Effect of the AHR Inhibitor CH223191 as an Adjunct Treatment for Mammarenavirus Infections

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

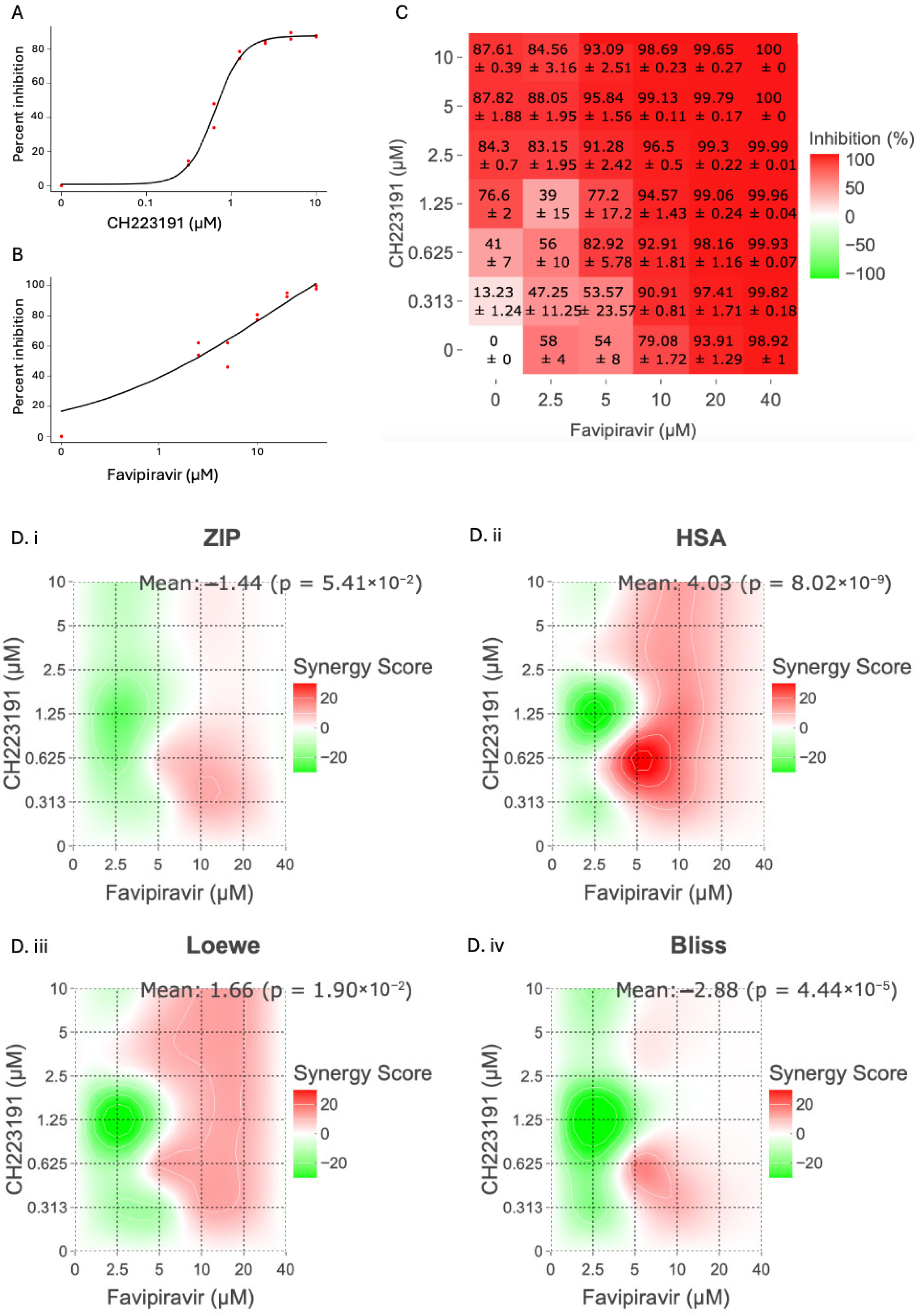

2.1. Antiviral Effect of CH223191 and Favipiravir Combinations in Cell Culture

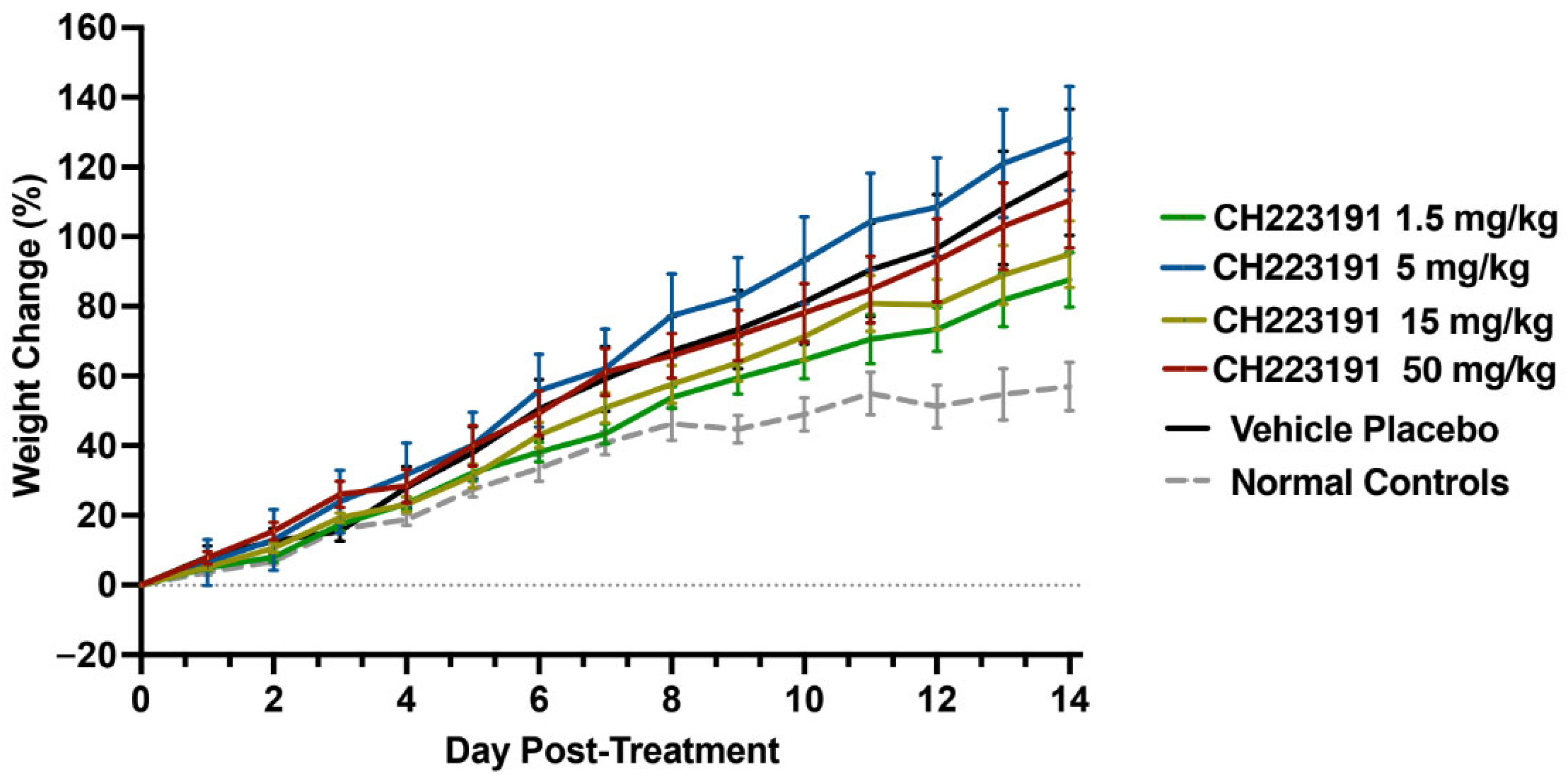

2.2. CH223191 Tolerance in the hTfR1 Mouse Model

