Abstract

Beneficial metabolic effects of inorganic nitrate (NO3−) and nitrite (NO2−) in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) have been documented in animal experiments; however, this is not the case for humans. Although it has remained an open question, the redox environment affecting the conversion of NO3− to NO2− and then to NO is suggested as a potential reason for this lost-in-translation. Ascorbic acid (AA) has a critical role in the gastric conversion of NO2− to NO following ingestion of NO3−. In contrast to AA-synthesizing species like rats, the lack of ability to synthesize AA and a lower AA body pool and plasma concentrations may partly explain why humans with T2DM do not benefit from NO3−/NO2− supplementation. Rats also have higher AA concentrations in their stomach tissue and gastric juice that can significantly potentiate gastric NO2−-to-NO conversion. Here, we hypothesized that the lack of beneficial metabolic effects of inorganic NO3− in patients with T2DM may be at least in part attributed to species differences in AA metabolism and also abnormal metabolism of AA in patients with T2DM. If this hypothesis is proved to be correct, then patients with T2DM may need supplementation of AA to attain the beneficial metabolic effects of inorganic NO3− therapy.

1. Introduction

Inorganic nitrate (NO3−) and nitrite (NO2−) are considered storage pools for nitric oxide (NO)-like bioactivity that complement or alternate the NO synthase (NOS)-dependent pathway [1]. The biological importance of the NO3−-NO2−-NO pathway is more highlighted where the NOS system is compromised, e.g., in cardiometabolic diseases [2,3].

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), a metabolic disorder complicated with disrupted NO metabolism [4,5], has recently been targeted for inorganic NO3−-NO2− therapy. Supplementation of diets rich in inorganic NO3−-NO2− has received increased attention as being effective in improving glucose and insulin homeostasis in animal models of T2DM [6,7,8,9,10]. Favorable effects of NO3− therapy on glucose and insulin homeostasis were surprisingly comparable to metformin therapy, a drug that is used as the first-line anti-diabetic agent [11].

In contrast to animal experiments, controversy surrounds the NO3−-NO2− efficacy on metabolic parameters in humans with T2DM. These interventions have failed to show any beneficial effects on glucose and insulin parameters. Although some plausible explanations have been provided, the reason for this lost-in-translation remains an open question. Species-differences in NO3−-NO2− metabolism, due to differences in gut–oral microbiota, and the redox environment affecting the capacity of NO3− to NO2− to NO reduction (e.g., oral and stomach pH, reducing agents like ascorbic acid (AA), and NO3−-NO2− reductase enzymes) may explain the failure of the data to translate from animals to humans. Furthermore, some confounding variables such as doses and forms of NO3− and NO2− supplementation, age of the experimental units [12], background dietary intake of NO3−-NO2−, and use of anti-diabetic drugs in humans [11,13] can also influence the magnitude of the metabolic response to NO3−-NO2− therapy in humans with T2DM.

In this review, we discuss whether the differences between laboratory animals (i.e., rats and mice) and humans in the metabolism of AA, as an essential reducing factor for gastric conversion of NO2− to NO, are responsible for the lost-in-translation and reduced efficacy of oral NO3− in humans with T2DM. Because more than 80% of the studies investigating the potential effects of NO3−-NO2− on animal models of T2DM were conducted on rats, we specifically focused on the differences between humans and rats in metabolizing AA; however, we also considered the available data on mice. If our hypothesis is correct, patients with T2DM may need to be supported by AA supplementation to take advantage of inorganic NO3− therapy.

2. A Brief Overview of NO3−-NO2−-NO Pathway

There are two major pathways for NO production in humans: (i) the classic l-arginine-NOS pathway, in which NO is produced from l-arginine by three isoforms of NOS, namely, endothelial (eNOS), neural (nNOS), and inducible (iNOS) NOSs, and (ii) NO3−-NO2−-NO pathway, in which NO3− is reduced to NO2− and then to NO [2]. The NO3−-NO2−-NO pathway has a compensatory role in maintaining basal levels of NO in the absolute absence of the NOS system (i.e., triple NOS-knockout model), thus keeping the animals alive [14]. There is negative cross-talk between the two pathways in maintaining NO homeostasis [1,15]. Chronic NO3− supplementation may reversibly and dose-dependently reduce eNOS activity; on the other hand, responses to exogenous NO3−-NO2− depend upon the basal eNOS activity, and subjects with deficient eNOS activity and vascular NO deficiency may, therefore, have an augmented response to these anions [1,15]. Several dietary factors, including dietary antioxidants, polyphenols, and fatty acids, may affect the NO pathway in humans [16]. Furthermore, dietary antioxidant capacity and vitamin C intake may modify the potential effects of NO3−-NO2− in cardiometabolic diseases [17,18].

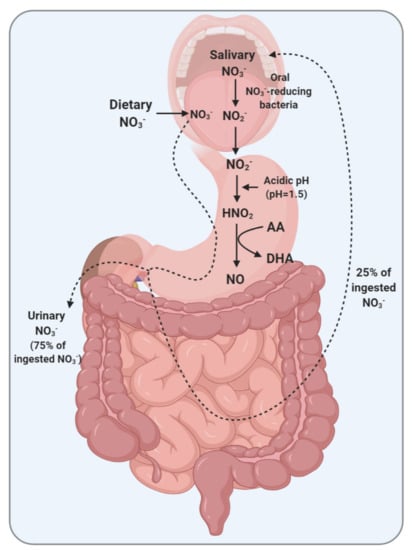

Major sources of NO3− in humans are endogenously derived from NO oxidation and exogenously derived from the diet. About 50% of steady-state circulating NO metabolites are derived from dietary sources [19]; the acceptable daily intake (ADI) values are 3.7 and 0.06 mg/kg body weight for NO3− and NO2−, respectively [20]. Following ingestion, inorganic NO3− passes from the mouth into the stomach and is then absorbed into the blood from the proximal small intestine [21]. In humans, about 50–90% [22,23,24] (a mean of 75% [25]) of ingested NO3− is excreted in the urine, with negligible fecal excretion [26]. NO3− recovery from urine was reported to be about 35–65% of the oral doses in rats and rabbits [21,27]. About 25% of ingested NO3− is taken up from the plasma [28] by the salivary glands, probably via the sialin transporter [29], concentrated by 10–20 folds, and secreted in the saliva [29,30], a process that is called enterosalivary circulation of NO3− [28]. Unlike humans, the active secretion of NO3− into the saliva does not occur in rats and mice [31]; however, the entero-systemic cycling of NO3− may occur in these species by secreting from the circulation into the other parts of the gastrointestinal system, including the gastric and intestinal secretions via an active transport process [32].

Upon entering the mouth, oral NO3−-reducing bacteria converts about 20% of the dietary NO3− to NO2− [28]. This pathway is the most important source of NO2− in the human body [33] and provides systemic delivery of substrate for NO generation. Oral NO3−-reduction results in an average of 85.4 ± 15.9 nmol NO2− per min [34]. The oral NO3−-reducing bacteria are mostly resident at the dorsal surface of the tongue both in humans and rats [34,35]. The critical role of NO3−-reducing bacteria on the NO3−-NO2−-NO pathway and systemic NO availability is highlighted by the data showing that circulating NO2− is decreased and NO-mediated biological effects are partially or entirely prevented when the oral microbiome was abolished via antiseptic mouthwash [36,37,38]. Although the rat tongue microbiome is less diverse than the human, the physiological activity of the oral microbiome is comparable in both species [39].

Salivary NO2− reaching the stomach is rapidly converted to NO in the presence of acidic gastric juice and AA and diffuses into the circulation [40,41]. Inorganic NO3− can therefore act as a substrate for further systemic generation of bioactive NO [30]. The efficiency of sequential reduction of inorganic NO3− into NO2− and then into NO depends on the capacity of the salivary glands to concentrate NO3−, oral NO3−-reducing bacteria, gastric AA concentration and the redox environment, O2 pressure, pH in the peripheral circulation, and the efficiency of the enzymatic reductase activity (i.e., deoxyhemoglobin, aldehyde dehydrogenase, and xanthine oxidase) [1]; these factors may affect the metabolic response to oral dosing of inorganic NO3−.

