Abstract

In forest ecosystems, fungal mats are functionally important in nutrient and water uptake in litter and wood decomposition processes, in carbon resource allocation, soil weathering and in cycling of soil resources. Fungal mats can occur abundantly in forests and are widely distributed globally. We sampled ponderosa pine/white fir and mountain hemlock/noble fir communities at Crater Lake National Park for mat-forming soil fungi. Fungus collections were identified by DNA sequencing. Thirty-eight mat-forming genotypes were identified; members of the five most common genera (Gautieria, Lepiota, Piloderma, Ramaria, and Rhizopogon) comprised 67% of all collections. The mycorrhizal genera Alpova and Lactarius are newly identified as ectomycorrhizal mat-forming taxa, as are the saprotrophic genera Flavoscypha, Gastropila, Lepiota and Xenasmatella. Twelve typical mat forms are illustrated, representing both ectomycorrhizal and saprotrophic fungi that were found. Abundance of fungal mats was correlated with higher soil carbon to nitrogen ratios, fine woody debris and needle litter mass in both forest ecotypes. Definitions of fungal mats are discussed, along with some of the challenges in defining what comprises a fungal “mat”.

1. Introduction

The importance of ectomycorrhizal (EcM) and saprotrophic fungi in forest ecosystems is well established [1,2]. Mycorrhizal fungi and their tree hosts form symbiotic relationships that are critical to obtain the nutrients needed for growth, and the role of saprotrophic fungi in biomass decomposition and nutrient cycling also is a vital ecosystem function [3,4]. Most fungal biomass exists as hyphae that permeate the soil, and although these are often too fine to see, they sometimes form rhizomorphs or aggregations of mycelial strands visible to the naked eye. Some taxa create discrete zones in the soil, where they appear to dominate soil biota, forming structures referred to as “fungal mats” [5]. The development of dense hyphal colonization and fungal rhizomorph networks facilitates utilization of heterogeneous soil resources and translocation of solutes [3,4].

EcM and fungal mats occur in all major forested regions, including tropical woodlands, and are critical to a variety of forest ecosystem functions [6,7,8,9,10,11]. The evolutionary development of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi over the past 460 My [12] and EcM within the last 220 My to150 My [13] has probably changed belowground nutrient cycling rates, particularly for soil C, N, and P and associated EcM enzymes [14,15], with the continued evolution of interactions between decomposer biota, mycorrhizae [15,16,17,18], and soil food webs [11,19,20]. This work has contributed to a better understanding of C allocation to EcM and fine roots [20,21], and to better insight concerning the nature and properties of soil organic matter (SOM) during its formation and turnover in soils [22,23,24].

Our aim was to sample mat-forming fungi (hereafter referred to as “mat fungi”) at Crater Lake National Park in the Cascade Mountains of southern Oregon, USA. We collected mat fungi and identified them by DNA sequencing. We also collected soil chemistry and surface fuels data (litter, woody debris) and to test the hypotheses that correlations exist between these habitat variables and the abundance of mat fungi, and when possible, to identify habitat preferences for specific taxa.

The definition of a “fungal mat” has differed among researchers over the years. Must a mat be mycorrhizal? Must it be perennial, or extend into mineral soil? Must it be hydrophobic? Must it be visible to the naked eye? Does size matter? A wide variety of definitions and descriptions have been given over the years. Classical early work on mat-forming fungi by Vittadini [25] described Gautieria morchelliformis as “veins converging on a rooting trunk originating at the base and arising from cottony filaments. Formed singly in an enormous, rooting mass of white-branny fibrils mixed in with rotting foliage”. Vittadini [26] also described Hysterangium as forming among “numerous loose fibrils, similar to G. morchellaeformis and the crust of Elaphomyces, widely meandering in the humus.” Tulasne and Tulasne [27] referred to Hysterangium as being embedded in “copious mycelia” which adheres to the fruiting bodies, and Gautieria as “borne in a copious, floccose mycelium broadly diffused in the soil”. Hesse [28] described Hysterangium as having “Mycelium strongly floccose, always snow white, of long, thin, branched, usually much interwoven hyphae that are frequently septate, with innumerable clamp connections and strongly thickened walls bedecked with many calcium oxalate crystals. They are always within the humus layer of forest soil and in nearly all cases extended over a broad stretch. The young oak and beech roots (less often also chestnut and hazel) are thickly entwined in them”. Ramsbottom [29] noted “irregular masses of soil held together by mycelial threads” under Lepiota and “compact masses of mycelium” under Collybia, and Hawker [30] described Hysterangium species forming a “mass of flocculent pure white mycelium, which aggregates to form rhizomorphs which bear the fruit-bodies.” Meyer [31] referred to “hyphenfladen” (hyphal cakes) under Laccaria amythestina. Fisher [32] described fungal mats as “up to 1 m in diameter…white, felt-like and 1–2 cm thick”. Cromack et al. [19] used the following definition: “a sufficiently dense colonization of litter or soil horizons to create characteristic fungal-mat zones which are readily visible”.

Griffiths et al. [33] observed “…extensive mats within forest soils and litter layers that are characterized by a dense profusion of rhizomorphs…form(ing) distinct morphological entities that are easily differentiated from adjacent noncolonized soil”. Unestam and Sun [34] defined a fungal mat as “…a limited and rather homogenous mycelium of densely interwoven rhizomorphs, strands of hyphae, all belonging to the same species, perhaps the same clone… and apparently excluding most other mycorrhizal fungi…(having) a visible border with the surrounding soil, be it mycorrhizal or not”. Nouhra et al. [35] described “a compact hydrophobic aggregation of fungal strands, mycorrhizal roots, and substrate” under Ramaria, and Agerer [36] described the mat subtype of mycorrhizae as a morphology that “…occupies rather large areas in the soil, where EcM with their emanating hyphae and rhizomorphs are so densely aggregated that there is apparently no space for other EcM species”. Griffiths et al. [37] mapped visual EcM mat distributions in a Pacific Northwest coniferous forests, reporting sizes from ~0.07 to ~0.16 m2, and occupying 10 to 20% of the forest floor. Dunham et al. [38] defined mats for the purpose of their research as “…dense profusions of rhizomorphs associated with obvious EcM root tips that aggregate soil and alter its appearance and were uniform in appearance for at least 0.5 m in diameter,” and Kluber et al. [39] sampled “…areas of densely aggregated fungal hyphae or rhizomorphs that covered an area with a minimum diameter of 20 cm”.

For many years, research on mat fungi in the Pacific Northwestern United States focused on Gautieria monticola and Hysterangium spp., and a substantial body of literature exists on the properties of these fungi. Cromack et al. [5] documented lower pH and higher levels of oxalic acid in mat tissue of H. setchellii (cited as H. crassum) and made the connection between fungal mats and accelerated mineral weathering as a source of primary mineral nutrition. Griffiths et al. [33] reported higher acetylene reduction and lower denitrification rates in H. setchellii mat soils, and consequently, concentrations of mineralizable N were reduced. Hysterangium setchellii mats and mat soils also concentrated N, P, and Ca [40] and increased soil C and C:N ratios [41], soil solution concentrations of Al, DOC, Fe, H, Mn, PO4, SO4, and Zn [42], and weathering of soil minerals [5,13,43,44,45].

Unestam [46] measured increased hydrophobicity in G. monticola, H. setchellii, and Rhizopogon spp.mat soils as compared to non-mat soils, and Entry et al. [40] hypothesized a connection between reduced leaching and increased nutrient concentrations in H. setchellii mats. This nutrient-rich microhabitat provides an environment conducive to the increased seedling regeneration rates in G. monticola and H. setchellii mat soils observed by Griffiths et al. [47]. Additionally, mycorrhizae function as a conduit of photosynthates from overstory trees to seedlings and to understory plants [48]. EcM decomposition of 14C labeled hemicellulose and cellulose was first reported by Durall et al. [49]. Increased lignin and cellulose decomposition rates measured by Entry et al. [50] in H. setchellii mats may accelerate nutrient turnover. This may be a function of the increased cellulase, laminarinase, peroxidase, and phosphatase activities observed by Griffiths and Caldwell [51] for H. setchellii and G. monticola mats, and for increased fatty acid esterase activities [52] found in pure cultures. Greater microbial biomass [53] and microarthropod [19] activities in H. setchellii mats further contribute to accelerated nutrient turnover, while also promoting increased soil respiration rates in fungal mats [33,54]. Other fungal genera reported as having mat-forming species include Arcangeliella [52], Austrogautieria [52], Bankera [55], Boletopsis [56], Chondrogaster [52], Cortinarius [57], Geastrum [58], Gomphus [59], Hebeloma [60], Hydnellum [61], Mycoamaranthus [52], Phellodon [62], Piloderma [63], Ramaria [64], Rhizopogon [34], Russula [39], Sarcodon [65], Sistotrema [38], Suillus [34], Trechispora [38] and Tricholoma [66].

2. Methods

2.1. Study Area

Crater Lake National Park is in the Cascade Mountains of southern Oregon. At elevations up to ca 1,600 m, a ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa)/white fir (Abies concolor) (PP/WF) ecotype is dominant (mixed conifer–Abies concolor zone sensu Franklin and Dyrness [67]), and at higher elevations, a mountain hemlock (Tsuga mertensiana /noble fir (Abies procera) (MH/NF) ecotype is dominant (Abies lasiocarpa and Tsuga mertensiana zones sensu Franklin and Dyrness [67]). Lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta var. latifolia) occurs throughout the park. Soil parent material is highly porous pyroclastic tephra dominated by volcanic pumice mixed with basaltic cobble and was deposited in the Mazama eruption ca 7,000 y ago. Mats were studied in the (PP/WF) ecotype in a prescribed burn experiment and in the (MH/NF) sites variously representing no disturbance vs. recreational use and wildfire.

