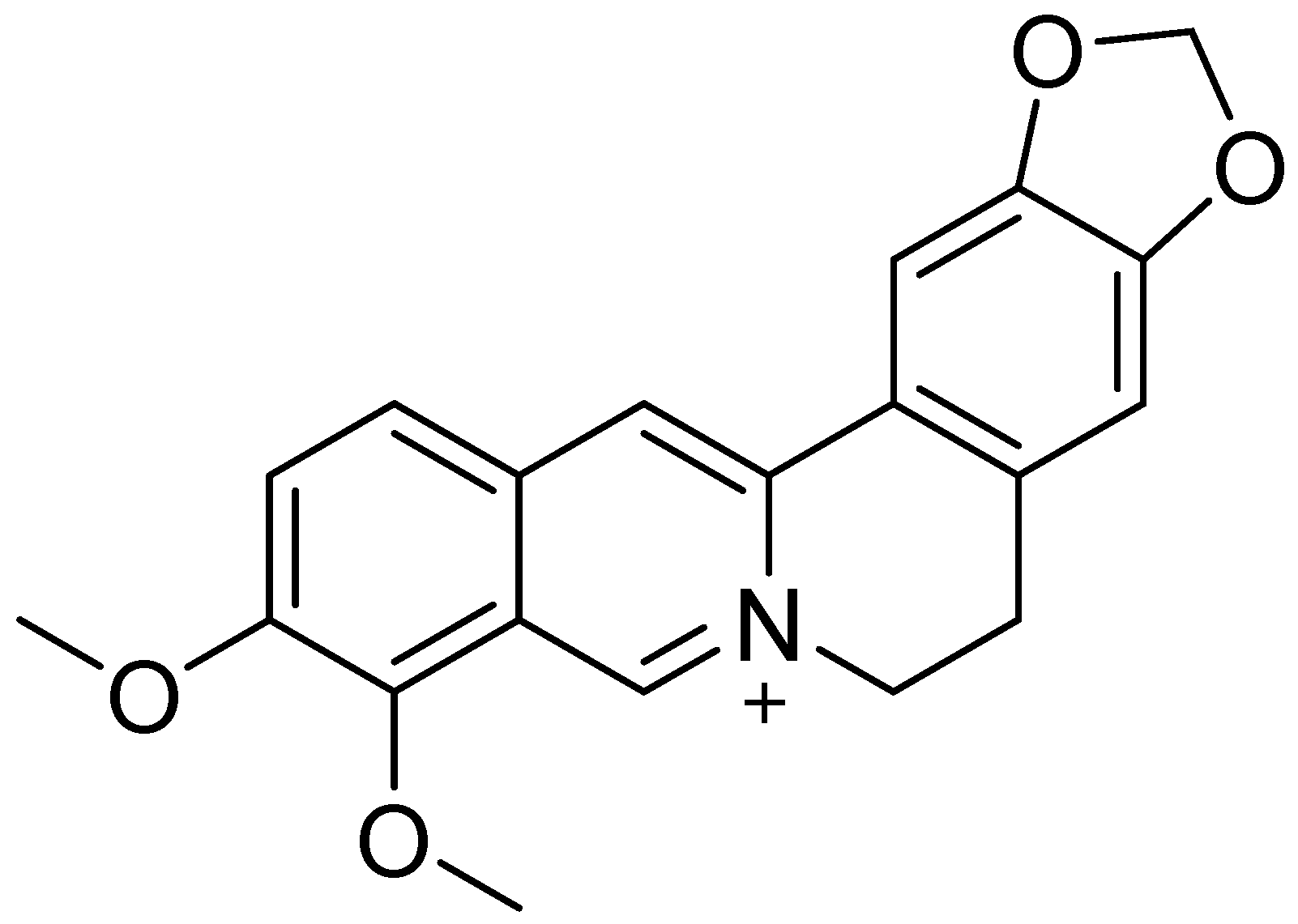

Berberine in Bowel Health: Anti-Inflammatory and Gut Microbiota Modulatory Effects

