Tunable SiC-Based Photocatalysts for Hydrogen Generation and Environmental Remediation

Abstract

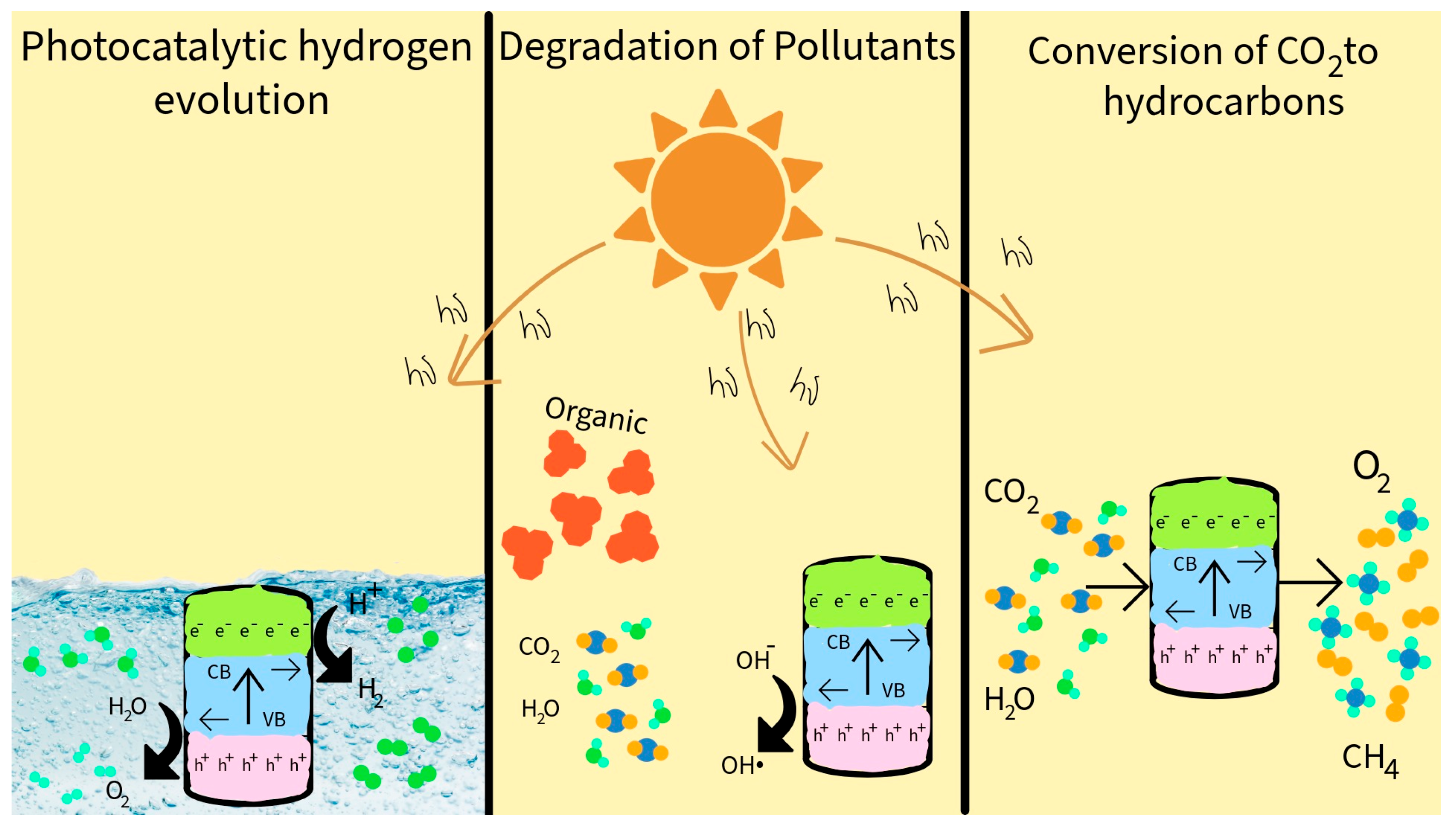

1. Introduction

2. Crystal Structure and Polytypism of SiC

3. Morphology-Controlled Synthesis of SiC Photocatalysts

3.1. One-Dimensional Structures

3.2. Nanoparticles, Powders, and Biomass-Derived SiC

3.3. Porous Foams, Flakes, and Template-Assisted Architectures

3.4. Hybrid and Composite SiC-Based Architectures

3.5. Recycled and Waste-Derived SiC Photocatalysts

4. Modification Strategies for Enhancing the Photocatalytic Performance of SiC

5. Computational and Theoretical Modeling of SiC Photocatalysts

6. Water Splitting on SiC-Based Photocatalysts

7. Photocatalytic Degradation of Organic Pollutants

| Material | Light Source | Dye | Degradation Rate | Shape/Size | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SnO2/SiC | Visible light | Methyl orange (MO) | 99% in 45 min | Nanosheets | [108] |

| Bi2WO6/SiC | Visible light | Rhodamine B | 3.7 times higher than Bi2WO6 | Petal microsphere | [170] |

| ZnO/SiC | UV light | Methylene blue | 95.7% in 120 min | Rod-shaped, flower-like | [171] |

| TiO2/β-SiC foam | Not specified | Rhodamine B | ~90% | Foam | [172] |

| Graphene-covered SiC powder (GCSP) | UV light | Rhodamine B | >100% enhancement over pristine SiC | Powder | [87] |

| TiO2/SiO2/SiC | UV light | Methylene blue | 72% | Membrane | [173] |

| TiO2/SiC foam | UV light | Pyrimethanil | 88% | Foam | [174] |

| Bi2WO6/SiC(O) | UV light | Rhodamine B | ~90% | Nanoparticles in SiC (O) matrix | [175] |

| TiO2/β-SiC | UV–Vis (100 W) | Methylene blue and methyl orange | Higher for MB than methyl orange | Anatase TiO2 agglomerates | [176] |

| TiO2/Au-CNT on SiC | Solar light | Rhodamine B | ~98.5% | Composite on SiC ceramic | [177] |

| YSSC@TiO2 | UV and visible light | Methylene blue and Congo red | High for MB and Congo red | Yolk–shell nanospheres | [99] |

| SiC@SiO2 nanocapsules | Visible light | Methylene blue | ~95% in 160 min | Hexagonal platelets (120–150 nm) | [178] |

| Cu2O-SiC/g-C3N4 | Visible light | Methyl orange | 93.70% | Ternary composite | [179] |

| Ag2CO3/SiC | Natural sunlight | Methylene blue | 98% | Nanostructure | [180] |

8. Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction on SiC-Based Systems

9. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Salve, V.; Agale, P.; Balgude, S.; Mardikar, S.; Dhotre, S.; More, P. Enhanced photocatalytic activity of SnO2@g-C3N4 heterojunctions for methylene blue and bisphenol-A degradation: Effect of interface structure and porous nature. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 15651–15669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekin, D.; Tekin, T.; Kiziltas, H. Photocatalytic degradation kinetics of Orange G dye over ZnO and Ag/ZnO thin film catalysts. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 17544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tasisa, Y.; Gunasekaran, M.; Sarma, T.; Krishnaraj, R.; Arivanandhan, M. Enhanced photocatalytic and electrochemical properties of green synthesized strontium doped titanium dioxide nanoparticles for dye removal and supercapacitor applications. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 10452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Shen, R.; Hao, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, P.; Jiang, J.; Li, X. Advances in Nanostructured Silicon Carbide Photocatalysts. Acta Phys.-Chim. Sin. 2022, 38, 2201021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, B.; Xing, Z.; Sun, D.; Li, Z.; Zhou, W. Hollow semiconductor photocatalysts for solar energy conversion. Adv. Powder Mater. 2022, 1, 100021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zu, D.; Wei, H.; Lin, Z.; Bai, X.; Ivan, M.N.A.S.; Tsang, Y.; Huang, H. The Role of Point Defects in Heterojunction Photocatalysts: Perspectives and Outlooks. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2408213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, A.; Zwijnenburg, M. The Role of Computational Chemistry in Discovering and Understanding Organic Photocatalysts for Renewable Fuel Synthesis. Adv. Energy Mater. 2021, 11, 2100709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Ferreira-Neto, E.; Khan, A.; Medeiros, I.; Wender, H. Supported nanostructured photocatalysts: The role of support-photocatalyst interactions. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2023, 22, 219–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loddo, V.; Umair, M.; Kanwal, T.; Palmisano, L.; Bellardita, M. Efficient photocatalytic removal of drugs in aqueous dispersions by using different TiO2 based semiconductors under UV and simulated solar light irradiation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A-Chem. 2025, 468, 116465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawan, D.; Stern, T.; Zhang, J.; Yuwono, J.; Pan, J.; Li, Q.; Yu, H.; Gunawan, M.; Hocking, R.; Toe, C.; et al. Scalable solar-driven reforming of alcohol feedstock to H2 using Ni/Zn3In2S6 photocatalyst. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 513, 162965, Correction in Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 515, 163701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, X.; Zheng, K.; Hu, Z.; Sun, Y.; Xie, Y. Broad-Spectral-Response Photocatalysts for CO2 Reduction. ACS Cent. Sci. 2020, 6, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Zhao, S.; Shen, Y.; Jiang, X.; Lv, H.; Han, C.; Liu, W.; Zhao, Q. A Critical Review of Clay Mineral-Based Photocatalysts for Wastewater Treatment. Catalysts 2024, 14, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhong, S.; Li, Q.; Ji, Y.; Dong, L.; Zhang, G.; Liu, Y.; He, W. Heterostructured Nanoscale Photocatalysts via Colloidal Chemistry for Pollutant Degradation. Crystals 2022, 12, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Troisi, A. High-Throughput Screening of Molecule/Polymer Photocatalysts for the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. ACS Catal. 2025, 15, 6690–6701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balu, S.; Ganapathy, D.; Arya, S.; Atchudan, R.; Sundramoorthy, A. Advanced photocatalytic materials based degradation of micropollutants and their use in hydrogen production—A review. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 14392–14424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anpo, M.; Takeuchi, M. Design and development of second-generation titanium oxide photocatalysts to better our environment-approaches in realizing the use of visible light. Int. J. Photoenergy 2001, 3, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uema, M.; Yonemitsu, K.; Momose, Y.; Ishii, Y.; Tateda, K.; Inoue, T.; Asakura, H. Effect of the Photocatalyst under Visible Light Irradiation in SARS-CoV-2 Stability on an Abiotic Surface. Biocontrol Sci. 2021, 26, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lee, C.; Horn, M.; Lee, H. Toward efficient photocatalysts for light-driven CO2 reduction: TiO2 nanostructures decorated with perovskite quantum dots. Nano Express 2021, 2, 020003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.; Chen, H.; Peng, H.; Wang, Z.; Huang, W. Graphene Modified TiO2 Composite Photocatalysts: Mechanism, Progress and Perspective. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Ali, K. Photocatalytic degradation of organic compounds in dye wastewater by Fe3+ doped nano-ZnO/TiO2 composite photocatalyst. Indian J. Chem. Technol. 2024, 31, 506–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhang, S.; Wang, G.; Li, J.; Zhang, K. Preparation of double-doped Cu, N-nano-TiO2 photocatalyst and photocatalytic inactivation of Escherichia coli in ballast water. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Air Pollution and Environmental Engineering, Xi’an, China, 15–16 December 2019; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, K.; Lv, Y.; Zhang, W.; Sun, S.; Yang, B.; Chi, F.; Ran, S.; Liu, X. One-step Synthesis of Ag3PO4/Ag Photocatalyst with Visible-light Photocatalytic Activity. Mater. Res.-IBERO-Am. J. Mater. 2015, 18, 939–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya, A.; Sánchez-Fuente, M.; Linde, M.; Cepa-López, V.; del Hierro, I.; Díaz-Sánchez, M.; Gómez-Ruiz, S.; Mas-Ballesté, R. Enhancing photocatalytic performance of F-doped TiO2 through the integration of small amounts of a quinoline-based covalent triazine framework. Nanoscale 2025, 17, 8880–8891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullin, K.; Gabdullin, M.; Gritsenko, L.; Ismailov, D.; Kalkozova, Z.; Kumekov, S.; Mukash, Z.; Sazonov, A.; Terukov, E. Electrical, optical, and photoluminescence properties of ZnO films subjected to thermal annealing and treatment in hydrogen plasma. Semiconductors 2016, 50, 1010–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Guo, B.; Lu, Q.; Gong, H.; Wang, M.; He, J.; Jia, B.; Ren, J.; Zheng, S.; Lu, Y. Preparation and Photocatalytic and Antibacterial Activities of Micro/Nanostructured TiO2-Based Photocatalysts for Application in Orthopedic Implants. Front. Mater. 2022, 9, 914905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diantariani, N.; Wahyuni, E.; Kartini, I.; Kuncaka, A. Ag/ZnO photocatalyst for photodegradation of methylene blue. In Proceedings of the 13th Joint Conference on Chemistry (13th JCC), Semarang, Indonesia, 7–8 September 2018; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Takata, T.; Pan, C.; Domen, K. Recent progress in oxynitride photocatalysts for visible-light-driven water splitting. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2015, 16, 033506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Chang, C. Recent Progress on Metal Sulfide Composite Nanomaterials for Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production. Catalysts 2019, 9, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akple, M.S.; Chimmikuttanda, S.P. A ternary Z-scheme WO3-Pt-CdS composite for improved visible-light photocatalytic H2 production activity. J. Nanoparticle Res. 2018, 20, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Sayed, M.; Bie, C.; Cheng, B.; Hu, B.; Yu, J.; Zhang, L. Hollow CdS-based photocatalysts. J. Mater. 2021, 7, 419–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprick, R.; Little, M.; Cooper, A. Organic heterojunctions for direct solar fuel generation. Commun. Chem. 2020, 3, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Jena, H.; Feng, X.; Leus, K.; Van der Voort, P. Engineering Covalent Organic Frameworks as Heterogeneous Photocatalysts for Organic Transformations. Angew. Chem.-Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202204938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G.; Cai, B.; Ott, S.; Tian, H. Visible-light photoredox catalysis with organic polymers. Chem. Phys. Rev. 2023, 4, 011307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Masten, S.; Esfahanian, E. Comparison of the photocatalytic efficacy and environmental impact of CdS, ZnFe2O4, and NiFe2O4 under visible light irradiation. Water Sci. Technol. 2021, 83, 993–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khraisheh, M.; Khazndar, A.; Al-Ghouti, M. Visible light-driven metal-oxide photocatalytic CO2 conversion. Int. J. Energy Res. 2015, 39, 1142–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Raziq, F.; Zhang, H.; Gascon, J. Key Strategies for Enhancing H2 Production in Transition Metal Oxide Based Photocatalysts. Angew. Chem.-Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202305385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanhere, P.; Chen, Z. A Review on Visible Light Active Perovskite-Based Photocatalysts. Molecules 2014, 19, 19995–20022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Singh, D.; Ahuja, R. Recent Advancements and Future Prospects in Ultrathin 2D Semiconductor-Based Photocatalysts for Water Splitting. Catalysts 2020, 10, 1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatemipayam, N.; Keramati, N.; Ghazi, M. Synthesis and characterization of cadmium sulfide and titania photocatalysts supported on mesoporous silica for optimized dye degradation under visible light. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Wei, G.; Xie, Z.; Diao, S.; Wen, J.; Tang, T.; Jiang, L.; Li, M.; Hu, G. V2C MXene-modified g-C3N4 for enhanced visible-light photocatalytic activity. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 970, 172656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, M.; Delnavaz, M. UV-light-responsive Ag/TiO2/PVA nanocomposite for photocatalytic degradation of Cr, Ni, Zn, and Cu heavy metal ions. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunge, Y.; Uchida, A.; Tominaga, Y.; Fujii, Y.; Yadav, A.; Kang, S.; Suzuki, N.; Shitanda, I.; Kondo, T.; Itagaki, M.; et al. Visible Light-Assisted Photocatalysis Using Spherical-Shaped BiVO4 Photocatalyst. Catalysts 2021, 11, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Huang, W.; Lee, P.; Lin, C. In situ precipitation 3D printing of highly ordered silver cluster-silver chloride photocatalysts. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 126, 797–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Wei, C.; Yu, L.; Xia, Z.; Cai, J.; Tian, Z.; Zou, G.; Dou, S.; Sun, J. 3D Printing of Porous Nitrogen-Doped Ti3C2 MXene Scaffolds for High-Performance Sodium-Ion Hybrid Capacitors. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 867–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Ma, W.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Guan, Z. Purification of water by bipolar pulsed discharge plasma combined with TiO2 catalysis. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Applied Electrostatics (ICAES-2012), Dalian, China, 17–19 September 2012; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, U.; Mazur, M.; Mandaliya, D.; Gudi, R.; Periasamy, S.; Bhargava, S. Self-Cleaning Ag-TiO2 Heterojunction Grafted on a 3D-Printed Metal Substrate: Photocatalytic Degradation of Rhodamine B and Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopic Monitoring of Kinetics. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 13453–13464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribag, K.; Houmad, M.; Kaddar, Y.; El Kenz, A.; Benyoussef, A. Enhancing the hydrogen production of tetragonal silicon carbide (t-SiC) with biaxial tensile strain and pH. Mater. Sci. Eng. B-Adv. Funct. Solid-State Mater. 2025, 311, 117854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, S.; Velisoju, V.; Tavares, F.; Dikhtiarenko, A.; Gascon, J.; Castaño, P. Silicon carbide in catalysis: From inert bed filler to catalytic support and multifunctional material. Catal. Rev.-Sci. Eng. 2023, 65, 174–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, M.; Richter, T.; Pearson, R.; Tamang, A.; Balster, T.; Knipp, D.; Wagner, V. Controlled electrodeposition of ZnO nanostructures for enhanced light scattering properties. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2014, 44, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Wang, S.; Yan, L.; Wu, C.; Yu, H.; Han, Z.; Cheng, Z.; Luo, J.; Zhang, C.; Sun, Y. Preparation of phosphomolybdic acid/silicon carbide composites and study on its photocatalytic degradation performance of dyeing wastewater. Mater. Today Chem. 2025, 45, 102675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Luo, J.; Feng, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Wang, C. Ingenious p-d orbital hybridization induced by atomic Yb doping for CO2 reduction to CO. Rare Met. 2025, 44, 5439–5451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Xia, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, R.; Jian, Y.; Xiang, C.; Nie, Z.; Liu, H. SiC nanoparticles promote CO2 fixation and biomass production of Chlorella sorokiniana via expanding the abilities of capturing and transmitting photons. Algal Res.-Biomass Biofuels Bioprod. 2024, 84, 103814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Long, J.; Guo, T.; Yin, L.; Hua, Q. Harnessing simulated sunlight for dichlorvos and azoxystrobin breakdown in water by ion-implanted defect photocatalysts. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 365, 132633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Pan, Z.; Lai, Y.; Ananpattarachai, J.; Serpa, M.; Shapiro, N.; Zhao, Z.; Westerhoff, P. Green hydrogen production via a photocatalyst-enabled optical fiber system: A promising route to net-zero emissions. Energy Clim. Change 2025, 6, 100175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, L.; Reddy, R. Thermal plasma synthesis of SiC nano-powders/nano-fibers. Mater. Res. Bull. 2006, 41, 2303–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshtaghioun, B.; Poyato, R.; Cumbrera, F.; de Bernardi-Martin, S.; Monshi, A.; Abbasi, M.; Karimzadeh, F.; Dominguez-Rodriguez, A. Rapid carbothermic synthesis of silicon carbide nano powders by using microwave heating. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2012, 32, 1787–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, J.; Jung, Y.; Lee, J.; Yoon, J.; Jo, C. Synthesis of SiC nano-powders by solid-vapor reaction. Key Eng. Mater. 2006, 317–318, 211–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, S.; Koo, S.; Cho, W.; Hwnag, K.; Kim, J. Synthesis of SiC nano-powder from organic precursors using RF inductively coupled thermal plasma. Ceram. Int. 2012, 38, 1959–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi, A.; Golestani-Fard, F.; Rezaie, H.; Ehsani, N. A study on sol-gel synthesis and characterization of SiC nano powder. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2011, 59, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawrah, M.; Zayed, M.; Ali, M. Synthesis and characterization of SiC and SiC/Si3N4 composite nano powders from waste material. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 227, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Kang, W.; Lin, W.; Kang, J. Machine-learning enhanced thermal stability investigation of single Shockley stacking faults in 4H-SiC. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2024, 242, 113077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tien, N.; Thao, P.; Jafarova, V.; Roy, D. Predicting Model for Device Density of States of Quantum-Confined SiC Nanotube with Magnetic Dopant: An Integrated Approach Utilizing Machine Learning and Density Functional Theory. Silicon 2024, 16, 5991–6009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cellini, F.; Lavini, F.; Berger, C.; de Heer, W.; Riedo, E. Layer dependence of graphene-diamene phase transition in epitaxial and exfoliated few-layer graphene using machine learning. 2D Mater. 2019, 6, 035043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Zheng, Y.; Du, X.; Dai, W.; Wang, Y. Prediction of thermal conductivity in UO2 with SiC additions and related decisive features discovery. J. Nucl. Mater. 2024, 601, 155347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Zhao, S.; Li, J.; Zuo, Y.; Tian, J.; Tang, H.; Fan, J.; Zhang, G. Optimizing the chemical vapor deposition process of 4H-SiC epitaxial layer growth with machine-learning-assisted multiphysics simulations. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2024, 59, 104507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revathi, V.; Aravinda, K.; Raj, V.; Rajesh, P. Optimizing Al/SiC Nanocomposite Microstructures: An Efficient Hybrid LWO-EPTANN Approach. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2025, 36, e70057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, T.; Kato, M.; Ichimura, M.; Hatayama, T. Solar-to-hydrogen conversion efficiency of water photolysis with epitaxially grown p-type SiC. Mater. Sci. Forum 2013, 740–742, 859–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Dai, Y.; Li, M.; Wei, W.; Huang, B. Stable Si-based pentagonal monolayers: High carrier mobilities and applications in photocatalytic water splitting. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 24055–24063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, J.X.; Sun, J.W. A Review of Recent Progress on Silicon Carbide for Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting. Sol. RRL 2020, 4, 2000111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukushkin, S.; Markov, L.; Osipov, A.; Svyatets, G.; Chernyakov, A.; Pavlov, S. Thermal Conductivity of Hybrid SiC/Si Substrates for the Growth of LED Heterostructures. Tech. Phys. Lett. 2023, 49, S327–S329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriya, P.; Prasongthum, N.; Natewong, P.; Wasanapiarnpong, T.; Gao, X.; Zhao, T.; Tian, J.; Mhadmhan, S.; Hong, T.; Reubroycharoen, P. Hydrogen production by steam reforming of fusel oil over nickel deposited on pyrolyzed rice husk supports. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 462–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, J.; Xin, L.; Wang, M. Hierarchical 3C-SiC nanowires as stable photocatalyst for organic dye degradation under visible light irradiation. Mater. Sci. Eng. B-Adv. Funct. Solid-State Mater. 2014, 179, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Wang, W.; Zhao, P.; Wang, S.; Yang, K.; Shi, H.; Xu, M.; Dong, Y. Silicon carbide catalytic ceramic membranes with nano-wire structure for enhanced anti-fouling performance. Water Res. 2022, 226, 119209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, M.; Qamar, M.; Ahmed, I.; Rehman, A.; Ali, S.; Ismail, I.; Hameed, A. The suitability of silicon carbide for photocatalytic water oxidation. Appl. Nanosci. 2018, 8, 987–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lezcano, G.; Kulkarni, S.; Velisoju, V.; Realpe, N.; Castaño, P. Intrinsic microkinetic effects of spray-drying and SiC co-support on Mn-Na2WO4/SiO2 catalysts used in oxidative coupling of methane. React. Chem. Eng. 2025, 10, 975–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacroix, M.; Dreibine, L.; de Tymowski, B.; Vigneron, F.; Edouard, D.; Bégin, D.; Nguyen, P.; Pham, C.; Savin-Poncet, S.; Luck, F.; et al. Silicon carbide foam composite containing cobalt as a highly selective and re-usable Fischer-Tropsch synthesis catalyst. Appl. Catal. A-Gen. 2011, 397, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Li, X.; Wang, H.; Xing, X.; Yang, Y. SiC nanowires grown on activated carbon in a polymer pyrolysis route. Mater. Sci. Eng. B-Adv. Funct. Solid-State Mater. 2010, 166, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genc, M.; Sarilmaz, A.; Aslan, E.; Ozel, F.; Patir, I. Enhanced photocatalytic hydrogen evolution via SiC loaded CeO2 nanofiber composite. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2025, 175, 114203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, C.; Huang, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, J.; Xu, L.; Song, Q.; Bian, Z.; Li, J.; et al. Waste photovoltaic wafers-derived SiC-based photocatalysts for pharmaceutical wastewater purification: S-scheme, waste utilization, and life cycle assessment. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2025, 220, 108332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, H.; Li, B.; Li, C.; Zang, Y.; Xu, P.; Zhao, X.; Fan, H.; Qiu, Y. One-dimensional Au/SiC heterojunction nanocomposites with enhanced photocatalytic and photoelectrochemical performances: Kinetics and mechanism insights. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 267, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Chen, J.; Liao, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Gao, L.; Li, Y. Highly efficient photocatalytic hydrogen production of platinum nanoparticle-decorated SiC nanowires under simulated sunlight irradiation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 14581–14587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Yang, S.; Cai, W. Semiconductor Nanoparticles by Laser Ablation in Liquid: Synthesis, Assembly, and Properties. In Laser Ablation in Liquids: Principles and Applications in the Preparation of Nanomaterials; Jenny Stanford Publishing: Singapore, 2012; pp. 397–438. [Google Scholar]