3. Effects of Inorganic NO3− and NO2− in Type 2 Diabetes

Impaired NO metabolism, including decreased eNOS-derived NO bioavailability, over-production of iNOS-derived NO, and impaired NO3−-NO2−-NO pathway, are involved in T2DM development [42], hypertension [43], and cardiovascular diseases [44]. Increased NO bioavailability using NO precursors, including L-arginine [45,46], L-citrulline [47], or inorganic NO3− and NO2− has been suggested as complementary treatments in T2DM [48,49,50]. Due to lack of efficacy [51] and safety [52] of long-term L-arginine supplementation and undesirable side effects (i.e., induction of arginase activity [53,54], increased urea levels [55], suppression of eNOS expression and activity, and induction of cellar oxidative stress [56]), inorganic NO3− and NO2− have received much attention as NO-boosting supplements.

Inorganic NO3− and NO2− improve glucose and insulin homeostasis in animal models of T2DM [6,7,8,9,10]; supplementation with these anions decreases hyperglycemia and improves insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance [9,10]. NO3− and NO2− increase insulin secretion by increasing pancreatic blood flow [57], increasing pancreatic islet insulin content [7], and increased gene expression of proteins involved in exocytosis of insulin in isolated pancreatic islets [58]. NO3− and NO2− increase insulin sensitivity by increasing GLUT4 expression and protein levels in epididymal adipose tissue [6], skeletal muscle [7], and its translocation into the cell membrane [9], increasing browning of white adipose tissue [59], decreasing adipocyte size [9], as well as improving inflammation, dyslipidemia, liver steatosis, and oxidative stress [3,7,60]. Table 1 summarizes the effects of NO3−-NO2− therapy on glucose and insulin homeostasis, and diabetes-induced cardiometabolic disorders in animal models of T2DM. More details about the favorable metabolic effects of NO3− and NO2− can be found in published reviews [2,3,61].

Table 1.

The effects of NO3− and NO2− on glucose and insulin homeostasis, and cardiometabolic disorders in experimental models of type 2 diabetes mellitus and insulin resistance.

Despite being effective in animal models of T2DM, as it is summarized in Table 2, all acute [67], mid-term [68,69], and long-term [70,71,72] oral dosing of inorganic NO3− and NO2−, either as pharmacological forms (i.e., KNO3, NaNO3, and NaNO2) or food-based supplementation (i.e., NO3−-rich beetroot juice or powder) have failed to show beneficial effects on glucose and insulin parameters, including fasting and post-prandial serum glucose and insulin concentrations, insulin resistance indices, and HbA1c levels in patients with T2DM. However, ergogenic [73,74] and beneficial cardiovascular effects of inorganic NO3− and NO2−, e.g., reducing peripheral and central systolic and diastolic blood pressures [75], have been highlighted in non-diabetic subjects by several clinical studies.

Table 2.

Cardiometabolic effects of inorganic NO3−-NO2− in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: findings of clinical trials.

4. A Brief Overview of AA Metabolism: Differences between Animals and Humans

Ascorbic acid (ascorbate) is a potent antioxidant and free-radical scavenger because of its ability for non-enzymatic reduction of oxygen free radicals [80]. Total vitamin C represents a reduced form (AA) and an oxidized form (dehydroascorbic acid, DHA), which circulates at a physiological plasma concentration of <5% of total vitamin C (i.e., AA + DHA). In humans, the mean plasma concentrations of AA range from 60 to 90 µmol/L [81], with levels above 50 µmol/L defined as adequate [82]. Although the upper limit (UL) of the vitamin C intake, based on its gastrointestinal complications such as osmotic diarrhea, has been determined as 2 g/day, some studies have reported no gastrointestinal disturbances following doses of up to 6 g/day [83,84]. Long-term treatment with AA has been reported to be safe with minimal side effects [85].

A meta-analysis of 13 clinical trials in patients with T2DM showed that vitamin C supplementation significantly decreases blood glucose (−0.44 mmol/L) and insulin concentrations (−15.67 pmol/L); however, it had no effect on HbA1C levels (−0.15%) [86]. Another meta-analysis also reported a statistically and clinically significant decrease in systolic blood pressure (−6.27 mm Hg, 95% CI = −9.60, −2.96), and a moderate decrease in HbA1c (−0.54%, 95% CI = −0.90, −0.17) and diastolic blood pressure (−3.77 mm Hg, 95% CI s= −6.13, −1.42) following vitamin C supplementation in patients with T2DM [87].

Both plasma and tissue concentrations of AA are tightly controlled [81]. Ascorbic acid in plasma is taken up by the tissues via sodium-dependent vitamin C transporters (SVCT1 and SVCT2) in both rats and humans [88,89]. These transporters reach a Vmax at a plasma concentration of about 70 µmol/L, achieved by a daily intake of 200 mg of AA [90]. The DHA is transported via glucose transporters (i.e., GLUT1 [91], GLUT2 [92], GLUT3 [93], and GLUT8 [92]), involved in the AA recycling process, in which the DHA that is produced from extracellular oxidation is transported to cells where it undergoes immediate intracellular reduction to AA [94]. This process is suggested to be responsible for vitamin C economy in the body [95].

Humans and guinea pigs lack the enzyme L-gulono-γ-lactone oxidase (GLO) and thus cannot synthesize AA [96]. However, other mammals including rats, rabbits, and mice can synthesize AA endogenously [97]. Plasma AA concentrations have been reported to be 60–90 µmol/L in mice [98,99] and 680 µmol/L in rats [100]. Table 3 summarizes the differences between AA metabolism in humans and AA synthesizing species including rats and mice. Taken together, the lack of ability to synthesize AA, lower AA body pool, and lower plasma concentrations may make humans more susceptible to AA-deficiency [101].

Table 3.

Kinetic parameters of ascorbic acid (AA) metabolism between AA synthesizing and non-synthesizing species.

5. Gastric NO Generation: Critical Role of AA

5.1. Gastric Generation of NO

NO has been shown to accumulate in the gastric headspace after NO3− ingestion [111], maximally at the proximal cardia region (gastroesophageal junction and cardia) of the stomach, where salivary NO2− initially encounters gastric acid [112,113]. In healthy humans, baseline gastric NO2− levels are very low (overall < 1 µmol/L [40], 7.6 ± 2.7 μmol/L in the cardia, 0.4 ± 0.3 μmol/L in the proximal cardia, and 0 μmol/L in the distal stomach [114]). In the gastric head-space, the NO concentration is about 16.4 ± 5.8 ppm [40], which we calculated it to be 546.7 ± 193.3 µmol/L. Since the generated NO rapidly diffuses into the adjacent epithelium, only a small fraction of the NO2− and NO remain at the distal stomach section [114].

Gastric NO concentration is increased from 14.8 ± 3.1 to 89.4 ± 28.6 ppm following 60 min of 2 mmol KNO3 oral dosing [40]. Upon an oral dose of inorganic NO3−, peak gastric NO3− occurs at ~20 min, its plasma values peaks at 40 min, and gastric head-space NO concentration peaks at 60 min [40]. Following ingestion of 2 mmol inorganic NO3−, mean gastric NO concentration (measured in the distal stomach to the mid esophagus) reaches 14.7 µmol/L (range = 0.8–50 µmol/L) that is 3-fold higher than its basal levels (4.7 µmol/L, range = 1.4–7.8 µmol/L) [112].