Abstract

1. Introduction

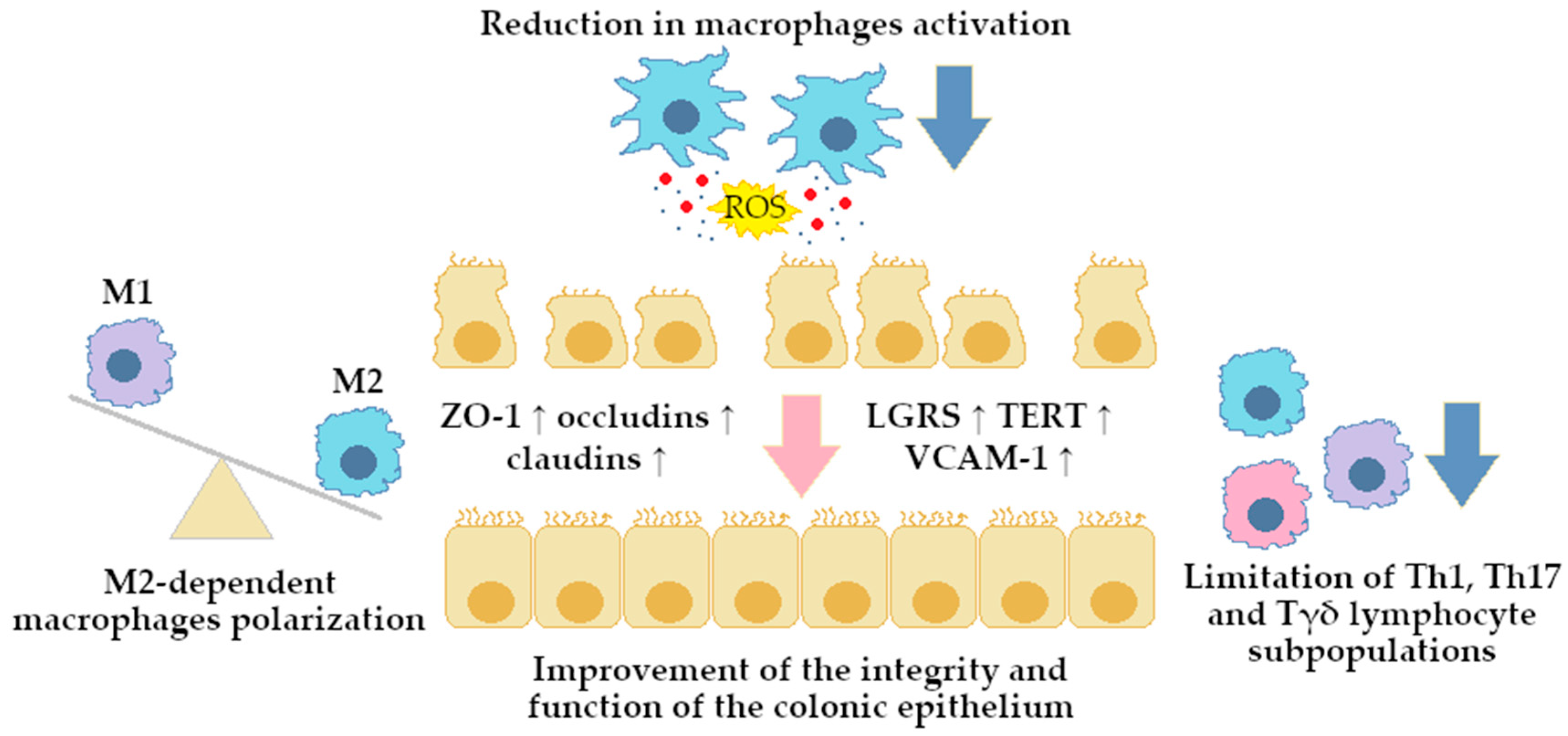

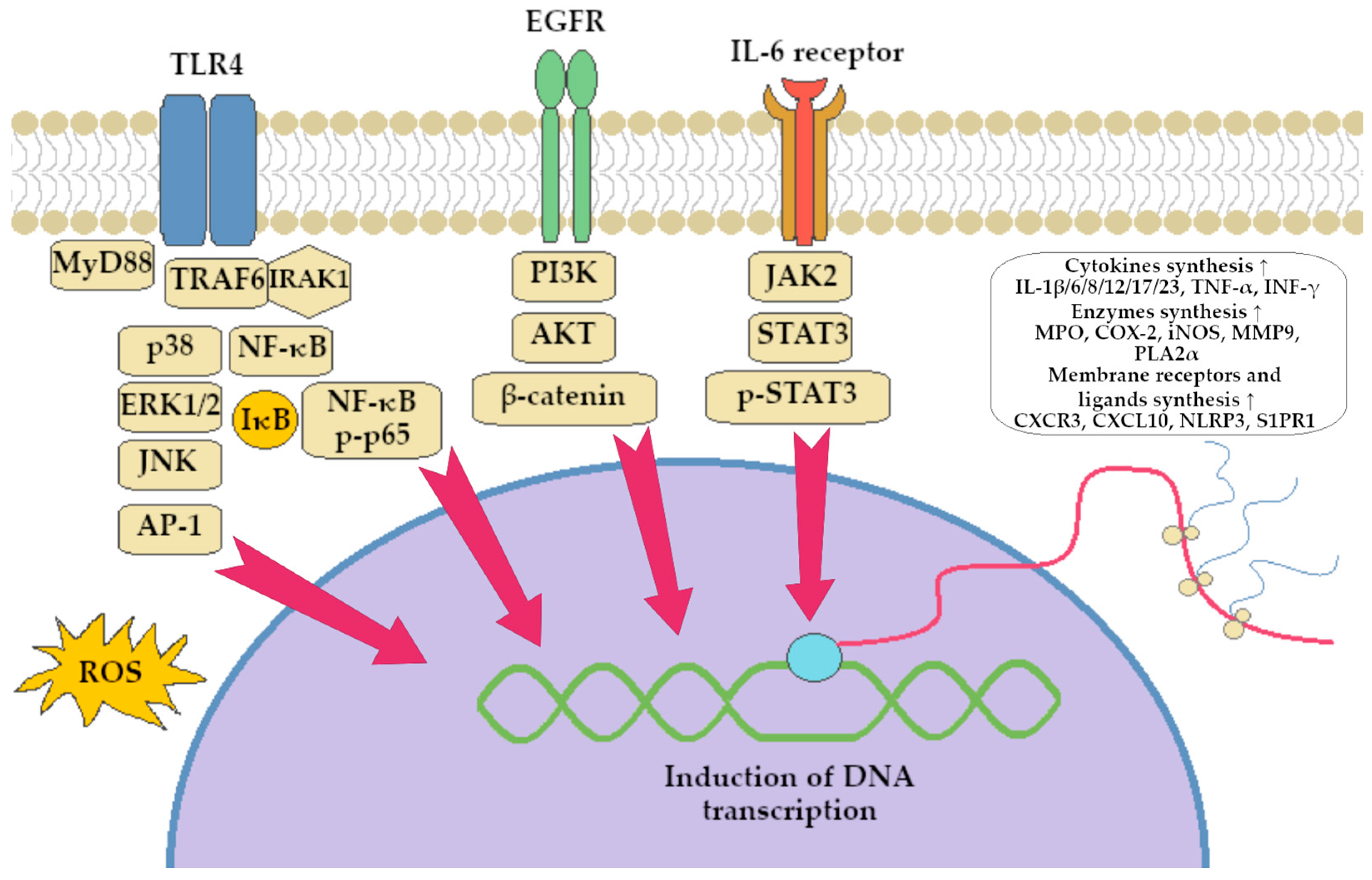

2. Berberine Role in Colitis Alleviation

2.1. BRB Derivatives

2.2. BRB in Combination with Other Compounds

2.3. BRB Advanced Delivery Systems

3. Berberine—Effect on the Development and the Course of Bacterial Infections

3.1. Effect on Toxic Bacterial Products

3.2. Inhibition of Toxicoinfections

3.3. Invasive Infections

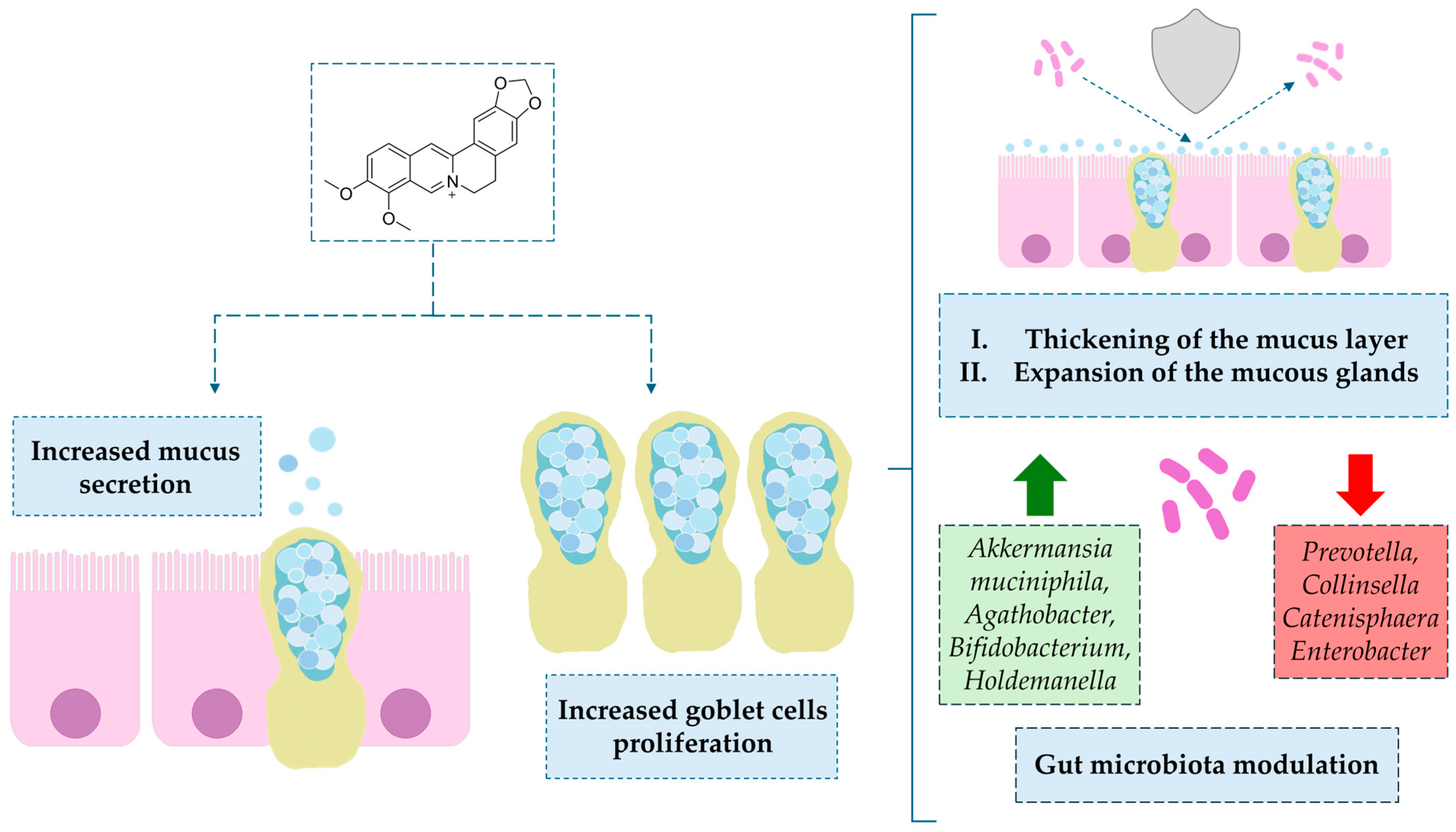

4. Berberine Modulating Effect on Gut Microbiota via Intestinal Barrier

4.1. Direct Modulation

4.1.1. Impact on Mucin-Secreting Goblet Cells

4.1.2. Intestinal Disorders

4.1.3. Liver Disorders

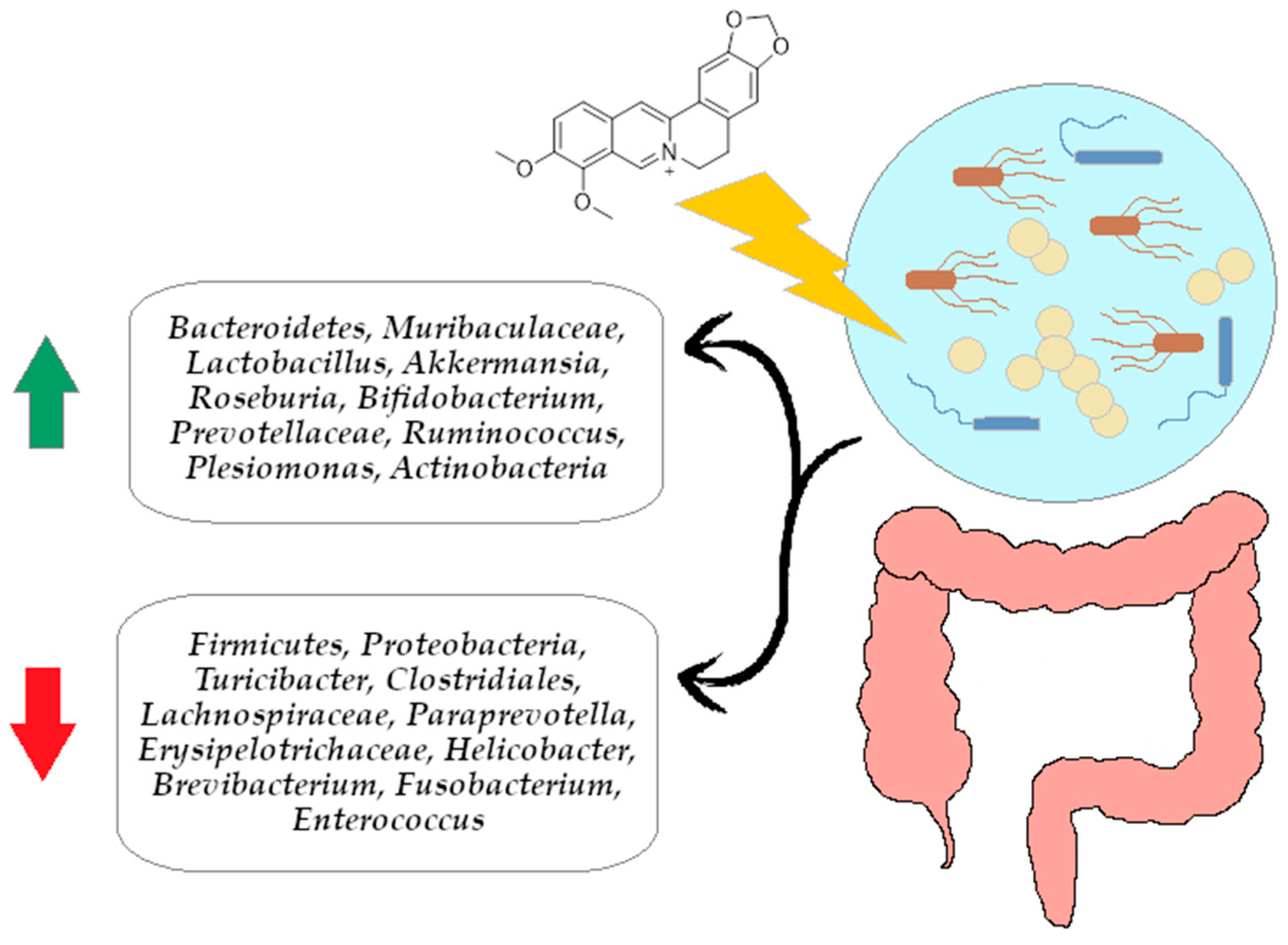

4.1.4. The Effect of Berberine on the Bacteroidetes/Firmicutes Ratio

4.2. Indirect Modulation

4.3. Nanoparticles in Addition to Berberine

5. Limitations of the Evidence Presented

6. Research Gaps in the Field of Berberine

7. Conclusions

8. Materials and Methods

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Cryan, J.F.; O’riordan, K.J.; Cowan, C.S.M.; Sandhu, K.V.; Bastiaanssen, T.F.S.; Boehme, M.; Codagnone, M.G.; Cussotto, S.; Fulling, C.; Golubeva, A.V.; et al. The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 1877–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Góralczyk-Bińkowska, A.; Szmajda-Krygier, D.; Kozłowska, E. The microbiota–gut–brain axis in psychiatric disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, Y.; Khan, A.U. The Interplay between the Gut-Brain Axis and the Microbiome: A Perspective on Psychiatric and Neurodegenerative Disorders. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 1030694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Li, Z.; Liu, S.; Zhang, D. Global, regional, and national burden of 10 digestive diseases in 204 countries and territories from 1990 to 2019. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1061453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, P.; Ishimoto, T.; Fu, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y. The Gut Microbiota in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 733992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azer, S.; Tuma, F. Infectious Colitis; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/nbk544325/ (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Nielsen, O.H.; Fernandez-Banares, F.; Sato, T.; Pardi, D.S. Microscopic Colitis: Etiopathology, Diagnosis, and Rational Management. eLife 2022, 11, e79397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FitzGerald, J.F.; III, L.O.H. Ischemic Colitis. Clin. Colon Rectal Surg. 2015, 28, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitropoulou, M.-A.; Fradelos, E.C.; Lee, K.Y.; Malli, F.; Tsaras, K.; Christodoulou, N.G.; Papathanasiou, I.V. Quality of Life in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Importance of Psychological Symptoms. Cureus 2022, 14, e28502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.; Sebastian, S.A.; Parmar, M.P.; Ghadge, N.; Padda, I.; Keshta, A.S.; Minhaz, N.; Patel, A. Factors Influencing the Quality of Life in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Comprehensive Review. Dis. A Mon. 2024, 70, 101672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ananthakrishnan, A.N. Epidemiology and Risk Factors for IBD. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 12, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Pang, Z.; Chen, W.; Ju, S.; Zhou, C. The Epidemiology and Risk Factors of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 8, 22529–22542. [Google Scholar]

