Atelocollagen Increases Collagen Synthesis by Promoting Glycine Transporter 1 in Aged Mouse Skin

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Atelocollagen Increases GlyT1 Expression and Intercellular Glycine Concentration in Senescent Human Fibroblasts

2.2. Atelocollagen Decreases Oxidative Stress and NF-κB Activity in Senescent Human Fibroblasts

2.3. Atelocollagen Decreases MMP1/3/9 Expression and Increases SMAD2/3 Expression in Senescent Human Fibroblasts

2.4. Atelocollagen Increases GlyT1 Expression and Decreases Oxidative Stress in Aged Mouse Skin

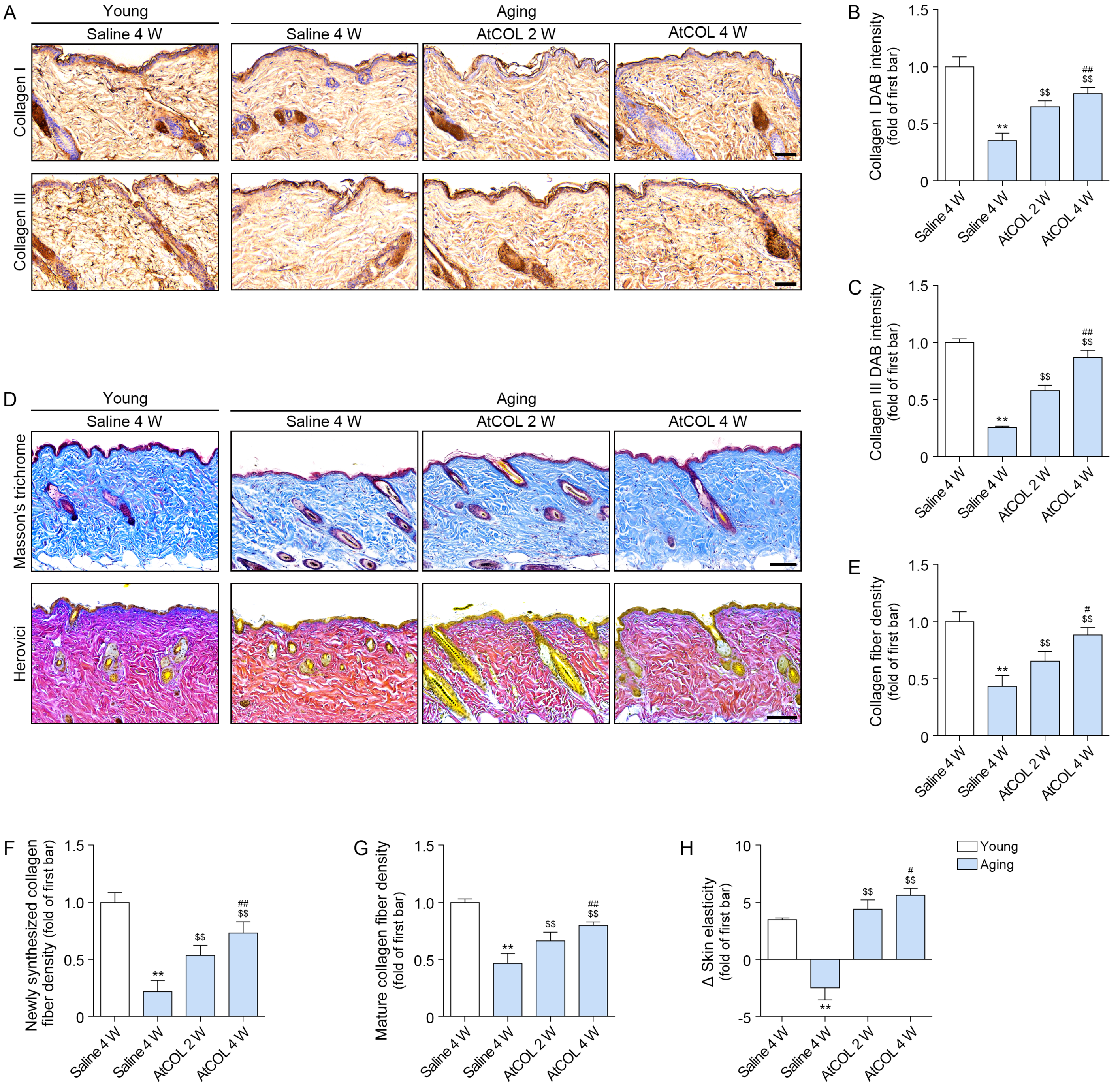

2.5. Atelocollagen Decreases MMP1/3/9 Expression and Increases SMAD2/3 and Collagen Expression in Aged Mouse Skin

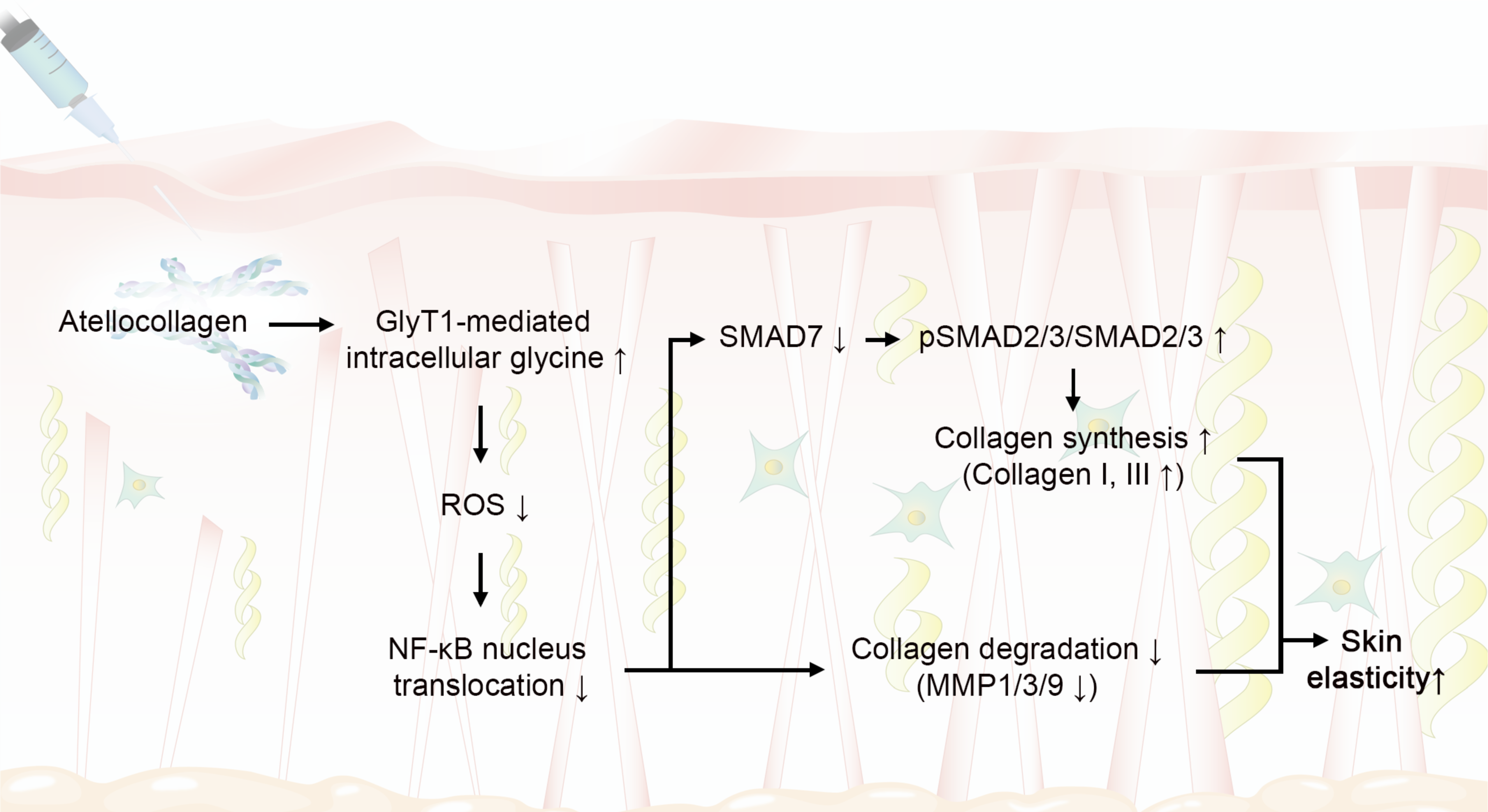

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Atelocollagen Preparation

- (1)

- pH: pH was measured using a calibrated pH meter. The electrode was rinsed with distilled water and calibrated with pH 4.0 and pH 7.0 standard buffers, then immersed directly into the test sample. The acceptable pH range was 6.5–7.5.

