Photobiomodulation-Driven Tenogenic Differentiation of MSCs in Hydrogel Culture

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

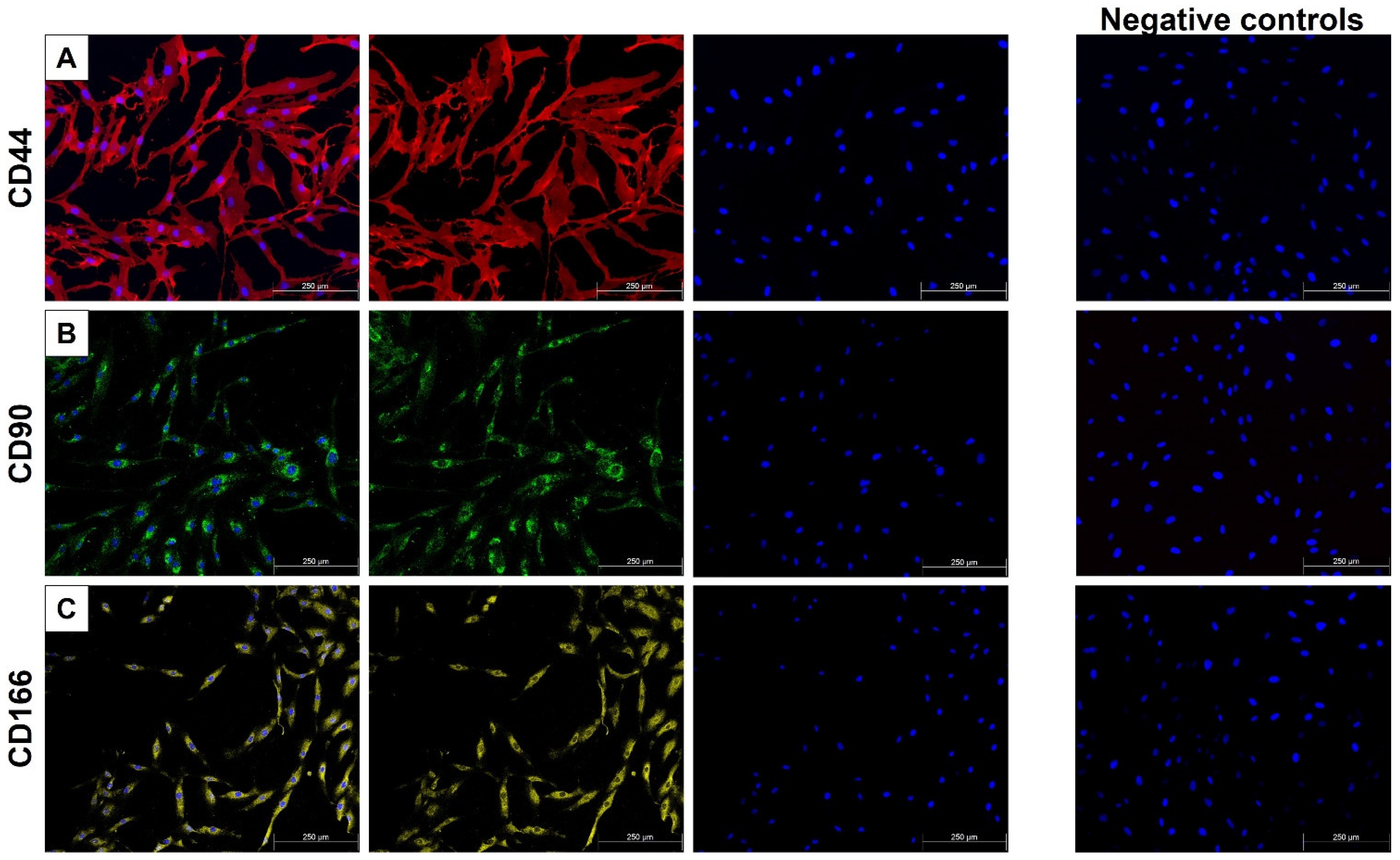

2.1. MSC Characterization

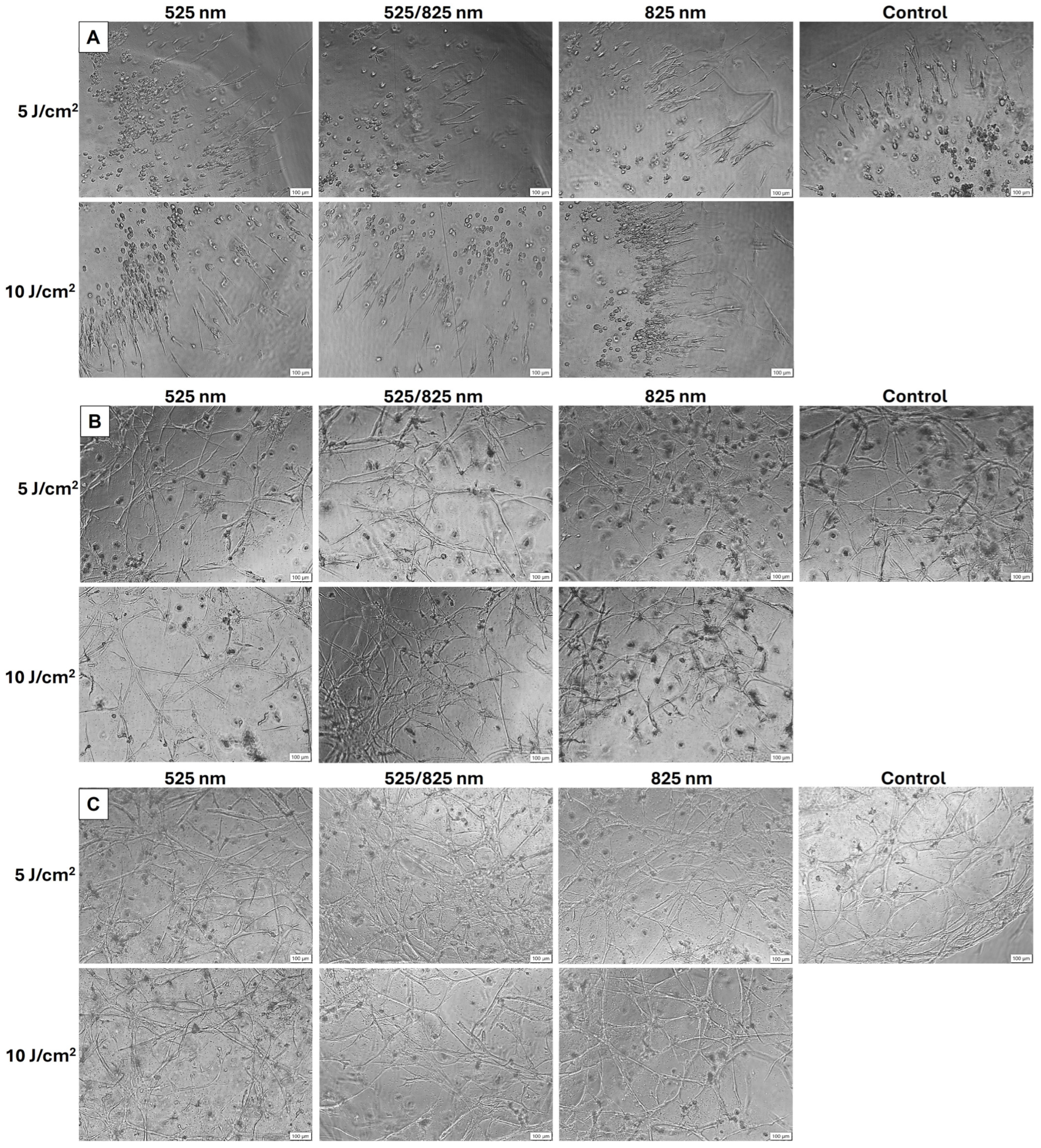

2.2. Morphology

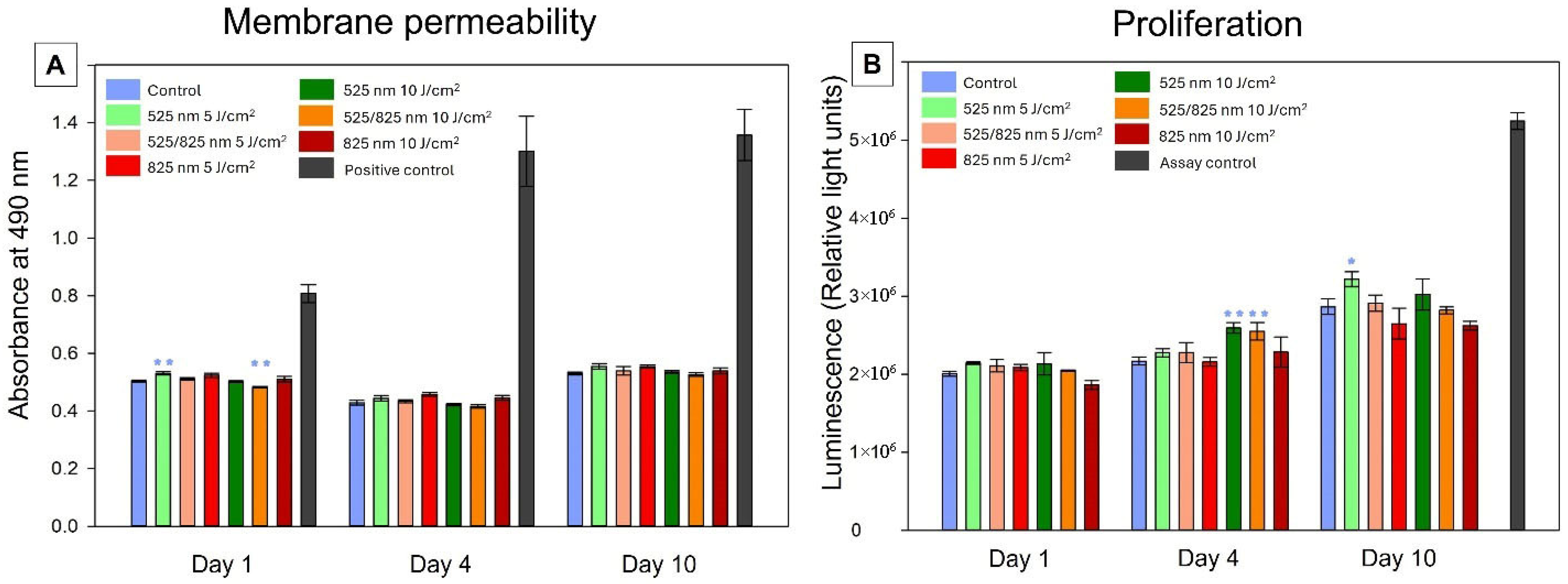

2.3. Cellular Health

2.3.1. Membrane Permeability

2.3.2. Proliferation

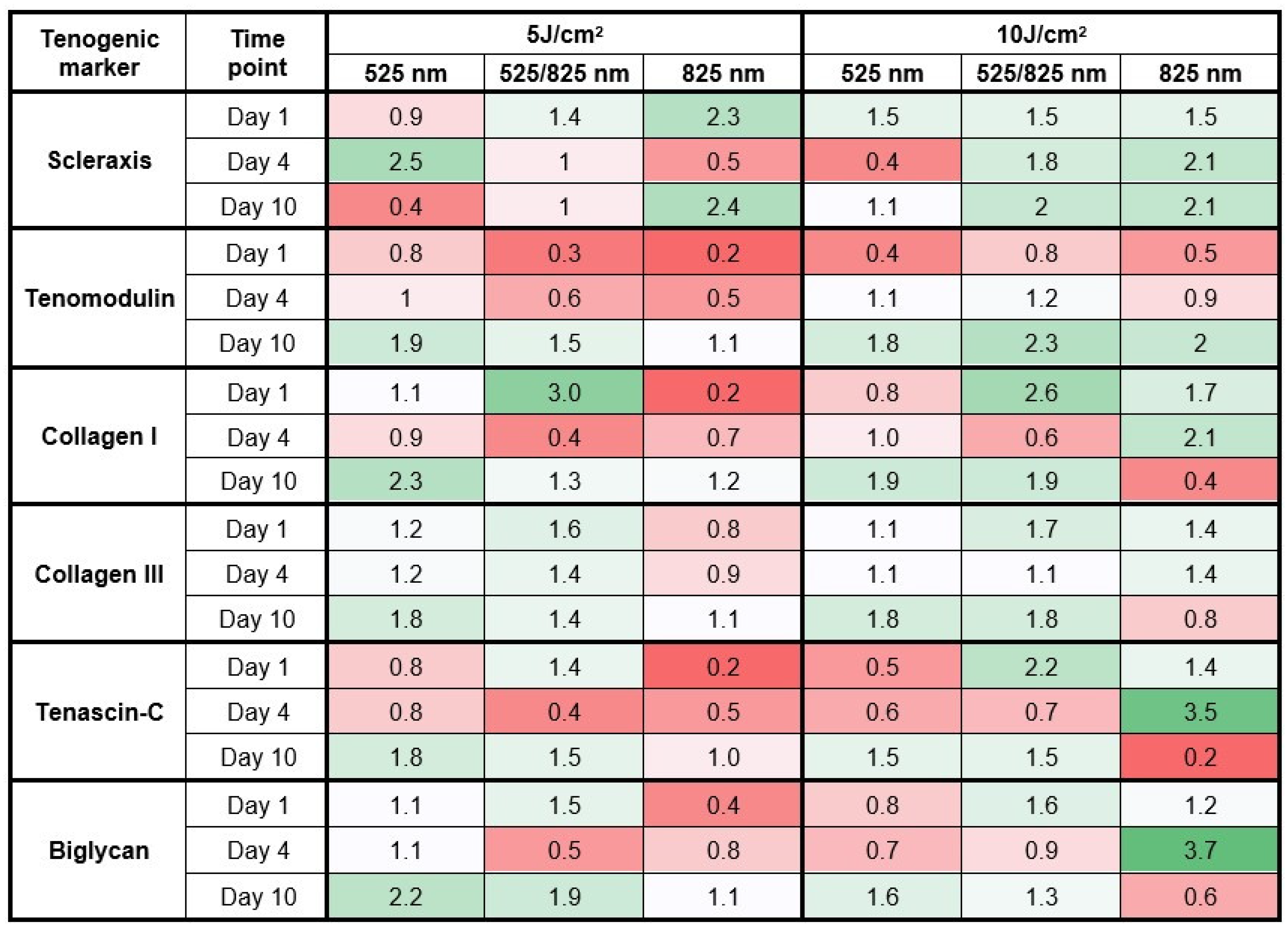

2.4. Gene Expression

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Hydrogel Preparation and Cell Culture

4.2. Tenogenic Differentiation

4.3. Photobiomodulation (PBM)

| Laser Parameters | Green (G) | Near Infra-Red (NIR) |

|---|---|---|

| Light Source | Diode Laser | Diode Laser |