- Saez, A.; Herrero-Fernandez, B.; Gomez-bris, R.; Hector, S.; Gonzalez-Granado, J.M. Pathophysiology of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Innate Immune System. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, L.H.; Schreiber, H.L.; Mazmanian, S.K. The Gut Microbiota–Brain Axis in Behaviour and Brain Disorders. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, E.A.; Nance, K.; Chen, S. The Gut—Brain Axis. Annu. Rev. Med. 2022, 73, 439–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duda-Madej, A.; Stecko, J.; Szymańska, N.; Miętkiewicz, A.; Szandruk-Bender, M. Amyloid, Crohn’s Disease, and Alzheimer’s Disease-Are They Linked? Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1393809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jandhyala, S.M.; Talukdar, R.; Subramanyam, C.; Vuyyuru, H.; Sasikala, M.; Reddy, D.N. Role of the Normal Gut Microbiota. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 8836–8847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdes, A.M.; Walter, J.; Segal, E.; Spector, T.D. Role of the Gut Microbiota in Nutrition and Health. BMJ 2018, 361, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahwa, R.; Goyal, A.; Jialal, I. Chronic Inflammation; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/nbk493173/ (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Hannoodee, S.; Nasuruddin, D. Acute Inflammatory Response; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/nbk556083/ (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Petagna, L.; Antonelli, A.; Ganini, C.; Bellato, V.; Campanelli, M.; Divizia, A.; Efrati, C.; Franceschilli, M.; Guida, A.M.; Ingallinella, S.; et al. Pathophysiology of Crohn’s Disease Inflammation and Recurrence. Biol. Direct 2020, 15, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Q. A Comprehensive Review and Update on the Pathogenesis of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Immunol. Res. 2019, 2019, 7247238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, A. The Use of 5-Aminosalicylates in Crohn’s Disease: A Retrospective Study Using the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2020, 33, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iolascon, A.; Bianchi, P.; Andolfo, I.; Russo, R.; Barcellini, W.; Fermo, E.; Toldi, G.; Ghirardello, S.; Rees, D.; Van Wijk, R.; et al. Recommendations for Diagnosis and Treatment of Methemoglobinemia. Am. J. Hematol. 2021, 96, 1666–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenlea, T. Immunosuppressive Therapies for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabisiak, A.; Caban, M.; Dudek, P.; Strigáč, A.; Ewa, M.-W.; Talar-Wojnarowska, R. Advancements in Dual Biologic Therapy for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: Efficacy, Safety, and Future Directions. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2025, 18, 17562848241309871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loftus, E.V.; Panés, J.; Lacerda, A.P.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; D’Haens, G.; Panaccione, R.; Reinisch, W.; Louis, E.; Chen, M.; Nakase, H.; et al. Upadacitinib Induction and Maintenance Therapy for Crohn’s Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 1966–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caviglia, G.P.; Garrone, A.; Bertolino, C.; Vanni, R.; Bretto, E.; Poshnjari, A.; Tribocco, E.; Frara, S.; Armandi, A.; Astegiano, M.; et al. Epidemiology of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Population Study in a Healthcare District of North-West Italy. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neag, M.A.; Mocan, A.; Echeverría, J.; Pop, R.M.; Bocsan, C.I.; Crisan, G.; Buzoianu, A.D. Berberine: Botanical Occurrence, Traditional Uses, Extraction Methods, and Relevance in Cardiovascular, Metabolic, Hepatic, and Renal Disorders. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Geng, Y.-N.; Jiang, J.-D.; Kong, W.-J. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activities of Berberine in the Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 2014, 289264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, R.-G.; Huang, S.-Y.; Wu, S.-X.; Zhou, D.-D.; Yang, Z.-J.; Saimaiti, A.; Zhao, C.-N.; Shang, A.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Gan, R.-Y.; et al. Anticancer Effects and Mechanisms of Berberine from Medicinal Herbs: An Update Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 4523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, Y.; Nakashima, K.; Nishino, K.; Kotani, K.; Tomida, J.; Inoue, M.; Kawamura, Y. Berberine Is a Novel Type Efflux Inhibitor Which Attenuates the MexXY-Mediated Aminoglycoside Resistance in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Zhang, J.; Sun, N.; Wang, X.-M.; Wei, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, R.; Pu, Y.; Dai, H.; Ren, B.; et al. Berberine Reverses Multidrug Resistance in Candida Albicans by Hijacking the Drug Efflux Pump Mdr1p. Sci. Bull. 2021, 66, 1895–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Kang, C.; Che, S.; Su, J.; Sun, Q.; Ge, T.; Guo, Y.; Lv, J.; Sun, Z.; Yang, W.; et al. Berberine: A Promising Treatment for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 845591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, D.; Liu, L.; Wu, Z.; Cao, M. Combating Neurodegenerative Diseases with the Plant Alkaloid Berberine: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2018, 17, 563–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, E.; Sharma, G.; Dai, C. Neuroprotective Properties of Berberine: Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Implications. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgazzar, A.H.; Elmonayeri, M. The Pathophysiologic Basis of Nuclear Medicine; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, N.S. Acute Gastroenteritis. Prim Care 2013, 40, 727–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolinger, M.; Torres, J.; Vermeire, S. Seminar Crohn’s Disease. Lancet 2024, 403, 1177–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Gu, P.; Shen, H. Protective Effects of Berberine Hydrochloride on DSS-Induced Ulcerative Colitis in Rats. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2019, 68, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Xi, Y.; Li, S.; Zhao, Q.; Cheng, W.; Wang, Z.; Zhong, J.; Niu, X.; Chen, G. Berberine Ameliorates TNBS Induced Colitis by Inhibiting Inflammatory Responses and Th1/Th17 Differentiation. Mol. Immunol. 2015, 67, 444–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, T.; Yang, Z.; Lv, C.-F.; Zhang, Y. Suppressive Effect of Berberine on Experimental Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Colitis. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2012, 34, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, F.; Wang, L.; Shi, Y.; Cao, H.; Liu, L.; Washington, M.K.; Chaturvedi, R.; Israel, D.A.; Cao, H.; Wang, B.; et al. Berberine Promotes Recovery of Colitis and Inhibits Inflammatory Responses in Colonic Macrophages and Epithelial Cells in DSS-Treated Mice. Am. J. Physiol. Liver Physiol. 2012, 302, G504–G514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Mineshita, S. The Effect of Berberine Chloride on Experimental Colitis in Rats In Vivo and In Vitro. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000, 294, 822–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, I.-A.; Hyun, Y.-J.; Kim, D.-H. Berberine Ameliorates TNBS-Induced Colitis by Inhibiting Lipid Peroxidation, Enterobacterial Growth and NF-ΚB Activation. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2010, 648, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xiao, H.; Hu, D.; Fatima, S.; Lin, C.; Mu, H.; Lee, N.P.; Bian, Z. Berberine Ameliorates Chronic Relapsing Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Colitis in C57BL/6 Mice by Suppressing Th17 Responses. Pharmacol. Res. 2016, 110, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Hua, W.; Wei, Q.; Fang, X.; Zhao, Z.; Ge, C.; Liu, C.; Chen, C.; Tao, Y.; et al. Berberine Inhibits Macrophage M1 Polarization via AKT1/SOCS1/NF-ΚB Signaling Pathway to Protect against DSS-Induced Colitis. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2018, 57, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.-C.; Wang, Y.; Tong, L.-C.; Sun, S.; Liu, W.-Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, R.-M.; Wang, Z.-B.; Li, L. Berberine Alleviates Dextran Sodium Sulfate-Induced Colitis by Improving Intestinal Barrier Function and Reducing Inflammation and Oxidative Stress. Exp. Ther. Med. 2017, 13, 3374–3382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S. The Therapeutic Effects of Berberine Extract On Ulcerative Colitis in Mice. Farmacia 2018, 66, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawano, M.; Takagi, R.; Kaneko, A.; Matsushita, S. Berberine Is a Dopamine D1- and D2-like Receptor Antagonist and Ameliorates Experimentally Induced Colitis by Suppressing Innate and Adaptive Immune Responses. J. Neuroimmunol. 2015, 289, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, K.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, B.; Xu, L.; Tan, L.; Tian, Y.; Li, C.; Zhang, W.; et al. Berberine Inhibits Colitis-Associated Tumorigenesis via Suppressing Inflammatory Responses and the Consequent EGFR Signaling-Involved Tumor Cell Growth. Lab. Investig. 2017, 97, 1343–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Dan, W.; Zhang, C.; Liu, N.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, S. Exploration of Berberine Against Ulcerative Colitis via TLR4/NF-ΚB/HIF-1α Pathway by Bioinformatics and Experimental Validation. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2024, 18, 2847–2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, L.; Huang, T.; Xiao, H.; Wu, P.; Lin, C.; Ning, Z.; Zhao, L.; Kwan, H.Y.A.; Hu, X.; Wong, H.L.X.; et al. Berberine Suppresses Colonic Inflammation in Dextran Sulfate Sodium–Induced Murine Colitis Through Inhibition of Cytosolic Phospholipase A2 Activity. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 576496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Lin, Y.; Gao, L.; Yang, Z.; Wang, S.; Wu, B. Circadian Pharmacological Effects of Berberine on Chronic Colitis in Mice: Role of the Clock Component Rev-Erbα. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2020, 172, 113773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.; Yang, S.; Wang, S.; Cao, Y.; Zhao, R.; Li, X.; Xing, Y.; Liu, L. Effect of Berberine on Atherosclerosis and Gut Microbiota Modulation and Their Correlation in High-Fat Diet-Fed ApoE−/− Mice. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 508422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Wang, D.; Hu, Y.; Pu, P.; Li, D.; Wang, W.; Zhu, B.; Hao, P.; Wang, J.; Xu, X.; et al. Berberine Inhibits Acute Radiation Intestinal Syndrome in Human with Abdomen Radiotherapy. Med. Oncol. 2010, 27, 919–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, P.; Luan, H.; Jiang, H.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, R. Demethyleneberberine Alleviated the Inflammatory Response by Targeting MD-2 to Inhibit the TLR4 Signaling. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1130404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.-H.; Li, J.; Zhang, H.-J.; Deng, A.-J.; Wu, L.-Q.; Li, Z.-H.; Song, H.-R.; Wang, W.-J.; Qin, H.-L. Versatile Methods for Synthesizing Organic Acid Salts of Quaternary Berberine-Type Alkaloids as Anti-Ulcerative Colitis Agents. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2016, 18, 576–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Long, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, Q.; Wu, H.; Guo, Z.; Li, Y.; Niu, Y.; Li, C.; et al. Evidence for the Complementary and Synergistic Effects of the Three-Alkaloid Combination Regimen Containing Berberine, Hypaconitine and Skimmianine on the Ulcerative Colitis Rats Induced by Trinitrobenzene-Sulfonic Acid. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 651, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, M.; Xiao, H.; Fu, H.; Ho, A.; Lin, C.; Huang, Y.; Lin, G.; Bian, Z. Addition of Berberine to 5-Aminosalicylic Acid for Treatment of Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Chronic Colitis in C57BL/6 Mice. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0144101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.-J.; Jang, S.-E.; Hyam, S.R.; Han, M.J.; Kim, D.-H. The Rhizome Mixture of Anemarrhena asphodeloides and Coptidis chinensis Ameliorates Acute and Chronic Colitis in Mice by Inhibiting the Binding of Lipopolysaccharide to TLR4 and IRAK1 Phosphorylation. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 2014, 809083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xu, H.; Zhang, L.; Wang, S.; Lu, D.; Chen, M.; Wu, B. Chronoeffects of the Herbal Medicines Puerariae Radix and Coptidis Rhizoma in Mice: A Potential Role of REV-ERBα. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 707844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Wei, P.; Li, W.; Liu, Q.; Chen, S.; Hu, C.; Guo, X.; Ma, X.; Zeng, J.; Zhang, Y. Pharmacological Effects of Berberine on Models of Ulcerative Colitis: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review of Animal Studies. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 937029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Zheng, H.; Xu, S.; Kong, J.; Gao, F.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Dai, Z.; Jiang, X.; Ding, X.; et al. Novel Natural Carrier-Free Self-Assembled Nanoparticles for Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis by Balancing Immune Microenvironment and Intestinal Barrier. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2023, 12, e2301826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Chen, Y.; Shi, M.; Xu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Y. Gegen Qinlian Decoction Alleviates Experimental Colitis via Suppressing TLR4/NF-ΚB Signaling and Enhancing Antioxidant Effect. Phytomedicine 2016, 23, 1012–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.-F.; Sun, T.; Li, S.; Huang, Q.; Yue, L.; Zhu, L.; Wang, R. Oral Colon-Targeted Konjac Glucomannan Hydrogel Constructed through Noncovalent Cross-Linking by Cucurbit [8]Uril for Ulcerative Colitis Therapy. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2020, 3, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Wu, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Wu, C.; Yuan, M.; Su, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z. Berberine-Loaded Nanostructured Lipid Carriers Enhance the Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 3937–3951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Xie, Q.; Xu, H.; Zhang, T.; Li, X.; Tian, Y.; Lan, H.; Kong, L.; Zhang, Z. Yeast Microcapsule Mediated Natural Products Delivery for Treating Ulcerative Colitis through Anti-Inflammatory and Regulation of Macrophage Polarization. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 31085–31098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Huang, J.; Fan, Y.; Long, H.; Liang, M.; Chen, Q.; Wang, Z.; Wu, C.; Wang, Y. Macrophage-Targeted Berberine-Loaded β-Glucan Nanoparticles Enhance the Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis. Int. J. Nanomed. 2022, 17, 5303–5314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Li, M.; Zhang, G.; Gao, C.; Wang, S.; Zhang, T.; Ma, C.; Wang, L.; Zhu, Q. Micro- and Nanoencapsulated Hybrid Delivery System (MNEHDS): A Novel Approach for Colon-Targeted Oral Delivery of Berberine. Mol. Pharm. 2021, 18, 1573–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.; Fan, H.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, F.; Li, M.; Zhou, H.; Guo, W.; Zhang, Z.; Kang, Z.; Gui, Y.; et al. Berberine Ameliorates DSS-Induced Intestinal Mucosal Barrier Dysfunction through Microbiota-Dependence and Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 18, 1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, K.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.Y.; Li, B.; Zhu, W.L.; Shi, J.Y.; Jia, Q.; Li, Y.M. Advances in the Study of Berberine and Its Derivatives: A Focus on Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Tumor Effects in the Digestive System. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2017, 38, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sack, R.B.; Froehlich, J.L. Berberine Inhibits Intestinal Secretory Response of Vibrio Cholerae and Escherichia Coli Enterotoxins. Infect. Immun. 1982, 35, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Sha, S.; Liang, S.; Zhao, L.; Liu, L.; Chai, N.; Wang, H.; Wu, K. Berberine Increases the Expression of NHE3 and AQP4 in SennosideA-Induced Diarrhoea Model. Fitoterapia 2012, 83, 1014–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Xueying, L.; Chunlin, L.; Wen, X.; Rongrong, Z.; Jing, H.; Meilan, J.; Yuwei, X.; Zili, W. Effect of Berberine on LPS-Induced Expression of NF-ΚB/MAPK Signalling Pathway and Related Inflammatory Cytokines in Porcine Intestinal Epithelial Cells. Innate Immun. 2020, 26, 627–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, S.; Ma, L.; Wang, G.; Yang, J.; Zhang, M.; Wang, X.; Su, J.; Xie, M. In Vitro Antimicrobial Activity and the Mechanism of Berberine Against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Isolated from Bloodstream Infection Patients. Infect. Drug Resist. 2022, 15, 1933–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Yang, K.; Hong, Y.; Gong, Y.; Ni, J.; Yang, N.; Ding, W. A New Perspective on the Antimicrobial Mechanism of Berberine Hydrochloride Against Staphylococcus Aureus Revealed by Untargeted Metabolomic Studies. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 917414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Wang, W.; Cai, L.; Yang, T. Potentiation and Mechanism of Berberine as an Antibiotic Adjuvant Against Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria. Infect. Drug Resist. 2023, 16, 7313–7326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Wang, F.; Huang, F.; Yang, M.; He, D.; Deng, L. Targeting Effect of Berberine on Type I Fimbriae of Salmonella Typhimurium and Its Effective Inhibition of Biofilm. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 1563–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aswathanarayan, J.B.; Vittal, R.R. Inhibition of Biofilm Formation and Quorum Sensing Mediated Phenotypes by Berberine in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa and Salmonella Typhimurium. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 36133–36141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.S.; Lee, T.H.; Son, S.J.; Park, Y.R.; Lee, T.Y.; Javed, A.; Choe, D.; Kim, S.L.; Kim, S.U.; Lee, S.H. Antibacterial Effect of Berberrubine on the Salmonella Typhimurium Type III Secretion System. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2023, 18, 1934578X231189077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Liu, L.G.; Peng, J.P.; Leng, W.C.; Yang, J.; Jin, Q. Transcriptional Profile of the Shigella Flexneri Response to an Alkaloid: Berberine. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2010, 303, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duda-Madej, A.; Gagat, P.; Wiśniewski, J.; Viscardi, S.; Krzyżek, P. Impact of Isoquinoline Alkaloids on the Intestinal Barrier in a Colonic Model of Campylobacter Jejuni Infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO Warns of Widespread Resistance to Common Antibiotics Worldwide; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025; Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/13-10-2025-who-warns-of-widespread-resistance-to-common-antibiotics-worldwide (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Qassadi, F.I.; Zhu, Z.; Monaghan, T.M. Plant-Derived Products with Therapeutic Potential against Gastrointestinal Bacteria. Pathogens 2023, 12, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, L.; Li, N.; Gong, J.; Li, Q.; Zhu, W.; Li, J. Berberine Ameliorates Intestinal Epithelial Tight-Junction Damage and down-Regulates Myosin Light Chain Kinase Pathways in a Mouse Model of Endotoxinemia. J. Infect. Dis. 2011, 203, 1602–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Fan, C.; Lu, H.; Feng, C.; He, P.; Yang, X.; Xiang, C.; Zuo, J.; Tang, W. Protective Role of Berberine on Ulcerative Colitis through Modulating Enteric Glial Cells–Intestinal Epithelial Cells–Immune Cells Interactions. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2020, 10, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikder, A.; Lee, H.J.; Lee, S.Y.; Bae, H.S.; Kim, J.; Chang, G.T.; Lee, C.J. Effect of Berberine on MUC5AC Mucin Gene Expression and Mucin Production from Human Airway Epithelial Cells. Biomol. Ther. 2011, 19, 320–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samsuzzamana, M.; Uddin, S.; Shah, M.A.; Bijo, M. Natural Inhibitors on Airway Mucin: Molecular Insight into the Therapeutic Potential Targeting MUC5AC Expression and Production. Life Sci. 2019, 231, 116485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Yu, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Su, W.; Fan, Q.; Wu, C.; Wu, S. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy Berberine, a Potential Prebiotic to Indirectly Promote Akkermansia Growth through Stimulating Gut Mucin Secretion. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 139, 111595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, M.; Liu, X.; Ji, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X. Berberine Alleviates Enterotoxigenic Escherichia Coli -Induced Intestinal Mucosal Barrier Function Damage in a Piglet Model by Modulation of the Intestinal Microbiome. Front. Nutr. 2025, 11, 1494348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Hao, Z.; Zhao, H.; Duan, X.; Jia, D. Berberine Alleviates Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction in Glucolipid Metabolism Disorder Hamsters by Modulating Gut Microbiota and Gut-Microbiota-Related Tryptophan Metabolites. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2022, 103, 1464–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Zhang, S.; Li, R.; Ma, C.; Zhang, Q.; Xia, F.; Zhou, B.; Xie, Z.; Liao, Z. Berberine Alleviates Inflammation and Suppresses PLA2-COX-2-PGE2-EP2 Pathway through Targeting Gut Microbiota in DSS-Induced Ulcerative Colitis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2024, 695, 149411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooks, M.G.; Veiga, P.; Wardwell-Scott, L.H.; Tickle, T.; Segata, N.; Michaud, M.; Gallini, C.A.; Beal, C.; van Hylckama-Vlieg, J.E.T.; Ballal, S.A.; et al. Gut Microbiome Composition and Function in Experimental Colitis during Active Disease and Treatment-Induced Remission. ISME J. 2014, 8, 1403–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, W.; Zhang, B.; Yin, J.; Liuqi, S.; Wang, J.; Peng, B.; Wang, S. Fucoidan Ameliorated Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Ulcerative Colitis by Modulating Gut Microbiota and Bile Acid Metabolism. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 14864–14876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Zhao, L.; Zhou, W.; Li, Y.; Hu, H.; Wang, Z. Synergistic Effect of Berberine Hydrochloride and Dehydrocostus Lactone in the Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis: Take Gut Microbiota as the Target. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 124, 111009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, G.; Zhu, T.; Zhang, Z.; Xiong, L.; Hu, H.; Liu, H. Berberine Improves DSS-Induced Colitis in Mice by Modulating the Fecal-Bacteria-Related Bile Acid Metabolism. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 167, 115430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, M.; Pang, X.; Xu, J.; Kang, C.; Li, M. Structural Changes of Gut Microbiota during Berberine- Mediated Prevention of Obesity and Insulin Resistance in High-Fat Diet-Fed Rats. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, W.; Dong, S.; Luo, X.; Liu, J.; Wei, B.; Du, W.; Yang, L.; Luo, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; et al. Berberine Improves Colitis by Triggering AhR Activation by Microbial Tryptophan Catabolites. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 164, 105358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Gao, Z.; Yang, F.; Yang, Y.; Chen, L.; Han, L.; Zhao, N.; Xu, J.; Wang, X.; Ma, Y.; et al. Antidiabetic Effects of Gegen Qinlian Decoction via the Gut Microbiota Are Attributable to Its Key Ingredient Berberine. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2020, 18, 721–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Cui, H.; Li, T.; Qi, J.; Chen, H.; Gao, F.; Tian, X.; Mu, Y.; He, R.; Lv, S.; et al. Synergistic Effect of Berberine-Based Chinese Medicine Assembled Nanostructures on Diarrhea-Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome In Vivo. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 565501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Li, C.; Lei, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, S.; Liu, Q.; Huan, Y.; Sun, S.; Shen, Z. Stachyose Improves the Effects of Berberine on Glucose Metabolism by Regulating Intestinal Microbiota and Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Spontaneous Type 2 Diabetic KKAy Mice. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 578943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Li, J.; Ni, J.; Zhang, C.; Jia, J.; Wu, G.; Sun, H.; Wang, S. Berberine Relieves Metabolic Syndrome in Mice by Inhibiting Liver Inflammation Caused by a High-Fat Diet and Potential Association With Gut Microbiota. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 752512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, D.; Su, L.; Tai, Y.-L.; Way, G.W.; Zeng, J.; Yan, Q.; Xu, Y.; Wang, X.; Gurley, E.C.; et al. Therapeutic Potential of Berberine in Attenuating Cholestatic Liver Injury: Insights from a PSC Mouse Model. Cell Biosci. 2024, 14, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhou, J.; He, Z.; Li, H. Bacteroides and NAFLD: Pathophysiology and Therapy. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1288856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrell, J.M.; Chiang, J.Y.L. Understanding Bile Acid Signaling in Diabetes: From Pathophysiology to Therapeutic Targets. Diabetes Metab. J. 2019, 43, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Zhu, W.; Zhou, J.; Shen, T. The Combination of Berberine and Evodiamine Ameliorates High-Fat Diet-Induced Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Associated with Modulation of Gut Microbiota in Rats. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2022, 55, e12096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yan, J.; Zhang, P.; Zhou, X. Berberine Maintains Gut Microbiota Homeostasis and Ameliorates Liver Inflammation in Experimental Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Chin. J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 23, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.-H.; Shen, H.-R.; Wang, L.-L.; Luo, Z.-G.; Zhang, J.-L.; Zhang, H.-J.; Gao, T.-L.; Han, Y.-X.; Jiang, J.-D. Berberine Is a Potential Alternative for Metformin with Good Regulatory Effect on Lipids in Treating Metabolic Diseases. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 163, 114754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.H.; Liu, X.Z.; Pan, W.; Zou, D.J. Berberine Protects against Diet-Induced Obesity through Regulating Metabolic Endotoxemia and Gut Hormone Levels. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 15, 2765–2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Pan, Q.; Cai, W.; Shen, F.; Chen, G.; Xu, L.; Fan, J. Modulation of Gut Microbiota by Berberine Improves Steatohepatitis in High-Fat Diet-Fed Balb/C Mice. Arch. Iran. Med. 2016, 19, 197–203. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.; Xiong, J.; Chen, G.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Xu, J.; Xu, H. Comparing the Influences of Metformin and Berberine on the Intestinal Microbiota of Rats With Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. In Vivo 2023, 37, 2105–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magne, F.; Gotteland, M.; Gauthier, L.; Zazueta, A.; Pesoa, S.; Navarrete, P.; Balamurugan, R. Nutrients The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes Ratio: A Relevant Marker of Gut Dysbiosis in Obese Patients? Nutrients 2020, 12, 1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Wu, X.; Yang, R.; Chen, F.; Liao, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Wu, Z.; Sun, X.; Wang, L. Effects of Berberine on the Gastrointestinal Microbiota. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 10, 588517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prajapati, S.; Jain, S.; Yadav, H. Age-Related Cognitive Decline and Dementia: Interface of Microbiome-Immune-Neuronal Interactions. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2025, 80, glaf038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Dong, S.; Chen, W.; Li, J.; Luo, E.; Ji, J. Berberine Alleviates Alzheimer’s Disease by Regulating the Gut Microenvironment, Restoring the Gut Barrier and Brain-Gut Axis Balance. Phytomedicine 2024, 129, 155624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Hu, J.; Deng, Y.; Zou, J.; Ding, W.; Peng, Q.; Duan, R.; Sun, J.; Zhu, J. Berberine Mediates the Production of Butyrate to Ameliorate Cerebral Ischemia via the Gut Microbiota in Mice. Nutrients 2023, 16, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Ye, C.; Wu, C.; Zhang, J.; Xu, L.; Wang, X.; Xu, C.; Zhang, J.; Guo, Y.; Yao, Q. Berberine Inhibits High Fat Diet-Associated Colorectal Cancer through Modulation of the Gut Microbiota-Mediated Lysophosphatidylcholine. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2023, 19, 2097–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Lv, S.; Shen, T.; Ye, M.; Wang, D.; Zhou, P.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W. Qinghua Fang Inhibits High-Fat Diet-Induced Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease by Modulating Gut Microbiota. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2021, 10, 3219–3234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, H.; Huo, L.; Shen, W.; Dai, Z.; Bao, Y.; Ji, C.; Zhang, J. Study on the Protective Effect of Berberine Treatment on Sepsis Based on Gut Microbiota and Metabolomic Analysis. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1049106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Huang, J.; Li, T.; Zhang, S.; Wen, C.; Wang, L. Berberine Ameliorates AGVHD by Gut Microbiota Remodelling, TLR4 Signalling Suppression and Colonic Barrier Repairment for NLRP3 Inflammasome Inhibition. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2022, 26, 1060–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Zhang, D.; Zhu, H.; Zhu, J.; Weng, S.; Dong, L.; Liu, T.; Hu, Y.; Shen, X. Berberine Treatment Increases Akkermansia in the Gut and Improves High-Fat Diet-Induced Atherosclerosis in Apoe−/− Mice. Atherosclerosis 2018, 268, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, S.K.; Yadav, D.; Katiyar, S.; Jain, S.; Yadav, H. Postbiotics as Mitochondrial Modulators in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Mechanistic Insights and Therapeutic Potential. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.P.; Dou, Y.X.; Huang, Z.W.; Chen, H.B.; Li, Y.C.; Chen, J.N.; Liu, Y.H.; Huang, X.Q.; Zeng, H.F.; Yang, X.B.; et al. Therapeutic Effect of Oxyberberine on Obese Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Rats. Phytomedicine 2021, 85, 153550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Du, X.; Tian, J.; Kang, X.; Li, Y.; Dai, W.; Li, D.; Zhang, S.; Li, C. Berberine-Loaded Carboxylmethyl Chitosan Nanoparticles Ameliorate DSS-Induced Colitis and Remodel Gut Microbiota in Mice. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 644387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Ai, G.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Q.; Luo, C.; Tan, L.; Lin, G.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zeng, H.; et al. Oxyberberine, a Novel Gut Microbiota-Mediated Metabolite of Berberine, Possesses Superior Anti-Colitis Effect: Impact on Intestinal Epithelial Barrier, Gut Microbiota Profile and TLR4-MyD88-NF-ΚB Pathway. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 152, 104603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Disease | Molecular Action of BRB | References |