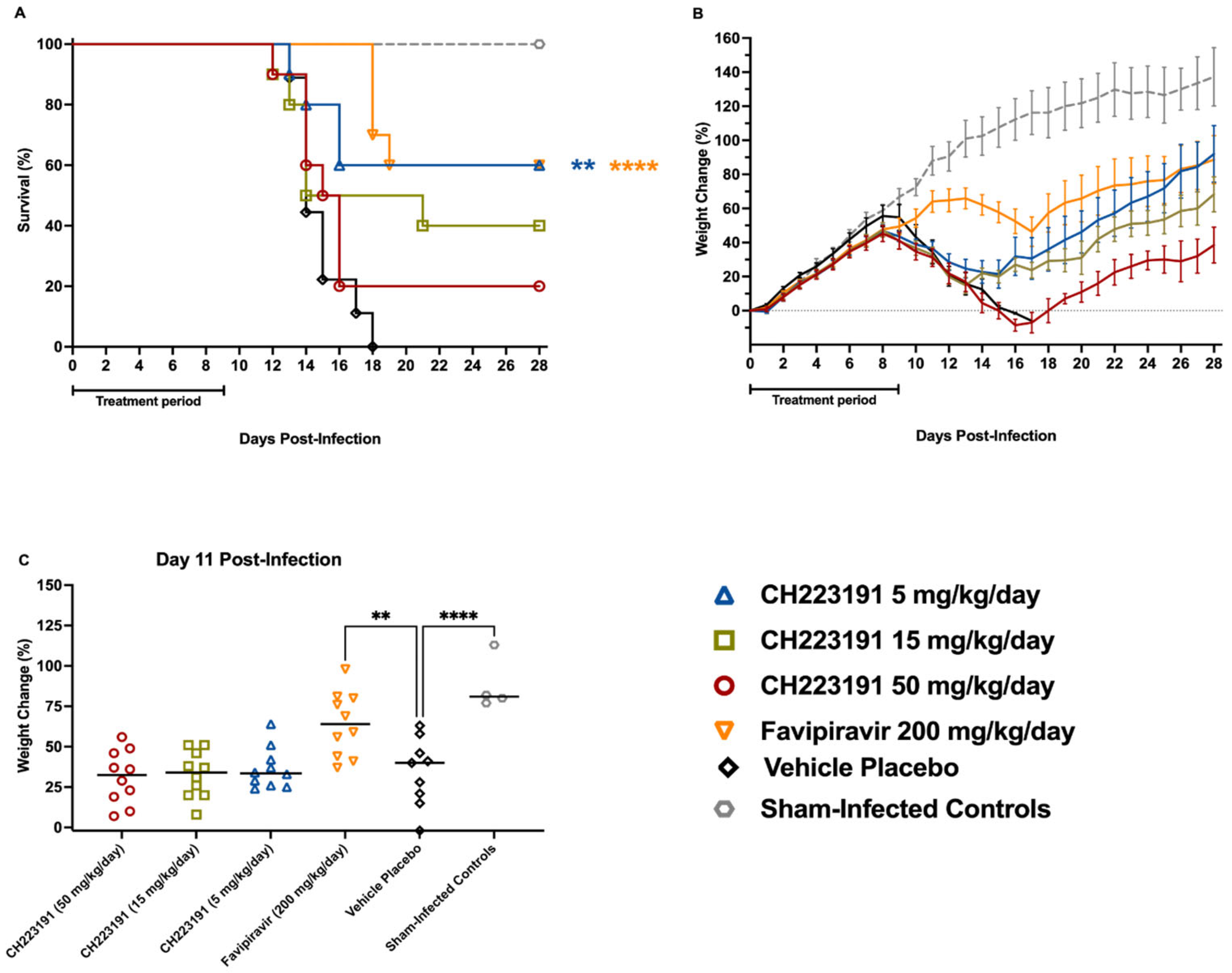

2.3. Evaluation of CH223191 in the hTfR1 Mouse JUNV Infection Model

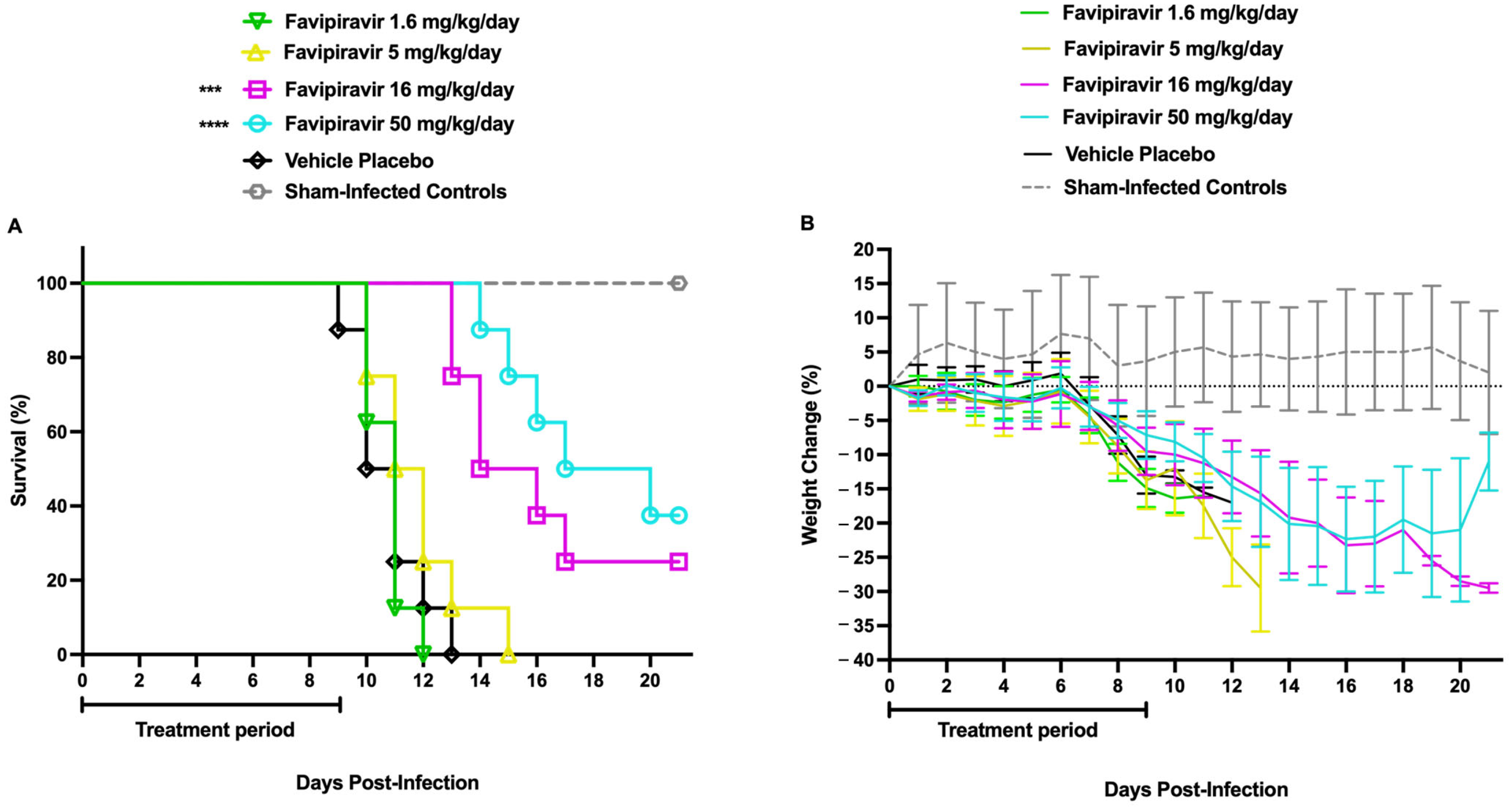

2.4. Determination of the Favipiravir Sub-Optimal Dose in AG129 Mice Challenged with TCRV

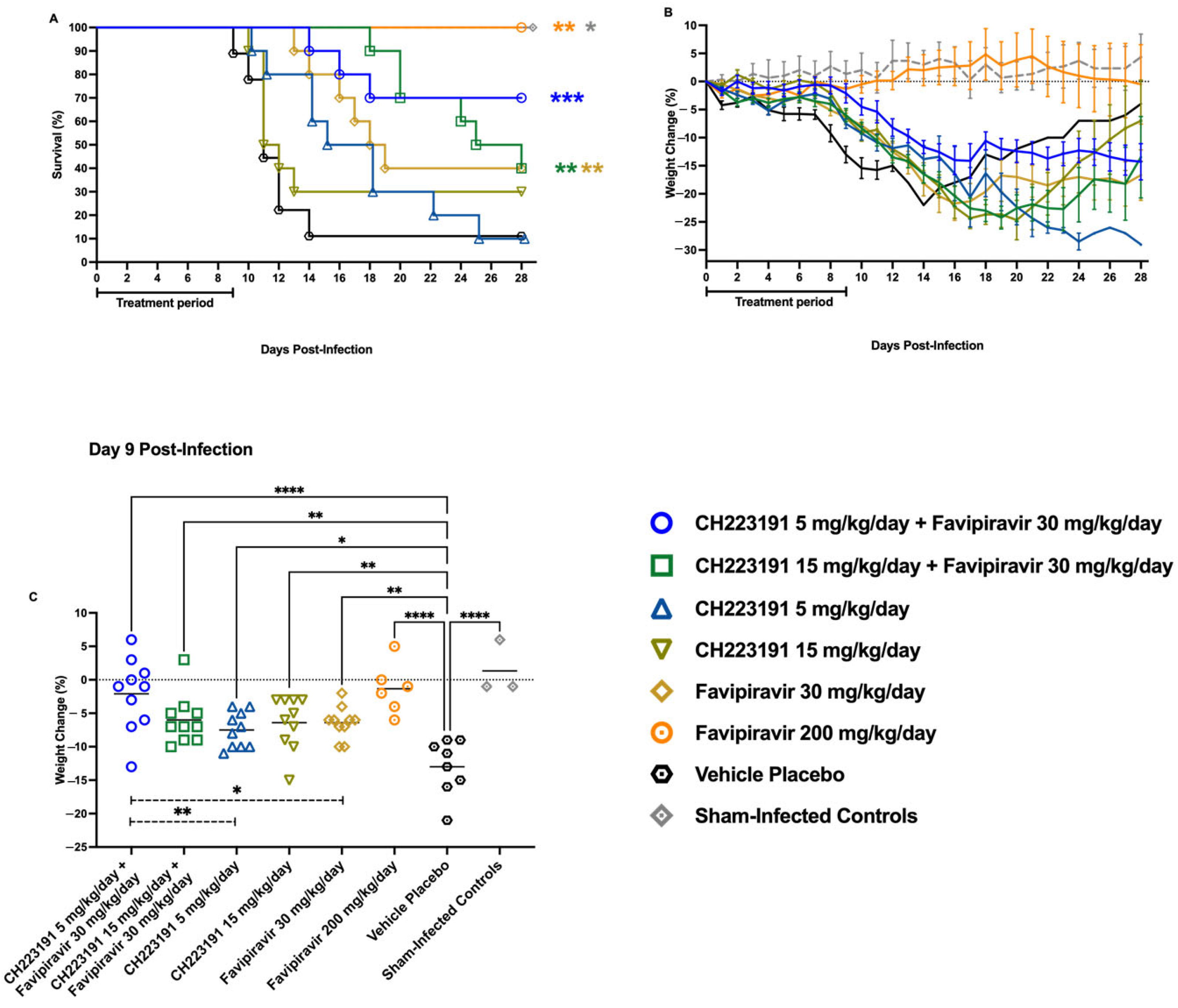

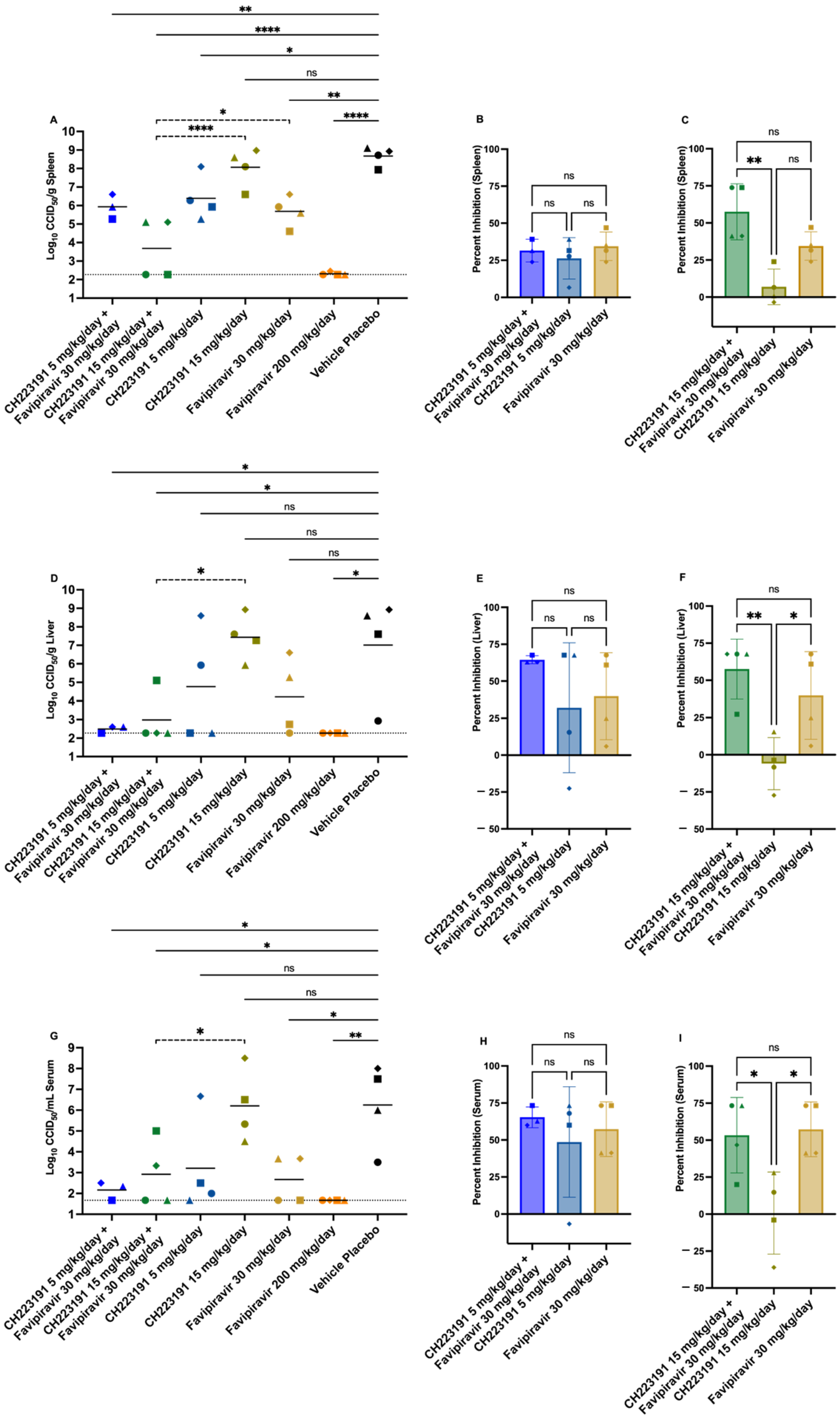

2.5. Effect of CH223191 and Favipiravir Combination Treatment on TCRV-Infected AG129 Mice

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals

4.2. Ethics Regulation of Laboratory Animals

4.3. Cell Cultures

4.4. Viral Strains

4.5. Compounds

4.6. Combined Antiviral Activity of CH223191 and Favipiravir in Cell Culture

4.7. Animal Studies

4.7.1. CH223191 Maximum Tolerated Dose Study

4.7.2. CH223191 Efficacy Study in the hTfR1 JUNV Challenge Model

4.7.3. Favipiravir Sub-Optimal Dose Determination

4.7.4. CH223191 and Favipiravir Combination Study in the AG129 TCRV Challenge Model

4.8. Spleen, Liver, and Serum Virus Titers

4.9. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AHR | Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor |

| JUNV | Junín virus |

| TCRV | Tacaribe virus |

| PO | Per os |

| IP | Intraperitoneal |

| VHF | Viral hemorrhagic fever |

| q.d | Once daily |

| b.i.d | Twice daily |

References

- Abir, M.H.; Rahman, T.; Das, A.; Etu, S.N.; Nafiz, I.H.; Rakib, A.; Mitra, S.; Emran, T.B.; Dhama, K.; Islam, A.; et al. Pathogenicity and Virulence of Marburg Virus. Virulence 2022, 13, 609–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flórez-Álvarez, L.; De Souza, E.E.; Botosso, V.F.; De Oliveira, D.B.L.; Ho, P.L.; Taborda, C.P.; Palmisano, G.; Capurro, M.L.; Pinho, J.R.R.; Ferreira, H.L.; et al. Hemorrhagic Fever Viruses: Pathogenesis, Therapeutics, and Emerging and Re-Emerging Potential. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1040093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnittler, H.; Feldmann, H. Viral Hemorrhagic Fever—A Vascular Disease? Thromb. Haemost. 2003, 89, 967–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira Figueiredo, P.; Stoffella-Dutra, A.G.; Barbosa Costa, G.; Silva De Oliveira, J.; Dourado Amaral, C.; Duarte Santos, J.; Soares Rocha, K.L.; Araújo Júnior, J.P.; Lacerda Nogueira, M.; Zazá Borges, M.A.; et al. Re-Emergence of Yellow Fever in Brazil during 2016–2019: Challenges, Lessons Learned, and Perspectives. Viruses 2020, 12, 1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goenaga, S.; Fabbri, C.; Dueñas, J.C.R.; Gardenal, C.N.; Rossi, G.C.; Calderon, G.; Morales, M.A.; Garcia, J.B.; Enria, D.A.; Levis, S. Isolation of Yellow Fever Virus from Mosquitoes in Misiones Province, Argentina. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2012, 12, 986–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansone, N.M.S.; Boschiero, M.N.; Marson, F.A.L. Dengue Outbreaks in Brazil and Latin America: The New and Continuing Challenges. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2024, 147, 107192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Abri, S.S.; Abaidani, I.A.; Fazlalipour, M.; Mostafavi, E.; Leblebicioglu, H.; Pshenichnaya, N.; Memish, Z.A.; Hewson, R.; Petersen, E.; Mala, P.; et al. Current Status of Crimean-Congo Haemorrhagic Fever in the World Health Organization Eastern Mediterranean Region: Issues, Challenges, and Future Directions. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 58, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Animal Health and Welfare (EFSA AHAW Panel); Nielsen, S.S.; Alvarez, J.; Bicout, D.J.; Calistri, P.; Depner, K.; Drewe, J.A.; Garin-Bastuji, B.; Gonzales Rojas, J.L.; Gortázar Schmidt, C.; et al. Rift Valley Fever—Assessment of Effectiveness of Surveillance and Control Measures in the EU. EFS2 2020, 18, e06292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, M.; Grant, A.; Paessler, S. Epidemiology and Pathogenesis of Bolivian Hemorrhagic Fever. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2014, 5, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Ramos, C.R.; Montoya-Ruíz, C.; Faccini-Martínez, Á.A.; Rodas, J.D. An Updated Review and Current Challenges of Guanarito Virus Infection, Venezuelan Hemorrhagic Fever. Arch. Virol. 2022, 167, 1727–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesh, R.B. Viral Hemorrhagic Fevers of South America. Biomed 2002, 22, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furuta, Y.; Takahashi, K.; Kuno-Maekawa, M.; Sangawa, H.; Uehara, S.; Kozaki, K.; Nomura, N.; Egawa, H.; Shiraki, K. Mechanism of Action of T-705 against Influenza Virus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005, 49, 981–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gowen, B.B.; Juelich, T.L.; Sefing, E.J.; Brasel, T.; Smith, J.K.; Zhang, L.; Tigabu, B.; Hill, T.E.; Yun, T.; Pietzsch, C.; et al. Favipiravir (T-705) Inhibits Junín Virus Infection and Reduces Mortality in a Guinea Pig Model of Argentine Hemorrhagic Fever. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2013, 7, e2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westover, J.B.; Sefing, E.J.; Bailey, K.W.; Van Wettere, A.J.; Jung, K.-H.; Dagley, A.; Wandersee, L.; Downs, B.; Smee, D.F.; Furuta, Y.; et al. Low-Dose Ribavirin Potentiates the Antiviral Activity of Favipiravir against Hemorrhagic Fever Viruses. Antivir. Res. 2016, 126, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veliziotis, I.; Roman, A.; Martiny, D.; Schuldt, G.; Claus, M.; Dauby, N.; Van Den Wijngaert, S.; Martin, C.; Nasreddine, R.; Perandones, C.; et al. Clinical Management of Argentine Hemorrhagic Fever Using Ribavirin and Favipiravir, Belgium, 2020. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 1562–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, V.R.; Afowowe, T.O.; Abe, H.; Urata, S.; Yasuda, J. Potential and Action Mechanism of Favipiravir as an Antiviral against Junin Virus. PLoS Pathog. 