Genetic Biomarkers Associated with Dynamic Transitions of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Infection–Precancerous–Cancer of Cervix for Navigating Precision Prevention

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Characterizing Risk Determinants: We first examined the role of HPV infection status along with genetic and epigenetic markers in influencing the progression from LSILs and HSILs to invasive cervical cancer.

- Evaluating Prevention Strategies: Finally, the effectiveness of different combinations of prevention modalities—HPV vaccination, HPV testing, and Pap smears at varied intervals—was assessed across distinct molecular risk profiles.

2. Results

2.1. Natural Evolution of Cervical Cancer

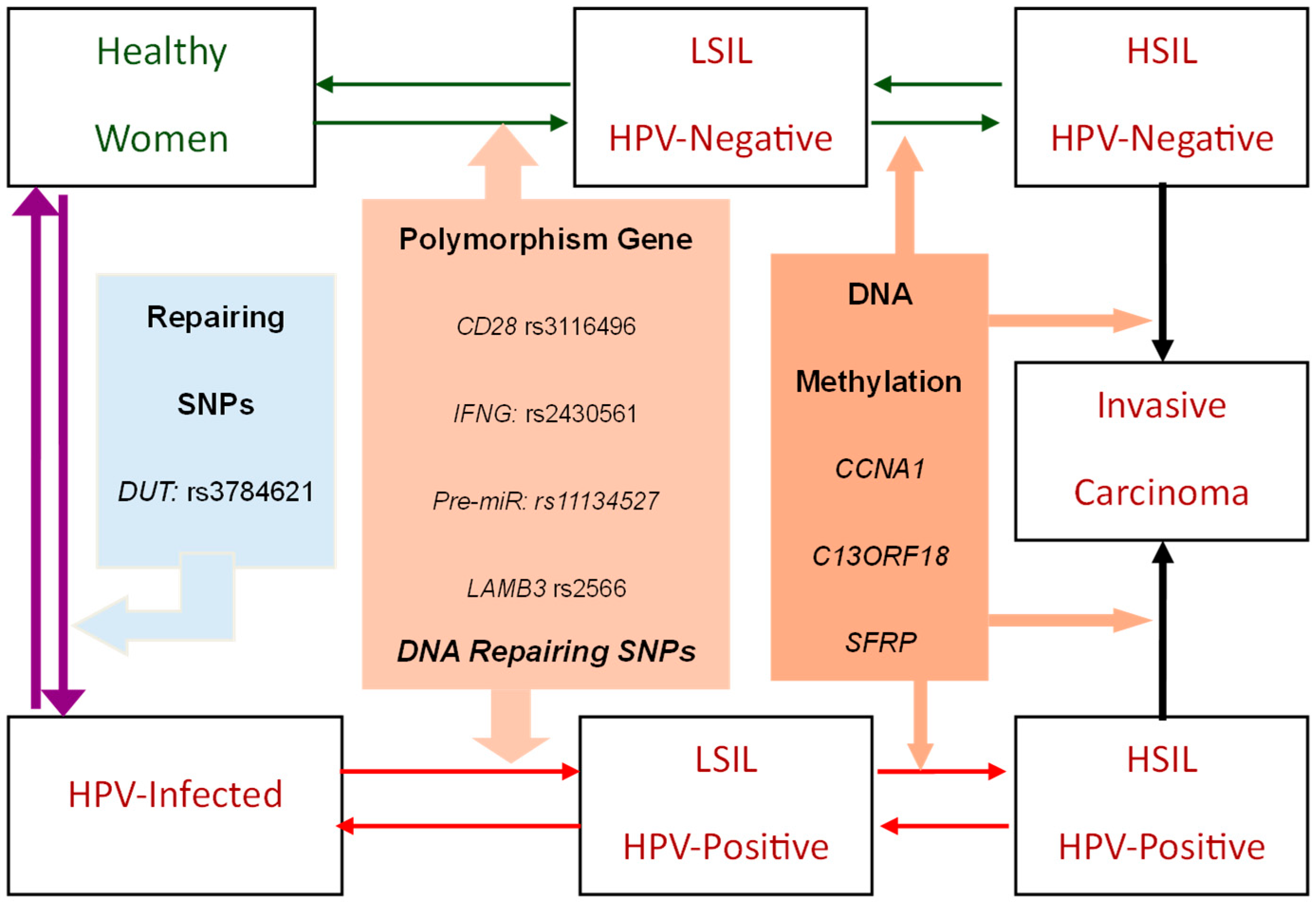

2.1.1. The Natural History Model of Cervical HPV Infection-Precancerous-Cancer Process

2.1.2. Genetic-Biomarker-Driven Cervical Cancer Evolution

2.2. Cervical Cancer Risk Projected by Genetic Biomarker-Guided Seven-State Natural History Model

2.2.1. Internal and External Validation

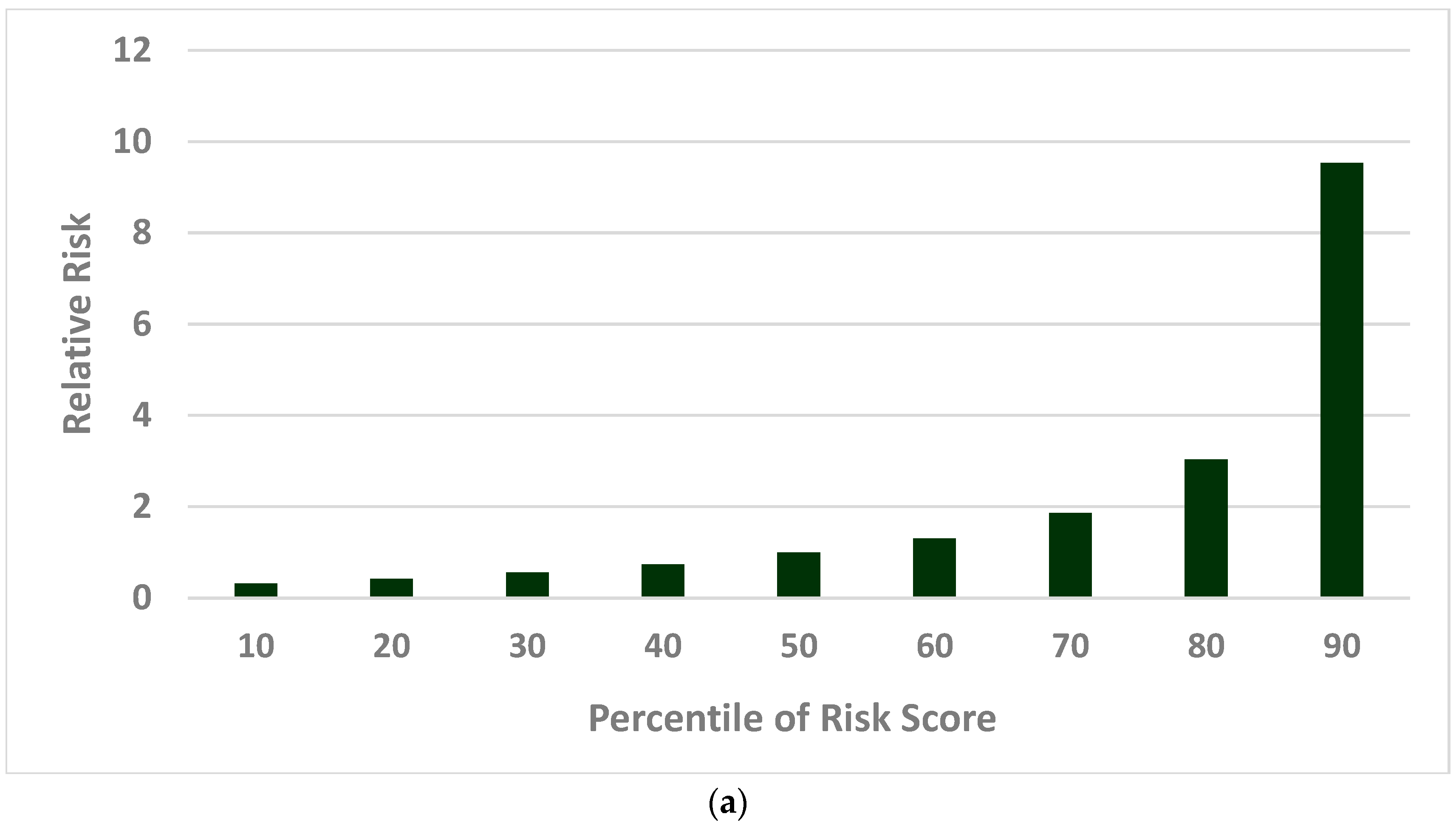

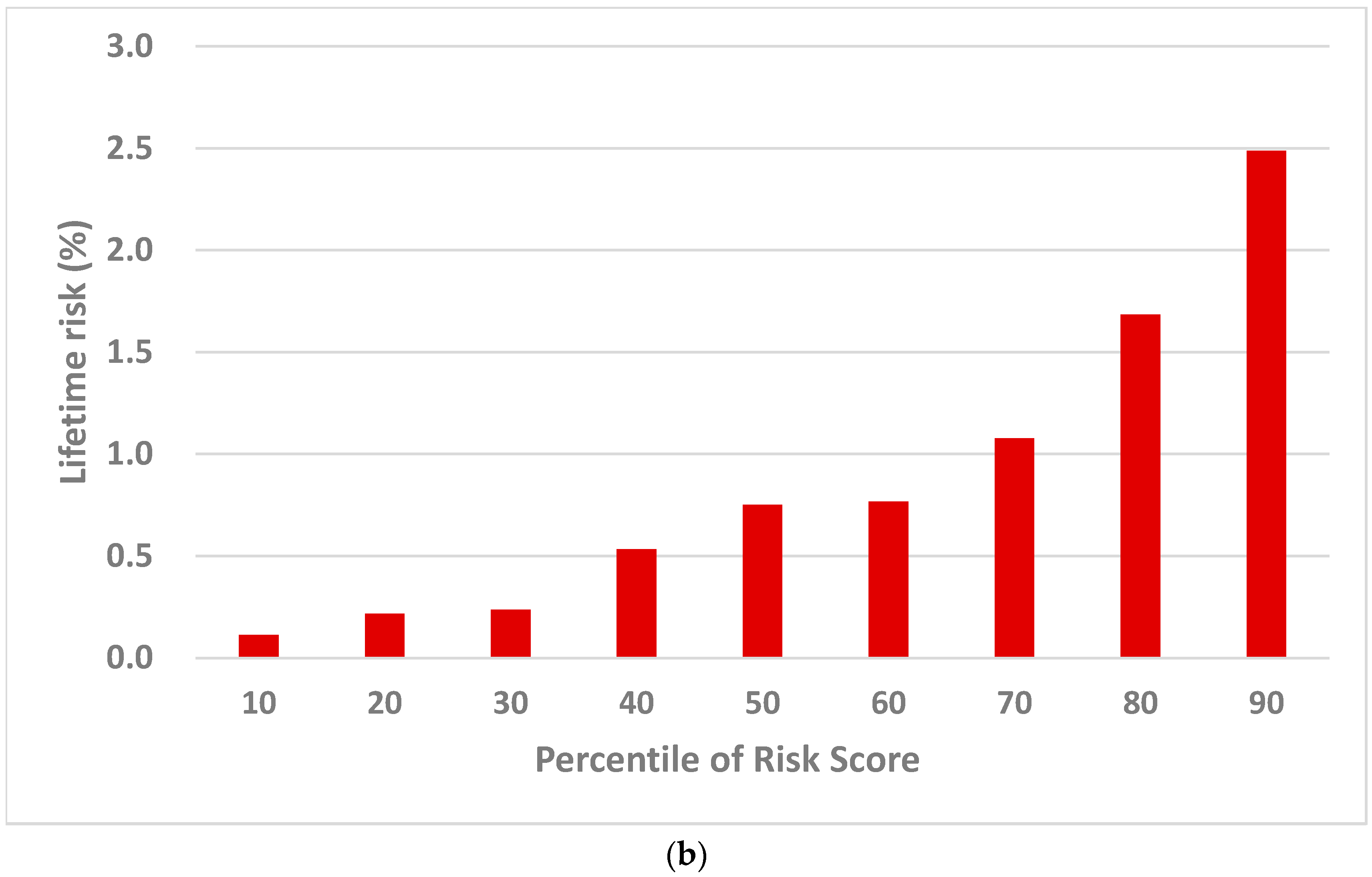

2.2.2. Population Risk Stratification

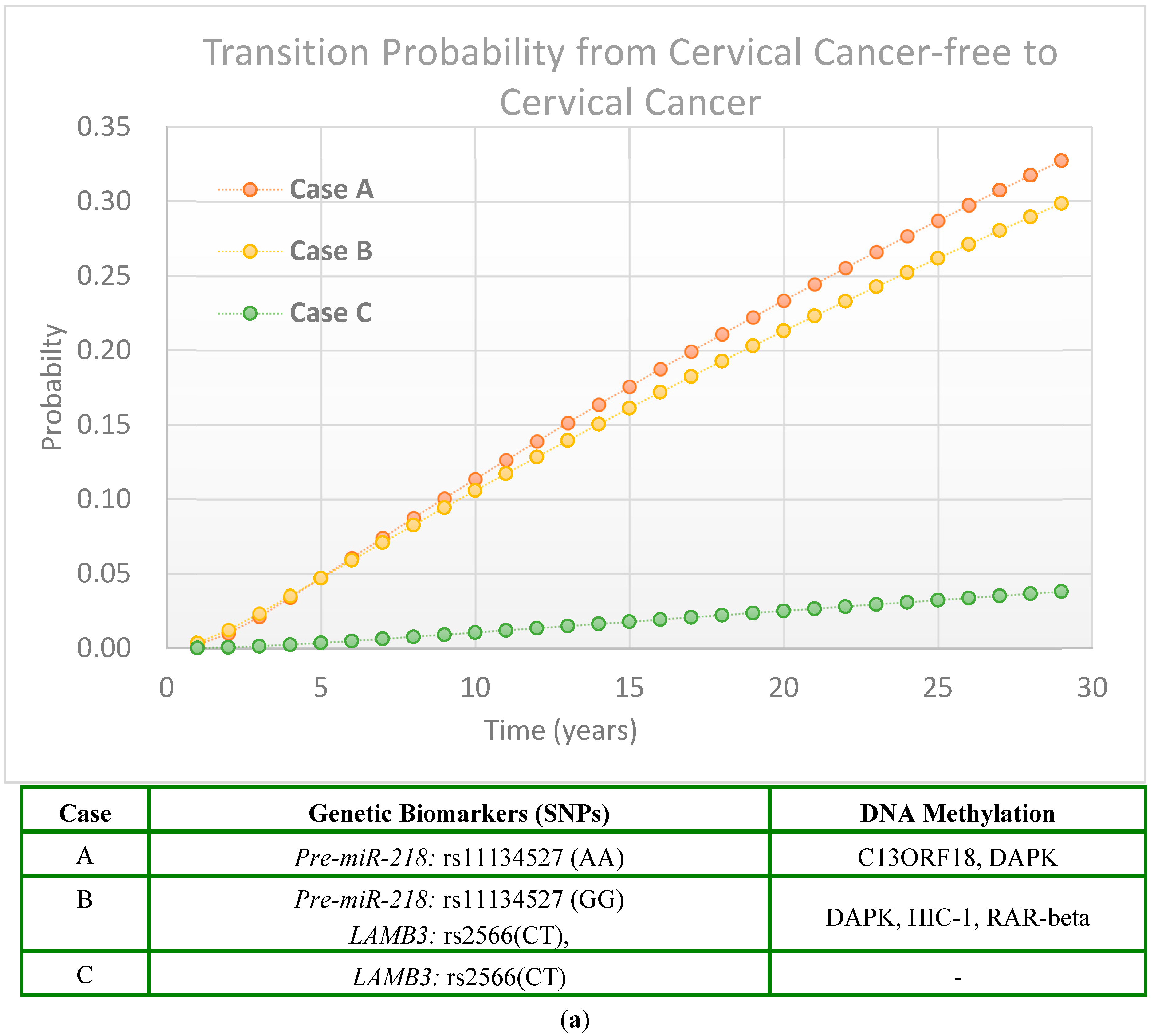

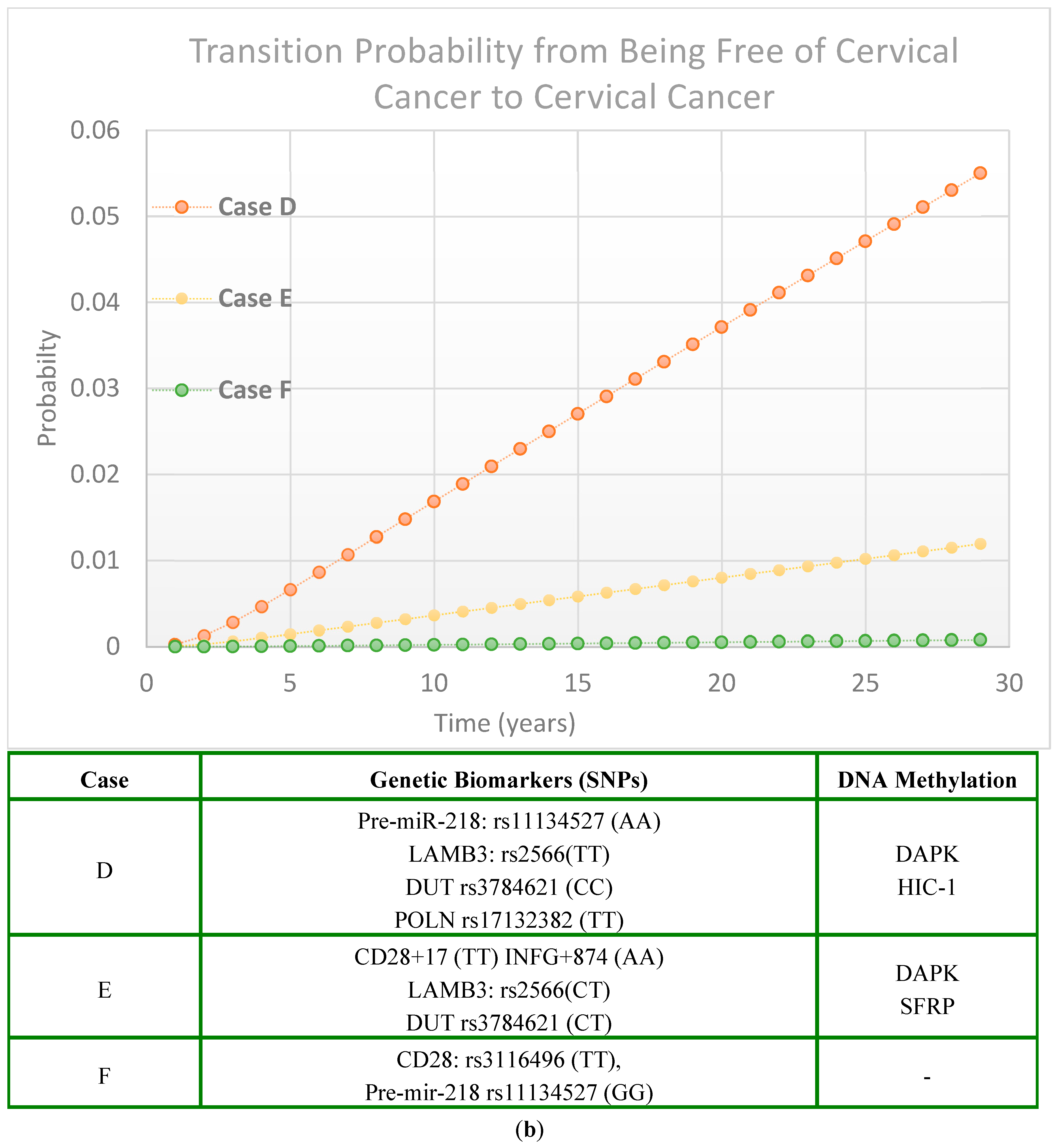

2.2.3. Scenarios of Personalized Risk Assessment

Women with HPV Infection

Women Without HPV Infection

2.3. Precision Cervical Cancer Prevention Strategies

2.3.1. Low-Risk Group

2.3.2. Intermediate Risk Group

2.3.3. High-Risk Group

3. Discussion

3.1. Genetic-Biomarkers-Supported Cervical HPV Infection-Precancerous-Cancer Process

3.2. Molecular Markers on the Risk of Cervical Cancer

3.3. Cervical Cancer Precision Prevention Guided by Risk Score Percentile

3.4. Limitations

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Population

4.2. Review-Based and Empirical-Based Parameters

4.3. Derivation of Risk Scores Driving Cervical Cancer Evolution

4.3.1. Genetic Biomarkers Associated with the Evolution of Cervical Cancer

4.3.2. Projection of Computer Simulation

4.4. Model Validation

4.5. Precision Intervention Strategies

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hakama, M.; Räsänen-Virtanen, U. Effect of a mass screening program on the risk of cervical cancer. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1976, 103, 512–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koong, S.L.; Yen, A.M.F.; Chen, T.H.H. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of nationwide cervical cancer screening in Taiwan. J. Med. Screen. 2006, 13 (Suppl. 