From Bacterial Diversity to Zoonotic Risk: Characterization of Snake-Associated Salmonella Isolated in Poland with a Focus on Rare O-Ag of LPS, Antimicrobial Resistance and Survival in Human Serum

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

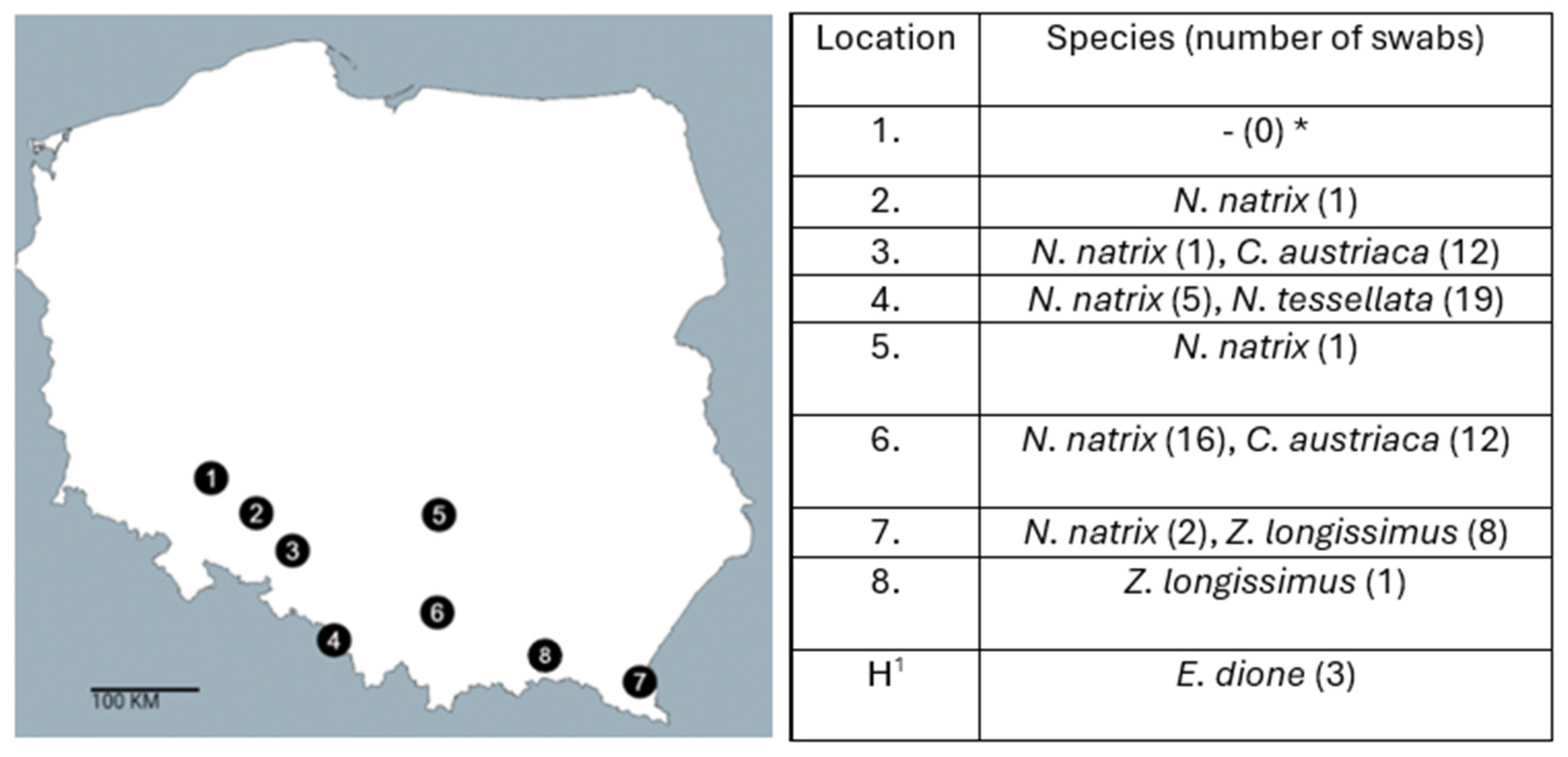

2.1. Sample Collections

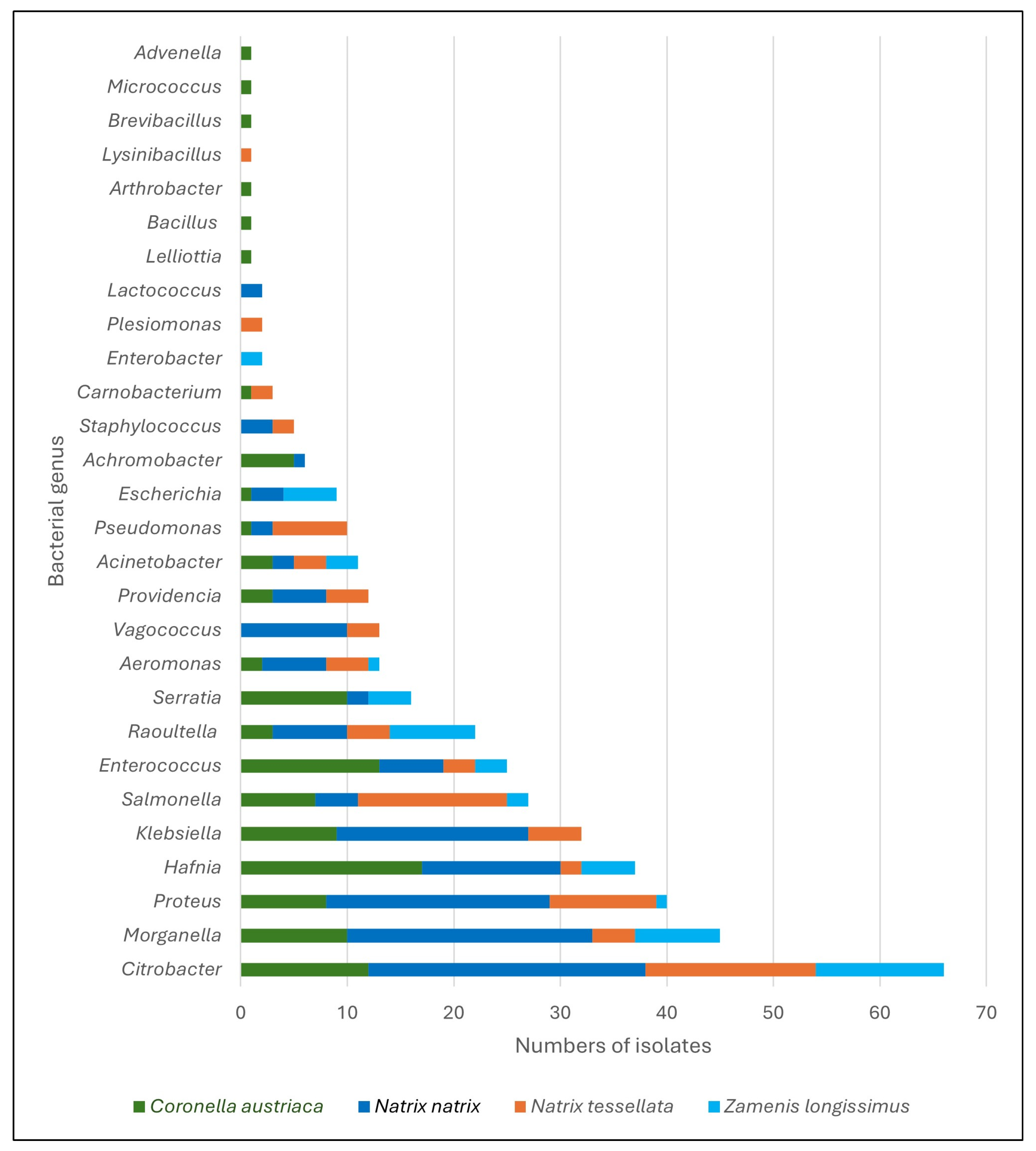

2.2. Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization—Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry Identification (MALDI TOF MS)

