Microenvironmental and Molecular Pathways Driving Dormancy Escape in Bone Metastases

Abstract

1. Introduction

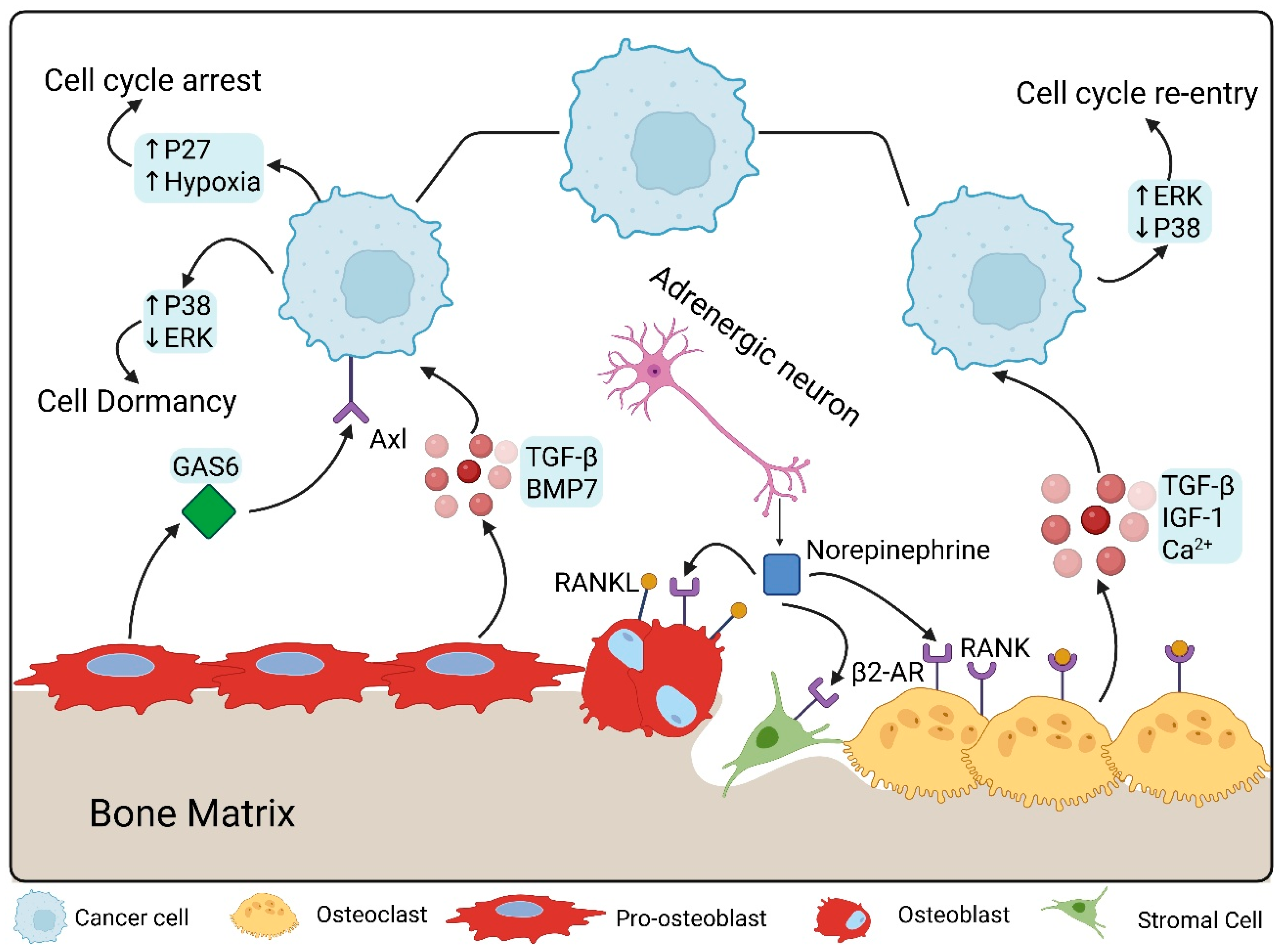

2. Conceptual Framework: Dormancy vs. Escape

2.1. Definitions

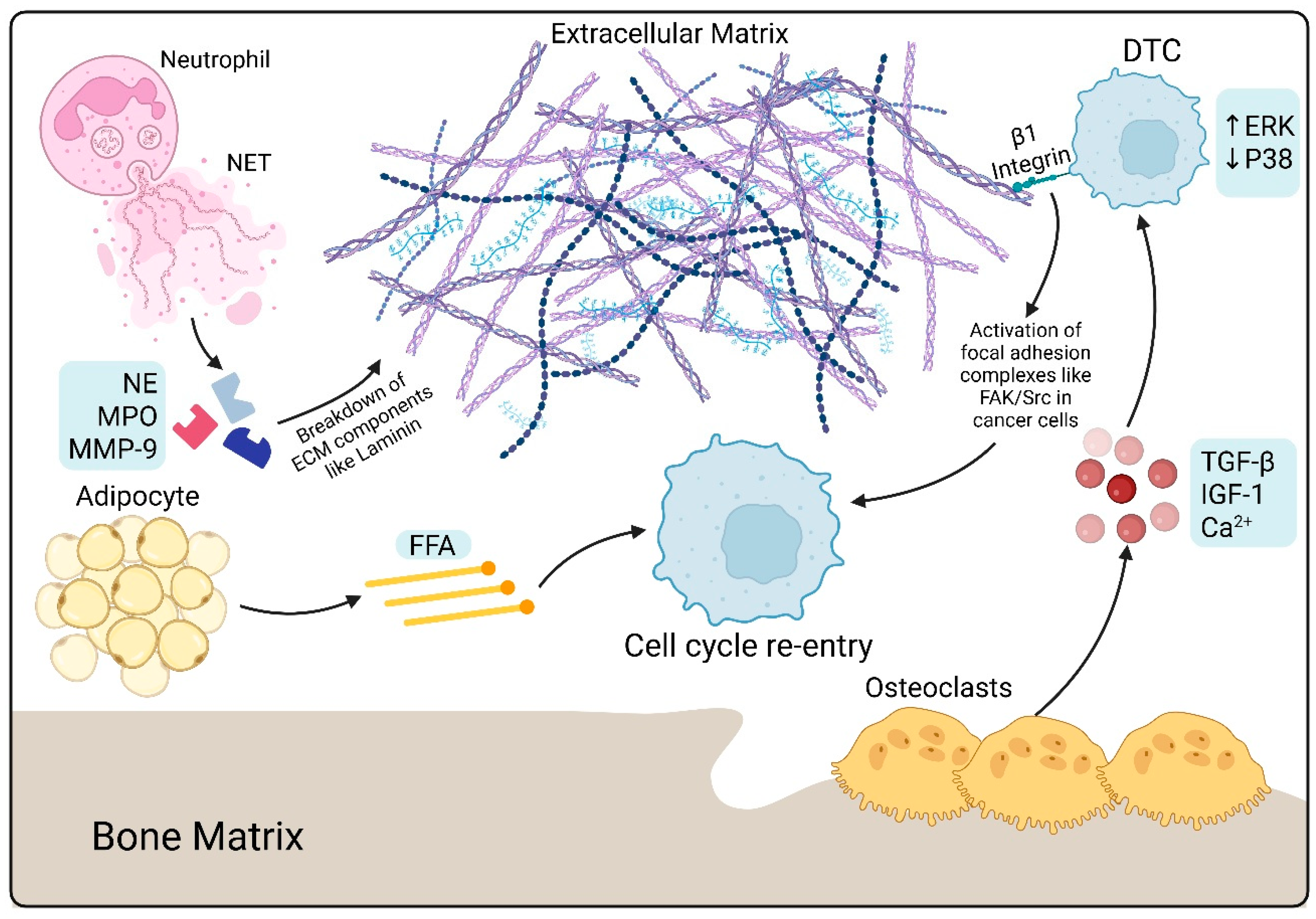

2.2. Key Regulators of Dormancy Maintenance

2.3. Transition to Escape

3. Bone Microenvironment Cues Driving Dormancy Escape

3.1. Osteoclast Activity and Bone Resorption

3.2. Osteoblast and Endosteal Niche Remodeling

3.3. Bone Marrow Adipocytes (BMAs)

4. Immune System-Mediated Escape

4.1. Loss of Immune Surveillance

4.2. Immunosuppressive Microenvironment

4.3. Inflammatory Triggers

5. Extracellular Matrix (ECM) and Mechanobiology

5.1. ECM Remodeling

5.2. Mechanotransduction

6. Angiogenesis and Vascular Niches

7. Systemic and Physiological Triggers

7.1. Aging and Senescence

7.2. Hormonal Changes

7.3. Stress and Neural Signaling

8. Epigenetic and Metabolic Reprogramming of Dormant Cells

8.1. Epigenetic Shifts

8.2. Metabolic Switches

9. Clinical Evidence of Dormancy Escape in Bone

10. Therapeutic Opportunities

10.1. Targeting Osteoclast-Mediated Escape

10.1.1. The Role of Denosumab in Bone Metastasis Dormancy

10.1.2. Recent Clinical Trials Combining Denosumab with Immunotherapy in Bone Metastasis

10.1.3. The Role of Bisphosphonates in Bone Metastasis Dormancy

10.1.4. Denosumab Versus Bisphosphonates: Evidence and Insights in Cancer Cell Dormancy

10.2. Boosting Immune Surveillance

10.3. Inhibiting ECM and Angiogenesis Remodeling

10.4. Epigenetic and Metabolic Therapies

11. Future Directions and Knowledge Gaps

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Coleman, R.E.; Croucher, P.I.; Padhani, A.R.; Clézardin, P.; Chow, E.; Fallon, M.; Guise, T.; Colangeli, S.; Capanna, R.; Costa, L. Bone Metastases. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2020, 6, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Li, X.; Qian, W.-P.; Wu, D.; Dong, J.-T. Measurement of Bone Metastatic Tumor Growth by a Tibial Tumorigenesis Assay. Bio Protoc. 2021, 11, e4231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Summers, M.A.; McDonald, M.M.; Croucher, P.I. Cancer Cell Dormancy in Metastasis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2020, 10, a037556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acquisto, A.; Duran Derijckere, I.; De Angelis, R. An Atypical Behavior of Metastatic Lung Disease in a Young Woman with Osteosarcoma: A Case Report. Cureus 2022, 14, e21589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMichele, A.; Clark, A.S.; Shea, E.; Bayne, L.J.; Sterner, C.J.; Rohn, K.; Dwyer, S.; Pan, T.-C.; Nivar, I.; Chen, Y.; et al. Targeting Dormant Tumor Cells to Prevent Recurrent Breast Cancer: A Randomized Phase 2 Trial. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 3464–3474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornetti, J.; Welm, A.L.; Stewart, S.A. Understanding the Bone in Cancer Metastasis. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2018, 33, 2099–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallón de Lara, P.; Castañón, H.; Vermeer, M.; Núñez, N.; Silina, K.; Sobottka, B.; Urdinez, J.; Cecconi, V.; Yagita, H.; Movahedian Attar, F.; et al. CD39+PD-1+CD8+ T Cells Mediate Metastatic Dormancy in Breast Cancer. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Bilecz, A.J.; Lengyel, E. The Adipocyte Microenvironment and Cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2022, 41, 575–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.O.; Yu, H.; Yue, R.; Zhao, Z.; Rios, J.J.; Naveiras, O.; Morrison, S.J. Bone Marrow Adipocytes Promote the Regeneration of Stem Cells and Haematopoiesis by Secreting SCF. Nat. Cell Biol. 2017, 19, 891–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghajar, C.M.; Peinado, H.; Mori, H.; Matei, I.R.; Evason, K.J.; Brazier, H.; Almeida, D.; Koller, A.; Hajjar, K.A.; Stainier, D.Y.R.; et al. The Perivascular Niche Regulates Breast Tumour Dormancy. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013, 15, 807–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbruggen, S.W.; Thompson, C.L.; Duffy, M.P.; Lunetto, S.; Nolan, J.; Pearce, O.M.T.; Jacobs, C.R.; Knight, M.M. Mechanical Stimulation Modulates Osteocyte Regulation of Cancer Cell Phenotype. Cancers 2021, 13, 2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreps, L.M.; Addison, C.L. Targeting Intercellular Communication in the Bone Microenvironment to Prevent Disseminated Tumor Cell Escape from Dormancy and Bone Metastatic Tumor Growth. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhang, X.; Liang, T.; Bai, X. Cancer Dormancy and Metabolism: From Molecular Insights to Translational Opportunities. Cancer Lett. 2025, 635, 218097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahanban-Esfahlan, R.; Seidi, K.; Manjili, M.H.; Jahanban-Esfahlan, A.; Javaheri, T.; Zare, P. Tumor Cell Dormancy: Threat or Opportunity in the Fight against Cancer. Cancers 2019, 11, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushnell, G.G.; Sharma, D.; Wilmot, H.C.; Zheng, M.; Fashina, T.D.; Hutchens, C.M.; Osipov, S.; Burness, M.; Wicha, M.S. Natural Killer Cell Regulation of Breast Cancer Stem Cells Mediates Metastatic Dormancy. Cancer Res. 2024, 84, 3337–3353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldar, R.; Berger, L.S.; Rossenne, E.; Radin, A.; Eckerling, A.; Sandbank, E.; Sloan, E.K.; Cole, S.W.; Ben-Eliyahu, S. Perioperative Escape from Dormancy of Spontaneous Micro-Metastases: A Role for Malignant Secretion of IL-6, IL-8, and VEGF, through Adrenergic and Prostaglandin Signaling. Brain Behav. Immun. 2023, 109, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recasens, A.; Munoz, L. Targeting Cancer Cell Dormancy. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 40, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrzejewski, S.; Winter, M.; Garcia, L.E.; Akinrinmade, O.; Marques, F.D.M.; Zacharioudakis, E.; Skwarska, A.; Aguirre-Ghiso, J.; Konopleva, M.; Zheng, G.; et al. Quiescent OXPHOS-High Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells That Persist after Chemotherapy Depend on BCL-XL for Survival. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, M.E.; Johnson, R.W. Breast Cancer Dormancy in Bone. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2019, 17, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayhew, V.; Omokehinde, T.; Johnson, R.W. Tumor Dormancy in Bone. Cancer Rep. 2020, 3, e1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cackowski, F.C.; Heath, E.I. Prostate Cancer Dormancy and Recurrence. Cancer Lett. 2022, 524, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieder, R. Stromal Co-Cultivation for Modeling Breast Cancer Dormancy in the Bone Marrow. Cancers 2022, 14, 3344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endo, H.; Inoue, M. Dormancy in Cancer. Cancer Sci. 2019, 110, 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balayan, V.; Guddati, A.K. Tumor Dormancy: Biologic and Therapeutic Implications. World J. Oncol. 2022, 13, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyles, J.; Puaux, A.-L.; Wang, X.; Toh, B.; Prakash, C.; Hong, M.; Tan, T.G.; Zheng, L.; Ong, L.C.; Jin, Y.; et al. Tumor Cells Disseminate Early, but Immunosurveillance Limits Metastatic Outgrowth, in a Mouse Model of Melanoma. J. Clin. Investig. 2010, 120, 2030–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, H.-Y.; Lee, H.-Y. Cellular Dormancy in Cancer: Mechanisms and Potential Targeting Strategies. Cancer Res. Treat. 2023, 55, 720–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre Ghiso, J.A.; Kovalski, K.; Ossowski, L. Tumor Dormancy Induced by Downregulation of Urokinase Receptor in Human Carcinoma Involves Integrin and MAPK Signaling. J. Cell Biol. 1999, 147, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-Ghiso, J.A.; Liu, D.; Mignatti, A.; Kovalski, K.; Ossowski, L. Urokinase Receptor and Fibronectin Regulate the ERK(MAPK) to P38(MAPK) Activity Ratios That Determine Carcinoma Cell Proliferation or Dormancy in Vivo. Mol. Biol. Cell 2001, 12, 863–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenza, G.L. Targeting HIF-1 for Cancer Therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2003, 3, 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.T.; Chai, R.C. Bone Niches in the Regulation of Tumour Cell Dormancy. J. Bone Oncol. 