Consequently, optimizing genetic architecture is essential, with particular attention to minimizing basal expression by selecting an appropriate promoter activity upstream of the FourU sequence, thereby ensuring that gene expression remains tightly regulated and is activated only under the desired thermal conditions.

2.1. Effects of Basal Promoter Activity on Expression of Thermo-Regulated Genes

The effects of promoter activity on unintended recombination events were assessed by constructing a set of genetic circuits. Initially, a very simple circuit C1 was built in

E. coli to characterize the effect of promoter activity on FourU performance (see

Figure S1a). This circuit contains a high-copy-number plasmid that expresses GFP as a reporter downstream of a FourU sequence. A rhamnose-inducible promoter is positioned upstream of the FourU sequence. In these circuits, GFP expression is independent of Bxb1-mediated recombination, allowing for a straightforward evaluation of the promoter’s effect on the temperature-dependent expression of GFP (see

Supplementary Materials for genetic details).

The performance of the FourU sequence was initially analyzed under two extreme conditions: in the absence of rhamnose and with 2% rhamnose, the latter allowing maximal promoter activity.

Figure S1b,c present the GFP levels at various temperatures in circuit C1 under these conditions. At 0% rhamnose, circuit C1 demonstrated no evident temperature-dependent relationship with GFP levels (

Figure S1b), attributed to the minimal transcriptional activity of the PrhaB promoter. Conversely, at 2% rhamnose, GFP expression exhibited a clear temperature-dependent pattern (

Figure S1c). Notably, GFP expression was negligible at temperatures below 30 °C but increased at higher temperatures (see Materials and Methods for experimental details).

Based on these findings and consistent with prior results [

25,

26], a temperature of 20 °C can be considered the OFF state for FourU activity, while temperatures at or above 37 °C correspond to the ON state. Furthermore, these results underscore the importance of promoter activity in modulating the relationship between temperature and gene expression.

The sensitivity to temperature increased with enhanced promoter activity (

Figure S1d). Elevating rhamnose concentrations, which augment promoter activity [

27], led circuit C1 to exhibit a more pronounced response to temperature variations. This enhancement resulted in a greater differentiation in GFP levels between the OFF state at 20 °C and the ON state at 37 °C, culminating in a 5.4-fold increase in gene expression. However, heightened promoter activity was also correlated with increased basal protein expression in the OFF state (20 °C), with basal expression being 2.5-fold higher in the circuit at maximum promoter activity (>0.25% rhamnose) compared to minimal promoter activity (0% rhamnose).

2.2. Effects of Promoter Activity and Cellular Growth Phase on the Expression of Genes Modulated by Thermo-Regulated Recombinases