- Nikitin, D.; Shanenkov, I.; Yeletsky, P.; Nassyrbayev, A.; Tabakaev, R.; Shanenkova, Y.; Ryskulov, D.; Tsimmerman, A.; Sivkov, A. Agricultural waste derived silicon carbide composite nanopowders as efficient coelectrocatalysts for water splitting. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 442, 140890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, D.; Chu, J.; Yang, D.; Yu, Y. Directional surface hydroxylation on 6H-SiC induces surface electron polarization and proton activation promoting photocatalytic water splitting for hydrogen. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 51, 1380–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xia, T.; Wallenmeyer, P.; Harris, C.; Peterson, A.; Corsiglia, G.; Murowchick, J.; Chen, X. Photocatalytic Hydrogen Generation from Pure Water using Silicon Carbide Nanoparticles. Energy Technol. 2014, 2, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y. Photocatalytic hydrogen evolution from water on SiC under visible light irradiation. React. Kinet. Catal. Lett. 2007, 91, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Guo, L.; Lin, J.; Hao, W.; Shang, J.; Jia, Y.; Chen, L.; Jin, S.; Wang, W.; Chen, X. Graphene covered SiC powder as advanced photocatalytic material. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012, 100, 023113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondal, M.; Ali, M.; Chang, X.; Shen, K.; Xu, Q.; Yamani, Z. Pulsed laser-induced photocatalytic reduction of greenhouse gas CO2 into methanol: A value-added hydrocarbon product over SiC. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part A-Toxic/Hazard. Subst. Environ. Eng. 2012, 47, 1571–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Yuan, C.; Li, C.; Zhou, C.; Zhao, H.; Chen, T.; Xin, L.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Ye, S.; et al. Enhanced direct hole oxidation of titanate nanotubes via cerium single-atom doping for photocatalytic degradation of pollutants. Rare Met. 2025, 44, 5512–5528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, S.; Li, X.; Huang, W.; He, Z.; Fu, X.; Zhu, L.; Xu, M. Highly active nickel-loaded β-SiC nanowire catalysts for photocatalytic H2 production by water splitting. AIP Adv. 2023, 13, 125202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouamé, N.; Robert, D.; Keller, V.; Keller, N.; Pham, C.; Nguyen, P. TiO2/β-SiC foam-structured photoreactor for continuous wastewater treatment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2012, 19, 3727–3734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes-Diaz, K.; Drobek, M.; Julbe, A.; Cambedouzou, J. SiC Foams for the Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue under Visible Light Irradiation. Materials 2023, 16, 1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcellona, M.; Spanò, V.; Fiorenza, R.; Scirè, S.; Defforge, T.; Gautier, G.; Fragalà, M. Characterization and reuse of SiC flakes generated during electrochemical etching of 4H-SiC wafers. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 3034–3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Li, C.; Zhao, X.; Feng, X.; Chen, H. CoFe2O4 deposited on the rice husk-derived cordyceps-like SiC as an effective electrocatalyst for overall water splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 49, 723–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Li, T.; Wang, Y. Preparation of ternary Cr2O3-SiC-TiO2 composites for the photocatalytic production of hydrogen. Particuology 2012, 10, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Yin, F.; Zhang, J.; Li, G.; Kofie, G.; Tan, Y.; Chen, B. Preparation of Co/SiC catalyst and its catalytic activity for ammonia decomposition to produce hydrogen. Catal. Today 2024, 437, 114774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Dai, J.; Song, F.; Cao, X.; Lyu, X.; Crittenden, J. Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity of SiC-Based Ternary Graphene Materials: A DFT Study and the Photocatalytic Mechanism. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 20142–20151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes-Diaz, K.; Drobek, M.; Julbe, A.; Ayral, A.; Cambedouzou, J. Mesoporous SiC-Based Photocatalytic Membranes and Coatings for Water Treatment. Membranes 2023, 13, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Su, T.; Sun, L.; Du, H. Facile preparation of yolk-shell structured Si/SiC@C@TiO2 nanocomposites as highly efficient photocatalysts for degrading organic dye in wastewater. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 4063–4069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, H.; Heng, M.; Guo, J.; Yang, R.; Zhang, H.; Fan, J.; Li, G.; Miao, Y.; Xiao, S. 3D Interwoven SiC/g-C3N4 Structure for Superior Charge Separation and CO2 Photoreduction Performance. Langmuir 2024, 41, 1115–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Wu, T.; Lv, H. Electrochemical conversion of rice husk in molten salts to photocatalyst for CO2 photoreduction. Funct. Mater. Lett. 2025, 18, 2550006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Gao, R.; Ren, K.; Li, C.; He, J.; Li, G. A comparative study of the sonocatalytic degradation of methylene blue by using silicon carbide and titanium dioxide. New J. Chem. 2024, 48, 15370–15378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Lin, H.; Chen, C.; Lu, Y.; Hsiao, F.; Hsieh, C.; Lin, B.; Yu, B.; Ma, D.; Kuo, H.; et al. Au/SiC Microfluidic Devices Fabricated by Rapid Laser Cladding for Photocatalytic Degradation of Water Pollutants. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 4486–4496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, I.; Sreedhar, A.; Pallavolu, M.; Reddy, L.; Cho, M.; Kim, D.; Jayashree, N.; Shim, J. Photoelectrochemical water oxidation kinetics and antibacterial studies of one-dimensional SiC nanowires synthesized from industrial waste. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2021, 25, 2457–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, X.; Tian, W.; Li, J.; Deng, L.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, L.; Lu, H.; Yin, L.; Mahmood, N. High-Temperature Oxidation-Resistant ZrN0.4B0.6/SiC Nanohybrid for Enhanced Microwave Absorption. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 15869–15880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, D.; Yang, Z.; Jiang, C.; Zhang, J. Synergistic photocatalytic effect of TiO2 coatings and p-type semiconductive SiC foam supports for degradation of organic contaminant. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2014, 144, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juárez-Ramírez, I.; Moctezuma, E.; Torres-Martínez, L.; Gómez-Solís, C. Short time deposition of TiO2 nanoparticles on SiC as photocatalysts for the degradation of organic dyes. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2013, 39, 1523–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Dai, Z.; Liang, B.; Mu, Y. Facile Synthesis of SnO2/SiC Nanosheets for Photocatalytic Degradation of MO. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2021, 31, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Din, H.; Idrees, M.; Rehman, G.; Nguyen, C.; Gan, L.; Ahmad, I.; Maqbool, M.; Amin, B. Electronic structure, optical and photocatalytic performance of SiC-MX2 (M = Mo, W and X = S, Se) van der Waals heterostructures. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 24168–24175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Jin, X.; Zhang, P.; Song, N.; Gao, P.; Fischer, R.; Mukherjee, S. In Situ Engineering of Two-Dimensional Heterostructures for Enhanced Photocatalytic Decontamination of Methyl Orange. ACS Appl. Eng. Mater. 2025, 3, 1292–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valadez-Renteria, E.; Rosales, M.; Hernandez-Del Castillo, P.; Rodriguez-Gonzalez, C.; Esquivel-Castro, T.; Alonso, V.; Salas, P.; Oliva, J. Rubber/BiOCl: Yb,Er composite for the enhanced degradation of methylene blue and Rhodamine B dyes under solar irradiation. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1027, 180625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Li, Q.; Yang, X.; Chen, X.; Xu, X. Synthesis of SiC/BiOCl Composites and Its Efficient Photocatalytic Activity. Catalysts 2020, 10, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Guo, Z.; Wang, D.; Pan, N.; Yuan, W. Heterogeneous nucleation of CdS to enhance visible-light photocatalytic hydrogen evolution of SiC/CdS composite. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2015, 107, 012102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Li, Q.; Yang, X.; Chen, X.; Xu, X. Synthesis and Characterization of N-Doped SiC Powder with Enhanced Photocatalytic and Photoelectrochemical Performance. Catalysts 2020, 10, 769, Correction in Catalysts 2020, 10, 1155.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, Q.; Muhammad, S.; Idrees, M.; Hieu, N.; Binh, N.; Nguyen, C.; Amin, B. First-principles study of the electronic structures and optical and photocatalytic performances of van der Waals heterostructures of SiS, P and SiC monolayers. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 14263–14268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, P.; Zhu, X.; Huang, F.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, N. An efficient catalyst for carbamazepine degradation that alkali-etched silicon carbide synergy effect with ZIF-67 (ZIF-67/AE-SiC) in peroxymonosulfate system. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 506, 159685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, X.; Zhang, W.; Cao, X.; Lv, S.; Huo, L. A Simple Highly Efficient Catalyst with NiOX-loaded Reed-based SiC/CNOs for Hydrogen Production by Photocatalytic Water-splitting. ChemistrySelect 2024, 9, e202303612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Janczarek, M.; Wang, K.; Zheng, S.; Kowalska, E. Morphology-Governed Performance of Plasmonic Photocatalysts. Catalysts 2020, 10, 1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez, S.; Acharya, A.; Dehghan, Z. Revisiting thermal and non-thermal effects in hybrid plasmonic antenna reactor photocatalysts. Chem Catal. 2025, 5, 101294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, M.; Mariandry, K.; Ghorpade, U.; Saha, S.; Kokate, R.; Mishra, R.; Nielsen, M.; Tilley, R.; Xie, B.; Suryawanshi, M.; et al. Plasmonic Hot-Carrier Engineering at Bimetallic Nanoparticle/Semiconductor Interfaces: A Computational Perspective. Small 2025, 21, e2410173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Bing, F.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Fang, X. Novel Z-scheme visible-light-driven Ag3PO4/Ag/SiC photocatalysts with enhanced photocatalytic activity. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 4652–4658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lai, S.; Wu, W.; Zhong, Y.; Guo, Y.; Yu, P.; Hou, M.; Liu, H.; Jiang, L.; Chen, X.; et al. SiC Substrate/Pt Nanoparticle/Graphene Nanosheet Composite Photocatalysts for Hydrogen Generation. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024, 7, 8958–8968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafeez, H.Y.; Lakhera, S.K.; Narayanan, N.; Harish, S.K.; Hayakawa, Y.; Lee, B.K.; Neppolian, B. Environmentally Sustainable Synthesis of a CoFe2O4-TiO2/rGO Ternary Photocatalyst: A Highly Efficient and Stable Photocatalyst for High Production of Hydrogen (Solar Fuel). ACS Omega 2019, 4, 880–891, Correction in ACS Omega 2019, 4, 2980. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.9b00169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chen, M.; Luo, K.; Huang, X.; Tang, S.; Wang, L.; Xu, L. Rationally designed 2D/2D highly reduced graphene oxide modified wide band gap semiconductor photocatalysts for hydrogen production. Surf. Sci. 2023, 734, 122316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.; Xu, L.; Zeng, J.; Qi, X.; Yang, Y.; Ma, Z.; Huang, X.; Wang, L.; Shuai, C. Layer-dependent photocatalysts of GaN/SiC-based multilayer van der Waals heterojunctions for hydrogen evolution. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2021, 11, 3059–3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, C.; Deng, Y.; Cao, H.; Liang, C.; Yang, J.; Zhutang, J.; Wei, L.; Xiao, L. Shell-Thickness-Modulated Charge Carrier Transfer in Au Nanocube@CdS Core-Shell Nanostructures for Plasmon-Driven Photocatalysis. Chem. Biomed. Imaging 2025, 3, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, C.; Guo, X.; Sankar, M.; Yang, H.; Ma, B.; Zhang, Y.; Tong, X.; Jin, G.; Guo, X. Synergistic Effect of Segregated Pd and Au Nanoparticles on Semiconducting SiC for Efficient Photocatalytic Hydrogenation of Nitroarenes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 23029–23036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Lu, J.; Huang, N.; Wu, Q.; Yan, Q. Study on process parameters of ultraviolet photocatalytic-Fenton reaction polishing of single-crystal silicon carbide based on Ag@AgCl photocatalyst. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2025, 156, 112400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, C.; Kim, T.; Jiao, W.; Yang, Y.; Lazarides, A.; Hingerl, K.; Bruno, G.; Brown, A.; Losurdo, M. Evidence of Plasmonic Coupling in Gallium Nanoparticles/Graphene/SiC. Small 2012, 8, 2721–2730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Pan, J.; Fu, J.; Shen, W.; Liu, H.; Cai, C.; Zhang, L.; Tang, H.; Zhang, Y. Constructing 0D/1D/2D Z-scheme heterojunctions of Ag nanodots/SiC nanofibers/g-C3N4 nanosheets for efficient photocatalytic water splitting. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 2262–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Zhao, X.; Anning, C.; Crittenden, J.; Lyu, X. Photocatalytic water splitting of ternary graphene-like photocatalyst for the photocatalytic hydrogen production. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2020, 14, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.L.; Hong, M.H.; Ho, G.W. Hierarchical Assembly of SnO2/ZnO Nanostructures for Enhanced Photocatalytic Performance. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehbaz, A.; Majid, A.; Batool, H.; Alkhedher, M.; Haider, S.; Alam, K. Probing the potential of Al2CO/SiC heterostructures for visible light-driven photocatalytic water splitting using first-principles strategies. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12, 12657–12671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xie, K.; Qiang, Z.; Ding, J.; Duan, L.; Ni, L.; Fan, J. Rational design of a direct Z-scheme β-AsP/SiC van der Waals heterostructure as an efficient photocatalyst for overall water splitting under wide solar spectrum. CrystEngComm 2023, 25, 6685–6696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Bai, K.; Ding, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, E.; Zheng, J. Janus XSSe/SiC (X = Mo, W) van der Waals heterostructures as promising water-splitting photocatalysts. Phys. E-Low-Dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 2020, 123, 114207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, S.; Yang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Duan, L. SiC/PtSe2 van der Waals heterostructure: A high-efficiency direct Z-scheme photocatalyst for overall water splitting predicted from first-principles study. Micro Nanostruct. 2024, 195, 207953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Ding, K.; Zhang, K.; Xie, Y.; Chen, W.; Meng, Z.; Xu, Y.; Weng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Z. Designing Janus CrSSe/SiC heterojunction for efficient direct Z-scheme overall water splitting: A first-principles study. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 135, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Lei, S.; Fang, L.; Guo, Y.; Xie, H. BiOCl/SiC Type I heterojunction with efficient interfacial charge transfer for enhanced photocatalytic CO2 reduction. Surf. Interfaces 2025, 58, 105838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deák, P.; Aradi, B.; Frauenheim, T. Polaronic effects in TiO2 calculated by the HSE06 hybrid functional: Dopant passivation by carrier self-trapping. Phys. Rev. B 2011, 83, 155207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bockstedte, M.; Mattausch, A.; Pankratov, O. Ab initio study of the migration of intrinsic defects in 3C-SiC. Phys. Rev. B 2003, 68, 205201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Z.; Fang, F. Investigation of photocatalysis/vibration-assisted finishing of reaction sintered silicon carbide. J. Manuf. Process. 2025, 133, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibn Shamsah, S. Thermal Conductivity Modeling for Liquid-Phase-Sintered Silicon Carbide Ceramics Using Machine Learning Computational Methods. Crystals 2025, 15, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.; Jing, Y.; Frauenheim, T. Advancing band structure simulations of complex systems of C, Si and SiC: A machine learning driven density functional tight-binding approach. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2025, 27, 3796–3802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Gygi, F.; Galli, G. Charge state and entropic effects affecting the formation and dynamics of divacancies in 3C-SiC. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2024, 8, 046201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Yuan, J.; Mao, Y. Accelerating the design and screening of surface-functionalized monolayer SiC for photocatalytic water splitting and ultraviolet applications via machine learning. Mater. Today Chem. 2024, 41, 102302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, K.; Gao, Y.; Zeng, Q.; Luan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, L.; Wu, J.; Lu, Z. Numerical modeling of SiC by low-pressure chemical vapor deposition from methyltrichlorosilane. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2020, 28, 1733–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Z.; Hashemi, A.; Berencén, Y.; Komsa, H.; Erhart, P.; Zhou, S.; Helm, M.; Krasheninnikov, A.; Astakhov, G. Local vibrational modes of Si vacancy spin qubits in SiC. Phys. Rev. B 2020, 101, 144109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, X.; Chen, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, L.; Chen, M. Machine-Learning-Based Interatomic Potentials for Group IIB to VIA Semiconductors: Toward a Universal Model. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2024, 20, 5717–5731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norskov, J.; Bligaard, T.; Logadottir, A.; Kitchin, J.; Chen, J.; Pandelov, S.; Stimming, U. Trends in the exchange current for hydrogen evolution. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2005, 152, J23–J26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Choi, J. Hydrogen Adsorption on the Vertical Heterostructures of Graphene and Two-Dimensional Electrides: A First-Principles Study. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 16063–16069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukkaew, P.; Danielsson, Ö.; Kordina, O.; Janzén, E.; Ojamäe, L. Ab Initio Study of Growth Mechanism of 4H-SiC: Adsorption and Surface Reaction of C2H2, C2H4, CH4, and CH3. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 1249–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakranov, N.; Kuli, Z.; Mukash, Z.; Bakranova, D. SiC-based heterostructures and tandem PEC cells for efficient hydrogen production. Results Eng. 2025, 27, 106862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; She, G.; Mu, L.; Shi, W. Porous SiC nanowire arrays as stable photocatalyst for water splitting under UV irradiation. Mater. Res. Bull. 2012, 47, 917–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzhabiev, T. Photoreduction of carbon dioxide with water in the presence of SiC/ZnO heterostructural semiconductor materials. Kinet. Catal. 1997, 38, 795–800. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Huang, L.; Guo, Z.; Han, X.; Liu, C.; Wang, W.; Yuan, W. Enhanced photocatalytic hydrogen production over Au/SiC for water reduction by localized surface plasmon resonance effect. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 456, 871–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Shi, J.; Wang, X.; Cui, H.; Fu, M. Recent progress in the preparation and application of semiconductor/graphene composite photocatalysts. Chin. J. Catal. 2013, 34, 621–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, X.; Yu, J. Graphene-based photocatalytic composites. RSC Adv. 2011, 1, 1426–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.; Wang, Y.; Tong, X.; Jin, G.; Guo, X. Photocatalytic hydrogen production over modified SiC nanowires under visible light irradiation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 15038–15044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Wu, X.; Shen, J.; Chu, P. High-Efficiency Electrochemical Hydrogen Evolution Based on Surface Autocatalytic Effect of Ultrathin 3C-SiC Nanocrystals. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 1545–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Guo, X.; Dong, L.; Jin, G.; Wang, Y.; Guo, X. Enhanced photocatalytic performance of chemically bonded SiC-graphene composites for visible-light-driven overall water splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 12733–12738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Z.; Gui, Q.; Li, H.; Cao, H.; Yang, B.; Dang, W.; Liu, S.; Xue, J. Synthesis of metal-free Si/SiC composite for photocatalytic hydrogen production. Appl. Phys. A-Mater. Sci. Process. 2022, 128, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Wang, B.; Wang, Y. Hierarchical SnO2 nanosheets@SiC nanofibers for enhanced photocatalytic water splitting. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2018, 15, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Guo, Z.; Yang, J.; Wang, D.; Yuan, W. Enhanced photocatalytic H2 evolution over micro-SiC by coupling with CdS under visible light irradiation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 6296–6300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Wang, D.; Guo, Z.; Huang, L.; Peng, Y.; Lin, J.; Yuan, W. Excellent visible light absorption by adopting mesoporous SiC in SiC/CdS for enhanced photocatalytic hydrogen generation. Mater. Express 2019, 9, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhang, J.; Huang, F. Enhanced visible light photocatalytic H2 evolution of metal-free g-C3N4/SiC heterostructured photocatalysts. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 391, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Chou, Y.; Yuan, C. Photodegradation of tetracycline using O-gCN/SiC/PVDF thin film photocatalysts irradiated with simulated sunlight. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 198, 107174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, X.; Liu, L.; Yang, L.; Gan, Z.; Chu, P. 3C-SiC/ZnS heterostructured nanospheres with high photocatalytic activity and enhancement mechanism. AIP Adv. 2015, 5, 037120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Teng, C.; Tang, Z.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Yuan, W. In-situ preparation of II & S-type hybrid heterojunction Ag2MoO4/AgCl/SiC photocatalyst from waste photovoltaic silicon for cefaclor and pharmaceutical wastewater degradation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 361, 131465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenanakis, G.; Vernardou, D.; Dalamagkas, A.; Katsarakis, N. Photocatalytic and electrooxidation properties of TiO2 thin films deposited by sol-gel. Catal. Today 2015, 240, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Tang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Lu, S.; Yang, F. Bi2WO6/SiC composite photocatalysts with enhanced photocatalytic performance for dyes degradation. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2022, 140, 109434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Wang, F. Preparation and photocatalytic properties of ZnO/SiC composites for methylene blue degradation. Appl. Phys. A-Mater. Sci. Process. 2022, 128, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allé, P.; Fanou, G.; Robert, D.; Adouby, K.; Drogui, P. Photocatalytic degradation of Rhodamine B dye with TiO2 immobilized on SiC foam using full factorial design. Appl. Water Sci. 2020, 10, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huertas, R.; Fraga, M.; Crespo, J.; Pereira, V. Sol-gel membrane modification for enhanced photocatalytic activity. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2017, 180, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M’Bra, I.; García-Muñoz, P.; Drogui, P.; Keller, N.; Trokourey, A.; Robert, D. Heterogeneous photodegradation of Pyrimethanil and its commercial formulation with TiO2 immobilized on SiC foams. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A-Chem. 2019, 368, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Lai, S.; Yang, L.; Riedel, R.; Yu, Z. Polymer-derived porous Bi2WO6/SiC(O) ceramic nanocomposites with high photodegradation efficiency towards Rhodamine B. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 8562–8569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pstrowska, K.; Szyja, B.; Czapor-Irzabek, H.; Kiersnowski, A.; Walendziewski, J. The Properties and Activity of TiO2/beta-SiC Nanocomposites in Organic Dyes Photodegradation. Photochem. Photobiol. 2017, 93, 558–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhuo, S.; Wang, W.; Li, R.; Wang, P. An Integrated Photocatalytic and Photothermal Process for Solar-Driven Efficient Purification of Complex Contaminated Water. Energy Technol. 2020, 8, 2000456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Yu, J.; Zhou, L.; Muhammad, J.; Dong, X.; Wang, Y.; Yu, H.; Quan, X.; Li, S.; Jung, Y. Interface evolution in the platelet-like SiC@C and SiC@SiO2 monocrystal nanocapsules. Nano Res. 2017, 10, 2644–2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, M.; Han, J.; Dai, X.; Ge, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Hai, Z. Construction of Cu2O ternary composite comprising SiC and g-C3N4 for improved photocatalytic degradation of methyl orange via synergetic Z-scheme effect. Opt. Mater. 2024, 155, 115883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bora, L.; Mewada, R. Photocatalytic treatment of dye wastewater and parametric study using a novel Z-scheme Ag2CO3/SiC photocatalyst under natural sunlight. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 5556–5565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Chen, Q.; Qin, X.; Rao, X.; Li, S.; Liu, G.; Wang, J.; Dong, X.; Luo, D.; Chen, F. Heterojunction and Photothermal-Piezoelectric Polarization Effect Co-Driven BiOIO3-Bi2Te3 Photocatalysts for Efficient Mixed Pollutant Removal. Energy Environ. Mater. 2025, 8, e70006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wang, M.; Luo, H.; Li, K.; Jia, Y.; Fu, M.; Jiang, C.; Yao, S.; Yin, Y. Photothermal Catalysis of Cellulose to Prepare Levulinic Acid-Rich Bio-Oil. Polymers 2025, 17, 857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorenza, R.; Calantropo, L.; La Greca, E.; Liotta, L.; Gulino, A.; Ferlazzo, A.; Musumeci, M.; Salanitri, G.; Carroccio, S.; Dativo, G.; et al. Solar-promoted photo-thermal CO2 methanation on SiC/hydrotalcites-derived catalysts. Catal. Today 2025, 449, 115182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Lei, Y.; Huang, Y.; Fang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, L.; Li, X. Photocatalytic reduction of carbon dioxide to methanol by Cu2O/SiC nanocrystallite under visible light irradiation. J. Nat. Gas Chem. 2011, 20, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Shang, X.; Zhang, J.; Shen, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Z. Crystal phase engineering SiC nanosheets for enhancing photocatalytic CO2 reduction. Environ. Sci.-Adv. 2023, 2, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, P.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wen, N.; Ding, Z.; Yuan, R.; Wang, X.; et al. Highly selective photocatalytic reduction of CO2 to CH4 on electron-rich Fe species cocatalyst under visible light irradiation. Carbon Energy 2024, 6, e435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material | Band Gap (eV) | Light Source | Electrolyte | Stability | H2 Evolution Rate | Shape/Size | Crystal Structure/Surface Area | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiC nanoparticles | 2.7 | 150 W Xe lamp, AM 1.5 | pH adjusted with NaOH/HCl | Decreased over time | 36 µmol/g/h (1st h) and 25 µmol/g/h (6 h) | Nanoparticles, 9 nm | β-SiC (3C-SiC) | [85] |

