Bacillus velezensis Enhances Rice Resistance to Brown Spot by Integrating Antifungal and Growth Promotion Functions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Subsection Morphology of Bi. oryzae Under Rice Infection Conditions

2.2. Antagonistic Activity of Bacillus spp. Strains Against Bi. oryzae in In Vitro Assays

2.3. Phylogenetic Characterization of Bacillus Strains

2.4. Effects of Bacillus spp. on Rice Development and Brown Spot Severity

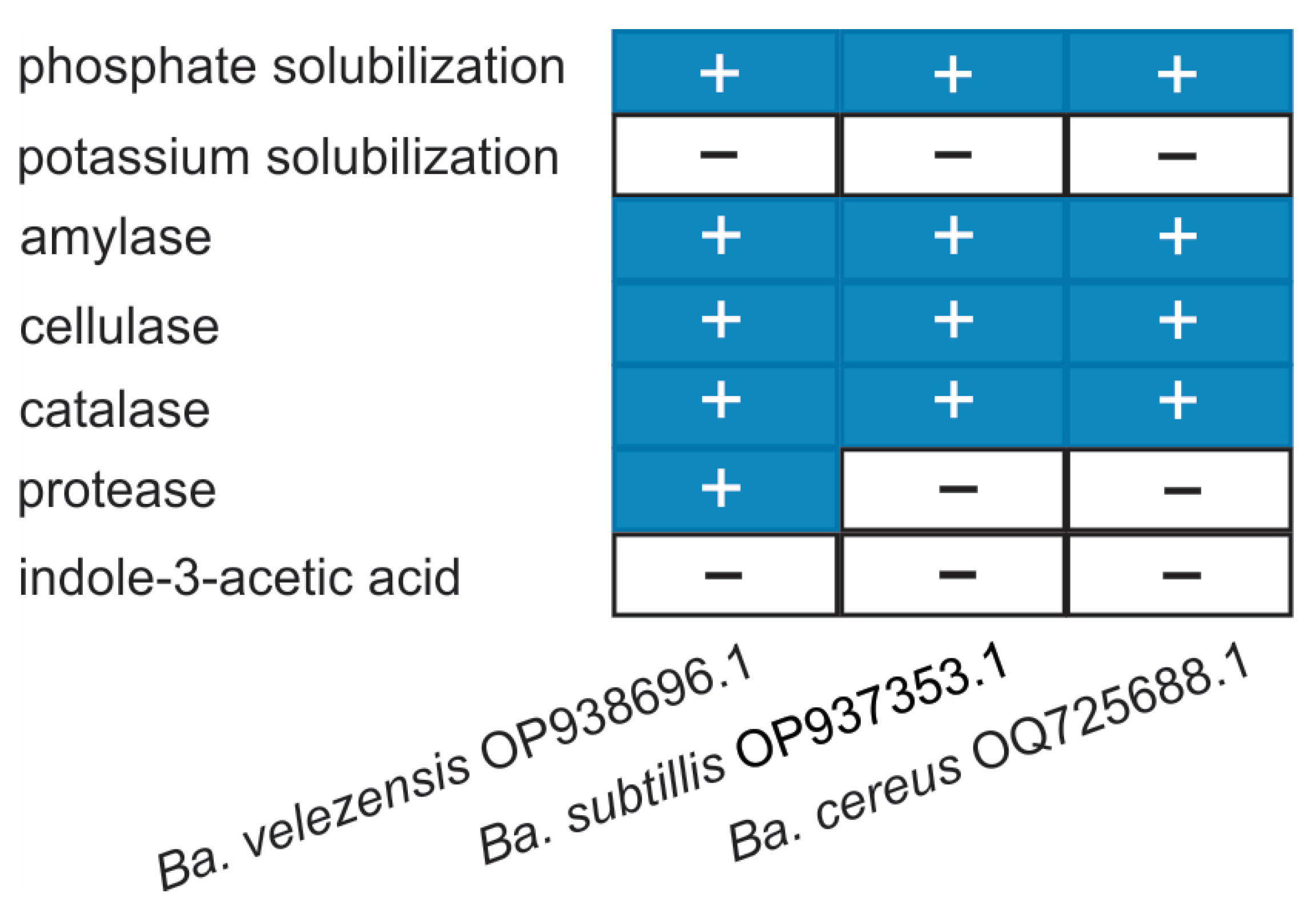

2.5. Biochemical and Functional Characterization of Bacillus spp. Strains

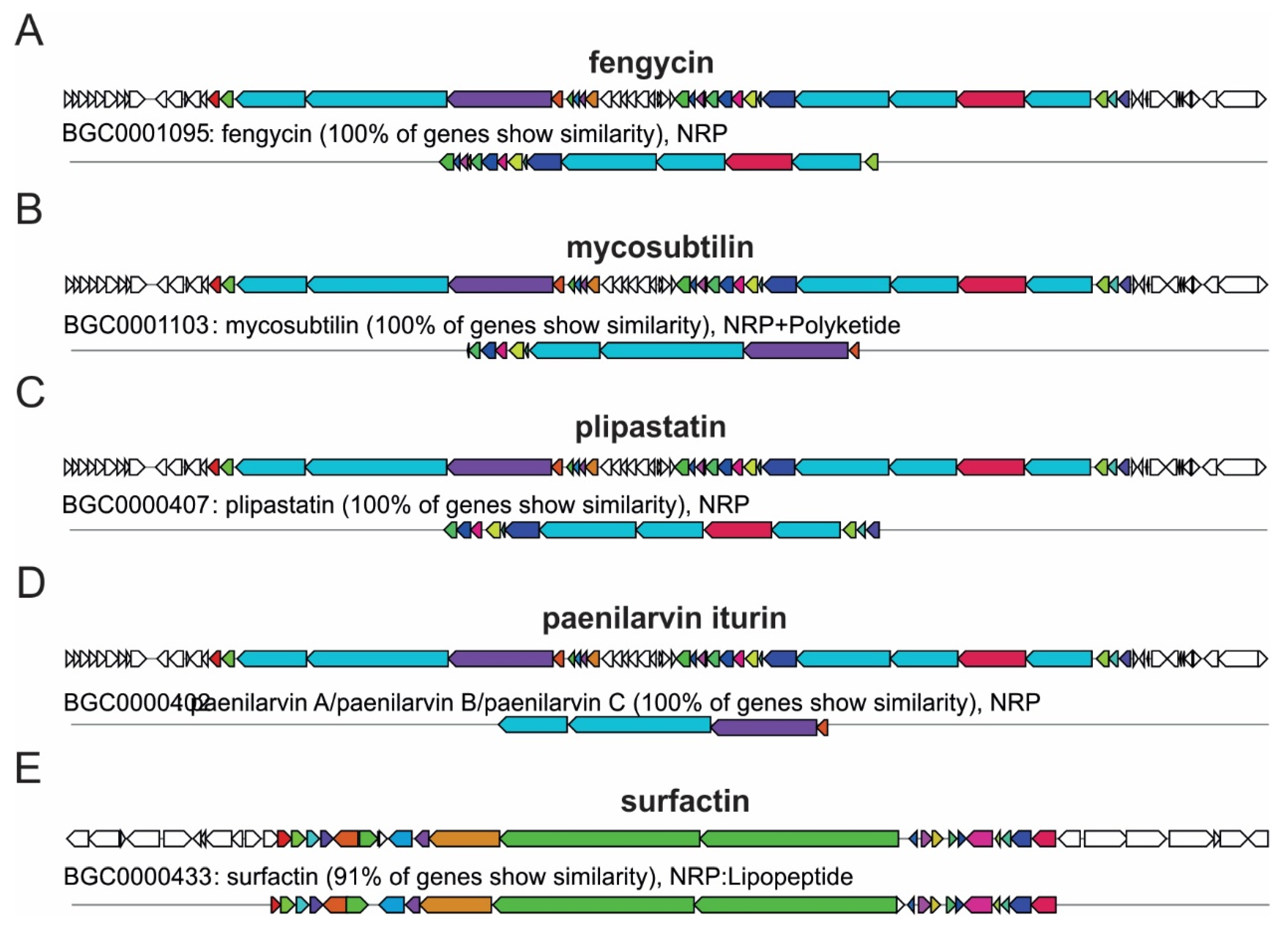

2.6. Genomic Profile of Biosynthetic Gene Clusters in Bacillus spp.

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials, Strain Origin, and Pathogen Isolation

4.2. In Vitro Antagonistic Bioassay

4.3. Plant Biomass Assessment

4.4. Brown Spot Severity Assessment

4.5. Genomic DNA Extraction and Sequencing of the B. velezensis Isolate

4.6. Assays of Enzymatic and Biochemical Activity

- Amylase activity was evaluated on starch agar medium (10 g/L peptone, 5 g/L yeast extract, 5 g/L NaCl, 2 g/L starch, and 15 g/L agar; pH 6.9) following [75]. After incubation, plates were flooded with Lugol’s iodine solution for 30 min, and the presence of a clear halo around colonies indicated positive activity.