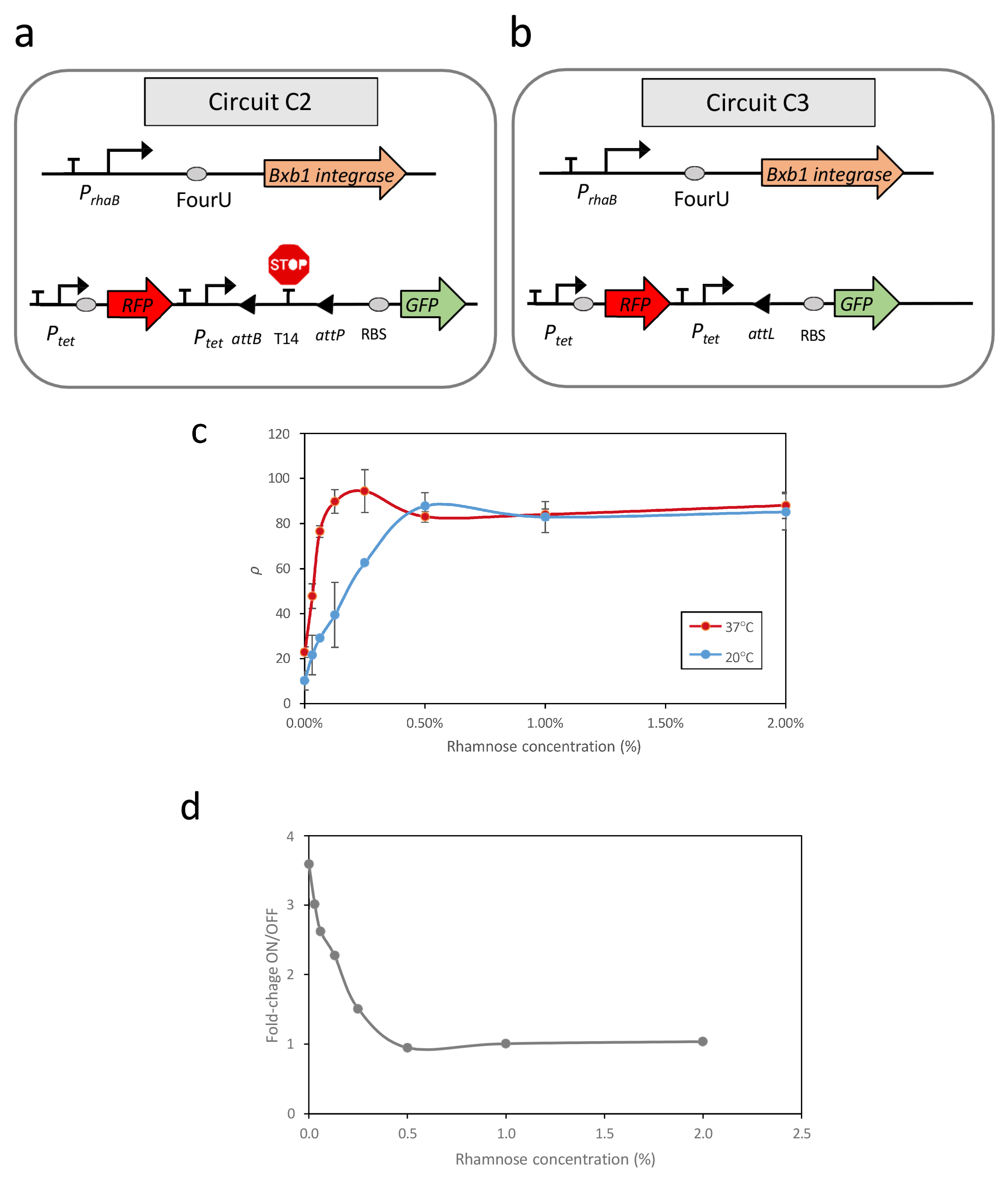

To assess the relationship between promoter activity and recombination events across various temperatures, two additional genetic circuits, C2 and C3, were constructed in

E. coli (see

Figure 1).

Circuit C2 (

Figure 1a) consisted of two modules housed within distinct plasmids. The first module, contained in a high-copy-number plasmid, functioned as a reporter circuit for excision events. This excision reporter circuit comprised a constitutive Ptet promoter positioned upstream of a double terminator sequence (T14) flanked by the attP and attB recognition sites. Downstream of this arrangement, a ribosomal binding site (RBS) sequence and a GFP gene were inserted as a reporter. The presence of T14 between the promoter and RBS prevented GFP expression. However, upon expression of the Bxb1 recombinase, the T14 sequence was excised, leading to GFP expression. Additionally, this plasmid constitutively expressed a Red Fluorescent Protein (RFP) under the control of the Ptet promoter, independent of temperature.

The second module, housed in a low-copy-number plasmid, was responsible for recombinase expression. Specifically, this module comprised the PrhaB promoter, followed by the FourU sequence and the Bxb1 coding region. Consequently, the transcription level of the Bxb1 coding region at each temperature can be modulated based on the concentration of rhamnose present in the medium.

Utilizing GFP as a reporter to assess recombination efficiency offers significant advantages, particularly by enabling straightforward in vivo monitoring of recombination events [

28,

29]. However, it is essential to consider that GFP fluorescence can be influenced by factors not directly related to the genetic architecture of the circuits. Specifically, GFP fluorescence levels are inherently sensitive to temperature variations [

30,

31] independently of regulatory mechanisms such as the FourU RNA thermometer. This intrinsic thermosensitivity must be considered when using GFP to quantify recombination efficiency, as temperature fluctuations may affect fluorescence intensity and potentially lead to inaccurate interpretations. As a result, directly comparing GFP levels measured at different temperatures to assess recombination efficiency is not reliable.

In addition to temperature, other factors may also influence GFP levels independently of recombination [

32,

33]. It is important to consider whether the excision of the plasmid fragment containing the T14 terminator sequence could alter the structure of the plasmid, potentially affecting its replication rate and, consequently, the levels of GFP detected.

To address these limitations, circuit C3 (

Figure 1b) was constructed. This circuit contains the same Bxb1 expression module as circuit C2; however, in the module responsible for reporting excision events, the terminator sequence T14 flanked by attB and attP sites was replaced with an attL site. The attL site is the product of a recombination event between attP and attB mediated by Bxb1. Therefore, circuit C3 represents a condition equivalent to 100% recombination of the attP-attB sites in circuit C2 and serves as a reference for maximum recombination efficiency.

First, to evaluate whether the plasmid population is affected by recombination events, RFP levels were measured at different temperatures in circuits C2 and C3. In both circuits, RFP expression is not directly regulated by Bxb1; therefore, significant changes in fluorescence levels as a function of temperature can be associated with alterations in plasmid copy number.

Figure S2 shows the RFP levels measured at 20 °C and 37 °C in both circuits.

Results show that although RFP fluorescence is temperature-dependent [

30], no statistically significant differences were observed between the fluorescence levels of circuits C2 and C3 at either temperature. Welch’s

t-test yielded

p-values of 0.259 at 20 °C and 0.329 at 37 °C. Given that circuit C3 does not undergo plasmid modification through recombination, these findings suggest that recombination events do not introduce significant changes in plasmid population or stability.

