Histopathological and Immunohistochemical Findings in Postmortem Lungs from Mexican Patients with Severe COVID-19

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

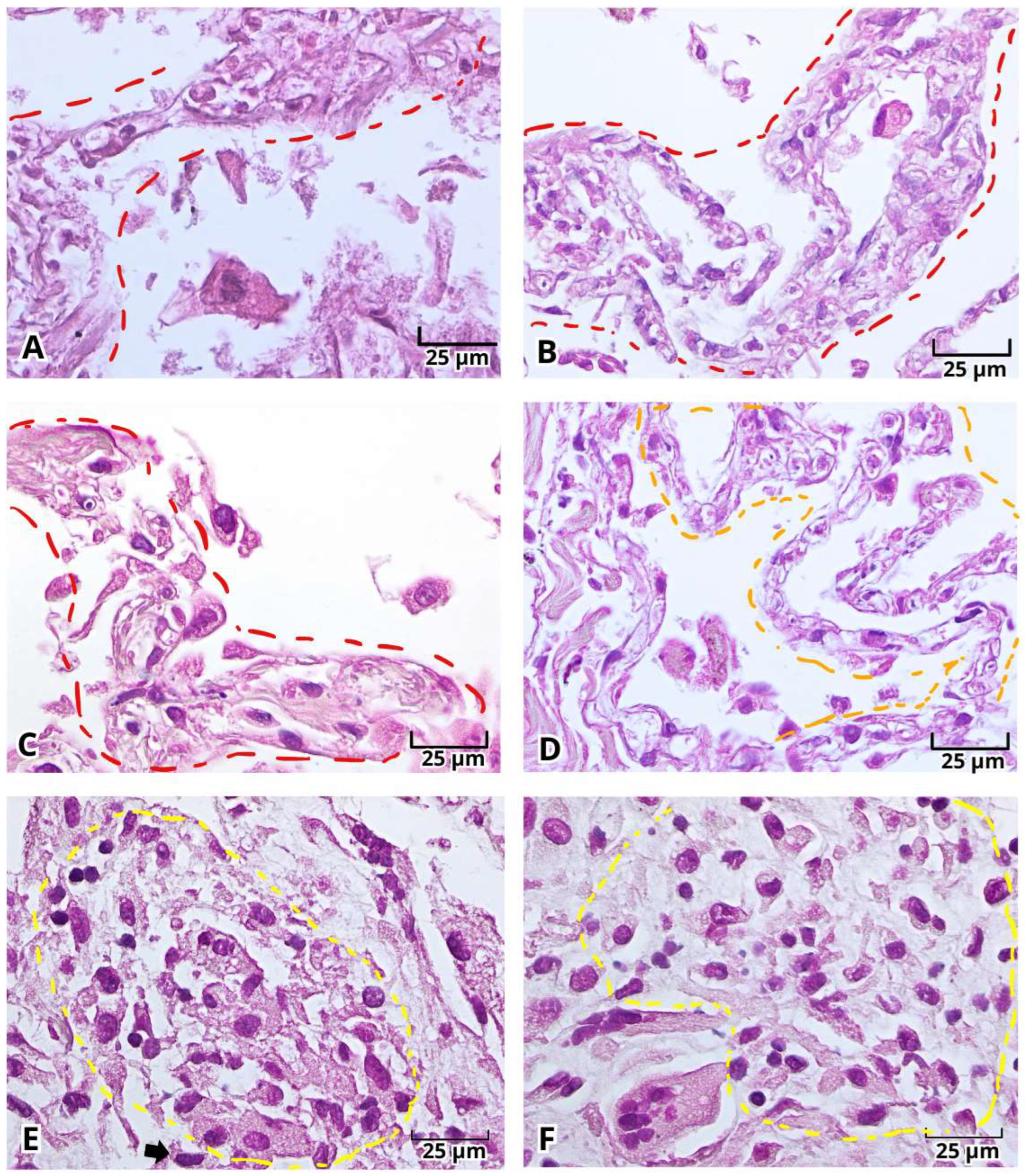

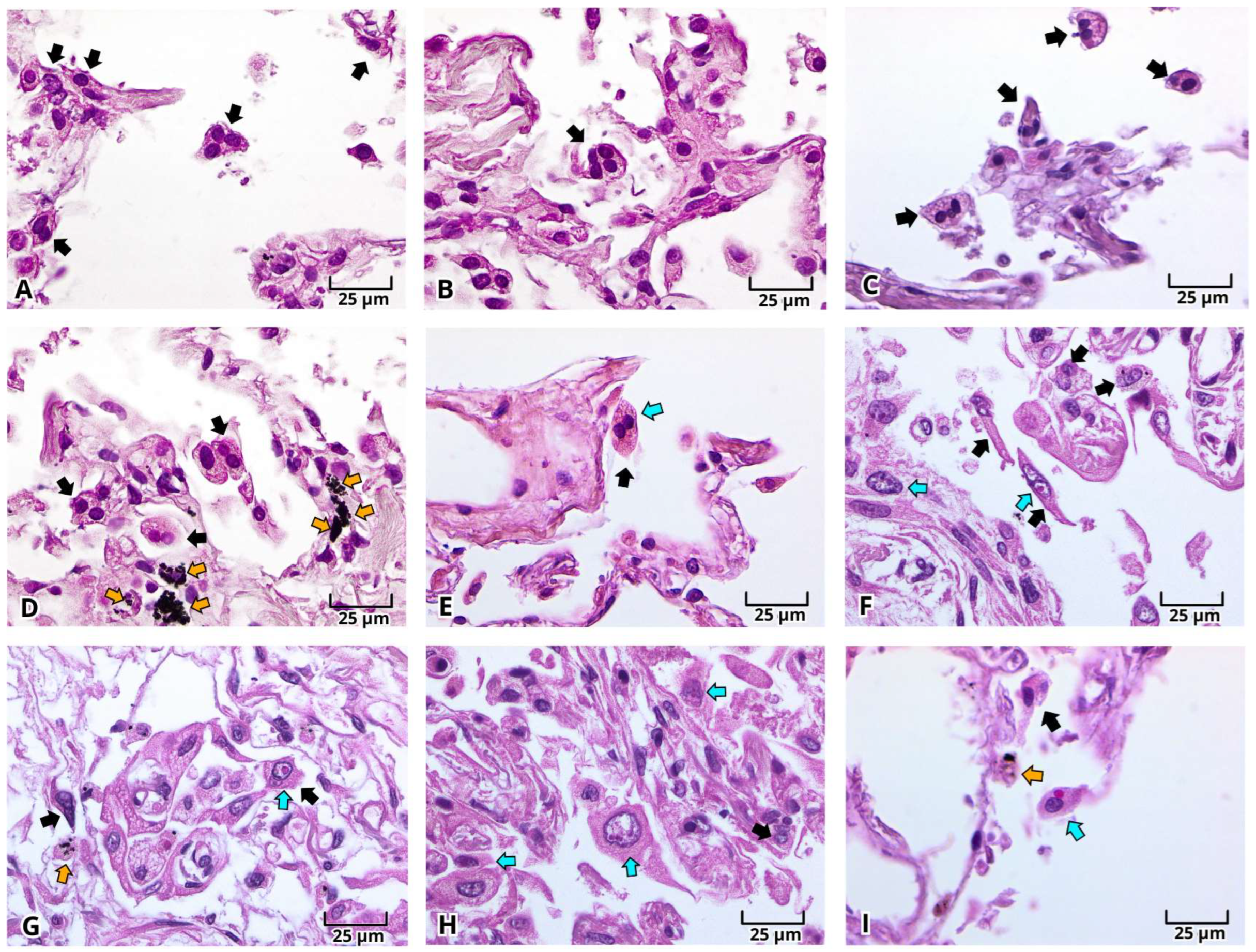

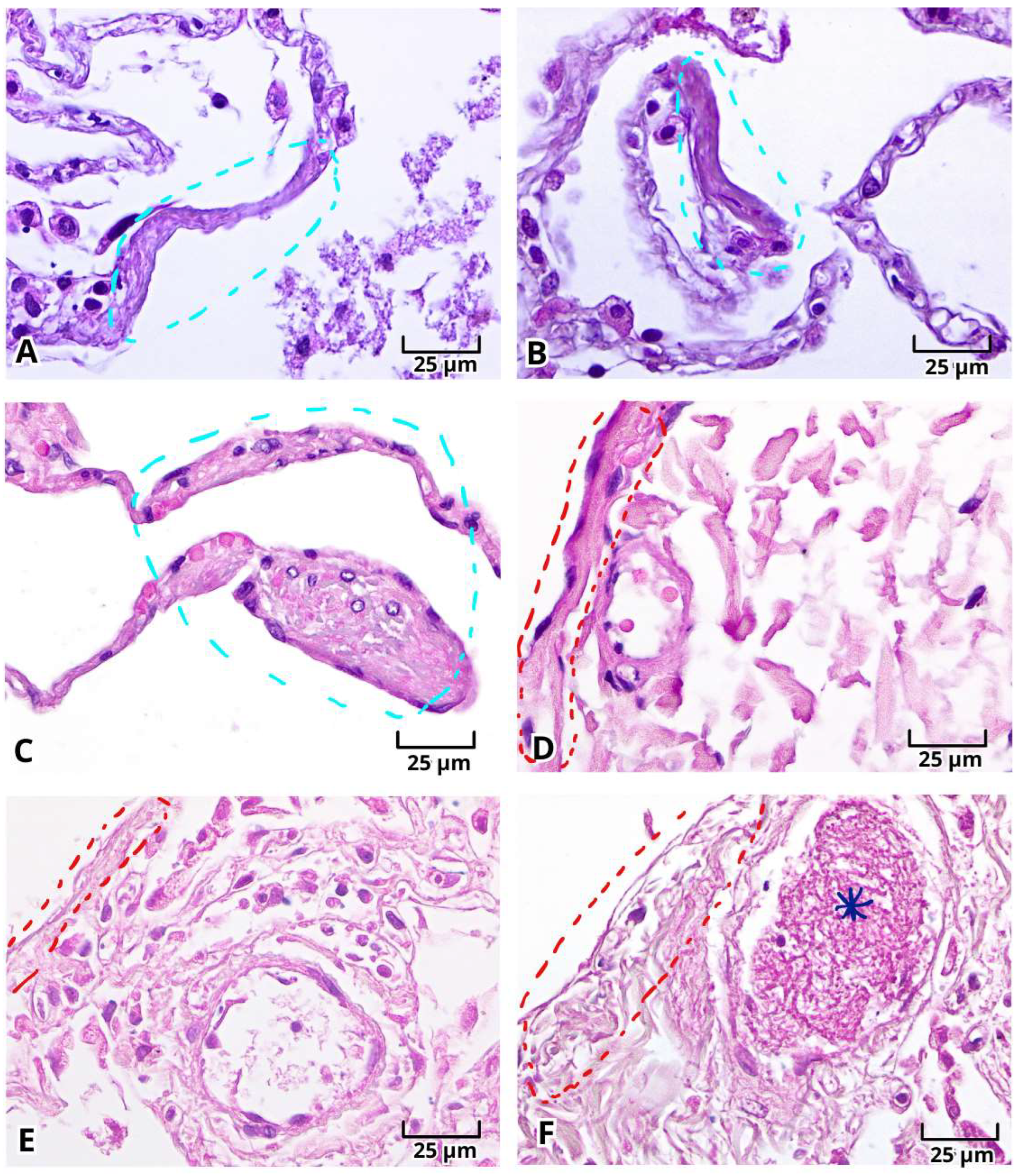