- Protease activity was assessed on skim milk agar (3% v/v), incubated at 28 °C for 48 h. Transparent zones around colonies were considered indicative of proteolytic enzyme production [76].

- Phosphate solubilization was determined according to [77]. Isolates were cultured in phosphate-supplemented liquid medium at 28 ± 2 °C with shaking (150 rpm) for 72 h. Solubilized phosphorus was quantified by using the Murphy–Riley method [78], where a color shift from purple to yellow indicated a positive result.

- IAA production was tested in Luria–Bertani (LB) broth supplemented with 100 mg/L tryptophan. Cultures were incubated at 28 °C for five days with shaking at 200 rpm. For detection, 1 mL of culture supernatant was mixed with 2 mL of Salkowski reagent (2% FeCl3·6H2O in 37% HClO4) and incubated in the dark for 12 h. A pink to reddish coloration indicated IAA production [79].

- Catalase activity was determined by adding 1 mL of 3% H2O2 directly to agar-grown cultures previously incubated at 28 °C for 48 h in LB medium (pH 7.0). The immediate formation of oxygen bubbles confirmed a positive reaction [80].

- Cellulase activity was evaluated on minimal medium (MM) supplemented with 1% carboxymethylcellulose (1 g glucose, 2.5 g yeast extract, 15 g agar per liter). After 48 h of incubation at 28 °C, plates were stained with Congo red dye. The appearance of clear yellow halos around colonies indicated cellulase production [81].

