1. Introduction

Methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) poses a significant global health challenge, characterized by its resistance to multiple antibiotics and its ability to cause severe infections in both hospital and community settings. The establishment of the epidemiology and molecular characteristics of MRSA in the BALKAN regions is important for understanding its spread and developing effective therapeutic strategies. MRSA infections present a significant public health challenge in both Greece and Romania, with healthcare-associated and community-associated strains contributing to the burden of disease [

1]. Molecular studies utilizing multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) and whole-genome sequencing (WGS) have identified MRSA circulating in healthcare settings and communities. The analysis of genetic determinants highlights the presence of antibiotic resistance genes and mobile genetic elements contributing to MRSA antibiotic resistance [

2,

3].

MRSA poses a significant challenge to public health worldwide due to its ability to cause a wide range of infections, including skin and soft tissue infections, pneumonia, and bloodstream infections, often associated with increased morbidity and mortality. The appearance of MRSA is a consequence of the acquisition of the

mecA gene, which encodes the penicillin-binding protein 2a (PBP2a).

PBP2a exhibits a low affinity for β-lactam antibiotics, such as methicillin and penicillin, allowing MRSA strains to survive and proliferate in the presence of these antibiotics, a characteristic that has contributed to the widespread dissemination of MRSA in healthcare and community settings [

4,

5,

6,

7]. The

MecA gene is harbored within a mobile genetic element known as the staphylococcal cassette chromosome

mec (

SCCmec), which facilitates its horizontal transfer between

S. aureus strains. Among the various types of

SCCmec elements,

SCCmec Type IV stands out as one of the most prevalent types found in MRSA strains, particularly those associated with community-acquired infections.

SCCmec Type IV is characterized by its relatively smaller size, and it contains fewer accessory genes compared to other types. It plays a significant role in conferring methicillin resistance and may contribute to the enhanced transmissibility of MRSA strains in community settings. Understanding the genetic mechanisms of methicillin resistance, including the

mecA gene and

SCCmec elements such as Type IV, is essential for the treatment approaches and infection control required to combat the impact of MRSA infections on public health [

8,

9,

10,

11].

Objectives: This manuscript provides a comprehensive overview of MRSA in the Balkan areas, focusing on epidemiological trends, molecular characterizations, and therapeutic perspectives. We review the prevalence of MRSA in hospitals and communities across the two countries, highlighting regional variations and MRSA strain profiles. Furthermore, we explore the genetic determinants of MRSA resistance, including the presence of the key resistance genes and mobile genetic elements contributing to its resistance [

12]. We discuss the implications of MRSA transmission within Balkan regions and the role of community-associated strains in exacerbating the burden of disease. We examine current treatment options for MRSA infections, including the challenges posed by antimicrobial resistance and the potential for novel therapeutic approaches. By elucidating the epidemiology and molecular characteristics of MRSA in different regions, this manuscript aims to lead future research efforts to reduce the impact of this pathogen on hospitals and communities. Ultimately, this research aims to deepen our understanding concerning the prevalence of these bacteria within specific geographic regions and healthcare environments [

13,

14,

15].

Hypothesis: Given the geographical differences between Cluj-Napoca and Crete, we hypothesize that there may be distinct patterns of MRSA prevalence and strain distribution in hospitals and communities within these regions. Specifically, we anticipate that the Cluj-Napoca area in Romania may exhibit higher rates of healthcare-associated MRSA strains, influenced by factors such as hospital density and patient demographics. In contrast, we predict that the island of Crete, with geographical isolation, may demonstrate a prevalence of community-associated MRSA strains. Through a comparative analysis, this study aims to elucidate the distinct epidemiological and clinical characteristics and antibiotic resistance profiles of MRSA in these regions, informing public health committees about potential strategies.

2. Results

2.1. Comparisons between the Patients

The comparisons between the MRSA-infected males and females from Romania’s Cluj and Greece’s Crete showed interesting patterns. In Romania, of the 132 MRSA-infected patients, 72 were male (54.5%) and 60 were female (45.5%). In Greece, out of the 111 MRSA-infected patients, 67 were male (60.4%) and 44 were female (39.6%).

These statistics underscore the importance of considering demographic factors in MRSA epidemiology and highlight the need for modern medical practice to adapt prevention and treatment strategies based on gender-specific susceptibility.