2024, 47, 100621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decker, A.M.; Jung, Y.; Cackowski, F.C.; Yumoto, K.; Wang, J.; Taichman, R.S. Sympathetic Signaling Reactivates Quiescent Disseminated Prostate Cancer Cells in the Bone Marrow. Mol. Cancer Res. 2017, 15, 1644–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Wang, Z.; Duan, N.; Zhu, G.; Schwarz, E.M.; Xie, C. Osteoblast-Osteoclast Interactions. Connect. Tissue Res. 2018, 59, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clézardin, P.; Coleman, R.; Puppo, M.; Ottewell, P.; Bonnelye, E.; Paycha, F.; Confavreux, C.B.; Holen, I. Bone Metastasis: Mechanisms, Therapies, and Biomarkers. Physiol. Rev. 2021, 101, 797–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.-M.; Zhang, X.-P.; Sun, X.; Liu, H.-C.; Yan, Y.-Y.; Wei, X.; Liang, Y.; Feng, Y.; Chen, Z.; Jia, Y.; et al. QSOX2-Mediated Disulfide Bond Modification Enhances Tumor Stemness and Chemoresistance by Activating TSC2/mTOR/c-Myc Feedback Loop in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e00597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, M.A.; McDonald, M.M.; Kovacic, N.; Hua Khoo, W.; Terry, R.L.; Down, J.; Kaplan, W.; Paton-Hough, J.; Fellows, C.; Pettitt, J.A.; et al. Osteoclasts Control Reactivation of Dormant Myeloma Cells by Remodelling the Endosteal Niche. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsky, L.; Cohen-Erez, I.; Bado, I.; Zhang, X.H.-F.; Vago, R. Review Old Bone, New Tricks. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 2022, 39, 727–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrer, J.; Taipaleenmäki, H. The Osteoblast in Regulation of Tumor Cell Dormancy and Bone Metastasis. J. Bone Oncol. 2024, 45, 100597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capulli, M.; Hristova, D.; Valbret, Z.; Carys, K.; Arjan, R.; Maurizi, A.; Masedu, F.; Cappariello, A.; Rucci, N.; Teti, A. Notch2 Pathway Mediates Breast Cancer Cellular Dormancy and Mobilisation in Bone and Contributes to Haematopoietic Stem Cell Mimicry. Br. J. Cancer 2019, 121, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, D.; Dai, Y.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Guo, W.; Ye, L.; Huang, S.; Chen, X.; Lai, Y.; Du, H.; et al. Wnt5a Induces and Maintains Prostate Cancer Cells Dormancy in Bone. J. Exp. Med. 2019, 216, 428–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhou, D.; Hong, Z. Sarcopenia and Cachexia: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Interventions. MedComm (2020) 2025, 6, e70030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Ngandiri, D.A.; Llerins Perez, M.; Wolf, A.; Wang, Y. The Molecular Brakes of Adipose Tissue Lipolysis. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 826314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maroni, P. Leptin, Adiponectin, and Sam68 in Bone Metastasis from Breast Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, E.V.; Edwards, C.M. Adipokines, Adiposity, and Bone Marrow Adipocytes: Dangerous Accomplices in Multiple Myeloma. J. Cell Physiol. 2018, 233, 9159–9166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorrab, A.; Pagano, A.; Ayed, K.; Chebil, M.; Derouiche, A.; Kovacic, H.; Gati, A. Leptin Promotes Prostate Cancer Proliferation and Migration by Stimulating STAT3 Pathway. Nutr. Cancer 2021, 73, 1217–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Du, J.; Shi, H.; Wang, S.; Yan, Y.; Xu, Q.; Zhou, S.; Zhao, Z.; Mu, Y.; Qian, C.; et al. Adiponectin Suppresses Tumor Growth of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma through Activating AMPK Signaling Pathway. J. Transl. Med. 2022, 20, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigro, E.; Daniele, A.; Salzillo, A.; Ragone, A.; Naviglio, S.; Sapio, L. AdipoRon and Other Adiponectin Receptor Agonists as Potential Candidates in Cancer Treatments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, E.V.; Suchacki, K.J.; Hocking, J.; Cartwright, R.; Sowman, A.; Gamez, B.; Lea, R.; Drake, M.T.; Cawthorn, W.P.; Edwards, C.M. Myeloma Cells Down-Regulate Adiponectin in Bone Marrow Adipocytes Via TNF-Alpha. J. Bone Min. Res. 2020, 35, 942–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudan, S.K.; Deshmukh, S.K.; Poosarla, T.; Holliday, N.P.; Dyess, D.L.; Singh, A.P.; Singh, S. Resistin: An Inflammatory Cytokine with Multi-Faceted Roles in Cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2020, 1874, 188419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muruganandan, S.; Ionescu, A.M.; Sinal, C.J. At the Crossroads of the Adipocyte and Osteoclast Differentiation Programs: Future Therapeutic Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lara, P.T.; Cuadrado, H.C.; Vermeer, M.; Núñez, N.; Urdínez, J.; Cecconi, V.; Attar, F.M.; Glarner, I.; Hiltbrunner, S.; Tugues, S.; et al. Abstract 2646: CD39+PD-1+CD8+ T Cells Mediate Metastatic Dormancy in Breast Cancer. Cancer Res. 2020, 80, 2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, A.L.; Guimaraes, J.C.; Auf Der Maur, P.; De Silva, D.; Trefny, M.P.; Okamoto, R.; Bruno, S.; Schmidt, A.; Mertz, K.; Volkmann, K.; et al. Hepatic Stellate Cells Suppress NK Cell-Sustained Breast Cancer Dormancy. Nature 2021, 594, 566–571, Erratum in Nature 2021, 600, E7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correia, A.L. Abstract SY31-02: Revisiting NK Cell Immunity to Prevent Metastasis. Cancer Res. 2022, 82, SY31-02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, A.L. Abstract PO005: Hepatic Stellate Cells Suppress NK Cell Sustained Breast Cancer Dormancy. Cancer Res. 2021, 81, PO005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haist, M.; Stege, H.; Grabbe, S.; Bros, M. The Functional Crosstalk between Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells and Regulatory T Cells within the Immunosuppressive Tumor Microenvironment. Cancers 2021, 13, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota Reyes, C.; Demir, E.; Çifcibaşı, K.; Istvanffy, R.; Friess, H.; Demir, I.E. Regulatory T Cells in Pancreatic Cancer: Of Mice and Men. Cancers 2022, 14, 4582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Wang, X.-F. Tumor Immune Evasion: Systemic Immunosuppressive Networks beyond the Local Microenvironment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2502597122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platten, M.; Nollen, E.A.A.; Röhrig, U.F.; Fallarino, F.; Opitz, C.A. Tryptophan Metabolism as a Common Therapeutic Target in Cancer, Neurodegeneration and Beyond. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019, 18, 379–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siret, C.; Collignon, A.; Silvy, F.; Robert, S.; Cheyrol, T.; André, P.; Rigot, V.; Iovanna, J.; Van De Pavert, S.; Lombardo, D.; et al. Deciphering the Crosstalk Between Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells and Regulatory T Cells in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Front. Immunol. 2020, 10, 3070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, C.; Liu, T.; Dai, X.; Bazhin, A.V. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells in Tumors: From Mechanisms to Antigen Specificity and Microenvironmental Regulation. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldmann, O.; Nwofor, O.V.; Chen, Q.; Medina, E. Mechanisms Underlying Immunosuppression by Regulatory Cells. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1328193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Sui, H.; Zhao, S.; Gao, X.; Su, Y.; Qu, P. Immunotherapy Targeting Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells (MDSCs) in Tumor Microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2021, 11, 585214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, B.; Cai, Y.; Chen, L.; Li, Z.; Li, X. Immunosuppressive MDSC and Treg Signatures Predict Prognosis and Therapeutic Response in Glioma. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 141, 112922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Yang, X.; Gao, Y.; Li, M.; Yang, H.; Liu, T.; Tang, H. Chronic Inflammation, Cancer Development and Immunotherapy. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1040163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, R.; Chen, N.; Li, L.; Du, N.; Bai, L.; Lv, Z.; Tian, H.; Cui, J. Mechanisms of Cancer Resistance to Immunotherapy. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Chen, W.; Xu, T.; Li, J.; Yu, J.; He, Y.; Qiu, S. The Impact of Aberrant Lipid Metabolism on the Immune Microenvironment of Gastric Cancer: A Mini Review. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1639823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, M.; Jia, Q. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells: Key Immunosuppressive Regulators and Therapeutic Targets in Cancer. Pathol.-Res. Pract. 