The recombination efficiency of the strain carrying circuit C2 at low (20 °C) and high (37 °C) temperatures across a range of rhamnose concentrations can be quantified according to the following equation (see

Section 4 for details):

Evaluation of

ρ revealed a strong correlation between promoter activity, dependent on rhamnose concentration, and the recombination efficiency of excision events (

Figure 1c). At 37 °C, with FourU in the ON state, elevated levels of promoter transcription corresponded to increases in GFP levels until saturation was achieved. A similar qualitative relationship, however, was observed at 20 °C, with higher levels of promoter induction corresponding to an increased number of excision events until saturation was achieved. Despite the system being expected to remain in the OFF state at 20 °C, with few recombination events, the rate of unwanted recombinations in this state increased rapidly as promoter activity increased. Thus, at rhamnose concentrations above 0.5%, there was no separation between OFF and ON states. These findings indicated that the design of genetic circuits based on recombination events in a temperature-dependent manner can result in unintended recombination events at lower temperatures, depending on the promoter activity upstream of the RNAT sequence. Evaluation of the relationship of fold-changes between the OFF and ON states, corresponding to 20 °C and 37 °C, respectively, and the level of promoter induction showed that the maximum difference between ON and OFF states occurred at minimal promoter activity, specifically 0% rhamnose (

Figure 1d). This result was unexpected because, in circuit C1, there was no clear response to temperature in the OFF state (

Figure S1b).

For illustrative purposes,

Figure 2 shows representative data of the recombination efficiency (

ρ) in circuit C2 across a wide temperature range under three levels of promoter activity: 0% rhamnose (

Figure 2a), 0.13% rhamnose (

Figure 2b), and 2% rhamnose (

Figure 2c). The results indicate that thermal sensitivity is strongly influenced by promoter activity. At low promoter activity (0% rhamnose), recombination is minimal below 30 °C and reaches a maximum efficiency of

ρ = 27% at higher temperatures. Although this configuration provides the most favorable performance in terms of clear separation between low and high-temperature responses, along with minimal protein expression in the OFF state, the maximum recombination efficiency remains relatively low.

In contrast, at intermediate promoter activity (0.13% rhamnose), a significant increase in recombination events is observed, with a maximum efficiency of ρ = 90%. However, increased promoter activity also leads to substantial recombination at lower temperatures, thereby reducing the separation between the OFF and ON states. When promoter activity is very high (2% rhamnose), the circuit exhibits a complete loss of temperature sensitivity.

It is important to highlight that, although both circuit C1 and the PrhaB–FourU–Bxb1 module in circuit C2 respond similarly to PrhaB promoter activity, consistent with previous results [

34], their behavior diverges in terms of dynamic response. In circuit C2, increasing PrhaB activity reduces the OFF–ON separation of the circuit, as shown in

Figure 1d, which translates into a loss of sensitivity of circuit C2’s response to temperature changes when PrhaB promoter activity is elevated. Consequently, the activity of the promoter upstream of the FourU–Bxb1 module appears to be a crucial parameter determining the circuit’s thermal response.

However, although the greatest separation between OFF and ON states is achieved in circuit C2 with 0% rhamnose, the maximum recombination efficiency

ρ under these conditions reaches only 27%. Although the reason for not achieving 100% of the possible recombinations is not clear, a relationship between growth phase and the increase in GFP levels due to recombination events was observed. The entry of bacterial cultures into the stationary phase affects the expression of genes modulated by recombination events and the maintenance of GFP levels (

Figure S3). This finding is consistent with previous results indicating that entering the stationary phase can be accompanied by significant reductions in plasmatic protein synthesis [

34,

35,

36], affecting both Bxb1 and GFP.

To determine if the growth phase could be a limiting factor in recombination events,

E. coli containing circuit C2 was cultured in medium containing 0% rhamnose at 20 °C and 37 °C. Once each culture reached the stationary phase, an aliquot was inoculated into fresh medium; this process was repeated for 3 days. The same procedure was concurrently applied to circuit C3. The recombination efficiency

ρ was calculated each time the culture entered the stationary phase (

Figure 2d). At 20 °C, corresponding to the OFF state, there was a slight increase in recombination rate, possibly due to the low basal expression of Bxb1. At 37 °C, however, recombination rates of 23% were achieved after the first day, similar to the rates shown in

Figure 2a. However, as the growth was repeated on successive days, recombination levels reached 73%. These results suggest that recombination events accumulate each time the culture enters the growth phase until it again reaches the stationary phase. This outcome suggests that the duration of the exponential growth phase in a culture can be a limiting factor for inducing recombination events in response to temperature changes.

The results presented above indicate that, in liquid cultures, several key parameters govern the precise control of recombination events in temperature-inducible genetic circuits. Specifically, promoter activity, the duration of temperature pulses to which the circuit is exposed, and the length of the exponential growth phase are three critical factors that must be carefully considered when implementing genetic circuits designed to induce irreversible DNA modifications in response to thermal cues.

Moreover, although genetic architectures based on low promoter activity (e.g., PRhaB at 0% rhamnose) only achieve partial recombination across available sites, their lack of basal activity at low temperatures and greater dynamic range between OFF and ON states make them well-suited for constructing complex genetic devices requiring clear binary behavior.

