The Effect of clpP Gene Disruption on Cell Morphology, Growth, and the Ability to Synthesize Cellulose of Komagataeibacter xylinus E25

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Disruption and Complementation of clpP Gene in K. xylinus E25

2.2. Morphology of Colonies and Cells of E25 Strain and Its Mutants

2.3. The Profile of Growth and BNC Production by Native and Mutant Strains

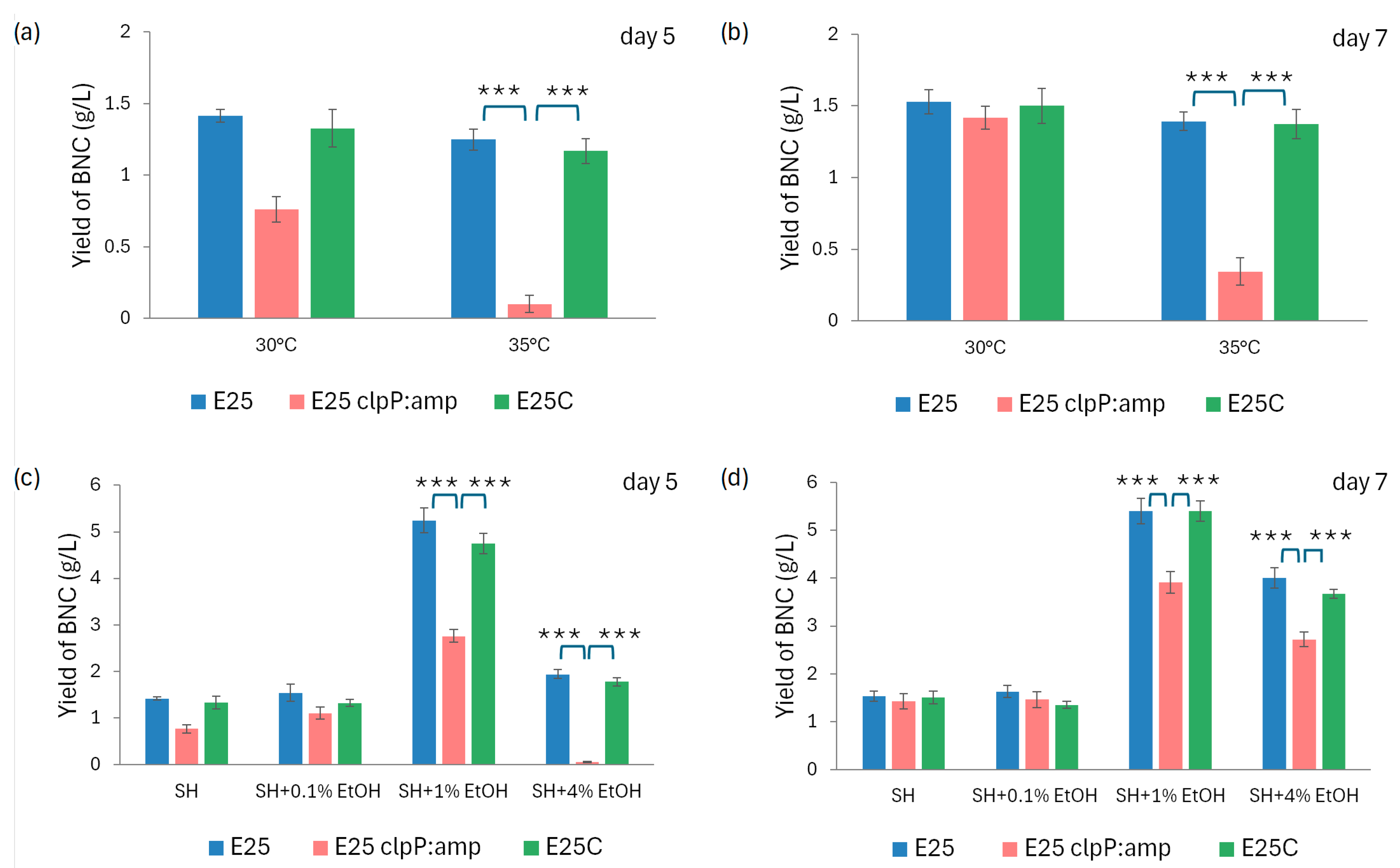

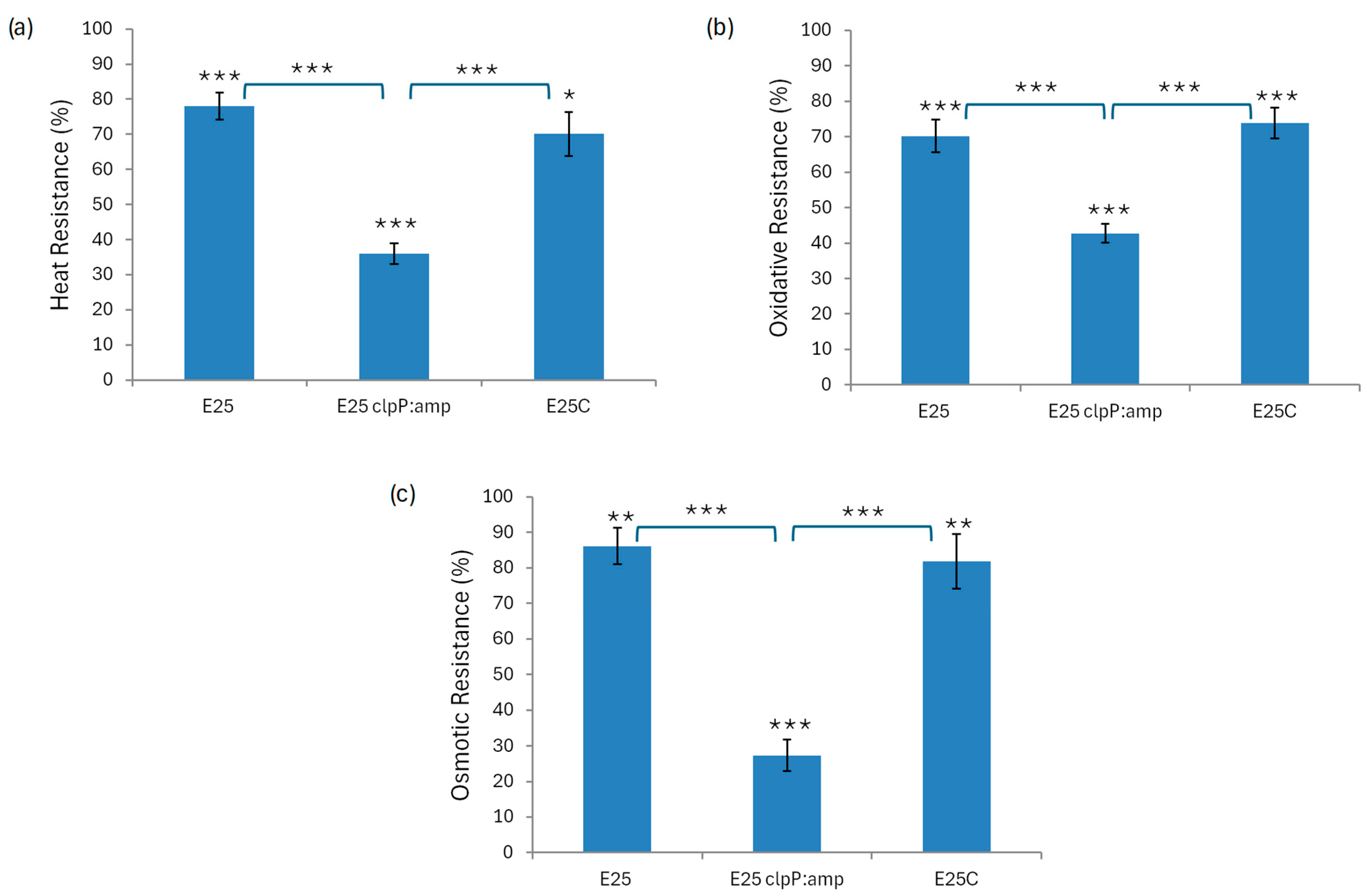

2.4. Stress Tolerance

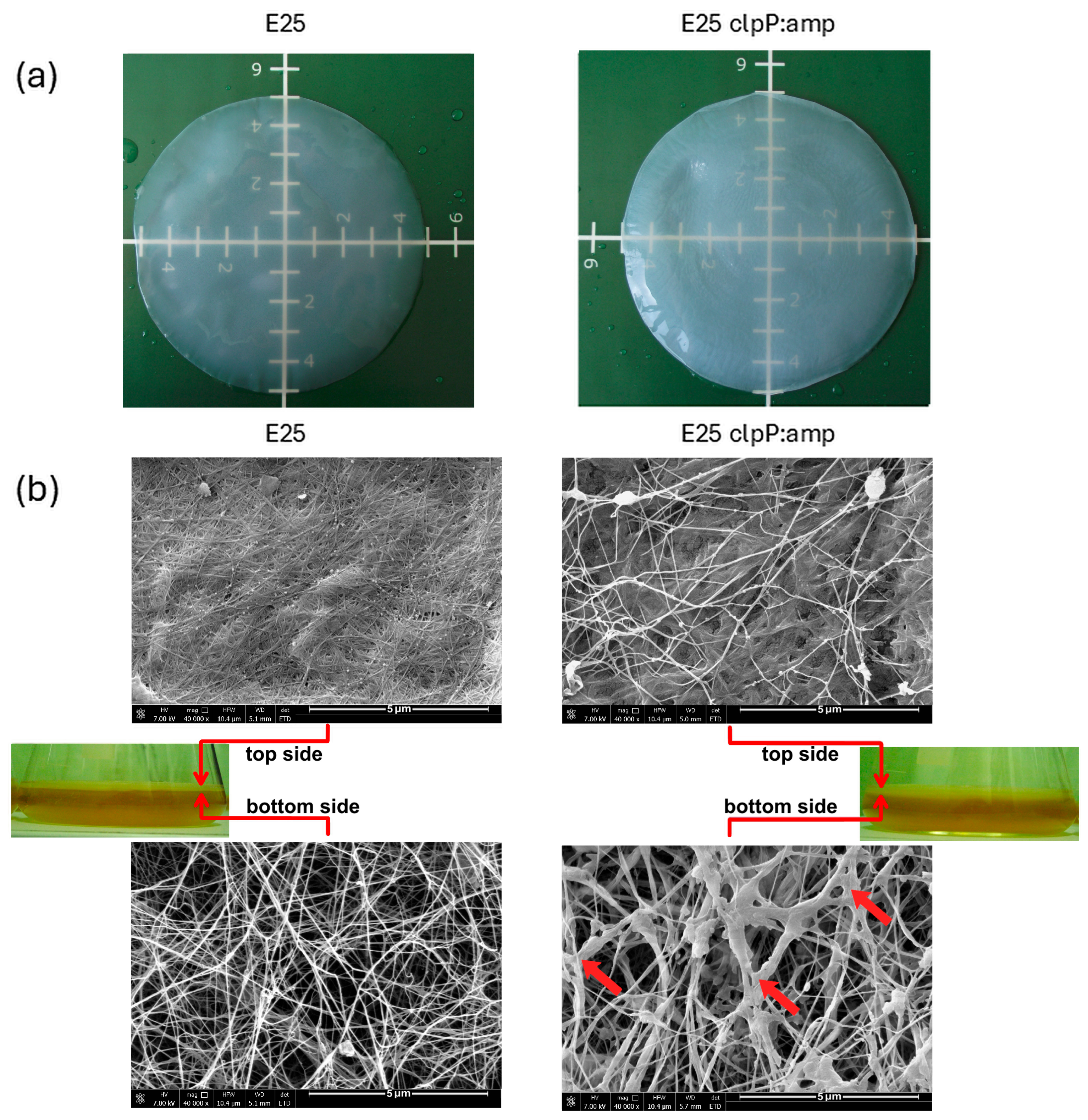

2.5. Morphology of Cellulose Membranes

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals

4.2. Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, and Culture Conditions