2023, 248, 154711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cicco, P.; Ercolano, G.; Ianaro, A. The New Era of Cancer Immunotherapy: Targeting Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells to Overcome Immune Evasion. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrés, C.; Pérez De La Lastra, J.; Juan, C.; Plou, F.; Pérez-Lebeña, E. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells in Cancer and COVID-19 as Associated with Oxidative Stress. Vaccines 2023, 11, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Shi, H.; Zhang, B.; Ou, X.; Ma, Q.; Chen, Y.; Shu, P.; Li, D.; Wang, Y. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells as Immunosuppressive Regulators and Therapeutic Targets in Cancer. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordon, Y. NETs Awaken Sleeping Cancer Cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018, 18, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demkow, U. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs) in Cancer Invasion, Evasion and Metastasis. Cancers 2021, 13, 4495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wei, J.; He, W.; Ren, J. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Cancer. MedComm 2024, 5, e647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X.; Wang, X.; Yan, J.; Song, P.; Wang, Y.; Shang, C.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; et al. Bacterial Magnetosome-Hitchhiked Quick-Frozen Neutrophils for Targeted Destruction of Pre-Metastatic Niche and Prevention of Tumor Metastasis. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2023, 12, 2301343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Yin, C.; Tao, J. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Tumor Metastasis: Mechanisms, and Therapeutic Implications. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, H.; Yang, M.; Ji, Q.; Fu, S.; Pu, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X. Targeting Neutrophil Extracellular Traps: A Novel Antitumor Strategy. J. Immunol. Res. 2023, 2023, 5599660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masucci, M.T.; Minopoli, M.; Del Vecchio, S.; Carriero, M.V. The Emerging Role of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs) in Tumor Progression and Metastasis. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, J.; Sun, J.; Li, K. The Formation of NETs and Their Mechanism of Promoting Tumor Metastasis. J. Oncol. 2023, 2023, 7022337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortaz, E.; Alipoor, S.D.; Adcock, I.M.; Mumby, S.; Koenderman, L. Update on Neutrophil Function in Severe Inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Hu, H.; Tan, S.; Dong, Q.; Fan, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; He, J. The Role of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Cancer Progression, Metastasis and Therapy. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 11, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, J.; Yang, X.; Li, X.; Kong, J.; Qi, D.; Zhang, F.; Sun, B.; Liu, Y.; Liu, T. Carcinoma-Associated Fibroblast-Derived Lysyl Oxidase-Rich Extracellular Vesicles Mediate Collagen Crosslinking and Promote Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition via p-FAK/p-Paxillin/YAP Signaling. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2023, 15, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Martino, J.S.; Akhter, T.; Bravo-Cordero, J.J. Remodeling the ECM: Implications for Metastasis and Tumor Dormancy. Cancers 2021, 13, 4916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolillo, M.; Schinelli, S. Extracellular Matrix Alterations in Metastatic Processes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, J.; Abisoye-Ogunniyan, A.; Metcalf, K.J.; Werb, Z. Concepts of Extracellular Matrix Remodelling in Tumour Progression and Metastasis. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Xu, R. Roles of PLODs in Collagen Synthesis and Cancer Progression. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018, 6, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Martino, J.S.; Nobre, A.R.; Mondal, C.; Taha, I.; Farias, E.F.; Fertig, E.J.; Naba, A.; Aguirre-Ghiso, J.A.; Bravo-Cordero, J.J. A Tumor-Derived Type III Collagen-Rich ECM Niche Regulates Tumor Cell Dormancy. Nat. Cancer 2021, 3, 90–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Martino, D.; Bravo-Cordero, J.J. Collagens in Cancer: Structural Regulators and Guardians of Cancer Progression. Cancer Res. 2023, 83, 1386–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, L.E.; Hall, C.L.; Schwartz, A.D.; Parks, A.N.; Sparages, C.; Galarza, S.; Platt, M.O.; Mercurio, A.M.; Peyton, S.R. Tumor Cell–Organized Fibronectin Maintenance of a Dormant Breast Cancer Population. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaaz4157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkan, D.; Green, J.E.; Chambers, A.F. Extracellular Matrix: A Gatekeeper in the Transition from Dormancy to Metastatic Growth. Eur. J. Cancer 2010, 46, 1181–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Libring, S.; Shinde, A.; Chanda, M.K.; Nuru, M.; George, H.; Saleh, A.M.; Abdullah, A.; Kinzer-Ursem, T.L.; Calve, S.; Wendt, M.K.; et al. The Dynamic Relationship of Breast Cancer Cells and Fibroblasts in Fibronectin Accumulation at Primary and Metastatic Tumor Sites. Cancers 2020, 12, 1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.; Friedrichs, J.; Song, Y.H.; Werner, C.; Estroff, L.A.; Fischbach, C. Intrafibrillar, Bone-Mimetic Collagen Mineralization Regulates Breast Cancer Cell Adhesion and Migration. Biomaterials 2019, 198, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, B.; Zhao, Z.; Kong, W.; Han, C.; Shen, X.; Zhou, C. Biological Role of Matrix Stiffness in Tumor Growth and Treatment. J. Transl. Med. 2022, 20, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Luo, T.; Hua, H. Targeting Extracellular Matrix Stiffness and Mechanotransducers to Improve Cancer Therapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 15, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safaei, S.; Sajed, R.; Shariftabrizi, A.; Dorafshan, S.; Saeednejad Zanjani, L.; Dehghan Manshadi, M.; Madjd, Z.; Ghods, R. Tumor Matrix Stiffness Provides Fertile Soil for Cancer Stem Cells. Cancer Cell Int. 2023, 23, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, W.; Luo, Q.; Song, G. High Matrix Stiffness Accelerates Migration of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells through the Integrin Β1-Plectin-F-Actin Axis. BMC Biol. 2025, 23, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidi, H.; Ivaska, J. Every Step of the Way: Integrins in Cancer Progression and Metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2018, 18, 533–548, Erratum in Nat. Rev. Cancer 2019, 19, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, S.; Haga, H. Matrix Stiffness Contributes to Cancer Progression by Regulating Transcription Factors. Cancers 2022, 14, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Zhao, J.; Yu, S.; Mao, Z.; Gao, C.; Zhu, Y.; Mao, C.; Zheng, L. Untangling the Response of Bone Tumor Cells and Bone Forming Cells to Matrix Stiffness and Adhesion Ligand Density by Means of Hydrogels. Biomaterials 2019, 188, 130–143, Erratum in Biomaterials 2020, 231, 119663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levental, K.R.; Yu, H.; Kass, L.; Lakins, J.N.; Egeblad, M.; Erler, J.T.; Fong, S.F.T.; Csiszar, K.; Giaccia, A.; Weninger, W.; et al. Matrix Crosslinking Forces Tumor Progression by Enhancing Integrin Signaling. Cell 2009, 139, 891–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Bravo-Cordero, J.J. Regulation of Dormancy during Tumor Dissemination: The Role of the ECM. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2023, 42, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhshandeh, S.; Werner, C.; Fratzl, P.; Cipitria, A. Microenvironment-Mediated Cancer Dormancy: Insights from Metastability Theory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2111046118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobre, A.R.; Risson, E.; Singh, D.K.; Di Martino, J.S.; Cheung, J.F.; Wang, J.; Johnson, J.; Russnes, H.G.; Bravo-Cordero, J.J.; Birbrair, A.; et al. Bone Marrow NG2+/Nestin+ Mesenchymal Stem Cells Drive DTC Dormancy via TGF-Β2. Nat. Cancer 2021, 2, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linde, N.; Fluegen, G.; Aguirre-Ghiso, J.A. The Relationship Between Dormant Cancer Cells and Their Microenvironment. In Advances in Cancer Research; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; Volume 132, pp. 45–71. ISBN 978-0-12-804140-6. [Google Scholar]

