1. Introduction

The genus

Psammornis was established in 1911 by Andrews [

1], with

P. rothschildi as the type species, on the basis of eggshell fragments collected in southern Algeria in the course of one of Lord Rothschild’s expeditions to North Africa [

2]. Since then, more eggshell material collected at a number of localities in Africa and the Middle East has been attributed to

Psammornis; this rather enigmatic taxon has been the subject of much speculation, both because it is represented solely by fragmentary eggshell material not clearly associated with any skeletal remains, and because the stratigraphic provenance of the specimens is often very uncertain due to many of them being surface-collected rather than found in situ in sedimentary formations. Despite these uncertainties,

Psammmornis is still often mentioned in works on ostrich evolution [

3] as well as in papers on fossilisation [

4], with different geological age estimates—Pleistocene, according to Mikhailov and Zelenkov [

3], and Holocene, according to Wiemann et al. [

4].

The systematic position of

Psammornis has been the subject of much debate [

5]. Although aepyornithid affinities have been suggested [

6,

7] and Dughi and Sirugue [

8,

9] thought that the microstructure of

Psammornis eggshells was closer to that of rheas and moas, it is now widely accepted that the

Psammornis eggs are probably those of giant ostriches [

1,

3,

5,

10]; according to Mikhailov and Zelenkov [

3], they belong to their “non-specialised type S”, and are similar to both the thin-shelled eggs of the modern subspecies

Struthio camelus camelus and the thick-shelled eggs of the Pliocene

S. chersonensis from Europe. However, the purpose of the present paper is not to discuss systematic issues or morphological and microstructural characteristics, but to review whatever solid evidence may be available about the stratigraphic provenance of

Psammornis eggshells, on the basis of a survey of the available literature; this includes papers, mainly in French, which have been overlooked by many authors dealing with the question. Bearing in mind that the geological age of the type material of

Psammornis rothschildi can rightly be considered as uncertain [

11], widely different opinions have been expressed about the geological age of

Psammornis specimens from various localities; this, in turn, has resulted in divergent interpretations of ratite evolutionary history in Africa and other continents.

2. The Discovery of Psammornis and the Beginning of the Stratigraphic Conundrum

In 1909, during a visit to southern Algeria, Lord Rothschild and Ernst Hartert explored the area around the city of Touggourt [

2], in the north-eastern part of the Algerian Sahara. They found abundant fragments of ostrich eggshell on the ground in various places. While picking up some of them about 22 miles east of Touggourt, Hartert found “three pieces of a very much thicker egg-shell of a much browner colour” ([

2], p. 550). Rothschild immediately thought that they must belong to “an extinct large Struthionid bird”. The fragments were handed over for study to C.W. Andrews, a palaeontologist at the British Museum (Natural History), who described them as

Psammornis rothschildi [

1]. Andrews gave a detailed, but not illustrated, description of the microstructure and surface features of the eggshell, noting its considerable thickness (3.2 to 3.4 mm), much greater than that of eggs of the living ostrich (up to 2.10 mm) and second only to that of the eggshell of

Aepyornis titan, from Madagascar. His conclusion was that the fragments were evidence of a “hitherto unknown bird which laid an egg considerably larger than the largest produced by any modern ostrich” and that, although there were some similarities with

Aepyornis, “with

Struthio the relationship was probably very close” ([

1], p. 172).

Besides the lack of associated skeletal material, which made precise identification difficult, Andrews also noted uncertainties about the geological age of the specimens. Although they had been surface-collected and had been abraded by drifting sand, they were highly mineralised and had been found in the vicinity of a well. Andrews suggested that they might have been brought up from a considerable depth when digging the well. This gave no clue as to the exact antiquity of the eggshell fragments. Hartert [

12], discussing

Psammornis-like eggshell fragments found in the western Algerian Sahara, questioned Andrews’ suggestion, pointing out that the

Psammornis fragments often had the same preservation as

Struthio camelus eggshell fragments and, everywhere, were found together with the latter.

