Time Orientation Technologies in Special Education †

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Aims and Scope

1.2. Previous Works and State of the Art

1.2.1. Human Time Orientation Capacities

1.2.2. Importance of Time Orientation Intervention

1.2.3. Other Works in Time Orientation Intervention

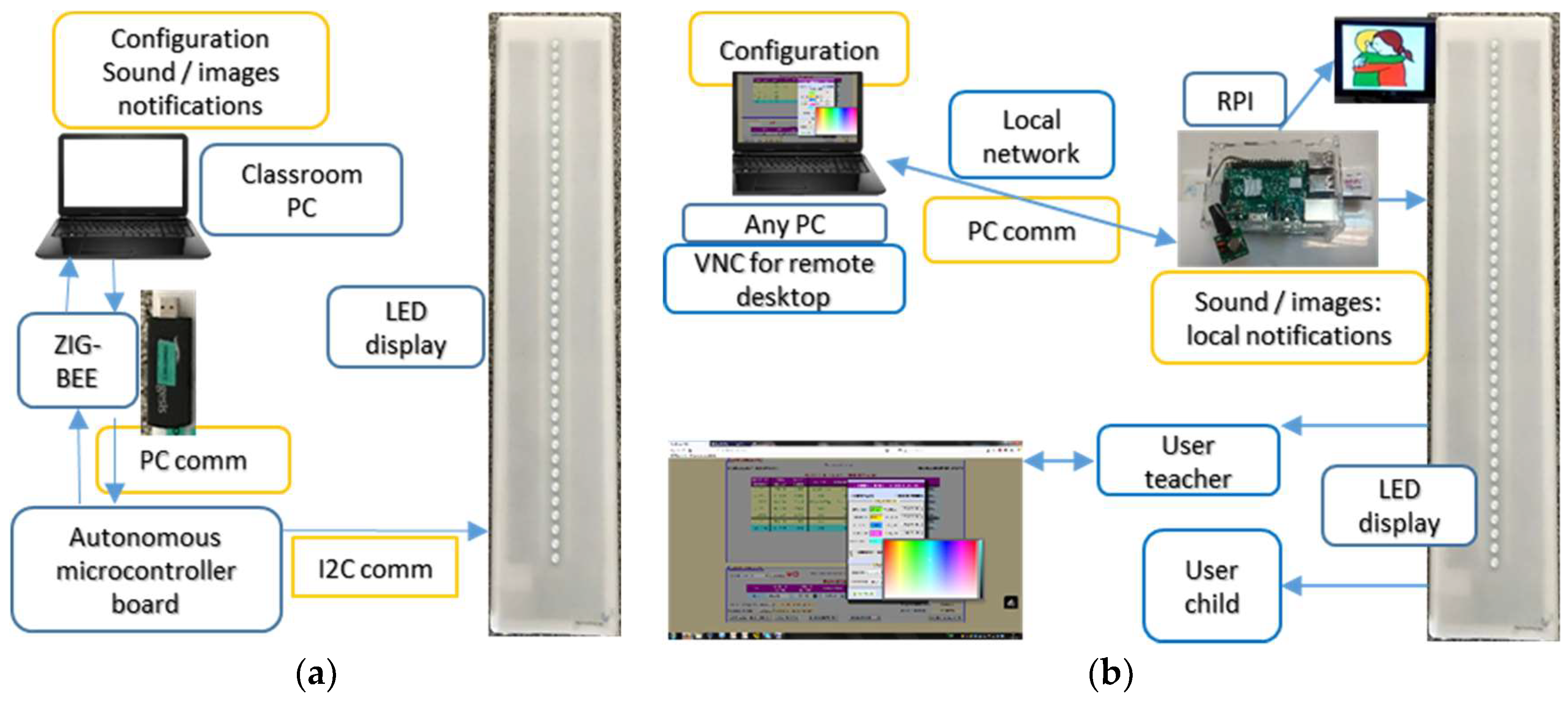

2. Time Orientation Technology Description

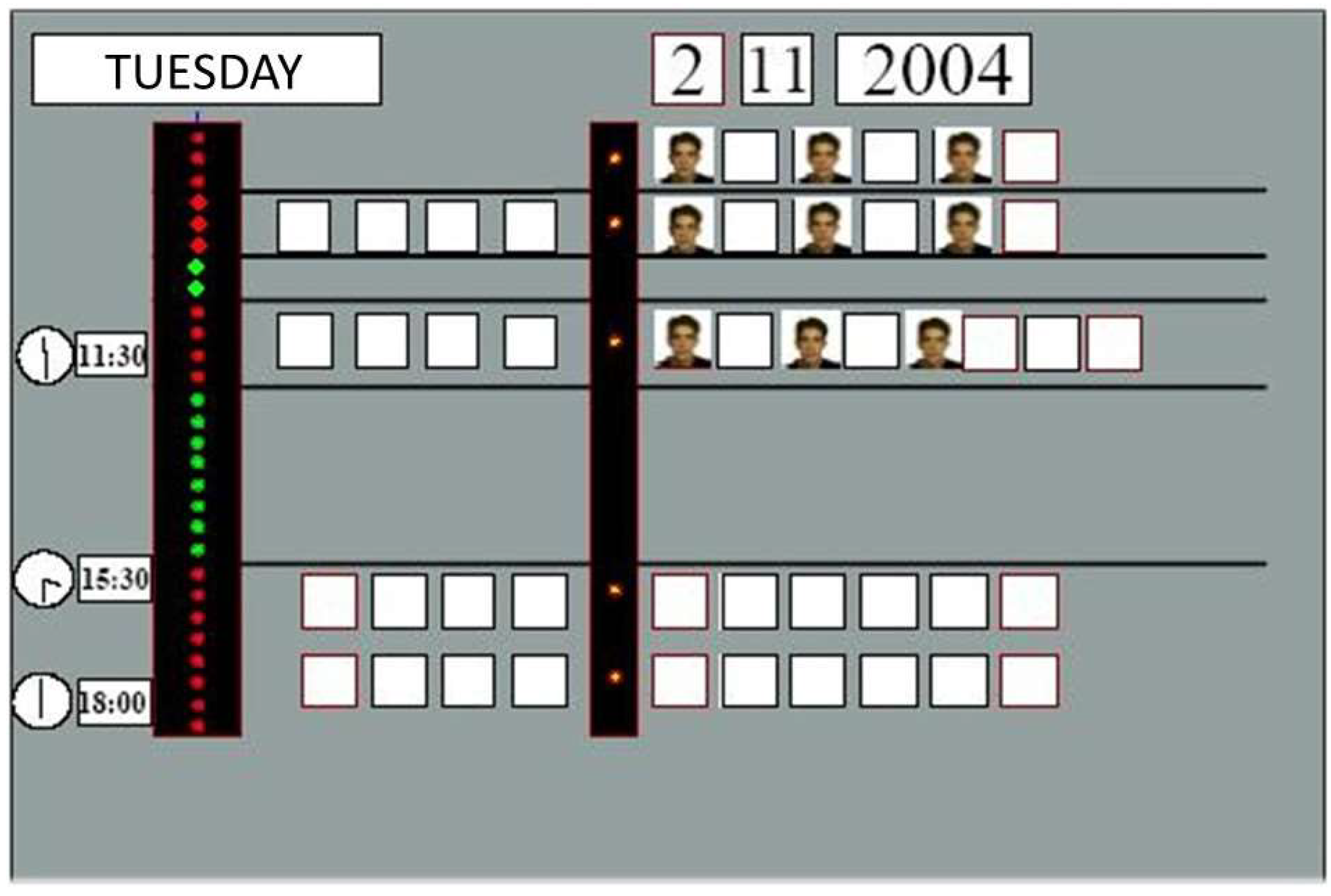

2.1. System Evolution

- -

- A physical display in a long white plastic box with a row of several (40) luminous elements, with area at both sides to attach pictograms glued to magnets;

- -

- A single-board computer which is attached to the display, in which the software runs;

- -

- A speaker for melody or voice messages associated;