- Sistigu, A.; Musella, M.; Galassi, C.; Vitale, I.; De Maria, R. Tuning Cancer Fate: Tumor Microenvironment’s Role in Cancer Stem Cell Quiescence and Reawakening. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahad, A.; Leng, F.; Ichise, H.; Schrom, E.; So, J.Y.; Sellner, C.; Gu, Y.; Wang, W.; Kieu, C.; Park, W.Y.; et al. Immune Niche Formation in Engineered Mouse Models Reveals Mechanisms of Tumor Dormancy. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, R.; Liu, M.; Xiang, X.; Xi, Z.; Xu, H. Osteoblasts and Osteoclasts: An Important Switch of Tumour Cell Dormancy during Bone Metastasis. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 41, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, N.M.; Summers, M.A.; McDonald, M.M. Tumor Cell Dormancy and Reactivation in Bone: Skeletal Biology and Therapeutic Opportunities. JBMR Plus 2019, 3, e10125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, S.; Scotto Di Carlo, F.; Gianfrancesco, F. The Osteoclast Traces the Route to Bone Tumors and Metastases. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 886305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liang, J.; Liu, P.; Wang, Q.; Liu, L.; Zhao, H. The RANK/RANKL/OPG System and Tumor Bone Metastasis: Potential Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategies. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 1063815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Luo, W.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ma, C.; Wu, Q.; Tian, P.; He, D.; Jia, Z.; Lv, X.; et al. IL-20RB Mediates Tumoral Response to Osteoclastic Niches and Promotes Bone Metastasis of Lung Cancer. J. Clin. Investig. 2022, 132, e157917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbruggen, A.S.K.; McNamara, L.M. Mechanoregulation May Drive Osteolysis during Bone Metastasis: A Finite Element Analysis of the Mechanical Environment within Bone Tissue during Bone Metastasis and Osteolytic Resorption. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2023, 138, 105662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sottnik, J.L.; Dai, J.; Zhang, H.; Campbell, B.; Keller, E.T. Tumor-Induced Pressure in the Bone Microenvironment Causes Osteocytes to Promote the Growth of Prostate Cancer Bone Metastases. Cancer Res. 2015, 75, 2151–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, J.; Chakraborty, S.; Maiti, T.K. Mechanical Stress-Induced Autophagic Response: A Cancer-Enabling Characteristic? Semin. Cancer Biol. 2020, 66, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu-Lee, L.-Y.; Yu, G.; Lee, Y.-C.; Lin, S.-C.; Pan, J.; Pan, T.; Yu, K.-J.; Liu, B.; Creighton, C.J.; Rodriguez-Canales, J.; et al. Osteoblast-Secreted Factors Mediate Dormancy of Metastatic Prostate Cancer in the Bone via Activation of the TGFβRIII–p38MAPK–pS249/T252RB Pathway. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 2911–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croucher, P.I.; McDonald, M.M.; Martin, T.J. Bone Metastasis: The Importance of the Neighbourhood. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2016, 16, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, A.W.; Grant, A.D.; Parker, S.S.; Hill, S.; Whalen, M.B.; Chakrabarti, J.; Harman, M.W.; Roman, M.R.; Forte, B.L.; Gowan, C.C.; et al. Breast Tumor Stiffness Instructs Bone Metastasis via Maintenance of Mechanical Conditioning. Cell Rep. 2021, 35, 109293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cambria, E.; Coughlin, M.F.; Floryan, M.A.; Offeddu, G.S.; Shelton, S.E.; Kamm, R.D. Linking Cell Mechanical Memory and Cancer Metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2024, 24, 216–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, K.; Lim, S.B.; Xiao, J.; Jokhun, D.S.; Shang, M.; Song, X.; Zhang, P.; Liang, L.; Low, B.C.; Shivashankar, G.V.; et al. Deleterious Mechanical Deformation Selects Mechanoresilient Cancer Cells with Enhanced Proliferation and Chemoresistance. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2201663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumbe, A.P. Vascular Niches for Disseminated Tumour Cells in Bone. J. Bone Oncol. 2016, 5, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, T.T.; Burness, M.L.; Sivan, A.; Warner, M.J.; Cheng, R.; Lee, C.H.; Olivere, L.; Comatas, K.; Magnani, J.; Kim Lyerly, H.; et al. Dormant Breast Cancer Micrometastases Reside in Specific Bone Marrow Niches That Regulate Their Transit to and from Bone. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016, 8, 340ra73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, R.K.H.; Rimes, J.S.; Capaldo, B.D.; Vaillant, F.; Mouchemore, K.A.; Pal, B.; Chen, Y.; Surgenor, E.; Murphy, A.J.; Anderson, R.L.; et al. Mammary Tumour Cells Remodel the Bone Marrow Vascular Microenvironment to Support Metastasis. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magar, A.G.; Morya, V.K.; Kwak, M.K.; Oh, J.U.; Noh, K.C. A Molecular Perspective on HIF-1α and Angiogenic Stimulator Networks and Their Role in Solid Tumors: An Update. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, T.; Hallis, S.P.; Kwak, M.-K. Hypoxia, Oxidative Stress, and the Interplay of HIFs and NRF2 Signaling in Cancer. Exp. Mol. Med. 2024, 56, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrer, A.; Roser, C.T.; El-Far, M.H.; Savanur, V.H.; Eljarrah, A.; Gergues, M.; Kra, J.A.; Etchegaray, J.-P.; Rameshwar, P. Hypoxia-Mediated Changes in Bone Marrow Microenvironment in Breast Cancer Dormancy. Cancer Lett. 2020, 488, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Xing, C.; Deng, Y.; Ye, C.; Peng, H. HIF-1α Signaling: Essential Roles in Tumorigenesis and Implications in Targeted Therapies. Genes Dis. 2024, 11, 234–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manuelli, V.; Pecorari, C.; Filomeni, G.; Zito, E. Regulation of Redox Signaling in HIF-1-dependent Tumor Angiogenesis. FEBS J. 2022, 289, 5413–5425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musleh Ud Din, S.; Streit, S.G.; Huynh, B.T.; Hana, C.; Abraham, A.-N.; Hussein, A. Therapeutic Targeting of Hypoxia-Inducible Factors in Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, S.; Roy, S.; Singh, M.; Kaithwas, G. Regulation of Transactivation at C-TAD Domain of HIF-1 α by Factor-Inhibiting HIF-1 α (FIH-1): A Potential Target for Therapeutic Intervention in Cancer. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 2407223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devignes, C.-S.; Aslan, Y.; Brenot, A.; Devillers, A.; Schepers, K.; Fabre, S.; Chou, J.; Casbon, A.-J.; Werb, Z.; Provot, S. HIF Signaling in Osteoblast-Lineage Cells Promotes Systemic Breast Cancer Growth and Metastasis in Mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E992–E1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, M.; Mondal, N.; Greco, T.M.; Wei, Y.; Spadazzi, C.; Lin, S.-C.; Zheng, H.; Cheung, C.; Magnani, J.L.; Lin, S.-H.; et al. Bone Vascular Niche E-Selectin Induces Mesenchymal–Epithelial Transition and Wnt Activation in Cancer Cells to Promote Bone Metastasis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2019, 21, 627–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storti, P.; Bolzoni, M.; Donofrio, G.; Airoldi, I.; Guasco, D.; Toscani, D.; Martella, E.; Lazzaretti, M.; Mancini, C.; Agnelli, L.; et al. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor (HIF)-1α Suppression in Myeloma Cells Blocks Tumoral Growth in Vivo Inhibiting Angiogenesis and Bone Destruction. Leukemia 2013, 27, 1697–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrengues, J.; Shields, M.A.; Ng, D.; Park, C.G.; Ambrico, A.; Poindexter, M.E.; Upadhyay, P.; Uyeminami, D.L.; Pommier, A.; Küttner, V.; et al. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Produced during Inflammation Awaken Dormant Cancer Cells in Mice. Science 2018, 361, eaao4227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Biermann, M.H.; Brauner, J.M.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Herrmann, M. New Insights into Neutrophil Extracellular Traps: Mechanisms of Formation and Role in Inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2016, 7, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alegre, M.-L. The Importance of Inflammation-Induced NETS. Am. J. Transplant. 2019, 19, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poto, R.; Cristinziano, L.; Modestino, L.; De Paulis, A.; Marone, G.; Loffredo, S.; Galdiero, M.R.; Varricchi, G. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps, Angiogenesis and Cancer. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egeblad, M. Abstract SY38-01: Inflammation-Induced Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs) Awaken Dormant Cancer in the Lung Microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, SY38-01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marie, J.C.; Bonnelye, E. Effects of Estrogens on Osteoimmunology: A Role in Bone Metastasis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 899104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, S.-H.; Chen, L.-R.; Chen, K.-H. Primary Osteoporosis Induced by Androgen and Estrogen Deficiency: The Molecular and Cellular Perspective on Pathophysiological Mechanisms and Treatments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, J.; Frye, J.; Whitman, S.; Thomas, A.; Ameneni, G.; Magee, A.; Cheng, J. Unraveling the Role of Estrogen Signaling in the Breast Cancer-Bone Connection. Physiology 2023, 38, 5793712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wang, H. Cellular Senescence in Bone. In Physiology; Heshmati, H.M., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022; Volume 15, ISBN 978-1-83969-050-1. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, J.N.; Frye, J.B.; Whitman, S.A.; Ehsani, S.; Ali, S.; Funk, J.L. Interrogating Estrogen Signaling Pathways in Human ER-Positive Breast Cancer Cells Forming Bone Metastases in Mice. Endocrinology 2024, 165, bqae038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisarro, M.; Conti, F. Salute ossea in corso di trattamento adiuvante anti-ormonale nella patologia oncologica: Rischio fratturativo e temporizzazione della terapia. L’Endocrinologo 2022, 23, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballinger, T.J.; Thompson, W.R.; Guise, T.A. The Bone–Muscle Connection in Breast Cancer: Implications and Therapeutic Strategies to Preserve Musculoskeletal Health. Breast Cancer Res. 2022, 24, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, C.N.; Canuas-Landero, V.; Theodoulou, E.; Muthana, M.; Wilson, C.; Ottewell, P. Oestrogen and Zoledronic Acid Driven Changes to the Bone and Immune Environments: Potential Mechanisms Underlying the Differential Anti-Tumour Effects of Zoledronic Acid in Pre- and Post-Menopausal Conditions. J. Bone Oncol. 2020, 25, 100317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conceição, F.; Sousa, D.M.; Tojal, S.; Lourenço, C.; Carvalho-Maia, C.; Estevão-Pereira, H.; Lobo, J.; Couto, M.; Rosenkilde, M.M.; Jerónimo, C.; et al. The Secretome of Parental and Bone Metastatic Breast Cancer Elicits Distinct Effects in Human Osteoclast Activity after Activation of Β2 Adrenergic Signaling. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, Y.; Xu, J.; Fan, C.; Zhang, B.; Feng, P.; Wang, Y.; Kong, Q. The Role of Sympathetic Nerves in Osteoporosis: A Narrative Review. Biomedicines 2022, 11, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.J.; Yun, D.H.; Jung, S.; Park, S.I. Abstract 2191: Alteration of Anti-Tumoral Immunity in the Pre-Metastatic Bone Microenvironment via Autonomic Nerve System Dysfunction. Cancer Res. 2022, 82, 2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conceição, F.; Sousa, D.M.; Loessberg-Zahl, J.; Vollertsen, A.R.; Neto, E.; Søe, K.; Paredes, J.; Leferink, A.; Lamghari, M. A Metastasis-on-a-Chip Approach to Explore the Sympathetic Modulation of Breast Cancer Bone Metastasis. Mater. Today Bio 2022, 13, 100219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurizi, A.; Rucci, N. The Osteoclast in Bone Metastasis: Player and Target. Cancers 2018, 10, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, H.; Chen, T.; Qiu, G.; Han, Y. The Emerging Role of Osteoclasts in the Treatment of Bone Metastases: Rationale and Recent Clinical Evidence. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1445025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elefteriou, F. Chronic Stress, Sympathetic Activation and Skeletal Metastasis of Breast Cancer Cells. BoneKEy Rep. 2015, 4, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elefteriou, F.; Campbell, P.J.; Madel, M.-B. Autonomic Innervation of the Skeleton. In Primer on the Autonomic Nervous System; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 257–261. ISBN 978-0-323-85492-4. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, G.; Esposito, M.; Kang, Y. Bone Metastasis and the Metastatic Niche. J. Mol. Med. 2015, 93, 1203–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Shen, Y.; Wang, F.; Lu, T.; Zhang, J. Sympathetic Nervous System in Tumor Progression and Metabolic Regulation: Mechanisms and Clinical Potential. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madel, M.-B.; Elefteriou, F. Mechanisms Supporting the Use of Beta-Blockers for the Management of Breast Cancer Bone Metastasis. Cancers 2021, 13, 2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conceição, F.; Sousa, D.M.; Paredes, J.; Lamghari, M. Sympathetic Activity in Breast Cancer and Metastasis: Partners in Crime. Bone Res. 2021, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnet Le Provost, K.; Kepp, O.; Kroemer, G.; Bezu, L. Trial Watch: Beta-Blockers in Cancer Therapy. Oncoimmunology 2023, 12, 2284486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Wang, Y.; Liu, F.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Ren, X.; Yuan, X. Impact of Beta Blockers on Cancer Neuroimmunology: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Survival Outcomes and Immune Modulation. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1635331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, X.; Li, P.; Qin, Y.; Mo, Y.; Chen, D. Beta-Adrenergic Receptor Blockers Improve Survival in Patients with Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Combined with Hypertension Undergoing Radiotherapy. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 10702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.E.; Chan, S.; Komorowski, A.S.; Cao, X.; Gao, Y.; Kshatri, K.; Desai, K.; Kuksis, M.; Rosen, M.; Sachdeva, A.; et al. The Impact of Beta Blockers on Survival in Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2025, 17, 1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsarelias, D.; Eriksson, H.; Mikiver, R.; Krakowski, I.; Nilsson, J.A.; Ny, L.; Olofsson Bagge, R. The Effect of Beta-Adrenergic Blocking Agents in Cutaneous Melanoma—A Nation-Wide Swedish Population-Based Retrospective Register Study. Cancers 2020, 12, 3228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Logbon, J.; Tarantola, L.; Williams, N.R.; Mehta, S.; Ahmed, A.; Davies, E.A. Does Propranolol Have a Role in Cancer Treatment? A Systematic Review of the Epidemiological and Clinical Trial Literature on Beta-Blockers. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 151, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searcy, M.B.; Johnson, R.W. Epigenetic Control of the Vicious Cycle. J. Bone Oncol. 2024, 44, 100524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, P.K.; Udoh, U.-A.; Sanabria, J.D.; Banerjee, M.; Smith, G.; Schade, M.S.; Sanabria, J.; Sodhi, K.; Pierre, S.; Xie, Z.; et al. The Role of Histone Acetylation-/Methylation-Mediated Apoptotic Gene Regulation in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Sun, J.; Liu, C.; Jiang, Y.; Hao, Y. Elevated H3K27me3 Levels Sensitize Osteosarcoma to Cisplatin. Clin. Epigenet. 2019, 11, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrer-Diaz, A.I.; Sinha, G.; Petryna, A.; Gonzalez-Bermejo, R.; Kenfack, Y.; Adetayo, O.; Patel, S.A.; Hooda-Nehra, A.; Rameshwar, P. Revealing Role of Epigenetic Modifiers and DNA Oxidation in Cell-Autonomous Regulation of Cancer Stem Cells. Cell Commun. Signal 2024, 22, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neophytou, C.M.; Kyriakou, T.-C.; Papageorgis, P. Mechanisms of Metastatic Tumor Dormancy and Implications for Cancer Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 6158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, C.M.; Johnson, R.W. Targeting Histone Modifications in Bone and Lung Metastatic Cancers. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2021, 19, 230–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomathi, K.; Akshaya, N.; Srinaath, N.; Rohini, M.; Selvamurugan, N. Histone Acetyl Transferases and Their Epigenetic Impact on Bone Remodeling. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 170, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Deng, Y.; Min, Z.; Li, C.; Zhao, Z.; Yi, J.; Jing, D. Unlocking the Epigenetic Symphony: Histone Acetylation Orchestration in Bone Remodeling and Diseases. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2025, 21, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.; Sultana, A.; Abdullah, K.M.; Pothuraju, R.; Nasser, M.W.; Batra, S.K.; Siddiqui, J.A. Epigenetic Regulation of Bone Remodeling and Bone Metastasis. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 154, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tigu, A.B.; Ivancuta, A.; Uhl, A.; Sabo, A.C.; Nistor, M.; Mureșan, X.-M.; Cenariu, D.; Timis, T.; Diculescu, D.; Gulei, D. Epigenetic Therapies in Melanoma—Targeting DNA Methylation and Histone Modification. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venit, T.; Sapkota, O.; Abdrabou, W.S.; Loganathan, P.; Pasricha, R.; Mahmood, S.R.; El Said, N.H.; Sherif, S.; Thomas, S.; Abdelrazig, S.; et al. Positive Regulation of Oxidative Phosphorylation by Nuclear Myosin 1 Protects Cells from Metabolic Reprogramming and Tumorigenesis in Mice. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6328, Erratum in Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uslu, C.; Kapan, E.; Lyakhovich, A. Cancer Resistance and Metastasis Are Maintained through Oxidative Phosphorylation. Cancer Lett. 2024, 587, 216705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Zhang, H.; Gao, P. Metabolic Reprogramming and Epigenetic Modifications on the Path to Cancer. Protein Cell 2022, 13, 877–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sciacovelli, M.; Frezza, C. Metabolic Reprogramming and Epithelial-to-mesenchymal Transition in Cancer. FEBS J. 2017, 284, 3132–3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.P.; Sabini, E.; Beigel, K.; Lanzolla, G.; Laslow, B.; Wang, D.; Merceron, C.; Giaccia, A.; Long, F.; Taylor, D.; et al. HIF1 Activation Safeguards Cortical Bone Formation against Impaired Oxidative Phosphorylation. JCI Insight 2024, 9, e182330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Eu, J.Q.; Kong, L.R.; Wang, L.; Lim, Y.C.; Goh, B.C.; Wong, A.L.A. Targeting Metabolism in Cancer Cells and the Tumour Microenvironment for Cancer Therapy. Molecules 2020, 25, 4831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z. Crosstalk between Oxidative Phosphorylation and Immune Escape in Cancer: A New Concept of Therapeutic Targets Selection. Cell Oncol. 2023, 46, 847–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlome, S.; Berry, C.C. Recent Insights into the Effects of Metabolism on Breast Cancer Cell Dormancy. Br. J. Cancer 2022, 127, 1385–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Cheng, C.; Tan, Z.; Li, N.; Tang, M.; Yang, L.; Cao, Y. Emerging Roles of Lipid Metabolism in Cancer Metastasis. Mol. Cancer 2017, 16, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Song, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Ye, Z.; Zhao, J.; Wu, Y.; Tang, J.; Yao, M. Metabolic Reprogramming in Tumor Immune Microenvironment: Impact on Immune Cell Function and Therapeutic Implications. Cancer Lett. 2024, 597, 217076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Lu, M.; Jia, D.; Ma, J.; Ben-Jacob, E.; Levine, H.; Kaipparettu, B.A.; Onuchic, J.N. Modeling the Genetic Regulation of Cancer Metabolism: Interplay between Glycolysis and Oxidative Phosphorylation. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 1564–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldogazieva, N.T.; Mokhosoev, I.M.; Terentiev, A.A. Metabolic Heterogeneity of Cancer Cells: An Interplay between HIF-1, GLUTs, and AMPK. Cancers 2020, 12, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidrich, I.; Deitert, B.; Werner, S.; Pantel, K. Liquid Biopsy for Monitoring of Tumor Dormancy and Early Detection of Disease Recurrence in Solid Tumors. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2023, 42, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, R.; Roy, A.; Tokumaru, Y.; Gandhi, S.; Asaoka, M.; Oshi, M.; Yan, L.; Ishikawa, T.; Takabe, K. NR2F1, a Tumor Dormancy Marker, Is Expressed Predominantly in Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts and Is Associated with Suppressed Breast Cancer Cell Proliferation. Cancers 2022, 14, 2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drescher, F.; Juárez, P.; Arellano, D.L.; Serafín-Higuera, N.; Olvera-Rodriguez, F.; Jiménez, S.; Licea-Navarro, A.F.; Fournier, P.G.J. TIE2 Induces Breast Cancer Cell Dormancy and Inhibits the Development of Osteolytic Bone Metastases. Cancers 2020, 12, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owen, K.L.; Gearing, L.J.; Zanker, D.J.; Brockwell, N.K.; Khoo, W.H.; Roden, D.L.; Cmero, M.; Mangiola, S.; Hong, M.K.; Spurling, A.J.; et al. Prostate Cancer Cell-intrinsic Interferon Signaling Regulates Dormancy and Metastatic Outgrowth in Bone. EMBO Rep. 2020, 21, e50162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Su, S.; Xing, J.; Liu, K.; Zhao, Y.; Stangis, M.; Jacho, D.P.; Yildirim-Ayan, E.D.; Gatto-Weis, C.M.; Chen, B.; et al. Tumor Removal Limits Prostate Cancer Cell Dissemination in Bone and Osteoblasts Induce Cancer Cell Dormancy through Focal Adhesion Kinase. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 42, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.K.; Patel, V.G.; Oh, W.K.; Aguirre-Ghiso, J.A. Prostate Cancer Dormancy and Reactivation in Bone Marrow. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, L.; Moore, D.; Ovadia, E.M.; Swedzinski, S.L.; Cossette, T.; Sikes, R.A.; Van Golen, K.; Kloxin, A.M. Dynamic Bioinspired Coculture Model for Probing ER+ Breast Cancer Dormancy in the Bone Marrow Niche. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eade3186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.Y.; Kamalanathan, K.J.; Galeano-Garces, C.; Konety, B.R.; Antonarakis, E.S.; Parthasarathy, J.; Hong, J.; Drake, J.M. Dissemination of Circulating Tumor Cells in Breast and Prostate Cancer: Implications for Early Detection. Endocrinology 2024, 165, bqae022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drago-Garcia, D.; Giri, S.; Chatterjee, R.; Simoni-Nieves, A.; Abedrabbo, M.; Genna, A.; Rios, M.L.U.; Lindzen, M.; Sekar, A.; Gupta, N.; et al. Re-Epithelialization of Cancer Cells Increases Autophagy and DNA Damage: Implications for Breast Cancer Dormancy and Relapse. Sci. Signal. 2025, 18, eado3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufail, M.; Jiang, C.-H.; Li, N. Tumor Dormancy and Relapse: Understanding the Molecular Mechanisms of Cancer Recurrence. Mil. Med. Res. 2025, 12, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, L.; Wang, J.; Jiang, W.G.; Song, X.; Ye, L. Molecular Mechanism of Bone Metastasis in Breast Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1401113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador, F.; Llorente, A.; Gomis, R.R. From Latency to Overt Bone Metastasis in Breast Cancer: Potential for Treatment and Prevention. J. Pathol. 2019, 249, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, J.; Fock, V.; Aryee, D.N.T.; Kovar, H. Mechanisms, Diagnosis and Treatment of Bone Metastases. Cells 2021, 10, 2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Lei, J.; Mou, H.; Zhang, W.; Jin, L.; Lu, S.; Yinwang, E.; Xue, Y.; Shao, Z.; Chen, T.; et al. Multiple Influence of Immune Cells in the Bone Metastatic Cancer Microenvironment on Tumors. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1335366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Xia, F.; Wei, Y.; Wei, X. Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Management of Cancer Bone Metastasis. Bone Res. 2020, 8, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ring, A.; Spataro, M.; Wicki, A.; Aceto, N. Clinical and Biological Aspects of Disseminated Tumor Cells and Dormancy in Breast Cancer. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 929893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomis, R.R.; Gawrzak, S. Tumor Cell Dormancy. Mol. Oncol. 2017, 11, 62–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quayle, L.A.; Spicer, A.; Ottewell, P.D.; Holen, I. Transcriptomic Profiling Reveals Novel Candidate Genes and Signalling Programs in Breast Cancer Quiescence and Dormancy. Cancers 2021, 13, 3922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weston, W.A.; Barr, A.R. A Cell Cycle Centric View of Tumour Dormancy. Br. J. Cancer 2023, 129, 1535–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chéry, L.; Lam, H.-M.; Coleman, I.; Lakely, B.; Coleman, R.; Larson, S.; Aguirre-Ghiso, J.A.; Xia, J.; Gulati, R.; Nelson, P.S.; et al. Characterization of Single Disseminated Prostate Cancer Cells Reveals Tumor Cell Heterogeneity and Identifies Dormancy Associated Pathways. Oncotarget 2014, 5, 9939–9951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drapela, S.; Megino-Luque, C.; Rad, R.C.; Raizada, D.; Sarigul, N.; Ilter, D.; Czerniecki, B.J.; Bravo-Cordero, J.J.; Gomes, A.P. Abstract A013: Microenvironment Driven Dynamic Deposition of Histone H3.3 Controls Entry and Exit from Dormancy in Disseminated Cancer Cells. Cancer Res. 2024, 84, A013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Cimino, P.J.; Gouin, K.H.; Grzelak, C.A.; Barrett, A.; Lim, A.R.; Long, A.; Weaver, S.; Saldin, L.T.; Uzamere, A.; et al. Astrocytic Laminin-211 Drives Disseminated Breast Tumor Cell Dormancy in Brain. Nat. Cancer 2021, 3, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Risson, E.; Nobre, A.R.; Maguer-Satta, V.; Aguirre-Ghiso, J.A. The Current Paradigm and Challenges Ahead for the Dormancy of Disseminated Tumor Cells. Nat. Cancer 2020, 1, 672–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dianat-Moghadam, H.; Azizi, M.; Eslami-S, Z.; Cortés-Hernández, L.E.; Heidarifard, M.; Nouri, M.; Alix-Panabières, C. The Role of Circulating Tumor Cells in the Metastatic Cascade: Biology, Technical Challenges, and Clinical Relevance. Cancers 2020, 12, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boral, D.; Liu, H.N.; Kenney, S.R.; Marchetti, D. Molecular Interplay between Dormant Bone Marrow-Resident Cells (BMRCs) and CTCs in Breast Cancer. Cancers 2020, 12, 1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Hu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, C.; Shen, L.; Shuai, B. Current Comprehensive Understanding of Denosumab (the RANKL Neutralizing Antibody) in the Treatment of Bone Metastasis of Malignant Tumors, Including Pharmacological Mechanism and Clinical Trials. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1133828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, S.A.; Qudrat, S.; Zubair, H.; Iqbal, Z.; Gulzar, B.; Aziz, S.; Inayat, A.; Safi, D.; Kamran, A. Role of Osteoclast Inhibitors in Prostate Cancer Bone Metastasis; a Narrative Review. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 2025, 31, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.R.; Brungs, D.; Pavlakis, N. Osteoclast Inhibitors to Prevent Bone Metastases in Men with High-Risk, Non-Metastatic Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0191455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.E.; Coleman, R.E. Denosumab in Patients with Cancer—A Surgical Strike against the Osteoclast. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 9, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Moos, R.; Costa, L.; Gonzalez-Suarez, E.; Terpos, E.; Niepel, D.; Body, J. Management of Bone Health in Solid Tumours: From Bisphosphonates to a Monoclonal Antibody. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2019, 76, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguchi, T.; Sakamoto, A.; Murotani, Y.; Murata, K.; Hirata, M.; Yamada, Y.; Toguchida, J.; Matsuda, S. Inhibition of RANKL Expression in Osteocyte-like Differentiated Tumor Cells in Giant Cell Tumor of Bone After Denosumab Treatment. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2023, 71, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Li, F.; Dang, L.; Liang, C.; Lu, A.; Zhang, G. RANKL/RANK System-Based Mechanism for Breast Cancer Bone Metastasis and Related Therapeutic Strategies. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, S. Research Progression in the Mechanism of Bone Metastasis and Bone-Targeted Drugs in Prostate Cancer. Ann. Urol. Oncol. 2024, 7, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terpos, E.; Raje, N.; Croucher, P.; Garcia-Sanz, R.; Leleu, X.; Pasteiner, W.; Wang, Y.; Glennane, A.; Canon, J.; Pawlyn, C. Denosumab Compared with Zoledronic Acid on PFS in Multiple Myeloma: Exploratory Results of an International Phase 3 Study. Blood Adv. 2021, 5, 725–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todenhöfer, T.; Stenzl, A.; Hofbauer, L.C.; Rachner, T.D. Targeting Bone Metabolism in Patients with Advanced Prostate Cancer: Current Options and Controversies. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2015, 2015, 838202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaper-Gerhardt, K.; Gutzmer, R.; Angela, Y.; Zimmer, L.; Livingstone, E.; Schadendorf, D.; Hassel, J.C.; Weishaupt, C.; Remes, B.; Kubat, L.; et al. The RANKL Inhibitor Denosumab in Combination with Dual Checkpoint Inhibition Is Associated with Increased CXCL-13 Serum Concentrations. Eur. J. Cancer 2024, 202, 113984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xu, H.-Y.; Duan, J.-C.; Wang, Z.-J.; Zhong, J.; Cui, Y.-Y.; Fang, Q.; Lei, S.-Y.; Wang, Y. P2.06-02 DEnosumab plus PD-1 Inhibitor for MAINtenance Therapy of Advanced KRAS-Mutant NSCLC—A Prospective, Single-Arm, Phase II Study (DEMAIN). J. Thorac. Oncol. 2023, 18, S317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongiovanni, A.; Foca, F.; Menis, J.; Stucci, S.L.; Artioli, F.; Guadalupi, V.; Forcignanò, M.R.; Fantini, M.; Recine, F.; Mercatali, L.; et al. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors With or Without Bone-Targeted Therapy in NSCLC Patients with Bone Metastases and Prognostic Significance of Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 697298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.-S.; Lei, S.-Y.; Li, J.-L.; Xing, P.-Y.; Hao, X.-Z.; Xu, F.; Xu, H.-Y.; Wang, Y. Efficacy and Safety of Concomitant Immunotherapy and Denosumab in Patients with Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Carrying Bone Metastases: A Retrospective Chart Review. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 908436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asano, Y.; Yamamoto, N.; Demura, S.; Hayashi, K.; Takeuchi, A.; Kato, S.; Miwa, S.; Igarashi, K.; Higuchi, T.; Taniguchi, Y.; et al. Combination Therapy with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors and Denosumab Improves Clinical Outcomes in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer with Bone Metastases. Lung Cancer 2024, 193, 107858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, S.; Clézardin, P. Bone-Targeted Therapies in Cancer-Induced Bone Disease. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2018, 102, 227–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Carrigan, B.; Wong, M.H.; Willson, M.L.; Stockler, M.R.; Pavlakis, N.; Goodwin, A. Bisphosphonates and Other Bone Agents for Breast Cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 10, CD003474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville-Webbe, H.L.; Coleman, R.E. Bisphosphonates and RANK Ligand Inhibitors for the Treatment and Prevention of Metastatic Bone Disease. Eur. J. Cancer 2010, 46, 1211–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mundy, G.R. Mechanisms of Bone Metastasis. Cancer 1997, 80, 1546–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aft, R.; Perez, J.-R.; Raje, N.; Hirsh, V.; Saad, F. Could Targeting Bone Delay Cancer Progression? Potential Mechanisms of Action of Bisphosphonates. Crit. Rev. Oncol./Hematol. 2012, 82, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnant, M.; Clézardin, P. Direct and Indirect Anticancer Activity of Bisphosphonates: A Brief Review of Published Literature. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2012, 38, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beuzeboc, P.; Scholl, S. Prevention of Bone Metastases in Breast Cancer Patients. Therapeutic Perspectives. J. Clin. Med. 2014, 3, 521–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.N.; Frye, J.B.; Whitman, S.A.; Funk, J.L. Abstract 4207: Zoledronic Acid Reduces Quiescent Bone-Disseminated Human ER+ Breast Cancer Tumor Cell Burden and Estrogen-Responsiveness in a Pre-Clinical Model. Cancer Res. 2024, 84, 4207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clezardin, P.; Fournier, P.; Boissier, S.; Peyruchaud, O. In Vitro and In Vivo Antitumor Effects of Bisphosphonates. Curr. Med. Chem. 2003, 10, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.R.; Guenther, A. The Backbone of Progress—Preclinical Studies and Innovations with Zoledronic Acid. Crit. Rev. Oncol./Hematol. 