2022, 18, e1010689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baz, M.; Carbonneau, J.; Rhéaume, C.; Cavanagh, M.-H.; Boivin, G. Combination Therapy with Oseltamivir and Favipiravir Delays Mortality but Does Not Prevent Oseltamivir Resistance in Immunodeficient Mice Infected with Pandemic A(H1N1) Influenza Virus. Viruses 2018, 10, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westover, J.B.; Bailey, K.W.; Wasson, S.R.; Boardman, K.M.; Lustig, K.H.; Amberg, S.M.; Gowen, B.B. Coadministration of LHF-535 and Favipiravir Protects against Experimental Junín Virus Infection and Disease. Antivir. Res. 2024, 229, 105952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westover, J.B.; Naik, S.; Bailey, K.W.; Wandersee, L.; Gantla, V.R.; Hickerson, B.T.; McCormack, K.; Henkel, G.; Gowen, B.B. Severe Mammarenaviral Disease in Guinea Pigs Effectively Treated by an Orally Bioavailable Fusion Inhibitor, Alone or in Combination with Favipiravir. Antivir. Res. 2022, 208, 105444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannoni, F.; Li, Z.; Remes-Lenicov, F.; Dávola, M.E.; Elizalde, M.; Paletta, A.; Ashkar, A.A.; Mossman, K.L.; Dugour, A.V.; Figueroa, J.M.; et al. AHR Signaling Is Induced by Infection with Coronaviruses. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannoni, F.; Bosch, I.; Polonio, C.M.; Torti, M.F.; Wheeler, M.A.; Li, Z.; Romorini, L.; Rodriguez Varela, M.S.; Rothhammer, V.; Barroso, A.; et al. AHR Is a Zika Virus Host Factor and a Candidate Target for Antiviral Therapy. Nat. Neurosci. 2020, 23, 939–951, Erratum in Nat. Neurosci. 2020, 23, 1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelaez, M.A.; Torti, M.F.; Alvarez De Lauro, A.E.; Marquez, A.B.; Giovannoni, F.; Damonte, E.B.; García, C.C. Modulation of the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Signaling Pathway Impacts on Junín Virus Replication. Viruses 2023, 15, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torti, M.F.; Giovannoni, F.; Quintana, F.J.; García, C.C. The Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor as a Modulator of Anti-Viral Immunity. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 624293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okey, A.B. An Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Odyssey to the Shores of Toxicology: The Deichmann Lecture, International Congress of Toxicology-XI. Toxicol. Sci. 2007, 98, 5–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poland, A.P.; Glover, E.; Robinson, J.R.; Nebert, D.W. Genetic Expression of Aryl Hydrocarbon Hydroxylase Activity. J. Biol. Chem. 1974, 249, 5599–5606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.G.; Yeh, C.Y.; Hsu, S.Y.; Prakash, M.; Abarientos, A.B.; Chiang-Hsieh, H.M.; Lin, Y.Y.; Ortiz, C.L.D.; Yang, L.W.; Liang, P.H.; et al. Dendritic cell-targeted liposomes for cancer immunotherapy via inhibition of aryl hydrocarbon receptor. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2025, 23, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrzal, R.; Grycová, A.; Vrzalová, A. Skin-targeted AhR activation by microbial and synthetic indoles: Insights from the AhaRaCaT reporter cell line. Toxicol. Lett. 2025, 412, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieke, S.; Koehn, S.; Hirsch-Ernst, K.; Pfeil, R.; Kneuer, C.; Marx-Stoelting, P. Combination effects of (tri)azole fungicides on hormone production and xenobiotic metabolism in a human placental cell line. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 9660–9679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oestereich, L.; Rieger, T.; Lüdtke, A.; Ruibal, P.; Wurr, S.; Pallasch, E.; Bockholt, S.; Krasemann, S.; Muñoz-Fontela, C.; Günther, S. Efficacy of Favipiravir Alone and in Combination With Ribavirin in a Lethal, Immunocompetent Mouse Model of Lassa Fever. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 213, 934–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çinarka, H.; Günlüoğlu, G.; Çörtük, M.; Yurt, S.; Kiyik, M.; Koşar, F.; Tanriverdİ, E.; Arslan, M.A.; Baydİlİ, K.N.; Koç, A.S.; et al. The Comparison of Favipiravir and Lopinavir/Ritonavir Combination in COVID-19 Treatment. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2021, 51, 1624–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Ding, Y.; Liu, W.; Liu, S. When AHR signaling pathways meet viral infections. Cell Commun. Signal. 2023, 21, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grycová, A.; Vyhlídalová, B.; Dvořák, Z. The role of aryl hydrocarbon receptor in antiviral immunity: A focus on RNA viruses. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2025, 51, 1255–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggen, D.H.; McKean, M.; Hoffman-Censits, J.H.; Lakhani, N.J.; Alhalabi, O.; Guancial, E.A.; Bashir, B.; Bowman, I.A.; Tan, A.; Lingaraj, T.; et al. IK-175, an Oral AHR Inhibitor, as Monotherapy and in Combination with Nivolumab in Patients with Urothelial Carcinoma Resistant/Refractory to PD-1/L1 Inhibitors. JCO 2024, 42, 2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kober, C.; Roewe, J.; Schmees, N.; Roese, L.; Roehn, U.; Bader, B.; Stoeckigt, D.; Prinz, F.; Gorjánácz, M.; Roider, H.G.; et al. Targeting the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor (AhR) with BAY 2416964: A Selective Small Molecule Inhibitor for Cancer Immunotherapy. J. Immunother. Cancer 2023, 11, e007495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, E. Impact of Infectious and Inflammatory Disease on Cytochrome P450–Mediated Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009, 85, 434–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayden, M.S.; Ghosh, S. NF-κB in Immunobiology. Cell Res. 2011, 21, 223–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Ke, S.; Denison, M.S.; Rabson, A.B.; Gallo, M.A. Ah Receptor and NF-κB Interactions, a Potential Mechanism for Dioxin Toxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 510–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Meglio, P.; Duarte, J.H.; Ahlfors, H.; Owens, N.D.; Li, Y.; Villanova, F.; Tosi, I.; Hirota, K.; Nestle, F.O.; Mrowietz, U.; et al. Activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor dampens the severity of inflammatory skin conditions. Immunity 2014, 40, 989–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockinger, B.; Shah, K.; Wincent, E. AHR in the intestinal microenvironment: Safeguarding barrier function. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 559–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, L.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, L.; Wang, K.; Wang, J.; Liu, X.; Zhao, P.; Li, J. Inhibition of AhR disrupts intestinal epithelial barrier and induces intestinal injury by activating NF-κB in COPD. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2024, 38, e70256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, T.; Horimoto, H.; Kameyama, T.; Hayakawa, S.; Yamato, H.; Dazai, M.; Takada, A.; Kida, H.; Bott, D.; Zhou, A.C.; et al. Constitutive Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Signaling Constrains Type I Interferon–Mediated Antiviral Innate Defense. Nat. Immunol. 2016, 17, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Sosa, M.; Elizondo, G.; López-Durán, R.M.; Rivera, I.; Gonzalez, F.J.; Vega, L. Over-production of IFN-γ and IL-12 in AhR-null Mice. FEBS Lett. 2005, 579, 6403–6410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, T.; Briercheck, E.L.; Freud, A.G.; Trotta, R.; McClory, S.; Scoville, S.D.; Keller, K.; Deng, Y.; Cole, J.; Harrison, N.; et al. The Transcription Factor AHR Prevents the Differentiation of a Stage 3 Innate Lymphoid Cell Subset to Natural Killer Cells. Cell Rep. 2014, 8, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bliss, C.I. The Toxicity Of Poisons Applied Jointly. Ann. Appl. Biol. 1939, 26, 585–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, B.; Wennerberg, K.; Aittokallio, T.; Tang, J. Searching for Drug Synergy in Complex Dose–Response Landscapes Using an Interaction Potency Model. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2015, 13, 504–513, Erratum in Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2017, 15, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emonet, S.F.; Seregin, A.V.; Yun, N.E.; Poussard, A.L.; Walker, A.G.; De La Torre, J.C.; Paessler, S. Rescue from Cloned cDNAs and In Vivo Characterization of Recombinant Pathogenic Romero and Live-Attenuated Candid #1 Strains of Junin Virus, the Causative Agent of Argentine Hemorrhagic Fever Disease. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 1473–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianevski, A.; Giri, A.K.; Aittokallio, T. SynergyFinder 3.0: An Interactive Analysis and Consensus Interpretation of Multi-Drug Synergies across Multiple Samples. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, W739–W743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowen, B.B.; Wong, M.-H.; Jung, K.-H.; Sanders, A.B.; Mendenhall, M.; Bailey, K.W.; Furuta, Y.; Sidwell, R.W. In Vitro and In Vivo Activities of T-705 against Arenavirus and Bunyavirus Infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007, 51, 3168–3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, L.J.; Muench, H. A Simple Method Of Estimating Fifty Per Cent Endpoints. J. Epidem. 1938, 27, 493–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | Infected Y or N | Test Articles & Doses | Survivors/Total a (MDD b ± SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Y | CH223191 5 mg/kg/day + Favipiravir 30 mg/kg/day | 7/10 * (16 ± 2.0) |