1), S44–S47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.K.; Hung, H.F.; Duffy, S.; Yen, A.M.F.; Chen, H.H. Cost-effectiveness analysis for Pap smear screening and human papillomavirus DNA testing and vaccination. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2011, 17, 1050–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malagón, T.; Franco, E.L.; Tejada, R.; Vaccarella, S. Epidemiology of HPV-associated cancers past, present and future: To-wards prevention and elimination. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 21, 522–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.; Kennedy, E.B.; Dunn, S.; McLachlin, C.M.; Fung, M.F.K.; Gzik, D.; Shier, M.; Paszat, L. HPV testing in primary cervical screening: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2012, 34, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, P.T.; Kennedy, C.E.; de Vuyst, H.; Narasimhan, M. Self-sampling for human papillomavirus (HPV) testing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Glob. Health 2019, 4, e001351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, Y.S.; Clark, M.; Carson, E.; Weeks, L.; Moulton, K.; Mcfaul, S.; McLauchlin, C.; Tsoi, B.; Majid, U.; Kandasamy, S.; et al. HPV Testing for Primary Cervical Cancer Screening: A Health Technology Assessment; Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2019. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK543088/ (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Cherif, A.; Ovcinnikova, O.; Palmer, C.; Engelbrecht, K.; Reuschenbach, M.; Daniels, V. Cost-Effectiveness of 9-Valent HPV Vaccination for Patients Treated for High-Grade Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia in the UK. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2437703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demarteau, N.; Tang, C.H.; Chen, H.C.; Chen, C.J.; Van Kriekinge, G. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of the Bivalent Compared with the Quadrivalent Human Papillomavirus Vaccines in Taiwan. Value Health 2012, 15, 622–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamadi, N.; Al-Salam, S.; Beegam, S.; Zaaba, N.E.; Elzaki, O.; Nemmar, A. Chronic Exposure to Two Regimens of Waterpipe Smoke Elicits Lung Injury, Genotoxicity, and Mitochondrial Impairment with the Involvement of MAPKs Activation in Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, A.; Gersh, M.; Skovronsky, G.; Moss, C. The Future of Cervical Cancer Screening. Int. J. Women’s Health 2024, 16, 1715–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekar, P.K.C.; Thomas, S.M.; Veerabathiran, R. The future of cervical cancer prevention: Advances in research and tech-nology. Explor. Med. 2024, 5, 384–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regional Office for South-East Asia. Accelerating the Elimination of Cervical Cancer as a Global Public Health Problem. 