Biallelic Variants in KIF17 Associated with Microphthalmia and Coloboma Spectrum

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Microphthalmia refers to an eye with an axial length two standard deviations below the mean for age, and this condition has an estimated prevalence of 1 per 7000 live births.

- Anophtalmia is identified with the absence of ocular tissue in the orbit and has an estimated prevalence of 1 per 30,000 live births.

2. Methods

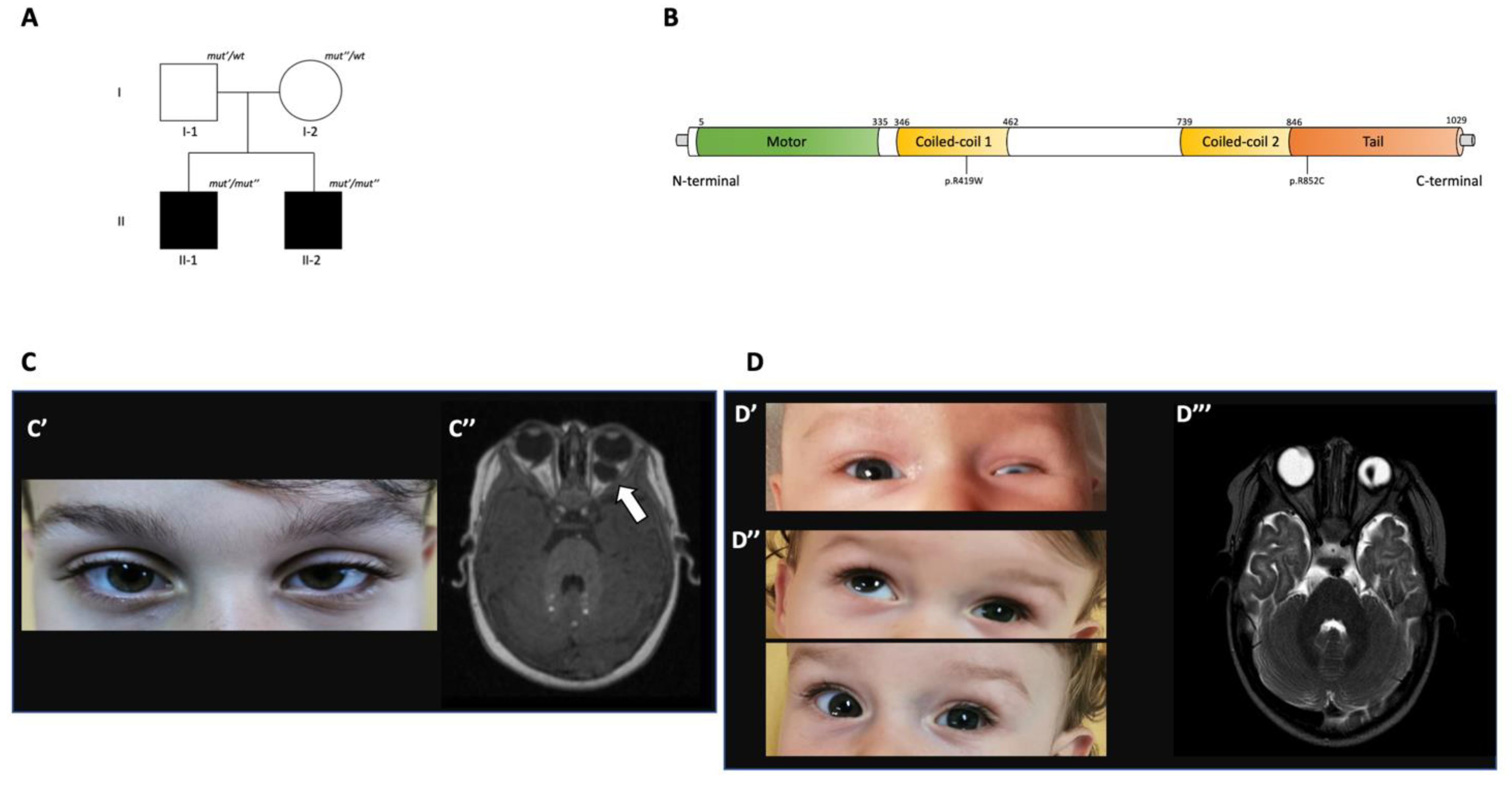

3. Family Report

3.1. Phenotypic Features

3.2. Genetic Results

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hamosh, A.; Scott, A.F.; Amberger, J.; Valle, D.; McKusick, V.A. Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM). Hum. Mutat. 1999, 15, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, C.J.; Dawe, R.K.; Christie, K.R.; Cleveland, D.W.; Dawson, S.C.; Endow, S.A.; Goldstein, L.S.B.; Goodson, H.V.; Hirokawa, N.; Howard, J.; et al. A standardized kinesin nomenclature. J. Cell Biol. 2004, 167, 19–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong-Riley, M.T.; Besharse, J.C. The kinesin superfamily protein KIF17: One protein with many functions. Biomol. Concepts 2012, 3, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, T.R.; Kundinger, S.R.; Pavlovich, A.L.; Bostrom, J.R.; Link, B.A.; Besharse, J.C. Cos2/Kif7 and Osm-3/Kif17 regulate onset of outer segment development in zebrafish photoreceptors through distinct mechanisms. Dev. Biol. 2017, 425, 176–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Insinna, C.; Luby-Phelps, K.; Link, B.A.; Besharse, J.C. Analysis of IFT Kinesins in Developing Zebrafish Cone Photoreceptor Sensory Cilia. Biophys. Tools Biol. 2009, 93, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.S.; Fitzpatrick, D.R. Anophthalmia and microphthalmia. Orphanet. J. Rare Dis. 2007, 2, 47–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, K.A.; Fitzpatrick, D.R. The genetic architecture of microphthalmia, anophthalmia and coloboma. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2014, 57, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardakjian, T.; Weiss, A.; Schneider, A. Microphthalmia/Anophthalmia/Coloboma Spectrum; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Altintas, A.G.K. Chorioretinal coloboma: Clinical presentation complications and treatment alternatives. Adv. Ophthalmol. Vis. Syst. 2019, 9, 106–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, R.M.; Abbey, A.M.; Shah, A.R.; Drenser, K.A.; Trese, M.T.; Capone, A. Chorioretinal Coloboma Complications: Retinal Detachment and Choroidal Neovascular Membrane. J. Ophthalmic. Vis. Res. 2017, 12, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salpietro, V.; Efthymiou, S.; Manole, A.; Maurya, B.; Wiethoff, S.; AshokKumar, B.; Cutrupi, M.C.; DiPasquale, V.; Manti, S.; Botía, J.A.; et al. A loss-of-function homozygous mutation in DDX59 implicates a conserved DEAD-box RNA helicase in nervous system development and function. Hum. Mutat. 2017, 39, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efthymiou, S.; Salpietro, V.; Malintan, N.; Poncelet, M.; Kriouile, Y.; Fortuna, S.; De Zorzi, R.; Payne, K.; Henderson, L.B.; Cortese, A.; et al. Biallelic mutations in neurofascin cause neurodevelopmental impairment and peripheral demyelination. Brain 2019, 142, 2948–2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malicki, J.; Besharse, J.C. Kinesin-2 family motors in the unusual photoreceptor cilium. Vis. Res. 2012, 75, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, S.S.; Wong-Riley, M.T.T. The kinesin superfamily protein KIF17 is regulated by the same transcription factor (NRF-1) as its cargo NR2B in neurons. Biochim. Biophys. ACTA (BBA) Bioenerg. 