Dysregulated MicroRNAs in Parkinson’s Disease: Pathogenic Mechanisms and Biomarker Potential

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Expression Levels of miRNAs

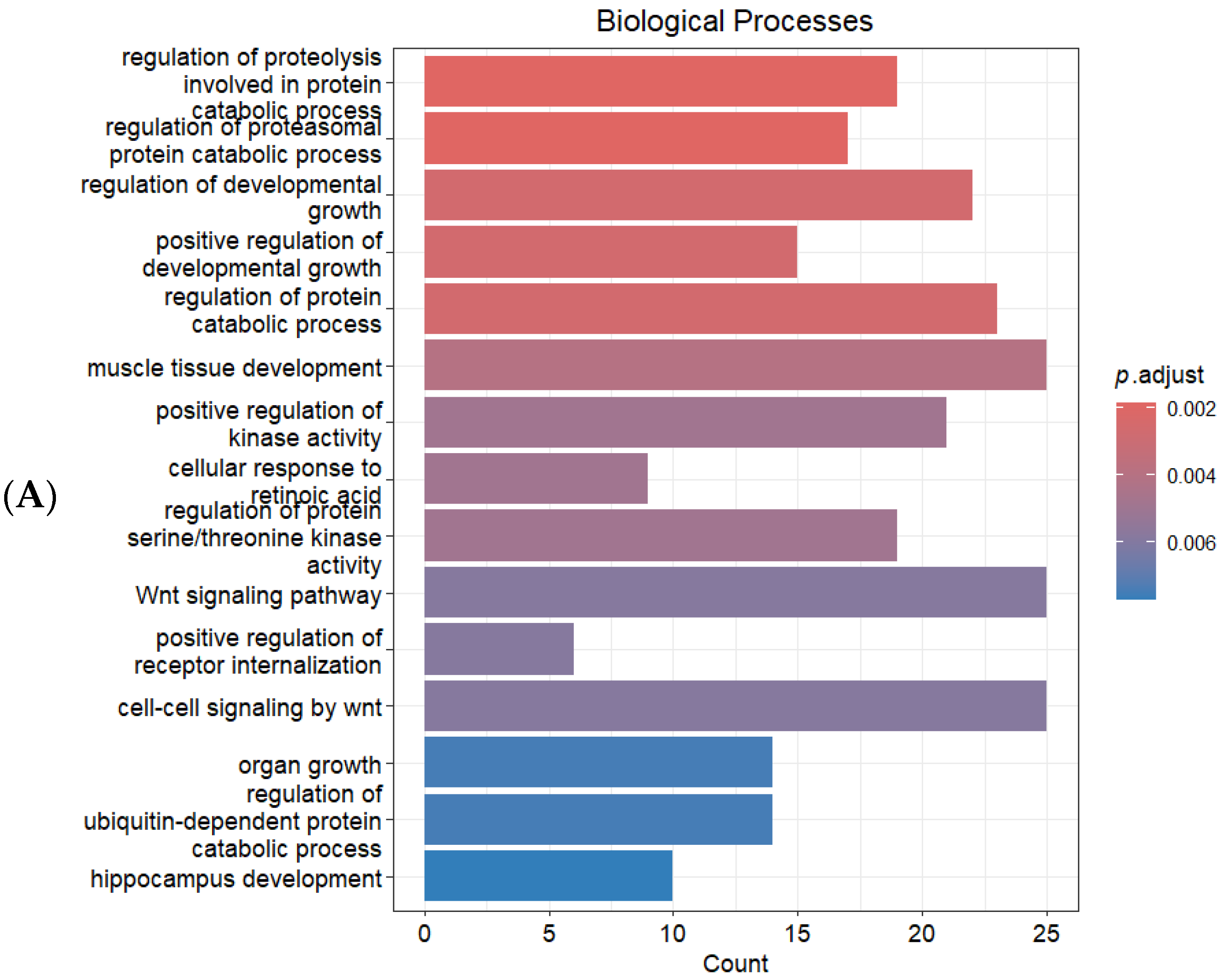

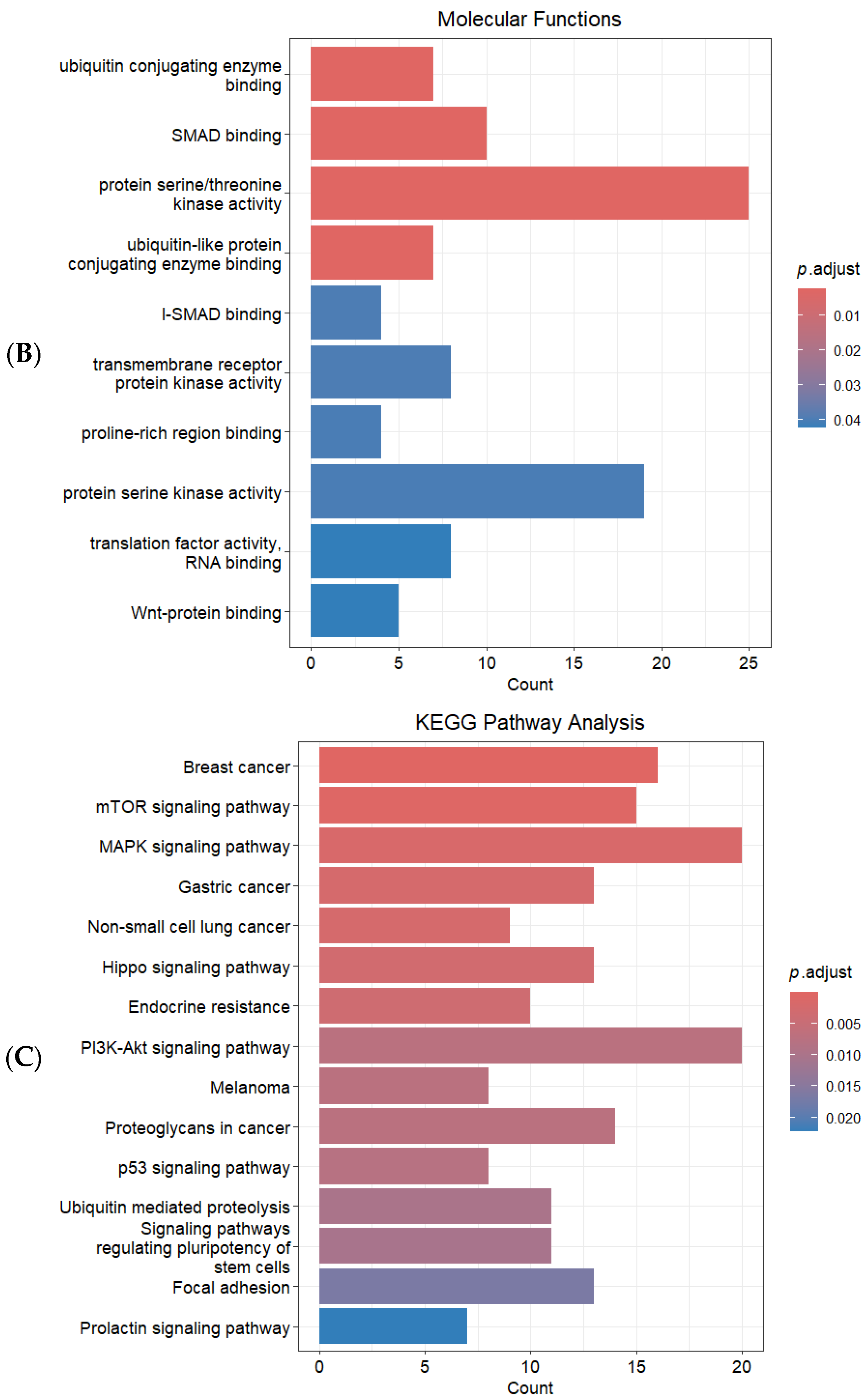

2.3. Identification of Target Genes and Functional Enrichment Analysis

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Patient Cohort

4.2. Blood Sample Collection

4.3. RNA Extraction and Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

4.4. Bioinformatics Approach for Identification of Target Genes and Functional Enrichment Analysis

4.5. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jankovic, J. Parkinson’s disease: Clinical features and diagnosis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2008, 79, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, H.R.; Spillantini, M.G.; Sue, C.M.; Williams-Gray, C.H. The pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Lancet 2024, 403, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, S.; Bharti, P.S.; Singh, R.; Rastogi, S.; Rani, K.; Sharma, V.; Gorai, P.K.; Rani, N.; Verma, B.K.; Reddy, T.J.; et al. Circulating plasma miR-23b-3p as a biomarker target for idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: Comparison with small extracellular vesicle, m.i.R.N.A. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1174951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Rijk, M.C.; Breteler, M.M.; Graveland, G.A.; Ott, A.; Grobbee, D.E.; van der Meché, F.G.; Hofman, A. Prevalence of Parkinson’s disease in the elderly: The Rotterdam Study. Neurology 1995, 45, 2143–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lau, L.M.; Breteler, M.M. Epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2006, 5, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh, S.Y.; Chao, Y.X.; Dheen, S.T.; Tan, E.K.; Tay, S.S. Role of MicroRNAs in Parkinson’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, N.; Shaheen, A.; Osama, M.; Nashwan, A.J.; Bharmauria, V.; Flouty, O. MicroRNAs regulation in Parkinson’s disease, and their potential role