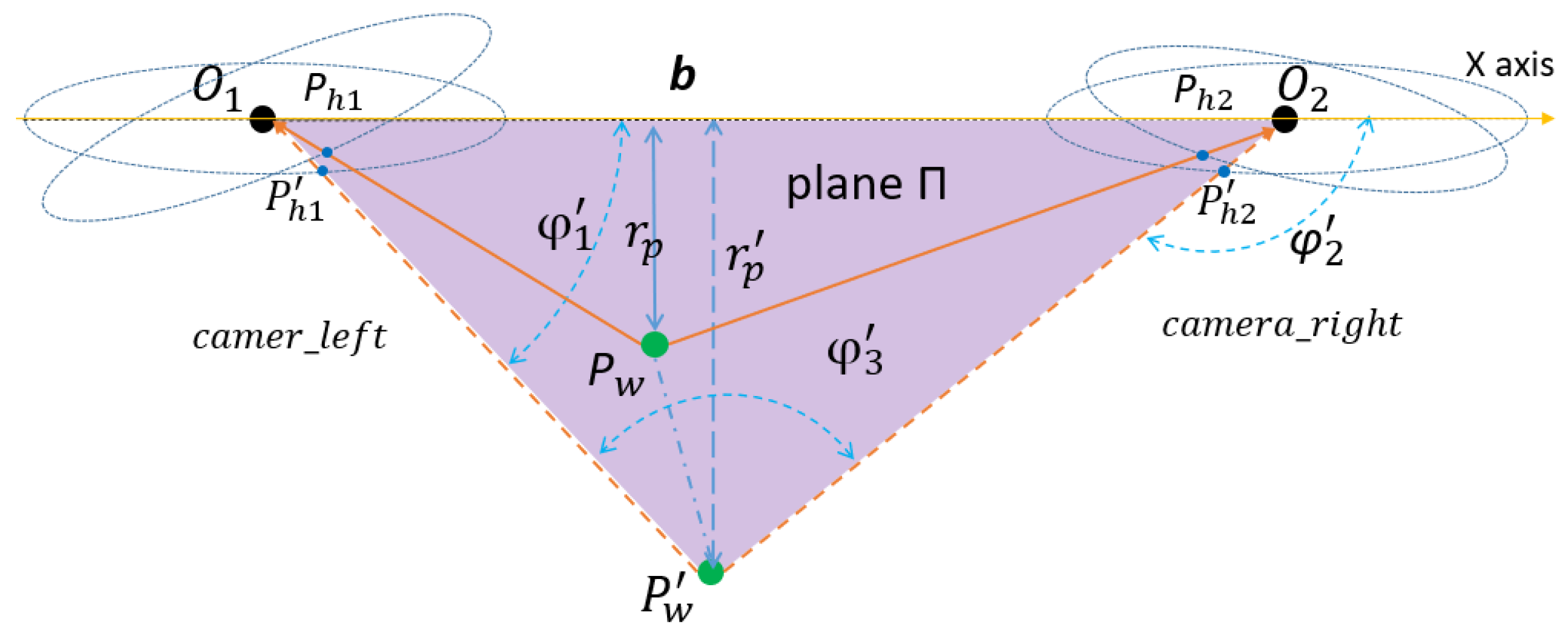

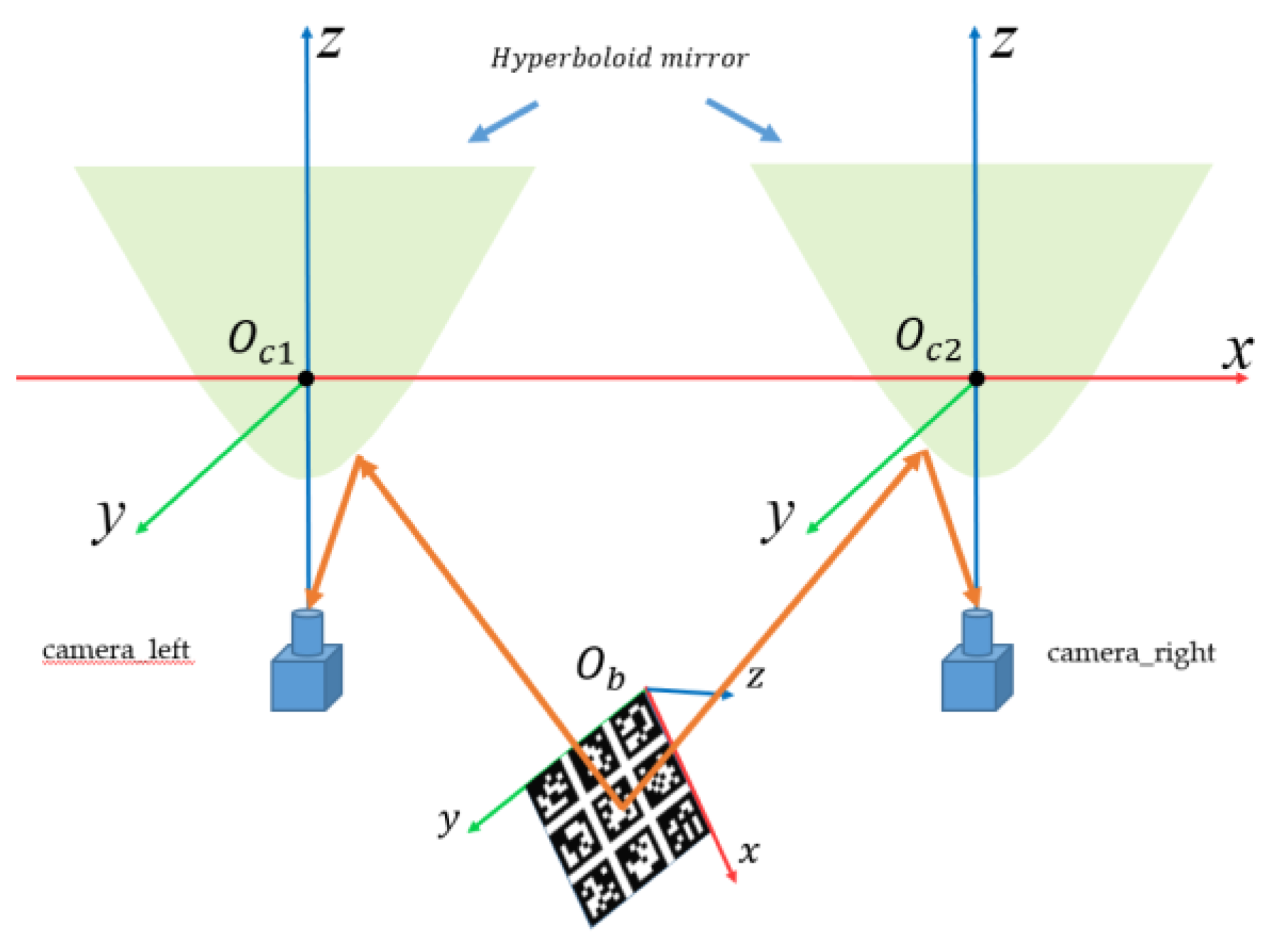

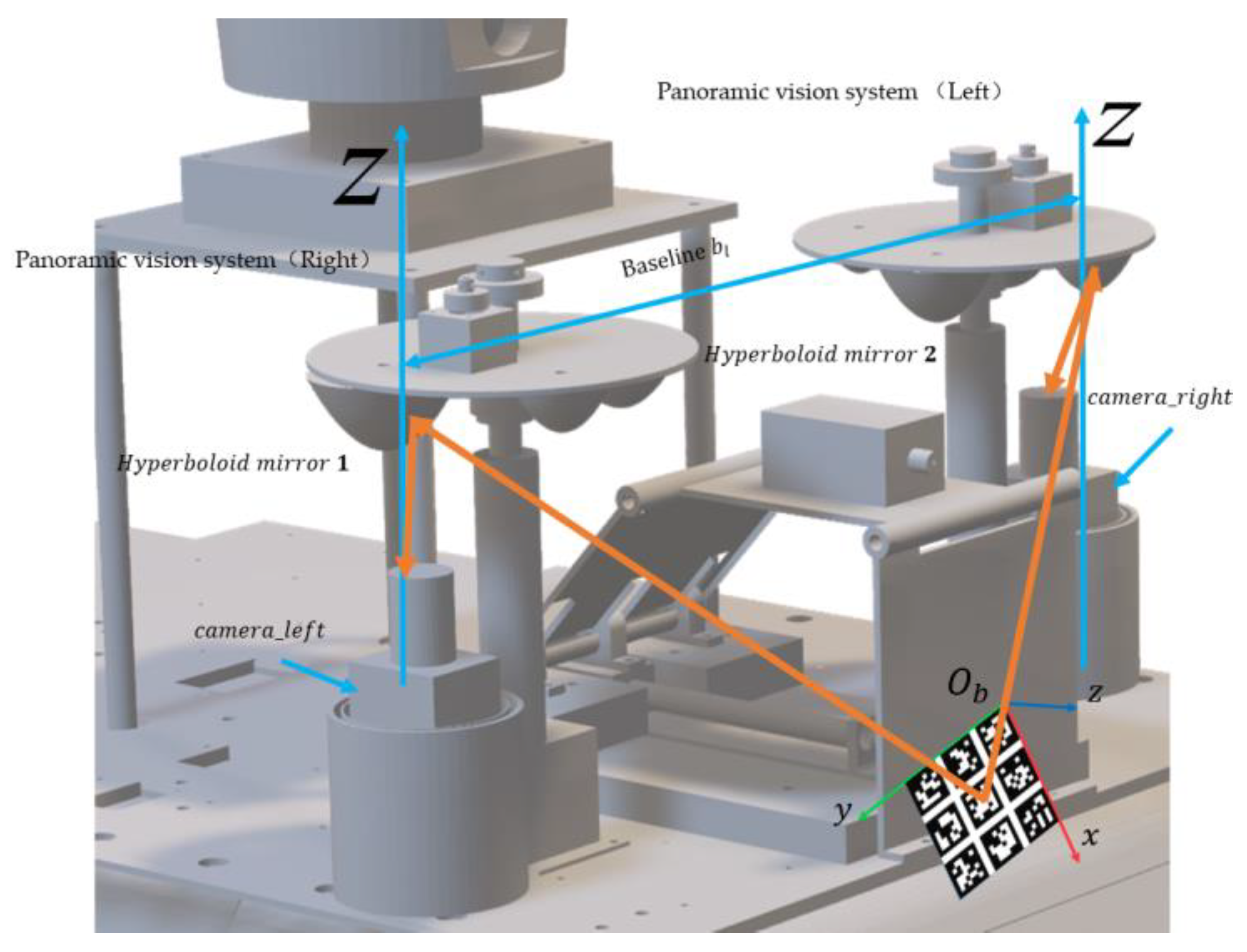

Structure Design and Depth Information Acquisition Theory of HOVS

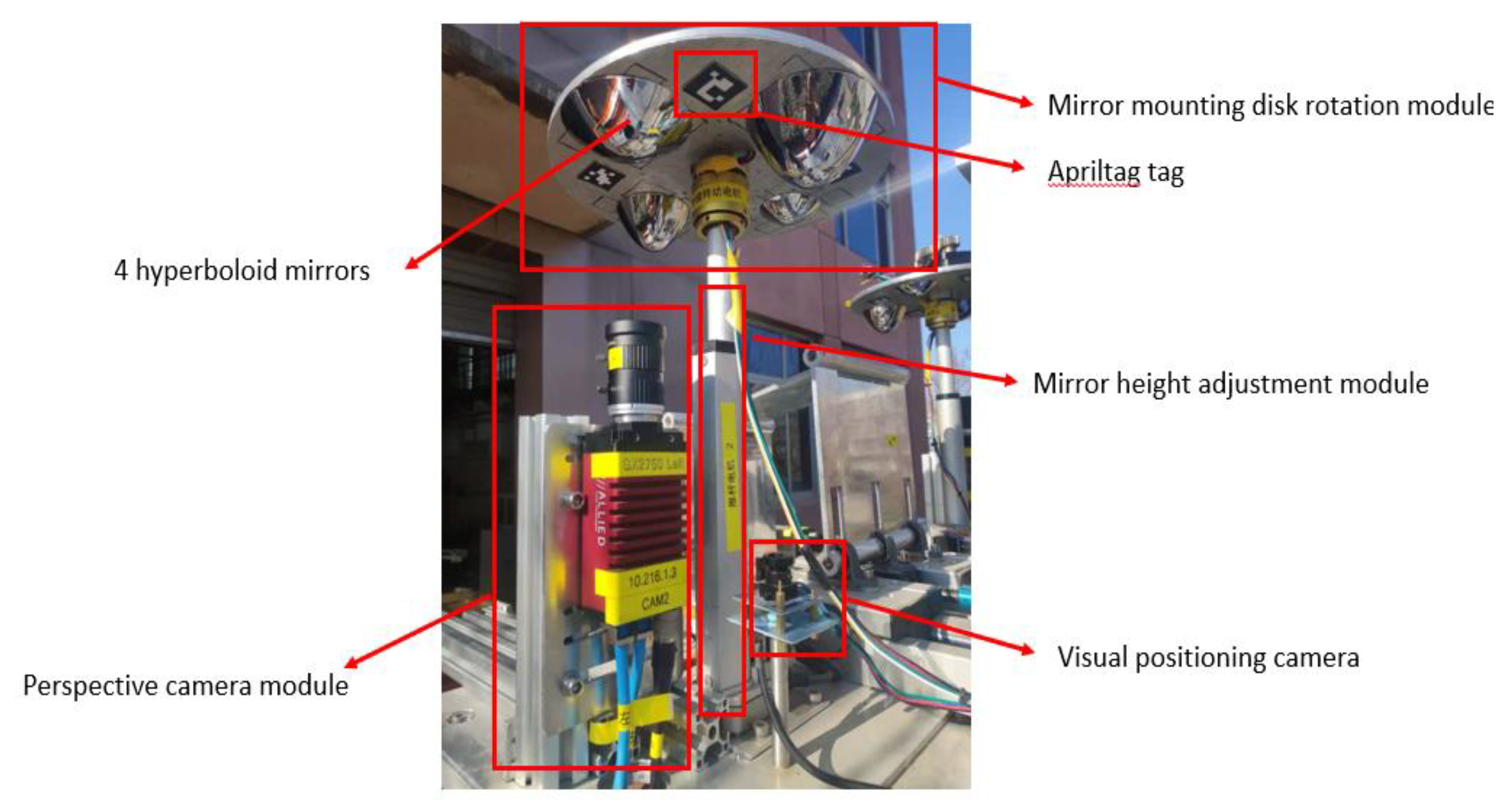

- Hyperboloid mirror module and perspective camera module

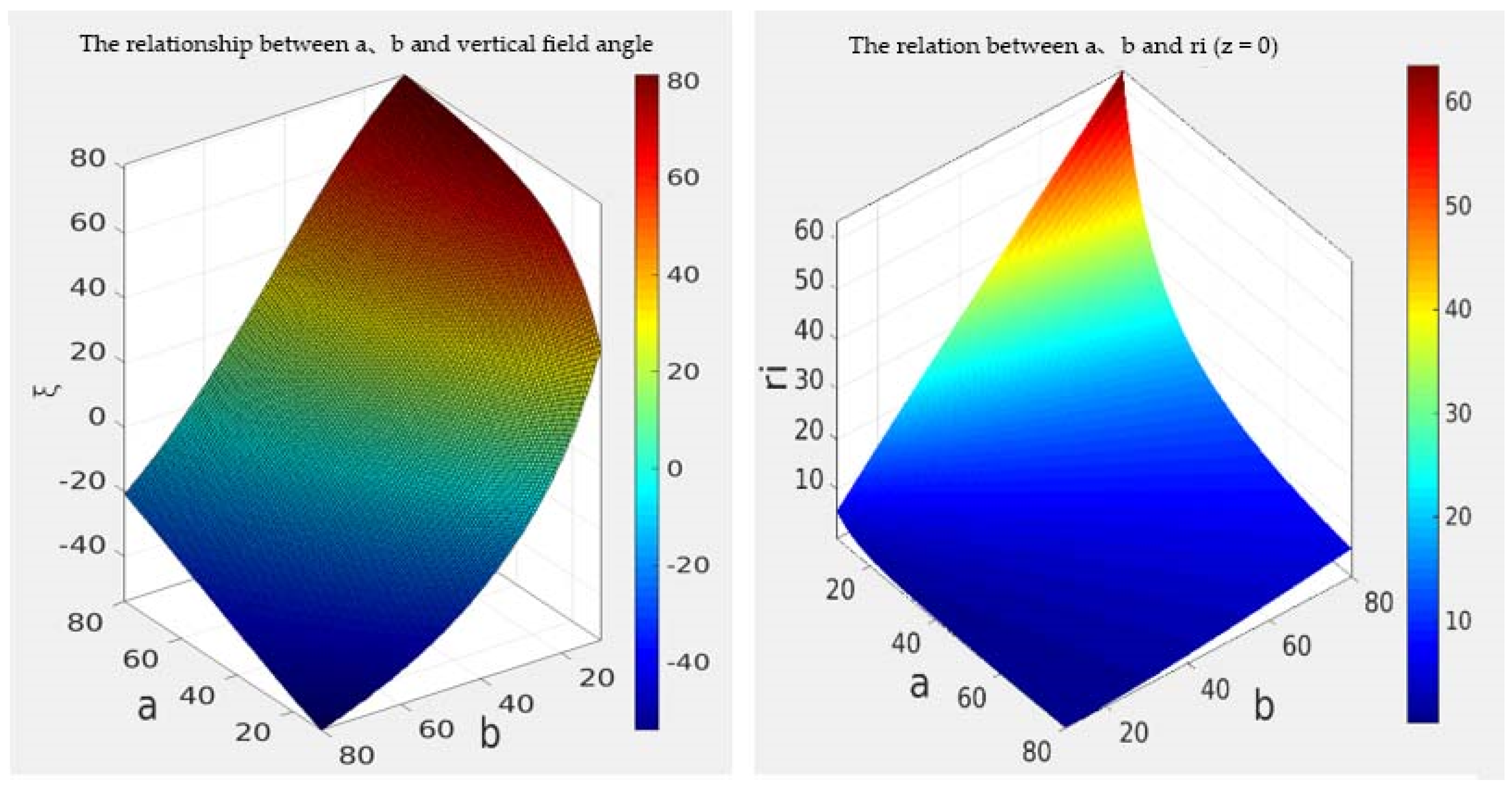

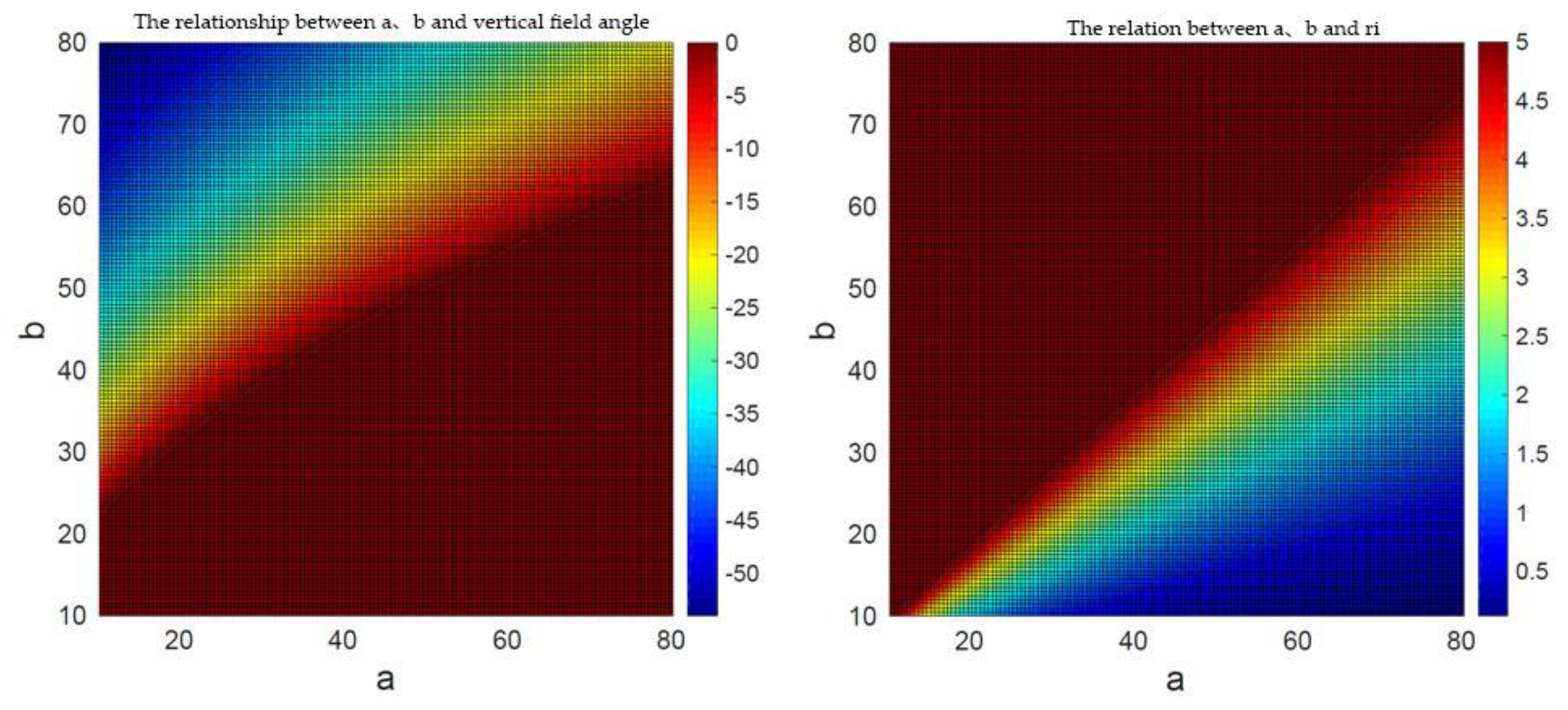

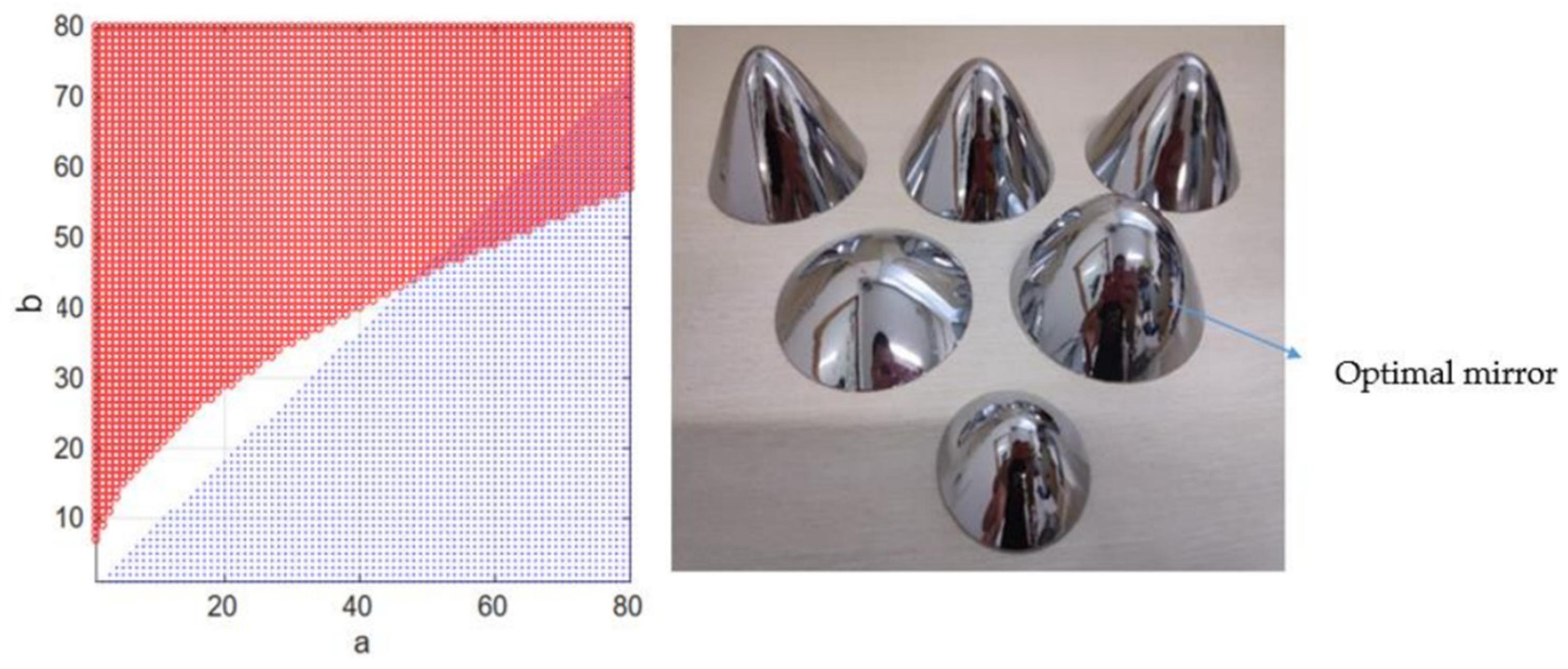

- The upper boundary point of vertical field of viewMax Pmax and lower boundary point Pmin. The projection points of Min should be in the image plane.

- Since the angle of view above the horizontal plane of the hyperbolic reflector is basically reflected sky and belongs to the invalid area, the upper boundary angle of the vertical field of view angle is less than 0°.

- The viewpoint of the perspective camera should include the maximum reflection area of the hyperbolic mirror. Because the field of view angle of the perspective camera is inversely proportional to the focal length, it is necessary to select the lens with small focal length when selecting the focal length of the perspective camera. In the experiment, the focal length of the smallest one-inch lens is 16 mm, which is cheap and common.

- 2.

- Mirror mounting disk rotation module, mirror height adjustment module, and visual positioning module.

- 3.

