Aging, Cellular Senescence, and Alzheimer’s Disease

Abstract

:1. Introduction

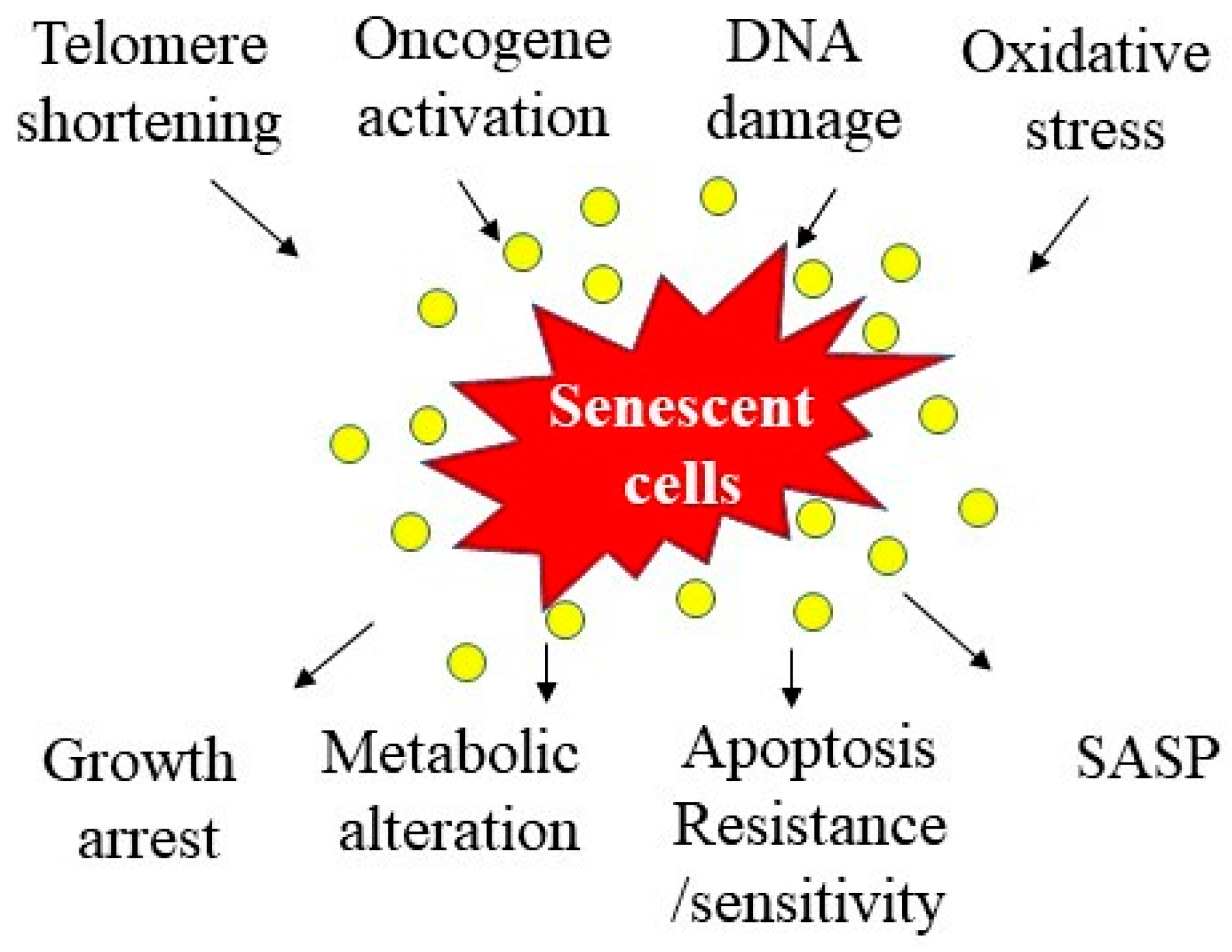

2. Cellular Senescence and Aging

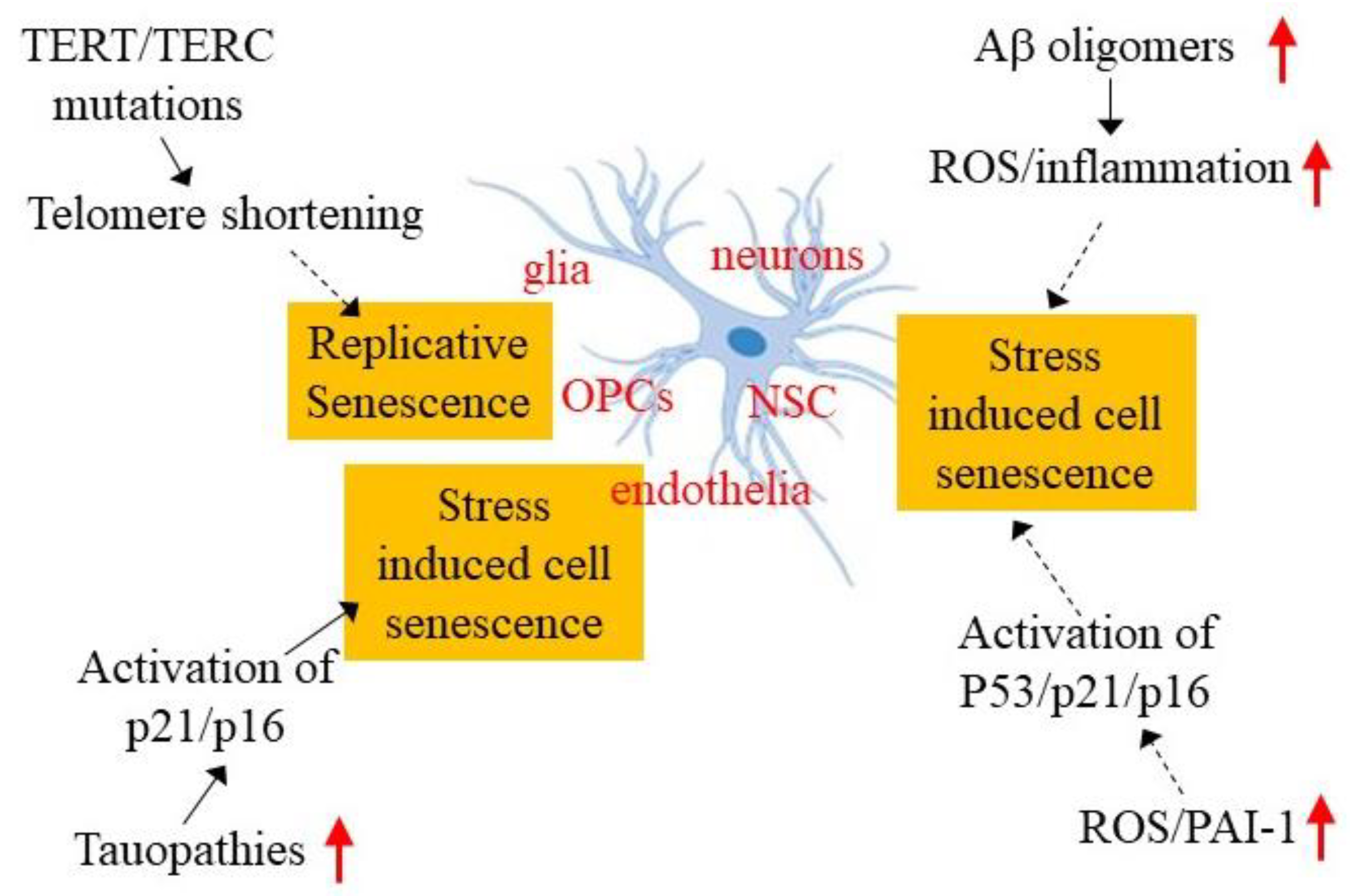

3. Cellular Senescence and Alzheimer’s Disease

3.1. Evidence of Cellular Senescence in AD Patients

3.2. Evidence of Cellular Senescence in AD Model Mice

3.3. Mice Overexpressing Amyloid Precursor Protein (APP)

3.4. Tau Transgenic Mice

4. Potential Mechanisms Underlying Brain Cellular Senescence in AD

4.1. Telomerase Deficiency and Telomere Shortening

4.2. Aβ Oligomers

4.3. Tauopathy

4.4. Oxidative Stress

4.5. Increased Expression of Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor 1 and Cell Senescence

5. Limitation and Future Directions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LOAD | Late-onset Alzheimer’s disease |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| Aβ | β-amyloid peptides |

| PAI-1 | Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 |

| RS | Replicative senescence |

| SIPS | Stress-induced premature senescence |

| SASP | Senescence-associated secretory phenotype |

| SA-β-gal | Senescence-associated β-galactosidase |

| pRb | Phosphorylated retinoblastoma protein |

| SAHFs | Senescence-associated heterochromatin foci |

| SDFs | Senescence-associated DNA damage foci |

| mH2A | MacroH2A |

| HSCs | Hematopoietic stem cells |

| NFTs | Neurofibrillary tangles |

| MCI | Mild cognitive impairment |

| LTL | Leukocyte telomere length |

| APP | Amyloid precursor protein |

| PS1 | Presenilin 1 |

| OPCs | Oligodendrocyte precursor cells |

| HMGB1 | High-mobility group box 1 |

| TERT | Telomerase reverse transcriptase |

| TERC | Telomerase RNA component |

| ATM | Ataxia-telangiectasia mutated |

| FAD | Familial AD |

| VEGF-1 | Vascular endothelial growth factor 1 |

| NSPCs | Neural stem/progenitor cells |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| NLRP3 | NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 |

