Abstract

Knowledge of lichenicolous fungi is limited at a worldwide level and needs further basic information, as in the case of Central and Southern Europe. The literature sources for “Revised checklist of the Hungarian lichen-forming and lichenicolous fungi” by Lőkös and Farkas in 2009 contained 54 lichenicolous and other microfungi species of 38 genera. Due to recent field studies and microscopic work, the number of known species has increased to 104 lichenicolous species in 64 genera during the last decade, including 53 new species for the country. Old records of five species were confirmed by new collections. Key characteristics of some of the most interesting species are illustrated by microscopic views and two distribution maps are provided. Recent biodiversity estimates suggest that the number of currently known species could be 1.5 (–2) times higher with more detailed work on field collections. Although lichenicolous fungi have been less well studied in Hungary in the past, the relative diversity of lichenicolous fungi there, as indicated by Zhurbenko’s lichenicolous index, was found to be slightly higher than the mean value calculated for the world.

1. Introduction

The symbiosis of lichenized fungi in the strict sense consists of one fungal (mycobiont) and one photosynthetic (photobiont) partner [1]. However, a series of close associations are known, where further lichen associated symbionts accompany these two compulsory components [2,3,4]. One or two additional photosynthetic partners occur typically in cephalodia, which are morphologically more or less well-defined special region on the thallus surface or inside the thallus; the number of partners may therefore reach even four in this way. However, if the number of fungi is increased by one or more additional species, the number of partners can similarly be three (a tripartite symbiotic relationship) or more. These additional fungi are the lichen-inhabiting or lichenicolous fungi. There is also the special case of the four-membered symbiotic relations, where a lichenized fungus lives together with another lichenized fungus, forming a miniature ecosystem. Today, due to the wide range of developed systems in microscopy, microbiology, and molecular genetics, the nature of this ecosystem can be extended further when coexisting bacteria [3] and basidiomycete yeasts [4] are considered. This interpretation of mini-ecosystems was proposed by [5] and extended by others [6,7,8,9], focusing on lichen-associated animals such as mites, snails, and slugs.

Lichenicolous fungi are generally very small and inconspicuous, since their major part is often hidden inside the lichen thallus and only the appearance of their fruiting bodies indicates their presence; therefore, they often remain unnoticed by collectors [10]. Lichenicolous fungi are usually studied by lichen specialists and not by mycologists working on free-living fungi, since the former, when visiting the field, notice the unusual morphological characters or fruit-bodies produced by the additional fungus and frequently collect a specimen. In recent decades, numerous lichenologists–mycologists have mostly concentrated on lichenicolous fungi, whilst maintaining their interest in lichenized fungi. Other groups of microfungi are studied almost exclusively by lichenologists, such as the so-called lichen-attached microfungi, namely the non-lichenized fungi living together with lichens in the same community and habitat, most often saprophytically on decaying wood or on various rocks. While this special group of fungi represents a considerable morphological and, consequently, taxonomic diversity, their molecular genetic study is still very far from complete, since a series of technical problems arises in connection with the small size, symbiotic nature, and difficulties with isolating them. Therefore, except for exceptional pioneer studies [11,12,13,14,15], several taxa have not been analyzed phylogenetically, and in particular, local taxonomic problems have not been solved.

In addition to the morphological and taxonomic diversity, lichenologists usually differentiate between parasitic, commensalistic, and saprophytic lifestyles among lichenicolous fungi [2,10,16,17,18,19].

Knowledge of lichenicolous fungi is limited at a worldwide level and needs further basic information, as in the case of Central and Southern Europe [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. In the revised checklist of Hungary [28], the lichen-forming and lichenicolous (and other lichen-related) taxa were separated, since our knowledge on lichens was much more advanced than that of lichenicolous taxa; the latter were mainly treated by literature sources, while lichens were studied in more detail from the literature, herbarium material, and in the field. The list was based primarily on Magyarország mikroszkopikus gombáinak határozókönyve 1–3 (identification book of Hungarian microscopic fungi) by J. Bánhegyi et al. [29,30,31] and, further, 26 literature sources. In all, 54 lichenicolous and other lichen-related species of 38 genera were listed from Hungary in 2009.

The present aim is to update our knowledge of the lichenicolous taxa in Hungary and compile a separate list of these species, which can be regularly updated. Our extended fieldwork over the last decade has confirmed several former literature records, added new occurrences of numerous species, and provided new distributional data for various regions of Hungary. Based on these records, the diversity of these fungi is considered from various points of view (geographic distribution, host, systematics) in the checklist below.

2. Materials and Methods

New collections were identified with the help of various literature sources [10,32,33,34]. The morphology and anatomy were studied by means of a NIKON Eclipse/NiU (DIC, epifluorescence) compound microscope (Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), Nikon SMZ18 stereo microscope (Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), and Olympus SZX9 and Olympus BX50 (DIC) microscopes (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Micrographs were prepared by Olympus E450 camera (with Quick Photo Camera 2.3 software; Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) and Nikon DS-Fi1c and Fi3 camera (with NIS-Elements BR ML software; Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) with the indicated microscopes. Microscopic examinations were carried out in water, where it was necessary in 10% KOH (K) (Reanal, Budapest, Hungary), Lugol’s iodine (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany), directly (I) or after 10% KOH pre-treatment (K/I).

The nomenclature mainly follows the IndexFungorum [35], similarly to the previous checklist [28], but the work by Lawrey and Diederich 2018 [36], several chapters by Paul Diederich in [33], and other literature sources by Hawksworth, Kocourková, and Santesson et al. [18,32,37,38] were also employed. The nomenclatures of old literature data were checked repeatedly and revised. Information on the host is generally based on specimens collected in Hungary. In the case of literature records, we could only rely on the original text available.

Specimens are deposited in herbaria BP, CBFS, DE, EGR, M, SZE, UPS, VBI, and W—abbreviations follow [39].

Distribution maps were constructed by the computer program for geographical information system QGIS 3.18.2 ‘Zürich’, released in 2020, applying an adaptation of the Central European grid system [40,41]; the symbols (dots) represent units of c. 5 km × 6 km areas.

3. Results

The following checklist contains 104 species; a nomenclatural revision of the taxa treated by Lőkös and Farkas in 2009 [28] and identification of specimens recently collected mostly by N. Varga throughout Hungary. In total, 53 lichenicolous fungi have been confirmed as new to the country, and old records of five species have been confirmed by new collections. Host lichen species are named wherever possible, and geographical distribution is provided according to the main regions within the country. Anatomical and morphological annotations refer to the specimens collected in Hungary in some cases, especially if they differ in some respects from the known description.

List of Lichenicolous Fungi

New species for Hungary are indicated by an asterisk (*).

- Abrothallus bertianus De Not., G. bot. ital. 2(1.1): 192 (1846)

Host: Melanohalea elegantula

Reported by P. Czarnota et al. [42] from the Bükk Mts (Cserépfalu, Bükk National Park), the only known locality in Hungary.

- 2.

- Abrothallus caerulescens I. Kotte, Centbl. Bakt. ParasitKde, Abt. II 24: 86 (1909)

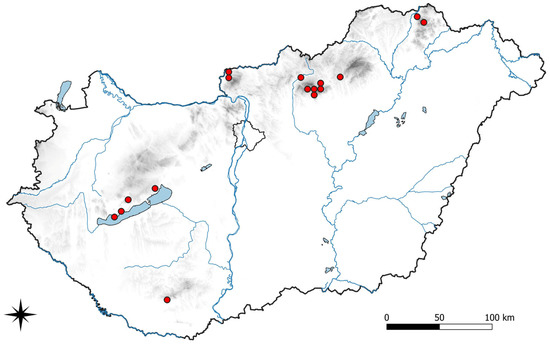

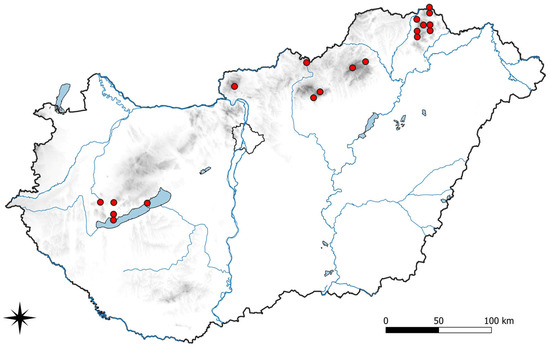

Figure 1.

Distribution of Abrothallus caerulescens in Hungary.

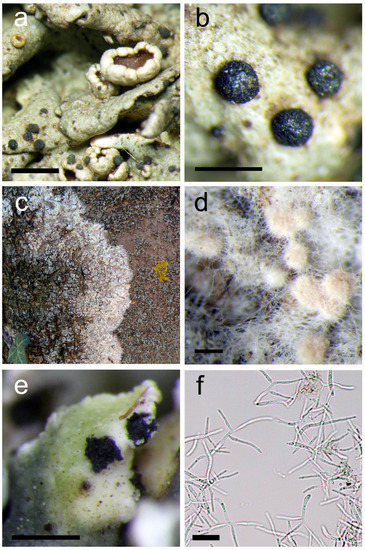

Figure 2.