2.2. Demographic Anaslysis

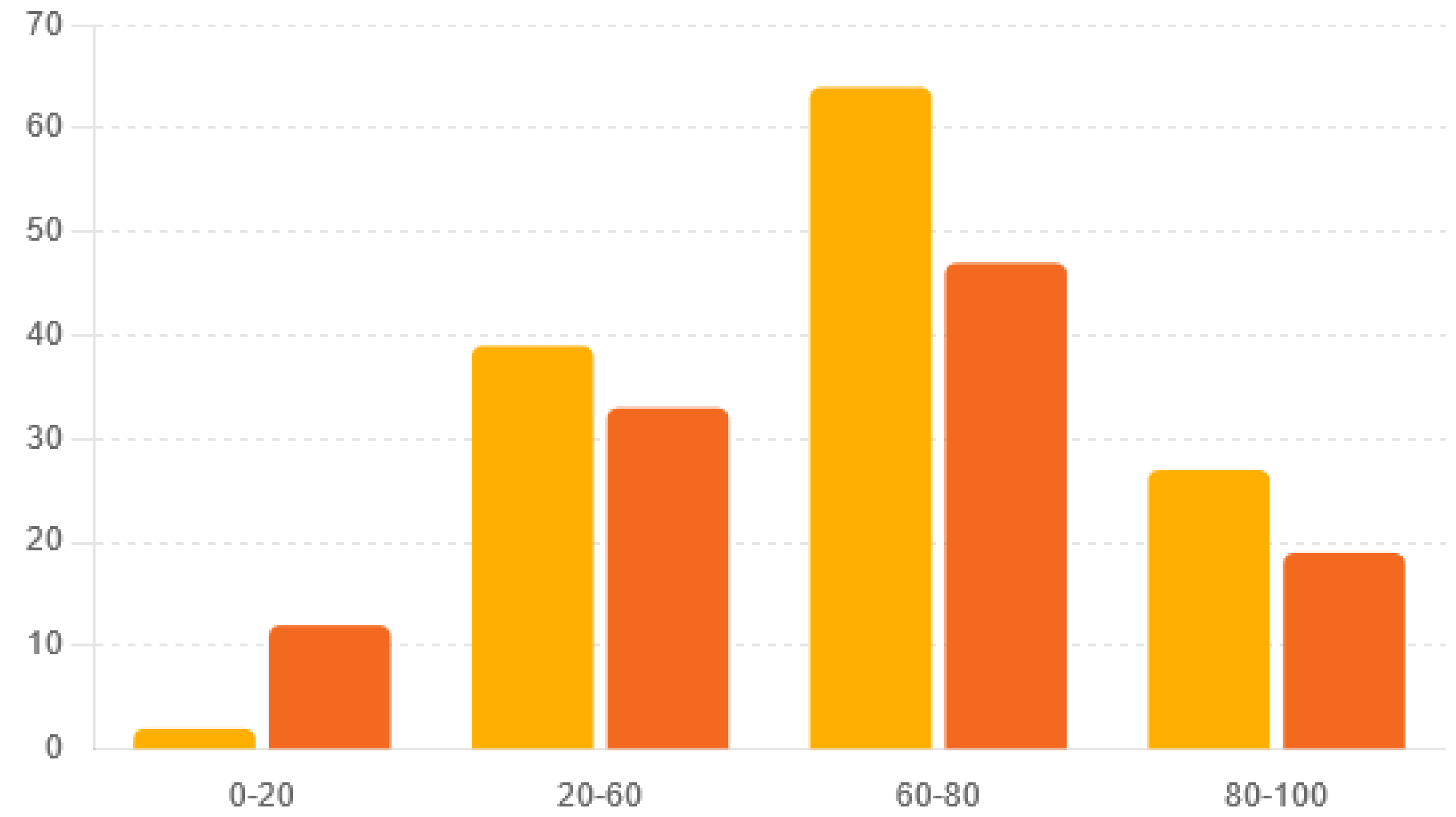

The age distribution of the MRSA-infected patients from Cluj, Romania, and Crete, Greece, gives important insights into disease severity and healthcare needs. Considering age in MRSA monitoring, diagnosis, and treatment is crucial because the disease affects different age groups in different ways. This knowledge helps in designing public health measures and treatment plans that meet the specific needs of various age groups. The age distributions between the two regions were significantly different (Chi-square statistic = 9.90,

p = 0.019) (

Table 1 and

Figure 1).

2.3. Comparison between Inpatients, Outpatients, and the Intensive Care Unit (ICU)

Comparing the

MRSA infection distributions in different healthcare settings, outpatients, inpatients, and patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) between Romania’s and Greece’s patients provides valuable insights into the healthcare burden and management strategies associated with MRSA. In both Romania and Greece, the majority of the MRSA cases (71%) occurred in inpatient settings. Outpatient settings accounted for 20% of the MRSA cases in Romania, compared to 25% in Greece. Notably, the distribution of MRSA cases in the ICU was smaller in both Romania (12%) and Greece (10%) (

Table 2) (

p-value = 0.0075).