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abeysekara, I.; Rathnayake, I. Global Trends in Rice Production, Consumption and Trade. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4948477 (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Conde, S.; Catarino, S.; Ferreira, S.; Temudo, M.P.; Monteiro, F. Rice Pests and Diseases Around the World: Literature-Based Assessment with Emphasis on Africa and Asia. Agriculture 2025, 15, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaboré, K.H.; Kassankogno, A.I.; Tharreau, D. Brown Spot of Rice: Worldwide Disease Impact, Phenotypic and Genetic Diversity of the Causal Pathogen Bipolaris oryzae, and Management of the Disease. Plant Pathol. 2025, 74, 908–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan, S.Y. The Great Bengal Famine. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 1973, 11, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvar-Beltrán, J.; Soldan, R.; Vanuytrecht, E.; Heureux, A.; Shrestha, N.; Manzanas, R.; Pant, K.P.; Franceschini, G. An FAO Model Comparison: Python Agroecological Zoning (PyAEZ) and AquaCrop to Assess Climate Change Impacts on Crop Yields in Nepal. Environ. Dev. 2023, 47, 100882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, S.; Rai, S.; Chakraborty, D.; Sangma, R.H.C.; Majumder, S.; Kuotsu, K.; Chakraborty, M.; Baiswar, P.; Singh, B.K.; Roy, A.; et al. Impact of Weather Variables on Radish Insect Pests in the Eastern Himalayas and Organic Management Strategies. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloyce, A.A. Climate Change and Plant Protection: Challenges and Innovations in Disease Forecasting Systems in Developing Countries. J. Plant Prot. Res. 2025, 65, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuta, Y.; Koide, Y.; Kobayashi, N.; Kato, H.; Saito, H.; Telebanco-Yanoria, M.J.; Ebron, L.A.; Mercado-Escueta, D.; Tsunematsu, H.; Ando, I.; et al. Lines for Blast Resistance Genes with Genetic Background of Indica Group Rice as International Differential Variety Set. Plant Breed. 2022, 141, 609–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizobuchi, R.; Ohashi, S.; Matsumoto, K.; Ota, Y.; Yamakawa, T.; Abe, T.; Ishikawa, S.; Ohmori, S.; Takeuchi, Y.; Goto, A.; et al. Breeding of a Promising Isogenic Line of Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Variety ‘Koshihikari’ with Low Cadmium and Brown Spot (Bipolaris oryzae) Resistance. Breed. Sci. 2024, 74, 462–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, P.K.; Nag, A.; Arya, P.; Kapoor, R.; Singh, A.; Jaswal, R.; Sharma, T.R. Prospects of Understanding the Molecular Biology of Disease Resistance in Rice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keerthana, U.; Phalguni, M.; Prabhukarthikeyan, S.R.; Naveenkumar, R.; Yadav, M.K.; Parameswaran, C.; Baite, M.S.; Raghu, S.; Reddy, M.G.; Harish, S.; et al. Elucidation of the Population Structure and Genetic Diversity of Bipolaris oryzae Associated with Rice Brown Spot Disease Using SSR Markers. 3 Biotech 2022, 12, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, B.; Lv, B.; Xuan, Q.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Liang, W.; Wang, J. Research Progress on Rice-Blast-Resistance-Related Genes. Plants 2025, 14, 2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, T.; Hussain, N.; Ahmed, M.; Nualsri, C.; Duangpan, S. Responses of Lowland Rice Genotypes under Terminal Water Stress and Identification of Drought Tolerance to Stabilize Rice Productivity in Southern Thailand. Plants 2021, 10, 2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, M.C.; Hawkins, N.J.; Sanglard, D.; Gurr, S.J. Worldwide Emergence of Resistance to Antifungal Drugs Challenges Human Health and Food Security. Science 2018, 360, 739–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Danishuddin; Tamanna, N.T.; Matin, M.N.; Barai, H.R.; Haque, M.A. Resistance Mechanisms of Plant Pathogenic Fungi to Fungicide, Environmental Impacts of Fungicides, and Sustainable Solutions. Plants 2024, 13, 2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beyuo, J.; Sackey, L.N.A.; Yeboah, C.; Kayoung, P.Y.; Koudadje, D. The Implications of Pesticide Residue in Food Crops on Human Health: A Critical Review. Discov. Agric. 2024, 2, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Liang, M.; Gu, J.; Shen, Y.; Guo, L.; Wang, Q.; Ji, G. Health Risk Assessment of Triazole Fungicides around a Pesticide Factory in China. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Hu, K.; Li, X.; Liu, C.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, X. Dissipation Dynamics and Dietary Risk Assessment of Four Fungicides as Preservatives in Pear. Agriculture 2022, 12, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso, G.M.; Leite, M.L.F.; Silva, G.G.; Barboza, H.M.; Pinto, T.A.A.; da Costa, M.R.; Aguiar, L.M.; da Silva Teófilo, T.M.; dos Santos, J.B. Pesticide Residue Management in Brazil: Implications for Human Health and the Environment. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, Y.L.; Duque, T.S.; dos Santos, J.B.; dos Santos, E.A. Potential Residual Pesticide Consumption: A Stratified Analysis of Brazilian Families. J. Xenobiot. 2025, 15, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceresini, P.C.; Silva, T.C.; Vicentini, S.N.C.; Júnior, R.P.L.; Moreira, S.I.; Castro-Ríos, K.; Garcés-Fiallos, F.R.; Krug, L.D.; de Moura, S.S.; da Silva, A.G.; et al. Strategies for Managing Fungicide Resistance in the Brazilian Tropical Agroecosystem: Safeguarding Food Safety, Health, and the Environmental Quality. Trop. Plant Pathol. 2024, 49, 36–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.; Feng, A.; Wang, C.; Zhu, X.; Su, J.; Xu, Z.; Yang, J.; Wang, W.; Chen, K.; Chen, B.; et al. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens LM-1 Affects Multiple Cell Biological Processes in Magnaporthe oryzae to Suppress Rice Blast. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios-Rodriguez, A.P.; Espinoza-Culupú, A.; Durán, Y.; Sánchez-Rojas, T. Antimicrobial Activity of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens BS4 against Gram-Negative Pathogenic Bacteria. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yue, Q.; Xin, Y.; Ngea, G.L.N.; Dhanasekaran, S.; Luo, R.; Li, J.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, H. The Biocontrol Potentiality of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens against Postharvest Soft Rot of Tomatoes and Insights into the Underlying Mechanisms. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2024, 214, 112983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucu, M.A.; Choudhary, R.; Trkulja, V.; Garg, S.; Matić, S. Utilizing Environmentally Friendly Techniques for the Sustainable Control of Plant Pathogens: A Review. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, R.F.; Pires, E.B.E.; Sousa, O.F.; Alves, G.B.; Jumbo, L.O.V.; Santos, G.R.; Maia, L.J.; Ribeiro, B.M.; Smagghe, G.; Perino, E.H.B.; et al. A Novel Neotropical Bacillus siamensis Strain Inhibits Soil-Borne Plant Pathogens and Promotes Soybean Growth. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, A.S.; Nascimento, V.L.; de Oliveira, E.E.; Jumbo, L.V.; dos Santos, G.R.; Queiroz, L.L.; da Silva, R.R.; Filho, R.N.A.; Romero, M.A.; de Souza Aguiar, R.W. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Bacillus cereus Isolated from Brazilian Cerrado Soil Act as Phosphate-Solubilizing Bacteria. Curr. Microbiol. 2023, 80, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cawoy, H.; Bettiol, W.; Fickers, P.; Onge, M. Bacillus-Based Biological Control of Plant Diseases. In Pesticides in the Modern World—Pesticides Use and Management; InTech: London, UK, 2011; Volume 1849, pp. 273–302. [Google Scholar]

