Intratumoral Heterogeneity of MAGED4 Expression in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Epigenetic Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

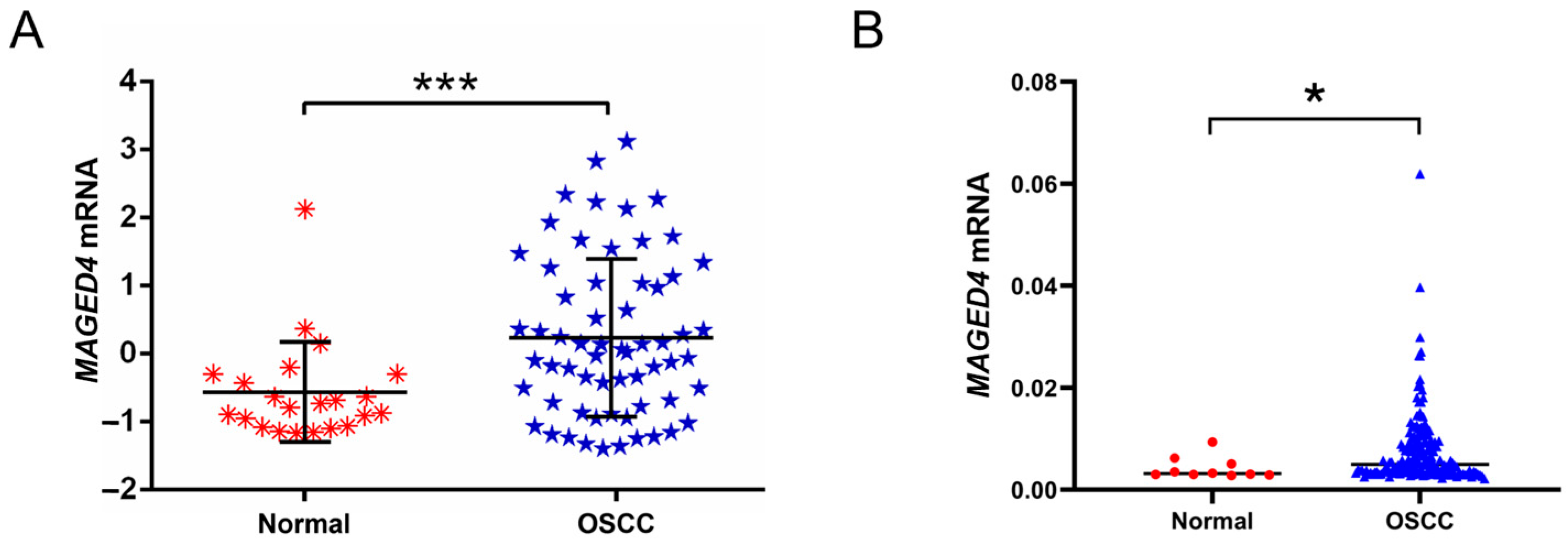

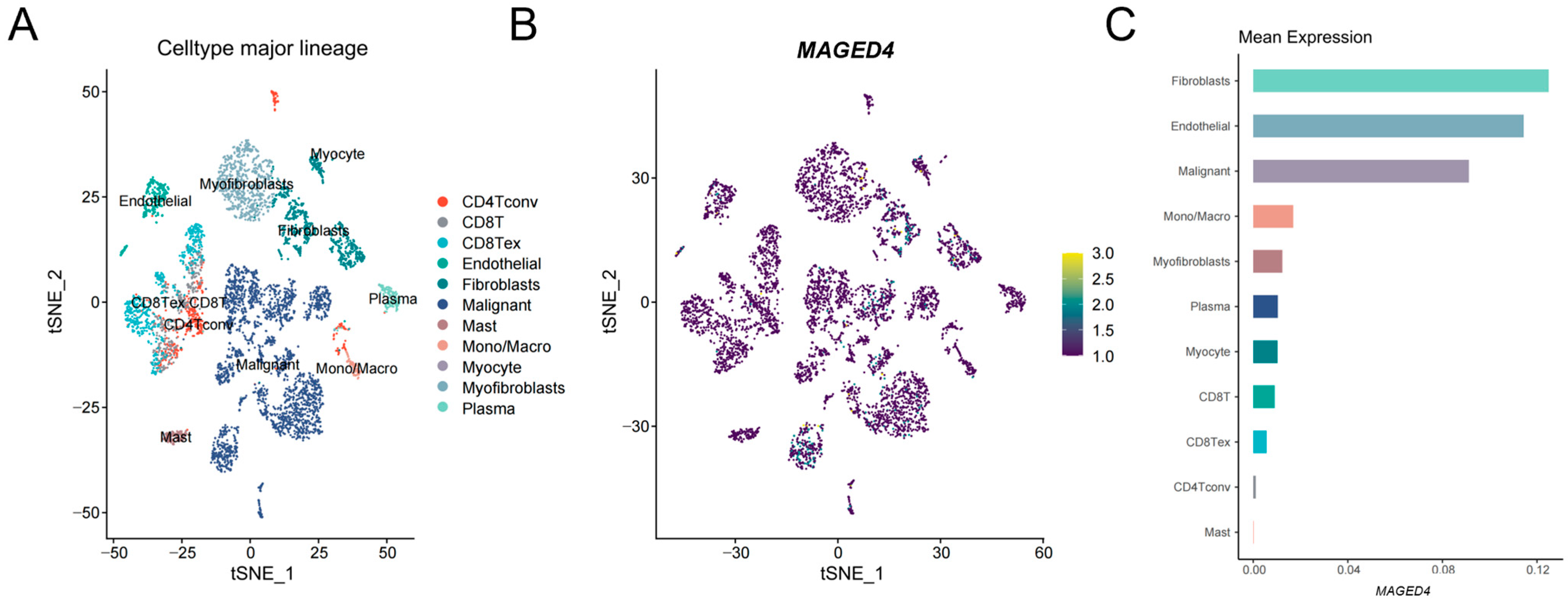

2.1. Elevated Expression of MAGED4 in OSCC

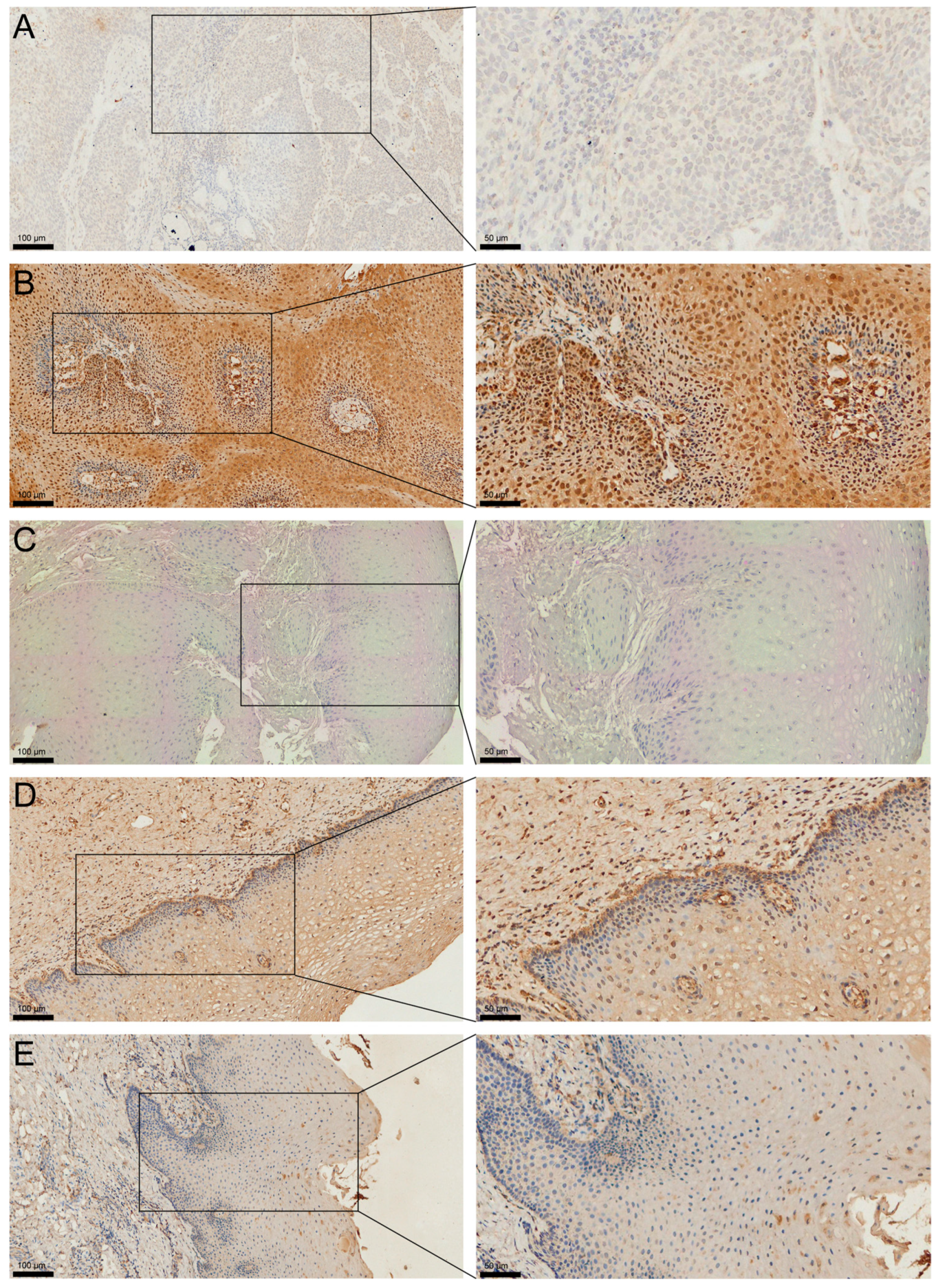

2.2. Heterogeneous Expression of MAGED4 in OSCC

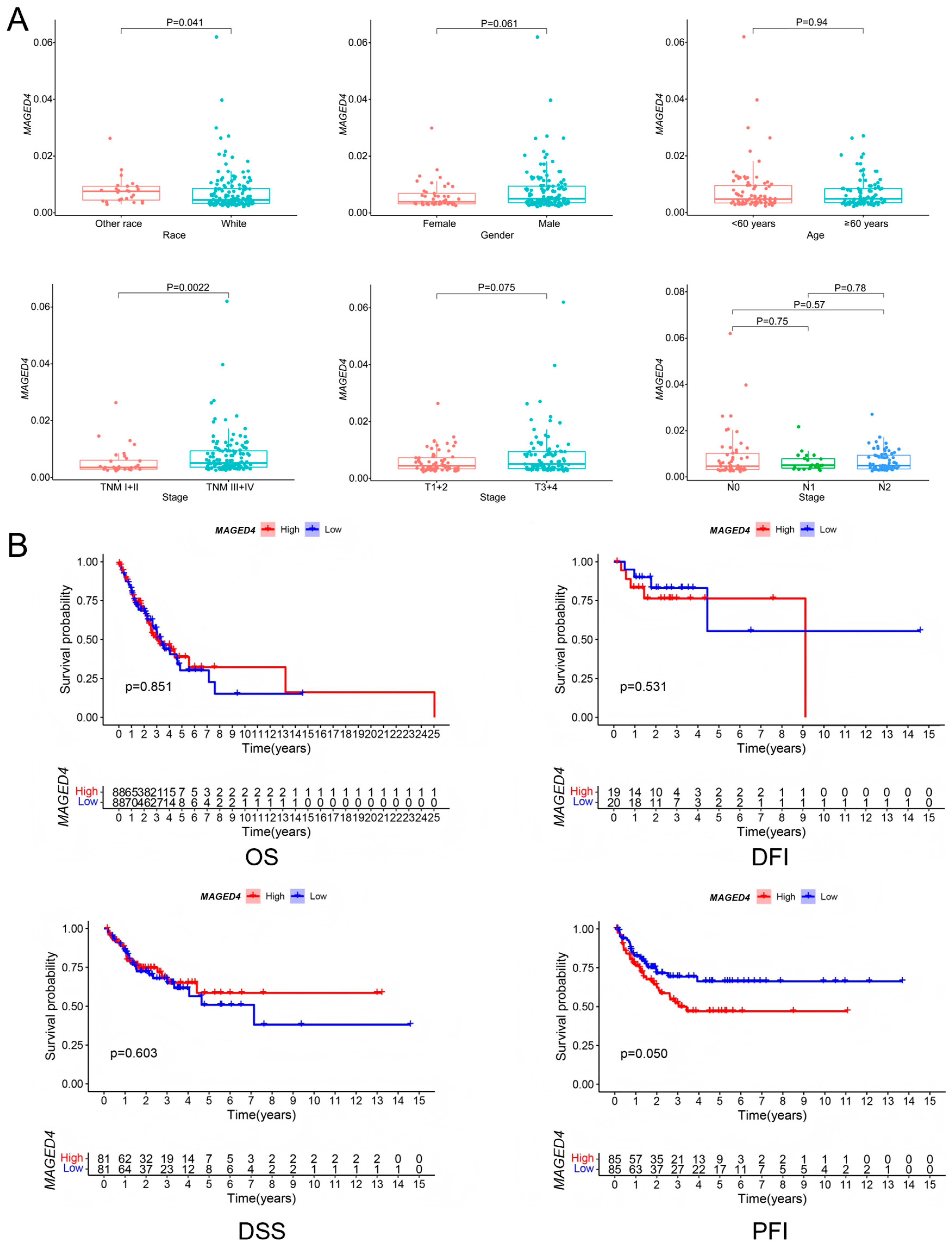

2.3. Clinical Correlates of MAGED4 Expression in OSCC

2.4. Suppression of MAGED4 Transcriptional Activity by Promoter Methylation