5.2. Gastric Secretion of AA

The stomach can secret AA; however, the mechanism and the transporters involved have not yet been identified [95]. Upon its absorption, vitamin C is actively secreted into and concentrated within the gastric juice (mainly in the form of AA) of the healthy acid-secreting stomach [115]. Ascorbic acid is transported into the gastric epithelial cells (Kato III cells and gastric adenocarcinoma (AGS) cell lines) and then accumulated against a concentration gradient, up to greater than 1.6- [116] to 7-folds [117] higher than its plasma levels [118,119,120]. The clearance rate of AA from the plasma to the gastric juice in healthy humans is about 1.25 mL/min (range: 0.47–3.14 mL/min) [107], and about 60 mg of vitamin C is expected to be released into the stomach daily [118,121]. The mean fasting concentrations of gastric vitamin C (AA + DHA) and AA concentrations range between 30–100 and 20–80 µmol/L in healthy humans, respectively [116,119,121,122,123]. In humans, gastric AA secretion is stimulated following ingestion of inorganic NO3−. After ingesting 20 mmol of NO3−, salivary NO2− levels increased by about 6-fold, from 44 to 262 µmol/L, gastric juice AA reached its nadir of 5.1 μmol/L within 60 min (with a ratio of 0.2 of AA to total vitamin C), and then, gradually returned toward its original levels within the next 60 min [122].

In rats, gastric secretion of AA has been suggested to be physiologically regulated by both muscarinic receptor-associated cholinergic stimulation and by cholecystokinin octapeptide (CCK-8) receptor-associated hormonal stimulation [124,125].

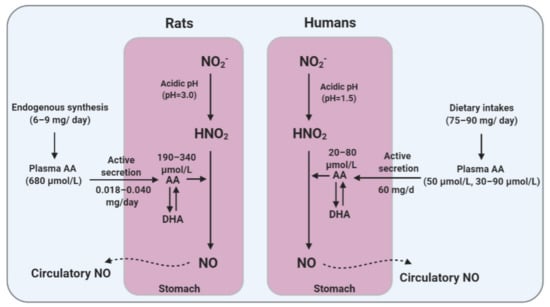

Compared to humans, higher levels of AA in gastric juice were reported in rats (244 ± 64 µmol/L; range: 190–340 µmol/L) [125]. Higher concentrations of AA have also been reported in the rat stomach tissue (1260 and 658 µmol/L in the glandular stomach and the forestomach, respectively) [126]. In contrast to constant [98] or decreased [100] plasma levels of AA during aging, its concentrations in the gastrointestinal tissues tend to increase with age (e.g., 313 ± 172 vs. 155 ± 34 µg/g in the stomach, young vs. old rats) [100].

Taken together, having endogenous synthesis and higher plasma concentrations of AA provide a constant supply of gastric AA, high-accumulated levels of AA in the rat’s stomach, especially in the glandular region. Thus, a higher level of AA in the gastric juice in AA-synthesizing species like rats provides a more efficient environment for gastric NO generation.

5.3. Role of AA in Gastric NO Generation

Ascorbic acid has a critical contribution to gastric NO production and maintaining systemic NO levels (Figure 1). Under the acidic conditions of the stomach, the NO2− delivered along with the saliva is rapidly (pKa = 3.2–3.4) converted to nitrous acid (HNO2) and then into NO in the presence of AA. In this reaction, AA is oxidized to DHA. Each molecule of AA can reduce two molecules of HNO2 to NO [127]. The presence of AA within the gastric juice seems to be a critical factor in providing a continuous supply of systemic NO, which is supported by enterosalivary recirculation of NO3−-NO2− [122,128]. Ascorbic acid-dependent reduction of NO2− to NO needs an acidic gastric environment [41]. At pH 4.5 or above, very little NO is produced, as is the case in the absence of AA, even at low pH values [41].

Figure 1.

Enterosalivary circulation of nitrate (NO3−) and the role of ascorbic acid (AA) in the gastric conversion of nitrite (NO2−) to nitric oxide (NO) in maintaining systemic NO levels. DHA, dehydroascorbic acid; HNO2, nitrous acid.

To produce 50 µmol/L of gastric NO, in the presence of 200 µmol/L of NO2− at a pH of 1.5, about 500 µmol/L of AA is needed [113]. The median AA-to-NO2− ratio, a critical determinant of gastric NO production, is reported to be about 1.5, 21, and 28 at the cardia, mid and distal stomach, reaching 0.3, 8, and 40 following NO3− ingestion [114]. In rats, gastric NO2− to NO conversion with 0.1 mmol/L NaNO2 at a pH of 1.5 was dose-dependently increased by AA. Exogenously increasing the concentration of gastric AA by 2- and 4-fold (from 5 to 10 and 20 mmol/L) efficiently increased gastric NO generation by about 1.7- and 3.5-fold [129].

The importance of AA for gastric NO generation is highlighted by the data that quantifies gastric NO concentrations in a situation of diminished AA within the gastric juice. Treatment of healthy volunteers with omeprazole (a proton-pump inhibitor) at a dose of 40 mg/day, reduced fasting gastric AA levels by more than 80% (from 21.6 to 4.0 μmol/L) [122], which may be explained by impaired gastric secretion of AA by the mucosa or its destruction in the high-pH gastric juice [128]. In the presence of normal levels of gastric juice and AA, gastric NO2− levels remained undetectable for 120 min after an oral dose of NO3− [122], which indicates that salivary NO2− reaching the stomach was entirely converted to NO. In contrast, increased both fasting (from 0 to 13 μmol/L) and post-NO3−-ingestion (Δ = 150 μmol/L) gastric juice NO2− levels during omeprazole treatment [122] may imply on the blunted-NO synthesis following profound decreased AA within the gastric juice. This idea is supported by data showing that NO in expelled air from the stomach was reduced by 95% after treatment with omeprazole [111].

A considerably higher concentration of AA reported in the rat’s stomach [126] compared to that in humans [122] may greatly potentiate the capacity of gastric NO production in response to NO3−-NO2− dosing. Thus, it seems that AA non-synthesizing species such as humans and guinea pigs do not adequately recapitulate the effects of NO3−-NO2− supplementation observed in AA-synthesizing species. Figure 2 addresses how differences in AA metabolism and gastric AA secretion between humans and rats may affect the conversion of gastric NO2− to NO.

Figure 2.

Differences between humans and rats in ascorbic acid (AA) metabolism and gastric AA secretion that may affect the efficacy of gastric conversion of nitrite (NO2−) to nitric oxide (NO). DHA, dehydroascorbic acid.

6. Diabetes and AA Metabolism

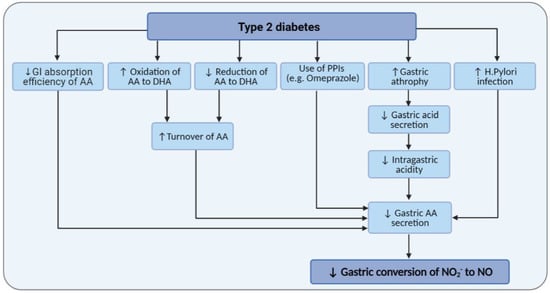

Abnormal metabolism of AA and its deficiency is a relatively common situation amongst patients with T2DM [130,131,132]. The prevalence of deficient, marginal, and inadequate plasma vitamin C concentrations was reported to be 4%, 14%, and 52% in patients with T2DM, compared to 3% marginal and 21% inadequate plasma vitamin C concentrations in non-diabetic subjects [131]. Chronic hyperglycemia is associated with intracellular AA deficiency, and a negative correlation is observed between glycemic control and duration of T2DM and circulatory AA [133,134]. The turnover of AA is reported to be higher in patients with diabetes compared to healthy subjects, which is probably due to increased oxidation of AA to DHA by the mitochondria, and decreased rate of reduction of DHA to AA in the tissues and erythrocytes [135].

Patients with diabetes have lower circulating levels of vitamin C compared to healthy subjects (e.g., 8.4 vs. 33.4 µmol/L [134], 41.2 vs. 57.4 µmol/L [131], 19 vs. 40 µmol/L [132], 42.1 vs. 89.2 µmol/L [136]). A more prevalence of vitamin C deficiency (i.e., <11.0 µmol/L) has also been reported in diabetics [131,132]. An elevated circulatory DHA (e.g., 11.9 vs. 3.9 µmol/L [134], 31.3 vs. 28.1 µmol/L [136], 10.3 vs. 1.7 µmol/L [135]) and increased plasma DHA-to-AA ratio (0.87 vs. 0.38) have also been observed in patients with diabetes strongly suggesting disturbances in AA metabolism [136].