- Rabbee, M.F.; Hwang, B.S.; Baek, K.H. Bacillus velezensis: A Beneficial Biocontrol Agent or Facultative Phytopathogen for Sustainable Agriculture. Agronomy 2023, 13, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balleux, G.; Höfte, M.; Arguelles-Arias, A.; Deleu, M.; Ongena, M. Bacillus Lipopeptides as Key Players in Rhizosphere Chemical Ecology. Trends Microbiol. 2025, 33, 80–95. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Markelova, N.; Chumak, A. Antimicrobial Activity of Bacillus Cyclic Lipopeptides and Their Role in the Host Adaptive Response to Changes in Environmental Conditions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nifakos, K.; Tsalgatidou, P.C.; Thomloudi, E.E.; Skagia, A.; Kotopoulis, D.; Baira, E.; Delis, C.; Papadimitriou, K.; Markellou, E.; Venieraki, A.; et al. Genomic Analysis and Secondary Metabolites Production of the Endophytic Bacillus velezensis Bvel1: A Biocontrol Agent against Botrytis cinerea Causing Bunch Rot in Post-Harvest Table Grapes. Plants 2021, 10, 1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Estebanez, M.; Sanmartín, P.; Camacho-Chab, J.C.; De la Rosa-García, S.C.; Chan-Bacab, M.J.; Águila-Ramírez, R.N.; Carrillo-Villanueva, F.; De la Rosa-Escalante, E.; Arteaga-Garma, J.L.; Serrano, M.; et al. Characterization of a Native Bacillus velezensis-like Strain for the Potential Biocontrol of Tropical Fruit Pathogens. Biol. Control 2020, 141, 104127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.H.; Park, B.S.; Kim, H.Y.; Lee, K.H.; Kim, K.S. Antagonistic and Plant Growth-Promoting Effects of Bacillus velezensis BS1 Isolated from Rhizosphere Soil in a Pepper Field. Plant Pathol. J. 2021, 37, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, K.; Wang, X.; Xing, M.; Xu, Q.; Guo, Y. A Novel Biocontrol Agent Bacillus velezensis K01 for Management of Gray Mold Caused by Botrytis cinerea. AMB Express 2023, 13, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, M.; Zhu, Z.; Zhao, X.; Cai, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, Y.; Yin, K.; Sha, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, G.; et al. The Versatile Plant Probiotic Bacterium Bacillus velezensis SF305 Reduces Red Root Rot Disease Severity in the Rubber Tree by Degrading the Mycelia of Ganoderma pseudoferreum. J. Integr. Agric. 2025, 24, 3112–3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Jia, S.; Du, Y.; Cao, H.; Zhang, K.; Xing, J.; Dong, J. Biocontrol Potential of Bacillus Subtilis A3 Against Corn Stalk Rot and Its Impact on Root-Associated Microbial Communities. Agronomy 2025, 15, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehan, M.; Al-Turki, A.; Abdelmageed, A.H.A.; Abdelhameid, N.M.; Omar, A.F. Performance of Plant-Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) Isolated from Sandy Soil on Growth of Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Plants 2023, 12, 1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Chen, A.; Zhou, Y.; Qian, Q.; Qin, L.; Tang, X.; Jiang, Q.; Zhang, X. Genomic Characterization and Probiotic Potency of Bacillus velezensis CPA1-1 Reveals Its Potential for Aquaculture Applications. Aquaculture 2025, 596, 741852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Guo, A.; Zou, D.; Li, Z.; Wei, X. Efficient Production of Spermidine from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens by Enhancing Synthesis Pathway, Blocking Degradation Pathway and Increasing Precursor Supply. J. Biotechnol. 2025, 398, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khemmuk, W.; Boonchuay, D.; Jungkhun, N.; Klinmanee, C.; Kantachan, A. Biological Control of Rice Brown Spot by Bacillus spp. in Thailand. In Proceedings of the Third International Tropical Agriculture Conference, Brisbane, Australia, 11–13 November 2019; MDPI AG: Basel, Switzerland, 2020; p. 217. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.; Wang, J.; Liu, B.; Zhu, Y.; Xiao, R.; Yang, W.; Ge, C.; Chen, Z. Biocontrol of Tomato Bacterial Wilt by the New Strain Bacillus velezensis FJAT-46737 and Its Lipopeptides. BMC Microbiol. 2020, 20, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Xie, Y.; Liao, Y.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Li, S.; Ma, X.; Lei, S.; Lin, F.; Jiang, W.; et al. Characterization of a Bacillus velezensis Strain Isolated from Bolbostemmatis rhizoma Displaying Strong Antagonistic Activities against a Variety of Rice Pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 983781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Liu, J.; He, Y.; Payizila, A.; Li, Y. Biological Control Ability and Antifungal Activities of Bacillus velezensis Bv S3 against Fusarium oxysporum That Causes Rice Seedling Blight. Agronomy 2024, 14, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Zhang, J.; Fan, J.; Li, D.; Zhao, M.; Wang, Y.; Pan, H.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, X. Antagonistic Mechanism Analysis of Bacillus velezensis JLU-1, a Biocontrol Agent of Rice Pathogen Magnaporthe oryzae. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 19657–19666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashfaq, M.; Abdul, R.; Ali, M.; Sajjad, B.R.; Shaheen, S.; Shafiq, M.; Javed, M.A.; Mubashar, U.; Anwar, A.; Haider, S.M. Identification and Phatogenic Characterization of Bacteria Causing Rice Gran Discoloration in Pakistan. J. Agric. Sci. 2022, 59, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Bahir, M.A.; Berhan, M.; Abera, M.; Bekele, B. Screening of Brown Spot (Bipolaris oryzae) Disease Resistant Lowland Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Genotypes at Fogera, Ethiopia. J. Plant Pathol. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.P.; Kumar, A.; Mohammed, M.; Bhati, K.; Babu, K.R.; Bhandari, K.P.; Sundaram, R.M.; Ghazi, I.A. Comparative Metabolites Analysis of Resistant, Susceptible and Wild Rice Species in Response to Bacterial Blight Disease. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, S.; Rashid, M.; Hameed, A.; Fiaz, S.; Rebouh, N.Y.; Zaman, Q.U. Development of Rice Mutants with Enhanced Resilience to Drought and Brown Spot (Bipolaris oryzae) and Their Physiological and Multivariate Analysis. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, T.Q.; Nguyen, T.T.; Dinh, V.M. Application of Endophytic Bacterium Bacillus velezensis BTR11 to Control Bacterial Leaf Blight Disease and Promote Rice Growth. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control 2023, 33, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveena, S.; Gopalakrishnan, C.; Logeshwari, R.; Raveendran, M.; Pushpam, R.; Lakshmidevi, P. Metabolomic Profiling of Bacillus velezensis B13 and Unveiling Its Antagonistic Potential for the Sustainable Management of Rice Sheath Blight. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1554867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, L.C.D.S.; Raphael, J.P.A.; Bortolotto, R.P.; Nora, D.D.; Gruhn, E.M. Blast Disease in Rice Culture. Appl. Res. Agrotechnol. 2014, 7, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa, W.G.; da Silva Júnior, A.C.; Barbosa, I.D.P.; Cruz, C.D.; Borém, A.; Soares, P.C.; Gonçalves, R.D.P.; Torga, P.P.; Condé, A.B.T. Quarter Century Genetic Progress in Irrigated Rice (Oryza sativa) in Southeast Brazil. Plant Breed. 2021, 140, 990–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzade, B.; Singh, D.; Phani, V.; Kumbhar, S.; Rao, U. Profiling of Defense Responsive Pathway Regulatory Genes in Asian Rice (Oryza sativa) against Infection of Meloidogyne graminicola (Nematoda: Meloidogynidae). 3 Biotech 2020, 10, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, N. Understanding Disease Resistance Signaling in Rice Against Various Pests and Pathogens; Austin Publishing Group: Wimauma, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Yan, S.; Li, G.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Cui, Z.; Sun, S.; Huo, J.; Sun, Y. Rice-Magnaporthe oryzae Interactions in Resistant and Susceptible Rice Cultivars under Panicle Blast Infection Based on Defense-Related Enzyme Activities and Metabolomics. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0299999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, X.; Dai, J.; Xu, Z.; Diao, Y.; Yang, N.; Fan, Y.; Ma, M.; Zhao, J.; Li, X.; Gao, S.; et al. Comprehensive Evaluation and Mechanisms of Bacillus velezensis AX22 against Rice Bacterial Blight. Biol. Control 2025, 207, 105820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, G.; Zhao, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, R.; Huang, Y.; Qi, G. Engineering Bacillus velezensis with High Production of Acetoin Primes Strong Induced Systemic Resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Microbiol. Res. 2019, 227, 126297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, H.; Wang, S.; Li, X.; Li, X.; Cai, J.; Zhao, L.; Wang, J.; Zeng, J.; Qin, Y.; Xiong, X.; et al. Biological Control of Potato Common Scab and Growth Promotion of Potato by Bacillus velezensis Y6. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1295107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Q.; Yu, J.; Wu, Y.; Yao, X.; Mao, C.; Meng, X.; Ming, F. Rice Transcription Factor OsNAC2 Maintains the Homeostasis of Immune Responses to Bacterial Blight. Plant Physiol. 2024, 195, 785–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrea-Izurieta, I.; Borja, C.F.; Arcos-Andrade, A. Aislamiento y Caracterización de Cepas de Bacillus spp. Con Actividad Contra Tetranychus urticae Koch En Cultivos Comerciales de Rosas. Rev. Colomb. Biotecnol. 2015, 17, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, H.L.; Hunter, B.B. Illustrated Genera of Imperfect Fungi; American Phytopathological Society (APS Press): St. Paul, MN, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bulhões, T.; Sadykov, R.; Subramanian, A.; Uchoa, E. On the Exact Solution of a Large Class of Parallel Machine Scheduling Problems. J. Sched. 