FOXO1 Inhibition and FADD Knockdown Have Opposing Effects on Anticancer Drug-Induced Cytotoxicity and p21 Expression in Osteosarcoma Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

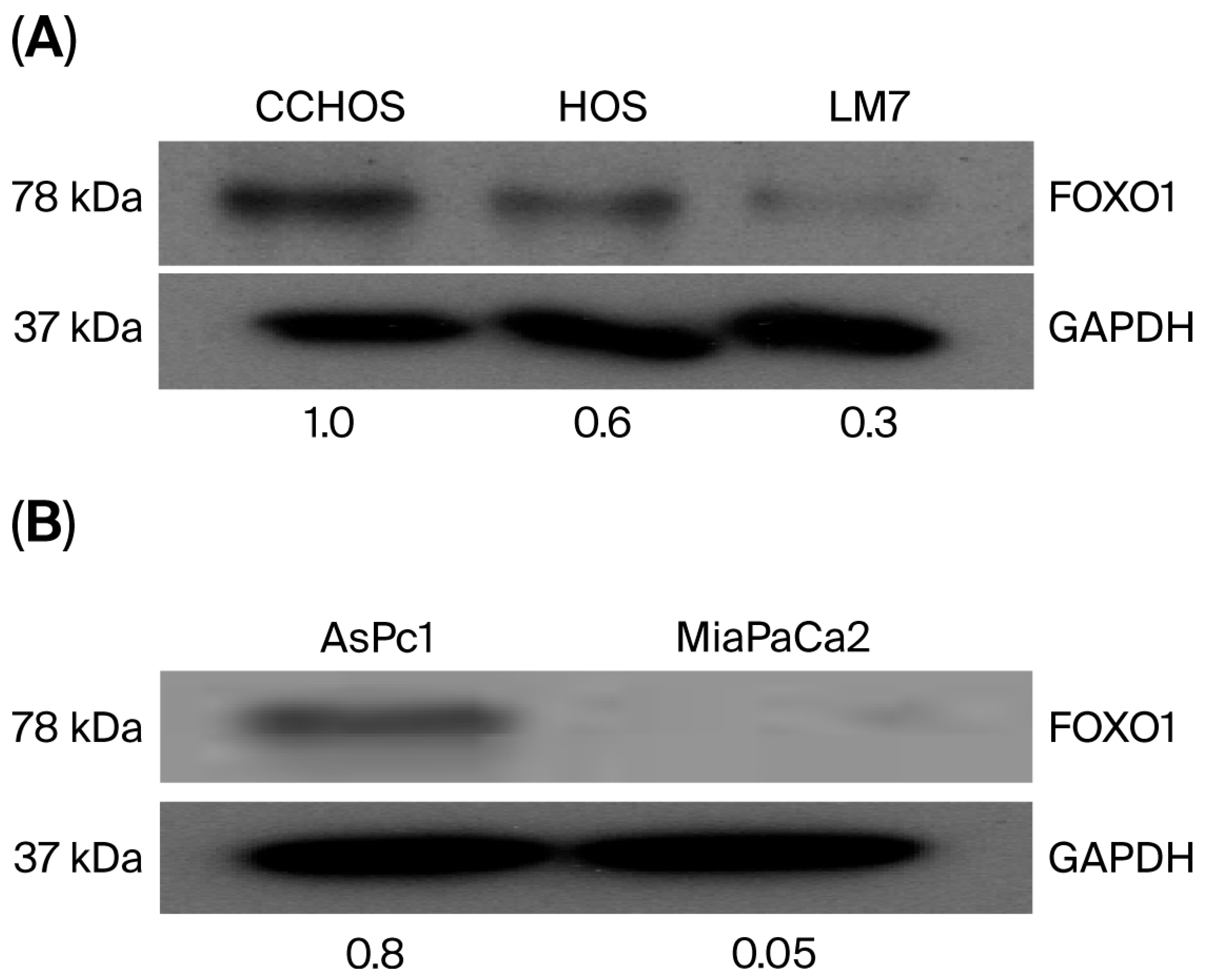

2.1. OS Cells Express Different Basal Levels of FOXO1

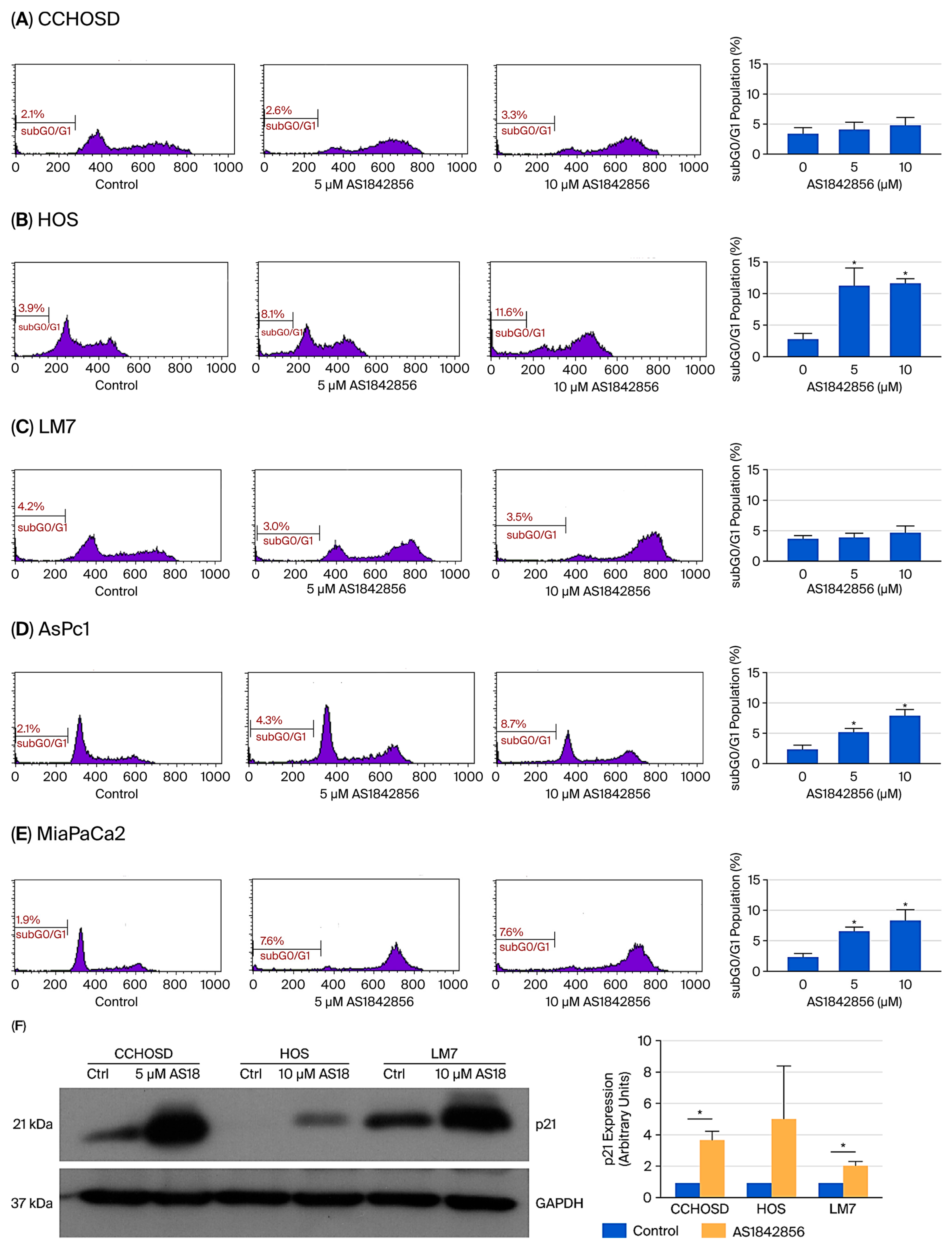

2.2. FOXO1 Inhibition Induces Selective Cell Death and Increases p21 Expression

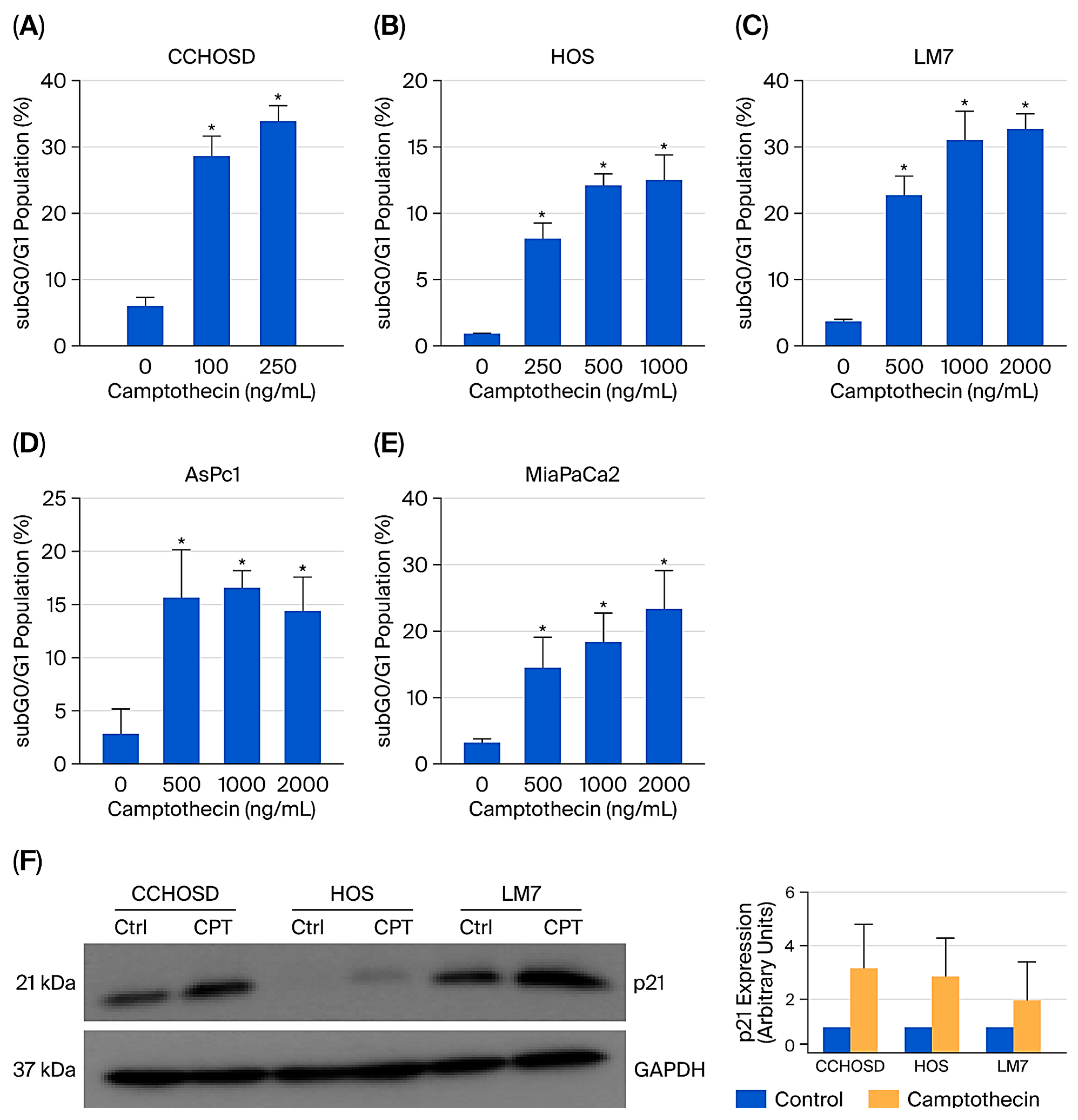

2.3. Camptothecin Induces Significant Cell Death and Increases p21 Expression

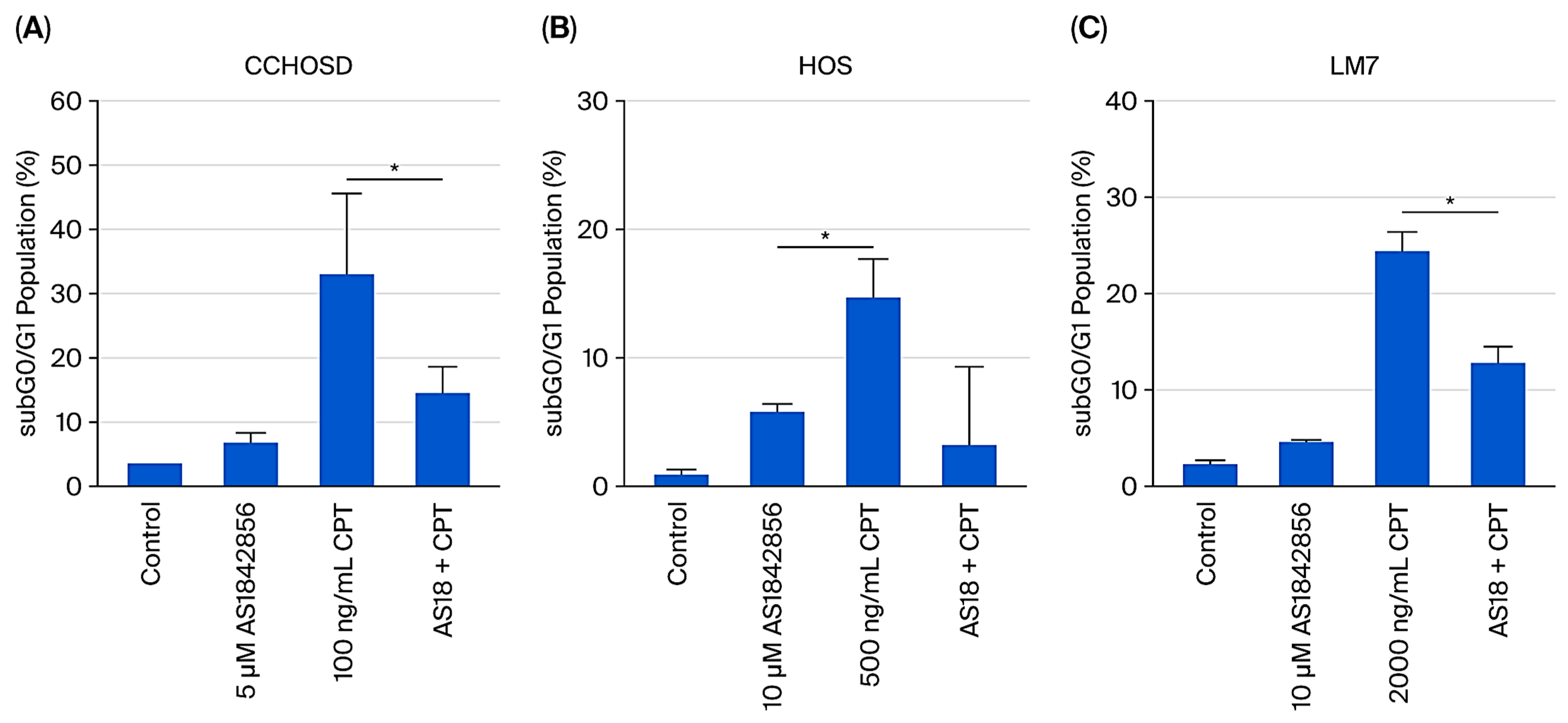

2.4. FOXO1 Inhibition Reverses CPT-Induced Cytotoxicity, and FADD Knockdown Increases CPT-Induced Cytotoxicity

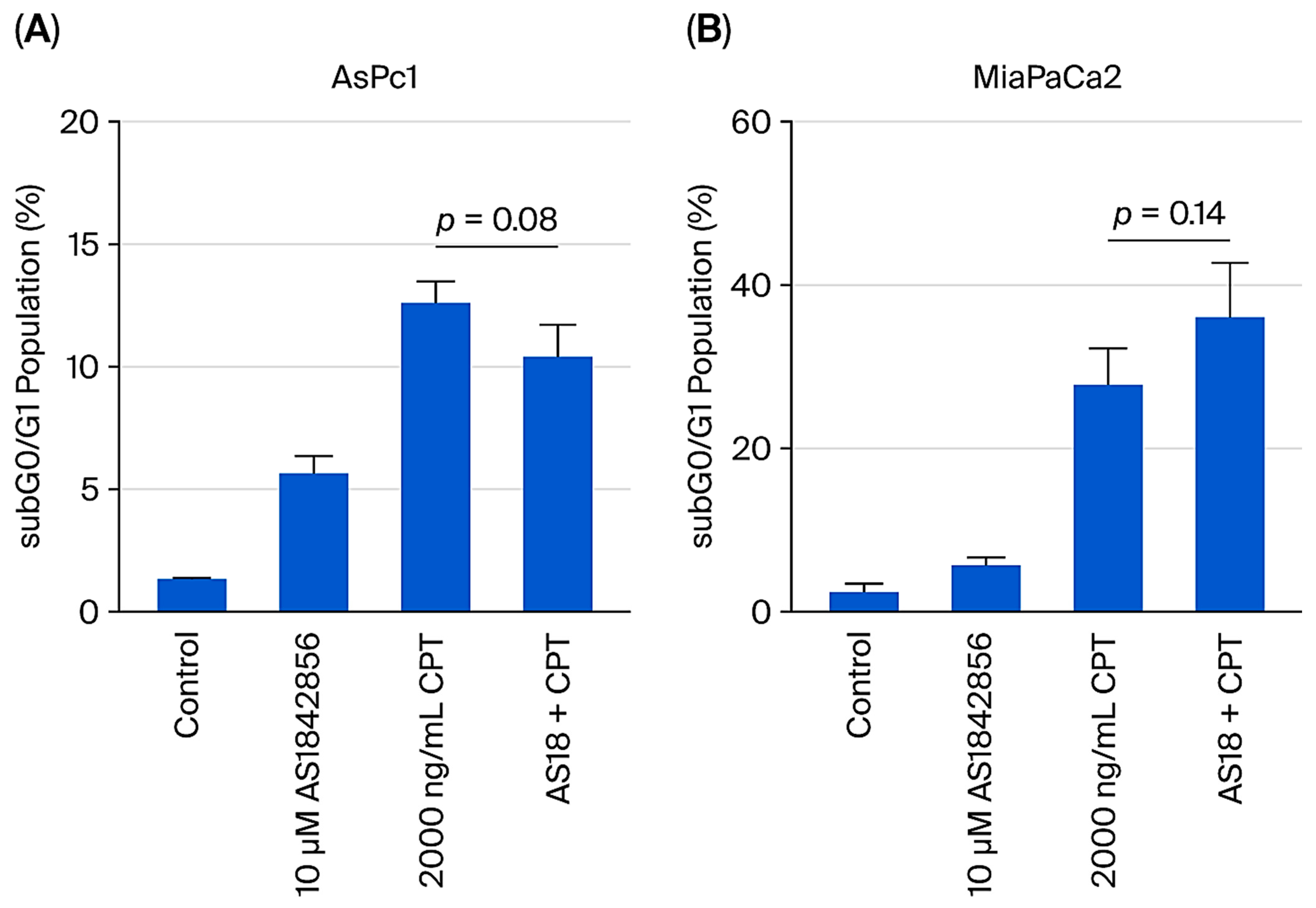

2.5. FOXO1 Inhibition Does Not Reverse CPT-Induced Cytotoxicity in Pancreatic Cancer Cells

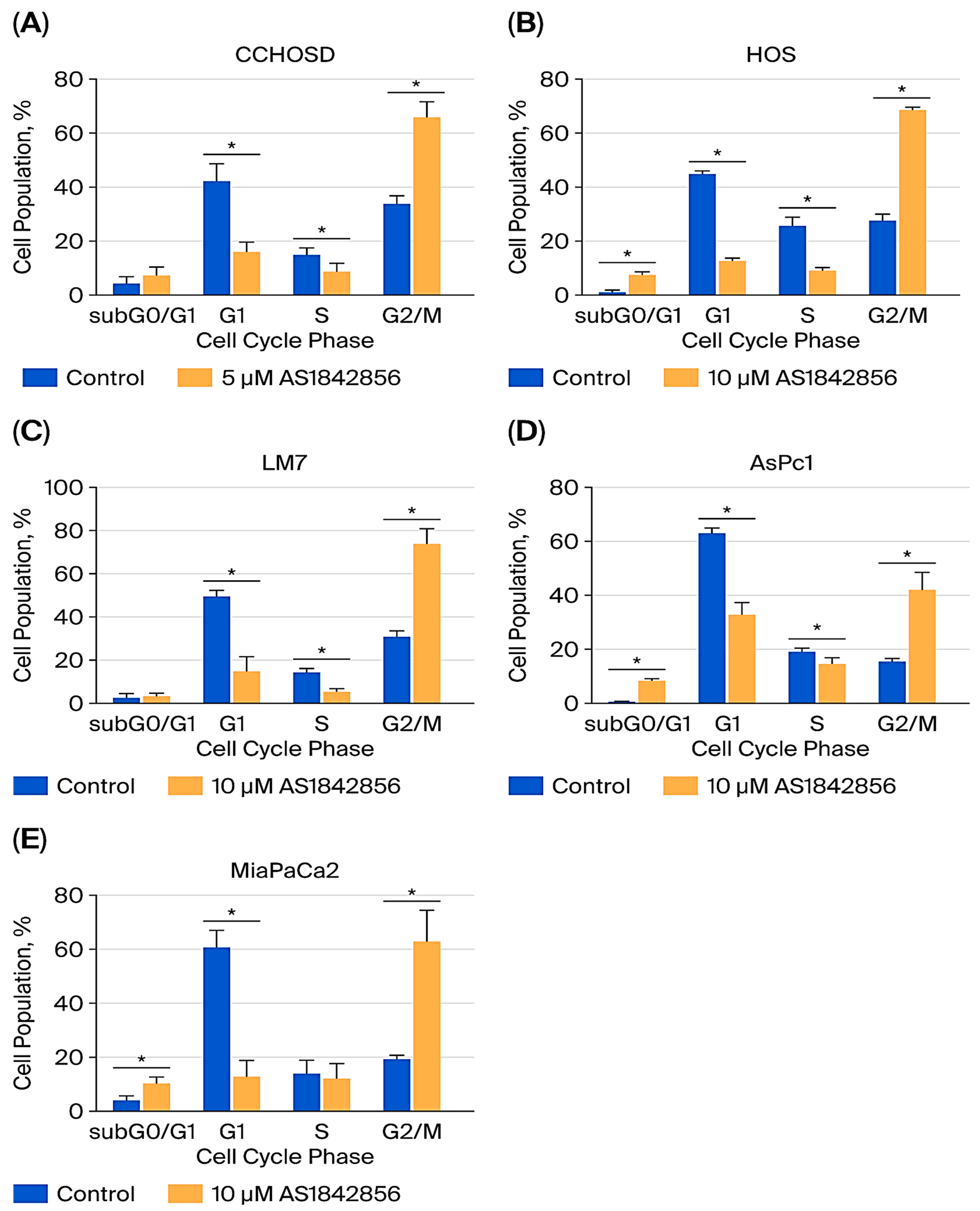