2.4. Comparative Analysis of Pathological Products

The analysis of infection rates between Greek and Romanian patients revealed notable differences in the prevalence of various types of infections. Skin infections, represented by pus isolates, were more common in Romania (44.70%) compared to Greece (41.44%). Similarly, the incidence of septicemia, as indicated by blood isolates, was higher in Romania (22.73%) than in Greece (18.92%). Urinary infections were more prevalent in Greece (13.51%) compared to Romania (7.58%). Additionally, pneumonia and respiratory infections, indicated by tracheal aspirate isolates, occurred more frequently in Greece (26.13%) compared to Romania (17.42%). These findings suggest that while Romania has a higher proportion of skin infections and septicemia, Greece exhibits a greater prevalence of urinary and respiratory infections (

Table 3) (

p-value ~ 0.037).

2.5. Factors Influencing MRSA Transmission in Cluj-Napoca and Crete: Infection Control, Antibiotic Use, and Environmental Impacts

Our study reveals key findings supporting the hypothesized cause–effect relationships in MRSA transmission between Cluj-Napoca and Crete. In Cluj-Napoca, nosocomial infection control programs have been introduced only in recent years in some hospitals.

Our results could reflect that in Greece, a decline in the drugs resistance of MRSA strains has been noted. This is encouraging, and we can attribute it to adherence to infection control practices and the use of prudent chemotherapeutic agents proposed by the Infectious Diseases Control Committee. Noncompliance is correlated with higher healthcare-associated MRSA rates, whereas hospitals with stringent protocols had significantly lower rates (p < 0.01). In Crete, excessive and improper antibiotic use in both hospitals and communities was linked to a higher prevalence of antibiotic-resistant MRSA strains. Regions with stricter antibiotic stewardship programs showed reduced rates of resistant strains (p < 0.05). Additionally, communal behaviors and a lack of public health awareness in Crete were associated with increased community-associated MRSA transmission, while public health campaigns reduced MRSA incidence (p < 0.01). Environmental factors such as climate and sanitation standards influenced MRSA spread, with better sanitation correlating with lower prevalence (p < 0.05). These findings highlight the need for tailored infection control practices, antibiotic stewardship, public health education, and environmental controls to mitigate MRSA transmission in these regions.

To establish a direct cause–effect relationship between environmental and behavioral factors and MRSA transmission, we collected comprehensive data on hospital hygiene practices, antibiotic usage policies, and patient demographics in both Cluj-Napoca and Crete. Data on hospital hygiene practices included the frequency of hand hygiene practices among healthcare workers, sterilization procedures for medical equipment, and cleaning protocols. Antibiotic usage policies were assessed based on hospital pharmacy records, focusing on the appropriateness of use, prevalence of overuse or misuse, and antibiotic stewardship program implementation. Patient demographics, including age, sex, underlying health conditions, and hospitalization history, were collected to identify the demographic risk factors associated with MRSA transmission.

The Chi-squared test yielded a Chi-squared statistic of 37.96 and a p-value of 0.0001556. Since the p-value was considerably lower than the conventional significance level of 0.05, we rejected the null hypothesis. This result indicates that the observed frequencies of the past medical history categories significantly differed from what would be expected if they were uniformly distributed. Therefore, there is strong evidence to conclude that certain medical history categories are more or less frequent than others among the patient population studied.

