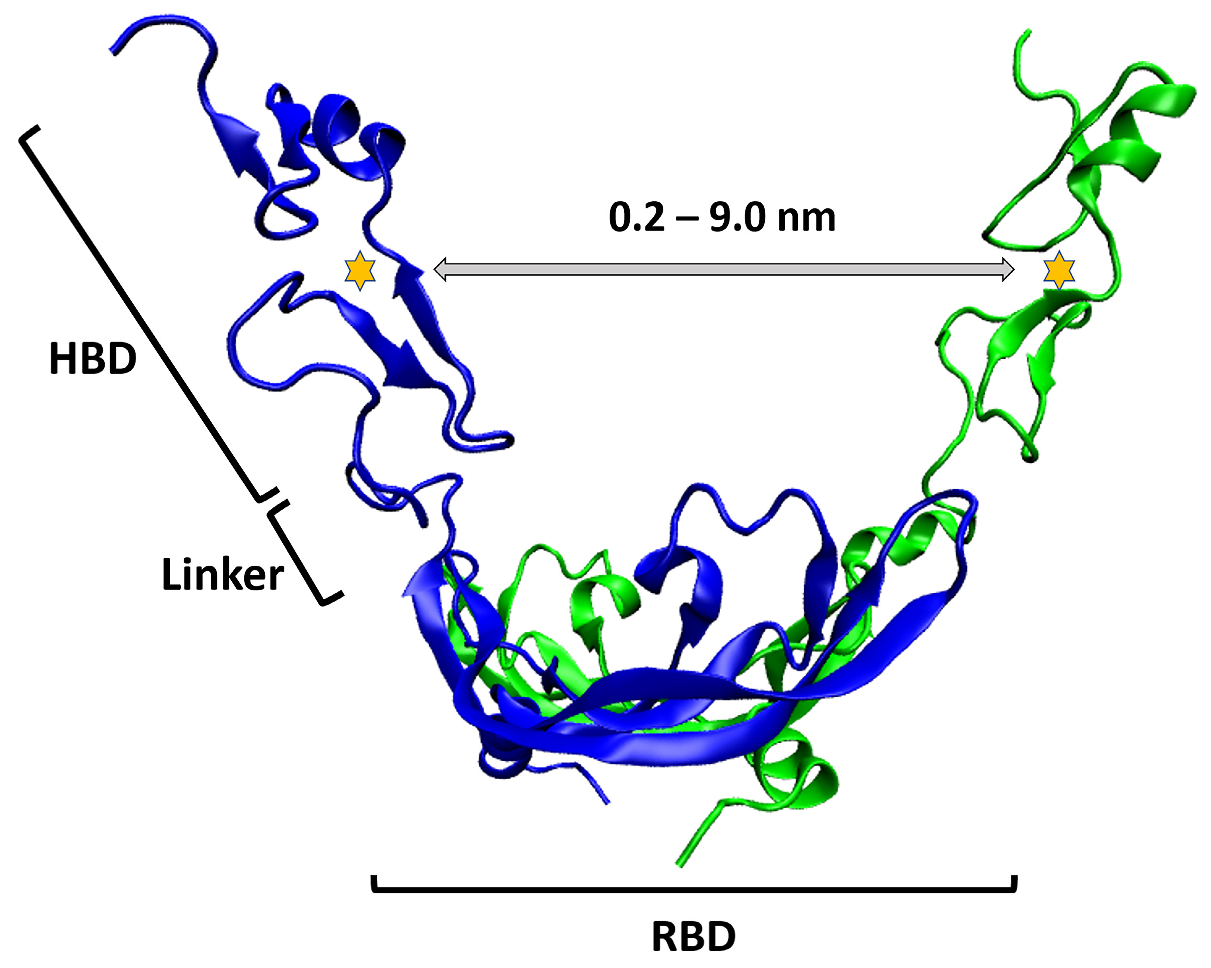

Determining the Optimal Heparin Binding Domain Distance in VEGF165 Using Umbrella Sampling Simulations for Optimal Dimeric Aptamer Design