(a,b) Abrothallus caerulescens, apothecia on the thallus of Xanthoparmelia stenophylla (scales 1 mm; 500 µm); (c) Athelia arachnoidea, mycelia on epiphytic Phaeophyscia and Physcia spp.; (d) developing young sclerotia of Athelia arachnoidea (scale 200 µm); (e) Cladoniicola staurospora, brown conidiomata in the host thallus (scale 500 µm); (f) H-shaped conidia with diverging arms of Cladoniicola staurospora (scale 200 µm).

Hosts: Xanthoparmelia conspersa, X. stenophylla, X. tinctina

First recorded as A. berterianus and as A. parmeliarum by A. Kiszely-Vámosi [43] from the Mátra Mts in 1980. Not rare in Hungary, it occurs at several localities in mountainous areas, i.e., in the Northern Mountain Range (Börzsöny, Mátra and Zemplén Mts), in the Balaton Upland [44], and in the Mecsek Mts (BP 97037; BP 97038).

Note: Former specimens identified as A. tulasnei have also been included here.

- 3.

- *Abrothallus cladoniae R. Sant. & D. Hawksw., in Hawksworth, Notes R. bot. Gdn Edinb. 46(3): 392 (1990)

Host: Cladonia sp.

Recorded from the Zemplén Mts at Telkibánya (BP 97001), the only known locality in Hungary.

- 4.

- *Abrothallus microspermus Tul., Ann. Sci. Nat., Bot., sér. 3 17: 115 (1852)

Host: Flavoparmelia caperata

Observed as an anamorphic stage, Vouauxiomyces truncatus on the thallus of Flavoparmelia caperata. Recently recorded from the Zala Hills at Zalacsány and the Zemplén Mts at Telkibánya in Hungary (BP 97002; BP 97003).

- 5.

- Abrothallus parmeliarum (Sommerf.) Arnold, Flora, Regensburg 57: 102 (1874)

Host: Hypogymnia physodes

Only one old literature record as Abrothallus smithii, without voucher specimen, by F. Hazslinszky in 1859 [30,45] from the Zemplén Mts (near Kékedfürdő).

- 6.

- *Abrothallus prodiens (Harm.) Diederich & Hafellner, in Diederich, Mycotaxon 37: 300 (1990)

Host: Hypogymnia physodes

Recorded from only one locality in the Balaton Upland (Kővágóörs) (BP 97004).

- 7.

- Abrothallus suecicus (Kirschst.) Nordin, Svensk bot. Tidskr. 58: 226 (1964)

Hosts: Ramalina spp.

The old literature source [30] mentions this species with possible hosts but without exact locality and voucher specimens; therefore, it must be regarded as a dubious record.

- 8.

- Aposphaeria cladoniae Allesch. & Schnabl, in Allescher, Ber. bayer. bot. Ges. 4: 32 (1895)

Host: Cladonia sp.

Reported from Cladonia pyxidata var. neglecta f. lophyra on a sandy grassland area near Kecskemét (Nyír) by L. Hollós in 1913 [30,46]. No recent occurrence is known.

- 9.

- Arthonia varians (Davies) Nyl., Lich. Scand. (Helsinki): 260 (1861)

Host: Lecanora rupicola

An old record as Celidium varians from the Visegrád Mts (near Dobogókő) was published by G. Moesz in 1942 [30,47,48], but the cited voucher specimen (together with the host Lecanora sordida) collected by G. Timkó is not available.

- 10.

- Athelia arachnoidea (Berk.) Jülich, Willdenowia, Beih. 7: 53 (1972)

(Figure 2c,d)

Hosts: various lichens (e.g., Candelariella reflexa, Parmelia sulcata, Phaeophyscia orbicularis, Physcia adscendens, Ph. stellaris, Ph. tenella, Xanthoria parietina), mosses, bark, and leaf litter

Widespread throughout Hungary [44,49,50,51,52,53]; frequent in anthropogenic environment (parks, gardens, roadside trees, agricultural areas, etc.). In most cases it is sterile; the spreading mycelia without hymenium, basidia, or basidiospores, only the creamy-to-brownish sclerotia, can be observed.

- 11.

- Bilimbia killiasii (Hepp) H. Olivier, Bull. Acad. Intern. Géogr. Bot. 15: 213 (1905)

Host: Peltigera sp.

In addition to an old, dubious literature record as Mycobilimbia killiasii without exact locality and voucher specimens [30], it has also been collected recently in a sandy area in the Nyírség (near Hajdúhadház) from Peltigera sp. (BP 97005).

- 12.

- Bryostigma apotheciorum (A. Massal.) S. Y. Kondr. & Hur, in Kondratyuk et al., Acta bot. hung. 62(1–2): 99 (2020)

Host: Protoparmeliopsis muralis s. lat.

It was reported as Conida clemens on Placodium saxicolum from the Bükk Mts (near Eger) by F. Hazslinszky in 1870 [54].

- 13.

- *Bryostigma parietinarium (Hafellner & A. Fleischhacker) S. Y. Kondr. and Hur, in Kondratyuk et al., Acta bot. hung. 62(1–2): 100 (2020)

Host: Xanthoria parietina

Recorded from several localities in Hungary, mainly from lowland areas: Kiskunság, Little Hungarian Plain, Nyírség, Őrség. It often grows together with other xanthoriicolous species.

- 14.

- *Bryostigma phaeophysciae (Grube & Matzer) S. Y. Kondr. and Hur, in Kondratyuk et al., Acta bot. hung. 62(1–2): 100 (2020)

Host: Phaeophyscia orbicularis

Known from several localities in Hungary, abundant from lowlands to mountains, and spreading.

- 15.

- Burgoa angulosa Diederich, Lawrey, and Etayo, in Diederich and Lawrey, Mycol. Progr. 6(2): 66 (2007)

Host: Bacidina sp.

Reported from only one locality, Zemplén Mts (Füzér), by P. Diederich and J. D. Lawrey in 2007 [55].

- 16.

- *Capronia suijae Tsurykau & Etayo, Lichenologist 49(1): 2 (2017)

Host: Xanthoria parietina

This species, described in 2017, was detected soon after from the Kiskunság sandy area (Bugac) (BP 97050).

- 17.

- Cercidospora epipolytropa (Mudd) Arnold, Flora, Regensburg 57(10): 154 (1874)

Hosts: Lecanora spp.

An old record, without exact locality and voucher specimens, was recorded by J. Bánhegyi et al. in 1985 [30]. It is regarded as common species in Hungary.

- 18.

- Cercidospora macrospora (Uloth) Hafellner & Nav.-Ros., Lichen Flora of the Greater Sonoran Desert Region (Tempe) 2: 638 (2004)

Hosts: Lecanora spp., Protoparmeliopsis muralis

Although there is only one literature record, as C. ulothii, without exact locality and voucher specimens [30], it has recently been recorded from the Balaton Upland on Protoparmeliopsis muralis (at Tihany) (VBI 5747) and is probably a common species in Hungary.

- 19.

- Chaenothecopsis pusilla (Ach.) A. F. W. Schmidt, Mitt. Staatsinst. Allg. Bot. Hamburg 13: 148 (1970)

Host: –

Reported from several localities [56,57,58,59], i.e., the Bükk Mts at Miskolc-Tapolca [54,60,61], the Great Hungarian Plain at Kecskemét-Nyír [46], and the Somogy Hills at Balatonlelle [62]. Although all old specimens and additional recent collections from the Bükk Mts (near Jávorkút) and from the Somogy Hills (near Ropoly) are from decaying wood, its lichenicolous occurrence is also expected in Hungary.

- 20.

- Chaenothecopsis pusiola (Ach.) Vain., Acta Soc. Fauna Flora Fenn. 57 (no. 1): 70 (1927)

Host: –

Known only from decaying wood in the Visegrád Mts at Dömös, as Calicium floerkei f. polycephalum [57,58,59,63]; however, its lichenicolous occurrence is also expected in Hungary.

- 21.

- Chaenothecopsis savonica (Räsänen) Tibell, Beih. Nova Hedwigia 79: 666 (1984)

Host: –

The only Hungarian record from an Alnus glutinosa fen near Dabas in the Great Hungarian Plain was recorded by G. Thor in 1988 [64] (UPS, VBI). Its lichenicolous occurrence should be confirmed.

- 22.

- Chaenothecopsis subparoica (Nyl.) Tibell, in Tibell and Ryman, Nova Hedwigia 60(1–2): 215 (1995)

Host: Haematomma ochroleucum

Recorded as Calicium subparoicum, from only one locality in the Mátra Mts (Disznó-kő) by A. Kiszely-Vámosi in 1980 [43].

- 23.

- *Cladoniicola staurospora Diederich, van den Boom, & Aptroot, Belg. J. Bot. 134(2): 128 (2001)

(Figure 2e,f)

Host: Cladonia chlorophaea aggr.

Recently recorded from the Zemplén Mts (near Füzérkomlós) (BP 97006); the only Hungarian record.

- 24.

- *Clypeococcum hypocenomycis D. Hawksw., Notes R. bot. Gdn Edinb. 38(1): 167 (1980)

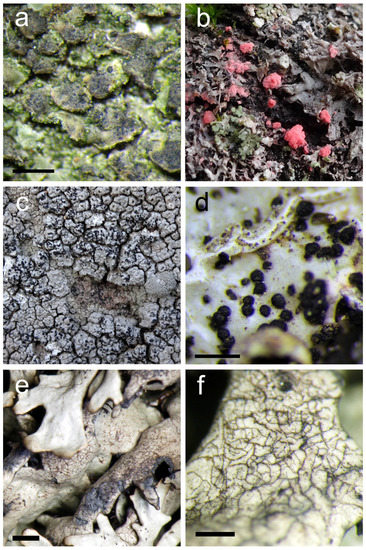

(Figure 3a)

Figure 3.