2.2. Ponderosa Pine/White Fir Sites

In a PP/WF ecotype, 24 prescribed burn units of ca 2.8 ha were established by Perrakis and Agee [68] and detailed with habitat variable measurements in Trappe et al. [69]. Eight of these were nonburned controls, 8 had prescribed burns applied in spring 2002, and 8 had prescribed burns applied in autumn 2002. These units were at the south border of Crater Lake National Park in southern Oregon (lat 42°48′ N, long 122°50′ W) where fire history and plant communities were characterized by McNeil and Zobel [70]. Elevation varied from 1460 to 1550 m. Annual precipitation ranged about 65–85 cm y−1, most falling between October and May. The litter (O horizon) of ponderosa pine and white fir needles is up to 20 cm thick and ranges in dry mass from about 3 to 6 kg m−2. The humus layer (A horizon) varies considerably in thickness and has diffuse interfaces with the litter above and mineral soil below.

The overstory is dominated by ponderosa pine with subdominant white fir, with a midstory of white fir and lodgepole pine. Fire scar analysis by McNeil and Zobel [70] indicated that fires affecting substantial portions of the study area occurred in 1782–1784, 1791, 1818, 1846, 1864, 1879, and 1902. In 1902, the area was included in the newly designated Crater Lake National Park, and fires were suppressed from then through 1978. Prior to 1902, the overall fire return interval ranged from 12.8 to 40 y, with a mean of 21.1 y.

2.3. Mountain Hemlock/Noble Fir Sites

Eight sites in MH/NF communities were undisturbed controls, 4 were recreational sites in current use, 3 were abandoned recreational sites, and 3 were wildfire sites that burned in 1976, 1996, and 2001, respectively. The sites all were in the southern half of Crater Lake National Park except one wildfire site (Border Fire) at the northwest corner of the park; physical characteristics and habitat variables are detailed in Trappe et al. [71]. Mountain hemlock/noble fir communities have a highly variable fire return interval (15–157 y), with the majority of fires being low severity underburns [72]. Stand replacing fires do occur, and all 3 wildfire sites we sampled had experienced almost total mortality from the most recent fires.

The undisturbed control units were dominated by large, widely spaced overstory trees over 300 y old. Litter layers were deep (to 20 cm) and woody debris abundant. At the (disturbed) recreational units, overstory ages ranged from 167 to <300 y old with increased levels of lodgepole pine in the understory [73]. These sites have been in constant use since the 1870s (Picnic Hill), 1955 (Mason’s Camp), and ca 1960 (Mazama Village mid-seral and Mazama Village late-seral) [74]. Regular use of the abandoned recreational units ended in the 1950s (Annie Springs), 1972 (Cold Springs), and 1980 (Anderson Bluffs). Compared to the control units, both active and abandoned recreational units had reduced levels of woody debris and needle litter, and increased soil compaction

The three wildfire sites formed a short chronosequence: The Goodbye Fire burned in 1976, the Flying Dutchman fire burned in 1996, and the Border Fire burned in 2001. The Goodbye Fire site had scattered conifer regeneration 3 to 4 m tall, with a dense understory of Arctostaphylos spp, Ceanothus velutinus, and Ribes spp. The Flying Dutchman fire had isolated patches of regenerating conifers to 1 m in height, a sparse understory of Lupinus spp, and almost no litter layer. The Border Fire site had no regeneration or understory plants, and a very sparse litter layer with only a few small surviving trees (mostly <3 m tall). All wildfire sites had substantial coarse woody debris (CWD).

2.4. Soil Cores and Mineral Soil Bulk Density

Six 335 cm3 soil cores were taken with a hammer-type corer from random locations (by tossing a marker) throughout each treatment unit, labeled, and refrigerated in sealed plastic bags. Before coring, the litter and humus layers were removed from the surface of the mineral soil. Cores were dried in an oven at 60 degrees C for 12 h. The weight was divided by the core volume to determine bulk density.

2.5. Fungal Mat Sampling

We collected and sequenced hyphae or rhizomorphs sufficiently dense to aggregate their substrate to a depth of at least 2 cm, and usually at least 0.5 m2 in area. However, a number of mats (such as those of the Piloderma morphotype) were rarely that large, so samples were collected from some mats as small as ~10 cm in diameter. We did not attempt to distinguish between mycorrhizal and saprotrophic taxa in the field.

Each of the 42 units was sampled for one person-hour in July 2005, and again in September 2006. Mat abundance was measured by how many mats were located at each unit within the allotted time, irrespective of whether subsequent identification was successful. The litter surface was gently raked back to the upper layers of the A horizon. When fungal mats were observed, a tissue sample was collected and notes were taken on the appearance of fungi in situ. Sampling focused on microhabitats within each unit likely to support abundant mat fungi, such as low areas, underneath fungal sporocarps, around animal digs, and adjacent to decayed logs.

2.6. Fungal Mat Identification

Samples were stored at −20 degrees C until ready for processing. Prior to DNA analysis, each sample was rinsed with dH20, and a small subsample of fungal tissue was carefully removed by use of tweezers and a stereo microscope. DNA was extracted from the samples following Gardes and Bruns [75], and the ITS region of the nrDNA was amplified by PCR. In some cases the entire ITS region would not amplify; for these, the ITS-2 region was amplified. Samples were sequenced and identified with the Blast search tool on GenBank; those that did not provide a match with at least 95% similarity were discarded from the dataset. A Blast search provides a list of taxa most closely matching the search sequence, but often several taxa within a genus are too similar to distinguish with confidence. Thus, names were assigned at the genus level, with probable species or species group identities suggested. For ease of reading, in the Discussion section we use the species names with the caveat that specific identifications are tentative [76].

2.7. Carbon, Nitrogen, Stable Isotope Analysis, and Soil Ph Determinations

The screened soil core samples were ground to a sand consistency and homogenized, then ca 10 g subsamples were homogenized further and ground to flour consistency in an analytical mill. This finely ground soil was subsampled further (50–70 mg), into 8 × 5 mm tin cups and sent to UC Davis Stable Isotope Facility for total C content, total N content, and δ13C/15N isotopic analysis, relative to international standards [77], using a Europa ANCA-GSL elemental analyzer interfaced to a PDZ 20-20 isotope ratio mass spectrometer (Sercon Ltd., Cheshire, United Kingdom). The pH of mineral soil samples was measured potentiometrically in 1 g soil:5 ml deionized water.

2.8. Fuels: Litter Mass, Fine and Coarse Woody Debris

In each unit, ten, 20 m long, fuel inventory transects were established for a total of 200 linear m. Woody debris was measured as fine (FWD, 0.6–7.6 cm diameter) and coarse (CWD, >7.6 cm diameter), using Brown’s planar intersect method [78]. Litter depth measurements were taken at three points along each transect. Woody debris mass was calculated from the values for Pacific Northwest mixed-conifer forests derived by van Wagtendonk et al. [79], and litter mass was calculated from 10–14 samples of litter depth and density at each unit [68,73].

2.9. Data Analysis

All statistical analyses were done with Sas 9.1 [80]. Correlations between the total numbers of mat fungi (including those not identifiable) collected on each unit and the habitat attributes of the units were analyzed with linear regression. The habitat preferences of mat fungi collected on at least 3 units within an ecotype were analyzed with logistic regression, e.g., the presence or absence of a taxon is explored as a function of habitat attributes. Fungal mat associations with stand age were analyzed by chi-square test.

3. Results

DNA was successfully amplified and sequenced from 169 mycelia collections, representing 38 taxonomic units (Table 1 and Table 2). Members of the 5 most common genera (Gautieria, Lepiota, Piloderma, Ramaria, and Rhizopogon) comprised 67% of all collections; 10 taxa were collected only once. Three distinct genotypes of the EcM genus Piloderma and 3 distinct genotypes of the saprotrophic Ramaria stricta species complex were detected.

Table 1.

Number of mats located and identified by DNA analysis, by treatment. PP = ponderosa pine habitat; MH = mountain hemlock habitat; CG = campground.

| Habitat Type | Treatment | # Plots | # Mats total | Mats per treatment | # Mats identified | # Mat species |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PP | Control | 8 | 67 | 8.4 | 50 | 21 |

| PP | Spring Burn | 8 | 74 | 9.3 | 54 | 19 |

| PP | Fall Burn | 8 | 9 | 1.1 | 5 | 4 |

| MH | Control | 8 | 53 | 6.6 | 44 | 16 |

| MH | Active CG | 4 | 10 | 2.5 | 9 | 9 |

| MH | Abandoned CG | 3 | 8 | 2.7 | 6 | 4 |

| MH | Wildfire | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Table 2.

Mat fungi from Crater Lake National Park. PP = ponderosa pine habitat, MH = mountain hemlock habitat. Trophic level: M = mycorrhizal, S = saprotrophic.

| Habitat | Number collected | Species | Trophic level | Matching GenBank accession | % match |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PP | 2 | Alpova sp. (trappei) | M | AF074920 | 99–100 |

| PP | 1 | Cortinarius sp. #1 (caperatus) | M | AY669575 | 100 |

| MH | 1 | Cortinarius sp. #2 (pinguis) | M | DQ517414 | 95 |

| MH | 2 | Cortinarius sp. #3 (boulderensis) | M | DQ499466 | 95–97 |

| PP | 1 | Cortinarius sp. #4 (brunneus/gentilis) | M | AF430287 AF325589 | 95–96 |

| MH | 1 | Cortinarius sp. #5 (montanus) | M | AF478578 | 96 |

| MH/PP | 2 | Cortinarius sp. #6 (rigidus) | M | AY669658 | 95–97 |

| MH | 2 | Cortinarius sp. #7 (subfoetidus) | M | AF325609 | 96–97 |

| MH | 6 | Flavoscypha sp. (cantharella) | S | AF072082 | 95–98 |

| MH/PP | 5 | Gastropila sp.(subcretacea) | S | DQ112598 | 96–99 |

| MH/PP | 8 | Gautieria sp. (monticola) | M | AF377105 | 95–99 |

| MH/PP | 7 | Hydnellum sp. (peckii) | M | AY569030 | 95–98 |

| MH/PP | 2 | Lactarius sp. (scrobiculatus) | M | EF530942 | 96–98 |

| MH/PP | 7 | Lepiota sp. (magnispora) | S | AF391023 | 96–100 |

| PP | 2 | Piloderma sp. #1 ( byssinum) | M | DQ365683 | 95–96 |

| MH/PP | 45 | Piloderma sp. #2 ( fallax) | M | DQ371931 | 95–97 |

| MH/PP | 5 | Piloderma sp. #3 | M | EF218793 | 95–98 |

| PP | 2 | Ramaria sp. #1 ( flavobrunnescens var. aromatica) | M | AY102864 | 95–97 |