2.4. Spatial Control of Temperature-Dependent Recombination Events

The use of paper-based surfaces to develop bacteria-based biosensors enables the creation of low-cost, portable, and disposable devices, ideal for applications such as environmental monitoring [

37], contaminant surveillance [

38], or point-of-care diagnostics [

39], among others. Moreover, these architectures benefit from division of labor among different cell types [

40], thereby reducing the genetic complexity required per cell. The integration of genetically encoded, temperature-controlled systems represents a promising advance in this field. Specifically, an important advantage of temperature- inducible recombinases is their capacity to drive spatially resolved recombination, enabling the generation of temperature-dependent spatial patterns, which could introduce new functionalities to these types of devices.

To investigate this, the effect of temperature on surface-based recombination events was evaluated. Building on prior results, spatial control of temperature-dependent recombination was assessed using circuit C2 in the absence of rhamnose (0%), with circuit C3 serving as a reference for quantifying the recombination efficiency.

Initially, recombination efficiency was quantified on two paper surfaces: one uniformly inoculated with an

E. coli strain harboring circuit C2, and the other with circuit C3. Both were incubated at 20 °C. Subsequently, the relationship between temperature and GFP on a surface culture was assessed by exposing these surfaces to different temperatures. GFP levels following exposure to different temperatures were measured by scanning the paper surface containing the cellular circuits with an HTX BioTech Synergy plate reader. Since direct measurement of OD is not feasible in surface-based paper cultures, cell concentration was estimated based on the levels of constitutively expressed RFP from circuits C2 and C3. In this way, surface recombination efficiency

ρS can be calculated as follows (see Materials and Methods for details):

Because circuit C2 exhibits a greater separation between OFF and ON state fluorescence levels at 0% rhamnose, all surface-based experiments were conducted under this condition.

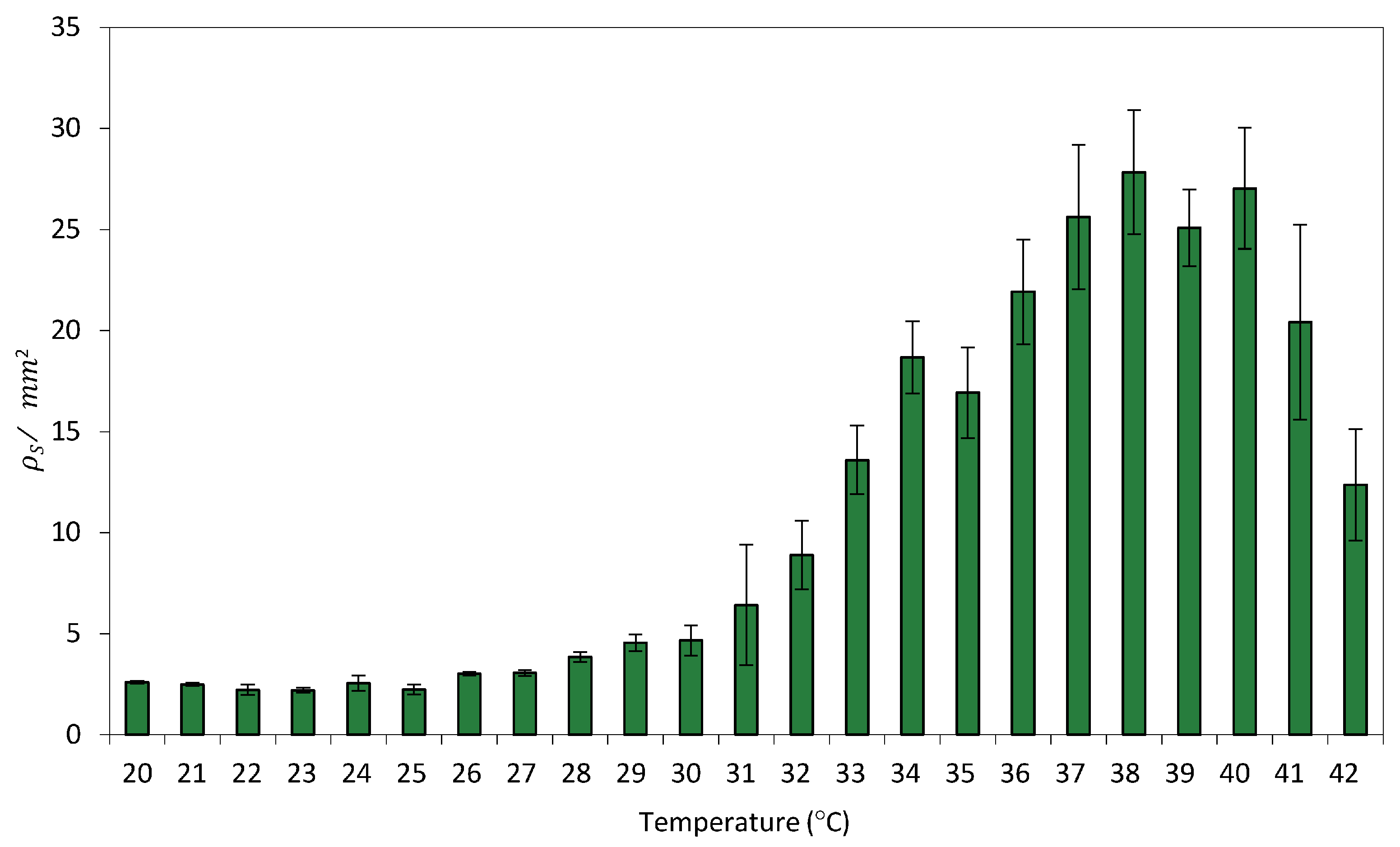

Figure 4 shows the relationship between the average

ρS per unit area, i.e.,

ρS/mm

2 and temperature.