(a) Clypeococcum hypocenomycis, perithecia in the thallus of Hypocenomyce scalaris (scale 500 µm); (b) pink sporodochia of Illosporiopsis christiansenii on Physcia adscendens; (c) Karschia talcophila on Diploschistes scruposus; (d) Lichenopuccinia poeltii on Parmelia sulcata (scale 500 µm); (e,f) Lichenostigma cosmopolites on Xanthoparmelia sp. (scales 1 mm; 500 µm).

Host: Hypocenomyce scalaris

Known from several old and recent localities (e.g., Börzsöny, Villány and Zemplén Mts); it appears to be widespread and frequent in Hungary.

- 25.

- Corticifraga fuckelii (Rehm) D. Hawksw. and R. Sant., Bibl. Lichenol. 38: 125 (1990)

Host: Peltigera sp.

Reported from Hungary by D. Hawksworth and R. Santesson in 1990 [65] without exact locality and voucher specimens.

- 26.

- *Didymocyrtis cladoniicola (Diederich, Kocourk. & Etayo) Ertz & Diederich, in Ertz et al., Fungal Diversity 74: 67 (2015)

Hosts: Cladonia foliacea, Cl. pyxidata s. lat.

Known in the Great Hungarian Plain from several sandy grassland locations, as well as from the Zemplén Mts (BP 97008; BP 97009).

- 27.

- *Didymocyrtis epiphyscia Ertz & Diederich, in Ertz et al., Fungal Diversity 74: 71 (2015)

Host: Oxneria fallax

Known only from a recent collection from the Mátra Mts (BP 97007).

- 28.

- *Didymocyrtis foliaceiphila (Diederich, Kocourk. & Etayo) Ertz & Diederich, in Ertz et al., Fungal Diversity 74: 73 (2015)

Host: Cladonia foliacea

Known only from a sandy grassland area from the Kiskunság (BP 97010).

- 29.

- *Didymocyrtis slaptonensis (D. Hawksw.) Hafellner & Ertz, in Ertz et al., Fungal Diversity 74: 80 (2015)

Host: Xanthoria parietina

Not rare in Hungary, being known from recent collections from the Buda and Bükk Mts, the Little Hungarian Plain, and from the Zala Hills (BP 97013; BP 97014; BP 97015; BP 97016).

- 30.

- *Epicladonia sandstedei D. Hawksw., Bull. Br. Mus. nat. Hist., Bot. 9(1): 16 (1981)

Host: Cladonia chlorophaea aggr.

Recorded recently from the Zemplén Mts (Füzérkomlós) (BP 97035).

Note: It induces galls on the basal squamules as well as on the scypi of the host thalli. Most of the measured conidia are simple, not septate (cf. [66]).

- 31.

- *Epithamnolia xanthoriae (Brackel) Diederich & Suija, Mycologia 109(6): 896 (2017)

Host: Xanthoria parietina

Only recorded from the Bakony Mts near Bakonybél (Bakony Natural History Museum, Zirc).

- 32.

- Erythricium aurantiacum (Lasch) D. Hawksw. & A. Henrici, Field Mycology 16(1): 16 (2015) (=Marchandiomyces a.)

Host: Physcia adscendens

Only recently reported [53], but it seems to be frequent in Hungary.

- 33.

- Halosporademinuta (Arnold) Tomas. & Cif., Archo. bot. ital. 28: 11 (1952) (=Merismatium deminutum)

Hosts: on various crustose lichens

Reported, as Polyblastia deminuta, from the Bükk Mts (Mályinka: Bartus-kő) by A. Kiszely-Vámosi et al. in 1989 [56,67], its only Hungarian locality.

- 34.

- Hanseniaspora osmophila (Niehaus) Phaff, M. W. Mill. & Shifrine, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 22: 147 (1956)

Host: –

Old, dubious literature record without host, exact locality, and voucher specimens [29].

- 35.

- *Heterocephalacria bachmannii (Diederich and M. S. Christ.) Millanes & Wedin, in Liu et al., Stud. Mycol. 81: 120 (2015)

Host: Cladonia furcata

Recently found in sandy areas of the Great Hungarian Plain (Kiskunság, Tatárszentgyörgy) (BP 97017). Probably more frequent in Hungary but overlooked.

- 36.

- *Heterocephalacria physciacearum (Diederich) Millanes & Wedin, in Liu et al., Stud. Mycol. 81: 120 (2015)

Hosts: Physcia adscendens, Ph. tenella

Recently collected in the Őrség National Park (Vendvidék) in the western part of Hungary (BP 97051; BP 97052).

Note: Tremelloid galls have been found on many host specimens in recent collections from Hungary. According to recent studies [11,68,69], tremelloid species can be distinguished mostly by molecular genetic methods. In the lack of basidia and/or basidiospores, the presence of these taxa could not be confirmed [70].

- 37.

- Illosporiopsis christiansenii (B. L. Brady & D. Hawksw.) D. Hawksw., in Sikaroodi et al., Mycol. Res. 105(4): 457 (2001)

(Figure 3b)

Host: Physcia adscendens

Recorded from the Visegrád Mts by E. Farkas in 1990 [49] and from the Soroksár Botanical Garden (Budapest) by N. Varga et al. in 2016 [53], but it seems to be widespread and common in Hungary.

- 38.

- *Illosporium roseum Mart., Fl. crypt. erlang. (Nürnberg): 325 (1817)

Host: Peltigera sp.

Reported, as Illosporium carneum, from a recent collection from the Villány Mts (Csarnóta) (VBI 5746).

- 39.

- *Intralichen christiansenii (D. Hawksw.) D. Hawksw. & M. S. Cole, Fungal Diversity 11: 90 (2002)

Host: Xanthoria parietina

Recognized only recently from the Great Hungarian Plain near Hajós (BP 97018) but could be widespread and overlooked.

- 40.

- *Karschia talcophila (Ach.) Körb., Parerga lichenol. (Breslau) 5: 460 (1865)

(Figure 3c)

Host: Diploschistes scruposus

Recently detected in the Börzsöny and the Mátra Mts but thought to be more frequent in Hungary (BP 97019; BP 97020).

- 41.

- *Lichenochora obscuroides (Linds.) Triebel & Rambold, Bibl. Lichenol. 48: 168 (1992)

Host: Phaeophyscia orbicularis

Recently found on bark of Populus sp. near Hajós in the Great Hungarian Plain and in the Bükk Mts (Szarvaskő) (BP 97011; BP 97012).

- 42.

- Lichenoconium erodens M. S. Christ. & D. Hawksw., in Hawksworth, Persoonia 9(2): 174 (1977)

Hosts: Hypogymnia physodes, Lecanora conizaeoides, Parmelia sulcata

It is known in Hungary from several localities, from the Northern Mountain Range and the Little Hungarian Plain, as well as the Soroksár Botanical Garden (Budapest) [53]; a frequent parasite causing bleached lesions surrounded by a black margin.

- 43.

- Lichenoconium lecanorae (Jaap) D. Hawksw., Bull. Br. Mus. nat. Hist., Bot. 6(3): 270 (1979)

Hosts: Parmelia sulcata, Squamarina lentigera

It occurs in the Balaton Upland region (Tihany) [66,71] and, more recently, in the Great Hungarian Plain (Tiszalúc) on Parmelia sulcata (BP 97021).

Note: Similar to L. erodens and maybe more frequent in the country.

- 44.

- *Lichenoconium pyxidatae (Oudem.) Petr. & Syd., Feddes Repert., Beih. 42: 135 (1927)

Host: Cladonia pyxidata s. lat.

Found in various habitats at several localities in Hungary.

- 45.

- *Lichenoconium usneae (Anzi) D. Hawksw., Persoonia 9(2): 185 (1977)

Hosts: Cladonia furcata, Xanthoparmelia conspersa

Recognized from recent collections from the Mecsek Mts (BP 97041) and the Mátra Mts (BP 97042); found only on the apothecia of Xanthoparmelia conspersa.

- 46.

- *Lichenoconium xanthoriae M. S. Christ., Friesia 5(3–5): 212 (1956)

Host: Xanthoria parietina

Known from several localities mainly in the lowland areas.

- 47.

- *Lichenodiplis lecanorae (Vouaux) Dyko & D. Hawksw., in Hawksworth and Dyko, Lichenologist 11(1): 52 (1979)

Host: Lecanora sp.

Known from the Great Hungarian Plain (near Hajós) (BP 97022); the only locality in Hungary.

- 48.

- Lichenopeltella cetrariicola (Nyl.) R. Sant., Nordic J. Bot. 9(1): 99 (1989)

Host: Cetraria islandica

Recorded without exact locality and voucher specimens [30]. Its host species is rare in Hungary. An old herbarium specimen infected by Lichenopeltella cetrariicola has been found recently (BP 83751); however, it also lacks an exact locality.

- 49.

- *Lichenopuccinia poeltii D. Hawksw. & Hafellner, in Hawksworth, Beih. Nova Hedwigia 79: 374 (1984)

(Figure 3d)

Host: Parmelia sulcata

Known only from the Aggtelek Karst (BP 97024) in Hungary.