- -

- A screen to show the pictogram of the current action or a simple pictogram sequence;

- -

- The software package to program the agenda and configure played and displayed information.

2.2. Prototype Description

2.2.1. Electronics

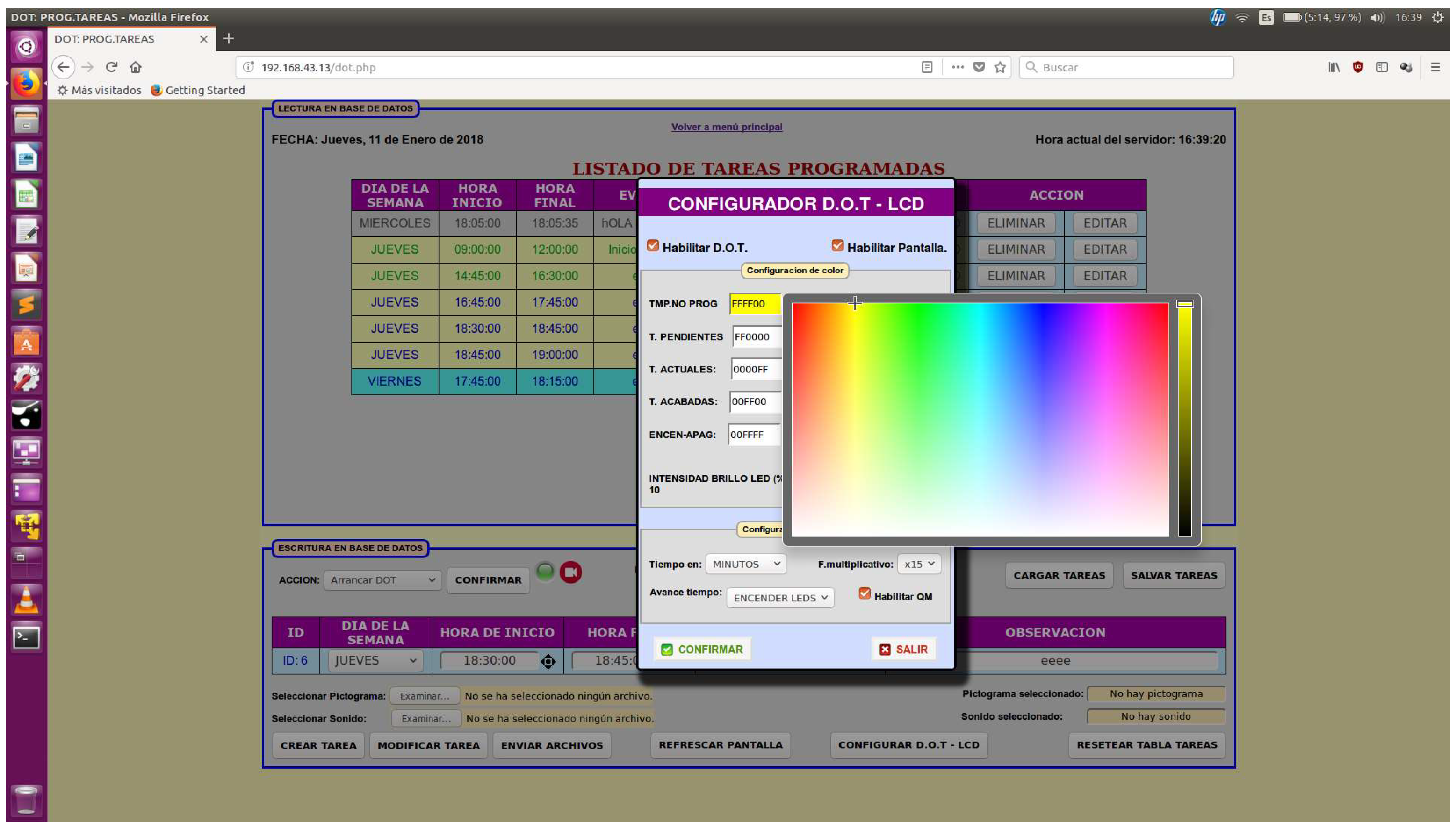

2.2.2. Software

2.2.3. Communications

2.2.4. User Interface Description

3. Evaluation

3.1. Summary

3.2. Methodology Goals, Constraints and Overall Description

3.3. Participants

3.3.1. Selection Process

3.3.2. Special Education Schools and Classes

- (1)

- Four classes with two children per TOD;

- (2)

- Eight classes with one child per TOD;

- (3)

- A total of 16 children have used TOD in their daily school routines, during 3.5 months.