2.6. FOXO1 Inhibition Induces G2/M Cell Cycle Arrest

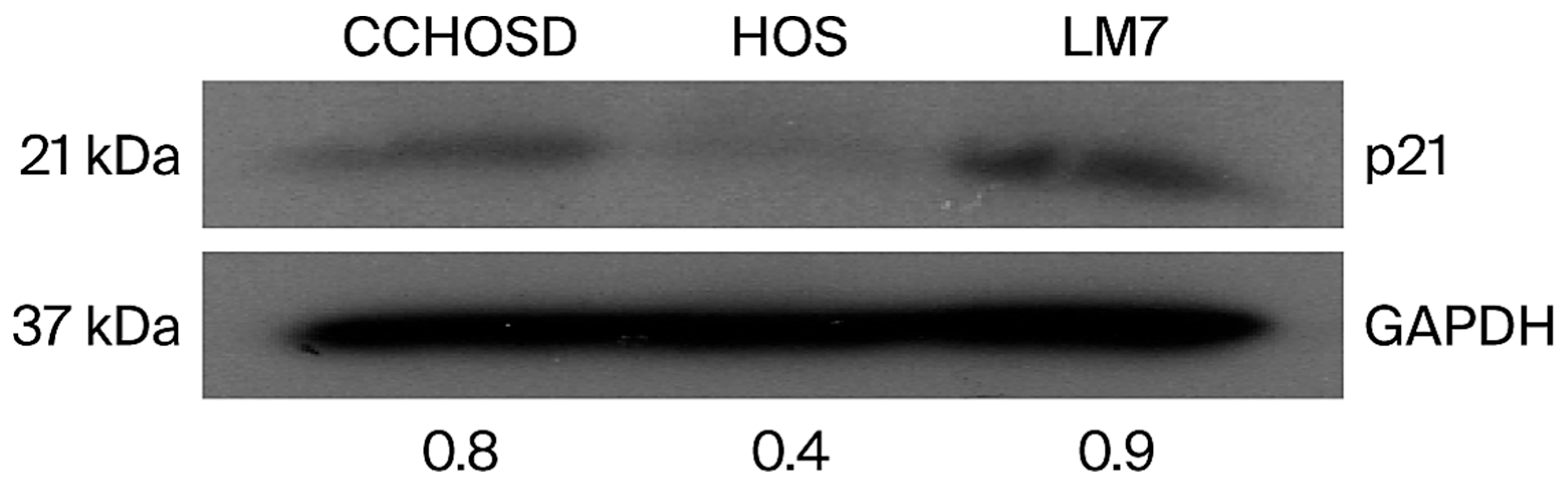

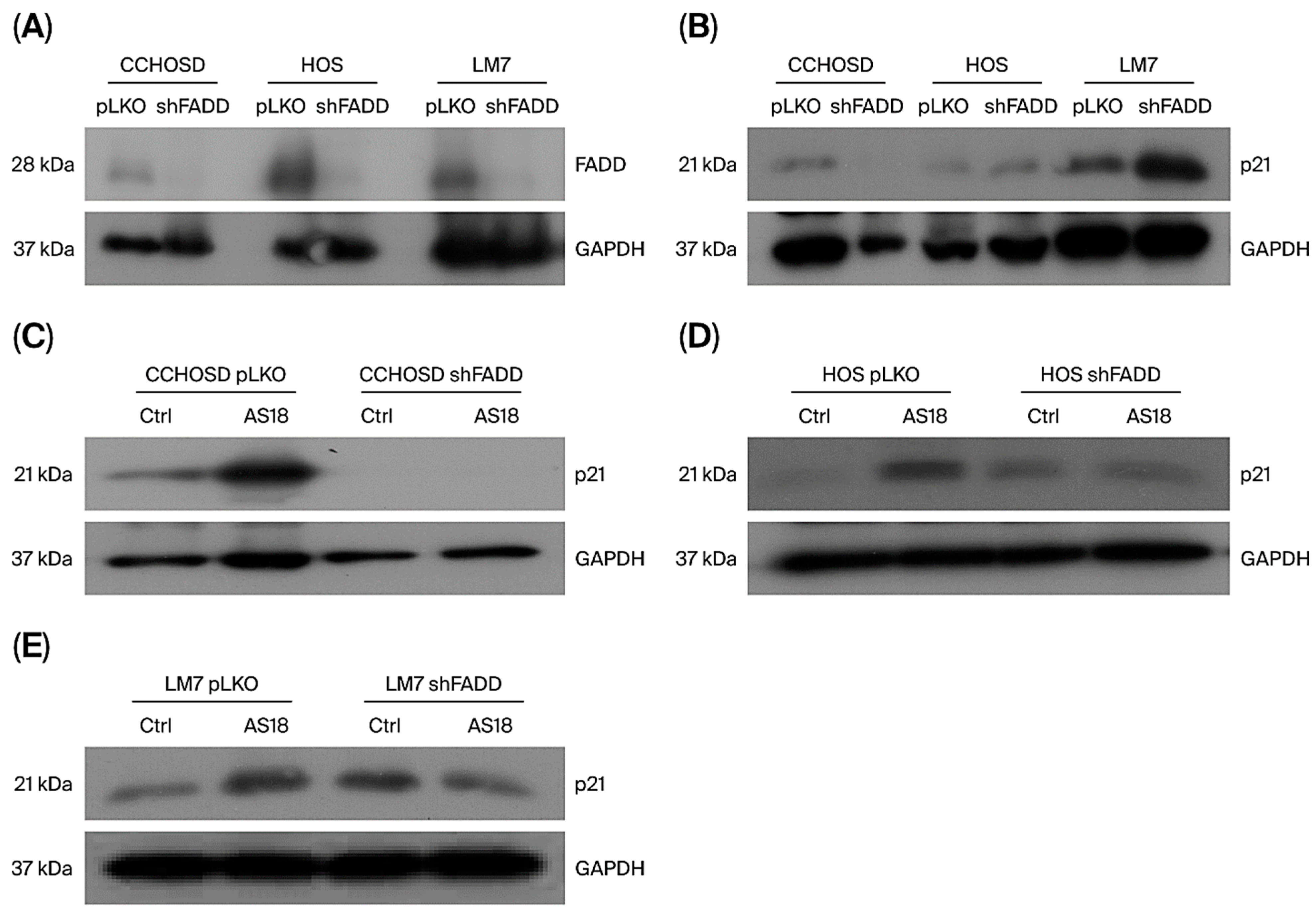

2.7. FADD Knockdown Alters p21 Expression and Reduces FOXO1 Inhibition-Induced p21 Expression

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Lines, Cell Culture, and Reagents

4.2. Cytotoxicity and Cell Cycle Analysis

4.3. Western Blot Analysis

4.4. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FOXO | forkhead box-O |

| FADD | fas-associated death domain |

| CDK | cyclin-dependent kinase |

| CDKI | cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor |

| CPT | camptothecin |

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Wagle, N.S.