EZHIP in Pediatric Brain Tumors: From Epigenetic Mimicry to Therapeutic Vulnerabilities

Abstract

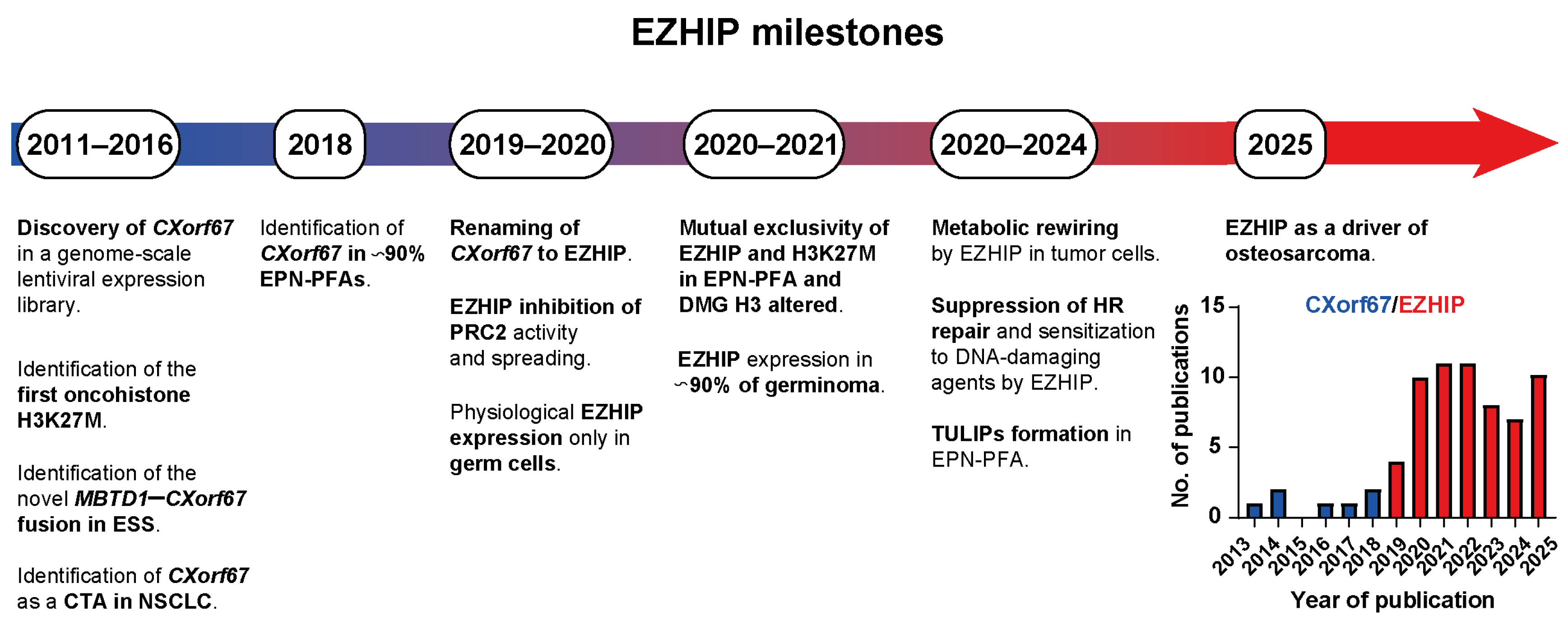

1. Introduction

2. EZHIP: A Protein in Its Infancy

2.1. The EZHIP Gene

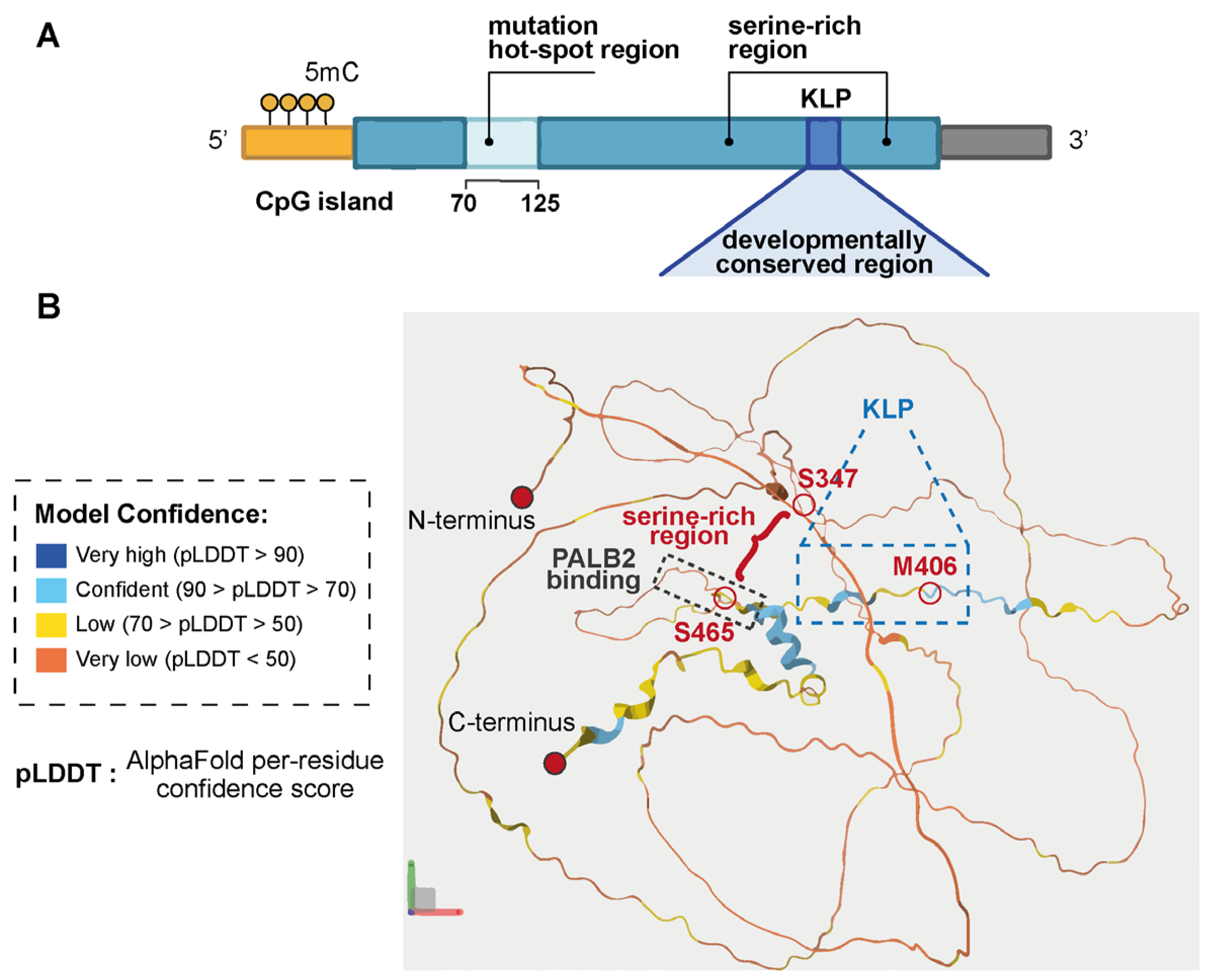

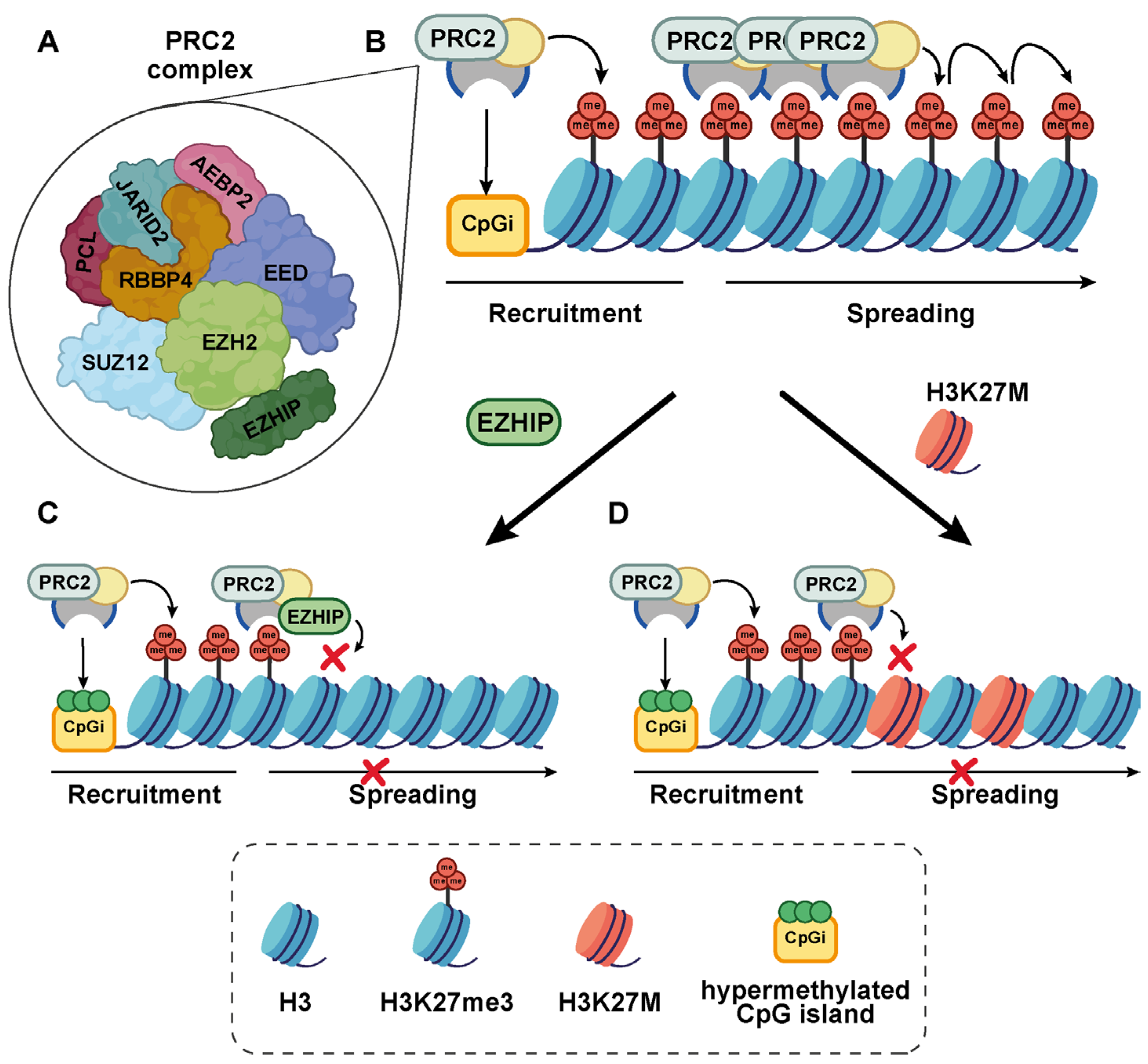

2.2. EZHIP: Structure and PRC2 Inhibitory Function

EZHIP Interactome: What Is Known

3. The Epigenetic Landscape of EZHIP and Beyond

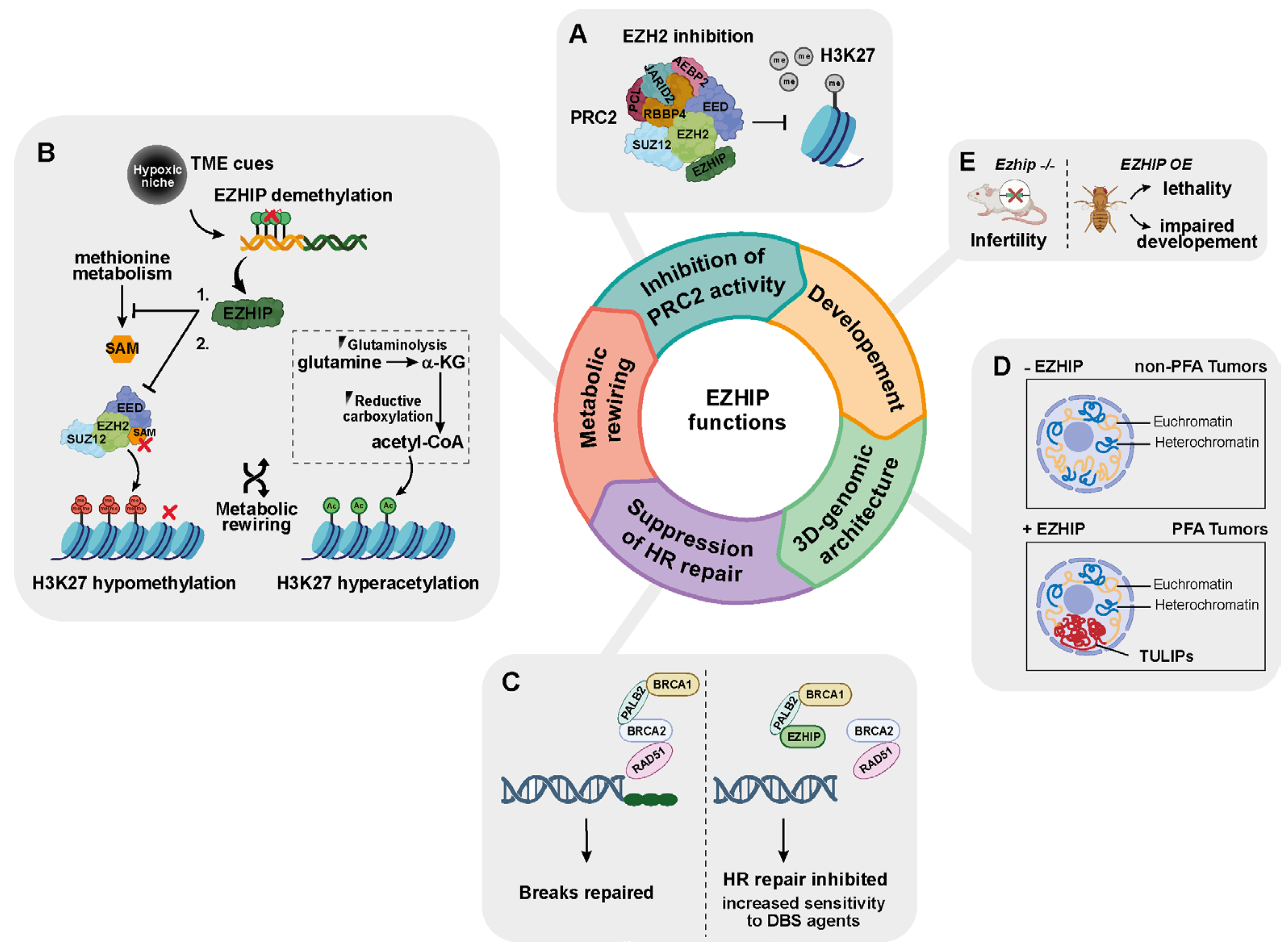

3.1. EZHIP as an Epigenetic Modulator: Evidence from Cell-Based Studies

3.2. EZHIP Connects Metabolism to Epigenetic Rewiring of Tumor Cells

3.3. EZHIP Is a DNA Damage Response Protein

3.4. EZHIP Is a Modeler of 3D Chromatin Architecture

3.5. EZHIP and Animal Models

| Feature | EZHIP | H3K27M |

|---|---|---|

| Mode of PRC2 interaction | Non-histone PRC2 inhibitor [20,21,22] | Oncohistone incorporated into chromatin [6] |

| PRC2 inhibition mechanism [20,21,22] | EZH2 active-site engagement | EZH2 active-site engagement |