| DAM | Disease-associated microglia |

| tPA | Tissue-type plasminogen activator |

| uPA | Urokinase-type plasminogen activator inhibitor |

| ATII | Alveolar type II cells |

| TGF-β1 | Transforming growth factor β1 |

| NSC | Neuronal stem cell |

References

- Campisi, J.; d’Adda di Fagagna, F. Cellular senescence: When bad things happen to good cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 729–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salama, R.; Sadaie, M.; Hoare, M.; Narita, M. Cellular senescence and its effector programs. Genes Dev. 2014, 28, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Campisi, J.; Kapahi, P.; Lithgow, G.J.; Melov, S.; Newman, J.C.; Verdin, E. From discoveries in ageing research to therapeutics for healthy ageing. Nature 2019, 571, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gorgoulis, V.; Adams, P.D.; Alimonti, A.; Bennett, D.C.; Bischof, O.; Bishop, C.; Campisi, J.; Collado, M.; Evangelou, K.; Ferbeyre, G.; et al. Cellular Senescence: Defining a Path Forward. Cell 2019, 179, 813–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhinn, M.; Ritschka, B.; Keyes, W.M. Cellular senescence in development, regeneration and disease. Development 2019, 146, dev151837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Calcinotto, A.; Kohli, J.; Zagato, E.; Pellegrini, L.; Demaria, M.; Alimonti, A. Cellular Senescence: Aging, Cancer, and Injury. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 1047–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacutu, R.; Budovsky, A.; Yanai, H.; Fraifeld, V.E. Molecular links between cellular senescence, longevity and age-related diseases—A systems biology perspective. Aging 2011, 3, 1178–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.J.; Wijshake, T.; Tchkonia, T.; LeBrasseur, N.K.; Childs, B.G.; van de Sluis, B.; Kirkland, J.L.; van Deursen, J.M. Clearance of p16Ink4a-positive senescent cells delays ageing-associated disorders. Nature 2011, 479, 232–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childs, B.G.; Durik, M.; Baker, D.J.; van Deursen, J.M. Cellular senescence in aging and age-related disease: From mechanisms to therapy. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 1424–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Childs, B.G.; Baker, D.J.; Wijshake, T.; Conover, C.A.; Campisi, J.; van Deursen, J.M. Senescent intimal foam cells are deleterious at all stages of atherosclerosis. Science 2016, 354, 472–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafer, M.J.; White, T.A.; Iijima, K.; Haak, A.J.; Ligresti, G.; Atkinson, E.J.; Oberg, A.L.; Birch, J.; Salmonowicz, H.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Cellular senescence mediates fibrotic pulmonary disease. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sturmlechner, I.; Durik, M.; Sieben, C.J.; Baker, D.J.; van Deursen, J.M. Cellular senescence in renal ageing and disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2017, 13, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, D.J.; Childs, B.G.; Durik, M.; Wijers, M.E.; Sieben, C.J.; Zhong, J.; Saltness, R.A.; Jeganathan, K.B.; Verzosa, G.C.; Pezeshki, A.; et al. Naturally occurring p16(Ink4a)-positive cells shorten healthy lifespan. Nature 2016, 530, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, M.; Pirtskhalava, T.; Farr, J.N.; Weigand, B.M.; Palmer, A.K.; Weivoda, M.M.; Inman, C.L.; Ogrodnik, M.B.; Hachfeld, C.M.; Fraser, D.G.; et al. Senolytics improve physical function and increase lifespan in old age. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1246–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerenu, G.; Martisova, E.; Ferrero, H.; Carracedo, M.; Rantamäki, T.; Ramirez, M.J.; Gil-Bea, F.J. Modulation of BDNF cleavage by plasminogen-activator inhibitor-1 contributes to Alzheimer’s neuropathology and cognitive deficits. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA-Mol. Basis Dis. 2017, 1863, 991–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosla, S.; Farr, J.N.; Tchkonia, T.; Kirkland, J.L. The role of cellular senescence in ageing and endocrine disease. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2020, 16, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Segura, A.; Nehme, J.; Demaria, M. Hallmarks of Cellular Senescence. Trends Cell Biol. 2018, 28, 436–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.J.; Petersen, R.C. Cellular senescence in brain aging and neurodegenerative diseases: Evidence and perspectives. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 1208–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ogrodnik, M.; Evans, S.A.; Fielder, E.; Victorelli, S.; Kruger, P.; Salmonowicz, H.; Weigand, B.M.; Patel, A.D.; Pirtskhalava, T.; Inman, C.L.; et al. Whole-body senescent cell clearance alleviates age-related brain inflammation and cognitive impairment in mice. Aging Cell 2021, 20, e13296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Li, D.