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rached, M.T.; Kode, A.; Xu, L.; Yoshikawa, Y.; Paik, J.H.; Depinho, R.A.; Kousteni, S. FoxO1 is a positive regulator of bone formation by favoring protein synthesis and resistance to oxidative stress in osteoblasts. Cell Metab. 2010, 11, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Luo, W.; Zhou, F.; Gong, P.; Xiong, Y. The role of FOXO1-mediated autophagy in the regulation of bone formation. Cell Cycle 2023, 22, 829–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, C.C.; Liu, Y.; Thant, L.M.; Pang, J.; Palmer, G.; Alikhani, M. FOXO1, a novel regulator of osteoblast differentiation and skeletogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 31055–31065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.W.; Seo, J.; Jeong, M.; Lee, S.; Song, J. The roles of FADD in extrinsic apoptosis and necroptosis. BNB Rep. 2012, 43, 496–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyo, J.O.; Jang, M.H.; Kwon, Y.K.; Lee, H.J.; Jun, J.I.; Woo, H.N.; Cho, D.H.; Choi, B.; Lee, H.; Kim, J.H.; et al. Essential roles of Atg5 and FADD in autophagic cell death: Dissection of autophagic cell death into vacuole formation and cell death. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 20722–20729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imtiyaz, H.Z.; Rosenberg, S.; Zhang, Y.; Rahman, Z.S.M.; Hou, Y.J.; Manser, T.; Zhang, J. The Fas-associated death domain protein is required for apoptosis and TLR-induced proliferative responses in B cells. J. Immunol. 2006, 176, 6852–6861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awadia, A.; Sitto, M.; Ram, S.; Ji, W.; Liu, Y.; Damani, R.; Ray, D.; Lawrence, T.S.; Galban, C.J.; Cappell, S.D.; et al. The adapter protein FADD provides an alternate