| Reversibility of PRC2 inhibition | Potentially reversible | Persistent due to chromatin incorporation |

| EZH2 inhibitory potency [22] | Higher (IC50 = 4.1 μM) | Lower (IC50 = 27.87 μM) |

| Inhibition of PRC2 spreading activity [10] | Yes | Yes |

| Global loss of H3K27me3 [20,21,22] | Yes | Yes |

| Focal gain of H3K27me3 at CpG islands [22] | Yes | Yes |

| Inhibition of homologous recombination | Yes [28] | No |

| Developmental lethality (Drosophila) [66] | Early larval lethality | Later developmental arrest |

| 3D chromatin reorganization (TULIPs) [30] | Present (EPN-PFA) | Absent (DMG) |

4. A Clinical Standpoint

4.1. EZHIP in Pediatric Brain Tumors

4.1.1. EZHIP Is a Biomarker of EPN-PFA

4.1.2. EZHIP Defines a Subtype of H3K27-Altered DMG

4.1.3. Germinoma

4.1.4. Medulloblastoma (MB)

4.1.5. Atypical Teratoid/Rhabdoid Tumor (AT/RT)

4.1.6. MYCN-Amplified Glioblastomas (MYCN_GBMs)

4.2. EZHIP and Adult Cancers

4.2.1. Endometrial Stroma Sarcoma (ESS)

4.2.2. Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC)