| PP | 2 | Ramaria sp. #2 ( rasilispora) | M | DQ365602 | 95–96 |

| MH/PP | 8 | Ramaria sp. #3 ( stricta) | S | DQ367910 | 95–99 |

| MH/PP | 8 | Ramaria sp. #4 ( stricta OSC65995) | S | DQ365600 | 95–97 |

| MH/PP | 10 | Ramaria sp. #5 ( stricta/pinicola) | S | DQ367910 DQ365649 | 95–97 |

| PP | 2 | Rhizopogon sp. #1 ( rubescens/roseolus) | M | AJ810045 AJ810043 | 98–99 |

| MH/PP | 8 | Rhizopogon sp. #2 ( salebrosus/subbadius) | M | DQ822822 AF377152 | 95–98 |

| PP | 1 | Rhizopogon sp. #3 (subpurpurascens/milleri) | M | AF377132 AF377135 | 95–96 |

| MH | 2 | Rhizopogon truncatus | M | By RFLP | |

| PP | 4 | Rhizopogon sp. #4 (vulgaris) | M | AF062931 | 95–97 |

| MH | 1 | Sistotrema sp. (albopallescens) | M | AM259210 | 98 |

| PP | 1 | Suillus sp. (tomentosus) | M | STU74614 | 98 |

| MH | 2 | Trechispora sp. #1 ( alnicola) | M | DQ411529 | 95–96 |

| MH/PP | 2 | Trechispora sp. #2 (subsphaerospora) | M | AF347080 | 95–97 |

| PP | 1 | Tricholoma sp. #1 ( equestre) | M | AF458454 | 95 |

| PP | 1 | Tricholoma sp. #2 ( intermedium) | M | AF377202 | 96 |

| PP | 3 | Tricholoma sp. #3 ( magnivelare) | M | AF527370 | 96–99 |

| PP | 5 | Tricholoma sp. #4 ( saponaceum) | M | DQ370440 | 95–97 |

| PP | 1 | Tricholoma sp. #5 ( sejunctum) | M | AB036899 | 96 |

| PP | 2 | Tyromyces sp. (chioneus) | S | AJ006676 | 95–97 |

| MH | 4 | Xenasmatella sp.(vaga) | S | AY805620 | 95–98 |

3.1. Habitat Associations in the Ponderosa Pine/White Fir Ecotype

The number of mats collected and identified by treatment is summarized in Table 1. Linear regressions indicated that the total abundance of mat-forming taxa in the PP/WF ecotype was positively correlated with soil C:N ratios, FWD mass, and needle litter mass, and negatively correlated with soil pH (Table 3). Significant interactions were detected between most of the significant variables; those between soil C:N and FWD mass, and between soil C:N and litter mass had the highest adjusted R2 values. These attributes were largely intercorrelated and showed a significant response to burn treatment [69]. The overstory in the ponderosa pine ecotype was of uniform age, so stand age was not included in data analysis. Ten taxa were collected on at least 3 units in the PP/WF ecotype; their logistic regression correlations with habitat attributes are displayed in Table 4.

Table 3.

Linear regressions between habitat variables and abundance of mat-forming taxa, by habitat type. Only values significant at α <0.1 are displayed. A negative sign indicates a negative correlation. PP = ponderosa pine habitat, MH = mountain hemlock habitat, CWD = coarse woody debris, FWD = fine woody debris.

| Habitat variable | PP habitat | MH habitat | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P value | adj. R2 | P value | adj. R2 | |

| Soil pH | −0.0173 | 0.1967 | ||

| C:N ratio | 0.0308 | 0.1582 | 0.0037 | 0.3815 |

| Litter mass | 0.0223 | 0.1798 | 0.002 | 0.5775 |

| FWD mass | 0.0129 | 0.2157 | 0.0424 | 0.1852 |

| Stand age | 0.0236 | 0.2363 | ||

| Interactions | ||||

| C:N × Litter | 0.004 | 0.2889 | 0.0001 | 0.646 |

| C:N × FWD | 0.0017 | 0.3383 | 0.0022 | 0.4189 |

| C:N × Stand age | 0.0021 | 0.4236 | ||

| Litter × Stand age | 0.001 | 0.6117 | ||

| FWD × Stand age | 0.0014 | 0.4498 | ||

| Litter × pH | 0.0318 | 0.1561 | ||

| FWD × pH | 0.0608 | 0.1121 | ||

| FWD × Litter | 0.0494 | 0.1263 | 0.001 | 0.4706 |

3.2. Habitat Associations in the Mountain Hemlock/Noble Fir Ecotype

The number of mats collected and identified by treatment is summarized in Table 1. All 3 collections from wildfire units came from the Goodbye Fire site (31 y post-fire). No mat fungi were observed at the other 2 wildfire sites (Flying Dutchman Fire sampled 11 y post-fire, and the Border Fire sampled 2 y post-fire), suggesting it may take 15 + y for mats to re-establish following wildfires.

As with PP/WF communities, linear regressions of total mat-forming taxon abundance in the mountain hemlock ecotype showed positive correlations with stand age, soil C:N ratios and the mass of FWD and needle litter (Table 3). Stand age was also significantly correlated with the abundance of mat fungi. Interactions were detected between all of the significant variables, with that between C:N ratio and litter mass having the highest adjusted R2 value.

Five mat-forming taxa were collected on at least 3 units; logistic regression correlations with habitat attributes are displayed in Table 4. No individual taxon correlated with stand age, but only 1 mat was detected in a stand less than 100 y old (Hydnellum peckii). Twenty-one of these 26 mats were collected in stands > 300 y old (χ2 = 0.004).

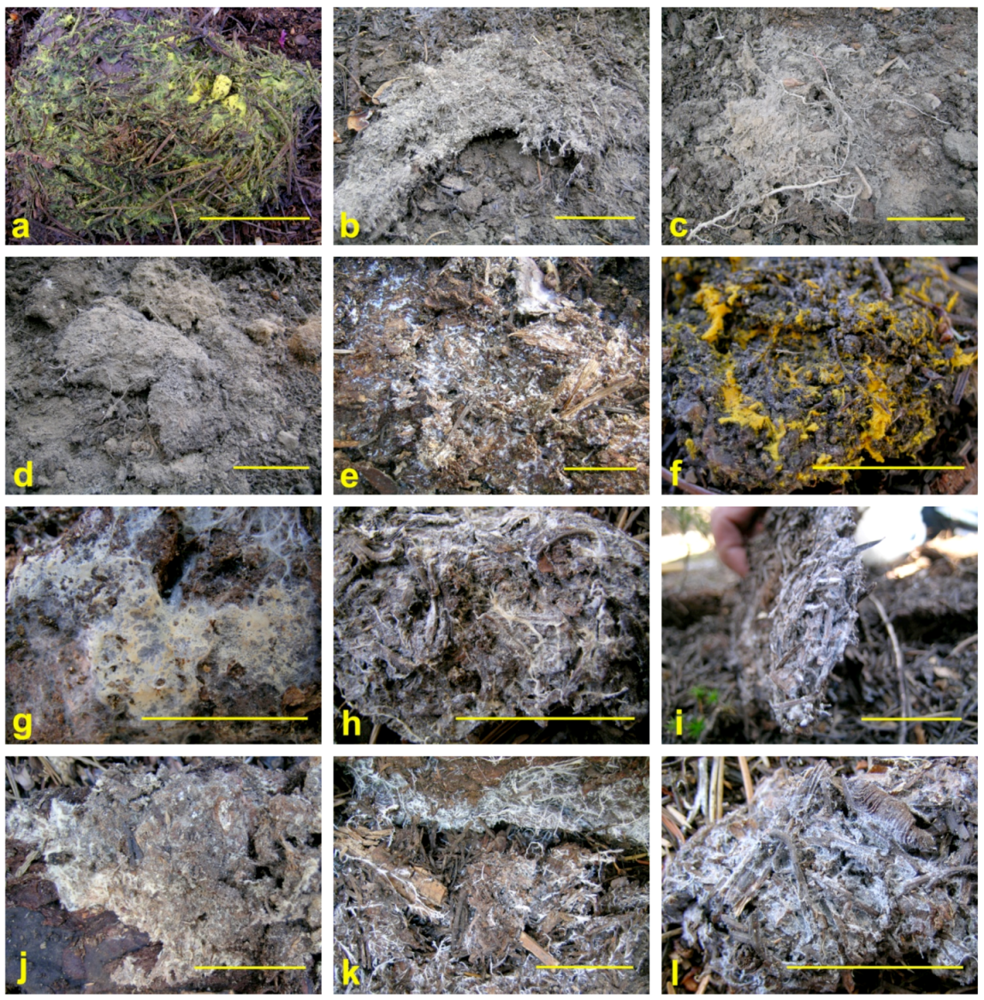

Representative fungal mats observed at Crater Lake are illustrated in Figure 1, with examples chosen from both EcM and saprotrophic fungal taxa. The EcM genera Alpova and Lactarius are newly identified as mat-forming taxa, and Flavoscypha is the first documented mat-forming Ascomycete. The genus Ramaria contains both EcM (subgenus Ramaria) and saprotrophic (subgenus Lentoramaria) mat-forming species (Table 2).

Table 4.