2.3. Detection of Salmonella spp. in Snakes

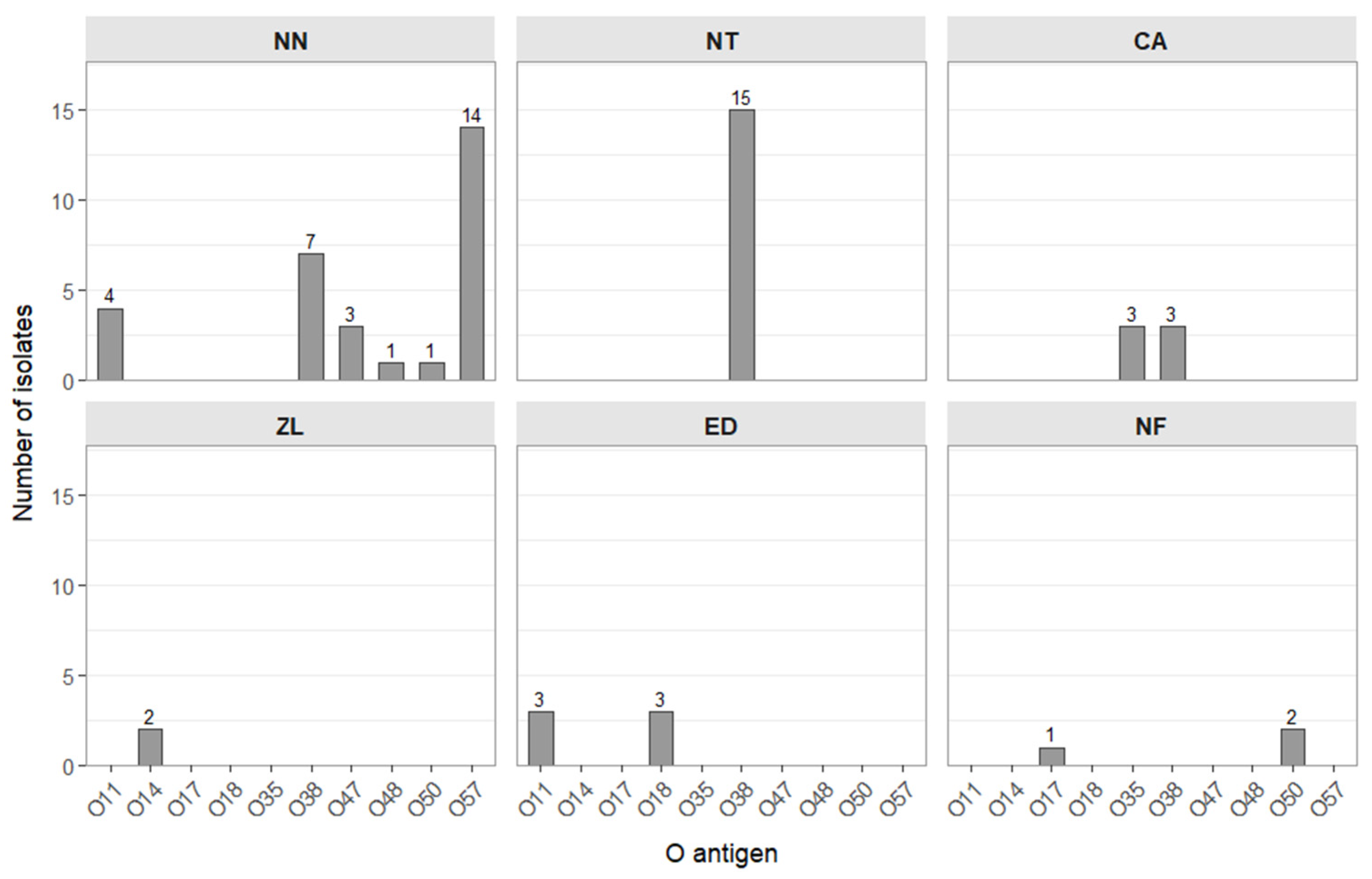

O Antigen Serotyping of Salmonella Isolates

2.4. Resistance to Antimicrobials

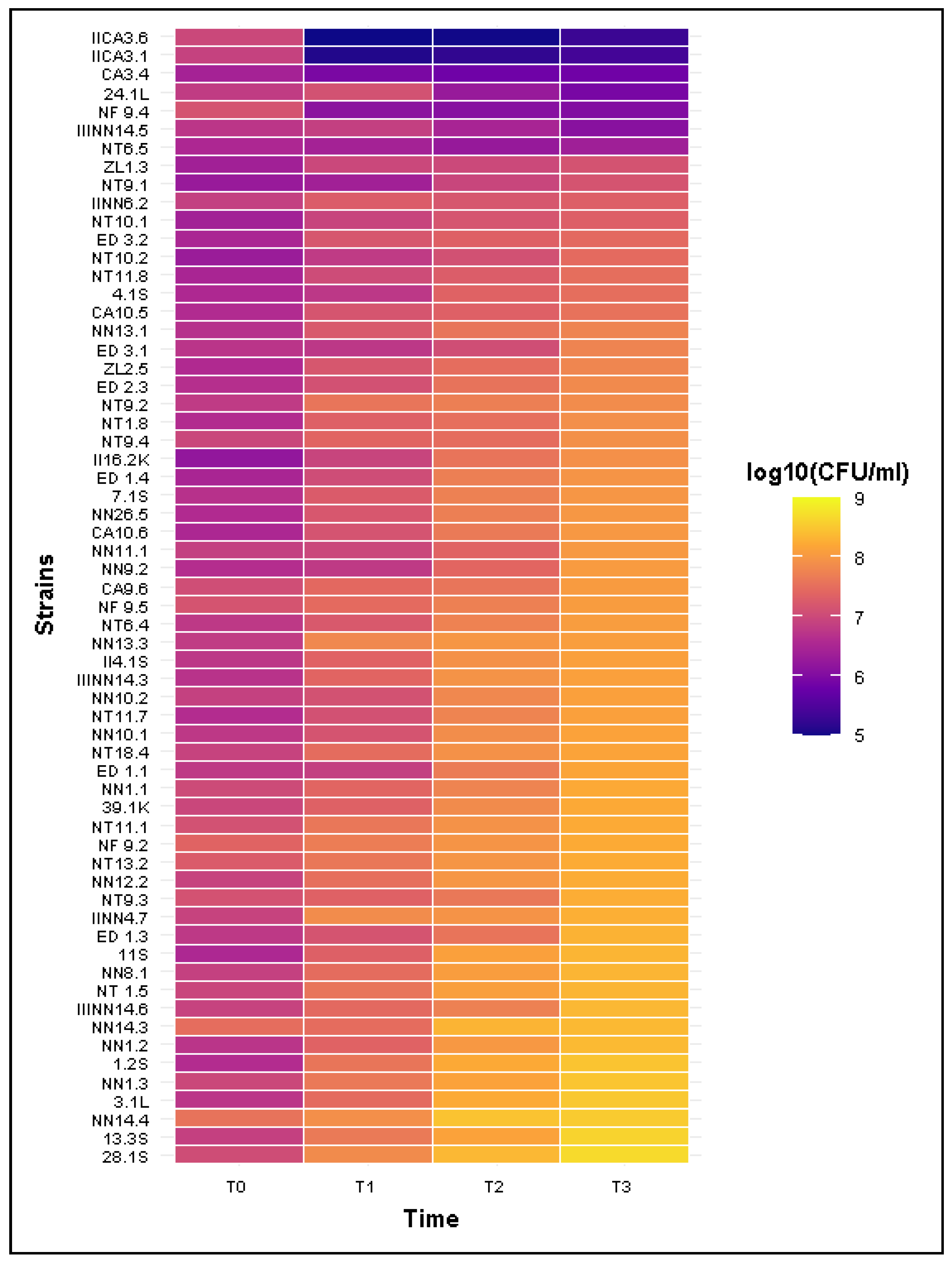

2.5. Resistance to Bactericidal Activity of Human Serum

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Collection of the Cloacal Swabs from Snakes

4.2. Bacteriological Examination

4.3. MALDI-TOF MS Identification

4.4. Determination of O Antigen in Salmonella spp. Isolates

4.5. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST)

4.6. Sensitivity to Bactericidal Activity of HS

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NN | Natrix natrix |

| NT | Natrix tessellata |

| CA | Coronella austriaca |

| ZL | Zamenis longissimus |

| ED | Elaphe dione |

| NF | Nerodia fasciata |

| HS | Human serum |

| CDC | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| NTS | Non-typhoidal salmonellosis |