| Wavelength (nm) | 525 | 825 |

| Power Output (mW) | 473 | 190 |

| Power Density (mW/cm2) | 52.10 | 20.93 |

| Emission | Continuous Wave | Continuous Wave |

| Fluence (J/cm2) | 5/10 | 5/10 |

| Time of irradiation (s) | 96/192 | 240/480 |

4.4. Cellular Characterization Using Immunofluorescence

4.5. Inverted Light Microscopy

4.6. Recovery Solution

4.7. Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH)

4.8. Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP)

4.9. Reverse Transcription Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR)

4.10. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| µg | Microgram |

| µg/mL–µg | Microgram per milliliter |

| ADMSCs | Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells |

| ATCC | American Type Culture Collection |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| BGN | Biglycan |

| CD | Cluster of differentiation |

| Col I | Collagen I |

| Col III | Collagen III |

| CTGF | Connective tissue growth factor |

| DAPI | 4′, 6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum |

| iADMSCs | Immortalized adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells |

| J/cm2 | Joules per square centimeter |

| LDH | Lactate dehydrogenase |

| MSCs | Mesenchymal stem cells |

| ng/mL | Nanograms per milliliter |

| NIR | Near-infrared |

| nm | Nanometer |

| PBM | Photobiomodulation |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| PFA | Paraformaldehyde |