| Ni-loaded β-SiC nanowires | 2.33 | 300 W Xe lamp, >420 nm | Na2S–Na2SO3 | Stable, 4 cycles | 11.1 µL/3 h | Nanowires, ~25 nm | 3C-SiC, no impurities | [90] |

| β-SiC nanowires, acid-modified | 2.27–2.35 | 300 W Xe lamp, >420 nm | Pure water | Stable, 30 h | 61 mL/g/h | Nanowires, 70–400 nm | β-SiC, 45 m2/g | [158] |

| Green SiC powder | ~2.3 | 150 W Xe lamp, UV filter | Pure water, Na2S, CH3OH, and EDTA | Consistent | 24.9 µL/g/h | Particles, 400–500 nm | 6H-SiC and 3C-SiC | [86] |

| 3C-SiC nanocrystals | 2.24 | 500 W Xe lamp | 0.5 M Na2SO4 | Stable photocurrent | H2 bubbles observed | Nanocrystals, 1.5–7.5 nm | 3C-SiC | [159] |

| Material | Band Gap (eV) | Light Source | Electrolyte | Stability | H2 Evolution Rate | Shape/Size | Crystal Structure/Surface Area | Doping/QY/AQE | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag/SiC/g-C3N4 | 2.79 (g-C3N4) | 350 W Xe lamp | 0.5 M Na2SO4 | Stable, 4 cycles | 2971 µmol/h/g | SiC nanofibers, ~25 nm; Ag nanodots, ~10 nm | β-SiC, g-C3N4, Ag | AQE: 7.3% at 420 nm | [130] |

| NiOx/SiC/CNOs | 2.4 | 300 W Xe lamp, >420 nm | TEOA, Eosin Y | Stable, 3 cycles | 3160.2 µmol/g/h | SiC nanowires, 100–200 nm; NiOx, 6–10 nm | β-SiC, defect sites | NiOx cocatalyst | [117] |

| Pt/SiC nanowires | ~2.48 | 300 W Xe lamp | Distilled water | Stable, 20 h | 4572 µL/g/h | Nanowires, ~50 nm; Pt, ~2.5 nm | 3C-SiC | Pt loading | [81] |

| Au/SiC | 2.4 | 300 W Xe lamp, >420 nm | 0.5 M Na2SO4 | Stable, 4 h | 53.6 µmol/h/g | SiC, ~5 µm; Au, 4–5 nm | Hexagonal SiC, 14.7 m2/g | Au nanoparticles | [155] |

| SiC-graphene | 2.4 | 300 W Xe lamp, >420 nm | Distilled water | Stable, 12 h | 87.52 µL/g/h | SiC, ~5 µm; graphene sheets | β-SiC, 24 m2/g | Graphene bonding | [160] |

| Material | Band Gap (eV) | Light Source | Electrolyte | Stability | H2 Evolution Rate | Shape/Size | Crystal Structure/Surface Area | Doping/QY/AQE | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MoS2/SiC/GO | 1.94 | Xe lamp, 400–700 nm | 1 M Na2S and 1 M Na2SO3 | Stable, multiple cycles | 4.203 mL/4 h | Sheet-like SiC, MoS2, and GO layers | 6H-SiC | QY: 21.69% at 400–700 nm | [131] |

| GO/SiC/MoS2 | 2.61–2.91 | Xe lamp, 400–700 nm | 0.1 M Na2S and 0.1 M Na2SO3 | Stable, 3 cycles | 43.59 µmol/h/g | SiC nanosheets, GO, and MoS2 | 6H-SiC, 3.73 m2/g | QY: 20.45% at 400–700 nm | [97] |

| Si/SiC | 1.01 (Si) and 2.36 (SiC) | 300 W Xe lamp | Deionized water | Stable, >5 h | 14.01 µmol/h/g | Rod-like, fibrous, 20–60 nm | 3C-SiC and Si, 54.95 m2/g | - | [161] |

| SiC/SnO2 | 2.39 (SiC) | 300 W Xe lamp | 0.1 M Na2S and 0.1 M Na2SO3 | Stable, 14 h | 1887.3 µmol/g (4 h) | SiC nanofibers, ~200 nm; SnO2 nanosheets, ~10 nm | Cubic SiC and rutile SnO2, 28.6 m2/g | - | [162] |

| SiC/CdS/Pt | 2.4 (SiC and CdS) | 300 W Xe lamp, >420 nm | 0.1 M Na2S and 0.1 M Na2SO3 | Stable, 12 h | 5460 µmol/h/g (with Pt) | Micro-SiC and CdS, ~100 nm | Cubic-hexagonal SiC and cubic CdS, 54 m2/g | AQE: 2.1% at 420 nm | [163] |

| Mesoporous SiC/CdS | 1.63 | 300 W Xe lamp, >420 nm | 0.01 M Na2S and 0.01 M Na2SO3 | Stable, 16 h | 952 µmol/h/g | Worm-like SiC, ~0.3 µm; CdS nanoparticles | Cubic SiC and cubic CdS, 614 m2/g | - | [164] |

| g-C3N4/SiC | 2.7 (g-C3N4) and 2.4 (SiC) | Visible light, >420 nm | 8 mL of TEOA | High stability | 182 µmol/g/h | g-C3N4 sheets, SiC particles | Cubic and hexagonal SiC, 12.52 m2/g | - | [165] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bakranova, D.; Nagel, D.; Bakranov, N.; Kapsalamova, F.; Boukhvalov, D. Tunable SiC-Based Photocatalysts for Hydrogen Generation and Environmental Remediation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 774. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020774

Bakranova D, Nagel D, Bakranov N, Kapsalamova F, Boukhvalov D. Tunable SiC-Based Photocatalysts for Hydrogen Generation and Environmental Remediation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):774. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020774

Chicago/Turabian StyleBakranova, Dina, David Nagel, Nurlan Bakranov, Farida Kapsalamova, and Danil Boukhvalov. 2026. "Tunable SiC-Based Photocatalysts for Hydrogen Generation and Environmental Remediation" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 774. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020774

APA StyleBakranova, D., Nagel, D., Bakranov, N., Kapsalamova, F., & Boukhvalov, D. (2026). Tunable SiC-Based Photocatalysts for Hydrogen Generation and Environmental Remediation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 774. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020774