2020, 23, 411–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrano, M.A.R.; Castanharo, G.R.P.; de Souza Aguiar, R.W.; Junior, A.F.C. Atividade Antagônica in Vitro de Sclerotium sp. Por Bacillus sp. Res. Soc. Dev. 2022, 11, e380111335351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejón-Martínez, G.A.; Ríos-Muñiz, D.E.; Contreras-Leal, E.A.; Evangelista-Martínez, Z. Antagonist Activity Of Streptomyces sp. Y20 Against Fungi Causing Diseases in Plants and Fruits. Trop. Subtrop. Agroecosyst. 2022, 25, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.C.; Jia, Y.; Wen, J.W.; Liu, W.P.; Liu, X.M.; Li, L.; Jiang, Z.Y.; Zhang, J.H.; Guo, X.L.; Ren, J.P. Identification of Rice Blast Resistance Genes Using International Monogenic Differentials. Crop Prot. 2013, 45, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perina, F.J.; Belan, L.L.; Moreira, S.I.; Nery, E.M.; Alves, E.; Pozza, E.A. Diagrammatic Scale for Assessment of Alternaria Brown Spot Severity on Tangerine Leaves. J. Plant Pathol. 2019, 101, 981–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prjibelski, A.; Antipov, D.; Meleshko, D.; Lapidus, A.; Korobeynikov, A. Using SPAdes De Novo Assembler. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2020, 70, e102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, W.; Le, S.; Li, Y.; Hu, F. SeqKit: A Cross-Platform and Ultrafast Toolkit for FASTA/Q File Manipulation. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0163962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Göker, M. TYGS Is an Automated High-Throughput Platform for State-of-the-Art Genome-Based Taxonomy. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.; Nash, J.H.E. MOB-Suite: Software Tools for Clustering, Reconstruction and Typing of Plasmids from Draft Assemblies. Microb. Genom. 2018, 4, e000206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seemann, T. Prokka: Rapid Prokaryotic Genome Annotation. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2068–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Sato, Y.; Kawashima, M. KEGG Mapping Tools for Uncovering Hidden Features in Biological Data. Protein Sci. 2022, 31, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blin, K.; Shaw, S.; Augustijn, H.E.; Reitz, Z.L.; Biermann, F.; Alanjary, M.; Fetter, A.; Terlouw, B.R.; Metcalf, W.W.; Helfrich, E.J.N.; et al. AntiSMASH 7.0: New and Improved Predictions for Detection, Regulation, Chemical Structures and Visualisation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, W46–W50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda-Ohtsubo, W.; Miyahara, M.; Kim, S.-W.; Yamada, T.; Matsuoka, M.; Watanabe, A.; Fushinobu, S.; Wakagi, T.; Shoun, H.; Miyauchi, K.; et al. Bioaugmentation of a Wastewater Bioreactor System with the Nitrous Oxide-Reducing Denitrifier Pseudomonas stutzeri Strain TR2. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2013, 115, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.H.; Won, S.J.; Maung, C.E.H.; Choi, J.H.; Choi, S.I.; Ajuna, H.B.; Ahn, Y.S. Bacillus velezensis Ce 100 Inhibits Root Rot Diseases (Phytophthora spp.) and Promotes Growth of Japanese Cypress (Chamaecyparis obtusa Endlicher) Seedlings. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, H.L.; da Silva, G.F.; Carnietto, M.R.A.; da Silva, G.F.; Fernandes, C.N.; Ferreira, L.D.S.; de Almeida Silva, M. Improving Sugarcane Biomass and Phosphorus Fertilization Through Phosphate-Solubilizing Bacteria: A Photosynthesis-Based Approach. Plants 2025, 14, 2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, Y.-H.; Nielsen, S.S. Phosphorus Determination by Murphy-Riley Method. In Food Analysis Laboratory Manual; Springer: Cham, Switzerland; West Lafayette, IN, USA, 2017; pp. 153–156. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, F.; Ahmad, I.; Khan, M.S. Screening of Free-Living Rhizospheric Bacteria for Their Multiple Plant Growth Promoting Activities. Microbiol. Res. 2008, 163, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadwan, M.H.; Ali, S.K. New Spectrophotometric Assay for Assessments of Catalase Activity in Biological Samples. Anal. Biochem. 2018, 542, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carhuapoma-Delacruz, V.; Auqui-Acharte, G.S.; Valencia-Mamani, N.; Gonzales-Huamán, T.J.; Guillen-Domínguez, H.M.; Esparza, M. Fibrolytic Bacteria Isolated from the Rumen of Alpaca, Sheep and Cattle with Cellulose Biodegrading Capacity. Rev. Cient. Fac. Vet. 2022, 32, e32094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pires, E.B.E.; Tique Obando, M.S.; Janssen, L.; Ribeiro, B.M.; Souza, O.F.; Dias, M.L.; Viteri Jumbo, L.O.; Fidelis, R.R.; Santos, G.R.; Rocha, R.N.C.; et al. Bacillus velezensis Enhances Rice Resistance to Brown Spot by Integrating Antifungal and Growth Promotion Functions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 1455. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031455