- (2)

- Collagen content: Collagen content was quantified by hydroxyproline analysis. One gram of sample was hydrolyzed in 35% HCl at 110 °C, diluted to 1 mg/mL, and analyzed using a hydroxyproline assay kit. Collagen concentration was calculated using the hydroxyproline-based formula described in the internal standard, with an acceptance range of 90.0–110.0% of the indicated amount (3% w/v).

- (3)

- Enzymatic resistance: Sample pieces (10 mm × 10 mm) were immersed in trypsin solution and shaken at 37 °C for 5 h. Structural integrity was evaluated by comparing residual mass and morphology with reference collagen. Samples were required not to degrade within 24 h.

- (4)

- Sterility: Sterility was assessed according to ISO 17665 [48]. Samples were incubated in appropriate culture media and monitored for microbial growth. Batches were accepted only when no microbial contamination was observed.

4.2. In Vitro Experiments

4.2.1. Cell Culture and Senescence Induction

4.2.2. Cytotoxicity Assessment of Atelocollagen

4.2.3. Determination of Working Concentration of Atelocollagen

4.2.4. Preparation of Conditioned Medium

4.2.5. Inhibition Study in Senescent Human Dermal Fibroblasts Treated with Atelocollagen and Glycine

- (1)

- Non-senescent cells treated with DPBS (Non-SnCs/PBS)

- (2)

- Senescent cells treated with DPBS (SnCs/PBS)

- (3)

- Senescent cells treated with atelocollagen (150 μg/mL) (SnCs/AtCOL)

- (4)

- Senescent cells treated with glycine (3 mM) (SnCs/Glycine)

- (5)

- Non-senescent cells pretreated with ALX5407 (200 nM) and treated with DPBS (Non-SnCs/ALX5407/PBS)

- (6)

- Senescent cells pretreated with ALX5407 (200 nM) and treated with DPBS (SnCs/ALX5407/PBS)

- (7)

- Senescent cells pretreated with ALX5407 (200 nM) and treated with atelocollagen (150 μg/mL) (SnCs/ALX5407/AtCOL)

- (8)

- Senescent cells pretreated with ALX5407 (200 nM) and treated with glycine (3 mM) (SnCs/ALX5407/Glycine)