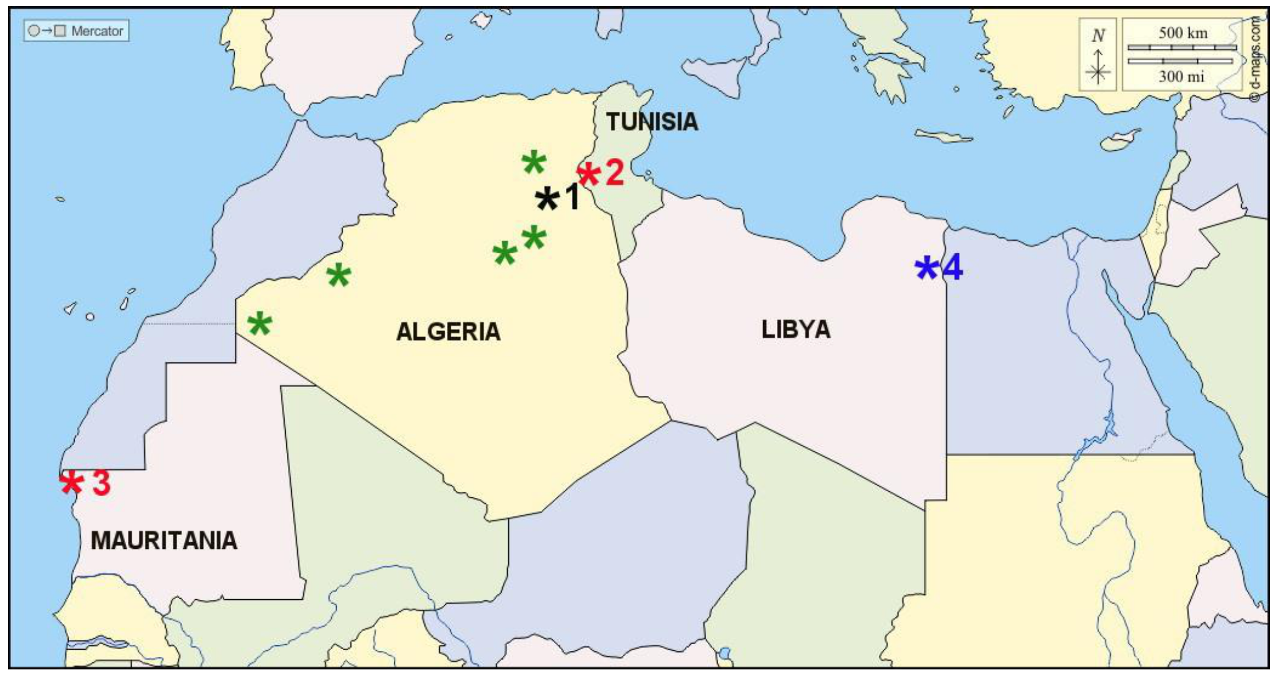

Since the initial discovery in Algeria, many eggshell fragments (but no complete eggs) attributed to

Psammornis have been reported from various parts of North Africa (including Algeria, Tunisia and Mauritania;

Figure 1) and the Middle East (Saudi Arabia, Iran), but many of them were surface-collected and lack details about their stratigraphic origin. In addition, some of these purported

Psammornis specimens appear to be significantly different from the fragments described by Andrews [

1], and their attribution to the genus seems dubious.

3. An Eocene Age for Psammornis?

Rothschild [

13] (1911) listed

Psammornis among what he called the Heterornithes, a loosely defined group of large birds which he considered as “fore-runners or ancestral forms of the Ratite section of the Palaeognathae” ([

13], p. 148). This highly heterogenous group contained birds as different as gastornithids, phorusrhacoids and even the Jurassic

Laopteryx (now considered a pterosaur).

Psammornis was listed together with

Eremopezus eocaneus as an Eocene representative of the Heterornithes from North Africa.

Eremopezus eocaneus was described by Andrews [

14] on the basis of the distal end of a tibiotarsus from the Upper Eocene Jebel Qatrani Formation of the Fayum, in Egypt. It was long believed to be an early ratite, but Rasmussen et al. [

15] considered it a representative of an endemic group of large African birds.

Why Rothschild chose to associate

Psammornis and

Eremopezus is obscure. In his description of

Psammornis, Andrews [

1] mentioned

Eremopezus, mainly to remark that it was only the size of a small ostrich (and, therefore, unlikely to have produced eggs the size of

Psammonis eggs). Moreover, there was no solid reason to believe that the type material of

Psammornis from Algeria came from an Eocene deposit, despite the fact that Andrews had suggested that the fragments might have been brought up to the surface from a considerable depth by a well. However, as mentioned above, as early as 1913, Hartert [

12] had doubted that the Algerian

Psammornis fragments could have been brought up to the surface by a well, and in 1918, Geyr von Schweppenburg [

16] had noted that it was geologically unlikely that they were Eocene in age. The hypothesis that the Algerian specimens may have originated from Eocene deposits was dismissed on geological evidence by Dughi and Sirugue [

8,

9]. Sauer [

5] reviewed, at some length, the question of the possible relationships between

Psammornis and

Eremopezus and concluded that there was no reason to believe they were related.

Nonetheless, Rothschild’s idea of an Eocene age for

Psammornis was taken up first by Abel [

17] and then by Lambrecht [

6], who placed it together with

Eremopezus in the family Eremopezinae within the Aepyornithformes. In 1933, Lambrecht [

7] still placed

Psammornis close to

Eremopezus but as a genus

incertae sedis, and gave it an Eocene age with a question mark. More recently, Piveteau [

18] noted that

Psammornis had been discovered in the Eocene of Touggourt. Brodkorb [

19] still considered

Psammornis as a possible synonym of

Eremopezus, and also attributed it to the Eocene, with a question mark. Dementiev [

20] used question marks concerning the placement of

Psammornis among the “Eremopezidae” and its attribution to the Eocene. As late as 1965, Swinton [

21] wrote that

Psammornis had been found in the Eocene of southern Algeria. Obviously, Rothschild’s ill-founded assertion that

Psammornis was an Eocene taxon has had long-lasting consequences. There is, in fact, no convincing stratigraphic evidence anywhere suggesting that

Psammornis-type eggshells have been found in Eocene deposits.