2.5. Implication of MAGED4′s Involvement in Histone Acetylation via Co-Expression Network

2.6. Attenuation of MAGED4 Expression Heterogeneity in OSCC by Epigenetic Drugs

2.7. Regulation of MAGED4 Promoter Methylation by Epigenetic Drugs

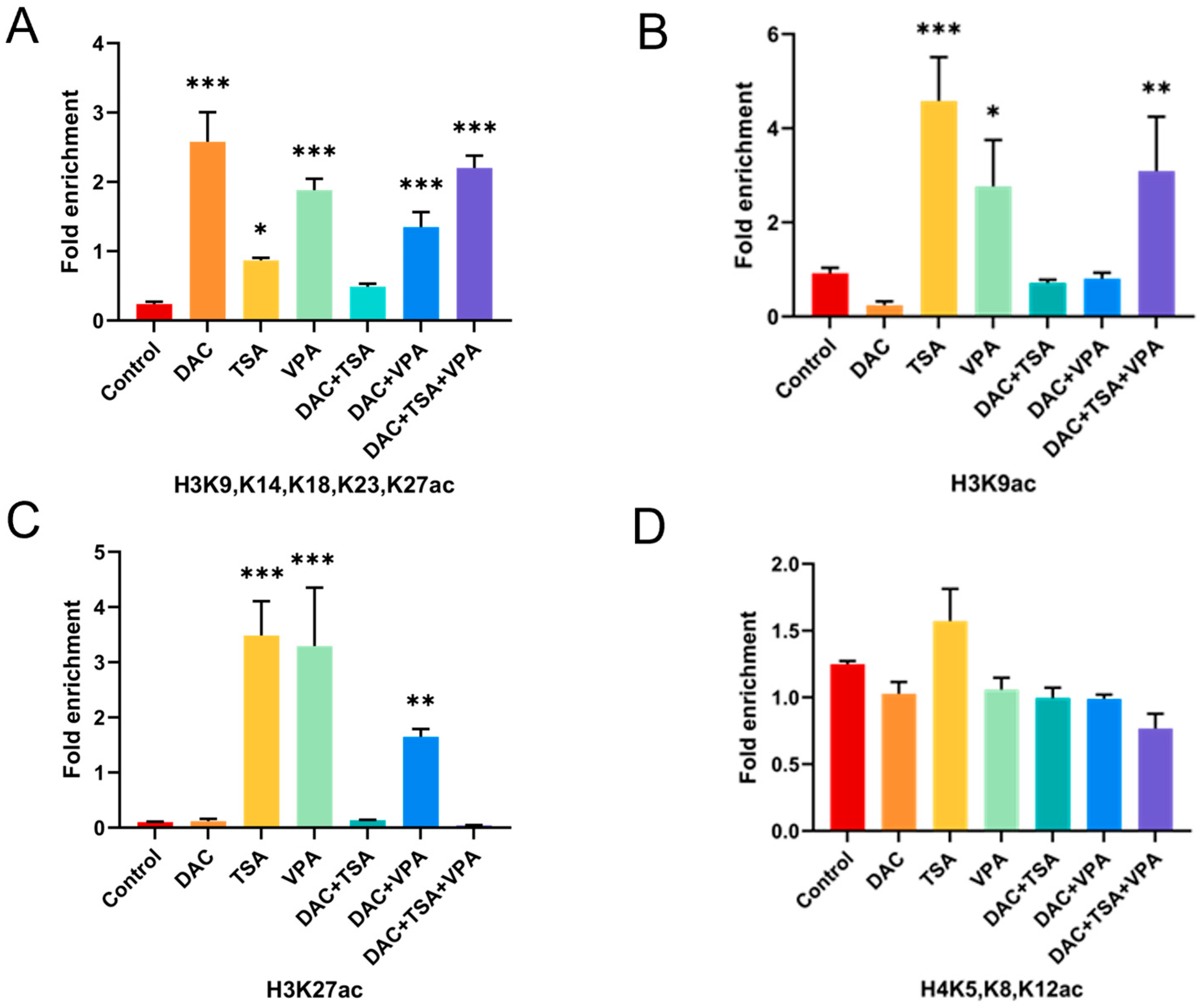

2.8. Modulation of Histone H3 Acetylation at the MAGED4 Promoter by Epigenetic Drugs

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Integrated Bioinformatic Analysis

4.2. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-Seq) Data Processing

4.3. Tissue Samples

4.4. IHC

4.5. Cell Culture and Pharmacological Interventions

4.6. Methylation Promoter Luciferase Reporter Assays

4.7. RT-PCR and qRT-PCR

4.8. Western Blot Analysis

4.9. Pyrosequencing Methylation Analysis

4.10. ChIP-qPCR

4.11. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OSCC | oral squamous cell carcinoma |

| MAGE | melanoma-associated antigen |

| OLK | oral leukoplakia |

| TCGA | The Cancer Genome Atlas |

| IHC | immunohistochemistry |

| OS | overall survival |

| DFI | disease-free interval |

| DSS | disease-specific survival |

| PFI | progression-free interval |

| GO | gene ontology |

| DAC | 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine |

| TSA | trichostatin A |

| VPA | valproic acid |

| RT-PCR | reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction |

| qRT-PCR | quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction |

| DNMT | DNA methyltransferase |

| ChIP-qPCR | chromatin immunoprecipitation-qPCR |

| HLA | human leukocyte antigen |

| CTL | cytotoxic T lymphocyte |

| HDAC | histone deacetylase |

| MBD | methyl-CpG binding domain |

| HNSC | head and neck squamous cell carcinoma |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium |

| FBS | fetal bovine serum |

| SAM | s-adenosylmethionine |

| RT | room temperature |

References

- Chen, Y.; Wei, Y.; Yang, C.; Liu, C.-J.; Yeh, L.-Y.; Chou, C.-H.; Chang, K.-W.; Lin, S.-C. miR-125b suppresses oral oncogenicity by targeting the anti-oxidative gene PRXL2A. Redox Biol. 2019, 22, 101140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Luo, Q.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H.; Chen, W.; Meng, G.; Chen, F. The role of NLRP3 inflammasome in 5-fluorouracil resistance of oral squamous cell carcinoma. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 36, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, C.; Chen, L.; Lin, Z.; Liu, L.; Shao, W.; Zhang, R.; Lin, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, W.; Jia, H.; et al. Lenvatinib Targets FGF Receptor 4 to Enhance Antitumor Immune Response of Anti-Programmed Cell Death-1 in HCC. Hepatology 2021, 74, 2544–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.; Song, Z.; Chen, J.; Tang, Z.; Wang, B. Molecular basis, potential biomarkers, and future prospects of OSCC and PD-1/PD-L1 related immunotherapy methods. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, F.Y.; Cheng, T.L.; Chang, H.J.; Chiu, H.; Huang, M.; Chang, M.; Chen, C.; Yang, M.; Wang, J.; Lin, S. Differential gene expression profile of MAGE family in taiwanese patients with colorectal cancer. J. Surg. Oncol. 2010, 102, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnadas, D.K.; Shusterman, S.; Bai, F.; Diller, L.; Sullivan, J.E.; Cheerva, A.C.; George, R.E.; Lucas, K.G. A phase I trial combining decitabine/dendritic cell vaccine targeting MAGE-A1, MAGE-A3 and NY-ESO-1 for children with relapsed or therapy-refractory neuroblastoma and sarcoma. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2015, 64, 1251–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshita, C.; Takikawa, M.; Kume, A.; Miyata, H.; Ashizawa, T.; Iizuka, A.; Kiyohara, Y.; Yoshikawa, S.; Tanosaki, R.; Yamazaki, N.; et al. Dendritic cell-based vaccination in metastatic melanoma patients: Phase II clinical trial. Oncol. Rep. 2012, 28, 1131–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, M.; Nakahira, K.; Kawano, Y.; Katakura, H.; Yoshimine, T.; Shimizu, K.; Kim, S.U.; Ikenaka, K. MAGE-E1, a new member of the melanoma-associated antigen gene family and its expression in human glioma. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 4809–4814. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.M.; Shen, N.; Xie, S.; Bi, S.-Q.; Luo, B.; Lin, Y.-D.; Fu, J.; Zhou, S.-F.; Luo, G.-R.; Xie, X.-X.; et al. MAGED4 expression in glioma and upregulation in glioma cell lines with 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine treatment. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2014, 15, 3495–3501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, C.E.; Lim, K.P.; Gan, C.P.; Marsh, C.A.; Zain, R.B.; Abraham, M.T.; Prime, S.S.; Teo, S.-H.; Gutkind, J.S.; Patel, V.; et al. Over-expression of MAGED4B increases cell migration and growth in oral squamous cell carcinoma and is associated with poor disease outcome. Cancer Lett. 2012, 321, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, S.C.; Chandramouli, G.V.; Saleh, A.; Zain, R.; Lau, S.; Sivakumaren, S.; Pathmanathan, R.; Prime, S.; Teo, S.; Patel, V.; et al. Gene expression in human oral squamous cell carcinoma is influenced by risk factor exposure. Oral Oncol. 2009, 45, 712–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, K.P.; Chun, N.A.; Gan, C.P.; Teo, S.-H.; Rahman, Z.A.A.; Abraham, M.T.; Zain, R.B.; Ponniah, S.; Cheong, S.C. Identification of immunogenic MAGED4B peptides for vaccine development in oral cancer immunotherapy. Hum. Vaccine Immunother. 2014, 10, 3214–3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, S.J.; Fong, S.; Gan, C.P.; Pua, K.C.; Lim, P.V.H.; Lau, S.H.; Zain, R.B.; Abraham, T.; Ismail, S.M.; Rahman, Z.A.A.; et al. In vitro evaluation of dual-antigenic PV1 peptide vaccine in head and neck cancer patients. Hum. Vaccine Immunother. 2019, 15, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.M.; He, S.J.; Shen, N.; Luo, B.; Fan, R.; Fu, J.; Luo, G.-R.; Zhou, S.-F.; Xiao, S.-W.; Xie, X.-X. Overexpression of MAGE-D4 in colorectal cancer is a potentially prognostic biomarker and immunotherapy target. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2014, 7, 3918–3927. [Google Scholar]