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. PMF Along the Reaction Coordinate of VEGF165

2.2. HBD-HBD Distance Change in VEGF165 upon VEGFR-2 Binding

2.3. Hydrogen Bond Formation Between VEGF165 and VEGFR-2

2.4. Computationally Designing an Aptamer Homodimer Targeting VEGF165

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Modeling VEGF165

3.2. Modeling VEGFR-2/VEGF165

3.3. Modeling DNA Aptamer

3.4. Docking Simulations

3.5. MD Simulations

3.6. Binding Free Energy Calculations

4. Conclusions

5. Limitations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Risau, W. Mechanisms of angiogenesis. Nature 1997, 386, 671–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeliet, P. Angiogenesis in life, disease and medicine. Nature 2005, 438, 932–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, N.; Gerber, H.-P.; LeCouter, J. The biology of VEGF and its receptors. Nat. Med. 2003, 9, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, M.; Gordon, E.; Claesson-Welsh, L. Mechanisms and regulation of endothelial VEGF receptor signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016, 17, 611–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, Y.J.; Kalathingal, M.; Rhee, Y.M. Elucidating activation and deactivation dynamics of VEGFR-2 transmembrane domain with coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulations. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0281781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modi, S.J.; Kulkarni, V.M. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR-2)/KDR inhibitors: Medicinal chemistry perspective. Med. Drug Discov. 2019, 2, 100009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, G.; Boghozian, R.; Mirshafiey, A. The potential role of angiogenic factors in rheumatoid arthritis. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2014, 17, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.W.; Le Couter, J.; Strauss, E.C.; Ferrara, N. Vascular endothelial growth factor a in intraocular vascular disease. Ophthalmology 2013, 120, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, E.W.; Adamis, A.P. Targeting angiogenesis, the underlying disorder in neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2005, 40, 352–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhisitkul, R. Vascular endothelial growth factor biology: Clinical implications for ocular treatments. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2006, 90, 1542–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uciechowska-Kaczmarzyk, U.; Babik, S.; Zsila, F.; Bojarski, K.K.; Beke-Somfai, T.; Samsonov, S.A. Molecular dynamics-based model of VEGF-A and its heparin interactions. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2018, 82, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, W.; Park, J.W.; Go, Y.J.; Kim, W.J.; Rhee, Y.M. Considering both small and large scale motions of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is crucial for reliably predicting its binding affinities to DNA aptamers. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 9315–9326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, Y.J.; Kalathingal, M.; Rhee, Y.M. An ensemble docking approach for analyzing and designing aptamer heterodimers targeting VEGF165. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nonaka, Y.; Sode, K.; Ikebukuro, K. Screening and improvement of an anti-VEGF DNA aptamer. Molecules 2010, 15, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasegawa, H.; Taira, K.-i.; Sode, K.; Ikebukuro, K. Improvement of aptamer affinity by dimerization. Sensors 2008, 8, 1090–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manochehry, S.; McConnell, E.M.; Li, Y. Unraveling determinants of affinity enhancement in dimeric aptamers for a dimeric protein. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 17824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manochehry, S.; Gu, J.; McConnell, E.M.; Salena, B.J.; Li, Y. In vitro selection of new DNA aptamers for human vascular endothelial growth factor 165. ChemBioChem 2020, 21, 2029–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, Y.; Yoshida, W.; Abe, K.; Ferri, S.; Schulze, H.; Bachmann, T.T.; Ikebukuro, K. Affinity improvement of a VEGF aptamer by in silico maturation for a sensitive VEGF-detection system. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85, 1132–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moccia, F.; Riccardi, C.; Musumeci, D.; Leone, S.; Oliva, R.; Petraccone, L.; Montesarchio, D. Insights into the G-rich VEGF-binding aptamer V7t1: When two G-quadruplexes are better than one! Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 8318–8331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrie, G.M.; Valleau, J.P. Nonphysical sampling distributions in Monte Carlo free-energy estimation: Umbrella sampling. J. Comput. Phys. 1977, 23, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurrus, E.; Engel, D.; Star, K.; Monson, K.; Brandi, J.; Felberg, L.E.; Brookes, D.H.; Wilson, L.; Chen, J.; Liles, K.; et al. Improvements to the APBS biomolecular solvation software suite. Protein Sci. 2018, 27, 112–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brozzo, M.S.; Bjelić, S.; Kisko, K.; Schleier, T.; Leppänen, V.-M.; Alitalo, K.; Winkler, F.K.; Ballmer-Hofer, K. Thermodynamic and structural description of allosterically regulated VEGFR-2 dimerization. Blood 2012, 119, 1781–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, P.; Li, B.; Huang, S.-Y. HDOCK: A web server for protein–protein and protein–DNA/RNA docking based on a hybrid strategy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, W365–W373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, W.; Dalke, A.; Schulten, K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996, 14, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riccardi, C.; Napolitano, E.; Musumeci, D.; Montesarchio, D. Dimeric and multimeric DNA aptamers for highly effective protein recognition. Molecules 2020, 25, 5227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, Y.A.; Christinger, H.W.; Keyt, B.A.; de Vos, A.M. The crystal structure of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) refined to 1.93 Å resolution: Multiple copy flexibility and receptor binding. Structure 1997, 5, 1325–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairbrother, W.J.; Champe, M.A.; Christinger, H.W.; Keyt, B.A.; Starovasnik, M.A. Solution structure of the heparin-binding domain of vascular endothelial growth factor. Structure 1998, 6, 637–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanwell, M.D.; Curtis, D.E.; Lonie, D.C.; Vandermeersch, T.; Zurek, E.; Hutchison, G.R. Avogadro: An advanced semantic chemical editor, visualization, and analysis platform. J. Cheminform. 2012, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, J.; Adler, J.; Dunger, J.; Evans, R.; Green, T.; Pritzel, A.; Ronneberger, O.; Willmore, L.; Ballard, A.J.; Bambrick, J.; et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 2024, 630, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, A.; Bertoni, M.; Bienert, S.; Studer, G.; Tauriello, G.; Gumienny, R.; Heer, F.T.; de Beer, T.A.P.; Rempfer, C.; Bordoli, L. SWISS-MODEL: Homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W296–W303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuker, M. Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 3406–3415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Xiao, Y. 3dDNA: A computational method of building DNA 3D structures. Molecules 2022, 27, 5936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Birkholz, N.; Fineran, P.C.; Park, H.H. Molecular basis of anti-CRISPR operon repression by Aca10. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, 8919–8928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Liu, C.; Yu, J.; Han, J.; Du, J.; Liang, S.; Wang, W.; Liu, Q.; Lian, R.; Zhu, T. PHF14 enhances DNA methylation of SMAD7 gene to promote TGF-β-driven lung adenocarcinoma metastasis. Cell Discov. 2023, 9, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janin, J.; Henrick, K.; Moult, J.; Eyck, L.T.; Sternberg, M.J.E.; Vajda, S.; Vakser, I.; Wodak, S.J. CAPRI: A Critical Assessment of PRedicted Interactions. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 2003, 52, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, W.L.; Chandrasekhar, J.; Madura, J.D.; Impey, R.W.; Klein, M.L. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 1983, 79, 926–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Kasavajhala, K.; Belfon, K.A.; Raguette, L.; Huang, H.; Migues, A.N.; Bickel, J.; Wang, Y.; Pincay, J.; Wu, Q.; et al. ff19SB: Amino-acid-specific protein backbone parameters trained against quantum mechanics energy surfaces in solution. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2019, 16, 528–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case, D.A.; Aktulga, H.M.; Belfon, K.; Ben-Shalom, I.Y.; Berryman, J.T.; Brozell, S.R.; Cerutti, D.S.; Cheatham, T.E., III; Cisneros, G.A.; Cruzeiro, V.W.D.; et al. Amber 2022; University of California: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Press, W.H.; Teukolsky, S.A.; Vetterling, W.T.; Flannery, B.P. Numerical Recipes 3rd Edition: The Art of Scientific Computing; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Rosenberg, J.M.; Bouzida, D.; Swendsen, R.H.; Kollman, P.A. The weighted histogram analysis method for free-energy calculations on biomolecules. I. The method. J. Comput. Chem. 1992, 13, 1011–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, P.; Hess, B.; Lindahl, E. GROMACS 2022 Source Code (Version 2022). Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/6103835 (accessed on 22 February 2022).