6. Psammornis from Tunisia: A Late Miocene Record?

As early as 1911, Rothschild and Hartert [

2] reported that the German naturalists Erlanger and Hilgert had found many fragments of large eggshells in the South Tunisian desert. Bédé [

37] noted that he had found eggshell fragments of a brownish colour and thicker than those of the “ordinary ostrich” at Mezzouna, 100 km SW of the city of Sfax; he thought they belonged to

Psammornis.

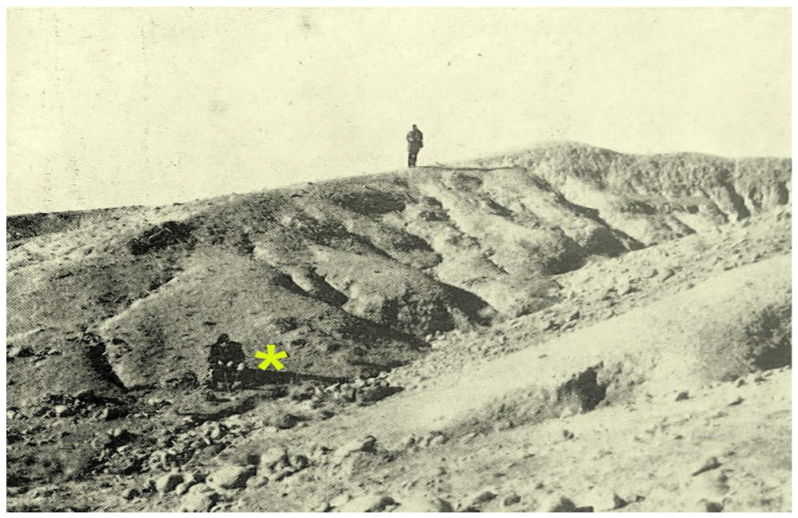

A stratigraphically more significant discovery of

Psammornis specimens was reported by Choumowitch (not ‘Choumwitch’ as erroneously printed in his paper) in 1951 [

38]. The eggshell fragments mostly came from outcrops SW of the city of Moularès, in south-western Tunisia. They were found in abundance in red beds deeply dissected by erosion (

Figure 2) in an area known as Chebket Safra (“yellow network”). The brown-coloured eggshell fragments were attributed to

Psammornis because of their thickness (3 mm). Choumowitch also noted that they were less convex than ostrich eggshells, thus indicating larger eggs.

As emphasised by Choumowitch, contrary to previous Psammornis finds, the eggshell fragments from Chebket Safra came from well-dated sediments. They were found in palaeosols containing calcareous concretions and fossil helicid gastropods, notably Leucochroa tissoti, considered as indicating a Pontian age. Choumowitch’s investigations showed that the eggshell fragments did not come from Quaternary pebble deposits topping the hills. Digging into the red clays to a depth of one metre below the surface, he found an accumulation of eggshell fragments (weighing altogether more than 11 kg) arranged into small groups, each of which apparently corresponded to an egg. The whole accumulation was interpreted as a nest.

According to the geological map, the egg-bearing red beds were Pontian in age, overlying fluvial sands. Choumowitch noted that similar

Psammornis eggshell fragments occurred at other localities in the area. Other records from Tunisia (Metlaoui, Gabès) were listed by Dughi and Sirugue [

8] on the basis of information provided by Gobert.

More details about the geology of the localities were sent to Dughi and Sirugue by Gobert and published by them [

8,

9]. He mentioned that within the Pontian red marls, the eggshell fragments were concentrated in a well-defined zone about 50 cm in thickness, containing abundant helicid gastropods and calcareous concretions, which were interpreted as having formed around grass roots. The egg-bearing deposit was considered a paleosol formed in a dry steppe environment.

The observations made by Choumowitch and Gobert thus indicate that at Chebket Safra, the Psammornis eggshells were found in situ, and not reworked.