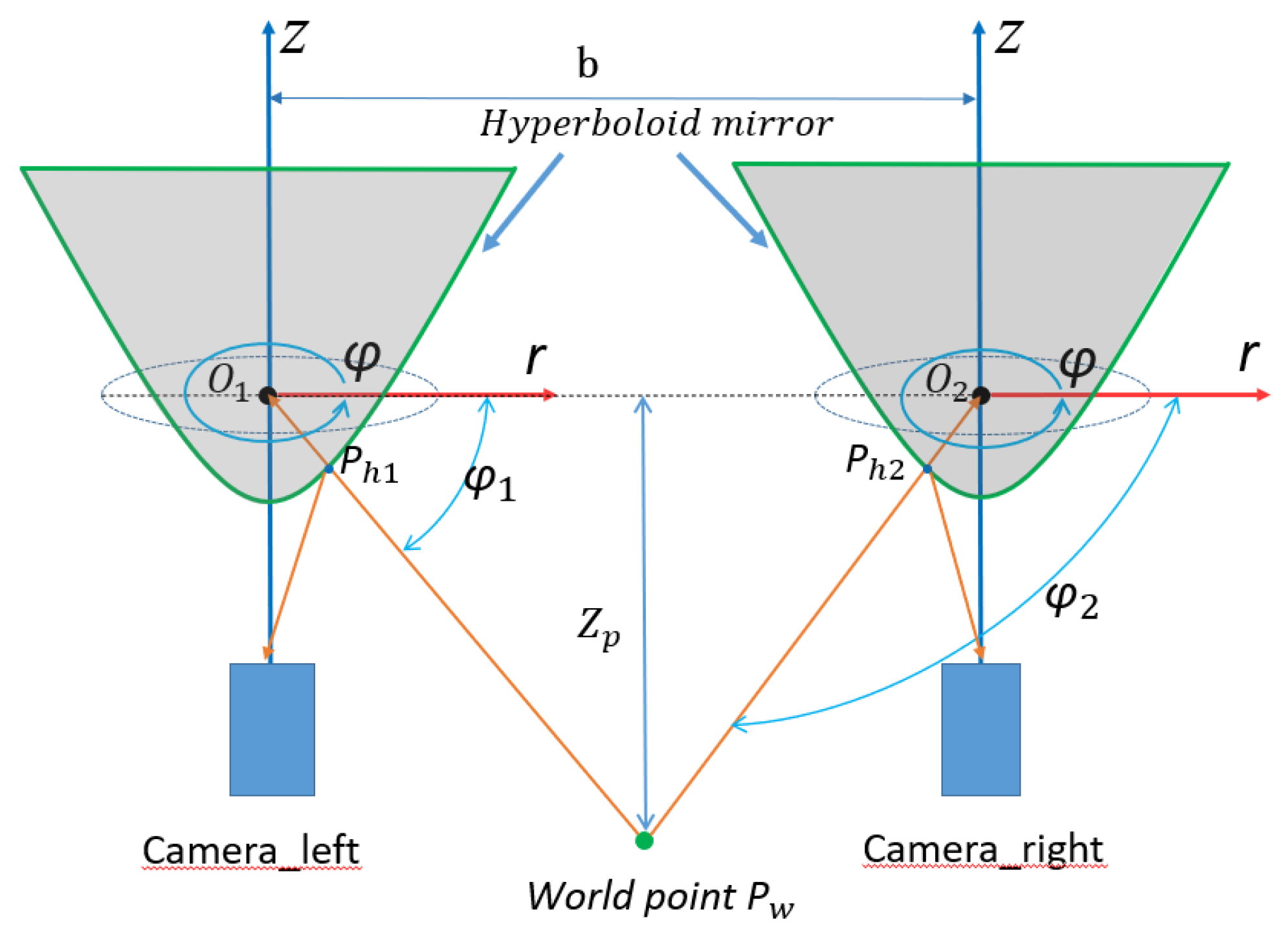

- Principle of depth information acquisition in HOVS.

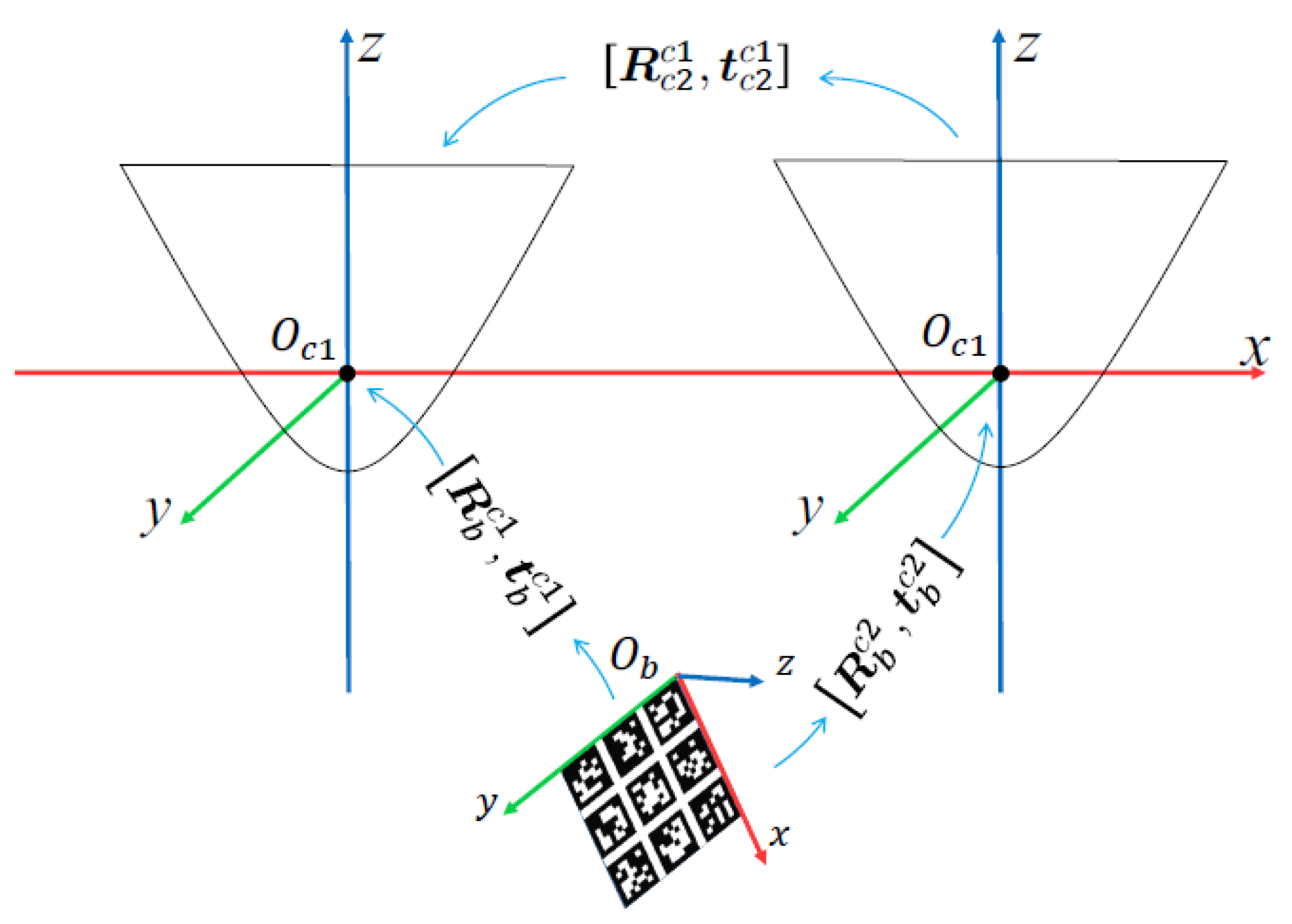

3.2. HOVS Calibration

3.2.1. Calibration Principle of Monocular Panoramic Vision Systems for Single-View Hyperboloid Mirror

3.2.2. Calibration Principle of Binocular Stereo Panoramic Vision Systems with Single-View Hyperboloid Mirror

| Algorithm 1 Aruco estimates tag attitude. |

| Input: n pairs of left and right panoramic images |

| if i < n then |

| Binocular stereo panoramic image distortion correction |

| Image preprocessing, extracting Aruco tag |

| If Aruco tag is found in both left and right images then |

| Extract the posture of Aruco tag, is added to the nonlinear optimization equations |