2011, 1813, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Takei, Y.; Kido, M.A.; Hirokawa, N. Molecular Motor KIF17 Is Fundamental for Memory and Learning via Differential Support of Synaptic NR2A/2B Levels. Neuron 2011, 70, 310–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberson, R.; Toso, L.; Abebe, D.; Spong, C.Y. Altered expression of KIF17, a kinesin motor protein associated with NR2B trafficking, may mediate learning deficits in a Down syndrome mouse model. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2008, 198, 313.e1–313.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Wong, R.W.-C.; Setou, M.; Teng, J.; Takei, Y.; Hirokawa, N. Overexpression of motor protein KIF17 enhances spatial and working memory in transgenic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 14500–14505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarabeux, J.; Champagne, N.; Brustein, E.; Hamdan, F.F.; Gauthier, J.; Lapointe, M.; Maios, C.; Piton, A.; Spiegelman, D.; Henrion, E.; et al. De Novo Truncating Mutation in Kinesin 17 Associated with Schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry 2010, 68, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuray, C.; Maroofian, R.; Scala, M.; Sultan, T.; Pai, G.S.; Mojarrad, M.; El Khashab, H.; DeHoll, L.; Yue, W.; AlSaif, H.S.; et al. Early-infantile onset epilepsy and developmental delay caused by bi-allelic GAD1 variants. Brain 2020, 143, 2388–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manole, A.; Efthymiou, S.; O’Connor, E.; Mendes, M.I.; Jennings, M.; Maroofian, R.; Davagnanam, I.; Mankad, K.; Lopez, M.R.; Salpietro, V.; et al. De Novo and Bi-allelic Pathogenic Variants in NARS1 Cause Neurodevelopmental Delay Due to Toxic Gain-of-Function and Partial Loss-of-Function Effects. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2020, 107, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salpietro, V.; Zollo, M.; Vandrovcova, J.; Ryten, M.; Botia, A.J.; Ferrucci, V.; Manole, A.; Efthymiou, S.; Al Mutairi, F.; Bertini, E.; et al. The phenotypic and molecular spectrum of PEHO syndrome and PEHO-like disorders. Brain 2017, 140, e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.; Rousseau, J.; Peng, H.; Aouabed, Z.; Priam, P.; Theroux, J.-F.; Jefri, M.; Tanti, A.; Wu, H.; Kolobova, I.; et al. Mutations in ACTL6B Cause Neurodevelopmental Deficits and Epilepsy and Lead to Loss of Dendrites in Human Neurons. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2019, 104, 815–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zollo, M.; Ahmed, M.; Ferrucci, V.; Salpietro, V.; Asadzadeh, F.; Carotenuto, M.; Maroofian, R.; Al-Amri, A.; Singh, R.; Scognamiglio, I.; et al. PRUNE is crucial for normal brain development and mutated in microcephaly with neurodevelopmental impairment. Brain 2017, 140, 940–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piard, J.; Umanah, G.K.E.; Harms, F.L.; Abalde-Atristain, L.; Amram, D.; Chang, M.; Chen, R.; Alawi, M.; Salpietro, V.; Rees, M.I.; et al. A homozygous ATAD1 mutation impairs postsynaptic AMPA receptor trafficking and causes a lethal encephalopathy. Brain 2018, 141, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaisancié, J.; Ceroni, F.; Holt, R.; Seco, C.Z.; Calvas, P.; Chassaing, N.; Ragge, N.K. Genetics of anophthalmia and microphthalmia. Part 1: Non-syndromic anophthalmia/microphthalmia. Qual. Life Res. 2019, 138, 799–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivanna, M.; Anand, M.; Chakrabarti, S.; Khanna, H. Ocular Ciliopathies: Genetic and Mechanistic Insights into Developing Therapies. Curr. Med. Chem. 2019, 26, 3120–3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheway, G.; Parry, D.A.; Johnson, C.A. The Role of Primary Cilia in the Development and Disease of the Retina. Organogenesis 2014, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | Percentage of MAC Individuals with Pathogenic Variants in This Gene |