2019. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/327911 (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Global Strategy to Accelerate the Elimination of Cervical Cancer as a Public Health Problem. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240014107 (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Simms, K.T.; Keane, A.; Nguyen, D.T.N.; Caruana, M.; Hall, M.T.; Lui, G.; Gauvreau, C.; Demke, O.; Arbyn, M.; Basu, P.; et al. Benefits, harms and cost-effectiveness of cervical screening, triage and treatment strategies for women in the general population. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 3050–3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Chen, X.; Hu, L.; Han, S.; Qiang, F.; Wu, Y.; Pan, L.; Shen, H.; Li, Y.; Hu, Z. Polymorphisms involved in the miR-218-LAMB3 pathway and susceptibility of cervical cancer, a case-control study in Chinese women. Gynecol. Oncol. 2010, 117, 287–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, T.; Gao, Y.; Tan, W.; Ma, S.; Shi, Y.; Yao, J.; Guo, Y.; Yang, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Q.; et al. A six-nucleotide insertion-deletion polymorphism in the CASP8 promoter is associated with susceptibility to multiple cancers. Nat. Genet. 2007, 39, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivansson, E.L.; Juko-Pecirep, I.; Gyllensten, U.B. Interaction of immunological genes on chromosome 2q33 and IFNG in susceptibility to cervical cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2010, 116, 544–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.S.; Gonzalez, P.; Yu, K.; Porras, C.; Li, Q.; Safaeian, M.; Rodriguez, A.C.; Sherman, M.E.; Bratti, C.; Schiffman, M.; et al. Common genetic variants and risk for HPV persistence and progression to cervical cancer. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e8667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Eijsink, J.J.H.; Lendvai, A.; Volders, H.H.; Klip, H.; Buikema, H.J.; van Hemel, B.M.; Schuuring, E.; van der Zee, A.G.; Wisman, G.B.A. Methylation markers for CCNA1 and C13ORF18 are strongly associated with high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cervical cancer in cervical scrapings. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2009, 18, 3000–3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, M.-T.; Sytwu, H.-K.; Yan, M.-D.; Shih, Y.-L.; Chang, C.-C.; Yu, M.-H.; Chu, T.-Y.; Lai, H.-C.; Lin, Y.-W. Promoter methylation of SFRPs gene family in cervical cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2009, 112, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, H.; Ha, K.T.; Pham, T.T.; Espinoza, J.L. Genetic Predisposition to Persistent Human Papillomavirus-Infection and Virus-Induced Cancers. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Aliani, A.; El-Abid, H.; El Mallali, Y.; Attaleb, M.; Ennaji, M.M.; El Mzibri, M. Association between Gene Promoter Meth-ylation and Cervical Cancer Development: Global Distribution and A Meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2021, 30, 450–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agodi, A.; Barchitta, M.; Quattrocchi, A.; Maugeri, A.; Vinciguerra, M. DAPK1 Promoter Methylation and Cervical Cancer Risk: A Systematic Review and a Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0135078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.Y.; Yen, M.F.; Yu, C.P.; Chen, H.H. Individually tailored screening of breast cancer with genes, tumour phenotypes, clinical attributes, and conventional risk factors. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 108, 2241–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Yu, Y.; Tan, Y.; Wan, H.; Zheng, N.; He, Z.; Mao, L.; Ren, W.; Chen, K.; Lin, Z.; et al. Artificial intelligence enables precision diagnosis of cervical cytology grades and cervical cancer. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Zhu, G.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, B.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, T. Predictive models for personalized precision medical intervention in spontaneous regression stages of cervical precancerous lesions. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothberg, M.B.; Hu, B.; Lipold, L.; Schramm, S.; Jin, X.W.; Sikon, A.; Taksler, G.B. A risk prediction model to allow personalized screening for cervical cancer. Cancer Causes Control 2018, 29, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elvatun, S.; Kanoors, D.; Nygård, M. Cross-population evaluation of cervical cancer risk prediction algorithms. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2024, 181, 105297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Lu, Z.; Yang, T.