pathway for entry into the cell cycle by regulating APC/C-Cdh1 E3 ubiquitin ligase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 299, 104786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, S.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J. FADD deficiency impairs early hematopoiesis in the bone marrow. J. Immunol. 2011, 186, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Liu, Y.; Hammache, K.; He, L.; Zhu, B.; Cheng, W.; Hua, Z.C. The role of FADD in pancreatic cancer cell proliferation and drug resistance. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 13, 1899–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Angelats, M.; Cidlowski, J.A. Molecular evidence for the nuclear localization of FADD. Cell Death Differ. 2003, 10, 791–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, J.W.; Adami, G.R.; Wei, N.; Keyomarsi, K.; Elledge, S.J. The p21 Cdk-interacting protein Cip1 is a potent inhibitor of G1 cyclin-dependent kinases. Cell 1993, 75, 805–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurakazu, I.; Akasaki, Y.; Hayashida, M.; Tsushima, H.; Goto, N.; Sueishi, T.; Toya, M.; Kuwahara, M.; Okazaki, K.; Duffy, T.; et al. FOXO1 transcription factor regulates chondrogenic differentiation through transforming growth factor β1 signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 17555–17569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abukhdeir, A.M.; Park, B.H. P21 and p27: Roles in carcinogenesis and drug resistance. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 2008, 10, e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Bhojani, M.S.; Heaford, A.C.; Chang, D.C.; Laxman, B.; Thomas, D.G.; Griffin, L.B.; Yu, J.; Coppola, J.M.; Giordano, T.J.; et al. Phosphorylated FADD induces NF-kappaB, perturbs cell cycle, and is associated with poor outcome in lung adenocarcinomas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 12507–12512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maejima, Y.; Nah, J.; Aryan, Z.; Zhai, P.; Sung, E.A.; Liu, T.; Yakayama, K.; Moghadami, S.; Sasano, T.; Li, H.; et al. Mst1-mediated phosphorylation of FOXO1 and C/EBP-B stimulates cell-protective mechanism in cardiomyocytes. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, J.; Yao, C.; Yang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhuang, H.; Hua, Z.C. FADD phosphorylation modulates blood glucose levels by decreasing the expression of insulin-degrading enzyme. Mol. Cells 2020, 43, 373–383. [Google Scholar]