4.3. BNC Purification

4.4. Construction of Mutants with Disrupted clpP Gene and Its Complementary Strain

4.5. Microscopic Observations of Bacterial Colony Morphology

4.6. Determination of the Number of Cells Forming a Single Bacterial Colony

4.7. Microscopic Observations of Bacterial Cells

4.8. Bacterial Growth Assay

- -

- Spectrophotometrically—bacterial growth was measured using a 6300 VIS/6305 UV–VIS spectrophotometer (Jenway, Stone, Staffordshire, UK) at a wavelength of 600 nm against the control sample (HS medium).

- -

- By the Dip-plating method—100 µL of the diluted 101 to 107 suspension was spread onto Petri dishes containing HS medium with 2% agar. The plates were then incubated for 5 days at 30 °C. After incubation, the number of colonies grown on the plates was counted, and the number of bacterial cells per ml of culture was calculated based on the dilution. The final result was presented in CFU/mL.

4.9. Glucose Concentration Determination

4.10. Effect of Temperature and Ethanol on Cell Growth and Cellulose Biosynthesis

4.11. Determination of Bacterial Cell Resistance to Stress

4.12. BNC Yield Determination

4.13. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) of BNC

4.14. EPS Preparation

4.15. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BNC | Bacterial Nanocellulose |