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Tuo, X.; Wang, J.; Lin, S.; Cai, H.; Cheng, H.; et al. Development, validation, and clinical application of a machine learning model for risk stratification and management of cervical cancer screening based on full-genotyping hrHPV test (SMART-HPV): A modelling study. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 2025, 55, 101480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Choi, Y.D.; Lee, J.S.; Lee, J.H.; Nam, J.H.; Choi, C. Assessment of DNA methylation for the detection of cervical neo-plasia in liquid-based cytology specimens. Gynecol. Oncol. 2010, 116, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, S.J.; Fullerton, S.M. Population genomic screening: Ethical considerations to guide age at implementation. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 899648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.J.; Chen, H.H.; Chang, S.H. Assessing chronic disease progression using non-homogeneous exponential regression Markov models: An illustration using a selective breast cancer screening in Taiwan. Stat. Med. 2002, 21, 3369–3382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.Y.; Yen, M.F.; Yu, C.P.; Chen, H.H. Risk assessment of multistate progression of breast tumor with state-dependent genetic and environmental covariates. Risk Anal. 2014, 34, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, C.H.; Hsu, W.F.; Yen, M.F.; Chen, H.H. Sampling-based Markov regression model for multistate disease progression: Applications to population-based cancer screening program. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2020, 29, 2198–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pharoah, P.D.; Antoniou, A.C.; Easton, D.F.; Ponder, B.A.J. Polygenes, risk prediction, and targeted prevention of breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 2796–2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cáceres-Durán, M.Á.; Ribeiro-Dos-Santos, Â.; Vidal, A.F. Roles and Mechanisms of the Long Noncoding RNAs in Cervical Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, G.Y.; Bierman, R.; Beardsley, L.; Chang, C.J.; Burk, R.D. Natural history of cervicovaginal papillomavirus infection in young women. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 338, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, E.L.; Villa, L.L.; Sobrinho, J.P.; Prado, J.M.; Rousseau, M.; Désy, M.; Rohan, T.E. Epidemiology of acquisition and clearance of cervical human papillomavirus infection in women from a high-risk area for cervical cancer. J. Infect. Dis. 1999, 180, 