P values of logistic regression of habitat associations on those taxa collected at least 3 times within a habitat type. A negative sign indicates a negative correlation; values significant at α < 0.1 are bolded. PP = ponderosa pine habitat, MH = mountain hemlock habitat, CWD = coarse woody debris, FWD = fine woody debris.

| PP habitat | n | Bulk density(g cm−3) | Total Soil C (%) | Soil δ13C (‰) | Total Soil N (%) | Soil δ15N (‰) | C:N ratio | CWD (Mg ha−1) | FWD (Mg ha−1) | Litter mass (Mg ha−1) | Soil pH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gautieria monticola | 6 | −0.311 | 0.0731 | −0.410 | −0.677 | 0.155 | 0.056 | 0.118 | 0.104 | 0.128 | −0.124 |

| Lepiota magnispora | 4 | 0.776 | 0.348 | 0.201 | 0.13 | 0.986 | −0.705 | 0.227 | 0.067 | 0.094 | −0.462 |

| Piloderma fallax | 15 | −0.039 | 0.637 | −0.154 | −0.214 | −0.777 | 0.017 | 0.063 | 0.031 | 0.048 | −0.190 |

| Piloderma sp. | 4 | 0.63 | 0.178 | −0.161 | −0.353 | 0.314 | 0.088 | 0.117 | 0.645 | 0.305 | 0.710 |

| Ramaria stricta | 6 | −0.375 | 0.812 | −0.615 | −0.126 | 0.281 | 0.040 | 0.138 | 0.641 | 0.682 | −0.233 |

| Ramaria stricta/OSC65995 | 3 | 0.703 | 0.622 | 0.372 | 0.46 | 0.115 | 0.8541 | 0.381 | 0.732 | 0.678 | 0.188 |

| Ramaria stricta/pinicola | 6 | 0.138 | 0.453 | 0.539 | 0.603 | 0.651 | 0.299 | 0.559 | −0.905 | 0.497 | −0.233 |

| Rhizopogon salebrosus | 5 | −0.105 | 0.897 | 0.793 | −0.448 | 0.625 | 0.299 | −0.722 | 0.799 | 0.997 | −0.194 |

| Rhizopogon vulgaris | 4 | −0.159 | 0.099 | −0.274 | 0.419 | −0.999 | 0.495 | 0.145 | 0.223 | 0.148 | −0.122 |

| Tricholoma saponaceum | 5 | 0.966 | 0.532 | 0.936 | 0.592 | 0.256 | −0.403 | 0.383 | 0.439 | 0.208 | −0.243 |

| MH habitat | |||||||||||

| Flavoscypha cantharella | 6 | 0.505 | 0.599 | 0.542 | 0.591 | −0.973 | 0.642 | −0.486 | 0.520 | 0.096 | −0.317 |

| Gastropila subcretacea | 3 | 0.484 | −0.332 | −0.875 | −0.271 | −0.822 | 0.252 | −0.277 | −0.985 | 0.419 | 0.756 |

| Hydnellum peckii | 4 | 0.877 | −0.927 | −0.142 | −0.580 | 0.972 | 0.336 | 0.575 | 0.568 | 0.578 | 0.620 |

| Piloderma fallax | 15 | −0.124 | −0.149 | −0.693 | −0.115 | 0.136 | 0.052 | 0.052 | 0.099 | 0.042 | −0.226 |

| Ramaria stricta/OSC65995 | 5 | −0.586 | 0.561 | 0.142 | 0.540 | −0.651 | 0.693 | 0.872 | 0.660 | 0.233 | −0.317 |

| Rhizopogon truncatus | 3 | 0.156 | −0.517 | 0.275 | −0.386 | −0.585 | 0.701 | 0.637 | 0.806 | −0.559 | 0.385 |

4. Discussion

4.1. Mat Abundance and Taxonomy

Our data suggest that abundance of fungal mats is positively associated with surface litter depths and mineral soils with higher C:N ratios (Table 3). Prior work by Aguilera et al. [41] on fungal mats in Oregon had established the important effect of increasing soil C:N ratio by EcM mat fungi. As shown by Lindahl et al. [1] and further discussed by Hobbie and Horton [81], selective uptake and utilization of organic N from the mineral soil actively increases soil C:N ratios. In our study, the EcM species Piloderma fallax was significantly correlated with soil C:N ratio in the ponderosa pine habitat (Table 4), as were several Cortinarius species in the study by Lindahl et al. [1]. Our work and that of Aguilera et al. [41] suggest worthwhile opportunities for including additional mat-forming taxa in future research focused on cycling of C, N and other nutrients.

Only the 14 most commonly occurring species were collected in sufficient quantity analyze correlations with habitat variables. Additionally, habitat data were collected on a treatment unit scale and did not account for microhabitat. For example, while many collections were in units with compacted soils and relatively sparse needle litter, the vast majority of such collections were under the dripline of smaller trees or along slopes—microhabitats that retained a deeper litter layer and had less soil compaction. In burned sites, the same response was observed: mats were collected exclusively in areas where the fire had left patches of unburned litter. It was highly apparent that where needle litter was sparse due either to anthropogenic disturbance or fire, the likelihood of finding mats decreased substantially. This is probably due to the mulching effect of surface litter, maintaining higher soil moisture levels throughout the dry season [82].

Mat fungi often were observed directly below a sporocarp, and in only one case (Rhizopogon truncatus) was the fungal mat of the same taxon as the sporocarp (Figure 1a). Rhizopogon sporocarps were collected from the very heart of Gautieria mats, Rhizopogon mats were observed directly beneath Ramaria sporocarps, and Gautieria sporocarps were collected from Ramaria mats. Notably absent from Crater Lake collections were mats of Hysterangium species, although several sporocarps were collected. Often sporocarps of mat-forming taxa were collected with no associated visible mat, indicating that in some species the formation of a mat is not always linked to the presence of sporocarps, or that the mat structure is not perennial or consistently visible.

Mycorrhizal taxa forming “mat subtypes” of Agerer [83] fell into 2 morphological subcategories at Crater Lake: a powdery morphotype and a mycelial morphotype. The powdery morphotype was produced by Gautieria monticola (Figure 1b), Hydnellum peckii (Figure 1c), and Sistotremaalbopallescens (Figure 1d). Soil within these mats was discolored (usually gray), and root tips often were abundant. The mycelia frequently were too fine to detect with the unaided eye, but nevertheless, bound the substrate into a cohesive mass, often including mineral soil. The mats formed by these 3 taxa were indistinguishable from one another in the field.

The mycelial mat morphotype [83] was characterized by fine but visible mycelia that bound the substrate together, and sometimes produced clumpy wefts or small fans (Figure 1a,e,f–h). These mats were often at the interface between the A and O horizons and knit fine humus particles together into a solid mass. In many cases, mycorrhizal mats were identified from the less-decomposed upper litter layer (Figure 1a,e,i). Some, notably Piloderma spp, were closely associated with decayed CWD (Figure 1f,g). Long-range foraging structures (sensu Agerer [83]), such as rhizomorphs or mycelial cords, were uncommon in mycorrhizal mats.

Figure 1.

Fungal mat morphologies. (a) Rhizopogon truncatus; (b) Gautieria monticola; (c) Hydnellum peckii; (d) Sistotrema albopallescens; (e) Cortinarius brunneus; (f) Piloderma fallax; (g) Piloderma sp; (h) Rhizopogon salebrosus/subbadius; (i) Trechispora alnicola; (j) Xenasmatella vaga; (k) Ramaria stricta; (l) Gastropila subcretacea. Scale bars = 5 cm.

A number of saprotrophic taxa also formed fine mycelial mats indistinguishable from EcM mats (compare Figure 1e,j). Some saprotrophic mats were accompanied by profusions of mycelial fans and cords (Figure 1k,l), features largely absent from EcM mats. Most were associated with the litter layer and did not obviously extend into the mineral soil layer.

Morphology and color are less than satisfactory for identifying fungal mat species: Piloderma fallax mats ranged in appearance from knits of bright yellow mycelial cords and wefts to off-white hyphal sheets. The coarse white mycelial cord morphology was produced by many, but not all saprotrophic taxa, most commonly Lepiota magnispora, Ramaria stricta s.l., and Tyromyces chioneus.

Piloderma spp. were the most common mat fungi collected in this survey, consistent with the findings of Dunham et al. [38]. We identified 3 distinct genotypes of Piloderma at Crater Lake. The majority of Piloderma collections (45) matched P. fallax in GenBank. Two collections matched P. byssinum, and five matched a cryptic Piloderma sp.

4.2. Mat Functions in Forest Ecosystems

EcM fungal symbionts are important functional components in forest ecosystems, particularly in their role of taking up soil moisture and nutrients for use by a wide variety of shrubs and trees [2,6,8,13,84,85]. Saprotrophic fungi, some of which are mat-forming, are important in decomposition and nutrient cycling processes in forest ecosystems [86,87,88,89].

To provide an overview of forest ecosystem functions, we synthesized a comparative table (Table 5) from a variety of previous studies detailing a substantial range of work by using representative fungal mat genera with species occurring at Crater Lake or closely related to those found there (Table 2). The ecosystem functions detailed in this table (Table 5) include translocation of nutrients [48,90] and water [91,92]; litter and soil organic matter decomposition [1,15,93,94,95]; mineral soil and rock weathering [5,40,42,43,44,45,86,96], soil enzyme production [39,97], seedling regeneration [46]. Many of these fungi also provide food sources for soil invertebrate [19,20] and vertebrate [11] fauna.

Recent work has highlighted the critical roles of hyphal, mycelial strand, and rhizomorphic EcM networks [13,88,98,99,100]. Furthermore, continued progress with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal (AMF) research has shown that these organisms also form extensive interconnected networks among plant species [12]. It seems likely that AMF formed some of the earliest fungal networks, while facilitating colonization by early land plants [12]. The continued evolutionary development of fungi and their more complex morphological features led to basidiomycetes, which could decompose complex C substrates in forest litter and in wood components [14,101], including roots, and to symbiotic EcM fungi, including a variety of species which can form fungal mats in the forest floor and/or mineral soil. Mat-forming fungi occur in a variety of basidiomycetes, including saprotrophic fungi, as well as EcM. Representative examples of mat formers that are found at Crater Lake are shown in Figure 1.

Carbon transfer to EcM fungi and their networks can be a substantial fraction of belowground C allocation [20,102]. Species of Cortinarius, such as C. montanus, which can form fungal mats (Table 5), are of interest in studies of C allocation and also in work on N uptake [20,94,95]. Different EcM fungal mycelial exploration types, such as those from Hydnellum peckii and H. ferrugineum, can have different 13C and 15N isotope values, depending upon their ability to access organic C and N resources from the deeper forest floor layers and from mineral soil [1,15,84,94,95]. EcM fungi may dominate N-recycling in more N-limited forest ecosystems, including the pristine environment at Crater Lake. In contrast, in highly N-deposition polluted environments in parts of Europe, hydnoid EcM species such as H. ferrugineum and H. peckii are threatened [103,104] and would be ideal for future study in both pristine environments, such as those for H. peckii at Crater Lake, and in N-polluted forest environments [105], where integrated forest management strategies for fungal species conservation may be applied [69,71,104]. In addition, EcM fungi are critically important in forest ecosystem recovery from N-saturated soil conditions [106].