| pSV | Salmonella virulence plasmid |

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). About One Health. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/one-health/about/index.html (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Horefti, E. The Importance of the One Health Concept in Combating Zoonoses. Pathogens 2023, 12, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament and Council. Directive 2003/99/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 November 2003 on the Monitoring of Zoonoses and Zoonotic Agents, Amending Council Decision 90/424/EEC and Repealing Council Directive 92/117/EEC. Off. J. Eur. Union 2023, 2001, 65–71. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/pl/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32003L0099 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA); European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). The European Union One Health 2023 Zoonoses report. EFSA J 2024, 22, e9106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galán-Relaño, Á.; Valero Díaz, A.; Huerta Lorenzo, B.; Gómez-Gascón, L.; Mena Rodríguez, M.Á.; Carrasco Jiménez, E.; Pérez Rodríguez, F.; Astorga Márquez, R.J. Salmonella and Salmonellosis: An Update on Public Health Implications and Control Strategies. Animals 2023, 13, 3666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, L.; Toppi, V.; Stefanetti, V.; Spata, N.; Rapi, M.C.; Grilli, G.; Addis, M.F.; Di Giacinto, G.; Franciosini, M.P.; Casagrande Proietti, P. High Biofilm-Forming Multidrug-Resistant Salmonella Infantis Strains from the Poultry Production Chain. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, B. Fresh vegetables and fruit as a source of Salmonella bacteria. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2023, 30, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D.F.; Green, M.L.; Warner, J.K.; Davidson, P.C. There’s a Frog in My Salad! A Review of Online Media Coverage for Wild Vertebrates Found in Prepackaged Produce in the United States. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 675, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkevičienė, L.; Butrimaitė-Ambrozevičienė, Č.; Paškevičius, G.; Pikūnienė, A.; Virgailis, M.; Dailidavičienė, J.; Daukšienė, A.; Šiugždinienė, R.; Ruzauskas, M. Serological Variety and Antimicrobial Resistance in Salmonella Isolated from Reptiles. Biology 2022, 11, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dróżdż, M.; Małaszczuk, M.; Paluch, E.; Pawlak, A. Zoonotic potential and prevalence of Salmonella serovars isolated from pets. Infect. Ecol. Epidemiol. 2021, 11, 1975530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, C.; Lorenzo-Rebenaque, L.; Laso, O.; Villora-Gonzalez, J.; Vega, S. Pet Reptiles: A Potential Source of Transmission of Multidrug Resistant Salmonella. Front. Veter Sci. 2021, 7, 613718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlak, A.; Morka, K.; Bury, S.; Antoniewicz, Z.; Wzorek, A.; Cieniuch, G.; Korzeniowska-Kowal, A.; Cichoń, M.; Bugla-Płoskońska, G. Cloacal Gram-Negative Microbiota in Free-Living Grass Snake Natrix natrix from Poland. Curr. Microbiol. 2020, 77, 2166–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pees, M.; Rabsch, W.; Plenz, B.; Fruth, A.; Prager, R.; Simon, S.; Schmidt, V.; Munch, S.; Braun, P. Evidence for the transmission of Salmonella from reptiles to children in Germany, July 2010 to October 2011. Euro Surveill. 2013, 18, 20634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.; Calva, E.; Maloy, S. One Health and Food-Borne Disease: Salmonella Transmission between Humans, Animals, and Plants. Microb. Spectr. 2014, 2, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pees, M.; Brockmann, M.; Steiner, N.; Marschang, R.E. Salmonella in reptiles: A review of occurrence, interactions, shedding and risk factors for human infections. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1251036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, J.; Hammerl, J.A.; Johne, A.; Kappenstein, O.; Loeffler, C.; Nöckler, K.; Rosner, B.; Spielmeyer, A.; Szabo, I.; Richter, M.H. Impact of climate change on foodborne infections and intoxications. J. Health Monit. 2023, 8, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Nicola, M.R.; Rubiola, S.; Cerullo, A.; Basciu, A.; Massone, C.; Zabbia, T.; Dorne, J.L.C.; Acutis, P.L.; Marini, D. Microorganisms in wild European reptiles: Bridging gaps in neglected conditions to inform disease ecology research. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2025, 27, 101113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muslin, C.; Salas-Brito, P.; Coello, D.; Morales-Jadán, D.; Viteri-Dávila, C.; Coral-Almeida, M. Salmonella prevalence and serovar distribution in reptiles: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut Pathog. 2025, 17, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bene, A.F.; Russini, V.; Corradini, C.; Vita, S.; Pecchi, S.; De Marchis, M.L.; Terracciano, G.; Focardi, C.; Montemaggiori, A.; Zuffi, M.A.L.; et al. An extremely rare serovar of Salmonella enterica (Yopougon) discovered in a Western Whip Snake (Hierophis viridiflavus) from Montecristo Island, Italy: Case report and review. Arch. Microbiol. 2024, 206, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, V.; Mock, R.; Burgkhardt, E.; Junghanns, A.; Ortlieb, F.; Szabo, I.; Marschang, R.; Blindow, I.; Krautwald-Junghanns, M.E. Cloacal aerobic bacterial flora and absence of viruses in free-living slow worms (Anguis fragilis), grass snakes (Natrix natrix) and European Adders (Vipera berus) from Germany. EcoHealth 2014, 11, 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waltenburg, M.A.; Perez, A.; Salah, Z.; Karp, B.E.; Whichard, J.; Tolar, B.; Gollarza, L.; Koski, L.; Blackstock, A.; Basler, C.; et al. Multistate Reptile- and Amphibian-Associated Salmonellosis Outbreaks in Humans, United States, 2009–2018. Zoonoses Public Health 2022, 69, 925–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricard, C.; Mellentin, J.; Ben Abdallah Chabchoub, R.; Kingbede, P.; Heuclin, P.; Ramdame, A.; Bouquet, A.; Couttenier, F.; Hendricx, F. Méningite à Salmonelle chez un nourrisson due à une tortue domestique. Arch. Pédiatr 2015, 22, 605–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafari, M.; Forsberg, J.; Gilcher, R.O.; Smith, J.W.; Crutcher, J.M.; McDermott, M.; Brown, B.R.; George, J.N. Salmonella sepsis caused by a platelet transfusion from a donor with a pet snake. N. Eng. J. Med. 2002, 347, 1075–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otake, S.; Ajiki, J.; Yoshida, M.; Koriyama, T.; Kasai, M. Contact with a snake leading to testicular necrosis due to Salmonella Saintpaul infection. Pediatr. Int. 2021, 63, 119–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruning, A.H.L.; Beld, M.V.D.; Laverge, J.; Welkers, M.R.A.; Kuil, S.D.; Bruisten, S.M.; van Dam, A.P.; Stam, A.J. Reptile-associated Salmonella urinary tract infection: A case report. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2023, 105, 115889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernar, B.; Gande, N.; Bernar, A.; Müller, T.; Schönlaub, J. Case Report: Non-typhoidal Salmonella infections transmitted by reptiles and amphibians. Front. Pediatr. 2023, 11, 1278910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenes-Chacón, H.; Ulloa-Gutierrez, R.; Soriano-Fallas, A.; Camacho-Badilla, K.; Valverde-Muñoz, K.; Ávila-Agüero, M.L. Bacterial Infections Associated with Viperidae Snakebites in Children: A 14-Year Experience at the Hospital Nacional de Niños de Costa Rica. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2019, 100, 1227–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.-H.; Kao, C.-C.; Mao, Y.-C.; Lai, C.-S.; Lai, K.-L.; Lai, C.-H.; Tseng, C.-H.; Huang, Y.-T.; Liu, P.-Y. Shewanella algae and Morganella morganii Coinfection in Cobra-Bite Wounds: A Genomic Analysis. Life 2021, 11, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Surveillance for Outbreaks of Enteric Disease Associated with Animal Contact: Summary for 2017. 2020. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/acoss/pdf/2017-acoss-summary-h.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Paphitis, K.; Reid, A.; Golightly, H.R.; Adams, J.A.; Corbeil, A.; Majury, A.; Murphy, A.; McClinchey, H. Reptile Exposure in Human Salmonellosis Cases and Salmonella Serotypes Isolated from Reptiles, Ontario, Canada, 2015–2022. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2025, 31, 1912–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issenhuth-Jeanjean, S.; Roggentin, P.; Mikoleit, M.; Guibourdenche, M.; de Pinna, E.; Nair, S.; Fields, P.I.; Weill, F.X. Supplement 2008–2010 (no. 48) to the White-Kauffmann-Le Minor scheme. Res. Microbiol. 2014, 165, 526–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Public Health NIH—National Research Institute, Department of Epidemiology and Surveillance of Infectious Diseases. Infectious Diseases and Poisonings in Poland in 2023; National Institute of Public Health: Warsaw, Poland, 2024.