as diagnostic and therapeutic targets. NPJ Park. Dis. 2024, 10, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leggio, L.; Vivarelli, S.; L’Episcopo, F.; Tirolo, C.; Caniglia, S.; Testa, N.; Marchetti, B.; Iraci, N. microRNAs in Parkinson’s Disease: From Pathogenesis to Novel Diagnostic and Therapeutic Approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guévremont, D.; Roy, J.; Cutfield, N.J.; Williams, J.M. MicroRNAs in Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and diagnostic accuracy meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 16272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awuson-David, B.; Williams, A.C.; Wright, B.; Hill, L.J.; Di Pietro, V. Common microRNA regulated pathways in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1228927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Chen, J.; Sun, Y.; Li, F.; Wei, L.; Sun, W.; Deng, J.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, Z. Profiling of Differentially Expressed MicroRNAs in Saliva of Parkinson’s Disease Patients. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 738530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demleitner, A.F.; Gomes, L.C.; Wenz, L.; Tzeplaeff, L.; Pürner, D.; Luib, E.; Kunze, L.H.; Lingor, P. An Exploratory Analysis of Differential Tear Fluid miRNAs in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease and Atypical Parkinsonian Syndromes. Mol. Neurobiol. 2025, 62, 16397–16409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurel, O.M.; Torrisi, S.A.; Barbagallo, C.; Purrello, M.; Salomone, S.; Drago, F.; Ragusa, M.; Leggio, G.M. Dysregulation of miR-15a-5p, miR-497a-5p and miR-511-5p Is Associated with Modulation of BDNF and FKBP5 in Brain Areas of PTSD-Related Susceptible and Resilient Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, H.; Li, M.; Qian, L.; Yang, H.; Pang, M. Long non-coding RNA SNHG16 inhibits the oxygen-glucose deprivation and reoxygenation-induced apoptosis in human brain microvascular endothelial cells by regulating miR-15a-5p/bcl-2. Mol. Med. Rep. 2020, 22, 2685–2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhang, F.; Jiang, P.; Wu, X.; Liang, Y. Expression of the microRNAs hsa-miR-15a and hsa-miR-16-1 in lens epithelial cells of patients with age-related cataract. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 8, 2405–2410. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Lei, Z.; Sun, T. The role of microRNAs in neurodegenerative diseases: A review. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2023, 39, 53–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazrgar, M.; Khodabakhsh, P.; Prudencio, M.; Mohagheghi, F.; Ahmadiani, A. The role of microRNA-34 family in Alzheimer’s disease: A potential molecular link between neurodegeneration and metabolic disorders. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 172, 105805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaldo, L.; Mena, J.; Serradell, M.; Gaig, C.; Adamuz, D.; Vilas, D.; Samaniego, D.; Ispierto, L.; Montini, A.; Mayà, G.; et al. Platelet miRNAs as early biomarkers for progression of idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder to a synucleinopathy. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 12136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoehn, M.M.; Yahr, M.D. Parkinsonism: Onset, progression and mor-tality. Neurology 1967, 17, 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goetz, C.G.; Poewe, W.; Rascol, O.; Sampaio, C.; Stebbins, G.T.; Counsell, C.; Giladi, N.; Holloway, R.G.; Moore, C.G.; Wenning, G.K.; et al. Movement Disorder Society Task Force on Rating Scales for Parkinson’s Disease. Movement Disorder Society Task Force report on the Hoehn and Yahr staging scale: Status and recommendations. Mov. Disord. 2004, 19, 1020–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orr, M.; Liu, P. Sample size estimation while controlling false discovery rate for microarray experiments using the ssize.fdr package. R J. 2009, 1, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajak, M.; Simpson, T.I. miRNAtap: miRNAtap: microRNA Targets—Aggregated Predictions. R Package, Version 1; Bioconductor: Boston, MA, USA, 2016.