4.3. In Vivo Experiments

4.3.1. Experimental Design

4.3.2. Skin Elasticity Measurement

4.4. RNA Extraction and Quantitative Real-Time PCR

4.5. Protein Isolation and Western Blot Analysis

4.6. Glycine Quantification and Glutathione/Oxidized Glutathione Ratio Analysis

4.7. Immunocytochemistry

4.8. Preparation of Paraffin-Embedded Skin Tissue Blocks

4.8.1. Immunohistochemistry

4.8.2. Masson’s Trichrome Staining

4.8.3. Herovici Staining

4.9. Quantitative and Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ferreira, A.M.; Gentile, P.; Chiono, V.; Ciardelli, G. Collagen for bone tissue regeneration. Acta Biomater. 2012, 8, 3191–3200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.W.; Kwon, S.H.; Choi, J.Y.; Na, J.-I.; Huh, C.-H.; Choi, H.-R.; Park, K.-C. Molecular Mechanisms of Dermal Aging and Antiaging Approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricard-Blum, S. The collagen family. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011, 3, a004978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, M.A.; Quan, T.; Voorhees, J.J.; Fisher, G.J. Extracellular matrix regulation of fibroblast function: Redefining our perspective on skin aging. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 2018, 12, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzaphlidou, M. The role of collagen and elastin in aged skin: An image processing approach. Micron 2004, 35, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.M.; Cheng, M.Y.; Xun, M.H.; Zhao, Z.W.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, W.; Cheng, J.; Ni, J.; Wang, W. Possible Mechanisms of Oxidative Stress-Induced Skin Cellular Senescence, Inflammation, and Cancer and the Therapeutic Potential of Plant Polyphenols. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Hong, Y.; Kim, M. Structural and Functional Changes and Possible Molecular Mechanisms in Aged Skin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthon, J.Y.; Nachat-Kappes, R.; Bey, M.; Cadoret, J.P.; Renimel, I.; Filaire, E. Marine algae as attractive source to skin care. Free Radic. Res. 2017, 51, 555–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittié, L.; Fisher, G.J. UV-light-induced signal cascades and skin aging. Ageing Res. Rev. 2002, 1, 705–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitzer, M.; von Gersdorff, G.; Liang, D.; Dominguez-Rosales, A.; A Beg, A.; Rojkind, M.; Böttinger, E.P. A mechanism of suppression of TGF-β/SMAD signaling by NF-κB/RelA. Genes Dev. 2000, 14, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Quan, T.; Shao, Y.; Voorhees, J.J.; Fisher, G.J. Oxidative exposure impairs TGF-β pathway via reduction of type II receptor and SMAD3 in human skin fibroblasts. Age 2014, 36, 9623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xing, F.; Wang, J.; Luo, X.; Kong, Y.; Zhang, G. Age-related changes in the ratio of Type I/III collagen and fibril diameter in mouse skin. Regen. Biomater. 2022, 10, rbac110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E.; Boo, Y.C. Combination of Glycinamide and Ascorbic Acid Synergistically Promotes Collagen Production and Wound Healing in Human Dermal Fibroblasts. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krupsky, M.; Kuang, P.P.; Goldstein, R.H. Regulation of type I collagen mRNA by amino acid deprivation in human lung fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 13864–13868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karna, E.; Miltyk, W.; Wołczyński, S.; Pałka, J.A. The potential mechanism for glutamine-induced collagen biosynthesis in cultured human skin fibroblasts. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2001, 130, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szoka, L.; Karna, E.; Hlebowicz-Sarat, K.; Karaszewski, J.; Palka, J.A. Exogenous proline stimulates type I collagen and HIF-1α expression and the process is attenuated by glutamine in human skin fibroblasts. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2017, 435, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Paz-Lugo, P.; Lupiáñez, J.A.; Meléndez-Hevia, E. High glycine concentration increases collagen synthesis by articular chondrocytes in vitro: Acute glycine deficiency could be an important cause of osteoarthritis. Amino Acids 2018, 50, 1357–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Torres, I.; Zuniga-Munoz, A.M.; Guarner-Lans, V. Beneficial Effects of the Amino Acid Glycine. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2017, 17, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Han, D.; Xu, R.; Wu, H.; Qu, C.; Wang, F.