Structural and Proteomic Analysis of the Mouse Cathepsin B-DARPin 4m3 Complex Reveals Species-Specific Binding Determinants

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

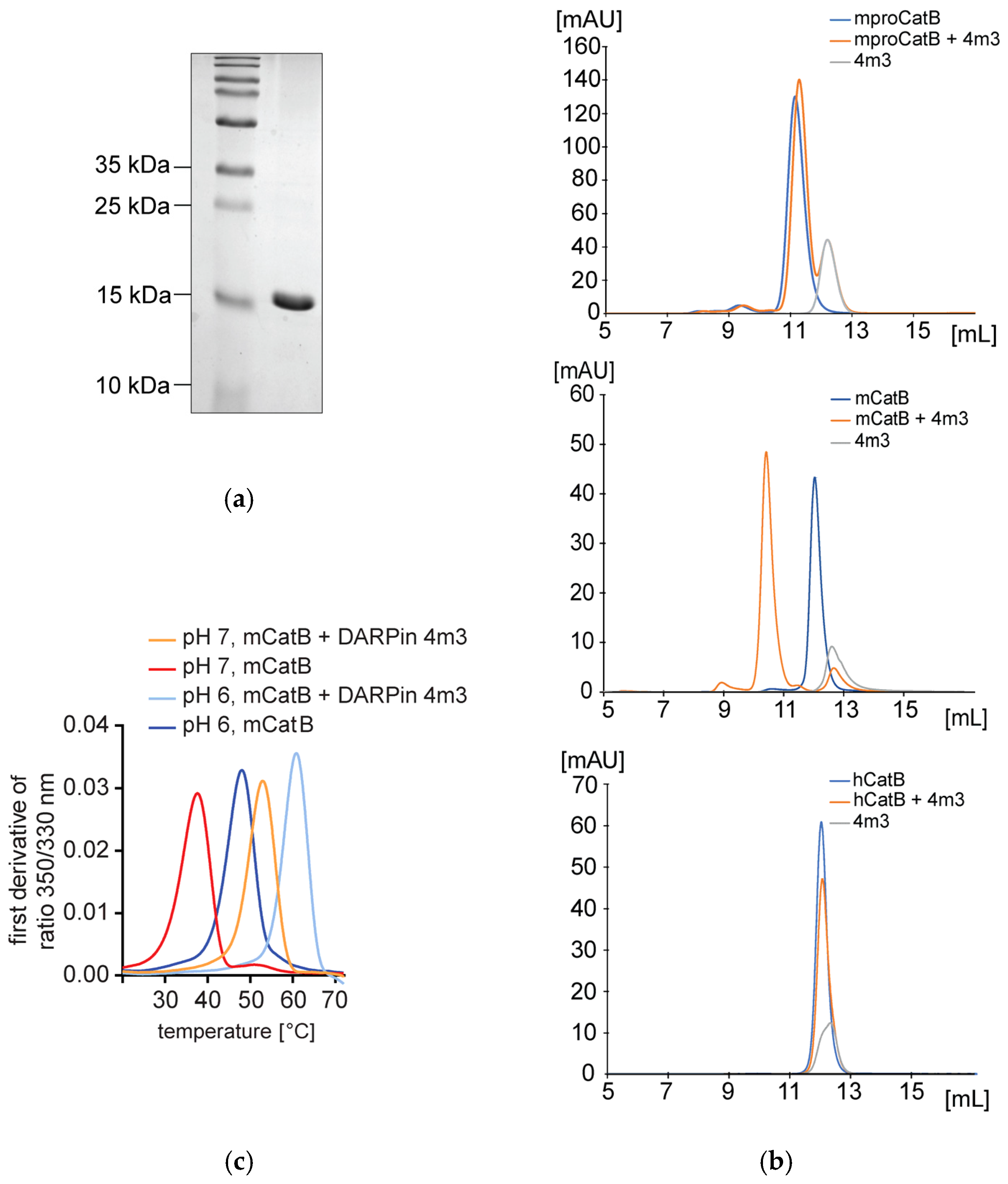

2.1. DARPin 4m3 Selectively Binds Mouse and Not Human Cathepsin B

2.2. Binding Affinity and Mode of Inhibition of mCatB by DARPin 4m3

2.3. Crystal Structure of the Mouse Cathepsin B–DARPin 4m3 Complex

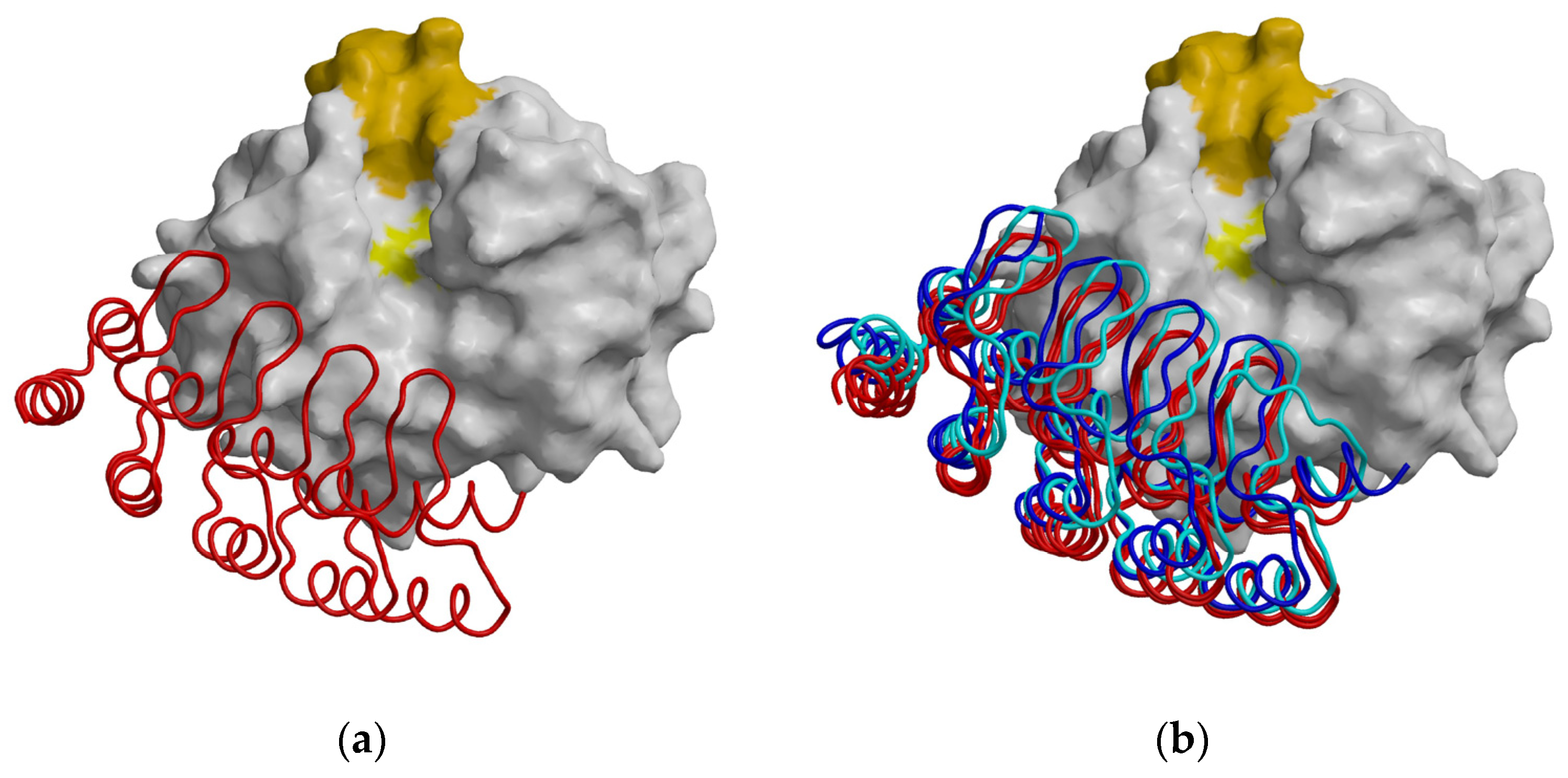

2.4. Structural Comparison of the Cathepsins B, DARPins and Their Complexes

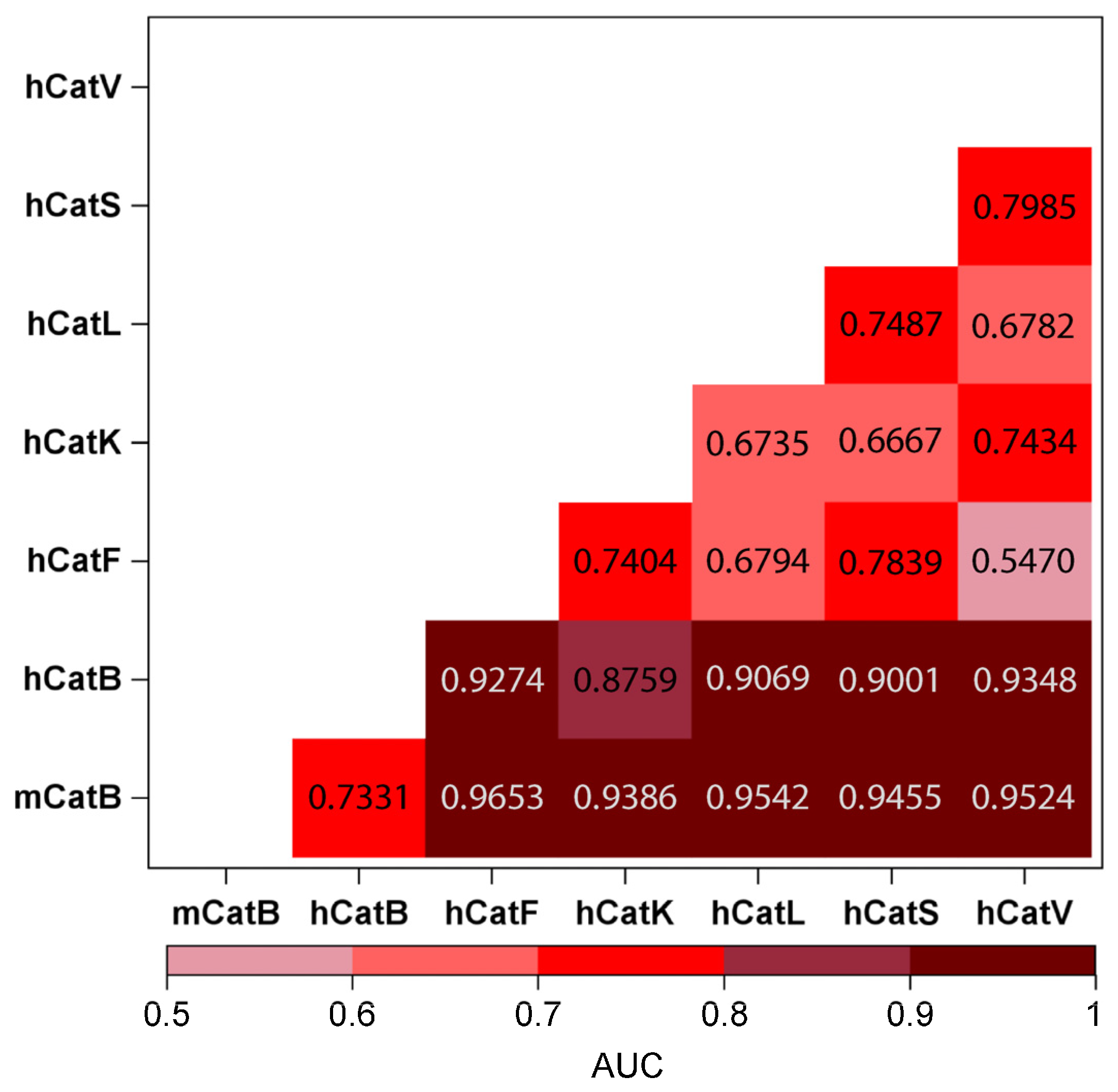

2.5. Substrates as Indicators of Differences Between Mouse and Human CatB

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Expression and Purification of Recombinant Proteins

4.2. Inhibition Assay

4.3. Nano-Differential Fluorimetry Analysis

4.4. Surface Plasmon Resonance

4.5. Analytical Size-Exclusion Chromatography

4.6. Cellular Thermal Shift Assay

4.7. Structure Determination

4.8. Data Sets of Human Cathepsins K, V, L, S, F, and mCatB Substrates

4.9. Evaluation of Substrate Differences Between mCatB and Human Cathepsins B, K, V, L, S, and F Using Support Vector Machine Algorithm and Clustering

- Regularization parameter C = [0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1]

- Kernel = [‘linear’, ‘rbf’, ‘poly’, ‘sigmoid’]

- Gamma = [‘scale’, ‘auto’]

- Class weight = [‘balanced’, ‘none’]

- Jackknife fraction = [0.10, 0.25]

4.10. Docking

4.11. Data Availability

4.12. Alignment and Comparison of CatB Sequences

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| (m/h)Cat | (mouse/human) cathepsin |

| DARPin | designed ankyrin repeat proteins |

| nano-DSF | nano-differential scanning fluorimetry |

| SPR | surface plasmon resonance |

| CETSA | cellular thermal shift assay |

| AUC | area under curve |

| AMC | 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin |

| ROC | receiver operating characteristic |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Figures

Appendix A.2. Tables

| Data collection and refinement statistics. | |||||

| PDB entry | |||||

| Data collection | |||||

| Space group | P21 21 21 | ||||

| Cell dimensions | |||||

| a, b, c (Å) | 52.643, 109.921, 142.637 | ||||

| 90.00, 90.00, 90.00 | |||||

| Resolution (Å) | 49.387–1.690 (1.67) | ||||

| Rmeans | 6.0 % (82.6 %) | ||||

| I/бꟾ | 22.11 % (3.11 %) | ||||

| Completeness (%) | 99.9 % (99.9 %) | ||||

| Redundancy | 12.44 (12.54) | ||||

| Refinement | |||||

| Resolution (Å) | 49.387–1.67 | ||||

| No. reflections | 96,907 | ||||

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.1931/0.2177 | ||||

| No. atoms | 14,655 | ||||

| Protein | 3741–3750 | ||||

| Inhibitor | 2262 | ||||

| Water | 2640 | ||||

| B-factors | 37.79 | ||||

| Protein | 36.77 | ||||

| Inhibitor | 35.08 | ||||

| Water | 49.34 | Molecule 1 | Molecule 2 | RMSD (Å) | Sequence Identity (%) |