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, M.; Lin, S.; Huang, L.; Chung, E.J.; Citrin, D.E.; et al. Inhibition of Bcl-2/xl With ABT-263 Selectively Kills Senescent Type II Pneumocytes and Reverses Persistent Pulmonary Fibrosis Induced by Ionizing Radiation in Mice. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2017, 99, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, M.; Korfei, M.; Mutze, K.; Klee, S.; Skronska-Wasek, W.; Alsafadi, H.N.; Ota, C.; Costa, R.; Schiller, H.B.; Lindner, M.; et al. Senolytic drugs target alveolar epithelial cell function and attenuate experimental lung fibrosis ex vivo. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 50, 1602367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Childs, B.G.; Li, H.; van Deursen, J.M. Senescent cells: A therapeutic target for cardiovascular disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 1217–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickson, L.J.; Langhi Prata, L.G.P.; Bobart, S.A.; Evans, T.K.; Giorgadze, N.; Hashmi, S.K.; Herrmann, S.M.; Jensen, M.D.; Jia, Q.; Jordan, K.L.; et al. Senolytics decrease senescent cells in humans: Preliminary report from a clinical trial of Dasatinib plus Quercetin in individuals with diabetic kidney disease. eBioMedicine 2019, 47, 446–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bussian, T.J.; Aziz, A.; Meyer, C.F.; Swenson, B.L.; van Deursen, J.M.; Baker, D.J. Clearance of senescent glial cells prevents tau-dependent pathology and cognitive decline. Nature 2018, 562, 578–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Kishimoto, Y.; Grammatikakis, I.; Gottimukkala, K.; Cutler, R.G.; Zhang, S.; Abdelmohsen, K.; Bohr, V.A.; Misra Sen, J.; Gorospe, M.; et al. Senolytic therapy alleviates Abeta-associated oligodendrocyte progenitor cell senescence and cognitive deficits in an Alzheimer’s disease model. Nat. Neurosci. 2019, 22, 719–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justice, J.N.; Nambiar, A.M.; Tchkonia, T.; LeBrasseur, N.K.; Pascual, R.; Hashmi, S.K.; Prata, L.; Masternak, M.M.; Kritchevsky, S.B.; Musi, N.; et al. Senolytics in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Results from a first-in-human, open-label, pilot study. eBioMedicine 2019, 40, 554–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Horvath, S.; Raj, K. DNA methylation-based biomarkers and the epigenetic clock theory of ageing. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2018, 19, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa, J.P.; Vitorino, R.; Silva, G.M.; Vogel, C.; Duarte, A.C.; Rocha-Santos, T. A synopsis on aging-Theories, mechanisms and future prospects. Ageing Res. Rev. 2016, 29, 90–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreiling, J.A.; Tamamori-Adachi, M.; Sexton, A.N.; Jeyapalan, J.C.; Munoz-Najar, U.; Peterson, A.L.; Manivannan, J.; Rogers, E.S.; Pchelintsev, N.A.; Adams, P.D.; et al. Age-associated increase in heterochromatic marks in murine and primate tissues. Aging Cell 2011, 10, 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, C.; Jurk, D.; Maddick, M.; Nelson, G.; Martin-Ruiz, C.; von Zglinicki, T. DNA damage response and cellular senescence in tissues of aging mice. Aging Cell 2009, 8, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calhoun, C.; Shivshankar, P.; Saker, M.; Sloane, L.B.; Livi, C.B.; Sharp, Z.D.; Orihuela, C.J.; Adnot, S.; White, E.S.; Richardson, A.; et al. Senescent Cells Contribute to the Physiological Remodeling of Aged Lungs. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biomed. Sci. Med. Sci. 2016, 71, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Janzen, V.; Forkert, R.; Fleming, H.E.; Saito, Y.; Waring, M.T.; Dombkowski, D.M.; Cheng, T.; DePinho, R.A.; Sharpless, N.E.; Scadden, D.T. Stem-cell ageing modified by the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p16INK4a. Nature 2006, 443, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molofsky, A.V.; Slutsky, S.G.; Joseph, N.M.; He, S.; Pardal, R.; Krishnamurthy, J.; Sharpless, N.E.; Morrison, S.J. Increasing p16INK4a expression decreases forebrain progenitors and neurogenesis during ageing. Nature 2006, 443, 448–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hou, Y.; Dan, X.; Babbar, M.; Wei, Y.; Hasselbalch, S.G.; Croteau, D.L.; Bohr, V.A. Ageing as a risk factor for neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2019, 15, 565–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winblad, B.; Amouyel, P.; Andrieu, S.; Ballard, C.; Brayne, C.; Brodaty, H.; Cedazo-Minguez, A.; Dubois, B.; Edvardsson, D.; Feldman, H.; et al. Defeating Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias: A priority for European science and society. Lancet Neurol. 2016, 15, 455–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saez-Atienzar, S.; Masliah, E. Cellular senescence and Alzheimer disease: The egg and the chicken scenario. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2020, 21, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McShea, A.; Harris, P.L.; Webster, K.R.; Wahl, A.F.; Smith, M.A. Abnormal expression of the cell cycle regulators P16 and CDK4 in Alzheimer’s disease. Am. J. Pathol. 1997, 150, 1933–1939. [Google Scholar]