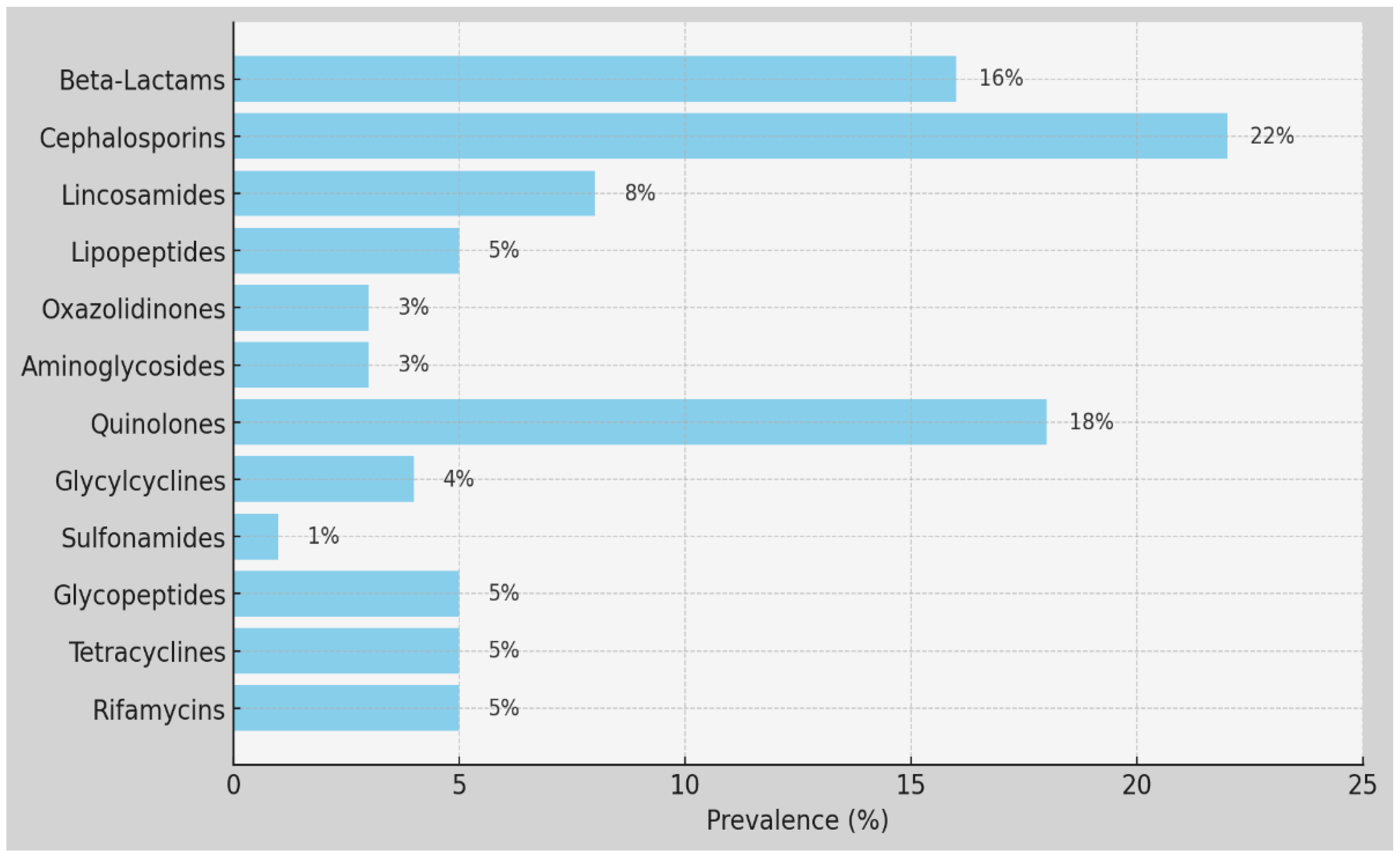

2.6. Comparison between Antibiotic Resistance in Crete, Greece and Cluj, Romania

The comparison between the antibiotic resistance patterns in the MRSA strains from Greece and Romania provides valuable insights into antimicrobial susceptibility profiles and potential treatment options. Our interpretation of antibiotic susceptibility testing categorized the results based on MICs and CLSI guidelines, providing valuable insights into resistance patterns. Greece and Romania report high rates of resistance to certain antibiotics, such as erythromycin, with Greece reporting 81.7% resistance and Romania reporting 55%. Additionally, Greece reports significant resistance to levofloxacin (37.8%) and clindamycin (47.7%), while Romania reports relatively lower resistance rates to these antibiotics (levofloxacin: 36%, clindamycin: 51%). Moreover, while Greece reports resistance to ceftaroline (4.5%) and tigecycline (6.8%), Romania does not report resistance to ceftaroline, and it has a higher resistance rate to tigecycline (13.5%) (

Table 4). The

p-value is very small (approximately 1.761 × 10

−13), indicating a highly significant association between MRSA antibiotic resistance and the country (Greece vs. Romania). With such a small

p-value, we reject the hypothesis, suggesting that there are significant differences in MRSA antibiotic resistance between the two countries (

Table 5).