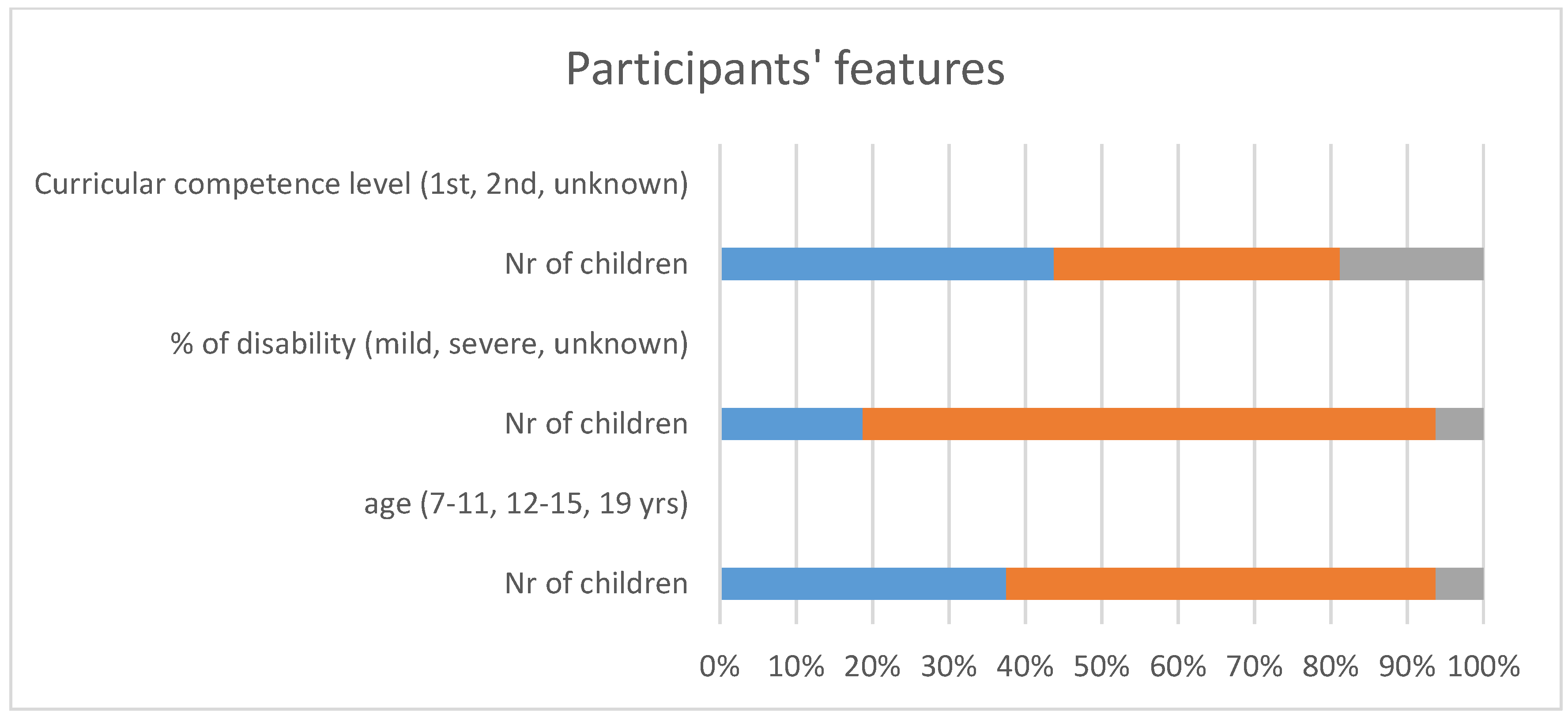

3.3.3. Participants Description

3.4. Evaluation Process

- -

- Project presentation to school direction boards.

- -

- Project presentation to teachers. Selection of candidates both children and teachers.

- -

- Data retrieving from selected children. Translation into ICF.

- -

- Training to teachers: group activity.

- -

- Installation of TOD’s in the classrooms.

- -

- Individual training and reinforcement, direct and telephone assistance.

- -

- First ICF assessment of use of TOD in class.

- -

- Use of TOD as planned, observations registered by teachers.

- -

- Second ICF assessment of use of TOD in class.

- -

- Teachers interviews regarding functionality and usability of device in the class.

- -

- Debate group: group meeting in which incidences are put in common, solutions applied, opinions shared about TOD as educative resource, repercussion of use of TOD over human behavior.

3.4.1. Manuals and Protocols

- -

- Install in a space which is as free as possible of other stimuli so perception is easier and with less error margin.

- -

- Situated in front or in diagonal of children’s place in the class, for visibility reasons.

- -

- Locate it in a place with no direct artificial or sunlight to avoid reflected light which could make difficult its discrimination.

- -

- The eye-height of children should be in the middle of the device.

3.4.2. Usage Incidences

3.5. Assessment Test Design, Based in ICF

- -

- Enormous variability of users and their behavior and difficulties which greatly depend on their level of well-being through the day.

- -

- Short time scope available. Available action took 4-5 months with holidays in between, which is considered not enough to have stable modifications in changes and tendencies that some users presented.

- -

- Selection process leaves experiment with few candidates, so we have a wide age range and a relatively small number of participants which only allows an approximation to individual results.