Of note, gastric disorders such as decreased gastric acid secretion, gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD), and H. pylori infection are more prevalent in diabetic patients [137,138,139]. Therefore, as often is the case, treatment with proton pump inhibitors in these patients may result in decreased gastric AA that is required for converting NO2− to NO. The mean concentration of gastric AA decreased by 40% in H. pylori infection [120]. Decreased intragastric acidity in diabetes [140] may also affect gastric AA levels; increased gastric pH from <2 to 4 and >6 reduced gastric juice AA concentrations from 16.5 to 4.5 and 0 μmol/L and decreased gastric-to-plasma AA ratio by 25% and 80% [120]. Subjects with chronic superficial and atrophic gastritis have reduced gastric AA levels, 21 and 6 µmol/L vs. 253 µmol/L in healthy adults [117]. Gastric AA secretion is significantly related to gastric atrophy, and patients with chronic gastritis and hypochlorhydria have significantly lower (reduced by 50%) gastric concentrations of AA [115,121,141]. Infected patients with H pylori also have lower gastric concentrations of AA (19.3 μmol/L, IQR = 10.7–44.5 vs. 66.9 μmol/L, IQR = 24.4–94.2) [123]. In patients with gastritis, the AA within gastric juice is mainly in its oxidized, biologically inactive form [121]. The decreased ratio of gastric-to-plasma concentrations of AA in gastritis may indicate an impaired secretion of AA in the gastric juice [121]. Figure 3 shows how T2DM and its related gastric abnormalities may confound the mediatory role of gastric AA on the conversion of NO2− to NO.

Figure 3.

Effects of type 2 diabetes and its related gastric abnormalities on gastric ascorbic acid (AA) levels and gastric conversion of nitrite (NO2−) to nitric oxide (NO). DHA, dehydroascorbic acid; GI, gastrointestinal; PPI, proton pump inhibitors.

Considering an impaired AA metabolism in T2DM, it seems quite reasonable to speculate that at some level, the lack of response to supplementation with inorganic NO3−-NO2− in these patients may be related to a blunted NO2−-AA interaction and gastric NO production. In addition, considering the critical role of AA in NO3−-derived gastric NO formation, failure in translation of the beneficial effects of inorganic NO3−-NO2− into humans may partly be explained by the species-dependent AA-synthesizing capacity and different levels of AA availability in animals (rat and mice) versus humans. In rats, a large amount of endogenously synthesized AA is available and bioconversion of NO2− to NO is expected to be more efficient. Our speculation is supported by data indicating that co-supplementation of inorganic NO3− with vitamin C is clinically more effective in enhancing vascular function and decreasing diastolic blood pressure, especially in older adults, which, compared to young adults, are expected to have less gastric AA concentrations [142]. Moreover, less excreted NO3− and NO2− in the urine following NO3− intake, in the presence of higher vitamin C intake [143], may imply that a higher level of vitamin C is required in humans for effective NO synthesis from oral inorganic NO3− [143].

7. Conclusions and Perspectives

Taken together, although inorganic NO3−-NO2− ingestion displays profound NO-dependent improvements in vascular function and blood pressure in humans, the concentration of gastric AA and intragastric NO2−-NO conversion rate in humans may not to be sufficient to elicit NO-dependent anti-diabetic effects as that observed in animals like rats. As non-AA-synthesizing species, humans may be more susceptible to AA-deficiency, a situation that is relatively common among patients with T2DM. Co-supplementation of inorganic NO3−-NO2− with vitamin C can therefore be considered as a suggestion to enhance efficacy of NO3− supplementation in humans. However, limited evidence is available to confirm the idea directly, and clinical studies are therefore warranted to assess the efficacy and potential side effects of co-supplementation of inorganic NO3−-NO2− with vitamin C in humans.

Since saturation of gastric epithelial AA transport occurs at 50 µmol/L, oral vitamin C supplements may only be effective in subjects with plasma concentrations less than 50 µmol/L [118]. On the other hand, vitamin C’ RDAs simply are based on preventing scurvy or keeping oxidative balance, and it seems that a new threshold is required for optimal efficacy of gastric conversion of NO2− to NO. Species differences of AA metabolism need to be taken into consideration in studies investigating the therapeutic applications of inorganic NO3− in animal models of T2DM; experimental studies using non-AA-synthesizing species, e.g., guinea pig is warranted to confirm that AA is responsible for this lost-in-translation of anti-diabetic effects of inorganic NO3−.

Author Contributions

Idea and conceptualization: A.G. and Z.B. Writing: reviewing and editing: Z.B., A.G., K.K., and P.M. Literature research: Z.B., A.G., K.K., and P.M. Figure conceptualization and design: Z.B. and A.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study has been supported by Shahid Beheshti University of medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Grant number: 28129).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- Lundberg, J.O.; Weitzberg, E.; Gladwin, M.T. The nitrate-nitrite-nitric oxide pathway in physiology and therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008, 7, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghasemi, A.; Jeddi, S. Anti-obesity and anti-diabetic effects of nitrate and nitrite. Nitric Oxide Biol. Chem. 2017, 70, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, J.O.; Carlstrom, M.; Weitzberg, E. Metabolic Effects of Dietary Nitrate in Health and Disease. Cell Metab. 2018, 28, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessari, P.; Cecchet, D.; Cosma, A.; Vettore, M.; Coracina, A.; Millioni, R.; Iori, E.; Puricelli, L.; Avogaro, A.; Vedovato, M. Nitric Oxide Synthesis Is Reduced in Subjects With Type 2 Diabetes and Nephropathy. Diabetes 2010, 59, 2152–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natali, A.; Ribeiro, R.; Baldi, S.; Tulipani, A.; Rossi, M.; Venturi, E.; Mari, A.; Macedo, M.P.; Ferrannini, E. Systemic inhibition of nitric oxide synthesis in non-diabetic individuals produces a significant deterioration in glucose tolerance by increasing insulin clearance and inhibiting insulin secretion. Diabetologia 2013, 56, 1183–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheibi, S.; Jeddi, S.; Carlström, M.; Gholami, H.; Ghasemi, A. Effects of long-term nitrate supplementation on carbohydrate metabolism, lipid profiles, oxidative stress, and inflammation in male obese type 2 diabetic rats. Nitric Oxide Biol. Chem. 2018, 75, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheibi, S.; Bakhtiarzadeh, F.; Jeddi, S.; Farrokhfall, K.; Zardooz, H.; Ghasemi, A. Nitrite increases glucose-stimulated insulin secretion and islet insulin content in obese type 2 diabetic male rats. Nitric Oxide Biol. Chem. 2017, 64, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifi, S.; Rahimipour, A.; Jeddi, S.; Ghanbari, M.; Kazerouni, F.; Ghasemi, A. Dietary nitrate improves glucose tolerance and lipid profile in an animal model of hyperglycemia. Nitric Oxide Biol. Chem. 2015, 44, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohtake, K.; Nakano, G.; Ehara, N.; Sonoda, K.; Ito, J.; Uchida, H.; Kobayashi, J. Dietary nitrite supplementation improves insulin resistance in type 2 diabetic KKA(y) mice. Nitric Oxide Biol. Chem. 2015, 44, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlstrom, M.; Larsen, F.J.; Nystrom, T.; Hezel, M.; Borniquel, S.; Weitzberg, E.; Lundberg, J.O. Dietary inorganic nitrate reverses features of metabolic syndrome in endothelial nitric oxide synthase-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 17716–17720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero-Herrera, I.; Guimarães, D.D.; Moretti, C.; Zhuge, Z.; Han, H.; McCann Haworth, S.; Uribe Gonzalez, A.E.; Andersson, D.C.; Weitzberg, E.; Lundberg, J.O.; et al. Head-to-head comparison of inorganic nitrate and metformin in a mouse model of cardiometabolic disease. Nitric Oxide Biol. Chem. 2020, 97, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siervo, M.; Lara, J.; Jajja, A.; Sutyarjoko, A.; Ashor, A.W.; Brandt, K.; Qadir, O.; Mathers, J.C.; Benjamin, N.; Winyard, P.G.; et al. Ageing modifies the effects of beetroot juice supplementation on 24-hour blood pressure variability: An individual participant meta-analysis. Nitric Oxide Biol. Chem. 2015, 47, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambe, T.; Mason, R.P.; Dawoud, H.; Bhatt, D.L.; Malinski, T. Metformin treatment decreases nitroxidative stress, restores nitric oxide bioavailability and endothelial function beyond glucose control. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 98, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milsom, A.B.; Fernandez, B.O.; Garcia-Saura, M.F.; Rodriguez, J.; Feelisch, M. Contributions of nitric oxide synthases, dietary nitrite/nitrate, and other sources to the formation of NO signaling products. Antioxid Redox Signal 2012, 17, 422–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlström, M.; Liu, M.; Yang, T.; Zollbrecht, C.; Huang, L.; Peleli, M.; Borniquel, S.; Kishikawa, H.; Hezel, M.; Persson, A.E.G.; et al. Cross-talk Between Nitrate-Nitrite-NO and NO Synthase Pathways in Control of Vascular NO Homeostasis. Antioxid Redox Signal 2015, 23, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, W.T.; Cooke, J.P. Nutritional Impact on the Nitric Oxide Pathway. In Nitrite and Nitrate in Human Health and Disease; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 97–122. [Google Scholar]