| R.m.s. deviations | Mouse cathepsin B | Human cathepsin B | 0.70 | 83.1 | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.014 | Mouse cathepsin B-molecule A | Mouse cathepsin B-molecule B | 0.38 | 100 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.527 | Mouse cathepsin B-molecule A and DARPin B | Mouse cathepsin B-molecule B and DARPin B2 | 0.65 | 100 |

| Data were collected from one crystal. Hydrogen atoms were excluded from the calculations. Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell. | DARPin B | DARPin B2 | 0.39 | 100 | |

| (a) | (b) | ||||

| Protein 3D Structure 1 | Protein 3D Structure 2 | Alignment Length | RMSD | Sequence Identities (%) | Number of Different Residues | Number of Homologs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mCatB | hCatB | 253 | 0.68 | 83.0 | 23 | 20 |

| 4m3 | 81 | 158 | 0.65 | 86.8 | 14 | 6 |

| 4m3 | 8h6 | 158 | 0.85 | 88.1 | 7 | 11 |

| 8h6 | 81 | 159 | 0.68 | 89.3 | 6 | 3 |

| No | Cathepsin 1 | Cathepsin 2 | P3–P4′ (AUC) | P4–P4′ (AUC) | P15–P15′ (AUC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | mCatB | hCatB | 0.7331 | 0.7922 | 0.9668 |

| 2 | mCatB | hCatK | 0.9386 | 0.9310 | 0.9722 |

| 3 | mCatB | hCatV | 0.9524 | 0.9616 | 0.9743 |

| 4 | mCatB | hCatL | 0.9542 | 0.9454 | 0.9754 |

| 5 | mCatB | hCatS | 0.9455 | 0.9524 | 0.9788 |

| 6 | mCatB | hCatF | 0.9653 | 0.9518 | 0.9745 |

| 7 | hCatF | hCatB | 0.9274 | 0.9360 | 0.9384 |

| 8 | hCatK | hCatB | 0.8759 | 0.9270 | 0.9042 |

| 9 | hCatV | hCatB | 0.9348 | 0.8291 | 0.9573 |

| 10 | hCatL | hCatB | 0.9069 | 0.8980 | 0.8884 |

| 11 | hCatS | hCatB | 0.9001 | 0.9192 | 0.9105 |

| 12 | hCatF | hCatK | 0.7404 | 0.7324 | 0.7744 |

| 13 | hCatF | hCatL | 0.6794 | 0.7406 | 0.7423 |

| 14 | hCatK | hCatL | 0.6735 | 0.7338 | 0.7325 |

| 15 | hCatK | hCatV | 0.7434 | 0.7759 | 0.9267 |

| 16 | hCatK | hCatS | 0.6667 | 0.7920 | 0.8163 |

| 17 | hCatF | hCatS | 0.7839 | 0.8788 | 0.8655 |

| 18 | hCatF | hCatV | 0.5470 | 0.6393 | 0.8667 |

| 19 | hCatL | hCatV | 0.6782 | 0.6557 | 0.6694 |

| 20 | hCatS | hCatL | 0.7487 | 0.7931 | 0.8082 |

| 21 | hCatS | hCatV | 0.7985 | 0.8387 | 0.8371 |

| UniProt | Cluster | P3 | P2 | P1 | P1′ | P2′ | P3′ | P4′ | Cleavage (P1 Position) | Protein Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q3UWM4 | 336 | K | K | G | M | A | T | A | 916 | Lysine-specific demethylase 7 |

| Q80TJ7 | 336 | K | K | G | L | A | T | A | 1001 | Histone lysine demethylase PHF8 |

| Q9WTU0 | 336 | K | K | G | M | A | T | A | 1074 | Lysine-specific demethylase PHF2 |

| Q9R1Q8 | 339 | Q | A | G | M | T | G | Y | 188 | Transgelin-3 |

| Q9WVA4 | 339 | Q | A | G | M | T | G | Y | 188 | Transgelin-2 |

| P63325 | 389 | K | K | A | E | A | G | A | 140 | 40S ribosomal protein S10 |

| Q61464 | 389 | K | F | T | Q | A | G | A | 395 | Zinc finger protein 638 |

| P39749 | 396 | K | T | G | G | A | G | K | 369 | Flap endonuclease 1 |

| P97386 | 396 | K | R | G | T | A | G | C | 102 | DNA ligase 3 |

| ID 1357923 | ID 1357926 | ID 1358636 | ID 1358637 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mut mCatB+ 4m3 | mCatB+4m3 (PDB 9S60) | mut mCatB+4m3 | mCatB+4m3 (PDB 9S60) | ||||||