- Yu, G.; Wang, L.G.; Han, Y.; He, Q.Y. clusterProfiler: An R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS 2012, 16, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, K.K.; Dawson, V.L.; Dawson, T.M. The role of the ubiquitin-proteasomal pathway in Parkinson’s disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. Trends Neurosci. 2001, 24, S7–S14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, M.R.; Mondal, A.C. The emerging role of Hippo signaling in neurodegeneration. J. Neurosci. Res. 2020, 98, 796–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, S.K.; Jha, N.K.; Kar, R.; Ambasta, R.K.; Kumar, P. p38 MAPK and PI3K/AKT Signalling Cascades inParkinson’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Cell Med. 2015, 4, 67–86. [Google Scholar]

- Rai, S.N.; Dilnashin, H.; Birla, H.; Singh, S.S.; Zahra, W.; Rathore, A.S.; Singh, B.K.; Singh, S.P. The Role of PI3K/Akt and ERK in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Neurotox. Res. 2019, 35, 775–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Yang, K.; Ren, T.; Huang, Y.; Tang, X.; Guo, W. miR-16-5p inhibits chordoma cell proliferation, invasion and metastasis by targeting Smad3. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Hu, S.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, H.; Yang, Y.; Liu, C.; Ding, H. Ginsenoside Rd attenuates cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury by exerting an anti-pyroptotic effect via the miR-139-5p/FoxO1/Keap1/Nrf2 axis. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022, 105, 108582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, S.; Sun, Q.; Xiao, H.; Zhang, C.; Li, L. Secreted miR-34a in astrocytic shedding vesicles enhanced the vulnerability of dopaminergic neurons to neurotoxins by targeting Bcl-2. Protein Cell 2015, 6, 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Q.; Mao, Y.; Song, Y.; Huang, D. MicroRNA-34a induces apoptosis in PC12 cells by reducing B-cell lymphoma 2 and sirtuin-1 expression. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 12, 5709–5714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, P.K.; Jaiswal, S.; Sharma, P. Regulation of Neuronal Cell Cycle and Apoptosis by MicroRNA 34a. Mol. Cell Biol. 2015, 36, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Ding, Y.; Luo, N.; Niu, M.; Zhong, M.; Liu, J.; Zhao, A.; Li, Y. MicroRNA biomarkers in cerebrospinal fluid and plasma predicting cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2025, 108, 1916–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulyaeva, L.F.; Kushlinskiy, N.E. Regulatory mechanisms of microRNA expression. J. Transl. Med. 2016, 14, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azam, H.M.H.; Rößling, R.I.; Geithe, C.; Khan, M.M.; Dinter, F.; Hanack, K.; Prüß, H.; Husse, B.; Roggenbuck, D.; Schierack, P.; et al. MicroRNA biomarkers as next-generation diagnostic tools for neurodegenerative diseases: A comprehensive review. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2024, 17, 1386735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W. MicroRNAs: Biomarkers, Diagnostics, and Therapeutics. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017, 1617, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Postuma, R.B.; Berg, D.; Stern, M.; Poewe, W.; Olanow, C.W.; Oertel, W.; Obeso, J.; Marek, K.; Litvan, I.; Lang, A.E.; et al. MDS clinical diagnostic criteria for Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2015, 30, 1591–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkyilmaz, A.; Akin, M.N.; Kasap, B.; Ozdemİr, C.; Demirtas Bilgic, A.; Edgunlu, T.G. AKT1 and MAPK8: New Targets for Gestational Diabetes Mellitus? Fetal Pediatr. Pathol. 2024, 43, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, J.; Yang, R.; Zhou, R.; Deng, Y.; Li, D.; Gou, D.; Zhang, Y. Circular RNA circFARSA promotes the tumorigenesis of non-small cell lung cancer by elevating B7H3 via sponging miR-15a-5p. Cell Cycle 2022, 21, 2575–2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Zhao, J.; Zou, H.; Cai, K. CircRNA PTPRM Promotes Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Progression by Modulating the miR-139-5p/SETD5 Axis. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2022, 21, 15330338221090090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.; Shao, J.; Yu, S.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J. LncRNA MEG3 aggravates acute pulmonary embolism-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension by regulating miR-34a-3p/DUSP1 axis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 283, 137755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozdemır, C.; Celık, O.I.; Zeybek, A.; Suzek, T.; Aftabı, Y.; Karakas Celık, S.; Edgunlu, T. Downregulation of MGLL and microRNAs (miR-302b-5p, miR-190a-3p, miR-450a-2-3p) in non-small cell lung cancer: Potential roles in pathogenesis. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 2026, 45, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| miRNAs | Patients | Control | p * Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | ||

