Therapeutic Targets for DOX-Induced Cardiomyopathy: Role of Apoptosis vs. Ferroptosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Apoptosis

1.1.1. DNA Damage

1.1.2. Oxidative Stress

1.1.3. Intracellular Signaling

1.1.4. Transcription Factors

1.1.5. Epigenetic Regulators

1.1.6. Autophagy

1.1.7. Metabolic and Inflammation

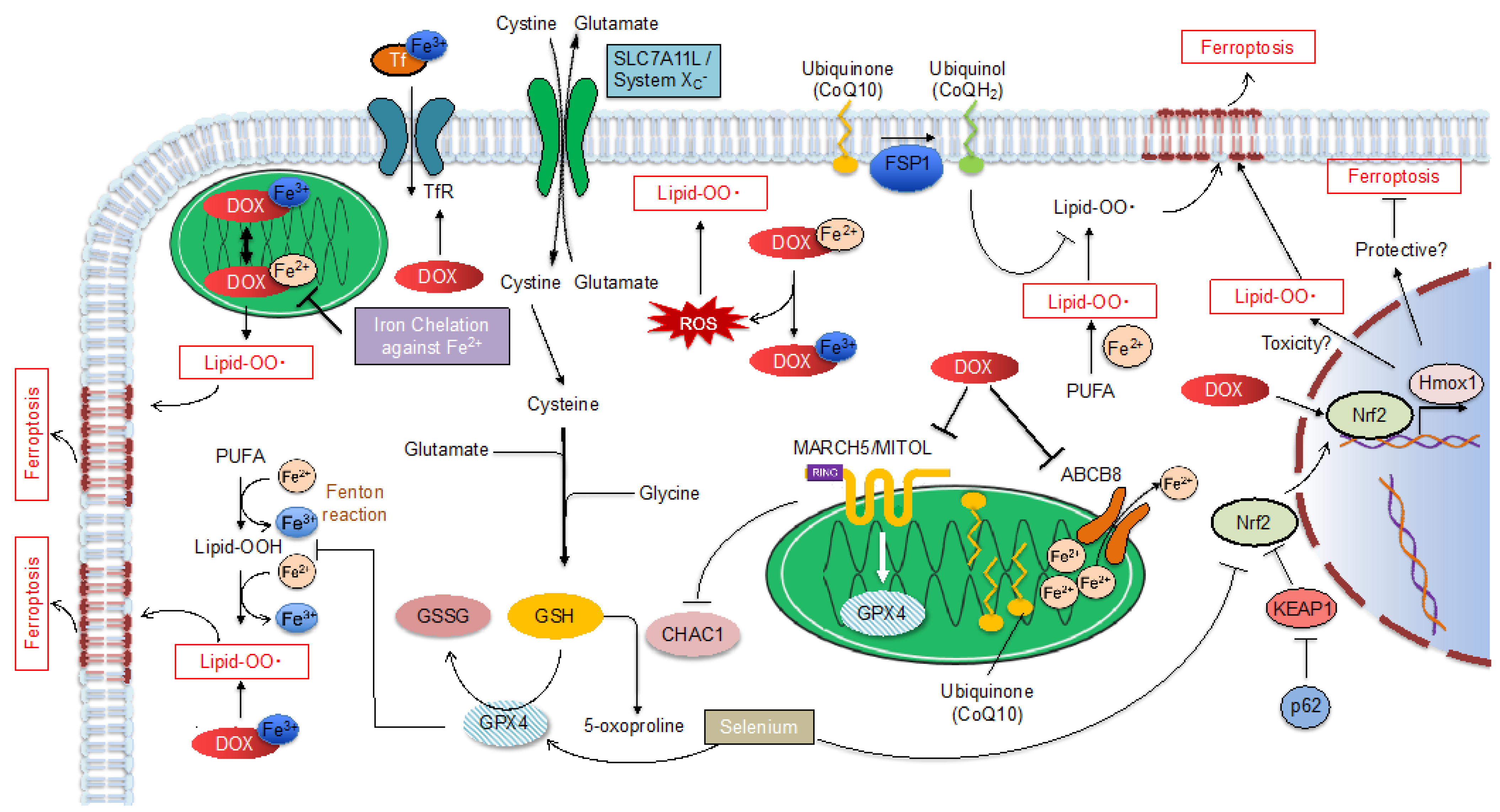

1.2. Ferroptosis

1.2.1. Apoptosis or Ferroptosis?

1.2.2. Ferroptosis Regulatory Pathway

Glutathione Peroxidase 4 (GPX4)

MITOL/MARCH5

Nrf2

Ferroptosis Suppressor Protein 1 (FSP1)