| Specified Interaction Region | Specified Interaction Region | ||||||||

| Coefficient Weights | E=0.40Erep+−0.40Eatt+600Eelec+1.00EDARS | E=0.40Erep+−0.10Eatt+600Eelec+0.00EDARS | E=0.40Erep+−0.40Eatt+600Eelec+1.00EDARS | E=0.40Erep+−0.40Eatt+600Eelec+1.00EDARS | |||||

| Representative | Cluster | Weighted score | Number of cluster members | Weighted score | Number of cluster members | Weighted score | Number of cluster members | Weighted score | Number of cluster members |

| Center | 0 | −1927.8 | 227 | −407.7 | 249 | −603.3 | 89 | −603.5 | 87 |

| Lowest Energy | −1991.6 | −569.9 | −633.8 | −633.8 | |||||

| Center | 1 | −1733.2 | 96 | −321.1 | 107 | −736.4 | 68 | −715.5 | 85 |

| Lowest Energy | −1797.4 | −362.6 | −840.9 | −762.6 | |||||

| Center | 2 | −1412.9 | 83 | −318.4 | 101 | −690.2 | 66 | −736.4 | 66 |

| Lowest Energy | −1628.9 | −496.6 | −690.2 | −840.9 | |||||

| Center | 3 | −1444.7 | 64 | −334.2 | 85 | −687.0 | 59 | −690.3 | 65 |

| Lowest Energy | −1570.3 | −447.2 | −687.0 | −690.3 | |||||

| Center | 4 | −1508.3 | 62 | −359.4 | 77 | −770.8 | 52 | −686.8 | 56 |

| Lowest Energy | −1887.9 | −404.4 | −770.8 | −686.8 | |||||

| Center | 5 | −1528.5 | 47 | −365.4 | 62 | −633.6 | 49 | −762.3 | 51 |

| Lowest Energy | −1621.3 | −365.4 | −762.3 | −762.3 | |||||

| Center | 6 | −1422.7 | 44 | −312.8 | 43 | −661.5 | 47 | −770.8 | 49 |

| Lowest Energy | −1560.4 | −383.4 | −758.2 | −770.8 | |||||

| Center | 7 | −1467.2 | 33 | −333.9 | 39 | −693.6 | 43 | −693.6 | 41 |

| Lowest Energy | −1650.4 | −350.1 | −708.4 | −708.4 | |||||

| Center | 8 | −1497.1 | 33 | −308.6 | 34 | −615.5 | 43 | −615.8 | 39 |

| Lowest Energy | −1653.3 | −409.5 | −615.5 | −615.8 | |||||

| Center | 9 | −1446.4 | 31 | −313.0 | 33 | −628.5 | 41 | −628.0 | 38 |

| Lowest Energy | −1624.5 | −384.5 | −628.5 | −628.0 | |||||

| Center | 10 | −1415.3 | 30 | −315.3 | 32 | −580.5 | 39 | −581.0 | 37 |

| Lowest Energy | −1665.5 | −397.4 | −635.7 | −636.1 | |||||

| Center | 11 | −1531.8 | 29 | −311.3 | 29 | −605.6 | 36 | −605.6 | 37 |

| Lowest Energy | −1645.1 | −376.4 | −697.9 | −697.8 | |||||

| Center | 12 | −1464.0 | 27 | −336.5 | 25 | −590.7 | 34 | −590.7 | 33 |

| Lowest Energy | −1673.4 | −340.1 | −692.7 | −692.7 | |||||

| Center | 13 | −1559.0 | 23 | −323.1 | 21 | −613.5 | 30 | −613.8 | 33 |

| Lowest Energy | −1646.4 | −344.3 | −675.2 | −675.6 | |||||

| Center | 14 | −1472.0 | 23 | −330.9 | 18 | −597.8 | 26 | −576.4 | 26 |

| Lowest Energy | −1625.1 | −341.3 | −680.2 | −680.2 | |||||

| Center | 15 | −1446.2 | 22 | −330.0 | 14 | −614.0 | 25 | −614.3 | 24 |

| Lowest Energy | −1446.2 | −342.3 | −630.8 | −630.9 | |||||

| Center | 16 | −1410.8 | 21 | −321.3 | 13 | −631.9 | 22 | −592.0 | 20 |

| Lowest Energy | −1513.6 | −343.8 | −647.9 | −647.8 | |||||

| Center | 17 | −1404.4 | 19 | −327.5 | 12 | −600.5 | 21 | −600.8 | 20 |

| Lowest Energy | −1678.2 | −343.8 | −636.0 | −636.2 | |||||

| Center | 18 | −1448.3 | 17 | −571.1 | 18 | −571.4 | 17 | ||

| Lowest Energy | −1559.4 | −679.8 | −679.9 | ||||||

| Center | 19 | −1480.9 | 16 | −642.9 | 15 | −649.2 | 16 | ||

| Lowest Energy | −1574.2 | −642.9 | −649.2 | ||||||

| Center | 20 | −1415.9 | 13 | −602.4 | 14 | −642.6 | 15 | ||

| Lowest Energy | −1525.9 | −668.9 | −642.6 | ||||||

| Center | 21 | −1550.4 | 7 | −596.3 | 14 | −596.2 | 14 | ||

| Lowest Energy | −1590.9 | −634.0 | −633.9 | ||||||

| Center | 22 | −1475.9 | 6 | −579.3 | 13 | −602.7 | 13 | ||

| Lowest Energy | −1475.9 | −607.5 | −669.1 | ||||||

| Center | 23 | −1432.7 | 5 | −655.1 | 13 | −579.3 | 12 | ||

| Lowest Energy | −1645.6 | −655.1 | −607.5 | ||||||

| Center | 24 | −1435.2 | 5 | −626.3 | 13 | −577.4 | 11 | ||

| Lowest Energy | −1435.5 | −626.3 | −613.6 | ||||||

| Center | 25 | −577.4 | 12 | −655.2 | 11 | ||||

| Lowest Energy | −613.5 | −655.2 | |||||||

| Center | 26 | −598.9 | 10 | −625.8 | 11 | ||||

| Lowest Energy | −708.5 | −625.8 | |||||||

| Center | 27 | −581.8 | 9 | −581.8 | 9 | ||||

| Lowest Energy | −604.5 | −604.5 | |||||||

| Center | 28 | −568.6 | 5 | ||||||

| Lowest Energy | −647.8 | ||||||||

| mouse cathepsin B | DARPin 4m3 | 000_00 | 006_00 | 002_00 | 004_00 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seq.1 | Atom | Res. | Seq.2 | Seq.3 | Atom | Atom | Seq.4 | 9S60 | Bond length (Å) | Bond length (Å) | Bond length (Å) | Bond length (Å) |