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA); European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). The European Union One Health 2020 Zoonoses Report. EFSA J. 2021, 19, 6971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlak, A.; Małaszczuk, M.; Dróżdż, M.; Bury, S.; Kuczkowski, M.; Morka, K.; Cieniuch, G.; Korzeniowska-Kowal, A.; Wzorek, A.; Korzekwa, K.; et al. Virulence factors of Salmonella spp. isolated from free-living grass snakes Natrix natrix. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2024, 16, e13287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamian, A.; Jones, C.; Lipiński, T.; Korzeniowska-Kowal, A.; Ravenscroft, N. Structure of the sialic acid-containing O-specific polysaccharide from Salmonella enterica serovar Toucra O48 lipopolysaccharide. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002, 267, 3160–3167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlak, A.; Rybka, J.; Dudek, B.; Krzyżewska, E.; Rybka, W.; Kędziora, A.; Klausa, E.; Bugla-Płoskońska, G. Salmonella O48 Serum Resistance is Connected with the Elongation of the Lipopolysaccharide O-Antigen Containing Sialic Acid. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugla-Płoskońska, G.; Rybka, J.; Futoma-Kołoch, B.; Cisowska, A.; Gamian, A.; Doroszkiewicz, W. Sialic acid-containing lipopolysaccharides of Salmonella O48 strains-potential role in camouflage and susceptibility to the bactericidal effect of normal human serum. Microb. Ecol. 2010, 59, 601–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, N.P.; Päuker, B.; Baxter, L.; Gupta, A.; Bunk, B.; Overmann, J.; Diricks, M.; Dreyer, V.; Niemann, S.; Holt, K.E.; et al. EnteroBase in 2025: Exploring the Genomic Epidemiology of Bacterial Pathogens. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D757–D762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Bacterial Priority Pathogens List, 2024: Bacterial Pathogens of Public Health Importance to Guide Research, Development and Strategies to Prevent and Control Antimicrobial Resistance; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Siddiky, N.A.; Sarker, M.S.; Khan, M.S.R.; Begum, R.; Kabir, M.E.; Karim, M.R.; Rahman, M.T.; Mahmud, A.; Samad, M.A. Virulence and Antimicrobial Resistance Profiles of Salmonella enterica Serovars Isolated from Chicken at Wet Markets in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertelloni, F.; Chemaly, M.; Cerri, D.; Gall, F.L.; Ebani, V.V. Salmonella infection in healthy pet reptiles: Bacteriological isolation and study of some pathogenic characters. Acta Microbiol. Immunol. Hung. 2016, 63, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, B.; Ding, X.; Bin, P.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, G. Regulatory Mechanisms between Quorum Sensing and Virulence in Salmonella. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chetri, S.; Bhowmik, D.; Paul, D.; Pandey, P.; Chanda, D.D.; Chakravarty, A.; Bora, D.; Bhattacharjee, A. AcrAB-TolC efflux pump system plays a role in carbapenem non-susceptibility in Escherichia coli. BMC Microbiol. 2019, 19, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Aziz, N.K.; Tartor, Y.H.; Gharieb, R.M.A.; Erfan, A.M.; Khalifa, E.; Said, M.A.; Ammar, A.M.; Samir, M. Extensive Drug-Resistant Salmonella enterica Isolated from Poultry and Humans: Prevalence and Molecular Determinants Behind the Co-resistance to Ciprofloxacin and Tigecycline. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 738784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marti, E.; Variatza, E.; Balcazar, J.L. The role of aquatic ecosystems as reservoirs of antibiotic resistance. Trends Microbiol. 2014, 22, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laborda, P.; Sanz-García, F.; Ochoa-Sánchez, L.E.; Gil-Gil, T.; Hernando-Amado, S.; Martínez, J.L. Wildlife and Antibiotic Resistance. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 873989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcês, A.; Pires, I. European Wild Carnivores and Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria: A Review. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Pan, Q.; He, M. Transmission Dynamics of Resistant Bacteria in a Predator–Prey System. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2015, 2015, 638074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dégi, J.; Herman, V.; Radulov, I.; Morariu, F.; Florea, T.; Imre, K. Surveys on Pet-Reptile-Associated Multi-Drug-Resistant Salmonella spp. in the Timișoara Metropolitan Region—Western Romania. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; He, X.; Chi, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Shuai, J.; Wang, H.; Li, Q.; Du, M. Cytotoxicity and Antimicrobial Resistance of Salmonella enterica Subspecies Isolated from Raised Reptiles in Beijing, China. Animals 2023, 13, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punchihewage-Don, A.J.; Ranaweera, P.N.; Parveen, S. Defense Mechanisms of Salmonella against Antibiotics: A Review. Front. Antibiot. 2024, 3, 1448796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek, B.; Krzyżewska, E.; Kapczyńska, K.; Rybka, J.; Pawlak, A.; Korzekwa, K.; Klausa, E.; Bugla-Płoskońska, G. Proteomic Analysis of Outer Membrane Proteins from Salmonella Enteritidis Strains with Different Sensitivity to Human Serum. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0164069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishio, M.; Okada, N.; Miki, T.; Haneda, T.; Danbara, H. Identification of the outer-membrane protein PagC required for the serum resistance phenotype in Salmonella enterica serovar Choleraesuis. Microbiology 2005, 151, 863–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kintz, E.; Heiss, C.; Black, I.; Donohue, N.; Brown, N.; Davies, M.; Azadi, P.; Baker, S.; Kaye, P.; Van der Woude, M. Salmonella Typhi Lipopolysaccharide O-antigen Modifications Impact on Serum Resistance and Antibody Recognition. Infect. Immun. 2017, 85, 10-1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, J.M.; Gunn, J.S. The O-Antigen Capsule of Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium Facilitates Serum Resistance and Surface Expression of FliC. Infect. Immun. 2015, 83, 3946–3959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukupolvi, S.; Riikonen, P.; Taira, S.; Saarilahti, H.; Rhen, M. Plasmid-mediated serum resistance in Salmonella enterica. Microb Pathogen 1992, 12, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Act of 15 January 2015 on the Protection of Animals Used for Scientific or Educational Purposes. Journal of Laws 2015, Item 266. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20150000266 (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- ISO/TR 6579-3; Microbiology of Food and Animal Feed—Horizontal Method for the Detection, Enumeration and Serotyping of Salmonella—Part 3 Guidelines for Serotyping of Salmonella spp. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; Volume 4, pp. 1–31.