- 50.

- Lichenostigma cosmopolites Hafellner & Calat., Mycotaxon 72: 108 (1999)

(Figure 3e,f)

Hosts: Xanthoparmelia conspersa, X. mougeotii, X. protomatrae, X. pulvinaris, X. stenophylla, X. tinctina

Widespread and abundant throughout Hungary on various Xanthoparmelia species from lowlands to mountains; recently recorded from the Zemplén Mts by G. Matus et al. [72].

- 51.

- Lichenostigma elongatum Nav.-Ros. & Hafellner, Mycotaxon 57: 213 (1996)

Host: Lobothallia radiosa

Only known in Hungary from Dédesvár near Mályinka (Bükk National Park) in the Bükk Mts [73,74] (CBFS JV4377).

- 52.

- *Lichenostigma rouxii Nav.-Ros., Calat. & Hafellner, in Calatayud et al., Mycol. Res. 106(10): 1237 (2002)

Host: Squamarina cartilaginea

Probably unpublished, old record from the Bükk Mts (Mályinka: Buzgó-kő) (M). Its occurrence is awaits confirmation from recent collections.

- 53.

- *Lichenothelia rugosa (G. Thor) Ertz & Diederich, Fungal Diversity 66: 135 (2014)

Host: Diploschistes scruposus

Probably unpublished record from the Zemplén Mts (Füzér: Castle Hill) (M).

- 54.

- Lichenozyma pisutiana Černajová & Škaloud, Fungal Biology 123(9): 634 (2019)

Hosts: Cladonia rangiformis, C. rei

An endolichenic yeast, known from culture. Its Hungarian distribution is represented by two localities, one in the Balaton Upland (Tihany) and the other in the Vértes Mts (Csákberény) [75].

- 55.

- Marchandiomyces corallinus (Roberge) Diederich & D. Hawksw., in Diederich, Mycotaxon 37: 312 (1990)

(Figure 4a)

Figure 4.

(a) Pinkish conidiomata of Marchandiomyces corallinus on Parmelia saxatilis (scale 500 µm); (b) Penttilamyces lichenicola on Cladonia foliacea (scale 500 µm); (c) aggregated perithecia of Stigmidium eucline on Varicellaria lactea (scale 500 µm); (d) Stigmidium tabacinae on Thalloidima sp. (scale 500 µm); (e) Telogalla olivieri forming galls on Xanthoria parietina (scale 500 µm); (f) Xanthoria parietina infected by Xanthoriicola physciae, resulting in black spots on apothecia.

Host: Parmelia saxatilis

First published by E. Farkas et al. [44] from the Balaton Upland (Szentbékkálla: Fekete-hegy) and the Zemplén Mts (BP 94422; BP 97025; VBI). It seems to be widespread in Hungary.

- 56.

- Melaspilea leciographoides Vouaux, Bull. Soc. mycol. Fr. 29: 472 (1913)

Hosts: Verrucaria spp.

An old literature record, as Mycomelaspilea leciographoides, mentioned without exact locality and voucher specimens but with possible hosts [30].

- 57.

- *Microcalicium disseminatum (Ach.) Vain., Acta Soc. Fauna Flora fenn. 57(no. 1): 77 (1927)

Host: –

Recognized from an old collection from the Bükk Mts (BP 63433, BP 85066) from decaying oak wood. Its presence on thalli of other calicioid lichen needs confirmation.

- 58.

- *Monodictys epilepraria Kukwa & Diederich, Lichenologist 37(3): 217 (2005)

Host: Lepraria lobificans

Detected recently from a few localities (e.g., BP 97046).

- 59.

- *Muellerella hospitans Stizenb., Nova Acta Acad. Caes. Leop.-Carol. German. Nat. Cur. 30(no. 3): 51 (1863)

Hosts: Bacidia fraxinea, B. rubella

Frequently occurs on Bacidia spp. (e.g., BP 97053 on mixed hosts), but no published records.

- 60.

- *Muellerella lichenicola (Sommerf.) D. Hawksw., Bot. Notiser 132(3): 289 (1979)

Host: Xanthoria parietina

Recognized recently from the Kiskunság sandy area (Bugac); further occurrences have also been detected (BP 97049).

- 61.

- Neolamya peltigerae (Mont.) Theiss. & Syd., Ann. Mycol. 16(1–2): 29 (1918)

Host: Peltigera didactyla

Known in Hungary from one locality in the Bükk Mts (Szarvaskő: Pyrker-sziklák) (BP 50825) [76].

- 62.

- Opegrapha rupestris Pers., Ann. Bot. (Usteri) 5: 20 (1794)

Hosts: Bagliettoa spp., Verrucaria calciseda

This parasitic Opegrapha species is represented by several specimens named Opegrapha persoonii from the Aggtelek Karst and the Bükk Mts [56].

- 63.

- *Penttilamyces lichenicola (Thorn, Malloch & Ginns) Zmitr., Kalinovskaya & Myasnikov, Folia Cryptog. Petropol. (St.-Peterburg) 7: 8 (2019)

(Figure 4b)

Host: Cladonia foliacea

Known only from a recent collection from the Great Hungarian Plain (Kiskunság) (BP 97036).

- 64.

- Plectocarpon lichenum (Sommerf.) D. Hawksw., in Hawksworth and Galloway, Lichenologist 16(1): 86 (1984) (=Celidium lichenum)

Host: Lobaria pulmonaria

Reported from one locality in the Visegrád Mts (Dömös: Keserűs-hegy) [77]. No further Plectocarpon specimens were found after checking all available Hungarian Lobaria pulmonaria specimens deposited in Hungarian collections. Since the host has become a rare lichen species in Hungary, future occurrences of this lichenicolous fungus are doubtful.

- 65.

- *Pleospora xanthoriae Khodos. & Darmostuk, Opusc. Philolich. 15: 8 (2016)

Host: Xanthoria parietina

The only Hungarian locality is in the Great Hungarian Plain (Bugac) (BP 97000); however, since the host species is very frequent in Hungary, further occurrences are expected.

- 66.

- Polycoccum marmoratum (Kremp.) D. Hawksw., in Hawksworth et al., Lichenologist 12(1): 107 (1980) (=Microthelia marmorata)

Host: Polyblastia sp.

Known from the Aggtelek Karst and the Bükk Mts [78], as well as the Villány Mts [56].

- 67.

- Polycoccum microsticticum (Leight.) Arnold, Ber. bayer. bot. Ges. 1(Anhang): 132 (1891) (=Didymosphaeria microstictica)

Hosts: Acarospora smaragdula, Acarospora sp.

Reported from the Visegrád Mts (Dömös: Vadálló kövek) by G. Moesz in 1942 [47,48] and from a recent collection from the Zemplén Mts (BP 97048).

- 68.

- *Polycoccum pulvinatum (Eitner) R. Sant., Lichens and Lichenicolous Fungi of Sweden and Norway (Lund): 175 (1993)

Host: Physcia caesia

Known only from two localities in Hungary, from the Mátra Mts (Kékes) (EGR, as P. galligenum), and from the Visegrád Mts (Tahi: Ábrahám-bükk) (VBI 5748, as P. galligenum).

- 69.

- Pronectria robergei (Mont. & Desm.) Lowen, Mycotaxon 39: 462 (1990)

Hosts: Peltigera spp.

Old, dubious literature record, as Nectriella robergei, without exact locality and voucher specimens but with possible hosts [29].

Note: Its anamorph is Illosporium roseum.

- 70.

- Punctelia oxyspora (Tul.) Divakar, A. Crespo & Lumbsch, in Divakar et al., Fungal Diversity 84: 114 (2017) (=Nesolechia oxyspora)

Host: Parmelia sp.

An old literature record without exact locality and voucher specimens [30].

- 71.

- Pyrenochaeta xanthoriae Diederich, Mycotaxon 37: 318 (1990)

Host: Xanthoria parietina

Only its locality from the Balaton Upland (Szigliget, Bozóti-legelő) has been recently published (BP 96097) [51], but it is not rare in Hungary, as several other localities are known.

- 72.

- Rhagadostoma lichenicola (De Not.) Keissl., Rabenh. Krypt.-Fl., Edn 2 (Leipzig) 8: 320 (1930)

Host: Solorina crocea

An old, dubious literature record [29]. The host, an alpine species, does not occur in Hungary.

- 73.

- Rhizocarpon advenulum (Leight.) Hafellner & Poelt, Herzogia 4(1–2): 10 (1976)

Hosts: Pertusaria spp.

An old, dubious literature record, as Karschia advenula, without exact locality and voucher specimens, but mentioning possible hosts [30].

- 74.

- *Roselliniella cladoniae (Anzi) Matzer & Hafellner, Bibl. Lichenol. 37: 59 (1990)

Hosts: Cladonia furcata, C. pyxidata agg.

Known only from several localities in the Kiskunság and the Balaton Upland (Mt Tamás-hegy) (e.g., BP 97026; BP 97027).

- 75.

- Sarcopyrenia gibba (Nyl.) Nyl., Mém. Soc. Acad. Maine Loire 4: 69 (1858)

Hosts: Candelariella aurella, Lecanora dispersa, Rinodina bischoffii, Verrucaria nigrescens, etc.

Reported from several localities from natural as well as anthropogenic habitats throughout the country [79].

- 76.