Biogeochemical functions of EcM include weathering release and accumulation of essential nutrients such as P, Ca, and Mg, and also of micronutrients from both the mineral soil and from rock weathering [5,40,42,43,44,45,85,96]. EcM species of mat-forming fungi studied by these researchers were Gautieria monticola, Hysterangium setchellii, Piloderma byssum and P. fallax. These types of mat-forming EcM species or other closely related species occur at Crater Lake (Table 5).

Soil enzyme research on fungal mats is represented by recent studies on mat-forming Piloderma sp. (Table 5) for N, P and C recycling functions such as chitinase [39,97]. Earlier mat research showed increased phosphatase, cellulase, and peroxidase [51] for the fungal mat-forming species Hysterangium setchellii and Gautieria monticola relative to adjacent non-mat soil areas. A similar increase in soil respiration activity between EcM mats and adjacent non-mat areas was demonstrated under field conditions [54,61].

In addition to essential nutrient uptake, the uptake of water, including the hydraulic redistribution of water, is an important forest ecosystem function for EcM [91,92]. The EcM species, Rhizopogon salebrosus, which occurs at Crater Lake (Table 5), has been used for hydraulic redistribution research [96]. Certain EcM have hydrophobic mycelia [34,46,95], which may facilitate biogeochemical functions as they colonize organic and inorganic soil substrates.

Consumption of EcM sporocarps by animals as food resources (Table 5) has been of considerable interest [11,107]. Innovative field studies using 13C as a tracer for C allocation to Cortinarius sp. has demonstrated 13C uptake by soil animals such as collembola from fungal hyphal consumption [20]. Invertebrate fauna such as mites, collembola, nematodes and protozoans, can have increased populations within fungal mats of G. monticola and H. setchellii relative to adjacent non-mat soil areas [19].

Mat-forming EcM species also can facilitate inter-tree connectivity. Griffiths et al. [46] found most Douglas-fir seedlings in a mature forest were in H. setchellii and G. monticola mats (Table 5), possibly promoting successful seedling regeneration which requires sufficient EcM colonization for survival and growth [2,108]. Other research has further confirmed the linkage of trees and shrubs by one or more EcM species in forest ecosystems [90,99].

Decomposition studies of saprotrophic fungi have long been of interest [88]. The saprotrophic species Lepiota magnispora occurs at Olympic National Park [98] and forms fungal mats at Crater Lake National Park (Table 5). The white-rot fungus L. magnispora and other saprotrophic genera such as Clitocybe, Cudonia, Marasmius, Mycena, Psalliota, and Rhodocybe, can have discrete colonies in the forest floor of coniferous forest ecosystems [109].

Mycorrhizal mat networks provide multiple interconnections and pathways within fungal mats for mycorrhizal network functioning within both organic and mineral soil substrates, thus enhancing decomposition and mineral weathering, and the release of nutrient elements such as N, P and K through mycelial and hyphal penetration of soil substrates [1,34,43,44,45,110]. Fungal nutrient cycling pathway functions first were indicated by extensive sampling of fungal rhizomorph tissues in both temperate and tropical forests [86]. Subsequent work demonstrated C and N transfers within fungal networks [48,101]. Furthermore, there can be considerable interchange of nutrients, C resources, and water resources due to the presence of extensive mycorrhizal networks [13,90,91,99,101,111,112].

EcM mats can enhance soil organic matter (SOM) decomposition and release of nutrients (N, P, K, Ca, Mg) through increased mineral soil weathering [1,15,32,33,42,51,61,113]. These mat structures can persist for long periods, even decades [61]. Individual fungal rhizomorphs can persist for several months, surviving through a growing season in a pinyon–juniper woodland [98]. Fungal mats formed by Hydnellum ferrugineum, (Fr.) in a Finnish study by Hintikka and Näykki [61], and H. scleropodium, in a Canadian study by Fisher [32], measurably decreased the soil humus layer thickness and mineral soil organic C and N concentrations, indicating the presence of a complex microbial community able to decompose resistant C substrates and to release structurally bound organic N (Table 5). Interestingly, mat fungi such as H. ferrugineum and H. peckii once were widespread in Europe prior to increased pollution, and currently are threatened in some countries [103,104,114]. They may be sensitive to increased N deposition [103,105], such as the EcM fungi negatively impacted along a nitrogen-deposition gradient [105,115,116].

If fungal mats are mobilizing organic N resources (including chitin) in the soil, as indicated by recent research on N recycling [1,15,39,93,97], this would help to explain the classic EcM fungal mat observations concerning soil N mobilization [32,61], as well as current confirmation of organic N uptake by EcM together with supporting evidence from 13C and 15N isotopes [84,93,95]. Thus, the allocation of new C in fine roots and EcM mat-forming networks may enhance decomposition of resistant SOM, as evidenced by the substantial decreases in both SOM and N observed in the fungal mat studies by Hintikka and Näykki [61] and Fisher [32]. In addition, these types of EcM mats may improve the environmental conditions for enhanced SOM decomposition, through conversion of more stabilized SOM structure into a less stabilized structure, which becomes progressively more amphiphilic as a more optimal oxidative process proceeds [23]. A future study involving the chemical and structural effects of fungal mats on SOM could be used to test new hypotheses of SOM development and decomposition, as articulated by Kleber et al. [22], Kleber and Johnson [23] and Sollins et al. [117] in their new syntheses concerning SOM structure and its environmental interactions. New work on the formation and chemical structure of SOM by Schmidt et al. [24] should further stimulate experimental research with fungal mats. Dense mat colonization enhancing connectivity within the soil matrix, coupled with increased enzyme activities [39,97] and possible increased priming effects from EcM C allocation [15,20] may enhance SOM substrate decomposition rates, and the release of nutrients such as N, P and S. Increased fungal mat hydrophobicity [46] might decrease soil moisture and increase soil aeration to facilitate SOM decomposition.

Hydrophobicity has been documented in some mat types [35,46,53], while others have been described as “becoming wet seasonally” [53]. For the majority of mat-forming taxa, no data on hydrophobicity exist. Accordingly, it is premature to consider hydrophobicity an attribute common to all fungal mats or to consider it as a prerequisite for ‘mat’ status. Some litter and SOM substrates also are hydrophobic [23]. Thus, the hydrophobicity of some fungal mats [46] may facilitate improved aerobic conditions, surface contact, and permeation of these types of substrate by fungal hyphae and mycelial structures. In turn, this might promote a coordinated, progressive oxidation of litter and SOM by fungi and bacteria, together with improved conditions for soil animal colonization of fungal mat environments. Increased soil animal abundance, particularly microarthropods and protozoa, has been observed to occur in fungal mats [19].

Crater Lake National Park represents a pristine forest environment within which to study mat fungi. These fungi would be ideal for future research on EcM and saprotrophic fungal utilization of organic N sources, as indicated by previous EcM research [1,15,51,93]. Natural abundance stable isotope data from δ13C and δ15N has been helpful in interpreting EcM vs. saprotrophic trophic status from sporocarps collected in forest ecosystems [84,94,95,118,119]. However, mat-forming EcM basidiomycetes can have 13C isotope natural abundance values similar to those of saprotrophic fungi; e.g., H. ferrugineum and H. peckii [84], the latter occurs at Crater Lake NP (Figure 1c). The morphological colonization of fine roots of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) by H. ferrugineum, with normal EcM formation at the leading edge of the fungal mat and the atrophy and death of colonized roots at the trailing edge of the fungal mat [120], indicates a type of EcM formation that shows saprotrophic characteristics as the mat advances and leaves behind a zone of formerly colonized soil. The δ13C isotopic signature observed in H. ferrugineum by Taylor et al. [84] may be indicative of this fact. Similarly, the mat-forming Tricholoma magnivelare, which occurs at Crater Lake, has been observed to colonize conifer roots with subsequent loss of the outer root cortex, resulting in a carbonized form of EcM in these EcM mats [121,122] as discussed by Hobbie and Horton [81]. In 1993, this same effect on fine tree roots also was observed in a fungal mat colony of H. ferrugineum growing within the forest floor H layer and the upper 10 cm of the mineral soil in a mature Swedish Scots pine (P. sylvestris) forest [123].

Table 5.

Representative fungal species from Crater Lake National Park that have been used in studies of mat functions in forest ecosystems. Trophic level: M = mycorrhizal, S = saprotrophic.