- Bahadoran, Z.; Mirmiran, P.; Ghasemi, A.; Carlström, M.; Azizi, F.; Hadaegh, F. Vitamin C intake modify the impact of dietary nitrite on the incidence of type 2 diabetes: A 6-year follow-up in Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study. Nitric Oxide Biol. Chem. 2017, 62, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadoran, Z.; Carlström, M.; Ghasemi, A.; Mirmiran, P.; Azizi, F.; Hadaegh, F. Total antioxidant capacity of the diet modulates the association between habitual nitrate intake and cardiovascular events: A longitudinal follow-up in Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study. Nutr. Metab. 2018, 15, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hord, N.G.; Tang, Y.; Bryan, N.S. Food sources of nitrates and nitrites: The physiologic context for potential health benefits. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 90, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gangolli, S.D.; Van Den Brandt, P.A.; Feron, V.J.; Janzowsky, C.; Koeman, J.H.; Speijers, G.J.; Spiegelhalder, B.; Walker, R.; Wishnok, J.S. Nitrate, nitrite and N-nitroso compounds. Eur. J. Pharmacol. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 1994, 292, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, D.S.; Deen, W.M.; Karel, S.F.; Wagner, D.A.; Tannenbaum, S.R. Pharmacokinetics of nitrate in humans: Role of gastrointestinal absorption and metabolism. Carcinogenesis 1985, 6, 847–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, D.A.; Schultz, D.S.; Deen, W.M.; Young, V.R.; Tannenbaum, S.R. Metabolic fate of an oral dose of 15N-labeled nitrate in humans: Effect of diet supplementation with ascorbic acid. Cancer Res. 1983, 43, 1921–1925. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ellen, G.; Schuller, P.L.; Bruijns, E.; Froeling, P.G.; Baadenhuijsen, H.U. Volatile N-nitrosamines, nitrate and nitrite in urine and saliva of healthy volunteers after administration of large amounts of nitrate. IARC Sci. Publ. 1982, 41, 365–378. [Google Scholar]