Despite the fact that bacterial growth on solid surfaces presents several limitations compared to agitated liquid cultures [

41], limitations that can influence cellular physiology and gene expression, particularly in synthetic circuits sensitive to environmental cues, a comparison of this transfer function with its equivalent in liquid culture (

Figure 2) revealed a strong similarity in recombination efficiency between surface- and liquid-grown cells. This suggests that spatial confinement does not significantly impact the efficiency of recombination events.

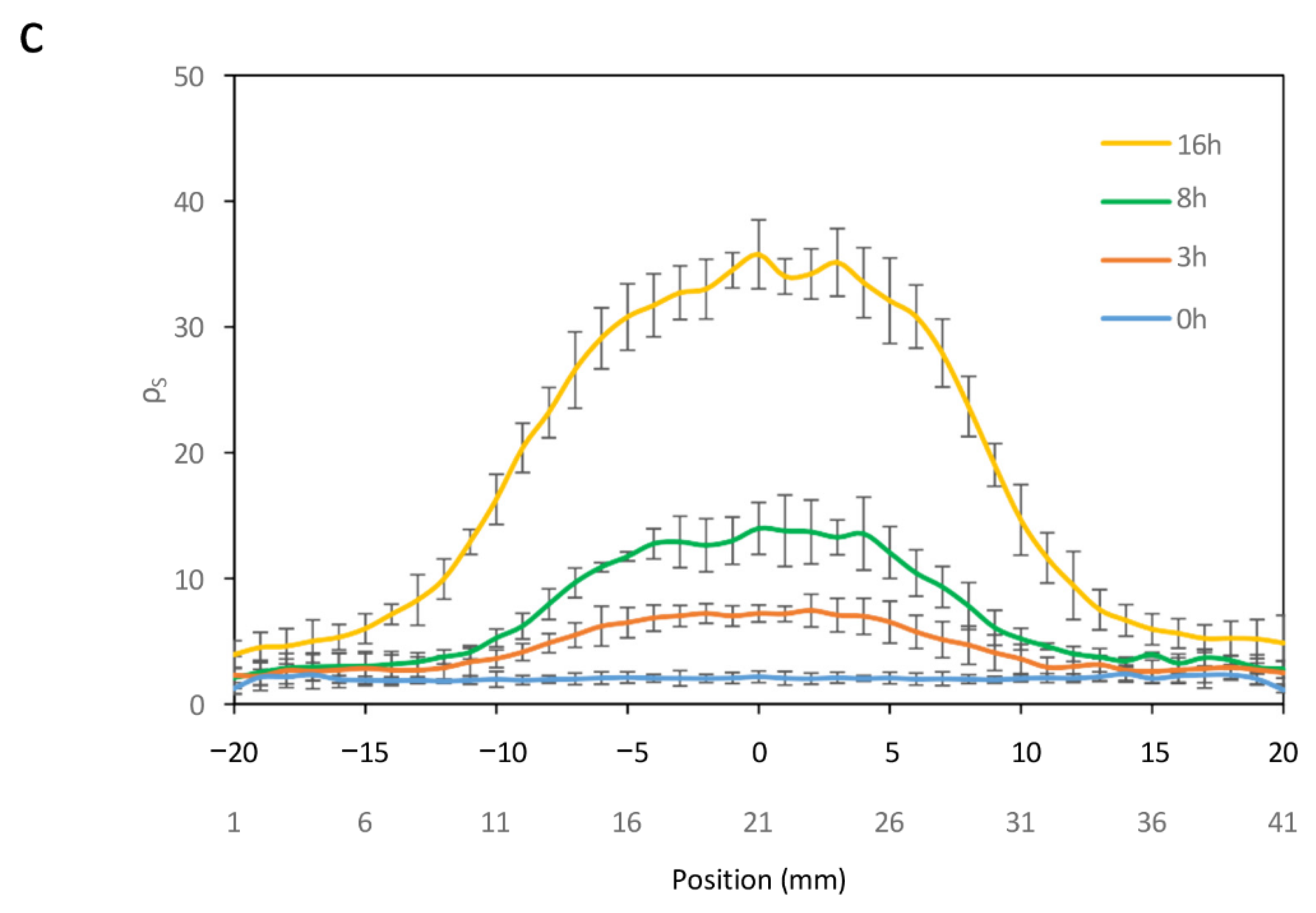

To investigate the generation of spatial patterns through temperature-dependent expression of Bxb1,

E. coli cells harboring circuits C2 and C3 were cultivated on a paper surface at 20 °C. A 1 mm diameter hot finger maintained at 37 °C was used to create discrete thermal spots at defined locations (see Materials and Methods for experimental details for experimental setup).