- Hess, B.; Bekker, H.; Berendsen, H.J.; Fraaije, J.G. LINCS: A linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 1997, 18, 1463–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essmann, U.; Perera, L.; Berkowitz, M.L.; Darden, T.; Lee, H.; Pedersen, L.G. A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J. Chem. Phys. 1995, 103, 8577–8593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussi, G.; Donadio, D.; Parrinello, M. Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J. Chem. Phys. 2007, 126, 014101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernetti, M.; Bussi, G. Pressure control using stochastic cell rescaling. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 153, 114107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdés-Tresanco, M.S.; Valdés-Tresanco, M.E.; Valiente, P.A.; Moreno, E. gmx_MMPBSA: A New Tool to Perform End-State Free Energy Calculations with GROMACS. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2021, 17, 6281–6291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Linker Length | Docking Score a,b | Distance (nm) c |

| 0 dT | −1079.8 ± 74.2 | 5.6 ± 0.6 |

| 1 dT | −1114.4 ± 32.3 | 5.0 ± 0.2 |

| 2 dTs | −1116.0 ± 76.4 | 5.1 ± 0.4 |

| 3 dTs | −1122.5 ± 71.4 | 4.8 ± 0.3 |

| 4 dTs | −1093.2 ± 69.7 | 4.5 ± 0.4 |

| 5 dTs | −1101.7 ± 74.5 | 5.8 ± 0.4 |

| 6 dTs | −1092.6 ± 68.2 | 5.6 ± 0.3 |

| 7 dTs | −1125.2 ± 72.1 | 5.0 ± 0.3 |

| 8 dTs | −1114.5 ± 71.9 | 5.5 ± 0.2 |

| 9 dTs | −1128.0 ± 72.7 | 5.1 ± 0.1 |

| 10 dTs | −1071.6 ± 66.6 | 5.5 ± 0.2 |

| 15 dTs | −1123.2 ± 70.0 | 5.6 ± 0.3 |

| 20 dTs | −1151.6 ± 70.8 | 4.7 ± 0.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lee, J.S.; Go, Y.J.; Rhee, Y.M. Determining the Optimal Heparin Binding Domain Distance in VEGF165 Using Umbrella Sampling Simulations for Optimal Dimeric Aptamer Design. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 712. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020712

Lee JS, Go YJ, Rhee YM. Determining the Optimal Heparin Binding Domain Distance in VEGF165 Using Umbrella Sampling Simulations for Optimal Dimeric Aptamer Design. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):712. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020712

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Jung Seok, Yeon Ju Go, and Young Min Rhee. 2026. "Determining the Optimal Heparin Binding Domain Distance in VEGF165 Using Umbrella Sampling Simulations for Optimal Dimeric Aptamer Design" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 712. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020712

APA StyleLee, J. S., Go, Y. J., & Rhee, Y. M. (2026). Determining the Optimal Heparin Binding Domain Distance in VEGF165 Using Umbrella Sampling Simulations for Optimal Dimeric Aptamer Design. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 712. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020712