- Bi, S.; Zhang, Q.; Zeng, X.; Liu, C.; Nong, W.-X.; Xie, H.; Li, F.; Lin, L.-N.; Luo, B.; Ge, Y.-Y.; et al. Combined treatment with epigenetic agents enhances anti-tumor activity of MAGE-D4 peptide-specific T cells by upregulating the MAGE-D4 expression in glioma. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 873639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, F.C.; Dorff, T.B.; Tran, B. The new era of prostate-specific membrane antigen-directed immunotherapies and beyond in advanced prostate cancer: A review. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2023, 15, 17588359231170474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wischnewski, F.; Pantel, K.; Schwarzenbach, H. Promoter demethylation and histone acetylation mediate gene expression of MAGE-A1, -A2, -A3, and -A12 in human cancer cells. Mol. Cancer Res. 2006, 4, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Bost, A.; Szmania, S.; Stone, K.; Garg, T.; Hoerring, A.; Szymonifka, J.; Shaughnessy, J.; Barlogie, B.; Prentice, H.G.; van Rhee, F. Epigenetic modulation of MAGE-A3 antigen expression in multiple myeloma following treatment with the demethylation agent 5-azacitidine and the histone deacetlyase inhibitor MGCD0103. Cytotherapy 2011, 13, 618–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, H.; Schmidt, M.; Hopp, L.; Davitavyan, S.; Arakelyan, A.; Loeffler-Wirth, H. Integrated Multi-Omics Maps of Lower-Grade Gliomas. Cancers 2022, 14, 2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Ge, Y.; Luo, B.; Xie, X.; Shen, N.; Nong, W.; Bi, S.; Lin, L.; Wei, X.; Wu, S.; et al. Synergistic regulation of methylation and SP1 on MAGE-D4 transcription in glioma. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2021, 13, 2241–2255. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, H.; Fan, Y.; Cai, D.; Lei, R.; Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; Shen, L.; Gu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; et al. SNORA28 Promotes Proliferation and Radioresistance in Colorectal Cancer Cells through the STAT3 Pathway by Increasing H3K9 Acetylation in the LIFR Promoter. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, e2405332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, A.; Saini, K.K.; Chandramouli, A.; Tripathi, K.; Khan, M.A.; Satrusal, S.R.; Verma, A.; Mandal, B.; Rai, P.; Meena, S.; et al. ACSL4-mediated H3K9 and H3K27 hyperacetylation upregulates SNAIL to drive TNBC metastasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2408049121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, W.; Kang, N.; Sheng, L.; Liu, S.; Tao, L.; Cao, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, B.; et al. MCT1-governed pyruvate metabolism is essential for antibody class-switch recombination through H3K27 acetylation. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, S.; Mohammadi, F.; Porabdollah, M.; Mohajerani, S.A.; Khodadad, K.; Nadji, S.A. Characterization of melanoma-associated antigen-a genes family differential expression in non-small-cell lung cancers. Clin. Lung Cancer 2012, 13, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curioni-Fontecedro, A.; Pitocco, R.; Schoenewolf, N.L.; Holzmann, D.; Soldini, D.; Dummer, R.; Calvieri, S.; Moch, H.; Mihic-Probst, D.; Fitsche, A. Intratumoral Heterogeneity of MAGE-C1/CT7 and MAGE-C2/CT10 Expression in Mucosal Melanoma. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 432479, Erratum in BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 5256364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schooten, E.; Di Maggio, A.; van Bergen En Henegouwen, P.; Kijanka, M.M. MAGE-A antigens as targets for cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2018, 67, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lian, Y.; Meng, L.; Ding, P.; Sang, M. Epigenetic regulation of MAGE family in human cancer progression-DNA methylation, histone modification, and non-coding RNAs. Clin. Epigenetics 2018, 10, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marusyk, A.; Polyak, K. Tumor heterogeneity: Causes and consequences. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1805, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, A.K.; Udaltsova, N.; Engels, E.A.; Katzel, J.A.; Yanik, E.L.; Katki, H.A.; Lingen, M.W.; Silverberg, M.J. Oral Leukoplakia and Risk of Progression to Oral Cancer: A Population-Based Cohort Study. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2020, 112, 1047–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, R.L. Immunology and Immunotherapy of Head and Neck Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 3293–3304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geum, D.H.; Hwang, D.S.; Lee, C.H.; Cho, S.D.; Jang, M.A.; Ryu, M.H.; Kim, U.K. PD-L1 Expression Correlated with Clinicopatho-logical Factors and Akt/Stat3 Pathway in Oral SCC. Life 2022, 12, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayar, E.; Patel, R.A.; Coleman, I.M.; Roudier, M.P.; Zhang, A.; Mustafi, P.; Low, J.-Y.; Hanratty, B.; Ang, L.S.; Bhatia, V.; et al. Reversible epigenetic alterations mediate PSMA expression heterogeneity in advanced metastatic prostate cancer. JCI Insight 2023, 8, e162907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, K.; Staaf, J.; Lauss, M.; Aine, M.; Lindgren, D.; Bendahl, P.-O.; Vallon-Christersson, J.; Barkardottir, R.B.; Höglund, M.; Borg, Å.; et al. An integrated genomics analysis of epigenetic subtypes in human breast tumors links DNA methylation patterns to chromatin states in normal mammary cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2016, 18, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimmino, L.; Dawlaty, M.M.; Ndiaye-Lobry, D.; Yap, Y.S.; Bakogianni, S.; Yu, Y.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Shaknovich, R.; Geng, H.; Lobry, C.; et al. TET1 is a tumor suppressor of hematopoietic malignancy. Nat. Immunol. 2015, 16, 653–662, Erratum in Nat. Immunol. 2015, 16, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Gu, X.; Han, X.; Gao, Q.; Liu, J.; Guo, T.; Gao, D. Crosstalk between DNA methylation and histone acetylation triggers GDNF high transcription in glioblastoma cells. Clin. Epigenetics 2020, 12, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, J.D.; Meehan, R.R.; Henzel, W.J.; Maurer-Fogy, I.; Jeppesen, P.; Klein, F.; Bird, A. Purification, sequence, and cellular localization of a novel chromosomal protein that binds to methylated DNA. Cell 1992, 69, 905–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, X.; Ng, H.H.; Johnson, C.A.; Laherty, C.D.; Turner, B.M.; Eisenman, R.N.; Bird, A. Transcriptional repression by the methyl-CpG-binding protein MeCP2 involves a histone deacetylase complex. Nature 1998, 393, 386–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; Wang, Y.; Dong, X.; Sun, D.; Liu, Z.; Yue, J.; Wang, H.; Li, T.; Wang, C. TISCH2: Expanded datasets and new tools for single-cell transcriptome analyses of the tumor microen-vironment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D1425–D1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Clinicopathological Features | MAGED4 Protein | χ2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Expression | Low Expression | |||