4.2.3. Merkel Cell Carcinoma (MCC)

4.2.4. Osteosarcoma (OS)

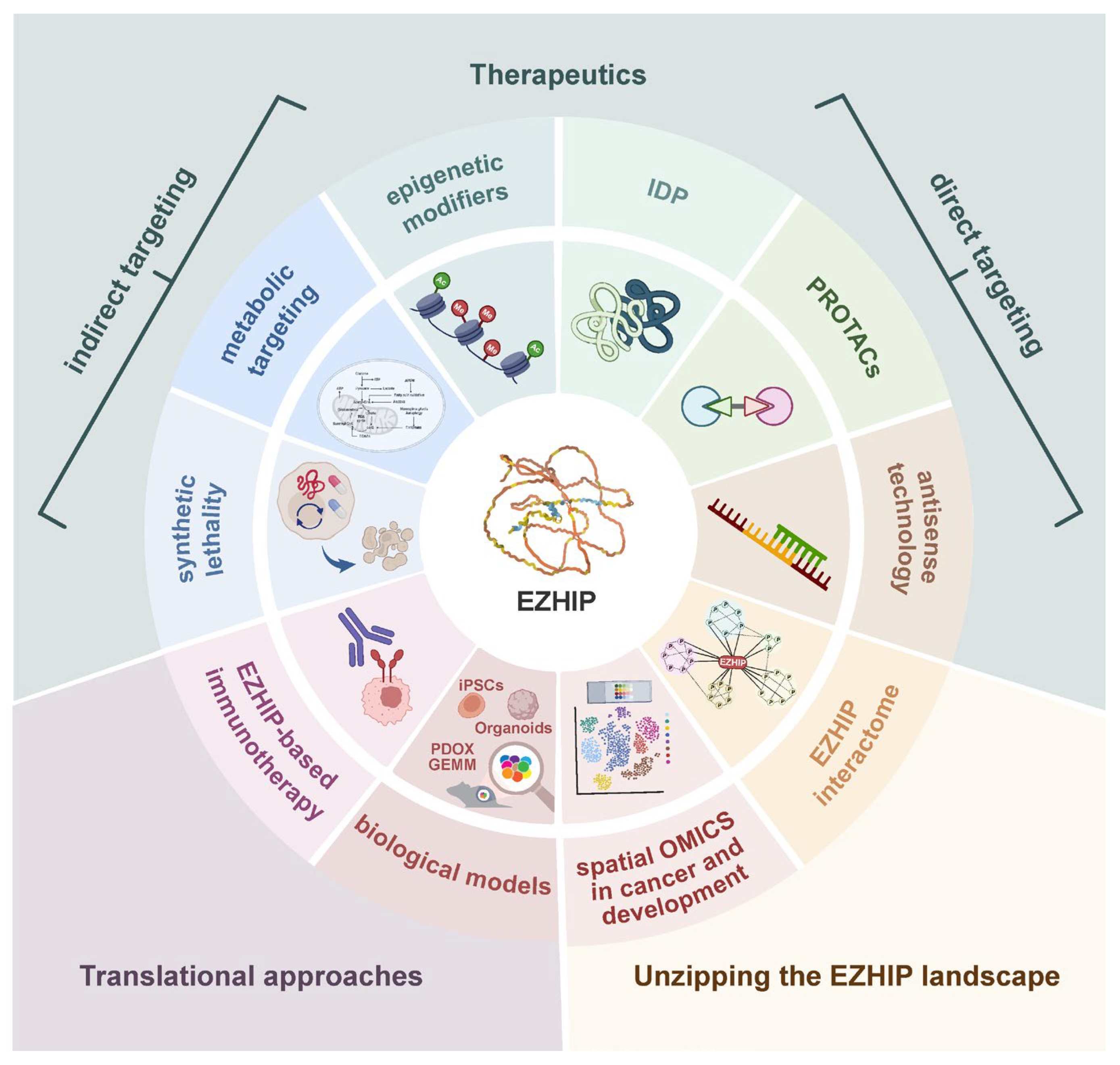

5. From Undruggable to Vulnerable: Strategies to Target EZHIP-Driven Tumors

5.1. Direct Targeting

5.1.1. EZHIP as an IDP

5.1.2. Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras (PROTACs)

5.1.3. Antisense Technologies

5.2. Indirect Targeting

5.3. EZHIP-Based Immunotherapy

5.4. Intratumoral EZHIP Heterogeneity: Implications for Therapeutic Development

6. Current Gaps and Future Directions

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 5mC | 5-methylcytosine |

| a-KG | Alpha-ketoglutarate |

| ASOs | Antisense oligonucleotides |

| AT/RT | Atypical teratoid/Rhabdoid tumor |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| CTA | Cancer testis antigen |

| Cxorf67 | Chromosome X open reading frame 67 |

| DMG | Diffuse midline glioma |

| DSB | Double-strand break |

| EED | Embryonic ectoderm development |

| EPN-PFA | Posterior fossa ependymoma subtype A |

| ESCs | Embryonic stem cells |

| ESS | Endometrial stroma sarcoma |

| EZH2 | Enhancer of zeste 2 polycomb repressive complex 2 subunit |

| EZHIP | Enhancer of zeste homologs inhibitory protein |

| GCs | Germ cells |

| H3K27M | H3 lysine 27 to methionine |

| H3K27me3 | H3 lysine 27 trimethylation |

| hNPCs | Human neural progenitor cells |

| HR | Homologous recombination |

| IDP | Intrinsically disordered protein |

| IG | Intronless gene |

| KLP | K27M-like peptide |

| MB | Medulloblastoma |

| MCC | Merkel cell carcinoma |

| NSCLC | Non-small-cell lung cancer |

| OS | Osteosarcoma |

| PALB2 | Partner and localizer of BRCA2 |

| PRC2 | Polycomb repressive complex 2 |

| PROTACs | Proteolysis targeting chimera |

| SAM | S-adenosyl methionine |

| SNVs | Single nucleotide variants |

| TCA | Tricarboxylic acid |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| TULIP | Type B ultra long-range interactions in PFA |