| 896 | O | CYS | 62 | 4330 | NE1 | TRP | 45 | |||||

| 906 | O | CYS | 63 | 3877 | OG | SER | 12 | |||||

| 906 | O | CYS | 63 | 4837 | OH | TYR | 79 | 2.77 | 2.6702 | 2.7861 | 2.6399 | 2.638 |

| 907 | N | GLY | 64 | 4330 | NE1 | TRP | 45 | |||||

| 914 | N | ILE | 65 | 4816 | OG | SER | 78 | |||||

| 914 | N | ILE | 65 | 4837 | OH | TYR | 79 | 3.22 | 2.8232 | 3.4548 | 2.8894 | 3.0181 |

| 932 | O | ILE | 65 | 4219 | NH2 | ARG | 37 | 2.98 | 2.8218 | 3.1575 | 3.2417 | 2.9154 |

| 933 | N | GLN | 66 | 4837 | OH | TYR | 79 | 2.91 | 2.871 | 3.2043 | 2.7597 | 2.7713 |

| 944 | OE1 | GLN | 66 | 3772 | NZ | LYS | 5 | |||||

| 944 | OE1 | GLN | 66 | 4216 | NH1 | ARG | 37 | 3.34 | 2.6802 | 2.7271 | 2.6809 | 2.66 |

| 944 | OE1 | GLN | 66 | 4701 | OH | TYR | 70 | |||||

| 944 | OE1 | GLN | 66 | 4788 | O | LEU | 75 | |||||

| 944 | OE1 | GLN | 66 | 4816 | OG | SER | 78 | |||||

| 945 | NE2 | GLN | 66 | 3777 | O | LYS | 5 | |||||

| 945 | NE2 | GLN | 66 | 3838 | N | ASP | 9 | |||||

| 945 | NE2 | GLN | 66 | 3847 | OD2 | ASP | 9 | |||||

| 945 | NE2 | GLN | 66 | 4330 | NE1 | TRP | 45 | 3.54 | 2.969 | |||

| 945 | NE2 | GLN | 66 | 4837 | OH | TYR | 79 | |||||

| 949 | O | GLN | 66 | 4216 | NH1 | ARG | 37 | 3 | 2.6756 | 2.6955 | 2.9473 | 2.8724 |

| 949 | O | GLN | 66 | 4219 | NH2 | ARG | 37 | 3.3582 | 3.0714 | 3.1282 | 3.2709 | |

| 966 | O | GLY | 68 | 4216 | NH1 | ARG | 37 | |||||

| 966 | O | GLY | 68 | 4701 | OH | TYR | 70 | |||||

| 975 | OD1 | ASP | 69 | 4216 | NH1 | ARG | 37 | |||||

| 975 | OD1 | ASP | 69 | 4219 | NH2 | ARG | 37 | |||||

| 975 | OD1 | ASP | 69 | 4676 | O | TYR | 68 | 3.3878 | ||||

| 975 | OD1 | ASP | 69 | 4701 | OH | TYR | 70 | 2.9 | 2.7721 | |||

| 975 | OD1 | ASP | 69 | 5112 | OG | SER | 99 | 3.2379 | ||||

| 975 | OD1 | ASP | 69 | 5116 | N | LYS | 100 | |||||

| 975 | OD1 | ASP | 69 | 5132 | NZ | LYS | 100 | 2.7435 | 2.7872 | |||

| 975 | OD1 | ASP | 69 | 5175 | ND2 | ASN | 103 | 3.061 | 3.0298 | |||

| 976 | OD2 | ASP | 69 | 4183 | ND1 | HIS | 35 | |||||

| 976 | OD2 | ASP | 69 | 4216 | NH1 | ARG | 37 | |||||

| 976 | OD2 | ASP | 69 | 4650 | NZ | LYS | 67 | |||||

| 976 | OD2 | ASP | 69 | 4655 | O | LYS | 67 | |||||

| 976 | OD2 | ASP | 69 | 4673 | OH | TYR | 68 | |||||

| 976 | OD2 | ASP | 69 | 4701 | OH | TYR | 70 | 3.0169 | ||||

| 976 | OD2 | ASP | 69 | 5112 | OG | SER | 99 | 2.8871 | 2.8617 | |||

| 976 | OD2 | ASP | 69 | 5116 | N | LYS | 100 | 3.4947 | ||||

| 976 | OD2 | ASP | 69 | 5132 | NZ | LYS | 100 | 2.9037 | 2.8426 | |||

| 976 | OD2 | ASP | 69 | 5138 | N | TYR | 101 | 3.0628 | 3.1699 | |||

| 976 | OD2 | ASP | 69 | 5175 | ND2 | ASN | 103 | |||||

| 1005 | OD1 | ASN | 72 | 5155 | OH | TYR | 101 | 2.7815 | 2.5237 | |||

| 1005 | OD1 | ASN | 72 | 5132 | NZ | LYS | 100 | |||||

| 1006 | ND2 | ASN | 72 | 5155 | OH | TYR | 101 | |||||

| 1010 | O | ASN | 72 | 4650 | NZ | LYS | 67 | |||||

| 1010 | O | ASN | 72 | 5132 | NZ | LYS | 100 | 3.1431 | ||||

| 1018 | N | GLY | 74 | 5155 | OH | TYR | 101 | |||||

| 1018 | N | GLY | 74 | 4673 | OH | TYR | 68 | |||||

| 1024 | O | GLY | 74 | 4183 | ND1 | HIS | 35 | 2.6731 | 2.754 | |||

| 1024 | O | GLY | 74 | 4673 | OH | TYR | 68 | 3.14 | 2.6048 | 2.6226 | 2.6693 | |

| 1042 | OH | TYR | 75 | 4162 | OD2 | ASP | 33 | 2.58 | 2.9256 | 2.8356 | 2.8501 | 2.8709 |

| 1042 | OH | TYR | 75 | 4192 | O | HIS | 35 | |||||

| 1042 | OH | TYR | 75 | 4330 | NE1 | TRP | 45 | |||||

| 1042 | OH | TYR | 75 | 4630 | OD1 | ASP | 66 | |||||

| 1067 | OG | SER | 77 | 4162 | OD2 | ASP | 33 | 3.0181 | ||||

| 1060 | N | SER | 77 | 4189 | NE2 | HIS | 35 | 3.447 | ||||

| 1067 | OG | SER | 77 | 4189 | NE2 | HIS | 35 | 2.9973 | ||||

| 1077 | O | GLY | 78 | 4837 | OH | TYR | 79 | |||||

| 1119 | OG | SER | 81 | 3880 | O | SER | 12 | 3.427 | ||||

| 1119 | OG | SER | 81 | 4330 | NE1 | TRP | 45 | 3.04 | 2.77 | |||

| 1119 | OG | SER | 81 | 3847 | OD2 | ASP | 9 | |||||

| 1119 | OG | SER | 81 | 3877 | OG | SER | 12 | 3.03 | 2.7744 | 2.7806 | ||

| 1122 | O | SER | 81 | 4330 | NE1 | TRP | 45 | 2.8007 | 3.1864 | |||

| 1122 | O | SER | 81 | 4837 | OH | TYR | 79 | |||||

| 1123 | N | PHE | 82 | 4837 | OH | TYR | 79 | |||||

| 1197 | NZ | LYS | 85 | 3846 | OD1 | ASP | 9 | |||||

| 1197 | NZ | LYS | 85 | 3849 | O | ASP | 9 | |||||

| 1197 | NZ | LYS | 85 | 3877 | OG | SER | 12 | |||||

| 1197 | NZ | LYS | 85 | 3880 | O | SER | 12 | 2.71 | 2.8243 | 2.8216 | 2.7342 | |

| 1197 | NZ | LYS | 85 | 3890 | O | ALA | 13 | 3.46 | 2.9464 | 2.8628 | 2.7085 | |

| 1197 | NZ | LYS | 85 | 3950 | OE1 | GLU | 18 | |||||

| 1197 | NZ | LYS | 85 | 3951 | OE2 | GLU | 18 | |||||

| 1197 | NZ | LYS | 85 | 4342 | O | TRP | 45 | 2.7365 | 2.7946 | |||

| 1197 | NZ | LYS | 85 | 4353 | O | SER | 46 | 2.8315 | 3.0939 | 2.8378 | 2.959 | |

| 1197 | NZ | LYS | 85 | 4840 | O | TYR | 79 | |||||

| 1197 | NZ | LYS | 85 | 4862 | NE2 | HIS | 81 | 2.9283 | ||||

| 1197 | NZ | LYS | 85 | 5327 | NE2 | HIS | 114 | |||||

| 1219 | NZ | LYS | 86 | 3859 | O | ALA | 10 | |||||

| 1219 | NZ | LYS | 86 | 3880 | O | SER | 12 | |||||

| 1219 | NZ | LYS | 86 | 3890 | O | ALA | 13 | |||||

| 1219 | NZ | LYS | 86 | 3897 | O | GLY | 14 | |||||

| 1219 | NZ | LYS | 86 | 3909 | OE1 | GLN | 15 | |||||

| 1219 | NZ | LYS | 86 | 4342 | O | TRP | 45 | |||||

| 1219 | NZ | LYS | 86 | 4353 | O | SER | 46 | |||||

| 1219 | NZ | LYS | 86 | 4840 | O | TYR | 79 | 2.9024 | ||||

| 1219 | NZ | LYS | 86 | 5294 | O | THR | 111 | |||||

| 1219 | NZ | LYS | 86 | 5305 | O | SER | 112 | |||||

| 1219 | NZ | LYS | 86 | 5757 | OD2 | ASP | 144 | |||||

| 1219 | NZ | LYS | 86 | 5768 | OD1 | ASN | 145 | |||||