- *Sclerococcum epicladonia Zhurb., in Zhurbenko and Pino-Bodas, Opusc. Philolich. 16: 235 (2017)

Host: Cladonia chlorophaea

Reported from the Zemplén Mts (Fövenyes) (BP 97028).

- 77.

- *Sclerococcum lobariellum (Nyl.) Ertz & Diederich, in Diederich et al., Bryologist 121(3): 398 (2018)

Host: Lobaria pulmonaria

Its only Hungarian locality in the Visegrád Mts (Pilisszentlélek: Hoffmann-kunyhó) has been recently recognized from an old collection (BP 81558).

Notes: Black apothecia with true margin grow on the host thallus; hypothecium darkens after K/I; asci contain eight ascospores; ascospores ornamented granularly, 12–14 × 4.8–6.4 µm.

- 78.

- Sclerococcum parasiticum (Flörke) Ertz & Diederich, in Diederich et al., Bryologist 121(3): 399 (2018)

Hosts: Pertusaria spp.

An old, dubious literature record, as Leciographa inspersa, without exact locality and voucher specimens, but mentioning possible hosts [30].

- 79.

- Sclerococcum parellarium (Nyl.) Ertz and Diederich, in Diederich et al., Bryologist 121(3): 399 (2018)

Hosts: Lecidea spp.

An old, dubious literature record, as Leciographa parellaria, without exact locality and voucher specimens, but mentioning possible hosts [30].

- 80.

- Scutula epiblastematica (Wallr.) Rehm, Rabenh. Krypt.-Fl., Edn 2 (Leipzig) 1.3(lief. 32): 322 (1890) (1896)

Host: Peltigera canina

Known only from the Vértes Mts (near Csákvár) in Hungary from old collections, as Hollósia vertesensis (BP 33899) [76,80].

- 81.

- *Scutula tuberculosa (Th. Fr.) Rehm, in Saccardo and Saccardo, Syll. fung. (Abellini) 18: 174 (1906)

Host: Solorina saccata

Recently recognized from a recent collection from the Vértes Mts (BP 92218).

- 82.

- *Sphinctrina leucopoda Nyl., Flora, Regensburg 42: 44 (1859)

Host: Diploschistes scruposus

Recognized from a recent collection from the Zemplén Mts (Holló-kő) (BP 97034).

- 83.

- *Sphinctrina tubaeformis A. Massal., Memor. Lich.: 155 (1853)

Host: Lecanora sp.

Only one old specimen has been confirmed from the Bükk Mts (Bükkszenterzsébet, Orosz-kút) (BP 63587; further recent collections are necessary.

- 84.

- Sphinctrina turbinata Fr., Syst. orb. veg. (Lundae) 1: 121 (1825)

Host: Pertusaria pertusa

Known from old collections, as Sphinctrina gelasinata, from several localities in the Bükk Mts and from one locality in the Somogy Hills [56,57,58,81]. Recent occurrences from other regions are also expected.

- 85.

- *Spirographa lichenicola (D. Hawksw. & B. Sutton) Flakus, Etayo and Miądl., in Flakus et al., Plant and Fungal Systematics 64(2): 328 (2019)

Hosts: Hypogymnia physodes, Lecanora conizaeoides

Recently recorded from an abandoned orchard in the Northern Mountain Range (Gömörszőlős: Szőlőhegy) (BP 97029).

Notes: Asexual stage on the host thallus forms discolored areas surrounded by a distinct black margin. Pycnidia in groups, immersed in the thallus, conidia Y-shaped with cellular forks, 8.0–8.5 × 1.6 µm. Associated with Lichenoconium erodens.

- 86.

- Stigmidium congestum (Körb.) Triebel, Mycotaxon 42: 290 (1991)

Host: Lecanora campestris

Its only Hungarian locality from the Bükk Mts (near Eger) was recorded as Pharcidia congesta by F. Hazslinszky in 1884 [61].

- 87.

- *Stigmidium eucline (Nyl.) Vězda, Česká Mykol. 24(4): 228 (1970)

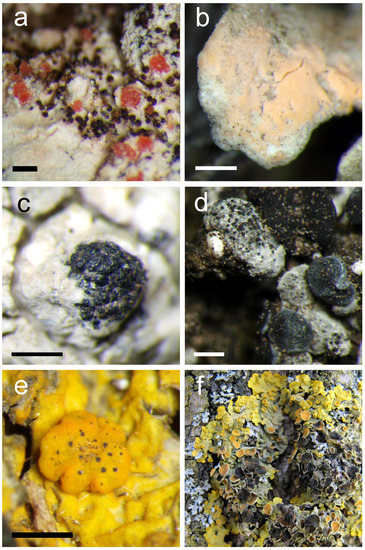

Figure 5.

Distribution of Stigmidium eucline in Hungary.

Host: Varicellaria lactea

Recognized from old and recent collections (Börzsöny, Bükk, Mátra, Zemplén Mts, etc.).

- 88.

- *Stigmidium microspilum (Körb.) D. Hawksw., Kew Bull. 30(1): 201 (1975)

Host: Graphis scripta

Recently found in the Somogy Hills (at Zselickisfalud) (BP 97030).

- 89.

- *Stigmidium pumilum (Lettau) Matzer & Hafellner, Bibl. Lichenol. 37: 115 (1990)

Host: Physcia caesia

Known from the Börzsöny Mts from a recent collection (BP 97045).

- 90.

- Stigmidium rouxianum Calat. & Triebel, Lichenologist 35(2): 109 (2003)

Host: Acarospora cervina

Known only from the Bükk Mts (Dédestapolcsány: Dédes-vár) (CBFS JV4407) [74].

- 91.

- *Stigmidium solorinarium (Vain.) D. Hawksw., Lichenologist 15(1): 14 (1983)

Host: Solorina saccata

Several localities have been reported from the Bakony and Vértes Mts.

Notes: Ascospores 10–16 × 3.2–4.8 µm, apex pointed in overmature stage; number of septa variable, 1–3.

- 92.

- *Stigmidium squamariae (B. de Lesd.) Cl. Roux & Triebel, Bull. Soc. linn. Provence 45: 511 (1994)

Host: Protoparmeliopsis muralis s. lat.

Known only from several localities in the Little Hungarian Plain (e.g., BP 97043, BP 97044).

- 93.

- *Stigmidium tabacinae (Arnold) Triebel, Bibl. Lichenol. 35: 236 (1989)

(Figure 4d)

Hosts: Thalloidima opuntioides, Th. sedifolium

Widely distributed and common in Hungary in rocky grassland habitats.

- 94.

- *Stigmidium xanthoparmeliarum Hafellner, Bull. Soc. linn. Provence 44: 231 (1994)

Host: Xanthoparmelia stenophylla

Known only from sseveral localities in the Balaton Upland and the Börzsöny Mts (e.g., BP 97039, BP 97040).

- 95.

- *Syspastospora cladoniae Etayo, Cryptog. Mycol. 29(1): 88 (2008)

Host: Cladonia pyxidata s. lat.

Collected from only one location in the Great Hungarian Plain, in a sand dune near Fülöpháza, in the shadow of Juniperus communis (BP 97031).

- 96.

- *Taeniolella phaeophysciae D. Hawksw., Bull. Br. Mus. nat. Hist., Bot. 6(3): 255 (1979)

Host: Phaeophyscia orbicularis

Recently found in the Great Hungarian Plain on bark of Sambucus nigra near Hajós (BP 97032). Probably a frequent species, similar to its host, but very few records are available to date.

- 97.

- *Talpapellis beschiana (Diederich) Zhurb., U. Braun, Diederich and Heuchert, in Heuchert et al., Fungal Syst. Evol. 2: 231 (2018)

Host: Cladonia chlorophaea aggr.

Recognized from a recent collection from the Zemplén Mts (BP 97047).

- 98.

- *Telogalla olivieri (Vouaux) Nik. Hoffm. & Hafellner, Bibl. Lichenol. 77: 109 (2000)

(Figure 4e)

Host: Xanthoria parietina

Regarded as a common and widely distributed species in Hungary.

- 99.

- Tetramelas phaeophysciae A. Nordin & Tibell, Lichenologist 37(6): 495 (2005)

Hosts: Parmelia spp.

An old, dubious literature record, as Karschia pulverulenta, without exact locality and voucher specimens, but with possible hosts [30].

- 100.

- Tetramelas pulverulentus (Anzi) A. Nordin & Tibell, Lichenologist 37(6): 497 (2005)

Hosts: Parmelia spp.

An old, dubious literature record, as Karschia pulverulenta, without exact locality and voucher specimens, but mentioning possible hosts [30].

- 101.

- *Thelocarpon epibolum Nyl., Not. Sällsk. Fauna et Fl. Fenn. Förh., Ny Ser. 8: 188 (1866)

Host: Solorina saccata

It has been recognized from recent collections from the Vértes Mts (BP 92218).

- 102.

- *Vouauxiella lichenicola (Linds.) Petr. & Syd., Feddes Repert., Beih. 42: 484 (1927)

Host: Lecanora cf. chlarotera

Recorded from a recent collection from the Balaton Upland (Ódörögd) (BP 97033).

- 103.

- Xanthoriicola physciae (Kalchbr.) D. Hawksw., in Hawksworth and Punithalingam, Trans. Br. mycol. Soc. 61(1): 67 (1973) (=Coniosporium physciae)

(Figure 4f)

Host: Xanthoria parietina

Widely distributed and common throughout Hungary wherever Xanthoria parietina is present [30,46,51,52,53,82,83].