1415–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscicki, A.B.; Hills, N.; Shiboski, S.; Powell, K.; Jay, N.; Hanson, E.; Miller, S.; Clayton, L.; Farhat, S.; Broering, J.; et al. Risks for incident human papillomavirus infection and low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion development in young females. JAMA 2001, 285, 2995–3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodman, C.B.; Collins, S.; Winter, H.; Bailey, A.; Ellis, J.; Prior, P.; Yates, M.; Rollason, T.P.; Young, L.S. Natural history of cervical human papillomavirus infection in young women: A longitudinal cohort study. Lancet 2001, 357, 1831–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, K.K.; Hughes, J.P.; Kuypers, J.M.; Kiviat, N.B.; Lee, S.; Adam, D.E.; Koutsky, L.A. Concurrent and sequential acquisition of different genital human papillo-mavirus types. J. Infect. Dis. 2000, 182, 1097–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifford, G.M.; Gallus, S.; Herrero, R.; Muñoz, N.; Snijders, P.; Vaccarella, S.; Anh, P.; Ferreccio, C.; Hieu, N.; Matos, E.; et al. Worldwide distribution of human papillomavirus types in cytologically normal women in the International Agency for Research on Cancer HPV prevalence surveys: A pooled analysis. Lancet 2005, 366, 991–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICO/IARC. Papillomavirus, Human, Related Cancers, Fact Sheet 2023; ICO/IARC Information Centre on HPV and Cancer: Barcelona, Spain, 2023. Available online: https://hpvcentre.net/statistics/reports/JPN_FS.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Palmer, M.; Saito, E.; Katanoda, K.; Sakamoto, H.; Hocking, J.S.; Brotherton, J.M.; Ong, J.J. The impact of alternate HPV vaccination and cervical screening strategies in Japan: A cost-effectiveness analysis. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 2024, 44, 101018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedall, S.L.; Goldstein, L.S.; Goldstain, A.; Goldstein, A.T. Cervical cancer screening: Past, present, and future. Sex. Med. Rev. 2020, 8, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, P.; Krishna, M.; Subbalakshmi, A.R.; Ramisetty, S.; Mohanty, A.; Kulkarni, P.; Horne, D.; Salgia, R.; Singhal, S.S. Emerging biomarkers and molecular targets for precision medicine in cervical cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Rev. Cancer 2024, 1879, 189106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| State Transition | Genetic Marker | RR | Population Proportion | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal → LSIL | CD28+17 (TT) INFG+874 (AA) | 0.78 | 23.60% | [18] |