References

- Pfister, S.M.; Reyes-Múgica, M.; Chan, J.K.C.; Hasle, H.; Lazar, A.J.; Rossi, S.; Ferrari, A.; Jarzembowski, J.A.; Pritchard-Jones, K.; Hill, D.A.; et al. A Summary of the Inaugural WHO Classification of Pediatric Tumors: Transitioning from the Optical into the Molecular Era. Cancer Discov. 2022, 12, 331–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bender, S.; Tang, Y.; Lindroth, A.M.; Hovestadt, V.; Jones, D.T.W.; Kool, M.; Zapatka, M.; Northcott, P.A.; Sturm, D.; Wang, W.; et al. Reduced H3K27me3 and DNA Hypomethylation Are Major Drivers of Gene Expression in K27M Mutant Pediatric High-Grade Gliomas. Cancer Cell 2013, 24, 660–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayliss, J.; Mukherjee, P.; Lu, C.; Jain, S.U.; Chung, C.; Martinez, D.; Sabari, B.; Margol, A.S.; Panwalkar, P.; Parolia, A.; et al. Lowered H3K27me3 and DNA Hypomethylation Define Poorly Prognostic Pediatric Posterior Fossa Ependymomas. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016, 8, 366ra161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pajtler, K.W.; Wen, J.; Sill, M.; Lin, T.; Orisme, W.; Tang, B.; Hübner, J.-M.; Ramaswamy, V.; Jia, S.; Dalton, J.D.; et al. Molecular Heterogeneity and CXorf67 Alterations in Posterior Fossa Group A (PFA) Ependymomas. Acta Neuropathol. 2018, 136, 211–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartzentruber, J.; Korshunov, A.; Liu, X.-Y.; Jones, D.T.W.; Pfaff, E.; Jacob, K.; Sturm, D.; Fontebasso, A.M.; Quang, D.-A.K.; Tönjes, M.; et al. Driver Mutations in Histone H3.3 and Chromatin Remodelling Genes in Paediatric Glioblastoma. Nature 2012, 482, 226–231, Correction in Nature 2012, 484, 130. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Broniscer, A.; McEachron, T.A.; Lu, C.; Paugh, B.S.; Becksfort, J.; Qu, C.; Ding, L.; Huether, R.; Parker, M.; et al. Somatic Histone H3 Alterations in Pediatric Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Gliomas and Non-Brainstem Glioblastomas. Nat. Genet. 2012, 44, 251–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, P.W.; Müller, M.M.; Koletsky, M.S.; Cordero, F.; Lin, S.; Banaszynski, L.A.; Garcia, B.A.; Muir, T.W.; Becher, O.J.; Allis, C.D. Inhibition of PRC2 Activity by a Gain-of-Function H3 Mutation Found in Pediatric Glioblastoma. Science 2013, 340, 857–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambirajan, A.; Sharma, A.; Rajeshwari, M.; Boorgula, M.T.; Doddamani, R.; Garg, A.; Suri, V.; Sarkar, C.; Sharma, M.C. EZH2 Inhibitory Protein (EZHIP/Cxorf67) Expression Correlates Strongly with H3K27me3 Loss in Posterior Fossa Ependymomas and Is Mutually Exclusive with H3K27M Mutations. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2021, 38, 30–40, Erratum in Brain Tumor Pathol. 2021, 38, 145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10014-020-00393-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariet, C.; Castel, D.; Grill, J.; Saffroy, R.; Dangouloff-Ros, V.; Boddaert, N.; Llamas-Guttierrez, F.; Chappé, C.; Puget, S.; Hasty, L.; et al. Posterior Fossa Ependymoma H3 K27-Mutant: An Integrated Radiological and Histomolecular Tumor Analysis. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2022, 10, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.U.; Rashoff, A.Q.; Krabbenhoft, S.D.; Hoelper, D.; Do, T.J.; Gibson, T.J.; Lundgren, S.M.; Bondra, E.R.; Deshmukh, S.; Harutyunyan, A.S.; et al. H3 K27M and EZHIP Impede H3K27-Methylation Spreading by Inhibiting Allosterically Stimulated PRC2. Mol. Cell 2020, 80, 726–735.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krug, B.; De Jay, N.; Harutyunyan, A.S.; Deshmukh, S.; Marchione, D.M.; Guilhamon, P.; Bertrand, K.C.; Mikael, L.G.; McConechy, M.K.; Chen, C.C.L.; et al. Pervasive H3K27 Acetylation Leads to ERV Expression and a Therapeutic Vulnerability in H3K27M Gliomas. Cancer Cell 2019, 35, 782–797.e8, Erratum in Cancer Cell 2019, 36, 338–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccell.2019.08.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pun, M.; Pratt, D.; Nano, P.R.; Joshi, P.K.; Jiang, L.; Englinger, B.; Rao, A.; Cieslik, M.; Chinnaiyan, A.M.; Aldape, K.; et al. Common Molecular Features of H3K27M DMGs and PFA Ependymomas Map to Hindbrain Developmental Pathways. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2023, 11, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassim, A.; Colino-Sanguino, Y.; Fox, S.L.; Rodriguez de la Fuente, L.; Hartley, H.E.; Valdes-Mora, F. The Bermuda Triangle of Paediatric Brain Cancers: Epigenetics, Developmental Timing Window and Cell of Origin. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2025, 44, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nacev, B.A.; Feng, L.; Bagert, J.D.; Lemiesz, A.E.; Gao, J.; Soshnev, A.A.; Kundra, R.; Schultz, N.; Muir, T.W.; Allis, C.D. The Expanding Landscape of ‘Oncohistone’ Mutations in Human Cancers. Nature 2019, 567, 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahu, V.; Lu, C. Oncohistones: Hijacking the Histone Code. Annu. Rev. Cancer Biol. 2022, 6, 293–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocasio, J.K.; Budd, K.M.; Roach, J.T.; Andrews, J.M.; Baker, S.J. Oncohistones and Disrupted Development in Pediatric-Type Diffuse High-Grade Glioma. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2023, 42, 367–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, D.P.; Somyajit, K. Oncohistone-Sculpted Epigenetic Mechanisms in Pediatric Brain Cancer. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2025, 81, 102505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragazzini, R.; Pérez-Palacios, R.; Baymaz, I.H.; Diop, S.; Ancelin, K.; Zielinski, D.; Michaud, A.; Givelet, M.; Borsos, M.; Aflaki, S.; et al. EZHIP Constrains Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 Activity in Germ Cells. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Boehm, J.S.; Yang, X.; Salehi-Ashtiani, K.; Hao, T.; Shen, Y.; Lubonja, R.; Thomas, S.R.; Alkan, O.; Bhimdi, T.; et al. A Public Genome-Scale Lentiviral Expression Library of Human ORFs. Nat. Methods 2011, 8, 659–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piunti, A.; Smith, E.R.; Morgan, M.A.J.; Ugarenko, M.; Khaltyan, N.; Helmin, K.A.; Ryan, C.A.; Murray, D.C.; Rickels, R.A.; Yilmaz, B.D.; et al. CATACOMB: An Endogenous Inducible Gene That Antagonizes H3K27 Methylation Activity of Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 via an H3K27M-like Mechanism. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaax2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübner, J.-M.; Müller, T.; Papageorgiou, D.N.; Mauermann, M.; Krijgsveld, J.; Russell, R.B.; Ellison, D.W.; Pfister, S.M.; Pajtler, K.W.; Kool, M. EZHIP/CXorf67 Mimics K27M Mutated Oncohistones and Functions as an Intrinsic Inhibitor of PRC2 Function in Aggressive Posterior Fossa Ependymoma. Neuro Oncol. 2019, 21, 878–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, S.U.; Do, T.J.; Lund, P.J.; Rashoff, A.Q.; Diehl, K.L.; Cieslik, M.; Bajic, A.; Juretic, N.; Deshmukh, S.; Venneti, S.; et al. PFA Ependymoma-Associated Protein EZHIP Inhibits PRC2 Activity through a H3 K27M-like Mechanism. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewaele, B.; Przybyl, J.; Quattrone, A.; Finalet Ferreiro, J.; Vanspauwen, V.; Geerdens, E.; Gianfelici, V.; Kalender, Z.; Wozniak, A.; Moerman, P.; et al. Identification of a Novel, Recurrent MBTD1-CXorf67 Fusion in Low-Grade Endometrial Stromal Sarcoma. Int. J. Cancer 2014, 134, 1112–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djureinovic, D.; Hallström, B.M.; Horie, M.; Mattsson, J.S.M.; La Fleur, L.; Fagerberg, L.; Brunnström, H.; Lindskog, C.; Madjar, K.; Rahnenführer, J.; et al. Profiling Cancer Testis Antigens in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. JCI Insight 2016, 1, e86837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harutyunyan, A.S.; Krug, B.; Chen, H.; Papillon-Cavanagh, S.; Zeinieh, M.; De Jay, N.; Deshmukh, S.; Chen, C.C.L.; Belle, J.; Mikael, L.G.; et al. H3K27M Induces Defective Chromatin Spread of PRC2-Mediated Repressive H3K27me2/Me3 and Is Essential for Glioma Tumorigenesis. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwalkar, P.; Tamrazi, B.; Dang, D.; Chung, C.; Sweha, S.; Natarajan, S.K.; Pun, M.; Bayliss, J.; Ogrodzinski, M.P.; Pratt, D.; et al. Targeting Integrated Epigenetic and Metabolic Pathways in Lethal Childhood PFA Ependymomas. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021, 13, eabc0497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michealraj, K.A.; Kumar, S.A.; Kim, L.J.Y.; Cavalli, F.M.G.; Przelicki, D.; Wojcik, J.B.; Delaidelli, A.; Bajic, A.; Saulnier, O.; MacLeod, G.; et al. Metabolic Regulation of the Epigenome Drives Lethal Infantile Ependymoma. Cell 2020, 181, 1329–1345.e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Yu, M.; Bai, Y.; Yu, J.; Jin, F.; Li, C.; Zeng, R.; Peng, J.; Li, A.; Song, X.; et al. Elevated CXorf67 Expression in PFA Ependymomas Suppresses DNA Repair and Sensitizes to PARP Inhibitors. Cancer Cell 2020, 38, 844–856.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Yu, J.; Yu, M.; Liu, Y.; Song, X.; Li, H.; Li, L. Synergistic Effect of Poly (ADP-Ribose) Polymerase (PARP) Inhibitor with Chemotherapy on CXorf67-Elevated Posterior Fossa Group A Ependymoma. Chin. Med. J. 2024, 137, 2770–2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, M.J.; Lee, J.J.Y.; Hu, B.; Nikolic, A.; Hasheminasabgorji, E.; Baguette, A.; Paik, S.; Chen, H.; Kumar, S.; Chen, C.C.L.; et al. TULIPs Decorate the Three-Dimensional Genome of PFA Ependymoma. Cell 2024, 187, 4926–4945.e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antin, C.; Tauziède-Espariat, A.; Debily, M.