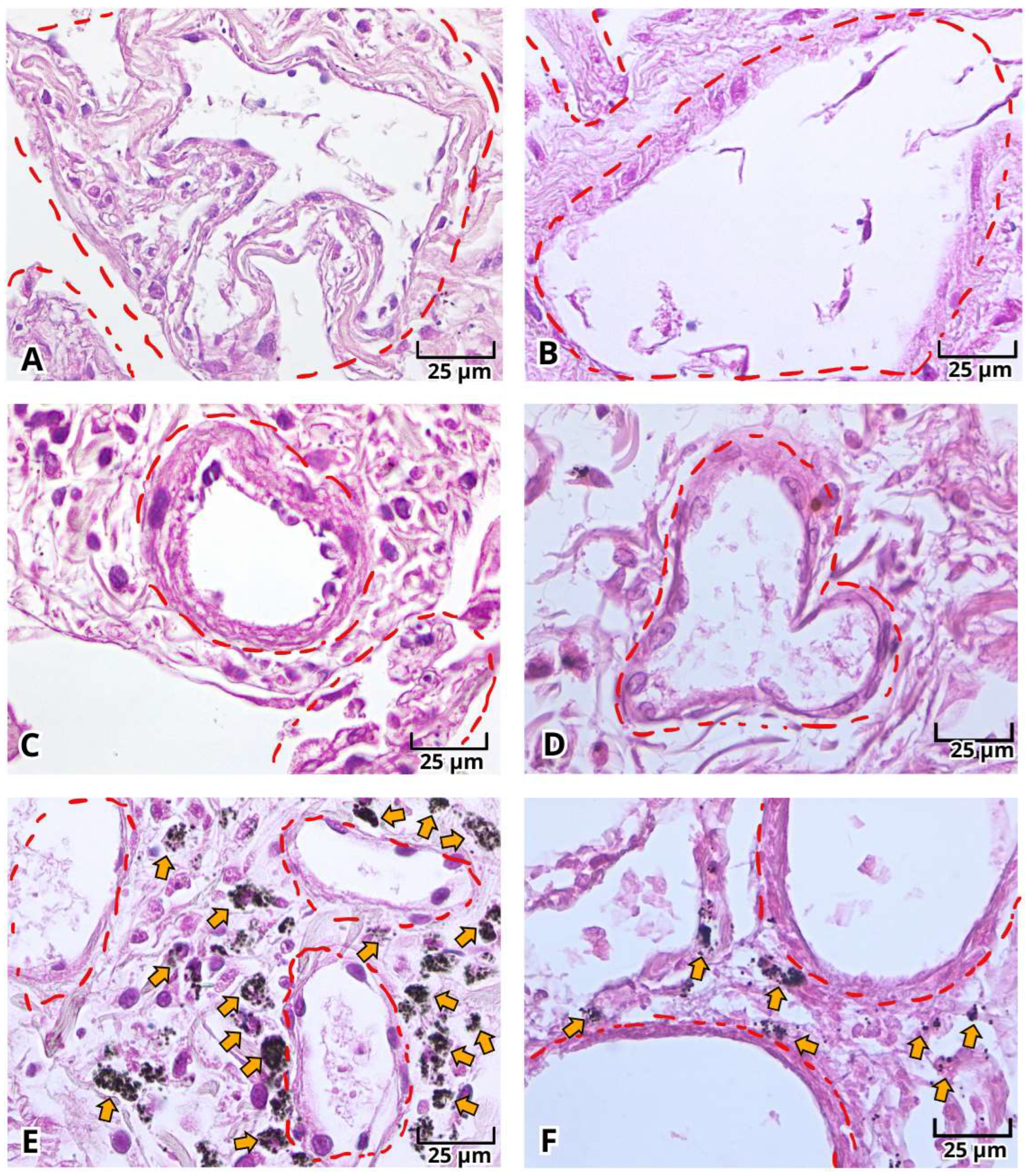

2.1. Histopathologic Findings of Lung Tissue Postmortem Samples from Mexican Patients with Severe COVID-19