Figure 5a shows an image of the experimental setup. The surface recombination efficiency

ρS was quantified at each position. Owing to the radial symmetry of heat diffusion, a transverse section of the resulting spatial temperature profile was used to characterize the formation of recombination-induced spots around the hot-finger contact point.

Figure 5b shows the spatial distribution resulting from the thermal gradient generated on the paper surface after hot-finger application at position (0, 0). Cells were exposed to localized temperatures of 23 °C, 32 °C, 37 °C, and 42 °C for 16 h. Localized thermal stimulation triggered recombination in cells that experienced temperatures above a threshold value. As the distance from the application site increases, the temperature decreases accordingly, leading to a reduction in recombination efficiency. Higher temperatures were associated with increased recombination levels, accompanied by a slight rise in basal activity.

Finally, the generation of spatially localized spots in response to temperature pulses of varying duration was examined. Circuits C2 and C3 were cultivated on a paper surface at 20 °C, followed by the application of a 42 °C hot finger for different time intervals.

Figure 5c shows the resulting spot profiles, expressed as

ρS, as a function of pulse duration. Recombination efficiency increased with longer exposure times, although basal recombination levels also exhibited a slight rise with extended pulse durations.

These results demonstrate that spatial gene expression patterns can be generated through localized thermal activation and that such patterns can be precisely tuned by modulating both the applied temperature and the duration of exposure at each specific location on the surface.

Together, these findings demonstrate that minimal genetic circuits regulated by the expression of a temperature-responsive recombinase provide multiple layers of control, including promoter strength, temperature, and pulse duration, that enable precise modulation of gene expression. This framework is applicable to both liquid cultures, where regulation affects the entire population, and to surface-based systems, where localized inputs enable spatially differentiated control. These features make such synthetic devices promising tools for a wide range of applications in both homogeneous and spatially structured environments.