-A.; Castel, D.; Grill, J.; Pagès, M.; Ayrault, O.; Chrétien, F.; Gareton, A.; Andreiuolo, F.; et al. EZHIP Is a Specific Diagnostic Biomarker for Posterior Fossa Ependymomas, Group PFA and Diffuse Midline Gliomas H3-WT with EZHIP Overexpression. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2020, 8, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castel, D.; Kergrohen, T.; Tauziède-Espariat, A.; Mackay, A.; Ghermaoui, S.; Lechapt, E.; Pfister, S.M.; Kramm, C.M.; Boddaert, N.; Blauwblomme, T.; et al. Histone H3 Wild-Type DIPG/DMG Overexpressing EZHIP Extend the Spectrum Diffuse Midline Gliomas with PRC2 Inhibition beyond H3-K27M Mutation. Acta Neuropathol. 2020, 139, 1109–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jawhar, W.; Danieau, G.; Annett, A.; Ishii, T.; Bajic, A.; Castillo-Orozco, A.; Krug, B.; Faucher-Jabado, Y.; Seyedmoomenkashi, J.; Saquib, M.; et al. Aberrant EZHIP Expression Drives Tumorigenesis in Osteosarcoma. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 6752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, P.; Ma, D.; Xu, M. Nested Genes in the Human Genome. Genomics 2005, 86, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzybowska, E.A. Human Intronless Genes: Functional Groups, Associated Diseases, Evolution, and mRNA Processing in Absence of Splicing. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012, 424, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, A.J.G.; Caballero, O.L.; Jungbluth, A.; Chen, Y.-T.; Old, L.J. Cancer/Testis Antigens, Gametogenesis and Cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2005, 5, 615–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenseit, A.; Camgöz, A.; Pfister, S.M.; Kool, M. EZHIP: A New Piece of the Puzzle towards Understanding Pediatric Posterior Fossa Ependymoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2021, 143, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasheminasabgorji, E.; Chen, H.-M.; Gatesman, T.A.; Younes, S.T.; Nobles, G.A.; Jaryani, F.; Mao, H.; Yu, K.; Deneen, B.; Yong, W.; et al. EZHIP Boosts Neuronal-like Synaptic Gene Programs and Depresses Polyamine Metabolism. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2025, 13, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GTEx Portal. Available online: https://www.gtexportal.org/home/gene/EZHIP#geneExpression (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Cardoso-Moreira, M.; Halbert, J.; Valloton, D.; Velten, B.; Chen, C.; Shao, Y.; Liechti, A.; Ascenção, K.; Rummel, C.; Ovchinnikova, S.; et al. Gene Expression across Mammalian Organ Development. Nature 2019, 571, 505–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.W.C.; Dietmann, S.; Irie, N.; Leitch, H.G.; Floros, V.I.; Bradshaw, C.R.; Hackett, J.A.; Chinnery, P.F.; Surani, M.A. A Unique Gene Regulatory Network Resets the Human Germline Epigenome for Development. Cell 2015, 161, 1453–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, S.J.; Xu, Y.; Lisgo, S.N.; Harkin, L.F.; Copp, A.J.; Gerrelli, D.; Clowry, G.J.; Talbot, A.; Keogh, M.J.; Coxhead, J.; et al. HDBR Expression: A Unique Resource for Global and Individual Gene Expression Studies during Early Human Brain Development. Front. Neuroanat. 2016, 10, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, E.; Danan-Gotthold, M.; Borm, L.E.; Lee, K.W.; Vinsland, E.; Lönnerberg, P.; Hu, L.; Li, X.; He, X.; Andrusivová, Ž.; et al. Comprehensive Cell Atlas of the First-Trimester Developing Human Brain. Science 2023, 382, 6667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhaduri, A.; Sandoval-Espinosa, C.; Otero-Garcia, M.; Oh, I.; Yin, R.; Eze, U.C.; Nowakowski, T.J.; Kriegstein, A.R. An Atlas of Cortical Arealization Identifies Dynamic Molecular Signatures. Nature 2021, 598, 200–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassim, A.; Dun, M.D.; Gallego-Ortega, D.; Valdes-Mora, F. EZHIP’s Role in Diffuse Midline Glioma: Echoes of Oncohistones? Trends Cancer 2024, 10, 1095–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, P.W.S.; Leitch, H.G.; Requena, C.E.; Sun, Z.; Amouroux, R.; Roman-Trufero, M.; Borkowska, M.; Terragni, J.; Vaisvila, R.; Linnett, S.; et al. Epigenetic Reprogramming Enables the Transition from Primordial Germ Cell to Gonocyte. Nature 2018, 555, 392–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UniProt. Available online: https://www.uniprot.org/uniprotkb/Q86X51/entry (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Mendenhall, E.M.; Koche, R.P.; Truong, T.; Zhou, V.W.; Issac, B.; Chi, A.S.; Ku, M.; Bernstein, B.E. GC-Rich Sequence Elements Recruit PRC2 in Mammalian ES Cells. PLoS Genet. 2010, 6, e1001244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margueron, R.; Reinberg, D. The Polycomb Complex PRC2 and Its Mark in Life. Nature 2011, 469, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comet, I.; Riising, E.M.; Leblanc, B.; Helin, K. Maintaining Cell Identity: PRC2-Mediated Regulation of Transcription and Cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2016, 16, 803–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piunti, A.; Hashizume, R.; Morgan, M.A.; Bartom, E.T.; Horbinski, C.M.; Marshall, S.A.; Rendleman, E.J.; Ma, Q.; Takahashi, Y.-H.; Woodfin, A.R.; et al. Therapeutic Targeting of Polycomb and BET Bromodomain Proteins in Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Gliomas. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parreno, V.; Martinez, A.-M.; Cavalli, G. Mechanisms of Polycomb Group Protein Function in Cancer. Cell Res. 2022, 32, 231–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krug, B.; Harutyunyan, A.S.; Deshmukh, S.; Jabado, N. Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 in the Driver’s Seat of Childhood and Young Adult Brain Tumours. Trends Cell Biol. 2021, 31, 814–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawata, K.; Chapman, O.S.; Narumi, S.; Kawauchi, D. Epigenetic Modifications and Their Roles in Pediatric Brain Tumor Formation: Emerging Insights from Chromatin Dysregulation. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1569548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CXorf67 Result Summary|BioGRID. Available online: https://thebiogrid.org/131086/table/homo-sapiens/cxorf67.html (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Berlandi, J.; Chaouch, A.; De Jay, N.; Tegeder, I.; Thiel, K.; Shirinian, M.; Kleinman, C.L.; Jeibmann, A.; Lasko, P.; Jabado, N.; et al. Identification of Genes Functionally Involved in the Detrimental Effects of Mutant Histone H3.3-K27M in Drosophila Melanogaster. Neuro Oncol. 2019, 21, 628–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamanishi, E.T.; Dang, D.; Venneti, S. Aberrant Histone Modifications in Pediatric Brain Tumors. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1587157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pajtler, K.W.; Witt, H.; Sill, M.; Jones, D.T.W.; Hovestadt, V.; Kratochwil, F.; Wani, K.; Tatevossian, R.; Punchihewa, C.; Johann, P.; et al. Molecular Classification of Ependymal Tumors across All CNS Compartments, Histopathological Grades, and Age Groups. Cancer Cell 2015, 27, 728–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richard Albert, J.; Urli, T.; Monteagudo-Sánchez, A.; Le Breton, A.; Sultanova, A.; David, A.; Scarpa, M.; Schulz, M.; Greenberg, M.V.C. DNA Methylation Shapes the Polycomb Landscape during the Exit from Naive Pluripotency. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2025, 32, 346–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, M.A.; Dai, Z.; Locasale, J.W. The Impact of Cellular Metabolism on Chromatin Dynamics and Epigenetics. Nat. Cell Biol. 2017, 19, 1298–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vladoiu, M.C.; El-Hamamy, I.; Donovan, L.K.; Farooq, H.; Holgado, B.L.; Sundaravadanam, Y.; Ramaswamy, V.; Hendrikse, L.D.; Kumar, S.; Mack, S.C.; et al. Childhood Cerebellar Tumours Mirror Conserved Fetal Transcriptional Programs. Nature 2019, 572, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C.; Sweha, S.R.; Pratt, D.; Tamrazi, B.; Panwalkar, P.; Banda, A.; Bayliss, J.; Hawes, D.; Yang, F.; Lee, H.-J.; et al. Integrated Metabolic and Epigenomic Reprograming by H3K27M Mutations in Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Gliomas. Cancer Cell 2020, 38, 334–349.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, J.R.; Jung, I.; Selvaraj, S.; Shen, Y.; Antosiewicz-Bourget, J.E.; Lee, A.Y.; Ye, Z.; Kim, A.; Rajagopal, N.; Xie, W.; et al. Chromatin Architecture Reorganization during Stem Cell Differentiation. Nature 2015, 518, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Carroll, D.; Erhardt, S.; Pagani, M.; Barton, S.C.; Surani, M.A.; Jenuwein, T. The Polycomb-Group Gene Ezh2 Is Required for Early Mouse Development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001, 21, 4330–4336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Q.; Kumar, A.; Wu, D.; Zhou, J. Targeting EED as a Key PRC2 Complex Mediator toward Novel Epigenetic Therapeutics. Drug Discov. Today 2024, 29, 103986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krabbenhoft, S.D.; Masuda, T.E.; Kaur, Y.; Do, T.J.; Jain, S.U.; Lewis, P.W.; Harrison, M.M. Novel Modifiers of Oncoprotein-Mediated Polycomb Inhibition in Drosophila Melanogaster. Genetics 2025, 231, iyaf193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EPEN-20. EZHIP/CATACOMB COOPERATES WITH PDGF-A AND P53 LOSS TO GENERATE A GENETICALLY ENGINEERED MOUSE MODEL FOR POSTERIOR FOSSA A EPENDYMOMA|Neuro-Oncology|Oxford Academic. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/neuro-oncology/article/22/Supplement_3/iii311/6018762 (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Funato, K.; Major, T.; Lewis, P.W.; Allis, C.D.; Tabar, V. Use of Human Embryonic Stem Cells to Model Pediatric Gliomas with H3.3K27M Histone Mutation. Science 2014, 346, 1529–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagaraja, S.; Quezada, M.A.; Gillespie, S.M.; Arzt, M.; Lennon, J.J.; Woo, P.J.; Hovestadt, V.; Kambhampati, M.; Filbin, M.G.; Suva, M.L.; et al. Histone Variant and Cell Context Determine H3K27M Reprogramming of the Enhancer Landscape and Oncogenic State. Mol. Cell 2019, 76, 965–980.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haag, D.; Mack, N.; Benites Goncalves da Silva, P.; Statz, B.; Clark, J.; Tanabe, K.; Sharma, T.; Jäger, N.; Jones, D.T.W.; Kawauchi, D.; et al. H3.3-K27M Drives Neural Stem Cell-Specific Gliomagenesis in a Human iPSC-Derived Model. Cancer Cell 2021, 39, 407–422.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesseling, P.; Capper, D.; Reifenberger, G.; Sarkar, C.; Hawkins, C.; Perry, A.; Kleinschmidt-DeMasters, B.; Komori, T.; Paulus, W.; Santosh, V.; et al. cIMPACT-NOW Update 11: Proposal on Adaptation of Diagnostic Criteria for IDH- and H3-Wildtype Diffuse High-Grade Gliomas and for Posterior Fossa Ependymal Tumors. Brain Pathol. Zur. Switz. 2025, 36, e70035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, K.Y.; Lee, K.; Shim, Y.; Park, J.W.; Kim, H.; Kang, J.; Won, J.K.; Kim, S.-K.; Phi, J.H.; Park, C.-K.; et al. Molecular Subtyping of Ependymoma and Prognostic Impact of Ki-67. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2022, 39, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gojo, J.; Englinger, B.; Jiang, L.; Hübner, J.M.; Shaw, M.L.; Hack, O.A.; Madlener, S.; Kirchhofer, D.; Liu, I.; Pyrdol, J.; et al. Single-Cell RNA-Seq Reveals Cellular Hierarchies and Impaired Developmental Trajectories in Pediatric Ependymoma. Cancer Cell 2020, 38, 44–59.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Holsten, T.; Börnigen, D.; Frank, S.; Mawrin, C.; Glatzel, M.; Schüller, U. Ependymoma Relapse Goes along with a Relatively Stable Epigenome, but a Severely Altered Tumor Morphology. Brain Pathol. Zur. Switz. 2021, 31, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryall, S.; Guzman, M.; Elbabaa, S.K.; Luu, B.; Mack, S.C.; Zapotocky, M.; Taylor, M.D.; Hawkins, C.; Ramaswamy, V. H3 K27M Mutations Are Extremely Rare in Posterior Fossa Group A Ependymoma. Childs Nerv. Syst. ChNS Off. J. Int. Soc. Pediatr. Neurosurg. 2017, 33, 1047–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castel, D.; Philippe, C.; Calmon, R.; Le Dret, L.; Truffaux, N.; Boddaert, N.; Pagès, M.; Taylor, K.R.; Saulnier, P.; Lacroix, L.; et al. Histone H3F3A and HIST1H3B K27M Mutations Define Two Subgroups of Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Gliomas with Different Prognosis and Phenotypes. Acta Neuropathol. 2015, 130, 815–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pratt, D.; Quezado, M.; Abdullaev, Z.; Hawes, D.; Yang, F.; Garton, H.J.L.; Judkins, A.R.; Mody, R.; Chinnaiyan, A.; Aldape, K.; et al. Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma-like Tumor with EZHIP Expression and Molecular Features of PFA Ependymoma. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2020, 8, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alturkustani, M.; Cotter, J.A.; Mahabir, R.; Hawes, D.; Koschmann, C.; Venneti, S.; Judkins, A.R.; Szymanski, L.J. Autopsy Findings of Previously Described Case of Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma-like Tumor with EZHIP Expression and Molecular Features of PFA Ependymoma. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2021, 9, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauziède-Espariat, A.; Métais, A.; Mariet, C.; Castel, D.; Grill, J.; Saffroy, R.; Hasty, L.; Dangouloff-Ros, V.; Boddaert, N.; Benichi, S.; et al. The Pontine Diffuse Midline Glioma, EGFR-Subtype with Ependymal Features: Yet Another Face of Diffuse Midline Glioma, H3K27-Altered. Brain Pathol. Zur. Switz. 2024, 34, e13181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castel, D.; Philippe, C.; Kergrohen, T.; Sill, M.; Merlevede, J.; Barret, E.; Puget, S.; Sainte-Rose, C.; Kramm, C.M.; Jones, C.; et al. Transcriptomic and Epigenetic Profiling of “diffuse Midline Gliomas, H3 K27M-Mutant” Discriminate Two Subgroups Based on the Type of Histone H3 Mutated and Not Supratentorial or Infratentorial Location. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2018, 6, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findlay, I.J.; De Iuliis, G.N.; Duchatel, R.J.; Jackson, E.R.; Vitanza, N.A.; Cain, J.E.; Waszak, S.M.; Dun, M.D. Pharmaco-Proteogenomic Profiling of Pediatric Diffuse Midline Glioma to Inform Future Treatment Strategies. Oncogene 2022, 41, 461–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajuyah, P.; Mayoh, C.; Lau, L.M.S.; Barahona, P.; Wong, M.; Chambers, H.; Valdes-Mora, F.; Senapati, A.; Gifford, A.J.; D’Arcy, C.; et al. Histone H3-Wild Type Diffuse Midline Gliomas with H3K27me3 Loss Are a Distinct Entity with Exclusive EGFR or ACVR1 Mutation and Differential Methylation of Homeobox Genes. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 3775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Wang, B.; Han, B.; Li, Z.; Liu, X.; Liu, P. Insights From H3-Wildtype Diffuse Midline Glioma With EZHIP Overexpression. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2025, 49, 748–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griesinger, A.M.; Calzadilla, A.J.; Grimaldo, E.; Donson, A.M.; Amani, V.; Pierce, A.M.; Steiner, J.; Kargar, S.; Serkova, N.J.; Bertrand, K.C.; et al. Development of Chromosome 1q+ Specific Treatment for Highest Risk Pediatric Posterior Fossa Ependymoma. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2024, 30, 1544–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sievers, P.; Sill, M.; Schrimpf, D.; Stichel, D.; Reuss, D.E.; Sturm, D.; Hench, J.; Frank, S.; Krskova, L.; Vicha, A.; et al. A Subset of Pediatric-Type Thalamic Gliomas Share a Distinct DNA Methylation Profile, H3K27me3 Loss and Frequent Alteration of EGFR. Neuro Oncol. 2021, 23, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.F.; Hu, X.M.; Du, Z.G.; Wang, Y.; Tang, F.; Xiong, J. The value of CXorf67 and H3K27me3 for diagnosing germ cell tumors in central nervous system. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi 2022, 51, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowman, R.L.; Wang, Q.; Carro, A.; Verhaak, R.G.W.; Squatrito, M. GlioVis Data Portal for Visualization and Analysis of Brain Tumor Expression Datasets. Neuro Oncol. 2017, 19, 139–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Northcott, P.A.; Shih, D.J.H.; Peacock, J.; Garzia, L.; Morrissy, A.S.; Zichner, T.; Stütz, A.M.; Korshunov, A.; Reimand, J.; Schumacher, S.E.; et al. Subgroup-Specific Structural Variation across 1000 Medulloblastoma Genomes. Nature 2012, 488, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hikmet, F.; Rassy, M.; Backman, M.; Méar, L.; Mattsson, J.S.M.; Djureinovic, D.; Botling, J.; Brunnström, H.; Micke, P.; Lindskog, C. Expression of Cancer-Testis Antigens in the Immune Microenvironment of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Mol. Oncol. 2023, 17, 2603–2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujar, H.; Mehta, A.; Li, H.-T.; Tsai, Y.C.; Qiu, X.; Weisenberger, D.J.; Jasiulionis, M.G.; In, G.K.; Liang, G. Characterizing DNA Methylation Signatures and Their Potential Functional Roles in Merkel Cell Carcinoma. Genome Med. 2021, 13, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, M.-A.; Drouin, A.; Mouchard, A.; Durand, L.; Esnault, C.; Berthon, P.; Tallet, A.; Le Corre, Y.; Hainaut-Wierzbicka, E.; Blom, A.; et al. Distinct Regulation of EZH2 and Its Repressive H3K27me3 Mark in Polyomavirus-Positive and -Negative Merkel Cell Carcinoma. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2023, 143, 1937–1946.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busam, K.J.; Pulitzer, M.P.; Coit, D.C.; Arcila, M.; Leng, D.; Jungbluth, A.A.; Wiesner, T. Reduced H3K27me3 Expression in Merkel Cell Polyoma Virus-Positive Tumors. Mod. Pathol. Off. J. US Can. Acad. Pathol. Inc. 2017, 30, 877–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, R.; Nagarajaram, H.A. Intrinsically Disordered Proteins: An Overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uversky, V.N. How to Drug a Cloud? Targeting Intrinsically Disordered Proteins. Pharmacol. Rev. 2024, 77, 100016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robustelli, P. Extending Computational Protein Design to Intrinsically Disordered Proteins. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadr3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesaga, M.; Frigolé-Vivas, M.; Salvatella, X. Intrinsically Disordered Proteins and Biomolecular Condensates as Drug Targets. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2021, 62, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazar, T.; Connor, A.; DeLisle, C.F.; Burger, V.; Tompa, P. Targeting Protein Disorder: The next Hurdle in Drug Discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2025, 24, 743–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Q.; Wang, H.; Xie, J.; Wang, L.; Mu, J.; Li, J.; Ren, Y.; Lai, L. Computer-Aided Drug Discovery for Undruggable Targets. Chem. Rev. 2025, 125, 6309–6365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, R.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, J.; Cong, Q. Recent Progress and Future Challenges in Structure-Based Protein-Protein Interaction Prediction. Mol. Ther. J. Am. Soc. Gene Ther. 2025, 33, 2252–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinterndorfer, M.; Spiteri, V.A.; Ciulli, A.; Winter, G.E. Targeted Protein Degradation for Cancer Therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2025, 25, 493–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetma, V.; O’Connor, S.; Ciulli, A. Development of PROTAC Degrader Drugs for Cancer. Annu. Rev. Cancer Biol. 2025, 9, 119–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, G.; Zhang, X.; Bai, R.; Yuan, D.; Gao, D.; He, Q.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Kou, J.; et al. Antitumor Effect of Anti-c-Myc Aptamer-Based PROTAC for Degradation of the c-Myc Protein. Adv. Sci. Weinh. Baden Wurtt. Ger. 2024, 11, e2309639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, S.R.; Chamakuri, S.; Trostle, A.J.; Chen, H.; Liu, Z.; Jian, A.; Wang, J.; Malovannaya, A.; Young, D.W. MYC-Targeting PROTACs Lead to Bimodal Degradation and N-Terminal Truncation. ACS Chem. Biol. 2025, 20, 896–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Sun, C.; Huang, M.; Tang, X.; Pi, L.; Li, C. Exploring Degradation of Intrinsically Disordered Protein Yes-Associated Protein Induced by Proteolysis TArgeting Chimeras. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 15168–15198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFranciscis, V.; Amabile, G.; Kortylewski, M. Clinical Applications of Oligonucleotides for Cancer Therapy. Mol. Ther. J. Am. Soc. Gene Ther. 2025, 33, 2705–2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, D.; Tang, L.; Zhou, B.; Yang, L. Landscape of Small Nucleic Acid Therapeutics: Moving from the Bench to the Clinic as next-Generation Medicines. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Yang, L.; Liu, Y.H.; Wilkinson, J.E.; Krainer, A.R. Antisense Oligonucleotide Therapy for H3.3K27M Diffuse Midline Glioma. Sci. Transl. Med. 2023, 15, eadd8280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venneti, S.; Kawakibi, A.R.; Ji, S.; Waszak, S.M.; Sweha, S.R.; Mota, M.; Pun, M.; Deogharkar, A.; Chung, C.; Tarapore, R.S. Clinical Efficacy of ONC201 in H3K27M-Mutant Diffuse Midline Gliomas Is Driven by Disruption of Integrated Metabolic and Epigenetic Pathways. Cancer Discov. 2023, 13, 2370–2393, Erratum in Cancer Discov. 2025, 15, 657. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-25-0208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lulla, R.R.; Buxton, A.; Krailo, M.D.; Lazow, M.A.; Boue, D.R.; Leach, J.L.; Lin, T.; Geller, J.I.; Kumar, S.S.; Nikiforova, M.N.; et al. Vorinostat, Temozolomide or Bevacizumab with Irradiation and Maintenance BEV/TMZ in Pediatric High-Grade Glioma: A Children’s Oncology Group Study. Neuro Oncol. Adv. 2024, 6, vdae035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Carlo, D.; Annereau, M.; Vignes, M.; Denis, L.; Epaillard, N.; Dumont, S.; Guyon, D.; Rieutord, A.; Jacobs, S.; Salomon, V.; et al. Real Life Data of ONC201 (Dordaviprone) in Pediatric and Adult H3K27-Altered Recurrent Diffuse Midline Glioma: Results of an International Academia-Driven Compassionate Use Program. Eur. J. Cancer Oxf. Engl. 2025, 216, 115165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.; Gill, R.; Bull, K.S. Does a Bevacizumab-Based Regime Have a Role in the Treatment of Children with Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma? A Systematic Review. Neuro Oncol. Adv. 2022, 4, vdac100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monje, M.; Cooney, T.; Glod, J.; Huang, J.; Peer, C.J.; Faury, D.; Baxter, P.; Kramer, K.; Lenzen, A.; Robison, N.J.; et al. Phase I Trial of Panobinostat in Children with Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma: A Report from the Pediatric Brain Tumor Consortium (PBTC-047). Neuro Oncol. 2023, 25, 2262–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majzner, R.G.; Ramakrishna, S.; Yeom, K.W.; Patel, S.; Chinnasamy, H.; Schultz, L.M.; Richards, R.M.; Jiang, L.; Barsan, V.; Mancusi, R.; et al. GD2-CAR T Cell Therapy for H3K27M-Mutated Diffuse Midline Gliomas. Nature 2022, 603, 934–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, B.; Finn, R.S.; Turner, N.C. Treating Cancer with Selective CDK4/6 Inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 13, 417–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, F.; Weissmann, S.; Leblanc, B.; Pandey, D.P.; Højfeldt, J.W.; Comet, I.; Zheng, C.; Johansen, J.V.; Rapin, N.; Porse, B.T.; et al. EZH2 Is a Potential Therapeutic Target for H3K27M-Mutant Pediatric Gliomas. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, R.; Du, W.; Guo, W. EZH2: A Novel Target for Cancer Treatment. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 13, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mack, S.C.; Witt, H.; Piro, R.M.; Gu, L.; Zuyderduyn, S.; Stütz, A.M.; Wang, X.; Gallo, M.; Garzia, L.; Zayne, K.; et al. Epigenomic Alterations Define Lethal CIMP-Positive Ependymomas of Infancy. Nature 2014, 506, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhar, S.; Gadd, S.; Patel, P.; Vaynshteyn, J.; Raju, G.P.; Hashizume, R.; Brat, D.J.; Becher, O.J. A Tumor Suppressor Role for EZH2 in Diffuse Midline Glioma Pathogenesis. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2022, 10, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krug, K.; Mertins, P.; Zhang, B.; Hornbeck, P.; Raju, R.; Ahmad, R.; Szucs, M.; Mundt, F.; Forestier, D.; Jane-Valbuena, J.; et al. A Curated Resource for Phosphosite-Specific Signature Analysis. Mol. Cell. Proteomics MCP 2019, 18, 576–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, S.C.; Pajtler, K.W.; Chavez, L.; Okonechnikov, K.; Bertrand, K.C.; Wang, X.; Erkek, S.; Federation, A.; Song, A.; Lee, C.; et al. Therapeutic Targeting of Ependymoma as Informed by Oncogenic Enhancer Profiling. Nature 2018, 553, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filbin, M.; Monje, M. Developmental Origins and Emerging Therapeutic Opportunities for Childhood Cancer. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathikonda, S.; Amirmahani, F.; Mathew, D.; Muthukrishnan, S.D. Histone Acetyltransferases as Promising Therapeutic Targets in Glioblastoma Resistance. Cancer Lett. 2024, 604, 217269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Yang, Y.; Buettner, R.; Rosen, S.T. Targeting the Methionine-Methionine Adenosyl Transferase 2A-S-Adenosyl Methionine Axis for Cancer Therapy. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2022, 34, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, A.B.; Nobre, L.; Das, A.; Milos, S.; Bianchi, V.; Johnson, M.; Fernandez, N.R.; Stengs, L.; Ryall, S.; Ku, M.; et al. Immuno-Oncologic Profiling of Pediatric Brain Tumors Reveals Major Clinical Significance of the Tumor Immune Microenvironment. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaBelle, J.J.; Haase, R.D.; Beck, A.; Haase, J.; Jiang, L.; Oliveira de Biagi, C.A.; Neyazi, S.; Englinger, B.; Liu, I.; Trissal, M.; et al. Dissecting the Immune Landscape in Pediatric High-Grade Glioma Reveals Cell State Changes under Therapeutic Pressure. Cell Rep. Med. 2025, 6, 102095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetsika, E.-K.; Katsianou, M.A.; Sarantis, P.; Palamaris, K.; Papavassiliou, A.G.; Piperi, C. Pediatric Gliomas Immunity Challenges and Immunotherapy Advances. Cancer Lett. 2025, 618, 217640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baulu, E.; Gardet, C.; Chuvin, N.; Depil, S. TCR-Engineered T Cell Therapy in Solid Tumors: State of the Art and Perspectives. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadf3700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seblani, M.; Zannikou, M.; Duffy, J.T.; Joshi, T.; Levine, R.N.; Thakur, A.; Puigdelloses-Vallcorba, M.; Horbinski, C.M.; Miska, J.; Hambardzumyan, D.; et al. IL13RA2-Integrated Genetically Engineered Mouse Model Allows for CAR T Cells Targeting Pediatric High-Grade Gliomas. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2025, 13, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.W.; Santomasso, B.D.; Locke, F.L.; Ghobadi, A.; Turtle, C.J.; Brudno, J.N.; Maus, M.V.; Park, J.H.; Mead, E.; Pavletic, S.; et al. ASTCT Consensus Grading for Cytokine Release Syndrome and Neurologic Toxicity Associated with Immune Effector Cells. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. J. Am. Soc. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019, 25, 625–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cell Line | EZHIP Status | H3K27me3 | H3K27ac | H3K27me3 Genome Distribution | OMICS | Functional Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EZHIP-expressing cells | ||||||