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Y. Glycine protects against high sucrose and high fat-induced non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in rats. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 80223–80237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Ramírez, A.; Ortiz-Balderas, E.; Cardozo-Saldaña, G.; Diaz-Diaz, E.; El-Hafidi, M. Glycine restores glutathione and protects against oxidative stress in vascular tissue from sucrose-fed rats. Clin. Sci. 2014, 126, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, A.; Tahir, I.; Javed, S.; Waring, S.M.; Ford, D.; Hirst, B.H. Glycine transporter GLYT1 is essential for glycine-mediated protection of human intestinal epithelial cells against oxidative damage. J. Physiol. 2010, 588, 995–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Eynden, J.; Ali, S.S.; Horwood, N.; Carmans, S.; Brône, B.; Hellings, N.; Steels, P.; Harvey, R.J.; Rigo, J.-M. Glycine and glycine receptor signalling in non-neuronal cells. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2009, 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, R.; Schoneveld, O.J.; Pappa, A.; Panayiotidis, M.I. The central role of glutathione in the pathophysiology of human diseases. Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 2007, 113, 234–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, J.; Li, C.; Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Zhao, D.; Wang, S.; Zhang, H.; Huang, Y.; Guo, X. Glycine Transporter-1 and glycine receptor mediate the antioxidant effect of glycine in diabetic rat islets and INS-1 cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2018, 123, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinkevich, N.S.; Gutterman, D.D. ROS-induced ROS release in vascular biology: Redox-redox signaling. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol. 2011, 301, H647–H653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Hillas, P.J.; Báez, J.A.; Nokelainen, M.; Balan, J.; Tang, J.; Spiro, R.; Polarek, J.W. The application of recombinant human collagen in tissue engineering. BioDrugs 2004, 18, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochiya, T.; Nagahara, S.; Sano, A.; Itoh, H.; Terada, M. Biomaterials for gene delivery: Atelocollagen-mediated controlled release of molecular medicines. Curr. Gene Ther. 2001, 1, 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheema, U.; Ananta, M.; Mudera, V. Collagen: Applications of a natural polymer in regenerative medicine. Regen. Med. Tissue Eng.-Cells Biomater. 2011, 29, 287–300. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, J.U.; Roh, M.R.; Rah, D.K.; Ae, N.K.; Suh, H.; Chung, K.Y. The effect of succinylated atelocollagen and ablative fractional resurfacing laser on striae distensae. J. Dermatolog. Treat. 2011, 22, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suh, D.S.; Yoo, J.C.; Woo, S.H.; Kwak, A.S. Intra-Articular Atelocollagen Injection for the Treatment of Articular Cartilage Defects in Rabbit Model. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2021, 18, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, B.N.; Bell, S.C.; De Vivo, M.; Kowalski, L.R.; Lechner, S.M.; Ognyanov, V.I.; Tham, C.-S.; Tsai, C.; Jia, J.; Ashton, D.; et al. ALX 5407: A potent, selective inhibitor of the hGlyT1 glycine transporter. Mol. Pharmacol. 2001, 60, 1414–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herovici, C. Picropolychrome: Histological staining technic intended for the study of normal and pathological connective tissue. Rev. Fr. D’etudes Clin. Biol. 1963, 8, 88–89. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony, P.P. Manual of histological demonstration techniques. J. Clin. Pathol. 1975, 28, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Fisher, G.J.; Kim, A.J.; Quan, T. Age-related changes in dermal collagen physical properties in human skin. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0292791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos-Garcés, V.; Molina Aguilar, P.; Bea Serrano, C.; García-Bustos, V.; Seguí, J.B.; Izquierdo, A.F.; Ruiz-Saurí, A. Age-related dermal collagen changes during development, maturation and ageing—A morphometric and comparative study. J. Anat. 2014, 225, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eastoe, J.E. The amino acid composition of mammalian collagen and gelatin. Biochem. J. 1955, 61, 589–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastoe, J.E. The amino acid composition of fish collagen and gelatin. Biochem. J. 1957, 65, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holwerda, A.M.; van Loon, L.J.C. The impact of collagen protein ingestion on musculoskeletal connective tissue remodeling: A narrative review. Nutr. Rev. 2022, 80, 1497–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, C.; Mikhal’chik, E.V.; Suprun, M.V.; Papacharalambous, M.; Truhanov, A.I.; Korkina, L.G. Skin Antiageing and Systemic Redox Effects of Supplementation with Marine Collagen Peptides and Plant-Derived Antioxidants: A Single-Blind Case-Control Clinical Study. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 4389410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, L.; Li, B. Effect of Orally Administered Collagen Peptides from Bovine Bone on Skin Aging in Chronologically Aged Mice. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatore, L.; Natali, M.L.; Brunetti, C.; Sannino, A.; Gallo, N. An Update on the Clinical Efficacy and Safety of Collagen Injectables for Aesthetic and Regenerative Medicine Applications. Polymers 2023, 15, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagenaar-Miller, R.A.; Engelholm, L.H.; Gavard, J.; Yamada, S.S.; Gutkind, J.S.; Behrendt, N.; Bugge, T.H.; Holmbeck, K. Complementary roles of intracellular and pericellular collagen degradation pathways In Vivo. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 27, 6309–6322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, A.A. Blood glutathione in severe malnutrition in childhood. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1986, 80, 911–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, A.A.; Gibson, N.R.; Lu, Y.; Jahoor, F. Synthesis of erythrocyte glutathione in healthy adults consuming the safe amount of dietary protein. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 80, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavi Kishor, P.B.; Suravajhala, P.; Rathnagiri, P.; Sreenivasulu, N. Intriguing Role of Proline in Redox Potential Conferring High Temperature Stress Tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 867531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koo, T.H.; Lee, J.K.; Grogan, S.P.; Ra, H.J.; D’Lima, D.D. Biocompatibility Study of Purified and Low-Temperature-Sterilized Injectable Collagen for Soft Tissue Repair: Intramuscular Implantation in Rats. Gels 2024, 10, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koo, T.-H.; Lee, J.K.; Grogan, S.P.; D’Lima, D.D. Biocompatibility Evaluation of Porcine-Derived Collagen Sheets for Clinical Applications: In Vitro Cytotoxicity, In Vivo Sensitization, and Intracutaneous Reactivity Studies. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO 17665:2024; Sterilization of Health Care Products—Moist Heat—Requirements for the Development, Validation and Routine Control of a Sterilization Process for Medical Devices. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- Wu, Y.H.; Cheng, M.L.; Ho, H.Y.; Chiu, D.T.; Wang, T.C. Telomerase prevents accelerated senescence in glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD)-deficient human fibroblasts. J. Biomed. Sci. 2009, 16, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charan, J.; Kantharia, N.D. How to calculate sample size in animal studies? J. Pharmacol. Pharmacother. 2013, 4, 303–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Byun, K.-A.; Oh, S.M.; Oh, S.; Kim, H.M.; Oh, M.; Kim, G.; Kim, M.S.; Son, K.H.; Byun, K. Atelocollagen Increases Collagen Synthesis by Promoting Glycine Transporter 1 in Aged Mouse Skin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11825. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411825

Byun K-A, Oh SM, Oh S, Kim HM, Oh M, Kim G, Kim MS, Son KH, Byun K. Atelocollagen Increases Collagen Synthesis by Promoting Glycine Transporter 1 in Aged Mouse Skin. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11825. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411825

Chicago/Turabian StyleByun, Kyung-A, Seung Min Oh, Seyeon Oh, Hyoung Moon Kim, Myungjune Oh, Geebum Kim, Min Seung Kim, Kuk Hui Son, and Kyunghee Byun. 2025. "Atelocollagen Increases Collagen Synthesis by Promoting Glycine Transporter 1 in Aged Mouse Skin" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11825. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411825

APA StyleByun, K.-A., Oh, S. M., Oh, S., Kim, H. M., Oh, M., Kim, G., Kim, M. S., Son, K. H., & Byun, K. (2025). Atelocollagen Increases Collagen Synthesis by Promoting Glycine Transporter 1 in Aged Mouse Skin. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11825. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411825