| Pre-mir-218 rs11134527 (GG) (AA) | 0.73 0.86 | 17.81% 47.55% | [16] | |

| LAMB3 rs2566 (TT) (CT) | 1.80 1.59 | 10.19% 46.29% | [16] | |

| CASP8-652 6N del/del del/ins | 0.53 0.75 | 10.27% 39.79% | [17] | |

| DUT rs3784621 (CC) (CT) | 1.54 1.33 | 11.35% 43.50% | [19] | |

| GTF2H4 rs2894054 (AA) (AG) | 0.11 0.57 | 2.12% 24.24% | [19] | |

| OAS3 rs12302655 (AA) (AG) | 1.57 -- | 13.18% 0% | [19] | |

| SULF1 rs4737999 (AA) (AG) | 0.59 0.59 | 7.76% 38.35% | [19] | |

| HPV → LSIL | IFNG rs11177074 (CC) (CT) | 1.35 1.78 | 0.25% 8.71% | |

| POLN rs17132382 (TT) (CT) | 2.47 2.16 | 3.88% 27.43% | [19] | |

| TMC8 rs9893818 (AA) TMC6 (AC) | 1.57 - | 5.10% 0% |

| Methylation | Population Frequency | Relative Risk for | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal → LSIL | LSIL → HSIL | HSIL → Cancer | |||

| CCNA1 | 4.85% | 42.08 | - | - | [21] |

| C13ORF18 | 2.91% | 67.66 | - | - | [21] |

| SFRP | 4.44% | 3.92 | 1.06 | 18.37 | [22] |

| DAPK | 26.83% | 2.11 | 3.44 | 0.97 | [24] |

| HIC-1 | 24.39% | 2.72 | 1.66 | 0.99 | [24] |

| HIN-1 | 9.76% | 2.13 | 1.57 | 1.35 | [24] |

| MGMT | 2.44% | 1.29 | 4.07 | 2.47 | [24] |

| RAR-beta | 4.88% | 3.58 | 4.35 | 1.32 | [24] |

| RASSF1A | 4.88% | 2.77 | 2.31 | 1.27 | [24] |

| SHP-1 | 4.88% | 6.38 | 1.42 | 1.02 | [24] |

| Twist | 7.32% | 1.80 | 4.54 | 0.79 | [24] |

| Profiles | RR/ Baseline Hazard Rate of HPV (λ₀j) | Regression Coefficients (β)/ln(λ₀j) | Case A | Case B | Case C | Case D | Case E | Case F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD28+17 (TT) INFG+874 (AA) | 0.78 | −0.25 | V | V | ||||

| Pre-mir-218 rs11134527 (GG) | 0.73 | −0.31 | V | |||||

| Pre-mir-218 rs11134527 (AA) | 0.86 | −0.15 | V | V | ||||

| LAMB3 rs2566 (TT) | 1.80 | 0.59 | V | |||||

| LAMB3 rs2566 (CT) | 1.59 | 0.46 | V | V | V | |||

| CASP8-652 6N del/del | 0.53 | −0.63 | ||||||

| CASP8-652 6N del/ins | 0.75 | −0.29 | ||||||

| DUT rs3784621 (CC) | 1.54 | 0.43 | V | |||||

| DUT rs3784621 (CT) | 1.33 | 0.29 | V | |||||

| GTF2H4 rs2894054 (AA) | 0.11 | −2.21 | ||||||

| GTF2H4 rs2894054 (AG) | 0.57 | −0.56 | ||||||

| OAS3 rs12302655 (AA) | 1.57 | 0.45 | ||||||

| SULF1 rs4737999 (AA) | 0.59 | −0.53 | ||||||

| SULF1 rs4737999(AG) | 0.59 | −0.53 | ||||||

| IFNG rs11177074 (CC) | 1.35 | 0.30 | ||||||

| IFNG rs11177074 (CT) | 1.78 | |||||||

| POLN rs17132382 (CT) | 2.16 | 0.77 | ||||||

| POLN rs17132382 (TT) | 2.47 | 0.90 | V | |||||

| TMC8 rs9893818 (AA) | 1.57 | 0.45 | ||||||

| CCNA1 | 42.08 | 3.74 | ||||||

| C13ORF18 | 67.66 | 4.21 | V | |||||

| SFRP | 3.92 | 1.37 | V | |||||

| DAPK | 2.11 | 0.75 | V | V | V | V | ||

| HIC-1 | 2.72 | 1.00 | V | V | ||||

| HIN-1 | 2.13 | 0.76 | ||||||

| MGMT | 1.29 | 0.25 | ||||||

| RAR-beta | 3.58 | 1.28 | V | |||||

| RASSF1A | 2.77 | 1.02 | ||||||

| SHP-1 | 6.38 | 1.85 | ||||||

| Twist | 1.80 | 0.59 | ||||||

| Persistent HPV infection Status | λ₀j Positive (j = 1): 0.135 Negative (j = 0): 0.051 | ln(λ₀j) Positive (j = 1): −2.00 Negative (j = 0): −2.98 | Positive | Positive | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| Risk Score (log(λ0j)+) | - | - | 2.81 | 1.16 | −1.55 | 0.57 | −0.36 | −3.53 |