- Radomski, J.L.; Palmiri, C.; Hearn, W.L. Concentrations of nitrate in normal human urine and the effect of nitrate ingestion. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1978, 45, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannala, A.S.; Mani, A.R.; Spencer, J.P.; Skinner, V.; Bruckdorfer, K.R.; Moore, K.P.; Rice-Evans, C.A. The effect of dietary nitrate on salivary, plasma, and urinary nitrate metabolism in humans. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2003, 34, 576–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saul, R.L.; Kabir, S.H.; Cohen, Z.; Bruce, W.R.; Archer, M.C. Reevaluation of Nitrate and Nitrite Levels in the Human Intestine. Cancer Res. 1981, 41, 2280–2283. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, H.; Shonle, H.; Grindley, H. The origin of the nitrates in the urine. J. Biol. Chem. 1916, 24, 461–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegelhalder, B.; Eisenbrand, G.; Preussmann, R. Influence of dietary nitrate on nitrite content of human saliva: Possible relevance to in vivo formation of N-nitroso compounds. Food Cosmet. Toxicol. 1976, 14, 545–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Liu, X.; Sun, Q.; Fan, Z.; Xia, D.; Ding, G.; Ong, H.L.; Adams, D.; Gahl, W.A.; Zheng, C.; et al. Sialin (SLC17A5) functions as a nitrate transporter in the plasma membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 13434–13439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, J.O.; Govoni, M. Inorganic nitrate is a possible source for systemic generation of nitric oxide. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2004, 37, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montenegro, M.F.; Sundqvist, M.L.; Nihlén, C.; Hezel, M.; Carlström, M.; Weitzberg, E.; Lundberg, J.O. Profound differences between humans and rodents in the ability to concentrate salivary nitrate: Implications for translational research. Redox Biol. 2016, 10, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witter, J.P.; Balish, E. Distribution and metabolism of ingested NO3− and NO2− in germfree and conventional-flora rats. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1979, 38, 861–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, R. The metabolism of dietary nitrites and nitrates. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 1996, 24, 780–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doel, J.J.; Benjamin, N.; Hector, M.P.; Rogers, M.; Allaker, R.P. Evaluation of bacterial nitrate reduction in the human oral cavity. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2005, 113, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Duncan, C.; Townend, J.; Killham, K.; Smith, L.M.; Johnston, P.; Dykhuizen, R.; Kelly, D.; Golden, M.; Benjamin, N.; et al. Nitrate-reducing bacteria on rat tongues. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997, 63, 924–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapil, V.; Haydar, S.M.; Pearl, V.; Lundberg, J.O.; Weitzberg, E.; Ahluwalia, A. Physiological role for nitrate-reducing oral bacteria in blood pressure control. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 55, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersson, J.; Carlström, M.; Schreiber, O.; Phillipson, M.; Christoffersson, G.; Jägare, A.; Roos, S.; Jansson, E.A.; Persson, A.E.; Lundberg, J.O.; et al. Gastroprotective and blood pressure lowering effects of dietary nitrate are abolished by an antiseptic mouthwash. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2009, 46, 1068–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govoni, M.; Jansson, E.A.; Weitzberg, E.; Lundberg, J.O. The increase in plasma nitrite after a dietary nitrate load is markedly attenuated by an antibacterial mouthwash. Nitric Oxide Biol. Chem. 2008, 19, 333–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, E.R.; Luk, B.; Cron, S.; Kusic, L.; McCue, T.; Bauch, T.; Kaplan, H.; Tribble, G.; Petrosino, J.F.; Bryan, N.S. Characterization of the rat oral microbiome and the effects of dietary nitrate. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 77, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, G.M.; Smith, L.M.; Drummond, R.S.; Duncan, C.W.; Golden, M.; Benjamin, N. Chemical synthesis of nitric oxide in the stomach from dietary nitrate in humans. Gut 1997, 40, 211–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iijima, K.; Fyfe, V.; McColl, K.E. Studies of nitric oxide generation from salivary nitrite in human gastric juice. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2003, 38, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahadoran, Z.; Mirmiran, P.; Ghasemi, A. Role of Nitric Oxide in Insulin Secretion and Glucose Metabolism. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. TEM 2020, 31, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, C.-N.; Tain, Y.-L. Regulation of Nitric Oxide Production in the Developmental Programming of Hypertension and Kidney Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-Y.; Ye, Z.-X.; Wang, X.-F.; Chang, J.; Yang, M.-W.; Zhong, H.-H.; Hong, F.-F.; Yang, S.-L. Nitric oxide bioavailability dysfunction involves in atherosclerosis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 97, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, S.; Han, M.; Rezaei, A.; Li, D.; Wu, G.; Ma, X. L-Arginine Modulates Glucose and Lipid Metabolism in Obesity and Diabetes. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2017, 18, 599–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piatti, P.M.; Monti, L.D.; Valsecchi, G.; Magni, F.; Setola, E.; Marchesi, F.; Galli-Kienle, M.; Pozza, G.; Alberti, K.G. Long-term oral L-arginine administration improves peripheral and hepatic insulin sensitivity in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 2001, 24, 875–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azizi, S.; Mahdavi, R.; Vaghef-Mehrabany, E.; Maleki, V.; Karamzad, N.; Ebrahimi-Mameghani, M. Potential roles of Citrulline and watermelon extract on metabolic and inflammatory variables in diabetes mellitus, current evidence and future directions: A systematic review. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2020, 47, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, J.O.; Weitzberg, E. NO generation from inorganic nitrate and nitrite: Role in physiology, nutrition and therapeutics. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 2009, 32, 1119–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadoran, Z.; Ghasemi, A.; Mirmiran, P.; Azizi, F.; Hadaegh, F. Beneficial effects of inorganic nitrate/nitrite in type 2 diabetes and its complications. Nutr. Metab. 2015, 12, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNally, B.; Griffin, J.L.; Roberts, L.D. Dietary inorganic nitrate: From villain to hero in metabolic disease? Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2016, 60, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, H.A.; McGing, E.; Fisher, I.; Böger, R.H.; Bode-Böger, S.M.; Jackson, G.; Ritter, J.M.; Chowienczyk, P.J. Endothelium-dependent vasodilation is independent of the plasma L-arginine/ADMA ratio in men with stable angina: Lack of effect of oral l-arginine on endothelial function, oxidative stress and exercise performance. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2001, 38, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulman, S.P.; Becker, L.C.; Kass, D.A.; Champion, H.C.; Terrin, M.L.; Forman, S.; Ernst, K.V.; Kelemen, M.D.; Townsend, S.N.; Capriotti, A.; et al. L-arginine therapy in acute myocardial infarction: The Vascular Interaction With Age in Myocardial Infarction (VINTAGE MI) randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2006, 295, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, S.M., Jr. Regulation of enzymes of urea and arginine synthesis. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 1992, 12, 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cynober, L.; Le Boucher, J.; Vasson, M.-P. Arginine metabolism in mammals. J. Nutr. Biochem. 1995, 6, 402–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.R.; Forsyth, C.J.; Jessup, W.; Robinson, J.; Celermajer, D.S. Oral L-arginine inhibits platelet aggregation but does not enhance endothelium-dependent dilation in healthy young men. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1995, 26, 1054–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, S.; Wu, C.C.; Shin, S.; Fung, H.L. Continuous exposure to L-arginine induces oxidative stress and physiological tolerance in cultured human endothelial cells. Amino Acids 2012, 43, 1179–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyström, T.; Ortsäter, H.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, F.; Larsen, F.J.; Weitzberg, E.; Lundberg, J.O.; Sjöholm, Å. Inorganic nitrite stimulates pancreatic islet blood flow and insulin secretion. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012, 53, 1017–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghasemi, A.; Afzali, H.; Jeddi, S. Effect of oral nitrite administration on gene expression of SNARE proteins involved in insulin secretion from pancreatic islets of male type 2 diabetic rats. Biomed. J. 2021, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, L.D.; Ashmore, T.; Kotwica, A.O.; Murfitt, S.A.; Fernandez, B.O.; Feelisch, M.; Murray, A.J.; Griffin, J.L. Inorganic nitrate promotes the browning of white adipose tissue through the nitrate-nitrite-nitric oxide pathway. Diabetes 2015, 64, 471–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheibi, S.; Jeddi, S.; Carlstrom, M.; Kashfi, K.; Ghasemi, A. Hydrogen sulfide potentiates the favorable metabolic effects of inorganic nitrite in type 2 diabetic rats. Nitric Oxide Biol. Chem. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapil, V.; Khambata, R.; Jones, D.; Rathod, K.; Primus, C.; Massimo, G.; Fukuto, J.; Ahluwalia, A. The Noncanonical Pathway for In Vivo Nitric Oxide Generation: The Nitrate-Nitrite-Nitric Oxide Pathway. Pharmacol. Rev. 2020, 72, 692–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeddi, S.; Yousefzadeh, N.; Afzali, H.; Ghasemi, A. Long-term nitrate administration increases expression of browning genes in epididymal adipose tissue of male type 2 diabetic rats. Gene 2021, 766, 145155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, R.; Peng, R.; Yang, Z.; Peng, Y.