| Genders | ||||

| Male | 68(79.1) | 21(61.8) | 3.808 | 0.051 |

| Female | 18(20.9) | 13(38.2) | ||

| Age (years) | ||||

| ≤58 | 46(53.5) | 14(41.2) | 1.477 | 0.224 |

| >58 | 40(46.5) | 20(58.8) | ||

| Differentiation degree △ | ||||

| low-undifferentiated | 15(17.6) | 8(25.8) | 0.951 | 0.329 |

| high-moderately differentiated | 70(82.4) | 23(74.2) | ||

| Tumor sizes (cm) △ * | ||||

| ≤2 | 24(38.7) | 5(19.2) | 3.146 | 0.076 |

| >2 | 38(61.3) | 21(80.8) | ||

| Expression of ki-67 (%) △ | ||||

| ≤45 | 43(56.6) | 18(64.3) | 1.700 | 0.427 |

| 45–60 | 20(26.3) | 4(14.3) | ||

| >60 | 13(17.1) | 6(21.4) | ||

| Expression of P53 △ | ||||

| Negative | 28(46.7) | 15(57.7) | 0.882 | 0.348 |

| Positive | 32(53.3) | 11(42.3) | ||

| Expression of P16 △ | ||||

| Negative | 38(64.4) | 16(72.7) | 0.499 | 0.480 |

| Positive | 21(35.6) | 6(27.3) | ||

| TNM Stage △ | ||||

| I/II | 42(62.7) | 21(77.8) | 1.983 | 0.159 |

| III/IV | 25(37.3) | 6(22.2) | ||

| Lymph node metastasis △ | ||||

| Positive | 20(33.9) | 11(47.8) | 1.365 | 0.243 |

| Negative | 39(66.1) | 12(52.2) | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xie, H.; Li, F.; Zou, X.; Yu, X.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Nong, W.; Xie, L.; Wang, Y.; Luo, B.; et al. Intratumoral Heterogeneity of MAGED4 Expression in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Epigenetic Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11772. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411772

Xie H, Li F, Zou X, Yu X, Zhang S, Wang Y, Nong W, Xie L, Wang Y, Luo B, et al. Intratumoral Heterogeneity of MAGED4 Expression in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Epigenetic Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11772. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411772

Chicago/Turabian StyleXie, Huan, Feng Li, Xiaoqiong Zou, Xiaoqing Yu, Sheng Zhang, Yanjing Wang, Weixia Nong, Limin Xie, Yi Wang, Bin Luo, and et al. 2025. "Intratumoral Heterogeneity of MAGED4 Expression in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Epigenetic Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11772. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411772

APA StyleXie, H., Li, F., Zou, X., Yu, X., Zhang, S., Wang, Y., Nong, W., Xie, L., Wang, Y., Luo, B., Xie, X., & Zhang, Q. (2025). Intratumoral Heterogeneity of MAGED4 Expression in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Epigenetic Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11772. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411772