2. Mitochondria Providing a Place for DOX-Induced Cardiotoxicity

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rosen, M.R.; Myerburg, R.J.; Francis, D.P.; Cole, G.D.; Marbán, E. Translating Stem Cell Research to Cardiac Disease Therapies: Pitfalls and Prospects for Improvement. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 64, 922–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ewer, M.S.; Ewer, S.M. Cardiotoxicity of Anticancer Treatments. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2015, 12, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, G.T.; Oeffinger, K.C.; Chen, Y.; Kawashima, T.; Yasui, Y.; Leisenring, W.; Stovall, M.; Chow, E.J.; Sklar, C.A.; Mulrooney, D.A.; et al. Modifiable Risk Factors and Major Cardiac Events among Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 3673–3680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnaik, J.L.; Byers, T.; DiGuiseppi, C.; Dabelea, D.; Denberg, T.D. Cardiovascular Disease Competes with Breast Cancer as the Leading Cause of Death for Older Females Diagnosed with Breast Cancer: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Breast Cancer Res. 2011, 13, R64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Qadir, H.; Austin, P.C.; Lee, D.S.; Amir, E.; Tu, J.V.; Thavendiranathan, P.; Fung, K.; Anderson, G.M. A Population-Based Study of Cardiovascular Mortality Following Early-Stage Breast Cancer. JAMA Cardiol. 2017, 2, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasin, T.; Gerber, Y.; McNallan, S.M.; Weston, S.A.; Kushwaha, S.S.; Nelson, T.J.; Cerhan, J.R.; Roger, V.L. Patients with Heart Failure Have an Increased Risk of Incident Cancer. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 62, 881–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoltzfus, K.C.; Zhang, Y.; Sturgeon, K.; Sinoway, L.I.; Trifiletti, D.M.; Chinchilli, V.M.; Zaorsky, N.G. Fatal Heart Disease among Cancer Patients. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parent, S.; Pituskin, E.; Paterson, D.I. The Cardio-Oncology Program: A Multidisciplinary Approach to the Care of Cancer Patients With Cardiovascular Disease. Can. J. Cardiol. 2016, 32, 847–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ewer, M.S.; Lippman, S.M. Type II Chemotherapy-Related Cardiac Dysfunction: Time to Recognize a New Entity. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 2900–2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yu, X.; Wang, Z.; Wu, P.; Huang, J. Anthracyclines Potentiate Anti-Tumor Immunity: A New Opportunity for Chemoimmunotherapy. Cancer Lett. 2015, 369, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hortobágyi, G.N. Anthracyclines in the Treatment of Cancer. An Overview. Drugs 1997, 54, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawicki, K.T.; Sala, V.; Prever, L.; Hirsch, E.; Ardehali, H.; Ghigo, A. Preventing and Treating Anthracycline Cardiotoxicity: New Insights. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2021, 61, 309–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, K.B.; Sardão, V.A.; Oliveira, P.J. Mitochondrial Determinants of Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiomyopathy. Circ. Res. 2020, 126, 926–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, N.; Wu, F.; Lu, W.J.; Bai, R.; Ke, B.; Liu, T.; Li, L.; Lan, F.; Cui, M. Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity Is Maturation Dependent due to the Shift from Topoisomerase IIα to IIβ in Human Stem Cell Derived Cardiomyocytes. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 4627–4639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyanaraman, B. Teaching the Basics of the Mechanism of Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity: Have We Been Barking up the Wrong Tree? Redox. Biol. 2020, 29, 101394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vejpongsa, P.; Yeh, E.T. Topoisomerase 2β: A Promising Molecular Target for Primary Prevention of Anthracycline-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014, 95, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, X.; Bawa-Khalfe, T.; Lu, L.S.; Lyu, Y.L.; Liu, L.F.; Yeh, E.T. Identification of the Molecular Basis of Doxorubicin-induced Cardiotoxicity. Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 1639–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.; Mohan, N.; Endo, Y.; Shen, Y.; Wu, W.J. Type IIB DNA Topoisomerase Is Downregulated by Trastuzumab and Doxorubicin to Synergize Cardiotoxicity. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 6095–6108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dalen, E.C.; Caron, H.N.; Dickinson, H.O.; Kremer, L.C. Cardioprotective Interventions for Cancer Patients Receiving Anthracyclines. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011, 2011, Cd003917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tebbi, C.K.; London, W.B.; Friedman, D.; Villaluna, D.; De Alarcon, P.A.; Constine, L.S.; Mendenhall, N.P.; Sposto, R.; Chauvenet, A.; Schwartz, C.L. Dexrazoxane-Associated Risk for Acute Myeloid Leukemia/Myelodysplastic Syndrome and Other Secondary Malignancies in Pediatric Hodgkin′s Disease. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabelo, E.; De Angelis, K.; Bock, P.; Gatelli Fernandes, T.; Cervo, F.; Belló Klein, A.; Clausell, N.; Cláudia Irigoyen, M. Baroreflex Sensitivity and Oxidative Stress in Adriamycin-Induced Heart Failure. Hypertension 2001, 38, 576–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Wattanapitayakul, S.K.; Chularojmontri, L.; Herunsalee, A.; Charuchongkolwongse, S.; Niumsakul, S.; Bauer, J.A. Screening of Antioxidants from Medicinal Plants for Cardioprotective Effect against Doxorubicin Toxicity. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2005, 96, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burridge, P.W.; Li, Y.F.; Matsa, E.; Wu, H.; Ong, S.G.; Sharma, A.; Holmström, A.; Chang, A.C.; Coronado, M.J.; Ebert, A.D.; et al. Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes Recapitulate the Predilection of Breast Cancer Patients to Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafa, M.H.; Mohammad, N.S.; Atteia, H.H.; Abd-Elaziz, H.R. Protective Effect of Resveratrol against Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiac Toxicity and Fibrosis in Male Experimental Rats. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2014, 70, 701–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abe, J.; Yamada, Y.; Takeda, A.; Harashima, H. Cardiac Progenitor Cells Activated by Mitochondrial Delivery of Resveratrol Enhance the Survival of a Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiomyopathy Mouse Model via the Mitochondrial Activation of a Damaged Myocardium. J. Control. Release 2018, 269, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Daosukho, C.; Opii, W.O.; Turner, D.M.; Pierce, W.M.; Klein, J.B.; Vore, M.; Butterfield, D.A.; St Clair, D.K. Redox Proteomic Identification of Oxidized Cardiac Proteins in Adriamycin-Treated Mice. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2006, 41, 1470–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaiswing, L.; Cole, M.P.; St Clair, D.K.; Ittarat, W.; Szweda, L.I.; Oberley, T.D. Oxidative Damage Precedes Nitrative Damage in Adriamycin-Induced Cardiac Mitochondrial Injury. Toxicol. Pathol. 2004, 32, 536–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilleron, M.; Marechal, X.; Montaigne, D.; Franczak, J.; Neviere, R.; Lancel, S. NADPH Oxidases Participate to Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiac Myocyte Apoptosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009, 388, 727–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ascensão, A.; Lumini-Oliveira, J.; Machado, N.G.; Ferreira, R.M.; Gonçalves, I.O.; Moreira, A.C.; Marques, F.; Sardão, V.A.; Oliveira, P.J.; Magalhães, J. Acute Exercise Protects against Calcium-Induced Cardiac Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore Opening in Doxorubicin-Treated Rats. Clin. Sci. 2011, 120, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Xiong, Y.; Ho, Y.S.; Liu, X.; Chua, C.C.; Xu, X.; Wang, H.; Hamdy, R.; Chua, B.H. Glutathione Peroxidase 1-Deficient Mice Are More Susceptible to Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2008, 1783, 2020–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C.K.; Wu, J.C. Clinical Trial in a Dish: Using Patient-Derived Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells to Identify Risks of Drug-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2021, 41, 1019–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keshet, Y.; Seger, R. The MAP Kinase Signaling Cascades: A System of Hundreds of Components Regulates a Diverse Array of Physiological Functions. Methods Mol. Biol. 2010, 661, 3–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, E.F.; Nebreda, A.R. Signal Integration by JNK and p38 MAPK Pathways in Cancer Development. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2009, 9, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spallarossa, P.; Altieri, P.; Garibaldi, S.; Ghigliotti, G.; Barisione, C.; Manca, V.; Fabbi, P.; Ballestrero, A.; Brunelli, C.; Barsotti, A. Matrix Metalloproteinase-2 and -9 Are Induced Differently by Doxorubicin in H9c2 Cells: The Role of MAP Kinases and NAD(P)H Oxidase. Cardiovasc. Res. 2006, 69, 736–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thandavarayan, R.A.; Watanabe, K.; Sari, F.R.; Ma, M.; Lakshmanan, A.P.; Giridharan, V.V.; Gurusamy, N.; Nishida, H.; Konishi, T.; Zhang, S.; et al. Modulation of Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiac Dysfunction in Dominant-Negative p38α Mitogen-Activated Protein KINASE mice. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010, 49, 1422–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, R.; Lin, J.; Xu, W.; Shen, N.; Mo, L.; Zhang, C.; Feng, J. Hydrogen Sulfide Attenuates Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity by Inhibition of the p38 MAPK Pathway in H9c2 Cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2013, 31, 644–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, S.A.; Kiss, A.; Obaid, S.N.; Venegas, A.; Talapatra, T.; Wei, C.; Efimova, T.; Efimov, I.R. p38δ Genetic Ablation Protects Female Mice from Anthracycline Cardiotoxicity. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2020, 319, H775–H786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruyama, S.; Shibata, R.; Ohashi, K.; Ohashi, T.; Daida, H.; Walsh, K.; Murohara, T.; Ouchi, N. Adiponectin Ameliorates Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity through Akt Protein-Dependent Mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 32790–32800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, H.C.; Liu, T.J.; Ting, C.T.; Sharma, P.M.; Wang, P.H. Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 Prevents Loss of Electrochemical Gradient in Cardiac Muscle Mitochondria via Activation of PI 3 Kinase/Akt Pathway. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2003, 205, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, P.; Zhao, J.; Sun, L.; Li, M.; Han, Y.; Du, Z.; Li, Y. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Attenuates Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiac Dysfunction through Activating Akt Signalling in Rats. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2017, 21, 685–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.L.; Wei, L.; Zhang, N.; Wei, W.Y.; Hu, C.; Deng, W.; Tang, Q.Z. Levosimendan Protects against Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity by Regulating the PTEN/Akt Pathway. BioMed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 8593617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Ruan, Y.; Shen, T.; Huang, X.; Li, M.; Yu, W.; Zhu, Y.; Man, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, J. Astragalus Polysaccharide Suppresses Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity by Regulating the PI3k/Akt and p38MAPK Pathways. Autoxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2014, 2014, 674219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hu, C.; Kong, C.Y.; Song, P.; Wu, H.M.; Xu, S.C.; Yuan, Y.P.; Deng, W.; Ma, Z.G.; Tang, Q.Z. FNDC5 Alleviates Oxidative Stress and Cardiomyocyte Apoptosis in Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity via Activating AKT. Cell. Death Differ. 2020, 27, 540–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, S.Y.; Tsai, C.Y.; Pai, P.Y.; Chen, Y.W.; Yang, Y.C.; Aneja, R.; Huang, C.Y.; Kuo, W.W. Diallyl Trisulfide Suppresses Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiomyocyte Apoptosis by Inhibiting MAPK/NF-κB Signaling through Attenuation of ROS Generation. Environ. Toxicol. 2018, 33, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.H.; Liu, J.; Lu, J.; Wang, P.X.; Chen, J.X.; Guo, Y.; Han, F.H.; Wang, J.J.; Li, W.; Liu, P.Q. sFRP1 Protects H9c2 Cardiac Myoblasts from Doxorubicin-Induced Apoptosis by Inhibiting the Wnt/PCP-JNK Pathway. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2020, 41, 1150–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boutelle, A.M.; Attardi, L.D. p53 and Tumor Suppression: It Takes a Network. Trends Cell. Biol. 2021, 31, 298–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chua, C.C.; Liu, X.; Gao, J.; Hamdy, R.C.; Chua, B.H. Multiple Actions of Pifithrin-Alpha on Doxorubicin-Induced Apoptosis in Rat Myoblastic H9c2 Cells. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2006, 290, H2606–H2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Feng, Y.; Qu, S.; Wei, X.; Zhu, H.; Luo, Q.; Liu, M.; Chen, G.; Xiao, X. Resveratrol Attenuates Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiomyocyte Apoptosis in Mice through SIRT1-Mediated Deacetylation of p53. Cardiovasc. Res. 2011, 90, 538–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McSweeney, K.M.; Bozza, W.P.; Alterovitz, W.L.; Zhang, B. Transcriptomic Profiling Reveals p53 as a Key Regulator of Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Cell. Death Discov. 2019, 5, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleme, B.; Das, S.K.; Zhang, Y.; Boukouris, A.E.; Lorenzana Carrillo, M.A.; Jovel, J.; Wagg, C.S.; Lopaschuk, G.D.; Michelakis, E.D.; Sutendra, G. p53-Mediated Repression of the PGC1A (PPARG Coactivator 1α) and APLNR (Apelin Receptor) Signaling Pathways Limits Fatty Acid Oxidation Energetics: Implications for Cardio-oncology. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e017247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, D.; Wei, M.; Xu, H.; Peng, T. Rac1 Signalling Mediates Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity through both Reactive Oxygen Species-Dependent and -Independent Pathways. Cardiovasc. Res. 2013, 97, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wang, P.Y.; Long, N.A.; Zhuang, J.; Springer, D.A.; Zou, J.; Lin, Y.; Bleck, C.K.E.; Park, J.H.; Kang, J.G.; et al. p53 Prevents Doxorubicin Cardiotoxicity Independently of Its Prototypical Tumor Suppressor Activities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 19626–19634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shizukuda, Y.; Matoba, S.; Mian, O.Y.; Nguyen, T.; Hwang, P.M. Targeted Disruption of p53 Attenuates Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiac Toxicity in Mice. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2005, 273, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; Zhang, W.; Shou, W.; Field, L.J. P53 Inhibition Exacerbates Late-Stage Anthracycline Cardiotoxicity. Cardiovasc. Res. 2014, 103, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feridooni, T.; Hotchkiss, A.; Remley-Carr, S.; Saga, Y.; Pasumarthi, K.B. Cardiomyocyte Specific Ablation of p53 Is Not Sufficient to Block Doxorubicin Induced Cardiac Fibrosis and Associated Cytoskeletal Changes. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e22801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heineke, J.; Auger-Messier, M.; Xu, J.; Oka, T.; Sargent, M.A.; York, A.; Klevitsky, R.; Vaikunth, S.; Duncan, S.A.; Aronow, B.J.; et al. Cardiomyocyte GATA4 Functions as a Stress-Responsive Regulator of Angiogenesis in the Murine Heart. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 3198–3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Ma, A.G.; Kitta, K.; Fitch, S.N.; Ikeda, T.; Ihara, Y.; Simon, A.R.; Evans, T.; Suzuki, Y.J. Anthracycline-Induced Suppression of GATA-4 Transcription Factor: Implication in the Regulation of Cardiac Myocyte Apoptosis. Mol. Pharmacol. 