| 2 | Y | CH223191 15 mg/kg/day + Favipiravir 30 mg/kg/day | 4/10 (23 ± 3.8 ****) |

| 3 | Y | CH223191 5 mg/kg/day + 0.1 mL CMC | 1/10 (16 ± 4.9 **) |

| 4 | Y | CH223191 15 mg/kg/day + 0.1 mL CMC | 3/10 (11 ± 1.0) |

| 5 | Y | Favipiravir 30 mg/kg/day + 0.1 mL CMC | 4/10 (16 ± 2.3 *) |

| 6 | Y | Favipiravir 200 mg/kg/day | 6/6 ** |

| 7 | Y | 0.1 mL CMC + 0.1 mL CMC | 1/9 (11 ± 1.5) |

| 8 | N | Sham-infected normal controls | 3/3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pelaez, M.A.; Westover, J.B.; Scharton, D.; García, C.C.; Gowen, B.B. Effect of the AHR Inhibitor CH223191 as an Adjunct Treatment for Mammarenavirus Infections. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 1071. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021071

Pelaez MA, Westover JB, Scharton D, García CC, Gowen BB. Effect of the AHR Inhibitor CH223191 as an Adjunct Treatment for Mammarenavirus Infections. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):1071. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021071

Chicago/Turabian StylePelaez, Miguel Angel, Jonna B. Westover, Dionna Scharton, Cybele Carina García, and Brian B. Gowen. 2026. "Effect of the AHR Inhibitor CH223191 as an Adjunct Treatment for Mammarenavirus Infections" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 1071. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021071

APA StylePelaez, M. A., Westover, J. B., Scharton, D., García, C. C., & Gowen, B. B. (2026). Effect of the AHR Inhibitor CH223191 as an Adjunct Treatment for Mammarenavirus Infections. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 1071. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021071