| miR-15a-5p | 6.03 (15.40) | 0.711 (3.43) | 0.001 |

| miR-16-5p | 3.22 (14.51) | 1.16 (5.36) | 0.475 |

| miR-139-5p | 0.003 (0.016) | 0.10 (0.32) | <0.001 |

| miR-34a-3p | 1.16 (3.16) | 4.45 (189.34) | 0.036 |

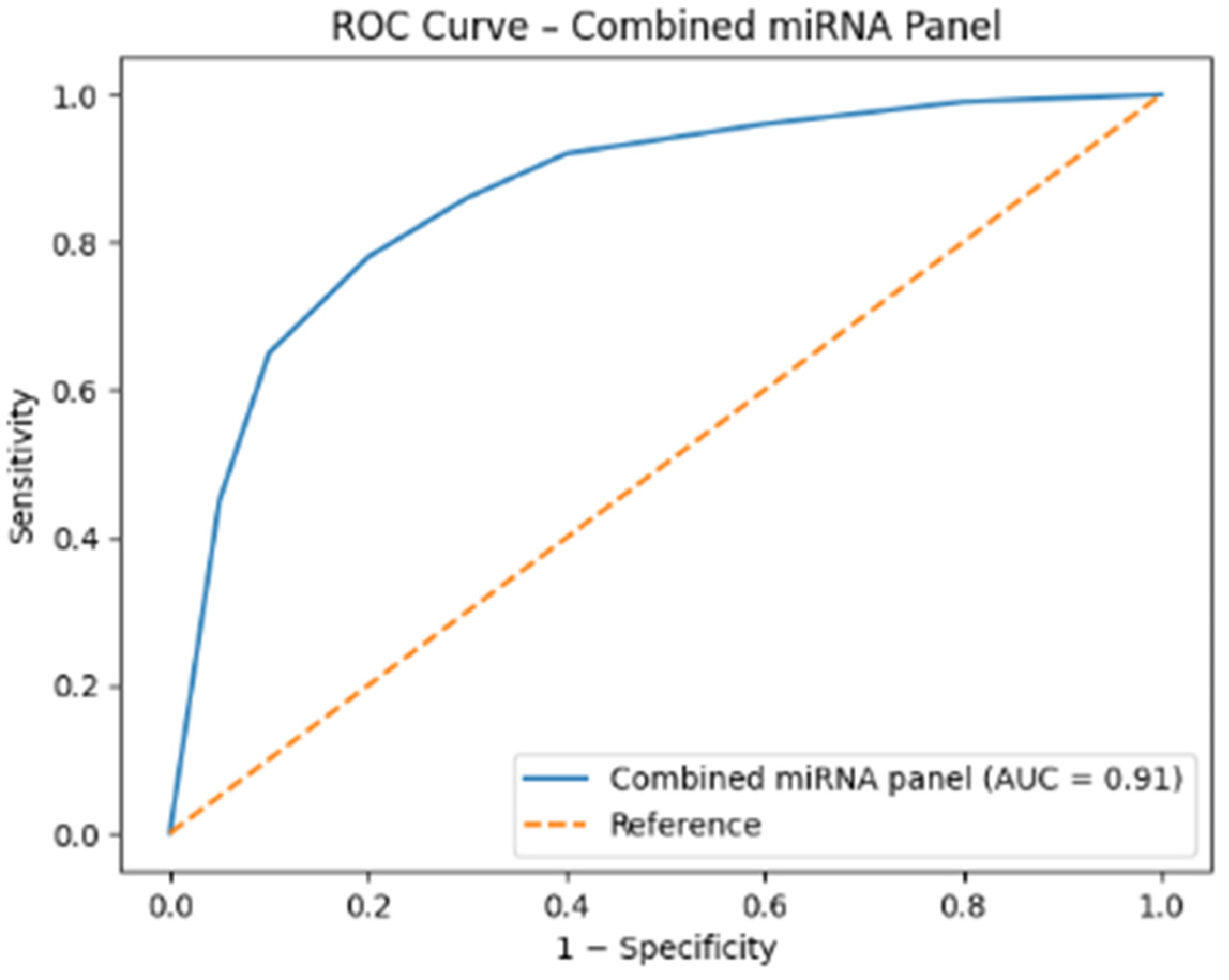

| miRNA | AUC (Area Under the Curve) | 95% Confidence Interval | p Value | Optimal Cut-Off (Relative Expression) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-139-5p | 0.865 | 0.793–0.938 | <0.001 | <0.021 | 80.4 | 86.9 |

| miR-15a-5p | 0.729 | 0.630–0.828 | 0.001 | >1.05 | 76.1 | 67.4 |

| miR-34a-3p | 0.655 | 0.542–0.768 | 0.015 | <1.70 | 60.9 | 67.4 |

| RNAs | Primer Sequences | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| miR-15a-5p | F: 5′-GCCTAGCAGCACATAATGG-3′ R: 5′-GTGCAGGGTCCGAGGT-3′ | [40] |

| miR-16-5p | F: 5′-TAGCAGCACGTAAATATTGGCG-3′ R: 5′-TGCGTGTCGTGGAGTC-3′ | [29] |

| miR-139-5p | F: 5′-TCTACAGTGCACGTGTCTCCAG-3′ R: 5′-ACCTGCGTAGGTAGTTTCATGT-3′ | [41] |

| miR-34a-3p | F: 5′-CCCTGTCGTATCCAGTGCAA-3′ R: 5′-GTCGTATCCAGTGCGTGTCG-3′ | [42] |

| U6 | F: 5′-CTCGCTTCGGCAGCACA-3′ R: 5′-AACGCTTCACGAATTTGCGT-3′ | [43] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ünal, Y.; Akbaş, D.; Özdemir, Ç.; Edgünlü, T. Dysregulated MicroRNAs in Parkinson’s Disease: Pathogenic Mechanisms and Biomarker Potential. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 930. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020930

Ünal Y, Akbaş D, Özdemir Ç, Edgünlü T. Dysregulated MicroRNAs in Parkinson’s Disease: Pathogenic Mechanisms and Biomarker Potential. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):930. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020930

Chicago/Turabian StyleÜnal, Yasemin, Dilek Akbaş, Çilem Özdemir, and Tuba Edgünlü. 2026. "Dysregulated MicroRNAs in Parkinson’s Disease: Pathogenic Mechanisms and Biomarker Potential" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 930. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020930

APA StyleÜnal, Y., Akbaş, D., Özdemir, Ç., & Edgünlü, T. (2026). Dysregulated MicroRNAs in Parkinson’s Disease: Pathogenic Mechanisms and Biomarker Potential. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 930. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020930