- Grimont, P.; Weill, F.X. Antigenic Formulae of the Salmonella serovars, 9th ed.; WHO Collaborating Centre for Reference and Research on Salmonella: Paris, France, 2007; pp. 1–166. [Google Scholar]

- European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). Breakpoint-Tabelle 15.0. 2025. Available online: https://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Miles, A.A.; Misra, S.S.; Irwin, J.O. The estimation of the bactericidal power of the blood. J. Hyg. 1938, 38, 732–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Bacterial Species 1 | Free-Living Snakes (n = 405) | Kept Snakes (n = 12) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NN | NT | CA | ZL | ED | |

| Achromobacter xylooxidans | 1 | - | 5 | - | - |

| Acinetobacter calcoaceticus | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | - |

| A. courvalinii | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| A. lactuace | - | 2 | - | - | - |

| Advenella inecata | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Aeromonas eucrenophila | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| A. hydrophila | 4 | 3 | - | - | - |

| A. jandaei | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| A. media | - | - | - | 1 | - |

| A. veronii | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - |

| Arthrobacter sp. | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Bacillus sp. | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Brevibacillus sp. | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Carnobacterium sp. | - | 1 | - | - | - |

| C. maltaromaticum | - | 1 | 1 | - | - |

| Citrobacter sp. | - | 1 | - | 2 | - |

| C. braakii | 10 | 5 | 9 | 4 | - |

| C. freundii | 15 | 10 | 3 | 5 | - |

| C. gillenii | 1 | - | - | 1 | - |

| Escherichia coli | 3 | - | 1 | 5 | - |

| Enterobacter cloacae | - | - | - | 1 | - |

| E. ludwugu | - | - | - | 1 | - |

| Enterococcus sp. | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - |

| E. faecalis | 5 | 2 | 12 | 3 | 2 |

| Hafnia alvei | 13 | 2 | 17 | 5 | - |

| Klebsiella aerogenes | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| K. oxytoca | 17 | 5 | 9 | - | - |

| Lactococcus garviae | 2 | - | - | - | - |

| Lelliottia amnigena | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Lysinibacillus fusiformis | - | 1 | - | - | - |

| Micrococcus luteus | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Morganella morgannii | 23 | 4 | 10 | 8 | 2 |

| Plesiomonas shigelloides | - | 2 | - | - | - |

| Proteus sp. | - | 1 | 1 | - | - |

| P. vulgaris | 21 | 6 | 8 | 1 | - |

| P. hauserii | - | 3 | - | - | - |

| Providencia sp. | 3 | - | 1 | - | - |

| P. rettgerii | 1 | 4 | 2 | - | - |

| P. vermicola | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 1 | 7 | 1 | - | 2 |

| P. mendocina | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| Raoultella ornithinolytica | 6 | 2 | 3 | 3 | - |

| R. planticola | 1 | 2 | - | 4 | - |

| R. terrigena | - | - | - | 1 | - |

| Salmonella enterica 2 | 3 | 15 | 6 | 2 | 6 |

| Serratia fonticola | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| S. liquefaciens | 1 | - | 2 | 4 | - |

| S. marcescens | - | - | 7 | - | - |

| Staphylococcus sp. | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| S. sciuri | 1 | 2 | - | - | - |