| Fungal mat species | Trophic level | Ecosystem function | Tree species & location | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cortinarius montanus | M | Organic N uptake from litter humus substrates—13C and 15N isotopes | Western hemlock, Douglas-fir—Olympic National Park, Washington | [94] |

| Cortinarius sp. | M | Carbon transfer to mycorrhizal fungal network—13C labeling | Scots pine—Sweden | [20] |

| Gautieria monticola | M | Increased soil labile-C | Multi-aged Douglas-fir Oregon, USA | [41] |

| Hydnellum peckii | M | Nitrogen uptake from soil organic matter—13C & 15N isotope fractionation | Scots pine—Sweden | [84] |

| Hysterangium setchelliia | M | Calcium oxalate, biogeochemical cycles | Douglas-fir—Oregon, USA | [113] |

| M | Calcium oxalate, clay weathering | Douglas-fir—Oregon, USA | [5] | |

| M | Altered soil fauna | Douglas-fir—Oregon, USA | [19] | |

| M | Litter decomposition and nutrient release | [50] | ||

| M | Elevated soil biomass, altered soil chemistry (N, P, Ca, Mg) | Douglas-fir—Oregon, USA | [40] | |

| Hysterangium setchelliia | M | Calcium oxalate, biogeochemical cycles | Douglas-fir—Oregon, USA | [113] |

| M | Calcium oxalate, clay weathering | Douglas-fir—Oregon, USA | [5] | |

| M | Altered soil fauna | Douglas-fir—Oregon, USA | [19] | |

| M | Litter decomposition and nutrient release | [50] | ||

| M | Elevated soil biomass, altered soil chemistry (N, P, Ca, Mg) | Douglas-fir—Oregon, USA | [40] | |

| Gautiera monticola & Hysterangium setchelliia | M | Douglas-fir seedling regeneration | Douglas-fir—Oregon | [47] |

| M | Soil enzyme activities: cellulase, peroxidase, phosphatase, protease | Douglas-fir—Oregon, USA | [51] | |

| M | Altered soil solution chemistry: elevated C, N,P. S, oxalate, H+, Al, Ca, K, Mg, Fe, Mn, Cu, Zn | Douglas-fir—Oregon, USA | [42] | |

| Gautieria monticola, Hysterangium setchelliia, & Piloderma sp. | M | Soil enzyme activities: phosphatase, chitinase | Douglas-fir, western hemlock—Oregon, USA | [39,97] |

| Piloderma byssinum | M | Mineral weathering | Scots pine—Sweden | [43] |

| Piloderma fallax | M | Calcium oxalate biomineralization,? | Subalpine fir—Canada | [96] |

| Rhizopogon salebrosus | M | Hydraulic redistribution of water | Ponderosa pine –Metolius Research Natural Area, Oregon | [92] |

| Alpova trappei, Gautieria monticola, Rhizopogon salebrosus, Rhizopogon truncatus | M | Sporocarp consumption by small mammals | Douglas-fir, mountain hemlock, ponderosa pine—Oregon | [11] |

| Cortinarius sp. | M | Mycelial consumption by springtails in soil | Scots pine—Sweden | [20] |

| Lepiota clypeolariab | S | Litter decomposition, white-rot humus | Norway spruce—Finland | [109] |

| Lepiota magnispora | S | Soil humus layer—13C and 15N isotopes | Western hemlock, Norway spruce—Olympic National Park, Washington | [94] |

| Lepiota sp.b | S | Litter decomposition, white-rot humus—13C and 15N isotopes | Douglas-fir—Oregon | [118] |

a This Hysterangium species was not observed at Crater Lake, but H. separabile sporocarps were collected there [69,71]. The H. crassum species name used in Cromack et al [5] later was changed to H. setchellii; b These Lepiota species were not observed at Crater Lake, but are closely related to L. magnispora and are representative of white-rot humus colonizing fungi.

4.3. Definitions of Fungal Mats

The formation of the mat morphology by some fungi is thought to confer an evolutionary advantage due to the efficiency and effectiveness of site occupation by dense masses of tissue to concentrate enzymatic activity and exclude competitors. The definition of what precisely constitutes a mat probably will remain a matter of opinion, but most will agree that a mat is a dense aggregation of fungal hyphae that has a distinct edge or border, and has an element of depth rather than being superficial. This concurs with the classical description by Vittadini [25,26]. Further characterizations are subject to exceptions and continued development of quantification methods. For example, if a mat is defined as cohesively binding its substrate, what constitutes “cohesive?” Piloderma fallax (Figure 1f) is widely accepted as being mat-forming [63,124] but frequently binds its substrate only loosely and does not thoroughly permeate its environs any more than the saprotrophic Ramaria stricta (Figure 1k). Some mat fungi (such as EcM Piloderma fallax) are associated with CWD [124,125], although most discussions of fungal mats are restricted to those residing in the soil. There is, however, precedent for use of the term in reference to decomposition in stumps and standing snags by saprophytic fungi: Fomitopsis officianalis and F. pinicola in Arora [126], and Phellinus weirii in McDougall and Blanchette [127].

Some earlier researchers have restricted their collecting to EcM mats based on morphology and/or sporocarps [37], but in our experience it is difficult to distinguish EcM from saprotrophic mats in the field and sporocarp association may not always be definitive. Mycorrhizal root tips are not always easily detectable, and confident identification of the mat-forming fungus usually requires genetic typing. By the broad morphological definitions above, many saprotrophic taxa clearly form mats. Saprotrophic mats often have abundant mycelial cords (Figure 1k), but not always (Figure 1j,l).

One difference that might be expected in developmental patterns between mycorrhizal and saprotrophic mats is that saprobes may be restricted to surface organic material, while mycorrhizal fungi, with their carbon source secured, are more likely to extend into the B horizon foraging for mineral nutrients [128]. However, many mycorrhizal mats were visible only in the O and organic A horizons (Figure 1a,e,h,i) and were quite similar to saprotrophic mats in their substrate affinities (Figure 1j–l). Several mycorrhizal mat-forming taxa, such as Hysterangium [129] and Piloderma [38,124,125], are closely associated with CWD, and although their hyphae can extend into mineral soil [130], it is not always apparent [131]. Fungal mats of H. setchellii and G. monticola were observed growing within the upper mineral soil in a western Oregon Douglas-fir forest [33,40,42], with H. crassum (now H. setchellii) mats occupying an average mineral soil depth of 6.1 cm and an average mat area of 0.33 m2 [5].

Another criterion sometimes used is that a mat is monopolized by one fungal organism, or at least appears homogenous in its composition [34,36,38]. However, we frequently encountered situations where the sporocarp of one taxon was collected from the heart of a mat formed by a different one. Murata et al. [132] reported genetic mosaics within matsutake shiros, and multiple mycorrhizal root tip morphotypes have been isolated from a single Gautieria mat [133,134]. Clearly, hyphae of several origins can be in mats, whether or not visibly distinguishable. In earlier work, Hintikka [109] observed that EcM species, such as Piloderma bicolor (=P. fallax; [135]), could colonize white rot humus formed by Clitocybe clavipes. He also observed that recognizable mycelia of EcM, such as Cortinarius semisanguineus and Hebeloma sp. occurred more abundantly in the F-layers of Finnish conifer forests that were decolorized by white-rot fungi, such as Marasmius androsaceus. Hintikka’s work [109] suggests that studying interactions between saprotrophic fungal mats and EcM fungal mats could be worthwhile, given current developments in soil chemistry, soil enzymes, soil natural abundance of δ13C and δ15N stable isotopes, and in identification methods [13,39,97,119,126,136].

Mats often are assumed to be perennial and stationary, characteristics perhaps more apt for EcM than saprotrophic mats, although little research has followed individual mats for more than a few seasons. Such research is complicated by the fact that some mats, such as a Hysterangium mapped in the summer, are not visible in the winter in heavy rain except where sheltered under logs, but reappear in the spring in the same location. There is evidence that fungal mats may shift their position as localized resources are depleted [120,137,138], raising the intriguing notion that they may slowly migrate and forage through the soil.

Mat size also is difficult to quantify as hyphal assemblages are ubiquitous in forest soils [54,139], and undoubtedly, the largest mat started out as a few hyphae. For research purposes, some criteria must be established to distinguish between ‘mats’ and a few mycelial cords in proximity to each other. The criteria used necessarily are a function of the research question, and thus a rigid definition of mat size and area is impractical. EcM mycelia constitute a major allocation of C resources into the soil ecosystem [21], as indicated by increased mat respiration [33,61,140]. Recent research on EcM hyphal production in soil cores demonstrates that both mineral and soil organic matter composition can affect hyphal production [119,126,141].

A functional definition of EcM mats also is challenging to apply. In the most intensively studied mats (Gautieria and Hysterangium), many potentially distinguishing properties have been identified [41,50,53]. None of these properties can be measured easily in the field, [25,32,61] and it is largely unknown if other mat fungi share them. In the future, this type of research could benefit from an integrated set of measures for evaluating microbial communities within and adjacent to fungal mats; e.g., Kluber et al. [39,97] and in the overviews by Leckie [142] and Allen et al. [111], and by the greatly enhanced microbial community analysis from using next generation sequencing [13,136]. The importance of EcM mat functions may be better expressed when normalized to microbial biomass and respiratory activities which can exceed those in non-mat soils [33,140].

5. Conclusions

At Crater Lake National Park, we identified 36 EcM, mat-forming genotypes and 21 saprotrophic, mat-forming genotypes. Among the EcM genotypes, two genera had not been previously identified as mat-forming. The abundance of EcM mats highly correlated with litter mass, and areas without litter generally lacked mats. Fungal mats are sensitive to severe disturbance, and may take over 15 years to re-colonize after a wildfire event. The fungus forming a particular mat is extremely difficult to identify confidently in the field, and a universal definition of exactly what does and does not constitute a fungal mat remains elusive. Researchers have historically defined mats in the context of their particular study design, and necessarily will continue to do so. Future research must also include integrated measures of specific functions (e.g., exoenzyme activities) for evaluating microbial communities within and adjacent to fungal mats (e.g., Kluber et al. [39,97]) together with continued research on microbial diversity using emerging approaches and tools [15,111,142,143].