- (1)

- Learning and applying knowledge.

- (2)

- General tasks and demands.

- (3)

- Communication.

- (4)

- Mobility.

- (5)

- Self-care.

- (6)

- Daily life.

- (7)

- Interactions and interpersonal relations.

- (8)

- Main areas in life.

- (9)

- Community, social and civic life.

- (1).

- Learning and applying knowledge:

- A.

- Sensory experiences with intention

- 1-

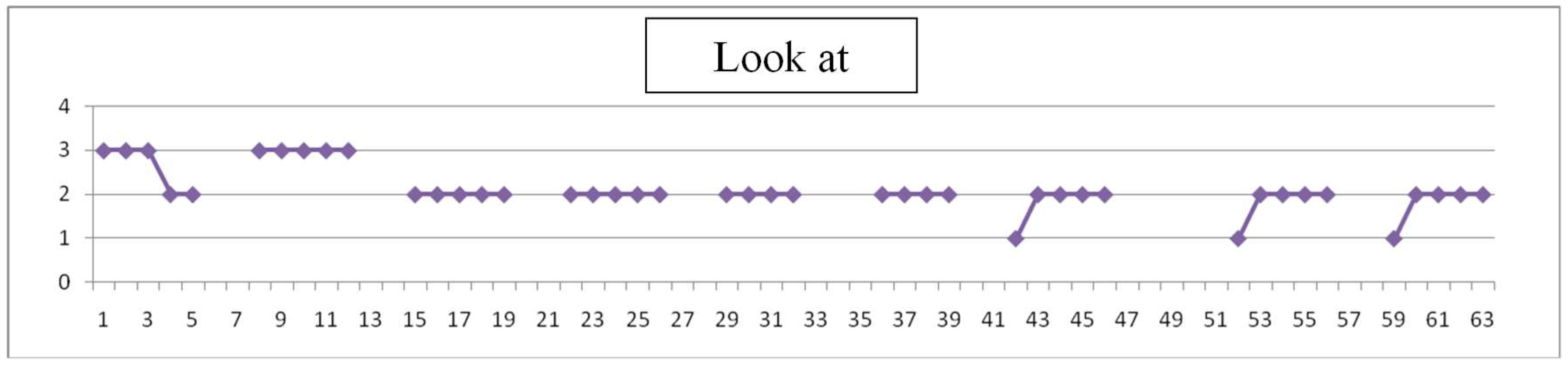

- Look at: set the looking intentionally towards the interface.

- 2-

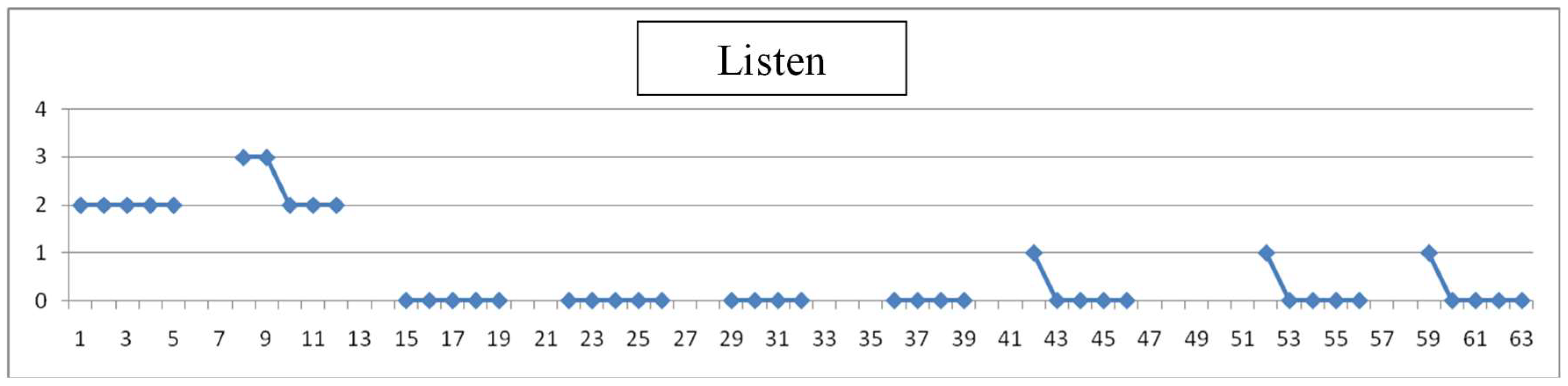

- Listen: sound perception and set the looking towards the source

- B.

- Basic learning:

- 3-

- Basic skills acquisition: to become capable of executing indicated actions.

- C.

- Knowledge application:

- 4-

- Centering attention: Focus intentionally the attention on stimuli while they happen.

- 5-

- Solve simple problems: To take exploratory actions and/or find solutions to achieve an objective.

- (2).

- General tasks and demands:

- 6-

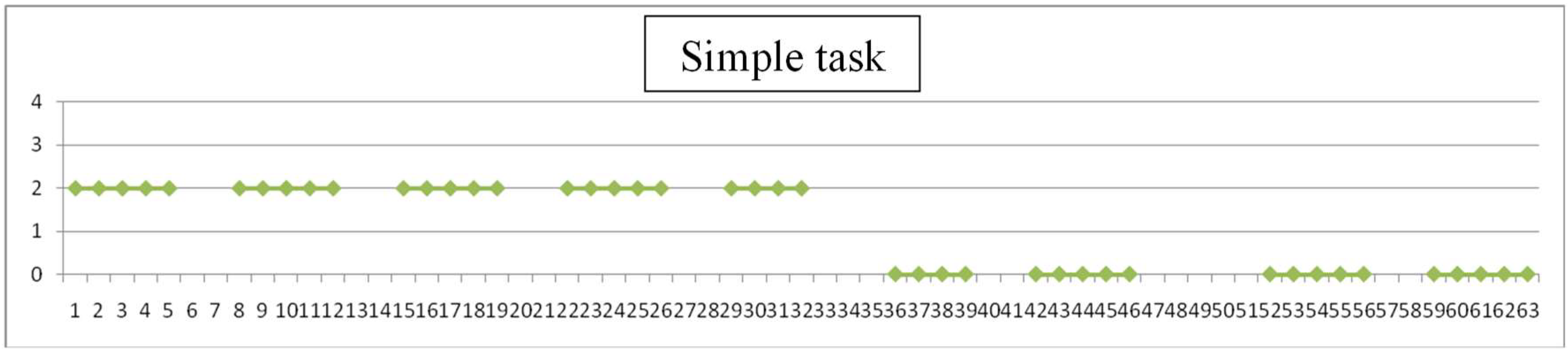

- To carry out a simple task: Execute a task after receiving the notification.