| 1219 | NZ | LYS | 86 | 5789 | OD1 | ASN | 147 | |||||

| 1723 | OE1 | GLU | 122 | 5132 | NZ | LYS | 100 | 2.61 | ||||

| 1724 | OE2 | GLU | 122 | 5132 | NZ | LYS | 100 | 2.778 | ||||

| 1724 | OE2 | GLU | 122 | 5155 | OH | TYR | 101 | 2.9329 | 2.8396 | |||

| 1742 | OD1 | ASP | 124 | 5769 | ND2 | ASN | 145 | |||||

| 1743 | OD2 | ASP | 124 | 5769 | ND2 | ASN | 145 | |||||

| 1743 | OD2 | ASP | 124 | 5155 | OH | TYR | 101 | |||||

| 1759 | O | THR | 125 | 5769 | ND2 | ASN | 145 | |||||

| 1746 | N | THR | 125 | 5155 | OH | TYR | 101 | |||||

| 1752 | OG1 | THR | 125 | 5155 | OH | TYR | 101 | |||||

| 1787 | NE | ARG | 127 | 5768 | OD1 | ASN | 145 | |||||

| 1787 | NE | ARG | 127 | 4819 | O | SER | 78 | |||||

| 1787 | NE | ARG | 127 | 5610 | O | ALA | 134 | |||||

| 1790 | NH1 | ARG | 127 | 4840 | O | TYR | 79 | |||||

| 1790 | NH1 | ARG | 127 | 5327 | NE2 | HIS | 114 | |||||

| 1790 | NH1 | ARG | 127 | 5756 | OD1 | ASP | 144 | 3.4703 | 2.7657 | |||

| 1790 | NH1 | ARG | 127 | 5759 | O | ASP | 144 | 3.38 | 2.9402 | 2.8585 | 2.8483 | |

| 1790 | NH1 | ARG | 127 | 5768 | OD1 | ASN | 145 | 2.7478 | 2.6823 | |||

| 1790 | NH1 | ARG | 127 | 5773 | O | ASN | 145 | |||||

| 1790 | NH1 | ARG | 127 | 5780 | O | GLY | 146 | |||||

| 1793 | NH2 | ARG | 127 | 5756 | OD1 | ASP | 144 | 2.8136 | ||||

| 1793 | NH2 | ARG | 127 | 5757 | OD2 | ASP | 144 | 2.8135 | ||||

| 1793 | NH2 | ARG | 127 | 5768 | OD1 | ASN | 145 | |||||

| 1793 | NH2 | ARG | 127 | 5773 | O | ASN | 145 | |||||

| 1793 | NH2 | ARG | 127 | 5780 | O | GLY | 146 | |||||

| 1793 | NH2 | ARG | 127 | 5789 | OD1 | ASN | 147 | |||||

| 1793 | NH2 | ARG | 127 | 5756 | OD1 | ASP | 144 | 2.7293 | ||||

| 1793 | NH2 | ARG | 127 | 4819 | O | SER | 78 | |||||

| 1793 | NH2 | ARG | 127 | 5305 | O | SER | 112 | |||||

| 1793 | NH2 | ARG | 127 | 5327 | NE2 | HIS | 114 | |||||

| 1793 | NH2 | ARG | 127 | 5757 | OD2 | ASP | 144 | 2.6142 | ||||

| 1793 | NH2 | ARG | 127 | 5759 | O | ASP | 144 | 3.32 | 2.8846 | |||

| 1793 | NH2 | ARG | 127 | 5610 | O | ALA | 134 | |||||

| 1793 | NH2 | ARG | 127 | 5617 | O | GLY | 135 | |||||

| 1793 | NH2 | ARG | 127 | 5759 | O | ASP | 144 | 2.9702 | ||||

| 1838 | NZ | LYS | 130 | 5756 | OD1 | ASP | 144 | |||||

| 1838 | NZ | LYS | 130 | 5757 | OD2 | ASP | 144 | |||||

| 1838 | NZ | LYS | 130 | 4353 | O | SER | 46 | |||||

| 1838 | NZ | LYS | 130 | 5759 | O | ASP | 144 | |||||

| 1838 | NZ | LYS | 130 | 5768 | OD1 | ASN | 145 | |||||

| 1991 | NZ | LYS | 141 | 5759 | O | ASP | 144 | |||||

| 1991 | NZ | LYS | 141 | 5773 | O | ASN | 145 | |||||

| 1991 | NZ | LYS | 141 | 5780 | O | GLY | 146 | |||||

| 2136 | O | SER | 150 | 3772 | NZ | LYS | 5 | |||||

| 2158 | N | SER | 152 | 3846 | OD1 | ASP | 9 | 2.8916 | 2.8338 | 2.9605 | 2.9852 | |

| 2158 | N | SER | 152 | 3847 | OD2 | ASP | 9 | 3.05 | 3.0655 | 2.9639 | 3.1333 | |

| 2165 | OG | SER | 152 | 3846 | OD1 | ASP | 9 | 2.8168 | 2.7938 | 2.9298 | 2.9162 | |

| 2165 | OG | SER | 152 | 3847 | OD2 | ASP | 9 | 3.0765 | ||||

| 2165 | OG | SER | 152 | 3877 | OG | SER | 12 | |||||

| 2165 | OG | SER | 152 | 3880 | O | SER | 12 | |||||

| 2165 | OG | SER | 152 | 4162 | OD2 | ASP | 33 | |||||

| 2168 | O | SER | 152 | 3847 | OD2 | ASP | 9 | 2.9045 | ||||

| 2168 | O | SER | 152 | 3772 | NZ | LYS | 5 | 3.4027 | ||||

| 2184 | O | VAL | 153 | 3772 | NZ | LYS | 5 | 3.37 | 2.6812 | 2.9603 | ||

| 2185 | N | SER | 154 | 3772 | NZ | LYS | 5 | 3.3823 | ||||

| 2192 | OG | SER | 154 | 3794 | NZ | LYS | 6 | 2.688 | 2.561 | |||

| 2192 | OG | SER | 154 | 3910 | NE2 | GLN | 15 | |||||

| 2192 | OG | SER | 154 | 3772 | NZ | LYS | 5 | 2.8022 | ||||

| 2204 | OD1 | ASN | 155 | 3726 | OD1 | ASP | 2 | |||||

| 2204 | OD1 | ASN | 155 | 3794 | NZ | LYS | 6 | |||||

| 2205 | ND2 | ASN | 155 | 3726 | OD1 | ASP | 2 | |||||

| 2205 | ND2 | ASN | 155 | 3727 | OD2 | ASP | 2 | |||||

| 2205 | ND2 | ASN | 155 | 3847 | OD2 | ASP | 9 | |||||

| 2205 | ND2 | ASN | 155 | 3727 | OD2 | ASP | 2 | |||||

| 2205 | ND2 | ASN | 155 | 3794 | NZ | LYS | 6 | |||||

| 2205 | ND2 | ASN | 155 | 3847 | OD2 | ASP | 9 | |||||

| 2209 | O | ASN | 155 | 3794 | NZ | LYS | 6 | |||||

| 3482 | ND2 | ASN | 238 | 3726 | OD1 | ASP | 2 | |||||

| 3482 | ND2 | ASN | 238 | 3727 | OD2 | ASP | 2 | |||||

| 3482 | ND2 | ASN | 238 | 3772 | NZ | LYS | 5 | |||||

| 3564 | OG | SER | 244 | 3772 | NZ | LYS | 5 | |||||

| 3567 | O | SER | 244 | 3772 | NZ | LYS | 5 | 2.6728 | 3.0517 | 3.4348 | ||

| 3567 | O | SER | 244 | 3846 | OD1 | ASP | 9 | |||||

| 3567 | O | SER | 244 | 3847 | OD2 | ASP | 9 | |||||

| 3579 | OE1 | GLU | 245 | 3772 | NZ | LYS | 5 | 2.5268 | ||||

| 3579 | OE1 | GLU | 245 | 4165 | N | ALA | 34 | 3.1376 | 2.7023 | 3.4453 | ||

| 3579 | OE1 | GLU | 245 | 4174 | O | ALA | 34 | 3.3716 | ||||

| 3579 | OE1 | GLU | 245 | 4175 | N | HIS | 35 | 3.0971 | 3.1293 | |||

| 3579 | OE1 | GLU | 245 | 4183 | ND1 | HIS | 35 | |||||

| 3579 | OE1 | GLU | 245 | 4189 | NE2 | HIS | 35 | 3.4091 | ||||

| 3579 | OE1 | GLU | 245 | 4650 | NZ | LYS | 67 | 2.807 | 2.5528 | |||

| 3580 | OE2 | GLU | 245 | 4165 | N | ALA | 34 | 2.8597 | ||||

| 3580 | OE2 | GLU | 245 | 4175 | N | HIS | 35 | 2.762 | 3.3268 | |||

| 3580 | OE2 | GLU | 245 | 4183 | ND1 | HIS | 35 | 2.85 | ||||

| 3580 | OE2 | GLU | 245 | 4189 | NE2 | HIS | 35 | 2.9 | 3.3773 | |||

| 3580 | OE2 | GLU | 245 | 4650 | NZ | LYS | 67 | 2.8116 | 3.1788 | |||

| 3580 | OE2 | GLU | 245 | 4673 | OH | TYR | 68 | |||||

| mutated mCatB | DARPin 4m3 | 000_00 | 002_00 | ||||||

| Seq.1 | Atom | Res. | Seq.2 | Seq.3 | Atom | Atom | Seq.4 | Bond length (Å) | Bond length (Å) |