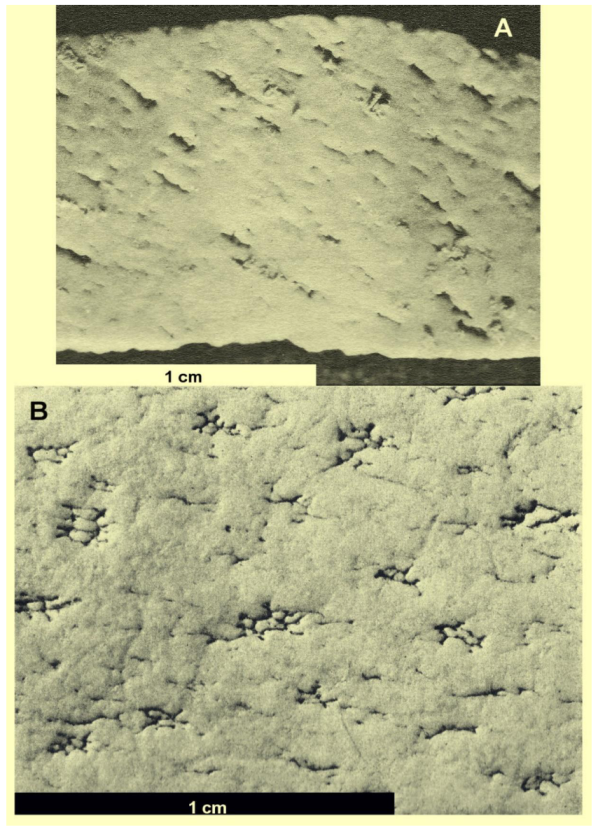

Dughi and Sirugue [

8,

9] gave detailed descriptions of the morphology and microstructure of the eggshells from Chebket Safra (

Figure 3A). They had no hesitation about attributing the Tunisian specimens to

Psammornis rothschildi. However, they noted that Andrews’ description of the pores and canals of the

Psammornis eggshell had to be significantly modified. This raises the question of whether the Tunisian specimens can really be attributed to

Psammornis rothschildi. The comparison between Andrews’ material from Algeria and the Tunisian fragments is made difficult by the fact that the former have suffered aeolian abrasion so that their surface features are somewhat obscured [

1]. On the basis of the type material from Touggourt, Andrews [

1], and especially Sauer [

5], emphasised the similarities between the eggshells of

Struthio and

Psammornis. Dughi and Sirugue [

8], mainly on the basis of the Tunisian specimens, came to a somewhat different conclusion, viz. that

Psammornis was more closely related to Rheiformes and Dinornithiformes. In a later paper [

9], they found similarities with Aepyornithiformes, Rheiformes, Casuariformes and Dinornithiformes, rather than with ostriches. A detailed comparison between eggshell fragments from Chebket Safra and the type material of

Psammornis rothschildi from Touggourt would be useful to check whether they can really be attributed to the same ootaxon.

By contrast with the various specimens from Algeria, which lack a stratigraphic context, the eggshells from Chebket Safra are of considerable importance concerning the geological age of Psammornis. However, the age attributions proposed at the time of the discovery need to be discussed in light of current knowledge.

On the basis of previous work in the area, notably that of Solignac [

39], Choumowitch attributed the fossil-bearing red beds to the Pontian. The Pontian is a local stage for the Peri-Tethyan regions around the Black Sea corresponding to deposits close to the Miocene–Pliocene boundary. According to Rybkina and Rostovtseva [

40], the Pontian of the Black Sea area can be correlated with the Messinian Salinity Crisis of the upper part of the Messinian stage (latest Miocene). However, correlations of the so-called Pontian of south-western Tunisia with the standard stratigraphic scale is not obvious. Moreover, the red beds of the Chebket Safra lack useful biostratigraphic markers. The abundant helicid gastropods they contain, in particular

Helix (

Leucochroa)

tissoti, were once considered valuable stratigraphic indicators for a Pontian age in North Africa [

38,

41]. However, this has been doubted [

42].

The lithostratigraphic characteristics and the abundant helicid gastropods lead to the consideration that the

Psammornis-bearing red beds belong to the Segui Formation. This is in agreement with the Metlaoui sheet of the geological map of Tunisia at 1/100,000 [

43], which shows a great development of this formation (attributed to the Pliocene) SW of Moularès, in the area of the Chebket Safra. Although Robinson and Wiman [

42] described the Segui Formation as a temporal enigma, its stratigraphic position is relatively clear. As early as 1910, Roux and Douvillé [

41] placed the red clays containing

Helix tissoti in the upper part of the Miocene series and observed that they overlie white and yellow sands yielding mammal remains. This sandy formation is now called the Beglia Formation and two fossiliferous levels within it have yielded a rich vertebrate assemblage indicative of an age close to the middle–late Miocene boundary ([

44] and references therein). The Beglia Formation has yielded skeletal remains of an ostrich [

45],

Struthio sp., which is not larger than the living

Struthio camelus, and therefore, unlikely to have produced the very large

Psammornis eggs. The Segui Formation, which in the Moularès region directly overlies the Beglia Formation, was considered Messinian to Pliocene [

46], or Mio-Pliocene to Villafranchian [

47]. In her reviews of Miocene formations in Tunisia, Mannai-Tayech [

48,

49] suggested a late Tortonian–early Messinian age for the Segui Formation. Mannai-Tayech’s lithological description of the Segui Formation suggests that the level with

Psammornis eggshells is in the upper part of the formation. It is worth noting that Robinson and Wiman [

42] mentioned the occurrence of gypsum deposits in the Segui Formation as possible evidence for contemporaneity with the Messinian salinity crisis.

Although some uncertainties remain about the age of the upper boundary of the Segui Formation, the above-mentioned evidence strongly suggests a late Miocene, possibly Messinian age, for the Psammornis eggshells from the Chebket Safra.