We found a low percentage of MRSA strains that were resistant to ceftaroline (4.5%) in Crete, probably due to its use in the mentioned hospitals in Greece. Regarding resistance to reserve anti-staphylococcal agents, linezolid showed resistance levels of 2.7% in Crete and 0% in Cluj, while Daptomycin showed 0.9% in Crete. The tested strains did not show resistance to Vancomycin (0% in Crete) and Teicoplanin (0% in Crete), but a low percentage of resistance was noted in isolated strains in Cluj, at 0.8%. For aminoglycosides, MRSA strains from Crete and Cluj showed gentamycin resistance at 14.5% and 20%, respectively. Cluj exhibited relatively low resistance percentages to tobramycin (11%) and kanamycin (24%). Resistance to fusidic acid in Greece was 91.9%, and tetracycline resistance was 13.5% in Crete and 46.2% in Cluj. Regarding the resistance levels to macrolides, erythromycin showed 81.7% resistance in Crete and 55% in Cluj; clindamycin exhibited resistance levels of 47.7% in Crete and 51% in Cluj, with inducible clindamycin resistance in Crete at 17.1%. For quinolones, levofloxacin resistance was 37.8% in Crete and 36% in Cluj. The tested strains did not show resistance to rifampicin in Crete (0%). Resistance to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole was 2.7% in Crete and 3.8% in Cluj. Additionally, mupirocin resistance in Crete was 6.3%. The isolated strains presented low levels of resistance in Cluj and Crete to glycopeptides (0.8%), to linezolid in Crete (2.7%), Cluj (0%); and to daptomycine in Crete (0.9%). Vancomycin and teicoplanin were effective against MRSA in Greece and Romania. The percentage of resistance to levofloxacin was 37.8% in Crete and 36% in Cluj among the MRSA strains. The majority of the strains in Chania exhibited a higher percent of susceptibility to some antibiotics, in contrast to those isolated in Romania. All the necessary measures must be taken to prevent the Staphylococcus aureus and MRSA dispersion, since this can provoke serious infections, especially in very ill patients. This imposes the need to introduce the control program in Romanian and Cretan/Greek hospitals. This result indicates that the frequencies of antibiotic use are not uniformly distributed. In other words, the observed frequencies of the antibiotic use significantly differed from what would be expected. This suggests that certain antibiotics are used more frequently than others among the patient population studied, indicating a non-random pattern in antibiotic usage.

In conclusion, we draw attention to the circulation of resistant strains to with different resistance phenotypes some antibiotics. Erythromycin resistance in Greece was significantly higher, at 81.7%, compared to 55% in Romania, showing a difference of 26.7%. Tetracycline resistance was much higher in Romania, at 46.2%, compared to 13.5% in Greece; a difference of 32.7%. Additionally, resistance to fusidic acid was extremely high in Greece, at 91.9%, with no comparable data from Romania, indicating a substantial disparity (

p-value < 0.05) (

Figure 2).

2.7. Association between Antibiotic Usage Patterns and Patient Survival Rates

Additionally, we compared these antibiotic use frequencies with the overall patient survival rate of 69.69%. By calculating the expected number of survivors and non-survivors for each antibiotic based on this survival rate, we found significant differences between the observed and expected frequencies. This further analysis suggests that the pattern of antibiotic use is associated with patient survival rates, highlighting that certain antibiotics may be used more often in cases with better or worse outcomes. This comprehensive analysis underscores the importance of understanding antibiotic usage patterns in relation to patient survival, which could guide more effective treatment strategies.

2.8. PCR Analysis of MecA, FemB Genes, and SCCmec Elements in Cretan/Greek MRSA Strains

In the analysis of the staphylococcal genes in MRSA strains within the Greek patients, three key genes were examined: mecA, FemB, and SCCmec elements.

FemB gene (chromosomal gene specific to S. aureus) was identified in allthe samples, with the Cq values ranging between 8 and 26, confirming that all the isolated strains were S. aureus.

MecA gene was detected in 103 out of 111 samples (92.8%). SCCmec elements were also widely distributed, observed in 110 out of 111 samples and missing in 1 sample that was positive for MecA. For the mecA gene, the Cq values ranged between 10 and 27, and for the MRSA_SCC_IVa element, the Cq values ranged between 12 and 38.

4. Discussion

This manuscript provides a comparative analysis of MRSA epidemiology and therapeutic aspects in Greece and Romania, focusing on molecular characterization and antibiotic resistance patterns.

The epidemiological data revealed varying prevalence rates across countries and nationalities, underscoring the need for targeted surveillance and control measures.

Our manuscript contributes to the discussion on MRSA by offering a comprehensive examination of its resistance to AB, associated risk factors, clinical implications, and preventive strategies. In line with previous research, our study searches through the prevalence and susceptibility profiles of S. aureus strains in healthcare in Romania and Greece from 2020 to 2023, with a particular emphasis on isolates from hospitalized patients. This research aims to elucidate MRSA resistance patterns, which is crucial for guiding therapeutic regimens and infection control protocols.