|---|---|---|

| Intestinal diseases | ||

| IBS | Microbiota modulation: Proteobacteria, Firmicutes ↓ Bacteroidetes, Verrucomicrobiota, and Akkermansia ↑ | [101] |

| NF-κB signaling pathway silencing | ||

| VIP, 5-HT signaling ↓ | ||

| AChE activity ↓ | ||

| UC | Microbiota modulation: Akkermansiaceae, Lactobacillaceae ↑/Enterococcus, and Ruminococcus spp. ↓ | [71,93,96,97,126] |

| Wnt/β-catenin pathway silencing | ||

| Expression of tight junction proteins: occludins, claudins, ZO-1 ↑ | ||

| Inflammation mediator synthesis: IL-6, IL-17, IL-22, TNF-α, TGF-β ↓/IL-10 ↑ | ||

| Lymphocyte polarization:Th17, ILC1 ↓/Treg, ILC3 ↑ | ||

| Non-intestinal diseases | ||

| NAFLD | Microbiota modulation: Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria ↑/Firmicutes, and Patescibacteria ↓ | [107,108,112,124] |

| Apoptosis prevalence ↓ | ||

| Expression of tight junction proteins: occludins, claudins, ZO-1 ↑ | ||

| IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and VCAM-1 mRNA expression ↓ | ||

| MCP-1, CD11c, CD68, and NOS2 mRNA expression ↓ | ||

| PSC | Bacterial translocation through the intestinal mucosa ↓ | [104] |

| Amelioration of cholestatic liver injury through modifying the gut–liver axis | ||

| Restoration of the bile acid homeostasis | ||

| MCP-1, CD11b, IL-1β, VCAM-1, IL-1α, and CXCL-1 mRNA expression ↓ | ||

| AD | Microbiota modulation: Ligilactobacillus, Akkermansia, and Roseburia ↑ | [116] |

| Synthesis of claudins, ZO-1, and occludins ↑ | ||

| ROS generation and neuroinflammation ↓ | ||

| aGvHD | Microbiota modulation: Adlercreutzia, Dorea, Sutterella, and Plesiomonas ↑ | [121] |

| Alleviation of aGvHD signs and symptoms in the lung, Liver, and colon area | ||

| IL-1β, IL-6, IL-18, INF-γ, TNF-α, and MCP-1 synthesis ↓ | ||

| NLRP3 inflammasome inhibition | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Duda-Madej, A.; Viscardi, S.; Łabaz, J.P.; Topola, E.; Szewczyk, W.; Gagat, P. Berberine in Bowel Health: Anti-Inflammatory and Gut Microbiota Modulatory Effects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412021

Duda-Madej A, Viscardi S, Łabaz JP, Topola E, Szewczyk W, Gagat P. Berberine in Bowel Health: Anti-Inflammatory and Gut Microbiota Modulatory Effects. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412021

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuda-Madej, Anna, Szymon Viscardi, Jakub Piotr Łabaz, Ewa Topola, Wiktoria Szewczyk, and Przemysław Gagat. 2025. "Berberine in Bowel Health: Anti-Inflammatory and Gut Microbiota Modulatory Effects" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412021

APA StyleDuda-Madej, A., Viscardi, S., Łabaz, J. P., Topola, E., Szewczyk, W., & Gagat, P. (2025). Berberine in Bowel Health: Anti-Inflammatory and Gut Microbiota Modulatory Effects. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412021