It is worth noting that in 1952, Arambourg [

50] mentioned that, according to Gobert,

Psammornis eggshell fragments were relatively frequent in continental deposits, probably Pontian in age, in southern Tunisia. However, he did not cite Choumowitch’s paper and seems to have been unaware of it (or possibly Choumowitch’s paper was published after Arambourg wrote his paper). Vickers-Rich [

10] noted Arambourg’s mention of

Psammornis in southern Tunisia, but she was unaware of Choumowitch’s and Dughi and Sirugue’s papers, so she could not appreciate the real significance of the Tunisian finds.

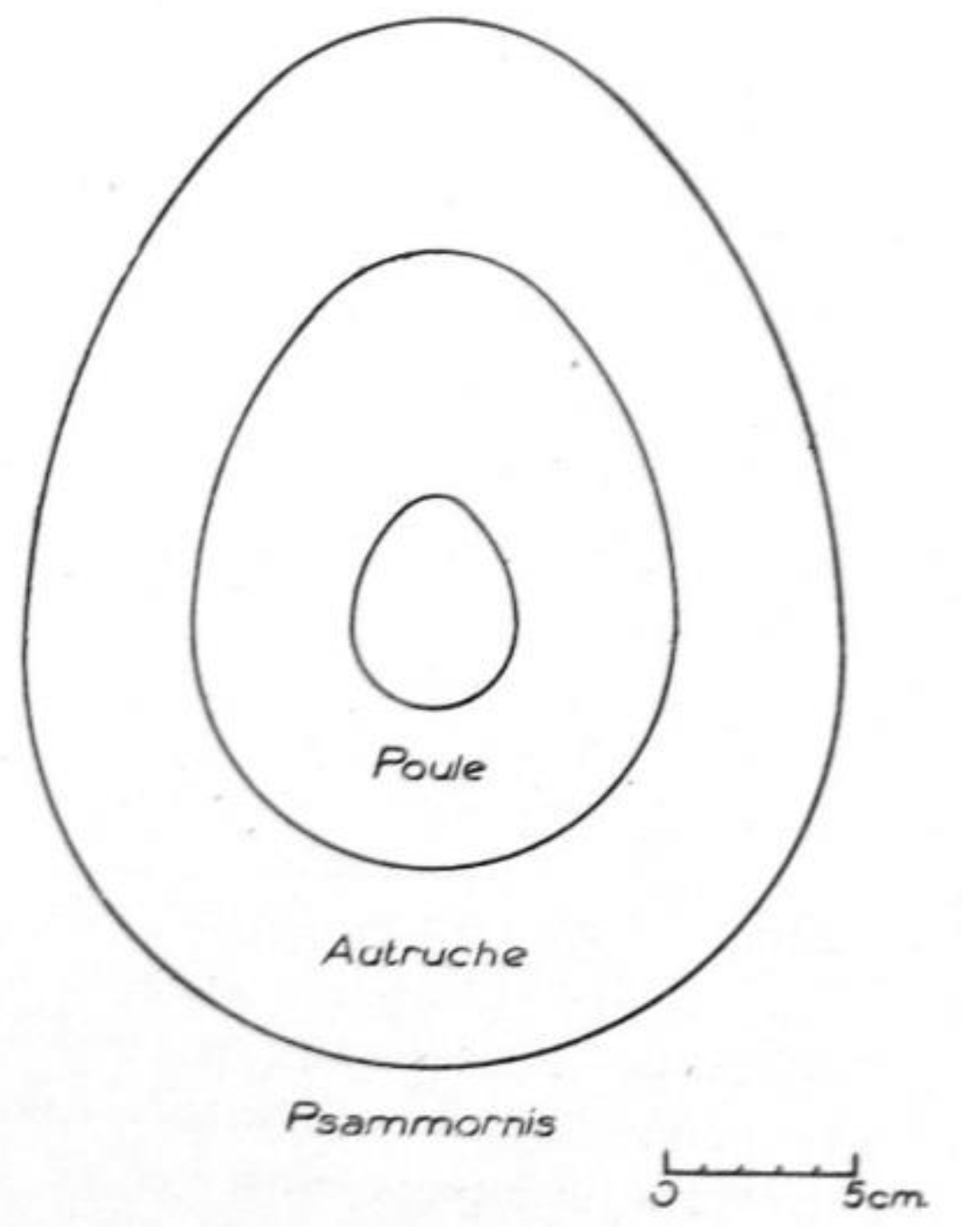

7. Psammornis from Mauritania: A Pleistocene Record

In 1939, Monod [

51] was the first to report the occurrence of

Psammornis on the Atlantic coast of Mauritania in a semi-popular short paper on eggshell fragments he had discovered at the “root” of the Cap Blanc (Râs Nouâdibhou) peninsula, in the northwestern corner of the country. The specimens were communicated to Schönwetter, who noted that they were 3 to 3,4 mm thick, and provided estimates for the dimensions of the complete shell (28 × 21 cm) and the weight of the egg (7 kg)—all of these figures being much larger than those for the living ostrich (as expressed by a comparative drawing). Monod gave no information about the geological provenance of the eggshell fragments but jokingly mentioned the omelets and water containers the Neolithic people of the Sahara could have made with such eggs, showing that he thought that they were of a comparatively recent date. In a more formal paper, including a better comparative drawing (

Figure 4), Monod [

52] quoted Schönwetter again; the German oologist had no doubt that the fragments belonged to

Psammornis rothschildi, the thickness being the same, although he remarked that the disposition of the pores was not exactly similar.