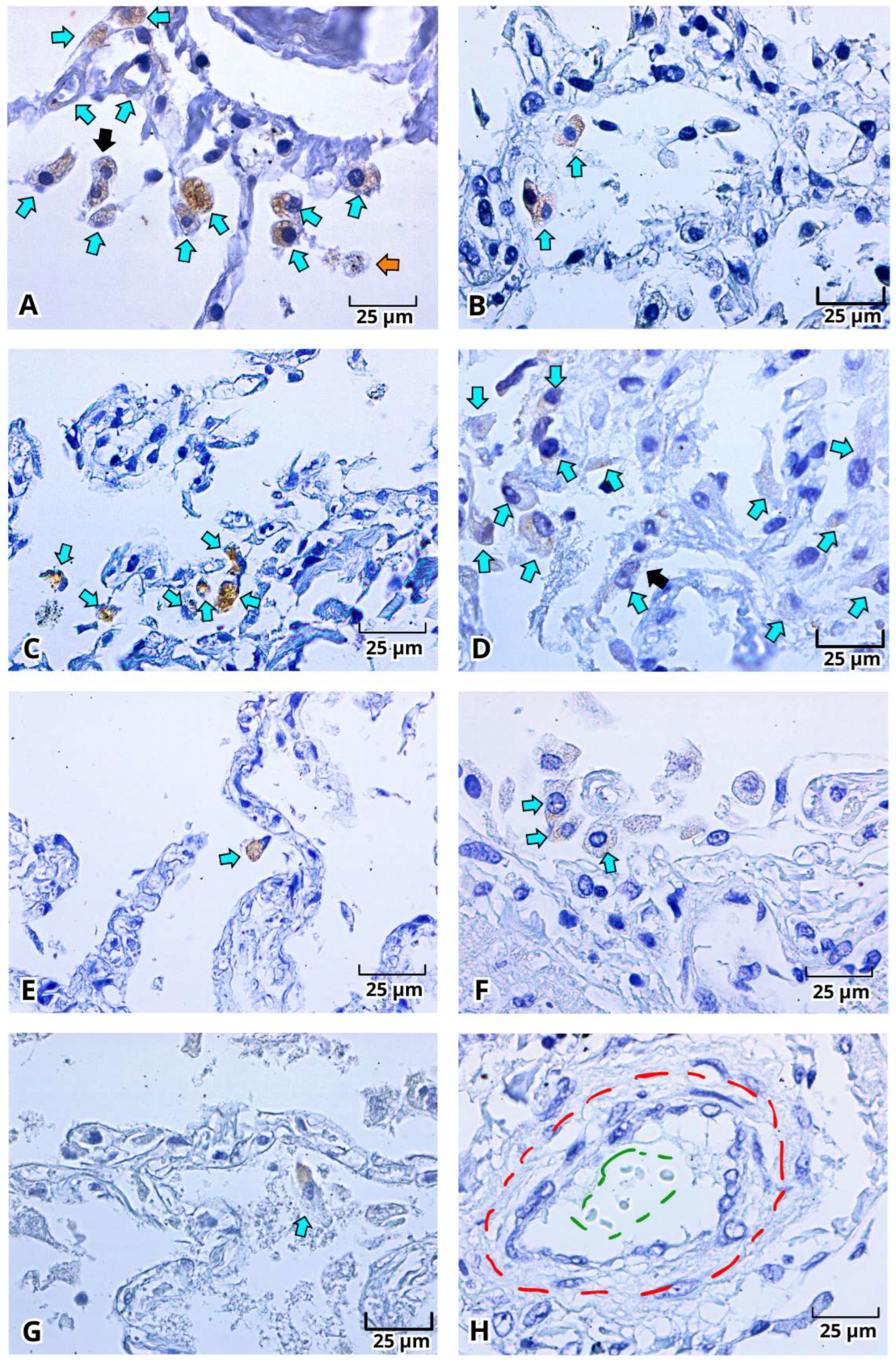

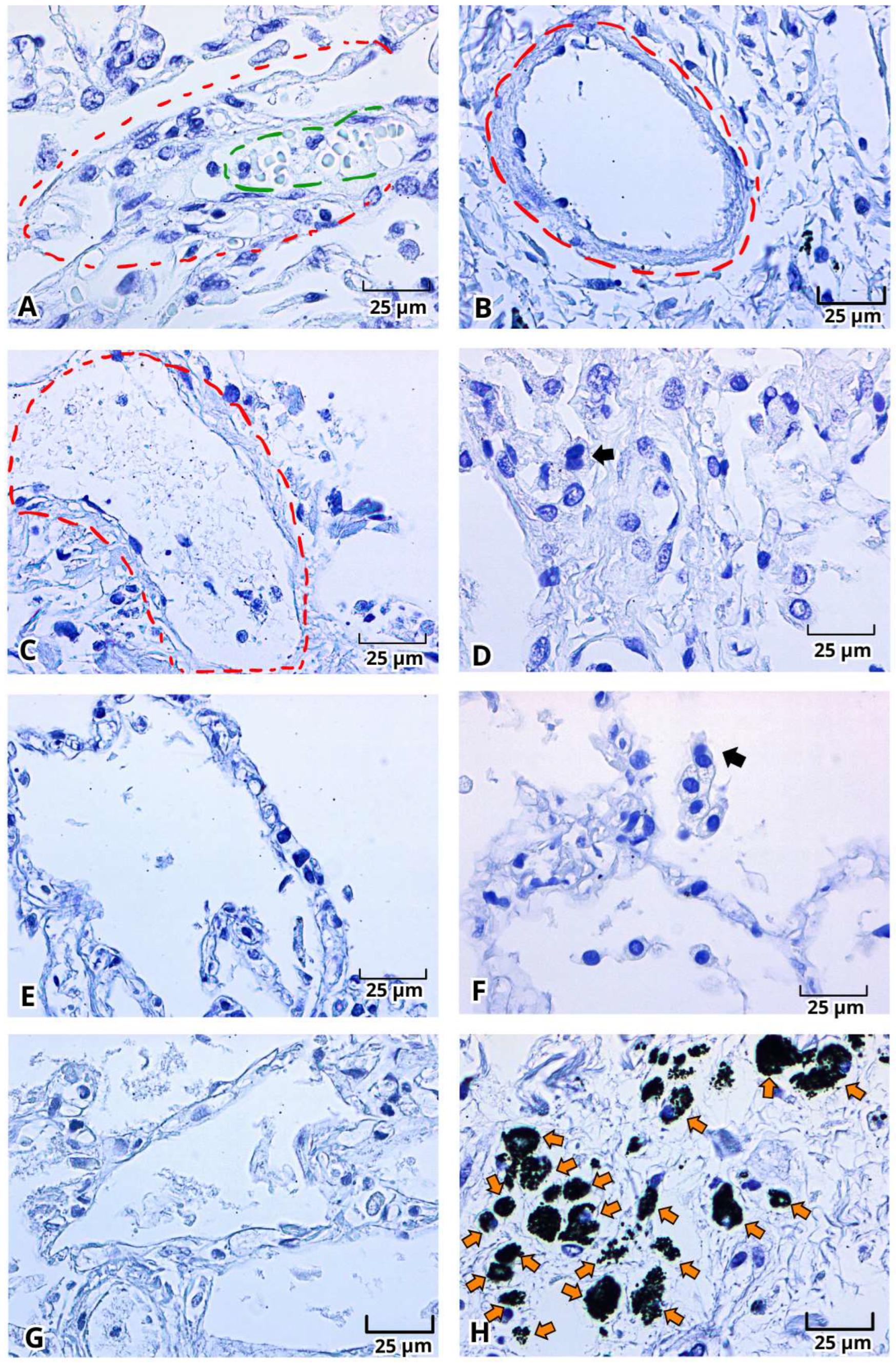

2.2. Histopathological Changes in Deadly COVID-19 Lungs by Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) Staining

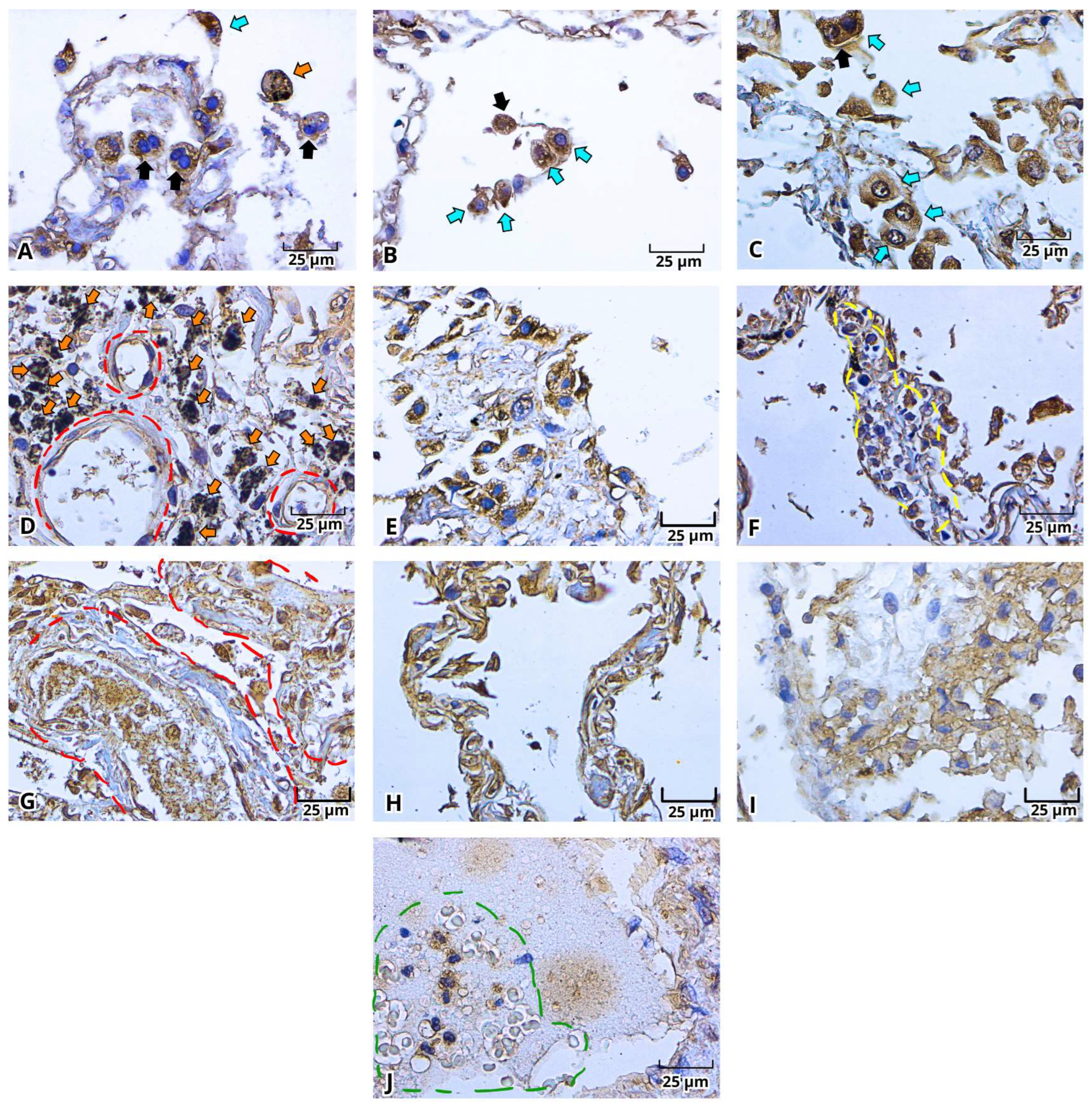

2.3. Immunohistochemistry of the Viral Proteins of SARS-CoV-2: Spike Protein (S) and Nucleocapsid Protein (N) in Lung Postmortem Samples from Mexican Patients with Severe COVID-19