2003, 63, 368–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, S.; Volden, P.; Timm, D.; Mao, K.; Xu, X.; Liang, Q. Transcription Factor GATA4 Inhibits Doxorubicin-Induced Autophagy and Cardiomyocyte Death. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 793–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.; Zhong, L.; Roush, S.F.; Pentassuglia, L.; Peng, X.; Samaras, S.; Davidson, J.M.; Sawyer, D.B.; Lim, C.C. Disruption of a GATA4/Ankrd1 Signaling Axis in Cardiomyocytes Leads to Sarcomere Disarray: Implications for Anthracycline Cardiomyopathy. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e35743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, H.; Huang, W.H.; Chan, M.W.Y. Review on the Role of Epigenetic Modifications in Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 7, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, L.L.; Cunha-Oliveira, T.; Veloso, C.D.; Costa, C.F.; Wallace, K.B.; Oliveira, P.J. Single Nanomolar Doxorubicin Exposure Triggers Compensatory Mitochondrial Responses in H9c2 Cardiomyoblasts. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 124, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, R.; Yang, Y.; Lei, H.; Wang, G.; Huang, Y.; Xue, W.; Wang, Y.; Yao, L.; Zhu, Y. HDAC6 Inhibition Protects Cardiomyocytes against Doxorubicin-Induced Acute Damage by Improving α-Tubulin Acetylation. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2018, 124, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piotrowska, I.; Isalan, M.; Mielcarek, M. Early Transcriptional Alteration of Histone Deacetylases in a Murine Model of Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiomyopathy. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanf, A.; Oelze, M.; Manea, A.; Li, H.; Münzel, T.; Daiber, A. The Anti-Cancer Drug Doxorubicin Induces Substantial Epigenetic Changes in Cultured Cardiomyocytes. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2019, 313, 108834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dykxhoorn, D.M.; Novina, C.D.; Sharp, P.A. Killing the Messenger: Short RNAs that Silence Gene Expression. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003, 4, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piegari, E.; Russo, R.; Cappetta, D.; Esposito, G.; Urbanek, K.; Dell′Aversana, C.; Altucci, L.; Berrino, L.; Rossi, F.; De Angelis, A. MicroRNA-34a Regulates Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity in Rat. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 62312–62326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.N.; Fu, Y.H.; Hu, Z.Q.; Li, W.Y.; Tang, C.M.; Fei, H.W.; Yang, H.; Lin, Q.X.; Gou, D.M.; Wu, S.L.; et al. Activation of miR-34a-5p/Sirt1/p66shc Pathway Contributes to Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 11879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, J.; Hang, P.; Pan, Y.; Feng, B.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, T.; Zhao, L.; Du, Z. Inhibition of miR-23a Attenuates Doxorubicin-Induced Mitochondria-Dependent Cardiomyocyte Apoptosis by Targeting the PGC-1α/Drp1 Pathway. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2019, 369, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.K.; Garg, A.; Avramopoulos, P.; Engelhardt, S.; Streckfuss-Bömeke, K.; Batkai, S.; Thum, T. miR-212/132 Cluster Modulation Prevents Doxorubicin-Mediated Atrophy and Cardiotoxicity. Mol. Ther. 2019, 27, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berezin, A. Epigenetics in Heart Failure Phenotypes. BBA Clin. 2016, 6, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartlett, J.J.; Trivedi, P.C.; Pulinilkunnil, T. Autophagic Dysregulation in Doxorubicin Cardiomyopathy. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2017, 104, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.H.; Cho, H.; Lee, S.; Woo, J.S.; Cho, B.H.; Kang, J.H.; Jeong, Y.M.; Cheng, X.W.; Kim, W. Enhanced-Autophagy by Exenatide Mitigates Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017, 232, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Zhu, Y.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, B.; Li, G. Glycyrrhizin Improved Autophagy Flux via HMGB1-Dependent Akt/mTOR Signaling Pathway to Prevent Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Toxicology 2020, 441, 152508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, J.; Guo, J.; Zhang, Q.; Cui, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, J.; Li, J.; Middleton, A.; Carmichael, P.L.; et al. Doxorubicin-Induced Mitophagy and Mitochondrial Damage Is Associated with Dysregulation of the PINK1/Parkin Pathway. Toxicol. In Vitro 2018, 51, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Sala, V.; De Santis, M.C.; Cimino, J.; Cappello, P.; Pianca, N.; Di Bona, A.; Margaria, J.P.; Martini, M.; Lazzarini, E.; et al. Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase Gamma Inhibition Protects From Anthracycline Cardiotoxicity and Reduces Tumor Growth. Circulation 2018, 138, 696–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, X.L.; Chen, H.L.; Wu, D.; Chen, J.X.; Wang, X.X.; Li, R.L.; He, J.H.; Mo, L.; Cen, X.; et al. Ghrelin Inhibits Doxorubicin Cardiotoxicity by Inhibiting Excessive Autophagy through AMPK and p38-MAPK. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2014, 88, 334–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Chen, K.; Kobayashi, S.; Timm, D.; Liang, Q. Resveratrol Attenuates Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiomyocyte Death via Inhibition of p70 S6 Kinase 1-Mediated Autophagy. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2012, 341, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chourasia, A.H.; Macleod, K.F. Tumor Suppressor Functions of BNIP3 and Mitophagy. Autophagy 2015, 11, 1937–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhingra, A.; Jayas, R.; Afshar, P.; Guberman, M.; Maddaford, G.; Gerstein, J.; Lieberman, B.; Nepon, H.; Margulets, V.; Dhingra, R.; et al. Ellagic Acid Antagonizes Bnip3-Mediated Mitochondrial Injury and Necrotic Cell Death of Cardiac Myocytes. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2017, 112, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.; Zhong, T.; Ma, Y.; Wan, X.; Qin, A.; Yao, B.; Zou, H.; Song, Y.; Yin, D. Bnip3 Mediates Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiomyocyte Pyroptosis via Caspase-3/GSDME. Life Sci. 2020, 242, 117186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, A.L.C.; Ramasamy, T.S. Role of Sirtuin1-p53 Regulatory Axis in Aging, Cancer and Cellular Reprogramming. Ageing Res. Rev. 2018, 43, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruan, Y.; Dong, C.; Patel, J.; Duan, C.; Wang, X.; Wu, X.; Cao, Y.; Pu, L.; Lu, D.; Shen, T.; et al. SIRT1 Suppresses Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity by Regulating the Oxidative Stress and p38MAPK Pathways. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 35, 1116–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, P.; Cao, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Sun, J.; Fu, L. Resveratrol Prevents Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity in H9c2 Cells through the Inhibition of Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and the Activation of the Sirt1 Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2015, 36, 873–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cappetta, D.; Esposito, G.; Piegari, E.; Russo, R.; Ciuffreda, L.P.; Rivellino, A.; Berrino, L.; Rossi, F.; De Angelis, A.; Urbanek, K. SIRT1 Activation Attenuates Diastolic Dysfunction by Reducing Cardiac Fibrosis in a Model of Anthracycline Cardiomyopathy. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016, 205, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Zhang, X.; Song, P.; Yuan, Y.P.; Kong, C.Y.; Wu, H.M.; Xu, S.C.; Ma, Z.G.; Tang, Q.Z. Meteorin-like Protein Attenuates Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity via Activating cAMP/PKA/SIRT1 Pathway. Redox. Biol. 2020, 37, 101747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.Y.; Cui, Y.K.; Hong, Y.X.; Li, Y.D.; Wu, Y.; Li, G.; Li, G.R.; Wang, Y. Doxorubicin Cardiomyopathy Is Ameliorated by Acacetin via Sirt1-Mediated Activation of AMPK/Nrf2 Signal Molecules. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 12141–12153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Ma, Z.; Xu, L.; Zhang, X.; Qiao, S.; Yuan, J. PGC1α Activation by Pterostilbene Ameliorates Acute Doxorubicin Cardiotoxicity by Reducing Oxidative Stress via Enhancing AMPK and SIRT1 Cascades. Aging 2019, 11, 10061–10073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutta, D.; Xu, J.; Dirain, M.L.; Leeuwenburgh, C. Calorie Restriction Combined with Resveratrol Induces Autophagy and Protects 26-Month-Old Rat Hearts from Doxorubicin-Induced Toxicity. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 74, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.P.; Ma, Z.G.; Zhang, X.; Xu, S.C.; Zeng, X.F.; Yang, Z.; Deng, W.; Tang, Q.Z. CTRP3 Protected against Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiac Dysfunction, Inflammation and Cell Death via Activation of Sirt1. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2018, 114, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, L.; Guo, J.; Zhang, Q.; Yin, J.; Li, J.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, T.; Yuan, H.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, L.; et al. Erythropoietin Activates SIRT1 to Protect Human Cardiomyocytes against Doxorubicin-Induced Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Toxicity. Toxicol. Lett. 2017, 275, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albensi, B.C. What Is Nuclear Factor Kappa B (NF-κB) Doing in and to the Mitochondrion? Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2019, 7, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.S.; Woo, E.R.; Chae, S.W.; Ha, K.C.; Lee, G.H.; Hong, S.T.; Kwon, D.Y.; Kim, M.S.; Jung, Y.K.; Kim, H.M.; et al. Plantainoside D Protects Adriamycin-Induced Apoptosis in H9c2 Cardiac Muscle Cells via the Inhibition of ROS Generation and NF-kappaB Activation. Life Sci. 2007, 80, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Kotamraju, S.; Konorev, E.; Kalivendi, S.; Joseph, J.; Kalyanaraman, B. Activation of Nuclear Factor-kappaB during Doxorubicin-Induced Apoptosis in Endothelial Cells and Myocytes Is Pro-Apoptotic: The Role of Hydrogen Peroxide. Biochem. J. 2002, 367, 729–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Li, J.; An, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, S.Q. Doxorubicin-Induced Apoptosis in H9c2 Cardiomyocytes by NF-κB Dependent PUMA Upregulation. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2013, 17, 2323–2329. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.Q.; Chen, M.T.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Li, W.; Li, Y.G. Docosahexaenoic Acid Attenuates Doxorubicin-Induced Cytotoxicity and Inflammation by Suppressing NF-κB/iNOS/NO Signaling Pathway Activation in H9C2 Cardiac Cells. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2016, 67, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, R.; Wu, K.; Chen, J.; Mo, L.; Hua, X.; Zheng, D.; Chen, P.; Chen, G.; Xu, W.; Feng, J. Exogenous Hydrogen Sulfide Protects against Doxorubicin-Induced Inflammation and Cytotoxicity by Inhibiting p38MAPK/NFκB Pathway in H9c2 Cardiac cells. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2013, 32, 1668–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Tian, X.; Liu, G.; Wang, K.; Xie, Y.; Qiu, Y. Berberine Protects Myocardial Cells against Anoxia-Reoxygenation Injury via p38 MAPK-Mediated NF-κB Signaling Pathways. Exp. Ther. Med. 2019, 17, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhingra, R.; Guberman, M.; Rabinovich-Nikitin, I.; Gerstein, J.; Margulets, V.; Gang, H.; Madden, N.; Thliveris, J.; Kirshenbaum, L.A. Impaired NF-κB Signalling Underlies Cyclophilin D-Mediated Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore Opening in Doxorubicin Cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc. Res. 2020, 116, 1161–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, X.; Wang, H.; Han, D.; Xie, E.; Yang, X.; Wei, J.; Gu, S.; Gao, F.; Zhu, N.; Yin, X.; et al. Ferroptosis as a Target for Protection against Cardiomyopathy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 2672–2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitakata, H.; Endo, J.; Matsushima, H.; Yamamoto, S.; Ikura, H.; Hirai, A.; Koh, S.; Ichihara, G.; Hiraide, T.; Moriyama, H.; et al. MITOL/MARCH5 Determines the Susceptibility of Cardiomyocytes to Doxorubicin-Induced Ferroptosis by Regulating GSH Homeostasis. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2021, 161, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tadokoro, T.; Ikeda, M.; Ide, T.; Deguchi, H.; Ikeda, S.; Okabe, K.; Ishikita, A.; Matsushima, S.; Koumura, T.; Yamada, K.I.; et al. Mitochondria-Dependent Ferroptosis Plays a Pivotal Role in Doxorubicin Cardiotoxicity. JCI Insight 2020, 5, e132747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christidi, E.; Brunham, L.R. Regulated Cell Death Pathways in Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Cell. Death Dis. 2021, 12, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Jiang, W.; Wang, W.; Xiong, R.; Wu, X.; Geng, Q. Ferroptosis and Its Emerging Roles in Cardiovascular Diseases. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 166, 105466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koleini, N.; Nickel, B.E.; Edel, A.L.; Fandrich, R.R.; Ravandi, A.; Kardami, E. Oxidized Phospholipids in Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2019, 303, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancardi, D.; Mezzanotte, M.; Arrigo, E.; Barinotti, A.; Roetto, A. Iron Overload, Oxidative Stress, and Ferroptosis in the Failing Heart and Liver. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, S.J.; Lemberg, K.M.; Lamprecht, M.R.; Skouta, R.; Zaitsev, E.M.; Gleason, C.E.; Patel, D.N.; Bauer, A.J.; Cantley, A.M.; Yang, W.S.; et al. Ferroptosis: An Iron-Dependent form of Nonapoptotic Cell Death. Cell 2012, 149, 1060–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Ou, Z.; Chen, R.; Niu, X.; Chen, D.; Kang, R.; Tang, D. Activation of the p62-Keap1-NRF2 Pathway Protects against Ferroptosis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells. Hepatology 2016, 63, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alim, I.; Caulfield, J.T.; Chen, Y.; Swarup, V.; Geschwind, D.H.; Ivanova, E.; Seravalli, J.; Ai, Y.; Sansing, L.H.; Ste Marie, E.J.; et al. Selenium Drives a Transcriptional Adaptive Program to Block Ferroptosis and Treat Stroke. Cell 2019, 177, 1262–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Tao, J.; Yang, Y.; Tan, S.; Liu, H.; Jiang, J.; Zheng, F.; Wu, B. Ferroptosis Involves in Intestinal Epithelial Cell Death in Ulcerative Colitis. Cell. Death Dis. 2020, 11, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsushita, M.; Freigang, S.; Schneider, C.; Conrad, M.; Bornkamm, G.W.; Kopf, M. T Cell Lipid Peroxidation Induces Ferroptosis and Prevents Immunity to Infection. J. Exp. Med. 2015, 212, 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anbharasi, V.; Cao, N.; Feng, S.S. Doxorubicin Conjugated to D-Alpha-Tocopheryl Polyethylene Glycol Succinate and Folic Acid as a Prodrug for Targeted Chemotherapy. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2010, 94, 730–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, P.J.; Santos, M.S.; Wallace, K.B. Doxorubicin-Induced Thiol-Dependent Alteration of Cardiac Mitochondrial Permeability Transition and Respiration. Biochemistry 2006, 71, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Berthiaume, J.M.; Oliveira, P.J.; Fariss, M.W.; Wallace, K.B. Dietary Vitamin E Decreases Doxorubicin-Induced Oxidative Stress without Preventing Mitochondrial Dysfunction. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2005, 5, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, S.M.; Whaley, F.S.; Gerber, M.C.; Weisberg, S.; York, M.; Spicer, D.; Jones, S.E.; Wadler, S.; Desai, A.; Vogel, C.; et al. Cardioprotection with Dexrazoxane for Doxorubicin-Containing Therapy in Advanced Breast Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 1997, 15, 1318–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasinoff, B.B.; Herman, E.H. Dexrazoxane: How It Works in Cardiac and Tumor Cells. Is it a Prodrug or Is It a Drug? Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2007, 7, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, S.M.; Vici, P. The Current and Future Role of Dexrazoxane as a Cardioprotectant in Anthracycline Treatment: Expert Panel Review. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 130, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotamraju, S.; Chitambar, C.R.; Kalivendi, S.V.; Joseph, J.; Kalyanaraman, B. Transferrin Receptor-Dependent Iron Uptake Is Responsible for Doxorubicin-Mediated Apoptosis in Endothelial Cells: Role of Oxidant-Induced Iron Signaling in Apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 17179–17187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trofenciuc, N.M.; Bordejevic, A.D.; Tomescu, M.C.; Petrescu, L.; Crisan, S.; Geavlete, O.; Mischie, A.; Onel, A.F.M.; Sasu, A.; Pop-Moldovan, A.L. Toll-like Receptor 4 (TLR4) Expression Is Correlated with T2* Iron Deposition in Response to Doxorubicin Treatment: Cardiotoxicity Risk Assessment. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccarinelli, F.; Gammella, E.; Asperti, M.; Regoni, M.; Biasiotto, G.; Turco, E.; Altruda, F.; Lonardi, S.; Cornaghi, L.; Donetti, E.; et al. Mice Lacking Mitochondrial Ferritin Are More Sensitive to Doxorubicin-Mediated Cardiotoxicity. J. Mol. Med. 2014, 92, 859–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ichikawa, Y.; Ghanefar, M.; Bayeva, M.; Wu, R.; Khechaduri, A.; Naga Prasad, S.V.; Mutharasan, R.K.; Naik, T.J.; Ardehali, H. Cardiotoxicity of Doxorubicin Is Mediated through Mitochondrial Iron Accumulation. J. Clin. Investig. 2014, 124, 617–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichikawa, Y.; Bayeva, M.; Ghanefar, M.; Potini, V.; Sun, L.; Mutharasan, R.K.; Wu, R.; Khechaduri, A.; Jairaj Naik, T.; Ardehali, H. Disruption of ATP-Binding Cassette B8 in Mice Leads to Cardiomyopathy through a Decrease in Mitochondrial Iron Export. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 4152–4157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bock, F.J.; Tait, S.W.G. Mitochondria as Multifaceted Regulators of Cell Death. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2020, 21, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Kang, R.; Tang, D. Signaling Pathways and Defense Mechanisms of Ferroptosis. FEBS J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Wang, L.; Qiao, Y.; Yang, B.; Yin, D.; He, M. Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate Pretreatment Alleviates Doxorubicin-Induced Ferroptosis and Cardiotoxicity by Upregulating AMPKα2 and Activating Adaptive Autophagy. Redox. Biol. 2021, 48, 102185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callus, B.A.; Vaux, D.L. Caspase Inhibitors: Viral, Cellular and Chemical. Cell. Death Differ. 2007, 14, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, W.; Wei, S.; Zhang, B.; Li, W. Molecular Mechanisms of Cardiomyocyte Death in Drug-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingold, I.; Berndt, C.; Schmitt, S.; Doll, S.; Poschmann, G.; Buday, K.; Roveri, A.; Peng, X.; Porto Freitas, F.; Seibt, T.; et al. Selenium Utilization by GPX4 Is Required to Prevent Hydroperoxide-Induced Ferroptosis. Cell 2018, 172, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.S.; SriRamaratnam, R.; Welsch, M.E.; Shimada, K.; Skouta, R.; Viswanathan, V.S.; Cheah, J.H.; Clemons, P.A.; Shamji, A.F.; Clish, C.B.; et al. Regulation of Ferroptotic Cancer Cell Death by GPX4. Cell 2014, 156, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, H.E.; El-Swefy, S.E.; Hagar, H.H. The Protective Effect of Glutathione Administration on Adriamycin-Induced Acute Cardiac Toxicity in Rats. Pharmacol. Res. 2000, 42, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todorova, V.K.; Kaufmann, Y.; Hennings, L.J.; Klimberg, V.S. Glutamine Regulation of Doxorubicin Accumulation in Hearts Versus Tumors in Experimental Rats. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2010, 66, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorova, V.K.; Kaufmann, Y.; Hennings, L.; Klimberg, V.S. Oral Glutamine Protects against Acute Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity of Tumor-Bearing Rats. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, D.; Chen, X.; Kang, R.; Kroemer, G. Ferroptosis: Molecular Mechanisms and Health Implications. Cell. Res. 2021, 31, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Samuel, V.P.; Wu, Y.; Dang, M.; Lin, Y.; Sriramaneni, R.; Sah, S.K.; Chinnaboina, G.K.; Zhang, G. Nrf2/HO-1 Mediated Protective Activity of Genistein Against Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiac Toxicity. J. Environ. Pathol. Toxicol. Oncol. 2019, 38, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordgren, K.K.; Wallace, K.B. Keap1 Redox-Dependent Regulation of Doxorubicin-Induced Oxidative Stress Response in Cardiac Myoblasts. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2014, 274, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Wang, W.; Niu, T.; Wang, H.; Li, B.; Shao, L.; Lai, Y.; Li, H.; Janicki, J.S.; Wang, X.L.; et al. Nrf2 Deficiency Exaggerates Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity and Cardiac Dysfunction. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2014, 2014, 748524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, K.; Shen, J.; Yan, J.; Zhai, C.; Zhang, J.; Pan, J.A.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lin, R.Z.; et al. Loss of TRIM21 Alleviates Cardiotoxicity by Suppressing Ferroptosis Induced by the Chemotherapeutic Agent Doxorubicin. EBioMedicine 2021, 69, 103456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.B.; Lu, Z.Y.; Yuan, W.; Li, W.D.; Mao, S. Selenium Attenuates Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity Through Nrf2-NLRP3 Pathway. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Refaie, M.M.M.; Shehata, S.; Ibrahim, R.A.; Bayoumi, A.M.A.; Abdel-Gaber, S.A. Dose-Dependent Cardioprotective Effect of Hemin in Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity Via Nrf-2/HO-1 and TLR-5/NF-κB/TNF-α Signaling Pathways. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2021, 21, 1033–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassannia, B.; Wiernicki, B.; Ingold, I.; Qu, F.; Van Herck, S.; Tyurina, Y.Y.; Bayır, H.; Abhari, B.A.; Angeli, J.P.F.; Choi, S.M.; et al. Nano-Targeted Induction of Dual Ferroptotic Mechanisms Eradicates High-Risk Neuroblastoma. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 3341–3355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doll, S.; Freitas, F.P.; Shah, R.; Aldrovandi, M.; da Silva, M.C.; Ingold, I.; Goya Grocin, A.; Xavier da Silva, T.N.; Panzilius, E.; Scheel, C.H.; et al. FSP1 Is a Glutathione-Independent Ferroptosis Suppressor. Nature 2019, 575, 693–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bersuker, K.; Hendricks, J.M.; Li, Z.; Magtanong, L.; Ford, B.; Tang, P.H.; Roberts, M.A.; Tong, B.; Maimone, T.J.; Zoncu, R.; et al. The CoQ Oxidoreductase FSP1 Acts Parallel to GPX4 to Inhibit Ferroptosis. Nature 2019, 575, 688–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botelho, A.F.M.; Lempek, M.R.; Branco, S.; Nogueira, M.M.; de Almeida, M.E.; Costa, A.G.; Freitas, T.G.; Rocha, M.; Moreira, M.V.L.; Barreto, T.O.; et al. Coenzyme Q10 Cardioprotective Effects Against Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity in Wistar Rat. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2020, 20, 222–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahmanifard, M.; Vessal, M.; Noorafshan, A.; Karbalay-Doust, S.; Naseh, M. The Protective Effects of Coenzyme Q10 and Lisinopril Against Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity in Rats: A Stereological and Electrocardiogram Study. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2021, 21, 936–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, P.S.; Leeuwenburgh, C. Mitochondrial Dysfunction Is an Early Indicator of Doxorubicin-Induced Apoptosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2002, 1588, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childs, A.C.; Phaneuf, S.L.; Dirks, A.J.; Phillips, T.; Leeuwenburgh, C. Doxorubicin Treatment In Vivo Causes Cytochrome C Release and Cardiomyocyte Apoptosis, as Well as Increased Mitochondrial Efficiency, Superoxide Dismutase Activity, and Bcl-2:Bax Ratio. Cancer Res. 2002, 62, 4592–4598. [Google Scholar]