The geological provenance of the Mauritanian

Psammornis was made clear in 1971, when Tessier et al. [

53] showed that the eggshells came from Aguerguerian deposits (the Aguerguerian is a local stage of the Pleistocene). They were found in calcareous and clayey sandstones, which, as in Tunisia, also yielded helicid gastropods. Seven localities (see map in [

9]) were mentioned where

Psammornis eggshell fragments were found in situ, with sharp, unworn edges (unlike the surface-collected specimens showing clear signs of aeolian erosion). Voisin [

54] described the surface features (

Figure 3B) and microstructure of eggshells collected by Hébrard at three Mauritanian localities, noting that they were extremely abundant at one of them, which seemed to correspond to a nesting site. She found a complete correspondence with

Psammornis rothschildi and noted great similarities with ostrich eggs in the surface features of the shell. No association with human artefacts was noted. Dughi and Sirugue [

9] also gave a description of Mauritanian eggshells, which they attributed to

Psammornis, noting a certain variability in the eggshell surface.

Figure 3.

Pores on the outer surface of

Psammornis eggshell fragments from Tunisia, (

A) modified after Dughi and Sirugue [

8]) and Mauritanaia (

B), modified after Voisin [

54].

Figure 3.

Pores on the outer surface of

Psammornis eggshell fragments from Tunisia, (

A) modified after Dughi and Sirugue [

8]) and Mauritanaia (

B), modified after Voisin [

54].

Figure 4.

Outline reconstruction of a

Psammornis egg by Monod on the basis of Schönwetter’s size estimates, with outlines of the eggs of an ostich and a hen for comparison. After Monod [

51].

Figure 4.

Outline reconstruction of a

Psammornis egg by Monod on the basis of Schönwetter’s size estimates, with outlines of the eggs of an ostich and a hen for comparison. After Monod [

51].