| Percentile of Risk | - | - | >80% | >80% | 40–60% | 60–80% | 60–80 | <20 |

| RR (vs. Triennial Pap Smear) | - | - | 0.61 (0.53–0.71) 1 p < 0.001 | 0.61 (0.53–0.71) 1 p < 0.001 | 0.83 (0.71–0.97) 2 p = 0.02 | 0.55 (0.48, 0.64) 3 p < 0.001 | 0.55 (0.48, 0.64) 3 p < 0.001 | 1.02 (0.71, 1.46) 4 p = 0.93 |

| Relative Risk (95% CI) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk Score Percentile | <20% | 20–40% | 40–60% | 60–80% | >80% | |||||

| Prevention Strategy | HPV Testing | HPV Testing | HPV Testing | HPV Testing | HPV Testing | |||||

| − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | |

| Pap Smear Screening by Inter-screening Interval | ||||||||||

| 1 yr | 0.37 | 0.31 | 0.33 | 0.28 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.44 | 0.40 | 0.42 | 0.44 |

| (0.28,0.49) | (0.28,0.39) | (0.31,0.39) | (0.40,0.48) | (0.38,0.47) | (0.23,0.41) | (0.24,0.34) | (0.31,0.39) | (0.36,0.44) | (0.40,0.48) | |

| 3 yr | 0.45 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.33 | 0.40 | 0.33 | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.51 | 0.45 |

| (0.34,0.58) | (0.30,0.41) | (0.36,0.45) | (0.42,0.51) | (0.47,0.56) | (0.27,0.47) | (0.28,0.39) | (0.29,0.37) | (0.42,0.50) | (0.41,0.50) | |

| 5 yr | 0.44 | 0.42 | 0.43 | 0.41 | 0.42 | 0.39 | 0.50 | 0.46 | 0.54 | 0.48 |

| (0.34,0.57) | (0.37,0.49) | (0.38,0.47) | (0.46,0.54) | (0.50,0.60) | (0.33,0.54) | (0.36,0.48) | (0.35,0.43) | (0.42,0.50) | (0.44,0.53) | |

| HPV Vaccination + Pap Smear Screening by Inter-screening Interval | ||||||||||

| 1 yr | 0.32 | 0.28 | 0.15 | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.29 | 0.30 |

| (0.23,0.46) | (0.20,0.40) | (0.11,0.19) | (0.15,0.24) | (0.18,0.25) | (0.17,0.24) | (0.21,0.27) | (0.20,0.27) | (0.25,0.33) | (0.27,0.35) | |

| 3 yr | 0.32 | 0.29 | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.26 | 0.23 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.36 | 0.32 |

| (0.23,0.46) | (0.20,0.41) | (0.19,0.30) | (0.17,0.27) | (0.23,0.31) | (0.20,0.27) | (0.22,0.29) | (0.22,0.29) | (0.32,0.41) | (0.28,0.36) | |

| 5 yr | 0.39 | 0.34 | 0.27 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.24 | 0.28 | 0.26 | 0.36 | 0.32 |

| (0.28,0.54) | (0.25,0.48) | (0.22,0.33) | (0.16,0.25) | (0.21,0.29) | (0.21,0.28) | (0.24,0.32) | (0.23,0.30) | (0.32,0.41) | (0.28,0.37) | |

| HPV Vaccination | ||||||||||

| 0.94 | 0.96 | 0.55 | 0.61 | 0.57 | 0.58 | 0.64 | 0.58 | 0.73 | 0.70 | |

| (0.73,1.20) | (0.76,1.21) | (0.47,0.65) | (0.52,0.71) | (0.51,0.63) | (0.52,0.65) | (0.58,0.70) | (0.53,0.64) | (0.66,0.81) | (0.63,0.77) | |

| Marginal effect of Vaccination | 3–8% | 8–12% | 10–17% | 17–22% | 13–18% | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Siewchaisakul, P.; Fann, J.C.-Y.; Chen, M.-K.; Hsu, C.-Y. Genetic Biomarkers Associated with Dynamic Transitions of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Infection–Precancerous–Cancer of Cervix for Navigating Precision Prevention. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6016. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26136016

Siewchaisakul P, Fann JC-Y, Chen M-K, Hsu C-Y. Genetic Biomarkers Associated with Dynamic Transitions of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Infection–Precancerous–Cancer of Cervix for Navigating Precision Prevention. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(13):6016. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26136016

Chicago/Turabian StyleSiewchaisakul, Pallop, Jean Ching-Yuan Fann, Meng-Kan Chen, and Chen-Yang Hsu. 2025. "Genetic Biomarkers Associated with Dynamic Transitions of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Infection–Precancerous–Cancer of Cervix for Navigating Precision Prevention" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 13: 6016. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26136016

APA StyleSiewchaisakul, P., Fann, J. C.-Y., Chen, M.-K., & Hsu, C.-Y. (2025). Genetic Biomarkers Associated with Dynamic Transitions of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Infection–Precancerous–Cancer of Cervix for Navigating Precision Prevention. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(13), 6016. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26136016