Pires EBE, Tique Obando MS, Janssen L, Ribeiro BM, Souza OF, Dias ML, Viteri Jumbo LO, Fidelis RR, Santos GR, Rocha RNC, et al. Bacillus velezensis Enhances Rice Resistance to Brown Spot by Integrating Antifungal and Growth Promotion Functions. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(3):1455. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031455

Chicago/Turabian StylePires, Elizabeth B. E., Maira S. Tique Obando, Luis Janssen, Bergmann M. Ribeiro, Odaiza F. Souza, Marcelo L. Dias, Luís O. Viteri Jumbo, Rodrigo R. Fidelis, Gil R. Santos, Raimundo N. C. Rocha, and et al. 2026. "Bacillus velezensis Enhances Rice Resistance to Brown Spot by Integrating Antifungal and Growth Promotion Functions" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 3: 1455. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031455

APA StylePires, E. B. E., Tique Obando, M. S., Janssen, L., Ribeiro, B. M., Souza, O. F., Dias, M. L., Viteri Jumbo, L. O., Fidelis, R. R., Santos, G. R., Rocha, R. N. C., Smagghe, G., Bacca, T., Oliveira, E. E., Haumann, R., & Aguiar, R. W. S. (2026). Bacillus velezensis Enhances Rice Resistance to Brown Spot by Integrating Antifungal and Growth Promotion Functions. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(3), 1455. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031455