- Tokarska-Schlattner, M.; Wallimann, T.; Schlattner, U. Multiple Interference of Anthracyclines with Mitochondrial Creatine Kinases: Preferential Damage of the Cardiac Isoenzyme and Its Implications for Drug Cardiotoxicity. Mol. Pharmacol. 2002, 61, 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrest, G.L.; Gonzalez, B.; Tseng, W.; Li, X.; Mann, J. Human Carbonyl Reductase Overexpression in the Heart Advances the Development of Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity in Transgenic Mice. Cancer Res. 2000, 60, 5158–5164. [Google Scholar]

- Clementi, M.E.; Giardina, B.; Di Stasio, E.; Mordente, A.; Misiti, F. Doxorubicin-Derived Metabolites induce Release of Cytochrome C and Inhibition of Respiration on Cardiac Isolated Mitochondria. Anticancer Res. 2003, 23, 2445–2450. [Google Scholar]

- Kluza, J.; Marchetti, P.; Gallego, M.A.; Lancel, S.; Fournier, C.; Loyens, A.; Beauvillain, J.C.; Bailly, C. Mitochondrial Proliferation during Apoptosis Induced by Anticancer Agents: Effects of Doxorubicin and Mitoxantrone on Cancer and Cardiac Cells. Oncogene 2004, 23, 7018–7030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavazis, A.N.; Smuder, A.J.; Min, K.; Tümer, N.; Powers, S.K. Short-Term Exercise Training Protects against Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiac Mitochondrial Damage Independent of HSP72. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2010, 299, H1515–H1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugger, H.; Guzman, C.; Zechner, C.; Palmeri, M.; Russell, K.S.; Russell, R.R., III. Uncoupling Protein Downregulation in Doxorubicin-Induced Heart Failure Improves Mitochondrial Coupling but Increases Reactive Oxygen Species Generation. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2011, 67, 1381–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fajardo, G.; Zhao, M.; Berry, G.; Wong, L.J.; Mochly-Rosen, D.; Bernstein, D. β2-Adrenergic Receptors Mediate Cardioprotection through Crosstalk with Mitochondrial Cell Death Pathways. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2011, 51, 781–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, G.C.; Pereira, S.P.; Tavares, L.C.; Carvalho, F.S.; Magalhães-Novais, S.; Barbosa, I.A.; Santos, M.S.; Bjork, J.; Moreno, A.J.; Wallace, K.B.; et al. Cardiac Cytochrome c and Cardiolipin Depletion during Anthracycline-Induced Chronic Depression of Mitochondrial Function. Mitochondrion 2016, 30, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, L.A.; El-Maraghy, S.A. Nicorandil Ameliorates Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Doxorubicin-Induced Heart Failure in Rats: Possible Mechanism of Cardioprotection. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2013, 86, 1301–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narumi, T.; Shishido, T.; Otaki, Y.; Kadowaki, S.; Honda, Y.; Funayama, A.; Honda, S.; Hasegawa, H.; Kinoshita, D.; Yokoyama, M.; et al. High-Mobility Group Box 1-Mediated Heat Shock Protein Beta 1 Expression Attenuates Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Apoptosis. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2015, 82, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, A.C.; Branco, A.F.; Sampaio, S.F.; Cunha-Oliveira, T.; Martins, T.R.; Holy, J.; Oliveira, P.J.; Sardão, V.A. Mitochondrial Apoptosis-Inducing Factor Is Involved in Doxorubicin-Induced Toxicity on H9c2 Cardiomyoblasts. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1842, 2468–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liang, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Ceylan, A.F.; Ren, J.; Zhang, Y. Mitophagy Inhibitor Liensinine Suppresses Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity through Inhibition of Drp1-Mediated Maladaptive Mitochondrial Fission. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 157, 104846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Kim, D.S.; Yadav, R.K.; Kim, H.R.; Chae, H.J. Sulforaphane Prevents Doxorubicin-Induced Oxidative Stress and Cell Death in Rat H9c2 Cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2015, 36, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotamraju, S.; Konorev, E.A.; Joseph, J.; Kalyanaraman, B. Doxorubicin-Induced Apoptosis in Endothelial Cells and Cardiomyocytes Is Ameliorated by Nitrone Spin Traps and Ebselen. Role of Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 33585–33592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, P.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Coates, S.; Liu, D.X.; Cheng, Z. Inhibition of Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 2 Protects against Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiomyocyte Apoptosis and Cardiomyopathy. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 19672–19685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, P.; Chen, J.; Liu, Y.; Fletcher, M.; Jensen, B.C.; Cheng, Z. Doxorubicin Induces Cardiomyocyte Apoptosis and Atrophy through Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 2-Mediated Activation of Forkhead Box O1. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 4265–4276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhingra, R.; Margulets, V.; Chowdhury, S.R.; Thliveris, J.; Jassal, D.; Fernyhough, P.; Dorn, G.W., II; Kirshenbaum, L.A. Bnip3 Mediates Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiac Myocyte Necrosis and Mortality through Changes in Mitochondrial Signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, E5537–E5544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catanzaro, M.P.; Weiner, A.; Kaminaris, A.; Li, C.; Cai, F.; Zhao, F.; Kobayashi, S.; Kobayashi, T.; Huang, Y.; Sesaki, H.; et al. Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiomyocyte Death Is Mediated by Unchecked Mitochondrial Fission and Mitophagy. FASEB J. 2019, 33, 11096–11108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gharanei, M.; Hussain, A.; Janneh, O.; Maddock, H. Attenuation of Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity by Mdivi-1: A Mitochondrial Division/Mitophagy Inhibitor. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e77713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaughlin, D.; Zhao, Y.; O’Neill, K.M.; Edgar, K.S.; Dunne, P.D.; Kearney, A.M.; Grieve, D.J.; McDermott, B.J. Signalling Mechanisms Underlying Doxorubicin and Nox2 NADPH Oxidase-Induced Cardiomyopathy: Involvement of Mitofusin-2. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 174, 3677–3695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aung, L.H.H.; Li, R.; Prabhakar, B.S.; Li, P. Knockdown of Mtfp1 Can Minimize Doxorubicin Cardiotoxicity by Inhibiting Dnm1l-Mediated Mitochondrial Fission. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2017, 21, 3394–3404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type I (Myocardial Damage) | Type II (Myocardial Dysfunction) | |