- 7-

- Complete daily routines: establish and fix time patterns and sequences from TOD notifications.

- 8-

- Stress management: keep a behavior inside tolerable margins during TOD process

- (3).

- Communication:

- A.

- Communication—reception

- 9-

- Spoken messages communication-reception: understand teacher’s comments and from others if they were.

- 10-

- Symbols and signals communication-reception: Understand the meaning of symbols and auditory stimuli.

- B.

- Communication—production

- 11-

- Speak: in an understandable way with communicative intention.

- 12-

- Non-verbal messages production: using signs, drawings or any other non-verbal messages to express him/herself and/or communicate something.

- (4).

- Mobility:

- 13-

- Walking short distances. Walk indoors with an aim.

- (7).

- Interactions and interpersonal relations:

- B.

- Particular interpersonal relations:

- 14-

- Relate with strangers: Establishing temporal links with strangers with specific purposes (in relation with evaluators).

- 15-

- Relate with people in authority position: keep a respect relationship with professionals

- 16-

- Informal relations with peers: with respect and affection

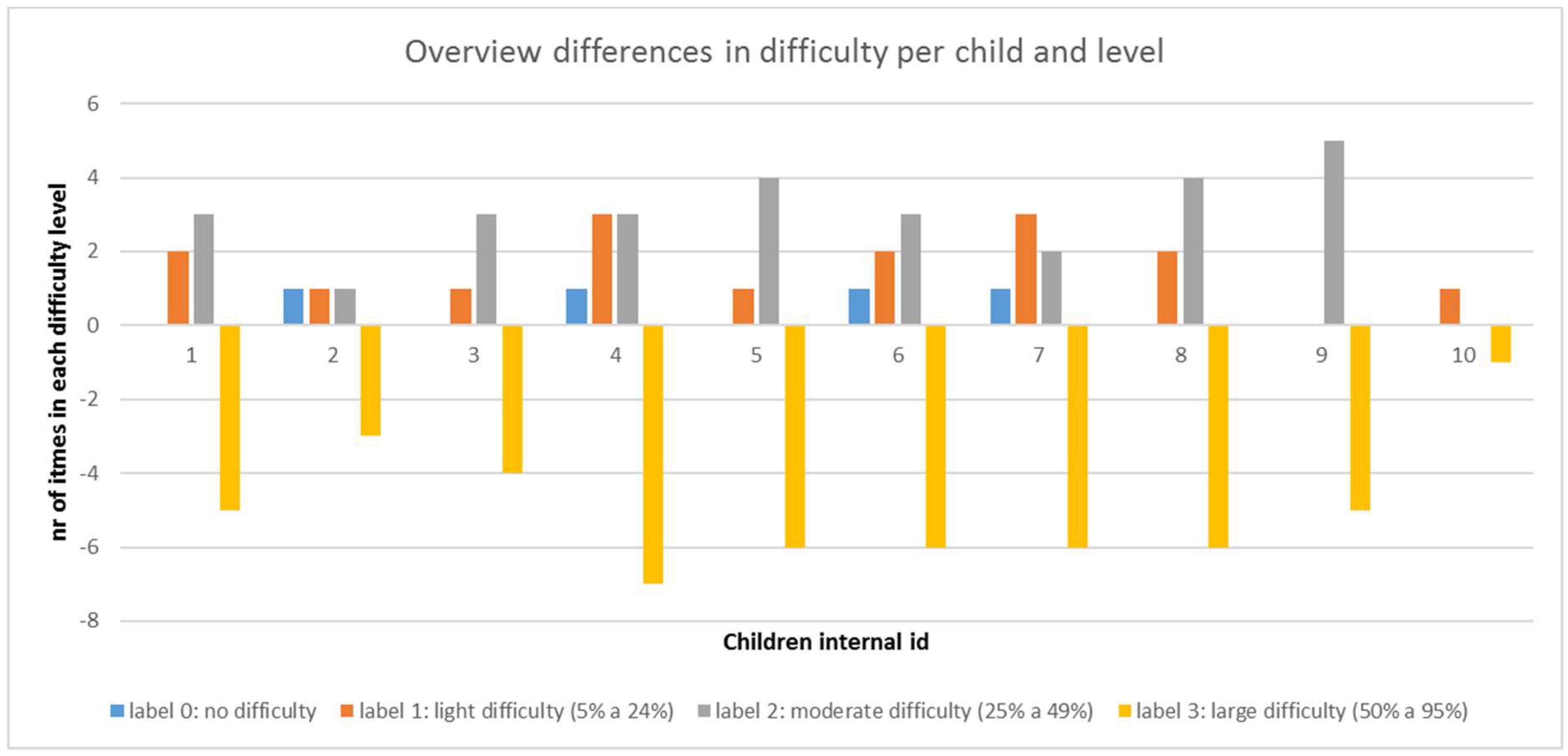

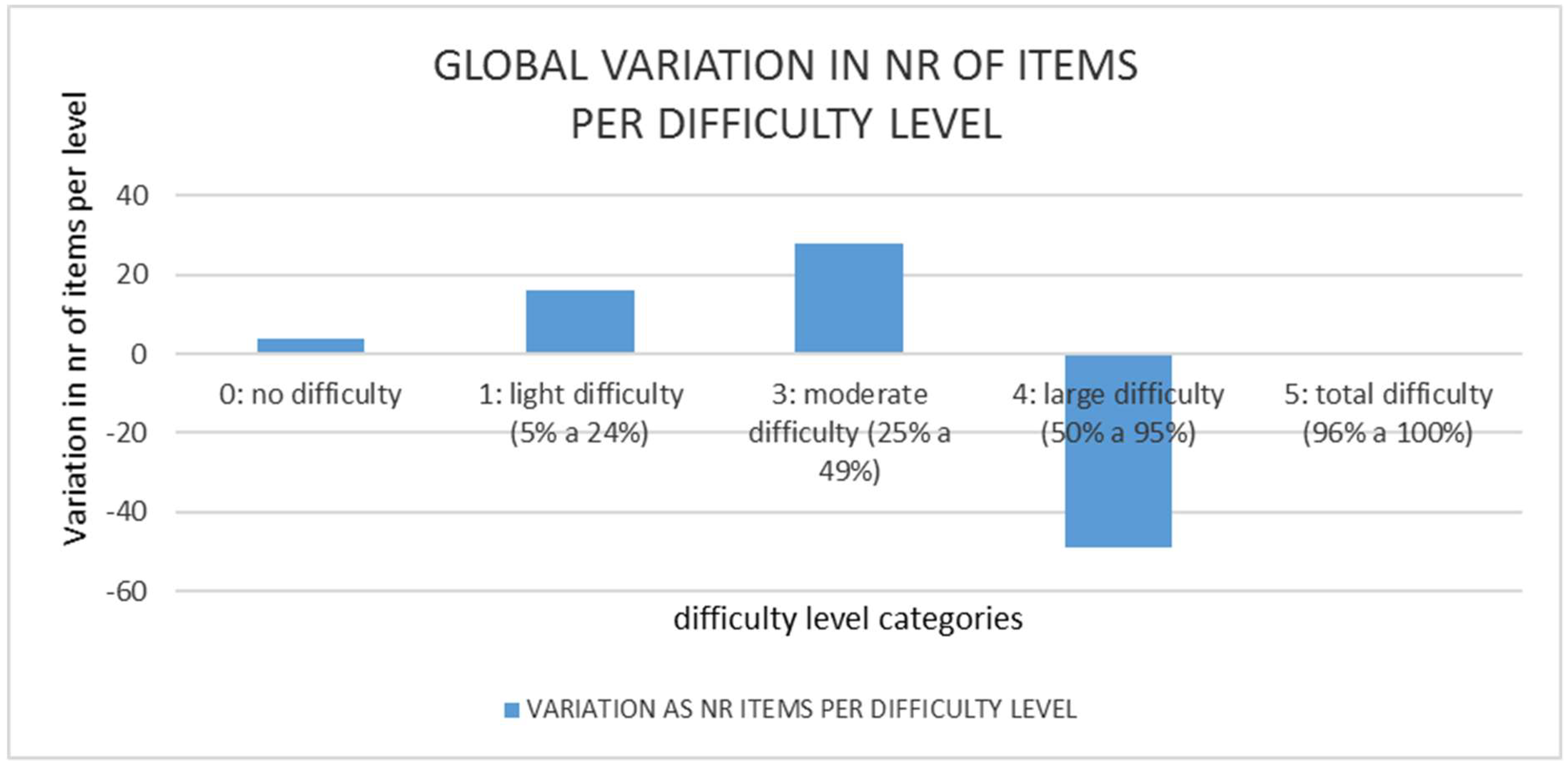

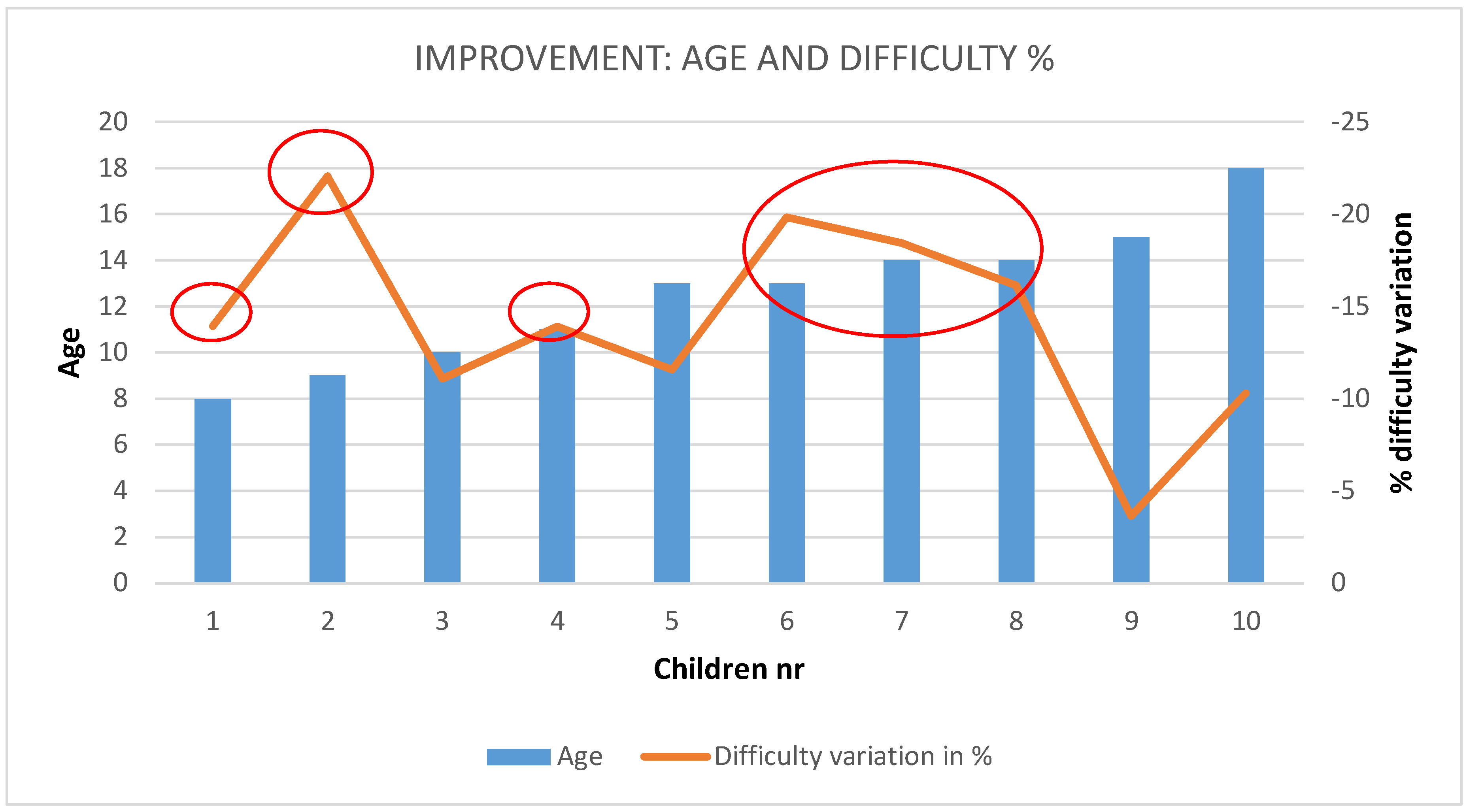

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. ICF Assessment

4.2. Individual Data and Results:

4.2.1. ICF Assessment

4.2.2. Observation Templates for Teachers

4.3. Overall Results

4.4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- CPEE Alborada Home Page. Available online: https://cpeealborada.wordpress.com (accessed on 21 January 2018).

- International Classification of Functioning; Disability and Health (ICF); World Health Organization (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2001; ISBN 84-8446-034-7.