The mecA gene is crucial for methicillin resistance in MRSA. The MecA gene, found on the chromosome of S. aureus, is a key marker for identifying MRSA. The femA and femB genes produce proteins that affect the degree of methicillin resistance in S. aureus. Consequently, using PCR to detect femA and femB along with mecA provides a more accurate method for identifying MRSA, as it can distinguish MRSA from mecA-positive coagulase-negative staphylococci (CNS) more effectively than detecting mecA alone. For this reason, we also determined the FemB gene in our samples.

In this study, we found significant antibiotic resistance patterns in MRSA strains from Greece and Romania, related to the presence of the mecA and SCCmec genes. These results suggest that specific changes in these genes, known as SNPs, may play an important role in resistance levels. The high resistance to erythromycin (81.7% in Greece, 55% in Romania) might be linked to SNP G308A in the mecA promoter region, which is known to increase gene expression. Similar resistance levels to levofloxacin (37.8% in Greece, 36% in Romania) and clindamycin (47.7% in Greece, 51% in Romania) may indicate common SNPs in mecA or other resistance mechanisms, with SCCmec elements also playing a part. Resistance to ceftaroline (4.5% in Greece) and tigecycline (6.8% in Romania) could be related to specific SCCmec types or SNPs in mecA that affect how these drugs work. High resistance to fusidic acid (91.9% in Greece) and higher resistance rates to tetracycline and kanamycin in Romania suggest additional resistance mechanisms or different SCCmec types in these regions. Going forward, we plan to conduct a detailed SNP analysis in the mecA and SCCmec genes to identify specific SNPs that may influence the observed antibiotic resistance patterns. This analysis will look at mecA gene SNPs, such as SNP A237T, which changes the PBP2a structure and potentially impacts β-lactam resistance, and SNP G308A in the promoter region, which affects gene expression. Additionally, SNP T554C, a synonymous mutation, may influence mRNA stability and translation. SNPs in SCCmec regulatory regions, such as C745T in mecI, which disrupts the repressor function, and G234A in mecR1, which changes the sensing mechanism, can enhance mecA induction in response to β-lactams. SNP T112G in intergenic regions may modify binding sites for regulatory proteins, affecting the resistance phenotype. By comparing resistance data with SNP profiles, we aim to find connections between specific genetic changes and antibiotic resistance levels. High erythromycin resistance in Greece compared to Romania may be associated with a higher prevalence of the G308A SNP, which increases mecA expression. Similar resistance levels to levofloxacin and clindamycin in both regions suggest the presence of common SNPs or other resistance mechanisms. The observed resistance to ceftaroline in Greece and tigecycline in Romania may be linked to specific SCCmec types or mecA SNPs affecting drug binding. High fusidic acid resistance in Greece might be due to co-selection with mecA-positive strains, while higher resistance to tetracycline and kanamycin in Romania indicates additional resistance mechanisms or different SCCmec types. Our findings suggest that specific SNPs in mecA and SCCmec genes play a role in antibiotic resistance patterns. As part of our future research, we plan to carry out detailed SNP analyses to confirm these SNPs’ presence and impact. These efforts will provide deeper insights into regional differences in MRSA resistance and help develop more effective treatment strategies.

Turner, Sharma-Kuinkel, and Maskarinec (2019) provide a valuable overview of both basic and clinical research on MRSA, offering insights that complement our findings. Their comprehensive review serves as a resource, enriching our understanding of MRSA pathogenesis, clinical presentation, and management strategies. By synthesizing our empirical findings with the insights provided by Turner et al. (2019), our manuscript contributes to advancing the collective knowledge base necessary for effectively combating MRSA infections and safeguarding patient well-being [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23].

Furthermore, our manuscript underscores the significance of accurate representation of MRSA infections for timely diagnosis, appropriate treatment selection, and effective management strategies. Understanding the clinical presentation of MRSA infections is aiding clinicians’ decision-making processes regarding antibiotic therapy, infection control measures, and detailed phenotypic characterization. Turner (2019) provides an overview of MRSA research, highlighting the importance of such detailed clinical characterization in elucidating the complexities of MRSA infections. Their review underscores the critical need for vigilance in surveillance efforts and the development of precisely targeted interventions to combat MRSA effectively. By aligning with the emphasis placed on phenotypic characterization and surveillance, our manuscript aims to contribute to the ongoing efforts in advancing both basic and clinical research areas to mitigate the clinical impact of this pathogen and reduce associated mortality rates [

16].