-Y.; Lu, N. Supplementation of dietary nitrate attenuated oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction in diabetic vasculature through inhibition of NADPH oxidase. Nitric Oxide Biol. Chem. 2020, 96, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, H.; Pathak, P.; Singh, P.; Gayen, J.R.; Jagavelu, K.; Dikshit, M. Systemic Insulin Resistance and Metabolic Perturbations in Chow Fed Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase Knockout Male Mice: Partial Reversal by Nitrite Supplementation. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norouzirad, R.; Gholami, H.; Ghanbari, M.; Hedayati, M.; González-Muniesa, P.; Jeddi, S.; Ghasemi, A. Dietary inorganic nitrate attenuates hyperoxia-induced oxidative stress in obese type 2 diabetic male rats. Life Sci. 2019, 230, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Torregrossa, A.C.; Potts, A.; Pierini, D.; Aranke, M.; Garg, H.K.; Bryan, N.S. Dietary nitrite improves insulin signaling through GLUT4 translocation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 67, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cermak, N.M.; Hansen, D.; Kouw, I.W.; van Dijk, J.W.; Blackwell, J.R.; Jones, A.M.; Gibala, M.J.; van Loon, L.J. A single dose of sodium nitrate does not improve oral glucose tolerance in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nutr. Res. 2015, 35, 674–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilchrist, M.; Winyard, P.G.; Fulford, J.; Anning, C.; Shore, A.C.; Benjamin, N. Dietary nitrate supplementation improves reaction time in type 2 diabetes: Development and application of a novel nitrate-depleted beetroot juice placebo. Nitric Oxide Biol. Chem. 2014, 40, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilchrist, M.; Winyard, P.G.; Aizawa, K.; Anning, C.; Shore, A.; Benjamin, N. Effect of dietary nitrate on blood pressure, endothelial function, and insulin sensitivity in type 2 diabetes. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 60, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faconti, L.; Mills, C.E. Cardiac effects of 6 months’ dietary nitrate and spironolactone in patients with hypertension and with/at risk of type 2 diabetes, in the factorial design, double-blind, randomized controlled VaSera trial. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2019, 85, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, C.E.; Govoni, V.; Faconti, L.; Casagrande, M.L.; Morant, S.V.; Crickmore, H.; Iqbal, F.; Maskell, P.; Masani, A.; Nanino, E. A randomised, factorial trial to reduce arterial stiffness independently of blood pressure: Proof of concept? The VaSera trial testing dietary nitrate and spironolactone. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 86, 891–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soin, A.; Bock, G.; Giordano, A.; Patel, C.; Drachman, D. A Randomized, Double-Blind Study of the Effects of a Sustained Release Formulation of Sodium Nitrite (SR-nitrite) on Patients with Diabetic Neuropathy. Pain Physician 2018, 21, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senefeld, J.W.; Wiggins, C.C.; Regimbal, R.J.; Dominelli, P.B.; Baker, S.E.; Joyner, M.J. Ergogenic Effect of Nitrate Supplementation: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2020, 52, 2250–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van De Walle, G.P.; Vukovich, M.D. The Effect of Nitrate Supplementation on Exercise Tolerance and Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2018, 32, 1796–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Nishi, S.K.; Jovanovski, E.; Zurbau, A.; Komishon, A.; Mejia, S.B.; Khan, T.A.; Sievenpiper, J.L.; Milicic, D.; Jenkins, A.; et al. Repeated administration of inorganic nitrate on blood pressure and arterial stiffness: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Hypertens. 2020, 38, 2122–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadoran, Z.; Norouzirad, R.; Mirmiran, P.; Gaeini, Z.; Jeddi, S.; Shokri, M.; Azizi, F.; Ghasemi, A. Effect of inorganic nitrate on metabolic parameters in patients with type 2 diabetes: A 24-week randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Nitric Oxide Biol. Chem. 2021, 107, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, A.I.; Gilchrist, M.; Winyard, P.G.; Jones, A.M.; Hallmann, E.; Kazimierczak, R.; Rembialkowska, E.; Benjamin, N.; Shore, A.C.; Wilkerson, D.P. Effects of dietary nitrate supplementation on the oxygen cost of exercise and walking performance in individuals with type 2 diabetes: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 86, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohler, E.R., 3rd; Hiatt, W.R.; Gornik, H.L.; Kevil, C.G.; Quyyumi, A.; Haynes, W.G.; Annex, B.H. Sodium nitrite in patients with peripheral artery disease and diabetes mellitus: Safety, walking distance and endothelial function. Vasc. Med. 2014, 19, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenway, F.L.; Predmore, B.L.; Flanagan, D.R.; Giordano, T.; Qiu, Y.; Brandon, A.; Lefer, D.J.; Patel, R.P.; Kevil, C.G. Single-dose pharmacokinetics of different oral sodium nitrite formulations in diabetes patients. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2012, 14, 552–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linster, C.L.; Van Schaftingen, E. Vitamin C. Biosynthesis, recycling and degradation in mammals. FEBS J. 2007, 274, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, M.; Padayatty, S.J.; Espey, M.G. Vitamin C: A concentration-function approach yields pharmacology and therapeutic discoveries. Adv. Nutr. 2011, 2, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EFSA NDA Panel (EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies). Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for vitamin C. EFSA J. 2013, 11, 3418–3468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frei, B.; Traber, M.G. The new US Dietary Reference Intakes for vitamins C and E. Redox Rep. 2001, 6, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, C.S. Biomarkers for establishing a tolerable upper intake level for vitamin C. Nutr. Rev. 1999, 57, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gorkom, G.N.Y.; Lookermans, E.L.; Van Elssen, C.H.M.J.; Bos, G.M.J. The Effect of Vitamin C (Ascorbic Acid) in the Treatment of Patients with Cancer: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashor, A.W.; Werner, A.D.; Lara, J.; Willis, N.D.; Mathers, J.C.; Siervo, M. Effects of vitamin C supplementation on glycaemic control: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 71, 1371–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, S.A.; Keske, M.A. Effects of Vitamin C Supplementation on Glycemic Control and Cardiovascular Risk Factors in People With Type 2 Diabetes: A GRADE-Assessed Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Diabetes Care 2021, 44, 618–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukaguchi, H.; Tokui, T.; Mackenzie, B.; Berger, U.V.; Chen, X.Z.; Wang, Y.; Brubaker, R.F.; Hediger, M.A. A family of mammalian Na+-dependent L-ascorbic acid transporters. Nature 1999, 399, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, W.J.; Johnson, D.; Jarvis, S.M. Vitamin C transport systems of mammalian cells. Mol. Membr. Biol. 2001, 18, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, M.; Conry-Cantilena, C.; Wang, Y.; Welch, R.W.; Washko, P.W.; Dhariwal, K.R.; Park, J.B.; Lazarev, A.; Graumlich, J.F.; King, J.; et al. Vitamin C pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers: Evidence for a recommended dietary allowance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 3704–3709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sage, J.M.; Carruthers, A. Human erythrocytes transport dehydroascorbic acid and sugars using the same transporter complex. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2014, 306, C910–C917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corpe, C.P.; Eck, P.; Wang, J.; Al-Hasani, H.; Levine, M. Intestinal dehydroascorbic acid (DHA) transport mediated by the facilitative sugar transporters, GLUT2 and GLUT8. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 9092–9101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumsey, S.C.; Kwon, O.; Xu, G.W.; Burant, C.F.; Simpson, I.; Levine, M. Glucose transporter isoforms GLUT1 and GLUT3 transport dehydroascorbic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 18982–18989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Washko, P.W.; Wang, Y.; Levine, M. Ascorbic acid recycling in human neutrophils. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268, 15531–15535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padayatty, S.J.; Levine, M. Vitamin C: The known and the unknown and Goldilocks. Oral Dis. 2016, 22, 463–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drouin, G.; Godin, J.-R.; Pagé, B. The genetics of vitamin C loss in vertebrates. Curr. Genom. 2011, 12, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginter, E. Endogenous ascorbic acid synthesis and recommended dietary allowances for vitamin C. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1981, 34, 1448–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwama, M.; Amano, A.; Shimokado, K.; Maruyama, N.; Ishigami, A. Ascorbic acid levels in various tissues, plasma and urine of mice during aging. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2012, 58, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Bae, S.; Yu, Y.; Kim, Y.; Kim, H.-R.; Hwang, Y.-I.; Kang, J.S.; Lee, W.J. The analysis of vitamin C concentration in organs of gulo(-/-) mice upon vitamin C withdrawal. Immune Netw. 2012, 12, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Loo, B.; Bachschmid, M.; Spitzer, V.; Brey, L.; Ullrich, V.; Lüscher, T.F. Decreased plasma and tissue levels of vitamin C in a rat model of aging: Implications for antioxidative defense. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003, 303, 483–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, N.; McKnight, G. Implications for Nitrate Intake. In Managing Risks of Nitrates to Humans and the Environment; Wilson, W.S., Ball, A.S., Hinton, R.H., Eds.; The Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, UK, 1999; pp. 281–288. [Google Scholar]