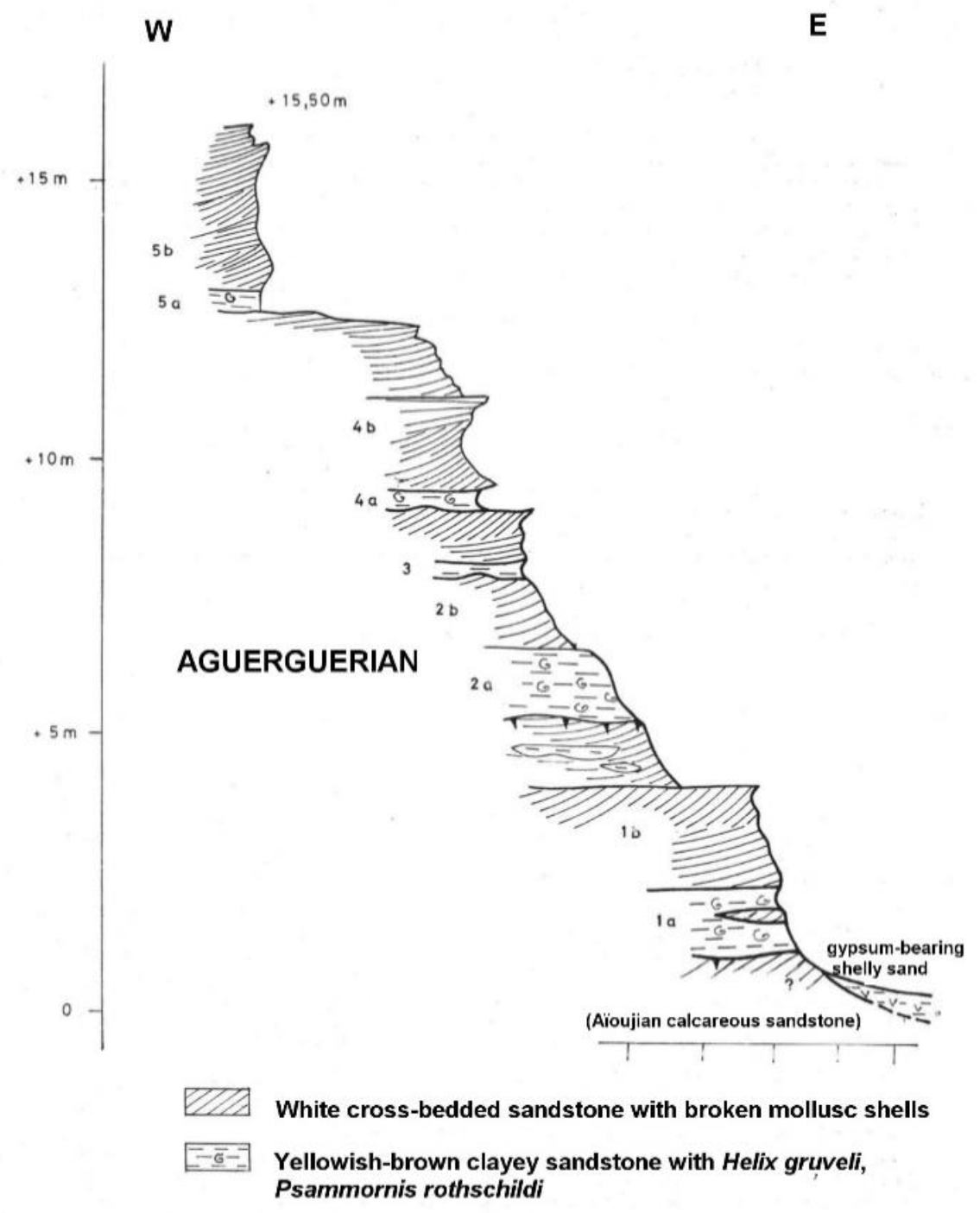

The specimens from Mauritania, like those from the Chebket Safra, are of especial importance because they were found in situ in a stratigraphic context, and therefore, provide evidence about the geological age of

Psammornis. As noted by Tessier et al. [

53], Ortlieb [

55] and Hébrard [

56], they occur in the Aguerguer sandstones, attributed to the Aguerguerian stage. A section of one of the localities was published by Hébrard [

56] (

Figure 5). As noted by Hébrard et al., [

57], the Aguerguerian is, in fact, a regressive facies of the Middle Pleistocene Aioujian stage, and the clayey sandstones containing helicid gastropods and

Psammornis correspond to paleosols.

Although the Aguerguerian has long been considered as Middle Pleistocene, its exact age remained uncertain until radiometric dates became available. C14 ages of more than 39,900 years were obtained for

Psammornis eggshell fragments [

55], but this was a minimum age. Giresse et al. [

58] published U/Th dates from fossil mollusc shells from geological formations corresponding to several Pleistocene local stages along the Mauritanian coast. No ages were provided for the Aguerguerian; however, ages ranging from 241,000 to 258,000 years were obtained for the underlying Aioujian, and of up to 111,000 years for the overlying Inchirian. Since the Aguerguerian is considered a facies of the Aioujian, an age of about 200,000 years seems likely (Middle Pleistocene, Chibanian). As noted by Hébrard [

56],

Psammornis does not occur in the Inchirian deposits.

It is worth noting that engraved ostrich eggshells and ostrich eggshell beads are found in some abundance at prehistoric (Epipalaeolithic and Neolithic) sites in Mauritania [

59]. Vernet et al. [

59] mentioned that at the Cansado prehistoric site, many

Psammornis eggshell fragments were collected in addition to fragments of

Struthio camelus eggs; they noted that

Psammornis had disappeared well before the occupation of the site by humans. More generally, there does not seem to be any record of the use of

Psammornis eggs (for ornamentation or other purposes) by prehistoric humans, in Mauritania (R. Vernet, pers. com.) or elsewhere. Nevertheless, the presence of

Psammornis eggs in the Middle Pleistocene Aguerguerian deposits of coastal Mauritania implies that this giant bird must have been contemporaneous with early humans, even though no early Palaeolithic industries have been found in Aïoujian and Aguerguerian sediments [

56,

60]. This absence may possibly be linked to unfavourable climatic conditions, since the Aguerguerian climate appears to show an evolution towards greater aridity [

56,

61].

8. The Stratigraphic Record of Psammornis and its Implications

(1) Most reported occurrences of Psammornis lack a reliable stratigraphic control. This applies to all records from the Algerian Sahara, including the type material from Touggourt. They correspond to surface finds, often in a sand dune environment, and the geological origin of the fragments could not be ascertained. This also applies to finds from Saudi Arabia (which may belong to Psammornis) and Iran (unlikely to be Psammornis in view of the thinness of the shell).

(2) The attribution to

Psammornis of various eggshell fragments is dubious. This applies mainly to fragments which are significantly thinner than the original specimens from Touggourt and do not seem to be much thicker than normal

Struthio camelus eggshells. A case in point is the material of “

Psammornis libycus” from Libya which, in all likelihood, can be attributed to

Struthio. As pointed out by Dughi and Sirugue [

8], the unusual thickness of

Psammornis eggshells was one of the main defining characteristics used by Andrews [

1] to establish the taxon

Psammornis rothschildi. However, among thick eggshells, differences in the pore system have been noted. This is reflected by the divergences between the interpretations of Andrews [

1], Sauer [

5] and Voisin [

54], who find great similarities between

Psammornis and

Struthio, and that of Dughi and Sirugue [

8,

9], who conclude that

Psammornis is related to Rheiformes, Casuariformes, Aepyornithiformes and Dinornithiformes. A revision of the material from Chebket Safra, on which Dughi and Sirugue’s conclusions were largely based, would help to clarify the question.