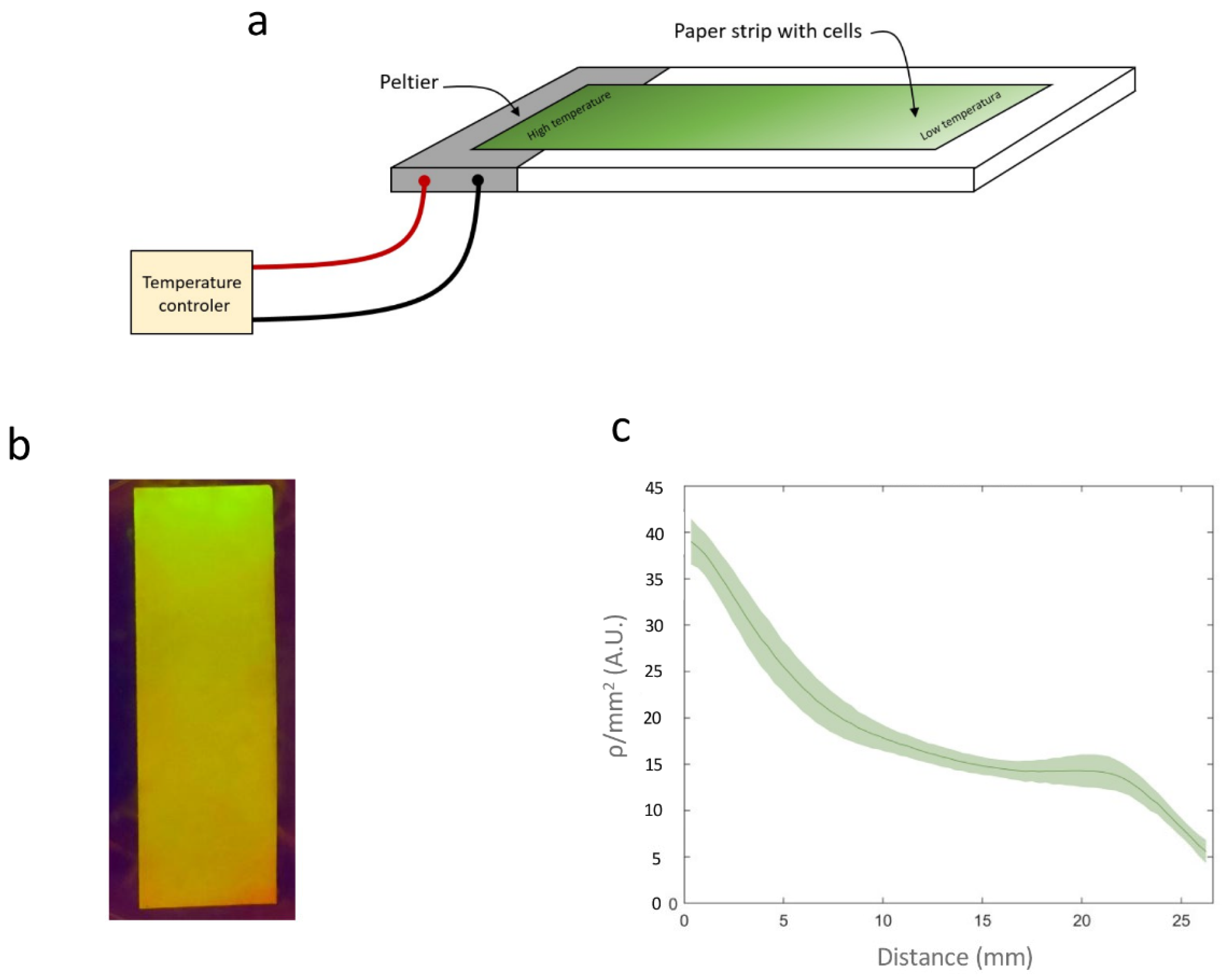

2.5. Thermal Configuration of Spatial Patterns

One potential application for cellular systems expressing a GOI, such as GFP, in response to temperature is the formation of spatial patterns defined by temperature differences between different points on a surface. Because this type of application requires good resolution between points on the surface at different temperatures, the cellular system should not generate a basal signal that could obscure the pattern being configured. This requirement is met by a genetic architecture based on thermo-regulated recombinases, along with a reduction in the duration of maintenance of the temperature pattern to obtain the corresponding cellular response.

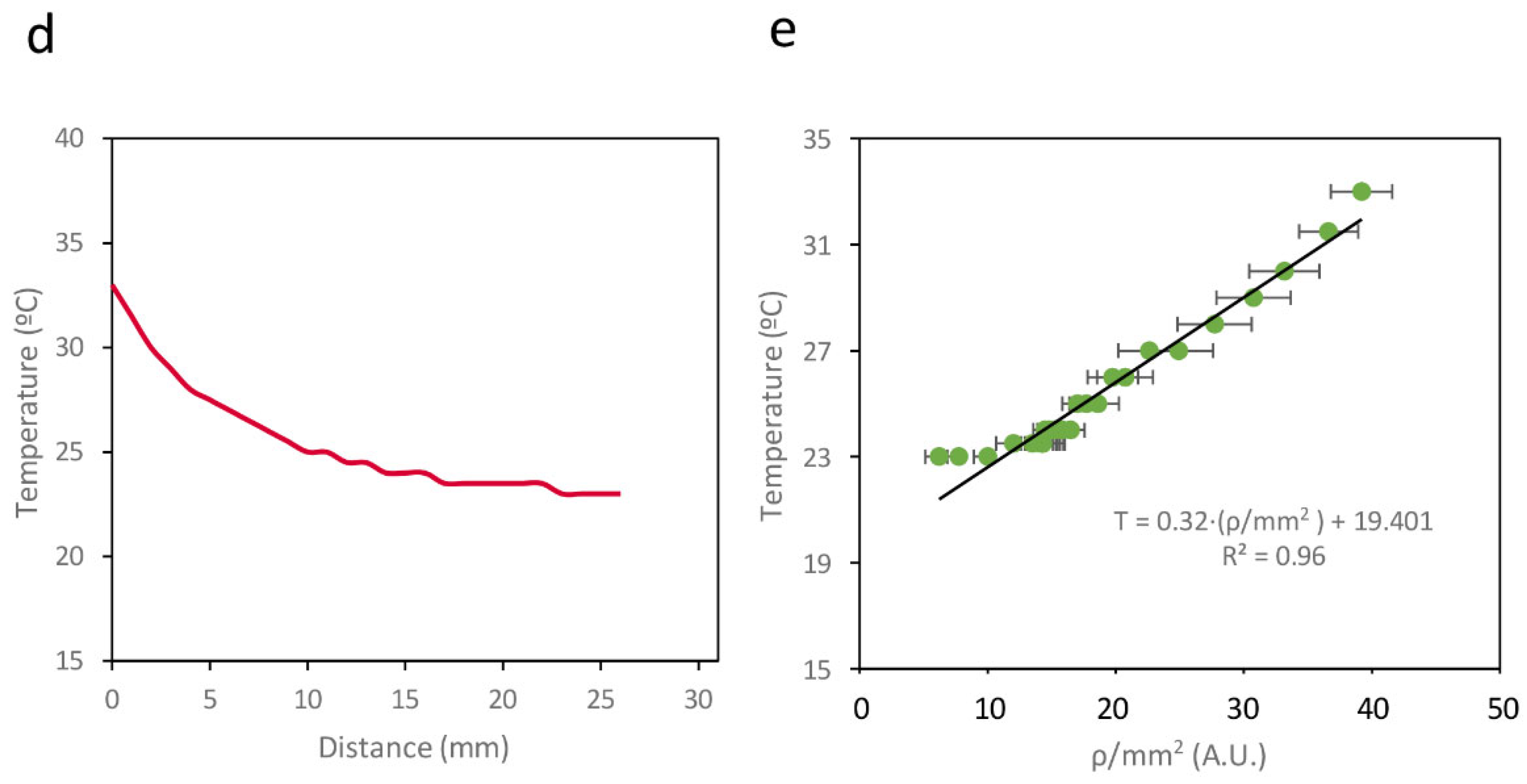

To investigate the formation of spatial patterns, E. coli harboring Circuit C2 was cultured at 20 °C and uniformly spread onto a 27 mm long strip of paper in the absence of rhamnose.