| Scx | Scleraxis |

| TGF-β1 | Transforming growth factor β1 |

| TNC | Tenascin-C |

| Tnmd | Tenomodulin |

References

- Tempfer, H.; Traweger, A. Tendon vasculature in health and disease. Front. Physiol. 2015, 6, 163621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lui, P.P.Y. Stem cell technology for tendon regeneration: Current status, challenges, and future research directions. Stem Cells Cloning Adv. Appl. 2015, ume 8, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffulli, N.; Sharma, P.; Luscombe, K.L. Achilles tendinopathy: Aetiology and management. J. R. Soc. Med. 2004, 97, 472–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Rakhmatullina, A.R.; Mingaleeva, R.N.; Gafurbaeva, D.U.; Glazunova, O.N.; Sagdeeva, A.R.; Bulatov, E.R.; Rizvanov, A.A.; Miftakhova, R.R. Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) immortalization by modulation of hTERT and TP53 expression levels. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Song, K.; Qu, X.; Wang, H.; Zhu, H.; Xu, X.; Zhang, M.; Tang, Y.; Yang, X. hTERT gene immortalized human adipose-derived stem cells and its multiple differentiations: A preliminary investigation. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2013, 169, 1546–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, S.; Vimalraj, S.; Lakshmanan, G.; Jindal, A.; Sundaramurthi, D.; Bhattacharya, J. Chitosan-based biocomposite scaffolds and hydrogels for bone tissue regeneration. In Marine-Derived Biomaterials for Tissue Engineering Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 413–442. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.-Y.; Xu, P.; Luo, Q.; Song, G.-B. Proliferation and tenogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in a porous collagen sponge scaffold. World J. Stem Cells 2021, 13, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melzer, M.; Niebert, S.; Heimann, M.; Ullm, F.; Pompe, T.; Scheiner-Bobis, G.; Burk, J. Differential Smad2/3 linker phosphorylation is a crosstalk mechanism of Rho/ROCK and canonical TGF-β3 signaling in tenogenic differentiation. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 10393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jindal, A.; Mondal, T.; Bhattacharya, J. An in vitro evaluation of zinc silicate fortified chitosan scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 4252–4262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govoni, M.; Berardi, A.C.; Muscari, C.; Campardelli, R.; Bonafè, F.; Guarnieri, C.; Reverchon, E.; Giordano, E.; Maffulli, N.; Della Porta, G. An engineered multiphase three-dimensional microenvironment to ensure the controlled delivery of cyclic strain and human growth differentiation factor 5 for the tenogenic commitment of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Tissue Eng. Part A 2017, 23, 811–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, D.; Sharma, S.; Screen, H.R.; Bryant, S.J. Effects of cell adhesion motif, fiber stiffness, and cyclic strain on tenocyte gene expression in a tendon mimetic fiber composite hydrogel. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 499, 642–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braccini, S.; Tacchini, C.; Chiellini, F.; Puppi, D. Polymeric hydrogels for in vitro 3D ovarian cancer modeling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashinchian, O.; Hong, X.; Michaud, J.; Migliavacca, E.; Lefebvre, G.; Boss, C.; De Franceschi, F.; Le Moal, E.; Collerette-Tremblay, J.; Isern, J. In vivo transcriptomic profiling using cell encapsulation identifies effector pathways of systemic aging. eLife 2022, 11, e57393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, V. How some labs put more bio into biomaterials. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 365–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikmulina, P.Y.; Kosheleva, N.V.; Shpichka, A.I.; Efremov, Y.M.; Yusupov, V.I.; Timashev, P.S.; Rochev, Y.A. Beyond 2D: Effects of photobiomodulation in 3D tissue-like systems. J. Biomed. Opt. 2020, 25, 048001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bikmulina, P.; Kosheleva, N.; Shpichka, A.; Yusupov, V.; Gogvadze, V.; Rochev, Y.; Timashev, P. Photobiomodulation in 3D tissue engineering. J. Biomed. Opt. 2022, 27, 090901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, M.M. Photobiomodulation therapy weaknesses. Lasers Dent. Sci. 2022, 6, 131–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dompe, C.; Moncrieff, L.; Matys, J.; Grzech-Leśniak, K.; Kocherova, I.; Bryja, A.; Bruska, M.; Dominiak, M.; Mozdziak, P.; Skiba, T.H.I. Photobiomodulation—Underlying mechanism and clinical applications. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roets, B.; Abrahamse, H.; Crous, A. The Application of Photobiomodulation on Mesenchymal Stem Cells and its Potential Use for Tenocyte Differentiation. Curr. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 20, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Almeida, R.; Calejo, I.; Gomes, M.E. Mesenchymal stem cells empowering tendon regenerative therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.-Y.; Wang, Y.; Lyu, P.; Hamblin, M.R. Photobiomodulation (blue and green light) encourages osteoblastic-differentiation of human adipose-derived stem cells: Role of intracellular calcium and light-gated ion channels. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 33719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhu, Y.; Pei, Q.; Deng, Y.; Ni, T. The 532 nm Laser Treatment Promotes the Proliferation of Tendon-Derived Stem Cells and Upregulates Nr4a1 to Stimulate Tenogenic Differentiation. Photobiomodul. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2022, 40, 543–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, S.; Hamblin, M.R.; Abrahamse, H. Effect of red light and near infrared laser on the generation of reactive oxygen species in primary dermal fibroblasts. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2018, 188, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.H. Effect of photobiomodulation on the mesenchymal stem cells. Med. Lasers Eng. Basic Res. Clin. Appl. 2020, 9, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, D.; Crous, A.; Abrahamse, H. Synergistic Effects of Photobiomodulation and Differentiation Inducers on Osteogenic Differentiation of Adipose-Derived Stem Cells in Three-Dimensional Culture. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominici, M.; Le Blanc, K.; Mueller, I.; Slaper-Cortenbach, I.; Marini, F.; Krause, D.; Deans, R.; Keating, A.; Prockop, D.; Horwitz, E. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy 2006, 8, 315–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Silva, D.; Crous, A.; Abrahamse, H. Enhancing osteogenic differentiation in adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells with Near Infra-Red and Green Photobiomodulation. Regen. Ther. 2023, 24, 602–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen van Rensburg, M.; Crous, A.; Abrahamse, H. Promoting Immortalized Adipose-Derived Stem Cell Transdifferentiation and Proliferation into Neuronal-Like Cells through Consecutive 525 nm and 825 nm Photobiomodulation. Stem Cells Int. 2022, 2022, 2744789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohand-Kaci, F.; Assoul, N.; Martelly, I.; Allaire, E.; Zidi, M. Optimized hyaluronic acid–hydrogel design and culture conditions for preservation of mesenchymal stem cell properties. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods 2013, 19, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latifi, N.; Asgari, M.; Vali, H.; Mongeau, L. A tissue-mimetic nano-fibrillar hybrid injectable hydrogel for potential soft tissue engineering applications. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szkolar, L.; Guilbaud, J.B.; Miller, A.F.; Gough, J.E.; Saiani, A. Enzymatically triggered peptide hydrogels for 3D cell encapsulation and culture. J. Pept. Sci. 2014, 20, 578–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-H.; Li, D.-L.; Chuang, A.D.-C.; Dash, B.S.; Chen, J.-P. Tension stimulation of tenocytes in aligned hyaluronic acid/platelet-rich plasma-polycaprolactone core-sheath nanofiber membrane scaffold for tendon tissue engineering. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, A.; Galvez, M.G.; Bachmann, M.; Legrand, A.; McGoldrick, R.; Lovell, A.; Jacobs, M.; Crowe, C.; Umansky, E.; Chang, J. Tendon regeneration with tendon hydrogel–based cell delivery: A comparison of fibroblasts and adipose-derived stem cells. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2016, 138, 617–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.E.; Gemeinhart, E.J.; Gemeinhart, R.A. Cellular alignment by grafted adhesion peptide surface density gradients. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A Off. J. Soc. Biomater. Jpn. Soc. Biomater. Aust. Soc. Biomater. Korean Soc. Biomater. 2004, 71, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishore, V.; Bullock, W.; Sun, X.; Van Dyke, W.S.; Akkus, O. Tenogenic differentiation of human MSCs induced by the topography of electrochemically aligned collagen threads. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 2137–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.-Y.; Wang, Y.; Lyu, P.; Hamblin, M.R. Red (660 nm) or near-infrared (810 nm) photobiomodulation stimulates, while blue (415 nm), green (540 nm) light inhibits proliferation in human adipose-derived stem cells. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 7781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victor, E.C.; Goulardins, J.; Cardoso, V.O.; Silva, R.E.C.; Brugnera, A.; Bussadori, S.K.; Fernandes, K.P.S.; Mesquita-Ferrari, R.A. Effect of photobiomodulation in lipopolysaccharide-treated myoblasts. Photobiomodul. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2021, 39, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, D.; Crous, A.; Abrahamse, H. Photobiomodulation Dose–Response on Adipose-Derived Stem Cell Osteogenesis in 3D Cultures. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, D.; Enright, H.A.; Peters, S.K.; Moya, M.L.; Soscia, D.A.; Cadena, J.; Alvarado, J.A.; Kulp, K.S.; Wheeler, E.K.; Fischer, N.O. Optimizing cell encapsulation condition in ECM-Collagen I hydrogels to support 3D neuronal cultures. J. Neurosci. Methods 2020, 329, 108460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roets, B.; Abrahamse, H.; Crous, A. Three-Dimensional Cell Culture of Adipose-Derived Stem Cells in a Hydrogel with Photobiomodulation Augmentation. J. Vis. Exp. Jove 2024, e66616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, R.; Broglie, J.J.; Adcock, A.F.; Yang, L. Three-dimensional cell culture systems and their applications in drug discovery and cell-based biosensors. Assay Drug Dev. Technol. 