| HS | Hestrin and Schramm medium |

| EPS | Exopolysaccharide |

| HE-EPS | Hard-to-extract exopolysaccharide |

References

- Sunagawa, N.; Tajima, K.; Hosoda, M.; Kawano, S.; Kose, R.; Satoh, Y.; Yao, M.; Dairi, T. Cellulose Production by Enterobacter sp. CJF-002 and Identification of Genes for Cellulose Biosynthesis. Cellulose 2012, 19, 1989–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, J.M.; Steinacher, M.; Kan, A.; Ritter, M.; Leutert, M.; Bienz, S.; Häberlin, D.; Kumar, N.; Studart, A.R. Genetic Impacts on the Structure and Mechanics of Cellulose Made by Bacteria. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e05075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaczmarek, M.; Jędrzejczak-Krzepkowska, M.; Ludwicka, K. Comparative Analysis of Bacterial Cellulose Membranes Synthesized by Chosen Komagataeibacter Strains and Their Application Potential. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vegas, C.; Mateo, E.; González, Á.; Jara, C.; Guillamón, J.M.; Poblet, M.; Torija, M.J.; Mas, A. Population Dynamics of Acetic Acid Bacteria During Traditional Wine Vinegar Production. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2010, 138, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, S. Biosynthesis and Assemblage of Extracellular Cellulose by Bacteria. In Handbook of Environmental Materials Management; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, P.; Mayer, R.; Benziman, M. Cellulose Biosynthesis and Function in Bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 1991, 55, 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott Williams, W.S.; Cannon, R.E. Alternative Environmental Roles for Cellulose Produced by Acetobacter xylinum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1989, 55, 2448–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trček, J.; Dogsa, I.; Accetto, T.; Stopar, D. Acetan and Acetan-Like Polysaccharides: Genetics, Biosynthesis, Structure, and Viscoelasticity. Polymers 2021, 13, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Catchmark, J.M. Characterization of Water-Soluble Exopolysaccharides from Gluconacetobacter xylinus and Their Impacts on Bacterial Cellulose Crystallization and Ribbon Assembly. Cellulose 2014, 21, 3965–3978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Catchmark, J.M. Characterization of Cellulose and Other Exopolysaccharides Produced from Gluconacetobacter Strains. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 115, 663–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwicka, K.; Kolodziejczyk, M.; Gendaszewska-Darmach, E.; Chrzanowski, M.; Jedrzejczak-Krzepkowska, M.; Rytczak, P.; Bielecki, S. Stable Composite of Bacterial Nanocellulose and Perforated Polypropylene Mesh for Biomedical Applications. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2019, 107, 978–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska-Ludwicka, K.; Cala, J.; Grobelski, B.; Sygut, D.; Jesionek-Kupnicka, D.; Kolodziejczyk, M.; Bielecki, S.; Pasieka, Z. Modified Bacterial Cellulose Tubes for Regeneration of Damaged Peripheral Nerves. Arch. Med. Sci. 2013, 9, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Pei, W.; Fu, C.; Ma, M.; Huang, C. The State-of-the-Art Application of Functional Bacterial Cellulose-Based Materials in Biomedical Fields. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 300, 120252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludwicka, K.; Kaczmarek, M.; Białkowska, A. Bacterial Nanocellulose—A Biobased Polymer for Active and Intelligent Food Packaging Applications: Recent Advances and Developments. Polymers 2020, 12, 2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lasagni, F.; Cassanelli, S.; Gullo, M. How Carbon Sources Drive Cellulose Synthesis in Two Komagataeibacter xylinus Strains. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anguluri, K.; La China, S.; Brugnoli, M.; Cassanelli, S.; Gullo, M. Better under Stress: Improving Bacterial Cellulose Production by Komagataeibacter xylinus K2G30 (UMCC 2756) Using Adaptive Laboratory Evolution. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 994097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cielecka, I.; Ryngajłło, M.; Bielecki, S. BNC Biosynthesis with Increased Productivity in a Newly Designed Surface Air-Flow Bioreactor. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryngajłło, M.; Jędrzejczak-Krzepkowska, M.; Kubiak, K.; Ludwicka, K.; Bielecki, S. Towards Control of Cellulose Biosynthesis by Komagataeibacter Using Systems-Level and Strain Engineering Strategies: Current Progress and Perspectives. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 6565–6585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogino, H.; Azuma, Y.; Hosoyama, A.; Nakazawa, H.; Matsutani, M.; Hasegawa, A.; Otsuyama, K.-I.; Matsushita, K.; Fujita, N.; Shirai, M. Complete Genome Sequence of NBRC 3288, a Unique Cellulose-Nonproducing Strain of Gluconacetobacter xylinus Isolated from Vinegar. J. Bacteriol. 2011, 193, 6997–6998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taweecheep, P.; Naloka, K.; Matsutani, M.; Yakushi, T.; Matsushita, K.; Theeragool, G. In Vitro Thermal and Ethanol Adaptations to Improve Vinegar Fermentation at High Temperature of Komagataeibacter oboediens MSKU 3. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2019, 189, 144–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taweecheep, P.; Naloka, K.; Matsutani, M.; Yakushi, T.; Matsushita, K.; Theeragool, G. Superfine Bacterial Nanocellulose Produced by Reverse Mutations in the BcsC Gene during Adaptive Breeding of Komagataeibacter oboediens. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 226, 115243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coucheron, D.H. An Acetobacter xylinum Insertion Sequence Element Associated with Inactivation of Cellulose Production. J. Bacteriol. 1991, 173, 5723–5731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jedrzejczak-Krzepkowska, M.; Kubiak, K.; Ludwicka, K.; Bielecki, S. Bacterial NanoCellulose Synthesis, Recent Findings. In Bacterial Nanocellulose: From Biotechnology to Bio-Economy; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 19–46. ISBN 9780444634665. [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento, F.X.; Torres, C.A.V.; Freitas, F.; Reis, M.A.M.; Crespo, M.T.B. Functional and Genomic Characterization of Komagataeibacter uvaceti FXV3, a Multiple Stress Resistant Bacterium Producing Increased Levels of Cellulose. Biotechnol. Rep. 2021, 30, e00606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; Nagachar, N.; Fang, L.; Luan, X.; Catchmark, J.M.; Tien, M.; Kao, T.H. Isolation and Characterization of Two Cellulose Morphology Mutants of Gluconacetobacter hansenii ATCC23769 Producing Cellulose with Lower Crystallinity. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0119504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Wu, Y.; Lin, Z.; Wang, G.; Jiang, S.; Sun, X.; Tu, H.; Yu, Z.; Qu, D. ClpP Participates in Stress Tolerance, Biofilm Formation, Antimicrobial Tolerance, and Virulence of Enterococcus Faecalis. BMC Microbiol. 2020, 20, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Cinos, C.; Goossens, K.; Salado, I.G.; Van Der Veken, P.; De Winter, H.; Augustyns, K. ClpP Protease, a Promising Antimicrobial Target. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.H.; Zhang, J.Q.; Song, X.Y.; Ma, X.B.; Zhang, S.Y. Contribution of ClpP to Stress Tolerance and Virulence Properties of Streptococcus Mutans. J. Basic. Microbiol. 2014, 54, 1222–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; Zhang, Y.; Li, G.; Zhou, L.; Liu, S.; Wang, C. Correction: The ClpP Protease Is Required for the Stress Tolerance and Biofilm Formation in Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, 53600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Wang, X.; Cao, Q.; Feng, F.; Xu, X.; Cai, X. ClpP Participates in Stress Tolerance and Negatively Regulates Biofilm Formation in Haemophilus parasuis. Vet. Microbiol. 2016, 182, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Wang, H.; Zhang, R.; Li, H. The Regulation of Porphyromonas gingivalis Biofilm Formation by ClpP. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 509, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Li, M.; Dong, D.; Wang, J.; Ren, J.; Otto, M.; Gao, Q. Role of ClpP in Biofilm Formation and Virulence of Staphylococcus Epidermidis. Microbes Infect. 2007, 9, 1376–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrand, A.J.; Reniere, M.L.; Ingmer, H.; Frees, D.; Skaar, E.P. Regulation of Host Hemoglobin Binding by the Staphylococcus aureus Clp Proteolytic System. J. Bacteriol. 2013, 195, 5041–5050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirsch, V.C.; Fetzer, C.; Sieber, S.A. Global Inventory of ClpP- and ClpX-Regulated Proteins in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Proteome Res. 2020, 20, 867–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breidenstein, E.B.M.; Hancock, R.E.W. Armand-Frappier Outstanding Student Award—Role of ATPdependent Proteases in Antibiotic Resistance and Virulence. Can. J. Microbiol. 