| 886 | O | THR | 61 | 4322 | NE1 | TRP | 45 | ||

| 906 | O | CYS | 63 | 4829 | OH | TYR | 79 | 2.5494 | 2.5218 |

| 906 | O | CYS | 63 | 3869 | OG | SER | 12 | ||

| 914 | N | SER | 65 | 4829 | OH | TYR | 79 | 3.023 | 2.9128 |

| 914 | N | SER | 65 | 5167 | ND2 | ASN | 103 | ||

| 921 | OG | SER | 65 | 4280 | O | HIS | 41 | ||

| 921 | OG | SER | 65 | 4281 | N | ALA | 42 | ||

| 921 | OG | SER | 65 | 4761 | O | HIS | 74 | 2.8814 | |

| 921 | OG | SER | 65 | 4808 | OG | SER | 78 | 3.4602 | 2.8349 |

| 921 | OG | SER | 65 | 4829 | OH | TYR | 79 | 3.4503 | |

| 921 | OG | SER | 65 | 4854 | NE2 | HIS | 81 | ||

| 921 | OG | SER | 65 | 5166 | OD1 | ASN | 103 | ||

| 921 | OG | SER | 65 | 5167 | ND2 | ASN | 103 | ||

| 924 | O | SER | 65 | 4211 | NH2 | ARG | 37 | 3.335 | 2.7094 |

| 925 | N | MET | 66 | 4829 | OH | TYR | 79 | 2.6753 | 2.697 |

| 941 | O | MET | 66 | 4208 | NH1 | ARG | 37 | 2.8147 | 2.788 |

| 941 | O | MET | 66 | 4211 | NH2 | ARG | 37 | 3.2862 | |

| 941 | O | MET | 66 | 4829 | OH | TYR | 79 | ||

| 952 | N | GLY | 68 | 4211 | NH2 | ARG | 37 | ||

| 958 | O | GLY | 68 | 4693 | OH | TYR | 70 | ||

| 958 | O | GLY | 68 | 4208 | NH1 | ARG | 37 | ||

| 967 | OD1 | ASP | 69 | 4208 | NH1 | ARG | 37 | ||

| 967 | OD1 | ASP | 69 | 4211 | NH2 | ARG | 37 | ||

| 967 | OD1 | ASP | 69 | 4693 | OH | TYR | 70 | 3.0486 | |

| 967 | OD1 | ASP | 69 | 4808 | OG | SER | 78 | ||

| 967 | OD1 | ASP | 69 | 5104 | OG | SER | 99 | ||

| 967 | OD1 | ASP | 69 | 5167 | ND2 | ASN | 103 | 3.098 | |

| 967 | OD1 | ASP | 69 | 5124 | NZ | LYS | 100 | 2.8428 | |

| 968 | OD2 | ASP | 69 | 5124 | NZ | LYS | 100 | 3.1307 | |

| 968 | OD2 | ASP | 69 | 4208 | NH1 | ARG | 37 | ||

| 968 | OD2 | ASP | 69 | 4211 | NH2 | ARG | 37 | ||

| 968 | OD2 | ASP | 69 | 4693 | OH | TYR | 70 | 3.0127 | |

| 968 | OD2 | ASP | 69 | 4808 | OG | SER | 78 | ||

| 968 | OD2 | ASP | 69 | 5104 | OG | SER | 99 | 2.8854 | |

| 968 | OD2 | ASP | 69 | 5108 | N | LYS | 100 | ||

| 968 | OD2 | ASP | 69 | 5130 | N | TYR | 101 | 3.019 | |

| 997 | OD1 | ASN | 72 | 5124 | NZ | LYS | 100 | ||

| 997 | OD1 | ASN | 72 | 5147 | OH | TYR | 101 | 2.8299 | |

| 998 | ND2 | ASN | 72 | 5147 | OH | TYR | 101 | ||

| 997 | OD1 | ASN | 72 | 5167 | ND2 | ASN | 103 | ||

| 1002 | O | ASN | 72 | 4693 | OH | TYR | 70 | ||

| 1009 | O | GLY | 73 | 4665 | OH | TYR | 68 | ||

| 1016 | O | GLY | 74 | 4665 | OH | TYR | 68 | 2.6996 | 2.5513 |

| 1016 | O | GLY | 74 | 4175 | ND1 | HIS | 68 | 3.0273 | |

| 1010 | N | GLY | 74 | 4665 | OH | TYR | 68 | 3.4597 | |

| 1034 | OH | TYR | 75 | 4154 | OD2 | ASP | 33 | 2.8301 | 2.8683 |

| 1034 | OH | TYR | 75 | 4153 | OD1 | ASP | 33 | ||

| 1059 | OG | SER | 77 | 4154 | OD2 | ASP | 33 | 3.0075 | |

| 1059 | OG | SER | 77 | 4153 | OD1 | ASP | 33 | ||

| 1059 | OG | SER | 77 | 4175 | ND1 | HIS | 35 | ||

| 1069 | O | GLY | 78 | 4829 | OH | TYR | 79 | ||

| 1111 | OG | SER | 81 | 3869 | OG | SER | 12 | 2.8087 | 2.7825 |

| 1114 | O | SER | 81 | 4322 | NE1 | TRP | 45 | 2.9881 | 2.8261 |

| 1111 | OG | SER | 81 | 3838 | OD1 | ASP | 9 | ||

| 1111 | OG | SER | 81 | 3764 | NZ | LYS | 5 | ||

| 1111 | OG | SER | 81 | 3838 | OD1 | ASP | 9 | ||

| 1111 | OG | SER | 81 | 3839 | OD2 | ASP | 9 | ||

| 1114 | O | SER | 81 | 3838 | OD1 | ASP | 9 | ||

| 1115 | N | PHE | 82 | 3838 | OD1 | ASP | 9 | ||

| 1189 | NZ | LYS | 85 | 3718 | OD1 | ASP | 2 | ||

| 1189 | NZ | LYS | 85 | 3719 | OD2 | ASP | 2 | ||

| 1189 | NZ | LYS | 85 | 3838 | OD1 | ASP | 9 | ||

| 1189 | NZ | LYS | 85 | 3839 | OD2 | ASP | 9 | ||

| 1189 | NZ | LYS | 85 | 3841 | O | ASP | 9 | ||

| 1189 | NZ | LYS | 85 | 3872 | O | SER | 12 | 2.8225 | 2.7958 |

| 1189 | NZ | LYS | 85 | 3882 | O | ALA | 13 | 2.887 | 2.9848 |

| 1189 | NZ | LYS | 85 | 4334 | O | TRP | 45 | 3.2962 | 2.7322 |

| 1189 | NZ | LYS | 85 | 4345 | O | SER | 46 | 2.8047 | 2.7191 |

| 1189 | NZ | LYS | 85 | 4832 | O | TYR | 79 | ||

| 1211 | NZ | LYS | 86 | 4832 | O | TYR | 79 | 2.9751 | |

| 1211 | NZ | LYS | 86 | 5286 | O | THR | 111 | ||

| 1211 | NZ | LYS | 86 | 5297 | O | SER | 112 | ||

| 1211 | NZ | LYS | 86 | 5761 | ND2 | ASN | 145 | ||

| 1211 | NZ | LYS | 86 | 5781 | OD1 | ASN | 147 | ||

| 1211 | NZ | LYS | 86 | 3901 | OE1 | GLN | 15 | ||

| 1211 | NZ | LYS | 86 | 3942 | OE1 | GLU | 18 | ||

| 1211 | NZ | LYS | 86 | 3943 | OE2 | GLU | 18 | ||

| 1716 | OE2 | GLU | 122 | 5147 | OH | TYR | 101 | 2.8632 | |

| 1715 | OE1 | GLU | 122 | 5124 | NZ | LYS | 100 | ||

| 1716 | OE2 | GLU | 122 | 5124 | NZ | LYS | 100 | ||

| 1715 | OE1 | GLU | 122 | 5147 | OH | TYR | 101 | ||

| 1735 | OD2 | ASP | 124 | 5147 | OH | TYR | 101 | ||

| 1734 | OD1 | ASP | 124 | 5761 | ND2 | ASN | 145 | ||

| 1735 | OD2 | ASP | 124 | 5761 | ND2 | ASN | 145 | ||

| 1735 | OD2 | ASP | 124 | 5279 | OG1 | THR | 111 | ||

| 1735 | OD2 | ASP | 124 | 4829 | OH | TYR | 79 | ||

| 1738 | N | THR | 125 | 5147 | OH | TYR | 101 | ||

| 1744 | OG1 | THR | 125 | 5147 | OH | TYR | 101 | ||

| 1738 | N | THR | 125 | 4829 | OH | TYR | 79 | ||

| 1751 | O | THR | 125 | 4829 | OH | TYR | 79 | ||

| 1779 | NE | ARG | 127 | 5602 | O | ALA | 134 | ||

| 1779 | NE | ARG | 127 | 5765 | O | ASN | 145 | ||

| 1782 | NH1 | ARG | 127 | 5751 | O | ASP | 144 | 2.8501 | 2.8624 |

| 1782 | NH1 | ARG | 127 | 5760 | OD1 | ASN | 145 | 2.7165 | 2.7153 |

| 1782 | NH1 | ARG | 127 | 5297 | O | SER | 112 | ||

| 1782 | NH1 | ARG | 127 | 4832 | O | TYR | 79 | ||

| 1785 | NH2 | ARG | 127 | 5748 | OD1 | ASP | 144 | 2.6152 | 2.9704 |

| 1785 | NH2 | ARG | 127 | 5749 | OD2 | ASP | 144 | 2.6152 | 2.6974 |

| 1785 | NH2 | ARG | 127 | 5751 | O | ASP | 144 | 2.8891 | 2.9265 |

| 1785 | NH2 | ARG | 127 | 5602 | O | ALA | 134 | ||

| 1785 | NH2 | ARG | 127 | 5609 | O | GLY | 135 | ||

| 1785 | NH2 | ARG | 127 | 5286 | O | THR | 111 | ||

| 1785 | NH2 | ARG | 127 | 5765 | O | ASN | 145 | ||

| 1785 | NH2 | ARG | 127 | 5781 | OD1 | ASN | 147 | ||

| 1785 | NH2 | ARG | 127 | 5319 | NE2 | HIS | 114 | ||

| 1830 | NZ | LYS | 130 | 5751 | O | ASP | 144 | ||

| 1830 | NZ | LYS | 130 | 5760 | OD1 | ASN | 145 | ||

| 1830 | NZ | LYS | 130 | 3872 | O | SER | 12 | ||

| 1830 | NZ | LYS | 130 | 4345 | O | SER | 46 | ||

| 1983 | NZ | LYS | 141 | 5765 | O | ASN | 145 | ||

| 1983 | NZ | LYS | 141 | 5772 | O | GLY | 146 | ||

| 1983 | NZ | LYS | 141 | 3882 | O | ALA | 13 | ||

| 1983 | NZ | LYS | 141 | 3889 | O | GLY | 14 | ||

| 2125 | OG | SER | 150 | 3764 | NZ | LYS | 5 | ||

| 2157 | OG | SER | 152 | 3764 | NZ | LYS | 5 | ||

| 2150 | N | SER | 152 | 3838 | OD1 | ASP | 9 | 2.9512 | 2.8781 |

| 2157 | OG | SER | 152 | 3838 | OD1 | ASP | 9 | 2.9279 | 2.8744 |

| 2150 | N | SER | 152 | 3839 | OD2 | ASP | 9 | 2.9574 | 2.8958 |

| 2157 | OG | SER | 152 | 3839 | OD2 | ASP | 9 | 3.1087 | 3.1892 |

| 2157 | OG | SER | 152 | 3869 | OG | SER | 12 | ||

| 2157 | OG | SER | 152 | 3872 | O | SER | 12 | ||

| 2157 | OG | SER | 152 | 4154 | OD2 | ASP | 33 | ||

| 2176 | O | VAL | 153 | 3764 | NZ | LYS | 5 | 2.9539 | |

| 2184 | OG | SER | 154 | 3902 | NE2 | GLN | 15 | ||

| 2184 | OG | SER | 154 | 3786 | NZ | LYS | 6 | 2.6395 | |

| 2197 | ND2 | ASN | 155 | 3839 | OD2 | ASP | 9 | ||

| 2847 | O | GLY | 198 | 5124 | NZ | LYS | 100 | ||

| 3559 | O | SER | 244 | 3764 | NZ | LYS | 5 | 3.426 | |

| 3556 | OG | SER | 244 | 3764 | NZ | LYS | 5 | ||

| 3559 | O | SER | 244 | 3764 | NZ | LYS | 5 | 2.7417 | |

| 3559 | O | SER | 244 | 3838 | OD1 | ASP | 9 | ||

| 3571 | OE1 | GLU | 245 | 4157 | N | ALA | 34 | 3.4619 | 2.876 |

| 3572 | OE2 | GLU | 245 | 4157 | N | ALA | 34 | ||

| 3571 | OE1 | GLU | 245 | 4166 | O | ALA | 34 | 3.3640 | |

| 3571 | OE1 | GLU | 245 | 4167 | N | HIS | 35 | 3.0915 | |

| 3571 | OE1 | GLU | 245 | 4181 | NE2 | HIS | 35 | 3.4298 | |

| 3571 | OE1 | GLU | 245 | 4642 | NZ | LYS | 67 | 2.8035 | |

| 3572 | OE2 | GLU | 245 | 4181 | NE2 | HIS | 35 | 3.3363 | |

| 3572 | OE2 | GLU | 245 | 4642 | NZ | LYS | 67 | 2.7912 | |

| 3571 | OE1 | GLU | 245 | 3764 | NZ | LYS | 5 | 2.7712 | |

| 3572 | OE2 | GLU | 245 | 3764 | NZ | LYS | 5 | 2.8691 | |

| 3571 | OE1 | GLU | 245 | 4642 | NZ | LYS | 67 | ||

| 3572 | OE2 | GLU | 245 | 4181 | NE2 | HIS | 35 | ||

| 3572 | OE2 | GLU | 245 | 4642 | NZ | LYS | 67 | ||

| 3572 | OE2 | GLU | 245 | 4665 | OH | TYR | 68 | ||

