First Records of Bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera) from the World’s Largest Cave in Vietnam

Abstract

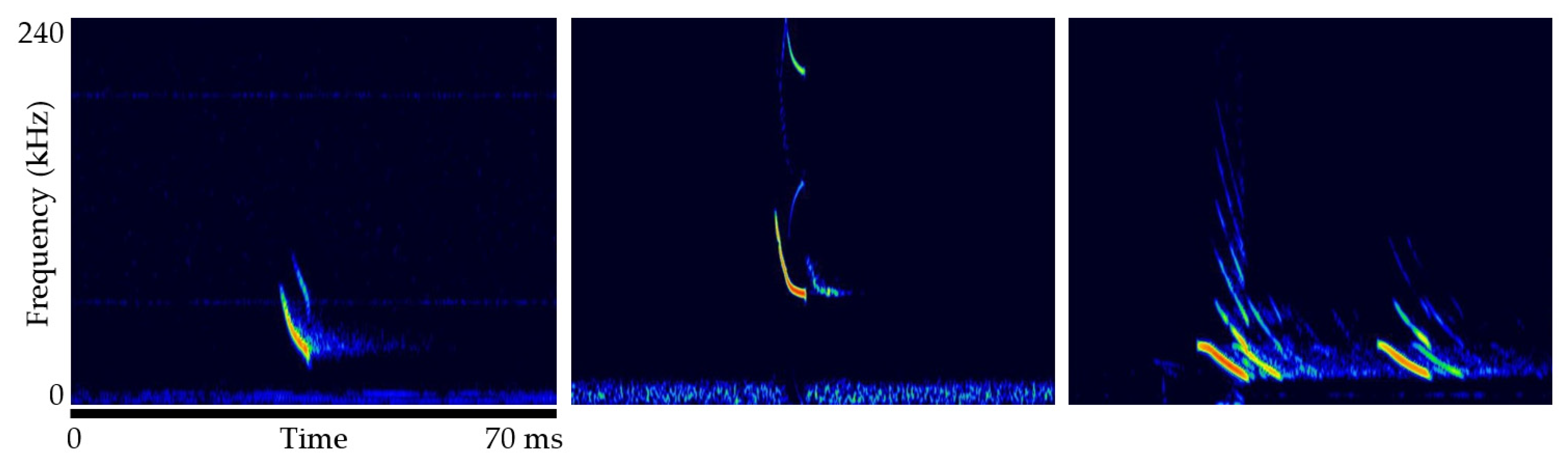

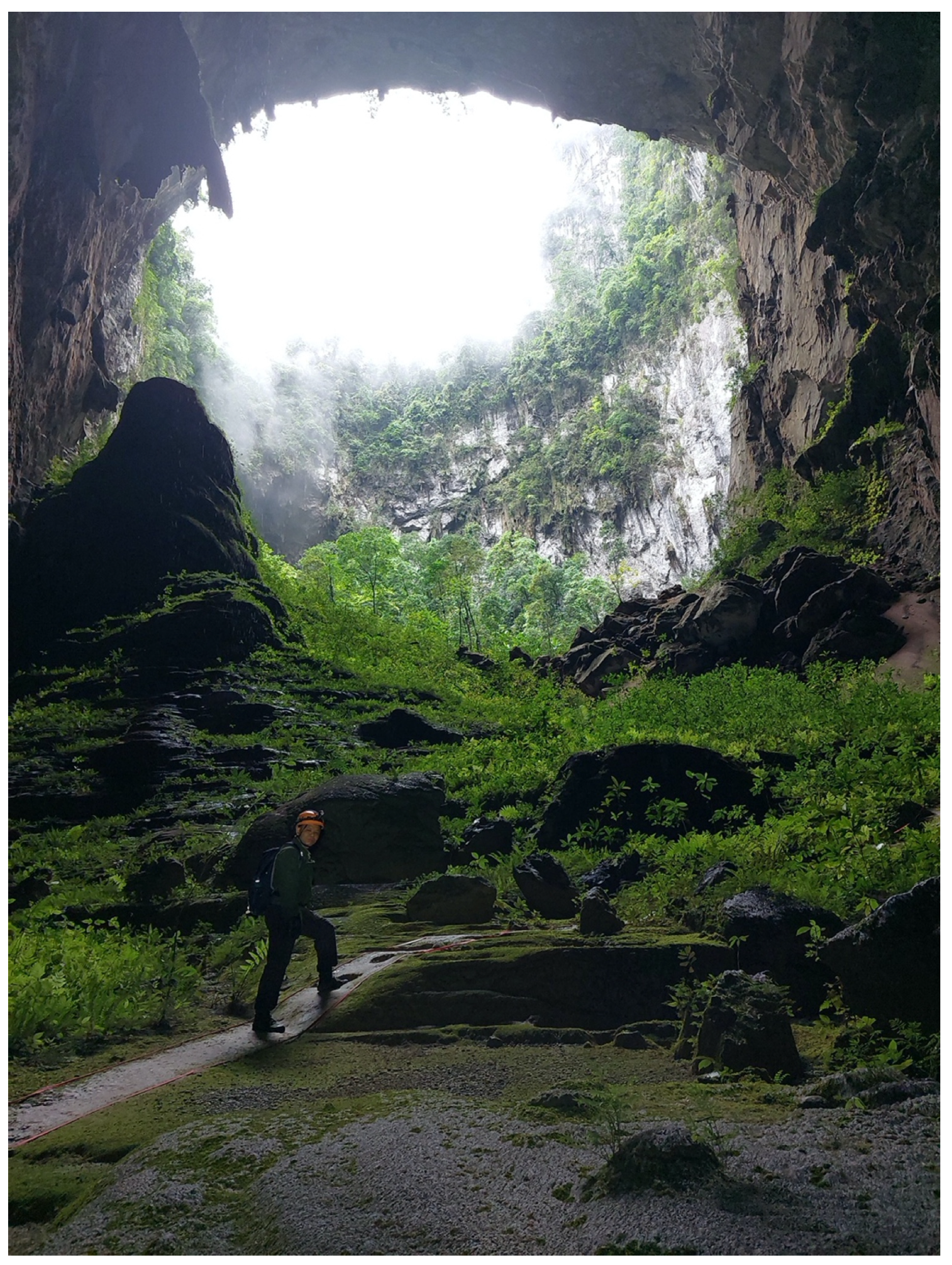

1. Introduction

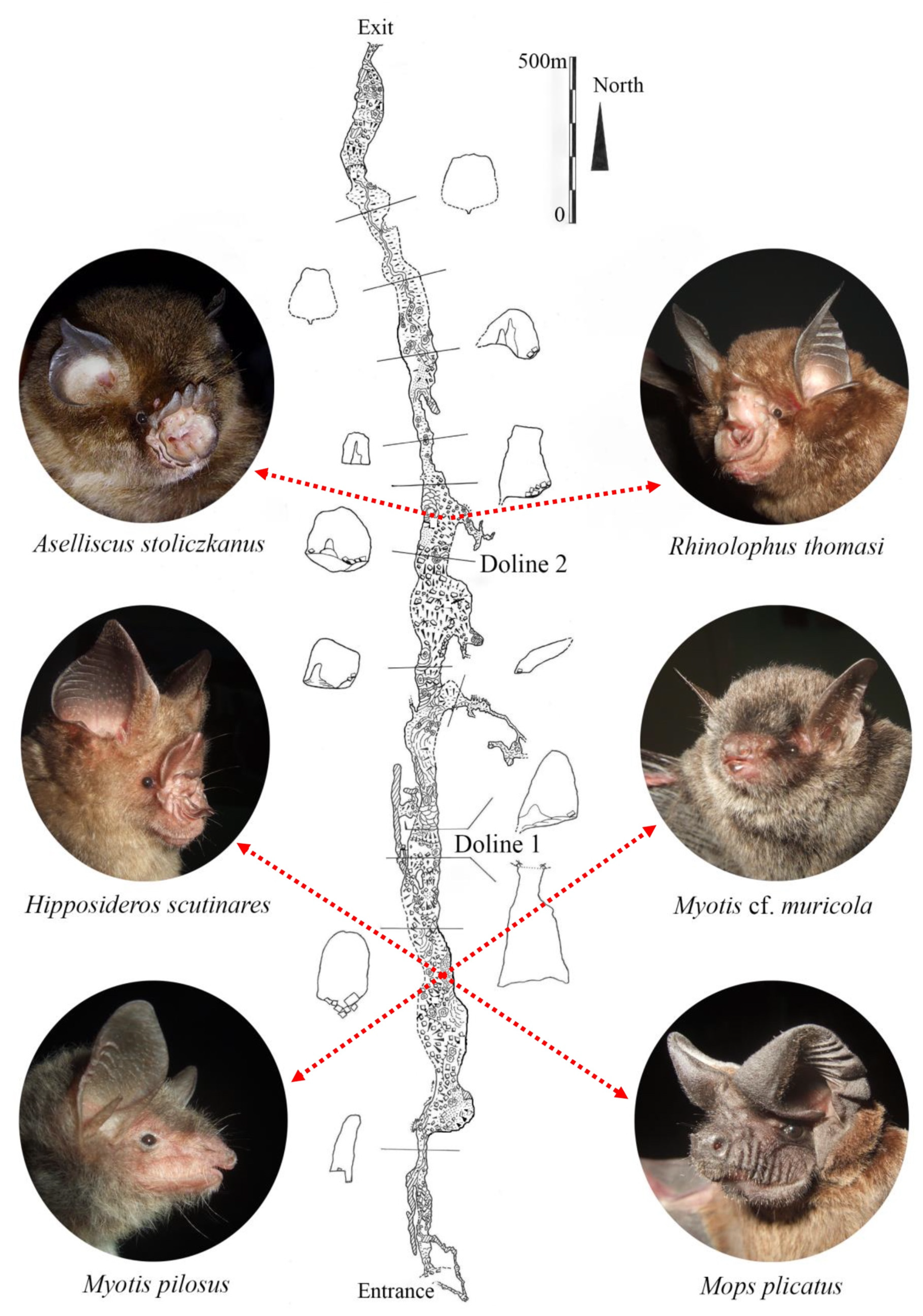

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bat Capture and Morphological Measurements

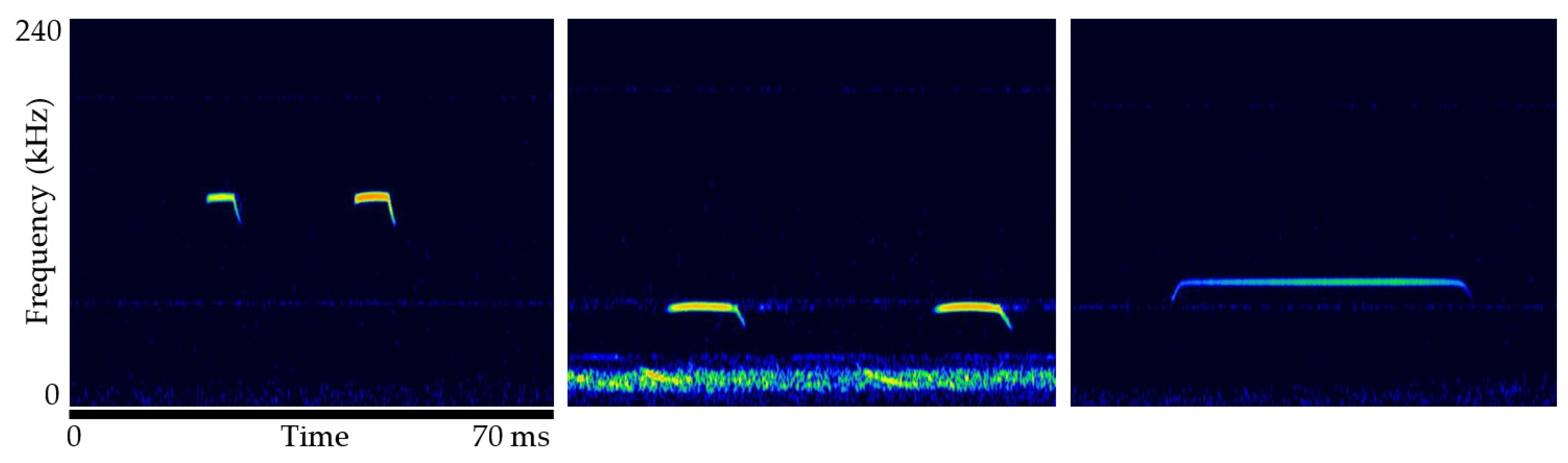

2.2. Echolocation Recording and Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tu, D.V.; Cuong, N.T. A new species of troglobitic freshwater prawn of the genus Macrobrachium Bate, 1868 (Crustacea: Decapoda: Palaemonidae) from Phong Nha-Ke Bang National Park, Quang Binh province. Tap Chi Sinh Hoc. Vietnam. J. Biol. 2014, 36, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong, T.D.; Holynska, M. A new Mesocyclops with archaic morphology from a karstic cave in central Vietnam, and its implications for the basal relationships within the genus. Ann. Zool. 2015, 65, 661–686. [Google Scholar]

- Luong, T.D.; Hai, H.T.; Anh, L.H.; Minh, L.D. Biodiversity of cave-dwelling microcrustacean in Phong Nha-Ke Bang National Park, Quang Binh province. In Proceedings of the 6th National Conference on Ecology and Biological Resources, Hanoi, Vietnam, 20 September 2015; pp. 665–670. [Google Scholar]

