NETosis-Related Biomarkers in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, Rheumatoid Arthritis, Psoriatic Arthritis and Ankylosing Spondylitis: A Comparative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Clinical Characteristics of Sample

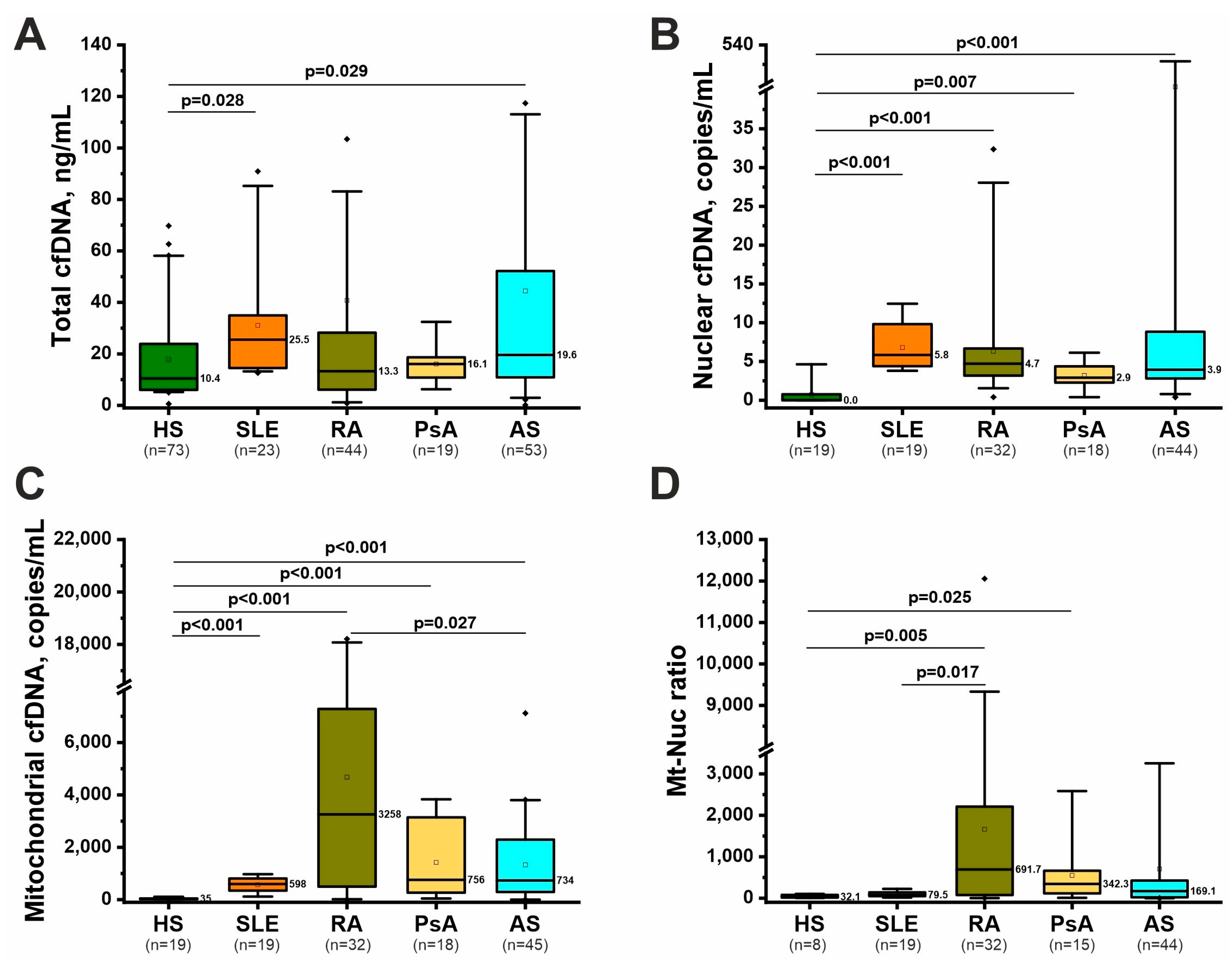

2.2. Nonspecific Markers of NETosis: Total, Nuclear, and Mitochondrial cfDNA

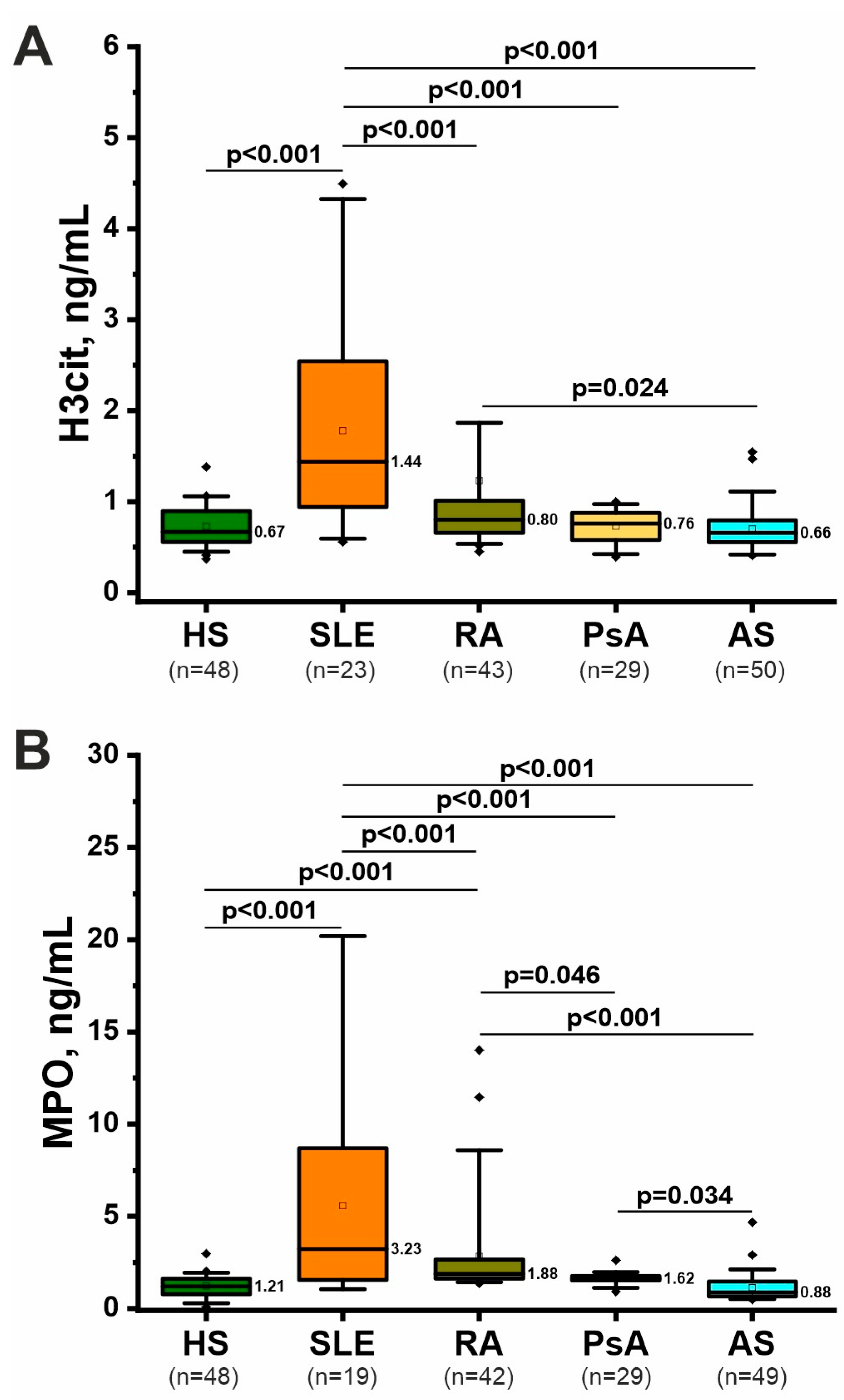

2.3. Specific Markers of NETosis: H3cit and MPO

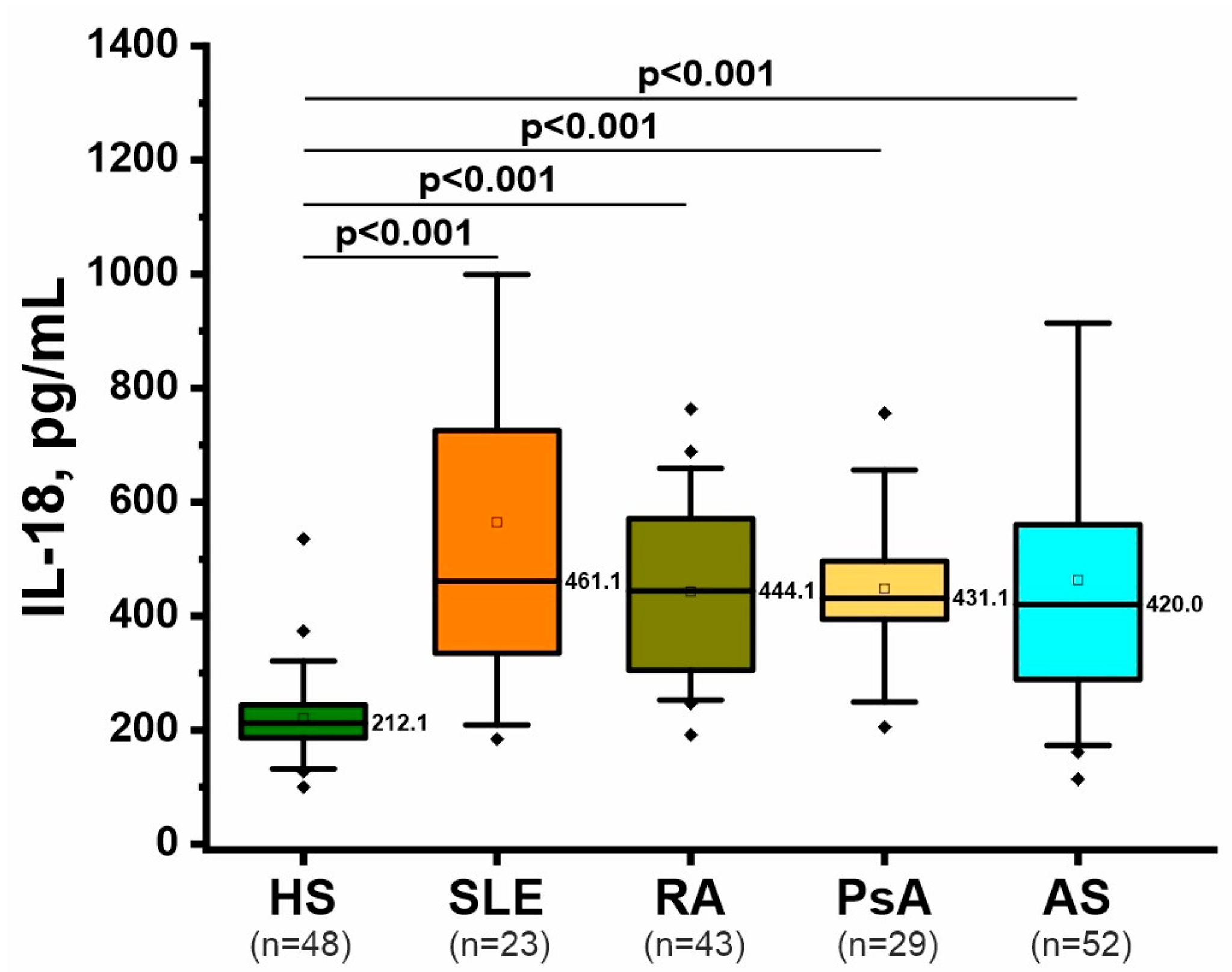

2.4. Inflammatory Marker: IL-18

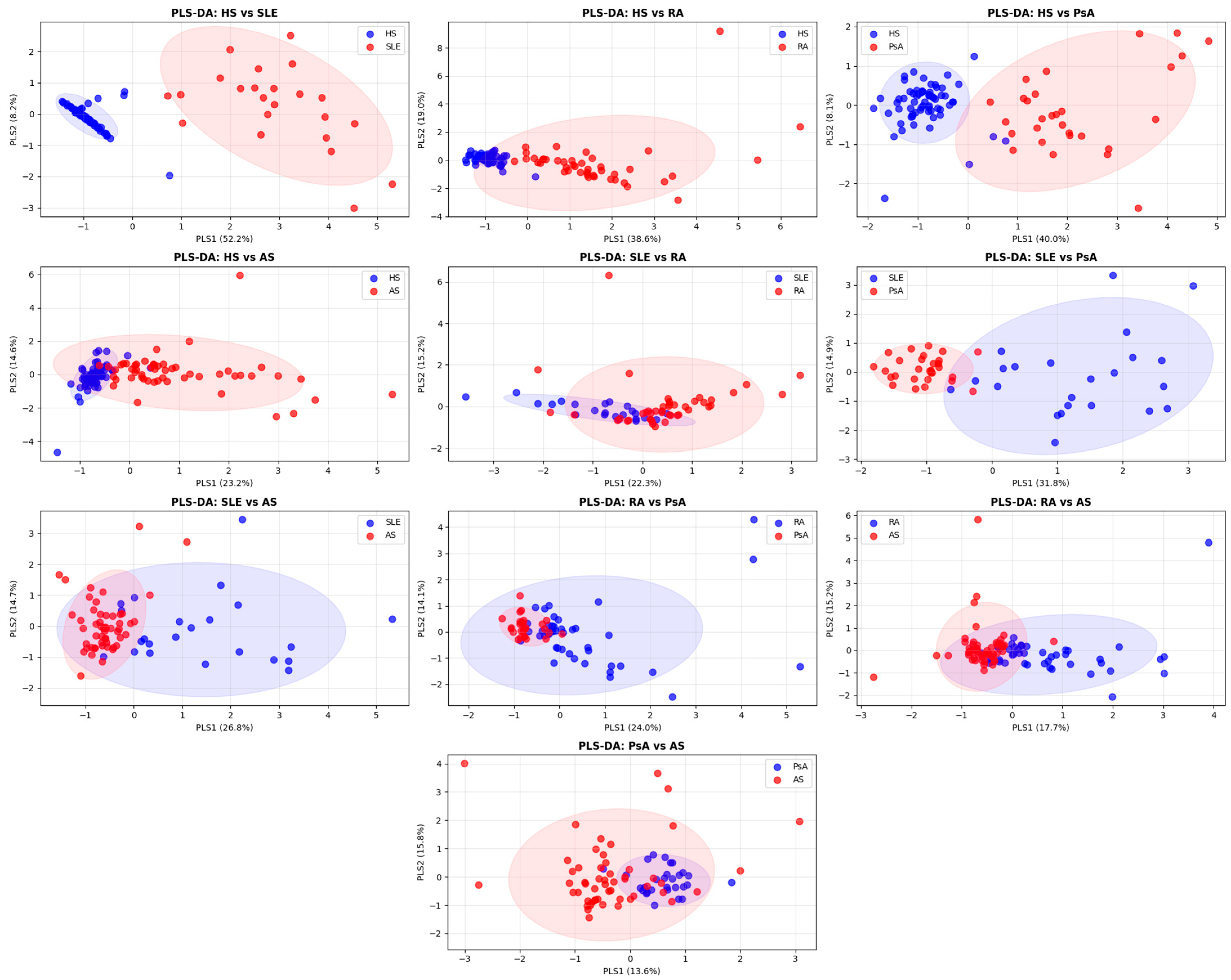

2.5. ROC Analysis and Combined NETosis-Associated Biomarker Profiles

2.6. Clinical Associations

3. Discussion

3.1. Characteristic Changes in NETosis Markers in Four Rheumatic Diseases

3.2. Effect of Therapy on NETosis Markers

3.3. Association of NETosis with CVD and Glomerular Filtration Rate in SLE

3.4. Limitations

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Recruitment of Patients and Healthy Individuals and Clinical Status Assessment

4.2. Obtaining Blood Plasma for Analysis

4.3. Isolation of Total cfDNA from Plasma

4.4. Analysis of Nuclear and Mitochondrial cfDNA by Digital PCR

4.5. H3cit, MPO, IL-18 Analysis by ELISA

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RA | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| AS | Ankylosing spondylitis |

| PsA | Psoriatic arthritis |

| SLE | Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| HS | Healthy subjects |

| ssDNA | Single-stranded DNA |

| scDNA | Supercoiled DNA |

| DAS28 | Disease Activity Score-28 |

| ASDAS | AS disease activity score |

| BASDAI | Bath AS disease activity index |

| DAPSA | Disease activity in psoriatic arthritis |

| SELENA-SLEDAI | Safety of Estrogens in Lupus Erythematosus National Assessment—Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index |