| S. warneri | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| Vagococcus fluvialis | 10 | 3 | - | - | - |

| n | % | Susceptible | Resistance | Resistant Pattern |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21 | 66% | AMP-AMC-PIP-TZP-TMO-FEP-CFM-CAZ-CZA-CRO-CXM-CF-ERT-IMP-MER-AZE-CIP-LEV-AK-GEN-TOB-TIG-C-SXT-FOS-NF | - | RP1 |

| 8 | 25% | AMP-AMC-PIP-TZP-TMO-FEP-CFM-CAZ-CZA-CRO-CXM-CF-ERT-IMP-MER-AZE-CIP-LEV-AK-GEN-TOB-C-SXT-FOS-NF | TIG | RP2 |

| 1 | 3% | PIP-TZP-TMO-FEP-CFM-CAZ-CZA-CRO-CXM-CF-ERT-IMP-MER-AZE-CIP-LEV-AK-GEN-TOB-TIG-C-SXT-FOS-NF | AMC-AMP | RP3 |

| 1 | 3% | AMP -PIP-TZP-TMO-FEP-CAZ-CZA-CRO-CXM-CF-ERT-IMP-MER-AZE-CIP-LEV-AK-GEN-TOB-TIG-C-SXT-FOS-NF | AMC-CFM | RP4 |

| 1 | 3% | PIP-TZP-TMO-FEP-CFM-CAZ-CZA-CRO-ERT-IMP-MER-AZE-CIP-LEV-AK-GEN-TOB-C-SXT-NF | AMC-AMP CXM-CF-TIG-FOS | RP5 |

| Phenotype | Parameter | T1 | T2 | T3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitive(n = 5) | Mean CFU/mL ± SD | 3.94 × 106 ± 5.48 × 106 | 1.18 × 106 ± 1.13 × 106 | 7.28 × 105 ± 4.33 × 105 |

| Median CFU/mL | 1.14 × 106 | 9.56 × 105 | 7.86 × 105 | |

| Mean Survival Rate (%) | 63.45 ± 84.11% | 19.81 ± 20.56% | 12.31 ± 10.09% | |

| Mean number of Estimated divisions | −3.42 ± 2.27 | −3.58 ± 1.51 | −3.42 ± 2.27 | |

| Intermediate (n = 1) | CFU/mL ± SD | 2.70 × 106 | 1.82 × 106 | 2.35 × 106 |

| Survival Rate (%) | 77.14% | 51.90% | 67.14% | |

| Number of Estimated divisions | −0.37 | −0.95 | −0.57 | |

| Resistant (n = 56) | Mean CFU/mL ± SD | 2.55 × 107 ± 1.80 × 107 | 7.37 × 107 ± 5.97 × 107 | 1.47 × 108 ± 1.02 × 108 |

| Median CFU/mL | 2.19 × 107 | 5.56 × 107 | 1.33 × 108 | |

| Mean Survival Rate (%) | >100% | >1000% | >1500% | |

| Number of Estimated divisions | 1.68 ± 0.77 | 3.11 ± 0.97 | 4.15 ± 0.97 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Małaszczuk, M.; Pawlak, A.; Bury, S.; Kolanek, A.; Błach, K.; Zając, B.; Wzorek, A.; Cieniuch-Speruda, G.; Korzeniowska-Kowal, A.; Gamian, A.; et al. From Bacterial Diversity to Zoonotic Risk: Characterization of Snake-Associated Salmonella Isolated in Poland with a Focus on Rare O-Ag of LPS, Antimicrobial Resistance and Survival in Human Serum. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12018. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412018

Małaszczuk M, Pawlak A, Bury S, Kolanek A, Błach K, Zając B, Wzorek A, Cieniuch-Speruda G, Korzeniowska-Kowal A, Gamian A, et al. From Bacterial Diversity to Zoonotic Risk: Characterization of Snake-Associated Salmonella Isolated in Poland with a Focus on Rare O-Ag of LPS, Antimicrobial Resistance and Survival in Human Serum. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12018. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412018

Chicago/Turabian StyleMałaszczuk, Michał, Aleksandra Pawlak, Stanisław Bury, Aleksandra Kolanek, Klaudia Błach, Bartłomiej Zając, Anna Wzorek, Gabriela Cieniuch-Speruda, Agnieszka Korzeniowska-Kowal, Andrzej Gamian, and et al. 2025. "From Bacterial Diversity to Zoonotic Risk: Characterization of Snake-Associated Salmonella Isolated in Poland with a Focus on Rare O-Ag of LPS, Antimicrobial Resistance and Survival in Human Serum" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12018. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412018

APA StyleMałaszczuk, M., Pawlak, A., Bury, S., Kolanek, A., Błach, K., Zając, B., Wzorek, A., Cieniuch-Speruda, G., Korzeniowska-Kowal, A., Gamian, A., & Bugla-Płoskońska, G. (2025). From Bacterial Diversity to Zoonotic Risk: Characterization of Snake-Associated Salmonella Isolated in Poland with a Focus on Rare O-Ag of LPS, Antimicrobial Resistance and Survival in Human Serum. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12018. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412018