Acknowledgements

We thank the Joint Fire Science Program (PNW-04-CA-11261952-317) and the NSF Microbial Observatory (MCB-0348689) for funding this project, and Crater Lake National Park for permitting the research. Randy Molina, Doni McKay, and the USDA Forest Service PNW Research Station provided facilities. Dan Luoma and Jane Smith provided their thoughts on mat definitions. The OSU Center for Genome Research and Biocomputing performed DNA sequencing. Angeline Cromack and Kevin Cromack edited and formatted the paper. We are grateful for the helpful comments of three anonymous reviewers. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Supplementary Files

References

- Lindahl, B.D.; Ihrmark, K.; Boberg, J.; Trumbore, S.E.; Högberg, P.; Stenlid, J.; Finlay, R.D. Spatial separation of litter decomposition and mycorrhizal nitrogen uptake in a boreal forest. New Phytol. 2007, 173, 611–620. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S.E.; Read, D.J. Mycorrhizal Symbiosis, 3rd ed; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cairney, J.W.G. Translocation of solutes in ectomycorrhizal and saprotrophic rhizomorphs. Mycol. Res. 1992, 96, 135–141. [Google Scholar]

- Boddy, L. Saprotrophic cord-forming fungi: meeting the challenge of heterogeneous environments. Mycologia 1999, 91, 13–32. [Google Scholar]

- Cromack, K., Jr.; Sollins, P.; Graustein, W.C.; Speidel, K.; Todd, A.W.; Spycher, G.; Li, C.Y.; Todd, R.L. Calcium oxalate accumulation and soil weathering in mats of the hypogeous fungus Hysterangium crassum. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1979, 11, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Högberg, P. Mycorrhizal associations in some woodland and forest trees and shrubs in Tanzania. New Phytol. 1982, 92, 407–415. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, I.J.; Högberg, P. Ectomycorrhizas of tropical angiospermous trees. New Phytol. 1986, 102, 541–549. [Google Scholar]

- Högberg, P. 15N natural abundance as a possible marker of the ectomycorrhizal habit of trees in mixed African woodlands. New Phytol. 1990, 115, 483–486. [Google Scholar]

- Hosaka, K.; Castellano, M.A.; Spatafora, J.W. Biogeography of Hysterangiales (Phallomycetidae, Basidiomycota). Mycol. Res. 2008, 112, 448–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, K.L.; Zak, D.R.; Edwards, I.P.; Blackwood, C.B.; Upchurch, R. Slowed decomposition is biotically mediated in an ectomycorrhizal, tropical rain forest. Oecologia 2010, 164, 785–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trappe, J.M.; Claridge, A.W. The hidden life of truffles. Sci. Amer. 2010, 302, 78–84. [Google Scholar]

- Sbrana, C.; Fortuna, P.; Giovannetti, M. Plugging into the network, belowground connections between germlings and extraradical mycelium of arbuscular myocorrhizal fungi. Mycologia 2011, 103, 307–316. [Google Scholar]

- Courty, P.-C.; Buée, M.; Diedhiou, A.G.; Frey-Klett, P.; Le Tacon, F.; Rineau, F.; Turpault, M.-P; Uroz, S.; Garbaye, J. The role of communities in forest ecosystem processes, new perspectives and emerging concepts. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2010, 42, 679–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindahl, B.D.; Finlay, R.D.; Cairney, J.W.G. Enzymatic activities of mycelia in mycorrhizal communities. In The fungal community, its organization and role in the ecosystem, 3rd; Dighton, J., White, J.F., Oudemans, P., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005; pp. 331–348. [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl, B.D.; de Boer, W.; Finlay, R.D. Disruption of root carbon transport into forest humus stimulates fungal opportunists at the expense of mycorrhizal fungi. ISME Journal 2010, 4, 872–881. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.P.; Unestam, T.; Lucas, S.D.; Johanson, K.J.; Kenne, L.; Finlay, R. Exudation-reabsorption in a mycorrhizal fungus, the dynamic interface for interactions with soil and soil microorganisms. Mycorrhiza 1999, 9, 137–144. [Google Scholar]

- St. John, T.V.; Coleman, D.C.; Reid, C.P.P. Association of vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal hyphae with soil organic particles. Ecology 1983, 64, 957–959. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, D.C. From peds to paradoxes, linkages between soil biota and their influences on ecological processes. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2008, 40, 271–289. [Google Scholar]

- Cromack, K., Jr.; Fichter, B.L.; Moldenke, A.; Entry, J.A.; Ingham, E.R. Interactions between soil animals and ectomycorrhizal fungal mats. Agric. Ecosys. Environ. 1988, 24, 161–168. [Google Scholar]

- Högberg, M.N.; Briones, M.J.I.; Keel, S.G.; Metcalfe, D.B.; Campbell, C.; Midwood, A.J.; Thornton, B.; Hurry, V.; Linder, S.; Näsholm, T.; Högberg, P. Quantification of effects of season and nitrogen supply on tree below-ground carbon transfer to ectomycorrhizal fungi and other soil organisms in a boreal pine forest. New Phytol. 2010, 187, 485–493. [Google Scholar]

- Högberg, M.N.; Högberg, P. Extramatrical ectomycorrhizal mycelium contributes one-third of microbial biomass and produces, together with associated roots, half the dissolved organic carbon in a forest soil. New Phytol. 2002, 154, 791–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleber, M.; Sollins, P.; Sutton, R. A conceptual model of organo-mineral interactions in soils: Self-assembly of organic molecular fragments into zonal structures on mineral surfaces. Biogeochemistry 2007, 85, 9–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kleber, M.; Johnson, M.G. Advances in understanding the molecular structure of soil organic matter, implications for interactions in the environment. Adv. Agron. 2010, 106, 77–141. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, M.W.I.; Torn, M.S.; Abiven, S.; Dittmar, T; Guggenberger, G.; Janssens, I.A.; Kleber, M.; Kögel-Knabner, I.; Lehmann, J.; Manning, D.A.C.; et al. Persistence of soil organic matter as an ecosystem property. Nature 2011, 478, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Vittadini, C. Monographia Tuberacearum; Ex Typographia F. Rusconi: Milan, Italy, 1831. [Google Scholar]

- Vittadini, C. Monographia Lycoperdineorum; Ex Officina Regia: Torino, Italy, 1842. [Google Scholar]

- Tulasne, L.-R.; Tulasne, C. Fungi Hypogaei; Friedrich Klincksieck: Paris, France, 1851. [Google Scholar]

- Hesse, R. Die Hypogaeen Deutschlands. Die Hymenogastreen; Ludwig Hofstetter: Halle, Germany, 1891; Volume I. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsbottom, J. Mushrooms and toadstools; Collins: London, UK, 1953; pp. 132–137. [Google Scholar]

- Hawker, L.E. British hypogeous fungi. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. London, Series B, Biol. Sci. 1954, 237, 429–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, F.H. Laccaria amythestina (Bolt. ex Fr.) Berk. et Br., Ein zur mykorrhizabildung an der buche befähigter pilz. Ber. Dtsch. Bot. Ges. 1963, 76, 90–96. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, R.F. Spodosol development and nutrient distribution under Hydnaceae fungal mats. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. Proc. 1972, 36, 492–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, R.P.; Caldwell, B.A.; Cromack, K., Jr.; Morita, R.Y. Douglas-fir forest soils colonized with ectomycorrhizal mats. I. Seasonal variation in nitrogen chemistry and nitrogen cycle transformations. Can. J. For. Res. 1990, 20, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unestam, T.; Sun, Y.-P. Extramatricular structures of hydrophilic and hydrophobic ectomycorrhizal fungi. Mycorrhiza 1995, 5, 301–311. [Google Scholar]

- Nouhra, E.; Horton, T.R.; Cazares, E.; Castellano, M.A. Morphological and molecular characterization of selected Ramaria mycorrhizae. Mycorrhiza 2005, 15, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agerer, R. Fungal relationships and structural identity of their ectomycorrhizae. Mycol. Progress 2006, 5, 67–107. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, R.P.; Bradshaw, G.A.; Marks, B.; Lienkaemper, G.W. Spatial distribution of ectomycorrhizal mats in coniferous forests of the Pacific Northwest, USA. Plant Soil 1996, 180, 147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Dunham, S.M.; Larsson, K.-H.; Spatafora, J.W. Species richness and community composition of mat-forming ectomycorrhizal fungi in old- and second-growth Douglas-fir forests of the HJ Andrews Experimental Forest, Oregon, USA. Mycorrhiza 2007, 17, 633–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluber, L.A.; Tinnesand, K.M.; Caldwell, B.A.; Dunham, S.M.; Yarwood, R.R.; Bottomley, P.J.; Myrold, D.D. Ectomycorrhizal mats alter forest soil biogeochemistry. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2010, 42, 1607–1612. [Google Scholar]

- Entry, J.A.; Rose, C.L.; Cromack, K., Jr. Microbial biomass and nutrient concentrations in hyphal mats of the ectomycorrhizal fungal Hysterangium setchellii in a coniferous forest soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1992, 24, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, L.; Griffiths, R.P.; Caldwell, B.A. Nitrogen in ectomycorrhizal mat and non-mat soils of different-age Douglas-fir forests. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1993, 8, 1015–1019. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, R.P.; Baham, J.E.; Caldwell, B.A. Soil solution chemistry of ectomycorrhizal mats in forest soil. Soil Boil. Biochem. 1994, 26, 331–337. [Google Scholar]

- Rosling, A.; Finlay, R.D. Response of different ectomycorrhizal fungi to mineral substrates. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2005, 69, 222–232. [Google Scholar]

- Finlay, R.; Wallander, H.; Smits, M.; Holmstrom, S.; van Hees, P.; Lian, B.; Rosling, A. The role of fungi in biogenic weathering in boreal forest soils. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2009, 23, 101–106. [Google Scholar]

- Rosling, A. Trees, mycorrhiza and minerals—Field relevance of in vitro experiments. GeomicroBiol. J. 2009, 26, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unestam, T. Water repellency, mat formation, and leaf-stimulated growth of some ectomycorrhizal fungi. Mycorrhiza 1991, 1, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, R.P.; Castellano, M.A.; Caldwell, B.A. Hyphal mats formed by two ectomycorrhizal fungi and their association with Douglas-fir seedlings, A case study. Plant Soil 1991, 134, 255–259. [Google Scholar]

- Simard, S.W.; Perry, D.A.; Jones, M.D.; Myrold, D.D.; Durall, D.M.; Molina, R. Net transfer of carbon between ectomycorrhizal tree species in the field. Nature 1997, 388, 579–582. [Google Scholar]

- Durall, D.M.; Todd, A.W.; Trappe, J.M. Decomposition of 14C-labelled substrates by ectomycorrhizal fungi in association with Douglas-fir. New Phytol. 1994, 127, 725–729. [Google Scholar]

- Entry, J.A.; Donnelly, P.K.; Cromack, K., Jr. Influence of ectomycorrhizal mat soils on lignin and cellulose degradation. Biol. Fert. Soils 1991, 11, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, R.P.; Caldwell, B.A. Mycorrhizal mat communities in forest soils. In Mycorrhizas in Ecosystems; Read, D.J., Lewis, D.H., Fitter, A.H., Alexander, I.J., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 1992; pp. 98–105. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell, B.A.; Castellano, M.A.; Griffiths, R.P. Fatty acid esterase production by ectomycorrhizal fungi. Mycologia 1991, 83, 233–236. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, R.P.; Ingham, E.R.; Caldwell, B.A.; Castellano, M.A.; Cromack, K., Jr. Microbial characteristics of ectomycorrhizal mat communities in Oregon and California. Biol. Fert. Soils 1991, 11, 196–202. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, C.L. Distinguishing biological and physical controls on soil respiration. Ph.D. Dissertation, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Agerer, R.; Otto, P. Bankera fuligineo-alba Fr. + Fagus sylvatica L. Descr. Ectomyc. 1997, 3, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Agerer, R. Studies on ectomycorrhiza. LIV. Ectomycorrhizae of Boletopsis leucomelaena (Thelephoraceae, Basidiomycetes) and their relationship to an unidentified ectomycorrhiza. Nova Hedw. Krypt. 1992, 55, 501–518. [Google Scholar]