- 104.

- Zwackhiomyces immersae (Arnold) Grube & Triebel, in Grube and Hafellner, Nova Hedwigia 51(3–4): 318 (1990)

Host: Clauzadea monticola

Recently published from a collection made by H. Lojka in 1880 near Lipótmező in the Buda Mts (W0088943) [84].

4. Discussion

The 104 listed species represent a relatively good level of diversity compared to data of various European countries and the mean value of the world calculated according to the lichenicolous index (LI) [85], previously adopted for the Bulgarian lichenicolous fungi [20]; updated LI values for several other countries are provided in Table 1, the value for lichenicolous fungi in Hungary being just above the mean value for the world. There are countries or regions that reach more than twice the average value for the world (e.g., Bavaria (Germany), Great Britain, Belgium), but countries such as Fennoscandia, Ukraine, and France, which have more humid oceanic and/or Mediterranean climates or a more diverse landscape and habitats or a larger altitudinal range, and thereby would be expected to be important for lichens and lichenicolous fungi, have values not much higher than that of Hungary.

Table 1.

Lichenicolous index values worldwide and in selected European countries, USA, and Canada, and the numbers of species the calculation based on.

Since lichenicolous species belong to a large number of higher taxa (64 genera, 43 families, and 33 orders), they represent a rather high systematic diversity. The most species-rich genera are Stigmidium with nine, Abrothallus with seven, and Didymocyrtis with four, while 49 genera contain only one species.

Lichenicolous fungi are found on c. 80 host species in Hungary, which is a relatively low number compared to the total number of lichens (926). This suggests that lichenicolous fungi might be discovered on further host species in the future, even if not all lichen species are known as hosts of lichenicolous fungi. It is not known why some lichens are found more frequently with lichenicolous fungi, while others are usually without; the effect of lichen secondary metabolites might be a possible explanation [7]. We can also assume that the knowledge of lichenicolous fungi is far from complete globally, and a great number of new taxa are to be described. According to a recent estimate, only c. 3–8% of the world’s fungi is known [103].

Additional fieldwork may result in a more detailed knowledge of the distribution of taxa with the possibility for preparing distribution maps for the known species similarly to the current examples, Abrothallus caerulescens (Figure 1) and Stigmidium eucline (Figure 5). Further floristical novelties for Hungary are expected by detailed investigations of the frequent host species in the genera Xanthoria, Phaeophyscia, Physcia, and Lecanora, as well as the understudied genera such as Anaptychia, Pseudevernia, Ramalina and Usnea.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.F. and N.V.; methodology, E.F., L.L. and N.V.; investigation, E.F., L.L. and N.V.; resources, E.F., L.L. and N.V.; data curation, L.L. and N.V.; writing—original draft preparation, E.F. and N.V.; writing—review and editing, E.F. and L.L.; visualization, E.F., L.L. and N.V.; supervision, E.F.; project administration, E.F.; funding acquisition, E.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The first version of the checklist was compiled by the support of the Hungarian Scientific Research Fund, grant number OTKA T047160; it was continuously updated by the same foundation, grant number OTKA 81232. Currently, our work is supported by the National Research Development and Innovation Fund, grant number NKFI K 124341.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The following public databases were used: IndexFungorum (http://www.indexfungorum.org/, accessed on 27 September 2021); Index Herbariorum (http://sweetgum.nybg.org/science/ih/, accessed on 27 September 2021); Lawrey, J.D.; Diederich, P. (2008), Lichenicolous fungi (http://www.lichenicolous.net, accessed on 27 September 2021); MycoBank (https://www.mycobank.org/, accessed on 27 September 2021); Recent literature on lichens (http://nhm2.uio.no/botanisk/lav/RLL/RLL.HTM, accessed on 27 September 2021).

Acknowledgments

We express our special thanks to M.R.D. Seaward (Bradford University, UK) for his advice and revision of the English text and to V. O’Neil (Tampa, USA) for linguistic reading. We are indebted to the curators of herbaria (especially CBFS, DE, EGR, M, SZE, UPS, and W) for specimen information, and to colleagues A.R. Burgaz, J. Csiky, S.Y. Kondratyuk, G. Matus, K. Molnár, and M. Sinigla for their help and company during fieldwork.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Hawksworth, D.L.; Honegger, R. The lichen thallus: A symbiotic phenotype of nutritionally specialized fungi and its response to gall producers. In Plant Galls. Organisms, Interactions, Populations; The Systematics Association Special Volume; Williams, M.A.J., Ed.; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1994; pp. 77–98. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrey, J.D.; Diederich, P. Lichenicolous fungi: Interactions, evolution, and biodiversity. Bryologist 2003, 106, 81–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschenbrenner, I.A.; Cernava, T.; Berg, G.; Grube, M. Understanding microbial multi-species symbioses. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spribille, T.; Tuovinen, V.; Resl, P.; Vanderpool, D.; Wolinski, H.; Aime, M.C.; Schneider, K.; Stabentheiner, E.; Toome-Heller, M.; Thor, G.; et al. Basidiomycete yeasts in the cortex of ascomycete macrolichens. Science 2016, 353, 488–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrar, J.F. The lichen as an ecosystem: Observation and experiment. In Lichenology: Progress and Problems; Brown, D.H., Hawksworth, D.L., Bailey, R.H., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 1976; pp. 385–406. [Google Scholar]

- Biazrov, L.G.; Melekhina, E.N. Oribatid mites in lichen consortiums in north Scandinavia. Bjulleten’ Mosk. Obs. Ispyt. Prir. Otd. Biol. 1992, 97, 73–79. [Google Scholar]

- Asplund, J.; Bokhorst, S.; Kardol, P.; Wardle, D.A. Removal of secondary compounds increases invertebrate abundance in lichens. Fungal Ecol. 2015, 18, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asplund, J.; Gauslaa, Y.; Merinero, S. The role of fungal parasites in tri-trophic interactions involving lichens and lichen-feeding snails. New Phytol. 2016, 211, 1352–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gadea, A.; Le Lamer, A.-C.; Le Gall, S.; Jonard, C.; Ferron, S.; Catheline, D.; Ertz, D.; La Pogam, P.; Boustie, J.; Lohézic-Le Devehat, F.; et al. Intrathalline metabolite profiles in the lichen Argopsis friesiana shape gastropod grazing patterns. J. Chem. Ecol. 2018, 44, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihlen, P.G.; Wedin, M. An annotated key to the lichenicolous Ascomycota (including mitosporic morphs) of Sweden. Nova Hedwig. 2008, 86, 275–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millanes, A.M.; Diederich, P.; Ekman, S.; Wedin, M. Molecular phylogeny and character evolution in the jelly fungi (Tremellomycetes, Basidiomycota, Fungi). Mol. Phyl. Evol. 2011, 61, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suija, A.; de los Ríos, A.; Pérez-Ortega, S. A molecular reappraisal of Abrothallus species growing on lichens of the order Peltigerales. Phytotaxa 2015, 195, 201–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suija, A.; Ertz, D.; Lawrey, J.D.; Diederich, P. Multiple origin of the lichenicolous life habit in Helotiales, based on nuclear ribosomal sequences. Fungal Divers. 2015, 70, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suija, A.; Suu, A.; Lõhmus, P. Substrate specificity corresponds to distinct phylogenetic lineages: The case of Chaenotheca brunneola. Herzogia 2016, 29, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flakus, A.; Etayo, J.; Miadlikowska, J.; Lutzoni, F.; Kukwa, M.; Matura, N.; Rodriguez-Flakus, P. Biodiversity assessment of ascomycetes inhabiting Lobariella lichens in Andean cloud forests led to one new family, three new genera and 13 new species of lichenicolous fungi. Plant Fungal Syst. 2019, 64, 283–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santesson, R. The Lichens of Sweden and Norway; Swedish Museum of Natural History: Stockholm, Sweden, 1984; p. 333. [Google Scholar]

- Hawksworth, D.L. The variety of fungal-algal symbioses, their evolutionary significance, and the nature of lichens. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 1988, 96, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawksworth, D.L. The lichenicolous fungi of Great Britain and Ireland: An overview and annotated checklist. Lichenologist 2003, 35, 191–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, D.H.S. War in the world of lichens: Parasitism and symbiosis as exemplified by lichens and lichenicolous fungi. Mycol. Res. 1999, 103, 641–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivarov, V.V.; Varga, N.; Lőkös, L.; Brackel, W.v.; Ganeva, A.; Natcheva, R.; Farkas, E. Contributions to the Bulgarian lichenicolous mycota—An annotated checklist and new records. Herzogia 2021, 34, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafellner, J. Checklist and bibliography of lichenized and lichenicolous fungi so far reported from Albania (version 05-2007). Fritschiana 2007, 59, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hafellner, J. Noteworthy records of lichenicolous fungi from various countries on the Balkan Peninsula. (Nennenswerte Funde von lichenicolen Pilzen von verschiedenen Länderen auf der Balkanhalbinsel). Herzogia 2018, 31, 476–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savić, S.; Tibell, L. Checklist of the lichens of Serbia. Mycol. Balcan. 2006, 3, 187–215. [Google Scholar]

- Savić, S.; Tibell, L.; Andreev, M. New and interesting lichenized and lichenicolous fungi from Serbia. Mycol. Balcan. 2006, 3, 99–106. [Google Scholar]

- Tibell, L.; Savić, S. New and interesting lichenized and lichenicolous fungi from Tara National Park, Western Serbia. Mycol. Balcan. 2008, 5, 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hafellner, J.; Mayrhofer, H. Noteworthy records of lichenicolous fungi from various countries on the Balkan Peninsula. II. Herzogia 2020, 33, 494–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svoboda, D.; Bouda, F.; Malícek, J.; Hafellner, J. A contribution to the knowledge of lichenized and lichenicolous fungi in Albania. Herzogia 2012, 25, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lőkös, L.; Farkas, E. Revised Checklist of the Hungarian Lichen-Forming and Lichenicolous Fungi. (Magyarországi Zuzmók és Zuzmólakó Mikrogombák Revideált Fajlistája). 2009. Available online: https://ecolres.hu/Farkas.Edit (accessed on 27 September 2021).