- Janeslätt, G. Time for Time: Assessment of Time Processing Ability and Daily Time Management in Children with and without Disabilities. Ph.D. Thesis, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Janeslätt, G.; Granlund, M.; Kottorp, A. Measurement of time processing ability and daily time management in children with disabilities. Disabil Health J. 2009, 2, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Turrado, T.; Pascual-Millán, L.F.; Aguilar-Palacio, I.; Burriel-Roselló, A.; Santolaria-Martínez, L.; Pérez-Lázaro, C. Temporal orientation and cognitive impairment. Available online: https://neurología.com (accessed on 16 March 2011).

- Pierre, V.F.; Jean-Claude, U. A Cross-Cultural Comparison of Individual Time Orientations. In Proceedings of the 1993 World Marketing Congress. Developments in Marketing Science; Sirgy, M., Bahn, K., Erem, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Difabio de Anglat, H.; Maris Vázquez, S.; Noriega Biggio, M. Orientación temporal y metas vitales en estudiantes argentinos (Time orientation and vital goals in argentinian students). Rev. Psicol. 2018, 36, 661–700. [Google Scholar]

- Romero, M.; Barberà, E. Identificación de las dificultades de regulación del tiempo de los estudiantes universitarios en formación a distancia (Identification of difficulties in time regulation for university students in non-presential learning). Rev. Educ. Distancia 2013, 38. [Google Scholar]

- Ojeda, F.J.R.; Moyeda, I.X.G.; Velasco, A.S. Time Orientation, self-regulation and attainment of learning in academic efficiency in university students. Electron. J. Psichol. Iztacala 2017, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Wittmann, M.; Sircova, A. Dispositional orientation to the present and future and its role in pro-environmental behavior and sustainability. Heliyon 2018, 4, e00882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellà, J.; Minguell, G.; Muro Rodríguez, A.; Sotoca, C.; Estaún i Ferrer, S. Intervention based on Temporal Orientation to reduce alcohol consumption and enhance risk perception in adolescence. Quad. Psicol. 2018, 20, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maglio, S.J.; Trope, Y. Temporal orientation. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2019, 26, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmerón Pérez, H.; Gutierrez Braojos, C.; Rodríguez Fernández, S. The relationship of gender, time orientation and achieving self-regulated learning. J. Educ. Res. 2017, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ERA 5 Svensk, A. Design for Cognitive Assistance, Licentiate, Certec—Rehabilitation Engineering and Design; Lund University Publications: Lund, Sweden, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson, C.; Svensk, A. A research method using technology as a language for describing the needs both of people with intellectual disabilities and people with brain injuries. In Proceedings of the 2nd European Conference on the Advancement of Rehabilitation Technology (ECART 2), Stockholm, Sweden, 26–28 May 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Rehabilitation Engineering Research Lund Institute of Technology. CERTEC Home Page. Available online: http://www.certec.lth.se/english (accessed on 21 January 2018).

- Web site of Abilia (Developing Assistive Technology for People with Cognitive Disabilities Based on Their Cognitive Abilities). Abilia Home Page. Available online: http://www.abilia.com/en (accessed on 4 June 2019).

- LoPresti, E.F.; Mihailidis, A.; Kirsch, N. Assistive technology for cognitive rehabilitation: State of the art. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 2004, 14, 5–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvidsson, G.; Jonsson, H. The impact of time aids on independence and autonomy in adults with developmental disabilities. Occup. Ther. Int. 2006, 13, 160–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janeslatt, G.; Kotorp, A.; Granlund, M. Evaluating intervention using time aids in children with disabilities. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2013, 21, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quarter Hour Watch. Available online: http://ftp.zygo-usa.com/qhw.html (accessed on 2 June 2019).

- TimeTimer. Available online: http://www.timetimer.com/ (accessed on 2 June 2019).

- WatchMinder. Available online: https://www.watchminder.com/ (accessed on 2 June 2019).

- TimeCue. Available online: https://www.attainmentcompany.com/timecue (accessed on 2 June 2019).