| else i = i + 1 |

| end if |

| Else |

| Solving nonlinear optimization equations with MATLAB |

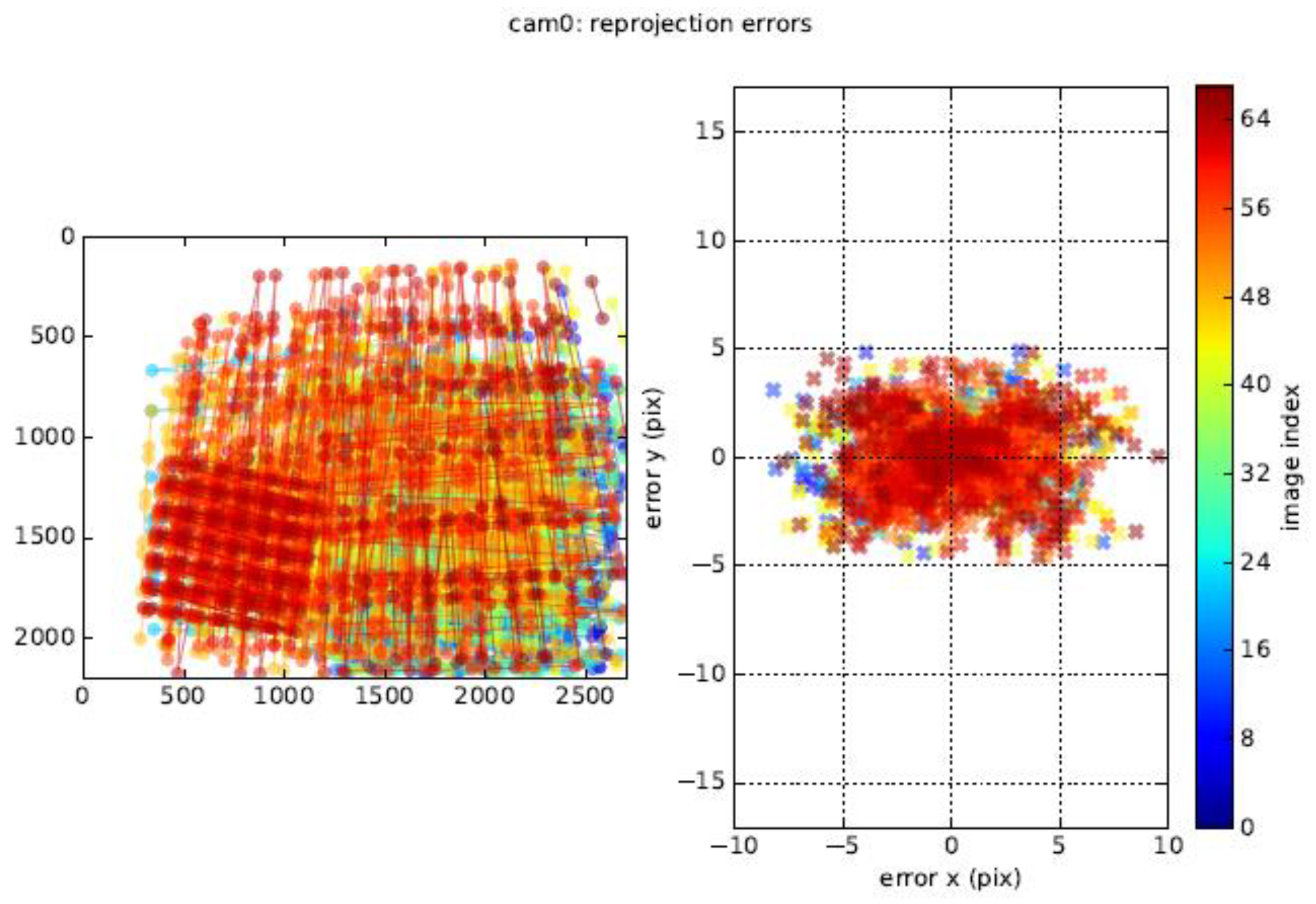

| if the average reprojection error is less than ±5 pixels then |

| Calibration successful |

| Else |

| Calibration failed |

| end if |

| end if |

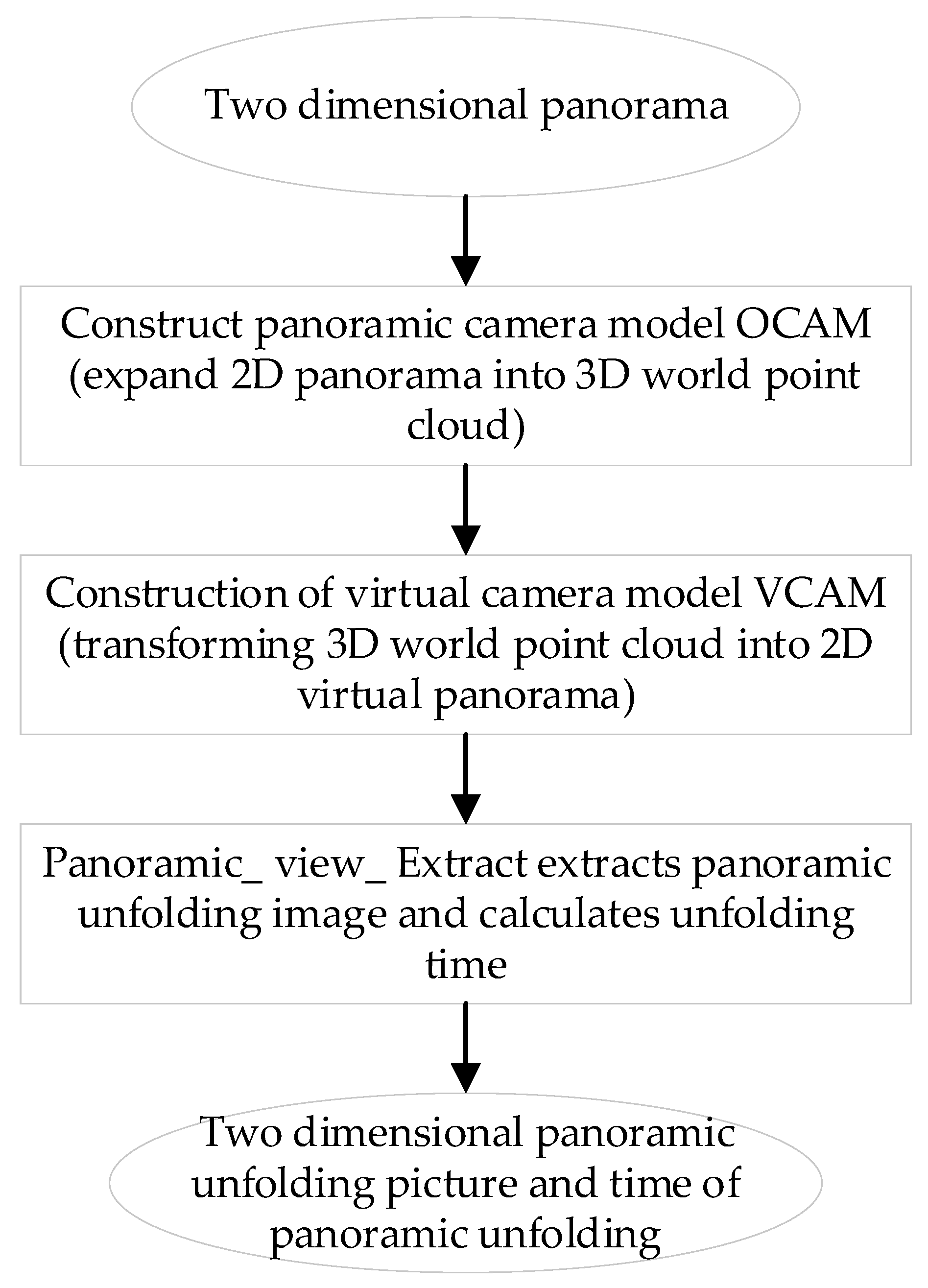

3.3. HOVS Image Expansion

Panoramic Image Expansion Algorithm Based on VCAM

| Algorithm 2 Transform 2D panoramic image to 3D world point cloud. |

| Input: 2D panoramic image |

| Output: 3D world point cloud 1: Start of OCAM algorithm 2: Loading OCAM model 3: Initialize OCAM 4: Read initial 2D panoramic image 5: Using polyval () to calculate Z coordinate of 3D world point 6: Using cam2word () to transform 2D image points into 3D world point clouds 7: Save world point cloud image |

| 8: End of OCAM algorithm |

| Algorithm 3 Image transformation from 3D world point cloud to panoramic expansion. |

| Input: 3D world point cloud |

| Output: Panoramic expansion image 1: VCAM algorithm starts 2: Loading VCAM model 3: Setting VCAM parameters 4: Loading 3D point cloud image 5: Update VCAM camera parameters 6: Using MD5 algorithm to verify the integrity of image expansion data transmission 7: Read image mapping file 8: Transformation from 3D point cloud image to 2D image points 9: Calculation of expanded image by bilinear interpolation algorithm 10: Real-time display of expansion image progress with progress bar 11: Mean optimization re_ MAP1 and re_ MAP2 image 12: Save the optimized image |

| 13: End of VCAM algorithm |

| Algorithm 4 Panoramic_view_extract. |

| Input: Panoramic theme, OCAM and VCAM Output: Panoramic expansion time and panoramic expansion map 1: panoramic_ view_ Start of extract algorithm 2: Initialize panoramic_ view_ extract 3: Circularly publish image_ topic, image_ pub_ topic, camera_ model, virtual_ camera, point cloud_ topic, remap_ save_ path 4: Subscribe to image_ Topic, publishing to point_ Cloud and point_ Topic of cloud2 5: Initialize OCAM and VCAM, load mapping file 6: Through the defined display and adjust macro, create image_ Remap and control_ Panel window (parameters and pose of camera can be adjusted) 7: Load OCAM model into CV: mat map, and then map CV: mat map to VCAM: point_ Map calculates its time t_ i. Finally, VCAM: point_ The map is expanded quickly and the time t is calculated_ p 8: Finally, save the expanded map to remap_ save_ File |