| Complex | Van Der Waals Contribution | Electrostatic Contribution | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| mCatB and DARPin 4m3 (PDB code 9S60), molecules A (mCatB) and B (DARPin 4m3) | −85.6724 | −339.6830 | −425.3554 |

| mCatB and DARPin 4m3 (PDB code 9S60), molecules A2 (mCatB) and B2 (DARPin 4m3) | −94.5953 | −444.2739 | −538.8692 |

| mCatB and DARPin 4m3, docking model 000_00, ID 1357926 | −28.4291 | −719.8384 | −748.2675 |

| mCatB and DARPin 4m3, docking model 002_00, ID 1357926 | −64.7532 | −555.6167 | −620.3699 |

| mCatB and DARPin 4m3, docking model 004_00, ID 1357926 | −41.1605 | −529.7449 | −570.9054 |

| mCatB and DARPin 4m3, docking model 006_00, ID 1357926 | −27.8825 | −316.9363 | −344.8188 |

| Mutated mCatB and DARPin 4m3, docking model 000_00, ID 1357923 | −65.0729 | −351.8250 | −416.8979 |

| Mutated mCatB and DARPin 4m3, docking model 002_00, ID 1357923 | −32.7603 | −516.1930 | −548.9533 |

| Mutated mCatB and DARPin 4m3, docking model 004_00, ID 1357923 | −32.6505 | −426.5532 | −459.2037 |

| Mutated mCatB and DARPin 4m3, docking model 006_00, ID 1357923 | −10.2918 | −416.8580 | −427.1498 |

References

- Kramer, L.; Turk, D.; Turk, B. The future of cysteine cathepsins in disease management. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2017, 38, 873–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biasizzo, M.; Javoršek, U.; Vidak, E.; Zarić, M.; Turk, B. Cysteine cathepsins: A long and winding road towards clinics. Mol. Asp. Med. 2022, 88, 101150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, O.C.; Joyce, J.A. Cysteine cathepsin proteases: Regulators of cancer progression and therapeutic response. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2015, 15, 712–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halangk, W.; Lerch, M.M.; Brandt-Nedelev, B.; Roth, W.; Ruthenbuerger, M.; Reinheckel, T.; Domschke, W.; Lippert, H.; Peters, C.; Deussing, J. Role of cathepsin B in intracellular trypsinogen activation and the onset of acute pancreatitis. J. Clin. Investig. 2000, 106, 773–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, R.W.; Ru, Y.; LoCastro, S.M.; Zeng, J.; Yamashita, D.S.; Oh, H.J.; Erhard, K.F.; Davis, L.D.; Tomaszek, T.A.; Tew, D.; et al. Azepanone-based inhibitors of human and rat cathepsin K. J. Med. Chem. 2001, 44, 1380–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroup, G.B.; Lark, M.W.; Veber, D.F.; Bhattacharyya, A.; Blake, S.; Dare, L.C.; Erhard, K.F.; Hoffman, S.J.; James, I.E.; Marquis, R.W.; et al. Potent and selective inhibition of human cathepsin K leads to inhibition of bone resorption in vivo in a nonhuman primate. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2001, 16, 1739–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desmarais, S.; Massé, F.; Percival, M.D. Pharmacological inhibitors to identify roles of cathepsin K in cell-based studies: A comparison of available tools. Biol. Chem. 2009, 390, 941–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindström, E.; Rizoska, B.; Henderson, I.; Terelius, Y.; Jerling, M.; Edenius, C.; Grabowska, U. Nonclinical and clinical pharmacological characterization of the potent and selective cathepsin K inhibitor MIV-711. J. Transl. Med. 2018, 16, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thurmond, R.L.; Sun, S.; Sehon, C.A.; Baker, S.M.; Cai, H.; Gu, Y.; Jiang, W.; Riley, J.P.; Williams, K.N.; Edwards, J.P.; et al. Identification of a potent and selective noncovalent cathepsin S inhibitor. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2004, 308, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameriks, M.K.; Axe, F.U.; Bembenek, S.D.; Edwards, J.P.; Gu, Y.; Karlsson, L.; Randal, M.; Sun, S.; Thurmond, R.L.; Zhu, J. Pyrazole-based cathepsin S inhibitors with arylalkynes as P1 binding elements. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 6131–6134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Dare, L.; Vasko-Moser, J.A.; James, I.E.; Blake, S.M.; Rickard, D.J.; Hwang, S.M.; Tomaszek, T.; Yamashita, D.S.; Marquis, R.W.; et al. A highly potent inhibitor of cathepsin K (relacatib) reduces biomarkers of bone resorption both in vitro and in an acute model of elevated bone turnover in vivo in monkeys. Bone 2007, 40, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerome, C.; Missbach, M.; Gamse, R. Balicatib, a cathepsin K inhibitor, stimulates periosteal bone formation in monkeys. Osteoporos. Int. 2011, 22, 3001–3011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, D.; Iwasaki, N.; Kon, S.; Matsui, Y.; Majima, T.; Minami, A.; Uede, T. Down-regulation of cathepsin K in synovium leads to progression of osteoarthritis in rabbits. Arthritis Rheum. 2009, 60, 2372–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennypacker, B.L.; Duong, L.T.; Cusick, T.E.; Masarachia, P.J.; Gentile, M.A.; Gauthier, J.Y.; Black, W.C.; Scott, B.B.; Samadfam, R.; Smith, S.Y.; et al. Cathepsin K inhibitors prevent bone loss in estrogen-deficient rabbits. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2011, 26, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennypacker, B.L.; Oballa, R.M.; Levesque, S.; Kimmel, D.B.; Duong, L.T. Cathepsin K inhibitors increase distal femoral bone mineral density in rapidly growing rabbits. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2013, 14, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caglič, D.; Kosec, G.; Bojič, L.; Reinheckel, T.; Turk, V.; Turk, B. Murine and human cathepsin B exhibit similar properties: Possible implications for drug discovery. Biol. Chem. 2009, 390, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binz, H.K.; Stumpp, M.T.; Forrer, P.; Amstutz, P.; Plückthun, A. Designing repeat proteins: Well-expressed, soluble and stable proteins from combinatorial libraries of consensus ankyrin repeat proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 2003, 332, 489–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seeger, M.A.; Zbinden, R.; Flütsch, A.; Gutte, P.G.M.; Engeler, S.; Roschitzki-Voser, H.; Grütter, M.G. Design, construction, and characterization of a second-generation DARPin library with reduced hydrophobicity. Protein Sci. 2013, 22, 1239–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, L.; Renko, M.; Završnik, J.; Turk, D.; Seeger, M.A.; Vasiljeva, O.; Grütter, M.G.; Turk, V.; Turk, B. Non-invasive in vivo imaging of tumour-associated cathepsin B by a highly selective inhibitory DARPin. Theranostics 2017, 7, 2806–2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahnd, C.; Amstutz, P.; Plückthun, A. Ribosome display: Selecting and evolving proteins in vitro that specifically bind to a target. Nat. Methods 2007, 4, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baici, A. The specific velocity plot. A graphical method for determining inhibition parameters for both linear and hyperbolic enzyme inhibitors. Eur. J. Biochem. 1981, 119, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szedlacsek, S.E.; Ostafe, V.; Serban, M.; Vlad, M.O. A re-evaluation of the kinetic equations for hyperbolic tight-binding inhibition. Biochem. J. 1988, 254, 311–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohl, A.; Binz, H.K.; Forrer, P.; Stumpp, M.T.; Plückthun, A.; Grütter, M.G. Designed to be stable: Crystal structure of a consensus ankyrin repeat protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 1700–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.A.; Rasband, W.S.; Eliceiri, K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Jaroszewski, L.; Iyer, M.; Sedova, M.; Godzik, A. FATCAT 2.0: Towards a better understanding of the structural diversity of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, W60–W64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turk, D. MAIN software for density averaging, model building, structure refinement and validation. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2013, 69, 1342–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozakov, D.; Hall, D.R.; Xia, B.; Porter, K.A.; Padhorny, D.; Yueh, C.; Beglov, D.; Vajda, S. The ClusPro web server for protein-protein docking. Nature Protocols 2017, 12, 255–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merritt, E.A.; Bacon, D.J. Raster3D: Photorealistic molecular graphics. In Methods in Enzymology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1997; Volume 277, pp. 505–524. [Google Scholar]