| DAOY (MB) 1 [4] | KO 8 | ↑ | ↓ | proliferation ↓ | ||

| U2OS (OS) 2 [18,33] | KO | ↑ | ↓ | spreading from CpGi 10 | 500 genes (most down) | tumorigenicity ↑ SC 11-like phenotype |

| mGCs 3 [18] | KO | ↓ | = | 125 genes (most down) | ||

| EZHIP-negative cells | ||||||

| MG63 (OS) [33] | OE 9 | ↓ | restricted at CpGi | tumorigenicity ↑ SC-like phenotype | ||

| KOSH (OS) [33] | OE | ↓ | restricted at CpGi | tumorigenicity ↑ SC-like phenotype | ||

| MSCs 4 [33] | OE | ↓ | proliferation ↑ no tumorigenicity altered differentiation | |||

| HEK293T [21,22,58] | OE | ↓ | ↑, = | 200 genes (most up) | ||

| hNSCs 5 [28,30,38] | OE | ↓ | ↑ | 2800 genes metabolomics | proliferation ↑ | |

| mNSCs 6 [26] | OE | ↑ | ↑ | 2400 proteins | proliferation ↑ differentiation ↓ | |

| MEFs 7 [22] | OE | ↓ | restricted at CpGi | 500 genes (most up) | ||

| S2 cells (D. melanogaster) [10] | OE | ↓ |

| Tumor Type | Expression (%) | EZHIP Role | Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESS | 5% | Co-driver |

|

| NSCLC | 3–11% | Biomarker |

|

| MCC (adult) | 16% | Co-driver |

|

| OS | 20% | Co-driver/biomarker |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Servidei, T.; Gentile, S.; Sgambato, A.; Ruggiero, A. EZHIP in Pediatric Brain Tumors: From Epigenetic Mimicry to Therapeutic Vulnerabilities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 963. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020963

Servidei T, Gentile S, Sgambato A, Ruggiero A. EZHIP in Pediatric Brain Tumors: From Epigenetic Mimicry to Therapeutic Vulnerabilities. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):963. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020963

Chicago/Turabian StyleServidei, Tiziana, Serena Gentile, Alessandro Sgambato, and Antonio Ruggiero. 2026. "EZHIP in Pediatric Brain Tumors: From Epigenetic Mimicry to Therapeutic Vulnerabilities" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 963. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020963

APA StyleServidei, T., Gentile, S., Sgambato, A., & Ruggiero, A. (2026). EZHIP in Pediatric Brain Tumors: From Epigenetic Mimicry to Therapeutic Vulnerabilities. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 963. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020963