| cfDNA | Cell-free DNA |

| H3cit | Citrullinated Histone H3 |

| MPO | Myeloperoxidase |

| IL | Interleukin |

| bDMARD | biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs |

| csDMARD | conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs |

| PAD4 | peptidyl arginine deaminase 4 |

| CV | coefficient of variation |

References

- Zhang, Z.; Gao, X.; Liu, S.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Hou, S.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y. Global, Regional, and National Epidemiology of Rheumatoid Arthritis among People Aged 20–54 Years from 1990 to 2021. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 10736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, J.; McHugh, N.; Pauling, J.D.; Bruce, I.N.; Charlton, R.; McGrogan, A.; Skeoch, S. Changes in the Incidence and Prevalence of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus between 1990 and 2020: An Observational Study Using the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD). Lupus Sci. Med. 2024, 11, e001213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossfield, S.S.R.; Marzo-Ortega, H.; Kingsbury, S.R.; Pujades-Rodriguez, M.; Conaghan, P.G. Changes in Ankylosing Spondylitis Incidence, Prevalence and Time to Diagnosis over Two Decades. RMD Open 2021, 7, e001888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, A.; Elkayam, P.C.; Stein, N.; Feldhamer, I.; Cohen, A.D.; Saliba, W.; Zisman, D. Epidemiological Trends in Psoriatic Arthritis: A Comprehensive Population-Based Study. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2024, 26, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, R.J.; Cross, M.; Haile, L.M.; Culbreth, G.T.; Steinmetz, J.D.; Hagins, H.; Kopec, J.A.; Brooks, P.M.; Woolf, A.D.; Ong, K.L.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Rheumatoid Arthritis, 1990–2020, and Projections to 2050: A Systematic Analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol. 2023, 5, e594–e610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, E.E.; Barr, S.G.; Clarke, A.E. The Global Burden of SLE: Prevalence, Health Disparities and Socioeconomic Impact. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2016, 12, 605–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lembke, S.; Macfarlane, G.J.; Jones, G.T. The Worldwide Prevalence of Psoriatic Arthritis—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Rheumatology 2024, 63, 3211–3220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Ward, M.M. Epidemiology of Axial Spondyloarthritis: An Update. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2018, 30, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel Baki, N.M.; Raafat, H.A.; El Seidy, H.I.; El Lithy, A.; Alalfy, M.; Khairy, N.A. Utero-Placental and Cerebrovascular Indices in Pregnant Women with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Relation to Disease Activity and Pregnancy Outcome. Egypt. Rheumatol. 2021, 43, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boel, A.; López-Medina, C.; Van Der Heijde, D.M.F.M.; Van Gaalen, F.A. Age at Onset in Axial Spondyloarthritis around the World: Data from the Assessment in SpondyloArthritis International Society Peripheral Involvement in Spondyloarthritis Study. Rheumatology 2022, 61, 1468–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, P.-H.; Wu, O.; Geue, C.; McIntosh, E.; McInnes, I.B.; Siebert, S. Economic Burden of Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Review of Literature in Biologic Era. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2020, 79, 771–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorobjeva, N.V.; Chernyak, B.V. NETosis: Molecular Mechanisms, Role in Physiology and Pathology. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2020, 85, 1178–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, L.; Xiang, W.; Xiao, W.; Wu, Y.; Sun, L. The Emerging Role of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Autoimmune and Autoinflammatory Diseases. MedComm 2025, 6, e70101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odobasic, D.; Yang, Y.; Muljadi, R.C.M.; O’Sullivan, K.M.; Kao, W.; Smith, M.; Morand, E.F.; Holdsworth, S.R. Endogenous Myeloperoxidase Is a Mediator of Joint Inflammation and Damage in Experimental Arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014, 66, 907–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yuan, Y.; Xu, Q.; Jiang, Z.; Chu, C.-Q. Contribution of Neutrophils in the Pathogenesis of Rheumatoid Arthritis. J. Biomed. Res. 2020, 34, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Kim, S.J.; Lei, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, H.; Huang, H.; Zhang, H.; Tsung, A. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Homeostasis and Disease. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aucamp, J.; Bronkhorst, A.J.; Badenhorst, C.P.S.; Pretorius, P.J. The Diverse Origins of Circulating Cell-free DNA in the Human Body: A Critical Re-evaluation of the Literature. Biol. Rev. 2018, 93, 1649–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, H.; Ibrahim, N.; Klopf, J.; Zagrapan, B.; Mauracher, L.-M.; Hell, L.; Hofbauer, T.M.; Ondracek, A.S.; Schoergenhofer, C.; Jilma, B.; et al. ELISA Detection of MPO-DNA Complexes in Human Plasma Is Error-Prone and Yields Limited Information on Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Formed in Vivo. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthelot, J.-M.; Le Goff, B.; Neel, A.; Maugars, Y.; Hamidou, M. NETosis: At the Crossroads of Rheumatoid Arthritis, Lupus, and Vasculitis. Jt. Bone Spine 2017, 84, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Ishikawa, T.; Lai, Y.; Nallapothula, D.; Singh, R.R. Diverse Roles of NETosis in the Pathogenesis of Lupus. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 895216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zambrano-Zaragoza, J.F.; Gutiérrez-Franco, J.; Durán-Avelar, M.D.J.; Vibanco-Pérez, N.; Ortiz-Martínez, L.; Ayón-Pérez, M.F.; Vázquez-Reyes, A.; Agraz-Cibrián, J.M. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps and Inflammatory Response: Implications for the Immunopathogenesis of Ankylosing Spondylitis. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2021, 24, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Li, G.; Yang, X.; Song, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z. NETosis in Psoriatic Arthritis: Serum MPO–DNA Complex Level Correlates with Its Disease Activity. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 911347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tug, S.; Helmig, S.; Menke, J.; Zahn, D.; Kubiak, T.; Schwarting, A.; Simon, P. Correlation between Cell Free DNA Levels and Medical Evaluation of Disease Progression in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Patients. Cell. Immunol. 2014, 292, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelal, I.T.; Zakaria, M.A.; Sharaf, D.M.; Elakad, G.M. Levels of Plasma Cell-Free DNA and Its Correlation with Disease Activity in Rheumatoid Arthritis and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Patients. Egypt. Rheumatol. 2016, 38, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Wu, Y.; Chen, S.; Liu, Y.; Qian, H.; He, Y.; Huang, H.; Cai, M.; Liu, W.; Shi, G. Circulating Cell-Free DNA Correlate to Disease Activity and Treatment Response of Patients with Radiographic Axial Spondyloarthritis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anani, H.A.; Tawfeik, A.M.; Maklad, S.S.; Kamel, A.M.; El-Said, E.E.; Farag, A.S. Circulating Cell-Free DNA as Inflammatory Marker in Egyptian Psoriasis Patients. Psoriasis Targets Ther. 2020, 10, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Wu, C.; Liang, X.; Yang, M. Cell-Free Mitochondrial DNA as a pro-Inflammatory Agent in Blood Circulation: Mechanisms, Therapeutic Implications, and Clinical Challenges in Immune Dysregulation. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1640748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, R.M.S.N.; Silva, N.P.D.; Sato, E.I. Increased Myeloperoxidase Plasma Levels in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Rheumatol. Int. 2012, 32, 1605–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Jian, Z.; Guo, J.; Ning, X. Increased Levels of Serum Myeloperoxidase in Patients with Active Rheumatoid Arthritis. Life Sci. 2014, 117, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Telles, R.W.; Ferreira, G.A.; Silva, N.P.D.; Sato, E.I. Increased Plasma Myeloperoxidase Levels in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Rheumatol. Int. 2010, 30, 779–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishihara, Y.; Kawai, O. Critical Levels of Serum Myeloperoxidase in Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Am. J. Biomed. 2016, 4, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Wu, S.; Wang, W. Correlation of Serum Citrullinated Histone H3 Levels with Disease Activity in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2023, 41, 1792–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurbaeva, K.S.; Reshetnyak, T.M.; Cherkasova, M.V.; Lila, A.M. Citrullinated Histone H3 in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and Antiphospholipid Syndrome (Preliminary Results). Mod. Rheumatol. J. 2023, 17, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruijns, B.; Hoekema, T.; Oomens, L.; Tiggelaar, R.; Gardeniers, H. Performance of Spectrophotometric and Fluorometric DNA Quantification Methods. Analytica 2022, 3, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melamud, M.M.; Buneva, V.N.; Ermakov, E.A. Circulating Cell-Free DNA Levels in Psychiatric Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahlenberg, J.M.; Carmona-Rivera, C.; Smith, C.K.; Kaplan, M.J. Neutrophil Extracellular Trap–Associated Protein Activation of the NLRP3 Inflammasome Is Enhanced in Lupus Macrophages. J. Immunol. 2013, 190, 1217–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoloni, E.; Ludovini, V.; Alunno, A.; Pistola, L.; Bistoni, O.; Crinò, L.; Gerli, R. Increased Levels of Circulating DNA in Patients with Systemic Autoimmune Diseases: A Possible Marker of Disease Activity in Sjögren’s Syndrome. Lupus 2011, 20, 928–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.-Y.; Von Mühlenen, I.; Li, Y.; Kang, A.; Gupta, A.K.; Tyndall, A.; Holzgreve, W.; Hahn, S.; Hasler, P. Increased Concentrations of Antibody-Bound Circulatory Cell-Free DNA in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Clin. Chem. 2007, 53, 1609–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunaeva, M.; Buddingh’, B.C.; Toes, R.E.M.; Luime, J.J.; Lubberts, E.; Pruijn, G.J.M. Decreased Serum Cell-Free DNA Levels in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Autoimmun. Highlights 2015, 6, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendy, O.M.; Motalib, T.A.; El Shafie, M.A.; Khalaf, F.A.; Kotb, S.E.; Khalil, A.; Ali, S.R. Circulating Cell Free DNA as a Predictor of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Severity and Monitoring of Therapy. Egypt. J. Med. Hum. Genet. 2016, 17, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, R.; Sawamura, S.; Kajihara, I.; Miyauchi, H.; Urata, K.; Otsuka-Maeda, S.; Kanemaru, H.; Kanazawa-Yamada, S.; Honda, N.; Makino, K.; et al. Circulating Tumor Necrosis Factor-α DNA Are Elevated in Psoriasis. J. Dermatol. 2020, 47, 1037–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-T.; Lin, C.-S.; Pan, S.-C.; Chen, W.-S.; Tsai, C.-Y.; Wei, Y.-H. The Role of Plasma Cell-Free Mitochondrial DNA and Nuclear DNA in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Front. Biosci.-Landmark 2022, 27, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truszewska, A.; Wirkowska, A.; Gala, K.; Truszewski, P.; Krzemień-Ojak, Ł.; Perkowska-Ptasińska, A.; Mucha, K.; Pączek, L.; Foroncewicz, B. Cell-Free DNA Profiling in Patients with Lupus Nephritis. Lupus 2020, 29, 1759–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rykova, E.; Sizikov, A.; Roggenbuck, D.; Antonenko, O.; Bryzgalov, L.; Morozkin, E.; Skvortsova, K.; Vlassov, V.; Laktionov, P.; Kozlov, V. Circulating DNA in Rheumatoid Arthritis: Pathological Changes and Association with Clinically Used Serological Markers. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2017, 19, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaglis, S.; Daoudlarian, D.; Voll, R.E.; Kyburz, D.; Venhoff, N.; Walker, U.A. Circulating Mitochondrial DNA Copy Numbers Represent a Sensitive Marker for Diagnosis and Monitoring of Disease Activity in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. RMD Open 2021, 7, e002010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.; Giaglis, S.; Kyburz, D.; Daoudlarian, D.; Walker, U.A. Plasma mtDNA as a Possible Contributor to and Biomarker of Inflammation in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2024, 26, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modestino, L.; Tumminelli, M.; Mormile, I.; Cristinziano, L.; Ventrici, A.; Trocchia, M.; Ferrara, A.L.; Palestra, F.; Loffredo, S.; Marone, G.; et al. Neutrophil Exhaustion and Impaired Functionality in Psoriatic Arthritis Patients. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1448560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, S.; Kitching, A.R.; Witko-Sarsat, V.; Wiech, T.; Specks, U.; Klapa, S.; Comdühr, S.; Stähle, A.; Müller, A.; Lamprecht, P. Myeloperoxidase-Specific Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibody-Associated Vasculitis. Lancet Rheumatol. 2024, 6, e300–e313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arroyo-Andrés, J.; Gotor Rivera, A.; Díaz-Benito, B.; Moraga, A.; Lizasoain Hernández, I.; Rivera-Díaz, R. Neutrophil Extracellular Trap (NET) Markers in Psoriasis: Linking with Disease Severity and Comorbidities. Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas 2025, 116, 1131–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yazici, C. Protein Oxidation Status in Patients with Ankylosing Spondylitis. Rheumatology 2004, 43, 1235–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilev, G.; Manolova, I.; Ivanova, M.; Stanilov, I.; Miteva, L.; Stanilova, S. The Role of IL-18 in Addition to Th17 Cytokines in Rheumatoid Arthritis Development and Treatment in Women. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 15391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mende, R.; Vincent, F.B.; Kandane-Rathnayake, R.; Koelmeyer, R.; Lin, E.; Chang, J.; Hoi, A.Y.; Morand, E.F.; Harris, J.; Lang, T. Analysis of Serum Interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-18 in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonek, K.; Kuca-Warnawin, E.; Kornatka, A.; Zielińska, A.; Wisłowska, M.; Kontny, E.; Głuszko, P. Associations of IL-18 with Altered Cardiovascular Risk Profile in Psoriatic Arthritis and Ankylosing Spondylitis. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Sánchez, C.; Ruiz-Limón, P.; Aguirre, M.A.; Jiménez-Gómez, Y.; Arias-de La Rosa, I.; Ábalos-Aguilera, M.C.; Rodriguez-Ariza, A.; Castro-Villegas, M.C.; Ortega-Castro, R.; Segui, P.; et al. Diagnostic Potential of NETosis-Derived Products for Disease Activity, Atherosclerosis and Therapeutic Effectiveness in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients. J. Autoimmun. 2017, 82, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Limon, P.; Ladehesa-Pineda, M.L.; Castro-Villegas, M.D.C.; Abalos-Aguilera, M.D.C.; Lopez-Medina, C.; Lopez-Pedrera, C.; Barbarroja, N.; Espejo-Peralbo, D.; Gonzalez-Reyes, J.A.; Villalba, J.M.; et al. Enhanced NETosis Generation in Radiographic Axial Spondyloarthritis: Utility as Biomarker for Disease Activity and Anti-TNF-α Therapy Effectiveness. J. Biomed. Sci. 2020, 27, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Offenheim, R.; Cruz-Correa, O.F.; Ganatra, D.; Gladman, D.D. Candidate Biomarkers for Response to Treatment in Psoriatic Disease. J. Rheumatol. 2024, 51, 1176–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Jiao, Y.; An, X.; Tu, Q.; Jiang, Q. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps and Cardiovascular Disease: Associations and Potential Therapeutic Approaches. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 180, 117476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, J.; Hennen, E.M.; Ao, M.; Kirabo, A.; Ahmad, T.; De La Visitación, N.; Patrick, D.M. NETosis Drives Blood Pressure Elevation and Vascular Dysfunction in Hypertension. Circ. Res. 2024, 134, 1483–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Z.; Li, L.; Shun, Z.; Xiaoyu, Z.; Wenfei, M.; Hong, Y.; Ruixian, Z. Exploring Endothelial Dysfunction in SLE: cGAS-STING-IRF3 Pathway Activation by dsDNA. Lupus 2025, 34, 1377–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, S.; Caliste, M.; Petretto, A.; Corsiero, E.; Grinovero, N.; Capozzi, A.; Riitano, G.; Barbati, C.; Truglia, S.; Alessandri, C.; et al. Anti-Β2glycoprotein I-Induced Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Cause Endothelial Activation. Rheumatology 2025, 64, 4796–4805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Dhalla, N.S. The Role of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines in the Pathogenesis of Cardiovascular Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melamud, M.M.; Ermakov, E.A.; Boiko, A.S.; Parshukova, D.A.; Sizikov, A.E.; Ivanova, S.A.; Nevinsky, G.A.; Buneva, V.N. Serum Cytokine Levels of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Patients in the Presence of Concomitant Cardiovascular Diseases. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord.—Drug Targets 2022, 22, 852–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermakov, E.A.; Melamud, M.M.; Boiko, A.S.; Ivanova, S.A.; Sizikov, A.E.; Nevinsky, G.A.; Buneva, V.N. Blood Growth Factor Levels in Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: High Neuregulin-1 Is Associated with Comorbid Cardiovascular Pathology. Life 2024, 14, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansildaar, R.; Vedder, D.; Baniaamam, M.; Tausche, A.-K.; Gerritsen, M.; Nurmohamed, M.T. Cardiovascular Risk in Inflammatory Arthritis: Rheumatoid Arthritis and Gout. Lancet Rheumatol. 2021, 3, e58–e70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juha, M.; Molnár, A.; Jakus, Z.; Ledó, N. NETosis: An Emerging Therapeutic Target in Renal Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1253667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lyu, Y.; Tu, K.; Xu, Q.; Yang, Y.; Salman, S.; Le, N.; Lu, H.; Chen, C.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Histone Citrullination by PADI4 Is Required for HIF-Dependent Transcriptional Responses to Hypoxia and Tumor Vascularization. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabe3771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panimolle, F.; Tiberti, C.; Spaziani, M.; Riitano, G.; Lucania, G.; Anzuini, A.; Lenzi, A.; Gianfrilli, D.; Sorice, M.; Radicioni, A.F. Non-Organ-Specific Autoimmunity in Adult 47,XXY Klinefelter Patients and Higher-Grade X-Chromosome Aneuploidies. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2021, 205, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aletaha, D.; Neogi, T.; Silman, A.J.; Funovits, J.; Felson, D.T.; Bingham, C.O.; Birnbaum, N.S.; Burmester, G.R.; Bykerk, V.P.; Cohen, M.D.; et al. 2010 Rheumatoid Arthritis Classification Criteria: An American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism Collaborative Initiative. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010, 69, 1580–1588, Correction in Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010, 69, 1892. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2010.138461corr1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linden, S.V.D.; Valkenburg, H.A.; Cats, A. Evaluation of Diagnostic Criteria for Ankylosing Spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum. 1984, 27, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudwaleit, M.; Van Der Heijde, D.; Landewe, R.; Listing, J.; Akkoc, N.; Brandt, J.; Braun, J.; Chou, C.T.; Collantes-Estevez, E.; Dougados, M.; et al. The Development of Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society Classification Criteria for Axial Spondyloarthritis (Part II): Validation and Final Selection. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2009, 68, 777–783, Correction in Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2019, 78, E59. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2009.108233corr1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, W.; Gladman, D.; Helliwell, P.; Marchesoni, A.; Mease, P.; Mielants, H. Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis: Development of New Criteria from a Large International Study. Arthritis Rheum. 2006, 54, 2665–2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aringer, M.; Costenbader, K.; Daikh, D.; Brinks, R.; Mosca, M.; Ramsey-Goldman, R.; Smolen, J.S.; Wofsy, D.; Boumpas, D.T.; Kamen, D.L.; et al. 2019 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology Classification Criteria for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2019, 78, 1151–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prevoo, M.L.L.; Van’T Hof, M.A.; Kuper, H.H.; Van Leeuwen, M.A.; Van De Putte, L.B.A.; Van Riel, P.L.C.M. Modified Disease Activity Scores That Include Twenty-Eight-Joint Counts Development and Validation in a Prospective Longitudinal Study of Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis: MODIFIED DISEASE ACTIVITY SCORE. Arthritis Rheum. 1995, 38, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinbrocker, O. Therapeutic Criteria in Rheumatoid Arthritis. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1949, 140, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukas, C.; Landewé, R.; Sieper, J.; Dougados, M.; Davis, J.; Braun, J.; Van Der Linden, S.; Van Der Heijde, D.; for the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society. Development of an ASAS-Endorsed Disease Activity Score (ASDAS) in Patients with Ankylosing Spondylitis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2009, 68, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, P.; Landewe, R.; Lie, E.; Kvien, T.K.; Braun, J.; Baker, D.; Van Der Heijde, D.; for the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society. Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS): Defining Cut-off Values for Disease Activity States and Improvement Scores. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2011, 70, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoels, M.; Aletaha, D.; Funovits, J.; Kavanaugh, A.; Baker, D.; Smolen, J.S. Application of the DAREA/DAPSA Score for Assessment of Disease Activity in Psoriatic Arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010, 69, 1441–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petri, M.; Kim, M.Y.; Kalunian, K.C.; Grossman, J.; Hahn, B.H.; Sammaritano, L.R.; Lockshin, M.; Merrill, J.T.; Belmont, H.M.; Askanase, A.D.; et al. Combined Oral Contraceptives in Women with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 353, 2550–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancia, G.; Kreutz, R.; Brunström, M.; Burnier, M.; Grassi, G.; Januszewicz, A.; Muiesan, M.L.; Tsioufis, K.; Agabiti-Rosei, E.; Algharably, E.A.E.; et al. 2023 ESH Guidelines for the Management of Arterial Hypertension The Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension: Endorsed by the International Society of Hypertension (ISH) and the European Renal Association (ERA). J. Hypertens. 2023, 41, 1874–2071, Erratum in J. Hypertens. 2023, 42, 194. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0000000000003621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caforio, A.L.P.; Adler, Y.; Agostini, C.; Allanore, Y.; Anastasakis, A.; Arad, M.; Böhm, M.; Charron, P.; Elliott, P.M.; Eriksson, U.; et al. Diagnosis and Management of Myocardial Involvement in Systemic Immune-Mediated Diseases: A Position Statement of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Myocardial and Pericardial Disease. Eur. Heart J. 2017, 38, 2649–2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiner, Z.; Catapano, A.L.; De Backer, G.; Graham, I.; Taskinen, M.-R.; Wiklund, O.; Agewall, S.; Alegria, E.; Chapman, M.J.; Durrington, P.; et al. ESC/EAS Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidaemias: The Task Force for the Management of Dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS). Eur. Heart J. 2011, 32, 1769–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trumpff, C.; Michelson, J.; Lagranha, C.J.; Taleon, V.; Karan, K.R.; Sturm, G.; Lindqvist, D.; Fernström, J.; Moser, D.; Kaufman, B.A.; et al. Stress and Circulating Cell-Free Mitochondrial DNA: A Systematic Review of Human Studies, Physiological Considerations, and Technical Recommendations. Mitochondrion 2021, 59, 225–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tombuloglu, H.; Sabit, H.; Al-Khallaf, H.; Kabanja, J.H.; Alsaeed, M.; Al-Saleh, N.; Al-Suhaimi, E. Multiplex Real-Time RT-PCR Method for the Diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 by Targeting Viral N, RdRP and Human RP Genes. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trumpff, C.; Marsland, A.L.; Basualto-Alarcón, C.; Martin, J.L.; Carroll, J.E.; Sturm, G.; Vincent, A.E.; Mosharov, E.V.; Gu, Z.; Kaufman, B.A.; et al. Acute Psychological Stress Increases Serum Circulating Cell-Free Mitochondrial DNA. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019, 106, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Feature 1 | RA (n = 44) (1) | AS (n = 53) (2) | PsA (n = 30) (3) | SLE (n = 23) (4) | HS (n = 73) (5) | p-Value 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (M/F), % | 25/75 | 69/31 | 30/70 | 0/100 | 30/70 | <0.01 |