(3) Only two groups of localities seem to provide reliable stratigraphic evidence concerning the geological age of Psammornis:

- −

The Segui Formation of south-western Tunisia, where Psammornis ‘nests’ have been discovered in situ in red sandy clays apparently containing paleosols. Although some uncertainties remain, the likeliest age for the Segui Formation seems to be latest Miocene (about 6 My ago);

- −

The Aguerguerian of the Mauritanian coast, especially in its northern part, where what are apparently Psammornis nesting sites have been discovered in situ in sandstone formations showing evidence of paleosols. The Aguerguerian is placed in the Middle Pleistocene and may be about 200,000 years old.

These two relatively well dated

Psammornis records are rather far apart in time, implying that, if the specimens from Chebket Safra do belong to this oogenus,

Psammornis was present in North Africa over a long time span, covering at least 6 million years. This in itself is not unlikely for a genus of giant bird. The genus

Struthio has a record extending from the Early Miocene (

S. coppensi) to the present. It seems less likely that the Miocene and Pleistocene specimens of

Psammornis should belong to a single species (

P. rothschildi). It should be remembered, however, that

Psammornis is an ootaxon, the evolution of which probably cannot be followed over time with the same precision as that of taxa based on skeletal material. In fact, the distribution of

Psammornis eggshells mainly shows that very large ratite birds were present in North Africa over a fairly long period of time, from the Late Miocene to the Middle Pleistocene. There is no consensus about the systematic position of these birds, although the idea that they may have been related to the Aepyornithiformes of Madagascar has never been well-supported. Dughi and Sirugue [

8,

9], on the basis of microstructural characteristics, suggested relationships with rheas and moas. However, following Sauer’s revision [

5], most authors [

3,

10,

11,

62] seem to agree that

Psammornis was closely related to

Struthio—if not, in fact, a member of that genus—and this would lead to the possible consideration of

Psammornis as a junior synonym of the oogenus

Struthiolithus. Further research is needed to decide whether the specimens from Chebket Safra can, indeed, safely be referred to

Psammornis.

It may be worth noting that both in Tunisia and in Mauritania the deposits that yield

Psammornis eggshells apparently show signs of aridity. The giant ostrich may have been adapted to dry environments, and this may, in turn, explain its large size. Size increase in the Australian dromornithids has been interpreted as an adaptation to an increasingly arid environment with decreasing food resources [

63,

64], and a similar process has been proposed for some of the giant ostriches of Eurasia [

65].

(4) When

Psammornis became extinct remains uncertain. The Mauritanian record indicates that it survived until the Middle Pleistocene, roughly 200,000 years ago; this implies that it was contemporaneous with early humans, although evidence of interactions between hominins and these giant birds has never been reported. Attributions of

Psammornis to the Holocene (e.g., [

4]) are not supported by the available evidence. A point worth noting, as mentioned above, is that apparently no engraved or otherwise transformed (for instance for bead-making)

Psammornis eggshells have been reported, whereas decorated, cut or perforated

Struthio eggshells are very common at Epipalaeolithic and Neolithic sites in North Africa [

66,

67]. This strongly suggests that

Psammornis was no longer in existence when these cultures flourished in the Late Pleistocene and Holocene.

(5) Although very few

Psammornis localities are well dated, the available reliable ages are important in terms of the evolution of giant ratites in North Africa. It should of course be borne in mind that ootaxa are more difficult to interpret in terms of evolutionary history than skeletal remains, and that no reliable association between

Psammornis-type eggshells and fossil bones has been reported. Large ostriches have been reported on the basis of skeletal material from North Africa. They include

Struthio barbarus, from the ‘Villafranchian’ (early Pleistocene) of Algeria [

68], which is not associated with egg remains. At Ahl al Oughlam (late Pliocene or earliest Pleistocene of Morocco), a few bones of a large ostrich have been erroneously [

3] assigned to

Struthio asiaticus by Moure-Chauviré and Geraads [

69]; they are accompanied by eggshell fragments described as being different from

Psammornis. As long as no clear association between skeletal remains and

Psammornis eggs is reported, it will remain difficult to interpret the

Psammornis record in evolutionary terms. However, the stratigraphic evidence yielded by the Tunisian and Mauritanian records leads us to question some assumptions. For instance, Mikhailov and Zelenkov [

3] assumed that

Psammornis rothschildi is late Early Pleistocene to Middle Pleistocene in age and suggested that the

Psammornis lineage evolved in more northern territories (perhaps from

Struthio chersonensis from eastern Europe) and then dispersed to North Africa. However, if they actually belong to

Psammornis, the latest Miocene specimens from Tunisia are not in agreement with this hypothesis. They indicate the presence in North Africa of a giant ostrich at a much earlier date and may even suggest an African origin for the large ostriches of late Neogene Europe, although the direction of dispersal remains uncertain. The whole picture is made even more complicated by the struthionid record from southern and eastern Africa, consisting of both bone and egg remains (but apparently not including

Psammornis-type eggs), which is beyond the scope of the present paper and has led to speculations about the evolutionary history of the ostriches [

70].