- Bhat, R.; Crowe, E.P.; Bitto, A.; Moh, M.; Katsetos, C.D.; Garcia, F.U.; Johnson, F.B.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Sell, C.; Torres, C. Astrocyte senescence as a component of Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e45069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnquist, C.; Horikawa, I.; Foran, E.; Major, E.O.; Vojtesek, B.; Lane, D.P.; Lu, X.; Harris, B.T.; Harris, C.C. p53 isoforms regulate astrocyte-mediated neuroprotection and neurodegeneration. Cell Death Differ. 2016, 23, 1515–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wei, Z.; Chen, X.C.; Song, Y.; Pan, X.D.; Dai, X.M.; Zhang, J.; Cui, X.L.; Wu, X.L.; Zhu, Y.G. Amyloid beta Protein Aggravates Neuronal Senescence and Cognitive Deficits in 5XFAD Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Chin. Med. J. 2016, 129, 1835–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musi, N.; Valentine, J.M.; Sickora, K.R.; Baeuerle, E.; Thompson, C.S.; Shen, Q.; Orr, M.E. Tau protein aggregation is associated with cellular senescence in the brain. Aging Cell 2018, 17, e12840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holtzman, D.; Ulrich, J. Senescent glia spell trouble in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Neurosci. 2019, 22, 683–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X.; Zhang, T.; Liu, H.; Mi, Y.; Gou, X. Astrocyte Senescence and Alzheimer’s Disease: A Review. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2020, 12, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montine, T.J.; Phelps, C.H.; Beach, T.G.; Bigio, E.H.; Cairns, N.J.; Dickson, D.W.; Duyckaerts, C.; Frosch, M.P.; Masliah, E.; Mirra, S.S.; et al. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease: A practical approach. Acta Neuropathol. 2012, 123, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hyman, B.T.; Phelps, C.H.; Beach, T.G.; Bigio, E.H.; Cairns, N.J.; Carrillo, M.C.; Dickson, D.W.; Duyckaerts, C.; Frosch, M.P.; Masliah, E.; et al. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. J. Alzheimer’s Assoc. 2012, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Naderi, J.; Lopez, C.; Pandey, S. Chronically increased oxidative stress in fibroblasts from Alzheimer’s disease patients causes early senescence and renders resistance to apoptosis by oxidative stress. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2006, 127, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streit, W.J.; Braak, H.; Xue, Q.S.; Bechmann, I. Dystrophic (senescent) rather than activated microglial cells are associated with tau pathology and likely precede neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2009, 118, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garwood, C.J.; Simpson, J.E.; Al Mashhadi, S.; Axe, C.; Wilson, S.; Heath, P.R.; Shaw, P.J.; Matthews, F.E.; Brayne, C.; Ince, P.G.; et al. DNA damage response and senescence in endothelial cells of human cerebral cortex and relation to Alzheimer’s neuropathology progression: A population-based study in the Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing Study (MRC-CFAS) cohort. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2014, 40, 802–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaikwad, S.; Puangmalai, N.; Bittar, A.; Montalbano, M.; Garcia, S.; McAllen, S.; Bhatt, N.; Sonawane, M.; Sengupta, U.; Kayed, R. Tau oligomer induced HMGB1 release contributes to cellular senescence and neuropathology linked to Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia. Cell Rep. 2021, 36, 109419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Fryatt, G.L.; Ghorbani, M.; Obst, J.; Menassa, D.A.; Martin-Estebane, M.; Muntslag, T.A.O.; Olmos-Alonso, A.; Guerrero-Carrasco, M.; Thomas, D.; et al. Replicative senescence dictates the emergence of disease-associated microglia and contributes to Aβ pathology. Cell Rep. 2021, 35, 109228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortlever, R.M.; Higgins, P.J.; Bernards, R. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 is a critical downstream target of p53 in the induction of replicative senescence. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006, 8, 877–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elzi, D.J.; Lai, Y.; Song, M.; Hakala, K.; Weintraub, S.T.; Shiio, Y. Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1--insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3 cascade regulates stress-induced senescence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 12052–12057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wan, Y.Z.; Gao, P.