- Monsen, E.R. Dietary reference intakes for the antioxidant nutrients: Vitamin C, vitamin E, selenium, and carotenoids. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2000, 100, 637. [Google Scholar]

- Brubacher, D.; Moser, U.; Jordan, P. Vitamin C concentrations in plasma as a function of intake: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2000, 70, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helser, M.A.; Hotchkiss, J.H.; Roe, D.A. Influence of fruit and vegetable juices on the endogenous formation of N-nitrosoproline and N-nitrosothiazolidine-4-carboxylic acid in humans on controlled diets. Carcinogenesis 1992, 13, 2277–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallner, A.; Hartmann, D.; Hornig, D. On the absorption of ascorbic acid in man. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 1977, 47, 383–388. [Google Scholar]

- Kallner, A.; Hartmann, D.; Hornig, D. Steady-state turnover and body pool of ascorbic acid in man. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1979, 32, 530–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuo, B.-G.; Yan, Y.-H.; Ge, Z.-L.; Ou, G.-W.; Zhao, K. Ascorbic acid secretion in the human stomach and the effect of gastrin. World J. Gastroenterol. 2000, 6, 704–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, J.; Mosbach, E.; Schulenberg, S. Ascorbic acid synthesis in normal and drug-treated rats, studied with L-ascorbic-l-C14 acid. J. Biol. Chem. 1954, 207, 679–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallner, A. Requirement for vitamin C based on metabolic studies. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1987, 498, 418–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corpe, C.P.; Tu, H.; Eck, P.; Wang, J.; Faulhaber-Walter, R.; Schnermann, J.; Margolis, S.; Padayatty, S.; Sun, H.; Wang, Y.; et al. Vitamin C transporter Slc23a1 links renal reabsorption, vitamin C tissue accumulation, and perinatal survival in mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2010, 120, 1069–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, J.O.N.; Weitzberg, E.; Lundberg, J.M.; Alving, K. Intragastric nitric oxide production in humans: Measurements in expelled air. Gut 1994, 35, 1543–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iijima, K.; Henry, E.; Moriya, A.; Wirz, A.; Kelman, A.W.; McColl, K.E.L. Dietary nitrate generates potentially mutagenic concentrations of nitric oxide at the gastroesophageal junction. Gastroenterology 2002, 122, 1248–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moriya, A.; Grant, J.; Mowat, C.; Williams, C.; Carswell, A.; Preston, T.; Anderson, S.; Iijima, K.; McColl, K.E. In vitro studies indicate that acid catalysed generation of N-nitrosocompounds from dietary nitrate will be maximal at the gastro-oesophageal junction and cardia. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2002, 37, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Iijima, K.; Moriya, A.; McElroy, K.; Scobie, G.; Fyfe, V.; McColl, K.E.L. Conditions for acid catalysed luminal nitrosation are maximal at the gastric cardia. Gut 2003, 52, 1095–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobala, G.M.; Schorah, C.J.; Sanderson, M.; Dixon, M.F.; Tompkins, D.S.; Godwin, P.; Axon, A.T.R. Ascorbic acid in the human stomach. Gastroenterology 1989, 97, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waring, A.J.; Drake, I.M.; Schorah, C.J.; White, K.L.; Lynch, D.A.; Axon, A.T.; Dixon, M.F. Ascorbic acid and total vitamin C concentrations in plasma, gastric juice, and gastrointestinal mucosa: Effects of gastritis and oral supplementation. Gut 1996, 38, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobala, G.M.; Pignatelli, B.; Schorah, C.J.; Bartsch, H.; Sanderson, M.; Dixon, M.F.; Shires, S.; King, R.F.; Axon, A.T. Levels of nitrite, nitrate, N-nitroso compounds, ascorbic acid and total bile acids in gastric juice of patients with and without precancerous conditions of the stomach. Carcinogenesis 1991, 12, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waring, A.J.; Schorah, C.J. Transport of ascorbic acid in gastric epithelial cells in vitro. Clin. Chim. Acta Int. J. Clin. Chem. 1998, 275, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schorah, C.J.; Sobala, G.M.; Sanderson, M.; Collis, N.; Primrose, J.N. Gastric juice ascorbic acid: Effects of disease and implications for gastric carcinogenesis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1991, 53, 287s–293s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rood, J.C.; Ruiz, B.; Fontham, E.T.; Malcom, G.T.; Hunter, F.M.; Sobhan, M.; Johnson, W.D.; Correa, P. Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis and the ascorbic acid concentration in gastric juice. Nutr. Cancer 1994, 22, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathbone, B.J.; Johnson, A.W.; Wyatt, J.I.; Kelleher, J.; Heatley, R.V.; Losowsky, M.S. Ascorbic acid: A factor concentrated in human gastric juice. Clin. Sci. 1989, 76, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowat, C.; Carswell, A.; Wirz, A.; McColl, K.E.L. Omeprazole and dietary nitrate independently affect levels of vitamin C and nitrite in gastric juice. Gastroenterology 1999, 116, 813–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.W.; Patchett, S.E.; Perrett, D.; Katelaris, P.H.; Domizio, P.; Farthing, M.J.G. The relation between gastric vitamin C concentrations, mucosal histology, and CagA seropositivity in the human stomach. Gut 1998, 43, 322–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muto, N.; Eguchi, R.; Akagi, Y.; Itoh, N.; Tanaka, K. Cholecystokinin stimulates ascorbic acid secretion through its specific receptor in the perfused stomach of rats. Res. Commun. Mol. Pathol. Pharmacol. 1998, 101, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Muto, N.; Ohta, T.; Suzuki, T.; Itoh, N.; Tanaka, K. Evidence for the involvement of a muscarinic receptor in ascorbic acid secretion in the rat stomach. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1997, 53, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breidenbach, A.W.; Cambel, P.; Ray, F.E. Gastric Ascorbic Acid in the Gastritic Rat. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1952, 80, 144–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licht, W.R.; Tannenbaum, S.R.; Deen, W.M. Use of ascorbic acid to inhibit nitrosation: Kinetic and mass transfer considerations for an in vitro system. Carcinogenesis 1988, 9, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mowat, C.; McColl, K.E.L. Alterations in intragastric nitrite and vitamin C levels during acid inhibitory therapy. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2001, 15, 523–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okazaki, K.; Ishii, Y.; Kitamura, Y.; Maruyama, S.; Umemura, T.; Miyauchi, M.; Yamagishi, M.; Imazawa, T.; Nishikawa, A.; Yoshimura, Y. Dose-dependent promotion of rat forestomach carcinogenesis by combined treatment with sodium nitrite and ascorbic acid after initiation with N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine: Possible contribution of nitric oxide-associated oxidative DNA damage. Cancer Sci. 2006, 97, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLennan, S.; Yue, D.K.; Fisher, E.; Capogreco, C.; Heffernan, S.; Ross, G.R.; Turtle, J.R. Deficiency of Ascorbic Acid in Experimental Diabetes: Relationship With Collagen and Polyol Pathway Abnormalities. Diabetes 1988, 37, 359–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.; Willis, J.; Gearry, R.; Skidmore, P.; Fleming, E.; Frampton, C.; Carr, A. Inadequate Vitamin C Status in Prediabetes and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Associations with Glycaemic Control, Obesity, and Smoking. Nutrients 2017, 9, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie-David, D.; Gunton, J. Vitamin c deficiency and diabetes mellitus-easily missed? Diabet. Med. A J. Br. Diabet. Assoc. 2017, 34, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysy, J.; Zimmerman, J. Ascorbic acid status in diabetes mellitus. Nutr. Res. 1992, 12, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seghieri, G.; Martinoli, L.; di Felice, M.; Anichini, R.; Fazzini, A.; Ciuti, M.; Miceli, M.; Gaspa, L.; Franconi, F. Plasma and platelet ascorbate pools and lipid peroxidation in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 1998, 28, 659–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Som, S.; Basu, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Deb, S.; Choudhury, P.R.; Mukherjee, S.; Chatterjee, S.N.; Chatterjee, I.B. Ascorbic acid metabolism in diabetes mellitus. Metab. Clin. Exp. 1981, 30, 572–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, A.; Girling, A.; Gray, L.; Le Guen, C.; Lunec, J.; Barnett, A. Disturbed handling of ascorbic acid in diabetic patients with and without microangiopathy during high dose ascorbate supplementation. Diabetologia 1991, 34, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.T.; Rayner, C.K.; Jones, K.L.; Talley, N.J.; Horowitz, M. Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Diabetes: Prevalence, Assessment, Pathogenesis, and Management. Diabetes Care 2018, 41, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devrajani, B.R.; Shah, S.Z.; Soomro, A.A.; Devrajani, T. Type 2 diabetes mellitus: A risk factor for Helicobacter pylori infection: A hospital based case-control study. Int. J. Diabetes Dev. Ctries. 2010, 30, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boehme, M.W.; Autschbach, F.; Ell, C.; Raeth, U. Prevalence of silent gastric ulcer, erosions or severe acute gastritis in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus—A cross-sectional study. Hepato Gastroenterol. 2007, 54, 643–648. [Google Scholar]

- Hasler, W.L.; Coleski, R.; Chey, W.D.; Koch, K.L.; McCallum, R.W.; Wo, J.M.; Kuo, B.; Sitrin, M.D.; Katz, L.A.; Hwang, J.; et al. Differences in intragastric pH in diabetic vs. idiopathic gastroparesis: Relation to degree of gastric retention. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2008, 294, G1384–G1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, J.T.; Hafkesbring, R. Comparative studies of ascorbic acid levels in gastric secretion and blood. III. Gastrointestinal diseases. Gastroenterology 1957, 32, 878–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashor, A.W.; Shannon, O.M.; Werner, A.-D.; Scialo, F.; Gilliard, C.N.; Cassel, K.S.; Seal, C.J.; Zheng, D.; Mathers, J.C.; Siervo, M. Effects of inorganic nitrate and vitamin C co-supplementation on blood pressure and vascular function in younger and older healthy adults: A randomised double-blind crossover trial. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 708–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednar, C.; Kies, C. Nitrate and vitamin C from fruits and vegetables: Impact of intake variations on nitrate and nitrite excretions of humans. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 1994, 45, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).