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Lung Tissue Samples

4.2. Tissue Paraffin Embedding

4.3. Hematoxylin-Eosin Staining

4.4. Immunohistochemistry Protocol

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| SARS | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome |

| MERS | Middle East Respiratory Syndrome |

| CoV | Coronaviruses |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 |

| H&E | Hematoxylin and Eosin staining |

| qRT-PCR | Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction. |

| ARDS | Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome |

| DAD | Diffuse Alveolar Damage or Fibrotic DAD |

| PCPF | Post-COVID Pulmonary Fibrosis |

| S | Spike glycoprotein |

| N | Nucleocapsid protein |

| ACE2 | Angiotensin Converting Enzyme 2 |

| COPD | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| TEM | Transmission Electron Microscopy |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| INER | Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Respiratorias |

| DAB | 3,3′-Diaminobenzidine |

References

- Song, Z.; Xu, Y.; Bao, L.; Zhang, L.; Yu, P.; Qu, Y.; Zhu, H.; Zhao, W.; Han, Y.; Qin, C. From SARS to MERS, Thrusting Coronaviruses into the Spotlight. Viruses 2019, 11, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Characterizes COVID-19 as a Pandemic. Available online: https://www.paho.org/en/news/11-3-2020-who-characterizes-covid-19-pandemic (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19). Available online: https://www.paho.org/en/coronavirus-disease-covid-19 (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Escudero, X.; Guarner, J.; Galindo-Fraga, A.; Escudero-Salamanca, M.; Alcocer-Gamba, M.; Del-Río, C. The SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) coronavirus pandemic: Current situation and implications for Mexico. Arch. Cardiol. México 2020, 90, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- 32° Informe Epidemiológico de La Situación de COVID-19. 27 de Septiembre. 2021. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/671470/Informe_COVID-19_2021.09.27.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2025). 27 de Septiembre.

- Kostopanagiotou, K.; Schuurmans, M.; Inci, I.; Hage, R. COVID-19-related end stage lung disease: Two distinct phenotypes. Ann. Med. 2022, 54, 588–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, S.; Magalhães, C.; Teixeira, C.; Eremina, Y. Fibrin strands in peripheral blood smear: The COVID-19 era. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. (CCLM) 2022, 60, e184–e186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falcón-Cama, V.; Montero-González, T.; Acosta-Medina, E.; Guillen-Nieto, G.; Berlanga-Acosta, J.; Fernández-Ortega, C.; Alfonso-Falcón, A.; Gilva-Rodríguez, N.; López-Nocedo, L.; Cremata-García, D.; et al. Evidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in postmortem lung, kidney, and liver samples, revealing cellular targets involved in COVID-19 pathogenesis. Arch. Virol. 2023, 168, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1204–1222. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sardar Saleh, L. The Histological and Immunopathological Landscape of Lung Autopsy Sample of COVID 19: The landscape of Lung Autopsy Sample of COVID 19. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2023, 69, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ICTV Report. Family: Coronaviridae. Available online: https://ictv.global/report/chapter/coronaviridae/coronaviridae (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Gusev, E.; Sarapultsev, A.; Solomatina, L.; Chereshnev, V. SARS-CoV-2-Specific Immune Response and the Pathogenesis of COVID-19. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aho, V.; Myllys, M.; Ruokolainen, V.; Hakanen, S.; Mäntylä, E.; Virtanen, J.; Hukkanen, V.; Kühn, T.; Timonen, J.; Mattila, K.; et al. Chromatin organization regulates viral egress dynamics. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 3692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousif, E.; Premraj, S. A Review of Long COVID with a Special Focus on Its Cardiovascular Manifestations. Cureus 2022, 14, e31932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youd, E.; Moore, L. COVID-19 autopsy in people who died in community settings: The first series. J. Clin. Pathol. 2020, 73, 840–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chrabańska, M.; Mazur, A.; Stęplewska, K. Histopathological pulmonary findings of survivors and autopsy COVID-19 cases: A bi-center study. Medicine 2022, 101, e32002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, V.; Abbas, A.; Aster, J. Robbins & Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 673–678. ISBN 0-3236-0993-7. [Google Scholar]