- Bánhegyi, J.; Tóth, S.; Ubrizsy, G.; Vörös, J. Magyarország Mikroszkopikus Gombáinak Határozókönyve. 1; Akadémiai Kiadó: Budapest, Hungary, 1985; pp. 5–511. [Google Scholar]

- Bánhegyi, J.; Tóth, S.; Ubrizsy, G.; Vörös, J. Magyarország Mikroszkopikus Gombáinak Határozókönyve. 2; Akadémiai Kiadó: Budapest, Hungary, 1985; pp. 517–1152. [Google Scholar]

- Bánhegyi, J.; Tóth, S.; Ubrizsy, G.; Vörös, J. Magyarország Mikroszkopikus Gombáinak Határozókönyve. 3; Akadémiai Kiadó: Budapest, Hungary, 1987; pp. 1157–1316. [Google Scholar]

- Hawksworth, D.L. A key to lichen-forming, parasitic, parasymbiotic and saprophytic fungi occurring on lichens in the British Isles. Lichenologist 1983, 15, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, T.H., III; Ryan, B.D.; Diederich, P.; Gries, C.; Bungartz, F. (Eds.) Lichen Flora of the Greater Sonoran Desert Region; Lichens Unlimited, Arizona State University: Tempe, AZ, USA, 2004; Volume 2, p. 633. [Google Scholar]

- Zhurbenko, M.P.; Pino-Bodas, R. A revision of lichenicolous fungi growing on Cladonia, mainly from the Northern Hemisphere, with a worldwide key to the known species. Opusc. Philolich. 2017, 16, 188–266. [Google Scholar]

- IF (Index Fungorum Partnership). Available online: http://www.indexfungorum.org/ (accessed on 27 September 2021).

- Lawrey, J.D.; Diederich, P. Lichenicolous Fungi: Worldwide Checklist, Including Isolated Cultures and Sequences Available. 2018. Available online: http://www.lichenicolous.net (accessed on 27 September 2021).

- Kocourková, J. Lichenicolous fungi of the Czech Republic. Acta Mus.-Nat. Pragae Ser. B Hist. Nat. 2000, 3–4, 59–169. [Google Scholar]

- Santesson, R.; Moberg, R.; Nordin, A.; Tønsberg, T.; Vitikainen, O. Lichen-Forming and Lichenicolous Fungi of Fennoscandia; Museum of Evolution; Uppsala University: Uppsala, Sweden, 2004; p. 359. [Google Scholar]

- Thiers, B. (Continuously Updated). Index Herbariorum: A global Directory of public Herbaria and Associated Staff. New York Botanical Garden’s Virtual Herbarium. Available online: http://sweetgum.nybg.org/science/ih/ (accessed on 27 September 2021).

- Niklfeld, H. Bericht über die Kartierung der Flora Mitteleuropa. Taxon 1971, 20, 545–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borhidi, A. Role of mapping the flora of Europe in nature conservation. Norrlinia 1984, 2, 87–98. [Google Scholar]

- Czarnota, P.; Mayrhofer, H.; Bobiec, A. Noteworthy lichenized and lichenicolous fungi of open-canopy oak stands in east-central Europe. (Bemerkenswerte lichenisierte und lichenicole Pilze von lückigen Eichenbeständen in Zentral-Osteuropa). Herzogia 2018, 31, 172–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiszelyné Vámosi, A. A Mátra-hegység zuzmóflórája I. (The lichen flora of the Mátra Mountains, I). Folia Hist.-Nat. Mus. Matr. 1980, 6, 51–70. [Google Scholar]

- Farkas, E.; Lőkös, L.; Molnár, K. Zuzmók biodiverzitás-vizsgálata a szentbékkállai „Fekete-hegy” mintaterületen. (Biodiversity of lichen-forming fungi on Fekete Hill (Szentbékkálla, Hungary)). Folia Mus. Hist.-Nat. Bakony. 2013, 29, 29–46. [Google Scholar]

- Hazslinszky, F. Beiträge zur Kenntnis der Karpatenflora VIII. Flechten. Verh. Zool.-Bot. Ges. Wien 1859, 9, 7–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hollós, L. Kecskemét vidékének gombái. Math. Term. Tud. Közlem. 1913, 32, 149–235. [Google Scholar]

- Moesz, G. Budapest és Környékének Gombái; Die Pilze von Budapest und Seiner Umgebung; Királyi Magyar Természettudományi Társulat: Budapest, Hungary, 1942; p. 320. [Google Scholar]

- Tóth, S. Microscopic fungi of the Pilis and the Visegrád Mts, Hungary. Studia Bot. Hung. 1995, 25, 21–57. [Google Scholar]

- Farkas, E. Lichenológiai Vizsgálatok Budapesten és a Pilis Bioszféra Rezervátumban—Elterjedés, Bioindikáció. (Investigation of the Lichen Flora in Budapest and in the Pilis Biosphere Reservation—Distribution and Bioindication). Bachelor’s Thesis, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Vácrátót, Hungary, 1990; pp. 1–121. [Google Scholar]

- Farkas, E.; Lőkös, L. Zuzmók biodiverzitás-vizsgálata Gyűrűfű környékén. (Biodiversity studies on lichen-forming fungi at Gyűrűfű (SW Hungary)). Clusiana Mikol. Közlem. 2010, 48, 145–153. [Google Scholar]

- Farkas, E.; Lőkös, L.; Papp, B.; Sinigla, M.; Varga, N. Zuzmók és mohák biodiverzitás-vizsgálata a szigligeti Kongó-rétek mintaterületen. (Biodiversity of bryophytes, lichen-forming and lichenicolous fungi on “Kongó Meadows” (Hegymagas–Szigliget, Hungary)). Folia Mus. Hist. Nat. Bakony. 2016, 33, 19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Lőkös, L.; Varga, N.; Farkas, E. The lichen collection of András Horánszky in the Hungarian Natural History Museum. Studia Bot. Hung. 2016, 47, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Varga, N.; Lőkös, L.; Farkas, E. The lichen-forming and lichenicolous fungi of the Soroksár Botanical Garden (Szent István University, Budapest, Hungary). Studia Bot. Hung. 2016, 47, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazslinszky, F. Adatok Magyarhon zuzmóvirányához. Math. Term. Tud. Közlem. 1870, 7, 43–73. [Google Scholar]

- Diederich, P.; Lawrey, J.D. New lichenicolous, muscicolous, corticolous and lignicolous taxa of Burgoa s. l. and Marchandiomyces s. l. (anamorphic Basidiomycota), a new genus for Omphalina foliacea, and a catalogue and a key to the non-lichenized, bulbilliferous basidiomycetes. Mycol. Prog. 2007, 6, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verseghy, K. Magyarország Zuzmóflórájának Kézikönyve; The lichen flora of Hungary; Magyar Természettudományi Múzeum: Budapest, Hungary, 1994; p. 415. [Google Scholar]

- Szatala, Ö. A magyarországi Coniocarpeae-k kritikai feldolgozása. (Revisio critica Coniocarpinearum Hungariae). Ann. Mus. Nat. Hung. 1926, 24, 99–135. [Google Scholar]

- Szatala, Ö. Lichenes Hungariae. Magyarország zuzmóflórája. I. Pyrenocarpeae—Gymnocarpeae (Coniocarpineae). Folia Cryptog. 1927, 1, 337–434. [Google Scholar]

- Titov, A.N. Mikokalicievüe Gribü Golarktiki; Mycocalicioid fungi (the order Mycocaliciales) of Holarctic; KMK Scientific Press Ltd.: Moscow, Russia, 2006; 296p. [Google Scholar]

- Hazslinszky, F. Néhány adat a Bükkhegység kryptogamjai megismertetéséhez. MOT Vándorgy Munk 1869, 13, 227–229. [Google Scholar]

- Hazslinszky, F. A Magyar Birodalom Zuzmó-Flórája; The Lichen Flora of The Hungarian Empire; Királyi Magyar Természettudományi Társulat: Budapest, Hungary, 1884; p. 304. [Google Scholar]

- Sántha, L. Néhány adat Balatonlelle és környékének zuzmóflórájához. (Einige Beiträge zur Flechtenflora von Balatonlelle und seiner Umgebung). Magyar Bot. Lapok 1916, 15, 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Timkó, G. Új adatok a Budai és Szentendre–Visegrádi hegyvidék zuzmóvegetációjának ismeretéhez. (Neue Beiträge zur Kenntnis der Flechtenvegetation des Buda–Szentendre–Visegráder Gebirges). Bot. Közlem. 1926, 22, 81–104. [Google Scholar]