- Bougher, N.L.; Malajczuk, N. An undescribed species of hypogeous Cortinarius associated with Eucalyptus in western Australia. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1986, 86, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agerer, R.; Beenken, L. Geastrum imbricatum (J.C. Schmidt., Fr.) Pouzar + Pinus sylvestris L. Descr. Ectomyc. 1998, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Agerer, R.; Beenken, L.; Christian, J. Gomphus clavatus (Pers., Fr.) S.F. Gray + Picea abies (L.) Karst. Descr. Ectomyc. 1998, 3, 25–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hintikka, V. Some types of mycorrhizae in the humus layer of conifer forests in Finland. Karstenia 1974, 14, 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Hintikka, V.; Näykki, O. Notes on the effects of the fungus Hydnellum ferruginieum (Fr.) Karst. on forest soil and vegetation. Comm. Inst. For. Fenn. 1967, 62, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Agerer, R. Ectomycorrhizae of Phellodon niger on Norway spruce and their chlamydospores. Mycorrhiza 1992, 2, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikola, P. The bright yellow mycorrhiza of raw humus. In The Proceedings of the 13th Congress of the INTERNATIONAL Union of Forest Research Organizations, Vienna, Austria, September 1961.

- Marr, C.D.; Stuntz, D.E. Ramaria of western Washington. In Bibl Mycol Band 38; Verlag von J. Cramer: Leutershausen, Germany, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Agerer, R. Ectomycorrhizae of Sarcodon imbricatus on Norway spruce and their chlamydospores. Mycorrhiza 1991, 1, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, M.; Hamada, M. Microbial ecology of ‘shiro’ in Tricholoma matsutake (S. Ito et Imai) Sing. and its allied species. Trans. Mycol. Soc. Jap. 1965, 6, 67–71. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, J.F.; Dyrness, C.T. Natural vegetation of Oregon and Washington; General Technical Report for USDA Forest Service PNW Research Station: Portland, OR, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Perrakis, D.D.B.; Agee, J.K. Seasonal fire effects on mixed-conifer forest structure and pine resin properties. Can. J. For. Res. 2006, 36, 238–254. [Google Scholar]

- Trappe, M.J.; Perrakis, D.D.B.; Cromack, K., Jr.; Trappe, J.M.; Cazares, E.; Castellano, M.A.; Miller, S.L. Interactions among prescribed fire, soil attributes, and mycorrhizal community structure at Crater Lake National Park. Fire Ecol. 2009, 5, 30–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeil, R.C.; Zobel, D.B. Vegetation and fire history of a ponderosa pine-white fir forest in Crater Lake National Park. Northwest Sci. 1980, 54, 30–46. [Google Scholar]

- Trappe, M.J.; Cromack, K., Jr.; Trappe, J.M.; Wilson, J.; Rasmussen, M.C.; Castellano, M.A.; Miller, S.L. Relationships of current and past anthropogenic disturbances to mycorrhizal sporocarp fruiting patterns at Crater Lake National Park, Oregon. Can. J. For. Res. 2009, 39, 1662–1676. [Google Scholar]

- Chappell, C.B.; Agee, J.K. Fire severity and tree seedling establishment in Abies magnifica forests, southern Cascades, Orego. Ecol. Appl. 1996, 6, 628–640. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, J.K. The Effects of Natural Fire and Recreational Disturbance on Montane Forest Ecosystem Composition, Structure and Nitrogen Dynamics, Crater Lake National Park, Oregon. Ph.D. Dissertation, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- USDI National Park Service, Green, L.W. Historic resource study, Crater Lake National Park, Oregon; Branch of Cultural Resources: Denver, CO, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Gardes, M.; Bruns, T.D. ITS-RFLP matching for identification of fungi. In Methods in Molecular Biology, Vol. 50: Species Diagnostic Protocols, PCR and Other Nucleic Acid Methods; Clapp, J.P., Ed.; Hamana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 1996; pp. 177–186. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, R.H.; Ryberg, M.; Kristiansson, E.; Abarenkov, K.; Larsson, K-H.; Kõljalg, U. Taxonomic reliability of DNA sequences in public sequence databases, a fungal ferspective. PLoS ONE 2006, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoefs, J. Stable Isotope Geochemistry; Springer-Verlag: Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J.K. Handbook for Inventorying Downed Woody Material; General Technical Report INT-GTR-16 for USDA Forest Service Intermountain West Research Station: Ogden, UT, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Van Wagtendonk, J.W.; Benedict, J.M.; Sydoriak, W.M. Physical properties of woody fuel particles of Sierra Nevada conifers. Intl. J. Wildl. Fire 1996, 6, 117–123. [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute, SAS statistical analysis software: Version 9.1, SAS Institute: Cary, NC, USA, 2003.

- Hobbie, E.A.; Horton, T.R. Evidence that saprotrophic fungi mobilize carbon and mycorrhizal fungi mobilize nitrogen during litter decomposition. New Phytol. 2007, 173, 447–449. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, D.A.; Griffiths, R.P.; Moldenke, A.R.; Madson, S.L. The influence of forest age and structure on abiotic and biotic patterns in soils and litter. Diversity 2012, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Agerer, R. Exploration types of mycorrhizae. A proposal to classify ectomycorrhizal mycelial systems according to their patterns of differentiation and putative ecological importance. Mycorrhiza 2001, 11, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.F.S.; Fransson, P.M.; Högberg, P.; Högberg, M.N.; Plamboeck, A.H. Species level patterns in 13C and 15N abundance of ectomycorrhizal and saprotrophic fungal sporocarps. New Phytol. 2003, 159, 757–774. [Google Scholar]

- Van Schöll, L.; Kuyper, T.W.; Smits, M.M.; Landeweert, R.; Hoffland, E.; van Breemen, N. Rock-eating mycorrhizas, their role in plant nutrition and biogeochemical cycles. Plant Soil 2008, 303, 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, N. Nutrient cycling pathways and litter fungi. Bioscience 1972, 22, 355–360. [Google Scholar]

- Swift, M.J.; Heal, O.W.; Anderson, J.M. Decomposition in Terrestrial Ecosystems; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Dighton, J. Fungi in Ecosystem Processes; Marcel Dekker, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cromack, K., Jr.; Todd, R.L.; Monk, C.D. Patterns of basidiomycete nutrient accumulation in conifer and deciduous forest litter. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1975, 7, 265–268. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.H.; Bledsoe, C.S.; Zasoski, R.J.; Southworth, D.; Horwath, W.R. Rapid nitrogen transfer from ectomycorrhizal pines to adjacent ectomycorrhizal and arbuscular mycorrhizal plants in a California oak woodland. New Phytol. 2006, 170, 143–151. [Google Scholar]

- Querejeta, J.I.; Egerton-Warburton, L.M.; Allen, M.F. Hydraulic lift may buffer rhizosphere hyphae against the negative effects of severe soil drying in a California oak savanna. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2007, 39, 409–417. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, J.M.; Brooks, J.R.; Meinzer, F.C.; Eberhart, J.L. Hydraulic redistribution of water from Pinus ponderosa trees to seedlings: evidence for an ectomycorrhizal pathway. New Phytol. 2008, 178, 382–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.F.S.; Gebauer, G.; Read, D.J. Uptake of nitrogen and carbon from double-labelled 15N and 13C glycine by mycorrhizal pine seedlings. New Phytol. 2004, 164, 383–388. [Google Scholar]

- Trudell, S.A.; Rygiewicz, P.T.; Edmonds, R.L. Patterns of nitrogen and carbon stable isotope ratios in macrofungi, plants and soils in two old-growth conifer forests. New Phytol. 2004, 164, 317–335. [Google Scholar]

- Hobbie, E.A.; Agerer, R. Nitrogen isotopes in ectomycorrhizal sporocarps correspond to belowground exploration types. Plant Soil 2010, 327, 71–83. [Google Scholar]

- Tuason, M.M.S.; Arocena, J.M. Calcium oxalate biomineralization by Piloderma fallax in response to various levels of calcium and phosphorus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 7079–7085. [Google Scholar]

- Kluber, L.A.; Smith, J.E.; Myrold, D.D. Distinctive fungal and bacterial communities are associated with mats formed by ectomycorrhizal fungi. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011, 43, 1042–1050. [Google Scholar]

- Leake, J.; Johnson, D.; Donnelly, D.; Muckle, G.; Boddy, L.; Read, D. Networks of power and influence, the role of mycorrhizal mycelium in controlling plant communities and agroecosystem functioning. Can. J. Bot. 2004, 82, 1016–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treseder, K.K.; Allen, M.F.; Ruess, R.W.; Pregitzer, K.S.; Hendrick, R.L. Lifespans of fungal rhizomorphs under nitrogen fertilization in a Pinyon-Juniper woodland. Plant Soil 2005, 270, 249–255. [Google Scholar]

- Simard, S.W. The foundational role of mycorrhizal networks in self-organization of interior Douglas-fir forests. For. Ecol. Manage. 2009, 158, S95–S107. [Google Scholar]

- Berbee, M.L.; Taylor, J.W. Dating the evolutionary radiation of the true fungi. Can. J. Bot. 1993, 71, 1114–1127. [Google Scholar]

- Högberg, P.; Nordgren, A.; Buchmann, N.; Taylor, A.F.S.; Ekblad, A.; Högberg, M.N.; Nyberg, G.; Ottosson-Löfvenius, M.; Read, D.J. Large-scale forest girdling shows that current photosynthesis drives soil respiration. Nature 2001, 411, 789–792. [Google Scholar]