| 9: panoramic_ view_ End of extract algorithm |

4. Experiments and Results

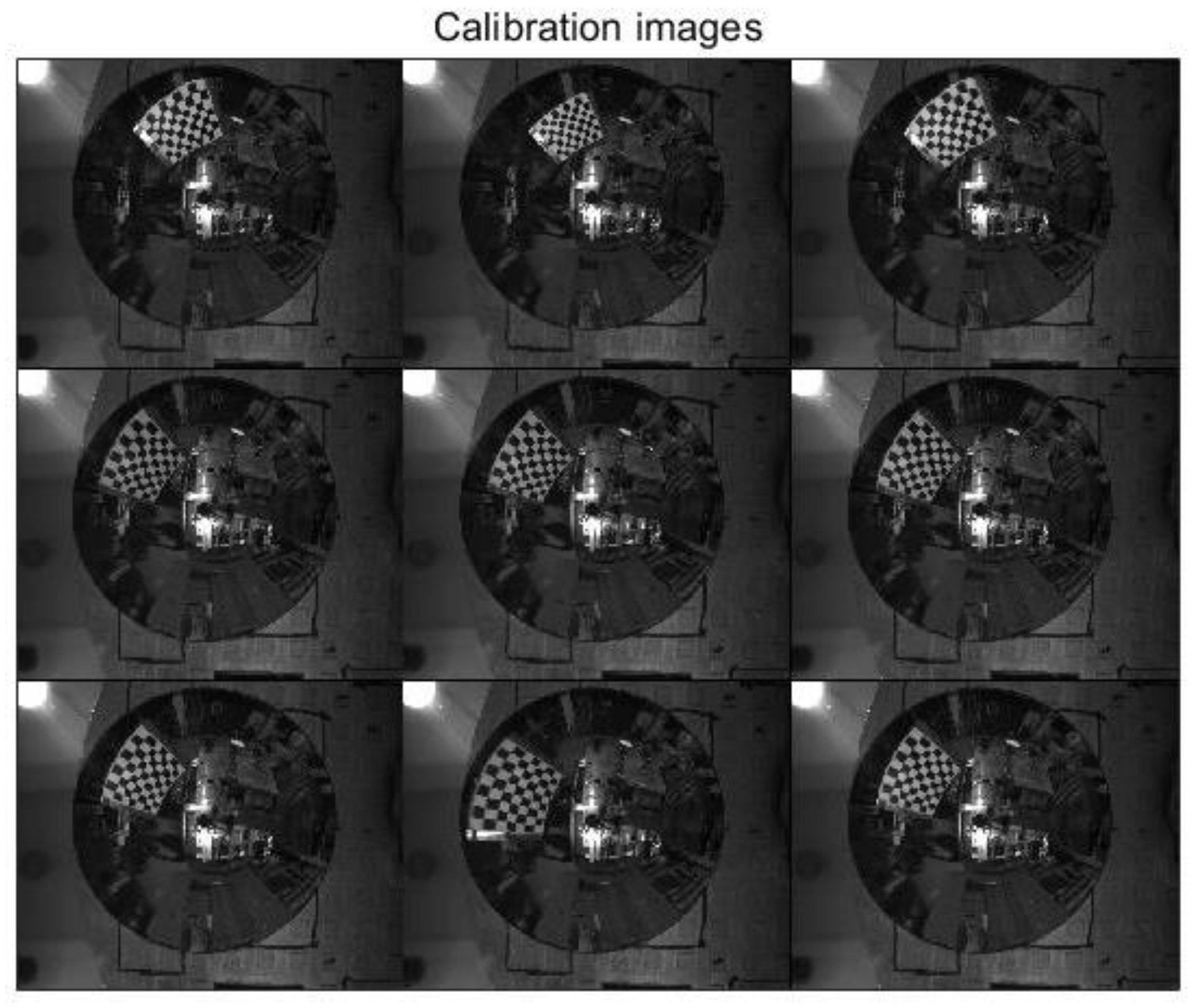

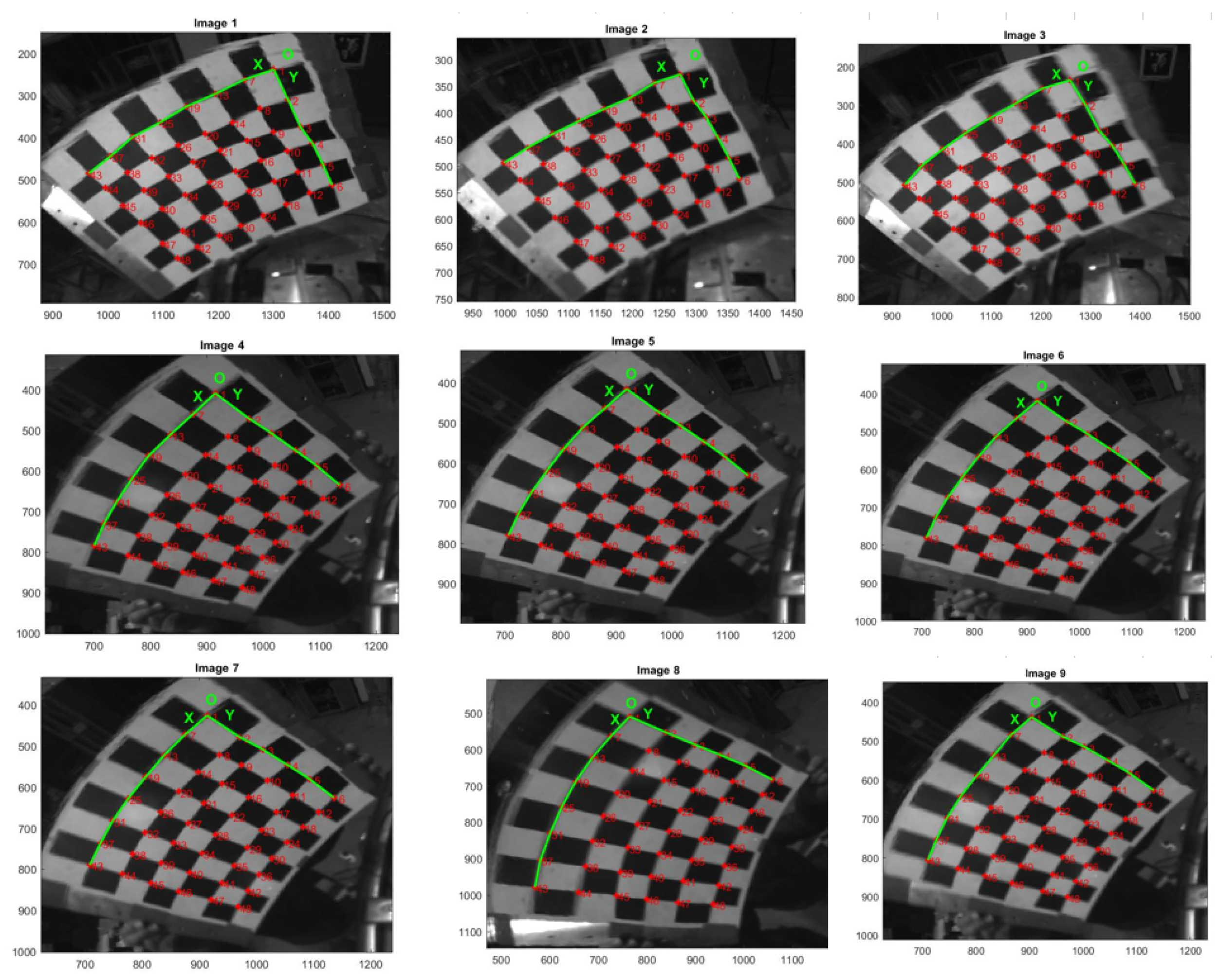

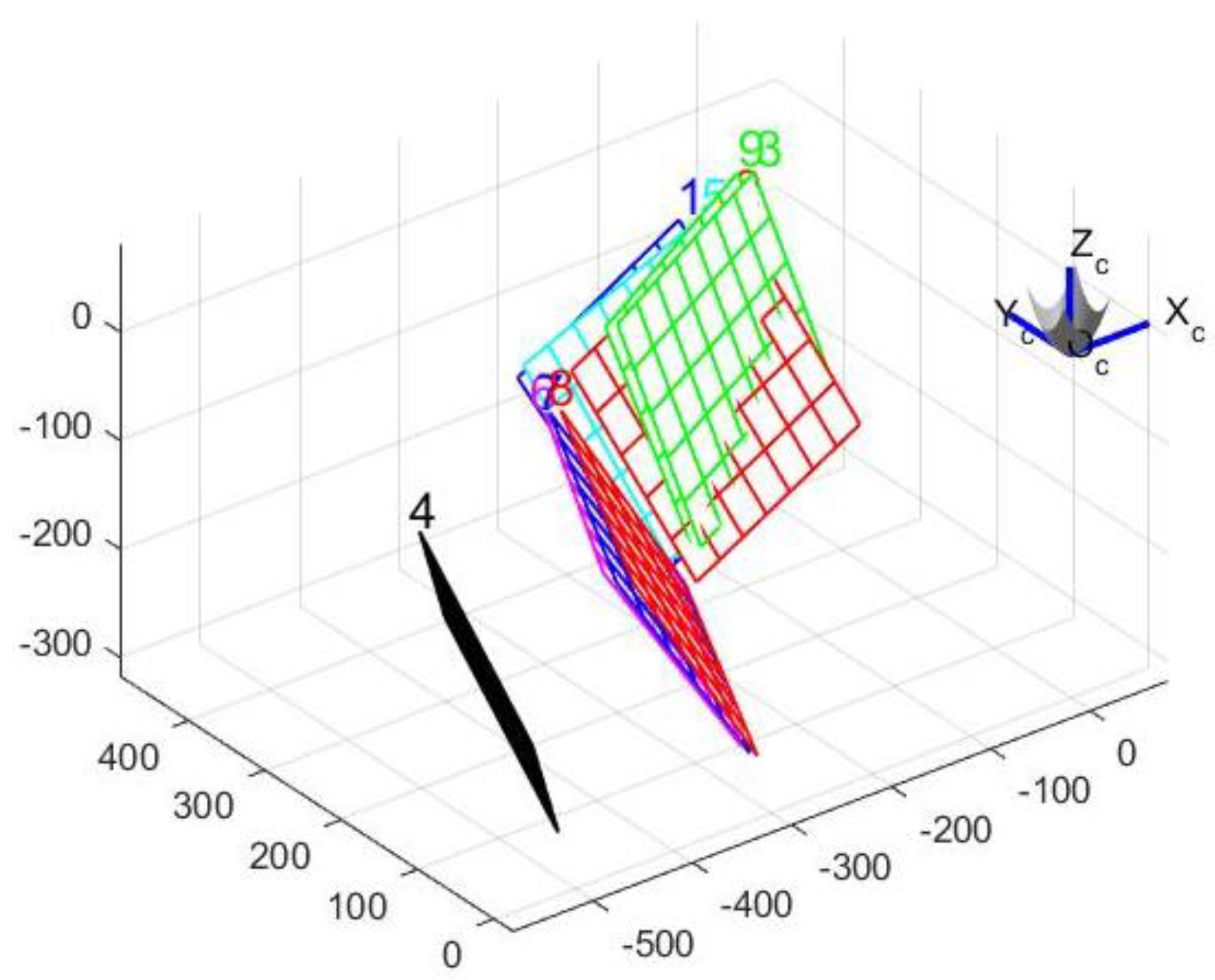

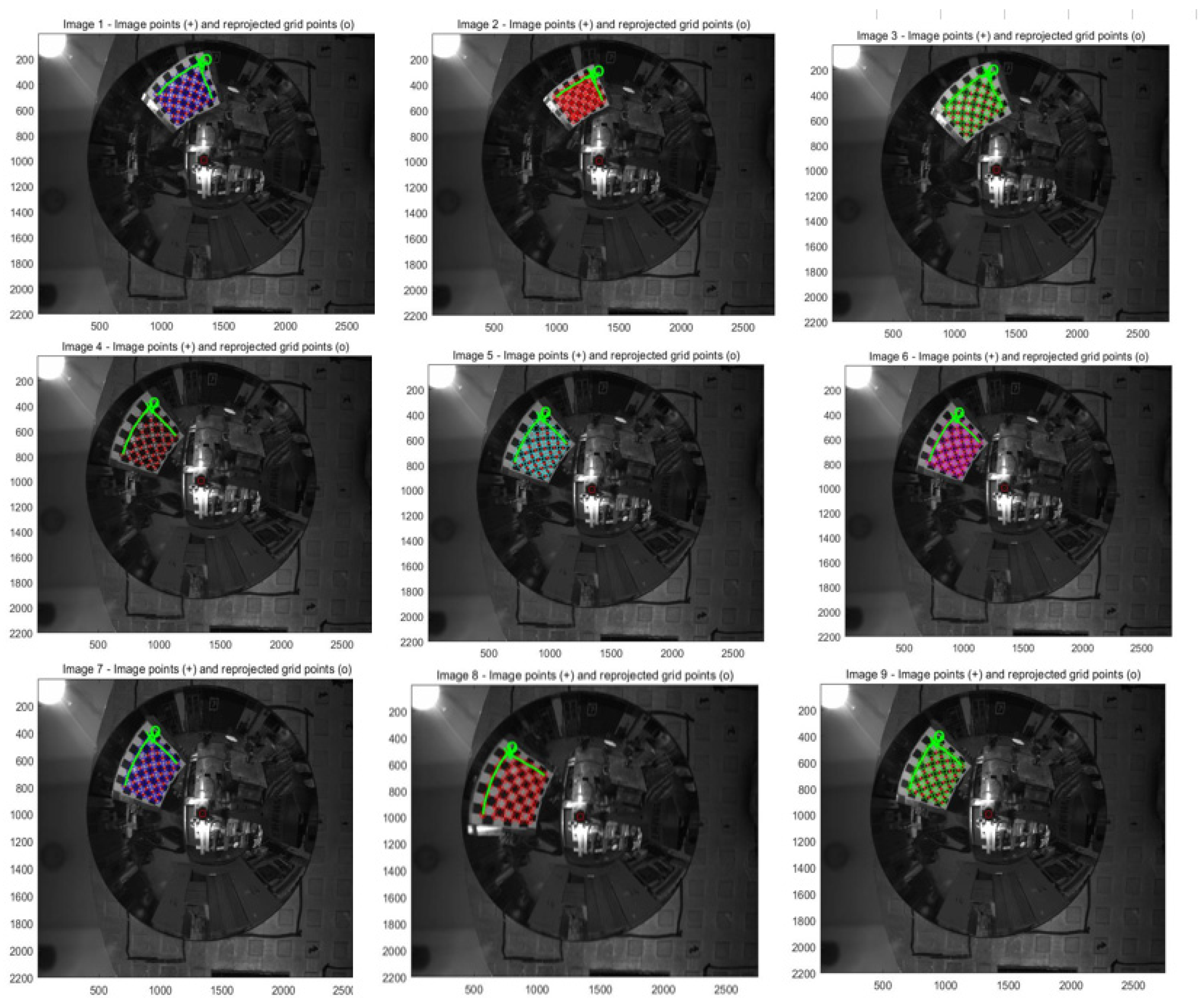

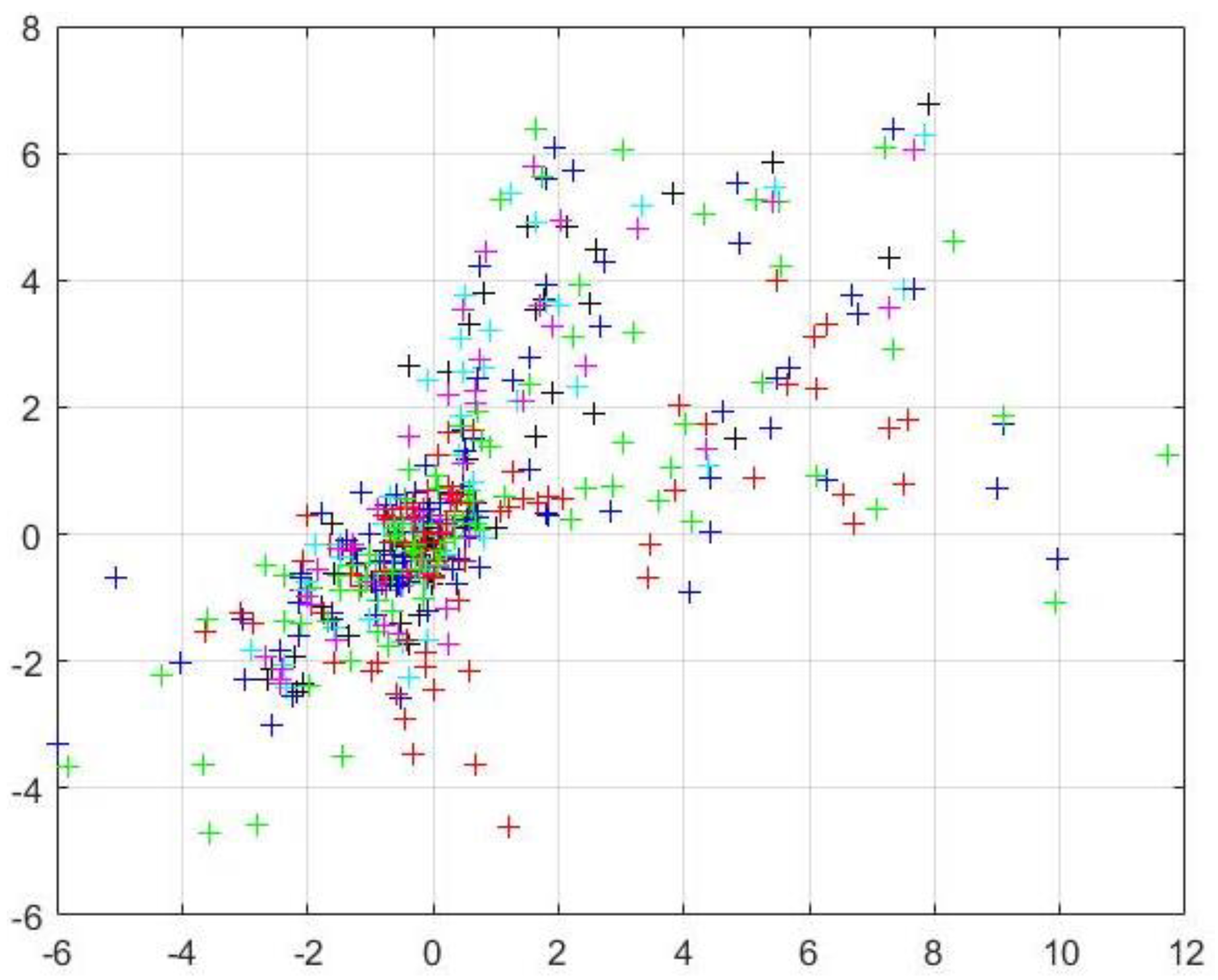

4.1. Calibration Experiment and Experimental Results of Monocular Panoramic Vision Systems with Single-View Hyperboloid Mirror

4.1.1. Calibration Experiment

- Average reprojection error computed for each chessboard (pixels):

- The results of nonlinear optimization are as follows:

- The results of robust nonlinear optimization are as follows

4.1.2. Calibration Result

4.2. Calibration Experiment and Experimental Results of Binocular Stereo Panoramic Vision Systems with Single-View Hyperboloid Mirror