2013, 59, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenal, U.; Fuchs, T. An Essential Protease Involved in Bacterial Cell-Cycle Control. EMBO J. 1998, 17, 5658–5669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, G.M.; Olsen, J.E.; Aabo, S.; Barrow, P.; Rychlik, I.; Thomsen, L.E. ClpP Deletion Causes Attenuation of Salmonella Typhimurium Virulence through Mis-Regulation of RpoS and Indirect Control of CsrA and the SPI Genes. Microbiology 2013, 159, 1497–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, G.A.; Kolter, R. Initiation of Biofilm Formation in Pseudomonas Fluorescens WCS365 Proceeds via Multiple, Convergent Signalling Pathways: A Genetic Analysis. Mol. Microbiol. 1998, 28, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemos, J.A.C.; Burne, R.A. Regulation and Physiological Significance of ClpC and ClpP in Streptococcus Mutans. J. Bacteriol. 2002, 184, 6357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frees, D.; Chastanet, A.; Qazi, S.; Sørensen, K.; Hill, P.; Msadek, T.; Ingmer, H. Clp ATPases Are Required for Stress Tolerance, Intracellular Replication and Biofilm Formation in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 2004, 54, 1445–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, A.; Agerer, F.; Hauck, C.R.; Herrmann, M.; Ullrich, J.; Hacker, J.; Ohlsen, K. Global Regulatory Impact of ClpP Protease of Staphylococcus aureus on Regulons Involved in Virulence, Oxidative Stress Response, Autolysis, and DNA Repair. J. Bacteriol. 2006, 188, 5783–5796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michalik, S.; Bernhardt, J.; Otto, A.; Moche, M.; Becher, D.; Meyer, H.; Lalk, M.; Schurmann, C.; Schlüter, R.; Kock, H.; et al. Life and Death of Proteins: A Case Study of Glucose-Starved Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2012, 11, 558–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Römling, U.; Galperin, M.Y.; Gomelsky, M. Cyclic Di-GMP: The First 25 Years of a Universal Bacterial Second Messenger. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2013, 77, 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krystynowicz, A.; Czaja, W.; Wiktorowska-Jezierska, A.; Gonçalves-Miśkiewicz, M.; Turkiewicz, M.; Bielecki, S. Factors Affecting the Yield and Properties of Bacterial Cellulose. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2002, 29, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, L.E.; Olsen, J.E.; Foster, J.W.; Ingmer, H. ClpP Is Involved in the Stress Response and Degradation of Misfolded Proteins in Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium. Microbiology 2002, 148, 2727–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-García, Y.; Meza-Contreras, J.C.; Gutiérrez-Ortega, J.A.; Manríquez-González, R. In Vivo Modification of Microporous Structure in Bacterial Cellulose by Exposing Komagataeibacter xylinus Culture to Physical and Chemical Stimuli. Polymers 2022, 14, 4388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryngajłło, M.; Jacek, P.; Cielecka, I.; Kalinowska, H.; Bielecki, S. Effect of Ethanol Supplementation on the Transcriptional Landscape of Bionanocellulose Producer Komagataeibacter xylinus E25. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 6673–6688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, T.; Sugano, Y.; Nakai, T.; Shoda, M. Effects of Acetan on Production of Bacterial Cellulose by Acetobacter xylinum. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2002, 66, 1677–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ryngajłło, M.; Cielecka, I.; Daroch, M. Complete Genome Sequence and Transcriptome Response to Vitamin C Supplementation of Novacetimonas hansenii SI1—Producer of Highly-Stretchable Cellulose. New Biotechnol. 2024, 81, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambrook, J.; Russell, D.W. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 3rd ed.; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, C.H.; Teng, H.Y.; Lee, C.K. Knock-out of Glucose Dehydrogenase Gene in Gluconacetobacter xylinus for Bacterial Cellulose Production Enhancement. Biotechnol. Bioprocess. Eng. 2015, 20, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahn, C.E.; Selimi, D.A.; Barak, J.D.; Charkowski, A.O. The Dickeya dadantii Biofilm Matrix Consists of Cellulose Nanofibres, and Is an Emergent Property Dependent upon the Type Iii Secretion System and the Cellulose Synthesis Operon. Microbiology 2011, 157, 2733–2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Strain | Characteristics of Cellulose | Result After 7 Days |