A similar setup was prepared for Circuit C3. A temperature gradient was generated by applying two different temperatures (42 °C and 23 °C) at two points 30 mm apart on a Petri dish containing Lysogeny Broth (LB) agar. The paper strips were placed between these two points, 4 mm from the 42 °C point. This configuration was maintained for 3 h, after which the paper strips were incubated at 20 °C for 18 h.

Figure 6a shows an image of the paper strip containing Circuit C2 under a transilluminator, where a clear gradient in fluorescence intensity can be observed. The average recombination efficiency (

ρ/mm

2) along the strip was measured using a Synergy MX microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA).

Figure 6b shows how

ρ/mm

2 varies with the distance from the high-temperature point. Direct measurement of the temperature gradient on the surface using a thermocouple connected to an Amprobe 38XRA multimeter (Amprobe, Everett, WA, USA) (

Figure 6c) revealed a linear correlation between the measured temperature and

ρ/mm

2 on the paper strip, with R

2 = 0.96 (

Figure 6d). This linear relationship enables a direct conversion between

ρ/mm

2 values and temperature, demonstrating that this device can be used to record temperature gradients on paper surfaces.

2.6. Temperature-Controlled Cellular Release Systems

One potential application of these circuits, based on the temperature dependence of recombinase-mediated gene expression, is the creation of temperature-controlled cellular release systems.

Specific microorganisms can be genetically engineered to express enzymes or other compounds of interest [

42]. Once these compounds are produced, however, it may be necessary to release them from the intracellular environment, including through the expression of lytic genes under specific conditions [

43,

44]. Inducing the expression of these lytic genes can result in disruption of the cell walls, allowing the compounds of interest to be released into the surrounding medium, where they can be harvested [

45].

The expression of lytic genes can be induced by altering temperature, a more cost-effective option than chemical inducers. Moreover, temperature changes can be uniformly applied throughout the entirety of a cellular population. These systems require that cellular lysis occurs above a certain temperature, with basal expression being close to 0 at low temperatures. An architecture based on low-activity promoters, such as Circuit C2, is suitable for these applications, as there are no indications of significant basal activity at low temperature (20 °C), preventing unintended cell lysis. By contrast, protein expression was at a sufficiently high temperature (37 °C), resulting in the efficient induction of cell lysis.

This hypothesis was tested by constructing two new

E. coli strains. Specifically, Circuit C7 (

Figure S4a) and Circuit C8 (

Figure S4b) were designed as direct derivatives of Circuits C1 and C2, respectively, both combining the GFP sequence with a lytic gene from bacteriophage ϕX174 in a bicistronic construct [

46,

47]. These new cell strains were cultured in liquid medium at 20 °C until reaching an OD

660 of 0.9. Subsequently, the temperature of both cultures was raised to 37 °C for 3 h. Finally, the cultures were maintained at 20 °C for several days. All experiments were conducted at 0% rhamnose to ensure minimal activity of the PrhaB promoter, thus preventing unintended recombination at 20 °C and avoiding cell lysis at this low temperature. Use of higher rhamnose concentrations led to recombination at 20 °C, resulting in undesired expression of the lysis gene, which compromises cell growth at low temperature.

This study hypothesized that

E. coli bearing Circuit C7 would express very low levels of the lytic protein, in agreement with the results in

Figure S1b. By contrast, the expression of Bxb1 by

E. coli bearing Circuit C8 was expected to enable significant expression of the lytic gene, consistent with the results in

Figure 2a. Expression of the lytic gene would therefore result in cell wall rupture and the release of intracellular content into the external environment. Consequently, cell lysis should result in increased levels of extracellular GFP and decreased levels of intracellular GFP. The efficiency of temperature-induced cellular lysis could therefore be monitored by measuring extracellular GFP levels (see Materials and Methods for experimental details).

Changes in extracellular and intracellular GFP levels were therefore monitored in

E. coli bearing Circuits C7 and C8 (

Figure 7). GFP levels in the extracellular medium of Circuit C7-bearing bacteria at 37 °C did not differ significantly from the levels observed at 20 °C (

Figure 7a,b). Similarly, intracellular GFP levels were similar at both temperatures. Taken together, these results indicate that the lytic gene was not significantly induced when it is located directly downstream of a low-activity promoter and the FourU sequence. These results were consistent with those observed in

Figure S1b.

Increasing the temperature of

E. coli bearing Circuit C8 from 20 °C to 37 °C significantly enhanced the expression of the lytic gene over time, resulting in efficient cell wall rupture and the release of intracellular contents into the external medium. The higher extracellular GFP levels at 37 °C than at 20 °C indicated that cellular lysis was greater at the higher temperature (

Figure 7c). Evaluation of intracellular GFP levels showed that, during an initial phase, these levels increased over time at 37 °C, indicating that Bxb1 levels increased as the temperature increased from 20 °C to 37 °C (

Figure 7d). Bxb1 expression, however, also increased the expression of the lytic gene, resulting in the release of the intracellular contents, including GFP, into the external medium. Thus, intracellular GFP levels decreased as extracellular GFP levels increased.

These results demonstrate that a system based on thermo-regulated recombinases allows for efficient induction of cellular lysis in response to a temperature increase, ensuring that basal expression at low temperatures, i.e., 20 °C, is very low and thus does not compromise cell integrity.