2014, 12, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, G.; Adams, K.W. The Cell: A Molecular Approach; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.; Bility, M.; Billin, A.; Willson, T.; Gonzalez, F.; Peters, J. PPARβ/δ selectively induces differentiation and inhibits cell proliferation. Cell Death Differ. 2006, 13, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malthiery, E.; Chouaib, B.; Hernandez-Lopez, A.M.; Martin, M.; Gergely, C.; Torres, J.-H.; Cuisinier, F.J.; Collart-Dutilleul, P.-Y. Effects of green light photobiomodulation on Dental Pulp Stem Cells: Enhanced proliferation and improved wound healing by cytoskeleton reorganization and cell softening. Lasers Med. Sci. 2021, 36, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamimi, R.; Mahmoodi, N.M.; Samadikhah, H.R.; Tackallou, S.H.; Benisi, S.Z.; Boroujeni, M.E. Anti-inflammatory effect of green photobiomodulation in human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Lasers Med. Sci. 2022, 37, 3693–3703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crous, A.; van Rensburg, M.J.; Abrahamse, H. Single and consecutive application of near-infrared and green irradiation modulates adipose derived stem cell proliferation and affect differentiation factors. Biochimie 2022, 196, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merigo, E.; Bouvet-Gerbettaz, S.; Boukhechba, F.; Rocca, J.-P.; Fornaini, C.; Rochet, N. Green laser light irradiation enhances differentiation and matrix mineralization of osteogenic cells. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2016, 155, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamblin, M.R. Mechanisms and applications of the anti-inflammatory effects of photobiomodulation. AIMS Biophys. 2017, 4, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.J.; Clegg, P.D.; Comerford, E.J.; Canty-Laird, E.G. A comparison of the stem cell characteristics of murine tenocytes and tendon-derived stem cells. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2018, 19, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, C.H.; Lim, H.-J.; Yoon, K.S. Characterization of tendon-specific markers in various human tissues, tenocytes and mesenchymal stem cells. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2019, 16, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.K.; Kim, J.H.; Park, G.T.; Woo, S.H.; Cho, M.; Kang, S.W. Efficacy of Light-Emitting Diode-Mediated Photobiomodulation in Tendon Healing in a Murine Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, Y.; Ye, X.; Weng, Y.; Tong, Z.; Ren, Q. Effects of the 532-nm and 1064-nm Q-switched Nd: YAG lasers on collagen turnover of cultured human skin fibroblasts: A comparative study. Lasers Med. Sci. 2010, 25, 719–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, A.C.D.F.; Albertini, R.; Serra, A.J.; da Silva, E.A.P.; de Oliveira, V.L.C.; Silva, L.M.; Leal-Junior, E.C.P.; de Carvalho, P.D.T.C. Photobiomodulation therapy on collagen type I and III, vascular endothelial growth factor, and metalloproteinase in experimentally induced tendinopathy in aged rats. Lasers Med. Sci. 2016, 31, 1915–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomiero, C.; Bertolutti, G.; Martinello, T.; Van Bruaene, N.; Broeckx, S.Y.; Patruno, M.; Spaas, J.H. Tenogenic induction of equine mesenchymal stem cells by means of growth factors and low-level laser technology. Vet. Res. Commun. 2016, 40, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alimohamad, H.; Habijanac, T.; Larjava, H.; Häkkinen, L. Colocalization of the collagen-binding proteoglycans decorin, biglycan, fibromodulin and lumican with different cells in human gingiva. J. Periodontal Res. 2005, 40, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chellini, F.; Tani, A.; Zecchi-Orlandini, S.; Giannelli, M.; Sassoli, C. In vitro evidences of different fibroblast morpho-functional responses to red, near-infrared and violet-blue photobiomodulation: Clues for addressing wound healing. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutolf, M.P.; Lauer-Fields, J.L.; Schmoekel, H.G.; Metters, A.T.; Weber, F.E.; Fields, G.B.; Hubbell, J.A. Synthetic matrix metalloproteinase-sensitive hydrogels for the conduction of tissue regeneration: Engineering cell-invasion characteristics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 5413–5418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Guo, J.; Wu, T.-Y.; Chen, X.; Xu, L.-L.; Lin, S.-E.; Sun, Y.-X.; Chan, K.-M.; Ouyang, H.; Li, G. Stepwise differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells augments tendon-like tissue formation and defect repair in vivo. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2016, 5, 1106–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EN 60825-1:2007; Safety of Laser Products—Part 1: Equipment Classification and Requirements. National Laser Centre: Pretoria, South Africa, 2007.