- ISAAC. Available online: http://www.cosys.us/index.htm (accessed on 2 June 2019).

- Gorman, P.; Dayle, R.; Hood, C.A.; Rumrell, L. Effectiveness of the ISAAC cognitive prosthetic system for improving rehabilitation outcomes with neurofunctional impairment. NeuroRehabilitation 2003, 18, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- TICO: Editor of Messages with Pictograms. Available online: http://www.arasaac.org/materiales.php?id_material=1958 (accessed on 2 June 2019).

- Arasaac Pictogram Catalog. Available online: http://www.arasaac.org/catalogos.php (accessed on 2 June 2019).

- Keating, T. Picture Planner: An Icon-Based Personal Management Application for Individuals with Cognitive Disabilities. In Proceedings of the 8th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility, ASSETS 2006, Portland, OR, USA, 23–25 October 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Keating, T. Picture Planner: An Icon-Based Personal Management Application for Individuals with Cognitive Disabilities. Available online: https://www.cs.ubc.ca/~joanna/CHI2006Workshop_CognitiveTechnologies/positionPapers/5_Keating%20CHI%2006.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2019).

- Student Occupational Time Line. Available online: http://www.school-readytherapy.com/sotl.html (accessed on 2 June 2019).

- Time Management Apps. Available online: https://www.educationalappstore.com/best-apps/best-time-management-apps-for-parents (accessed on 2 June 2019).

- Time Management Apps for Kids. Available online: https://www.commonsensemedia.org/lists/top-time-management-apps (accessed on 2 June 2019).

- Falcó, J.L.; Muro, C.; Plaza, I.; Roy, A. Temporal Orientation Panel for Special Education. In Computers Helping People with Special Needs; Miesenberger, K., Klaus, J., Zagler, W.L., Karshmer, A.I., Eds.; ICCHP, LNSC; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; Volume 4061. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco, T.; Asensio, A.; Cirujano, D.; Marco, A.; Falcó, J.L.; Casas, R. Time Orientation Device for people with disabilities: Do you want to assess it? In Proceedings of the 26th Annual International Technology & Persons with Disabilities Conference, San Diego, CA, USA, 14–19 March 2011.

- Guillomía, M.A.; Falcó, J.L.; Artigas, J.I.; Sánchez, A. AAL platform with a ‘de facto’ standard communication interface (TICO): Training in home control in special education. Sensors 2017, 17, 2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillomía, M.A.; Artigas, J.I.; Falcó, J.L. Time Orientation Training in AAL, (book) Ambient Intelligence –Software and Applications. In Proceedings of the 9th International Symposium on Ambient Intelligence, Ávila, Spain, 26–28 June 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| School | No. of Children | No. Classes | No. of Teachers and Collaborators |

|---|---|---|---|

| CPEE Alborada | 6 | 6 Classes 1 Direction room | 6 Teachers 3 Direction staff |

| San Martín de Porres (ATADES) | 4 | 2 Classes | 2 Teachers Director |

| CPEE Piaget | 5 | 3 Classes | 3 Teachers Studies coordinator |

| CPEE Rivière | 1 | 1 Class 1 Staff room | 1 Teacher Director |

| Total | 16 | Classes 12 Rooms 2 TODs 14 | Teachers 12 Other staff 6 |

| No. | Age |

|---|---|

| 1 | 19 |

| 9 | 12 to 15 |

| 6 | 7 to 11 |

| No. | % of Disability |

|---|---|

| 3 | mild disability from 25 to 49 % |

| 12 | severe disability from 50 to 95 % |

| 1 | not provided |

| No. of Children | Curricular Competence Level |

|---|---|

| 7 | 1st phase of child education (corresponding to 2 to 3 years old in normalized schools) |

| 6 | 2nd phase of child education (corresponding to 4 to 5 years old in normalized schools) |

| 3 | With no registered information |

| Label | Level of Difficulty | Difficulty Range in % | Difficulty Mean Value (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | no difficulty | 0% | 0% |

| 1 | light difficulty | 5 to 24% | 14.5% |

| 2 | moderate difficulty | 25 to 49% | 37% |

| 3 | large difficulty | 50 to 95% | 72.5% |

| 4 | total difficulty | 96 to 100% | 98% |

| Code 010201 1st Assessment | No. of Items |

|---|---|

| No difficulty | 0 |

| light difficulty (5% a 24%) | 0 |

| moderate difficulty (25% a 49%) | 4 |

| large difficulty (50% a 95%) | 12 |

| total difficulty (96% a 100%) | 0 |

| ACTIVITIES WITH RESTRICTION | 16 |

| LEVEL OF RESTRICTION | 63,63% |

| Code 010201 2nd Assessment | No. of Items |

|---|---|

| no difficulty | 0 |

| light difficulty (5% a 24%) | 2 |

| moderate difficulty (25% a 49%) | 7 |

| large difficulty (50% a 95%) | 7 |

| total difficulty (96% a 100%) | 0 |

| ACTIVITIES WITH RESTRICTION | 16 |

| LEVEL OF RESTRICTION | 49.72% |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guillomía, M.A.; Falcó, J.L.; Artigas, J.I.; García-Camino, M. Time Orientation Technologies in Special Education. Sensors 2019, 19, 2571. https://doi.org/10.3390/s19112571

Guillomía MA, Falcó JL, Artigas JI, García-Camino M. Time Orientation Technologies in Special Education. Sensors. 2019; 19(11):2571. https://doi.org/10.3390/s19112571

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuillomía, Miguel Angel, Jorge Luis Falcó, José Ignacio Artigas, and Mercedes García-Camino. 2019. "Time Orientation Technologies in Special Education" Sensors 19, no. 11: 2571. https://doi.org/10.3390/s19112571

APA StyleGuillomía, M. A., Falcó, J. L., Artigas, J. I., & García-Camino, M. (2019). Time Orientation Technologies in Special Education. Sensors, 19(11), 2571. https://doi.org/10.3390/s19112571