| Age, years | 49.5 ± 12.6 | 44.9 ± 12.1 | 45.1 ± 12.9 | 44.1 ± 16.0 | 37.8 ± 12.8 | 1 vs. 5: <0.001 2 vs. 5: <0.02 |

| Disease duration, years | 8 (4.75–15) | 12 (8–22) | 10 (3–21) | 6 (3–12) | – | 2 vs. 4: <0.01 |

| BMI | 26 (23–28) | 26 (21–28) | 26 (21–30) | 25 (21–28) | 23 (20–26) | 1 vs. 5: <0.02 |

| ESR, mm/h | 2.6 (0.8–11.3) | 2.8 (1.1–6.2) | 4.3 (2.4–9.8) | 2.2 (0.8–8.9) | – | 0.19 |

| CRP, mg/L | 14.5 (6.5–28) | 10 (4–18) | 16 (10–26) | 15 (8.5–38) | – | 0.5 |

| Anti-dsDNA antibodies, IU/mL | 2.6 (0.67–5.2) | 1.8 (0.88–3.9) | – | 21.4 (8.8–117) | 0.45 (0–1.8) | 1 vs. 4: <0.001; 1 vs. 5: <0.02; 2 vs. 4: <0.001 4 vs. 5: <0.0001 |

| Clinical index | DAS28: 3.4 (2.6–4.5) | ASDAS-CRP: 1.7 (1.3–2.5); ASDAS-ESR: 1.8 (1.31–2.6); BASDAI: 1.9 (1.0–3.2) | DAS28: 3.5 (1–9.4); DAPSA: 14 (6–22) | SELENA-SLEDAI: 4 (2–8) | – | – |

| Biomarker | Comparison | AUC (95%CI) | p-Value | Cut-Off | Sensitivity (95%CI) | Specificity (95%CI) | Youden’s J |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tot. cfDNA | SLE–HS | 0.75 (0.62–0.89) | 3.1 × 10−4 | 11.9 | 53 (40–67) | 100 (88–100) | 0.53 |

| Nuc. cfDNA | SLE–HS | 0.98 (0.94–1) | 4.8 × 10−7 | 2.66 | 90 (78–95) | 100 (88–100) | 0.9 |

| Mt. cfDNA | SLE–HS | 1 (1–1) | 1.4 × 10−7 | 115 | 100 (93–100) | 100 (88–100) | 1 |

| MPO | SLE–HS | 0.88 (0.8–0.96) | 1.3 × 10−6 | 2.04 | 98 (89–100) | 74 (56–86) | 0.72 |

| H3cit | SLE–HS | 0.85 (0.75–0.94) | 2.4 × 10−6 | 0.94 | 85 (73–93) | 78 (61–89) | 0.64 |

| IL-18 | SLE–HS | 0.91 (0.94–0.98) | 3 × 10−8 | 325 | 96 (86–99) | 83 (65–92) | 0.78 |

| Tot. cfDNA | AS–HS | 0.67 (0.58–0.77) | 9.1 × 10−4 | 9.9 | 48 (35–62) | 83 (66–93) | 0.31 |