- Gonçalves, A.; Rotherham, M.; Markides, H.; Rodrigues, M.; Reis, R.; Gomes, M.; El Haj, A. Triggering the activation of Activin A type II receptor in human adipose stem cells towards tenogenic commitment using mechanomagnetic stimulation. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2018, 14, 1149–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younesi Soltani, F.; Javanshir, S.; Dowlati, G.; Parham, A.; Naderi-Meshkin, H. Differentiation of human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells toward tenocyte by platelet-derived growth factor-BB and growth differentiation factor-6. Cell Tissue Bank. 2021, 23, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czaplewski, S.K.; Tsai, T.-L.; Duenwald-Kuehl, S.E.; Vanderby, R., Jr.; Li, W.-J. Tenogenic differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived mesenchymal stem cells dictated by properties of braided submicron fibrous scaffolds. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 6907–6917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, C.; Burggraf, M.; Kreja, L.; Ignatius, A.; Schieker, M.; Docheva, D. Mechanical stimulation of human tendon stem/progenitor cells results in upregulation of matrix proteins, integrins and MMPs, and activation of p38 and ERK1/2 kinases. BMC Mol. Biol. 2015, 16, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanco, D.; Caprara, C.; Ciardelli, G.; Mariotta, L.; Gola, M.; Minonzio, G.; Soldati, G. Tenogenic differentiation protocol in xenogenic-free media enhances tendon-related marker expression in ASCs. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0212192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Component | Volume |