|---|---|---|

| Representative agents | Anthracyclines (DOX) | Trastuzumab |

| Bevacizumab | ||

| Sunitinib | ||

| Sorafenib | ||

| Dose-dependence | Yes | No |

| Mechanism | Free radical formation | Inhibition of Erb signaling |

| DNA damage | ||

| Oxidative damage | ||

| Clinical manifestation | Underlying damage appears to be permanent and irreversible | High likelihood of recovery (to or near baseline cardiac status) in 2–4 months (reversible) |

| Biopsy presentation | Myofibril disarray | Minimal changes have been reported |

| Vacuole formation | ||

| Effect of rechallenge | High probability of recurrent dysfunction that is progressive, leading to intractable heart failure and death | Increasing evidence for the relative safety of rechallenge; additional data needed |

| Apoptosis (Intrinsic Apoptosis) | Ferroptosis | |

|---|---|---|

| Biochemical characteristics | Involvement of Bcl-2 family proteins Release of cytochrome c from mitochondria Activation of caspases | Peroxidation of cell membrane phospholipids catalyzed by iron ions (Fe2+) Accumulation of lipid hydroxyl radicals |

| Key molecules | Caspase-3, Bcl-2, BAX, p53, NF-κB | GPX4, GSH, Xc−, CHAC1, CoQ10, Nrf2 |

| Inhibitors | ZVAD-FMK, Emricasan, Q-VD-Oph, IDN-6556, DEVD-CHO | Fer-1, Vitamin E, Liproxstatin-1, CoQ10 |

| Morphological features | Chromatin condensation and fragmentation DNA laddering Cell shrinkage and bleb formation at the plasma membrane Exposure of phosphatidylserine to the outer membrane | Decrease in mitochondrial cristae Mitochondrial aggregation |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kitakata, H.; Endo, J.; Ikura, H.; Moriyama, H.; Shirakawa, K.; Katsumata, Y.; Sano, M. Therapeutic Targets for DOX-Induced Cardiomyopathy: Role of Apoptosis vs. Ferroptosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1414. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23031414

Kitakata H, Endo J, Ikura H, Moriyama H, Shirakawa K, Katsumata Y, Sano M. Therapeutic Targets for DOX-Induced Cardiomyopathy: Role of Apoptosis vs. Ferroptosis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022; 23(3):1414. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23031414

Chicago/Turabian StyleKitakata, Hiroki, Jin Endo, Hidehiko Ikura, Hidenori Moriyama, Kohsuke Shirakawa, Yoshinori Katsumata, and Motoaki Sano. 2022. "Therapeutic Targets for DOX-Induced Cardiomyopathy: Role of Apoptosis vs. Ferroptosis" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 23, no. 3: 1414. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23031414

APA StyleKitakata, H., Endo, J., Ikura, H., Moriyama, H., Shirakawa, K., Katsumata, Y., & Sano, M. (2022). Therapeutic Targets for DOX-Induced Cardiomyopathy: Role of Apoptosis vs. Ferroptosis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(3), 1414. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23031414