- Whitsett, J.A.; Alenghat, T. Respiratory epithelial cells orchestrate pulmonary innate immunity. Nat. Immunol. 2015, 16, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alon, R.; Sportiello, M.; Kozlovski, S.; Kumar, A.; Reilly, E.C.; Zarbock, A.; Garbi, N.; Topham, D. Leukocyte trafficking to the lungs and beyond: Lessons from influenza for COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 21, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awatade, N.T.; Wark, P.A.B.; Chan, A.S.L.; Mamun, S.A.A.; Mohd Esa, N.Y.; Matsunaga, K.; Rhee, C.K.; Hansbro, P.M.; Sohal, S.S.; on behalf of the Asian Pacific Society of Respirology (APSR) COPD Assembly. The Complex Association between COPD and COVID-19. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnerty, J.P.; Hussain, A.B.M.A.; Ponnuswamy, A.; Kamil, H.G.; Abdelaziz, A. Asthma and COPD as co-morbidities in patients hospitalised with COVID-19 disease: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pulm. Med. 2023, 23, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pesaresi, M.; Pirani, F.; Tagliabracci, A.; Valsecchi, M.; Procopio, A.; Busardò, F.; Graciotti, L. SARS-CoV-2 identification in lungs, heart and kidney specimens by transmission and scanning electron microscopy. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 24, 5186–5188. [Google Scholar]

| Pathological Findings | Samples | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

| Diffuse alveolar damage | ✓ * | ✓ * | ✓ * | ✓ * | ✓ * | ✓ * | ✓ * | ✓ * | ✓ * |

| Decreased vascular perfusion | ✓ ** | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ ** |

| Leukocyte infiltration | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Type I Pneumocytes damage | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Type II Pneumocytes damage | Ø | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Ø | Ø | Ø |

| Type II Pneumocytes metaplasia | Ø | ✓ | Ø | Ø | Ø | Ø | Ø | Ø | Ø |

| Increased type II Pneumocytes | Ø | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Ø |

| Vacuoles in type II Pneumocytes | Ø | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Ø | ✓ | ✓ | Ø |

| Macrophages with Carbon Inclusions | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Ø | ✓ | Ø | ✓ |

| Increase in alveolar Macrophages | Ø | Ø | ✓ | Ø | Ø | Ø | Ø | Ø | Ø |

| Perivascular fibrosis | ✓ | Ø | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Ø |

| Pleural fibrosis | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ a | ✓ b | Ø | Ø | ✓ | Ø | Ø |

| Alveolar wall fibrosis | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Capillary dilation | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Ø | ✓ | Ø | Ø |

| Detachment of vascular endothelium | Ø | Ø | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Ø | Ø | Ø | Ø |

| Epithelial Cell Detachment | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Ø | ✓ | ✓ |

| Alveolar and Vascular cell detritus | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Ø | ✓ | ✓ |

| Intravascular dead cells | Ø | Ø | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Multinucleated cells | ✓ | ✓ | Ø | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Clot/fibrin inside the blood vessels | ✓ | Ø | Ø | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Collapsed alveoli | Ø | Ø | Ø | Ø | Ø | Ø | Ø | ✓ | Ø |

| Cytoplasmic/Nuclear eosinophilic inclusion bodies | ✓ | Ø | ✓ | Ø | ✓ | Ø | ✓ | Ø | Ø |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chávez Gómez, L.G.; Ríos Valencia, D.G.; Madrigal-Valencia, T.L.; Hernández Mendoza, L.; Pérez-Torres, A.; Tirado Mendoza, R. Histopathological and Immunohistochemical Findings in Postmortem Lungs from Mexican Patients with Severe COVID-19. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 1049. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021049

Chávez Gómez LG, Ríos Valencia DG, Madrigal-Valencia TL, Hernández Mendoza L, Pérez-Torres A, Tirado Mendoza R. Histopathological and Immunohistochemical Findings in Postmortem Lungs from Mexican Patients with Severe COVID-19. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):1049. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021049

Chicago/Turabian StyleChávez Gómez, Laura Guadalupe, Diana Gabriela Ríos Valencia, Tania Lucía Madrigal-Valencia, Lilian Hernández Mendoza, Armando Pérez-Torres, and Rocio Tirado Mendoza. 2026. "Histopathological and Immunohistochemical Findings in Postmortem Lungs from Mexican Patients with Severe COVID-19" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 1049. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021049

APA StyleChávez Gómez, L. G., Ríos Valencia, D. G., Madrigal-Valencia, T. L., Hernández Mendoza, L., Pérez-Torres, A., & Tirado Mendoza, R. (2026). Histopathological and Immunohistochemical Findings in Postmortem Lungs from Mexican Patients with Severe COVID-19. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 1049. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021049