|---|---|

| SOX2 | 15–20% |

| OTX2 | 2–5% |

| RAX | 3% |

| FOXE | 3% |

| BMP4 | 2% |

| PAX6 | 2% |

| BCOR | >1% |

| CHD7 | >1% |

| STRA6 | >1% |

| GDF6 | 1% |

| Population | Allele Count | Allele Number | Number of Homozygotes | Allele Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| East Asian | 2 | 19,836 | 0 | 0.0001008 |

| Latino/American | 3 | 35,348 | 0 | 0.00008487 |

| South Asian | 2 | 30,584 | 0 | 0.00006539 |

| European (non-Finnish) | 8 | 125,508 | 0 | 0.00006374 |

| European (Finnish) | 1 | 24,992 | 0 | 0.00004001 |

| African/African-American | 0 | 23,632 | 0 | 0.000 |

| Ashkenazi Jewish | 0 | 10,270 | 0 | 0.000 |

| Other | 0 | 7108 | 0 | 0.000 |

| XX | 9 | 125,720 | 0 | 0.00007159 |

| XY | 7 | 151,558 | 0 | 0.00004619 |

| Total | 16 | 277,278 | 0 | 0.00005770 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Riva, A.; Gambadauro, A.; Dipasquale, V.; Casto, C.; Ceravolo, M.D.; Accogli, A.; Scala, M.; Ceravolo, G.; Iacomino, M.; Zara, F.; et al. Biallelic Variants in KIF17 Associated with Microphthalmia and Coloboma Spectrum. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4471. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22094471

Riva A, Gambadauro A, Dipasquale V, Casto C, Ceravolo MD, Accogli A, Scala M, Ceravolo G, Iacomino M, Zara F, et al. Biallelic Variants in KIF17 Associated with Microphthalmia and Coloboma Spectrum. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021; 22(9):4471. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22094471

Chicago/Turabian StyleRiva, Antonella, Antonella Gambadauro, Valeria Dipasquale, Celeste Casto, Maria Domenica Ceravolo, Andrea Accogli, Marcello Scala, Giorgia Ceravolo, Michele Iacomino, Federico Zara, and et al. 2021. "Biallelic Variants in KIF17 Associated with Microphthalmia and Coloboma Spectrum" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22, no. 9: 4471. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22094471

APA StyleRiva, A., Gambadauro, A., Dipasquale, V., Casto, C., Ceravolo, M. D., Accogli, A., Scala, M., Ceravolo, G., Iacomino, M., Zara, F., Striano, P., Cuppari, C., Di Rosa, G., Cutrupi, M. C., Salpietro, V., & Chimenz, R. (2021). Biallelic Variants in KIF17 Associated with Microphthalmia and Coloboma Spectrum. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(9), 4471. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22094471