| Nuc. cfDNA | AS–HS | 0.93 (0.87–0.99) | 5.9 × 10−8 | 1.6 | 90 (78–95) | 93 (78–98) | 0.83 |

| Mt. cfDNA | AS–HS | 0.86 (0.71–1) | 4.7 × 10−6 | 124 | 100 (93–100) | 82 (62–92) | 0.82 |

| IL-18 | AS–HS | 0.87 (0.79–0.95) | 2.5 × 10−10 | 274 | 88 (75–94) | 81 (63–91) | 0.68 |

| Nuc. cfDNA | RA–HS | 0.95 (0.89–1) | 1.1 × 10−7 | 1.53 | 90 (78–95) | 97 (83–100) | 0.86 |

| Mt. cfDNA | RA–HS | 0.94 (0.84–1) | 1.8 × 10−7 | 221 | 100 (93–100) | 94 (79–98) | 0.94 |

| MPO | RA–HS | 0.87 (0.8–0.94) | 1.6 × 10−9 | 11.4 | 63 (48–75) | 98 (84–100) | 0.6 |

| IL-18 | RA–HS | 0.93 (0.88–0.98) | 1.1 × 10−12 | 246 | 77 (64–87) | 98 (83–99) | 0.75 |

| Nuc. cfDNA | PsA–HS | 0.9 (0.79–1) | 2.8 × 10−5 | 1.54 | 90 (78–95) | 89 (73–96) | 0.78 |

| Mt. cfDNA | PsA–HS | 0.98 (0.95–1) | 5.3 × 10−7 | 68 | 95 (85–98) | 94 (80–99) | 0.89 |

| IL-18 | PsA–HS | 0.95 (0.9–1) | 5 × 10−11 | 277 | 88 (75–94) | 93 (78–98) | 0.81 |

| Mt. cfDNA | RA–AS | 0.72 (0.6–0.83) | 1.4 × 10−3 | 2903 | 87 (74–94) | 56 (38–72) | 0.43 |

| MPO | RA–AS | 0.89 (0.82–0.96) | 1.1 × 10−10 | 1.3 | 71 (57–82) | 100 (88–100) | 0.71 |

| H3Cit | SLE–RA | 0.78 (0.66–0.91) | 2 × 10−4 | 1.1 | 86 (74–93) | 68 (50–82) | 0.54 |

| MPO | SLE–PsA | 0.78 (0.64–0.92) | 1.4 × 10−3 | 2 | 97 (87–99) | 74 (56–86) | 0.7 |

| H3Cit | SLE–PsA | 0.86 (0.75–0.96) | 1.3 × 10−5 | 1 | 100 (93–100) | 74 (56–86) | 0.74 |

| MPO | SLE–AS | 0.91 (0.84–0.99) | 1.5 × 10−7 | 2.1 | 94 (83–98) | 74 (56–86) | 0.68 |

| H3Cit | SLE–AS | 0.87 (0.79–0.95) | 4.8 × 10−7 | 0.92 | 92 (81–97) | 78 (61–89) | 0.7 |

| Variable | Sum of Squares | df | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mitochondrial cfDNA | ||||

| C(Diagnosis) | 3.26 × 108 | 3 | 10.2 | 0.00008 |

| C(Treatment) | 2.33 × 107 | 1 | 2.2 | 0.14 |

| C(Diagnosis):C(Treatment) | 1.47 × 108 | 3 | 4.6 | 0.004 |

| H3cit | ||||

| C(Diagnosis) | 5.1 | 3 | 1.5 | 0.22 |

| C(Treatment) | 2.8 | 1 | 2.5 | 0.12 |

| C(Diagnosis):C(Treatment) | 14.0 | 3 | 4.2 | 0.0069 |

| MPO | ||||

| C(Diagnosis) | 44.3 | 3 | 3.0 | 0.054 |

| C(Treatment) | 47.4 | 1 | 9.5 | 0.0024 |

| C(Diagnosis):C(Treatment) | 238.4 | 3 | 16.0 | <0.0000001 |

| Gene | Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| RP: Human Ribonuclease P | Forward | 5′-AGATTTGGACCTGCGAGCG-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-GAGCGGCTGTCTCCACAAGT-3′ | |

| Probe | 5′-HEX-TTCTGACCTGAAGGCTCTGCGCG-BHQ-1-3′ | |

| MT-ND1: NADH dehydrogenase subunit 1 | Forward | 5′-GAGCGATGGTGAGAGCTAAGGT-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-CCCTAAAACCCGCCACATCT-3′ | |

| Probe | 5′-Cy3.5-CCATCACCCTCTACATCACCGCCC-BHQ2-3′ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Melamud, M.M.; Tolmacheva, A.S.; Sizikov, A.E.; Klyaus, N.A.; Zhuravlev, E.S.; Stepanov, G.A.; Nevinsky, G.A.; Buneva, V.N.; Ermakov, E.A. NETosis-Related Biomarkers in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, Rheumatoid Arthritis, Psoriatic Arthritis and Ankylosing Spondylitis: A Comparative Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12127. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412127

Melamud MM, Tolmacheva AS, Sizikov AE, Klyaus NA, Zhuravlev ES, Stepanov GA, Nevinsky GA, Buneva VN, Ermakov EA. NETosis-Related Biomarkers in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, Rheumatoid Arthritis, Psoriatic Arthritis and Ankylosing Spondylitis: A Comparative Study. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12127. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412127

Chicago/Turabian StyleMelamud, Mark M., Anna S. Tolmacheva, Alexey E. Sizikov, Nataliya A. Klyaus, Evgenii S. Zhuravlev, Grigory A. Stepanov, Georgy A. Nevinsky, Valentina N. Buneva, and Evgeny A. Ermakov. 2025. "NETosis-Related Biomarkers in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, Rheumatoid Arthritis, Psoriatic Arthritis and Ankylosing Spondylitis: A Comparative Study" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12127. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412127

APA StyleMelamud, M. M., Tolmacheva, A. S., Sizikov, A. E., Klyaus, N. A., Zhuravlev, E. S., Stepanov, G. A., Nevinsky, G. A., Buneva, V. N., & Ermakov, E. A. (2025). NETosis-Related Biomarkers in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, Rheumatoid Arthritis, Psoriatic Arthritis and Ankylosing Spondylitis: A Comparative Study. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12127. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412127