|---|---|---|

| E25 | Density (g/m3) | 3.617 ± 0.364 |

| Yield (g/L) | 1.451 ± 0.090 | |

| Free EPS (mg/L) | 189.0 ± 14.93 | |

| HE-EPS yield (mg/L) (percentage of BNC) | 34.00 ± 7.94 (~2.34%) | |

| E25 clpP:amp | Density (g/m3) | 4.873 ± 0.307 |

| Yield (g/L) | 1.429 ± 0.113 | |

| Free EPS (mg/L) | 224.0 ± 6.11 | |

| HE-EPS yield (mg/L) (percentage of BNC) | 46.5 ± 12.02 (~3.25%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jędrzejczak-Krzepkowska, M.; Ludwicka, K.; Bielecki, S. The Effect of clpP Gene Disruption on Cell Morphology, Growth, and the Ability to Synthesize Cellulose of Komagataeibacter xylinus E25. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12047. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412047

Jędrzejczak-Krzepkowska M, Ludwicka K, Bielecki S. The Effect of clpP Gene Disruption on Cell Morphology, Growth, and the Ability to Synthesize Cellulose of Komagataeibacter xylinus E25. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12047. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412047

Chicago/Turabian StyleJędrzejczak-Krzepkowska, Marzena, Karolina Ludwicka, and Stanislaw Bielecki. 2025. "The Effect of clpP Gene Disruption on Cell Morphology, Growth, and the Ability to Synthesize Cellulose of Komagataeibacter xylinus E25" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12047. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412047

APA StyleJędrzejczak-Krzepkowska, M., Ludwicka, K., & Bielecki, S. (2025). The Effect of clpP Gene Disruption on Cell Morphology, Growth, and the Ability to Synthesize Cellulose of Komagataeibacter xylinus E25. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12047. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412047