|---|---|

| Water | 2 µL |

| Buffer | 0.8 µL |

| Dextran | 1.7 µL |

| RGD peptide | 1.3 µL |

| Cell suspension | 1.7 µL |

| Cross linker | 2.5 µL |

| Total | 10 µL |

| Experimental Group | PBM Treatment | Growth Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Control | None | Tenogenic differentiation |

| 525 nm | 525 nm; 5 J/cm2 | |

| 525 nm; 10 J/cm2 | ||

| 825 nm | 825 nm; 5 J/cm2 | |

| 825 nm; 10 J/cm2 | ||

| 525/825 nm (consecutive) | 525/825 nm; 5 J/cm2 | |

| 525/825 nm; 10 J/cm2 |

| Target Gene | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer | Annealing Temperature | Amplicon Size | Accession Number | Reference to Accession Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scleraxis (Scx) | AGAACACCCAGCCCAAAC | CCACCTCCTAACTGCGAATC | 55 °C | 102 | NM_001080514.3 | [60] |

| Tenomodulin (Tnmd) | GATCCTGTGACCAGAACTGAAA | CGAAGTAGATGCCAGTGTATCC | 55 °C | 100 | NM_022144.3 | [61] |

| Collagen I alpha 1 chain (Col 1A1) | CCTGTCTGCTTCCTGTAAACTC | GTTCAGTTTGGGTTGCTTGTC | 55 °C | 101 | NM_000088.3 | [62] |

| Collagen 3 alpha 1 chain (Col 3A1) | GAGTCCATGGATGGTGGTTT | CTGGAGAGAAGTCGAAGGAATG | 55 °C | 98 | NM_000090.3 | |

| Biglycan (BGN) | CTCGTCCTGGTGAACAACAA | CAGGTGGTTCTTGGAGATGTAG | 55 °C | 96 | NM_001711.6 | [63] |

| Tenascin-C (TNC) | GATGCCAAGACTCGCTACAA | GTCAAAGGTGGAGAAGGATCTG | 55 °C | 99 | NM_002160.4 | [64] |

| GAPDH | CAAGAGCACAAGAGGAAGAGAG | CTACATGGCAACTGTGAGGAG | 55 °C | 102 | NM_002046.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roets, B.; Abrahamse, H.; Crous, A. Photobiomodulation-Driven Tenogenic Differentiation of MSCs in Hydrogel Culture. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11965. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411965

Roets B, Abrahamse H, Crous A. Photobiomodulation-Driven Tenogenic Differentiation of MSCs in Hydrogel Culture. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11965. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411965

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoets, Brendon, Heidi Abrahamse, and Anine Crous. 2025. "Photobiomodulation-Driven Tenogenic Differentiation of MSCs in Hydrogel Culture" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11965. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411965

APA StyleRoets, B., Abrahamse, H., & Crous, A. (2025). Photobiomodulation-Driven Tenogenic Differentiation of MSCs in Hydrogel Culture. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11965. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411965