- Tai, V.A.; Hieu, N.; Limbert, H. Firstly results of botanical research at Hang Son Doong—The biggest cave of the world. Vietnam J. Sci. Technol. 2014, 52, 419–434, (In Vietnamese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Sikes, R.S.; Gannon, W.L. The Animal Care and Use Committee of the American Society of Mammalogists. Guidelines of the American Society of Mammalogists for the use of wild mammals in research. J. Mammal. 2011, 92, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikes, R.S.; Animal Care and Use Committee of the American Society of Mammalogists. 2016 Guidelines of the American Society of Mammalogists for the use of wild mammals in research and education. J. Mammal. 2016, 97, 663–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borissenko, A.V.; Kruskop, S.V. Bats of Vietnam and Adjacent Territories: An Identification Manual; Joint Russian-Vietnamese Science and Technological Tropical Centre: Moscow, Russia; Hanoi, Vietnam, 2003; pp. 1–212. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, P.J.J.; Harrison, D.L. Bats of the Indian Subcontinent; Harrison Zoological Museum: Sevenoaks, UK, 1997; pp. 1–258. [Google Scholar]

- Kruskop, S.V. Bats of Vietnam: Checklist and an Identification Manual, 2nd ed.; KMK Ltd.: Moscow, Russia, 2013; pp. 1–300. [Google Scholar]

- Racey, P.A. Reproductive assessment in bats. In Ecological and Behavioral Methods for the Study of Bats; Kunz, T.H., Parsons, S., Eds.; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2009; pp. 249–264. [Google Scholar]

- Brunet-Rossinni, A.K.; Wilkinson, G.S. Methods for age estimation and the study of senescence in bats. In Ecological and Behavioral Methods for the Study of Bats; Kunz, T.H., Parsons, S., Eds.; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2009; pp. 315–325. [Google Scholar]

- Thong, V.D. Systematics and Echolocation Of Rhinolophoid Bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera) in Vietnam. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Tuebingen, Tuebingen, Germany, 4 April 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Thong, V.D. Taxonomy and Echolocation of Bats in Vietnam; Publishing House for Science and Technology: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2021; 257p. [Google Scholar]

- Thong, V.D.; Tien, P.D.; Son, N.T.; Lua, T.T.; Thuy, V.T.; Thiep, N.T.; Vuong, P.K.; Tuan, D.H.; Dinh, L.T. Biodiversity survey of bats in and around the Phong Nha-Ke Bang National Park, Quang Binh, Vietnam; A report for the Nature Conservation and Sustanable Natural Resources Management in Phong Nha—Ke Bang National Park project, Quang Binh: Bố Trạch District, Vietnam, 2012; 24p. [Google Scholar]

- Thong, V.D.; Denzinger, A.; Sang, N.V.; Huyen, N.T.T.; Thanh, H.T.; Loi, D.N.; Nha, P.V.; Viet, N.V.; Tien, P.D.; Tuanmu, M.-N.; et al. Bat Diversity in Cat Ba Biosphere Reserve, Northeastern Vietnam: A Review with New Records from Mangrove Ecosystem. Diversity 2021, 13, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thong, V.D.; Denzinger, A.; Long, V.; Sang, N.V.; Huyen, N.T.T.; Thien, N.H.; Luong, N.K.; Tuan, L.Q.; Ha, N.M.; Luong, N.T.; et al. Importance of Mangroves for Bat Research and Conservation: A Case Study from Vietnam with Notes on Echolocation of Myotis hasselti. Diversity 2022, 14, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furey, N.M.; Mackie, I.J.; Racey, P.A. The role of ultrasonic bat detectors in improving inventory and monitoring in Vietnamese karst bat assemblages. Curr. Zool. 2009, 55, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, K.B.; Park, Y.C. Echolocation Call Structure and Intensity of the Malaysian Myotis muricola (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae). J. For. Environ. Sci. 2016, 32, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Viet, N.V.; Nga, C.T.T. Emerging threats to the largest colony of bats in Vietnam and recommendations for sustainable conservation. Acad. J. Biol. 2021, 43, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thai, D.V.; Loi, D.N. New acoustic and distributional records of Mops plicatus (Chiroptera: Molossisae) from Vietnam. Hnue J. Sci. 2022, 67, 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Thong, V.D. Taxonomic and distributional assessments of Chaerephon plicatus (Chiroptera: Molossidae) from Vietnam. Tap Chi Sinh Hoc. Vietnam. J. Biol. 2014, 36, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.E.; Mittermerier, R.A.; Martinez-Vilalta, A.; Leslie, D.M.; Olive, M.; Elliott, A.; Velikov, I.; Mascarell, A.; Sogorb, L.; Marti, B.; et al. Handbook of the Mammals of the World; Lynx Edicions: Barcelona, Spain, 2019; pp. 1–1008. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrichsen, D.K.; Bates, P.J.J.; Hayes, B.D.; Walston, J.L. Recent records of bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera) from Vietnam with six species new to the country. Myotis 2002, 39, 35–122. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, M.F.; Jenkins, P.D.; Francis, C.M.; Fulford, A.J. A new species of the Hipposideros pratti group (Chiroptera, Hipposideridae) from Lao PDR and Vietnam. Acta Chiropterologica 2003, 5, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | n | Sex | FA | EH | TIB | HF | T | Capture Site Zone |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. stoliczkanus | 2 | ♀♀ | 43.4; 42.9 | 11.3; 9.2 | 19.5; 18.1 | 6.2; 6.3 | 38.8; 36.2 | Doline 2 |