2011, 77, S3–S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnant, M.; Dubsky, P.; Hadji, P. Bisphosphonates: Prevention of Bone Metastases in Breast Cancer. In Prevention of Bone Metastases; Recent Results in Cancer Research; Joerger, M., Gnant, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 192, pp. 65–91. ISBN 978-3-642-21891-0. [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa, T. Differences between Zoledronic Acid and Denosumab for Breast Cancer Treatment. J. Bone Min. Metab. 2023, 41, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwamoto, J.; Sato, Y.; Takeda, T.; Matsumoto, H. Comparative Review of Denosumab Versus Zoledronic Acid for the Reduction or Delay of Serious Complications Associated with Bone Metastases of Breast Cancer. Clin. Med. Rev. Oncol. 2010, 2, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabr, A.G.; Badawy, S.A.; Abdalla, A.Z.; Zaki, E.M.; Mohammed, A.H. Efficacy and Safety of Denosumab Versus Zoledronic Acid in Suppressing Bone Metastases of Breast Cancer. Egypt. J. Hosp. Med. 2022, 87, 1376–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, F.N.; Mohammad, K.S. Immunotherapy in the Battle Against Bone Metastases: Mechanisms and Emerging Treatments. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Tan, X.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, H.; Yuan, H. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Osteosarcoma: A Hopeful and Challenging Future. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1031527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Fang, H.; Yang, X.; Zeng, X. Analysis of Combination Therapy of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Osteosarcoma. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 847621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafaei, S.; Zekiy, A.O.; Khanamir, R.A.; Zaman, B.A.; Ghayourvahdat, A.; Azimizonuzi, H.; Zamani, M. Combination Therapy with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors (ICIs); a New Frontier. Cancer Cell Int. 2022, 22, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjili, M.H. The Premise of Personalized Immunotherapy for Cancer Dormancy. Oncogene 2020, 39, 4323–4330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damen, M.P.F.; Van Rheenen, J.; Scheele, C.L.G.J. Targeting Dormant Tumor Cells to Prevent Cancer Recurrence. FEBS J. 2021, 288, 6286–6303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer, S.; Reed, D.R.; Ihnat, M.; Hurst, R.E.; Warshawsky, D.; Barkan, D. Innovative Approaches in the Battle Against Cancer Recurrence: Novel Strategies to Combat Dormant Disseminated Tumor Cells. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 659963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdizadeh, R.; Shariatpanahi, S.P.; Goliaei, B.; Rüegg, C. Targeting Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells in Combination with Tumor Cell Vaccination Predicts Anti-Tumor Immunity and Breast Cancer Dormancy: An in Silico Experiment. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haq, A.T.A.; Yang, P.-P.; Jin, C.; Shih, J.-H.; Chen, L.-M.; Tseng, H.-Y.; Chen, Y.-A.; Weng, Y.-S.; Wang, L.-H.; Snyder, M.P.; et al. Immunotherapeutic IL-6R and Targeting the MCT-1/IL-6/CXCL7/PD-L1 Circuit Prevent Relapse and Metastasis of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Theranostics 2024, 14, 2167–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teleanu, R.I.; Chircov, C.; Grumezescu, A.M.; Teleanu, D.M. Tumor Angiogenesis and Anti-Angiogenic Strategies for Cancer Treatment. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 9, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olejarz, W.; Kubiak-Tomaszewska, G.; Chrzanowska, A.; Lorenc, T. Exosomes in Angiogenesis and Anti-Angiogenic Therapy in Cancers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.-L.; Chen, H.-H.; Zheng, L.-L.; Sun, L.-P.; Shi, L. Angiogenic Signaling Pathways and Anti-Angiogenic Therapy for Cancer. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabi, M.; Mousa, S. The Role of Angiogenesis in Cancer Treatment. Biomedicines 2017, 5, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Fu, Y.; Xie, Q.; Zhu, B.; Wang, J.; Zhang, B. Anti-Angiogenic Agents in Combination with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: A Promising Strategy for Cancer Treatment. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Shi, Y.; Jin, Z.; He, J. Advances in Tumor Vascular Growth Inhibition. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2024, 26, 2084–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayasin, Y.P.; Osinnikova, M.N.; Kharisova, C.B.; Kitaeva, K.V.; Filin, I.Y.; Gorodilova, A.V.; Kutovoi, G.I.; Solovyeva, V.V.; Golubev, A.I.; Rizvanov, A.A. Extracellular Matrix as a Target in Melanoma Therapy: From Hypothesis to Clinical Trials. Cells 2024, 13, 1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorusso, G.; Rüegg, C.; Kuonen, F. Targeting the Extra-Cellular Matrix—Tumor Cell Crosstalk for Anti-Cancer Therapy: Emerging Alternatives to Integrin Inhibitors. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weis, S.M.; Cheresh, D.A. V Integrins in Angiogenesis and Cancer. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2011, 1, a006478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.-R.; Zhao, J.-T.; Xie, Z.-Z. Integrin-Mediated Cancer Progression as a Specific Target in Clinical Therapy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 155, 113745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, M.; Sawada, K.; Kimura, T. Potential of Integrin Inhibitors for Treating Ovarian Cancer: A Literature Review. Cancers 2017, 9, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prakash, J.; Shaked, Y. The Interplay between Extracellular Matrix Remodeling and Cancer Therapeutics. Cancer Discov. 2024, 14, 1375–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaiah, M.J.; Tangutur, A.D.; Manyam, R.R. Epigenetic Modulation and Understanding of HDAC Inhibitors in Cancer Therapy. Life Sci. 2021, 277, 119504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhan, Z.; Gan, L.; Bai, O. Mechanisms of HDACs in Cancer Development. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1529239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newbold, A.; Falkenberg, K.J.; Prince, H.M.; Johnstone, R.W. How Do Tumor Cells Respond to HDAC Inhibition? FEBS J. 2016, 283, 4032–4046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Tian, Y.; Zhu, W.-G. The Roles of Histone Deacetylases and Their Inhibitors in Cancer Therapy. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 576946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wawruszak, A.; Kalafut, J.; Okon, E.; Czapinski, J.; Halasa, M.; Przybyszewska, A.; Miziak, P.; Okla, K.; Rivero-Muller, A.; Stepulak, A. Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors and Phenotypical Transformation of Cancer Cells. Cancers 2019, 11, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckschlager, T.; Plch, J.; Stiborova, M.; Hrabeta, J. Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors as Anticancer Drugs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, F.; Lauffenburger, D.; Friedl, P. Towards Targeting of Shared Mechanisms of Cancer Metastasis and Therapy Resistance. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2022, 22, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goen, A.E.; Marotti, J.D.; Miller, T.W. Abstract 5098: Targeting Fatty Acid Dependency in Hormone Receptor Positive HER2 Negative Drug Tolerant Persister Bone Metastases. Cancer Res. 2025, 85, 5098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Fahrmann, J.F.; Lee, H.; Li, Y.-J.; Tripathi, S.C.; Yue, C.; Zhang, C.; Lifshitz, V.; Song, J.; Yuan, Y.; et al. JAK/STAT3-Regulated Fatty Acid β-Oxidation Is Critical for Breast Cancer Stem Cell Self-Renewal and Chemoresistance. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 136–150.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, S.; Faouzi, S.; Souquere, S.; Roy, S.; Routier, E.; Libenciuc, C.; André, F.; Pierron, G.; Scoazec, J.-Y.; Robert, C. Melanoma Persister Cells Are Tolerant to BRAF/MEK Inhibitors Via ACOX1-Mediated Fatty Acid Oxidation. SSRN J. 2020, 33, 108421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, F.; Al-Khami, A.A.; Wyczechowska, D.; Hernandez, C.; Zheng, L.; Reiss, K.; Valle, L.D.; Trillo-Tinoco, J.; Maj, T.; Zou, W.; et al. Inhibition of Fatty Acid Oxidation Modulates Immunosuppressive Functions of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells and Enhances Cancer Therapies. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2015, 3, 1236–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samudio, I.; Harmancey, R.; Fiegl, M.; Kantarjian, H.; Konopleva, M.; Korchin, B.; Kaluarachchi, K.; Bornmann, W.; Duvvuri, S.; Taegtmeyer, H.; et al. Pharmacologic Inhibition of Fatty Acid Oxidation Sensitizes Human Leukemia Cells to Apoptosis Induction. J. Clin. Investig. 2010, 120, 142–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Choi, W.; Ham, W.; Hong, W.; Kim, C.-Y.; Lee, H.; Kim, S.-Y. Abstract 1544: Fatty Acid Oxidation Inhibition with Anti-Cancer Agents Abrogated Tumor Growth in a Melanoma Cancer Model. Cancer Res. 2025, 85, 1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.M.; Kim, C.Y.; Ham, W.; Kang, J.H.; Kang, M.; Hong, W.; Park, J.H.; Choi, W.; Kim, S.Y. Abstract 1697: Chemotherapy Combined with Fatty Acid Oxidation Inhibition Completely Regressed Tumor Growth in a Pancreatic Cancer Model. Cancer Res. 2025, 85, 1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xiang, Q.; Wu, S.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, H.; Xiao, B.; Li, L. Comprehensive Characterization of Fatty Acid Oxidation in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Focus on Biological Roles and Drug Modulation. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2025, 991, 177343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Park, S.; Lee, J.; Lee, C.; Kang, H.; Kang, J.; Lee, J.S.; Shin, E.; Youn, H.; Youn, B. Lipid Metabolism in Cancer Stem Cells: Reprogramming, Mechanisms, Crosstalk, and Therapeutic Approaches. Cell Oncol. 2025, 48, 1181–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinnah, A.H.; Zacks, B.C.; Gwam, C.U.; Kerr, B.A. Emerging and Established Models of Bone Metastasis. Cancers 2018, 10, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamamouna, V.; Pavlou, E.; Neophytou, C.M.; Papageorgis, P.; Costeas, P. Regulation of Metastatic Tumor Dormancy and Emerging Opportunities for Therapeutic Intervention. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Q.; Khoo, W.H.; Corr, A.P.; Phan, T.G.; Croucher, P.I.; Stewart, S.A. Gene Expression Predicts Dormant Metastatic Breast Cancer Cell Phenotype. Breast Cancer Res. 2022, 24, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Tang, M. Advances in the Study of Biomarkers Related to Bone Metastasis in Breast Cancer. Br. J. Radiol. 2023, 96, 20230117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Maintenance | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Process | Molecular Pathway | Cellular Component | Key Mediators |