- Thor, G. Some lichens from Hungary. Graph. Scr. 1988, 2, 67–71. [Google Scholar]

- Hawksworth, D.L.; Santesson, R. A revision of the lichenicolous fungi previously referred to Phragmonaevia. Bibl. Lichenol. 1990, 38, 121–143. [Google Scholar]

- Hawksworth, D.L. The lichenicolous Coelomycetes. Bull. Br. Mus. Nat. Hist. Bot. 1981, 9, 1–98. [Google Scholar]

- Kiszelyné Vámosi, A.; Marschall, Z.; Orbán, S.; Suba, J. A Bükk hegység északi peremhegyeinek florisztikai és cönológiai jellemzése. Acta Acad. Paed. Agriensis 1989, 19, 135–185. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.-Z.; Wang, Q.-M.; Göker, M.; Groenewald, M.; Kachalkin, A.V.; Lumbsch, H.T.; Millanes, A.M.; Wedin, M.; Yurkov, A.M.; Boekhout, T.; et al. Towards an integrated phylogenetic classification of the Tremellomycetes. Stud. Mycol. 2015, 81, 85–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamora, J.C.; Millanes, A.M.; Wedin, M.; Rico, V.J.; Pérez-Ortega, S. Understanding lichenicolous heterobasidiomycetes: New taxa and reproductive innovations in Tremella s.l. Mycologia 2016, 108, 381–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diederich, P. The lichenicolous heterobasidiomycetes. Bibl. Lichenol. 1996, 61, 1–198. [Google Scholar]

- Hawksworth, D.L. Taxonomic and biological observations on the genus Lichenoconium (Sphaeropsidales). Persoonia 1977, 9, 159–198. [Google Scholar]

- Matus, G.; Szepesi, J.; Rózsa, P.; Lőkös, L.; Varga, N.; Farkas, E. Xanthoparmelia mougeotii (Parmeliaceae, lichenised Ascomycetes) new to the lichen flora of Hungary. Studia Bot. Hung. 2017, 48, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Vondrák, J.; Šoun, J. Lichenostigma svandae a new lichenicolous fungus on Acarospora cervina. Lichenologist 2007, 39, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vondrák, J.; Šoun, J.; Lőkös, L.; Khodosovtsev, A. Noteworthy lichen-forming and lichenicolous fungi from the Bükk Mts, Hungary. Acta Bot. Hung. 2009, 51, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Černajová, I.; Škaloud, P. The first survey of Cystobasidiomycete yeasts in the lichen genus Cladonia; with the description of Lichenozyma pisutiana gen. nov., sp. nov. Fungal Biol. 2019, 123, 625–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kőfaragó-Gyelnik, V. De fungis lichenicolentibus Hungariae historicae I. Borbásia 1939, 1, 151–155. [Google Scholar]

- Gallé, L. Flechtenterata in Herbarien zu Szeged. Acta Biol. 1972, 18, 27–41. [Google Scholar]

- Fóriss, F. Új zuzmófajok és fajváltozatok Magyarország flórájában. (Neue Flechtenarten und Varietäten in der Flora Ungarns). Bot. Közlem. 1957, 47, 67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Farkas, E.; Lőkös, L. Pyrenolichens of the Hungarian lichen flora II. Sarcopyrenia gibba (Nyl.) Nyl. new to Hungary. Acta Bot. Hung. 2003, 45, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triebel, D.; Wedin, M.; Rambold, G. The genus Scutula (lichenicolous ascomycetes, Lecanorales): Species on the Peltigera canina and P. horizontalis groups. Symb. Bot. Upsal. 1997, 32, 323–337. [Google Scholar]

- Löfgren, O.; Tibell, L. Sphinctrina in Europe. Lichenologist 1979, 11, 109–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawksworth, D.L. The lichenicolous Hyphomycetes. Bull. Br. Mus. Nat. Hist. Bot. 1979, 6, 183–300. [Google Scholar]

- Révay, Á. Review of the Hyphomycetes of Hungary. Studia Bot. Hung. 1998, 27–28, 5–74. [Google Scholar]

- Grube, M.; Hafellner, J. Studien an flechtenbewohnenden Pilzen der Sammelgattung Didymella (Ascomycetes, Dothideales). Nova Hedwig. 1990, 51, 283–360. [Google Scholar]

- Zhurbenko, M.P. Lichenicolous fungi of Russia: History and first synthesis of exploration. Micol. Phitopatol. 2007, 41, 481–486. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Brackel, W.V. Rote Liste und Gesamtartenliste der Flechten (Lichenes), Flechtenbewohnenden und Flechten Ähnlichen Pilze Bayerns; Bayerisches Landesamt für Umwelt: Augsburg, Germany, 2019; pp. 1–124. [Google Scholar]

- Coppins, B.J. Checklist of Lichens of Great Britain and Ireland; British Lichen Society: London, UK, 2002; pp. 1–87. [Google Scholar]

- Diederich, P.; Sérusiaux, E. The Lichens and Lichenicolous Fungi of Belgium and Luxembourg; Musée National d’Histoire Naturelle: Luxembourg, 2000; pp. 1–207. [Google Scholar]

- Wirth, V.; Hauck, M.; von Brackel, W.; Cezanne, R.; de Bruyn, U.; Dürhammer, O.; Eichler, M.; Gnüchtel, A.; Litterski, B.; Otte, V.; et al. Checklist of lichens and lichenicolous fungi in Germany, 2010. Version #2: 19 January 2011. Available online: http://www.gwdg.de/~mhauck (accessed on 27 September 2021).

- Brackel, W.v. Preliminary checklist of the lichenicolous fungi of Italy. Not. Soc. Lich. Ital. 2016, 29, 95–146. [Google Scholar]

- Nimis, P.L. The lichens of Italy—A Second Annotated Catalogue; EUT Edizioni Università di Trieste: Trieste, Italy, 2016; pp. 1–740. [Google Scholar]

- Roux, C.; Poumarat, S.; Monnat, J.-Y.; Van Haluwyn, C.; Gonnet, D.; Gonnet, O.; Bauvet, C.; Houmeau, J.-M.; Boissière, J.-C.; Bertrand, M.; et al. Catalogue des Lichens et Champignons Lichénicoles de France Métropolitaine, 3rd ed.; Association Française de Lichénologie (AFL): Fontainebleau, France, 2020; pp. 1–1769. [Google Scholar]

- Roux, C.; Poumarat, S.; Monnat, J.-Y.; Van Haluwyn, C.; Gonnet, D.; Gonnet, O.; Bauvet, C.; Houmeau, J.-M.; Boissière, J.-C.; Bertrand, M.; et al. Catalogue des Lichens et Champignons Lichénicoles de France Métropolitaine, 2nd ed.; Édit. Association Française de Lichénologie (AFL): Fontainebleau, France, 2017; pp. 1–1581. [Google Scholar]

- Roux, C.; Poumarat, S.; Monnat, J.-Y.; Van Haluwyn, C.; Gonnet, D.; Gonnet, O.; Bauvet, C.; Houmeau, J.-M.; Boissière, J.-C.; Bertrand, M.; et al. Catalogue des Lichens et Champignons Lichénicoles de France Métropolitaine; Édit. Des Abbayes: Fougères, France, 2014; pp. 1–1525. [Google Scholar]

- Esslinger, T.L. A cumulative checklist for the lichen-forming, lichenicolous and allied fungi of the continental United States and Canada, version 23. Opusc. Philolich. 2019, 18, 102–378. [Google Scholar]

- Kondratyuk, S.Y.; Popova, L.P.; Khodosovtsev, O.Y.; Lőkös, L.; Fedorenko, N.M.; Kapets, N.V. The fourth checklist of Ukrainian lichen-forming and lichenicolous fungi with analysis of current additions. Acta Bot. Hung. 2021, 63, 97–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diederich, P.; Lawrey, J.D.; Ertz, D. The 2018 classification and checklist of lichenicolous fungi, with 2000 non-lichenized, obligately lichenicolous taxa. Bryologist 2018, 121, 340–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lücking, R.; Hodkinson, B.P.; Leavitt, S.D. The 2016 classification of lichenized fungi in the Ascomycota and Basidiomycota—Approaching one thousand genera. Bryologist 2017, 119, 361–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanavichus, G. A Checklist of the Lichen Flora of Russia; Nauka: St. Petersburg, Russia, 2010; pp. 1–194. [Google Scholar]

- Zhurbenko, M.P. The lichenicolous fungi of Russia: Geographical overview and a first checklist. Mycol. Balcan. 2007, 4, 105–124. [Google Scholar]

- Arcadia, L. Simplified checklist of Greek Lichens and lLichenicolous Fungi. Linda’s Simplified Greek Lichen Checklist, 2016. Version 3 April 2016. Available online: http://www.lichensofgreece.com/checklist.html (accessed on 30 January 2017).

- Ciurchea, M. Checklist of Lichens and Lichenicolous Fungi of Romania, 2007. Available online: http://www.academic.ro/lichens/Checklist.htm (accessed on 11 February 2021).

- Hawksworth, D.L.; Lücking, R. Fungal diversity revisited: 2.2 to 3.8 million species. Microbiol. Spectr. 2017, 5, FUNK-0052-2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).