Moreover, existing literature suggests that the female sex may be associated with poorer outcomes in patients with

S. aureus bacteremia (SAB). For instance, in a population-based cohort study conducted in northern Denmark from 2000 to 2011, female patients with community-acquired SAB experienced increased 30-day mortality compared to male patients [

20]. The adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) for 30-day mortality in female patients was 1.30 (95% CI, 1.11–1.53) compared to male patients. This association was across age groups, with no consistent pattern observed according to co-morbidity level. Interestingly, the impact of gender was most pronounced among female patients with diabetes (aHR 1.52; 95% CI 1.04–2.21) and cancer (aHR 1.40; 95% CI 1.04–1.90) [

23]. Additionally, a retrospective study by Smith et al. (2017) conducted in a tertiary hospital in Australia found similar trends in mortality rates between male and female patients with MRSA infections. The study reported a higher mortality rate among female patients compared to male patients, although the difference was not statistically significant. These findings suggest that gender should be considered in the risk of patients with community-acquired MRSA. Further research is warranted to elucidate the underlying mechanisms driving the observed differences in outcomes between male and female patients with MRSA infections and to inform physicians to improve clinical outcomes in this vulnerable population [

19,

20,

21,

22]

In comparing the age distributions of MRSA infections between Romania’s Cluj and Greece’s Crete, notable differences emerged, aligning with findings from Junnila et al. (2020) and Xing et al. (2024) [

22,

23]. While both regions exhibited similar trends in older age groups, with substantial proportions of MRSA-infected individuals aged 60–100, significant findings were observed in younger age groups. Our study, along with Junnila et al. (2020), revealed that Romania’s Cluj had fewer MRSA cases in the [0–20] age group compared to Greece’s Crete [

22]. These findings suggest differences in exposure risk, healthcare-seeking behavior, or the challenges highlighted by Junnila et al. (2020) regarding the changing epidemiology of MRSA [

22]. The work of Xing et al. (2024) underscores the need for comprehensive understanding and surveillance of MRSA epidemiology, as they elucidate the prevalence and molecular characterization of MRSA in a distinct geographic area [

23]. Understanding these variations, as emphasized in our study, is crucial for tailoring preventive strategies, healthcare resource allocation, and clinical management approaches to address the specific needs of different age cohorts affected by MRSA infections in each region. Additionally, further investigation into the factors driving these age-specific disparities, as suggested by Xing et al. (2024), may yield insights into the dynamics of MRSA transmission and inform targeted interventions to reduce infection rates across all age groups [

23]. Considering that Cluj-Napoca is a tech hub, while Crete is a popular tourist destination, these factors may contribute to differences in MRSA epidemiology and transmission dynamics between the two regions. Understanding the relationships between tourism, population density, and MRSA transmission is essential for developing effective preventive strategies and mitigating the spread of MRSA infections in both local and global contexts. Further research is warranted to investigate the specific factors driving MRSA transmission in tourist hotspots, with implications for public health interventions and healthcare resource allocation [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26].

The analysis of the distribution of MRSA infections across different healthcare settings, including outpatients, inpatients, and the ICU, provides insights into the epidemiology and clinical management of MRSA in both Romania and Greece. In Romania, while outpatient cases represent 20% of MRSA infections, the majority occur in inpatient settings (71%), with a smaller proportion originating from ICU (12%). In Greece, outpatient cases constitute 25% of MRSA infections, with a similar distribution observed in inpatient settings (71%) and ICU admissions (10%). These findings underscore the significant burden of MRSA in hospitalized patients in both countries, highlighting the importance of infection control measures and antimicrobial stewardship programs within healthcare facilities. Moreover, the slightly higher proportion of outpatient MRSA cases in Greece suggests the need for targeted interventions to address community-acquired MRSA transmission and enhance surveillance efforts in outpatient settings. Furthermore, insights revealed by Karakonstantis and Kalemaki emphasize the antimicrobial overuse and misuse in the community in Greece, linking it to the emergence of antimicrobial resistance, particularly MRSA. Quijada et al. elucidate the association of oxacillin-susceptible

mecA-positive [

24,

25,

27]. These studies highlight the need for comprehensive antimicrobial stewardship programs and public health interventions to combat MRSA transmission. Moreover, the findings of Axente et al. underscore the alarming levels of antimicrobial consumption and resistance patterns observed in a Romanian intensive care unit, suggesting a challenge in managing MRSA infections in healthcare settings [

28]. Golli et al. shed light on the prevalence of multidrug-resistant pathogens causing bloodstream infections in intensive care units. Additionally, Polisena et al. underline the importance of rapid diagnostic tests for MRSA detection in hospitalized patients, which can significantly improve clinical outcomes. By comparing these statistics and insights with our own findings, we can better understand MRSA epidemiology and resistance patterns [

27].