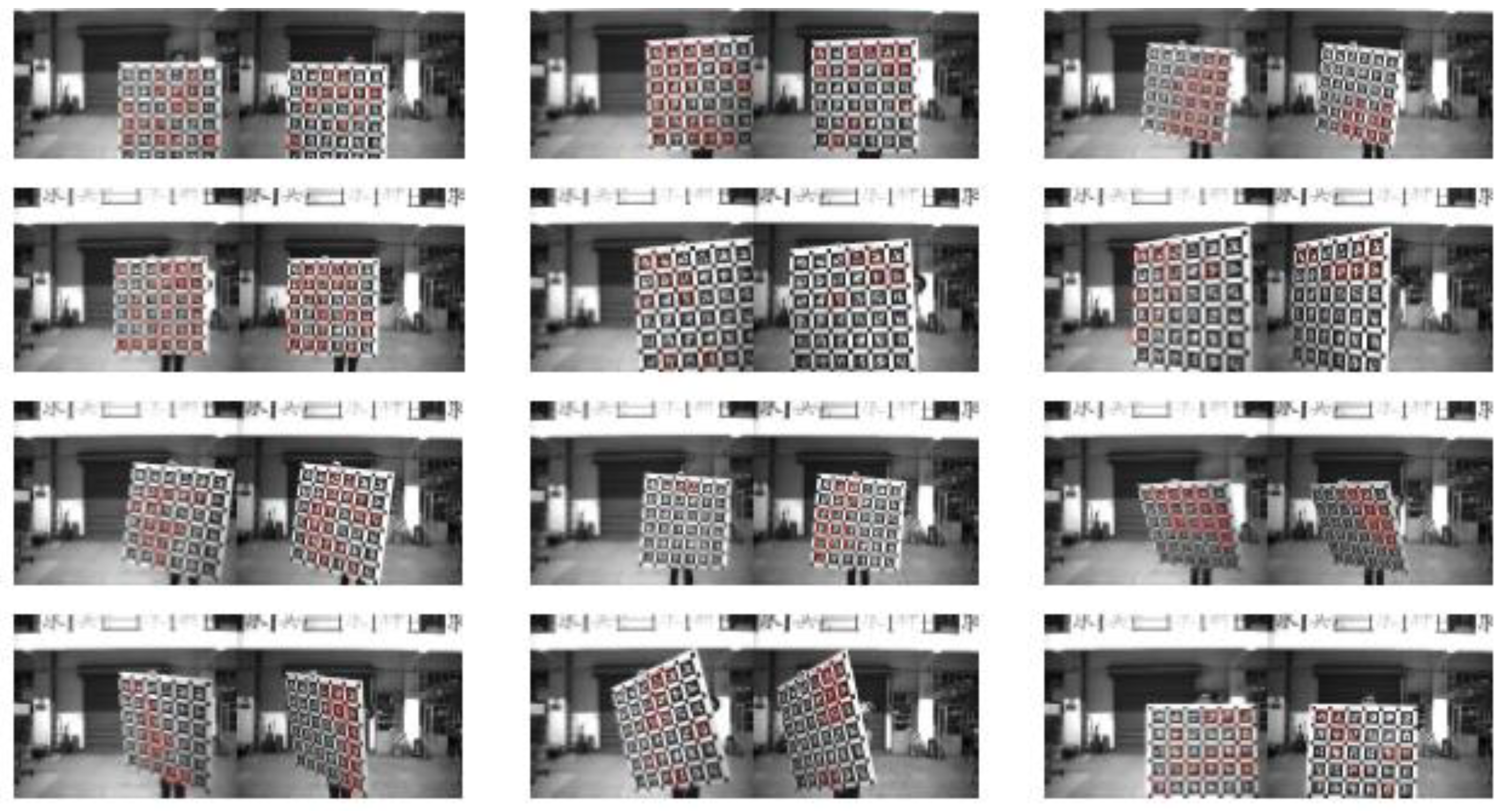

4.2.1. Calibration Experiment

- 4.

- One Aruco calibration board, as shown in Figure 23.

- Collect the images of two panoramic vision systems at the same time, and keep the images containing the Aruco calibration board as far as possible. A total of 12 pairs of images are collected.

- According to the calibration results of the panoramic vision systems and the back-projection transformation, the collected image is partially expanded and the distortion is corrected. Figure 24 shows the partially expanded image of the panoramic vision systems after the back-projection transformation.

- 3.

- 4.

- According to the position and pose of the Aruco calibration board in each image, the coordinates P of each corner on the calibration board in the current camera coordinate systems are calculated and .

- 5.

- According to Equation (23), the nonlinear optimization problem is constructed and solved by MATLAB.

- 6.

- Calculate the reprojection error, and the calibration is considered successful when the average is within 10 pixels.

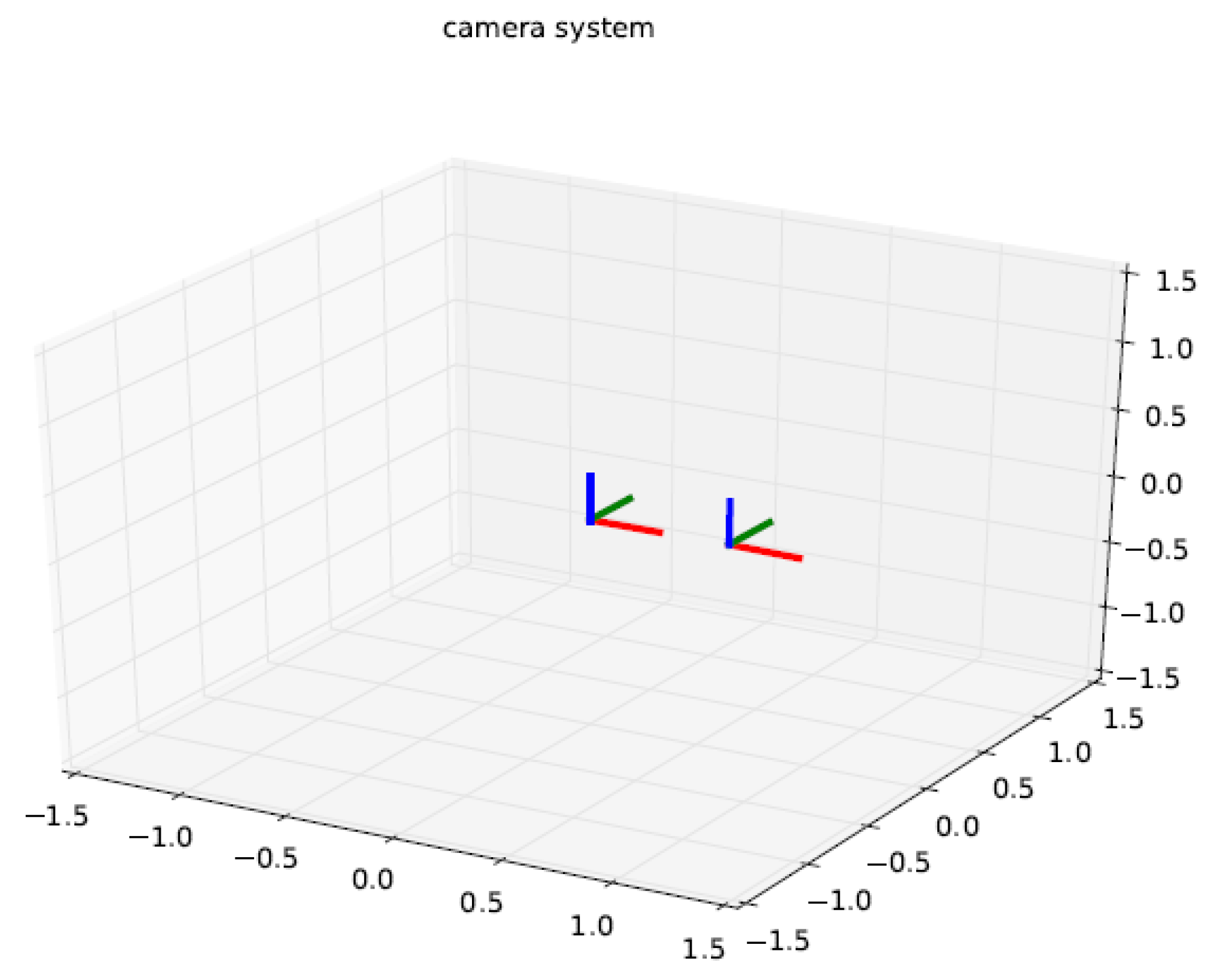

- Equation (23) is the rotation matrix and translation vector between two panoramic vision systems.

- The baseline length between the two panoramic vision systems is 0.64 m, the deviation in Y direction is −0.007 m, and the deviation in Z direction is −0.014 m.

4.2.2. Calibration Result

4.3. Experiments and Results of Image Expansion in HOVS

- Experimental setting: Xishan campus of Beijing University of technology.

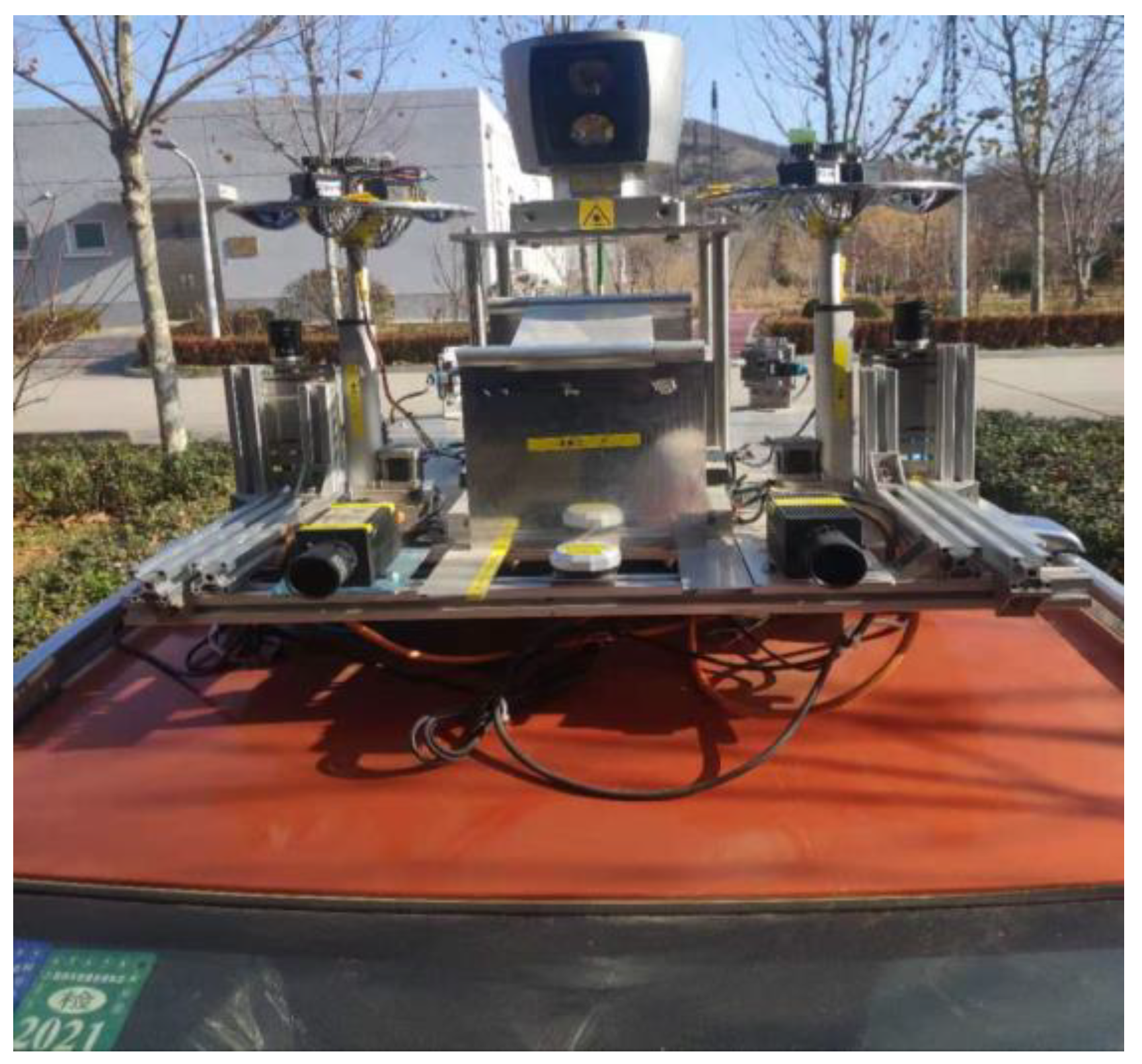

- Experimental equipment: Unmanned vehicle (Modified by BAIC EC180) and perception platform, HOVS systems (GX2750 camera resolution 2700 × 2200), computer, and other necessary equipment. Unmanned systems experimental platform as shown in Figure 29.

- Experimental evaluation index: The new HOVS systems can expand the panoramic image in real time with less distortion. As shown in Figure 30 below.

- Experimental method: By driving the vehicle in Xishan campus, the collected panoramic image is expanded in real time with small distortion.

- Panorama resolution: At 2700 × 2200 for single panoramic vision systems.

- Resolution of unfolded image: Three directions of single panoramic vision systems, each direction 1200 × 700 (secondary interpolation), a total of six directions of unfolded image.

- Algorithm efficiency: Using the 2.3 Ghz main frequency processor, multithreading parallel processing, six direction pictures are expanded at the same time, each frame averages 4 to 5 ms (panoramic video frame rate is 10 fps), which can achieve the effect of real-time panoramic expansion.

- Algorithm effect: Using the mathematical model of panoramic calibration to interpolate the missing pixels, the image distortion after interpolation is significantly reduced (does not affect the typical feature extraction). Effect of partial expansion is as shown in Figure 31.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- AMiner. Automatic Driving Research Report of Artificial Intelligence. Available online: https://static.aminer.cn/misc/article/selfdriving.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2018).