| p38/ERK Balance | ↑p38, ↓ERK | Extracellular matrix | p38MAPK, ERK |

| Hypoxia | ↑TGF-β2, ↑p27 | - | TGF-β2, p27 |

| Direct Interactions | TAM receptor signaling | DTC, Osteoblasts | AXL, GAS6 |

| Paracrine | BMP signaling | Osteoblasts | BMP-7 |

| - | Notch | SNO, DTC | Jagged-1, Notch |

| Wnt signaling | Ror2/SIAH | SNO | Wnt5a |

| Metabolic reprogramming | Phosphorylation of HSL and Perlipin A | BMA | FFA |

| Adipokine secretion | PI3K/AKT, JAK/STAT, NFκB | BMA | Leptin, adiponectin, resistin |

| Immune surveillance | - | CD8+ T-cells, NK-cells | IFN-γ, TNF-α |

| ECM remodeling | Integrin-mediated adhesion | ECM | Fibronectin |

| Mechanotransduction | STAT1 | ECM | Type III collagen |

| Angiogenic factors | SDF-1/CXCR4 | Endothelial cells | Thrombospondin-1 |

| Epigenetic modification | Histone methylation | DTC | EZH2, H3K4 methyltransferases |

| Escape | |||

| Direct Interactions | TAM receptor signaling | DTC, Osteoblasts | TYRO, MERTK, GAS6 |

| Neuronal Signaling | β2-adrenergic receptor | Neurons, DTC | Norepinephrine |

| Bone Resorption | - | Osteoclasts | TGF-β1, IGF-1, Ca++ |

| Immunosuppression | Enzymatic amino acid depletion Nitration of TCR Inducing apoptosis | MDSC, TAM, Treg | iNOS, Arg1 ROS, RNS, peroxynitrite PD-L1 |

| ECM remodeling | Collagen crosslinking Degradation of fibronectin | Fibroblasts | LOX MMP |

| Hypoxia | Angiogenesis | Endothelial cells | HIF-1α, VEGF, FGF, PDGF |

| Aging | FAK, ERK, MLCK, YAP | Neutrophils, ECM | Laminin, MMP, NET |

| Hormonal depletion | Promotion of osteoclastogenesis through OPG/RANK/RANKL | Osteoclasts, osteoblasts | IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α |

| Epigenetic modifications | Histone acetylation and demethylation | DTC | BRD4 |

| Therapeutic Strategy | Mechanistic Rationale | Translational Challenges | Clinical Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Osteoclast Inhibitors (Denosumab) | Blocks RANKL–RANK, reduces resorption. | Limited biomarkers; unclear timing. | ONJ risk; no direct dormancy data. |

| Bisphosphonates | Induce osteoclast apoptosis. | Variable patient response. | Renal toxicity; limited survival benefit. |

| Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors | Restore T-cell surveillance. | Dormant cells low immunogenicity. | Immune toxicities; modest bone response. |

| ICI + Osteoclast Inhibitors | Dual immune + niche targeting. | Sparse prospective data. | Toxicity; unclear survival benefit. |

| MDSC-Targeting Agents | Reverse immunosuppression. | Pathway redundancy. | Inconsistent clinical results. |

| NET Inhibitors (PAD4i, DNase) | Prevent ECM remodeling signals. | Infection risk; limited validation. | No approved agents. |

| Anti-Angiogenic Therapy | Blocks angiogenic switch. | Dormant cells near stable vessels. | Resistance; limited efficacy in bone. |

| Integrin/FAK Inhibitors | Block mechanotransduction. | Redundant pathways. | Off-target toxicity. |

| Epigenetic Modifiers | Alter chromatin states. | Broad effects; risk of activation. | Hematologic toxicity. |

| Metabolic Modulators | Target OXPHOS/glycolysis. | Metabolic plasticity. | Tolerance issues. |

| β-Blockers (SNS Modulation) | Reduce NE-driven reactivation. | Context-dependent effects. | Inconsistent clinical benefit. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bakir, M.; Dabaliz, A.; Dawalibi, A.; Mohammad, K.S. Microenvironmental and Molecular Pathways Driving Dormancy Escape in Bone Metastases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11893. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411893

Bakir M, Dabaliz A, Dawalibi A, Mohammad KS. Microenvironmental and Molecular Pathways Driving Dormancy Escape in Bone Metastases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11893. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411893

Chicago/Turabian StyleBakir, Mohamad, Alhomam Dabaliz, Ahmad Dawalibi, and Khalid S. Mohammad. 2025. "Microenvironmental and Molecular Pathways Driving Dormancy Escape in Bone Metastases" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11893. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411893

APA StyleBakir, M., Dabaliz, A., Dawalibi, A., & Mohammad, K. S. (2025). Microenvironmental and Molecular Pathways Driving Dormancy Escape in Bone Metastases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11893. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411893