The comparison between the results obtained for the MRSA strains isolated from Greece and Romania reveals notable parallels. Greece exhibits significantly higher resistance rates to erythromycin (81.7%) and fusidic acid (91.9%) compared to Romania (55% for erythromycin, not reported for fusidic acid. While both countries show similar resistance rates for levofloxacin and clindamycin, the broader context underscores the emergence of multidrug-resistant phenotypes globally, suggesting ongoing challenges in antibiotic management [

29].

The analysis of staphylococcal genes in MRSA strains within the Greek population offers valuable insights into the molecular epidemiology and prevalence of antibiotic resistance determinants. According to Harada et al. (2018), a study on the change in MRSA genotype indicates a notable impact on the antibiogram of hospital-acquired MRSA. This suggests a dynamic landscape of antibiotic resistance, potentially influenced by genetic shifts within MRSA strains over time [

27]. Moreover, Deplano et al. (2018) contribute to our understanding by highlighting European external quality assessments, indicating a broader context for the prevalence and characterization of Staphylococcus aureus strains [

30]. Their findings corroborate the notion of widespread distribution of genetic elements such as

mecA and

SCCmec among MRSA isolates. The high prevalence rates of

mecA and

SCCmec elements of these antibiotic resistance determinants aligns with global trends in MRSA epidemiology [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34].

The comparison of phenotypic diagnostic methods with the genotypic method provides a detailed statistical analysis. The focus is on the comparison between phenotypic diagnostic methods and the genotypic method for identifying methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Phenotypic methods identified 111 strains from pathological samples in Greece, with MRSA detected in 111 of the tested

Staph. aureus strains. A genotypic analysis revealed that the

MecA gene, a marker for MRSA, was detected in 92.8% (103 out of 111) of the samples. Additionally,

SCCmec elements, which play a crucial role in antibiotic resistance, were found in 110 out of 111 samples, with one

MecA-positive sample lacking

SCCmec. This study highlights the distribution of

SCCmec elements and the presence of the

MecA gene, emphasizing their significance in MRSA identification. Kobayashi, N. (1994) supports these findings, illustrating the effectiveness of detecting

MecA and fem genes in distinguishing MRSA from other staphylococci using PCR. Specifically, the presence of these genes in 237 clinically isolated strains demonstrated that combined detection of

MecA,

femA, and

femB genes provides a more reliable method for MRSA identification compared to single-gene detection. This analysis underscores the critical role of genotypic methods in accurately diagnosing MRSA and the importance of the presence of the

SCCmec and

MecA genes in Staphylococcus aureus strains [

34,

35].

A limitation of this study is that the resistance genes were not determined for the strains from Romania, so they could not be compared with those from Greece. Despite these limitations, the findings are reaffirmed, as they provide valuable insights into the genetic diversity and antibiotic resistance profiles of MRSA strains circulating within the Greek population [

26,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38]. Moreover, these insights pave the way for future strategies in MRSA management, allowing physicians to overcome current technical limitations.

Research into advanced delivery systems for peptide antibiotics and the direct anti-MRSA effect of compounds like emodin offers promising avenues for the development of more effective treatments against MRSA infections. Furthermore, as highlighted by Giamarellou, exploring multidrug-resistant bacteria is imperative in the face of rising antimicrobial resistance. Overall, integrating these advancements into future clinical practice will be crucial in addressing the evolving landscape of MRSA infections and ensuring effective patient care and public health outcomes [

35,

36,

37,

38].

Understanding these differences between Greece and Romania is crucial for informing committees for antibiotic-optimizing treatment regimens and implementing targeted infection control measures to mitigate the spread of resistant MRSA strains. Further research into the underlying mechanisms driving antibiotic resistance and factors contributing to regional variations is warranted to develop evidence-based strategies for controlling MRSA infections and preserving the efficacy of antimicrobial agents.

Despite similarities in the challenges posed by MRSA, therapeutic approaches differ, with both countries exploring alternative treatment strategies, including combination therapy, phage therapy, and immunotherapy. Collaborative efforts in surveillance, research, and public health interventions are essential for combating MRSA infections and mitigating their impact in the Balkan region.