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, Z.Q.; Hao, D.L.; Lian, L.S.; Li, Y.J.; Chen, H.Z.; Liu, D.P. SIRT1-mediated epigenetic downregulation of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 prevents vascular endothelial replicative senescence. Aging Cell 2014, 13, 890–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eren, M.; Boe, A.E.; Murphy, S.B.; Place, A.T.; Nagpal, V.; Morales-Nebreda, L.; Urich, D.; Quaggin, S.E.; Budinger, G.R.; Mutlu, G.M.; et al. PAI-1-regulated extracellular proteolysis governs senescence and survival in Klotho mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 7090–7095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jiang, C.; Liu, G.; Luckhardt, T.; Antony, V.; Zhou, Y.; Carter, A.B.; Thannickal, V.J.; Liu, R.M. Serpine 1 induces alveolar type II cell senescence through activating p53-p21-Rb pathway in fibrotic lung disease. Aging Cell 2017, 16, 1114–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, A.; Patel, D.; Lian, X.J.; Sadek, J.; Di Marco, S.; Pause, A.; Gorospe, M.; Gallouzi, I.E. Stress granules counteract senescence by sequestration of PAI-1. EMBO Rep. 2018, 19, e44722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, T.; Jiang, C.; Liu, G.; Miyata, T.; Antony, V.; Thannickal, V.J.; Liu, R.M. PAI-1 Regulation of TGF-beta1-induced Alveolar Type II Cell Senescence, SASP Secretion, and SASP-mediated Activation of Alveolar Macrophages. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2020, 62, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, A.G.; Hu, M.; Carlyle, B.C.; Arnold, S.E.; Frosch, M.P.; Das, S.; Hyman, B.T.; Bennett, R.E. Cerebrovascular Senescence Is Associated with Tau Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 575953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochstrasser, T.; Marksteiner, J.; Humpel, C. Telomere length is age-dependent and reduced in monocytes of Alzheimer patients. Exp. Gerontol. 2012, 47, 160–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Forero, D.A.; Gonzalez-Giraldo, Y.; Lopez-Quintero, C.; Castro-Vega, L.J.; Barreto, G.E.; Perry, G. Meta-analysis of Telomere Length in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biomed. Sci. Med. Sci. 2016, 71, 1069–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guo, Y.; Yu, H. Leukocyte Telomere Length Shortening and Alzheimer’s Disease Etiology. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2019, 69, 881–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, F.; Lv, X.; Du, Y.; Chen, H.; Liu, S.; Zhao, J.; Gao, Y.; An, P.; Zhou, X.; Song, A.; et al. Association of Leukocyte Telomere Length with Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease: Role of Folate and Homocysteine. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2019, 48, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheller Madrid, A.; Rasmussen, K.L.; Rode, L.; Frikke-Schmidt, R.; Nordestgaard, B.G.; Bojesen, S.E. Observational and genetic studies of short telomeres and Alzheimer’s disease in 67,000 and 152,000 individuals: A Mendelian randomization study. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 35, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.H.; Han, M.H.; Ha, J.; Park, H.H.; Koh, S.H.; Choi, S.H.; Lee, J.H. Relationship between telomere shortening and age in Korean individuals with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease compared to that in healthy controls. Aging 2020, 13, 2089–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, S.H.; Choi, S.H.; Jeong, J.H.; Jang, J.W.; Park, K.W.; Kim, E.J.; Kim, H.J.; Hong, J.Y.; Yoon, S.J.; Yoon, B.; et al. Telomere shortening reflecting physical aging is associated with cognitive decline and dementia conversion in mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease. Aging 2020, 12, 4407–4423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moverare-Skrtic, S.; Johansson, P.; Mattsson, N.; Hansson, O.; Wallin, A.; Johansson, J.O.; Zetterberg, H.; Blennow, K.; Svensson, J. Leukocyte telomere length (LTL) is reduced in stable mild cognitive impairment but low LTL is not associated with conversion to Alzheimer’s disease: A pilot study. Exp. Gerontol. 2012, 47, 179–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinterberger, M.; Fischer, P.; Huber, K.; Krugluger, W.; Zehetmayer, S. Leukocyte telomere length is linked to vascular risk factors not to Alzheimer’s disease in the VITA study. J. Neural Transm. 2017, 124, 809–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Huo, Y.R.; Wang, J.; Wang, C.; Liu, S.; Liu, S.; Wang, J.; Ji, Y. Telomere Shortening in Alzheimer’s Disease Patients. Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2016, 46, 260–265. [Google Scholar]