- Rees, D.W. Panoramic Television Viewing Systems. U.S. Patent 350546, 7 April 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Yagi, Y.; Kawato, S.; Tsuji, S. Real—Time omnidirectional image sensor (COPIS) for vision—Guided navigate. IEEE Trans. Robot. 1994, 1, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J. Image Based Homing. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Sacramento, CA, USA, 22–25 April 1991; pp. 620–625. [Google Scholar]

- Yamazawa, K.; Yagi, Y.; Yachida, M. Obstacle detection with omnidirectional image sensor Hyper Omni Vision. In Proceedings of the 1995 IEEE International Conference on Robotics & Automation, Aichi, Japan, 21–27 May 1995; pp. 1062–1067. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F. Research on Panoramic Vision Image Quality Optimization Method. Ph.D. Thesis, Harbin Engineering University, Harbin, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hang, Y.; Huang, F. Panoramic Visual SLAM Technology for Spherical Images. Sensors 2021, 21, 705. [Google Scholar]

- Negahdaripour, S.; Zhang, H.; Firoozfam, P.; Oles, J. Utilizing Panoramic Views for Visually Guided Tasks in Underwater Robotics Applications. In Proceedings of the 2001 MTS/IEEE Conference and Exhibition (OCEANS 2001), Honolulu, HI, USA, 5–8 November 2001; pp. 2593–2600. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Xu, Q.; Luo, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S. A Robust Method for Automatic Panoramic UAV Image Mosaic. Sensors 2019, 19, 1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.H.; Li, K.J.; Tao, X.; Shi, Z.; Zhang, D.; Shao, H.; Liang, Z. Development and Application of Panoramic Vision Systems. Comput. Meas. Control. 2018, 22, 1664–1666. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, J.; Su, Y. Panoramic imaging systems of refraction reflection. Laser J. 2004, 25, 62–64. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z. Flexible camera calibration by viewing a plane from unknown orientations. In Proceedings of the Seventh IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Kerkyra, Greece, 20–27 September 1999; pp. 666–673. [Google Scholar]

- Grossberg, M.D.; Nayar, S.K. A general imaging model and a method for finding its parameters. In Proceedings of the Eighth IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 7–14 July 2001; pp. 108–115. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, R. A versatile camera calibration technique for high-accuracy 3D machine vision metrology using off-the-shelf TV cameras and lenses. IEEE J. Robot. Auto. 1987, 4, 323–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. In A Flexible New Technique for Camera Calibration. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2001, 22, 1330–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M. Research on Camera Calibration Technology. Master’s Thesis, Nanchang Aeronautical University, Nanchang, China, June 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, J. Camera self-calibration method based on Kruppa equation. J. Dalian Univ. Technol. 2003, 43, 82–85. [Google Scholar]

- Geyer, C.; Daniilidis, K. A Unifying Theory for Central Panoramic Systems and Practical Implications. In Proceedings of the 2000 European Conference on Computer Vision, Dublin, Ireland, 26 June–1 July 2000; pp. 445–461. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, S.B. Catadioptric self-calibration. In Proceedings of the 2000 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Hilton Head, SC, USA, 13–15 June 2000; pp. 201–207. [Google Scholar]

- Svoboda, T.; Pajdla, T. Epipolar geometry for central cata-dioptric cameras. Int. J. Comput. Vision. 2002, 49, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micušık, B. Two-View Geometry of Omnidirectional Cameras. Ph.D. Thesis, Czech Technical University, Prague, Czechia, June 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Barreto, J.P.; Araujo, H. Geometry properties of central cata-dioptric line images and application in calibration. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2005, 27, 1327–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puig, L.; Bastanlar, Y.; Sturm, P.; Guerrero, J.J.; Barreto, J. Calibration of Central Catadioptric Cameras Using a DLT-Like Approach. Int. J. Comput. Vision. 2011, 93, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, P. Multi-view geometry for general camera models. In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR’05), San Diego, CA, USA, 20–26 June 2005; pp. 206–212. [Google Scholar]

- Morel, O.; Fofi, D. Calibration of catadioptric sensors by polarization imaging. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Roma, Italy, 10–14 April 2007; pp. 3939–3944. [Google Scholar]

- Kannala, J.; Brandt, S.S. A generic camera model and calibration method for conventional, wide-angle, and fish-eye lenses. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2006, 28, 1335–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikipedia. Fisheye Lens. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fisheye_lens (accessed on 26 August 2010).

- Cłapa, J.P.; Blasinski, H.; Grabowski, K.; Sekalski, P. A fisheye distortion correction algorithm optimized for hardware implementations. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Mixed Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems, Lublin, Poland, 24–26 June 2014; pp. 415–419. [Google Scholar]

- Courbon, J.; Mezouar, Y.; Eck, L.; Martinet, P. A generic fisheye camera model for robotic applications, in: Intelligent Robots and Systems. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, San Diego, CA, USA, 29 October–2 November 2007; pp. 1683–1688. [Google Scholar]

- Scaramuzza, D.; Martinelli, A.; Siegwart, R. A Flexible Technique for Accurate Omnidirectional Camera Calibration and Structure from Motion. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE International Conference of Vision Systems (ICVS’06), New York, NY, USA, 5–7 January 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Scaramuzza, D. Omnidirectional Vision: From Calibration to Robot Motion Estimation. Ph.D. Thesis, ETH Zurich, Zürich, Switzerland, 22 February 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rufli, M.; Scaramuzza, D.; Siegwart, R. Automatic Detection of Checkerboards on Blurred and Distorted Images. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS 2008), Nice, France, 22–26 September 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Scaramuzza, D.; Martinelli, A.; Siegwart, R. A Toolbox for Easy Calibrating Omnidirectional Cameras. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS 2006), Beijing, China, 7–15 October 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, D.; Schwalbe, E.; Maas, H.G. Validation of geometric models for fisheye lenses. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2009, 64, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, S.; Leitloff, J.; Hinz, S. Improved wide-angle, fisheye and omnidirectional camera calibration. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2015, 108, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, M.; Patrick, R. Single View Point Omnidirectional Camera Calibration from Planar Grids. In Proceedings of the 2007 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Rome, Italy, 10–14 April 2007; pp. 3945–3950. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, O.; Katz, R.; Tisse, C.-L.; Durrant-Whyte, H. Camera calibration for miniature, low-cost, wide-angle imaging systems. In Proceedings of the British Machine Vision Conference 2007, Warwick, UK, 10–13 September 2007; Volume 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeong, D.; Velasco-Hernandez, G.; Barry, J.; Walsh, J. Sensor and Sensor Fusion Technology in Autonomous Vehicles: A Review. Sensors 2021, 21, 2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Q.; Liu, C.; Cai, C. A Novel Robot Visual Homing Method Based on SIFT Features. Sensors 2015, 15, 26063–26084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Aziz, Y.I.; Karara, H.M. Direct linear transformation from comparator coordinates into object space in close-range photogrammetry. Am. Soc. Photogramm. 1971, 1, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliaga, D.G. Accurate Catadioptric Calibration for Real- time Pose Estimation of Room-size Environments. In Proceedings of the 2001 International Conference on Computer Vision, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 7–14 July 2001; pp. 127–134. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Hu, Z. Geometric invariants and applications under catadioptric camera model. In Proceedings of the 2005 International Conference on Computer Vision, Beijing, China, 17–21 October 2005; pp. 1547–1554. [Google Scholar]

- Luis, P.; Bermudez, J.; Peter, S.; Guerrero, J.J. Calibration of omnidirectional cameras in practice: A comparison of methods. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 2012, 116, 120–137. [Google Scholar]

- Thirthala, S.R.; Plllefeys, M. Radial multi-focal tensors. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2012, 96, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyer, C.; Daniilidis, K. Catadioptric camera calibration. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer Vision, Corfu, Greece, 20–25 September 1999; pp. 398–404. [Google Scholar]

- Swaminathan, R.; Nayar, S.K. Nonmetric calibration of wide-angle lenses and poly cameras. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2000, 22, 1172–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyer, C.; Daniilidis, K. Para catadioptric Camera Calibration. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2002, 24, 687–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, J.P.; Araujo. Paracatadioptric Camera Calibration Using Lines. IEEE Int. Conf. Comput. Vis. 2003, 2, 1359–1365. [Google Scholar]

- Ying, X.; Hu, Z. Catadioptric camera calibration using geometric invariants. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2004, 10, 1260–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasseur, P.; Mouaddib, E.M. Central catadioptric line detection. In Proceedings of the 15th British Machine Vision Conference, London, UK, 7–9 September 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Vandeportaele, B.; Cattoen, M.; Marthon, P.; Gurdjos, P. A New Linear Calibration Method for Para catadioptric Cameras. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR’06), Hong Kong, China, 20–24 August 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Caglioti, V.; Taddei, P.; Boracchi, G.; Gasparini, S.; Giusti, A. Single-image calibration of off-axis catadioptric cameras using lines. In Proceedings of the 11th IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 14–20 October 2007; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, F.; Duan, F.; Hu, Z.; Wu, Y. A new linear algorithm for calibrating central catadioptric cameras. Pattern Recognit. 2008, 41, 3166–3172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakstein, H.; Pajdla, T. Panoramic mosaicking with a 180 field of view lens. In Proceedings of the IEEE Workshop on Omnidirectional Vision, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2 June 2002; pp. 60–67. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, C.; Su, L.; Zhu, F.; Shi, Z. A versatile method for omnidirectional stereo camera calibration based on BP algorithm. Optoelectron. Inf. Technol. Res. Lab. 2006, 3972, 383–389. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, X.M.; Wu, F.C.; Wu, Y.H. An easy calibration method for central catadioptric cameras. Acta Autom. Sin. 2007, 33, 801–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparini, S.; Sturm, P.; Barreto, J.P. Plane-based calibration of central catadioptric cameras. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Computer Vision, Kyoto, Japan, 23–25 September 2009; pp. 1195–1202. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Matsushita, Y.; Ma, Y. Camera calibration with lens distortion from low-rank textures. CVPR 2011, 2011, 2321–2328. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Liang, X.; Ganesh, A.; TILT, Y.M. Transform Invariant Low-rank Textures. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2012, 99, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, Y.; Gao, Y. Research on panoramic camera calibration and application based on Halcon. Comput. Eng. Appl. 2016, 52, 241–246. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, S.H. Research on Camera Calibration Method in Vehicle Panoramic Vision Systems. Master’s Thesis, Wuhan University, Wuhan, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hartley, R.; Kang, S.B. Parameter-free radial distortion correction with Centre of distortion estimation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2007, 29, 1309–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toepfer, C.; Ehlgen, T. A unifying omnidirectional camera model and its applications. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Computer Vision, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 14–20 October 2007; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Luong, Q.; Maybank, S.J. Camera self-calibration: Theory and experiments. In Proceedings of the 1992 European Conference on Computer Vision, London, UK, 19–22 May 1992; pp. 321–334. [Google Scholar]

- Hartley, R.I. Self-calibration from multiple views with a rotating camera. In Proceedings of the 1994 European Conference on Computer Vision, Stockholm, Sweden, 2–6 May 1994; pp. 471–478. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, G.P. Accurate internal camera calibration using rotation, with analysis of sources of error. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Computer Vision, Cambridge, MA, USA, 20–23 June 1995; pp. 230–236. [Google Scholar]

- Ramalingam, S.; Sturm, P.; Lodha, S.K. Generic self-calibration of central cameras. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 2010, 114, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espuny, F.; Gil, J.I.B. Generic self-calibration of central cameras from two rotational flows. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2011, 91, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triggs, B. Auto calibration and absolute quadric. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, San Juan, PR, USA, 7–19 June 1997; pp. 604–614. [Google Scholar]

- Liebowitz, D. Metric rectification for perspective images of planes. In Proceedings of the 1998 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 25–25 June 1998; pp. 482–488. [Google Scholar]

- Caprile, B.; Torre, V. Using vanishing points for camera calibration. Int. J. Comput. Vision. 1990, 4, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viola, P.; Jones, M. Fast and Robust Classification using Asymmetric AdaBoost and a Detector Cascade. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Denver, CO, USA, 3–8 December 2001; pp. 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Micusik, B.; Pajdla, T. Estimmion of omnidirectional camera model from Epipolar geometry. CVPR 2003, 200, 485–490. [Google Scholar]

- Maybank, S.J.; Faugeras, O.D. A theory of self-calibration of a moving camera. Int J Comput. Vision. 1992, 8, 123–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strecha, C.; van Hansen, W.; Gool, L.V.; Fua, P.; Thoennessen, U. On benchmarking camera calibration and multi-view stereo for high resolution imagery. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE Conferenc on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Anchorage, AK, USA, 23–28 June 2008, pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa, Y.; Ponce, J. Accurate camera calibration from multi-view stereo and bundle adjustment. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Anchorage, AK, USA, 23–28 June 2008; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, D.Z. Design of High Definition 360-Degree Camera-Design of Panoramic Vision Processing Software Based on DaVinci. Master’s Thesis, Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Nanjing, China, June 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Swaminathan, R.; Nayar, S.K. Non-metric calibration of wide-angle lenses and polycameras. In Proceedings of the 1999 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Fort Collins, CO, USA, 23–25 June 1999; pp. 413–419. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, K.H.; Kim, Y.; Kim, C. Analysis of Fish-Eye Lens Camera Self-Calibration. Sensors 2019, 19, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morel, O.; Stolz, C.; Meriaudeau, F.; Gorria, P. Active lighting applied to three-dimensional reconstruction of specular metallic surfaces by polarization imaging. Appl. Opt. 2006, 45, 4062–4068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ainouz, S.; Morel, O.; Fofi, D.; Mosaddegh, S.; Bensrhair, A. Adaptive processing of catadioptric images using polarization imaging: Towards a pola-catadioptric model. Opt. Eng. 2013, 52, 037001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Huang, X.; Bai, J.; Liang, R. Compact polarization-based dual-view panoramic lens. Appl. Opt. 2017, 56, 6283–6287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z. Research on Ultra-Wide Angle Lens Design and Distortion Correction Algorithm. Master’s Thesis, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Duane, C.B. Close-range camera calibration. Photogramm. Eng. 1971, 37, 855–866. [Google Scholar]