- Nagashima, T.; Shigematsu, N.; Maruki, R.; Urano, Y.; Tanaka, H.; Shimaya, A.; Shimokawa, T.; Shibasaki, M. Discovery of novel Forkhead Box O1 inhibitors for treating type 2 diabetes: Improvement of fasting glycemia in diabeti db/db mice. Mol. Pharmacol. 2010, 78, 961–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.F.; Desai, S.D.; Li, T.K.; Mao, Y.; Sun, M.; Sim, S.P. Mechanism of action of camptothecin. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2000, 922, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Yang, H.; Li, W.; Xu, H.; Yang, X.; Gan, L. Thioredoxin 1 upregulates FOXO1 transcriptional activity in drug resistance in ovarian cancer cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1852, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossa, G.; Lanzi, C.; Cassinelli, G.; Carenini, N.; Arrighetti, N.; Batti, L.; Corna, E.; Zunino, F.; Zaffaroni, N.; Perego, P. Differential outcome of MEK1/2 inhibitor-platinum combinations in platinum-sensitive and -resistant ovarian carcinoma cells. Cancer Lett. 2014, 347, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Q.; Lan, F.; Yan, X.; Xiao, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Q. Hypoxia exposure induced cisplatin resistance partially via activating p53 and hypoxia inducible factor-1α in non-small cell lung cancer A549 cells. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 16, 801–808. [Google Scholar]

- Micheau, O.; Solary, E.; Hammann, A.; Dimanche-Boitrel, M.T. Fas ligang-independent, FADD-mediated activation of the Fas death pathway by anticancer drugs. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 7987–7992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrkvova, Z.; Portesova, M.; Slaninova, I. Loss of FADD and caspases affects the response of T-cell leukemia Jurkat cells to anti-cancer drugs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diep, C.H.; Charles, N.J.; Gilks, C.B.; Kalloger, S.E.; Argenta, P.A.; Lange, C.A. Progesterone receptors induce FOXO1-dependent senescence in ovarian cancer cells. Cell Cycle 2013, 12, 1433–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Qui, M.; Mi, Z.; Meng, M.; Guo, Y.; Jiang, X.; Fang, J.; Wang, H.; Zhao, J.; Liu, Z.; et al. WT1-interacting protein inhibits cell proliferation and tumorigencity in non-small-cell lung cancer via the AKT/FOXO1 axis. Mol. Oncol. 2019, 13, 1059–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazzalini, O.; Scovassi, A.I.; Savio, M.; Stivala, L.A.; Prosperi, E. Multiple roles of the cell cycle inhibitor p21 (CDKN1A) in DNA damage response. Mutat. Res. 2010, 704, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, T.; Dutta, A. p21 in cancer: Intricate networks and multiple activities. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2009, 9, 400–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollomon, M.G.; Patterson, L.; Santiago-O’Farrill Kleinerman, E.S.; Gordon, N. Knock down of Fas-associated protein with death domain (FADD) sensitizes osteosarcoma to TNFα-induced cell death. J. Cancer 2020, 11, 1657–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchini, M.; Amiri, M.; Dick, F.A. Analysis of cell cycle position in mammalian cells. J. Vis. Exp. 2012, 59, 3491. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Walker, D.; Hall, A.; Bonwell, A.; Gordon, N.; Robinson, D.; Hollomon, M.G. FOXO1 Inhibition and FADD Knockdown Have Opposing Effects on Anticancer Drug-Induced Cytotoxicity and p21 Expression in Osteosarcoma Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 935. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020935

Walker D, Hall A, Bonwell A, Gordon N, Robinson D, Hollomon MG. FOXO1 Inhibition and FADD Knockdown Have Opposing Effects on Anticancer Drug-Induced Cytotoxicity and p21 Expression in Osteosarcoma Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):935. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020935

Chicago/Turabian StyleWalker, Danielle, Antanay Hall, Alexis Bonwell, Nancy Gordon, Danielle Robinson, and Mario G. Hollomon. 2026. "FOXO1 Inhibition and FADD Knockdown Have Opposing Effects on Anticancer Drug-Induced Cytotoxicity and p21 Expression in Osteosarcoma Cells" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 935. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020935

APA StyleWalker, D., Hall, A., Bonwell, A., Gordon, N., Robinson, D., & Hollomon, M. G. (2026). FOXO1 Inhibition and FADD Knockdown Have Opposing Effects on Anticancer Drug-Induced Cytotoxicity and p21 Expression in Osteosarcoma Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 935. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020935