| H. scutinares | 1 | ♂ | 79.4 | 28.5 | 37.5 | 18.5 | 49.9 | Doline 1 |

| R. thomasi | 2 | ♀♀ | 43.5; 46.9 | 16.5; 20.3 | 17.8; 18.2 | 8.6; 8.9 | 23.6; 26.8 | Doline 2 |

| 1 | ♂ | 46.6 | 20 | 17.5 | 8.9 | 26.6 | Doline 2 | |

| M. pilosus | 1 | ♀ | 56.8 | 17.9 | 19.8 | 16.9 | 46.8 | Doline 1 |

| 2 | ♂♂ | 53.5; 58.6 | 16.5; 18.2 | 18.8; 22.6 | 15.9; 16.8 | 46.2; 46.9 | Doline 1 | |

| M. cf. muricola | 2 | ♂♂ | 32.1; 32.3 | 10.0; 12.3 | 13.9; 14.5 | 7.1; 7.5 | 32.7; 33.6 | Doline 1 |

| M. plicatus | 1 | ♂ | 51.5 | 22.8 | 18.6 | 13.5 | 41.6 | Doline 1 |

| Species | n | iFM | CF | tFM | BW | PD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. stoliczkanus | 31 (second harmonic) | - | 128.7 ± 1.0 125.4–130.1 | 113.6 ± 2.5 109.9–120.7 | - | 5.3 ± 0.8 3.9–6.6 |

| H. scutinares | 32 (second harmonic) | - | 60.6 ± 0.9 59.2–62.9 | 45.1 ± 2.1 40.9–49.8 | - | 11.0 ± 1.5 7.0–13.5 |

| R. thomasi | 5 (second harmonic) | 62.9 ± 2.3 59.2–65.3 | 76.9 ± 0.2 76.6–77.0 | 64.5 ± 2.1 62.9–68.1 | - | 49.3 ± 6.0 43.8–58.4 |

| M. pilosus | 16 (first harmonic) | 69.3 ± 4.0 61.5–75.6 | - | 25.5 ± 1.7 23.0–28.6 | 43.7 ± 5.2 32.9–50.3 | 5.0 ± 0.3 4.6–5.6 |

| M. cf. muricola | 42 (first harmonic) | 105.2 ± 10.2 87.8–127.7 | - | 63.3 ± 1.3 61.1–65.8 | 41.8 ± 10.5 25.4–65.8 | 4.2 ± 0.6 2.7–5.0 |

| M. plicatus | 47 (first harmonic) | 38.4 ± 2.6 33.3–42.7 | - | 12.6 ± 2.1 8.5–16.9 | 25.8 ± 3.6 18.3–31.9 | 7.0 ± 3.4 3.4–17.1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Thong, V.D.; Limbert, H.; Limbert, D. First Records of Bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera) from the World’s Largest Cave in Vietnam. Diversity 2022, 14, 534. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14070534

Thong VD, Limbert H, Limbert D. First Records of Bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera) from the World’s Largest Cave in Vietnam. Diversity. 2022; 14(7):534. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14070534

Chicago/Turabian StyleThong, Vu Dinh, Howard Limbert, and Debora Limbert. 2022. "First Records of Bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera) from the World’s Largest Cave in Vietnam" Diversity 14, no. 7: 534. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14070534

APA StyleThong, V. D., Limbert, H., & Limbert, D. (2022). First Records of Bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera) from the World’s Largest Cave in Vietnam. Diversity, 14(7), 534. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14070534