- S1ama, C.C. Manual of Photogrammetry, 4th ed.; American Society of Photogrammetry: Falls Church, VA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, G.Q.; De Ma, S. Implicit and explicit camera calibration-theory and experiments. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1994, 16, 469–480. [Google Scholar]

- Heikkila, J.; Silvén, O. A four-step camera calibration procedure with implicit image correction. In Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, San Juan, PR, USA, 17–19 June 1997; pp. 1106–1112. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, S.; Aggarwal, J.K. A simple calibration procedure for fish-eye (high distortion) lens camera. In Proceedings of the 1994 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, San Juan, PR, USA, 8–13 May 1994; pp. 3422–3427. [Google Scholar]

- Devernay, F.; Faugeras, O.D. Automatic calibration and removal of distortion from scenes of structured environments. Investig. Trial Image Process. 1995, 2567, 62–72. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgibbon, A.W. Simultaneous linear estimation of multiple view geometry and lens distortion. In Proceedings of the 2001 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Kauai, HI, USA, 8–14 December 2001; p. I. [Google Scholar]

- Mallon, J.; Whelan, P.F. Precise radial un-distortion of images. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Pattern Recognition, Cambridge, UK, 26–26 August 2004; pp. 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, M.; Farag, A. Nonmetric calibration of camera lens distortion: Differential methods and robust estimation. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2005, 14, 1215–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, C.; Denny, P.; Jones, E.; Glavin, M. Accuracy of fish-eye lens models. Appl. Opt. 2010, 49, 3338–3347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prescott, B.; McLean, G.F. Line-based correction of radial lens distortion. Graph. Models Image Process. 1997, 59, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, J.; Santos-victor, J. Visual path following with a catadioptric panoramic camera. Int. Symp. Um Intell. Robot. Syst. 1999, 139–147. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, M.T.; Farag, A. Differential methods for non-metric calibration of camera lens distortion. In Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Kauai, Hawaii, 8–14 December 2001; pp. 477–482. [Google Scholar]

- Ishii, C.; Sudo, Y.; Hashimoto, H. An image conversion algorithm from fish eye image to perspective image for human eyes. In Proceedings of the 2003 IEEE/ASME International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Mechatronics, Kobe, Japan, 20–24 July 2003; pp. 1009–1014. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, Z.Q.; Lu, H.W.; Yu, Q.; Feng. Correction of fish eye lens distortion by Projective Invariance. Appl. Opt. 2003, 24, 36–38. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, J.Y.; SU, X.Y. Elimination of the lens distortion in catadioptric omnidirectional distortion less imaging systems for horizontal scene. Acta Opt. Sin. 2004, 24, 730–734. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.Q. Research on Omnidirectional Machine Vision Based on Fisheye Lens. Master’s Thesis, Department of Mechanical and Electronic Engineering, Tianjin University of Technology, Tianjin, China, June 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, W.J. Research and Development of Embedded Omnidirectional Visual Tracker. Master’s Thesis, Department of Mechanical and Electronic Engineering, Tianjin University of Technology, Tianjin, China, June 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, X.; Yang, G.G.; Bai, J. Distortion correction of circular lens based on spherical perspective projection constraint. Acta Opt. Sinical. 2008, 28, 675–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.Q.; Cao, Z.L. Omnidirectional Image Restoration Using a Support Vector Machine. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE International Conference on Information and Automation, Changsha, China, 20–23 June 2008; pp. 606–611. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, R.; Agrawala, M.; Agarwala, A. Optimizing content-preserving projections for wide-angle images. ACM Trans. Graph. 2009, 28, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Gong, L.; Zhu, M.; Ding, X.; Teng, R.K. FPGA implementation of reflective panoramic video real-time planar display technology. Appl. Electron. Technol. 2011, 37, 45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Maybank, S.J.; Ieng, S.; Benosman, R. A fisher- Rao metric for Para catadioptric images of lines. Inc. Compute. Vis. 2012, 99, 147–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanatani, K. Calibration of Ultrawide Fisheye Lens Cameras by Eigenvalue Minimization. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2013, 35, 813–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, X.; Lin, Z.C. Linearized alternating direction method with adaptive penalty and warm starts for fast solving transform invariant low-rank textures Source. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2013, 104, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.Y.; Li, Q.; Zhang, B.Z. Fisheye distortion checkerboard image correction. Comput. Eng. Appl. 2014, 50, 111–114. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Hu, Z.; Li, Y. Radial distortion invariants and lens evaluation under a single-optical-axis omnidirectional camera. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 2014, 126, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.Z. Parametric distortion-adaptive neighborhood for omnidirectional camera. Appl. Opt. 2015, 54, 6969–6978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Xiong, W.; Chen, H.; Chen, Y.; Dai, Q.; Tu, P.; Hu, G. Fish eye image distortion correction method based on double longitude model. Acta Instrum. Sin. 2015, 36, 377–385. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, S.H.; Zhou, L.L.; Yu, H.S. Sparse Bayesian learning for image rectification with transform invariant low-rank textures. Signal Process. 2017, 137, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xu, S. Research on Image Processing Technology of Computer Vision Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Computer Vision, Image and Deep Learning (CVIDL), Chongqing, China, 10–12 July 2020; pp. 122–124. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, Y.F.; Zhu, Q.D.; Wu, Z.X.; Zhang, Z. Implementation and improvement of cylindrical theory expansion algorithm for panoramic vision image. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2006, 33, 4–6. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.G.; Qian, H.L.; Mei, X.; Xu, J.F. Research on cylindrical solution of hyperboloid catadioptric panoramic image. Comput. Eng. 2010, 36, 204–206. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.P.; He, B.W. A modified unwrapping method for omnidirectional images. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Electric Information and Control Engineering, Wuhan, China, 15–17 April 2011; pp. 52–55. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.J.; Chen, C.; Miao, L.G.; Liu, X.C. Study of Key Technology of Distortion Correction Software for Fisheye Image. Instrum. Tech. Sens. 2011, 40, 100–105. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, S.; Wang, F. Generation of Panoramic View from 360 Degree Fisheye Images Based on Angular Fisheye Projection. International Symposium on Distributed Computing and Applications to Business. Eng. Sci. IEEE Comput. Soc. 2011, 135, 187–191. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. Correction and Expansion of Super Large Wide Angle Distortion Image. Master’s Thesis, Tianjin University of Technology, Tianjin, China, January 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, L.B. Design of Intelligent 3D Stereo Camera Equipment Based on 3D Panoramic Vision. Master’s Thesis, Zhejiang University of Technology, Hangzhou, China, June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, C.; Wu, K.; Liu, Q.; Cheng, H.; Ma, Q. Panoramic multi-target real-time detection based on improved Yolo algorithm. Comput. Eng. Des. 2018, 39, 3259–3264. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y.M. Research and Implementation of Omnidirectional Image Expansion Algorithm. Master’s Thesis, Zhejiang University of Technology, Hangzhou, China, June 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, J.; Du, X.; Zhu, Y.F.; Liu, J.L. Omnidirectional image expansion based on Taylor model. Chin. J. Image Graph. 2010, 15, 1430–1435. [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar, J.; Deccó, C.; Okamoto, J.; Santos-Victor, J. Constant resolution omnidirectional cameras. In Proceedings of the IEEE Workshop on Omnidirectional Vision 2002. Held in Conjunction with ECCV’02, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2 June 2002; pp. 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Pi, W.K. Motion Detection for Human Bodies Basing Adaptive Background Subtraction by Using an Omnidirectional Camera. Acta Sci. Nat. Univ. Pekineses 2004, 40, 458–464. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, H.J.; Bai, J.; Yang, G.G. Research on the expansion algorithm of two-dimensional planar imaging with panoramic annular lens. Acta Photonica Sin. 2006, 11, 1686–1688. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Z.L.; Wang, J.Z. Expansion and correcting method of catadioptric panoramic reconnaissance image. J. Missile Guid. 2010, 30, 173–176. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.M.; Zhang, X.K. A new method of panoramic image expansion. Sci. Technol. Inf. 2014, 2, 19–20. [Google Scholar]

- Du, E.Y.; Zhang, N.; Li, Y.D. Fast Lane detection method based on Gabor filter. Infrared Laser Eng. 2018, 47, 304–311. [Google Scholar]

- Hiroshi, K.; Jun, M.; Yoshiaki, S. Recognizing Moving Obstacles for Robot Navigation using Real-time Omnidirectional Stereo Vision. J. Robot. Mechatron. 2002, 14, 147–156. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W. Research on Modeling and Rendering Technology of Dynamic Virtual Environment Based on Catadioptric Panorama. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Defense Science and Technology, Changsha, China, June 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.X. A Study of Single CCD Panoramic Imaging Systems Based on Optical Mirror. Master’s Thesis, Changchun University of Technology, Changchun, China, June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Benosman, R.; Kang, S.; Faugeras, O. Panoramic Vision. In Sensors Theory and Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, Z.H.; Xu, W.; Wang, W.; Zhang, M.J.; Liu, S.H. Eight direction symmetric reuse strategy to reduce the look-up table space of panoramic image table expansion method. Minicomput. Syst. 2007, 28, 1832–1836. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.Y.; Lu, M.; Yong, S.W. Design and implementation of radar PPI raster scanning display systems. J. Natl. Def. Univ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 29, 65–68. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Xiong, Z.H.; Cheng, G.; Chen, L.D.; Zhang, M.J. Real time development of catadioptric panoramic image based on FPGA. Comput. Appl. 2008, 28, 3135–3137. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Yang, D.Y.; Shi, X.F. Parallel optimization of omnidirectional image expansion. Comput. Eng. Des. 2010, 31, 4862–4865. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, S.T. FPGA Implementation of High-Resolution Panoramic Image Processing Algorithm. Master’s Thesis, Harbin University of Technology, Harbin, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, W.; Han, J.F.; Zheng, Y.Y.; Tang, Y. Panoramic video multi-target real-time detection based on DSP. Optoelectron. Eng. 2014, 5, 68–76. [Google Scholar]

- Jaramillo, C.; Valenti, R.G.; Guo, L.; Xiao, J. Design and Analysis of a Single−Camera Omni stereo Sensor for Quadrotor Micro Aerial Vehicles (MA Vs). Sensors 2016, 6, 17. [Google Scholar]

| Number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 11.14 ± 08.03 | 4.43 ± 4.12 | 4.45 ± 4.48 | 2.92 ± 2.83 | 686.25 ± 337.40 |

| 2 | 12.59 ± 09.20 | 3.57 ± 3.06 | 3.26 ± 2.75 | 2.65 ± 2.47 | 812.85 ± 193.04 |

| 3 | 16.80 ± 09.92 | 4.47 ± 4.14 | 4.57 ± 4.38 | 3.05 ± 2.98 | 692.68 ± 322.51 |

| 4 | 11.72 ± 07.74 | 3.70 ± 3.52 | 3.51 ± 3.70 | 2.70 ± 2.29 | 615.23 ± 150.67 |

| 5 | 09.27 ± 06.73 | 3.44 ± 3.18 | 3.28 ± 3.46 | 2.61 ± 2.16 | 618.64 ± 147.67 |

| 6 | 08.52 ± 06.33 | 3.31 ± 3.21 | 3.13 ± 3.23 | 2.54 ± 2.17 | 618.98 ± 147.22 |

| 7 | 08.19 ± 06.45 | 3.19 ± 3.02 | 3.04 ± 3.05 | 2.58 ± 2.30 | 613.62 ± 148.42 |

| 8 | 17.66 ± 13.75 | 4.89 ± 3.40 | 5.26 ± 3.49 | 1.46 ± 1.32 | NaN ± Nan |

| 9 | 09.10 ± 06.80 | 3.19 ± 2.74 | 3.02 ± 2.81 | 2.69 ± 2.49 | 602.15 ± 150.47 |

| n | Sum of Total Weight Projection Error Square | Average Reprojection Error |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 94955.682 | 11.666 |

| 2 | 11290.089 | 3.798 |

| 3 | 11526.951 | 3.72 |

| 4 | 5340.762 | 2.57 |

| 5 | NaN | NaN |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guo, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, Z. Research on Design, Calibration and Real-Time Image Expansion Technology of Unmanned System Variable-Scale Panoramic Vision System. Sensors 2021, 21, 4708. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21144708

Guo X, Wang Z, Zhou W, Zhang Z. Research on Design, Calibration and Real-Time Image Expansion Technology of Unmanned System Variable-Scale Panoramic Vision System. Sensors. 2021; 21(14):4708. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21144708

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Xiaodong, Zhoubo Wang, Wei Zhou, and Zhenhai Zhang. 2021. "Research on Design, Calibration and Real-Time Image Expansion Technology of Unmanned System Variable-Scale Panoramic Vision System" Sensors 21, no. 14: 4708. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21144708

APA StyleGuo, X., Wang, Z., Zhou, W., & Zhang, Z. (2021). Research on Design, Calibration and Real-Time Image Expansion Technology of Unmanned System Variable-Scale Panoramic Vision System. Sensors, 21(14), 4708. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21144708