- Takata, Y.; Kikukawa, M.; Hanyu, H.; Koyama, S.; Shimizu, S.; Umahara, T.; Sakurai, H.; Iwamoto, T.; Ohyashiki, K.; Ohyashiki, J.H. Association between ApoE phenotypes and telomere erosion in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biomed. Sci. Med. Sci. 2012, 67, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xie, Y.Y.; Pan, T.T.; Xu, D.E.; Huang, X.; Tang, Y.; Huang, W.; Chen, R.; Lu, L.; Chi, H.; Ma, Q.H. Clemastine Ameliorates Myelin Deficits via Preventing Senescence of Oligodendrocytes Precursor Cells in Alzheimer’s Disease Model Mouse. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 733945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Wei, Y.; Lautrup, S.; Yang, B.; Wang, Y.; Cordonnier, S.; Mattson, M.P.; Croteau, D.L.; Bohr, V.A. NAD(+) supplementation reduces neuroinflammation and cell senescence in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease via cGAS-STING. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2011226118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Domenico, F.; Cenini, G.; Sultana, R.; Perluigi, M.; Uberti, D.; Memo, M.; Butterfield, D.A. Glutathionylation of the pro-apoptotic protein p53 in Alzheimer’s disease brain: Implications for AD pathogenesis. Neurochem. Res. 2009, 34, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andorfer, C.; Kress, Y.; Espinoza, M.; de Silva, R.; Tucker, K.L.; Barde, Y.A.; Duff, K.; Davies, P. Hyperphosphorylation and aggregation of tau in mice expressing normal human tau isoforms. J. Neurochem. 2003, 86, 582–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santacruz, K.; Lewis, J.; Spires, T.; Paulson, J.; Kotilinek, L.; Ingelsson, M.; Guimaraes, A.; DeTure, M.; Ramsden, M.; McGowan, E.; et al. Tau suppression in a neurodegenerative mouse model improves memory function. Science 2005, 309, 476–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yoshiyama, Y.; Higuchi, M.; Zhang, B.; Huang, S.M.; Iwata, N.; Saido, T.C.; Maeda, J.; Suhara, T.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Lee, V.M. Synapse loss and microglial activation precede tangles in a P301S tauopathy mouse model. Neuron 2007, 53, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bodea, L.G.; Evans, H.T.; van der Jeugd, A.; Ittner, L.M.; Delerue, F.; Kril, J.; Halliday, G.; Hodges, J.; Kiernan, M.C.; Gotz, J. Accelerated aging exacerbates a pre-existing pathology in a tau transgenic mouse model. Aging Cell 2017, 16, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarabino, D.; Broggio, E.; Gambina, G.; Pelliccia, F.; Corbo, R.M. Common variants of human TERT and TERC genes and susceptibility to sporadic Alzheimers disease. Exp. Gerontol. 2017, 88, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittemore, K.; Derevyanko, A.; Martinez, P.; Serrano, R.; Pumarola, M.; Bosch, F.; Blasco, M.A. Telomerase gene therapy ameliorates the effects of neurodegeneration associated to short telomeres in mice. Aging 2019, 11, 2916–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbig, U.; Jobling, W.A.; Chen, B.P.; Chen, D.J.; Sedivy, J.M. Telomere shortening triggers senescence of human cells through a pathway involving ATM, p53, and p21(CIP1), but not p16(INK4a). Mol. Cell 2004, 14, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, C.C.; Begelman, D.; Nguyen, W.; Andersen, J.K. Senescence as an Amyloid Cascade: The Amyloid Senescence Hypothesis. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, N.; Jin, W.L.; Lok, K.H.; Wang, Y.; Yin, M.; Wang, Z.J. Amyloid-beta(1-42) oligomer accelerates senescence in adult hippocampal neural stem/progenitor cells via formylpeptide receptor 2. Cell Death Dis. 2013, 4, e924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kulkarni, T.; Angom, R.S.; Das, P.; Bhattacharya, S.; Mukhopadhyay, D. Nanomechanical insights: Amyloid beta oligomer-induced senescent brain endothelial cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2019, 1861, 183061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Wu, Z.; Chen, X.; Ma, T. Galantamine alleviates senescence of U87 cells induced by beta-amyloid through decreasing ROS production. Neurosci. Lett. 2017, 653, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh Angom, R.; Wang, Y.; Wang, E.; Pal, K.; Bhattacharya, S.; Watzlawik, J.O.; Rosenberry, T.L.; Das, P.; Mukhopadhyay, D. VEGF receptor-1 modulates amyloid β 1-42 oligomer-induced senescence in brain endothelial cells. FASEB J. 2019, 33, 4626–4637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Lu, J.; Cao, X.; Zhao, H.; Gao, L.; Xia, P.; Pei, G. A Newly Synthesized Rhamnoside Derivative Alleviates Alzheimer’s Amyloid-beta-Induced Oxidative Stress, Mitochondrial Dysfunction, and Cell Senescence through Upregulating SIRT3. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 7698560. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, D.; Hong, Y.; Xie, W.; Tu, Z.; Xu, J. Interleukin-1beta Drives Cellular Senescence of Rat Astrocytes Induced by Oligomerized Amyloid beta Peptide and Oxidative Stress. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendelsohn, A.R.; Larrick, J.W. Cellular Senescence as the Key Intermediate in Tau-Mediated Neurodegeneration. Rejuvenation Res. 2018, 21, 572–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt, T.; Rodel, L.; Gartner, U.; Holzer, M. Expression of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p16 in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroreport 1996, 7, 3047–3049. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Wang, H.; Shenvi, S.; Hagen, T.M.; Liu, R.M. Glutathione metabolism during aging and in Alzheimer disease. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2004, 1019, 346–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aluise, C.D.; Robinson, R.A.; Beckett, T.L.; Murphy, M.P.; Cai, J.; Pierce, W.M.; Markesbery, W.R.; Butterfield, D.A. Preclinical Alzheimer disease: Brain oxidative stress, Abeta peptide and proteomics. Neurobiol. Dis. 2010, 39, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Santos, R.X.; Correia, S.C.; Zhu, X.; Smith, M.A.; Moreira, P.I.; Castellani, R.J.; Nunomura, A.; Perry, G. Mitochondrial DNA oxidative damage and repair in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013, 18, 2444–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Domenico, F.; Pupo, G.; Giraldo, E.; Badia, M.C.; Monllor, P.; Lloret, A.; Schinina, M.E.; Giorgi, A.; Cini, C.; Tramutola, A.; et al. Oxidative signature of cerebrospinal fluid from mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease patients. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2016, 91, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheff, S.W.; Ansari, M.A.; Mufson, E.J. Oxidative stress and hippocampal synaptic protein levels in elderly cognitively intact individuals with Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Neurobiol. Aging 2016, 42, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- M’Kacher, R.; Breton, L.; Colicchio, B.; Puget, H.; Hempel, W.M.; Al Jawhari, M.; Jeandidier, E.; Frey, M. Benefit of an association of an antioxidative substrate and a traditional chinese medicine on telomere elongation. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2019, 65, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zheng, B.; Yang, S.; Zhou, D.; Wang, J. Olmesartan Prevents Oligomerized Amyloid beta (Abeta)-Induced Cellular Senescence in Neuronal Cells. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2021, 12, 1162–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aillaud, M.F.; Pignol, F.; Alessi, M.C.; Harle, J.R.; Escande, M.; Mongin, M.; Juhan-Vague, I. Increase in plasma concentration of plasminogen activator inhibitor, fibrinogen, von Willebrand factor, factor VIII:C and in erythrocyte sedimentation rate with age. Thromb. Haemost. 1986, 55, 330–332. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, K.; Takeshita, K.; Kojima, T.; Takamatsu, J.; Saito, H. Aging and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) regulation: Implication in the pathogenesis of thrombotic disorders in the elderly. Cardiovasc. Res. 2005, 66, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tofler, G.H.; Massaro, J.; Levy, D.; Mittleman, M.; Sutherland, P.; Lipinska, I.; Muller, J.E.; D’Agostino, R.B. Relation of the prothrombotic state to increasing age (from the Framingham Offspring Study). Am. J. Cardiol. 2005, 96, 1280–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, K.; Takeshita, K.; Saito, H. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in aging. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2014, 40, 652–659. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, R.M.; van Groen, T.; Katre, A.; Cao, D.; Kadisha, I.; Ballinger, C.; Wang, L.; Carroll, S.L.; Li, L. Knockout of plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 gene reduces amyloid beta peptide burden in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2011, 32, 1079–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oh, J.; Lee, H.J.; Song, J.H.; Park, S.I.; Kim, H. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 as an early potential diagnostic marker for Alzheimer’s disease. Exp. Gerontol. 2014, 60, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De la Monte, S.M.; Tong, M.; Daiello, L.A.; Ott, B.R. Early-Stage Alzheimer’s Disease Is Associated with Simultaneous Systemic and Central Nervous System Dysregulation of Insulin-Linked Metabolic Pathways. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2019, 68, 657–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelucci, F.; Čechová, K.; Průša, R.; Hort, J. Amyloid beta soluble forms and plasminogen activation system in Alzheimer’s disease: Consequences on extracellular maturation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and therapeutic implications. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2019, 25, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Loures, C.M.G.; Duarte, R.C.F.; Silva, M.V.F.; Cicarini, W.B.; de Souza, L.C.; Caramelli, P.; Borges, K.B.G.; Carvalho, M.D.G. Hemostatic Abnormalities in Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2019, 45, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melchor, J.P.; Pawlak, R.; Strickland, S. The tissue plasminogen activator-plasminogen proteolytic cascade accelerates amyloid-beta (Abeta) degradation and inhibits Abeta-induced neurodegeneration. J. Neurosci. 2003, 23, 8867–8871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cacquevel, M.; Launay, S.; Castel, H.; Benchenane, K.; Cheenne, S.; Buee, L.; Moons, L.; Delacourte, A.; Carmeliet, P.; Vivien, D. Ageing and amyloid-beta peptide deposition contribute to an impaired brain tissue plasminogen activator activity by different mechanisms. Neurobiol. Dis. 2007, 27, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, J.S.; Comery, T.A.; Martone, R.L.; Elokdah, H.; Crandall, D.L.; Oganesian, A.; Aschmies, S.; Kirksey, Y.; Gonzales, C.; Xu, J.; et al. Enhanced clearance of Abeta in brain by sustaining the plasmin proteolysis cascade. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 8754–8759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bi Oh, S.; Suh, N.; Kim, I.; Lee, J.Y. Impacts of aging and amyloid-beta deposition on plasminogen activators and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in the Tg2576 mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res. 2015, 1597, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhter, H.; Huang, W.T.; van Groen, T.; Kuo, H.C.; Miyata, T.; Liu, R.M. A Small Molecule Inhibitor of Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor-1 Reduces Brain Amyloid-beta Load and Improves Memory in an Animal Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018, 64, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struewing, I.T.; Durham, S.N.; Barnett, C.D.; Mao, C.D. Enhanced endothelial cell senescence by lithium-induced matrix metalloproteinase-1 expression. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 17595–17606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vaughan, D.E.; Rai, R.; Khan, S.S.; Eren, M.; Ghosh, A.K. Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor-1 Is a Marker and a Mediator of Senescence. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2017, 37, 1446–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Peng, H.; Yeh, F.; Lin, J.; Best, L.G.; Cole, S.A.; Lee, E.T.; Howard, B.V.; Zhao, J. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 is associated with leukocyte telomere length in American Indians: Findings from the Strong Heart Family Study. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2017, 15, 1078–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.S.; Shah, S.J.; Klyachko, E.; Baldridge, A.S.; Eren, M.; Place, A.T.; Aviv, A.; Puterman, E.; Lloyd-Jones, D.M.; Heiman, M.; et al. A null mutation in SERPINE1 protects against biological aging in humans. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, eaao1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, R.-M. Aging, Cellular Senescence, and Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1989. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23041989

Liu R-M. Aging, Cellular Senescence, and Alzheimer’s Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022; 23(4):1989. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23041989

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Rui-Ming. 2022. "Aging, Cellular Senescence, and Alzheimer’s Disease" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 23, no. 4: 1989. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23041989

APA StyleLiu, R.-M. (2022). Aging, Cellular Senescence, and Alzheimer’s Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(4), 1989. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23041989