- Tušar, L.; Loboda, J.; Impens, F.; Sosnowski, P.; Van Quickelberghe, E.; Vidmar, R.; Demol, H.; Sedeyn, K.; Saelens, X.; Vizovišek, M.; et al. Proteomic data and structure analysis combined reveal interplay of structural rigidity and flexibility on selectivity of cysteine cathepsins. Commun. Biol. 2023, 6, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubowchik, G.M.; Firestone, R.A. Cathepsin B-sensitive dipeptide prodrugs. 1. A model study of structural requirements for efficient release of doxorubicin. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1998, 8, 3341–3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubowchik, G.M.; Mosure, K.; Knipe, J.O.; Firestone, R.A. Cathepsin B-sensitive dipeptide prodrugs. 2. Models of anticancer drugs paclitaxel (Taxol®), mitomycin C and doxorubicin. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1998, 8, 3347–3352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochdörffer, K.; Abu Ajaj, K.; Schäfer-Obodozie, C.; Kratz, F. Development of Novel Bisphosphonate Prodrugs of Doxorubicin for Targeting Bone Metastases That Are Cleaved pH Dependently or by Cathepsin B: Synthesis, Cleavage Properties, and Binding Properties to Hydroxyapatite As Well As Bone Matrix. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 7502–7515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryyma, A.; Gunasekera, S.; Lewin, J.; Perrin, D.M. Rapid, High-Yielding Solid-Phase Synthesis of Cathepsin-B Cleavable Linkers for Targeted Cancer Therapeutics. Bioconjug. Chem. 2020, 31, 2685–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keppler, D.; Sloane, B.F. Cathepsin B: Multiple enzyme forms from a single gene and their relation to cancer. Enzym. Protein 1996, 49, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Zhao, M.; Yan, C.; Kong, W.; Lan, F.; Narengaowa; Zhao, S.; Yang, Q.; Bai, Z.; Qing, H.; et al. Cathepsin B in programmed cell death machinery: Mechanisms of execution and regulatory pathways. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kos, J.; Mitrović, A.; Mirković, B. The current stage of cathepsin B inhibitors as potential anticancer agents. Future Med. Chem. 2014, 6, 1355–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turk, B.; Dolenc, I.; Zerovnik, E.; Turk, D.; Gubensek, F.; Turk, V. Human cathepsin B is a metastable enzyme stabilized by specific ionic interactions associated with the active site. Biochemistry 1994, 33, 14800–14806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schweizer, A.; Roschitzki-Voser, H.; Amstutz, P.; Briand, C.; Gulotti-Georgieva, M.; Prenosil, E.; Binz, H.K.; Capitani, G.; Baici, A.; Plückthun, A.; et al. Inhibition of caspase-2 by a designed ankyrin repeat protein: Specificity, structure, and inhibition mechanism. Structure 2007, 15, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiser, J.; Adair, B.; Reinheckel, T. Specialized roles for cysteine cathepsins in health and disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2010, 120, 3421–3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katunuma, N. Structure-based development of specific inhibitors for individual cathepsins and their medical applications. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 2011, 87, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sloane, B.; Yan, S.; Podgorski, I.; Linebaugh, B.; Cher, M.; Mai, J.; Cavallo-Medved, D.; Sameni, M.; Dosecu, J.; Moin, K. Cathepsin B and tumor proteolysis: Contribution of the tumor microenvironment. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2005, 15, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiljeva, O.; Papazoglou, A.; Krüger, A.; Brodoefel, H.; Korovin, M.; Deussing, J.; Augustin, N.; Nielsen, B.S.; Almholt, K.; Bogyo, M.; et al. Tumor Cell–Derived and Macrophage-Derived Cathepsin B Promotes Progression and Lung Metastasis of Mammary Cancer. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 5242–5250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gocheva, V.; Wang, H.W.; Gadea, B.B.; Shree, T.; Hunter, K.E.; Garfall, A.L.; Berman, T.; Joyce, J.A. IL-4 induces cathepsin protease activity in tumor-associated macrophages to promote cancer growth and invasion. Genes Dev. 2010, 24, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novinec, M.; Pavšič, M.; Lenarčič, B. A simple and efficient protocol for the production of recombinant cathepsin v and other cysteine cathepsins in soluble form in Escherichia coli. Protein Expr. Purif. 2012, 82, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozman-Pungerčar, J.; Kopitar-Jerala, N.; Bogyo, M.; Turk, D.; Vasiljeva, O.; Stefe, I.; Vandenabeele, P.; Brömme, D.; Puizdar, V.; Fonović, M.; et al. Inhibition of papain-like cysteine proteases and legumain by caspase-specific inhibitors: When reaction mechanism is more important than specificity. Cell Death Differ. 2003, 10, 881–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafari, R.; Almqvist, H.; Axelsson, H.; Ignatushchenko, M.; Lundbäck, T.; Nordlund, P.; Molina, D.M. The cellular thermal shift assay for evaluating drug target interactions in cells. Nat. Protoc. 2014, 9, 2100–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabsch, W. XDS. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010, 66, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCoy, A.J.; Grosse-Kunstleve, R.W.; Adams, P.D.; Winn, M.D.; Storoni, L.C.; Read, R.J. Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2007, 40, 658–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pražnikar, J.; Turk, D. Free kick instead of cross-validation in maximum-likelihood refinement of macromolecular crystal structures. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2014, 70, 3124–3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmer, J.C.; Zhu, W.; Pop, C.; Regan, T.; Snipas, S.J.; Eroshkin, A.M.; Riedl, S.J.; Salvesen, G.S. Structural and kinetic determinants of protease substrates. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009, 16, 1101–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAS Institute. Statistical Analysis Software (SAS) User’s Guide Version 9.4; SAS Institute, Inc.: Cary, NC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, E.C.; Goddard, T.D.; Pettersen, E.F.; Couch, G.S.; Pearson, Z.J.; Morris, J.H.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF ChimeraX: Tools for structure building and analysis. Protein Sci. 2023, 32, e4792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sievers, F.; Higgins, D.G. The Clustal Omega multiple alignment package. In Multiple Sequence Alignment; Katoh, K., Ed.; Humana: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 3–16. ISBN 978-1-0716-1035-0. [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse, A.M.; Procter, J.B.; Martin, D.M.A.; Clamp, M.; Barton, G.J. Jalview Version 2—A multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1189–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| ka [1/Ms] | kd [1/s] | KD [nM] | χ2 [RU2] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mCatB pH 6 | 9.80 × 104 | 6.44 × 10−3 | 65.7 | 0.021 |

| mCatB pH 7 | 8.55 × 104 | 9.25 × 10−3 | 108.3 | 0.004 |

| DARPin E3_5 | DMSO | DARPin 4m3 | CA074 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tagg (50% of mCatB maximum band intensity) | 52.1 °C | 52.9 °C | 62.9 °C | 71.6 °C |

| 95% confidence interval | 51.6 °C–52.8 °C | 52.3 °C–53.5 °C | 62.39 °C–63.35 °C | 70.7 °C–72.4 °C |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zarić, M.; Tušar, L.; Kramer, L.; Vasiljeva, O.; Novak, M.; Impens, F.; Usenik, A.; Gevaert, K.; Turk, D.; Turk, B. Structural and Proteomic Analysis of the Mouse Cathepsin B-DARPin 4m3 Complex Reveals Species-Specific Binding Determinants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11910. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411910

Zarić M, Tušar L, Kramer L, Vasiljeva O, Novak M, Impens F, Usenik A, Gevaert K, Turk D, Turk B. Structural and Proteomic Analysis of the Mouse Cathepsin B-DARPin 4m3 Complex Reveals Species-Specific Binding Determinants. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11910. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411910

Chicago/Turabian StyleZarić, Miki, Livija Tušar, Lovro Kramer, Olga Vasiljeva, Matej Novak, Francis Impens, Aleksandra Usenik, Kris Gevaert, Dušan Turk, and Boris Turk. 2025. "Structural and Proteomic Analysis of the Mouse Cathepsin B-DARPin 4m3 Complex Reveals Species-Specific Binding Determinants" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11910. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411910

APA StyleZarić, M., Tušar, L., Kramer, L., Vasiljeva, O., Novak, M., Impens, F., Usenik, A., Gevaert, K., Turk, D., & Turk, B. (2025). Structural and Proteomic Analysis of the Mouse Cathepsin B-DARPin 4m3 Complex Reveals Species-Specific Binding Determinants. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11910. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411910